Category: Providence

Curves in Fast Zones

I wrote nearly five years ago that the lowest-hanging fruit for speeding up trains are in the slowest sections. This remains true, but as I (and Devin Wilkins) turn crayon into a real proposal, it’s clear what the second-lowest hanging fruit is: curves in otherwise fast sections. Fixing such curves sometimes saves more than a minute each, for costs that are not usually onerous.

The reason for this is that curves in fast zones tend to occur on a particular kind of legacy line. The line was built to high standards in mostly flat terrain, and therefore has long straight sections, or sections with atypically gentle curves. Between these sections the curves were fast for the time; in the United States, high standards for the 19th century meant curves of radius 1,746 meters, at which point each 100′ (30.48 meters) of track distance correspond to one degree of change in azimuth; 30.48*180/pi = 1,746.38. For much more information about speed zones, read this post from four weeks ago first; I’m going to mention some terminology from there without further definitions.

These curves are never good enough for high-speed rail. The Tokaido Shinkansen was built with 2,500 meter curves, and requires exceptional superelevation and a moderate degree of tilting (called active suspension) to reach 285 km/h. This lateral acceleration, 2.5 m/s^2, can’t really be achieved on ordinary high-speed rolling stock, and the options for it always incur higher acquisition and operating costs, or buying sole-sourced Japanese technology at much higher prices than are available to Japan Railways. In practice, the highest number that can be acheived with multi-vendor technology is around 2.07 m/s^2, or at lower speed around 2.2; 1,746*2.07 = 3,614.22, which corresponds to 60.12 m/s, or 216 km/h.

If a single such curve appears between two long, straight sections, then the slowdown penalty for it is 23.6 seconds from a top speed of 300 km/h, 35.5 from a top speed of 320 km/h, or 67 seconds from a top speed of 360 km/h. The curve itself is not instantaneous but has a few seconds of cruising at the lower speed, and this adds a few seconds of penalty as well.

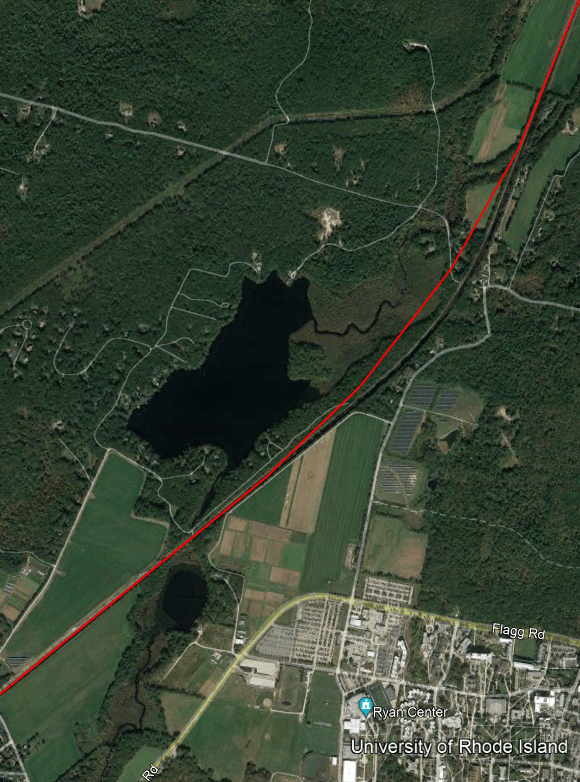

Case in point: the curve between Kingston and Wickford Junction in South County, Rhode Island is such a curve. The red line below denotes a 4 km radius curve, good for a little more than 320 km/h (360 with tilt), deviating from the black line of the existing curve.

The length of the existing curve is about 1.3 km, so to the above penalties, add 6 seconds if the top speed is 300 km/h, 7 if it’s 320, or 8.7 if it’s 360 (in which case the curve needs to be a bit wider unless tilting is used). If it’s not possible to build a wider curve than this, then from a top speed of 360 km/h, the 320 km/h slowdown adds 10 seconds of travel time, including a small penalty for the 1.3 km of the curve and a larger one for acceleration and deceleration; thus, widening the curve from the existing one to 4 km radius actually has a larger effect if the top speed on both sides is intended to be 360 and not 320 km/h.

The inside of this curve is not very developed. This is just about the lowest-density part of the Northeast Corridor. I-95 has four rather than six lanes here. Land acquisition for curve easement is considerably easier than in higher-density sprawl in New Jersey or Connecticut west of New Haven.

The same situation occurs north of Providence, on the Providence Line. There’s a succession of these 1,746 meter curves, sometimes slightly tighter, between Mansfield and Canton. The Canton Viaduct curve is unfixable, but the curves farther to the south are at-grade, with little in the way; there are five or six such curves (the sixth is just south of the viaduct and therefore less relevant) and fixing all of them together would save intercity trains around 1:15.

For context, 1.3 km of at-grade construction in South County with minimal land acquisition should not cost more than $50 million, even with the need to stage construction so that the new alignment can be rapidly connected to the old one during the switchover. Saving more than a minute for $50 million, or even saving 42 seconds for $50 million, is around 1.5 orders of magnitude more cost-effective than the Frederick Douglass Tunnel in Baltimore ($6 billion for 2.5 minutes); there aren’t a lot of places where it’s possible to save so much time at this little cost.

It creates a weird situation in which while the best place to invest in physical infrastructure is near urban stations to allow trains to approach at 50-80 km/h and not 15-25, the next best is to relieve 210 km/h speed zones that should be 300 km/h or more. It’s the curvy sections with long stretches of 120-160 km/h that are usually more difficult to fix.

How High-Speed and Regional Rail are Intertwined

The Transit Costs Project will wrap up soon with the report on construction cost differences, and we’re already looking at a report on high-speed rail. This post should be read as some early scoping on how this can be designed for the Northeast Corridor. In particular, integration of planning with regional rail is obligatory due to the extensive track sharing at both ends of the corridor as well as in the middle. This means that the project has to include some vision of what regional rail should look like in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. This vision is not a full crayon, but should have different options for different likely investment levels and how they fit into an intercity vision, within the existing budget, which is tens of billions thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework.

Boston

In Boston, commuter rail and intercity rail interact via the Providence Line, which is double-track. The Providence Line shares the same trunk line into Boston with the Franklin Line and the Stoughton Line, and eventually with South Coast Rail services.

The good news is that the MBTA is seriously looking at electrifying the trains to a substantial if insufficient extent. The Providence Line is already wired, except for a few siding and yard tracks, and the MBTA is currently planning to complete electrification and purchase EMUs on the main line, and possibly also on the Stoughton Line; South Coast Rail is required to be electrified when it is connected to this system anyway, for environmental reasons. If there is no further electrification, then it signals severe incompetence in Massachusetts but is still workable to a large extent.

Options for scheduling depend on how much further the state invests. The timetables I’ve written in the past (for an aggressive example, see here) assume electrification of everything that needs to be electrified but no North-South Rail Link tunnel. An NSRL timetable requires planning high-speed rail in conjunction with the entirety of the regional rail system; this is true even though intercity trains should terminate on the surface and not use the NSRL tunnel.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia is the easiest case. Trenton-Philadelphia is four-track, and has sufficiently little commuter traffic that the commuter trains can be put on the local tracks permanently. In the presence of high-speed rail, there is no need for express commuter trains – passengers can buy standing tickets on Trenton-Philadelphia, and those are not going to create a capacity crunch because train volumes need to be sized for the larger peak market into New York anyway.

On the Wilmington side, the outer end of the line is only triple-track. But it’s a short segment, largely peripheral to the network – the line is four-track from Philadelphia almost all the way to Wilmington, and beyond Wilmington ridership is very low. Moreover, Wilmington itself is so slow that it may be valuable to bypass it roughly along I-95 anyway.

The railway junctions are a more serious interface. Zoo Interlocking controls everything heading into Philadelphia from points north, and needs some facelifts (mainly, more modern turnouts) speeding up trains of all classes. Thankfully, there is no regional-intercity rail conflict here.

Washington

In some ways, the Washington-Baltimore Penn Line is a lot like the Boston-Providence line. It connects two historic city centers, but one is much larger than the other and so commuter demand is asymmetric. It has a tail behind the secondary city with very low ridership. It runs diesel under catenary, thanks to MARC’s recent choice to deelectrify service (it used to run electric locomotives).

But the Penn Line has significant sections of triple- and quad-track, courtesy of a bad investment plan that adds tracks without any schedule coordination. The quad-track segment can be used to simplify the interface; the triple-track segment, consisting of most of the line’s length, is unfortunately not useful for a symmetric timetable and requires some strategic quad-track overtakes. The Penn Line must be reelectrified, with high-performance EMUs minimizing the speed difference between regional and intercity trains. There are only five stations on the double- and triple-track narrows – BWI, Odenton, Bowie State, Seabrook, New Carrollton – and even figuring differences in average speed, this looks like a trip time difference between 160 km/h regional rail and 360 km/h HSR of about 15 minutes, which is doable with a single overtake.

New York

New York is the real pain point. Unlike in Boston and Washington, it’s difficult to isolate different parts of the commuter rail network from one another. Boston can more or less treat the Worcester, Providence+Stoughton, Fairmount, and Old Colony Lines as four different, non-interacting systems, and then slot Franklin into either Providence or Fairmount, whichever it prefers. New York can, with current and under-construction infrastructure, plausibly separate out some LIRR lines, but this is the part of the system with the least interaction with intercity rail.

Gateway could make things easier, but it would require consciously treating it as total separation between the Northeast Corridor and Morris and Essex systems, which would be a big mismatch in demand. (NEC demand is around twice M&E demand, but intercity trains would be sharing tracks with the NEC commuter trains, not the M&E ones; improving urban commuter rail service reduces this mismatch by loading the trains more within Newark but does not eliminate it.)

It’s so intertwined that the schedules have to be done de novo on both systems – intercity and regional – combined. This isn’t as in Boston and Washington, where the entire timetable can be done to fit one or two overtakes. This isn’t impossible – there are big gains to be had from train speedups all over and there. But it requires cutting-edge systems for timetabling and a lot of infrastructure investment, often in places that were left for later on official plans.

Intercity Rail Routes into Boston

People I respect are asking me about alternative routes for intercity trains into Boston. So let me explain why everything going into the city from points south should run to South Station via Providence and not via alternative inland routes such as Worcester or a new carved-up route via Woonsocket.

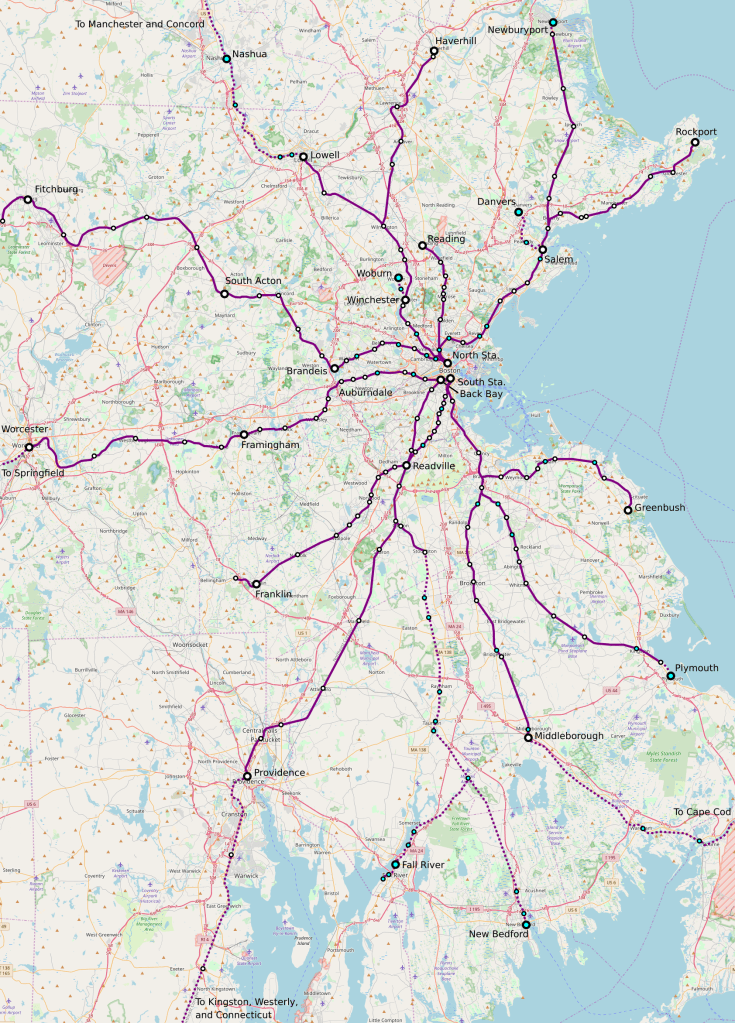

As an explanation, here is a map of the region’s commuter rail network; additional stations we’re proposing for regional rail are in turquoise, and new line segments are dashed.

Observe that the Providence Line, the route currently used by all intercity trains except the daily Lake Shore Limited, is pretty straight – most of it is good for 300+ km/h as far as track geometry goes. The Canton Viaduct near that Canton Junction station is a 1,746 meter radius curve, good for 237 km/h with active suspension or 216 km/h with the best non-tilting European practice. This straightness continues into Rhode Island, separated by a handful of curves that are to some extent fixable through Pawtucket. The fastest segment of the Acela train today is there, in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

The Worcester Line is visibly a lot curvier. Only two segments allow 160 km/h running in our regional rail schedules, around Westborough and immediately west of Grafton. This is why, ignoring intercity rail, our timetables have Boston-Providence trains taking 47 minutes where Boston-Worcester express trains take 45 minutes with 4 fewer stops or 57 minutes with 5 more, over the same route length. And the higher the necessary top speed, the larger the trip time mismatch is due to curves.

Going around the curves of the Worcester Line is possible, if high-speed rail gets a bypass next to I-90. However, this introduces three problems:

- More construction is needed, on the order of 210 km between Auburndale and New Haven compared with only 120 between Kingston and New Haven.

- Bypass tracks can’t serve the built-up area of Worcester, since I-90 passes well to its south. A peripheral station is possible but requires an extension of the commuter rail network to work well. Springfield and Hartford are both easy to serve at city center, but if only those two centers are servable, this throws away the advantage of the inland route over Providence in connecting to more medium-size intermediate cities.

- The two-track section through Newton remains the stuff of nightmares. There is no room to widen the right-of-way, and yet it is a buys section of the line, where it is barely possible to fit express regional rail alongside local trains, let alone intercity trains. Fast intercity trains would require a long tunnel, or demolition of two freeway lanes.

There’s the occasional plan to run intercity rail via the Worcester Line anyway. This is usually justified on grounds of resiliency (i.e. building too much infrastructure and running it unreliably), or price discrimination (charging less for lower-speed, higher-cost trains), or sheer crayoning (a stop in Springfield, without any integration with the rest of the system). All of these justifications are excuses; regional trains connecting Boston with Springfield and Springfield with New Haven are great, but the intercity corridor should, at all levels of investment, remain the Northeast Corridor, via Providence.

The issue is that, even without high-speed rail, the capacity and high track quality are on Providence. Then, as investment levels increase, it’s always easier to upgrade that route. The 120 km of high-speed bypass between New Haven and Kingston cost around $3-3.5 billion at latter-day European costs, save around 25 minutes relative to best practice, and open the door to more frequent regional service between New Haven and Kingston on the legacy Shore Line alongside high-speed intercity rail on the bypass. This is organizationally easy spending – not much coordination is required with other railroads, unlike the situation between New Haven and Wilmington with continuous track sharing with commuter lines.

If more capacity is required, adding strategic bypasses to the Providence Line is organizationally on the easy side for intercity-commuter rail track sharing (the Boston network is a simple diagram without too much weird branching). There’s a bypass at Attleboro today; without further bypasses, intercity trains can do Boston-Attleboro in 11 fewer minutes than regional trains if both classes run every 15 minutes, which work out to 25 minutes per our schedule and around 32 between Boston and Providence. To run intercity trains faster, in around 22 minutes, a second bypass is needed, in the Route 128-Readville area, but that is constructible at limited cost. If trains are desired more than very 15 minutes, then a) further four-tracking is feasible, and b) an intercity railroad that fills a full-length train every 15 minutes prints money and can afford to invest more.

This system of investment doesn’t work via the inland route. It’s too curvy, and the bypasses required to make it work are longer and more complex to build due to the hilly terrain. Then there’s the world-of-pain segment through Newton; in contrast, the New Haven-Kingston bypass can be built zero-tunnel. But that’s fine! The Northeast Corridor’s plenty upgradable, the inland route is bad for long-distance traffic (again, regional traffic is fine) but thankfully unnecessary.

Austerity is Inefficient

Working on an emergency timetable for regional rail has made it clear how an environment of austerity requires tradeoffs that reduce efficiency. I already talked about how the Swiss electronics before concrete slogan is not about not spending money but about spending a fixed amount of money intelligently; but now I have a concrete example for how optimizing organization runs into difficulties when there is no investment in either electronics or concrete. It’s still possible to create value out of such a system, but there will be seams, and fixing the seams requires some money.

Boston regional rail

The background to the Boston regional rail schedule is that corona destroyed ridership. In December of 2020, the counts showed ridership was down by about an order of magnitude over pre-crisis levels. American commuter rail is largely a vehicle for suburban white-collar commuters who work in city center 9 to 5; the busiest line in the Boston area, the Providence Line, ran 4 trains per hour at rush hour in the peak direction but had 2- and 2.5-hour service gaps in the reverse-peak and in midday and on weekends. Right now, the system is on a reduced emergency timetable, generally with 2-hour intervals, and the trains are empty.

But as Americans get vaccinated there are plans to restore some service. How much service is to run is up in the air, as is how it’s to be structured. Those plans may include flattening the peak and going to a clockface schedule, aiming to start moving the system away from traditional peak-focused timetables toward all-day service, albeit not at amazing frequency due to budget limits.

The plan I’ve been involved with is to figure out how to give most lines hourly service; a few low-ridership lines may be pruned, and the innermost lines, like Fairmount, get extra service, getting more frequency than they had before. The reasoning is that the frequency that counts as freedom is inversely proportional to trip length – shorter trips need more frequency and shorter headways, so even in an environment of austerity, the Fairmount Line should get a train every 15 or 20 minutes.

Optimization

In an environment of austerity, every resource counts. We were discussing individual trains, trying to figure out what the best use for the 30th, the 35th, the 40th trainset to run in regular service is. In all cases, the point is to maximize the time a train spends moving and minimize the time it spends collecting dust at a terminal. However, this leads to conflict among the following competing constraints:

- At outer terminals like Worcester and Lowell, it is desirable that the train should have a timed transfer with the local buses.

- At the inner terminals, that is South and North Stations, it is desirable that all trains arrive and depart around the same time (“pulse“), to facilitate diagonal transfers, such as from Fitchburg to Salem or from Worcester to Brockton.

- Some lines have long single-track segments; the most frustrating is the Worcester Line, which is in theory double-track the entire way but in practice single-track through Newton, where only the nominally-westbound track has platforms.

- The lines should run hourly, so ideally the one-way trip time should be 50 minutes or possibly 80 minutes, with a 10-minute turnaround.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to satisfy all constraints at once. In an environment with some avenues for investment, it’s possible to double-track single-track bottlenecks, as the MBTA is already planning to do for Newton in the medium run. It’s also possible to speed up lines on the “run as fast as necessary” principle to ensure the trips between knots take an integer or half-integer multiple of the headway; in our higher-investment regional rail plan for Worcester, this is the case, and all transfers and overtakes are tight. However, in a no-investment environment, something has to give. The Worcester Line is 90 minutes end-to-end all-local, and the single-track section is between around 15 and 30 minutes out of South Station, which means it is not possible to conveniently pulse either at South Station with the other commuter lines or at Worcester with the buses. But thankfully, the length of the single-track segment between the crossovers is just barely enough to allow bidirectional local service every 30 minutes.

Discussion

No-investment and low-investment plans are great for highlighting what the most pressing investment needs are. In general Boston needs electrification and high platforms everywhere, as do all other North American commuter lines; it is unfortunate that not a single system has both everywhere, as SEPTA is the only all-electric system and the LIRR (and sort of Metro-North) is the only all-high-platform system. However, more specifically, there are valuable targets for early investment, based on where the seams in the system are.

In the case of integrated timetabling, it’s really useful to be able to make strategic investments, including sometimes in concrete. They should always be based on a publicly-communicated target timetable, in which all the operational constraints are optimized and resolved for the maximum benefit of passengers. For example, in the TransitMatters Regional Rail plan, the timed transfers at the Boston end are dealt with by increasing frequency on the trunk lines to every 15 minutes, at which point the average untimed transfer is about as good as a timed hourly transfer in a 10-minute turnaround; this is based on expected ridership growth as higher frequency and the increase in speed from electrification and high platforms both reduce door-to-door trip times.

The upshot is that austerity is not good for efficiency. Cutting to grow is difficult, because there are always little seams that require money to fix, even at agencies where overall spending is too high rather than too low. Sometimes the timetables are such that a speedup really is needed: Switzerland’s maxim on speed is to run as fast as necessary, not as fast as trains ran 50 years ago with no further improvement. This in turn requires investment – investment that regularly happens when public transportation is run well enough to command public trust.

Quick Note: Timed Orbital Buses

Outside a city core with very high frequency of transit, say 8 minutes or better, bus and train services must be timetabled to meet each other with short connections as far as possible. Normally, this is done through setting up nodes at major suburban centers where trains and buses can all interchange. For example, see this post from six months ago about the TransitMatters proposal for trains between Boston and Worcester: on the hour every half hour, trains in both directions serve Framingham, which is the center for a small suburban bus system, and the buses should likewise run every half hour and meet with the trains in both directions.

This is a dendritic system, in which there is a clear hierarchy not just of buses and trains, but also of bus stops and train stations. Under the above system, every part of the Framingham area is connected by bus to the Framingham train station, and Framingham is then connected to the rest of Eastern New England via Downtown Boston. This is the easiest way to set up timed rail-bus connections: each individual rail line is planned around takt and symmetry such that the most important nodes can have easy timed bus connections, and then the buses are planned around the distinguished nodes.

However, there’s another way of doing this: a bus can connect two distinct nodes, on two different lines. The map I drew for a New England high- and low-speed rail has an orbital railroad doing this, connecting Providence, Worcester, and Fitchburg. Providence, as the second largest city center in New England, supplies such rail connections, including also a line going east toward Fall River and New Bedford, not depicted on the map as it requires extensive new construction in Downtown Providence, East Providence, and points east. But more commonly, a connection between two smaller nodes than Providence would be by bus.

The orbital bus is not easy to plan. It has to have timed connections at both ends, which imposes operational constraints on two distinct regional rail lines. To constrain planning even further, the bus itself has to work with its own takt – if it runs every half hour, it had better take an integer multiple of 15 minutes minus a short turnaround time to connect the two nodes.

It is also not common for two suburban stations on two distinct lines to lie on the same arterial road, at the correct distance from each other. For example, South Attleboro and Valley Falls are at a decent distance, if on the short side, but the route between them is circuitous and it would be far easier to try to set up a reverse-direction timed transfer at Central Falls for an all-rail route. The ideal distance for a 15-minute route is around 5-6 km; bus speeds in suburbia are fairly high when the buses run in straight lines, and if the density is so high that 5-6 km is too long for 15 minutes, then there’s probably enough density for much higher frequency than every half hour.

The upshot is that connections between two nodes are valuable, especially for people in the middle who then get easy service to two different rail lines, but uncommon. Brockton supplies a few, going west to Stoughton and east to Whitman and Abington. But the route to Stoughton is at 8.5 km a bit too long for 15 minutes – perhaps turning it into a 30-minute route, either with slightly longer connections or with a detour to Westgate (which the buses already take today), would be the most efficient. The routes to Whitman and Abington are 7 km long, which is feasible at the low density in between, but then timetabling the trains to set up knots at both Brockton and Abington/Whitman is not easy; Brockton is an easy node, but then since the Plymouth and Middleborough Lines are branches of the same system, their schedules are intertwined, and if Abington and Whitman are served 15 minutes away from Brockton then schedule constraints elsewhere lengthen turnaround times and require one additional trainset than if they are not nodes and buses can’t have timed connections at both ends.

Planners then have to keep looking for such orbital bus opportunities. There aren’t many, and there are many near-misses, but when they exist, they’re useful at creating an everywhere-to-everywhere network. It is even valuable to plan the trains accordingly provided other constraints are not violated, such as the above issue of the turnaround times on the Old Colony Lines.

Some Notes About Northeast Corridor High-Speed Rail

I want to follow up on what I wrote about speed zones a week ago. The starting point is that I have a version 0 map on Google Earth, which is far from the best CAD system out there, one that realizes the following timetable:

| Boston | 0:00 |

| Providence | 0:23 |

| New Haven | 1:00 |

| New York | 1:40 |

| Newark | 1:51 |

| Philadelphia | 2:24 |

| Wilmington | 2:37 |

| Baltimore | 3:03 |

| Washington | 3:19 |

This is inclusive of schedule contingency, set at 7% on segments with heavy track sharing with regional rail, like New York-New Haven, and 4% on segment with little to no track haring, like New Haven-Providence. The purpose of this post is to go over some delicate future-proofing that this may entail, especially given that the cost of doing so is much lower than the agency officials and thinktank planners who make glossy proposals think it should.

What does this entail?

The infrastructure required for this line to be operational is obtrusive, but for the most part not particularly complex. I talked years ago about the I-95 route between New Haven and southern Rhode Island, the longest stretch of new track, 120 km long. It has some challenging river crossings, especially that of the Quinnipiac in New Haven, but a freeway bridge along the same alignment opened in 2015 at a cost of $500 million, and that’s a 10-lane bridge 55 meters wide, not a 2-track rail bridge 10 meters wide. Without any tunnels on the route, New Haven-Kingston should cost no more than about $3-3.5 billion in 2020 terms.

Elsewhere, there are small curve easements, even on generally straight portions like in New Jersey and South County, Rhode Island, both of which have curves that if you zoom in close enough and play with the Google Earth circle tool you’ll see are much tighter than 4 km in radius. For the most part this just means building the required structure, and then connecting the tracks to the new rather than old curve in a night’s heavy work; more complex movements of track have been done in Japan on commuter railroads, in a more constrained environment.

There’s a fair amount of taking required. The most difficult segment is New Rochelle-New Haven, with the most takings in Darien and the only tunneling in Bridgeport; the only other new tunnel required is in Baltimore, where it should follow the old Great Circle Tunnel proposal’s scope, not the four-track double-stack mechanically ventilated bundle the project turned into. The Baltimore tunnel was estimated at $750 million in 2008, maybe $1 billion today, and that’s high for a tunnel without stations – it’s almost as high per kilometer as Second Avenue Subway without stations. Bridgeport requires about 4 km of tunnel with a short water crossing, so figure $1-1.5 billion today even taking the underwater penalty and the insane unit costs of the New York region as a given.

A few other smaller deviations from the mainline are worth doing at-grade or elevated: a cutoff in Maryland near the Delaware border in the middle of what could be prime 360 km/h territory, a cutoff in Port Chester and Greenwich bypassing the worst curve on the Northeast Corridor outside major cities, the aforementioned takings-heavy segment through Darien continuing along I-95 in Norwalk and Westport, a short bypass of curves around Fairfield Station. These should cost a few hundred million dollars each, though the Darien-Westport bypass, about 15 km long, could go over $1 billion.

Finally, the variable-tension catenary south of New York needs to be replaced with constant-tension catenary. A small portion of the line, between New Brunswick and Trenton, is being so replaced at elevated cost. I don’t know why the cost is so high – constant-tension catenary is standard around the world and costs $1.5-2.5 million per km in countries other than the US, Canada, and the UK. The Northeast Corridor is four-track and my other examples are two-track, but then my other examples also include transformers and not just wires; in New Zealand, the cost of wires alone was around $800,000 per km. Even taking inflation and four tracks into account, this should be maybe $700 million between New York and Washington, working overnight to avoid disturbing daytime traffic.

The overall cost should be around $15 billion, with rolling stock and overheads. Higher costs reflect unnecessary scope, such as extra regional rail capacity in New York, four-tracking the entire Providence Line instead of building strategic overtakes and scheduling trains intelligently, the aforementioned four-track version of the Baltimore tunnel, etc.

The implications of cheap high-speed rail

I wrote about high-speed rail ridership in the context of Metcalfe’s law, making the point that once one line exists, extensions are very high-value as a short construction segment generates longer and more profitable trips. The cost estimate I gave for the Northeast Corridor is $13 billion, the difference with $15 billion being rolling stock, which in that post I bundled into operating costs. With that estimate, the line profits $1.7 billion a year, a 13% financial return. This incentivizes building more lines to take advantage of network effects: New Haven-Springfield, Philadelphia-Pittsburgh, Washington-Virginia-North Carolina-Atlanta, New York-Upstate.

The problem: building extensions does require the infrastructure on the Northeast Corridor that I don’t think should be in the initial scope. Boston-Washington is good for around a 16-car train every 15 minutes all day, which is very intense by global standards but can still fit in the existing infrastructure where it is two-track. Even 10-minute service can sometimes fit on two tracks, for example having some high-speed trains stop at Trenton to cannibalize commuter rail traffic – but not always. Boston-Providence every 10 minutes requires extensive four-tracking, at least from Attleboro to beyond Sharon in addition to an overtake from Route 128 to Readville, the latter needed also for 15-minute service.

More fundamentally, once high-speed rail traffic grows beyond about 6 trains per hour, the value of a dedicated path through New York grows. This is not a cheap path – it means another Hudson tunnel, and a connection east to bypass the curves of the Hell Gate Bridge, which means 8 km of tunnel east and northeast of Penn Station and another 2 km above-ground around Randall’s Island, in addition to 5 km from Penn Station west across the river. The upshot is that this connection saves trains 3 minutes, and by freeing trains completely from regional rail traffic with four-tracking in the Bronx, it also permits using the lower 4% schedule pad, saving another 1 minute in the process.

If the United States is willing to spend close to $100 billion high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor – it isn’t, but something like $40-50 billion may actually pass some congressional stimulus – then it should spend $15 billion and then use the other $85 billion for other stuff. This include high-speed tie-ins as detailed above, as well as low-speed regional lines in the Northeast: new Hudson tunnels for regional traffic, the North-South Rail Link, RegionalBahn-grade links around Providence and other secondary cities, completion of electrification everywhere a Northeastern passenger train runs

Incremental investment

I hate the term “incremental” when it comes to infrastructure, not because it’s inherently bad, but because do-nothing politicians (e.g. just about every American elected official) use it as an excuse to implement quarter-measures, spending money without having to show anything for it.

So for the purpose of this post, “incremental” means “start with $15 billion to get Boston-Washington down to 3:20 and only later spend the rest.” It doesn’t mean “spend $2 billion on replacing a bridge that doesn’t really need replacement.”

With that in mind, the capacity increases required to get from bare Northeast Corridor high-speed rail to a more expansive system can all be done later. The overtakes on Baltimore-Washington would get filled in to form four continuous tracks all the way, the ones on Boston-Providence would be extended as outlined above, the bypasses on New York-New Haven would get linked to new tracks in the existing right-of-way where needed, the four-track narrows between Newark and Elizabeth would be expanded to six in an already existing right-of-way. Elizabeth Station has four tracks but the only building in the way of expanding it to six is a parking garage that needs to be removed anyway to ease the S-curve to the south of the platforms.

However, one capacity increase is difficult to retrofit: new tracks through New York. The most natural way to organize Penn Station is as a three-line system, with Line 1 carrying the existing Hudson tunnel and the southern East River tunnels, including high-speed traffic; Line 2 using new tunnels and a Grand Central link; and Line 3 using a realigned Empire Connection and the northern East River tunnels. The station is already centered on 32nd Street extending a block each way; existing tunnels going east go under 33rd and 32nd, and all plans for new tunnels continuing east to Grand Central or across the East River go under 31st.

But if it’s a 3-line system and high-speed trains need dedicated tracks, then regional trains don’t get to use the Hell Gate Line. (They don’t today, but the state is spending very large sums of money on changing this.) Given the expansion in regional service from the kind of spending that would justify so much extra intercity rail, a 4-line system may be needed. This is feasible, but not if Penn Station is remodeled for 3 lines; finding new space for a fourth tunnel is problematic to say the least.

Future-proofing

The point of integrated timetable planning is to figure out what timetable one want to run in the future and then building the requisite infrastructure. Thus, in the 1990s Switzerland built the tunnels and extra tracks for the connections planned in Bahn 2000, and right now it’s doing the same for the next generation. This can work incrementally, but only if one knows all the phases in advance. If timetable plans radically change, for example because the politicians make big changes overruling the civil service to remind the public that they exist, then this system does not work.

If the United States remains uninterested in high-speed rail, then it’s fine to go ahead with a bare-bones $15 billion system. It’s good, it would generate good profits for Amtrak, it would also help somewhat with regional-intercity rail connectivity. Much of the rest of the system can be grafted on top without big changes.

But then it comes to Penn Station. It’s frustrating, because anything that brings it into focus attracts architects and architecture critics who think function should follow form. But it’s really important to make decisions soon, get to work demolishing the above-ground structures starting when the Madison Square Garden lease runs out, and move the tracks in the now-exposed stations as needed based on the design timetable.

As with everything else, it’s possible not to do it – to do one design and then change to another – but it costs extra, to the tune of multiple billions in unnecessary station reconstruction. If the point is to build high-speed rail cost-effectively, spending the same budget on more infrastructure instead of on a few gold-plated items, then this is not acceptable. Prior planning of how much service is intended is critical if costs are to stay down.

Speed Zones on Railroads

I refined my train performance calculator to automatically compute trip times from speed zones. Open it in Python 3 IDLE and play with the functions for speed zones – so far it can’t input stations, only speed zones on running track, with stations assumed at the beginning and end of the line.

I’ve applied this to a Northeast Corridor alignment between New York and Boston. The technical trip times based on the code and the alignment I drew are 0:36:21 New York-New Haven, 0:34:17 New Haven-Providence, 0:20:40 Providence-Boston; with 1-minute dwell times, this is 1:33 New York-Boston, rising to maybe 1:40 with schedule contingency. This is noticeably longer than I got in previous attempts to draw alignments, where I had around 1:28 without pad or 1:35 with; the difference is mainly in New York State, where I am less aggressive about rebuilding entire curves than I was before.

I’m not uploading this alignment yet because I want to fiddle with some 10 meter-scale questions. The most difficult part of this is between New Rochelle and New Haven. Demolitions of high-price residential properties are unavoidable, especially in Darien, where there is no alternative to carving a new right-of-way through Noroton Heights.

The importance of speeding up the slowest segments

The above trip times are computed based on the assumption that trains depart Penn Station at 60 km/h as they go through the interlocking, and then speed up to 160 km/h across the East River, using the aerodynamic noses designed for 360 km/h to achieve medium speed through tunnels with very little free air. This require redoing the switches at the interlocking; this is fine, switches in the United States are literally 19th-century technology, and upgrading them to Germany’s 1925 technology would create extra speed on the slowest segment.

Another important place to speed up is Shell Interlocking. The current version of the alignment shaves it completely, demolishing some low-rise commercial property in the process, to allow for 220 km/h speeds through the city. Grade separation is obligatory – the interlocking today is at-grade, which imposes unreasonable dependency between northbound and southbound schedules on a busy commuter railroad (about 20 Metro-North trains per hour in the peak direction).

In general, bypasses west of New Haven prioritize the slowest segments of the Northeast Corridor: the curves around the New York/Connecticut state line, Darien, Bridgeport. East of New Haven the entire line should be bypassed until Kingston, even the somewhat less curvy segment between East Haven and Old Saybrook, just because it’s a relatively easy segment where the railroad can mostly twin with I-95 and not have any complex viaducts.

The maximum speed is set at 360 km/h, but even though trains can cruise at such speed on two segments totaling 130 km, the difference in trip time with 300 km/h is only about 3 minutes. Similarly, in southwestern Connecticut, the maximum speed on parts of the line, mostly bypasses, is 250 km/h, and if trains could run at 280 km/h on those segments, which isn’t even always possible given curvature, it would save just 1 minute. The big savings come from turning a 10 miles per hour interlocking into a modern 60 km/h (or, ideally, 90+ km/h) one, eliminating the blanket 120 km/h speed limit between the NY/CT state line and New Haven, and speeding up throats around intermediate stations.

Curve easements

Bypasses are easier to draw than curve modifications. Curves on the Northeast Corridor don’t always have consistent radii – for example, the curves flanking Pawtucket look like they have radius 600 meters, but no, they have a few radii of which the tightest are about 400 meters, constraining speed further. Modifying such curves mostly within right-of-way should be a priority.

Going outside the right-of-way is also plausible, at a few locations. The area just west of Green’s Farms is a good candidate; so is Boston Switch, a tight curve somewhat northeast of Pawtucket whose inside is mostly water. A few more speculative places could get some noticeable trip time improvements, especially in the Bronx, but the benefit-cost ratio is unlikely to be good.

Bush consulting on takings

In some situations, there’s a choice of which route to take – for example, which side of I-95 to go on east of New Haven (my alignment mostly stays on the north side). Some right-of-way deviations from I-95 offer additional choice about what to demolish in the way.

In that case, it’s useful to look for less valuable commercial properties, and try to avoid extensive residential takings if it’s possible (and often it isn’t). This leads to some bush consulting estimates of how valuable a strip mall or hotel or bank branch is. It’s especially valuable when there are many options, because then it’s harder for one holdout to demand unreasonable compensation or make political threats – the railroad can go around them and pay slightly more for an easier takings process.

How fast should trains run?

Swiss planners run trains as fast as necessary, not as fast as possible. This plan does the opposite, first in order to establish a baseline for what can be done on a significant but not insane budget, and second because the expected frequency is high enough that hourly knots are not really feasible.

At most, some local high-speed trains could be designated as knot trains, reaching major stations on the hour or half-hour for regional train connections to inland cities. For example, such a local train could do New York-Boston in 2 hours rather than 1:40, with such additional stops as New Rochelle, Stamford, New London (at I-95, slightly north of the current stop), and Route 128 or Back Bay.

But for the most part, the regional rail connections are minor. New York and Boston are both huge cities, so a train that connects them in 1:40 is mostly an end-to-end train, beefed up by onward connections to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington. Intermediate stops at New Haven and Providence supply some ridership too, much more so than any outlying regional connections like Danbury and Westerly, first because those outlying regional connections are much smaller towns and second much of the trip to those towns is at low speed so the trip time is not as convenient as on an all-high-speed route.

This does not mean Swiss planning maxims can be abandoned. Internal traffic in New England, or in Pennsylvania and South Jersey, or other such regions outside the immediate suburbs of big cities, must hew to these principles. Even big-city regional trains often have tails where half-hourly frequency is all that is justified. However, the high-speed line between Boston and New York (and Washington) specifically should run fast and rely on trips between the big cities to fill trains.

How much does it cost?

My estimate remains unchanged – maybe $7 billion in infrastructure costs, closer to $9-10 billion with rolling stock. Only one tunnel is included, under Bridgeport; everywhere else I’ve made an effort to use viaducts and commercial takings to avoid tunneling to limit costs. The 120 km of greenfield track between New Haven and Kingston include three major viaducts, crossing the Quinnipiac, Connecticut, and Thames; otherwise there are barely any environmentally or topographically sensitive areas and not many areas with delicate balance of eminent domain versus civil infrastructure.

I repeat, in case it is somehow unclear: for $7 billion in infrastructure investment, maybe $8 billion in year-of-expenditure dollars deflated to the early 2020s rather than early 2010s, trains could connect New York and Boston in 1:40. A similar project producing similar trip times between New York and Washington should cost less, my guess is around $3 billion, consisting mostly of resurrecting the old two-track B&P replacement in lieu of the current scope creep hell, building a few at-grade bypasses in Delaware and Maryland, and replacing the variable-tension catenary with constant-tension catenary.

None of this has to be expensive. Other parts of the world profitably build high-speed rail between cities of which the largest is about the size of Boston or Philadelphia rather than the smallest; Sweden is seriously thinking about high-speed trains between cities all of which combined still have fewer people than metropolitan Boston. Better things are possible, on a budget, and not just in theory – it’s demonstrated every few years when a new high-speed rail line opens in a medium-size European or Asian country.

New England High- and Low-Speed Rail

After drawing a map of an integrated timed transfer intercity rail network for the state of New York, people asked me to do other parts of the United States. Here is New England, with trains running every 30 minutes between major cities:

New England is a much friendlier environment for intercity rail growth than Upstate New York, but planning there is much more delicate. The map thus has unavoidable omissions and judgment calls, unlike the New York map, which straightforwardly follows the rule of depicting intercity lines but not suburban lines like the Long Island network. I ask that people not flame me about why I included X but not Y without reading the following explanations.

The tension between S-Bahn and ITT planning

The S-Bahn concept involves interlining suburban rail lines through city center to provide a high-frequency urban trunk line. For example, trains from a number of East Berlin neighborhoods and Brandenburg suburbs interline to form the Stadtbahn: in the suburbs, they run every 10 or 20 minutes, but within the Ring, they combine to form a diameter running regularly every 3:20 minutes.

The integrated transfer timetable concept instead involves connecting different nodes at regular intervals, typically half an hour or an hour, such that trains arrive at every node just before a common time and leave just after, to allow people to transfer. In a number of major Swiss cities, intercity trains arrive a few minutes before the hour every 30 minutes and depart a few minutes after, so that people can connect in a short amount of time.

S-Bahn and ITT planning are both crucial tools for good rail service, but they conflict in major cities. The ITT requires all trains to arrive in a city around the same time, and depart a few minutes later. This forces trains from different cities to have different approach tracks; if they share a trunk, they can still arrive spaced 2-3 minutes apart, but this lengthens the transfer window. The idea of an S-Bahn trunk involves trains serving the trunk evenly, which is not how one runs an ITT.

Normally, this is no problem – ITTs are for intercity trains, S-Bahns are for local service. But this becomes a problem if a city is so big that its S-Bahn network grows to encompass nearby city centers. In New York, the city is so big that its shadow reaches as far as Eastern Long Island, New Haven, Poughkeepsie, and Trenton. Boston is smaller but still casts shadows as far as southern New Hampshire and Cape Cod.

This is why I don’t depict anything on Long Island on my map: it has to be treated as the extension of an S-Bahn system, and cannot be the priority for any intercity ITT. This is also true of Danbury and Waterbury: both are excellent outer ends for an electrified half-hourly regional rail system, but setting up the timed transfers with the New Haven Line (which should be running every 10 minutes) and with high-speed rail (which has no reason to stop at the branch points with either Danbury or Waterbury) is infeasible. In Boston I do depict some lines – see below on the complications of the North-South Rail Link.

The issue of NSRL

The North-South Rail Link is a proposed north-south regional rail tunnel connecting Boston’s North and South Stations. Current plans call for a four-track tunnel extending across the river just north of North Station, about 4.5 km of route; it should cost $4 billion including stations, but Massachusetts is so intent on not building it lies that the cost is $12 billion in 2018 dollars.

In common American fashion, NSRL plans are vague about how service is to run through the tunnel. There are some promises of running intercity trains in addition to regional ones; Amtrak has expressed some interest in running trains through from the Northeast Corridor up to the northern suburbs and thence to Maine. However, we are not engaging in bad American planning for the purposes of this post, but in good Central European planning, and thus we must talk about what trains should run and design the tunnel appropriately.

The rub is that Boston’s location makes NSRL great for local traffic and terrible for intercity traffic. When it comes to local traffic, Boston is right in the middle of its metropolitan region, just offset to the east because of the coast. The populations of the North Side and South Side suburbs are fairly close, as are their commuter volumes into Boston. Current commuter rail ridership is about twice as high on the South Side, but that’s because South Station’s location is more central than North Station’s. NSRL really is a perfect S-Bahn trunk tunnel.

But when it comes to intercity traffic, Boston is in the northeast corner of the United States. There are no major cities north of Boston – the largest such city, Portland, is a metro area of 600,000. In contrast, going south, New York should not be much more than an hour and a half away by high-speed rail. Thus, high-speed rail has no business running through north of Boston – the demand mismatch south and north is too high.

Since NSRL is greatly useful for regional traffic but not intercity traffic, the physical infrastructure should be based on S-Bahn and not ITT principles, even though the regional network connects cities quite far away. For one, the tunnel should require all trains to make all stops (South Station, Aquarium, North Station) for maximum local connectivity. High-speed trains can keep feeding South Station on the surface, while all other traffic uses the tunnel.

But on the North Side, feeding North Station on the surface is not a good idea for intercity trains. The station is still awkwardly just outside city center. It also offers no opportunity to transfer to intercity trains to the most important city of all, New York.

The only resolution is to treat trains to Portland and New Hampshire as regional trains that just go farther than normal. The Nashua-Manchester-Concord corridor is already as economically linked to Boston as Providence and Worcester, and there are plans for commuter rail service there already, which were delayed due to political opposition to spending money on trains from New Hampshire Republicans after their 2010 election victory. Portland is more speculative, but electric trains could connect it with Boston in around an hour and a half to two hours. These trains would be making suburban stops north of Boston that an intercity train shouldn’t normally make, but it’s fine, the Lowell Line has wide stop spacing and the intermediate stops are pretty important post-industrial cities. At Portland, passengers can make a timed connection to trains to Bangor, on the same schedule but with shorter trainsets as the demand north of Portland is much weaker.

On the map, I also depict Boston-Cape Cod trains, which like Boston-Concord trains are really suburban trains but going farther. Potentially, the branch to Cape Cod – the Middleborough branch of the Old Colony Lines – could even run through with the Lowell Line, either the branch to Concord or the Wildcat Branch to Haverhill and Portland. Moreover, the sequencing of the branches should aim to give short connections to Boston-Albany high-speed trains as far as reasonable.

The issue of the Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor wrecks the ITT plan in two ways, one substantial and one graphical.

The snag is that there should be service on legacy track running at a maximum speed of 160-200 km/h in addition to high-speed service on high-speed tracks. There may be some track sharing between New York and New Haven to reduce construction costs, using timed overtakes instead of full track segregation, but east of New Haven the high-speed trains should run on a new line near I-95 to bypass the Shore Line’s curves, and the Shore Line should be running electric regional trains to connect to the intermediate cities.

The graphical problem is that the distance between where the legacy route is and where the high-speed tracks should be is short, especially west of New Haven, and depicting a red line and a blue line together on the map is not easy. I will eventually post something at much higher resolution than 1 pixel = 500 meters. This also affects long-distance regional lines that I’d like to depict on the map but connect only to legacy trains on the Northeast Corridor, that is the Danbury and Waterbury Branches.

For planning purposes, figure that both run every half hour all day, are electric, run through to and beyond New York as branches of the New Haven Line, and are timed to have reasonable connections to high-speed trains to Albany and points north in New York. Figure the same for trains between New Haven and Providence, with some additional runs in the Providence suburbs giving 15-minute urban frequencies to such destinations as Olneyville and Cranston.

The substantial issue is that the Northeast Corridor is far too high-demand for a half-hourly ITT. Intercity trains run between New York and Boston better than hourly today, and that’s taking twice as long as a TGV and charging 2.5-4 times as much. My unspoken assumption when planning how everything should fit together is that there should be a 400-meter long train every 15 minutes on the corridor past New Haven, spaced evenly around Boston to overtake regional trains to Providence at consistent locations. Potentially, there should be more local trains taking around 1:50 and more express trains taking around 1:35, and then all timed transfers should be to the local trains.

On the New Haven Line, too, regional rail demand is much more than a train every half hour. Trains run mostly every half hour today, with management that is flagrantly indifferent to off-peak service, and trip times that are about 50% longer than they should be. Nonetheless, best practice is to set up timed transfers such that various branches all connect to the same train, so that passengers can connect between different branches. This mostly affects Waterbury; it’s useful to ensure that Waterbury trains arrive at Bridgeport with a short transfer to a train toward New Haven that offers a quick connection to trains to points north and east.

Planning HSR around timed connections

Not counting lines that are in the Boston sphere, or the lines around Albany, which I discussed two weeks ago, there are three lines proposed for timed connection to high-speed rail: New London-Norwich, Providence-Worcester-Fitchburg, Springfield-Greenfield.

All three are regional lines, not intercity lines. They are not optimized for intercity speed, but instead make a number of local urban and suburban stops. This is especially true of Springfield-Northampton-Greenfield, a line that Sandy Johnston and I have been talking about since 2014. A Springfield-Greenfield line with 1-2 intermediate stops might be able to do a one-way trip in around 39 minutes, at which point a 45-minute operator schedule may be feasible with a very tight turnaround regime – but there’s enough urban demand along the southern half of the route that adding stops to make it about 50 minutes with a one-hour operator schedule is better.

The Providence-Worcester line is likewise slower than it could be if it were just about Providence and Worcester. The reason is that high-speed rail compresses distances along its route. Providence-Boston by high-speed rail is about 22 minutes nonstop, including schedule contingency. Boston-Worcester is about the same – slower near Boston because of scheduling difficulties along the Turnpike and the inner Worcester Line, faster near the outer end because Worcester has no chance of getting a city center station but rather gets a highway station. Now, passengers have a range of transfer penalties, and to those who are averse to connections and have a high personal penalty, the trip between the two cities is more attractive directly than via Boston. But there are enough passengers who’d make the trip via Boston that the relative importance of intermediate points grows: Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Uxbridge, Millbury. In that situation, the importance of frequency grows (half-hourly is a must, not hourly) and that of raw speed diminishes.

The onward connection to Fitchburg is about three things. First, connecting Providence with Fitchburg. Second, connecting Worcester with Fitchburg. And third, connecting Fitchburg with the high-speed line. This makes investments into higher speed more valuable, since Fitchburg’s importance is high compared with that of points between Worcester and Fitchburg. The transfer between the line and high-speed rail should be timed in the direction of Fitchburg-to-Albany first of all, and Providence-to-Albany second of all, as the connections from the endpoints to Boston are slower than direct commuter trains.

The presence of this connection also forces the Worcester station to be at the intersection with the line to Providence. Without this connection, it may be better to site the station slightly to the west, at 290 rather than 146, as the area already has Auburn Mall.

Finally, the New London-Norwich line is a pure last-mile connector from the New London train station, which is forced to be right underneath the I-95 bridge over the river, to destinations to the north. The northern anchor is Norwich opposite the historic center, but the main destination is probably the Mohegan Sun casino complex. Already there are many buses connecting passengers from New York to the casino. The one-way trip time should be on the order of 21-22 minutes, but with a turnaround it’s a 30-minute schedule, and the extension south to the historic center of New London is for completeness; with a timed connection, trains could get between Penn Station and Norwich in around 1:20 counting connection time, and between Penn Station and Mohegan Sun in maybe 5 minutes less.

What about Vermont?

Vermont’s situation is awkward. Burlington is too far north and too small to justify a connection to high-speed rail by itself. A low-speed connection might work, but the line from Burlington south points toward Rutland and not New York, and connecting it onward requires reversing direction. If Vermont had twice its actual population this might be viable, but it doesn’t.

But Vermont is right between New York and Montreal. I generally don’t show New York-Montreal high-speed rail on my maps. It’s a viable line, but people in both cities severely overrate it, especially compared with New York-Toronto; I have to remind readers this whenever I write about international high-speed trains. In the event such a line does open, Burlington is the only plausible location for a Vermont stop – everything else is too small, even towns that historically did have rail service, like Middlebury. Rutland could get a line running partly on high-speed track and partly on legacy track taking it down to Glens Falls or Saratoga Springs to transfer to onward destinations, or maybe Albany if trains run 2-3 minutes apart in pairs every 30 minutes.

Current plans for Vermont try to connect it directly to Boston via New Hampshire, and that is wrong. The Vermonter route is mountainous from Greenfield to Burlington; trains will never be competitive with driving there. Another route under occasional study going into Boston from the north was even included on a 2009 wishlist of high-speed rail routes, under the traditional American definition of high-speed rail as “train that is faster than a sports bicycle.” That route, crossing mountains in both New Hampshire and Vermont, is even worse. The north-south orientation of the mountains in both states forces east-west routes to either stick to the lowlands or consolidate to strong enough routes that high-speed rail tunnels are worthwhile.

How much does this cost?

As always, I am going to completely omit the Northeast Corridor from this cost analysis; an analysis of that will happen later, and suffice is to say, the benefit-cost ratio if there’s even semi-decent cost control is extremely high.

With that in mind, the central pieces of this program are high-speed lines from Boston to Albany and from New Haven to Springfield, in a T system. The 99 km New Haven-Springfield line, timetabled at 45 minutes including turnaround and maybe 36 minutes in motion, is on the slow side for high-speed rail, as it is short and has a crucial intermediate station in Hartford. It does not need any tunnels or complex viaducts, and property takings are nonzero but light; the cost should not be higher than about $2-2.5 billion, utilizing legacy track for much of the way.

The Boston-Albany line is much costlier. It’s 260 km, and crosses the aforementioned north-south mountains in Western Massachusetts. Tunnels are unavoidable, including a few kilometers of digging required just west of Springfield to avoid a slowdown on suburban curves. At the Boston end, tunneling may also be unavoidable next to the Turnpike. The alternative is sharing a two-track narrows with the MBTA Worcester Line in Newton; it’s possible if the trains run no more than every 15 minutes, which is a reasonable short-term imposition but may be too onerous in the longer term if better service builds up more demand for commuter rail frequency in Newton. My best guess is that without Newton, the line needs around 20 km of tunnel and can piggyback on 35 km of existing lines at both ends, for a total cost in the $6-8 billion range. This figure is sensitive to whether my 20 km estimate is correct, but not too sensitive – at 40 it grows to maybe $9 billion, at 0 it shrinks to $4.5 billion.

Estimating the costs of the blue lines on the map is harder. All of them are, by the standard of high-speed rail, very cheap per kilometer. A track renewal machine on a one-third-in-tunnel German high-speed line can do track rebuilding for about a million euros per single-track-kilometer. All of these lines would also need to be electrified from scratch, for $1.5-3 million per kilometer. Stations would need to be built, for a few million apiece. My first-order estimate is $1 billion for the three blue connector lines and about the same for Boston-Portland-Bangor; the Hyannis and Concord lines would go in a regional rail basket. The NSRL tunnel should be $4 billion or not much more, and not what Massachusetts wants voters to believe it is to justify its decision not to build it.

The reason for the relatively limited map (e.g. no Montreal service) is that these lines are not such slam dunks that they’re worth it at any price. Cost control is paramount, subject to the bare minimum of good service (e.g. electrification and level boarding). For what I think a fair cost is, those lines are still good, providing fast connectivity across New England from most places to most other places. Moreover, the locations of the major nodes, like Worcester and Springfield, allow timing bus interchanges as well, providing further connections to various suburbs and city neighborhoods.

The red high-speed lines are flashy, but the blue ones are important too. That’s the key takeaway from planning in Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands, all of which have high rail usage without great geography for intercity rail. Trains should be planned coherently as a network, with all parts designed in tandem to maximize connectivity. This isn’t just about going between Boston and Springfield or Boston and Albany or New Haven and Springfield, but also the long tail of weaker markets using timed connections, like New Haven-Amherst, Brockton-Worcester, Dover-Providence, Stamford-Mohegan Sun, and so on. A robust rail network based on ITT design principles could make all of these and many more connections at reasonable cost and speed.

The Different Travel Markets for Regional Rail

At a meeting with other TransitMatters people, I had to explain various distinctions in what is called in American parlance regional rail or commuter rail. A few months ago I wrote about the distinction between S-Bahn and RegionalBahn, but made it clear that this distinction was about two different things: S-Bahns are shorter-distance and more urban than RegionalBahns, but they’re also more about service in a contiguous built-up area whereas RegionalBahns have the characteristics of interregional service. In this post I’d like to explore the different travel markets for regional rail not as a single spectrum between urban and long-range service, but rather as two distinct factors, one about urbanity or distance and one about whether the line connects independent centers (“interregional”) or a monocentric urban blob (“intraregional”).

This distinction represents a two-dimensional spectrum, but for simplicity, let’s start with a 2*2 table, so ubiquitous from the world of consulting:

| Connection \ Range | Short | Long |

| Intraregional | Urban rail, S-Bahn | Big-city suburban rail |

| Interregional | Polycentric regional rail | RegionalBahn |

The notions of mono- and polycentricity are relative. Downtown Providence, Newark, and San Jose all have around 60,000 jobs in 5 km^2. But Caltrain and the Providence Line are both firmly in the RegionalBahn category, the other end being Downtown San Francisco or Boston, 70-80 km away with 300,000-400,000 jobs in 5-6 km^2. Newark, in an essentially contiguous urban area with New York, 16 km from Midtown and its 1.2 million jobs in 6 km^2, is relatively weaker and does not fit into the interregional category; a New York-Newark line is an S-Bahn.

Size matters

On the 2*2 table, the appellations “big-city” and “polycentric” are necessary. This is because longer-range rail lines are likelier to get out of the city and its immediate suburbs and connect to independent urban centers. Exceptions mostly concern the size of the primary urban cluster. If it is large, like New York, it can cast a shadow for tens of kilometers in each direction: commuter volumes are high from deep into Long Island, as far up the Northeast Corridor as Westport, as far up the Hudson as northern Westchester, and so on. In Paris, I wouldn’t be comfortable describing any of the RER and Transilien lines as RegionalBahn. In London, the closest independent cities of reasonable size are Cambridge, Brighton, Oxford, and Portsmouth, the first two about 80 km away and the last two about 100.

Tokyo, about as big as New York and London combined, casts an even longer shadow. In my post on S-Bahns and RegionalBahns I called some of its outer regional rail branches RegionalBahn, giving the examples like the Chuo Line past Tachikawa. But even that line is not really interregional in any meaningful way. It stays within the Tokyo prefecture as far as Takao, 53 km from Tokyo Station, and commuter service continues until Otsuki at kp 88, but everything along the line is bedroom communities for Tokyo or outright rural. The branching and short-turns at Tachikawa mean that the Chuo Line through Tachikawa is a long S-Bahn, and past Tachikawa is really a suburban commuter line too long to be an S-Bahn but too monocentric and peaky to be Regionalbahn (the peak-to-base frequency ratio is about 2:1, whereas German RegionalBahn is more commonly 1:1).

At the other end, we can have regional rail that is short-range but connects two distinct centers. This occurs when relatively small cities are in proximity to each other. In a modern first-world economy, these cities would form a polycentric region, like the Rhine-Ruhr or Randstad. Smaller regions with these characteristics include the Research Triangle, where relatively equal-size Raleigh and Durham are 40 rail kilometers apart, and Nord, where Lille is 30-50 km from cities like Douai and Valenciennes. This may even occur in a region with a strong primary center, if the secondary center is strong enough, as is the case for Winterthur, 28 km from Zurich, which has Switzerland’s fourth highest rail ridership.

Size is measured in kilometers, not people. Stockholm is a medium-size city region, but Stockholm-Uppsala is firmly within RegionalBahn territory, as the two cities are 66 km apart. Randstad’s major cities are all closer to each other – Amsterdam-Rotterdam is about 60 km – and that’s a region of 8 million, not 3 million like Stockholm and the remainder of Uppland and Södermanland.

The issue of frequency

The importance of the 2*2 table is that distance and urban contiguity have opposite effects on frequency: high frequency is more important on short lines than on long lines, and matching off-peak frequency to peak frequency is more important on interregional than intraregional lines.

Jarrett Walker likes to say that frequency is freedom, but what frequency counts as freedom depends on how long passengers are expected to travel on the line. Frequency matters insofar as it affects door-to-door travel time including wait time, so it really ought to be measured as a fraction of in-vehicle travel time rather than as an absolute number. An urban bus with an average passenger trip time of 15 minutes should run every 5 minutes or not much longer; if it runs every half hour, it might as well not exist, unless it exists for timed connections to longer-range destinations. But an intercity rail line where major cities are 2 hours apart can easily run every half hour or even every hour.

The effect of regional contiguity is more subtle. The issue here is that an intraregional line is likely to be used mostly by commuters at the less dense end. The effect of distance can obscure this, but within a large urban area, a 45-minute train will be full of commuters traveling to the primary city in the morning and back to the suburbs in the afternoon or evening; the same train between two distinct cities, like Boston and Providence, will not have so many commuters. In contrast, the same 45-minute trip will get much more reverse-commute travel and slightly more non-commute travel if it connects two distinct cities, because the secondary city is likelier to have destinations that attract travelers.

In no case are the extreme peak-to-base ratios of American commuter lines justifiable. Lines with tidal commuter flows can run 2:1 peak-to-base ratios, as is common in Tokyo, but much larger ratios waste capacity. The marginal cost of service between the morning and afternoon peaks is so low until it matches peak service that having less midday than peak service at all is only justifiable in very peaky environments. The 45-minute suburbs of New York, Tokyo, and other huge cities can all live with a 2:1 ratio, but other lines should have lower ratios, and interregional lines should have a 1:1 ratio.

The implication is that just as peak-to-base ratios going as high as 2:1 are acceptable for long-range intraregional lines, short-range interregional lines must run a constant, high frequency all day. I would groan at the thought of even half-hourly frequency on a 40-km interregional line; the worst I’m comfortable with is 15-20 minutes all day. Of note, such lines are necessarily pretty fast, since by assumption they make few intermediate stops to speed up travel between the two main cities – if there are significant cities in the middle then the lines connect even shorter-range cities and should be even more frequent.

Urban, suburban, intercity

Individual lines may have the characteristics of multiple variants of regional rail. They pass through urban neighborhoods on their way to outlying areas, which may be suburbs or independent cities; they may also pass through multiple kinds of independent areas.

In practice, in big cities this leads to three tiers on the same line: urban at the inner end, suburban at the middle end, interregional at the outer end. Inversions, in which there are independent cities and then suburbs, are possible but extremely rare – I can’t think of any in Paris, London, or New York, and arguably only three in Tokyo (Chiba, Saitama, Yokohama); fundamentally, if there are suburbs of the primary city beyond your municipality, then your municipality is likely to itself be popular as a suburb of the primary city.

That regional lines have these three tiers of demand type does not mean that every single regional line does. Some lines don’t reach any significant independent city. Some don’t usefully serve close-in urban areas – for example, the Providence Line barely serves anything urban, since the stop spacing is wide in order to speed up travel to high-demand suburbs and to Providence and the closest-in urban neighborhoods have Orange Line subway service. In rare cases, the suburban tier may be skipped, because there just isn’t much tidal suburban commuter ridership; in Boston, the Newburyport Line is an example, since its inner area has unbroken working-class urban development almost all the way to Salem, and then there’s almost nothing between Salem and Newburyport.

This does not mean that suburbs are always in between urban areas and independent cities – this is just a specific feature of large metropolitan areas. In smaller ones, the middle tier between urban and long-range interregional service is occupied by short-range interregional service rather than suburban commuter rail. Skipping the suburban tier, which is rare enough in large cities that in the cities I think about most often the only example I can come up with is the Newburyport Line, is thus completely normal in smaller cities.

Conclusion

There are common best practices for commuter rail: electrification, level boarding, frequent clockface schedules, timed transfers, fare integration, proof of payment fare collection.

However, high frequency means different things on lines of different characteristics. An interregional line should be running consistent all-day frequency, and if it is long enough could make do with half-hourly trains with timed connections to suburban buses; an urban line should be running every few minutes as if it were a metro line. Regional rail lines with characteristics off the main diagonal of the S-Bahn to RegionalBahn spectrum have different needs – suburban lines can have high peak frequency to reduce road congestion, although they should still have useful off-peak frequency; short-range interregional lines should run every 10-20 minutes all day.

The distinctions between intraregional and interregional lines and between short- and long-range lines may also affect other aspects of planning: station spacing, connections to local surface transit, connections at the city center end, through-running, etc. Even when the best industry practices are the same in all cases, the relative importance of different aspects may change, which changes what is worth spending the most money on.

Since an individual line can serve multiple markets on its way from city center to a faraway outlying terminal, it may be useful to set up a timetable that works for all of these markets and their differing needs. For example, urban lines need higher frequency than suburban and interregional ones, so a regional line with significant urban service should either branch or run short-turn trains to beef up short-range frequency. If there is a suburban area in the middle with demand for high peak frequency but also a secondary city at the outer end, it may be useful to give the entire line high all-day frequency, overserving the line off-peak just because the cost of service is low.

Ultimately, regional rail is about using mainline rail to fulfill multiple functions; understanding how these functions works is critical for good public transportation.

Small is not Resilient