YIMBY First, Building Reform Second

Last night I asked the American building reform advocates on Bluesky about different layouts and why developers don’t build them. I got different answers from different advocates about why the layout I’d just mocked of family-size apartments with two staircases isn’t being built in the US, some about regulations, but Mike Eliason said what I was most afraid of hearing: it’s doable but it’s more profitable to build small apartments. My conclusion from this is that while American and Canadian building regulations remain a problem and need to be realigned with European and Asian norms, they are a secondary issue, the primary one remaining how much housing is permitted to be built in the first place. Developers will keep building the most profitable apartment forms until they run out of the most profitable tenants.

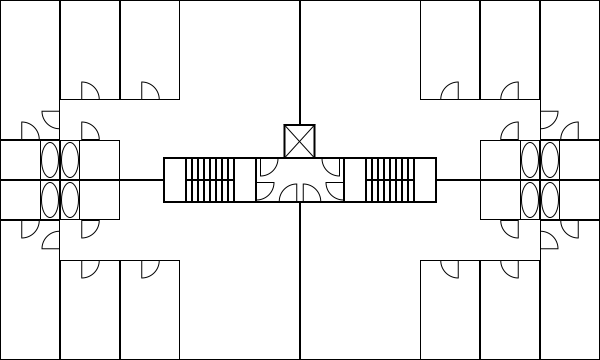

The mockup

The following mockup has a scale of 1 meter = 20 pixels, so the building is overall 18 meters by 30. This is a point access block rather than a double-loaded corridor (see definitions here), but it also has two staircases, emanating from the central access block. Each floor has four apartments, each with three bedrooms and two bathrooms, the ellipses in the image denoting bathtubs. The windows are top and bottom, but not left and right; these are single-aspect apartments, not corner apartments.

On Bluesky, I said the floorplate efficiency is 94%; this comes from assuming the step width and landing length are 1.1 meters each, a metrization of the International Building Code’s 44″, but to get to 94% assumes the staircase walls are included in the 1.1 meter width, so either it’s actually 90 cm width or, counting wall thickness, the efficiency is only 92.5%. The IBC allows 90 cm steps in buildings with an occupancy limit of up to 50, which this building would satisfy in practice at six stories (a three-bedroom apartment marketed to a middle-class clientele averages closer to two than four occupants due to empty nests, divorces, guest rooms, and home offices) but not as a legal limit. Regardless, 92.5% is average by the standards of European point access blocks, whose efficiency is reduced because the apartments are smaller, and very good by those of American double-loaded corridors.

Now, to be clear, this is still illegal in many American jurisdictions, as Alfred Twu pointed out in @-replies. The building mockup above has two means of egress, but the typical American code also requires minimum separation between the two staircases’ access points. This is an entirely useless addition – the main fire safety benefits of two staircases are that a single fire can’t interpose between residents and the stairs if the two staircases are at opposite ends of the building, but that’s not legally required (quarter-point staircases are routine), and that the fire department can vent smoke through one staircase while keeping the other safe, which does not require separation. Nonetheless, this is not the primary reason this isn’t getting built even where it is legal, for example in jurisdictions that permit scissor stairs or have a smaller minimum distance between the two staircases, like Canada.

I was hoping the answer I’d get would be about elevator costs. The elevator in the mockup is European, 1.6*1.75 meters in exterior dimensions; American codes require bigger elevators, which is by itself a second-order issue, but then installation costs rise to the point that developers prefer long buildings on corridors for the lower ratio of elevators to apartments. But nobody mentioned that as a reason.

The rent issue

Mike Eliason responded to my question about why buildings like the above mockup aren’t being built by talking about market conditions. The above building, with 540 m^2 of built-up area per floor, can host four three-bedroom apartments, each around 127 m^2, or it can host 16 studios, each around 29 m^2. In Seattle, the studio can rent for $1,500/month; the three-bedroom will struggle to earn the proportionate $6,000/month.

It’s worth unpacking what causes these market conditions. The three-bedroom is marketed to a family with children. The children do not earn money, and, until they reach kindergarten age, cost thousands of dollars a month each in daycare fees; if they don’t go to daycare then it means the family only has one income, which means it definitely can’t afford to compete for building space with four singles who’d take four studios, or it has parents in the immediate vicinity, which is rare in a large, internally mobile country. The family has options to outbid the four singles, but they’re limited and require the family to be rather wealthy – two incomes are obligatory, at high enough levels to be able to take the hit from taxes and daycare; the family would also need to be wedded to living in the city, since the suburbs’ housing is designed entirely for families, whereas the singles take a serious hit to living standards from suburbanizing (they’d have to get housemates). In effect, the broad middle and lower middle classes could afford the studios as singles, but only the uppermost reaches of the middle class can pay $6,000/month for the three-bedroom.

In economic statistics, imputation of living standards for different household sizes takes this degressivity of income – $6,000/month for a family of four is a struggle, $1,500/month for a single is affordable on the average US wage – and uses a hedonic adjustment for household sizes. example by taking the square root of household size as the number of true consumption units. To INSEE, a family of four has 2.1 equivalent consumption units; elsewhere, it’s a square root, so it has 2 consumption units. A rental system that maintains a 4:1 ratio has no way for the family to compete.

The upshot is that the developers need to run out of the tenants who can most easily afford rent before they build for the rest. Normally it’s treated as a matter of distribution of units among different social classes, but here it’s a matter of the physical size of the unit. This is why YIMBY first is so important: eventually developers will run out of singles and then have to build for families.

Exact same logic why new apartment units are becoming smaller and smaller here, in Hong Kong. Let’s say when you can sell a 900sqf unit at $10k/sqf, if you build three 300sqf units instead, you could sell them at $12-15k/sqf, which is significantly more profitable.

With higher interest rates things are starting to reverse. Small studio or 1 bed condo flats usually are only to investors, because the type of families who occupy these are usually renters. Now that interest rates are high, the rents can no longer cover mortgage payments, so investors aren’t buying these compact floorplans anymore. This is especially true in cities like Toronto. The unit cost must come down for smaller condo flats for inventory to move. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGfFBP7U7pQ

Or the pay has to go up…

The point of high interest rates is to combat inflation though. Which is to say make prevent wages from going up because you cool the economy so workers are unable to demand those raises. Over a decade you will see likely see those raises, but in the short term expect raises of less than inflation.

I’m ancient. I’m old enough to remember how Saint Ronnie of Reagan promulgated the myths. Most of them are myths. The one about pay is that if the Federal minumum wage is raised employers will go out of business. I live in a state where the state minimum is twice the Federal. We have labor shortages. I seems every last store I go into has the “Now Hirrrrrinnng!!” sign out. The places that aren’t retail tend to have an A-frame/Sandwich board by the curb.

If someone working full time, whatever “full time” is, the 11th Commandment is not “thou shall work 40 hours a week”, qualifies for benefits like food stamps or medicaid that is a subsidy to their employer. If people can’t afford things it means their pay is too low. No matter how employers and rich people want to twist it into a moral failure of the employee.

High interest rates are the logical financial response to inflation. When Jimmy Carter was president, inflation was 12%. BUT, there were states where charging more than 8% on a loan was de-facto usury. So, banks stopped lending money, because 8% loans would be paid back with 12% inflated money that had less buying power than the original loan. State legislatures went into emergency sessions to raise the allowed rates, because a real estate market working with only cash transactions is near-zero in size.

I think what you write contributes, but I think the main factor is that the building costs of single family housing is so much cheaper per square meter. So the large apartments are competing with a much cheaper building style (which the small apartments are not). This makes large quantities of very large apartments unlikely outside of very dense cities (which the US really only has barely 1 of). Only rich people with very high urban preferences will want to pay the cost premium.

I think historically this gap was smaller.

In addition US and Japanese inner city single family housing (e.g. LA, central Tokyo) acctually has pretty high Floor Area Ratios. The multi dwelling housing area has higher FAR for an area but often only by a factor 1.5 to 2 or so. And the construction cost premium is often higher than that. So land prices have to be quite extreme in these cases, and prices of single family housing very very high, for multi dwelling areas for economically compete. I think very few areas of the US fulfill these conditions (given existing cost disparity).

this is the building code problem Alon references and decides is second order. In most of the Europe cost per square foot declines as density increases.

Overall, you are correct, the issue in US cities with housing problems is lack of production, not lack of a certain design.

I’m not sure your central access block is ADA compliant. You need clear space in front of each door and I’m not sure that the swing of another door is allowed to encroach.

Your elevator is definitely not ADA compliant, those need to be 1.3 x 1.75 m INSIDE dimensions.

“the main fire safety benefits of two staircases are that . . . and that the fire department can vent smoke through one staircase while keeping the other safe,”

This is so absurdly untrue I cannot believe you are still stating this blatantly false fact. I went into detail why this never ever happens in the comments here: https://pedestrianobservations.com/2025/01/10/quick-note-the-experience-of-train-stations/#comment-163867

I’m sure the fire officials are going to want to know what happens when the tenant in the northwest apartment decides to rid the mattress of demons by soaking it in something very flammable and lighting it in itsy bitsy tiny little elevator lobby. …. I just noticed this, the doors to the stairwells would be blocked by the mattress because they swing the wrong way for “escape”. Code very likely says everything along the escape route is “push” – full blown panic bar push – with an exception for the door to a “private” space.

Most of what you write here makes no sense (lighting a mattress on fire in an elevator lobby?!?!) but you are correct that doors into fire stairs need to swing out along the path of travel (that is into the stairs). I’m not super familiar with ADA requirements but this might require the stairs to be slightly larger to provide ADA clear space/a wheelchair refuge on the landing. It would however get rid of the door swing interference issue I was bringing up.

People do all sort of crazy things to get rid or the demons. Or to follow the advice of the voices. Or retaliate against the tenant with some gasoline soaked whatever. Or think two candles in a paper bag would be festive. The fire officials are going to want to know how well things are going to work when some one thinks fire is the solution. Not well because because the itty bitty teensy weensy vestibule just outside the apartment is small and will be engulfed quickly.

And the poindexter who came up with this so clueless the egress doors open the wrong way.

It isn’t an “itty bitty teensy weensy vestibule”. It is 2.2 m wide. Minimum hallway width in a conventional building (long corridor with a stair a either end) is only 0.9 to 1.1 m wide. This plan has a corridor almost as wide as the largest minimum corridor specified by code (2.5 m, for hospitals to allow bed evacuation).

But all of this is irrelevant for your scenarios. Someone who pours gasoline outside of their neighbor’s door is going to quickly engulf and block any corridor of any width above, first at the point of ignition from the flames (which will be much wider than 2.5 m) and then in the entire corridor from the smoke (gasoline produces thick black smoke, I assume mattresses soaked in whatever to get rid of the demons do as well). If you’re lucky the sprinklers will suppress things quickly enough to allow people to escape, if not, well the code cannot fully deal with deliberate acts of arson, just like the traffic code cannot stop terrorists who use trucks for ramming attacks.

In one way this layout is safer in an arson situation than a larger building with a long corridor. Only 4 units on the floor with the arson are at risk for being blocked with people trapped. In a regular building there will be at least six units (the door with gasoline poured on it, the one across the hall, and the two to either side) that are blocked, and there is a risk that many more people on hearing the fire alarm will step directly into the hallway and encounter a face full of black smoke, causing them to pass out or panic and find themselves laying in a burning corridor. Sure, in a long enough corridor you might be far enough away from the fire to evacuate safely at first, but there is the risk of the fire spreading to either side trapping further people, while in Alon’s layout someone that far away is in a separate building with its own point access corridor and stairs with virtually no risk of the fire reaching them before they can get out.

I’ve had jobs where mattress sizes are important. And other jobs where the size of doors and windows are important. And I’ve actually been in multifamily buildings. Some of them with elevators. I didn’t have to consult measurements, door, door, mattress is almost as long.

On second thought I take it back. Nutjob wrestles a full size mattress into the hall it would stop anybody in any of the apartments from opening the door. And the wrestler would have difficulty getting out of the hall. People who think the mattress is full of demons aren’t the most detailed planners. Roll it up? I suppose it could be an upholstered armchair that has voices emanating from it. Or the downstairs tenant shooting mind rays and a pile of paper recycling in front of their door is the solution. I’ll stop speculating on the variants.

And when I think of all the corridors I’ve been in the doors open away from the hall. Imagine the mayhem along a long corridor when the fire alarms go off, if they opened into the hall . Imagine the mayhem in normal operation if they opened into the hall.

I’ve been out in the woods too long. Locking the doors? I just have to unlock it when I get back.. How many prospective tenants are going to ask where they mount the deadbolt and the chain latch. And say something along the lines of “Goodness gracious me, whatever were they thinking” and rent different apartment?

Poindexter didn’t think many things through. I’ve grown weary of any further attempts at analyzing the tomfoolery. … Main one is that the egress doors open in the direction of the egress path. The evacuees, some of who may be …. in a panic… don’t have to think about it. All they have to do is push the panic bar.

You’re right, and the key issue is single-family zoning.

In single-family zones, the number of units is constrained more tightly than the FAR. So the cost of land is borne entirely by the first bedroom in the unit. In the single-family neighborhood that sits under my 8th-floor window, the price of a tear-down is $900,000. The 1930s 2-or 3-bedroom houses are being replaced with 5-bedroom 5000-sq ft McMansions. This is common in DC and its inner suburbs where there is a lot of demand for housing.

In multifamily zones, FAR is constrained (usually directly otherwise, by height limits and by the greater construction cost of very tall buildings). The number of units is rarely constrained at all, except by minimum unit sizes in the building code. So, the smaller the units, the more first bedrooms you can spread the land (& entitlement) cost over.

When the bulk of the residential land is zoned single-family, the net effect is a shortage of small apartment units while big houses are full of empty bedrooms. This reflects itself in the price per square foot. In the example out my window, Zillow estimates the price of the new mansionizations as $500 per square foot, while the 10-year-old condo building next to my building has two 2-bedroom units (1241 & 1660 sq ft) listed at $720 per square foot. And for the price of the mansionizations you get a detached garage and a yard.

Here’s the link to Zillow. The two featured condo units are in the building at the top right of the image. You can get the Zillow estimate & square footage of the 1-family houses by hovering over the image. (The houses at the left end of the image are more expensive, more like $600 per sq ft, because they have big back yards. Ignore the prices below $2 million, they are old houses.)

“In single-family zones, the number of units is constrained more tightly than the FAR.”

This is a great point. Nothing about size or building layout helps if you can only get one unit per lot. At a metro level, townhomes and duplexes/triplexes can do great things for overall affordability compared to widespread single family zoning even if their spot density is not as high as mid-rise apartment building. Montreal is a good example of this. Reducing minimum lot sizes is another policy that leaves “single-family” zones, but achieves the same effect as a four unit apartment building if lot size minimum is reduced to 1/4 as before. Houston saw a big increase in townhome production after reducing lot sizes citywide in the 2010s.

Multifamily FAR and number of units is often somewhat constrained by parking requirements. If someone thought of families, wrote down “two offstreets spots per unit” and applied this to 1BRs and studios as well, then a 3-story building needs a larger parking lot than its own footprint.

This extravaganza of bizarre doors and single elevator is going to be in New Urbanist wet dream of a transit village where half the tenants don’t own cars. And the other half own one. The parking can be under the building.

That should be the case. However, if whoever wrote the minimum parking requirement (sometimes a part of zoning, sometimes part of a different document) is a moron, which they often are, they either:

Look at typical suburban single-family. Each house has: 2 spots in the garage, 2 spots in the driveway, 2-ish spots in the parking lane (excluding the curb cut). ~6 spots total. Maybe 1% of households residing in this sort of house has that many cars. Transparently, customer demand isn’t the force driving the construction of this many parking spots — regulations do.

So the life/safety parts of the code are going to be radically changed but not the parking requirements? Yep, un-huh, sure. Okay

There’s no one person who “writes” the parking section of a zoning code. There is a staffer who makes proposals, political actors who exert pressure, and elected officials or semi-political planning boards who make the final decision.

It’s extremely common for the final decision-makers to seek a compromise, to throw a bone to the nimbys when they are pro-development, or to hide their nimby proclivities in the part of the code where its effect is most easily disguised while pretending to do something about the housing shortage. So don’t look for logic in a zoning code.

Parking is one of the easiest issues for nimbys to stir up support with. Lots of homeowners would be ashamed to say, or even think, “I don’t want those people living next door” but find it socially acceptable to say “I don’t want those people’s cars parked in front of my house.” I’ve seen time and again when zoning reforms are undermined by failure to change parking requirements.

NIMBY’s don’t care what club they wield. Some of them can be swinging the parking bat and some of them can be swinging “but what about the shadows, the shadows will cause rickets in our children” hammer. I suspect that “egress doors open with a panic bar in the direction of egress” is not negotiable and the parking people and the shadow people and the too much traffic and the too much sewage people will all agree that really really stupid exit doors are stupid.

But it’s always sunny in StrongTown in greater Railfanlandia, so who knows. Where all the children are exceptional and their parents walk to the train station to go to work.

Worth keeping in mind that looking at efficiency as a percentage is just shorthand for common area costs. Corridors are less efficient but they are cheap space compared to elevators and stairs. A ten-unit building may be 94% efficient, but apartments in an 85% efficient eighty-unit building might carry just a third of the common area costs compared to the smaller building. And the larger building might support common area amenities (fitness, lounge, etc) that are appealing to residents

The point about the rental market supersedes this issue, but I wonder if the stair-spacing requirement could be satiated by abutting a single stairwell against the party wall, alternately including or excluding an elevator. Apartments could access either of the two stairwells that would be adjacent, one of which would include an elevator (One end apartment would have a nonstandard floor plan to accommodate its second stairwell).

Of course, zoning reform nullifies this issue, but it may be of import for some interim projects.

Despite the talk about the lack of family sized apartments, aren’t studios and 1 bedrooms still clearly more lacking?

It’s considered more normal for friends or randos to share a family sized apartment than it is to raise a family in a studio or 1 bedroom.

The lower per floor area price carried by family sized apartments suggests that it’s being dragged down by singles and couples preferring privacy over more space. If there were enough small apartments, they would be much cheaper still, to the point that the per floor area prices would be roughly similar.

When I have looked at house prices in the UK they are roughly the same per square meter regardless of size.

Apartments are probably cheaper than houses at this point given service charges.

Unrelated but the Association of American Railroads has released another nonsense “study” that falsely claims that electrifying North American freight railroads is “infeasible”:

https://www.aar.org/news/study-confirms-catenary-system-infeasible-for-u-s-freight-rail-network/

Although “infeasible” is value judgement that cannot exactly be proven or disproven, the railroads are probably correct here. The US rail network is vast, the Class I’s alone have more track than all of the EU-27, and other railways in the US have an additional ~37,000 km on top of that. India is the only major network that is almost totally electrified, and it is less than a third of the US (not much larger than a quarter in fact). Total electrified track in the EU and Russia combined, would only cover about 2/3 of the US network, and even if you added India’s almost 100% electric network you are only barely covering the Class I’s, and still not all of the US.

And if you did spend $1+ trillion for full electrification, what does it get you? The US railroad industry uses only about 9 million gallons of diesel per day – road users in the US consume about 375 million gallons of gas and 115 million gallons of diesel each day. Spending $1T on other rail or transit improvements and lowering driving by 5% would reduce roughly double the emissions.

The big issue shouldn’t be electrifying freight lines across the country, but full electrification of all passenger lines. In addition to the emissions reduction, electrification does amazing things for passenger rail performance. The performance is a requirement for High Speed Rail, but also increases ridership on other lines: Caltrain in San Francisco has seen a ~40% jump in ridership in a few months since it went fully electric, including month over month ridership increases over the holiday months, which never happens.

I should note that a discussion at Caltrain-HSR Compatibility blog showed that modern Battery-EMUs (BEMUs) that can charge in motion under catenary have great re-charge performance under 25kV. The high voltage makes it really quick to recharge the batteries. You only need a little bit time under wire and/or wire at end of line stations (for charging during turnaround) to get a decent range on non-electrified track. The performance makes partial electrification and use of BEMUs look like a sensible strategy, rather than vaporware to sabotage “true” electrification. Alon has made the same observation about trolly busses, with wire strung on the high-capacity trunk routes but batteries used on the lower frequency/shorter branches.

But even this partial electrification model works better with passenger rail than freight. Passenger operations run the same service day in and out and can plan what they electrify to match that service and meet the range limitations of off wire use. Freight on the other hand, runs service based on their clients/orders, not based on a schedule. If a shipment runs from one branch to another branch with only a short portion on the trunk, a BEMU becomes unusable because it will run out of charge.

It’s worth noting the Class I’s think they can electrify for ~$5M/km. Caltrain spent ~$30M/km. Some part of this was also signal upgrades for PTC, but I don’t know how it breaks down. As with everything else related to US transit infrastructure, reducing costs by 70-80% would make it a lot easier to electrify all of those tracks in passenger use. For what was spent on only SF-San Jose would have electrified almost the entire Northern Californian mainline passenger network (all of Caltrain, plus Capitol Corridor to Sacramento and beyond, plus the SMART train.

Mindless electrification of obscure branches that have service to one customer that gets a few cars now and then?

They only have to electrify between the yards where few dozen cars going out onto a branch twice a week get hooked up to a diesel. Diesels run quite happily on corn oil. Once the automobile fleet begins electrifying all that corn that goes into ethanol for automobile fuel can be switched to corn varieties that have high oil production. The obscure branches might be maintained to Class 3 which means low speed and short distances. The battery fans can consider a battery tender car.

If the passenger trains have to share tracks with the freight trains the passenger trains have to toddle along at freight train speeds. Or it’s not a very busy freight route and there are only a few passenger trains every day. If it’s not a busy freight route, who is going to pay to maintain the tracks for higher speed passenger service? A few times a day.

It not a truck. The cars get switched.

It’s a locomotive not an MU. Though locomotives can be MU’d which is one of the reasons diesels were a lot cheaper to run than steam locomotives. The locomotive can raise it’s pantograph just like the trolley buses can. Trucks can raise their pantographs like the buses do too.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolleytruck

If you aren’t running passenger trains hourly, you probably shouldn’t bother at all.

Regardless it is possible to run passenger and freight trains on the same line. It is done the whole time in Europe.

You have no concept of the scale.

https://www.railstate.com/long-trains-on-the-u-s-rail-network-whats-really-moving/

It is very expensive to build kilometers long sidings for the kilometers long trains so they can get out of the way of the faster passenger trains. So they don’t have very many sidings.

You have no concept of the scale otherwise either.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_area

How much money do you really save over a 750m British freight train?

In June, Amtrak will restart Gulf Coast service (New Orleans – Mobile) which hasn’t operated since Hurricane Katrina. One of the prerequisites was the building of extra tracks in Mobile so passenger trains and freight don’t get in each others way. Amtrak is allowed a maximum of two roundtrips per day.

The Class 1s think they can electrify for $2m/km (link).

Thanks, Alon.

Regarding the last part of your post – In Israel, apartments’ size is quite regulated through the detailed plan. The developer has leeway but still has to include apartemtns of different sizes in the mix (today usually municipalities demand smaller units to be included). I know this is quite frequent in Europe as well. Is it not the case in North America? the post presupposes the housing unit mix is determined solely by the developer (or perhaps I misunderstood you).