Taxes are not About Urbanism

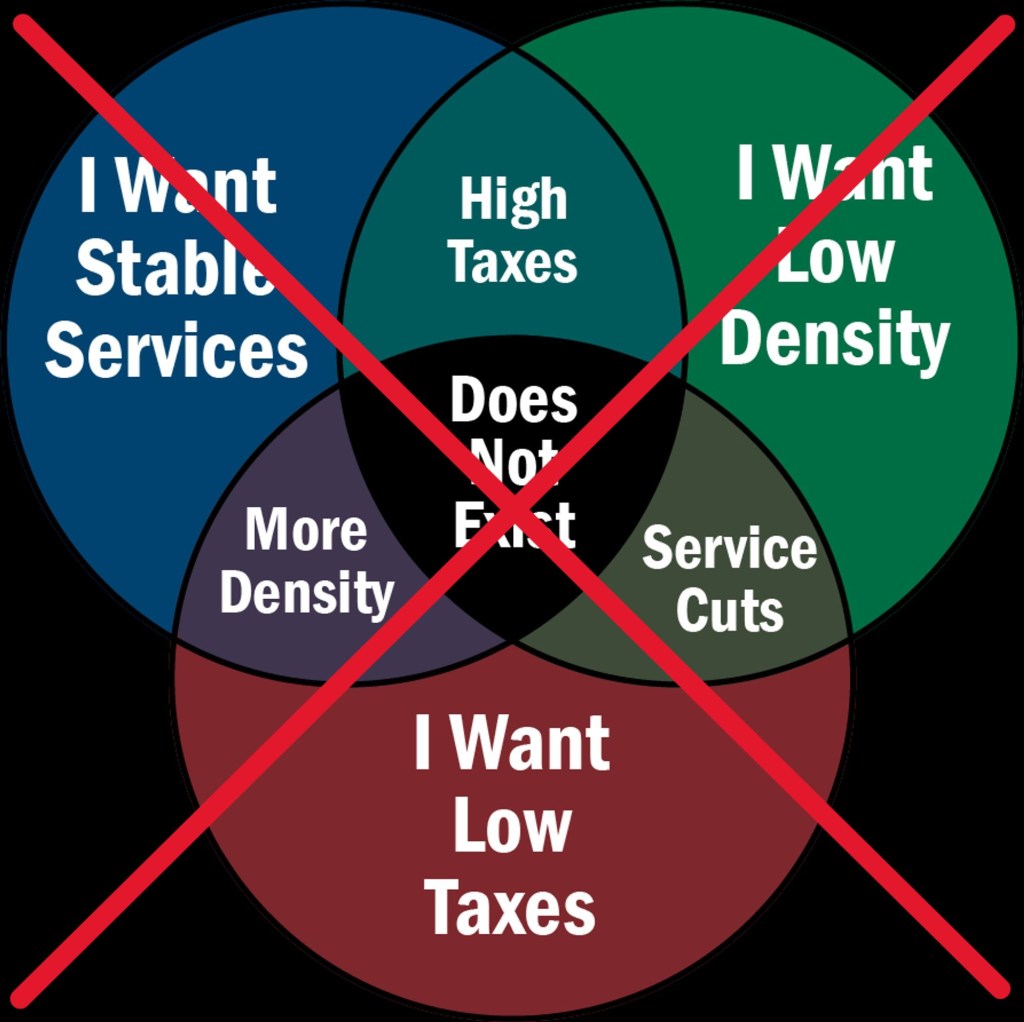

I caused a ruckus on social media when I pointed out that a Venn diagram commonly posted on Strong Towns and by American urbanists in general about taxes, services, and urbanism, is completely false:

The truth is that the overwhelming majority of taxes and services are about things that don’t meaningfully depend on local density. The overwhelming majority of those services are not even locally provided. In the United States, in 2022, taxes split as 67.5% federal, 19.1% state, 13.4% local. In Germany, in theory the division is similar, but in practice 95% of taxes are levied federally, but a portion are distributed to the states by formula.

Most of what all of this goes to is welfare programs. La Protection Sociale en France et en Europe puts the proportion of GDP going to social protection at 32% in France, 29% in Germany, and 27% Union-wide, all as of 2022. This includes programs whose recipients loudly insist that they are not welfare, including old age pensions and health care, comprising 82% of the above total. Government spending ranges around 50% of GDP here; France ranks first in the OECD, at 58%, so that its share of government spending going to social protection, slightly more than half, is if anything a little less than the European average. In the United States, these programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, income security) comprise two-thirds of non-interest federal spending, and one third of state and local spending. A couple additional percent – more in the United States than in Europe with one notable exception – is the military plus veteran-specific welfare in the US. None of this has anything to do with how much urban sprawl there is, or how municipal finances are structured.

Local taxes in the United States mostly go to schools. Education expenses are a combination of teacher and administrator salaries and facilities spending; these are not about density. Entire comparative tomes have been written about education funding, none touching density, because it doesn’t matter; for example, the OECD’s Education at a Glance database goes into per-student spending, teacher salaries, administrator salaries, student-teacher ratios, the public-private school division, the vocational-academic track division, graduation rates, the earnings advantages of graduates at various levels, and correlations with civic participation. The most notable features of the United States are high educational segregation, and low teacher salaries compared with the average for university-educated workers. This is not an urbanist issue; American urbanist activists have been spending generations avoiding talking about school segregation, to the point that the activists who do talk about education from any angle are more or less disjoint from the ones who talk about recognizably urbanist issue. The Venn diagram above is a good example of this: instead of talking about curricular rigor or teachers or segregation or how schools are funded, urbanists prefer to pretend reducing urban sprawl is the solution (not mentioned: any of the problems internal to, say, New York City public schools).

Once we get to items that do depend on what urbanists care about, it’s at the bottom of the list of budgetary priorities. Transportation costs are a small share of GDP; in the US, an extreme case in road costs, they’re 2% of federal spending and 5.6% of subnational spending, which averages out to somewhat more than 3% of GDP. German federal investment in roads is around 0.25% of GDP, and federal investment in rail is similar but planned to be double that in 2026-27. I haven’t seen more recent numbers, but in 2018, public transport finances across Germany amounted to 14.248 billion € in costs and 7.363 billion € in fare revenue; the difference, about 7 billion €, was 0.2% of 2018 GDP, covering about 16% of work trips Germany-wide.

So, yes, reduced sprawl would reduce the required spending on roads, but it’s not going to be especially visible in tax bills, which are dominated by other things. The biggest drivers of the cost of private transportation are the costs of buying, maintaining, and fueling the car. Those drive American spending on transportation to 17% of household spending, of which 8.3% are not cars, and buying the car and fuel for it are two thirds of the rest (that is, 10.3% of household spending). This is high per capita and per GDP; it is also not what urbanists who try to calculate operating ratios for roads talk about – the problem with private transportation is not the public cost of the roads, but the private cost to households.

Then there’s policing. Strong Towns has a particular infamy on the subject – Chuck Marohn essentially canceled himself among anyone concerned with civil rights when, during the initial Black Lives Matter protests in 2014, his take was about the lack of placemaking in suburbs like Ferguson, requiring people to protest in the middle of roads. On social media, multiple people insisted to me that higher density permits higher-quality (?) or lower-cost policing; at least as far as police brutality goes, the pattern is that it happens 1-2 orders of magnitude more in the US than in the rest of the developed world, and that in the US, it happens to black people about three times more than to white people, and it happens less in the Northeast than elsewhere, even in blacker-than-average places like Buffalo or Philadelphia. Urban departments are probably somewhat more professional than rural sheriffs’ departments, but this probably isn’t really a matter of suburban sprawl development but jurisdiction size, and is also not at all what the Venn diagram is trying to say. “Big central cities that have dense cores and can annex suburbs end up having very high police spending but get more professional departments out of this” is nowhere in the Venn diagram. It is not implied in it. It is directly opposed to what Strong Towns says about municipal finances, which is about long-term budgeting for municipalities with given borders and not about the desirability of delocalizing decisionmaking.

It’s always tempting to try to turn one’s issue into an omnicause. High taxes and poor services? Sprawl. Police violence? Sprawl. Schools? Sprawl. High housing costs? Sprawl. Government corruption? Sprawl. It creates an illusion of seriousness, of solving systemic social problems, while really only droning about one peripheral issue. It creates an illusion of outside-the-box solutions, while really ignoring real tradeoffs, in this case between taxes and government services. And it creates an illusion of solidarity and alliance between different advocacy groups, while really giving activists for one cause permission structure to bring up their pet cause no matter how unimportant it is in the moment.

Bravo!!!

Data Based INSIGHT

The other problem with this diagram is that ‘Low Taxes’ overlaps with ‘High Density’ and ‘High Taxes’ overlaps with ‘Low Density’. Although urbanists love to think that 10,000 people living along a km of road will each pay 1/10th the upkeep they would if only 1,000 people lived there, the fact is (at least in the US) that generally the denser the city or state, the higher the tax burden. Thus the highest tax burden states are NY, CT, Hawaii, CA, etc. while the lowest are Wyoming, S. Dakota, Texas, etc.

Note that this probably has nothing to do with density per se but rather that denser places tend to vote more liberally, and liberal polities tend to have higher taxes and spending. But it does invalidate the Strong Towns-ish notion that making everything closer would lower taxes, even setting aside Alon’s point about most spending being density indpendent.

If you take a road with 1000 people on it an magically increase the density to 10000 people the cost to maintain that road goes up significantly. While it isn’t a linear increase it is an increase in costs and so your taxes cannot go down by 1/10th.

The above assumes the same road. However rural roads are often gravel – very cheap to maintain and work just fine, but in a city you would be running a road grader down them twice a day, backing up traffic which they wouldn’t accept. City folks would also hate all the dust from a gravel road and so be willing to pay increased taxes. The taxes needed to pave a gravel road to city standards would be unaffordably in rural areas (assuming the accountants depreciate it correctly) so they do without even though they want pavement.

It isn’t just liberal policies that make sending more attractive. It is also the cost/benefit for those taxes. Rural areas would love to have an ambulance within 5 minutes just like the city folks get – but that would cost them over $1000/year, in a dense area your taxes go up by $1/year to get that service for the exact same benefit. Rural areas often just put everyone on the volunteer file department – if you only need first aid help is closer/faster than in the city, but if you need a AED, IV, or other such special equipment: the ambulance is half an hour away while seconds are counting.

Cities often have a library, swimming pool, community center, parks, organized sports (on special fields), side walks. As a city dweller my share of all that is a few bucks a year. However in rural areas getting those convenient is just too expensive and so you do without. You have to learn to like actives that can be done with less people. If you want a library you have to buy your own books (or make a weekly trip to town for their library – you are doing this for groceries already but if it is rainy so you have read all the books half way through the week it isn’t easy to get more. If you want to swim, you better like your pond (or install your own pool – $$$ but done in the city so affordable if you really want). Of course you get some benefits – you can safely shoot a gun off your back deck, allowing some hobbies not possible in the city.

Those low density states have high federal subsidies though.

Except they really don’t.

First, as Alon noted, federal spending is overwhelmingly social spending, so all of those statistics about which states are “donor” vs “taker” states are really just mapping proportion of elderly population (since that is where social security and Medicare go) and poor population (Medicaid and other welfare). Rural states are older and poorer than urban ones, so they “get” more federal spending.

Second, there are many types of federal spending tied to area (for good reason) that make rural (larger) states look like they are “getting” more money. For instance, S Dakota and Nebraska each have three federal weather radars while NY has six and Connecticut and R Island have zero. Those rural states on the Great Plains are getting much more per capita spending from the National Weather Service than the urbanized East coast ones. The same logic applies to spending on interstate highways, the military, national parks, agriculture, etc.

In neither of these cases is the federal government subsidizing basic services like roads, schools, trash, etc. Federal spending this way is largely either density agnostic (like school lunches, funded via a formula related to poverty) or a result of legislative pork (Sen Feinstein got the feds to buy San Francisco new fire boats, for instance).

Interstate highways are roads?

Not in the sense of streets that carry local traffic and are maintained by cities and counties. The argument Alon is debunking is that having less roadway and sidewalks due to density would meaningfully lower taxes. But the interstate highways are not tied to density, two cities a thousand km apart will have 1000 km of interstate between them regardless of if they are dense or sprawling. So more spending on interstates in Montana because it is wide isn’t somehow subsidizing low density urbanism in Bozeman.

I don’t know how it works in the US, but in Canada, highways are a provincial jurisdiction, and cities definitely try to get Provinces to add lanes and interchanges in order to facilitate traffic growth which is entirely within city boundaries.

https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/state-federal-aid-reliance-2020/

What is a good example of a high density, low tax, highly developed city — that is not funded by oil and gas wealth? Kowloon Walled City comes to mind. A project for a rainy day would be to gather that data and see if any interesting clusters come up.

Kowloon Walled City was not at all “highly developed”; it was a shanty in a city that at the time was not really first-world but middle to upper middle income.

Hong Kong and Singapore do have low taxes, but that’s not the efficiency of density but rather authoritarian tolerance for very high inequality; you can keep taxes low if you’re fine with septuagenarians having to clean tables at food courts to make a living.

In Hong Kong, it’s common for elderly people who aren’t in public housing to use their meager welfare payment to rent in Shenzhen, while going to Hong Kong for healthcare. I wouldn’t be surprised if something similar happens with Singapore and Johor Bahru. Singapore also gets hundreds of thousands of Malaysians who cross the border daily to work because of their weak currency. You are technically legally obligated to pay maintenance take care of your parents in Singapore (Maintenance of Parents Act), and your parents can sue you. Singapore also has a compulsory savings/pension plan (CPF) where you are required to put a large amount of your income. It might only be possible to have a weaker welfare state with a culture of filial piety, high % in public housing, and a lower COL middle-income area across the border. The high density means you can go from another region to anywhere in HK/SG in an hour, which enables a lot of residents/workers to not actually have to live in HK/SG. Those who do live there can also frequently consume services outside HK/SG because of the density.

It’s more rare to do this in the U.S. as the border areas of Mexico tend to be violent and the language/culture has more of a contrast.

I looked up Monaco and it doesn’t fit the bill as well (medium taxes), but to be fair it doesn’t have a medium income country next door like Singapore or HK do.

Alon, I was thinking of development in terms of physical plant type things and density, agree that Kowloon walled city was run down.

Besides roads, utilities are also highly dependent on sprawl.

Policing might depend somewhat on sprawl in the sense that policing a larger area requires more staff.

roads an utilities are mostly dependent on traffic. Sure there are more miles of cars and lines in rural areas, but they carry much less cars/power. The cost to serve cars/electrons is far more than the cost to serve more distance for both. While not free, rural areas are a lot cheaper than the population would suggest because the cost for usage of a road/line is the majority of the costs of it, and not the cost of the physical road/line. (this does not apply to phone because there you have a wire to each house – but phones of that type are obsolete these days)

roads an utilities are mostly dependent on traffic.

The cost to serve cars/electrons is far more than the cost to serve more distance for both.

This is not at all true, in fact it is almost the complete opposite. A two lane road cost the same per km to build (things like terrain and soil type being equal) regardless of whether it carries 100 cars per day or 10,000. Greater traffic can lead to greater wear and maintenance cost, but this pales in comparison to the capital cost and a rural road used by 100 heavy trucks sees far more damage than an urban one used by thousands of cars. Some wear is weather related and a road used by zero cars will eventually need replacing just from the sun and rain.

Same for electricity. A power line of same voltage/rated current costs the same to build and requires the same maintenance cost whether every home connected to it has its lights on or if it is connected to nothing (the exception I suppose being disaster related expenses, a line with no power cannot suffer a blown transformer, for instance).

A road does cost similar to build per km. However those costs are paid once, there are continuous maintenance costs that are about traffic and there your city streets lose. Now there are plenty of dead end streets in cities that get little traffic, but any secondary road in your city will get far more trucks than the rural secondary roads. (rural primary highways get a lot of trucks but most of them are city to city)

similar for power lines, they need a lot of expensive transformers. which is population related.

Being paid once doesn’t make them small. Those costs might have to be amortized over a very long period of time depending upon utility regulation.

That doesn’t matter as all the amortization is over. The US was mostly electrified by 1960 including rural areas. (according to Wikipedia). Roads were generally built by the first settlers so 1800s. Today nobody is amortizing initial builds and we can ignore that as it isn’t a factor in anyone rural government taxes. Once in a while they build a new “bypass” which is of course a new road but this is a small portion of road budgets. They sometimes call in engineers to redo a short section that has been a problem, but generally the road bed itself is still good enough so all you do is fix potholes every year. Gravel roads get new gravel once in a while. Paved roads have the pavement replaced (20-60 years depending on usage and pavement type) but at a much lower cost.

Perhaps where you live in America, but where I am in Canada, cities and provinces are still spending considerable amounts on greenfield construction of entirely new roads and major thoroughfares (greenfield), in addition to other infrastructure for major housing developments. If populations and electrical loads have been stable for a long time, maybe, but our local population has doubled since 1990.

This is complex. You are correct (and to the extent you are I stand corrected) that as population grows (particularly in cities which can grow even while the nation itself shrinks) more infrastructure is needed. However the majority of land in a city is not this new development and so the costs are depreciated.

Where I live most of the new infrastructure is not paid for by governments. A developers builds the roads and puts in the utilities at their own expense. Then they sell the lots and turn the infrastructure over to the city or utility at no charge. There are still larger highways that need to be built, but they tend to follow the path of existing rural roads and so don’t need as much development (depending on if they add lanes or not)

Policing is mostly proportional to population. Rural areas get much less police officers. Cities often find it useful to have extra police driving around watching for crime (realistically enforcing speed limits). Because of density the share of this cost per person is low, while in a rural area it is high enough to not be worth it.

Policing is more interesting. Above some density, it becomes viable to have some policemen patrol not in cars, but on foot or bicycle. (One assumes that the different postings would be rotated.) This would:

– cure the “windshield perspective” of policemen.

– However kitschy and stereotypical the scene of “greeting the kindly retiree on the porch every day” is, the police would have non-job-related interactions with locals. Compare how they react when their regular donut shop gets robbed vs. any other business.

The article also mentions the proof-of-parking system, which creates some nobody-did-anything-wrong administrative work. It doesn’t mention it, but elsewhere I’ve read that these police boxes also function as the local lost-and-found office. These are in a separate paragraph, because they are less related to density and more a matter of how various tasks are allocated between organizations and people, “diluting” the tasks of policemen.

Of course, exactly none of these address several other known issues, some of which e.g. understandably make American police unusually trigger-happy.

Healthcare and schools are cheaper to provide in a denser environment as well.

As I am sure is adult and child social care.

Those are big budget items.

The costs of schools are so dominated by scale-invariant things like teacher pay, administrator pay, and facilities, that “cheaper to provide in a denser environment” requires very strong evidence and I’m not seeing it. That’s certainly not seen within the US; central cities have extensive leakage problems and toleration of Karenish parents suing the schools, creating a lot of cost inefficiency. Within Europe, is it really cheaper to provide education in Spain and Greece than in lower-weighted-density countries? Rich Asia has lower educational expenses than the West and high quality, but much of it is due to private expenses on cram schools and private tutoring (Singaporean discourse on education holds that Singapore has the world’s highest private tutoring spending as a % of GDP), plus higher prestige for teachers in addition to pay (which is okay but not amazing); this is not because it has denser, bigger cities.

Health care, same thing. The salient difference between the US and the rest of the developed world is not sprawl. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have comparable levels of sprawl. Finland, Sweden, and Norway do not, but do have low density in the sense that towns at smaller scale than would support a hospital are far from one another; Swedish counties tasked with providing health care services have to deal with fairly long travel distances. Sprawl is not why not a single American jurisdiction has universal health care, no matter how left-wing or wealthy; New York manages not to have passed a city- or statewide program even with high density and no Republican Party worth speaking of.

Assuming equivalent income of the area schooling in rural Britain is definitely more expensive to provide. A primary school of 100 kids is more expensive to run than one of 300.

And you are more likely to need (more) buses to get kids to school etc.

Sure, but your school of 300 has 3 times as many residents and so the per person costs are similar. Yes you do need more buses, but the cost of a bus is small fraction of the costs of teachers and other staff. Rural areas tend to have lower costs of living and so even though you are paying for a bus you more than make up for that by paying teachers less.

The 100 person school will probably have smaller class sizes, still have a headteacher, still have any other fixed school running costs such as space for outdoor play etc.

Where I’m from there are lots of schools with fewer than 100 students, and the fixed costs are definitely a large problem and many rural schools are at risk of closure even though they receive approximately the same funding as schools in cities and populations are not shrinking in rural areas, as are the transportation costs to school, whether borne privately (driving) or publicly (bussing).

Hawaii tried. So did Vermont. I’m not in the mood to dig around to figure out how the Republicans screwed it up. Probably something about Commmmmunism!!!! death panels and the freedom to choose dying because you were uninsured. They’ve been beating those drums since at least 1961.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Reagan_Speaks_Out_Against_Socialized_Medicine

There is a copy of it on YouTube if you want to listen to it.

They’ve been trying to repeal the New Deal since 1933. And anything that would extend it.

Vermont and Hawaii are both small, poor, and old; the real prizes are large, rich states that aren’t abnormally old, like New York, California, and Massachusetts.

You are moving the goalposts.

Vermont has been a state since 1791. The 14th to join the union. Hawaii has been one since 1959.

…. and almost all old people have single payer universal health care. That according to Saint Ronnie of Reagan was going to turn us all into to SooooooooCialiSsssssssssssssts. Medicare.

What is ‘normally” old?

The taxes people pay (income, residential property) don’t pay the bills. The cost of schools and police/fire exceed this money. “Rich” places get money from businesses. The bigger the business, the better. Go to Silicon Valley. The “rich” cities have the corporate headquarters, and those cities are more than happy to have the San Jose’s of the world deal with the money-losing headaches. Just ask the civil servants — they want the city where they work to have maximum income. Check out Bell, California — an industrial city of 33,000 that could afford to pay the mayor $800,000, the city manager $700,000, the chief of police $450,000 (with a contractually pre-agreed-to disability pension), with two more city employees making more than $400,000 per year and three making more than $200,000.

It depends on where. In California, yes, this is right. But that’s because Californian property taxes are a joke; in the Northeast, rich suburbs get money from residential property taxes, while New York has 96022727.4 different taxes, some transparent (there’s a city income tax), some not (financial transaction taxes and various MTA-specific taxes falling on whichever industry is worst at lobbying the state government).

Maybe the businesses wanted the extra specialness that comes with high paid public employees. While very technically businesses don’t have any say in the local government since they are major taxpayers they get particularly good attention from the municipality.

There is an important factor when it comes to comparing urban and rural “scale invariant” costs — recruitment. It is generally much easier to recruit teachers, doctors, and administrators to a big city than to a pastoral town, and many countries have ways to attempt to balance this with money. Also, it may cost the same to have all students in one science class versus allowing options of a more advanced chemistry class for example (at same number of students per teacher and same teacher salary) but the educational outcomes are different. One last thought — surely rural students have much higher private and public (where provided) transport costs.

Or, to put it another way — need for health and education scale linearly with population, but quality of education/healthcare and providers thereof likely are not scale invariant. Exceptions for prestigious university towns and large cities with particularly bad reputations, probably.

Sort of. At least in Germany, there are real problems with quality of service in peripheral areas, but they’re more like “people who grow up in rural Thuringia don’t really learn English because every fluent speaker prefers to live not in rural Thuringia.” They’re not really about sprawl; the suburban sprawl in Bavaria has well-regarded schools. This distinction between sprawl and rurality is also seen in the US – white flight suburbs don’t have trouble recruiting teachers, to the point that there have to be government incentives for teachers to go into inner-city districts rather than into the places that Strong Towns derides as a growth Ponzi scheme. To first order, none of this matters; what matters is area wealth, general quality of government, and left-right tradeoffs.

Good point about suburban schools often being considered good, though I do want to note that cities like San Francisco or Mexico city have much more specialised schools than any suburb I’ve ever heard of, e.g. arts high schools. This applies to healthcare as well, it can be hard to justify expensive equipment and specialists — this can be compensated by wealth and doctors having multiple offices however.

Density buys you the ability to have more classes. In rural schools all boys must play football (which is a dangerous sport that shouldn’t be allowed in school IMO), it doesn’t matter how much you hate it, if you don’t take a position on the team there isn’t a enough players to field a full team and so nobody can play (and over course too bad if you want to play a different sport as we can’t create a second sport). In rural schools you get one science teacher, from 7th to 12th grade, an everyone in your grade takes the same class. In denser schools you get the option of advance biology or basic biology – one aimed at those who need biology in college (mostly medical students) while the other meets the minimum state requirements to graduate. Similar for other subjects, density gives more options and in turn gives the smarter students an advantage.

Though there is a good point made that having to compete against better students gives better outcomes for the worse students. An I’d consider things like art high schools too specialized for that reason. While there is an advantage to getting only smart people in a class, it does create its own echo chamber.

Henry, I’m not sure having high and low performers in the same class works that way — my understanding is that the high performers end up helping to teach, basically. Not sure what benefits society more, though personally I think having specialisation is good as long as there is still some element of liberal arts, at a secondary and tertiary education level (and graduate education may need some professional ethics I suppose).

The benefit of density in allowing more educational opportunities can also be obtained by spending a lot of money of course, as I previously noted. But unless you’re doing that across the whole country, that creates inequalities that are even worse as far as I can tell. The UK public schools, US elite college preparatory schools, and similar represent the worst sort of opportunity hoarding.

Henry, assuming that by “football” you mean American football rather than soccer, isn’t it just a bad sport all around, with the inability of rural schools to support anything else a result of (in part) the fact that an American football team has 11 “offense” players and a completely separate 11 “defense” players?

Ok, so there’s something I don’t understand.

If transport infrastructure is so cheap, how we keep hearing about roads and bridges falling apart, and high speed rail projects’ costs balooning and getting cancelled? I’m not saying you’re wrong about this, just that I’m confused.

It’s cheap relative to income, not relative to utility. At InnoTrans, I made an active effort to avoid eating their lunches, because those 16€ dishes, while cheap compared with my annual income, are expensive compared with the quality of the food (which is fast food of the type I get for 5€ outside the conference).

I’m not sure I agree with this. Failing infrastructure might be pretty expensive; a cursory search found this: https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/civil-engineering-source/article/2021/02/01/failing-infrastructure-costing-families-3300-a-year-new-asce-report-says/ — so fixing the infrastructure would be cheap (likely less than 3300 in taxes) vs the utility (3300). But of course this will vary by locality; the US is fairly dysfunctional as regards infrastructure, but middle of the pack globally including places such as the DRC.

Part of bridges falling apart is a talking point not in power politicians like to make because it sounds really bad and there is some truth behind it – but in reality it is not that bad. What is really happening is a bridge gets to end of life and the engineers say we either need to spend $1 million to replace it, or put weight limits on it. On a major highway the decision is always made to replace it. However there are a lot of rural tertiary roads that see 5 cars on a typical day (all who live near it), so the politicians make the decision to put up a weight limit sign and save the money – the dozen trucks per year (those farmers hauling their grain to town) that would use the bridge now need to take a detour which costs them an extra 20 minutes but everyone is fine. The other option isn’t to replace this bridge, it is to tear it down and now those locals who do use it have to take the extra 20 minute detour to town as well. But of course every few years someone looks at numbers and is able to make a big political advertisement about fixing our failing infrastructure. Sometimes they even get elected and put some money to replace some of these worn out bridges that are of questionable value to the state.

Note that bridges have a lifespan of 40 to 60 years (depending on the design, check with your local engineer). So the above cycle will constantly repeat for as long as you live. Engineers are very good at figuring out what is safe, but every once in a while they are wrong and a bridge collapses to large new articles and this gives plenty of reason for politicians to shout about infrastructure.

As Alon points out, the total cost of infrastructure isn’t that large. So if you win some money you can point to numbers changing and say you made a difference – reelect me, and nothing is really controversial. Try to talk about Abortion, health care, taxes, or any other major issue and you will turn off someone who would otherwise support you. Bridges are not very controversial until you are trying to make the hard budget decisions and have to cut a few hundred million from someplace or raise taxes.

Related to this is that very often lists of “deficient” bridges, etc. include structures that are not meeting a book value, even if it is structurally fine. I.e. if the “design life” is 60 years and the bridge is 62 years old it shows up on the list as ‘deficient’ even if there are no cracks. Even things like a 23 year old bridge with original pavement can show up as deficient if the standard is to replace asphalt every 20 years. Worst of all is if a bridge was designed for a level of service of 10,000 cars per day but is actually used by 12,000 – in that case a brand new bridge can be recorded as “functionally obsolete”. Downloading a list of structures with any such code on them is how infrastructure reports can make it seem as if almost every piece of infrastructure is “in need of repair” “obsolete” or “not meeting structural standards”.

I agree that Strong Towns is likely overreaching with their pro-density arguments, but that does not mean density has no impact on municipal finances.

Property taxes, impact fees, and local option taxes (like meals and room) are essentially the only streams of income available for municipalities unrelated to state or federal aid. In many places in the US, state governments are actively hostile to cities and provide no funding for capital projects, particularly anything that’s not road maintenance. Municipalities can circumvent this through federal grants, but these are dependent on the national legislature’s capacity to fund such programs and municipalities’ capacity to win competitive awards.

If a pro-urbanism town wants to chart a course in an anti-urban state, they need to raise revenue independently. There are obviously many ways to do this, but densification/economic development is one of them. I’d also point out that towns must balance their annual budgets, and this process affects their credit rating. A higher rating allows them to bond more.

Final thing I’ll say – indirectly, density helps with service provision. The last town I lived in had a severe housing shortage and thus could not recruit municipal workers for basically every department.

Metro Vancouver put out a study that examines this. Something like cost to provide services to different residential density types.

By the analysis of the Chicago Public Schools, it spends an average of $18,287 per student. The Douglas Academy is a high school with a total enrollment of 33 students, and CPS spends $68,000 per student, and the Simpson Academy for Young Women with 27 total enrollment has CPS spend $94,000 per student. The low enrollment schools can’t be closed because former mayor (and former Obama press secretary) Rahm Emmanuel closed 50 schools in 2013 due to low enrollment, but under a consent decree to not close any more schools until 2025.

My guess is that there’s a U-curve to the costs of roads and utilities depending on density. In very rural areas, a 2-lane road won’t be fully used during peak hours, while in suburbia it probably will. Similarly, infrastructure costs for utilities are high in NYC (that portion of the electricity bill is high, probably because tearing up roads to fix things gets complex) as well as for rural areas. But it’s probably best in places that have low-rise apartments or townhomes. In my experience, retrofitting sidewalks and improving water utilities get more expensive in low-density suburbia compared to higher density suburbia because you need more meters per capita. But these aren’t really that expensive compared to the total government budget. Even poor countries like Rwanda can afford nice sidewalks, and water utilities are only a small portion of income. And it’s not like we will need much more sidewalk or residential water as society gets richer, so there’s a limit to how much these costs can grow.

The trend has been towards better technology for rural/low-density utilities such as residential/microgrid solar+batteries+backup for electricity and starlink for internet/direct-to-cell.

In the suburbs you have very lightly used two-lane roads that don’t go anywhere and very busy four lane roads that everyone takes. there are a few two lane roads that are heavily used, but generally the roads will be 4+ lanes or lightly used because they don’t go anywhere. In rural areas the paved roads don’t really have a peak, they are used all day, and gravel roads are used rarely. Although rural areas have a large portion of their traffic in the form of heavy trucks, I think overall those city streets see more total trucks (this needs numbers that I’m sure someone has but I don’t know how to find).

I fully agree there is a U curve on costs on utilities. However a large part of the cost of a utility is in equipment that depends usage and not km of line or customer count. Rural customers are also more likely to have a generator to ride out weeks of the power being out (a a significant portion of the cost of a generator is the engine – they have a tractor to supply the engine so the rest is somewhat cheap – combine that what some things being critical to keep running and many will have their own power backup anyway so a week without power is just more expensive but otherwise not a big deal), which in turn means utilities can use cheaper maintenance practices which overall save money put mean when a storm happens it is a couple weeks to get power back to everyone.

I specifically didn’t include electricity as that is dependent more on usage compared to something like sidewalks where over-utilization is rare outside of certain very dense areas. In some areas it might be cheap as it’s close to a source (hydroelectric dams, desert land for solar, windmills, or natural gas). The issue of storms is probably regional, there are many areas where that is unlikely to take out electricity. There are a lot of factors involved unrelated to density.

Actual data in the us suggests that electricity is relatively cheap to supply (both energy and transmission infrastructure) to rural areas (in the mainland U.S.) and greenfield exurbs. It is most expensive in denser places like California and NYC.

“Transportation costs are a small share of GDP; in the US, an extreme case in road costs, they’re 2% of federal spending and 5.6% of subnational spending, which averages out to somewhat more than 3% of GDP.”

Should that second GDP be “government spending” or similar? 3% of GDP seems like. . . a lot, and also inconsistent with the rest of the sentence.

It’s 4.1% of government spending here FYI.

…yes, it’s 3% of government spending, so around 1.3% of GDP, sorry.

Good article! I think you are right, but with the caveat that city design and transportation might have a very significant indirect impact on things like health, elder care, and segregated schools.

What makes this possible is the fact that federal taxes get redistributed to municipalities via formula funding.

Strong Towns ideology says that this should not ever happen.

In addition, I don’t think this is ever said explicitly, but a well run dense city should be able to pay people less money because of more efficient development patterns, so teacher salaries wouldn’t have to be as high as they are.

a well run dense city should be able to pay people less money because of more efficient development patterns

This doesn’t make any sense, salaries will respond to supply and demand, not to how efficiently the city is laid out. More efficient development pattern could theoretically reduce government spending (although Alon’s whole thesis here is that is does not do so meaningfully) but would do nothing to affect personal income.

Empirically there is nothing to support this, you can either argue that salaries increase with density (looking at high places like SF, Boston, Stamford/Bridgeport) or that there is no correlation (looking at NY & LA not being highest income, and or microareas like Heber Utah being very high income.

The diagram is mostly used to discuss municipal taxes and in that case it’s very accurate. It’s not wrong, it just needs to be used within its proper context. Strong Towns focuses on municipal financing and local urban planning policy decisions. It’s still correct if you know anything about municipal finance and property tax assessment.

It’s only true of municipal finance if you don’t take school and police funding into account.

Well, where I’m from in Canada the police and school funding is outside of municipal control so the diagram still holds true here.

Okay, so it holds true in an environment in which municipalities are not powerful when it comes to taxation and spending, because most issues that people care about are decided at the provincial and federal levels.

The difference between ~3% of GDP (US) and 0.5% of GDP (US) is a tax rise / tax cut magnitude that moves elections.

The last U.S. election shows that it’s not taxes or the economy more generally or even governing ability. Or foreign policy or any of the other issues many many people lie to pollsters about. That is partially because the pollsters don’t ask the questions.