New York is asking for $20 billion for reconstruction ($7 billion) and physical expansion ($13 billion) of Penn Station. The state is treating it as a foregone conclusion that it will happen and it will get other people’s money for it; the state oversight board just voted for it despite the uncertain funding. Facing criticism from technical advocates who have proposed alternatives that can use Penn Station’s existing infrastructure, lead agency Empire State Development (ESD) has pushed back. The document I’ve been looking at lately is not new – it’s a presentation from May 2021 – but the discussion I’ve seen of it is. The bad news is that the presentation makes fraudulent claims about the capabilities of railroads in defense of its intention to waste $20 billion, to the point that people should lose their jobs and until they do federal funding for New York projects should be stingier. The good news is that this means that there are no significant technical barriers to commuter rail modernization in New York – the obstacles cited in the presentation are completely trivial, and thus, if billions of dollars are available for rail capital expansion in New York, they can go to more useful priorities like IBX.

What’s the issue with Penn Station expansion?

Penn Station is a mess at both the concourse and track levels. The worst capacity bottleneck is the western approach across the river, the two-track North River Tunnels, which on the eve of corona ran about 20 overfull commuter trains and four intercity trains into New York at the peak hour; the canceled ARC project and the ongoing Gateway project both intend to address this by adding two more tracks to Penn Station.

Unfortunately, there is a widespread belief that Penn Station’s 21 existing tracks cannot accommodate all traffic from both east (with four existing East River Tunnel tracks) and west if new Hudson tunnels are built. This belief goes back at least to the original ARC plans from 20 years ago: all plans involved some further expansion, including Alt G (onward connection to Grand Central), Alt S (onward connection to Sunnyside via two new East River tunnel tracks), and Alt P (deep cavern under Penn Station with more tracks). Gateway has always assumed the same, calling for a near-surface variation of Alt P: instead of a deep cavern, the block south of Penn Station, so-called Block 780, is to be demolished and dug up for additional tracks.

The impetus for rebuilding Penn Station is a combination of a false belief that it is a capacity bottleneck (it isn’t, only the Hudson tunnels are) and a historical grudge over the demolition of the old Beaux-Arts station with a labyrinthine, low-ceiling structure that nobody likes. The result is that much of the discourse about the need to rebuild the station is looking for technical justification for an aesthetic decision; unfortunately, nobody I have talked to or read in New York seems especially interested in the wayfinding aspects of the poor design of the existing station, which are real and do act as a drag on casual travel.

I highlight the history of Penn Station and the lead agency – ESD rather than the MTA, Port Authority, or Amtrak – because it showcases how this is not really a transit project. It’s not even a bad transit project the way ARC Alt P was or the way Gateway with Block 780 demolition is. It’s an urban renewal project, run by people who judge train stations by which starchitect built them and how they look in renderings rather than by how useful they are for passengers. Expansion in this context is about creating the maximum footprint for renderings, and not about solving a transportation problem.

Why is it believed that Penn Station needs more tracks?

Penn Station tracks are used inefficiently. The ESD pushback even hints at why, it just treats bad practices as immutable. Trains have very long dwell times: per p. 22 of the presentation, the LIRR can get in and out in a quick 6 minutes, but New Jersey Transit averages 12 and Amtrak averages 22. The reasons given for Amtrak’s long dwell are “baggage” (there is no checked baggage on most trains), “commissary” (the cafe car is restocked there, hardly the best use of space), and “boarding from one escalator” (this is unnecessary and in fact seasoned travelers know to go to a different concourse and board there). A more reasonable dwell time at a station as busy as Penn Station on trains designed for fast access and egress is 1-2 minutes, which happens hundreds of times a day at Shin-Osaka; on the worse-designed Amtrak rolling stock, with its narrower doors, 5 minutes should suffice.

New Jersey Transit can likewise deboard fast, although it might need to throw away the bilevels and replace them with longer single-deck trains. This reduces on-board capacity somewhat, but this entire discussion assumes the Gateway tunnel has been built, otherwise even present operations do not exhaust the station’s capacity. Moreover, trains can be procured for comfortable standing; subway riders sometimes have to stand for 20-30 minutes and commuter rail riders should have similar levels of comfort – the problem today is standees on New Jersey Transit trains designed without any comfortable standing space.

But by far the biggest single efficiency improvement that can be done at Penn Station is through-running. If trains don’t have to turn back or even continue to a yard out of service, but instead run onward to suburbs on the other side of Manhattan, then the dwell time can be far less than 6 minutes and then there is much more space at the station than it would ever need. The station’s 21 tracks would be a large surplus; some could be removed to widen the platform, and the ESD presentation does look at one way to do this, which isn’t necessarily the optimal way (it considers paving over every other track to widen the platforms and permit trains to open doors on both sides rather than paving over every other track pair to widen the platforms much more but without the both-side doors). But then the presentation defrauds the public on the opportunity to do so.

Fraudulent claim #1: 8 minute dwells

On p. 44, the presentation compares the capacity with and without through-running, assuming half the tracks are paved over to widen the platforms. The explicit assumption is that through-running commuter rail requires trains to dwell 8 minutes at Penn Station to fully unload and load passengers. There are three options: the people who wrote this may have lied, or they may be incompetent, or they be both liars and incompetent.

In reality, even very busy stations unload and load passengers in 30-60 seconds at rush hour. Limiting cases reaching up to 90-120 seconds exist but are rare; the RER A, which runs bilevels, is the only one I know of at 105.

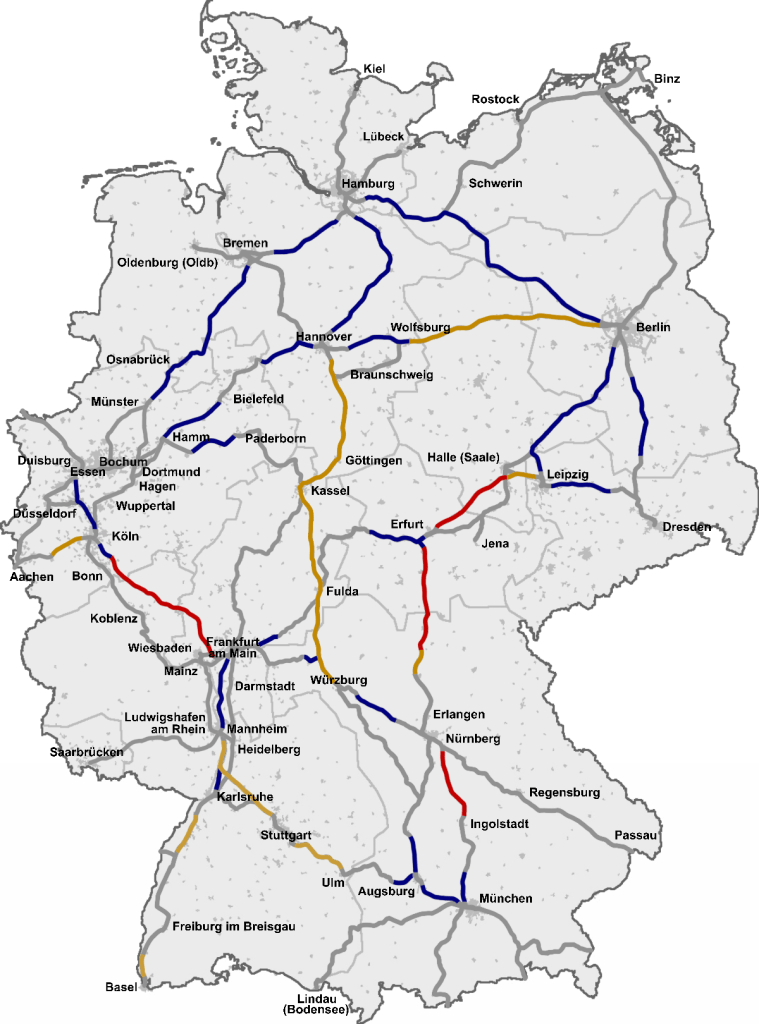

On pp. 52-53, the presentation even shows a map of the central sections of the RER, with the central stations (Gare du Nord, Les Halles, and Auber/Saint-Lazare) circled. There is no text, but I presume that this is intended to mean that there are two CBD stations on each line rather than just one, which helps distribute the passenger load better; in contrast, New York would only have one Manhattan station on through-trains on the Northeast Corridor, which requires a longer dwell time. I’ve heard this criticism over the years from official and advocate sources, and I’m sympathetic.

What I’m not sympathetic to is the claim that the dwell time required at Penn Station is more than the dwell time required at multiple city center stations, all combined. On the single-deck RER B, the combined rush hour dwell time at Gare du Nord and Les Halles is around 2 minutes normally (and the next station over, Saint-Michel, has 40-60 second rush hour dwells and is not in the CBD unless you’re an academic or a tourist); in unusual circumstances it might go as high as 4 minutes. The RER A’s combined dwell is within the same range. In Munich, there are six stations on the S-Bahn trunk between Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof – but at the intermediate stations (with both-sides door opening) the dwell times are 30 seconds each and sometimes the doors only stay open 20 seconds; Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof have longer dwell times but are not busier, they just are used as control points for scheduling.

The RER A’s ridership in 2011 was 1.14 million trips per weekday (source, p. 22) and traffic was 30 peak trains per hour and 24 reverse-peak trains; at the time, dwell times at Les Halles and Auber were lower than today, and it took several more years of ridership growth for dwell times to rise to 105 seconds, reducing peak traffic to 27 and then 24 tph. The RER B’s ridership was 983,000 per workday in 2019, with 20 tph per direction. Munich is a smaller city, small enough New Yorkers may look down on it, but its single-line S-Bahn had 950,000 trips per workday in 2019, on 30 peak tph in each direction. In contrast, pre-corona weekday ridership was 290,000 on the LIRR, 260,000 on Metro-North, and around 270,000 on New Jersey Transit – and the LIRR has a four-track tunnel into Manhattan, driving up traffic to 37 tph in addition to New Jersey’s 21. It’s absurd that the assumption on dwell time at one station is that it must be twice the combined dwell times at all city center stations on commuter lines that are more than twice as busy per train as the two commuter railroads serving Penn Station.

Using a more reasonable figure of 2 minutes in dwell time per train, the capacity of through-running rises to a multiple of what ESD claims, and through-running is a strong alternative to current plans.

Fraudulent claim #2: no 2.5% grades allowed

On pp. 38-39, the presentation claims that tracks 1-4 of Penn Station, which are currently stub-end tracks, cannot support through-running. In describing present-day operations, it’s correct that through-running must use the tracks 5-16, with access to the southern East River Tunnel pair. But it’s a dangerously false assumption for future infrastructure construction, with implications for the future of Gateway.

The rub is that the ARC alternatives that would have continued past Penn Station – Alts P and G – both were to extend the tunnel east from tracks 1-4, beneath 31st Street (the existing East River Tunnels feed 32nd and 33rd). Early Gateway plans by Amtrak called for an Alt G-style extension to Grand Central, with intercity trains calling at both stations. There was always a question about how such a tunnel would weave between subway tunnels, and those were informally said to doom Alt G. The presentation unambiguously answers this question – but the answer it gives is the exact opposite of what its supporting material says.

The graphic on p. 39 shows that to clear the subway’s Sixth Avenue Line, the trains must descend a 2.45% grade. This accords with what I was told by Foster Nichols, currently a senior WSP consultant but previously the planner who expanded Penn Station’s lower concourse in the 1990s to add platform access points and improve LIRR circulation, thereby shortening LIRR dwell times. Nichols did not give the precise figure of 2.45%, but did say that in the 1900s the station had been built with a proviso for tracks under 31st, but then the subway under Sixth Avenue partly obstructed them, and extension would require using a grade greater than 2%.

The rub is that modern urban and suburban trains climb 4% grades with no difficulty. The subway’s steepest grade, climbing out of the Steinway Tunnel, is 4.5%, and 3-3.5% grades are routine. The tractive effort required can be translated to units of acceleration: up a 4% grade, fighting gravity corresponds to 0.4 m/s^2 acceleration, whereas modern trains do 1-1.3 m/s^2. But it’s actually easier than this – the gradient slopes down when heading out of the station, and this makes the grade desirable: in fact, the subway was built with stations at the top of 2.5-3% grades (for example, see figure 7 here) so that gravity would assist acceleration and deceleration.

The reason the railroaders don’t like grades steeper than 2% is that they like the possibility of using obsolete trains, pulled by electric locomotives with only enough tractive effort to accelerate at about 0.4 m/s^2. With such anemic power, steeper grades may cause the train to stall in the tunnel. The solution is to cease using such outdated technology. Instead, all trains should be self-propelled electric multiple units (EMUs), like the vast majority of LIRR and Metro-North rolling stock and every subway train in the world. Japan no longer uses electric locomotives at all on its day trains, and among the workhorse European S-Bahn systems, all use EMUs exclusively, with the exception of Zurich, which still has some locomotive-pulled trains but is transitioning to EMUs.

It costs money to replace locomotive-hauled trains with EMUs. But it doesn’t cost a lot of money. Gateway won’t be completed tomorrow; any replacement of locomotives with EMUs on the normal replacement cycle saves capital costs rather than increasing them, and the same is true of changing future orders to accommodate peak service expansion for Gateway. Prematurely retiring locomotives does cost money, but New Jersey Transit only has 100 electric locomotives and 29 of them are 20 years old at this point; the total cost of such an early retirement program would be, to first order, about $1 billion. $1 billion is money, but it has independent transportation benefits including faster acceleration and higher reliability, whereas the $13 billion for Penn Station expansion have no transportation benefits whatsoever. Switzerland may be a laggard in replacing the S-Bahn’s locomotives with EMUs, but it’s a leader in the planning maxim electronics before concrete, and when the choice is between building a through-running tunnel for EMUs and building a massive underground station to store electric locomotives, the correct choice is to go with the EMUs.

How do they get away with this?

ESD is defrauding the public. The people who signed their names to the presentation should most likely not work for the state or any of its contractors; the state needs honest, competent people with experience building effective mass transit projects.

Those people walk around with their senior manager titles and decades of experience building infrastructure at outrageous cost and think they are experts. And why wouldn’t they? They do not respect any knowledge generated outside the New York (occasionally rest-of-US) bubble. They think of Spain as a place to vacation, not as a place that built 150 kilometers of subway 20 years ago for the same approximate cost as Second Avenue Subway phases 1 and 2. They think of smaller cities like Milan as beneath their dignity to learn about.

And what’s more, they’ve internalized a culture of revealing as little as possible. That closed attitude has always been there; it’s by accident that they committed two glaring acts of fraud to paper with this presentation. Usually they speak in generalities: the number of people who use the expression “apples-to-apples” and provide no further detail is staggering. They’ve learned to be opaque – to say little and do little. Most likely, they’re under political pressure to make the Penn Station reconstruction and expansion look good in order to generate what the governor thinks are good headlines, and they’ve internalized the idea that they should make up numbers to justify a political project (and in both the Transit Costs Project and previous reporting I’d talked to people in consulting who said they were under such formal or informal pressure for other US projects).

The way forward

With too much political support for wasting $20 billion at the state level, the federal government should step in and put an end to this. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) has $66 billion for mainline rail; none of this money should go to Penn Station expansion, and the only way any money should go to renovation is if it’s part of a program for concrete improvement in passenger rail function. If New York wishes to completely remodel the platform level, and not just pave over every other track or every other track pair, then federal support should be forthcoming, albeit not for $7 billion or even half that. But it’s not a federal infrastructure priority to restore some kind of social memory of the old Penn Station. Form follows function; beautiful, airy train stations that people like to travel through have been built under this maxim, for example Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

To support good rail construction, it’s obligatory that experts be put in charge – and there aren’t any among the usual suspects in New York (or elsewhere in the US). Americans respect Germany more than they do Spain but still less than they should either; unless they have worked in Europe for years, their experience at Berlin Hbf and other modern stations is purely as tourists. The most celebrated New York public transportation appointment in recent memory, Andy Byford, is an expert (on operations) hired from abroad; as I implored the state last year, it should hire people like him to head major efforts like this and back them up when they suggest counterintuitive things.

Mainline rail is especially backward in New York – in contrast, the subway planners that I’ve had the fortune to interact with over the years are insightful and aware of good practices. Managers don’t need much political pressure to say absurd things about gradients and dwell times, in effect saying things are impossible that happen thousands of times a day on this side of the Pond. The political pressure turns people who like pure status quo into people who like pure status quo but with $20 billion in extra funding for a shinier train hall. But both the political appointees and the obstructive senior managers need to go, and managers below them need to understand that do-nothing behavior doesn’t get them rewarded and (as they accumulate seniority) promoted but replaced. And this needs to start with a federal line in the sand: BIL money goes to useful improvements to speed, reliability, capacity, convenience, and clarity – but not to a $20 billion Penn Station reconstruction and expansion that do nothing to address any of these concerns.