Category: Amtrak

Fares on High-Speed Trains

American journalists sometimes ask me to discuss high-speed rail fares. I’ve written from time to time about how Northeast Corridor fares are significantly higher than French, German, and Japanese high-speed rail fares, but the links to this information are never in the same place. The purpose of this post is to collect all the links together for easy retrieval, with updates to the 2020s whenever possible. Unfortunately, international high-speed rail fares connecting to France are also much higher than domestic ones, which contributes to the poor ridership of those trains relative to city size.

France

ARAFER releases statistics annually. The most recent year for which there is data is 2022; here’s the report in French, and here’s a summary in English. The relevant information is in sections 5-6. The TGV system including international trains averages fare revenue of 6,213M€ for 61 billion passenger-km; in English this is called “non-PSO,” since these are the profitable trains that SNCF runs outside the passenger service obligation system for money-losing slow trains. This works out to 0.102€/p-km. The PPP rate these days is about 1€ = $1.45, making this about $0.15/p-km.

The split between domestic and international trains is large, and the French report has the domestic trains as just 0.093€/p-km, taking a weighted average from pp. 23 and 31. Nominal fares per p-km on domestic TGVs were down 4% from 2019 to 2022, despite 7.5% cumulative inflation over this period.

The international trains, in contrast, are much more expensive: the report doesn’t give exact numbers, but from some weighted averaging and graph eyeballing it looks like it’s around 0.17€/p-km. The all-high-speed international trains – Eurostar and Thalys – are more expensive than the trains running partly at low speed in Germany and Switzerland, like Lyria; this big difference in fares helps their disappointing ridership. Domestic TGVs run from Paris to Lyon 28 times on the 5th of June this year, counting only trains to Lyon Part-Dieu or Perrache, which do not continue onward, and not counting trains that stop at Saint-Exupéry on their way to points south, and those trains are rather full 16-car bilevels. In contrast, on the same day I only see 16 Eurostars from London to Paris. This is despite the fact that London is a far larger city than Lyon, and the in-vehicle travel time is only moderately longer.

Germany

Germany lacks France’s neat separation of low- and high-speed trains. The intercity rail network here is treated as a single system, and increasingly all trains are ICEs even if they spend the majority of the trip on legacy lines at a top speed of 200 km/h.

Overall intercity rail passenger revenue here was 5.1 billion € in 2022; the expression to look for is “SPFV.” Ridership was 42.9 billion p-km per a DB report of 2022-3, PDF-p. 7, averaging 0.119€/p-km, which is $0.17/p-km in PPP US dollars. 2022 was still slightly below 2019 levels, when ridership was 44.7 billion p-km and fares averaged 0.112€/p-km; the three-year increase was less than the cumulative inflation over this period, which was 10.3%.

Japan

Japanese fares are higher than European fares on high-speed rail. JR East’s presentation from 2021, showing depressed ridership during the pandemic (p. 50), reports ¥189.6 billion in Shinkansen revenue on 7.95 billion p-km, or ¥23.8/p-km, and projects recovery to ¥428.9 billion/17.313 billion p-km by 2022, or ¥24.8/p-km. JR Central’s 2020 report says (p. 37) that its Shinkansen service got ¥1.2613 trillion in revenue in the year ending March 2020 on 54.009 billion p-km, or ¥23.4/p-km. JR West’s 2020 factsheets for revenue and ridership show ¥457 billion/21.338 billion p-km in 2019, or ¥21.4/p-km.

The PPP rate for 2020-1 was $1 = ¥100. Taking 9% dollar inflation from 2020 to 2022 into account, this is, in 2022 prices, around $0.25/p-km.

Northeast Corridor

Amtrak publishes monthly performance reports; the fiscal year is October-September, so the September reports, covering an entire fiscal year, are to be preferred. Here are 2022 and 2023; 2022 still shows a considerable corona depression, unlike in France and Germany. The 2023 report shows that Northeast Corridor revenue splits as $495.9 million/581.1 million p-miles Acela, or $0.53/p-km, and $768.2 million/1.6269 billion p-miles Regional, or $0.293/p-km Regional. Altogether, this is $0.356/p-km, which is nearly 50% higher than the Shinkansen, 2.1 times as expensive as the ICE, and 2.4 times as expensive as the TGV.

Discussion

High operating costs on Amtrak are the primary reason for the premium fares. The mainland JRs are all highly profitable; DB Fernverkehr is profitable, as is the TGV network (though SNCF writ large isn’t, the slow intercities falling under the PSO rubric). All five companies pay track access charges for the construction of high-speed rail infrastructure; the ARAFER report goes over these charges in France and a selection of other European countries, designed to prevent state subsidies to intercity rail operations through underpriced track access, since track construction is always done by the state but operations may be done by a private operator or a foreign state railway. The Northeast Corridor is profitable as well – Amtrak doesn’t have to pay track access charges, but the access charges for legacy 19th-century lines would not be significant. However, if Amtrak charged European fares or even Japanese ones, it wouldn’t be. Northeast Corridor rail operations in fiscal 2023 earned $1.266 billion in passenger revenue plus $28.5 million in non-ticket revenue but spent $1.0917 billion, or $0.307/p-km.

A portion of the Amtrak cost premium also comes from adversarial profit maximization, also seen on Thalys and Eurostar. The domestic TGVs and ICEs aim at making a base rate of profit while providing a service for the general public; SNCF doesn’t apply the same logic to Thalys and Eurostar and instead aims at serving only business trips to avoid the possibility of extracting less than maximum fares from international travelers. On Amtrak, the need to subsidize the rest of the system has increased Northeast Corridor fares, though to be clear, in fiscal 2023 the operating margin was small enough that this is at most a secondary factor. Performance reports from the 2000s and 10s showed a larger operating margin, but criticism from advocacy groups centering non-Northeast Corridor passengers alleging that Amtrak accounting was making the Northeast Corridor look better and the night trains look worse led to a recalculation, used in the most recent reports, in which Northeast Corridor operations still turn out to be profitable but not by a large margin.

Intercity Trains and Long Island

Amtrak wants to extend three daily Northeast Corridor trains to Long Island. It’s a bad idea – for one, if the timetable can accommodate three daily trains, it can accommodate an hourly train – but beyond the frequency point, this is for fairly deep reasons, and it took me years of studying timetabling on the corridor to understand why. In short, the timetabling introduces too many points of failure, and meanwhile, the alternative of sending all trains that arrive in New York from Philadelphia and Washington onward to New Haven is appealing. To be clear, there are benefits to the Long Island routing, they’re just smaller than the operational costs; there’s a reason this post is notably not tagged “incompetence.”

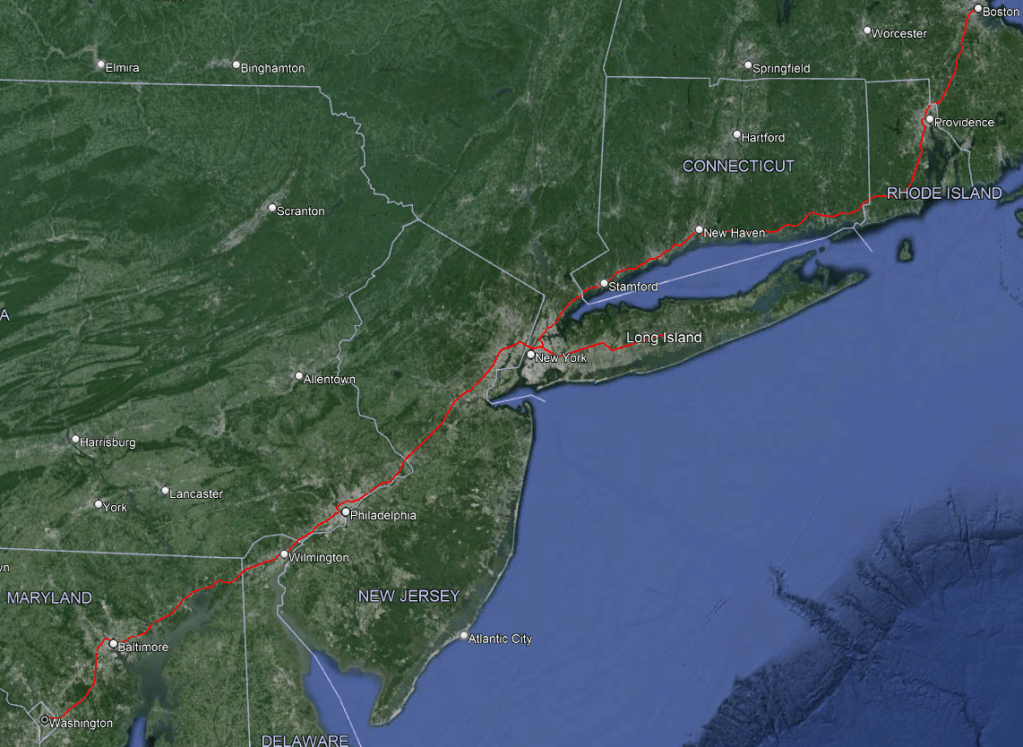

How to connect the Northeast Corridor with Long Island

The Northeast Corridor has asymmetric demand on its two halves. North of New York, it connects the city with Boston. But south of New York, it connects to both Philadelphia and Washington. As a result, the line can always expect to have more traffic south of New York than north of it; today, this difference is magnified by the lower average speed of the northern half, due to the slowness of the line in Connecticut. Today, many trains terminate in New York and don’t run farther north; in the last 20 years, Amtrak has also gone back and forth on whether some trains should divert north at New Haven and run to Springfield or whether such service should only be provided with shuttle trains with a timed connection. Extending service to Long Island is one way to resolve the asymmetry of demand.

Such an extension would stop at the major stattions on the LIRR Main Line. The most important is Jamaica, with a connection to JFK; then, in the suburbs, it would be interesting to stop at least at Mineola and Hicksville and probably also go as far as Ronkonkoma, the end of the line depicted on the map. Amtrak’s proposed service makes exactly these stops plus one, Deer Park between Hicksville and Ronkonkoma.

The entire Main Line is electrified, but with third rail, not catenary. The trains for it therefore would need to be dual-voltage. This requires a dedicated fleet, but it’s not too hard to procure – it’s easier to go from AC to DC than in the opposite direction, and Amtrak and the LIRR already have dual-mode diesel locomotives with third rail shoes, so they could ask for shoes on catenary electric locomotives (or on EMUs).

The main benefit of doing this, as opposed to short-turning surplus Northeast Corridor trains in New York, is that it provides direct service to Long Island. In theory, this provides access to the 2.9 million people living on Long Island. In practice, the shed is somewhat smaller, because people living near LIRR branches that are not the Main Line would be connecting by train anyway and then the difference between connecting at Jamaica and connecting at Penn Station is not material; that said, Ronkonkoma has a large parking lot accessible from all of Suffolk County, and between it and significant parts of Nassau County near the Main Line, this is still 2 million people. There aren’t many destinations on Long Island, which has atypically little job sprawl for an American suburb, but 2 million originating passengers plus people boarding at Jamaica plus people going to Jamaica for JFK is a significant benefit. (How significant I can’t tell you – the tools I have for ridership estimation aren’t granular enough to detect the LIRR-Amtrak transfer penalty at Penn Station.)

My early Northeast Corridor ideas did include such service, for the above reasons. However, there are two serious drawbacks, detailed below.

Timetabling considerations

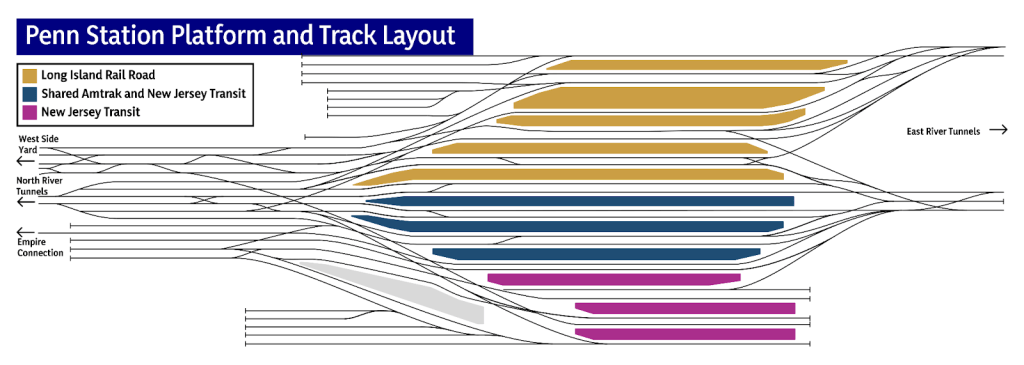

Under current plans, there is little interaction between the LIRR and the Northeast Corridor. There are two separate routes into Penn Station from the east, one via 32nd Street (“southern tunnels”) and one via 33rd (“northern tunnels”), each a two-track line with one track in each direction. The North River Tunnels, connecting Penn Station with New Jersey and the rest of the United States, face the southern tunnels; the Gateway tunnels under construction to double trans-Hudson capacity are not planned to pair with the northern tunnels, but rather to connect to stub-end tracks facing 31st Street. For this reason, Amtrak always or almost always enters Penn Station from the east using the southern tunnels; the northern tunnels do have some station tracks that connect to them and still allow through-service to the west, but the moves through the station interlocking are more complex and more constrained.

As seen on the map, east of Penn Station, the Northeast Corridor is to the north of the LIRR. Thus, Amtrak has to transition from being south of the LIRR to being north of it. This used to be done at-grade, with conflict with same-direction trains (but not opposite-direction ones); it has since been grade-separated, at excessive cost. With much LIRR service diverted to Grand Central via the East Side Access tunnel, current traffic can be divided so that LIRR Main Line service exclusively uses the northern tunnels and Northeast Corridor (Amtrak or commuter rail under the soon to open Penn Station Access project) service exclusively uses the southern tunnels; the one LIRR branch not going through Jamaica, the Port Washington Branch, can use the southern tunnels as if it is a Penn Station Access branch. This is not too far from how current service is organized anyway, with the LIRR preferring the northern (high-numbered) tracks at Penn Station, Amtrak the middle ones, and New Jersey Transit the southern ones with the stub end:

The status quo, including any modification thereto that keeps the LIRR (except the Port Washington Branch) separate from the Northeast Corridor, means that all timetabling complexity on the LIRR is localized to the LIRR. LIRR timetabling has to deal with all of the following issues today:

- There are many different branches, all of which want to go to Manhattan rather than to Brooklyn, and to a large extent they also want to go on the express tracks between Jamaica and Manhattan rather than the local tracks.

- There are two Manhattan terminals and no place to transfer between trains to different ones except Jamaica; an infill station at Sunnyside Yards, permitting trains from the LIRR going to Grand Central to exchange passengers with Penn Station Access trains, would be helpful, but does not currently exist.

- The outer Port Jefferson Branch is unelectrified and single-track and yet has fairly high ridership, so that isolating it with shuttle trains is infeasible except in the extreme short run pending electrification.

- All junctions east of Jamaica are flat.

- The Main Line has three tracks east of Floral Park, the third recently opened at very high cost, purely for peak-direction express trains, but cannot easily schedule express trains in both directions.

There are solutions to all of these problems, involving timetable simplification, reduction of express patterns with time saved through much reduced schedule padding, and targeted infrastructure interventions such as electrifying and double-tracking the entire Port Jefferson Branch.

However, Amtrak service throws multiple wrenches in this system. First, it requires a vigorous all-day express service between New York and Hicksville if not Ronkonkoma. Between Floral Park and Hicksville, there are three tracks. Right now the local demand is weak, but this is only because there is little local service, and instead the schedule encourages passengers to drive to Hicksville or Mineola and park there. Any stable timetable has to provide much stronger local service, and this means express trains have to awkwardly use the middle track as a single track. This isn’t impossible – it’s about 15 km of fast tracks with only one intermediate station, Mineola – but it’s constraining. Then the constraint propagates east of Hicksville, where there are only two tracks, and so those express trains have to share tracks with the locals and be timetabled not to conflict.

And second, all these additional conflict points would be transmitted to the entire Northeast Corridor. A delay in Deer Park would propagate to Philadelphia and Washington. Even without delays, the timetabling of the trains in New Jersey would be affected by constraints on Long Island; then the New Jersey timetabling constraints would be transmitted east to Connecticut and Massachusetts. All of this is doable, but at the price of worse schedule padding. I suspect that this is why the proposed Amtrak trip time for New York-Ronkonkoma is 1:25, where off-peak LIRR trains do it in 1:18 making all eight local stops between Ronkonkoma and Hicksville, Mineola, Jamaica, and Woodside. With low padding, which can only be done with more separated out timetables, they could do it in 1:08, making four more net stops.

Trains to New Haven

The other reason I’ve come to believe Northeast Corridor trains shouldn’t go to Jamaica and Long Island is that more trains need to go to Stamford and New Haven. This is for a number of different reasons.

The impact of higher average speed

The higher the average speed of the train, the more significant Boston-Philadelphia and Boston-Washington ridership is. This, in turn, reduces the difference in ridership north and south of New York somewhat, to the point that closer to one train in three doesn’t need to go to Boston than one train in two.

Springfield

Hartford and Springfield can expect significant ridership to New York if there is better service. Right now the line is unelectrified and runs haphazard schedules, but it could be electrified and trains could run through; moreover, any improvement to the New York-Boston line automatically also means New York-Springfield trains get faster, producing more ridership.

New Haven-New York trips

If we break my gravity model of ridership not into larger combined statistical areas but into smaller metropolitan statistical areas, separating out New Haven and Stamford from New York, then we see significant trips between Connecticut and New York. The model, which is purely intercity, at this point projects only 15% less traffic density in the Stamford-New York section than in the New York-Trenton section, counting the impact of Springfield and higher average speed as well.

Commutes from north of New York

There is some reason to believe that there will be much more ridership into New York from the nearby points – New Haven, Stamford, Newark, Trenton (if it has a stop), and Philadelphia – than the model predicts. The model doesn’t take commute trips into account; thus, it projects about 7.78 million annual trips between New York and either Stamford or New Haven, where in fact the New Haven Line was getting 125,000 weekday passengers and 39 million annual passengers in the 2010s, mostly from Connecticut and not Westchester County suburbs. Commute trips, in turn, accrete fairly symmetrically around the main city, reducing the difference in ridership between New York-Philadelphia and New York-New Haven, even though Philadelphia is the much larger city.

Combining everything

With largely symmetric ridership around New York in the core, it’s best to schedule the Northeast Corridor with the same number of trains immediately north and immediately south of it. At New Haven, trains should branch. The gravity model projects a 3:1 ratio between the ridership to Boston and to Springfield. Thus, if there are eight trains per hour between New Haven and Washington, then six should go to Boston and two to Springfield; this is not even that aggressive of an assumption, it’s just hard to timetable without additional bypasses. If there are six trains per hour south of New Haven, which is more delicate to timetable but can be done with much less concrete, then two should still go to Springfield, and they’ll be less full but over this short a section it’s probably worth it, given how important frequency is (hourly vs. half-hourly) for trips that are on the order of an hour and a half to New York.

The Northeast Corridor Rail Grants

The US government has just announced a large slate of grants to rail from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Amtrak has a breakdown of projects both for itself and partners, totaling $16.4 billion. There are a few good things there, like Delco Lead, or more significantly more money for the Hudson Tunnel Project (already funded separately, but this covers money the states would otherwise be expected to fund). There are also conspicuously missing items that should stay missing – But by overall budget, most of the grant is pretty bad, covering projects that are in principle good but far too expensive per minute saved.

This has implications to the future of the Northeast Corridor, because the total amount of money for it is $30 billion; I believe this includes Amtrak plus commuter rail agencies. Half of the money is gone already, and some key elements remain unfunded, some of which are still on agency wishlists like Hunter Flyover but others of which are still not, like Shell Interlocking. It’s still possible to cobble together the remaining $13.6 billion to produce something good, but there have to be some compromises – and, more importantly, the process that produced the grant so far doesn’t fill me with confidence about the rest of the money.

The Baltimore tunnel

The biggest single item in the grant is the replacement tunnel for the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel. The B&P was built compromised from the start, with atypically tight curves and steep grades for the era. An FRA report on its replacement from 2011 goes over the history of the project, originally dubbed the Great Circle Passenger Tunnel when first proposed in the 1970s; the 2011 report estimates the cost at $773 million in 2010 prices (PDF-p. 229), and the benefits at a two-minute time saving (PDF-p. 123) plus easier long-term maintenance, as the B&P has water leakage in addition to its geometric problems. At the time, the consensus of Northeastern railfans treated it as a beneficial and even necessary component of Northeast Corridor modernization, and the agencies kept working on it.

Since then, the project’s scope crept from two passenger tracks to four tracks with enough space for double-stacked freight and mechanical ventilation for diesel locomotives. The cost jumped to $4 billion, then $6 billion. The extra scope was removed to save money, said to be $1 billion, but the headline cost remained $6 billion (possibly due to inflation, as American government budgeting is done in current dollars, never constant dollars, creating a lot of fictional cost overruns). The FRA grant is for $4.7 billion out of $6 billion. Meanwhile, the environmental impact statements upped the trip time benefit of the tunnel for Amtrak from two to 2.5 minutes; this is understandable in light of either higher-speed (and higher-cost) redesign or an assumption of better rolling stock than in the 2011 report, higher-acceleration trains losing more time to speed restrictions near stations than lower-acceleration ones.

That this tunnel would be funded was telegraphed well in advance. The tunnel was named after abolitionist hero Frederick Douglass; I’m not aware of any intercity or commuter rail tunnel elsewhere in the developed world that gets such a name, and the choice to name it so about a year ago was a commitment. It’s not a bad project: the maintenance cost savings are real, as is the 2.5 minute improvement in trip time. But 2.5 minutes are not worth $6 billion, or even $6 billion net of maintenance. In 2023 dollars, the estimate from 2011 is $1.1 billion, which I think is fine on the margin – there are lower-hanging fruit out there, but the tunnel doesn’t compete with the lowest-hanging fruit but with the $29 billion-hanging fruit and it should be very competitive there. But when costs explode this much, there are other things that could be done better.

Bridge replacements

The Northeast Corridor is full of movable bridges, which are wishlisted for replacement with high fixed spans. The benefits of those replacements are there, mainly in maintenance costs (but see below on the Connecticut River), but that does not justify the multi-billion dollar budgets of many of them. The Susquehanna River Rail Bridge, the biggest grant in this section, is $2.08 billion in federal funding; the environmental impact study said that in 2015 dollars it was $930 million. The benefits in the EIS include lower maintenance costs, but those are not quantified, even in places where other elements (like the area’s demographics) are.

Like all state of good repair projects, this is spending for its own sake. There are no clear promises the way there are with the Douglass Tunnel, which promises to have a new tunnel with trip time benefits, small as they are. Nobody can know if these bridge replacement projects achieved any of their goals; there are no clear claims about maintenance costs with or without this, nor is there any concerted plan to improve maintenance productivity in general.

The East River Tunnel project, while not a bridge nor a visible replacement, has the same problem. The benefits are not made clear anywhere. There are some documents we found in the ETA commuter rail report saying that high-density signaling would allow increasing peak capacity on one of the two tunnel pairs from 20 to 24 trains per hour, but that’s a small minority of the overall project and in the description it’s an item within an item.

The one exception in this section is the Connecticut River. This bridge replacement has a much clearer benefit – but also is a down payment on the wrong choice. The issue is that pleasure boat traffic has priority over the railroad on the “who came first” principle; by agreement with the Coast Guard, there is a limited number of daily windows for Amtrak to run its trains, which work out to about an Acela and a Regional every hour in each direction. Replacing this bridge, unlike the others, would have a visible benefit: more trains could run (once new rolling stock comes in, but that’s already in production).

Unfortunately, the trains would be running on the curviest and also most easily bypassable section of the Northeast Corridor. The average speed on the New Haven-Kingston section of the Northeast Corridor is low, if not so low on the less curvy but commuter rail-primary New Haven Line farther west. The curves already have high superelevation and the Acelas tilt through them fully; there’s not much more that can be done to increase speed, save to bypass this entire section. Fortunately, a bypass parallel to I-95 is feasible here – there isn’t as much suburban development as west of New Haven, where there are many commuters to New York. Partial bypasses have been studied before, bypassing both the worst curves on this section and all movable bridges, including that on the Connecticut. To replace this bridge in place is a down payment on, in effect, not building genuine high-speed rail where it is most useful.

Other items

Some other items on the list are not so bad. The second largest item in the grant, $3.79 billion, is increasing the federal contribution to the Hudson Tunnel Project from about 50% to about 70%. I have questions about why it’s necessary – it looks like it’s covering a cost overrun – but it’s not terrible, and by cost it’s by far the biggest reasonable item in this grant.

Beyond that, there are some small projects that are fine, like Delco Lead, part of a program by New Jersey Transit to invest around New Brunswick and Jersey Avenue to create more yard space where it belongs, at the end of where local trains run (and not near city center, where land is expensive).

What’s not (yet) funded

Overall, around 25% of this grant is fine. But there are serious gaps – not only are the bridge replacements and the Douglass Tunnel not the best use of money, but also some important projects providing both reliability and speed are missing. The two most complex flat junctions of the Northeast Corridor near New York, Hunter in New Jersey and Shell in New Rochelle, are missing (and Hunter is on the New Jersey Transit wishlist); Hunter is estimated at $300 million and would make it much more straightforward to timetable Northeast Corridor commuter and intercity trains together, and Shell would likely cost the same and also facilitate the same for Penn Station Access. The Hartford Line is getting investment into double track, but no electrification, which American railroads keep underrating.

Amtrak Releases Bad Scranton Rail Study

There’s hot news from Amtrak – no, not that it just announced that it hired Andy Byford to head its high-speed rail program, but that it just released a study recommending New York-Scranton intercity rail. I read the study with very low expectations and it met them. Everything about it is bad: the operating model is bad, the proposed equipment is bad and expensive, the proposed service would be laughed at in peripheral semi-rural parts of France and Italy and simply wouldn’t exist anywhere with good operations.

This topic is best analyzed using the triangle of infrastructure, rolling stock, and schedule, used in Switzerland to maximize the productivity of legacy intercity line, since Swiss cities, like Scranton, are too small to justify a dedicated high-speed rail network as found in France or Japan. Unfortunately, Amtrak’s report falls short on all three. There are glimpses there of trying and failing, which I personally find frustrating; I hope that American transportation planners who wish to imitate European success don’t just read me but also read what I’ve read and proactively reach out to national railways and planners on this side of the Atlantic.

What’s in the study?

The study looks at options for running passenger trains between New York and Scranton. The key piece of infrastructure to be used is the Lackawanna Cutoff, an early-20th century line built to very high standards for the era, where steam trains ran at 160 km/h on the straighter sections and 110 km/h on the curvier ones. The cutoff was subsequently closed, but a project to restore it for commuter service is under construction, to reach outer suburbs near it and eventually go as far as the city’s outermost suburbs around the Delaware Water Gap area.

Amtrak’s plan is to use the cutoff not just for commuter service but also intercity service. The cutoff only goes as far as the Delaware and the New Jersey/Pennsylvania state line, but the historic Lackawanna continued west to Scranton and beyond, albeit on an older, far worse-built alignment. Thus, the speed between the Water Gap and Scranton would be low; with no electrification planned, the projected trip time between New York and Scranton is about three hours.

I harp on the issue of speed because it’s a genuine problem. Google Maps gives me an outbound driving time of 2:06 right now, shortly before 9 pm New York time. The old line, which the cutoff partly bypassed, is curvy, which doesn’t just reduce average speed but also means a greater distance must be traversed on rail: the study quotes the on-rail length as 134 miles, or 216 km, whereas driving is just 195 km. New York is large and congested and has little parking, so the train can afford to be a little slower, but it’s worth it to look for speedups, through electrification and good enough operations so that timetable padding can be minimized (in Switzerland, it’s 7% on top of the technical travel time).

Operations

The operations and timetabling in the study are just plain bad. There are two options, both of which include just three trains a day in each direction. There are small French, Italian, and Spanish towns that get service this poor, but I don’t think any of them is as big as Scranton. Clermont-Ferrand, a metro area of the same approximate size as Scranton, gets seven direct trains a day to Paris via intermediate cities similar in size to the Delaware Water Gap region, and these are low-speed intercities, as the area is too far from the high-speed network for even low-speed through-service on TGVs. In Germany and Switzerland, much smaller towns than this can rely on hourly service. I can see a world in which a three-hour train can come every two hours and still succeed, even if hourly service is preferable, but three roundtrips a day is laughable.

Then there is how these three daily trains are timetabled. They take just less than three hours one-way, and are spaced six hours apart, but the timetable is written to require two trainsets rather than just one. Thus, each of the two trainsets is scheduled to make three one-way trips a day, with two turnarounds, one of about an hour and one of about five hours.

Worse, there are still schedule conflicts. The study’s two options differ slightly in arrival times, and are presented as follows:

Based on the results of simulation, Options B and D were carried forward for financial evaluation. Option B has earlier arrival times to both New York and Scranton but may have a commuter train conflict that remains unresolved. Option D has later departure times from New York and Scranton and has no commuter train conflicts identified.

All this work, and all these compromises on speed and equipment utilization, and they’re still programming a schedule conflict in one of the two options. This is inexcusable. And yet, it’s a common problem in American railroading – some of the proposed schedules for Caltrain and high-speed rail operations into Transbay Terminal in San Francisco proposed the same.

Equipment and capital planning

The study does not look at the possibility of extending electrification from its current end in Dover to Scranton. Instead, it proposes a recent American favorite, the dual-mode locomotive. New Jersey Transit has a growing pool of them, the ALP-45DP, bought most recently for $8.8 million each in 2020. Contemporary European medium-speed self-propelled electric trains cost around $2.5 million per US-length car; high-speed trains cost about double – an ongoing ICE 3 Neo procurement is 34 million euros per eight-car set, maybe $6 million per car in mid-2020s prices or $5 million in 2020 prices.

And yet somehow, the six-car dual-mode trains Amtrak is seeking are to cost $70-90 million between the two of them, or $35-45 million per set. Somehow, Amtrak’s rolling stock procurement is so bad that a low-speed train costs more per car than a 320 km/h German train. This interacts poorly with the issue of turnaround times: the timetable as written is almost good enough for operation with a single trainset, and yet Amtrak wants to buy two.

There are so many things that could be done to speed up service for the $266 million in capital costs between the recommended infrastructure program and the rolling stock. This budget by itself should be enough to electrify the 147 km between Dover and Scranton, since the route is single-track and would carry light traffic allowing savings on substations; then the speed improvement should allow easy operations between New York and Scranton every six hours with one trainset costing $15 million and not $35-45 million, or, better yet, every two hours with three sets. Unfortunately, American mainline rail operators are irrationally averse to wiring their lines; the excuses I’ve seen in Boston are unbelievable.

The right project, done wrong

There’s an issue I’d like to revisit at some point, distinguishing planning that chooses the wrong projects to pursue from planning that does the right projects wrong. For example, Second Avenue Subway is the right project – its benefits to passengers are immense – but it has been built poorly in every conceivable way, setting world records for high construction costs. This contrasts with projects that just aren’t good enough and should not have been priorities, like the 7 extension in New York, or many suburban light rail extensions throughout the United States.

The intercity rail proposal to Scranton belongs in the category of right projects done wrong, not in that of wrong projects. Its benefits are significant: putting Scranton three hours away from New York is interesting, and putting it 2.5 hours away with the faster speeds of high-reliability, high-performance electric trains especially so.

As a note of caution, this project is not a slam dunk in the sense of Second Avenue Subway or high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor, since the trip time by train would remain slower than by car. If service is too compromised, it might fail even ignoring construction and equipment costs – and we should not ignore construction or equipment costs. But New York is a large city with difficult car access. There’s a range of different trips that the line to Scranton could unlock, including intercity trips, commuter trips for people who work from home most of the week but need to occasionally show up at the office, and leisure trips to the Delaware Water Gap area.

Unfortunately, the project as proposed manages to be both too expensive and too compromised to succeed. It’s not possible for any public transportation service to succeed when the gap between departures is twice as long as the one-way trip time; people can drive, or, if they’re car-free New Yorkers, avoid the trip and go vacation in more accessible areas. And the sort of planning that assumes the schedule has conflicts and the dispatchers can figure it out on the fly is unacceptable.

There’s a reason planning in Northern Europe has converged on the hourly, or at worst two-hourly, frequency as the basis of regional and intercity timetabling: passengers who can afford cars need the flexibility of frequency to be enticed to take the train. With this base frequency and all associated planning tools, this region, led by Switzerland, has the highest ridership in the world that I know of on trains that are not high-speed and do not connect pairs of large cities, and its success is slowly exported elsewhere in Europe, if not as fast or completely as it should be. It’s possible to get away without doing the work if one builds a TGV-style network, where the frequency is high because Paris and Lyon are large cities and therefore frequency is naturally high even without trying hard. It’s not possible to succeed on a city pair like New York-Scranton without this work, and until Amtrak does it, the correct alternative for this study is not to build the line at all.

Philadelphia and High-Speed Rail Bypasses (Hoisted from Social Media)

I’d like to discuss a bypass of Philadelphia, as a followup from my previous post, about high-speed rail and passenger traffic density. To be clear, this is not a bypass on Northeast Corridor trains: every train between New York and Washington must continue to stop in Philadelphia at 30th Street Station or, if an in my opinion unadvised Center City tunnel is built, within the tunnel in Center City. Rather, this is about trains between New York and points west of Philadelphia, including Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, and the entire Midwest. Whether the bypass makes sense depends on traffic, and so it’s an example of a good investment for later, but only after more of the network is built. This has analogs in Germany as well, with a number of important cities whose train stations are terminals (Frankfurt, Leipzig) or de facto terminals (Cologne, where nearly all traffic goes east, not west).

Philadelphia and Zoo Junction

Philadelphia historically has three mainlines on the Pennsylvania Railroad, going to north to New York, south to Washington, and west to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. The first two together form the southern half of the Northeast Corridor; the third is locally called the Main Line, as it was the PRR’s first line.

Trains can run through from New York to Washington or from Harrisburg to Washington. The triangle junction northwest of the station, Zoo Junction, permits trains from New York to run through to Harrisburg and points west, but they then have to skip Philadelphia. Historically, the fastest PRR trains did this, serving the city at North Philadelphia with a connection to the subway, but this was in the context of overnight trains of many classes. Today’s Keystone trains between New York and Harrisburg do no such thing: they go from New York to Philadelphia, reverse direction, and then go onward to Harrisburg. This is a good practice in the current situation – the Keystones run less than hourly, and skipping Philadelphia would split frequencies between New York and Philadelphia to the point of making the service much less useful.

When should trains skip Philadelphia?

The advantage of skipping Philadelphia are that trains from New York to Harrisburg (and points west) do not have to reverse direction and are therefore faster. On the margin, it’s also beneficial for passengers to face forward the entire trip (as is typical on American and Japanese intercity trains, but not European ones). The disadvantage is that it means trains from Harrisburg can serve New York or Philadelphia but not both, cutting frequency to each East Coast destination. The effect on reliability and capacity is unclear – at very high throughput, having more complex track sharing arrangements reduces reliability, but then having more express trains that do not make the same stop on the same line past New York and Newark does allow trains to be scheduled closer to each other.

The relative sizes of New York, Philadelphia, and Washington are such that traffic from Harrisburg is split fairly evenly between New York on the other hand and Philadelphia and Washington on the other hand. So this really means halving frequency to each of New York and Philadelphia; Washington gets more service with split service, since if trains keep reversing direction, there shouldn’t be direct Washington-Harrisburg trains and instead passengers should transfer at 30th Street.

The impact of frequency is really about the headway relative to the trip time. Half-hourly frequencies are unconscionable for urban rail and very convenient for long-distance intercity rail. The headway should be much less than the one-way trip time, ideally less than half the time: for reference, the average unlinked New York City Subway trip was 13 minutes in 2019, and those 10- and 12-minute off-peak frequencies were a chore – six-minute frequencies are better for this.

The current trip time is around 1:20 New York-Philadelphia and 1:50 Philadelphia-Harrisburg, and there are 14 roundtrips to Harrisburg a day, for slightly worse than hourly service. It takes 10 minutes to reverse direction at 30th Street, plus around five minutes of low-speed running in the station throat. Cutting frequency in half to a train every two hours would effectively add an hour to what is a less than a two-hour trip to Philadelphia, even net of the shorter trip time, making it less viable. It would eat into ridership to New York as well as the headway rose well above half the end-to-end trip, and much more than that for intermediate trips to points such as Trenton and Newark. Thus, the current practice of reversing direction is good and should continue, as is common at German terminals.

What about high-speed rail?

The presence of a high-speed rail network has two opposed effects on the question of Philadelphia. On the one hand, shorter end-to-end trip times make high frequencies even more important, making the case for skipping Philadelphia even weaker. In practice, high speeds also entail speeding up trains through station throats and improving operations to the point that trains can change directions much faster (in Germany it’s about four minutes), which weakens the case for skipping Philadelphia as well if the impact is reduced from 15 minutes to perhaps seven. On the other hand, heavier traffic means that the base frequency becomes much higher, so that cutting it in half is less onerous and the case for skipping Philadelphia strengthens. Already, a handful of express trains in Germany skip Leipzig on their way between Berlin and Munich, and as intercity traffic grows, it is expected that more trains will so split, with an hourly train skipping Leipzig and another serving it.

With high-speed rail, New York-Philadelphia trip times fall to about 45 minutes in the example route I drew for a post from 2020. I have not done such detailed work outside the Northeast Corridor, and am going to assume a uniform average speed of 240 km/h in the Northeast (which is common in France and Spain) and 270 km/h in the flatter Midwest (which is about the fastest in Europe and is common in China). This means trip times out of New York, including the reversal at 30th Street, are approximately as follows:

Philadelphia: 0:45

Harrisburg: 1:30

Pittsburgh: 2:40

Cleveland: 3:15

Toledo: 3:55

Detroit: 4:20

Chicago: 5:20

Out of both New York and Philadelphia, my gravity model predicts that the strongest connection among these cities is by Pittsburgh, then Cleveland, then Chicago, then Detroit, then Harrisburg. So it’s best to balance the frequency around the trip time to Pittsburgh or perhaps Cleveland. In this case, even hourly trains are not too bad, and half-hourly trains are practically show-up-and-go frequency. The model also predicts that if trains only run on the Northeast Corridor and as far as Pittsburgh then traffic fills about two hourly trains; in that case, without the weight of longer trips, the frequency impact of skipping Philadelphia and having one hourly train run to New York and Boston and another to Philadelphia and Washington is likely higher than the benefit of reducing trip times on New York-Harrisburg by about seven minutes.

In contrast, the more of the network is built out, the higher the base frequency is. With the Northeast Corridor, the spine going beyond Pittsburgh to Detroit and Chicago, a line through Upstate New York (carrying Boston-Cleveland traffic), and perhaps a line through the South from Washington to the Piedmont and beyond, traffic rises to fill about six trains per hour per the model. Skipping Philadelphia on New York-Pittsburgh trains cuts frequency from every 10 minutes to every 20 minutes, which is largely imperceptible, and adds direct service from Pittsburgh and the Midwest to Washington.

Building a longer bypass

So far, we’ve discussed using Zoo Junction. But if there’s sufficient traffic that skipping Philadelphia shouldn’t be an onerous imposition, it’s possible to speed up New York-Harrisburg trains further. There’s a freight bypass from Trenton to Paoli, roughly following I-276; a bypass using partly that right-of-way and, where it curves, that of the freeway, would require about 70 km of high-speed rail construction, for maybe $2 billion. This would cut about 15 km from the trip via 30th Street or 10 km via the Zoo Junction bypass, but the tracks in the city are slow even with extensive work. I believe this should cut another seven or eight minutes from the trip time, for a total of 15 minutes relative to stopping in Philadelphia.

I’m not going to model the benefits of this bypass. The model can spit out an answer, which is around $120 million a year in additional revenue from faster trips relative to not skipping Philadelphia, without netting out the impact of frequency, or around $60 million relative to skipping via Zoo, for a 3% financial ROI; the ROI grows if one includes more lines in the network, but by very little (the Cleveland-Cincinnati corridor adds maybe 0.5% ROI). But this figure has a large error bar and I’m not comfortable using a gravity model for second-order decisions like this.

Penn Station Expansion is Based on Fraud

New York is asking for $20 billion for reconstruction ($7 billion) and physical expansion ($13 billion) of Penn Station. The state is treating it as a foregone conclusion that it will happen and it will get other people’s money for it; the state oversight board just voted for it despite the uncertain funding. Facing criticism from technical advocates who have proposed alternatives that can use Penn Station’s existing infrastructure, lead agency Empire State Development (ESD) has pushed back. The document I’ve been looking at lately is not new – it’s a presentation from May 2021 – but the discussion I’ve seen of it is. The bad news is that the presentation makes fraudulent claims about the capabilities of railroads in defense of its intention to waste $20 billion, to the point that people should lose their jobs and until they do federal funding for New York projects should be stingier. The good news is that this means that there are no significant technical barriers to commuter rail modernization in New York – the obstacles cited in the presentation are completely trivial, and thus, if billions of dollars are available for rail capital expansion in New York, they can go to more useful priorities like IBX.

What’s the issue with Penn Station expansion?

Penn Station is a mess at both the concourse and track levels. The worst capacity bottleneck is the western approach across the river, the two-track North River Tunnels, which on the eve of corona ran about 20 overfull commuter trains and four intercity trains into New York at the peak hour; the canceled ARC project and the ongoing Gateway project both intend to address this by adding two more tracks to Penn Station.

Unfortunately, there is a widespread belief that Penn Station’s 21 existing tracks cannot accommodate all traffic from both east (with four existing East River Tunnel tracks) and west if new Hudson tunnels are built. This belief goes back at least to the original ARC plans from 20 years ago: all plans involved some further expansion, including Alt G (onward connection to Grand Central), Alt S (onward connection to Sunnyside via two new East River tunnel tracks), and Alt P (deep cavern under Penn Station with more tracks). Gateway has always assumed the same, calling for a near-surface variation of Alt P: instead of a deep cavern, the block south of Penn Station, so-called Block 780, is to be demolished and dug up for additional tracks.

The impetus for rebuilding Penn Station is a combination of a false belief that it is a capacity bottleneck (it isn’t, only the Hudson tunnels are) and a historical grudge over the demolition of the old Beaux-Arts station with a labyrinthine, low-ceiling structure that nobody likes. The result is that much of the discourse about the need to rebuild the station is looking for technical justification for an aesthetic decision; unfortunately, nobody I have talked to or read in New York seems especially interested in the wayfinding aspects of the poor design of the existing station, which are real and do act as a drag on casual travel.

I highlight the history of Penn Station and the lead agency – ESD rather than the MTA, Port Authority, or Amtrak – because it showcases how this is not really a transit project. It’s not even a bad transit project the way ARC Alt P was or the way Gateway with Block 780 demolition is. It’s an urban renewal project, run by people who judge train stations by which starchitect built them and how they look in renderings rather than by how useful they are for passengers. Expansion in this context is about creating the maximum footprint for renderings, and not about solving a transportation problem.

Why is it believed that Penn Station needs more tracks?

Penn Station tracks are used inefficiently. The ESD pushback even hints at why, it just treats bad practices as immutable. Trains have very long dwell times: per p. 22 of the presentation, the LIRR can get in and out in a quick 6 minutes, but New Jersey Transit averages 12 and Amtrak averages 22. The reasons given for Amtrak’s long dwell are “baggage” (there is no checked baggage on most trains), “commissary” (the cafe car is restocked there, hardly the best use of space), and “boarding from one escalator” (this is unnecessary and in fact seasoned travelers know to go to a different concourse and board there). A more reasonable dwell time at a station as busy as Penn Station on trains designed for fast access and egress is 1-2 minutes, which happens hundreds of times a day at Shin-Osaka; on the worse-designed Amtrak rolling stock, with its narrower doors, 5 minutes should suffice.

New Jersey Transit can likewise deboard fast, although it might need to throw away the bilevels and replace them with longer single-deck trains. This reduces on-board capacity somewhat, but this entire discussion assumes the Gateway tunnel has been built, otherwise even present operations do not exhaust the station’s capacity. Moreover, trains can be procured for comfortable standing; subway riders sometimes have to stand for 20-30 minutes and commuter rail riders should have similar levels of comfort – the problem today is standees on New Jersey Transit trains designed without any comfortable standing space.

But by far the biggest single efficiency improvement that can be done at Penn Station is through-running. If trains don’t have to turn back or even continue to a yard out of service, but instead run onward to suburbs on the other side of Manhattan, then the dwell time can be far less than 6 minutes and then there is much more space at the station than it would ever need. The station’s 21 tracks would be a large surplus; some could be removed to widen the platform, and the ESD presentation does look at one way to do this, which isn’t necessarily the optimal way (it considers paving over every other track to widen the platforms and permit trains to open doors on both sides rather than paving over every other track pair to widen the platforms much more but without the both-side doors). But then the presentation defrauds the public on the opportunity to do so.

Fraudulent claim #1: 8 minute dwells

On p. 44, the presentation compares the capacity with and without through-running, assuming half the tracks are paved over to widen the platforms. The explicit assumption is that through-running commuter rail requires trains to dwell 8 minutes at Penn Station to fully unload and load passengers. There are three options: the people who wrote this may have lied, or they may be incompetent, or they be both liars and incompetent.

In reality, even very busy stations unload and load passengers in 30-60 seconds at rush hour. Limiting cases reaching up to 90-120 seconds exist but are rare; the RER A, which runs bilevels, is the only one I know of at 105.

On pp. 52-53, the presentation even shows a map of the central sections of the RER, with the central stations (Gare du Nord, Les Halles, and Auber/Saint-Lazare) circled. There is no text, but I presume that this is intended to mean that there are two CBD stations on each line rather than just one, which helps distribute the passenger load better; in contrast, New York would only have one Manhattan station on through-trains on the Northeast Corridor, which requires a longer dwell time. I’ve heard this criticism over the years from official and advocate sources, and I’m sympathetic.

What I’m not sympathetic to is the claim that the dwell time required at Penn Station is more than the dwell time required at multiple city center stations, all combined. On the single-deck RER B, the combined rush hour dwell time at Gare du Nord and Les Halles is around 2 minutes normally (and the next station over, Saint-Michel, has 40-60 second rush hour dwells and is not in the CBD unless you’re an academic or a tourist); in unusual circumstances it might go as high as 4 minutes. The RER A’s combined dwell is within the same range. In Munich, there are six stations on the S-Bahn trunk between Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof – but at the intermediate stations (with both-sides door opening) the dwell times are 30 seconds each and sometimes the doors only stay open 20 seconds; Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof have longer dwell times but are not busier, they just are used as control points for scheduling.

The RER A’s ridership in 2011 was 1.14 million trips per weekday (source, p. 22) and traffic was 30 peak trains per hour and 24 reverse-peak trains; at the time, dwell times at Les Halles and Auber were lower than today, and it took several more years of ridership growth for dwell times to rise to 105 seconds, reducing peak traffic to 27 and then 24 tph. The RER B’s ridership was 983,000 per workday in 2019, with 20 tph per direction. Munich is a smaller city, small enough New Yorkers may look down on it, but its single-line S-Bahn had 950,000 trips per workday in 2019, on 30 peak tph in each direction. In contrast, pre-corona weekday ridership was 290,000 on the LIRR, 260,000 on Metro-North, and around 270,000 on New Jersey Transit – and the LIRR has a four-track tunnel into Manhattan, driving up traffic to 37 tph in addition to New Jersey’s 21. It’s absurd that the assumption on dwell time at one station is that it must be twice the combined dwell times at all city center stations on commuter lines that are more than twice as busy per train as the two commuter railroads serving Penn Station.

Using a more reasonable figure of 2 minutes in dwell time per train, the capacity of through-running rises to a multiple of what ESD claims, and through-running is a strong alternative to current plans.

Fraudulent claim #2: no 2.5% grades allowed

On pp. 38-39, the presentation claims that tracks 1-4 of Penn Station, which are currently stub-end tracks, cannot support through-running. In describing present-day operations, it’s correct that through-running must use the tracks 5-16, with access to the southern East River Tunnel pair. But it’s a dangerously false assumption for future infrastructure construction, with implications for the future of Gateway.

The rub is that the ARC alternatives that would have continued past Penn Station – Alts P and G – both were to extend the tunnel east from tracks 1-4, beneath 31st Street (the existing East River Tunnels feed 32nd and 33rd). Early Gateway plans by Amtrak called for an Alt G-style extension to Grand Central, with intercity trains calling at both stations. There was always a question about how such a tunnel would weave between subway tunnels, and those were informally said to doom Alt G. The presentation unambiguously answers this question – but the answer it gives is the exact opposite of what its supporting material says.

The graphic on p. 39 shows that to clear the subway’s Sixth Avenue Line, the trains must descend a 2.45% grade. This accords with what I was told by Foster Nichols, currently a senior WSP consultant but previously the planner who expanded Penn Station’s lower concourse in the 1990s to add platform access points and improve LIRR circulation, thereby shortening LIRR dwell times. Nichols did not give the precise figure of 2.45%, but did say that in the 1900s the station had been built with a proviso for tracks under 31st, but then the subway under Sixth Avenue partly obstructed them, and extension would require using a grade greater than 2%.

The rub is that modern urban and suburban trains climb 4% grades with no difficulty. The subway’s steepest grade, climbing out of the Steinway Tunnel, is 4.5%, and 3-3.5% grades are routine. The tractive effort required can be translated to units of acceleration: up a 4% grade, fighting gravity corresponds to 0.4 m/s^2 acceleration, whereas modern trains do 1-1.3 m/s^2. But it’s actually easier than this – the gradient slopes down when heading out of the station, and this makes the grade desirable: in fact, the subway was built with stations at the top of 2.5-3% grades (for example, see figure 7 here) so that gravity would assist acceleration and deceleration.

The reason the railroaders don’t like grades steeper than 2% is that they like the possibility of using obsolete trains, pulled by electric locomotives with only enough tractive effort to accelerate at about 0.4 m/s^2. With such anemic power, steeper grades may cause the train to stall in the tunnel. The solution is to cease using such outdated technology. Instead, all trains should be self-propelled electric multiple units (EMUs), like the vast majority of LIRR and Metro-North rolling stock and every subway train in the world. Japan no longer uses electric locomotives at all on its day trains, and among the workhorse European S-Bahn systems, all use EMUs exclusively, with the exception of Zurich, which still has some locomotive-pulled trains but is transitioning to EMUs.

It costs money to replace locomotive-hauled trains with EMUs. But it doesn’t cost a lot of money. Gateway won’t be completed tomorrow; any replacement of locomotives with EMUs on the normal replacement cycle saves capital costs rather than increasing them, and the same is true of changing future orders to accommodate peak service expansion for Gateway. Prematurely retiring locomotives does cost money, but New Jersey Transit only has 100 electric locomotives and 29 of them are 20 years old at this point; the total cost of such an early retirement program would be, to first order, about $1 billion. $1 billion is money, but it has independent transportation benefits including faster acceleration and higher reliability, whereas the $13 billion for Penn Station expansion have no transportation benefits whatsoever. Switzerland may be a laggard in replacing the S-Bahn’s locomotives with EMUs, but it’s a leader in the planning maxim electronics before concrete, and when the choice is between building a through-running tunnel for EMUs and building a massive underground station to store electric locomotives, the correct choice is to go with the EMUs.

How do they get away with this?

ESD is defrauding the public. The people who signed their names to the presentation should most likely not work for the state or any of its contractors; the state needs honest, competent people with experience building effective mass transit projects.

Those people walk around with their senior manager titles and decades of experience building infrastructure at outrageous cost and think they are experts. And why wouldn’t they? They do not respect any knowledge generated outside the New York (occasionally rest-of-US) bubble. They think of Spain as a place to vacation, not as a place that built 150 kilometers of subway 20 years ago for the same approximate cost as Second Avenue Subway phases 1 and 2. They think of smaller cities like Milan as beneath their dignity to learn about.

And what’s more, they’ve internalized a culture of revealing as little as possible. That closed attitude has always been there; it’s by accident that they committed two glaring acts of fraud to paper with this presentation. Usually they speak in generalities: the number of people who use the expression “apples-to-apples” and provide no further detail is staggering. They’ve learned to be opaque – to say little and do little. Most likely, they’re under political pressure to make the Penn Station reconstruction and expansion look good in order to generate what the governor thinks are good headlines, and they’ve internalized the idea that they should make up numbers to justify a political project (and in both the Transit Costs Project and previous reporting I’d talked to people in consulting who said they were under such formal or informal pressure for other US projects).

The way forward

With too much political support for wasting $20 billion at the state level, the federal government should step in and put an end to this. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) has $66 billion for mainline rail; none of this money should go to Penn Station expansion, and the only way any money should go to renovation is if it’s part of a program for concrete improvement in passenger rail function. If New York wishes to completely remodel the platform level, and not just pave over every other track or every other track pair, then federal support should be forthcoming, albeit not for $7 billion or even half that. But it’s not a federal infrastructure priority to restore some kind of social memory of the old Penn Station. Form follows function; beautiful, airy train stations that people like to travel through have been built under this maxim, for example Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

To support good rail construction, it’s obligatory that experts be put in charge – and there aren’t any among the usual suspects in New York (or elsewhere in the US). Americans respect Germany more than they do Spain but still less than they should either; unless they have worked in Europe for years, their experience at Berlin Hbf and other modern stations is purely as tourists. The most celebrated New York public transportation appointment in recent memory, Andy Byford, is an expert (on operations) hired from abroad; as I implored the state last year, it should hire people like him to head major efforts like this and back them up when they suggest counterintuitive things.

Mainline rail is especially backward in New York – in contrast, the subway planners that I’ve had the fortune to interact with over the years are insightful and aware of good practices. Managers don’t need much political pressure to say absurd things about gradients and dwell times, in effect saying things are impossible that happen thousands of times a day on this side of the Pond. The political pressure turns people who like pure status quo into people who like pure status quo but with $20 billion in extra funding for a shinier train hall. But both the political appointees and the obstructive senior managers need to go, and managers below them need to understand that do-nothing behavior doesn’t get them rewarded and (as they accumulate seniority) promoted but replaced. And this needs to start with a federal line in the sand: BIL money goes to useful improvements to speed, reliability, capacity, convenience, and clarity – but not to a $20 billion Penn Station reconstruction and expansion that do nothing to address any of these concerns.

No New Washington Union Station, Please

A new presentation dropped for Amtrak’s plans to rebuild Union Station. It is mostly pictorial, but even the pictures suggest that this is a very low-value project, one with little to no transportation value and limited development value. The price tag is now $10 billion (it was $7 billion 10 years ago; the increase is somewhat more than cumulative inflation), but even if two zeros are cut from the budget it’s not necessarily worth it.

What are the features of good train stations?

A train station is interface between passengers and trains. Everything about their construction must serve this purpose. This includes the following features:

- Platforms that can effectively connect to the trains (Union Station has a mix of high and low platforms; all platforms used by Northeast Corridor trains must be raised).

- Minimum distance from platform to street or to urban transit.

- Some concessions and seats for travelers, all in an open area.

- Ticketing machines.

- An information booth with maps of the area and station facilities.

- Nothing more.

In particular, lavish waiting halls not only waste of money but also often have negative transport value, as they either force passenger to walk longer between street and platform or steer them to take an option that involves a longer walk; the new Moynihan Train Hall in New York is an example of the latter failure. Berlin Hauptbahnhof, a rare example of a major urban station built recently in a rich country, has extensive shopping, but it’s all designed around fast street-platform and S-Bahn-intercity connections.

What are the features of Washington Union Station expansion?

The presentation highlights the following features:

- A new concourse beneath the platforms.

- A new concourse on H Street with a prominent headhouse, with bus and streetcar connections.

- An enclosed bus facility.

- Underground parking.

- Future air rights development.

All of the above are wasteful. Connections to H Street can be handled through direct egress points from the platforms to the street, and passengers can get between H Street and the main historic station via those egress points and the platforms themselves. The platforms are key circulation spaces at a train station and using them for passenger movements is normal; I can see an argument against that if the platforms are unusually narrow or crowded, as is the case in New York, but in Washington there is no such excuse.

Nor is Union Station a major node for city buses. Washington’s surface transit network serves the station, but it’s not a major bus node – only a handful of buses terminate there and they don’t run frequently – and even if it were, a surface bus loop akin to what Ostbahnhof has in Berlin would have sufficed. Thus, the bus infrastructure should be descoped, and buses should keep using the streets.

So, none of the transit connections have any value. Parking, moreover, has negative value, as it encourages access to the area by car, displacing transit trips. Union Station already has a Metro connection as well as some surface transit. Better rail operations would also improve commuter rail access for intercity rail riders. Unfortunately, the plan does not improve those operations, nor is there any plan for much needed capital investment to go alongside better mainline rail operations, such as Virginia electrification and high platforms.

What about the air rights?

They are a poor use of money. Building towers on top of active railyards is more difficult and more expensive than building them on firma. Hudson Yards projects in New York came in at around $12,000 per square meter in hard costs, twice the cost of Manhattan skyscrapers on firma except those associated with the World Trade Center, which were unusually costly.

Nor is the location just north of the historic Union Station so desirable that developers would voluntarily pay the railyard premium to be there. The commercial center of Washington is well to the west of the site, comprising Metro Center and Farragut. More office towers around Union Station would be nice for rebalancing and for generating demand for future mainline rail improvements, but the place for them is on firma around the existing station and not on top of the approach tracks.

What should be done?

The plan should be rejected in its entirety and no further funding should be committed to it. Good transit activists should demand that spending on public transportation and intercity rail go to those purposes and not toward building unnecessary train halls. Moreover, it is unlikely the managers at Amtrak who pushed for it and who still are the client for the project understand modern rail operations, nor is it likely that they will ever learn. With neither need nor use for the project, it should be canceled and the people involved in its management and supervision laid off.

The Northeastern United States Wants to Set Tens of Billions on Fire Again

The prospect of federal funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill is getting every agency salivating with desires for outside money for both useful and useless priorities. Northeastern mainline rail, unfortunately, tilts heavily toward the useless, per a deep dive into documents by New York-area activists, for example here and here.

Amtrak is already hiring project management for Penn Station redevelopment. This is a project with no transportation value whatsoever: this is not the Gateway tunnels, which stand to double capacity across the Hudson, but rather a rebuild of Penn Station to add more tracks, which are not necessary. Amtrak’s current claim is that the cost just for renovating the existing station is $6.5 billion and that of adding tracks is $10.5 billion; the latter project has ballooned from seven tracks to 9-12 tracks, to be built on two levels.

This is complete overkill. New train stations in big cities are uncommon, but they do exist, and where tracks are tunneled, the standard is two platform tracks per approach tracks. This is how Berlin Hauptbahnhof’s deep section goes: the North-South Main Line is four tracks, and the station has eight, on four platforms. Stuttgart 21 is planned in the same way. In the best case, each of the approach track splits into two tracks and the two tracks serve the same platform. Penn Station has 21 tracks and, with the maximal post-Gateway scenario, six approach tracks on each side; therefore, extra tracks are not needed. What’s more, bundling 12 platform tracks into a project that adds just two approach tracks is pointless.

This is a combined $17 billion that Amtrak wants to spend with no benefit whatsoever; this budget by itself could build high-speed rail from Boston to Washington.

Or at least it could if any of the railroads on the Northeast Corridor were both interested and expert in high-speed rail construction. Connecticut is planning on $8-10 billion just to do track repairs aiming at cutting 25-30 minutes from the New York-New Haven trip times; as I wrote last year when these plans were first released, the reconstruction required to cut around 40 minutes and also upgrade the branches is similar in scope to ongoing renovations of Germany’s oldest and longest high-speed line, which cost 640M€ as a once in a generation project.

In addition to spending about an order of magnitude too much on a smaller project, Connecticut also thinks the New Haven Line needs a dedicated freight track. The extent of freight traffic on the line is unclear, since the consultant report‘s stated numbers are self-contradictory and look like a typo, but it looks like there are 11 trains on the line every day. With some constraints, this traffic fits in the evening off-peak without the need for nighttime operations. With no constraints, it fits on a single track at night, and because the corridor has four tracks, it’s possible to isolate one local track for freight while maintenance is done (with a track renewal machine, which US passenger railroads do not use) on the two tracks not adjacent to it. The cost of the extra freight track and the other order-of-magnitude-too-costly state of good repair elements, including about 100% extra for procurement extras (force account, contingency, etc.), is $300 million for 5.4 km.

I would counsel the federal government not to fund any of this. The costs are too high, the benefits are at best minimal and at worst worse than nothing, and the agencies in question have shown time and time again that they are incurious of best practices. There is no path forward with those agencies and their leadership staying in place; removal of senior management at the state DOTs, agencies, and Amtrak and their replacement with people with experience of executing successful mainline rail projects is necessary. Those people, moreover, are mid-level European and Asian engineers working as civil servants, and not consultants or political appointees. The role of the top political layer is to insulate those engineers from pressure by anti-modern interest groups such as petty local politicians and traditional railroaders who for whatever reasons could not just be removed.

If federal agencies are interested in building something useful with the tens of billions of BIL money, they should instead demand the same results seen in countries where the main language is not English, and staff up permanent civil service run by people with experience in those countries. Following best industry practices, $17 billion is enough to renovate the parts of the Northeast Corridor that require renovation and bypass those that require greenfield bypasses; even without Gateway, Amtrak can squeeze a 16-car train every 15 minutes, providing 4,400 seats into Penn Station in an hour, compared with around 1,700 today – and Gateway itself is doable for low single-digit billions given better planning and engineering.

How to Spend Money on Public Transport Better

After four posts about the poor state of political transit advocacy in the United States, here’s how I think it’s possible to do better. Compare what I’m proposing to posts about the Green Line Extension in metro Boston, free public transport proposals, federal aid to operations, and a bad Green New Deal proposal by Yonah Freemark.

If you’re thinking how to spend outside (for example, federal) money on local public transportation, the first thing on your mind should be how to spend for the long term. Capital spending that reduces long-term operating costs is one way to do it. Funding ongoing operating deficits is not, because it leads to local waste. Here are what I think some good guidelines to do it right are.

Working without consensus

Any large cash infusion now should work with the assumption that it’s a political megaproject and a one-time thing; it may be followed by other one-time projects, but these should not be assumed. High-speed rail in France, for example, is not funded out of a permanent slush fund: every line has to be separately evaluated, and the state usually says yes because these projects are popular and have good ROI, but the ultimate yes-no decision is given to elected politicians.

It leads to a dynamic in which it’s useful to invest in the ability to carry large projects on a permanent basis, but not pre-commit to them. So every agency should have access to public expertise, with permanent hires for engineers and designers who can if there’s local, state, or federal money build something. This public expertise can be in-house if it’s a large agency; smaller ones should be able to tap into the large ones as consultants. In France, RATP has 2,000 in-house engineers, and it and SNCF have the ability to build large public transport projects on their own, while other agencies serving provincial cities use RATP as a consultant.

It’s especially important to retain such planning capacity within the federal government. A national intercity rail plan should not require the use of outside consultants, and the federal government should have the ability to act as consultant to small cities. This entails a large permanent civil service, chosen on the basis of expertise (and the early permanent hires are likely to have foreign rather than domestic experience) and not politics, and yet the cost of such a planning department is around 2 orders of magnitude less than current subsidies to transit operations in the United States. Work smart, not hard.

However, investing in the ability to build does not mean pre-committing to build with a permanent fund. Nor does it mean a commitment to subsidizing consumption (such as ongoing operating costs) rather than investment.

Funding production, not consumption

It is inappropriate to use external infusions of cash for operations and, even worse, maintenance. When maintenance is funded externally, local agencies react by deferring maintenance and then crying poverty whenever money becomes available. Amtrak fired David Gunn when the Bush administration pressured it to defer maintenance in order to look profitable for privatization and replaced him with the more pliable Joe Boardman, and then when the Obama stimulus came around Boardman demanded billions of dollars for state of good repair that should have built a high-speed rail program instead.

This is why American activists propose permanent programs – but those get wasted fast, due to surplus extraction. A better path forward is to be clear about what will and will not be funded, and putting state of good repair programs in the not-funded basket; the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework’s negotiations were right to defund the public transit SOGR bucket while keeping the expansion bucket.

Moreover, all funding should be tied to using the money prudently – hence the production, not consumption part. This can be capital funding, with the following priorities, in no particular order:

- Capital funding that reduces long-term operating costs, for example railway electrification and the installation of overhead wires (“in-motion charging“) on bus trunks.