Category: Incompetence

Amtrak Releases Bad Scranton Rail Study

There’s hot news from Amtrak – no, not that it just announced that it hired Andy Byford to head its high-speed rail program, but that it just released a study recommending New York-Scranton intercity rail. I read the study with very low expectations and it met them. Everything about it is bad: the operating model is bad, the proposed equipment is bad and expensive, the proposed service would be laughed at in peripheral semi-rural parts of France and Italy and simply wouldn’t exist anywhere with good operations.

This topic is best analyzed using the triangle of infrastructure, rolling stock, and schedule, used in Switzerland to maximize the productivity of legacy intercity line, since Swiss cities, like Scranton, are too small to justify a dedicated high-speed rail network as found in France or Japan. Unfortunately, Amtrak’s report falls short on all three. There are glimpses there of trying and failing, which I personally find frustrating; I hope that American transportation planners who wish to imitate European success don’t just read me but also read what I’ve read and proactively reach out to national railways and planners on this side of the Atlantic.

What’s in the study?

The study looks at options for running passenger trains between New York and Scranton. The key piece of infrastructure to be used is the Lackawanna Cutoff, an early-20th century line built to very high standards for the era, where steam trains ran at 160 km/h on the straighter sections and 110 km/h on the curvier ones. The cutoff was subsequently closed, but a project to restore it for commuter service is under construction, to reach outer suburbs near it and eventually go as far as the city’s outermost suburbs around the Delaware Water Gap area.

Amtrak’s plan is to use the cutoff not just for commuter service but also intercity service. The cutoff only goes as far as the Delaware and the New Jersey/Pennsylvania state line, but the historic Lackawanna continued west to Scranton and beyond, albeit on an older, far worse-built alignment. Thus, the speed between the Water Gap and Scranton would be low; with no electrification planned, the projected trip time between New York and Scranton is about three hours.

I harp on the issue of speed because it’s a genuine problem. Google Maps gives me an outbound driving time of 2:06 right now, shortly before 9 pm New York time. The old line, which the cutoff partly bypassed, is curvy, which doesn’t just reduce average speed but also means a greater distance must be traversed on rail: the study quotes the on-rail length as 134 miles, or 216 km, whereas driving is just 195 km. New York is large and congested and has little parking, so the train can afford to be a little slower, but it’s worth it to look for speedups, through electrification and good enough operations so that timetable padding can be minimized (in Switzerland, it’s 7% on top of the technical travel time).

Operations

The operations and timetabling in the study are just plain bad. There are two options, both of which include just three trains a day in each direction. There are small French, Italian, and Spanish towns that get service this poor, but I don’t think any of them is as big as Scranton. Clermont-Ferrand, a metro area of the same approximate size as Scranton, gets seven direct trains a day to Paris via intermediate cities similar in size to the Delaware Water Gap region, and these are low-speed intercities, as the area is too far from the high-speed network for even low-speed through-service on TGVs. In Germany and Switzerland, much smaller towns than this can rely on hourly service. I can see a world in which a three-hour train can come every two hours and still succeed, even if hourly service is preferable, but three roundtrips a day is laughable.

Then there is how these three daily trains are timetabled. They take just less than three hours one-way, and are spaced six hours apart, but the timetable is written to require two trainsets rather than just one. Thus, each of the two trainsets is scheduled to make three one-way trips a day, with two turnarounds, one of about an hour and one of about five hours.

Worse, there are still schedule conflicts. The study’s two options differ slightly in arrival times, and are presented as follows:

Based on the results of simulation, Options B and D were carried forward for financial evaluation. Option B has earlier arrival times to both New York and Scranton but may have a commuter train conflict that remains unresolved. Option D has later departure times from New York and Scranton and has no commuter train conflicts identified.

All this work, and all these compromises on speed and equipment utilization, and they’re still programming a schedule conflict in one of the two options. This is inexcusable. And yet, it’s a common problem in American railroading – some of the proposed schedules for Caltrain and high-speed rail operations into Transbay Terminal in San Francisco proposed the same.

Equipment and capital planning

The study does not look at the possibility of extending electrification from its current end in Dover to Scranton. Instead, it proposes a recent American favorite, the dual-mode locomotive. New Jersey Transit has a growing pool of them, the ALP-45DP, bought most recently for $8.8 million each in 2020. Contemporary European medium-speed self-propelled electric trains cost around $2.5 million per US-length car; high-speed trains cost about double – an ongoing ICE 3 Neo procurement is 34 million euros per eight-car set, maybe $6 million per car in mid-2020s prices or $5 million in 2020 prices.

And yet somehow, the six-car dual-mode trains Amtrak is seeking are to cost $70-90 million between the two of them, or $35-45 million per set. Somehow, Amtrak’s rolling stock procurement is so bad that a low-speed train costs more per car than a 320 km/h German train. This interacts poorly with the issue of turnaround times: the timetable as written is almost good enough for operation with a single trainset, and yet Amtrak wants to buy two.

There are so many things that could be done to speed up service for the $266 million in capital costs between the recommended infrastructure program and the rolling stock. This budget by itself should be enough to electrify the 147 km between Dover and Scranton, since the route is single-track and would carry light traffic allowing savings on substations; then the speed improvement should allow easy operations between New York and Scranton every six hours with one trainset costing $15 million and not $35-45 million, or, better yet, every two hours with three sets. Unfortunately, American mainline rail operators are irrationally averse to wiring their lines; the excuses I’ve seen in Boston are unbelievable.

The right project, done wrong

There’s an issue I’d like to revisit at some point, distinguishing planning that chooses the wrong projects to pursue from planning that does the right projects wrong. For example, Second Avenue Subway is the right project – its benefits to passengers are immense – but it has been built poorly in every conceivable way, setting world records for high construction costs. This contrasts with projects that just aren’t good enough and should not have been priorities, like the 7 extension in New York, or many suburban light rail extensions throughout the United States.

The intercity rail proposal to Scranton belongs in the category of right projects done wrong, not in that of wrong projects. Its benefits are significant: putting Scranton three hours away from New York is interesting, and putting it 2.5 hours away with the faster speeds of high-reliability, high-performance electric trains especially so.

As a note of caution, this project is not a slam dunk in the sense of Second Avenue Subway or high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor, since the trip time by train would remain slower than by car. If service is too compromised, it might fail even ignoring construction and equipment costs – and we should not ignore construction or equipment costs. But New York is a large city with difficult car access. There’s a range of different trips that the line to Scranton could unlock, including intercity trips, commuter trips for people who work from home most of the week but need to occasionally show up at the office, and leisure trips to the Delaware Water Gap area.

Unfortunately, the project as proposed manages to be both too expensive and too compromised to succeed. It’s not possible for any public transportation service to succeed when the gap between departures is twice as long as the one-way trip time; people can drive, or, if they’re car-free New Yorkers, avoid the trip and go vacation in more accessible areas. And the sort of planning that assumes the schedule has conflicts and the dispatchers can figure it out on the fly is unacceptable.

There’s a reason planning in Northern Europe has converged on the hourly, or at worst two-hourly, frequency as the basis of regional and intercity timetabling: passengers who can afford cars need the flexibility of frequency to be enticed to take the train. With this base frequency and all associated planning tools, this region, led by Switzerland, has the highest ridership in the world that I know of on trains that are not high-speed and do not connect pairs of large cities, and its success is slowly exported elsewhere in Europe, if not as fast or completely as it should be. It’s possible to get away without doing the work if one builds a TGV-style network, where the frequency is high because Paris and Lyon are large cities and therefore frequency is naturally high even without trying hard. It’s not possible to succeed on a city pair like New York-Scranton without this work, and until Amtrak does it, the correct alternative for this study is not to build the line at all.

New York Can’t Build, LaGuardia Rail Edition

When Andrew Cuomo was compelled to resign, there was a lot of hope that the state would reset and finally govern itself well. The effusive language I was using at the time, in 2021 and early 2022, was shared by local advocates for public transportation and other aspects of governance. A year later, Governor Hochul has proven herself to be not much more competent than Cuomo, differing mainly in that she is not a violent sex criminal.

Case in point: the recent reporting that plans for rail to LaGuardia Airport are canceled, and the option selected for future development is just buses, makes it clear that New York can’t build. It’s an interesting case in which the decision, while bad, is still less bad than the justification for it. I think an elevated extension of the subway to LaGuardia is a neat project, but only at a normal cost, which is on the order of maybe $700 million for a 4.7 km extension, or let’s say $1 billion if it’s mostly underground. At New York costs, it’s fine to skip this. What’s not fine is slapping a $7 billion pricetag on such an endeavor.

LaGuardia rail alignments

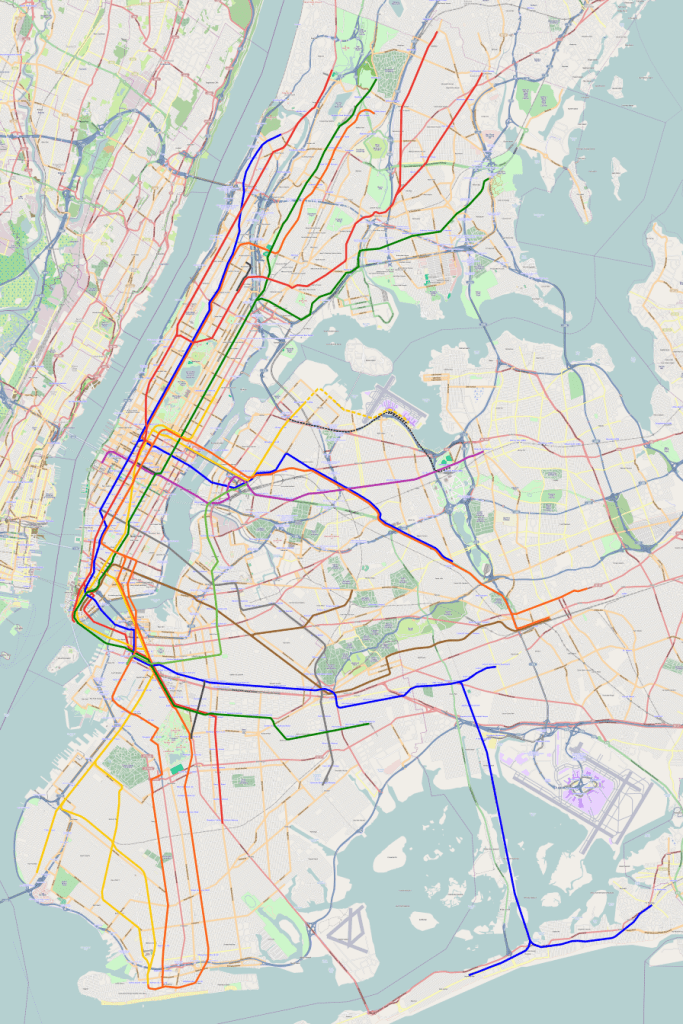

On my usual base map of a subway system with some lines swapped around to make the system more coherent but no new construction, here are the various rail alignments to the airport:

A full-size image can be found here. All alternatives are depicted as dashed lines; the subway extension is depicted in yellow in the same color as the Astoria Line, and would be elevated until it hit airport grounds, while the other two options, depicted as thinner black lines, are people movers or air trains. The air train option going east of airport grounds was Cuomo’s personal project and, since it went the wrong way, away from Manhattan, it was widely unpopular among anyone who did not work for Cuomo and was for all intents and purposes dead shortly after Hochul took office.

The issue of construction costs

Here’s what the above-linked New York Times article says about the rail alignments.

The panel’s three members — Janette Sadik-Khan, Mike Brown and Phillip A. Washington — said in a statement that they were unanimous in recommending that instead of building an AirTrain or extending a subway line to the airport, the Port Authority and the transportation authority should enhance existing Q70 bus service to the airport and add a dedicated shuttle between La Guardia and the last stop on the N/W subway line in Astoria.

The panel agreed that extending the subway to provide a “one-seat ride” from Midtown was “the optimal way to achieve the best mass transportation connection.” But they added that the engineers that reviewed the options could not find a viable way to build a subway extension to the cramped airport, which is hemmed in by the Grand Central Parkway and the East River.

Even if a way could be found to extend the subway that would not interfere with flight operations at La Guardia, the analysis concluded, it would take at least 12 years and cost as much as $7 billion to build.

The panel realized that the best option is an extension of the subway. Such an extension would be about 4.7 km long and around one third underground, or potentially around 5 km and entirely above-ground if for some reason tunneling under airport grounds were cost-prohibitive. This does not cost $7 billion, not even in New York. We know this, because Second Avenue Subway phase 1 was, in today’s money, around $2.2 billion per km, and phase 2 is perhaps a little more. There are standard subway : elevated cost ratios out there; the ones that emerge from our database tend to be toward the higher end perhaps, but still consistent with a ratio of about 2.5.

Overall, this is in theory pretty close to $7 billion for a one-third underground extension from Astoria to the airport. But in practice, the tunneling environment in question is massively easier than both phases of Second Avenue Subway – there’s plenty of space for cut-and-cover boxes in front of the terminal, a more controllable utilities environment, and not much development in the way of the elevated sections, which are mostly in an industrial zone to be redeveloped.

Does New York want to build?

New York can’t build. But to a significant extent, New York doesn’t even want to build. The report loves finding excuses why it’s not possible: they are squeamish about tunneling under the runways, they are worried an above-ground option would take lanes from the Grand Central Parkway (which a rail link would substitute for at higher capacity), they are worried about federal waivers.

In truth, in a constrained city, everything is under a waiver. In comments years ago, Richard Mlynarik pointed out that the desirable standard for railroad turnouts is that they should be straight – that is, the straight path should be on straight track, while the speed-restricted diverging path should curve away. But in practice, German train stations are full of curved turnouts, on which both paths are on a curve, because in a constrained urban zone it’s not possible to realize the desired standard, and a limit value is required. The same is true of any other engineering standard for a railroad, such as curve radii.

The issue of waivers is not limited to engineering or to rail. Roads are supposed to follow design standards, but land-constrained urban motorways are routinely on waivers. Even matters of safety can be grandfathered occasionally on a case-by-case basis. Financial and social standards are waived so often for urban megaprojects that it’s completely normal to decide them on a case-by-case basis; the United States doesn’t even have formal benefit-cost analyses the way Europe does.

And I’ve seen how American agencies are reluctant to even ask for waivers for things that politicians don’t really care about. Richard again brings up the example of platform heights on the San Francisco Peninsula: Caltrain rebuilt all platforms to a standard that didn’t have any level boarding, on the grounds that high platforms would interfere with oversize freight, which does not run on the line, and which the relevant state regulator, CPUC, indicated that they’d approve a waiver from if only the railroad asked. I have just seen an example of a plan to upgrade some stations in the Northeast that is running into trouble because the chosen construction material isn’t made in the United States, and even though “there’s no suitable made in America alternative” is legal grounds for a waiver from Buy America rules, the agency doesn’t so far seem interested in asking.

In general, New York can’t build. But in this case, it seems uninterested in even trying.

The bus alternative

Instead of a rail link, the plan now is to improve bus service. Here’s the New York Times story again:

The estimated $500 million in capital spending would also go toward creating dedicated bus lanes along 31st Street and 19th Avenue in Queens and making the Astoria-Ditmars Blvd. station on the N and W lines accessible to people with disabilities, the Port Authority said. Some of that money could also be spent to create a mile-long lane exclusive to buses on the northbound Brooklyn-Queens Expressway between Northern Boulevard and Astoria Boulevard, the Port Authority said.

Among the criticisms of the AirTrain plan was its indirect route. Arriving passengers bound for Manhattan would have had to travel in the opposite direction to catch a subway or L.I.R.R. train at Willets Point. The Port Authority chose that route, alongside the parkway, to minimize the need to acquire private property. Community groups were also concerned about the impact on property values in the neighborhoods near La Guardia in northern Queens.

To be very clear, it does not cost $500 million to make a station wheelchair-accessible. In New York, the average cost is around $70 million in 2021 dollars, with extensive contingency, planned by people who’d rather promise 70 and deliver 65 than promise 10 and deliver 12. In Madrid, the cost is around 10 million euros per station, with four elevators (the required minimum is three), and in Milan, shallow three-elevator station retrofits are around 2 million per station. Transfer stations cost more, proportionately to the number of lines served, but Astoria-Ditmars is not a transfer station and has no such excuse. So where is the other $430 million going?

The answer cannot just be bus lanes on 31st Street (on which the Astoria Line runs) or 19th Avenue (the industrial road the indicated extension on the map would run on). Bus lanes do not cost $430 million at this scale. They don’t normally cost anything – red paint and “bus only” markings are a rounding error, and bus shelter is $80,000 per stop with Californian cost control (to put things in perspective, I heard a $10,000-15,000 quote, in 2020 dollars, from a smaller American city).

The Issue of Curiosity

We’ve been talking to a lot of Americans in positions of power when it comes to transportation investment about our cost reports, and usually the conversations go well, but there’s one issue that keeps irking me. They ask good questions about corner cases, about some specific American problems (which we do want to revisit soon), about our prognosis for the future. But they don’t usually express curiosity about the non-American cases – and even journalists who write investigative pieces sometimes insist on only using London and Paris as proper comparanda for New York. This is not everyone, and I do know of some civil servants who are interested and have made sure to read the Italy, Stockholm or Istanbul cases. But it is a large majority of Americans we talk to, including ones who are clearly interested in doing better – even they think acquiring fluency in how things work in low-cost countries is irrelevant and are far more passionate about all the barely relevant groups that can block change than about how Stockholm, Milan, and other such cities build cost-effective infrastructure.

Incuriosity and consultants

I recently saw a transit manager in North America who I’d previously had tepidly positive opinion of tell me, with perfect confidence, that “The standard approach to construction in most of Europe outside Russia is design-build.”

To be very clear, this is bunk. Design-build is not used in Southern Europe or in the German-speaking world. Ant6n has only been able to find one such contract in Germany, for the signaling of Stuttgart 21. There’s more use of design-build in France, the Low Countries, and the Nordic countries, and the tendency is toward doing more of it, but,

- The process of privatization of the state is in its infancy in these countries – for example, Nya Tunnelbanan is mostly procured as build contracts

- Costs in the Nordic countries are rising rapidly, albeit from very low levels, and this also seems to be happening in France – this minority of Europe that uses design-build (which, again, correlates with other elements of state privatization) isn’t seeing good results

- As a consequence of the above two points, the current and former civil servants in those countries that I’ve spoken with are familiar with the more traditional system of project delivery and don’t generally think it is inferior to alternative systems that reduce the role of the state and increase that of private consultants, and thus they are familiar with how to do traditional project delivery well

- Even with the ongoing privatization of the Nordic and French states, more institutional knowledge is retained in the public sector, to ensure it can supervise the consultants, in contrast with the American and British models, where the consultants are supervised by other consultants and the in-house public-sector employees lack the technical knowledge to do proper oversight

So why did this person think design-build is standard, where the majority of Western Europe by population does not use it?

The answer is incuriosity. This person is a generalist Anglo consultant. What they know of Europe is what Anglo consultants know. They never stopped to think if perhaps places that build infrastructure cost-effectively publicly would ever have any reason to be legible to international English-speaking consultancies. Why would they? Infrastructure construction is almost entirely at the level of countries, not the European Union; the weakness of cross-border rail planning is so notable that I know a green activist devoted specifically to that issue. If you’re building in and for Germany, you have no real reason to publish in English trade journals or interact with British or American consultants. Another consultant that Eric and I spoke with had the insight to point out, when we asked about a comparison of High Speed 2 with the TGV, that their company gets no work in France since France does it in-house, but the transit manager who shall remain unnamed did not.

The good ones

I am sad to say that, for the most part, the mark of a good American transit manager, official, or regulator isn’t that they display real willingness to learn. Too few do. Rather, the mark is that they don’t say obviously false things with perfect confidence; they recognize their limits.

This is frustrating, because many of these people genuinely want to make things better – and at the federal level this even includes some political appointees rather than career civil servants. The typical cursus honorum for federal political appointees involves long stints doing policy analysis, usually in or near the topic they are appointed to, or running state- or city-level agencies; I criticize some of them for having failed in their previous jobs, but that’s not the same as the problem of a generalist overclass that jumps between entirely different fields and has no ability to properly oversee whichever field whose practitioners have had the misfortune to be subjected to its control.

The good ones ask interesting questions. Some are easy to answer, others are genuine challenges that require us to think about our approach more carefully. And yet, three things bother me.

They are not technical

Traditional American business culture looks down on technical experts, treating them as people who will forever work for a generalist manager – and this is a culture that treats working for someone else as a mark of inferiority.

The most innovative American industries don’t do this – software-tech and biotech both expect workers to be technical, and the line workers do not often respect managers who are technically illiterate; tech and biotech entrepreneurs likewise have a technical background (Mark Zuckerberg coded Facebook’s prototype, Noubar Afeyan is a biochemical engineering Ph.D., etc.), and Elon Musk, one of the less technical ones, still has a physics degree, wrote code in the 1990s, and goes to great pain to affect being part of the culture of tech workers.

However, the government at all levels does do this. The overclass comprises lawyers and public policy grads; engineers, architects, and planners can be trusted civil servants but are expected to lower their gaze in the presence of an elite lawyer (and one such lawyer told us, again with perfect confidence, something that not only was wrong, but was wrong about American law in their field).

The upshot is that even the good ones don’t ask technical questions. I don’t remember having had to answer questions from even the most curious American officials about grouting, about egress capacity, about ventilation, about construction techniques. It’s rare to even see economic questions about managing public-sector risk, about the required size of an in-house construction agency, about how one implements traditional project delivery effectively; we volunteer some numbers but I don’t remember being asked “how many engineers does RATP employ?” (the answer is around 1,200 across all fields combined).

They nudge and do not do

The American federal government is uncomfortable with the notion of doing things directly. One is supposed to make general rules and nudge others. Even regulations take a nudge form – often instead of direct compulsion (say, installing a safety system), the federal government would nudge private actors by threatening to withhold funds or other support if they don’t do it.

One consequence is that federal agencies don’t really try to learn how to do things themselves. I caution that one official who I spoke with and have a good impression of reacted well when I pointed out how, in Sweden, there’s mobility among the civil servants between state and county governments, so some of the people who built Citybanan working for the Swedish state are now building Nya Tunnelbanan for Stockholm County. This official said they were working on a program that doesn’t quite do this but does something similar, which stands to be successful if done well; I don’t know if it will be done well but there was not enough time in that conversation to get enough detail and I reserve judgment even on the aspects I am more pessimistic about until I know more. So it’s possible that this criticism I have of the federal government is going to do away in the next few years, and if so, I do expect better federal infrastructure investment, perhaps for intercity rail on the Northeast Corridor, which is a federal-led program.

This is not purely an American problem. The EU has the same problem, which is related to the poor state of cross-border rail; even when the European public wants more integration (see, for example, polling on an EU army), eurocrats respond with soporific abstraction, not out of political fear of backlash, but because none of them can actually do anything more than a light nudge – the doers remain at the member state level. The difference between us and the US is that member states like Germany do have some doers around, whereas New York can’t do anything.

They still only look inward

This is the part that I am most worried about in the future. I’ve had to take interesting questions about policy from people who, again, I think well of – if I didn’t, I’d speak of them the way I do of the official in the section on consultants above.

And then none of these questions is about, say, how Italy has set up its bureaucracy for protection of monuments, ensuring there is no risk to millennia-old Roman ruins under the aegis of professional archeologists and historians rather than third-party lawsuits. There’s ample interest among Americans in how to do better, reaching the highest levels among the people I’ve directly talked to, but so far it’s based entirely on internal thinking. Foreign examples can inform them but are not to be investigated as closely. I do know of some officials who’ve read the non-American reports we’ve put out, but it’s not common even among the good ones.

The problem, I think, is twofold. First, Americans are used to being in charge in their interactions with foreigners, and Western Europeans are about the least impressed people in the world by American pride. Why look up to a country that we know has worse public transportation and is, on net, probably about comparable in overall living standards? (Yes, Americans, I am aware that your SUVs are larger.) The average Western European doesn’t think about the United States much and when they do they’re not awed, so the American who asks questions puts themselves in an inferior position, and this is hard to handle.

The second issue is that the public sector draws from within the country’s borders, in almost all cases. The pipelines into working for Deutsche Bahn are completely different from those into working for any American outfit. This means that an official in a country has weak ties to other countries. This, again, is also a European problem – there’s too little knowledge of France in Germany and vice versa, too little curiosity about Southern Europe in higher-cost Northern Europe, and too little curiosity about Asia with disastrous results. But the European railroads have exchange programs among them and even with Japanese railroads, and Americans don’t participate in either; the insularity I see in Germany when I mention the capabilities of high-speed trains in France and Japan is considerably less bad than what I see among the worst Americans and Britons.

The RENFE Scandal and Responsibility

I’ve been repeatedly asked about a RENFE scandal about its rolling stock purchase. The company ordered trains too big for its rolling stock, and this has been amplified to a scandal that is said to be “incompetence beyond imagination” leading to several high-level resignations, including that of the ministry of transport’s chief civil servant, former ADIF head Isabel Pardo de Vera Posada. In reality, this is a real scandal but not a monumental one, and Pardo de Vera is not at fault; what it does show is both a culture of responsibility and a degree of political deflection.

What is the scandal?

RENFE, the state-owned Spanish rail operating firm, ordered regional trains for service in Asturias and Cantabria on a meter-gauge mountain railway with many narrow tunnels of nonstandard sizes. RENFE did not properly spec out the loading gauge, which vendor CAF noticed in 2021, shortly after the order was tendered but before manufacturing began; thereafter, both tried fixing the error, which has not led to any increase in cost, but has led to a delay in the entry of the under-construction equipment into service from 2024 to 2026.

The head of the regional government of Cantabria, Miguel Ángel Revilla Roiz, demanded that heads roll over the spectacular botch and delay. The context is that regional rail service outside Madrid and Barcelona has been steadily deteriorating, and people outside those two regions have long complained about the domination of the economy and society by those two cities and the depopulation of rural areas. Frequency is low and lines are threatened with closure due to the consequent poor ridership, and there is deep mistrust of the central government (a mistrust that is also common enough in Barcelona, where it is steered toward Catalan nationalism).

The other piece of context is the election at the end of this year. Nearly all polls have the right solidly defeating the incumbent PSOE; Revilla is a PSOE ally and so Asturias head Adrián Barbón Rodríguez is a PSOE member, and both are trying to save their political support by distinguishing themselves from the central government, which is unpopular due to the impact of corona on the Spanish economy.

What is Pardo de Vera’s role?

She was at ADIF when the contract came down; ADIF manages infrastructure, not operations. She was viewed as a consummate technocrat, and I became aware of her work through Roger Senserrich’s interview with her; as such, she was elevated to the position of secretary of state for transport, the chief civil servant in the ministry. Once the ministry became aware of the scandal in 2021, she tried to fix the contract, leading to the current result of a two-year delay; she is now under fire for not having been transparent with the public about it, as the story only became public after a local newspaper broke it.

This needs to be viewed not as incompetence on her part. The scandal is real, but moderate in scope; delays of this magnitude are unfortunately common, and Berlin is having one on the U-Bahn due to vendor lawsuits. Rather, the success of Spain in infrastructure procurement (if not in rail operations, where it unfortunately lags) has created high expectations. In the United States, where standards are the worst, a similar mistake by the MBTA in the ongoing process of procuring electric trains – the RFI did not properly specify the catenary height – is leading to actual increases in costs and it’s not even viewed as a minor problem as in Berlin but as just how expensive electrification is.

I urge Northern European and American agencies to reach out to Pardo de Vera. In Spain she may be perceived as scandalized, but she has real expertise in infrastructure construction, engineering, and procurement. Often boards, steering committees, and review panels comprise retired agency heads who left for a reason; she left for a reason that is not her fault.

How Failed Leaders Can Look Like Doers

Congratulations – you’ve finally finished a major project. The project was not done well – it cost too much and took too long. But somehow, the people responsible for the mess get to claim credit for success and are treated as great leaders who took tough decisions. Why?

The issue here is that poorly-executed projects look like great challenges. Maybe it’s a very short subway line that somehow cost like a multi-line megaproject. Maybe it’s a replacement-level city airport that took three times as long to build as anticipated. Maybe it’s a tank that’s only been used in parades even as the military is fighting a land war where it would be useful if it worked – a land war that is itself a major project even when the target is a poor country less than one third the population of yours. Maybe it’s a corporate IT project that’s dragged for so long that the software is almost out of support; this is far from a purely public-sector problem – every corporate manager and every person who’s worked for a corporate manager knows many such examples.

These are not, objectively speaking, huge challenges. Objectively speaking, Second Avenue Subway was 2.7 km of tunnel and three stations in a dense but not historic urban environment, under a straight avenue much wider than the width of a two-track tunnel with station platform, with no undercrossings of older subway tunnels, in conventional hard rock geology. A medium-cost city like Paris or Berlin would build this and a few other similar lines at once (to be fair, Berlin would probably be building other lines and not Second Avenue Subway, judging by its project prioritization). But New York can’t build, and therefore this 2.7 km tunnel is in today’s money a $6 billion project.

Once the project has been so mismanaged, it looks like something much bigger than it really is. It took many years and had a lot of administrative headaches (which were mostly self-inflicted). Its budget was so large that it was overseen at the highest levels of the government or corporation that built it, by heavyweight leaders who everyone in the organization has learned to lower their head around and who therefore don’t face serious criticism for their own poor decisionmaking. Those heavyweight leaders, insulated from what people really think of their competence level, then go ahead and portray themselves as doers, who managed to get such a difficult project done – when the only reason it was difficult is that they existed.

Good projects don’t have any of this. They look easy. They also tend to be small by local standards, because organizations expand to their limits, and so if you’re Paris and 200 km of Grand Paris Express are just beyond your managerial limit, you will still do that, and then those short Métro extensions of a few stations at a time look trivial and are beneath the notice of the political heavyweights who it’s impolite to speak in the company of.

Good project are also run by professionals who face regular, uncontrolled criticism, and not by heavyweights who surround themselves with lackeys and yes-men. So on top of looking easy, they also tend not to be run by the sort of toxic personality who having sabotaged the organization’s capacity then turn around and claim credit for the completion of the project. Manuel Melis Maynar knows exactly what his value is, but he’s an engineering professor rather than a marketing blowhard.

A better attitude than “at least they got [difficult-looking project] done” is then to look at the project’s true challenge – in the case of a subway it’s its length with some controls for undercrossings, network complexity, and the historic and geological sensitivity of the site. If the project was unduly expensive or lengthy for the challenge, those who claim credit for it are ideally to be treated as lepers rather than heroes, and should be replaced by people who were responsible for less telegenic but better-run comparanda. As always, it’s better to imitate success than to imitate failure.

Free Public Transport, Fare Integration, and Capacity

There’s an ongoing debate about free public transport that I’m going to get into later, but, for now, I want to zoom in on one aspect of the 9€ ticket, and how it impacted public transport capacity in Germany. A commenter on the Neoliberal Reddit group claimed that during the three months of nearly free public transport fares, there was a capacity crunch due to overuse. But in fact, the impact was not actually significant on urban rail, only on regional trains, in a way that underscores the importance of fare integration more than anything.

What was the 9€ ticket?

Last year, in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, fuel prices shot up everywhere. This created populist pressure to alleviate the price of fuel through temporary tax cuts, which further exacerbated last year’s high inflation. The center-right element within the German coalition, FDP, moved away from its traditional position as deficit scold and demanded a cut in the fuel tax; as a compromise, the Greens agreed to it on condition that during the three months of reduced fuel tax, June through August, public transport fares would be cut as well. Thus the 9€ monthly was born.

The 9€ ticket applied throughout Germany. The key feature wasn’t just the deep discount but also the fact that on one ticket, people could travel all over Germany; normally, my Berlin monthly doesn’t let me ride the local trains in Leipzig or Munich. This stimulated massive domestic tourism, since people could travel between cities on slow regional trains for free and then also travel around their destination city for free as well.

What now?

The 9€ ticket clearly raised public transport ridership in the three months it was in effect. This led to demands to make it permanent, running up against the problem that money is scarce and in Germany ticket fares generate a significant proportion of public transport revenue, 7.363 billion € out of 14.248 billion € in expenses (source, p. 36).

One partial move in that direction is a 29€ monthly valid only within Berlin, not in the suburbs (zone C of the S-Bahn) or outside the system; unlike the 9€ ticket, which was well-advertised all over national and local media and was available at every ticketing machine, the 29€ monthly is only available via annual subscription, which requires a permanent address in the city, and the regular machines only sell the usual 86€ monthly and don’t even let you know that a cheaper option exists. The subscription is also not available on a rolling basis – one must do it before the start of the month, which is not advertised, and Ant6n‘s family was caught unaware one month.

Negotiations for a nationwide 49€ ticket are underway, proceeding at the pace of a German train, or perhaps that of German arms deliveries to Ukraine. This was supposed to start at the beginning of 2023, then in April, and now it’s expected to debut in May. I’m assuming it will eventually happen – German trains get you there eventually, if hours late occasionally.

What’s the impact on capacity?

The U- and S-Bahn systems didn’t at all get overcrowded. They got a bit more crowded than usual, but nothing especially bad, since the sort of trips induced by zero marginal cost are off-peak. Rush hour commuters are not usually price-sensitive: whenever one’s alternative to the train is a car, the difference between a 9€ monthly and an 86€ one is a fraction of the difference between either ticket and the cost of owning and using a car, and at rush hour, cars are limited by congestion as well. Off-peak ridership did visibly grow, but not to levels that congest the system.

But then the hourly regional trains got completely overcrowded. If you wanted to ride the free trains from Berlin to Leipzig, you’d be standing for the last third of the trip. This is because the regional rail system (as opposed to S-Bahn) is designed as a low-capacity coverage-type system for connecting to small towns like Cottbus or Dessau.

The broader issue is that there is always a sharp ridership gradient between large cities and everywhere else, even per capita. In some places the gradient is sharper than elsewhere; the difference between New York and the rest of the United States is massive. But even in Germany, with a smaller gradient than one might be used to from France or the UK or Japan, public transport ridership is disproportionately dense urban or perhaps suburban, on trams and U- and S-Bahns.

The regional trains are another world. Really, European and Japanese trains can be thought of as three worlds: very high-use urban and suburban rail networks, high-use intercity rail connecting the main cities usually at high speed, and low-usage, highly-subsidized regional trains outside the major metropolitan regions. Germany has relatively good trains in the last category, if worse than in Switzerland, Austria, or the Netherlands: they run hourly with timed connections, so that people can connect between them to many destinations, they just usually don’t because cities the size of Dessau don’t generate a lot of ridership. The 9€ ticket gave people a free intercity trip if they chained trips on these regional trains, at the cost of getting to Leipzig in a little less than three hours rather than 1:15 on the ICE; the regional trains were not expanded to meet this surge traffic, which is usually handled on longer intercity trainsets, creating standing-room only conditions on trains where this should not happen off-peak or perhaps ever.

The issue of fare integration

The overcrowding seen on the regional trains last summer is really an issue of fare integration, which I hope is resolved as the 49€ gives people free trips on such trains permanently. A cornerstone of good public transport planning is that the fare between two points should be the same no matter what vehicle one uses, with exceptions only for first-class cars if available. Ein Ticket für alles, exclaims the system in Zurich, to great success. Anything else slices the market into lower-frequency segments, providing worse service than under total fare integration. Germany understands this – the Verkehrsverbund was invented in Hamburg in 1965, and subsequently this idea was adopted elsewhere until the country has been divided into metropolitan zones with internal fare integration.

The regional trains that cross Verkehrsverbund zones have their own fares, and normally that’s okay. Intercity trains were never part of this system, and that’s okay too – they’re not about one’s usual trip, and so an intercity ticket doesn’t include free transfers to local public transport unless one pays extra for that amenity. The fares between intercity trains and chains of regional trains were not supposed to be integrated, and normally that’s fine too, because any fare savings from chaining trips on slower trains are swamped both by the headache of buying so many tickets and by the difference in trip time and reliability.

The 9€ ticket broke that system, and the 49€ ticket will have the same effect: for three months, trips on slower trains were free, leading to overcrowding on a low-capacity network that normally isn’t that important to the country’s overall public transport system.

Worse, the operating costs of slow trains are higher than those of fast trains: they are smaller and so have a higher ratio of crew to passengers than ICEs, and their slowness means that crew and maintenance costs per kilometer are higher than those of fast trains. Even energy costs are higher on slow trains, because high-speed lines run at 300 km/h over long stretches, whereas regional lines make many stops (which had very little usage compared with the train’s volume of passengers last summer) and have slow zones rather than cruising at 130 or 160 km/h over long stretches. So the system gave people a price incentive to use the higher-cost trains and not the lower-cost ones.

This is the most important thing to resolve about any future fare reductions. Some mechanism is needed to ensure that the most advantageous way to travel between two cities is the one that DB can provide the most efficiently, which is IC/ICE and not RegionalBahn.

Paris-Berlin Trains, But no Infrastructure

Yesterday, Bloomberg reported that Macron and Scholz announced new train service between Paris and Berlin to debut next year, as intercity rail demand in Europe is steadily rising and people want to travel not just within countries but also between them. Currently, there is no direct rail service, and passengers who wish to travel on this city pair have to change trains in Frankfurt or Cologne. There’s just one problem: the train will not have any supportive infrastructure and therefore take the same eight hours that trains take today with a transfer.

This is especially frustrating, since Germany is already investing in improving its intercity rail. Unfortunately, the investments are halting and partial – right now the longest city pair connected entirely by high-speed rail is Cologne-Frankfurt, a distance of 180 km, and ongoing plans are going to close some low-speed gaps elsewhere in the system but still not create any long-range continuous high-speed rail corridor connecting major cities. With ongoing plans, Cologne-Stuttgart is going to be entirely fast, but not that fast – Frankfurt-Mannheim is supposed to be sped up to 29 minutes over about 75 km.

Berlin-Paris is a good axis for such investment. This includes the following sections:

- Berlin-Halle is currently medium-speed, trains taking 1:08-1:16 to do 162 km, but the flat, low-density terrain is easy for high-speed rail, which could speed this up to 40-45 minutes at fairly low cost since no tunnels and little bridging would be required.

- Halle-Erfurt is already fast, thanks to investments in the Berlin-Munich axis.

- Erfurt-Frankfurt is currently slow, but there are plans to build high-speed rail from Erfurt to Fulda and thence Hanau. The trip times leave a lot to be desired, but newer 300 km/h trains like the Velaro Novo, and perhaps a commitment to push the line not just to Hanau but closer to Frankfurt itself, could do this section in an hour.

- Frankfurt-Saarbrücken is very slow. Saarbrücken is at the western margin of Germany and is not significant enough by itself to merit any high-speed rail investment. Between it and Frankfurt, the terrain is rolling and some tunneling is needed, and the only significant intermediate stops are Mainz (close enough to Frankfurt it’s a mere stop of opportunity) and Kaiserslautern. Nonetheless, fast trains could get from Frankfurt to the border in 45 minutes, whereas today they take two hours.

Unfortunately, they’re not talking about any pan-European infrastructure here. Building things is too difficult, so instead the plan is to run night trains – this despite the fact that Frankfurt-Saarbrücken with a connection to the LGV Est would make a great joint project.

Bad Public Transit in the Third World

There’s sometimes a stereotype that in poor countries with low car ownership, alternatives to the car are flourishing. I saw a post on Mastodon making this premise, and pointed out already in comments that this is not really true. This is a more detailed version of what I said in 500 characters. In short, in most of the third world, non-car transportation is bad, and nearly all ridership (on jitneys and buses) is out of poverty, as is most walking. While car ownership is low, the elites who do own cars dominate local affairs, and therefore cities are car-dominated and not at all walkable, even as 90%+ of the population does not own a car.

What’s more, the developing countries that do manage to build good public transportation don’t stay developing for long. The same development model of Japan, the East Asian Tigers, and now China has built both rail-oriented cities and high economic growth, to the point that Japan and the Tigers are fully developed, and China is a solidly middle-income economy. The sort of places that stay poor, or get stuck in a middle-income trap, also tend to have stagnant urban rail networks, and so grow more auto-oriented over time.

The situation in Southeast Asia

With the exception of Singapore, nowhere in Southeast Asia is public transit good. What’s more, construction costs have been high for elevated lines and very high for underground ones, slowing down the construction of metro systems.

In Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok, motorization is high and public transit usage is weak. Paul Barter’s thesis details how both cities got this way, in comparison with the more transit-oriented model used in Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong, and Singapore. The thesis also predicts that the poorer megacities of Southeast Asia – Jakarta and Manila – will follow the auto-oriented path as they develop, which has indeed happened in the 13 years since it was written.

The situation in those cities is, to be fair, murky. Manila has a large urban rail under construction right now, with average to above average costs for elevated lines and high ones for subways. But the system it has today consists of four lines, two branded light rail, one branded MRT, and one commuter line. In 2019, the six-month ridership on the system was 162 million. A total of 324 million in a metro area the size of Manila is extraordinarily low: the administrative Metro Manila region has 13.5 million people, and the urban or metropolitan area according to both Citypopulation.de and Demographia is 24-26 million. On the strictest definition of Metro Manila, this is 24 trips per person per year; on the wider ones, it is about 13, similar to San Diego or Portland and only somewhat better than Atlanta.

Jakarta is in the same situation of flux. It recently opened a half-underground MRT line at fairly high cost, and is modernizing its commuter rail network along Japanese lines, using second-hand Japanese equipment. Commuter rail ridership was 1.2 million a day last year, or around 360 million a year, already higher than before corona; the MRT had 20 million riders last year, and an airport link had 1.5 million in 2018. This isn’t everything – there’s also a short light metro called LRT for which I can’t find numbers – but it wouldn’t be more than second-order. This is 400 million annual rail trips, in a region of 32 million people.

The future of these cities is larger versions of Bangkok. Thailand is sufficiently middle-income that we can see directly how its transport system evolves as it leaves poverty, and the results are not good. Bus ridership is high, but it’s rapidly falling as anyone who can afford a car gets one; a JICA report about MRT development puts the region’s modal split at 5% MRT, 36% bus, and the rest private (PDF-p. 69) – and the income of bus riders is significantly lower than that of drivers (PDF-p. 229), whereas MRT riders are closer to drivers.

Even wealthier than Bangkok, with the same auto-oriented system, is Kuala Lumpur. There, the modal split is about 8% bus, 7% train, and the rest private. This is worse than San Francisco and the major cities of Canada and Australia, let alone New York or any large European city. The national modal split in England, France, Germany, and Spain is about 16% – the first three countries’ figures predate corona, but in Spain they’re from 2021, with suppressed public transport ridership. Note that rail ridership per capita is healthier in Kuala Lumpur than in Jakarta or Manila – all rail lines combined are 760,000 riders per day, say 228 million per year, in a region of maybe 7 million people. This is better than a no-transit American city like San Diego, but worse than a bad-transit one like Chicago or Washington, where the modal split is about the same but there is no longer the kind of poverty that is common in Malaysia, let alone in Indonesia, and therefore if people ride the trains it’s because they get them to their city center jobs and not because they’re poor.

Even in Singapore, the best example out there of a transit-oriented rich city, it took until very recently for MRT coverage to be good enough that people willingly depend on it; it only reached NUS after I graduated. In the 1990s, the epitome of middle-class Singaporean materialism was described as owning the Five Cs, of which one was a car; traffic suppression, a Paul Barter describes, has centered fees on cars, much more car purchase than car use (despite the world-famous congestion pricing system), and thus to those wealthy enough to afford cars, they’re convenient in ways they are not in Paris, Berlin, or Stockholm.

The situation in Africa

African countries between the Sahara and the Kalahari are all very poor, with low car ownership. However, they are thoroughly car-dominated.

From the outside, it’s fascinating to see how the better-off countries in that region, like Nigeria, are already imitating Southeast Asia. Malaysia overregulated its jitneys out of existence because they were messy and this bothered elites, and because it wanted to create an internal market for its state-owned automakers. Nigeria is doing the same, on the former grounds; to the extent it hasn’t happened despite years of trying, it’s because the state is too weak to do more than harass the drivers and users of the system.

It’s notable that the Lagos discourse about the evils of the danfo – they are noisy, they are polluting, they drive like maniacs – there is little attention to how cars create all the same problems, except at larger scale per passenger served. The local notables drive (or are driven); the people who they scorn as unwashed, overly fecund, criminal masses ride the danfo. Thanks to aggressive domination by cars and inattention to the needs of the non-driving majority, Lagos’s car ownership is high for how poor it is – one source from 2017 says 5 million cars in the state, another from 2021 says 6.5 million vehicles between the state and Kano State. The denominator population in the latter source is 27 million officially, but unofficially likely more; 200 vehicles per 1,000 people is plausible for Lagos, which to be clear is not much less than New York or Paris, on an order of magnitude lower GDP per capita. Tokyo took until about 1970 to reach 100 vehicles per 1,000 people, at which point Japan had almost fully converged with American GDP per capita.

This is not specific to Lagos. A cousin who spent some time in Kampala told me of the hierarchy on the roads: pedestrians fear motorcycles, motorcycles fear cars, cars fear trucks. There is no pedestrian infrastructure to speak of; a rapid transit system is still a dream, to the point that a crayon proposal that spread on Twitter made local media. That the vast majority of Ugandans don’t own cars doesn’t matter; Kampala remains dominated by the few who do.

Transit and development

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the sort of developing countries that build successful urban rail systems don’t stay poor for long. Part of it is that public transportation is good for economic development, but that’s not most of it – the United States manages to be rich without it except in a handful of cities. Rather, I suspect the reason has to do with state capacity.

More specifically, the reason cities with 100-200 cars per 1,000 people are thoroughly dominated by cars is that those 10-20% drivers (or people who are driven) are the elites. Their elite status can come from any source – passive business income, landlordism, active business income, skilled professional work – but usually it tilts toward the traditional, i.e. passive. These groups tend to be incredibly anti-developmental: they own small businesses, sometimes actively and sometimes passively, and resent being made redundant through economies of scale. India has problems with economic dwarfism and informality, and this is typical of poor countries; if anything, India is better than most at developing a handful of big businesses in high-value added industries.

The upshot is that the sort of people who drive, and especially the sort of drivers who are powerful enough to effect local changes to get incremental upgrades to roads at the expense of non-drivers, are usually anti-developmental classes. The East Asian developmental states (and Singapore and Hong Kong, which share many characteristics with them) clamped down on such classes hard, on either nationalist or socialist grounds; Japan, both Koreas, and both Chinas engaged in land reform, with characteristic violence in the two socialist states and without it but still with forcible purchase in the three capitalist states. The same sort of state that can eliminate landlordism can also, as a matter of capital formation, clamp down on consumption and encourage personal savings, producing atypically low levels of motorization well into middle-income status. Singapore, whose elite consumption centers vacations out of the country, has managed to do so even as a high-income country – and even more normal Tokyo and Seoul have much higher rail usage and lower car usage than their closest Western analog, New York.

India is in many ways anti-developmental, but it does manage to grow. Its anti-developmentalism is anti-urban and NIMBY, but it is capable of building infrastructure. Its metro program has problems with high construction costs (but Southeast Asia’s are generally worse) and lack of integration with other modes such as commuter rail, which the middle class denigrates as only befitting poor people; but the Delhi Metro had 5.5 million daily riders just before corona, slightly behind New York in a slightly larger metro area, perhaps a better comparison than Jakarta and Manila’s San Diego.

It’s the slower-growing developing countries that are not managing to even build the systems India has, let alone East Asia. They don’t have high car use, but only because they are poor, and in practice, they are thoroughly car-dominated, and everyone who doesn’t have a car wants one. A rich country really is not one where even the poor have cars but where even the rich use public transportation – and those countries aren’t rich and don’t grow at rates that will make them rich.

Schedule Planners as a Resource

The Effective Transit Alliance published its statement on Riders Alliance’s Six-Minute Service campaign, which proposes to run every subway line in New York and the top 100 bus routes every (at worst) six minutes every day from morning to evening. We’re positive on it, even more than Riders Alliance is. We go over how frequency benefits riders, as I wrote here and here, but also over how it makes planning easier. It is the latter benefit I want to go over right now: schedule planning staff is a resource, just as drivers and outside capital are, and it’s important for transit agencies to institute systems that conserve this resource and avoid creating unnecessary work for planners.

The current situation in New York

Uday Schultz writes about how schedule planning is done in New York. There’s an operations planning department, with 350 budgeted positions as of 2021 of which 284 are filled, down from 400 and 377 respectively in 2016. The department is responsible for all aspects of schedule planning: base schedules but also schedules for every service change (“General Order” or GO in short).

Each numbered or lettered route is timetabled on it own. The frequency is set by a guideline coming from peak crowding: at any off-peak period, at the most crowded point of a route, passenger crowding is supposed to be 25% higher than the seated capacity of the train; at rush hour, higher standee crowding levels are tolerated, and in practice vary widely by route. This way, two subway routes that share tracks for a long stretch will typically have different frequencies, and in practice, as perceived by passengers, off-peak crowding levels vary and are usually worse than the 25% standee factor.

Moreover, because planning is done by route, two trains that share tracks will have separate schedule plans, with little regard for integration. Occasionally, as Uday points out, this leads to literally impossible schedules. More commonly, this leads to irregular gaps: for example, the E and F trains run at the same frequency, every 4 minutes peak and every 12 minutes on weekends, but on weekends they are offset by just 2 minutes from each other, so on the long stretch of the Queens Boulevard Line where they share the express tracks, passengers have a 2-minute wait followed by a 10-minute wait.

Why?

The current situation creates more work for schedule planners, in all of the following ways:

- Each route is run on its own set of frequencies.

- Routes that share tracks can have different frequencies, requiring special attention to ensure that trains do not conflict.

- Each period of day (morning peak, midday, afternoon peak, evening) is planned separately, with transitions between peak and off-peak; there are separate schedules for the weekend.

- There are extensive GOs, each requiring not just its own bespoke timetable but also a plan for ramping down service before the start of the GO and ramping it up after it ends.

This way, a department of 284 operations planners is understaffed and cuts corners, leading to irregular and often excessively long gaps between trains. In effect, managerial rules for how to plan trains have created makework for the planners, so that an objectively enormous department still has too much work to do and cannot write coherent schedules.

Creating less work for planners

Operations planners, like any other group of employees, are a resource. It’s possible to get more of this resource by spending more money, but office staff is not cheap and American public-sector hiring has problems with uncompetitive salaries. Moreover, the makework effect doesn’t dissipate if more people are hire – it’s always possible to create more work for more planners, for example by micromanaging frequency at ever more granular levels.

To conserve this resource, multiple strategies should be used:

Regular frequencies

If all trains run on the same frequency all day, there’s less work to do, freeing up staff resources toward making sure that the timetables work without any conflict. If a distinction between peak and base is required, as on the absolute busiest routes like the E and F, then the base should be the same during all off-peak periods, so that only two schedules (peak and off-peak) are required with a ramp-up and ramp-down at the transition. This is what the six-minute service program does, but it could equally be done with a more austere and worse-for-passengers schedule, such as running trains every eight minutes off-peak.

Deinterlining

Reducing the extent of reverse-branching would enable planning more parts of the system separately from one another without so much conflict. Note that deinterlining for the purposes of good passenger service has somewhat different priorities from deinterlining for the purposes of coherent planning. I wrote about the former here and here. For the latter, it’s most important to reduce the number of connected components in the track-sharing graph, which means breaking apart the system inherited from the BMT from that inherited from the IND.

The two goals share a priority in fixing DeKalb Avenue, so that in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, the B and D share tracks as do the N and Q (today, in Brooklyn, the B shares track with the Q whereas the D shares track with the N): DeKalb Junction is a timetabling mess and trains have to wait two minutes there for a slot. Conversely, the main benefit of reverse-branching, one-seat rides to more places, is reduced since the two Manhattan trunks so fed, on Sixth Avenue and Broadway, are close to each other.

However, to enable more convenient planning, the next goal for deinterlining must be to stop using 11th Street Connection in regular service, which today transitions the R from the BMT Broadway Line and 60th Street Tunnel to the IND Queens Boulevard local tracks. Instead, the R should go where Broadway local trains go, that is Astoria, while the Broadway express N should go to Second Avenue Subway to increase service there. The vacated local service on Queens Boulevard should go to IND trunks in Manhattan, to Eighth or Sixth Avenue depending on what’s available based on changes to the rest of the system; currently, Eighth Avenue is where there is space. Optionally, no new route should be added, and instead local service on Queens Boulevard could run as a single service (currently the M) every 4 minutes all day, to match peak E and F frequencies.

GO reform

New York uses too many GOs, messing up weekend service. This is ostensibly for maintenance and worker safety, but maintenance work gets done elsewhere with fewer changes (as in Paris or Berlin) or almost none (as in Tokyo) – and Berlin and Tokyo barely have nighttime windows for maintenance, Tokyo’s nighttime outages lasting at most 3-4 hours and Berlin’s available only five nights a week. The system should push back against ever more creative service disruptions for work and demand higher maintenance productivity.

The Official Brooklyn Bus Redesign is Out

The MTA just released a draft of the Brooklyn bus redesign it and its consultant had been working on. It is not good. I’m not completely sure why this is – the Queens redesign was a good deal better, and our take on it at the Effective Transit Alliance was decidedly positive. But in the case of Brooklyn, the things that worked in Queens are absent. Overall, the theme of this is stasis – the changes to the network are minor, and the frequencies are to remain insufficiently low for good service. The only good thing about this is stop consolidation, which does not require spending any money on consultants and is a straightforward fix.

This is especially frustrating to me because my first project for Marron, before the Transit Costs Project, was a redesign proposal. The proposal can be read here, with discussion in blog posts here, here, and here. The official reaction we got was chilly, but the redesign doesn’t look anything like a more politic version, just one produced at much higher consultant cost while doing very little.

The four-color scheme

The Brooklyn project retains the Queens redesign’s four-color scheme of buses, to be divided into local (green), limited (red), Select Bus Service (blue), and rush (purple). The local buses are supposed to stop every 300-400 meters, which is not the best (the optimum for Brooklyn is about 400-500) but is a good deal better than the current spacing of about 200-250. The other three kinds of buses are more express, some running on the same routes as local buses as express overlays and some running on streets without local service.

In Queens, this four-way distinction emerges from the pattern in which in neighborhoods beyond the subway’s reach, bus usage is extremely peaky toward the subway. The purpose of the rush route is to get people to the subway terminal, such as Flushing or Jamaica, with not just longer stop spacing but also long nonstop sections close to the terminal where local service exists as an overlay, imitating the local and express patterns of peaky commuter rail operations in New York. I still think it’s not a good idea and buses should run at a more uniform interstation at higher frequency. But over the long stretches of Eastern Queens, the decision is fairly close and while rush routes are not optimal, they’re not much worse than the optimum. In contrast, Brooklyn is nothing like Queens: people travel shorter distances, and long routes are often used as circumferential subway connectors with ample turnover.

Ironically, this is something the MTA and its consultants understood: the Brooklyn map is largely green, whereas that in Queens has a more even mix of all four colors. Nonetheless, some rush routes are retained and so are some limited-only routes, in a way that subtracts value: if nearly all buses in Brooklyn offer me something, I should expect it on the other buses as well, whereas the rush-only B26 on Halsey Street is different in a way that isn’t clear.

In general, the notable feature of our redesign, unlike the more common American ones, is that there is no distinction among the different routes. Some are more frequent than others, but all have very high base frequency. This is because Brooklyn has unusually isotropic travel: density decreases from the East River south- and eastward, but the subway network also thins out and these effects mostly cancel out, especially with the high density of some housing projects in Coney Island; the busiest buses include some running only within Southern Brooklyn, like the B6 and B82 circumferentials.

In contrast, small-city redesigns tend to occur in a context with a strong core network and a weak peripheral network (“coverage routes,” which exist to reassure loud communities with no transit ridership that they can get buses too), and the redesign process tends to center this distinction and invest in the stronger core network. Queens has elements that look like this, if you squint your eyes sufficiently. Brooklyn has none: the isotropic density of most of the borough ensures that splitting buses into separate classes is counterproductive.

Frequency

The frequency in the proposed system is, frankly, bad. The MTA seems to believe that the appropriate frequency for urban mass transit is a train or bus every 10 minutes. This is acceptable in the suburban neighborhoods of Berlin or the outermost parts of New York, like the Rockaways and the eastern margin of Queens. In denser areas, including all of Brooklyn, it is not acceptable. People travel short distances: citywide, the average trip distance before corona was 3.4 km, which works out to 18 minutes at average New York bus speed (source: NTD 2019). In Brooklyn, the dense mesh of buses going between subway lines rather than to them makes the average even slightly lower. This means that very high frequency is a high priority.

So bad is the MTA’s thinking about frequency that core routes in the borough are split into local and limited variants, each running every 10 minutes off-peak, including some of the busiest corridors in the borough, like the outer circumferential B6 and B82 and the more inner-circumferential B35 on Church (split in the plan into a local B35 and an SBS B55). This is not changed from the current design, even though it’s easy to do so in the context of general consolidation of stops.

To make this even worse, there does not appear to be any increase in service-km, judging by the plan’s lack of net increase in frequency. This is bad planning: bus operating costs come from time (driver’s wage, mainly) and not distance, and the speedup provided by the stop consolidation should fuel an increase in frequency.

The Battery Tunnel

The most annoying aspect, at least to me, is the lack of a bus in the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, connecting Manhattan with Red Hook. Red Hook is isolated from the subway and from the rest of Brooklyn thanks to the freeway, and has bus connections only internally to Brooklyn where in fact a short bus route through the tunnel would beat bus-subway connections to Lower Manhattan.

We got the idea for the inclusion of such a bus service from planners that we spoke to when we wrote our own redesign. The service is cheap to provide because of the short length of the route, and would complement the rest of the network. It was also popular in the neighborhood meetings that tee consultants ran, we are told. And yet, it was deleted on a whim.