Category: Incompetence

American Myths of European Poverty

I occasionally have exchanges on social media or even in comments here that remind me that too many people in the American middle class believe that Europe is much poorer than the US. The GDP gap between the US and Northern Europe is small and almost entirely reducible to hours worked, but the higher inequality in the US means that the top 10-20% of the US compare themselves with their peers here and conclude that Europe is poor. Usually, it’s just social media shitposting, for example about how store managers in the US earn the same as doctors in Europe. But it becomes relevant to public transit infrastructure construction in two ways. First, Americans in positions of authority are convinced that American wages are far higher than European ones and that’s why American construction costs are higher than European ones. And second, more broadly, the fact that people in positions of authority really do earn much more in the US than here inhibits learning.

The income gap

The United States is, by a slight amount, richer than Northern Europe, which for the purposes of this post comprises the German-speaking world, the Nordic countries, and Benelux. Among the three largest countries in this area, Germany is 16.5% poorer than the US, the Netherlands 8.3% poorer, Sweden 14.3%. This is more than anything an artifact of shorter working hours – Sweden has an ever so slightly larger GDP per hour worked, the other two are 6-7% poorer per hour worked. All three countries have a much higher 15-64 labor force participation rate than the US, but they’re also older, which in the case of Germany actually gets its 15+ rate to be a hair less than the US’s. But there’s much more part-time work here, especially among women, who face large motherhood penalties in German society (see figures 5-7 in Herzberg-Druker, and Kleven et al). Germany is currently in full employment, so it’s not about hidden part-time work; it’s a combination of German-specific sexism and Europe-wide norms in which workers get around six weeks of paid vacation per year.

One implication of the small gap in income per hour is that wages for the same job are likely to be similar, if the jobs pay close to the mean wage. This is the case for tunnel miners, who are called sandhogs in the United States: the project labor agreements in New York are open – the only case in which itemized costs are publicly available – and showcase fully-laden employment costs that, as we document in our construction costs reports, work out to around $185,000/year in 2010 prices; there is a lot of overstaffing in New York and it’s disproportionately in the lower-earning positions, and stripping those, it’s $202,000/year. I was told that miners in Stockholm earn 70,000 kronor/month, or about $100,000/year in PPP terms (as of 2020-1), and the fully-laden cost is about twice that; a union report from the 2000s reports lower wages, but only to about the same extent one would expect from Sweden’s overall rate of economic growth between then and 2021. The difference at this point is second-order, lower than my uncertainty coming from the “about” element out of Sweden.

While we’re at it, it’s also the case for teachers: the OECD’s Education at a Glance report‘s indicator D3 covers teacher salaries by OECD country, and most Northern European countries pay teachers better than the US in PPP terms, much better in the case of Germany. Teacher wage scales are available in New York and Germany; the PPP rate is at this point around 1€ = $1.45, which puts starting teachers in New York with a master’s about on a par with their counterparts in the lowest-paying German state (Rhineland-Pfalz). New York is a wealthy city, with per capita income somewhat higher than in the richest German state (Bavaria), but it’s not really seen in teacher pay. I don’t know the comparative benefit rates, but whenever we interview people about European wage rates for construction, we’re repeatedly told that benefits roughly double the overall cost of employment, which is also what we see in the American public sector.

The issue of inequality

American inequality is far higher than European inequality. So high is the gap that, on LIS numbers, nearly all Western European countries today have lower disposable income inequality than the lowest recorded level for the US, 0.31 in 1980. Germany’s latest number is 0.302 as of 2021, and Dutch and Nordic levels are lower, as low as 0.26-0.27; the US is at 0.391 as of 2022. If distributions are log-normal (they only kind of are), then from a normal distribution log table lookup, this looks like the mean-to-median income ratios should be, respectively, 1.16 for Germany and 1.297 for the US.

However, top management is not at the median, and that’s the problem for comparisons like this. The average teacher or miner makes a comparable amount of money in the US and Northern Europe. The average private consultant deciding on how many teachers or miners to hire makes more money in the US. A 90th-percentile earner is somewhat wealthier in the US than here, again on LIS number; the average top-1%er is, in relative terms, 50% richer in the US than in Germany (and in absolute terms 80% richer) and nearly three times as rich in the US as in Sweden or the Netherlands, on Our World in Numbers data.

On top of that, I strongly suspect that not all 90th percentile earners are created equal, and in particular, the sort of industries that employ the mass (upper) middle class in each country are atypically productive there and therefore pay better than their counterparts abroad. So the average 90th-percentile American is noticeably but not abnormally better off than the average 90th-percentile German or Swede, but is much better off than the average German or Swede who works in the same industries as the average 90th-percentile American. Here we barely have a tech industry by American standards, for example; we have comparable biotech to the US, but that’s not usually where the Americans who noisily assert that Europe is poor work in.

Looking for things to mock

While the US is not really richer than Northern Europe, the US’s rich are much richer than Northern Europe’s. But then the statistics don’t bear out a massive difference in averages – the GDP gap is small, the GDP gap per hour worked is especially small and sometimes goes the other way, the indicators of social development rarely favor the US, immigration into Western Europe has been comparable to immigration to the US for some time now (here’s net migration, and note that this measure undercounts the 2022 Ukrainians in Germany and overcounts them in Poland).

So middle-class Americans respond by looking for creative measures that show the level of US-Europe income gap that they as 90th-percentile earners in specific industries experience (or more), often dropping the PPP adjustment, or looking at extremely specific things that are common in the US but not here. I’ve routinely seen American pundits who should know better complain that European washing machines and driers are slow; I’m writing this post during a 4.5-hour wash-and-dry cycle. Because they fixate on proving the superiority of the United States to the only part of the world that’s rich enough not to look up to it, they never look at other measures that might show the opposite; this apartment is right next to an elevated train, but between the lower noise levels of the S-Bahn, good insulation, and thick tilt-and-turn windows, I need to concentrate to even hear the train, and am never disturbed by it, whereas American homes have poor sound insulation to the point that street noise disturbs the sleep.

Learning to build infrastructure

The topline conclusion of any American infrastructure reform should be “the United States should look more like Continental Europe, Turkey, non-Anglophone East Asia, and the better-off parts of Latin America.”

If it’s written in the language of specific engineering standards, this is at times acceptable, if the standards are justified wholly internally (“we can in fact do this, here’s a drawing”). Even then, people who associate Americanness with their own career success keep thinking safety, accessibility, and similar issues are worse here, and ask “what about fire code?” and then are floored to learn that fire safety here is actually better, as Stephen Smith of Market Urbanism and the Center for Building constantly points out.

But then anything that’s about management is resisted. It’s difficult to convince an American who’s earning more than $100,000 a year in their 20s and thinks it’s not even that much money because their boss is richer that infrastructure project management is better in countries where the CEO earns as much money as they do as an American junket assistant. Such people readily learn from rich, high-inequality places that like splurging, which are not generally the most productive ones when it comes to infrastructure. Even Americans who think a lot about state capacity struggle with the idea that Singapore has almost as high construction costs as the US; in Singapore, the CEO earns an American salary, so the country must be efficient, right? Well, the MRT is approaching $1 billion/km in construction costs for the Cross-Island Line, and Germany builds 3 km of subway (or decides not to build them) on the same budget and Spain builds 6 km, but Europe is supposedly poor and Americans can’t learn from that.

The upshot is that even as we’re seeing some movement on better engineering and design standards in the United States, resulting in significant cost savings, there’s no movement for better overall management. Consultant-driven projects remain the norm, and even proposals for improving state capacity are too driven by domestic analysis without any attempt at international learning or comparativism. Nor is there any effort at better labor efficiency – management in the US hates labor, but also thinks it’s entirely about overpaid workers or union safety rules, and doesn’t stoop to learn how to build more productively.

Quick Note: What the Hell is Going on in San Jose?

The BART to San Jose extension always had problems, but somehow things are getting worse. A month and a half ago, it was revealed that the projected cost of the 9.6-kilometer line had risen to $12.2 billion. Every problem that we seemed to identify in our reports about construction costs in New York and Boston appears here as far as I can tell, with the exception of labor, which at least a few years ago showed overstaffing in the Northeastern United States but not elsewhere. In particular, the station and tunnel design maximizes costs – the first link cites Adam Buchbinder on the excessive size of the digs. Unfortunately, the response by the Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) to a question just now about the station shows that not only are the stations insanely expensive, but also not even convenient for passengers (Twitter link, Nitter link).

Cost breakdown

The March 2024 agenda (link, PDF-pp. 488-489) breaks down the costs. The hard costs total $7 billion; the systems : civils ratio is 1:3.5, which is not bad. But the overall hard costs are still extreme. Then on top of them there are soft costs totaling $2.78 billion, or 40% on top of the hard costs. The same percentage for Second Avenue Subway was 21%, and the norm for third-party consultants for the Continental European projects for which we have data (in Italy, Spain, Turkey, and France) is to charge 5-10%. Soft costs should not be this high; if they are, something is deeply wrong with how the agency uses consultants.

Large-diameter tunnel boring machines

The BART to San Jose project has long had two distinct options for tunnels and station: twin bores, and single bore. The twin bore option is conventional construction of two bored tunnels, one for each track, and then stations to be built as dedicated civil construction projects outside the tunnel; this is how most subways are built today. The single bore option is a large-diameter tunnel boring machine (TBM), with the bore large enough to have not just two tracks side by side, but also platforms within the bore, eliminating the need for mined station caverns or for extensive cut-and-cover station digs. Both options cleared environmental reviews; VTA selected the single bore option, which has been controversial.

I’ve written positively about large-diameter TBMs before, and I don’t think I’ve written a full post walking this back. I’ve written about how large-diameter TBMs are inappropriate for San Jose, but the truth is that the method is not treated as a success elsewhere in urban rail, either. This is controversial, and serious engineers still think it works and point to successes in intercity rail, but in urban rail, the problems with building settlement are too serious. The main example of a large-diameter TBM is Barcelona L9/10, which uses the method to avoid having to open up streets under multiple older metro tunnels in Barcelona; it also has high construction costs by Spanish standards (and low costs by non-Spanish ones). In Italy, whose construction costs are also fairly low if not as low as in Madrid, engineers considered using large-diameter TBMs for the sensitive parts of Rome Metro Line C but then rejected that solution as too risky, going for conventional high-cost mined stations instead.

Regardless of the wisdom of doing this in Southern Europe, in San Jose it is stupid. There are wide streets to dig up for cut-and-cover stations. Then, the implementation is bad – the station entryways are too big, whereas Barcelona’s are small elevator banks, and the tunnel bore is wide enough for a platform and two tracks on the same level whereas Barcelona has a narrower bore with stacked platforms.

Thankfully, it is administratively possible to cancel the single bore option, since the twin bore option cleared the environmental reviews as well, and in 2007 was already complete to 65% design (link, PDF-p. 7). Unfortunately, there isn’t much appetite among officials for it. Journalists and advocates are more interested, but the agency seems to stick to its current plans even as their costs are setting non-New York construction cost records.

Is it at least good?

No. Somehow, for this cost, using a method whose primary advantage is that it makes it possible to build a station anywhere at the cost of massively more expensive tunneling, the station at the city’s main train station, named after still-alive Rod Diridon, will not be easily accessible from mainline rail. The walking distance is 400 meters, which has been justified on the grounds that “The decision had to do with impacts and entitlements. It’s also beneficial for the future intermodal station.”

It is, to be clear, not at all beneficial for a future intermodal BART-Caltrain station to require such a long walking distance, provided we take “beneficial” to mean “beneficial for passengers.” It may be beneficial for a Hollywood action sequence to depict characters running through such a space. It is not beneficial for the ordinary users of the station who might be interested in connecting between the two systems. There are 300 meter walks at some transfers in New York, and passengers do whatever they can to avoid them; I’ve taken three-seat rides with shorter transfers to avoid a two-seat ride with a long block transfer, and my behavior is typical of the subway users I know. Transfer corridors of such length are common in Shanghai and are disliked by the system’s users. It’s not the end of the world, but for $1.3 billion/km, I expect better and so should the people who have to pay for this project.

On Worshiping Foreign Systems

Tucker Carlson has been wowed by Putin’s Russia as of late and is reporting about how great it is; I wouldn’t normally talk about it, except that among the things he crowed about was Kiyevskaya Station on the Moscow Metro. He described it as clean and drug-free, and showed videos that would not have looked out of place in present-day Paris or London, and all I could think about when I watched it was something that I read in Korean media, more than 11 years ago. The newspaper JoongAng criticized the construction of the infill station at Guryong, by comparing its extravagance with the much more spartan stations of the Washington Metro, without noticing how the Washington Metro’s above-ground infill stations cost substantially more than the underground infill at Guryong, the Potomac Yards station reaching four times the cost of Guryong. In both cases, and in some others, the foreign system is not really described as a real place, but as a tourist fantasy. Little learning can come from this.

In fact, there are many positive things one can learn from Russia about how to run rail transportation. Soviet metro planning was quite good, and Eastern Bloc successor states (including satellites, not just former USSR constituents) inherited it and have in some cases expanded on it even while rejecting central planning elsewhere, for example in thoroughly neoliberal Czechia. Good features of this planning tradition include all of the following:

- Clean radial metro network design, with a distinction between city center and outlying areas.

- Very high frequency on each line. Moscow peaks at 39 trains per hour, the highest number I know of on non-driverless metros. When I visited Prague, planned by the same tradition, I saw higher metro frequency than I do in Berlin, with its rigid five-minute headways.

- Central planning of routes, with integration with where housing construction is permitted.

Of note, Carlson’s video doesn’t touch on any of this. He gets the history of the station wrong – he says it was built 70 years ago, when in fact the metro station opened in 1937, and it’s only the two later lines on this three-line transfer that opened in 1953 and 1954. He says he is “just asking questions” and then takes the watcher on a short video trip of the long escalator down to the platform, the ornate details of and art on the station, and the platforms and trains. That’s not Soviet metro design; that’s just metros. The New York City Subway is atypically dirty so that the mosaic art and sculptures there are surrounded by grime, but London and Paris are clean, and some of the stations in Paris have interesting art on the platforms. Stockholm has exposed gneiss rock, which forms a natural arch, and sculptures on some of its platforms. To me, as a regular urban rail rider, all of this looks extremely ordinary, which should not surprise, as good metro planning makes the ordinary last for generations.

Much of it is the excitement of a tourist. To the American visitor, the ornate finishes of Kiyevskaya are new, but the sculptures on the New York City Subway are so familiar that they go unremarkable. I see this in how Americans speak of Europe in general, especially on matters of urbanism; Marco Chitti pointed out that Italian farmers’ markets are for tourists and politicians, while most Italians do their shopping at car-oriented hypermarkets – tourists don’t see how auto-oriented Italy is, and this influences urbanist thinking about the greatness of traditional premodern city centers.

I don’t know what Carlson thinks about urbanism in general. I doubt he’s thought about it much. There are other American right-wing populists who have; their views are common enough among architectural traditionalists that The American Conservative publishes Strong Towns and that at one point the Trump administration passed an executive order requiring all new federal buildings to use traditional architectural styles rather than postwar ones like brutalism or postmodernism.

And Soviet-style metro planning is the exact opposite of that kind of urbanist tradition. It lives off of high-density housing, which are called projects in American parlance and microdistricts in the Soviet tradition, and are ideally placed right next to metro stations so that people can get to work efficiently. In Moscow, the city is large enough to support many radial metro lines, so that districts can be fairly close to metro stations far out of the center; in smaller cities, central planning is required to ensure alternation between high-density housing near the trains and parkland far from them, for which the best examples are Nordic rather than Eastern Bloc.

Traditional architecture critics loathe that kind of housing. In Sweden, one can find right-wingers who view Million Program housing as a socialist conspiracy to depress people into being pliable subjects. Chuck Marohn is not conspiratorial like this, but still opposes spiky density and prefers uniform density, with rules about how new housing on a street should be of similar size to existing buildings (no more than 50% taller) rather than much taller as is typical of either modern redevelopment projects or project-style housing.

Carlson himself is not that influential in urbanism, in the grand scheme of things. But urbanists who go on tourist trips abroad and conflate their travelogues for intellectual insights abound. Their views are often idiosyncratic, based on whatever they liked on a trip, which could be a high-speed rail trip, a neighborhood in a tourist trap, a kind of shopping that locals rarely do, or something similar. In all cases, this is fundamentally about leisure: the (usually New Left) tourist is in the city for purposes of leisure and experiences it as such, but the local rarely is. A glimpse of this can even be seen in the video from Kiyevskaya: the Moscow Metro is very crowded at rush hour, but the video does not depict overcrowding.

It’s possible to learn from abroad, but it does not involve travelogues. It involves interacting with locals in a position of equality rather than in that of a heavyweight who uses taxi drivers as sources. It involves reading what locals say; two years ago, around when Russia invaded Ukraine, I found a list of Russian dissidents and looked at the LiveJournal of an urbanist activist, who was talking about how Russian cities undermaintain public spaces. I think highly of Seung Y. Lee precisely because he demystifies Korean and Japanese urban rail for the Western reader; one can read his complaints about the Seoul subway’s accessibility and still recognize that its 92% wheelchair accessibility is by most global standards very good. It’s possible to, from a position of learning, inform oneself and conclude that a foreign system is superior in most aspects to the domestic one. But that’s not what so many urbanists who speak of their own tourists experience do, and Carlson happens to have provided one political example of this.

Worthless Canadian Initiative

Canada just announced a few days ago that it is capping the number of international student visas; the Times Higher Education and BBC both point out that the main argument used in favor of the cap is that there’s a housing shortage in Canada. Indeed, the way immigration politics plays out in Canada is such that the cap is hard to justify by other means: traditionally, the system there prioritized high-skill workers, to the point that there has been conservative criticism of the Trudeau cabinet for greatly expanding low-skill (namely, refugee) migration; capping student visas is not how one responds to such criticism.

The issue is that Canada builds a fair amount of housing, but not enough for population growth; the solution is to build more – in a fast-growing country like Canada, the finance sector expects housing demand to grow and therefore will readily build more if it is allowed to.

Vancouver deserves credit for the quality of its transit-oriented development and to a large extent also for the amount of absolute development it permits (about 10 units per 1,000 residents annually); but its ability to build is much greater than that, precisely because rapid immigration means that more housing is profitable, even at higher interest rates. The population growth coming from immigration sends a signal to the market, invest in long-term tangible goods like housing. Thus, Vancouver deserves less credit for its permissiveness of development – large swaths of the city are zoned for single-family housing with granny flats allowed, including in-demand West Side neighborhoods with good access to UBC and Downtown jobs by current buses and future SkyTrain.

The rub is that restricting student immigration is probably the worst possible way to deal with a housing shortage. Students live at high levels of crowding, and the marginal students, who the visa cap is excluding, live at higher levels of crowding than the rest because they tend to be at poorer universities and from poorer backgrounds. The reduction in present-day demand is limited. In Vancouver, an empty nester couple with 250 square meters of single-family housing in Shaughnessy is consuming far more housing, and sitting on far more land that could be redeveloped at high density, than four immigrants sharing a two-bedroom apartment in East Vancouver.

In contrast, the reduction in future demand is substantial, because those students then graduate and get work, and many of them get high-skill, high-wage jobs (the Canadian university graduate premium is declining but still large; the American one is larger, but the US is also a higher-inequality society in general); having fewer students, even fewer marginal students who might take jobs below their skill level, is still a reduction in both future population and future productivity. What this means is that capital owners deciding where to allocate assets are less likely to be financing construction.

The limiting factor on housing production is to a large extent NIMBYism, and there, in theory, immigration restrictions are neutral. (In practice, they can come out of a sense of national greatness developmental conservatism that wants to build a lot but restrict who can come in, or out of anti-developmental NIMBYism that feels empowered to build less as fewer people are coming; this situation is the latter.) However, it’s not entirely NIMBYism – private developmental still has to be profitable, and judging by the discourse I’m seeing on Canadian high-rise housing construction costs in Toronto and Vancouver, it’s not entirely a matter of permits. Even in an environment with extensive NIMBYism like the single-family areas of Vancouver and Toronto, costs and future profits matter.

Eurostar Security Theater and French Station Size

Jon Worth has been doing a lot of good work lately pouring cold water on various press releases of new rail service in Europe. Yesterday he wrote a long post, reacting to some German rail discourse about the possibility of Eurostar service between London and Germany; he explained the difficulties of connecting Eurostar to new cities, discussing track and station capacity, signaling, and rolling stock.

Jon, whose background is in EU politics, wastes no time in identifying the ultimate problem: the UK demands passport controls, and this demand is unlikely to be waived in the near future due to concerns over Brexit and the need to have visible border control theater. In turn, the passport control and the accompanying security theater (not strictly required, but the UK insists for Channel Tunnel security) mean that boarding trains is a slow process since platforms must be kept sterile; thus, a Eurostar station requires dedicated platforms, and if it has significant rail traffic then it requires many of them, with low throughput per track. This particularly impacts the prospects of Eurostar service to Germany, because it would go via Belgium and Cologne, which has far from enough platforms for this operation.

What I’d like to add to this analysis is that Eurostar made a choice to engage in such controlled operations in the 1990s. The politics of Brexit can explain why there’s no reform that is acceptable to the British political system now; it cannot explain why this was chosen in the 1990s. The norm in Europe before Schengen was that border control officers would perform on-board checks while the train traveled between the last station in the origin country and the first station in the destination country; long nonstop trains between Paris and London or even Lille and London are ideal for such a system. Britain insists on the current system of border control before boarding because this way it can deny entry to people who otherwise would enjoy non-refoulement protections – but in the 2000s the politics in Britain was not significantly more anti-immigration than in, for example, Germany, or France.

Rather, the issue is that Britain insisted on some nebulous notion of separateness, and this interacted poorly with train station design in France compared with in Germany. Parisian train stations are huge, and have a large number of terminating tracks. Dedicating a few terminal tracks to sterile operations is possible at Gare du Nord, and would be possible at other Parisian terminals like Gare de Lyon if they pointed in the direction of a place that demanded them. SNCF has conceived of its operations, especially internationally, as airline-like, and this contributed to complacency about how the train stations are being treated like airports.

Germany developed different (and better) ways of conceiving of train operations. More to the point, Germany doesn’t really have Paris’s terminals with their surplus of tracks, except for Frankfurt and Munich. Cologne, the easiest place to get to London from, doesn’t have enough tracks for sterile operations. This is fine, because German domestic trains do not imitate airlines, even where there is room (instead, the surplus of tracks is used for timed connections between regional trains); this also cascades to international trains connecting to Germany, whether from countries that have more punctual rail networks like Switzerland or from countries that work by a completely different paradigm like Belgium or France.

And now Eurostar politically froze a system that was only workable at low throughput, at a handful of stations with more room for sterile operations than is typical. The system is still below its ridership projections from before opening; it was supposed to be part of a broader international rail network, but that never materialized, because of the burden of security theater, the high fares, and the indifference of Belgium to extending high-speed rail so that it would be useful for international travelers (the average speeds between Brussels-Midi and the German border are within the upper end of the range for upgraded classical lines, even though HSL 2 and 3 are new high-speed lines).

And now, with the knowledge of the 2010s, it’s clear that any future expansion of Eurostar requires forgoing the airline-like paradigm that led SNCF to stagnation in the same decade. This clashes with British political theater now, but there’s no other way forward.

And this even affects domestic British rail planning. London planners are fixated on Paris as their main comparison. This way, they are certain trains must turn slowly at city terminals, requiring additional tracks at Euston and other stations that are or until recently were part of High Speed 2, at a total cost of several billion pounds. In Germany and the Netherlands (at Utrecht) trains can move faster, down to turns of seven to eight minutes on German regional trains and four to five minutes on intercity trains pinching at terminal stations like Frankfurt. But planners in large cities look down on smaller cities; it’s no different from how planners in New York assume that because New York is bigger than Stockholm, Second Avenue Subway’s stations have higher ridership than the stations of Citybanan (in fact, Citybanan’s two stations, located in city center, are significantly busier).

This way, a particular feature of historic Parisian stations – they have a lot of tracks – got turned into something that every city’s train station is assumed to have. It means Eurostar can’t operate into other stations, because there is no surplus of platforms allowing segregating service to the UK away from all other traffic; it also means that planners in the UK that are trying to engineer stations assume British stations must be overbuilt to Parisian specs.

Janno Lieber Lies to New York About Costs and Regulations

After being criticized about the excessive size of subway stations designed on his watch, MTA head Janno Lieber fired back defending the agency’s costs. In a conversation with the Manhattan Institute, he said about us, “They’re not wrong that the stations are where the MTA stations add cost. But they are wrong about how they compare us – the cost per mile is misleading” (see discussion on social media here). Then he blamed labor and the fire code. Blaming labor is a small but real part of the story; this is common among the white-collar managers Eric and I have talked to, and deserves a separate explanation for why this concern is overblown. But the issue of the fire code is fraud, all the way.

I’ve previously seen some journalists and advocates who write about American construction costs talk about fire safety, which is mentioned occasionally as a reason designs cannot be changed. It’s not at all what’s going on, for two separate reasons, each of which, alone, should be grounds to dismiss Lieber and ensure he never works for the state again.

The first reason is that the fire safety regulation in the United States for train stations, NFPA 130, has been exported to a number of other countries, none of which has American costs or the specific American tradition of overbuilding stations. China uses NFPA 130. So does Turkey. Spain uses a modification. We can look at their designs and see that they do not build oversize stations. I’ve seen an environmental impact analysis in Shanghai, with the help of a Chinese student studying this issue who explained the main planning concerns there. I could write an entire blog post about China (not a 10,000-word case report, of course), but suffice is to say, if the train is projected to be 160 m long, the station dig will be that plus a few meters – and Chinese stations have mezzanines as I understand it. Spanish and Turkish stations have little overage as well; building a dig twice as long as the station’s platforms to house back-of-the-house spaces is unique to most (not all) of the Anglosphere, as design consultants copy bad ideas from one another.

Even the claim that NFPA 130 requires full-length mezzanines is suspect. It requires stations to be built so that passengers can evacuate in four minutes in emergency conditions, rising to six minutes counting stragglers (technically, the throughput needs to be enough to evacuate in four minutes, but with latency it can go up to six). The four minute requirement can be satisfied on the lettered lines of the subway in New York with no mezzanines and just an access point at each end of the platform, but it’s close and there’s a case for another access point in the middle; no full-length mezzanine is required either way. If the stations are any shorter, as on the numbered lines or in other North American cities, two escalators and a wide staircase at the end of each platform are more than enough, and yet the extensive overage is common in those smaller systems too (for example, in Vancouver, the Broadway extension is planned with 128 m long digs for 75 m trains, per p. 9 here).

“Fire safety” is used as an excuse by people with neither engineering background nor respect for anything quantitative or technical. Lieber is such a person: his background is in law and he seems incurious about technical issues (and this is also true of his successor at MTA Capital Construction, public policy grad Jamie Torres-Springer).

Perhaps due to this lazy incuriosity, Lieber didn’t notice that the MTA has extensive influence on the text of NFPA 130, bringing us to the second reason his claim is fraudulent. NFPA 130 is not to blame – again, it’s the same code as in a number of low- and medium-cost countries – but Nilo Cobau explains that the NFPA process is such that big agencies have considerable input, since there aren’t many places in the US that build subways. Nolan Hicks pointed out in the same thread, all linked in the lede paragraph, that the MTA has a voting member and two alternates on the board that determines NFPA 130 and hasn’t requested changes – and that Montreal, subject to the same codes, built a station with little overage (he says 160 m digs for 150 m platforms).

The handwaving of a fire code that isn’t even different from that of cheaper places is there for one purpose only: to deflect blame. It was a struggle to get Lieber and other New York leaders to even admit they have high costs, so now they try to make it the fault of anyone but themselves: fire safety regulations, organized labor, what have you.

Labor is a real issue, unlike fire safety, but it’s overblown by managers who look down on line workers and have generally never been line workers. Lieber graduated law school, was hired by USDOT at either junior-appointed or mid-level civil servant role, I can’t tell which, and then did managerial jobs; his successor as head of MTA Construction and Development, Jamie Torres-Springer, graduated public policy. These aren’t people who worked themselves up from doing engineering, architecture, planning, or ethnographic work; add the general hostility American white-collar workers have toward blue-collar workers, and soon people in that milieu come to believe that just because their top 5%er wages are much higher than they could earn anywhere else in the world, the sandhogs also earn much more than they could anywhere else in the world, when in truth New York sandhog and Stockholm miner wages and benefits are very close.

Occasionally the point that it’s not wages but labor productivity seeps in. There, at last, we see a real problem with labor. Eric and I found that about a third of the sandhogs on Second Avenue Subway didn’t really need to be there. Further cuts could be achieved through the use of more labor-efficient techniques, which the MTA is uninterested in implementing. The rest of the American labor premium comes from excessive staffing of white-collar supervisors, including representatives from each utility, which insists that the MTA pay for the privilege of having such representatives tell them what they can and cannot do in lieu of mapping the utilities and sending over the blueprints. All included, labor was around 50% of the cost of Second Avenue Subway, where the norm in Italy, Turkey, and Sweden is around 25% (note how higher-wage Sweden is the same as lower-wage Italy and much lower-wage Turkey); excessive labor costs contributed a factor of 1.5 premium to the project, but the other factor of 6 came from excessive station size, deep mining of stations (which thankfully will not happen at 106th and 116th Street; it will at 125th but that’s unavoidable), lack of system standardization, and a litany of project delivery problems that are generally getting worse with every iteration. Lieber personally takes credit for some of the privatization of planning to design-build consultancies, though to be fair to him, the project delivery problems predate him, he just made things slightly worse.

A New York that wants to build will not have incompetent political appointees in charge. It will instead hire professionals with a track record of success; as no such people exist within the American infrastructure construction milieu, it should use its own size and prestige to find someone from a low-cost city to hire, who will speak English with an accent and know more engineering than American legal hermeneutics. And it will not reward people who defraud the public about the state of regulations just because they’re too lazy to know better.

The United States Learned Little from Obama-Era Rail Investment

A few days ago, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) announced Bipartisan Infrastructure Law grants for intercity rail that are not part of the Northeast Corridor program. The total amount disbursed so far is $8.2 billion; more will come, but the slate of projects funded fills me with pessimism about the future of American intercity rail. The total amount of money at stake is a multiple of what the Obama-era stimulus offered, which included $8 billion for intercity rail. The current program has money to move things, but is repeating the mistakes of the Obama era, even as Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg clearly wants to make a difference. I expect the money to, in 10 years, be barely visible as intercity rail improvement – just enough that aggrieved defenders will point to some half-built line or to a line where the program reduced trip times by 15 minutes for billions of dollars, but not enough to make a difference to intercity rail demand.

What happened in the Obama era

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), better known as the Obama stimulus, included $8 billion for what was branded as high-speed rail. Obama and Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood spoke favorably of European and East Asian high-speed rail at the time. And yet, the impetus to spread the money across multiple states’ programs meant that the sum was, by spending, around half for legacy rail projects euphemistically branded as higher-speed rail, a term that denotes “faster than the Amtrak average.” Ohio, Wisconsin, and Illinois happily applied that term to slow lines. The other half went to the Florida and California programs, which were genuinely high-speed rail. In Florida, the money was enough to build the first phase from Orlando to Tampa, together with a small state contribution.

Infamously, Governor Rick Scott rejected the money after he was elected in the 2010 midterms, and so did Governors Scott Walker (R-WI) and John Kasich (R-OH). The money was redistributed to states that wanted it, of which the largest sums went to California and Illinois. And yet, what California got was a fraction of the $10 billion that the High-Speed Rail Authority had been hoping for when it went to ballot in 2008; in turn, the cost overruns that were announced in 2011 meant that even the original hoped-for sum could not build a usable segment. The line has languished since, to the point that Governor Gavin Newsom said “let’s be real” regarding the prospects of finishing the line. Planning is continuing, and the mostly funded, under-construction segment connecting Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced is slated to open 2030-33 (in 2008 the promise was Los Angeles-San Francisco by 2020), but this is a fraction of what was promised by cost or utility; Newsom even defended the Bakersfield-Merced segment on the merits, saying that connecting three small, decentralized metro areas to one another with no onward service to Los Angeles or San Francisco would provide good value and taking umbrage at the notion that it was a “train to nowhere.”

In Illinois, the money went toward improving the Chicago-St. Louis line. However, Union Pacific owns the tracks and demanded, as a precondition of allowing faster trains, that the money be spent on increasing its own capacity, leading to double-tracking on a line that only run five trains a day in each direction; service opened earlier this year, cutting trip times from 5:20-5:35 in 2010 to 4:46-5:03 now, at a cost of $2 billion. This is a 457 km line; the cost per kilometer was not much less than that of the greenfield commuter line to Lahti, which has an hourly commuter train averaging 96 km/h from Helsinki and a sometimes hourly, sometimes bihourly intercity train averaging 120. In effect, UP extracted so much surplus that a small improvement to an existing line cost almost as much as a greenfield medium-speed line.

Lessons not learned

The failure of the ARRA to lead to any noticeable improvement in rail service can be attributed to a number of factors:

- The money was spread thinly to avoid favoring just one state, which was perceived as politically unacceptable (somehow, spending money on a flashy project with no results to show for it was perceived as politically acceptable).

- The federal government could only spend the money on projects that the states planned and asked for – there was no independent federal planning.

- There was inattention to best practices in legacy rail planning, such as clockface timetabling, higher cant deficiency (allowed by FRA regulation since 2010), etc.; while the high-speed rail program aimed to imitate European and East Asian examples, the legacy program had little interest in doing so, even though successful legacy rail improvements in such countries as the UK, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands were available already.

- A dual mandate of both jobs and infrastructure, so that high costs were a positive to an interest group that the federal government and the states announced they wanted to support.

- California specifically was a series of unforced errors, including a politicized High-Speed Rail Authority board representing parochial rather than statewide interests, disinterest in developing any state capacity to plan things (the expression “state capacity” wouldn’t even enter common American political discourse until the late 2010s), early commitment, and, once the combo of cost overruns and insufficient money on hand meant the project had no hope of finishing in the political lifetime of anyone important, disinterest in expediting things.

I have not seen any indication that Buttigieg and his staff learned any of these lessons, and I have seen some indication that they have not.

For one, the dual mandate problem is if anything getting worse, with constant invocations of job creation even as unemployment is below 4% where in 2010 it was 10%, and with growing protectionism; the US has practically no internal market for modern rolling stock and the recent spate of protectionism is leading to surging costs, where until recently there was no American rolling stock cost premium. This is not an intercity rail problem but an infrastructure problem in general in the US, and every time a politician says “this will create jobs,” a surplus-extracting actor gets their wings.

Then, even though the NGO space has increasingly been figuring out some best practices for regional trains, there is still no integration of these practices into infrastructure planning. The allergy to electrification remains, and mainline rail agency officials keep making things up about rest-of-world practices and getting rewarded for it with funds. Despite wide recognition of the extent of surplus extraction by the Class I freight carriers, there is no attempt to steer funding toward lines that are already owned by passenger rail-focused public-sector carriers, like the Los Angeles-San Diego line, much of the Chicago-Detroit line, and the New York-Albany line.

The lack of independent federal planning is if anything getting worse, relative to circumstances. In the Obama era, the Northeast Corridor was put aside. Today, it is the centerpiece of the investment program; I’ve been told that Biden asks about it at briefings about transportation investment and views it as his personal legacy. Well, it could be, but that would require toothy federal planning, and this doesn’t really exist – instead, the investment program is a staple job of parochial interests. Based on this, I doubt that there’s been any progress in federal planning for intercity rail outside the Northeast.

And finally, the money is still being spread too thinly. California is getting $3.1 billion, which is close to but not quite enough to complete Bakersfield-Merced, whose cost is in year-of-expenditure dollars at this point $34 billion for a 275 km system in the easiest geography it could possibly have. Another $3 billion is slated to go to Brightline West, a private scheme to run high-speed trains from Rancho Cucamonga in exurban Los Angeles, about 65 km from city center, to a greenfield site 4 km south of the Las Vegas Strip; the overall cost of the line is projected at $12 billion over a distance of 350 km. It’s likely that this split is worse than either giving all $6 billion to California or giving all of it to Brightline West. But as I am going to point out in the following section, it’s worse than giving the money to places that are not the Western United States.

The frustrating thing is that, just as I am told that Biden deeply cares about the Northeast Corridor, Buttigieg has been quoted as saying that he cares about developing at least one high-speed rail line, as a legacy that he can point to and say “I did that.” Buttigieg is a papabile for the 2028 presidential primary, and is young enough he can delay running for many cycles if he feels 2028 is not the right time, to the point that “I built that” will strengthen his political prospects even if he has to wait until opening in the 2030s. And yet, the money committed will not build high-speed rail. It might build a demonstration segment in California, but a Bakersfield-Fresno line and even a Bakersfield-Merced one with additional funds would scream “white elephant” to the general public.

Is it salvagable?

Yes.

There are, as I understand it, $21.8 billion in uncommitted funds.

What the $21.8 billion is required to achieve is a) a complete high-speed line, b) not touching the Northeast Corridor (which is funded separately and also poorly), c) connecting cities of sufficient size that passenger ridership would make people say “this is a worthy government investment” rather than “this is a bridge to nowhere on steroids.” Even a complete Los Angeles-Las Vegas line is not guaranteed to be it, and Brightline West is saving money by dumping passengers tens of kilometers along congested roads from Downtown Los Angeles.

Given adequate cost control, Chicago-Detroit/Cleveland is viable. It’s around 370 km Chicago-Toledo, 100 km Toledo-Detroit, 180 km Toledo-Cleveland, depending on alignments chosen; $21.8 billion can build it at the same cost projected for Brightline West, in easier topography. If money is almost but not quite enough, then either Cleveland or Detroit can be dropped, which would make the system substantially less valuable but still create some demand for completing the system (Michigan could fund Toledo-Detroit with state money, for example).

But this means that all or nearly all of the remaining funds need to go into that one basket, and Buttigieg needs to gamble that it works. This requires federal coordination – none of the four states on the line has the ability to plan it by itself, and two of them, Indiana and Ohio, are actively hostile. It’s politically fine as a geographic split as it is – that part of the Midwest is sacralized in American political discourse due to its industrial history, which history has also supplied it with large cities that could fill trains to Chicago and even to one another; politicians can more safely call Los Angeles “not real America” than they can Detroit and Cleveland.

But so far, the way the Northeast Corridor money and the recently-announced $8.2 billion for non-Northeast Corridor service have been spent fills me with confidence that this will not be done. The program is salvageable, but I don’t think it will be salvaged. There’s just no interest in having the federal government do this by itself as far as I can see, and the state programs are either horrifically expensive (California) or too compromised (Midwest, Southeast, Pacific Northwest).

So what I expect will happen is more spreading of the money to lines averaging 100 km/h or less, plus maybe some incomplete grants to marginal high-speed lines (Atlanta-Charlotte is a contender, but would get little traffic until it connects to the Northeast Corridor and would cost nearly the entire remaining pot). Every government source will insist that this is high-speed rail. Some parts will be built and end up failing to achieve much, like Chicago-St. Louis. Every person who is not already bought in will learn that the government is inefficient and it’s better to cut taxes instead, as is already done in Massachusetts. Americans will keep making excuses for why it’s just not possible to have what European and a growing list of Asian countries have, or perhaps why there’s no point in it since if it were good it would have been invented by the American private sector.

The MTA Sticks to Its Oversize Stations

In our construction costs report, we highlighted the vast size of the station digs for Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 as one of the primary reasons for the project’s extreme costs. The project’s three new stations cost about three times as much as they should have, even keeping all other issues equal: 96th Street’s dig is about three times as long as necessary based on the trains’ length, and 72nd and 86th Street’s are about twice as long but the stations were mined rather than built cut-and-cover, raising their costs to match that of 96th each. In most comparable cases we’ve found, including Paris, Istanbul, Rome, Stockholm, and (to some extent) Berlin, station digs are barely longer than the minimum necessary for the train platform.

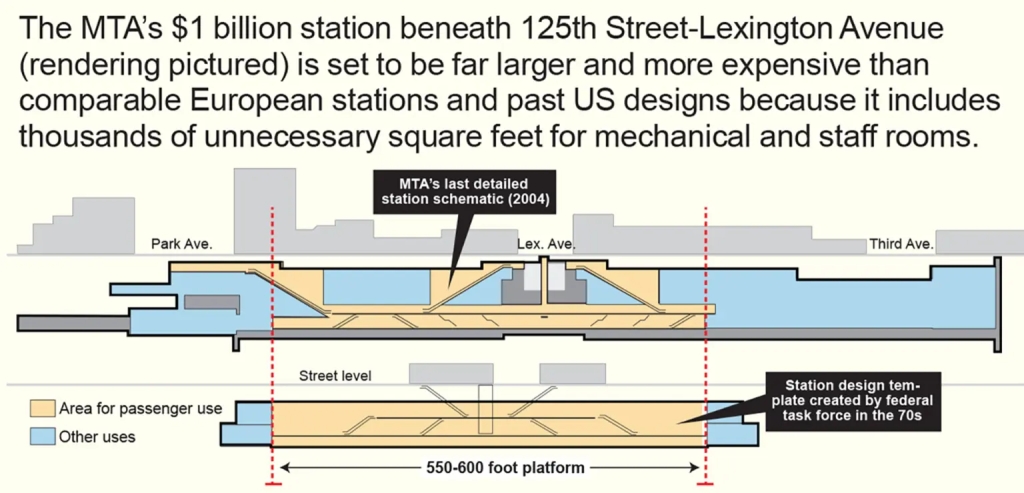

MTA Construction and Development has chosen to keep building oversize stations for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, a project that despite being for the most part easier than the already-open Phase 1, is projected to cost slightly more per kilometer. Nolan Hicks at the New York Post just published a profile diagram:

The enormous size of 125th Street Station is not going to be a grand civic space. As the diagram indicates, the length of the dig past the platforms will not be accessible to passengers. Instead, it will be used for staff and mechanical rooms. Each department wants its own dedicated space, and at no point has MTA leadership told them no.

Worse, this is the station that has to be mined, since it goes under the Lexington Avenue Line. A high-cost construction technique here is unavoidable, which means that the value of avoiding extra costs is higher than at a shallow cut-and-cover dig like those of 106th and 116th Streets. Hence, the $1 billion hard cost of a single station. This is an understandable cost for a commuter rail station mined under a city center, with four tracks and long trains; on a subway, even one with trains the length of those of the New York City Subway, it is not excusable.

When we researched the case report on Phase 1, one of the things we were told is that the reason for the large size of the stations is that within the MTA, New York City Transit is the prestige agency and gets to call the shots; Capital Construction, now Construction and Development, is smaller and lacks the power to tell NYCT no, and from NYCT’s perspective, giving each department its own break rooms is free money from outside. One of the potential solutions we considered was changing the organizational chart of the agency so that C&D would be grouped with general public works and infrastructure agencies and not with NYCT.

But now the head of the MTA is Janno Lieber, who came from C&D. He knows about our report. So does C&D head Jamie Torres-Springer. When one of Torres-Springer’s staffers said a year ago that of course Second Avenue Subway needs more circulation space than Citybanan in Stockholm, since it has higher ridership (in fact, in 2019 the ridership at each of the two Citybana stations, e.g. pp. 39 and 41, was higher than at each of the three Second Avenue Subway stations), the Stockholm reference wasn’t random. They no longer make that false claim. But they stick to the conclusion that is based on this and similar false claims – namely, that it’s normal to build underground urban rail stations with digs that are twice as long as the platform.

When I call for removing Lieber and Torres-Springer from their positions, publicly, and without a soft landing, this is what I mean. They waste money, and so far, they’ve been rewarded: Phase 2 has received a Full Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) from the United States Department of Transportation, giving federal imprimatur to the transparently overly expensive design. When they retire, their successors will get to see that incompetence and multi-billion dollar waste is rewarded, and will aim to imitate that. If, in contrast, the governor does the right thing and replaces Lieber and Torres-Springer with people who are not incurious hacks – people who don’t come from the usual milieu of political appointments in the United States but have a track record of success (which, in construction, means not hiring someone from an English-speaking country) – then the message will be the exact opposite: do a good job or else.

Quick Note: Anti-Green Identity Politics

In Northern Europe right now, there’s a growing backlash to perceived injury to people’s prosperity inflicted by the green movement. In Germany this is seen in campaigning this year by the opposition and even by FDP not against the senior party in government but against the Greens. In the UK, the (partial) cancellation of High Speed 2 involved not just cost concerns but also rhetoric complaining about a war on cars and shifting of high-speed rail money to building new motorway interchanges.

I bring this up for a few reasons. First, to point out a trend. And second, because the Berlin instantiation of the trend is a nice example of what I talked about a month ago about conspiracism.

The trend is that the Green Party in Germany is viewed as Public Enemy #1 by much of the center-right and the entire extreme right, the latter using the slogan “Hang the Greens” at some hate marches from the summer. This is obvious in state-level political campaigning: where in North-Rhine-Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein the unpopularity of the Scholz cabinet over its weak response to the Ukraine war led to CDU-Green coalitions last year (the Greens at the time enjoying high popularity over their pro-Ukraine stance), elections this year have produced CDU-SPD coalitions in Berlin and Hesse, in both cases CDU choosing SPD as a governing partner after having explicitly campaigned against the Greens.

This is not really out of any serious critique of the Green Party or its policy. American neoliberals routinely try to steelman this as having something to do with the party’s opposition to nuclear power, but this doesn’t feature into any of the negative media coverage and barely into any CDU rhetoric. It went into full swing with the heat pump law, debated in early summer.

In Berlin the situation has been especially perverse lately. One of the points made by CDU in the election campaign was that the red-red-green coalition failed to expand city infrastructure as promised. It ran on more room for cars rather than pedestrianization, but also U-Bahn construction; when the coalition agreement was announced, Green political operatives and environmental organizations on Twitter were the most aghast at the prospects of a massive U-Bahn expansion proposed by BVG and redevelopment of Tempelhofer Feld.

And then this month the Berlin government, having not made progress on U-Bahn expansion, announced that it would trial a maglev line. There hasn’t been very good coverage of this in formal English-language media, but here and here are writeups. The proposal is, of course, total vaporware, as is the projected cost of 80 million € for a test line of five to seven kilometers.

This has to be understood, I think, in the context of the concept of openness to new technology (“Technologieoffenheit”), which is usually an FDP slogan but seems to describe what’s going on here as well. In the name of openness to new tech, FDP loves raising doubts about proven technology and assert that perhaps something new will solve all problems better. Hydrogen train experiments are part of it (naturally, they failed). Normally this constant FUD is something I associate with people who are out of power or who are perpetually junior partners to power, like FDP, or until recently the Greens. People in power prefer to do things, and CDU thinks it’s the natural party of government.

And yet, there isn’t really any advance in government in Berlin. The U8 extension to Märkisches Viertel is in the coalition agreement but isn’t moving; every few months there’s a story in the media in which politicians say it’s time to do it, but so far there are no advances in the design, to the point that even the end point of the line is uncertain. And now the government, with all of its anti-green fervor – fervor that given Berlin politics includes support for subway construction – is not so much formally canceling it as just neglecting it, looking at shiny new technologies that are not at all appropriate for urban rail just because they’re not regular subways or regular commuter trains, which don’t have that identity politics load here.

The Northeast Corridor Rail Grants

The US government has just announced a large slate of grants to rail from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Amtrak has a breakdown of projects both for itself and partners, totaling $16.4 billion. There are a few good things there, like Delco Lead, or more significantly more money for the Hudson Tunnel Project (already funded separately, but this covers money the states would otherwise be expected to fund). There are also conspicuously missing items that should stay missing – But by overall budget, most of the grant is pretty bad, covering projects that are in principle good but far too expensive per minute saved.

This has implications to the future of the Northeast Corridor, because the total amount of money for it is $30 billion; I believe this includes Amtrak plus commuter rail agencies. Half of the money is gone already, and some key elements remain unfunded, some of which are still on agency wishlists like Hunter Flyover but others of which are still not, like Shell Interlocking. It’s still possible to cobble together the remaining $13.6 billion to produce something good, but there have to be some compromises – and, more importantly, the process that produced the grant so far doesn’t fill me with confidence about the rest of the money.

The Baltimore tunnel

The biggest single item in the grant is the replacement tunnel for the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel. The B&P was built compromised from the start, with atypically tight curves and steep grades for the era. An FRA report on its replacement from 2011 goes over the history of the project, originally dubbed the Great Circle Passenger Tunnel when first proposed in the 1970s; the 2011 report estimates the cost at $773 million in 2010 prices (PDF-p. 229), and the benefits at a two-minute time saving (PDF-p. 123) plus easier long-term maintenance, as the B&P has water leakage in addition to its geometric problems. At the time, the consensus of Northeastern railfans treated it as a beneficial and even necessary component of Northeast Corridor modernization, and the agencies kept working on it.

Since then, the project’s scope crept from two passenger tracks to four tracks with enough space for double-stacked freight and mechanical ventilation for diesel locomotives. The cost jumped to $4 billion, then $6 billion. The extra scope was removed to save money, said to be $1 billion, but the headline cost remained $6 billion (possibly due to inflation, as American government budgeting is done in current dollars, never constant dollars, creating a lot of fictional cost overruns). The FRA grant is for $4.7 billion out of $6 billion. Meanwhile, the environmental impact statements upped the trip time benefit of the tunnel for Amtrak from two to 2.5 minutes; this is understandable in light of either higher-speed (and higher-cost) redesign or an assumption of better rolling stock than in the 2011 report, higher-acceleration trains losing more time to speed restrictions near stations than lower-acceleration ones.

That this tunnel would be funded was telegraphed well in advance. The tunnel was named after abolitionist hero Frederick Douglass; I’m not aware of any intercity or commuter rail tunnel elsewhere in the developed world that gets such a name, and the choice to name it so about a year ago was a commitment. It’s not a bad project: the maintenance cost savings are real, as is the 2.5 minute improvement in trip time. But 2.5 minutes are not worth $6 billion, or even $6 billion net of maintenance. In 2023 dollars, the estimate from 2011 is $1.1 billion, which I think is fine on the margin – there are lower-hanging fruit out there, but the tunnel doesn’t compete with the lowest-hanging fruit but with the $29 billion-hanging fruit and it should be very competitive there. But when costs explode this much, there are other things that could be done better.

Bridge replacements

The Northeast Corridor is full of movable bridges, which are wishlisted for replacement with high fixed spans. The benefits of those replacements are there, mainly in maintenance costs (but see below on the Connecticut River), but that does not justify the multi-billion dollar budgets of many of them. The Susquehanna River Rail Bridge, the biggest grant in this section, is $2.08 billion in federal funding; the environmental impact study said that in 2015 dollars it was $930 million. The benefits in the EIS include lower maintenance costs, but those are not quantified, even in places where other elements (like the area’s demographics) are.

Like all state of good repair projects, this is spending for its own sake. There are no clear promises the way there are with the Douglass Tunnel, which promises to have a new tunnel with trip time benefits, small as they are. Nobody can know if these bridge replacement projects achieved any of their goals; there are no clear claims about maintenance costs with or without this, nor is there any concerted plan to improve maintenance productivity in general.

The East River Tunnel project, while not a bridge nor a visible replacement, has the same problem. The benefits are not made clear anywhere. There are some documents we found in the ETA commuter rail report saying that high-density signaling would allow increasing peak capacity on one of the two tunnel pairs from 20 to 24 trains per hour, but that’s a small minority of the overall project and in the description it’s an item within an item.

The one exception in this section is the Connecticut River. This bridge replacement has a much clearer benefit – but also is a down payment on the wrong choice. The issue is that pleasure boat traffic has priority over the railroad on the “who came first” principle; by agreement with the Coast Guard, there is a limited number of daily windows for Amtrak to run its trains, which work out to about an Acela and a Regional every hour in each direction. Replacing this bridge, unlike the others, would have a visible benefit: more trains could run (once new rolling stock comes in, but that’s already in production).

Unfortunately, the trains would be running on the curviest and also most easily bypassable section of the Northeast Corridor. The average speed on the New Haven-Kingston section of the Northeast Corridor is low, if not so low on the less curvy but commuter rail-primary New Haven Line farther west. The curves already have high superelevation and the Acelas tilt through them fully; there’s not much more that can be done to increase speed, save to bypass this entire section. Fortunately, a bypass parallel to I-95 is feasible here – there isn’t as much suburban development as west of New Haven, where there are many commuters to New York. Partial bypasses have been studied before, bypassing both the worst curves on this section and all movable bridges, including that on the Connecticut. To replace this bridge in place is a down payment on, in effect, not building genuine high-speed rail where it is most useful.

Other items

Some other items on the list are not so bad. The second largest item in the grant, $3.79 billion, is increasing the federal contribution to the Hudson Tunnel Project from about 50% to about 70%. I have questions about why it’s necessary – it looks like it’s covering a cost overrun – but it’s not terrible, and by cost it’s by far the biggest reasonable item in this grant.

Beyond that, there are some small projects that are fine, like Delco Lead, part of a program by New Jersey Transit to invest around New Brunswick and Jersey Avenue to create more yard space where it belongs, at the end of where local trains run (and not near city center, where land is expensive).

What’s not (yet) funded

Overall, around 25% of this grant is fine. But there are serious gaps – not only are the bridge replacements and the Douglass Tunnel not the best use of money, but also some important projects providing both reliability and speed are missing. The two most complex flat junctions of the Northeast Corridor near New York, Hunter in New Jersey and Shell in New Rochelle, are missing (and Hunter is on the New Jersey Transit wishlist); Hunter is estimated at $300 million and would make it much more straightforward to timetable Northeast Corridor commuter and intercity trains together, and Shell would likely cost the same and also facilitate the same for Penn Station Access. The Hartford Line is getting investment into double track, but no electrification, which American railroads keep underrating.