Category: Cars

Transit-Oriented Development and Rail Capacity

Hayden Clarkin, inspired by the ongoing YIMBYTown conference in New Haven, asks me about rail capacity on transit-oriented development, in a way that reminds me of Donald Shoup’s critique of trip generation tables from the 2000s, before he became an urbanist superstar. The prompt was,

Is it possible to measure or estimate the train capacity of a transit line? Ie: How do I find the capacity of the New Haven line based on daily train trips, etc? Trying to see how much housing can be built on existing rail lines without the need for adding more trains

To be clear, Hayden was not talking about the capacity of the line but about that of trains. So adding peak service beyond what exists and is programmed (with projects like Penn Station Access) is not part of the prompt. The answer is that,

- There isn’t really a single number (this is a trip generation question).

- Moreover, under the assumption of status quo service on commuter rail, development near stations would not be transit-oriented.

Trip generation refers to the formula connecting the expected car trips generated by new development. It, and its sibling parking generation, is used in transportation planning and zoning throughout the United States, to limit development based on what existing and planned highway capacity can carry. Shoup’s paper explains how the trip and parking generation formulas are fictional, fitting a linear curve between the size of new development and the induced number of car trips and parked cars out of extremely low correlations, sometimes with an R^2 of less than 0.1, in one case with a negative correlation between trip generation and development size.

I encourage urbanists and transportation advocates and analysts to read Shoup’s original paper. It’s this insight that led him to examine parking requirements in zoning codes more carefully, leading to his book The High Cost of Free Parking and then many years of advocacy for looser parking requirements.

I bring all of this up because Hayden is essentially asking a trip generation question but on trains, and the answer there cannot be any more definitive than for cars. It’s not really possible to control what proportion of residents of new housing in a suburb near a New York commuter rail stop will be taking the train. Under current commuter rail service, we should expect the overwhelming majority of new residents who work in Manhattan to take the train, and the overwhelming majority of new residents who work anywhere else to drive (essentially the only exception is short trips on commuter rail, for example people taking the train from suburbs past Stamford to Stamford; those are free from the point of view of train capacity). This is comparable mode choice to that in the trip and parking generation tables, driven by an assumption of no alternative to driving, which is correct in nearly all of the United States. However, figuring out the proportion of new residents who would be commuting to Manhattan and thus taking the train is a hard exercise, for all of the following reasons:

- The great majority of suburbanites do not work in the city. For example, in the Western Connecticut and Greater Bridgeport Planning Regions, more or less coterminous with Fairfield County, 59.5% of residents work within one of these two regions, and only 7.4% work in Manhattan as of 2022 (and far fewer work in the Outer Boroughs – the highest number, in Queens, is 0.7%). This means that every new housing unit in the suburbs, even if it is guaranteed the occupant works in Manhattan, generates demand for more destinations within the suburb, such as retail and schools.

- The decision of a city commuter to move to the suburbs is not driven by high city housing prices. The suburbs of New York are collectively more expensive to live in than the city, and usually the ones with good commuter rail service are more expensive than other suburbs. Rather, the decision is driven by preference for the suburbs. This means that it’s hard to control where the occupant of new suburban housing will work purely through TOD design characteristics such as proximity to the station, streets with sidewalks, or multifamily housing.

- Among public transportation users, what time of day they go to work isn’t controllable. Most likely they’d commute at rush hour, because commuter rail is marginally usable off-peak, but it’s not guaranteed, and just figuring the proportion of new users who’d be working in Manhattan at rush hour is another complication.

All of the above factors also conspire to ensure that, under the status quo commuter rail service assumption, TOD in the suburbs is impossible except perhaps ones adjacent to the city. In a suburb like Westport, everyone is rich enough to afford one car per adult, and adding more housing near the station won’t lower prices by enough to change that. The quality of service for any trip other than a rush hour trip to Manhattan ranges from low to unusable, and so the new residents would be driving everywhere except their Manhattan job, even if they got housing in a multifamily building within walking distance of the train station.

This is a frustrating answer, so perhaps it’s better to ask what could be modified to ensure that TOD in the suburbs of New York became possible. For this, I believe two changes are required:

- Improvements in commuter rail scheduling to appeal to the growing majority of off-peak commuters as well as to non-commute trips. I’ve written about this repeatedly as part of ETA but also the high-speed rail project for the Transit Costs Project.

- Town center development near the train station to colocate local service functions there, including retail, a doctor’s office and similar services, a library, and a school, with the residential TOD located behind these functions.

The point of commercial and local service TOD is to concentrate destinations near the train station. This permits trip chaining by transit, where today it is only viable by car in those suburbs. This also encourages running more connecting bus service to the train station, initially on the strength of low-income retail workers who can’t afford a car, but then as bus-rail connections improve also for bus-rail commuters. The average income of a bus rider would remain well below that of a driver, but better service with timed connections to the train would mean the ridership would comprise a broader section of the working class rather than just the poor. Similarly, people who don’t drive on ideological or personal disability grounds could live in a certain degree of comfort in the residential TOD and walk, and this would improve service quality so that others who can drive but sometimes choose not to could live a similar lifestyle.

But even in this scenario of stronger TOD, it’s not really possible to control train capacity through zoning. We should expect this scenario to lead to much higher ridership without straining capacity, since capacity is determined by the peak and the above outline leads to a community with much higher off-peak rail usage for work and non-work trips, with a much lower share of its ridership occurring at rush hour (New York commuter rail is 67-69%, the SNCF part of the RER and Transilien are about 46%, due to frequency and TOD quality). But we still have no good way of controlling the modal choice, which is driven by personal decisions depending on local conditions of the suburb, and by office growth in the city versus in the suburbs.

Quick Note: Rural Drivers Aren’t Being Oppressed

A new paper is making the round arguing that Spanish rural automobility is a response to peripheralization. It’s a mix of saying what is obvious – in rural areas there is no public transportation and therefore cars are required for basic mobility – and proposing this as a way of dealing with the general marginalization of people in rural areas. The more obvious parts are not so much wrong as underdeveloped – the paper is an ethnography of rural drivers who say they need to drive to get to work and to non-work destinations like child care. But then the parts talking about peripheralization are within a program of normalizing rural violence against the state and against urban dwellers, and deserves a certain degree of pushback.

The issue here is that while rural areas are poorer than urban ones, making them economically more peripheral, they are not at all socially peripheral. This can be seen in a number of both economic and non-economic issues:

- Rural areas are showered with place-based subsidies to deal with poverty, on top of the usual universal programs (like health care and pensions) that redistribute money from rich to poor regardless of location. This includes farm subsidies, like the Common Agricultural Policy, and infrastructure subsidies in which there’s more investment relative to usage in rural than in urban areas. The automobility of rural areas is itself part of this program: urban motorways can fund themselves from tolls where they need to, but national programs of road improvements end up improving the mobility options of rural areas out of almost exclusively urban taxes. In public transport, this includes considerable political entitlement, such as when Spanish regional governors made a botched train procurement into a national scandal and demanded that the chief of staff of the national transport ministry, Isabel Pardo de Vera Posada, resign over something she’d had nothing to do with.

- Rural poverty is culturally viewed as the fault of other people than the residents. Poor urban neighborhoods are called no-go zones; I am not familiar enough with Spanish discourse on this but I doubt it’s different from French, German, and Swedish discourses, in which poor rural areas are never so called. A German district with neo-Nazi groups and majority public sympathy with extremism is called a victim of globalization in media, even left-leaning media, and not a no-go zone.

- Rural areas, regardless of income, are socially treated as more authentic representatives of proper values, with expressions like Deep England or La France profonde contrasting with constant scorn for London, Paris, and Berlin.

- Rural violence is treated as almost respectable. Political and media reactions to farmer riots with tractors as of late have been to shower the rioters with understanding. In France, the government acceded to the demands, and then-minister of the interior Gérald Darmanin forced law enforcement to act with restraint. In contrast, urban riots by racial minorities lead to mass arrests, the occasional fatal shooting of a rioter, and a discourse that treats riots as fundamentally illegitimate, for example just a few months prior.

The paper denigrates rural policies formed with “barely any understanding of how they are conditioned” and says that “an understanding of socio-spatial cohesion needs to look beyond the traditional objectives of equalizing agricultural incomes to consider how these accessibility gaps affect depopulation, young people’s skills, unemployment and low incomes.” But the issue isn’t understanding. Rural areas are not misunderstood. They are dominant, capable of steering specific subsidies their way that are not available to urbanites at equal income levels.

More broadly, I think it’s difficult for critical urbanism to deal with this issue of the permission structure for rural violence, because the urban-rural dynamic is not the same as the classical dynamic between social classes, or between white and black Americans, in which the socioeconomically dominant group is also the politically dominant one. It’s instead better to analogize it in ethnic terms not to American anti-black racism, or to European anti-immigrant racism, but to anti-Semitism, in which the social acceptance of a base level of violence coexists with the fact that Jews are often a more educated and richer group, leading anti-Semites to promulgate conspiracy theories.

The permission structure for rural drivers to commit violence in demand of government subsidies and government protection from competition is the exact opposite of peripheralization. It’s not a periphery; it’s a political and cultural center that faces a fundamental challenge in that it provides no economic or social value and is in effect a rapacious mafia using violence to extract protection money from an urban society that, due to misplaced sentimental values, responds with further subventions rather than with the full force of law as used against urban and suburban rioters with migration background.

Large Cars are a Positional Good

Americans have, over the last generation, gotten ever larger cars, to the point that the market is dominated by crossovers, pickup trucks, and SUVs and barely has sedans. Europe is not far behind, with the sedan market having collapsed and half of new sales comprising SUVs. Considerable resources are spent on these larger cars, which are more expensive to purchase, maintain, and refuel. The benefits at this point, however, are rather positional. The benefit of larger cars at this point is not about the comfort or performance of the car, but about being larger than other road users. Streets for All’s Michael Schneider described it as an arms race; this arms race that wastes resources and produces pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, without benefits even to individuals writ large, precisely the kind of problem that government regulation can solve.

The benefits of larger cars

The usual benefit drivers cite for why they want a larger car is comfort. The increase in car size from (say) the Fiat 500 or the Beetle or the 1970s Civic to modern midsize cars like the Accord and Camry has led to obvious improvements in comfort: four doors rather than two, ample front and rear passenger legroom, more trunk space.

And beyond this point, the relationship between car size and comfort saturates. Luxury sedans are still larger than midsize ones, but not by much; where the 500 had a curb weight of about 500 kg, the modern Accord is 1.4 t and the Camry is 1.6 t, barely less than a C-Class at 1.7 t and not much less than a 2.1 t 7 Series. A family car does not need to be larger than this, and when I talk to people about their vehicle purchases, at least the ones who tell me they’re getting SUVs do not cite comfort, not in the 2010s-20s.

The main selling point of luxury cars is performance. It’s this high-performance segment that Tesla competes with – electric cars have better performance specs, and where the older automakers tried to base their electric car offerings on preexisting platforms (like the Leaf, based on the Tiida), Tesla instead started by building high-performance luxury cars and expanded from there. But here there is no benefit to size – the Model 3 is around 1.7 t curb weight, and that includes batteries, which together weigh nearly half a ton.

Larger cars can also haul more goods, but the SUVs and pickups are expressly designed not to do that. The F-150’s bed has decreased with every new generation of the car; the Kei truck, specialized to have a large bed relative to the rest of the car, looks so weird to Americans that Massachusetts at one point banned it for being unsafe, while Americans on social media mocked the users as trying to prove an environmental point. The minivan, specialized to carry seven to eight passengers, has been unfashionable for at least a generation, losing out to the similarly large but lower-capacity SUV.

Instead, what I do hear from people telling me why they want a big car is purely positional: “I get to see over the other cars,” or alternatively “I can’t be the shortest car on the road because then I can’t see anything.” People are also recorded modifying their cars to be taller for the same reasons. The visibility in question does not improve if all cars get bigger; only the relative size matters. In the case of car accidents, this is even worse: in a collision between two cars the larger one is safer for the occupants, but making all the cars larger doesn’t improve traffic safety, and makes it much worse for pedestrians, and there’s some evidence of risk compensation by drivers of larger cars increasing the overall number of crashes.

The discourse on social benefits tends to exclude individual ones; thus, it’s easy to say that something that provides tangible individual benefits (such as larger dwellings) does not provide social ones. But this is something different. A purely private good does not provide positive externalities or improve the usual indicators that are usually the realm of public policy, like public health, but it improves the living standards of the owner, without negative externalities. But here, the benefit of the SUV or pickup truck to the user is purely the arms race on the road; the improvement in the quality of life of the owner is entirely about externalizing a fixed or even rising risk of car crashes to other road users. There isn’t even a social benefit here in the sense of the sum total of private individual benefits.

The costs of larger cars

While larger cars do not improve societal well-being on average, they have high individual and social costs.

The social costs are easier to explain: those cars emit much more pollution and greenhouse gases. The Camry has a fuel economy of maybe 37 miles per gallon (6.35 l/100 km) in the US; the F-150 gets less than half that, around 17.5 mpg (13.4 l/100 km). The fuel consumption ratio, 2.1, is somehow larger than the mass ratio – the F-150 doesn’t weigh 3.4 t but rather not much more than 2 t depending on model. Air pollution emissions are, for modern cars with modern petrol engines, proportional to greenhouse gas emissions; a car with twice the fuel consumption is going to also emit twice the particulate matter.

Then there is the danger of crashes. The United States has seen an increase in traffic fatalities lately, especially for pedestrians. The pedestrian fatality rate, in turn, comes from the form of pickups and larger SUVs: they have larger hoods, which hit pedestrians in the chest or (for children) the head rather than in the legs, and which also reduce visibility. Here it’s not an issue of mass but one of hood shape, but these come from the same fundemantal issue of an arms race to be larger and taller than the other cars, to the exclusion of spending on personal comfort.

Those social costs are not the tradeoff of some individual benefit. There is a benefit to the driver of the larger car, but there is no benefit to the driver of the average car on a road with larger cars. Instead, the driver of said average car incurs significant individual costs, coming from the need to buy, maintain, and refuel a larger machine. The low fuel economy costs the drivers money; most of the costs are external, but not all. The purchase price of a larger car is larger, because it is a larger piece of machinery, requiring more workers and more capital to put together; Edmunds’ price range for the F-150 is 50-100% higher than that for the Accord or Camry. Consumers routinely spend more money for better products, but here the product is not better except positionally.

The way forward

Government regulations to curb the arms race can directly limit or tax the size of cars, or instead go after their negative externalities. The latter should be preferred; in particular, a tax on car size would create a situation in which people can pay for a road that is safer for them and more dangerous for others, which is likely to lead to both much more aggressive driving by the largest cars on the road and to populist demands for large cars for everyone.

Specific taxes on large cars may still be appropriate in specific circumstances, like parking; Paris charges SUVs more for parking, justified by the fact that these vehicles don’t fit in the usual street parking spots, which are designed for the typical European car and not for the largest ones.

But outside the issue of parking, it’s better to be tighter about regulations and taxes on pollution, and about accidents. In the United States, it’s necessary to get rid of the system in which cars are perennially underinsured, with most states requiring liability coverage of $50,000 (Cid’s car accident, which was medium-term disabling but not fatal, incurred around $1 million in bills, and the insurance value of human life in the United States is $7.5 million). On both sides of the Atlantic, it’s necessary to tax or regulate pollution more seriously; the EU is ramping up fines on automakers that produce excessively polluting vehicles, but Robert Habeck, who is rather rigid on issues like nuclear power and the Autobahn speed limit, wants to suspend those fines since German automakers lag in electric cars.

On the matter of safety, it’s best to require cars to meet high standards of visibility and pedestrian safety in crashes, measured for example by survival rates at typical city speeds like 30 and 50 km/h. A car that fails these standards should not be on the road, just as cars are tested for occupant safety. If it means that the high, deep hood characteristic of the pickup truck no longer meets regulations, then fine; safety regulators should not compromise just because some antisocial drivers are acculturated to playing Carmageddon on real roads.

The key here is that regulations on emissions and personal injury liability suppress investment in larger cars, and that is good. There are other forms of capital investment in the economy competing for funding, which are not purely positional, for example housing, where German investment has been lagging due to high interest rates. Externalities are a real market failure and sometimes they get to the point that the product is, at scale, a net negative for society.

What it Means That Miri Regev Wants to Cancel Congestion Pricing

Minister of Transportation Miri Regev is trying to cancel the Tel Aviv congestion pricing plan, slated to begin operations in 2026. Congestion pricing is still planned to happen, but 2026 is already behind schedule due to delays on past contracts required to set up the gantries. The plan is still to go ahead and use the revenue to help fund the Tel Aviv Metro project, to comprise three driverless metro lines at regional scale to complement both the longer-range commuter trains and the shorter-range Light Rail system, which opened last year with a subway segment after several decades of design and construction. But Regev has wanted to cancel it since she became transportation minister early last year, and her latest excuse is the war, never mind that usually during war one raises taxes and aims to restrain private consumption such as personal vehicle driving.

I bring this up partly to highlight that Regev has not been a good minister; the civil servants at the ministry quickly found that she routinely bypasses them, makes decisions purely with her own political team, and sometimes doesn’t even inform them before making public announcements. More recently, she’s been facing corruption investigations, since much of the above behavior is not legal in Israel, a country where one says “the state” with a positive connotation that exists in French and German but not in English.

But more than that, I bring this up to highlight the contrast between Regev and New York Governor Kathy Hochul, who outright canceled the New York congestion pricing plan last month on no notice, weeks before it was about to debut rather than years. At a personal level, Regev is a worse person than Hochul. But Regev’s ability to cause damage is constrained by far stronger state institutions. The cabinet can collectively decide to cancel congestion pricing, in the same way a state legislature could repeal its own laws, but that would involve extensive open debate within the coalition. Thus, the ministry of finance already said that if the ministry of transportation is bowing out, it will have to take over the program, since it’s necessary for financing the metro, which is still on-budget; the civil servants at finance have long drawn ire from populists over their control over the budget, called the Arrangements Law, and unless the metro is formally canceled, the money will have to come from somewhere.

A formal repeal is still possible, but it cannot be done on a whim. Netanyahu, an atypically monarchical prime minister in both power within the coalition and aspirations, might be able to swing it if he wants, but he’d still have to persuade coalition partners. His power derives from long-term deals with junior parties that are so widely loathed they feel like they have to stick with him, and from over time turning Likud into a party of personal loyalists; at the same time, he has to govern roughly within the spectrum of opinions of the loyalists, and while their opinions on the biggest issues facing the state align with his or else they would not be in this position, on issues like transportation they may have different opinions and express them. At no point does a loyalist like Regev get absolute control of one aspect of policy; the coalition gets a vote and absent a formal repeal, the legislation creating congestion pricing still binds.

In other words, Israel is a functioning multiparty parliamentary democracy, more or less. Mostly less these days, let’s be honest. But much of the “less” comes from a concerted attempt to politicize the civil service, which Regev is currently under investigation for. In the United States, it’s fully politicized; one governor can announce the cancellation of a legislatively mandated congestion pricing program on a whim, the MTA board (which she appointed) will affirm that she indeed can do it and will not sign a statement saying the state consents to congestion pricing, and the question of whether it’s legal will be deferred to courts where the judges were politically appointed based on governor-legislative chief deals. Israel can make long-term plans, and a minister like Regev can interfere with them, but would need to do a lot of work to truly wreck them. The United States, as we’re seeing with New York congestion pricing, really can’t.

Hochul Suspends Congestion Pricing

New York Governor Kathy Hochul just announced that she’s putting congestion pricing on pause. The plan had gone through years of political and regulatory hell and finally passed the state legislature earlier this year, to go into effect on June 30th, in 25 days. There was some political criticism of it, and lawsuits by New Jersey, but all the expectations were that it would go into effect on schedule. Today, without prior warning, Hochul announced that she’s looking to pause the program, and then confirmed it was on hold. The future of the program is uncertain; activists across the region are mobilizing for a last-ditch effort, as are suppliers like Alstom. The future of the required $1 billion a year in congestion pricing revenue is uncertain as well, and Hochul floated a plan to instead raise taxes on businesses, which is not at all popular and very unlikely to happen.

So last-minute is the announcement that, as Clayton Guse points out, the MTA has already contracted with a firm to provide the digital and physical infrastructure for toll collection, for $507 million. If congestion pricing is canceled as the governor plans, the contract will need to be rescinded, cementing the MTA’s reputation as a nightmare client that nobody should want to work with unless they get paid in advance and with a risk premium. Much of the hardware is already in place, hardly a sign of long-term commitment not to enact congestion pricing.

Area advocates are generally livid. As it is, there are questions about whether it’s even legal for Hochul to do so – technically, only the MTA board can decide this. But then the governor appoints the MTA board, and the appointments are political. Eric is even asking about federal funding for Second Avenue Subway, since the MTA is relying on congestion pricing for its future capital plans.

The one local activist I know who opposes congestion pricing says “I wish” and “they’ll restart it the day after November elections.” If it’s a play for low-trust voters who drive and think the additional revenue for the MTA, by law at least $1 billion a year, will all be wasted, it’s not helping. The political analysts I’m seeing from within the transit advocacy community are portraying it as an unforced error, making Hochul look incompetent and waffling, rather than boldly blocking something that’s adverse to key groups of voters.

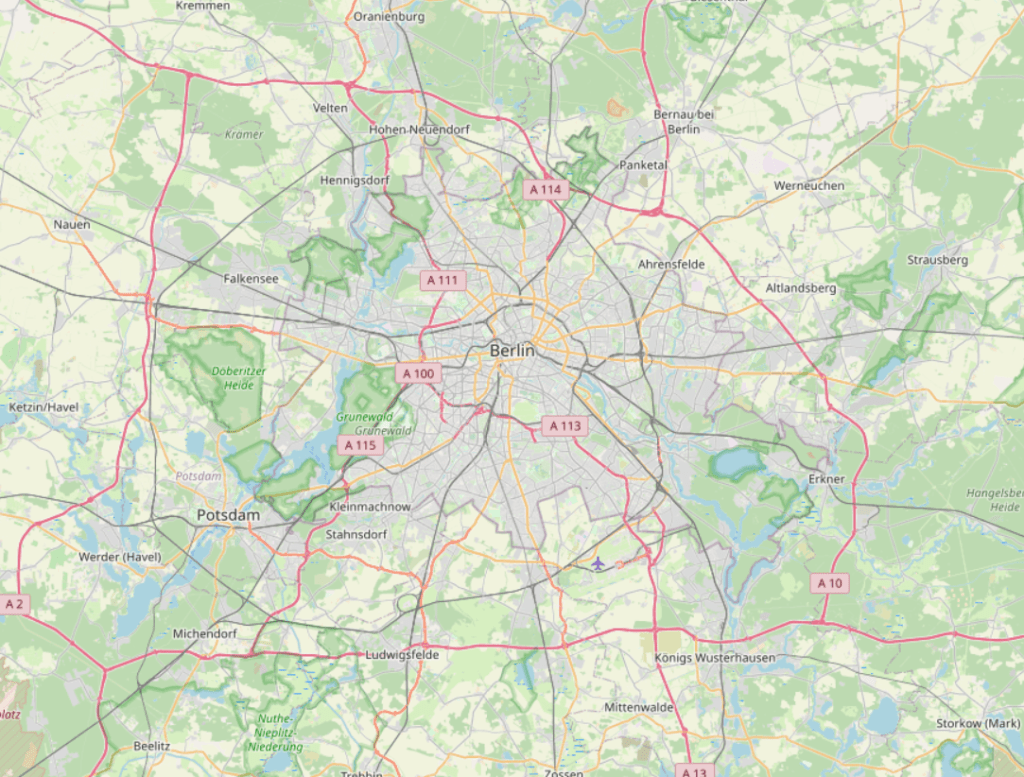

The issue here isn’t exactly that if Hochul sticks to her plan to cancel congestion pricing, there will not be congestion pricing in New York. Paris and Berlin don’t have congestion pricing either. In Paris, Anne Hidalgo is open about her antipathy to market-based solutions like congestion pricing, and prefers to reduce car traffic through taking away space from cars to give to public transportation, pedestrians, and cyclists. People who don’t like it are free to vote for more liberal (in the European sense) candidates. In Berlin, similarly, the Greens support congestion pricing (“City-Maut”), but the other parties on the left do not, and certainly not the pro-car parties on the right. If the Greens got more votes and had a stronger bargaining position in coalition negotiations, it might happen, and anyone who cares in either direction knows how to vote on this matter. In New York, there has never been such a political campaign. Rather, the machinations that led Hochul to do this, which people are speculating involve suburban representatives who feel politically vulnerable, have been entirely behind the scenes. There’s no transparency, and no commitment to providing people who are not political insiders with consistent policy that they can use to make personal, social, or business plans around.

Everything right now is speculation, precisely because there’s neither transparency nor certainty in state-level governance. Greg Shill is talking about this in the context of suburban members of the informal coalition of Democratic voters; but then it has to be informal, because were it formal, suburban politicians could have demanded and gotten disproportionately suburb-favoring public transit investments. Ben Kabak is saying that it was House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries who pressed Hochul for this; Jeffries himself said he supports the pause for further study (there was a 4,000 page study already).

The chaos of this process is what plays to the impression that the state can’t govern itself; Indignity mentions it alongside basic governance problems in the city and the state. This is how the governor is convincing anti-congestion pricing cynics that it will be back in November and pro-congestion pricing ones that it’s dead, the exact opposite of what she should be doing. Indecision is not popular with voters, and if Hochul doesn’t understand that, it makes it easy to understand why she won New York in 2022 by only 6.4%, a state that in a neutral environment like 2022 the Democrats usually win by 20%.

But it’s not about Hochul personally. Hochul is a piece of paper with “Democrat” written on it; the question is what process led to her elevation for governor, an office with dictatorial powers over policy as long as state agencies like the MTA are involved. This needs to be understood as the usual democratic deficit. Hochul acts like this because this signals to insiders that they are valued, as the only people capable of interpreting whatever is going on in state politics (or city politics – mayoral machinations are if anything worse). Transparency democratizes information, and what Hochul is doing right now does the exact opposite, in a game where everyone wins except the voters and the great majority of interests who are not political insiders.

The Future of Congestion Pricing in New York

New York just passed congestion pricing, to begin operation on June 30th. The magazine Vital City published an issue dedicated to this policy two days ago; among the articles about it is one by me, about public transportation investments. People should read the entire article; here I’d like to both give more context and discuss some of the other articles in the issue. Much of this comes from what I said to editor Josh Greenman when discussing the pitch for the piece, and how I interpret the other pieces in the same context. The most basic point, for me, is that what matters is if the overall quality of public transit in and around New York is seen to improve in the next 5-10 years. In particular, if congestion pricing is paired with one specific thing (such as a new subway line) and it improves but the rest of the system is seen to decline, then it will not help, and instead people will be cynical about government actions like this and come to oppose further programs and even call for repealing the congestion tax.

The other articles in the issue

There are 10 articles in this issue. One is my own. Another is by Josh, explaining the background to congestion pricing and setting up the other nine articles. The other eight were written by John Surico, Sam Schwartz, Becca Baird-Remba, Austin Celestin, Howard Yaruss, Nicole Gelinas, Vishaan Chakrabarti, and Henry Grabar, and I recommend that people read all of them, for different perspectives.

The general themes the nine of us have covered, not all equally, include,

- How to use congestion pricing to improve transportation alternatives (me on transit investment, Yaruss on transit fare cuts, Nicole and Chakrabarti on active transportation, Henry on removing parking to improve pedestrian safety).

- The unpopularity of congestion pricing and what it portends (Surico about polling, Becca about business group opposition, Schwartz on political risk, Yaruss again on why the fare cut is wise); of note, none of the authors are coming out against congestion pricing, just warning that it will need to deliver tangible benefits to remain popular, and Surico is making the point that in London and Stockholm, congestion pricing was unpopular until it took effect, after which it was popular enough that new center-right leadership did not repeal it.

- Environmental justice issues (Becca and Celestin): my article points out that traffic levels fell within the London congestion zone but not outside it, and Becca and Celestin both point out that the projections in New York are for traffic levels outside the zone not to improve and possibly to worsen, in particular in asthma-stricken Upper Manhattan and the Bronx, Celestin going more deeply into this point and correctly lamenting that not enough transit improvements are intended to go into these areas. The only things I can add to this are that for environmental justice, two good investment targets include a 125th Street subway tunnel extending Second Avenue Subway and battery-electric buses at depots to reduce pollution.

- Problems with toll evasion (Schwartz and Yaruss): there’s a growing trend of intentional defacement of license plates by the cars’ own drivers, to make them unreadable by traffic camera and avoid paying tolls, which could complicate revenue collection under congestion pricing.

The need for broad success

When discussing my article with Josh, before I wrote it, we talked about the idea of connecting congestion pricing to specific improvements. My lane would be specific transit improvements, like new lines, elevator access at existing stations, and so on, and similarly, Nicole, Henry, Chakrabarti, and Yaruss proposed their own points. But at the same time, it’s not possible to just make one thing work and say “this was funded by congestion pricing.” The entire system has to both be better and look better, the latter since visible revenue collection by the state like congestion pricing or new taxes are always on the chopping block for populist politicians if the state is too unpopular.

The example I gave Josh when we talked was the TGV. The TGV is a clear success as transportation; it is also, unlike congestion pricing, politically safe, in the sense that nobody seriously proposes eliminating it or slowing it down, and the only controversy is about the construction of new, financially marginal lines augmenting the core lilnes. However, the success of the TGV has not prevented populists and people who generally mistrust the state from claiming that things are actually bad; in France, they are often animated by New Left nostalgia for when they could ride slow, cheap trains everywhere, and since they were young then, the long trip times and wait times didn’t matter to them. Such nostalgics complain that regional trains, connecting city pairs where the train has not been competitive with cars since mass motorization and only survived so long as people were too poor to afford cars, are getting worse. Even though ridership in France is up, this specific use case (which by the 1980s was already moribund) is down, leading to mistrust. Unfortunately, while the TGV is politically safe in France, this corner case is used by German rail advocates to argue against the construction of a connected high-speed rail network here, as those corner case trains are better in Germany (while still not carrying much traffic).

The most important conclusion of the story of the TGV is that France needs to keep its high-speed system but adopt German operations, just as Germany needs to adopt French high-speed rail. But in the case of New York, the important lesson to extract is that if the MTA does one thing that I or Nicole or Henry or Chakrabarti or Yaruss called for while neglecting the broad system, people will not be happy. If the MTA builds subway lines with the projected $1 billion a year in revenue, politicians will say “this subway line has been built with congestion pricing revenue,” and then riders will see declines in reliability, frequency, speed, and cleanliness elsewhere and learn to be cynical of the state and oppose further support for the state’s transit operations.

The MTA could split the difference among what we propose. As I mentioned above, I find Celestin’s points about environmental justice compelling, and want to see improvements including new subways in at-risk areas, bus depot electrification to reduce pollution, and commuter rail improvements making it usable by city residents and not just suburbanites (Celestin mentions frequency; to that I’ll add fare integration). Nicole, Henry, and Chakrabarti are proposing street space reallocation, which doesn’t cost much money, but does cost political capital and requires the public to be broadly trusting of the state’s promises on transportation. The problem with doing an all-of-the-above program is that at the end of the day, projected congestion pricing revenue is $1 billion a year and the MTA capital program is $11 billion a year; the new revenue is secondary, and my usual bête noire, construction costs, is primary.

Trucking and Grocery Prices

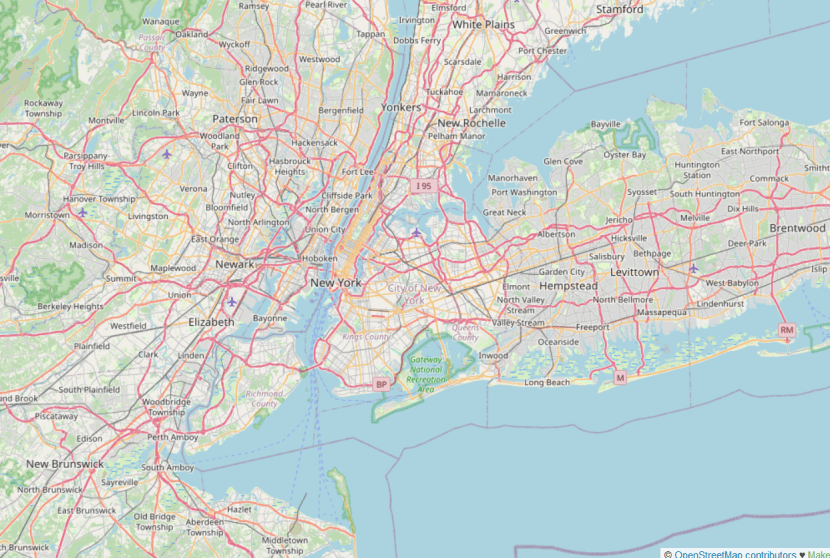

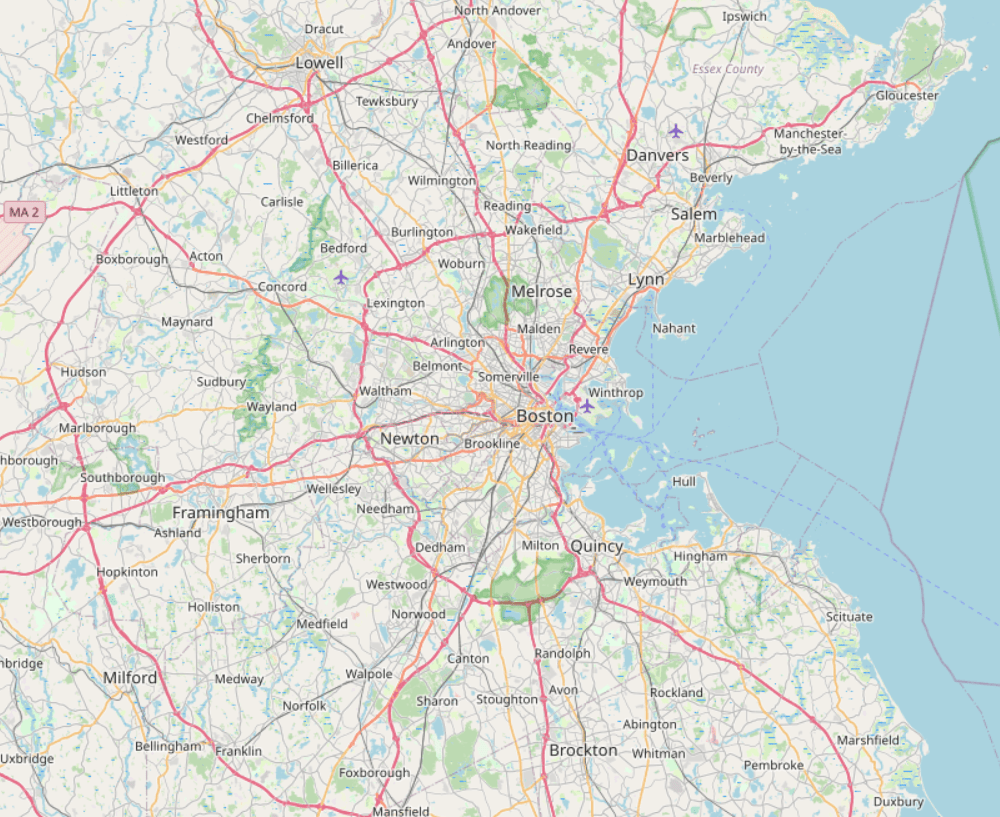

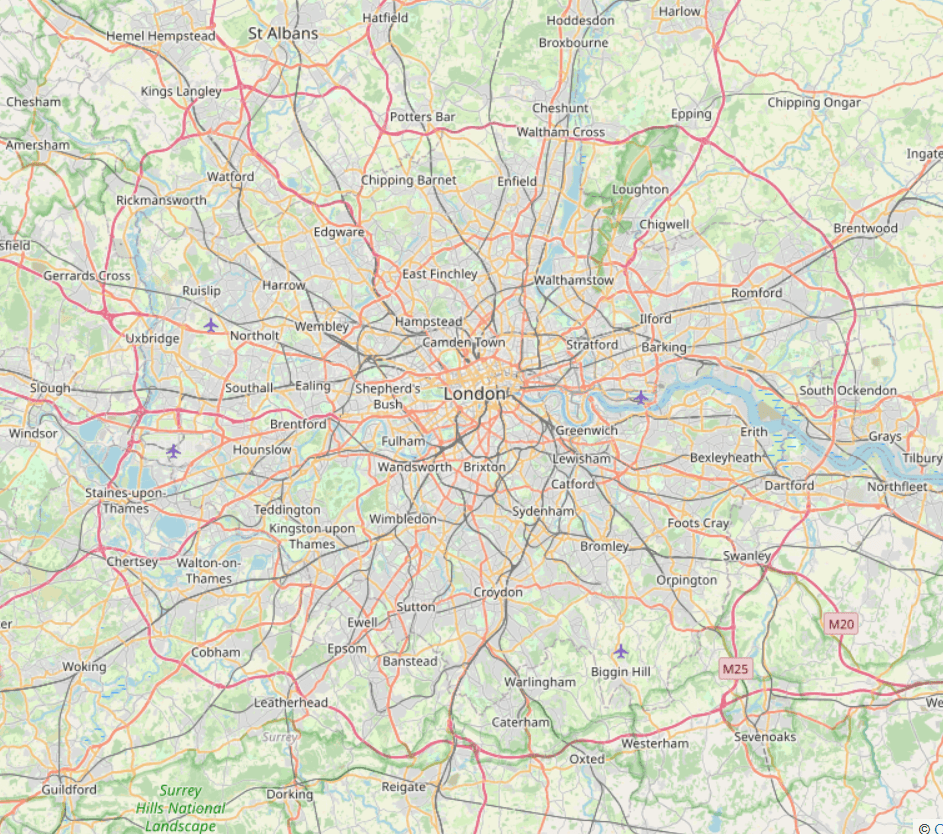

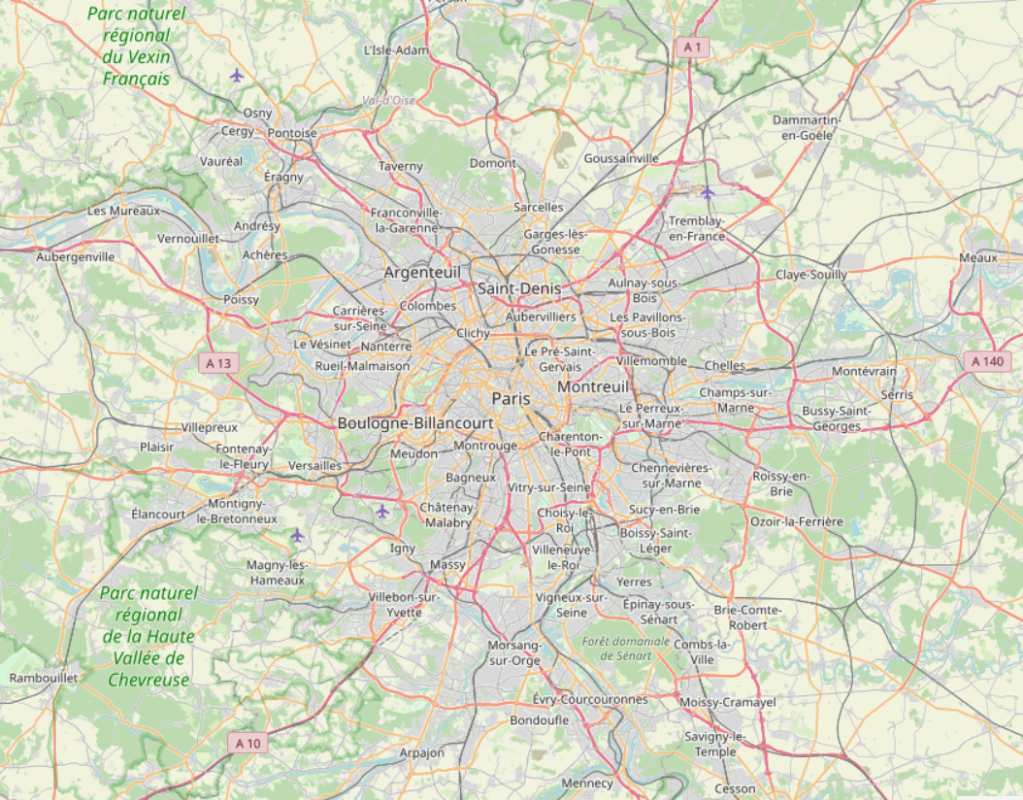

In dedication to people who argue in favor of urban motorways on the grounds that they’re necessary for truck access and cheap consumer goods, here are, at the same scale, the motorway networks of New York, London, Paris, and Berlin. While perusing these maps, note that grocery prices in New York are significantly higher than in its European counterparts. Boston is included as well, for an example of an American city with fewer inherent access issues coming from wide rivers with few bridges; grocery prices in Boston are lower than in New York but higher than in Paris and Berlin (I don’t remember how London compares).

The maps

The scale isn’t exactly the same – it’s all sampled from the same zoom level on OpenStreetMaps; New York is at 40° 45′ N and Berlin is at 52° 30′ N, so technically the Berlin map is at a 1.25 times closer zoom level than the New York map, and the others are in between. But it’s close. Motorways are in red; the Périphérique, delineating the boundary between Paris and its suburbs, is a full freeway, but is inconsistently depicted in red, since it gives right-of-way to entering over through-traffic, typical for regular roads but not of freeways, even though otherwise it is built to freeway standards.

Discussion

The Périphérique is at city limits; within it, 2.1 million people live, and 1.9 million work, representing 32% of Ile-de-France’s total as of 2020. There are no motorways within this zone; there were a few but they have been boulevardized under the mayoralty of Anne Hidalgo, and simultaneously, at-grade arterial roads have had lanes reduced to make room for bike lanes, sidewalk expansion, and pedestrian plazas. Berlin Greens love to negatively contrast the city with Paris, since Berlin is slowly expanding the A100 Autobahn counterclockwise along the Ring (in the above map, the Ring is in black; the under-construction 16th segment of A100 is from the place labeled A113 north to just short of the river), and is not narrowing boulevards to make room for bike lanes. But the A100 ring isn’t even complete, nor is there any plan to complete it; the controversial 17th segment is just a few kilometers across the river. On net, the Autobahn network here is smaller than in Ile-de-France, and looks similar in size per capita. London is even more under-freewayed – the M25 ring encloses nearly the entire city, population 8.8 million, and within it are only a handful of radial motorways, none penetrating into Central London.

The contrast with American cities is stark. New York is, by American standards, under-freewayed, legacy of early freeway revolts going back to the 1950s and the opposition to the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have connected the Holland Tunnel with the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges; see map here. There’s practically no penetration into Manhattan, just stub connections to the bridges and tunnels. But Manhattan is not 2.1 million people but 1.6 million – and we should probably subtract Washington Heights (200,000 people in CB 12) since it is crossed by a freeway or even all of Upper Manhattan (650,000 in CBs 9-12). Immediately outside Manhattan, there are ample freeways, crossing close-in neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, the South Bronx, and Jersey City. The city is not automobile-friendly, but it has considerably more car and truck capacity than its European counterparts. Boston, with a less anti-freeway history than New York, has penetration all the way to Downtown Boston, with the Central Artery, now the Big Dig, having all-controlled-access through-connections to points north, west, and south.

Grocery prices

Americans who defend the status quo of urban freeways keep asking about truck access; this played a role in the debate over what to do about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway’s Downtown Brooklyn section. Against shutting it down, some New Yorkers said, there is the issue of the heavy truck traffic, and where it would go. This then led to American triumphalism about how truck access is important for cheap groceries and other goods, to avoid urban traffic.

And that argument does not survive a trip to a New York (or other urban American) supermarket and another trip to a German or French one. German supermarkets are famously cheap, and have been entering the UK and US, where their greater efficiency in delivering goods has put pressure on local competitors. Walmart, as famously inexpensive as Aldi and Lidl (and generally unavailable in large cities), has had to lower prices to compete. Carrefour and Casino do not operate in the US or UK, and my impression of American urbanists is that they stereotype Carrefour as expensive because they associate it with their expensive French vacations, but outside cities they are French-speaking Walmarts, and even in Paris their prices, while higher, are not much higher than those of German chains in Germany and are much lower than anything available in New York.

While the UK has not given the world any discount retailer like Walmart, Carrefour, or Lidl, its own prices are distinctly lower than in the US, at least as far as the cities are concerned. UK wages are infamously lower than US wages these days, but the UK has such high interregional inequality that wages in London, where the comparison was made, are not too different from wages in New York, especially for people who are not working in tech or other high-wage fields (see national inequality numbers here). In Germany, where inequality is similar to that of the UK or a tad lower, and average wages are higher, I’ve seen Aldi advertise 20€/hour positions; the cookies and cottage cheese that I buy are 1€ per pack where a New York supermarket would charge maybe $3 for a comparable product.

Retail and freight

Retail is a labor-intensive industry. Its costs are dominated by the wages and benefits of the employees. Both the overall profit margins and the operating income per employee are low; increases in wages are visible in prices. If the delivery trucks get stuck in traffic, are charged a congestion tax, have restricted delivery hours, or otherwise have to deal with any of the consequences of urban anti-car policy, the impact on retail efficiency is low.

The connection between automobility and cheap retail is not that auto-oriented cities have an easier time providing cheap goods; Boston is rather auto-oriented by European standards and has expensive retail and the same is true of the other secondary transit cities of the United States. Rather, it’s that postwar innovations in retail efficiency have included, among other things, adapting to new mass motorization, through the invention of the hypermarket by Walmart and Carrefour. But the main innovation is not the car, but rather the idea of buying in bulk to reduce prices; Aldi achieves the same bulk buying with smaller stores, through using off-brand private labels. In the American context, Walmart and other discount retailers have with few exceptions not bothered providing urban-scale stores, because in a country with, as of 2019, a 90% car modal split and a 9% transit-and-active-transportation modal split for people not working from home, it’s more convenient to just ignore the small urban patches that have other transportation needs. In France and Germany, equally cheap discounters do go after the urban market – New York groceries are dominated by high-cost local and regional chains, Paris and Berlin ones are dominated by the same national chains that sell in periurban areas – and offer low-cost goods.

The upshot is that a city can engage in the same anti-car urban policies as Paris and not at all see this in retail prices. This is especially remarkable since Paris’s policies do not include congestion pricing – Hidalgo is of the opinion that rationing road space through prices is too neoliberal; normally, congestion pricing regimes remove cars used by commuters and marginal non-commute personal trips, whereas commercial traffic happily pays a few pounds to get there faster. Even with the sort of anti-car policies that disproportionately hurt commercial traffic more than congestion pricing, Paris has significantly cheaper retail than New York (or Boston, San Francisco, etc.).

And Berlin, for all of its urbanist cultural cringe toward Paris, needs to be classified alongside Paris and not alongside American cities. The city does not have a large motorway network, and its inner-urban neighborhoods are not fast drive-throughs. And yet in the center of the city, next to pedestrian plazas, retailers like Edeka and Kaufland charge 1€ for items that New York chains outside Manhattan sell for $2.5-4. Urban-scale retail deliveries are that unimportant to the retail industry.

The United States Has Too Few Road Tunnels

The Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore collapsed after a drifting freighter hit one of its supports; so far, six people are presumed dead. Immediately after the disaster, people were asking if it could be prevented, and it became clear that it is not possible to build a bridge anchor that can withstand the impact of a modern ship, even at low speed. However, it was then pointed out to me on Mastodon that it’s not normal in Europe to have such a bridge over a shipping channel; instead, roads go in tunnel. I started looking, and got to a place that connects my interest in construction costs with that of cross-cultural learning. Europe has far more road tunneling than the US does, thanks to the lower construction costs here; it also has better harmonization of regulations of what can go in tunnels and what cannot. The bridge collapse is a corner case of where the American system fails – it’s a once in several decades event – but it does showcase deep problems with building infrastructure.

Road tunnels

The United States has very little road tunneling for its size. This list has a lot of dead links and out of date numbers, but in the US, the FHWA has a current database in which the tunnels sum to 220 km. Germany had 150 km in 1999, and has tendered about 170 km of new tunnel since 2000 of which only 48 are still under construction. France has 238 km of road tunnel; the two longest and the 10th longest, totaling 28 km, cross the Alpine border with Italy, but even excluding those, 210 is almost as much as the US on one fifth the population. Italy of course has more tunneling, as can be expected from its topography, but France (ex-borders) and Germany are not more mountainous than the US, do not have fjords and skerries like Norway, and don’t even have rias like Chesapeake Bay and the Lower Hudson. Japan, with its mountainous island geography, has around 5,000 km of road tunnel.

The United States builds so few tunnels that it’s hard to create any large database of American road tunnels and their costs. Moreover, it has even fewer urban road tunnels, and the few it does have, like the Big Dig and more recently the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement tunnel, have become bywords for extreme costs, creating distaste even among pro-highway urban politicians for more and leading to project cancellations. With that in mind, the State Route 99 tunnel replacing the Alaskan Way Viaduct is 3 km long and cost $2.15 billion in 2009-19, which is $2.77 billion in 2023 dollars and $920 million/km, with just four lanes, two in each direction.

In Europe, this is not at all an exhaustive database; it represents where I’ve lived and what I’ve studied, but these are all complex urban tunnels in dense environments:

- Stockholm: the six-lane Förbifart Stockholm project to build long bypass roads in Stockholm using congestion pricing money, after acrimonious political debates over how to allocate the money between roads and public transport, comprises 17 km of tunnel (plus 4 km above-ground) including underwater segments, for an updated cost of 51.5 billion kronor in 2021 prices, or $6.97 billion in 2023 PPPs, or $410 million/km. The project is well underway and its current cost represents a large overrun over the original estimate.

- Paris: the four-lane A86 ring road was completed in 2011 with 15.5 km of new tunnel, including 10 in a duplex tunnel, at a cost of 2.2 billion €. I’ve seen sources saying that the cost applies only to the duplex section, but the EIB claims 1.7 billion € for the duplex. Physical construction was done 2005-7; deflating from 2006 prices, this is $4.18 billion in 2023 PPPs, or $270 million/km. This is a tunnel with atypically restricted clearances – commercial vehicles are entirely banned, as are vehicles running on compressed natural gas, due to fire concerns after the Mont-Blanc Tunnel fire.

- Berlin: the four-lane 2.4 km long Tunnel Tiergarten Spreebogen (TTS) project was dug 2002-4, for 390 million €, or $790 million in 2023 PPPs and $330 million/km. This tunnel goes under the river and under the contemporarily built Berlin Hauptbahnhof urban renewal but also under a park. The controversial A100 17th segment plan comprises 4.1 km of which 2.7 are to be in tunnel, officially for 800 million € but that estimate is out of date and a rougher but more current estimate is 1 billion €. The exchange rate value of the euro today belies how much stronger it is in PPP terms: this is $1.45 billion, or $537 million/km if we assume the above-ground section is free, somewhat less if we cost it too. The 17th segment tunnel is, I believe, to have six lanes; the under-construction 16th segment has six lanes.

Crossing shipping channels

The busiest container ports in Europe are, by far, Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, in this order. Rotterdam and Antwerp do not, as far as I’ve been able to tell from Google Earth tourism, have any road bridge over the shipping channels. Hamburg has one, the Köhlbrandbrücke (anchored on land, not water), on the way to one of the container berths, and some movable bridges like the Kattwykbrücke on the way to other berths – and there are plans to replace this with a new crossing, by bridge, with higher clearance below, with a tunnel elsewhere on the route. The next tranche of European ports are generally coastal – Le Havre, Bremerhaven, Valencia, Algeciras, Piraeus, Constanța – so it is not surprising the shipping channels are bridge-free; but Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, are all on rivers, crossed by tunnel.

American ports usually have bridges over shipping channels, even when they are next to the ocean, as at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. This is not universal – crossings in Hampton Roads have tunnels – but it’s the trend. Of note, the US does occasionally tunnel under deep channels (again, Hampton Roads); that the Netherlands tunnels in Rotterdam is especially remarkable given how Holland is a floodplain with very difficult tunnel construction in alluvial soil.

Hazardous material regulations

Tunnels do not permit all traffic, due to fire risk. For example, the Mont-Blanc Tunnel requires vehicles heavier than 3.5 tons to undergo a safety inspection before entering to ensure they don’t carry prohibited dangerous goods. In Europe, this is governed by the ADR; all European countries are party to it, even ones not in the EU, and so are some non-European ones. Tunnels can be classified locally between A (no restrictions) and E (most restrictive).

The United States is not party to the ADR. It has its own set of regulations for transportation of hazardous materials (hazmat), with different classifications – and those differ by state. Here are the rules in Maryland. They’re restrictive enough that significant road freight had to use the Key Bridge, because the alternative routes have tunnels that it is banned from entering. Port Authority has different rules, permitting certain hazmat through the Lincoln Tunnel with an official escort. Somehow, the rules are not uniform in the United States even though it is a country and Europe is not; Russia and Ukraine may be at war with each other, but they have the same transportation of dangerous goods regulations.

The Origins of Los Angeles’s Car Culture and Weak Center

On Twitter, Armand Domalewski asks why Los Angeles is so much more auto-oriented than his city, San Francisco. Matt Yglesias responds that it’s because Los Angeles does not have a strong city center and San Francisco does. I am fairly certain that Matt is channeling a post I wrote about the subject 4.5 years ago (and insight by transit advocates that I don’t remember the source of, to the effect that the modal split for Downtown Los Angeles workers is a healthy 50%), looking at employment in these two cities’ central business districts as well as other comparison cases. In addition, Matt gives extra examples of how Los Angeles is unique in having prestige industries located outside city center: the movie studios are famously in Hollywood and not Downtown, and to that I’ll add that when I looked at high-end hotel locations in 2012, Los Angeles’s were all over the region and most concentrated on the Westside, which isn’t true of other big American coastal cities, even atypically job-sprawling Philadelphia. Because of my connection to this question, I’d like to inject some nuance.

The upshot is that Los Angeles’s car culture is clearly connected to its weak center. I wouldn’t even call it polycentric. Rather, employment there sprawls to small places, rarely even rising to the level of a recognizable edge city like Century City. It is weakly-centered, and this favors cars over public transit – public transit lives off of high-capacity, high-frequency connections, favoring places with high population density (which Los Angeles has) and high job density (which it does not), while cars prefer the opposite because excessive density with cars leads to traffic jams. However, historically, best I can tell, the weak center and the cars co-evolved – I don’t think Los Angeles was atypically weakly-centered on the eve of mass motorization, and in fact every city for which I can find such information, even model transit cities, has gotten steadily job-sprawlier in the last few generations.

How is Los Angeles weakly centered?

There are a number of ways of measuring city center dominance. My metric is the share of metro area employment that is in the central 100 km^2; some gerrymandering and water-hopping is permitted, but the 100 km^2 blob should still be a recognizable central blob rather than many disconnected islands. This is not because this is the best metric, but because my information about France and Canada is less granular than for the United States, and 100 km^2 lets me compare American cities with Vancouver and with the combination of Paris and La Défense; my data on Tokyo is of comparable granularity to Paris and this lets me pick out Central Tokyo plus some adjacent wards like Shinjuku.

As a warning, the fixed size of the central blob means that the proportion should be degressive in city size, which I notice when I compare auto-centric American metro areas of different sizes. It should also be higher all things considered in the United States, where I draw blobs on OnTheMap to capture as many jobs as possible without the blob looking like it has tendrils, than in the foreign comparisons.

I gave many examples in a Twitter thread from 2019, though not Los Angeles. Doing the same exercise for Los Angeles with 2019 data gives 1.6 million jobs in a 500 km^2 blob stretching as far as Culver City, UCLA, Downtown Burbank, and Downtown Pasadena; a 100 km^2 blob gerrymandered to just include Hollywood, West Hollywood, and Century City, none of which can reasonably be called city center, is already down to 820,000, where the roughly same-area city of San Francisco is 770,000, and more like 900,000 when taking its central 50 km^2 plus those of Oakland and Berkeley. A circle of area 100 km^2 centered on Vermont/Wilshire to include all of Downtown plus Hollywood is down to 620,000. This compares with a total of 6.5 million jobs in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, and 8.3 million including Ventura County and the Inland Empire.

The upshot is that Downtown Los Angeles is pretty big, but not relative to the size of the metro area it’s in. On an honest definition of the central business district, it is smaller in absolute job count than Downtown San Francisco, Boston (which has around 830,000), Washington (around 700,000), or Chicago (1 million), let alone New York (around 3 million) or Paris (2 million in the city and the communes comprising La Défense).

Nor are the secondary centers in Los Angeles substantial enough to make it polycentric. Downtown Burbank has around 20,000 jobs, Downtown Glendale around 50,000, Downtown Pasadena including Caltech 67,000, Century City (included in the less honest central 100 km^2) 54,000, UCLA 74,000, El Segundo 55,000, LAX 48,000, Culver City around 20,000, Downtown Long Beach around 35,000. New York, in contrast, has Downtown Newark around 60,000, the Jersey City and Hoboken waterfront around 80,000, Long Island City around 100,000, Downtown Brooklyn around 100,000 as well, Flushing 45,000. Morningside Heights has 42,000 jobs in 1 km^2, a job density that I don’t think any of Los Angeles’s secondary centers hits, and the neighborhood is not at all a pure job center. No: Los Angeles just has a weak center.

I bring up Paris as a comparison because there’s a myth on both sides of the Atlantic, peddled by European critical urbanists who think tall buildings are immoral and by American tourists whose experience of Europe is entirely within walking distance of their city center hotels, that European city centers are less dominant than American ones. But Paris has, within the same area, comfortably more jobs than the centers of Los Angeles and Chicago combined; its central-100-km^2 job share is somewhat higher than New York’s (though probably only by enough to countermand the degressivity of this measure).

Was Los Angeles always like this?

I don’t think so. My knowledge of Los Angeles history is imperfect; the closest connection I have with it is that my partner is developing a narrative video game set in 1920s Hollywood, intended to be a realistic depiction of that era. But Los Angeles as I understand it was not especially polycentric, historically.

Historically polycentric regions exist, and tend to have weaker public transit than similar-size monocentric ones. The Ruhr has several centers, each with decent urban rail within the core city and high car usage elsewhere; Upper Silesia is far more auto-oriented than similar-size metropolitan Warsaw; Randstad has rather low urban rail ridership as people bike (in the main cities) or drive (in the suburbs). All three are truly historically polycentric, having developed as different city cores merged into one metro area as mechanized transportation raised people’s commute range, and in the case of the first two, much of this history involves different coal mining sites, each its own city.

Los Angeles doesn’t really have this history. The city had a slight majority of the county’s population in 1920 (577,000/936,000) and 1930 (1,238,000/2,208,000), only falling below half in the 1940s – and in the 1920s the city was already notable for its high use of cars. The other four counties in the metro area were more or less irrelevant then – in 1920 they totaled 244,000 people, rising to 389,000 by 1930, actually less than the city. Glendale grew from 14,000 to 63,000, Long Beach from 56,000 to 142,000, Santa Ana from 15,000 to 30,000; other suburbs that are now among the largest in the country either were insignificant (Anaheim had 11,000 people in 1930) or didn’t exist (Irvine had 10,000 people in 1970).

Los Angeles did annex San Fernando Valley early, but there wasn’t much urban development there in the 1920s; Burbank, entirely contained within that region, had 17,000 people in 1930, and San Fernando had 8,000. There was a lot of suburbanization in this period, but it did not predate car culture.

This is not at all how a polycentric region’s demographic history looks – in the Rhine-Ruhr, in 1900, Dortmund and both cities that would later merge to form Wuppertal had 150,000 people, Essen had just over 100,000 and would annex to over 200,000 within five years, Duisburg and Bochum both had just less than 100,000 and would soon cross that mark, Cologne had 370,000 people.

The region had an oil-based economy at the time – in the early 20th century the center of the American oil industry was still California and not Texas – but evidently, development centered on Los Angeles and to a small extent Long Beach (in 1930 having about the same ratio of population to Los Angeles’s that the combination of Jersey City and Newark did to New York’s). The same can be said of the various beach resorts that were booming in that era – the largest, Santa Monica, had 37,000 people in 1930, 3% of the population of Los Angeles, at which point Yonkers had 2% of New York’s population.

Boomtown infrastructure

While Los Angeles did not have a polycentric history in the 1920s, it did have a noted car culture. I believe that this is the result of boomtown dynamics, visible in many places that grow suddenly, like Detroit in the same era (in the 2010s, metro Detroit had a transit modal split of about 1%, the lowest among the largest American metro areas, even less than Dallas and Houston). Infrastructure takes time and coordination to build. In a growing region, infrastructure is always a little bit behind population growth, and in a boomtown, it is far behind – who knows if the boom will last? Texas is having this issue with flood control right now, and that’s with far less growth than that of Southern California in the first half of the 20th century.

The upshot is that in a very wealthy boomtown like 1920s Los Angeles (California ranking as the fourth richest state in 1929 and third richest in 1950), people have a lot of disposable income and not much public infrastructure. This leads to consumer spending – hence, cars. It takes long-term planning to convert such a city into a transit city, and this was not done in Los Angeles; plans to build a subway-surface tunnel for the Red Cars did not materialize, and the streetcars were not really competitive with cars on speed. Compounding the problems, the Red Cars were never profitable, in an era when public transit was expected to pay for itself; they were a loss leader for real estate development by owner Henry Huntington, and by the 1920s the land had already been sold at a profit.

Then came the war, and the same issue of private wealth without infrastructure loomed even more. California boomed during the war, thanks to war industries; there was new suburban development in areas with no streetcar service, with people carpooling to work or taking the bus as part of the national scheme to save fuel for the war effort. Transit maintenance was deferred throughout the country (as well as in Canada); after the war, Los Angeles had a massive population of people with very high disposable income, whose alternative to the car was either streetcars that were falling apart or buses that were even slower and had even worse ride quality.

Everywhere in the United States at the time, bustitution led to falling ridership per Ed Tennyson’s since-link-rotted TRB paper on the subject, even net of speed – Tennyson estimates based on postwar streetcar removal and later light rail construction that rail by itself gets 34-43% more ridership than bus service net of speed, and in both the bustitution and light rail eras the trains were also faster than the buses. But the older million-plus cities in the United States at the time had their subways to fall back on. Los Angeles had grown up too quickly and didn’t have one; neither did Detroit, which has a broadly Rust Belt economic and social history but a much more car-oriented transportation history.

The sort of long-term planning that produced transit revival did happen in the Western United States and Canada, elsewhere. In the 1970s, Western American and Canadian cities invented what is now standard light rail in both countries, often out of a deliberate desire not to be Los Angeles, at the time infamous for its smog; those cities have had more success with transit revival and transit-oriented development, especially Vancouver with its SkyTrain metro and aggressive high-rise residential and commercial transit-oriented development. But in the 1920s-40s, there was no such political counter to automobile dominance. Los Angeles did start building urban rail in the 1980s, but not at the necessary scale, and with ridiculously low levels of transit-oriented development: in the 2010s, after the economy recovered from the Great Recession, the 10 million strong county approved a hair more than 20,000 housing units annually, slightly less than the 2.5 million strong Metro Vancouver region.

Co-evolution of transportation and development

Los Angeles was not very decentralized in the first half of the 20th century. It had lower residential density, but none of today’s edge cities and smaller sub-centers really existed then, with only a handful of exceptions like Long Beach. By today’s standards, every American city was very centralized, with people generally working either in their home neighborhood or in city center. The city did have high car ownership for the era, and this encouraged freeway construction after the war, but the weak central business district came later.

Rather, what has happened since the war is a co-evolution of car-oriented transportation and weakly-centered job geography. Cars got stuck in traffic jams trying to get to city center, so business and local elites banded together to build an edge city closer to where management lived, first Miracle Mile and then Century City; Detroit similarly had New Center, where General Motors headquartered starting 1923. New York underwent the same process as businesses looked for excuses to move closer to the CEO’s home in the favored quarter (IBM in Armonk, General Electric in Fairfield), but the existence of the subway meant that there was still demand for ever more city center skyscrapers, even as city residents of means fled to the suburbs.

This story of co-evolution is not purely American. I keep going back to Paul Barter’s thesis, which portrays the urban layout in his example cities in East and Southeast Asia as starting from a similar point in the middle of the 20th century. Density was high throughout, and central sectors in Southeast Asia were ethnically segregated, with a Chinatown, an Indian area, a low-density Western colonial sector, and so on. The divergence happened in the second half of the 20th century, Singapore choosing to be a transit city and Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok choosing to be car-oriented cities. I don’t have job data for these cities, but my impression as a visitor (and former Singapore resident) is that Singapore has a clear central office district and Bangkok has a hodgepodge of skyscrapers with no real structure to where they go within the central areas.

So yes, Los Angeles’s weak center is making it difficult to expand public transportation there now and get high ridership out of it; boosting the region’s transit-oriented development rate to that of Vancouver would help, but Los Angeles is far more decentralized and auto-oriented than Vancouver was in the 1990s. But the historic sequence is not first polycentrism and then automobility, unlike in Upper Silesia or the Ruhr. Rather, a weak center (never true polycentricity) and automobility co-evolved, reinforcing each other to this day – it’s hard to get ridership out of urban rail expansions since city center is so weak, so people drive, so jobs locate where there’s less traffic and avoid Downtown Los Angeles.

Quick Note: New Jersey Highway Widening Alternatives

The Effective Transit Alliance just put out a proposal for how New Jersey can better spend the $10 billion that it is currently planning on spending on highway widening.

The highway widening in question is a simple project, and yet it costs $10.7 billion for around 13 km. I’m unaware of European road tunnels that are this expensive, and yet the widening is entirely above-ground. It’s not even good as a road project – it doesn’t resolve the real bottleneck across the Hudson, which requires rail anyway. It turns out that even at costs that New Jersey Transit thinks it can deliver, there’s a lot that can be done for $10.7 billion:

I contributed to this project, but not much, just some sanity checks on costs; other ETA members who I will credit on request did the heavy pulling of coming up with a good project list and prioritizing them even at New Jersey costs, which are a large multiple of normal costs for rail as well as for highways. I encourage everyone to read and share the full report, linked above; we worked on it in conjunction with some other New Jersey environmental organizations, which supplied some priorities for things we are less familiar with than public transit technicalities like bike lane priorities.