The Different National Traditions of Building High-Speed Rail

I’ve written five pieces about national and transnational traditions of building urban rail: US, Soviet bloc, UK, France, Germany. I’m about to continue this series with a post about Japan, but yesterday I made a video on Twitch jumping ahead to different national traditions of high-speed rail. The video recording cut two thirds of the way through due to error on my part, so in lieu of an upload, I’m writing it up as a blog post. The traditions to cover are those of Japan, France, Germany, and China; those are the world’s four busiest networks, and the other high-speed rail networks display influences from the first three of those.

The briefest description is that the Shinkansen is treated like a long-range subway, the TGV like an airplane at flight level zero, and the ICE like a regional rail (and not S-Bahn) network. China doesn’t quite fit any of these modes but has aspects of all three, some good, some not.

But this description must be considerably nuanced. For example, one would expect that airplane-like trains would have security theater and a requirement for early arrival. But the TGV has neither; until recently, platforms were completely open, and only recently has SNCF begun gating them, not for security but for ticket checks, with automatic gates and QR codes. Likewise, until recently passengers could get to the train station 2-3 minutes before the train’s departure and get on, and only now is SNCF requiring passengers to show up as long as 5 minutes early.

Tabular summary

| Tradition | Japan | France | Germany | China |

| Summary | Subway | Airplane | Regional rail | Mixed |

| Influenced | Korea, Taiwan | Spain, Italy, Belgium, Morocco | Northern Europe | — |

| Frequency | Very high | Low | Medium | High |

| Seat turnover | Medium | Low | High | Medium |

| Pricing | Fixed | Dynamic | Mixed | Fixed |

| Approximate fare/km | $0.23 | $0.14 | $0.15 | $0.10 |

| Egress | Very fast | Very slow | Medium | Fast |

| Integration with slow trains | Medium | Poor | Good | Poor |

| Average speed (major cities) | High | High, except Belgium | Mixed high, low | Very high |

| Timed connections | No | No | Yes | No |

| One-seat rides | Limited | Extensive | Common | Common |

| Security theater | No | Only in Spain | No | Yes |

| Platform access control | Yes | Increasingly yes | No | Yes |

| Major city stations | Central | Historic, Paris has 4 | Central | Outlying |

| Terminal turnarounds | Fast | Slow | Mixed | Slow |

| Minor city stations | Mixed | Outlying, “beet fields” | Usually legacy | Usually outlying |

| Freight | No | No | Yes | No |

| Grades | 1.5-2% | 3.5% | 1.25%, max 4% | 1.5-2% |

| Tunnels | Extensive | Rare | Extensive | Rare |

| Viaducts | Extensive | Rare | Rare | Extensive |

| Construction costs | High | Low or medium | Medium | High |

For more detailed data on costs and tunnel and viaduct percentage, consult our high-speed rail cost database.

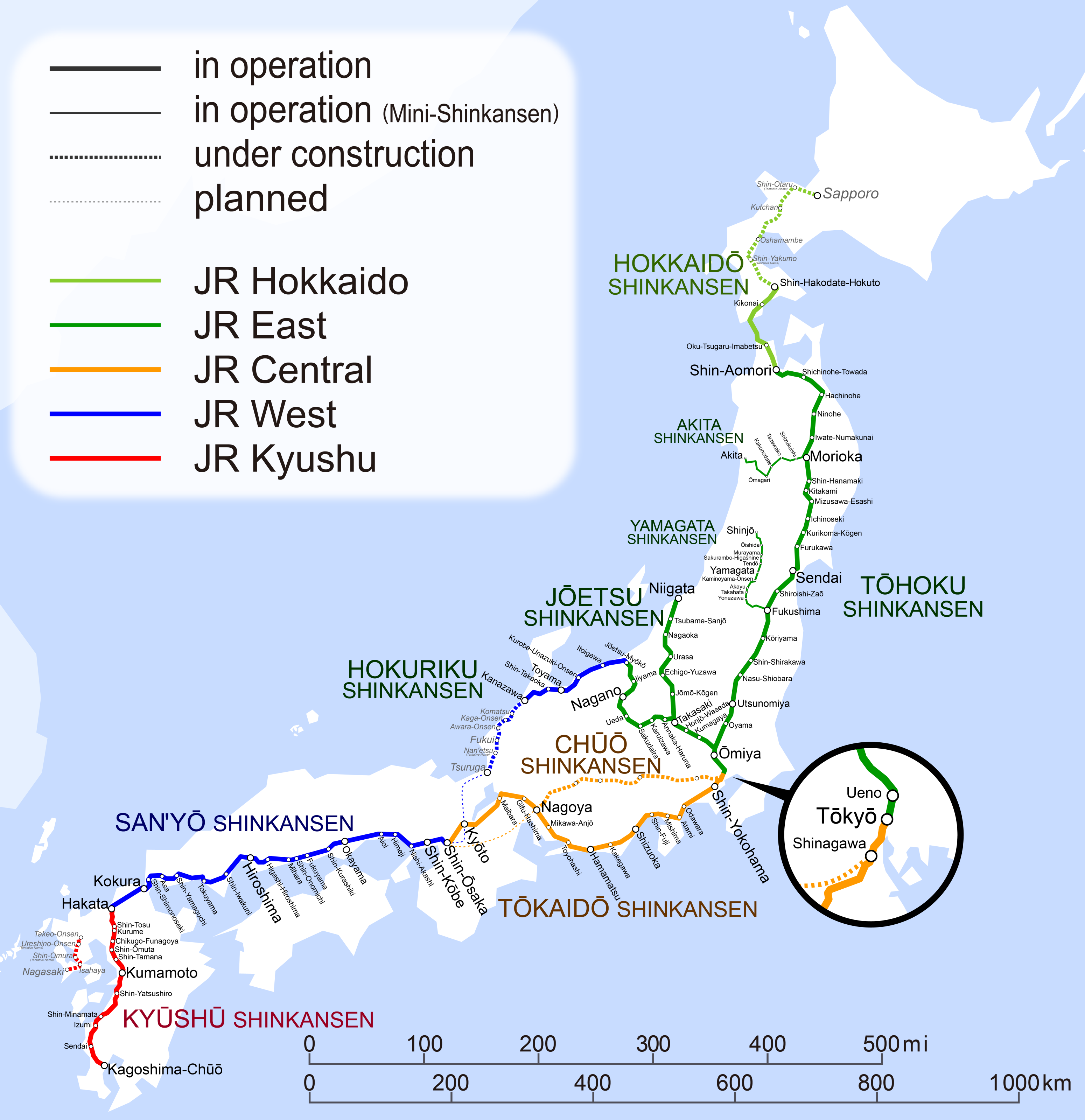

The Shinkansen as a subway

The Shinkansen network has very little branching. Currently there is none south of Tokyo; a short branch to Nagasaki is in planning but will not open anytime soon. To the north, there is more branching, and the Yamagata and Akita Mini-Shinkansen lines, the only legacy lines with Shinkansen through-service, split trains, with one part of the train continuing onward to Shin-Aomori and Hokkaido and another part splitting off to Yamagata or Akita.

Going south of Tokyo, the off-peak frequency to Shin-Osaka is four express Nozomi trains an hour, at :00, :09, :30, :51 off-peak; two semi-express Hikari, at :03, :33; and one local Kodama, at :57. The 21-minute gaps are ugly, but on a train that takes around 2.5 hours to get to Shin-Osaka, they’re not too onerous. Thus, there is a culture of going to the train station without pre-booking a ticket and just getting on the next Nozomi. The ticketing system reinforces this: there is no dynamic yield management, but instead fixed ticket prices between pairs of station depending on seat class. What yield management there is is static: the Nozomi has a small surcharge, to justify excluding it from the JR Rail Pass and so shunt tourists to the Hikari.

This is not literally the headway-management system seen on some unbranched subway systems, like the Moscow Metro and Paris Métro; Moscow keeps time by distance from the preceding train, and not by a fixed schedule. But this is fine: some subway systems are timetabled, like the U-Bahn in Berlin and the Tokyo subway. Tokyo even manages to mix local and express trains on some two-track subway lines with timed overtakes. To the scheduler, the fixed timetable is of paramount importance. But to the passenger, it isn’t – people don’t time themselves to a specific train.

Another subway-like characteristic includes interior layout, designed around fast egress. Shinkansen cars have two door pairs each and platforms are 1,250 mm high with level boarding, enabling 1 minute dwell times even at very busy stations like Shin-Osaka. Trains make multiple stops in the Tokyo and Osaka regions, and even Nozomi and equivalent fastest-train classes on other lines stop there, to distribute loads. There is no cafe car, and luggage is overhead, to maximize train seating space: a 25 meter car has 18-20 seating rows with 1-meter pitch, which is greater efficiency than is typical in Europe.

Station location decisions, finally, are designed as far as practical to be in city centers. Stations with Shin- before their names are new stations, like Shin-Osaka and Shin-Yokohama, but they tend to be sited close to city centers, at intersections with subway and commuter rail lines.

The main drawback of Japan is that the construction costs are very high. This comes from a political decision to build elevated lines rather than at-grade liens with earthworks, as is common in Europe. This preponderance of els has been exported to South Korea, Taiwan, and China, all of which have high costs relative to the tunneling proportion; the KTX, essentially a Shinkansen adapted to an environment in which the legacy trains are standard-gauge too, is notable for having low tunneling costs, as is common in Korea, but high costs on lines with moderate amounts of tunneling thanks to the high share of construction on bridges.

East Asia has high population density, which lets it get away with high costs since the ridership is high enough to compensate – THSR is at this point returning around 4% on very high costs. But in any other environment, this leads to severe problems. China, with lower incomes and fares than in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, already has trouble paying interest on lines other than the Beijing-Shanghai system. India, building a turnkey Shinkansen as recommended by Japanese consultants, who were burned by Taiwan’s mix of European and Japanese technology on an operationally-Japanese system, is spending enormous sums of money: the Mumbai-Ahmedabad corridor is around PPP$50.6 billion, for 508 km, $100 million/km on a line that’s only 5% in tunnel and even those tunnels could have been avoided by running on broad gauge and using existing a widened legacy right-of-way in Mumbai.

The TGV as flight-level zero air travel

As detailed in New Departures by Anthony Perl, the history of the TGV differs from that of the Shinkansen in a key aspect: the TGV was built after the postwar decline of rail travel (as was the ICE), whereas the Shinkansen was built before it (as was to some extent CRH). The Shinkansen was built in 1959-64: there was no decline in rail evident yet, with only 12 cars/1,000 people in Tokyo in 1960, and the system was designed to deal with growing ridership. In contrast, the TGV was planned after the 1973 oil crisis, in a then-wealthier and more motorized country than Japan, aiming to woo passengers back to the train from the car and the plane.

Previously, SNCF had been engaging in experiments with high speed and high-voltage electrification, inventing 25 kV 50 Hz electrification in the process, which would be adopted by the Shinkansen and become the global standard for new electrification. It also experimented with running quickly on ballasted track – without modifications, the trains of that era kicked ballast up at high speed, there was so much air resistance. But investment had gone to legacy intercity rail, driving up the average speed of the electrified Mistral to 130 km/h and the Aquitaine to 145 km/h. Nonetheless, competition with air was fierce and air shuttles in that era before security theater attracted many people in competition with four-hour trains from Paris to Lyon and Bordeaux.

The TGV’s real origin is then 1973. The crisis shocked the entire non-oil-exporting world, leading to permanently reduced growth not just in rich countries (by then including Japan) but also non-oil-exporting developing countries, setting up the sequence of slow growth under import substitution and then the transition to neoliberalism. France reacted to the crisis with the slogan “in France, we have ideas,” setting up the nuclearization of French electricity in the 1980s, reduced taxes on diesel to encourage what was then viewed as surplus fuel rather than as a deadly pollutant, and the construction of the electric TGV.

Despite the ongoing growth of the Shinkansen then, there was extensive skepticism of the TGV in the 1970s and early 80s. The state refused to finance it, requiring SNCF to borrow on international markets. The LGV Sud-Est employed cost-cutting techniques including 3.5% grades and high superelevation to avoid tunnels, at-grade construction with cut and fill balancing out to avoid surplus dirt, and land swaps for farms that would be split by the line to avoid needing to build passageways.

Construction costs were only 5.5M€/km in 2021 euros. Unfortunately, costs have risen since and stand at 20M€/km, or even higher on Bordeaux-Toulouse. But the LGV network remains among the least tunneled in the world thanks to the use of high grades; in our database the only less tunneled network, that of Morocco, is a turnkey TGV, built at unusually low cost.

As in Japan, the line was built between the two largest cities: Paris and Lyon. Also as in Japan, Lyon could not be served at the historic center of Perrache, but instead at a near-center location, Part-Dieu, which then became the new central business district, as the LGV Sud-Est was built concurrently with the Lyon Metro and nearby skyscrapers, as is typical for a European city wishing to avoid skyscrapers in historic centers. But everything else was different. There were no real intermediate stops the way that the express Shinkansen have always stopped at Nagoya and Kyoto: the LGV Sud-Est skipped Dijon, which instead was served on a branch, and the two intermediate stops on the line, Le Creusot and Mâcon-Loché, are on the outskirts of minor towns and only see a few trains per day each.

Moreover, relying on France’s use of standard-gauge, there was, from the start, extensive through-service beyond Lyon, toward Marseille, Geneva, Saint-Etienne, and Grenoble. Frequency was for the most part low, measured in trains per day. There was little investment in regional rail outside the capital, unlike in Germany, and therefore there was never any attempt to time the connections from Saint-Etienne and Grenoble to the TGV at Part-Dieu.

At the other end, Paris did not build a central station, unlike German or Japanese cities. The time for such a station was, frustratingly, just a few years before work began on the TGV in earnest: RATP was building the RER starting in the 1960s and early 70s, including a central station at Les Halles, which opened 1977. But this was designed purely for urban and suburban use, and the TGV stayed on the surface. The last opportunity for a Paris central station was gone when SNCF extended the RER D from Gare de Lyon to Les Halles. Thus Paris has four distinct TGV stations – Lyon, Montparnasse, Nord, and Est – with poor connections between them.

This turned the TGV into a point-to-point system. Were there a central station, trains could have gone Lille-Paris-Lyon-Marseille. But there wasn’t, and so for Lille-Lyon service, SNCF built the Interconnexion Est, bypassing Paris and also serving Disneyland and Charles-de-Gaulle Airport. When the LGV Atlantique opened, Tours kept its historic terminal, and thus trains went either Paris-Tours or Paris-Bordeaux bypassing Tours. When the LGV Sud-Est was extended south with the LGVs Rhône-Alpes and Méditerranée, trains did not go via Part-Dieu, even though it had always been configured as a through-station for points south, but rather via a bypass serving Lyon’s airport; trains today go Paris-Lyon, Paris-Marseille, or at lower frequency Lyon-Marseille, but not Paris-Lyon-Marseille.

Of note, Japan’s subway-like characteristic is partly the outcome of its linear geography along the Taiheiyo Belt, making it an ideal comparison also for the Northeast Corridor in the United States. But Lille, Paris, Lyon, and Marseille are collinear, and yet the service plans do not make use of that geography. There is no planning around seat turnover: if a train makes an intermediate stop, it’s one with very low ridership, like Mâcon, with no attempt to have seats occupied by Paris-Lyon passengers and then by Lyon-Marseille ones.

Over time, this led to a creeping airline-ization of the TGV. Airline-style dynamic yield management was introduced, I believe in the 1990s. This was after SNCF had spent the 1980s marketing the TGV as 260 km/h for the same fare as 160 km/h; the overall fares on legacy intercity trains and TGVs are similar per p-km, but TGVs have opaque pricing, and are designed to maximize fares out of Paris-Lyon in particular, where air competition vanished. The executives at SNCF are increasingly drawn from the airline world, and, perhaps out of social memory of the navettes competing with 4-hour trains in the 1970s, they think that trains cannot compete with air travel if they take longer than 3-3.5 hours, even though they do successfully on such city pairs as Paris-Toulon.

Having skipped Germany’s InterCity revolution and its refinements in Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands, the TGV network has stagnated in the last decade. Ridership is up since the pre-Great Recession peak but barely, only by around 10%. The frequency is too weak for inter-provincial links, where people mostly drive, and in the 1990s and 2000s the TGV network grew to dominate the Paris-province market; there isn’t much of a remaining market for the current operating paradigm to grow into.

While some regional links are adopting takt timetables, for example some of the Provence TERs, SNCF management has done no such thing. Instead, it has spent the last 15 years pursuing airline strategies, including imitation of low-cost airlines, first iDTGV and then OuiGo. A generalist elites of business analysts believes in market segmentation and price discrimination, which do not work on a mode of travel where a frequent, flexible timetable is so paramount.

Among the countries influenced by France, Spain is notable for realizing that it has a problem with operations. In an interview with Roger Senserrich, ADIF head Isabel Pardo de Vera spoke positively of Spain’s efficient engineering and construction, but centered ADIF and RENFE’s problems, including the poor operations. Like Italy and Belgium, and more recently Morocco, Spain learned the concept of high-speed rail from France; also like Italy and Belgium, it mixed in a few German elements, which in the 1980s meant Germany’s more advanced LZB signaling, but at the time, there was no Switzerland-wide takt yet, and the inferiority of French operations and scheduling was not yet evident. But Spain self-flagellates – this is how it learns – whereas France is just a hair too rich to recognize its weaknesses and far too proud for its elite to Germanize where needed.

The ICE as long-distance regional rail

Germany came into the 1960s with some of the most advanced legacy rail in the world, with technology that would be adopted as a Shinkansen standard. This goes back to the 1920s, when Deutsche Reichsbahn was formed from the merger of the state-level railways in the wake of the post-WW1 German Revolution. The new railway regulation, dating to 1925, promoted new kinds of engineering now completely standard, such as the tangential switch. DRB would also experiment with 200 km/h diesel express trains in the 1930s. Even in the 1960s and early 70s, when the most advanced rail tech was clearly in Japan, Deutsche Bundesbahn kept up with rail tech, much like SNCF, inventing LZB signals.

But unlike Japan and France, Germany never built a complete high-speed rail network. The InterCity network, dating to 1971, was designed around fast legacy trains, at slightly lower speeds than available on the express French legacy trains. The key was that city pairs would be served every two hours, with timed connections at intermediate points boosting many to hourly. This was from the start based on a regular takt and turnover, with more expansive service to smaller cities.

High-speed lines in Germany were delayed, and often built on weird alignments. The most important reason is that in the formative period, from 1971 to 1990, there was no such country as Germany. The country was called West Germany, and, much like Japan, had a fairly linear population distribution from the Ruhr upriver to Cologne, Frankfurt, Mannheim, and finally either Karlsruhe or Stuttgart and Munich; but the largest city proper, Hamburg, lay outside this corridor.

The north-south orientation of West Germany contrasted with the rail network it inherited. Until the post-WW1 German Revolution, the rail networks were run by the states, not by the German Empire, and thus interstate connections were underbuilt. Prussia had an east-west orientation, and therefore north-south lines were relatively underbuilt (see for example the 1896 map), and to top it off most north-south routes crossed the Iron Curtain.

To solve many problems at once, but not to solve any of them well, Germany’s first high-speed line connected Hanover, Göttingen, Kassel, Fulda, and Würzburg. Getting to more substantial cities like Hamburg and Frankfurt requires onward through-service at lower speed. The LGV Sud-Est had a minimum curve radius of 3.2 km, and usually 4 km, and can squeeze 300 km/h out of it now, without any tunnels; the Hanover-Würzburg line has a minimum radius of 5.1 km and a maximum grade of 1.25% and is limited to 280 km/h (service runs at 250 km/h), as it was built as a mixed freight-passenger line.

Subsequent lines have, like Hanover-Würzburg, not been complete connections between major cities. Here the difference with France, Italy, South Korea, and China is evident. All are standard-gauge countries, like Germany, and all employ through-service to various degrees. But France opened a complete Paris-Lyon high-speed line in 1981-3, and only the last 30 km into Paris were on legacy trains (since reduced to 8 km with the Interconnexion Est), and likewise Italian, Chinese, and Korean high-speed lines connect major cities all the way. In contrast, this never happens in Germany at longer distance than Cologne-Frankfurt, a 180 km connection. There are always low- or medium-speed segments in between. The maximum average speed between major cities in Germany is either Cologne-Frankfurt or Berlin-Hamburg, a 230 km/h line with tilting trains, both averaging around 180 km/h; the Tokaido Shinkansen, with legacy 2.5 km curves, squeezes 210 km/h out of the Nozomi, and LGVs routinely average 230-250 km/h between Paris and major secondary cities.

Nor are the lower speeds in Germany saving money. The mixed passenger/freight lines have heavier tunneling than they would need if they had 3.5-4% grades. Hanover-Würzburg cost 36M€/km in 2021 euros thanks to its 37% tunneled alignment. German construction costs are not high relative to the tunneling percentage, unlike Chinese or Taiwanese costs, let alone British ones, but the tunneling percentage is in many cases unnecessarily high. This is thankfully not exported to every Northern European country that learned from the InterCity, but the Netherlands, as NIMBY-ridden as Germany, built an unnecessary tunnel on the HSL Zuid and had very high costs even taking that into account; Italy, with an otherwise-French system, likewise overbuilds, as pointed out by Beria-Albalate-Grimaldi-Bel, with viaducts designed to carry heavy freight trains even where there is no such demand.

So the bad in Germany is that the lines have very shallow grades, forcing heavy tunneling, and the costs are so high that the system is not complete. Is there good? Yes!

The InterCity system’s focus on high frequency enables decent service between major cities. Berlin-Munich trains, compromised by the Erfurt detour and subsequent descoping of much of the line, do the trip in 4.5 hours where they should be taking 3 and even 2.5 hours. But it’s not the same as the 4 hours of the pre-TGV Mistral to Lyon or Aquitaine to Bordeaux, the latter of which averaged the same speed as most Berlin-Munich trains today. The Aquitaine ran as a single daily Bordeaux-Paris-Bordeaux round-trip, and another train, branded the Etendard, ran the same route daily but Paris-Bordeaux-Paris. In contrast, DB today connects Berlin-Munich roughly every hour. It’s far more flexible, and the connections to other intercity trains are better.

And just as the TGV’s inexpensive construction has been perfected in Spain while France has slouched on cost control, so has the interconnected system of Germany been perfected on the margins of its sphere of influence, especially in Switzerland. Swiss connections are never fast: the country is too small for 300 km/h trains to make large differences in door-to-door trip times. The average speed on the workhorse Swiss lines connecting the Zurich-Bern-Basel triangle is around 110-120 km/h. But they run on a half-hourly takt, and other lines run on an hourly takt, and connections at the major cities are timed. European urbanism has a long tail of small cities, unlike American or Asian urbanism, and the Swiss takt connections those small cities to one another through regular timed transfers, with investments to prioritize punctuality.

This leads to a false belief among German rail advocates in a tradeoff between French or Spanish speed and Swiss or Dutch or Austrian connectivity. The latter set of countries have higher rail ridership per capita, and even Germany has recently overtaken France’s intercity rail ridership (though not yet per capita), and thus activists in Germany think investing in high speed is a waste. But what is actually happening is that the countries of Europe that look up to France have built high-speed rail, and the countries that look down on France have not; the Netherlands has HSL Zuid but it’s peripheral to the national network and its system is otherwise rather Swiss. Germany absolutely can and should complete its network. It just needs to understand that in certain aspects, countries it is used to stereotyping as spendthrift have done a more prudent job than it has.

Already, the younger rail advocates I meet, like Felix Thoma, seem interesting in applying the Deutschlandtakt concept to a high-speed rail network, rather than to a medium-speed one as the previous generations called for. But Germany is a NIMBY country. NIMBYs blocked French levels of energy nuclearization in the 1970s and 80s, creating the last generation’s Green Party (current leader, Annalena Baerbock, is 40 and came of age after those fights); NIMBYs sue projects they dislike on frivolous grounds until the politicians lose interest, much as in the US with its government-by-lawsuit, and thus high-speed rail on the Hamburg-Hanover line has been stuck in limbo for a generation.

Besides the political deference to NIMBYs, who as in the US are not as powerful as either they or the state thinks, the main problem then is unwillingness to merge French and German planning insights where they work. I might also add Japanese insights – the Shinkansen is far more efficient with platforms than any European railroad – but they’re less important here or in France than in the UK, which is a ridiculously high-cost version of French planning.

China as a mixture of all modes, some good, some awful

When I started planning this video and now post, I was puzzling over where to slot China. Other systems seemed fairly easy to slot as Japanese, German, or French, with the occasional special feature (insanely high UK costs, HSL Zuid in an otherwise Swiss intercity takt system, Korean standard-gauge adaptations). But China is its own thing. It makes sense: on the eve of corona, China had 2.3 billion annual high-speed rail riders, comfortably more than than the rest of the world put together; Japan, the second busiest network, had 436 million. In Europe, only France has more high-speed rail ridership per capita, by the smallest of margins.

Historically, the system should be viewed as having borrowed liberally from other systems in richer countries that built out their networks earlier. Among the three prior traditions, the one most similar to what CRH has converged on is the Shinkansen, and yet there is significant enough divergence I would not class CRH as a direct Shinkansen influence the way I do the KTX and THSR. This also mirrors the situation for rapid transit: China displays clear Soviet influences but has diverged sufficiently that it must be viewed as a separate tradition now.

The most important feature is that CRH evolved on the cusp of the decline of rail in favor of cars and planes, a decline that has been more complete in Western countries. In the 1980s and early 90s, China was already growing very quickly; this was from a very low base, so it was not noticed in richer countries, but it was enough that there were already motorization and domestic air travel competing with China Railway. This led to a multi-phase speed-up campaign, announced in 1993 and implemented from 1997 to 2007.

At this point, construction was on legacy alignments to legacy stations. In the North China Plain, the railroads were straight thanks to the flat topography, and so what was needed was investment in the quality of the physical plant – the sort of investments figured out in midcentury France and Germany, adapted by the Shinkansen. This was not trivial, not in a then-low-income country like China, but it was not enormously expensive either. At the same time, there was growing electrification in China, using 25 kV 50 Hz, leading to higher and higher train classes, all charging premium fares over the third-world tickets for traditional trains. At the apex was the D class, covering 200 km/h EMUs; the one time I rode a train in China, a day trip from Shanghai to Jiaxing and back in 2009, the way back was on a D class train, which had the comfort level and speed of the Northeast Corridor, topping at 170 km/h and averaging maybe 110. This investment has continued, and as of 2019, 72% of the network is electrified.

But China was already looking for more. In 2008, the Beijing-Tianjin high-speed line opened, as the world’s first 350 km/h line. In the financial crisis’s aftermath, China rapidly built out the network as fiscal stimulus, and by 2011, ridership overtook the Shinkansen’s as the world’s largest. Without legacy considerations, the system is built for 380 km/h, even though trains run at 350 km/h, and express trains average 280-290 km/h.

Like the United States and unlike Japan or most of Western Europe, China has an extensive freight rail network. Its approach is the opposite of Germany’s: high-speed lines are dedicated to passengers, and some are officially called passenger-dedicated lines, or PDLs, to make this clear. Freight trains go on the legacy network. Regional rail in China is very weak; the few lines that exist are new-builds, rather like long-range subways, and frequency is often lacking, the Beijing lines branded as S-Bahn barely running off-peak. With nearly all intercity rail having moved over to CRH, the legacy network is relatively free for freight use, even coal trains, which are slow and care little for reliability improvements for higher-end intermodal cargo.

However, the passenger-only characteristic of CRH’s system does not mean it’s employed French cost-cutting techniques. Rather, lines run almost exclusively on viaducts and have shallow grades, raising construction costs as in the rest of East Asia. Stations are newly-built at high expense: Beijing South cost 7 billion yuan, which in today’s PPP dollars is around $3 billion. There are many tracks and no economization with fast turnarounds as in Japan, and station layouts are comparable to airports, with some security theater.

Beijing South is at least just outside the Second Ring Road. Other stations are farther out. This is not just the beet field stations that characterize TGV service to small cities like Amiens or Metz, but also outlying stations in major centers. Shanghai Station only sees high-speed trains on the local line to Nanjing, providing a dedicated track pair equivalent to Kodama service while Nozomi-equivalent trains continue on to Beijing on their own tracks. The trains to Beijing get a separate Shanghai station, Hongqiao, colocated with the city’s domestic airport. The connecting subways tend to be better than at true beet field stations in France, which miss regional rail connections, but those stations are still well outside city center.

China is moreover exporting the bad more than the good. Chinese-funded projects in Africa are not fast – the average speeds are perhaps midway through China’s speed-up campaign, predating CRH. But they do have oversize, airport-like stations located well outside city centers. This happens even when right-of-way to enter city center exists, as in Nairobi.

On mixing and matching

Understanding these four distinct traditions is important for high-speed rail planning, in those four countries as well as elsewhere, such as in the UK and US. It’s important to understand the tradeoffs that these traditions made, and drawbacks that are not so much tradeoffs as things that didn’t seem important at the time.

Most notably, Britain has oversize stations, spending billions on new terminals such as in Birmingham. This comes from the low efficiency of most European turnaround operations, because most European cities have huge rail terminals from the steam era with a surplus of tracks. When trains need to turn fast, they do: German trains running through Frankfurt, which is a terminal, turn in 3-4 minutes to continue to their onward destination. In Tokyo, where space is at a premium, JR East learned to turn trains in 12 minutes even while giving them a cleaning, and with such tight operations, Britain should be able to fit traffic growth within existing station footprints.

It is also desirable to learn from students who have surpassed their old teachers. Korea has lower construction costs than Japan, Spain has lower construction costs than France and greater understanding of the need to integrate the timetable and infrastructure, Switzerland has perfected the German system to the point that German rail advocacy calls for reimportation of its planning maxims.

In the same way that Taiwan built infrastructure to European specs but is running Japanese trains on it, to its profit and to Japan’s chagrin, it may be advisable to build infrastructure in the French (or, better yet, Spanish) way but then run trains on it the German (or better yet, Swiss) way. But it’s more nuanced than this conclusion, due to important contributions from China and Japan, and due to the focus on having a central station, which France chose not to build in Paris to its detriment.

But in general, I think it behooves countries to learn to implement the following from those four traditions:

- Japan: the best rolling stock, high-efficiency turnaround operations, reliable schedules; avoid excessive viaducts and Japan’s increasing demand for turnkey systems.

- France: passenger-dedicated infrastructure standards (supplemented by Cologne-Frankfurt), land swap deals for at-grade construction, cost control (in the Spanish version – France is deteriorating); avoid TGV rolling stock and airline-style pricing.

- Germany: takt (especially in the Swiss and Dutch versions), open station platforms, integration between timetable and infrastructure, seat turnover, decent rolling stock; avoid empowering NIMBYs and building mixed lines with freight.

- China: separation of passenger and freight operations, very high average speeds; avoid airline-style outlying stations and excessive viaducts.

I’m not clear where you think the Shinkansen should have been built at grade given the terrain and the city locations.

And I’m pretty sure north of Tokyo outside of built up areas it is at grade.

The more recent lines are sub-10% on earthworks, the rest being either on viaduct or in tunnel.

I’m not sure where the at grade is on the Tokaido Shinkansen because of the terrain/urban areas – there certainly wasn’t a lot.

I guess maybe the Chou Shinkansen could have more at grade and perhaps the lines beyond Hiroshima or Sendai or the branch lines in the north that I’ve not been on (which are to be fair newer) – but Japan seemed pretty mountainous and built up to me.

The Tokaido Shinkansen is more at-grade than the rest – Japanese Wikipedia says 53% on earthworks.

Still, you can’t entirely discount geography. France has no mountain ranges to tunnel thru except for the French Alps which are at the border and only relevant for the link to Torino (which will indeed have one of the longest railway tunnels on earth). The Massif Central has formidable mountains, but it is not “in the way” of any major hsr axis.

In Germany, meanwhile, you can’t go north to south without crossing several mid sized mountain ranges…

Of course the decision to have lines that allow freight led to more tunneling but if you applied the 100% identical policies to French and German hsr, the German network would still have more tunnels due to geography

It’s 53% on earthworks, but it’s not really “at grade”. The earthworks involved are generally taller than a lot of earthworks in Europe, enough to fit a medium sized truck (~4m) underneath without lowering the road at all, and a lot of roads go under it (one every 100-500m in farmland, which is the main place embankments get used, since otherwise it’s viaduct, trench, or tunnel).

And even in Britain where I think you should be able to build high speed rail largely at grade the chiltern hills are pretty steep which may justify some short sub 2km tunnels if you want to avoid existing settlements. And while we could knock down more post 1880 housing (and certainly more post 1945 housing) I think demolishing old village centres would be hugely unpopular. Plus we have more public footpaths (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rights_of_way_in_England_and_Wales) and routes for horses which will need disabled accessible crossings of the railway or diversions.

This doesn’t mean we can’t do things for something substantially closer to French costs – or possibly cheaper as I’m not convinced the french built their network for the lowest possible cost – but every country is different.

Hokuriku Shinkansen Tsuruga to Osaka section, giving up the Kosei Line alignment for Obama to Kyoto obviously elevated the cost unnecessary

Chuo Shinkansen also obviously used more tunneling than otherwise necessary but I think it is understandably so given its emphasis on speed. But one thing I wonder is how will its terminal station at Shinagawa connect with JR East’s Shinkansen system.

Hokkaido Shinkansen Sapporo Extension having high tunneling ratio is understandable I think given the geography?

And on the other hand for Korea I have also learnt about they’re trying to copy the French way of system design, but terrain make them needing to build more tunnels and bridges than French

High tunneling for Chuo Shinkansen is not only for speed and topography but also for ease of easement acquisition thanks to “大深度地下” (deep underground). They came up with a national law during the real estate bubble economy in 1980s (finally went into effect in 2001) which allows one to dig under someone else’s property without easement in the 3 largest metropolitan areas if the underground structure is built 40 meter or deeper below the surface (as well as other conditions) as long as the construction is approved by the government as deep underground infrastructure construction. Chuo Shinkansen is using this scheme to avoid construction easements while building straight maglev line in the middle of Tokyo and Nagoya. On Shinagawa side, the alignment stays straight deep underground tunnel all the way from Shinagawa to Kanagawa-Yamanashi prefectural line with minimum amount of horizontal curves.

Hokkaido Shinkansen Sapporo Extension is due to topography and alignment choice. That part of Hokkaido is very mountainous and geologically very active. The Shinkansen alignment also needs to pass through several active volcanoes in order to get from Hakodate and Sapporo.

Hokuriku Shinkansen Tsuruga to Osaka section has the same topographic challenge like the Sapporo extension. Unless the alignment goes to Maibara or along Kosei Line, it needs to go through multiple mountain ranges. Also, building a new high-speed rail line in the built-up suburbs and cities between Kyoto and Osaka does not help (they might use deep underground scheme for this extension).

Yes I am talking about their choice of routing through Maibara instead of following Kosei line

Fascinating topic.

I agree Korea’s KTX is quite similar to Shinkansen as described above. There are a couple of differences that I thought I might point out:

– KTX has no platform access control. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve run to the platform a minute before the doors closed.

– As you mentioned, Korea has a standard gauge legacy rail network. The consequences of this is that KTX often runs onto upgraded legacy track. While the Gyeongbu and Honam high speed lines are new-build 300 km/hr dedicated passenger lines, the Jeolla, Gyeonggang and partially open Jungang lines are a mixture of upgraded legacy and new-build track with speed limits ranging from 150-250 km/hr. In fact, much of Korea’s remaining legacy network is being incrementally replaced with new-build track over the coming decade. Another consequence of the standard gauge legacy network is that Korail (the national rail operator) offers services that run partially on legacy track. For example, heading south from Seoul station, a few trains a day will stay on the legacy Gyeongbu line in order to serve Suwon (a satellite city of Seoul to the south with ~1 million inhabitants) and re-join the high speed Gyeongbu line at Daejeon.

– KTX has a highly diverse stopping pattern. For example, KTX trains on the Gyeongbu line all stop at the major stations of Seoul, Daejeon, Daegu and Busan (aside from the last few services of the day). Among the 6 minor intermediate stations, there are trains that stop at none of them, all of them, and practically every combination of the 6. Taiwan’s HSR is similar in this regard. I’m not sure whether Japan does this also, or whether all Hikari services for example have the same stopping patterns. If I recall correctly, Alon has advocated for simplifying stopping patterns, but I’m not sure what the rationale is. As far as I can tell, aside from it being a bit confusing, there doesn’t seem to be a massive drawback.

Japan sometimes has weird stopping patterns. It depends on the line; on Tokaido, the Hikari have a bunch of different patterns, half making all Nagoya-Shin-Osaka stops and then of those half also serve Odawara and half also serve Toyohashi, and half skipping local Nagoya-Shin-Osaka stops but serving Shizuoka and Hamamatsu and those sometimes also stop at Odawara or Mishima. But the majority of trains are Nozomi with fixed patterns on Tokaido.

Edit: the difference with France is that France doesn’t have major all-stops stations the way Japan has Nagoya, Hiroshima, and Sendai, or the way Korea has Daejeon and Dongdaegu. Paris-Marseille trains don’t stop at Part-Dieu and rarely stop at Saint-Exupéry.

I think one reason behind such stopping pattern in Japan is that, for smaller cities, passengers travelling there are much more likely heading from/to a major cities, than is to/from another small/mid-sized cities. Thus, it is not effective and not necessary to have trains serving all the smaller cities along the line. As a result, different Hikari trains serve different smaller cities in order to give those cities a still relatively fast access speed to major cities instead of being slowed down to made multiple stops in between

I agree. Would this not generalize to all countries? Are these small travel time savings worth the additional operational complexities of diverse stopping patterns?

The ICE very occasionally does a somewhat similar thing by serving certain cities only in the morning and evening (“Tagesrand” they call it) for example Coburg in northern Franconia is bypassed by most Berlin-Munich ICEs but some do stop there…

I think China HSR network have some similar stop allocations, but for other countries the frequencies probably isn’t big enough to support multiple stop pattern

Also, there are difference in demand potential between those non-all-stop cities. For example, Shizuoka and Hamamatsu are larger cities with more large companies basing there (Yamaha and Suzuki headquartered in Hamamatsu) and government offices (Shizuoka is prefectural capital of Shizuoka Prefecture, and some branch offices of the national governments are located there) than other stops like Kakegawa or Mishima. These cities needs to be served more frequently with slightly faster trains than other stops due to demand and potential.

Those Hikari trains stopping at Shizuoka and Hamamatsu are very well utilized and one of the most difficult trains to get the reserved seats even though these trains are overtaken by 2 to 4 Nozomi trains between Tokyo and Nagoya (more difficult to get a reserved seat on the other Hikari trains stopping either Odawara or Toyohashi even though the train don’t get overtaken by any other train between Tokyo and Nagoya), and a lot of seats on the train get turned over at Shizuoka and Hamamatsu.

See this is why they need to improve conventional services in Shizuoka! (Lets not go there again)

Still given that the Tokaido line is at capacity and has a speed constraining alignment, I can’t see how semi-expresses (which is what Hikari would be called in conventional Japanese rail lingo) could be made more regular without screwing Nozomi passengers. JR Central is proposing more such services once the Maglev is complete.

Alon and others have made the argument that the Shinkansen operates like a subway which is definitely a good argument to make with operators and commentators who don’t quite get how the Shinkansen kills on frequency and simplicity. Pedantically its more like conventional Japanese urban rail, with local (serving all stations), semi-expresses, section-expresses and expresses (I hate the translation of Kyuko as Rapid). Nasuno and Kodama are local, Nozomi and Hayabusa are expresses, Yamabiko a section express, and Hikari is a semi-express.

With how JR Central plan to make the Chuo Shinkansen effectively online ticketing only, it might lost some of such feature

@borners

I try not to get into the conventional rail argument to respond…

Improved conventional rail in Shizuoka would not improve this because majority of these passengers getting on or off Hikari trains at Hamamatsu or Shizuoka seems to be traveling outside of the conventional rail range based on my observation onboard. Majority of them are business travelers on suits with a briefcase coming from Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka while there aren’t a lot of passengers using Hikari between Hamamatsu and Shizuoka. Even if there were rapid or limited express trains on the conventional rail, it cannot match the speed offered by the Shinkansen service. While these Hikari trains are scheduled to run between Nagoya and Shizuoka and between Tokyo and Shizuoka in about an hour, one hour on Tokaido Main Line can only get from Nagoya to Toyohashi (on New Rapid) or from Tokyo to Odawara (on Limited Express Odoriko), which are less than a half of the distance to Shizuoka (I actually took Limited Express Tokai from Shizuoka to Tokyo before being discontinued, and hated it because it was just too slow and waste of time compared to even Kodama trains on the Shinkansen).

The other argument one could make to justify current Tokaido Shikansen service is difference in population, employment, and number of corporations between Shizuoka-Hamamatsu metro area and 3 largest metropolitan areas in Japan (Kanto, Keihanshin, and Chukyo). Even though Shizuoka-Hamamatsu area is home of some key large corporations, it has just 1/3 of population, 40 percent of population density and number of corporations basing, and a little more than 1/4 of employment compared to Chukyo region, the smallest of the 3 largest:

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%85%AB%E5%A4%A7%E9%83%BD%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%8F_(%E6%97%A5%E6%9C%AC)

In other words, it need a semi-express equivalent service serving Shizuoka and Hamamatsu while making all Nozomi trains to be an true express service connecting 3 largest metropolitan areas in Japan very frequently and as fast as possible because of the size of and density within each of these 4 metropolitan areas and trip demand potential.

I think Alon use subways over Japanese conventional rail in this case because not many people know how Japanese conventional rail service structure looks like based on comments made by some regulars of this blog and interactions with professionals working in the railroad service planning in North America. Another way of characterizing the Shinkansen service is to a high-speed rail service operated just like Japanese conventional rail service in large metropolitan areas or on heavily-utilized passenger rail corridor in Japan but on the dedicated standard-gauge high-speed rail tracks using the high-speed rail trainsets, but again, this wouldn’t work well.

The Tokaido Shinkansen is a “subway” in that it has relatively high stop density for a HSR line, i.e. a station every 30 km. (For comparison, the Beijing – Shanghai HSR line only has a stop every 50 km.) A subway-like operation would have all Nozomi stop at an intermediate station like Shizuoka so that riders can transfer to / from local stations, but no station has the island platforms to support that. Furthermore, the current reality is that most riders want the fastest service between Tokyo and Nagoya / Kyoto / Osaka, so JR Central runs the majority of its trains as flight-level zero Nozomi.

Subsequently, the Chuo Shinkansen is being built as a flight-level zero HSR line taking the shortest path between Tokyo and Nagoya / Osaka, with 1 tph at intermediate stops to pacify local prefectures. This would allow for all Tokaido Shinkansen trains to stop at Shizuoka and Hamamatsu, most trains to stop at Toyohashi, and more service to all the other stations, while reducing the number of overtakes that slow the Kodama trains too significantly.

However, the Chuo Shinkansen is going to suffer from capacity issues because of the turnouts required to support the 1 local tph, so JR Central is likely going to price the Chuo Shinkansen to maximize profits. The Tokaido Shinkansen will still be at capacity, except it will resemble the Sanyo Shinkansen more, with most trains stopping at the currently underserved Shizuoka, Hamamatsu and Toyohashi stops.

This is a common practice with US commuter rail too. There is a line with let’s say 30 stops, the train only makes about 5 consecutive stops, then runs express to downtown. The idea is that suburb-to-suburb travel is minimal, and particularly with diesel trains the stop penalty for a fully local service is intolerable.

Is there a reason why this would be a good idea for US commuter rail and a bad idea for Shinkansen, or vice versa?

It’s a terrible idea in US commuter rail, because frequency really matters, and people don’t just travel to (say) Manhattan. And it’s not even about diesel trains – the railroads that do this the most aggressively, the LIRR and Metro-North, run EMUs.

Note that Japan barely does this. The Kodama makes all stops, the Nozomi makes only the major stops, and half the Hikari make major and semi-major stops. This is also how rapid trains work on commuter rail in Japan: the special rapids on the Chuo Rapid Line serve regularly-spaced major stops like Tachikawa and Kokubunji. Some of these trains drop to local service very far out, e.g. on the Ome branch, but it’s not LIRR-style 3-stops-then-nonstop.

A hypothetical Metro-North timetable on this model might make all stops New Haven-Stamford, and then stop at Greenwich, then maybe Port Chester or Rye, then New Rochelle, then Fordham, then the Manhattan stops. LIRR trains following this paradigm would likewise never skip Mineola and Jamaica, whereas in fact some rush hour LIRR trains don’t bother stopping at either.

What you describe in the last paragraph is also the model of NYC subway express lines – many local stops in the outer boroughs, then a few express stops further in. I agree that it makes sense for regional/commuter and long-distance rail too.

Very roughly with the same electrical system they can run two locals or one local and two expresses. They move more trains during peak by having more expresses. How many trains an hour does there have to be between Penn Station and Jamaica? If a few of them don’t stop in Jamaica that encourages people to avoid the trains that do stop in Jamaica. And gives them a slightly faster ride.

This is why I was incredibly frustrated when Metropark was rebuilt from the ground up a few years back with side platforms instead of islands. Besides the time penalty to Acelas of having to shift to the local track, it means any shift of NJ Transit operations away from zone expresses towards a Japanse model is locked in by problematic platform layouts.

In Japan they have many different stop patterns because they have so much demand that number of vehicles operated have reached track capacity, and as the trains can be filled up even after stopping at just a few stops, it make sense for the train to not observe the remaining numbers of stops and head directly to destination. But I don’t think the frequency of most US regional rail for commuter traffic have such amount of demand/capacity situation?

The Hikari services are basically divided into two service patterns: one hourly Hikari service runs Tokyo to Okayama, with stops including Shizuoka and Hamamatsu, and the regular big city stops, and then runs local Kyoto to Okayama. The other hourly Hikari is a Tokyo to Shin-Osaka service, with stops including Odawara or Toyohashi, and then running local Nagoya to Shin-Osaka. It’s in a way the utility player or “garbage man” of the Tokaido Shinkansen train service lineup, serving the tweener markets the Nozomi passes through but merits more than the 2tph Kodama.

While Japan have platform access control, there are still no requirement that passengers need to present at platform x minutes before departure, and even non-travellers can still get a platform ticket to access the platform

Alon did describe Shinkansen as “subway style” platform access control, which in Japan is afaik used for everything except rural stations. At least the JR East network also allows passengers to board using only Suica without buying anything ahead of time for unreserved seats, just like getting on a pretty much any other train (except rural pseudo-railbuses).

Even if it’s a design choice instead of a technological advancement, it’s one of the most futuristic feeling parts of the Shinkansen passenger experience. It feels like you’re getting on a subway (including trains that stop precisely where they should every time and platform screen doors), except the interior feels like a (very comfy) airplane, and when you arrive, you’re half way across the country, but it feels like you just go off the subway.

The fact that system with fixed pricing have the highest fare/km seems to imply that yield management actually lowers the average cost.

Tohoku, Joetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansen are one big branch with shared Tokyo-Omiya section

Also KTX branches and reverse branches heavily.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/79/KTX_linemap_en.svg

China has fixed pricing at low rates. And Germany has less dynamic pricing than France and the same approximate fares per p-km.

China is a bad comparison though because it’s a middle-income country. German pricing for ICE trains can be pretty dynamic. A trip like Berlin-Frankfurt can range from €30 to €140. I would call that dynamic. It also has the Bahncard which has a very high take-up, enabling cheaper trips for regular users. What does SNCF do? I’m guessing some kind of frequent flyer system?

The “dynaymic” fares in Germany are not yield management fares, because a certain Sparpreis costs the same, independently of the train (assuming that the fare is available).

There are two (well, three) levels of Bahncard; 25, 50 and 100; 25 and 50 give a respective discount; 100 is a general pass. These reductions do lead to a different fare price, but the ticket category is the same (in other words, there are no contingents for Bahncard 25 or Bahncard 50; there are, however, some seats in ICEs reserved for Bahncard 100 passengers, which can be used otherwise, but if someone with a Bahncard 100 comes, you’d have to leave that seat.

SNCF does have some discount cards (frequent traveller, elderly, youth), where the discount applies after a certain ticket category has been selected.

But DB will offer less Sparpreis tickets on a train where they can sell more expensive tickets…

I agree. KTX got more French/TGV influence than they got from Shinkansen not because of the technology choice or geopolitics but service structure, such as:

– Branching (as you mentioned);

– Multiple terminals in Seoul (Yongsan for KTX Honam Line, Cheongnyangni for KTX Gangneung Line, and SRT Suseo);

– Heavy emphasis on one-seat ride from the Capital;

– Relying on conventional rail track for big city access and branch line service (though some have been eliminated) and capacity issue on the shared segment near the Capital,

– Many mid-line smaller city stations built in “beet field” locations,

– No fare gates at stations, and;

– Fare structure (no integration with conventional rail service or metro rail service)

I think the only commonalities between KTX and Shinkansen would be heavy use of tunnels and elevated structure (probably due to mountainous topography) and adoption of EMU (though it was originally push-pull configuration like TGV or TGV-mod).

To be fair, the Seoul area is gargantuan and dominates South Korea far more than Paris dominates France…

I think the point is that unlike Tokyo, where the “termini” of the various Shinkansen are physically connected by rail at Tokyo Station, and through service is at least possible in theory, Seoul’s KTX/SRT lines truly terminate at different points in the city, and at least until the GTX regional rail service is substantially complete, there won’t be any physical connection to make through service feasible. More than the fact of the city’s size (undeniable though its dominance of South Korea is), the multiple termini have to be credited in part to the fact that the city is very multipolar (around Gangnam, Jongno, and Yeouido), and the poles are quite far apart (unlike Tokyo’s Minato, Chiyoda, and Shinjuku) with centers roughly corresponding to the stations. An upcoming one in Gangnam underneath Yeongdong-daero will bring KTX/SRT service from Suseo to Gangnam’s center.

But as Korean railway labor union have pointed out, such multi-terminal approach is killing the frequency and the separate booking platform by multiple companies are killing the convenient of railway travel, especially when one is travelling to/from lower demand branch/intermediate stations. Even if the SRT is extended via GTX into Seoul station (I forget was it part of the plan), their boarding area and ticketing will still be so vastly different that passengers cannot just arrive at Seoul Station and have an easy way to pick when will the next train to their destination be departing.

And then when it come to Tokyo, the challenge would be how to connect passengers from Chuo Shinkansen to Tohoku Shinkansen

Speak of which, Tokyo also have plans to make a new Shinkansen terminal at Shinjuku, but the cost made them think twice about it, and thus now they’re just trying to use the existing tracks and platforms and stations more efficiently.

But you can fill more seats, no?

I think there are already some doomsday predictions for the shinkansen expansion to Sapporo, with the high fares compared to the many budget airlines that operate Narita-New Chitose.

That said, JR East (eki-net) and JR Tokai both sell discounted tickets for early booking…

About France: The original idea of the high speed lines was to operate them with gas turbine-powered trains (the TGV 001 was a Turbotrain à Grande Vitesse). Fortunately, the oil shock in 1973 ended these ideas.

The reason for Paris – Lyon as first segment was because the main line was, despite 4-tracked over some distance, running at capacity. So, a new line was justified.

No intermediate stations… as soon as you have left the outer burbs of Paris, you run through no-mans land. Yes, Dijon is a bigger place, but too far off the route (but Dijon got served with TGVs, running towards Switzerland). The two new intermediate stations were pretty much political, to make believe that the touched Départements had their TGV to Paris.

The first station the TGV used in Lyon was Brotteaux, just about near the station throat of todays Part Dieu station. I’d have to look up when they built Part Dieu; there is more space than Brotteaux. Perrache is not suitable for a north-south connection, as it is on the other side of the Rhône river. It is, however, the terminal for some Paris-Lyon only TGVs.

A personal anecdote: About 2 weeks after the first TGV line opened, I got a railpass for France, to sample the TGV as a day trip. Taking the “Arbalète” from Zürich to Paris as first leg. But the regular line was closed, so we got detoured via Strasbourg – Nancy… the comfortable 1h40 or so connection shrank to a bit more than half an hour. So, no RER to the Gare de Lyon, but a Taxi; i told the driver that “je suis un peu pressé”… well, he deserved a generous tip… TGVs always required reservations, but with a railpass, I didn’t have one. However, they had a reservation vending machine at the platform, where you could buy one up to about 3 minutes before departure. Got one, got on the train, and on the way we were. The ride was uneventful, but a bit shaky (because they were using helical coil springs, vibrations got through (and for some time “TGV” stood for Train à Grandes Vibrations); they fixed that pretty quickly by switching to air bags… and since then, the TGVs run very smooth. From Lyon Brotteaux, I had a connection to the Catalan Talgo for Genève, from where I took one of the many ICs back to Zürich…

Anyway, the route towards the Southeast got expanded, and as part of the first segment south of Lyon, they built the bypass with the station at the Satolas airport (aka Lyon Saint-Exupéry). However, there are no trains between Satolas and Gare de Lyon; the trains stopping at Satolas use the Paris bypass (with stops in Marne la Valléé and CDG airport), and continue towards the North. Trains towards Avignon – Marseille and beyond either do not stop in Lyon at all, or they stop at Part Dieu.

Anyway, SNCF made the fatal error to hire phased out airline managers. That lead to the idiotic yield management (well, if a high speed rail system uses yield management, it is a sign that the service level is lousy, IMHO). This eventually lead to the OuiGo concept (which is ridiculously expensive to operate (blocking a whole platform for at least half an hour and needing a dozen staff at the station…). One has to consider OuiGo as a way of SNCF to block open access operators by gobbling up paths.

(the ironic thing is that SNCF exactly does with OuiGo_ES in Spain what they wanted to prevent with OuiGo (F) in France; a nice example of bigottery…).

I was on a train to Paris that stopped at Saint-Exupéry – could it be that they’ve changed the stopping pattern since then? It would’ve been either the summer of 2010 or the end of 2016.

And how come your TGV trip was Zurich-Paris-Lyon? Wouldn’t it have been faster to get from Zurich direct to Lyon via Geneva and then take the TGV to Paris?

I think of OuiGo as less conspiratorial than this, even though SNCF is conspiring about other things (RENFE electrical interference…). The entire discourse in France was about the need to innovate like low-cost airlines, and the Spinetta report asserts that Ryanair has lower per-seat-km costs than the TGV, when you exclude airport infrastructure but (I believe) include LGV infrastructure. “Lower costs at outlying airports” is common enough for Ryanair, so SNCF tried to do the same, never mind that rail works differently and at no point was the Gare de Lyon throat at capacity.

Zürich – Paris was the “good old” EC Arbalète; can’t remember whether it had Swiss or French cars. At that time, the only TGVs to Switzerland came to Genève. A bit later, they introduced the tricourant sets, which could go to Lausanne and Bern (-Zürich).

They may have changed the routing over the years, so Lyon Saint-Exupéry – Paris Gare de Lyon were/will be possible.

Thing is that they already had a low-cost variant, IdTGV, which worked absolutely well.

OuiGo caused a serious brouhaha. There are a considerable number of commuters between Avignon and Marseille. During the useful time (16:30 to 18:30), all of a sudden two third of the trains were made OuiGo, of course not accepting passes etc. I think they did find some solution, but not really satisfactory…

Assuming what the other commenter said about Ouigo is true then they aren’t really learning from LCC, the most important thing about LCC is the efficient and heavy use of vehicles reducing dwell time and saving on operational expense

Well, Ryanair has (at many but not all airports) quite personnel intensive “pre boarding zones” which take up the space needed to fit 189 people for an hour and a half, but then airports have more real estate to work with…

The trains on Corsica are to this day sometimes called “train a grand vibration” but then they are slow narrow gauge trains…

About Germany: As stated, high speed lines were built to support the classic network, and not as a system on its own. And, in particular, the Hannover – Würzburg line, was also used by IC (loco-hauled, 200 km/h) trains. From the beginning, the German high speed network consisted of NBS (Neubaustrecken, such as Hannover – Würzburg, or Frankfurt Flughafen – Köln), and ABS (Ausbaustrecken, such as Hannover – Hamburg, or Hamburg – Berlin, where the maximum speed was raised to 220 km/h or so, but not new builds).

The key feature of German high speed is that it was set up as a network from the beginning; of course, it had its roots in the IC network, where lines (with numbers) and timed connections were introduced. This allowed for more cities to get fast connections than with a dedicated high speed “network”. This also suits better with Germany’s polycentric structures.

The standard maximum speed on most high speed lines is 250 km/h. However, if there is a delay, the driver is allowed to do 280. That allows to catch up a few minutes, getting to the next node in time.

Germany’s high speed stands out with the comfort of the trains (ambiance, space, seats, etc.). And, the lack of yield management (selling a limited number of Sparpreis tickets is not yield management, because their price does not vary from train to train). (They say that under the Mehdorn era, they tried yield management, but it did backfire big time; in Germany, (and Switzerland, and the Netherlands), rail travel means “freedom”; something to really keep in mind).

A side note to Switzerland, and why there is no real high speed line: The Swiss principle is the Takt, and that leads to the principle “not as fast as possible, just as fast as necessary” … and it works…

I was alluding to the run-as-fast-as-necessary principle, talking about how it wouldn’t do much good to speed Zurich-Bern-Basel beyond 53-56 minutes on each connection. But this is also related to country size. Switzerland is small, so Zurich-Bern should be either 56 or 26-27 minutes, and getting to 27 requires 300 km/h and Korean levels of tunneling. But in Germany the cities are spaced farther apart, so it’s possible using 300-320 km/h running to get Berlin-Erfurt down to an hour and Leipzig-Erfurt down to 30 minutes, and likewise squeeze Stuttgart-Munich to an hour, Hanover-Bielefeld to 30 minutes, Bielefeld-Dortmund to 30 minutes, Hanover-Hamburg to 45 minutes, etc. (I’ve seen German rail advocates claim Hanover-Bielefeld can’t be done in less than 30 minutes because the average speed requires long nonstop stretches as in France, which is nonsense; it’s 100 km in flat terrain, doing it in 27 minutes is doable by comparison with Nagoya-Kyoto, which is a 285 km/h and not 300 km/h line.)

I don’t get why the speed have to be right less than 1 or 0.5 hours. If it is faster then it will be faster for passengers travelling between any points on the line, and schedule integrity and connection still can be achieved by passengers and trains waiting at station after finishing the trip faster

Because there’s a long tail of connections like St. Gallen-Biel, which gain nothing from making Zurich-Basel faster unless it fits into a new takt, which it doesn’t. Remember, here in Euro-land we’re very urban but “urban” means “historic urban area of 300,000,” especially in smaller countries that are not Denmark, whereas half of South Korea lives in metro Seoul an half of Japan lives in metro Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya.

It would still benefit quite a bit direct passengers, while connecting passengers journey time wouldn’t be penalized by shorter train travel time if they have to stay on platform a few more minutes.

Yeah, it would, but most passengers aren’t direct, and the cost of speedups isn’t zero. So if there’s money in the budget, it’s generally better to create more knots, as is the case for the Bahn 2035 plans.

Urban in the UK means >10000 people.

>but most passengers aren’t direct

Is there any data on this?

Go to the average Swiss interchange station and see how many people change trains

That is not really possible under the current ongoing pandemic.

Plus, even if there are one or two hundred passengers changing trains at train station, they would still be relatively minority of the entire train’s capacity?

I don’t think you understand how completely Takt-integrated Switzerland is, or how heavily used station tracks (and main line tracks, even by Japanese standards) are, or how heavy transfer traffic is in a very multi-polar network.

If a train runs “too fast” not only do passengers have to wait longer for connections — maybe having to make an extra break to find a place to wait in the station waiting for the connecting train to arrive — but there is nearly never a place in the station for the train to wait, while any immediate reversal and return would almost certainly conflict with heavy and Takt-locked traffic around the station.

Now if you were talking, say, a completey separate and non-integrated Zürich-Bern (or whatever) shuttle line with separate tracks and separate platforms from the rest of the network and captive trains, maybe that could work (oh, and “separate platforms” means “added trip time” because the only place to put new platforms is below existing station platforms) but that sort of thing has been proposed and studied and costed and not funded.

And then of course there is always this sort of nonsense: https://www.swissmetro-ng.org

If you strap people in and accelerate them at 9.81 ms ^-2 you can get the train to 300 km/h even in Switzerland…

Swissmetro: Hypyloop done right… Actually, they were pretty close to getting the concession for building the line, but then SBB (which was a partner) chickened out, in favour of Bahn2000 and the integrated Takt…

Could you do the Zurich-Bern-Basel triangle in 45min legs, with 15min frequencies? That way each train has Takt connections at one end (with trains alternating which one is connecting), and I would say the vast majority of journeys involve a destination at one of the core cities (i.e. there aren’t that many people travelling from a village near Bern to a village near Zurich). Yeah, a bit more complicated than the current system, but the travel time savings on the main trunk would be nothing to sneeze at.

I am talking about passenger spending extra time at transfer station waiting for connection still wouldn’t result in longer overall door to door time.

Trains can continue travel onward instead of immediately reversing

And so how much transfer traffic is there in actual? Are they more than 50% of the train?

@df1982: It would be feasible, but quite expensive, as it would involve some very long tunnels. Scheduling should be possible, but it would break the hourly nodes in Zürich, Basel and Bern.

Nick, you just don’t get it!

“Trains continue onward” on which tracks exactly? Either on the same segregated tracks (in which case just keep throwing money at tunnels forever) or … these off-Takt trains have to slot in on existing tracks with existing heavy traffic and so they have to be Takt-locked themselves. Contradiction.

There really are only two choices: segregated tracks and platforms, or Takt integration. Running random trains at random speeds at random times just isn’t an option.

Off-topic!, this shows only inter-regional passenger traffic of Switzerland, not S-Bahn and no freight: https://www.fahrplanfelder.ch/fileadmin/fap_pdf/Netzgrafik/Netzgrafik2021.pdf

Here’s what a how an section of existing 4-track-narrowing-to-2-track-back-to-4-track line is presently scheduled (Bern-Aarau, shown in as “OO” and “AA”) which is progressively being rebuilt to four tracks throughout. You can’t just throw random extra trains into that, before or after the build-out. It’s the same everywhere you’d want to run more trains — there are so many trains already.

Not to mention that mixing speeds eats capacity faster than having everything swim at more or less the same speed…

If you mean coordination between different trains on same tracks, shouldn’t speed boost affect all trains sharing the same tracks and thus, let say if a segment travel time is shortened to 21 minutes instead of 28 minutes, isn’t it possible for all trains there from other direction to shift their schedule and meet at that station at :23 and :53 instead of :30 and :00?

No. This shift only works if you expect connections to happen in just one direction. As soon as connections happen in more than one direction, you lose the ability to connect if you shift times too much.

Given trains in Switzerland appears to connect by one major backbone, couldn’t trains in every other directions be re-timed to match the sped up main corridor?

Thing is, the world’s fastest high speed trains operating at 350km/h, are already 60%+ faster than 220km/h. This is bigger than the difference in speed between conventional rail and high speed rail in Germany. Resulting in a number of longer distance travel pairs needing 4 or 5 hours while they could be done faster and attract more passengers.

And building a high speed trunk line to fit in conventional network only make sense if you are building a conventional speed network instead of a high speed network. Polycentric is no excuse of only building only a line between. Not to mention important Germany cities from Rhine-Ruhr to Frankfurt to Stuttgart to Munich and from Rhine-Ruhr to Hanover to Berlin are on a line. Those who plan and build Germany’s high speed network just choose to build high speed lines within conventional network instead of creating a new high speed network.

The speed gains of 350 km/h vs 300 km/h are minimal. It’s much more worthwhile to speed up slower sections. Or to replace dead end stations with through stations. Which, incidentally, is one of the components of Germany’s most controversial railway project, Stuttgart 21

I’m talking about lines that only run at 220km/h. 250 is a bit better but still there is that

Those are not the speed bottlenecks

new track would sitll solve any speed bottlenecks even below them?

Why does the Sparpreis not count as yield management? In my experience, unless you’re travelling on a Friday or other peak times you have the option of a full price flexi-fare (meaning it’s valid for any train and you can cancel with a refund), and a Sparpreis attached to a specific itinerary. Up until a few days before departure the Sparpreis will usually offer significant discounts over the full fare, but the prices for these tickets ramp up the fuller the train gets. This sounds like yield management to me. It’s exactly what most airlines do.

And it makes a difference for travellers. When I studied in Germany I basically never caught an ICE because it was prohibitively expensive, and discount tickets were hard to come by. Nowadays it only requires a little bit of advanced planning and avoidance of peak travel times to be able to find a reasonably priced ticket.

Because a Sparpreis for a certain relation always costs the same. Yield management has variable pricing for each and every individual train.

That’s splitting hairs, though. You look up a certain train journey four weeks from departure and the Sparpreis is €30. Then look again two weeks later and it’s gone up to €50, while the flexi price remains the same at €100 (or whatever). It might be a little less arcane than France or the UK, but it’s still yield management, and it’s exactly what DB does for intercity journeys.

Just of curiosity, what is the problem with dynamic pricing? I think most of the academic literature is in favor. It is basically pricing scarce high-demand tickets more, and ensuring fewer in-demand trains don’t run empty. Sure, it is very annoying as a tourist, and has real costs in ease of use, but to me, those drawbacks are much smaller than the extra efficiency gains that bring very real savings for people that take less in demand trains. It has of course to be combined with real infrastructure to buy (occasionally more expensive) tickets if you just show up for the train, but that seems very feasible. After all, no one suggests year-round fixed prices on oranges, but let the price fall and rise with supply and demand. And everywhere in the world (I know no exception), high-speed rail is basically already so expensive that it is out-pricing lower income indivduals (with both China and Japan being very obvious examples).

The kind of half-assed promotion (and holiday etc) tickets that German, Japanese, and Taiwanese high speed rail use to fill empty trains seem like a very bad compromise, to solve similar problems. The Taiwanese also have so underpriced trains on some routs that it seems as like 50% of days are sold out completely when tickets are released a few months early.

In particular, if you one is in favor of high frequencies over the entire day the case for dynamic pricing seems to be even stronger, as all those empty trains at less-in-demand hours then can outcompete intercity buses, airplanes, and cars on price (poor people taking a late evening train for slightly less, than they would have spent on a much longer but more convenient timed bus).

“dynamic pricing” in the sense of yield management is really bad, because it prevents any kind of flexibility. It has some very limited reason to be when there is maybe one or two trains per day. But for more dense schedules, it is pure poison.

There are means to fill up lower use trains, but such tickets should not be tied to a specific train (example, a ticket not valid before 9:00, to relieve the morning peak).

“dynamic pricing” is also not really working within a network. There is always some travel before the high speed train, and some after. “dynamic pricing” can not properly include that.

“dynamic pricing” leads to a rather complicated fare structure, where the cost to maintain and enforce can be higher than its gains.

And, as said elsewhere, the worst a rail operator can get is a phased out airline manager… you find proof all over the world…

Are you sure? An obvious comparison is indeed airlines, which operate with a network structure, and with very frequent schedules.

European airlines had pretty much-fixed prices much like trains until the 1980s, and then it was also out pricing nearly everyone except the upper-middle class. The growth of airlines competing on price may have been disastrous for train travel but has certainly been very beneficial for the opportunities of low-income people to travel. So if anything, I think the history of air travel, really highlights the advantages with dynamic pricing. Do anyone really want to turn airline travel back to the 1970s and 1980s?

The example of dynamic pricing I am most familiar with is Sweden, where it seems to work pretty well (China seems to use It pretty much all over the system, though the maximum price seems quite low, so trains still frequently sell out). It breaks down when there are massive delays, but then the companies are in practice pretty flexible (and the real scandal is the frequent system-wide delays).