Curves in Fast Zones

I wrote nearly five years ago that the lowest-hanging fruit for speeding up trains are in the slowest sections. This remains true, but as I (and Devin Wilkins) turn crayon into a real proposal, it’s clear what the second-lowest hanging fruit is: curves in otherwise fast sections. Fixing such curves sometimes saves more than a minute each, for costs that are not usually onerous.

The reason for this is that curves in fast zones tend to occur on a particular kind of legacy line. The line was built to high standards in mostly flat terrain, and therefore has long straight sections, or sections with atypically gentle curves. Between these sections the curves were fast for the time; in the United States, high standards for the 19th century meant curves of radius 1,746 meters, at which point each 100′ (30.48 meters) of track distance correspond to one degree of change in azimuth; 30.48*180/pi = 1,746.38. For much more information about speed zones, read this post from four weeks ago first; I’m going to mention some terminology from there without further definitions.

These curves are never good enough for high-speed rail. The Tokaido Shinkansen was built with 2,500 meter curves, and requires exceptional superelevation and a moderate degree of tilting (called active suspension) to reach 285 km/h. This lateral acceleration, 2.5 m/s^2, can’t really be achieved on ordinary high-speed rolling stock, and the options for it always incur higher acquisition and operating costs, or buying sole-sourced Japanese technology at much higher prices than are available to Japan Railways. In practice, the highest number that can be acheived with multi-vendor technology is around 2.07 m/s^2, or at lower speed around 2.2; 1,746*2.07 = 3,614.22, which corresponds to 60.12 m/s, or 216 km/h.

If a single such curve appears between two long, straight sections, then the slowdown penalty for it is 23.6 seconds from a top speed of 300 km/h, 35.5 from a top speed of 320 km/h, or 67 seconds from a top speed of 360 km/h. The curve itself is not instantaneous but has a few seconds of cruising at the lower speed, and this adds a few seconds of penalty as well.

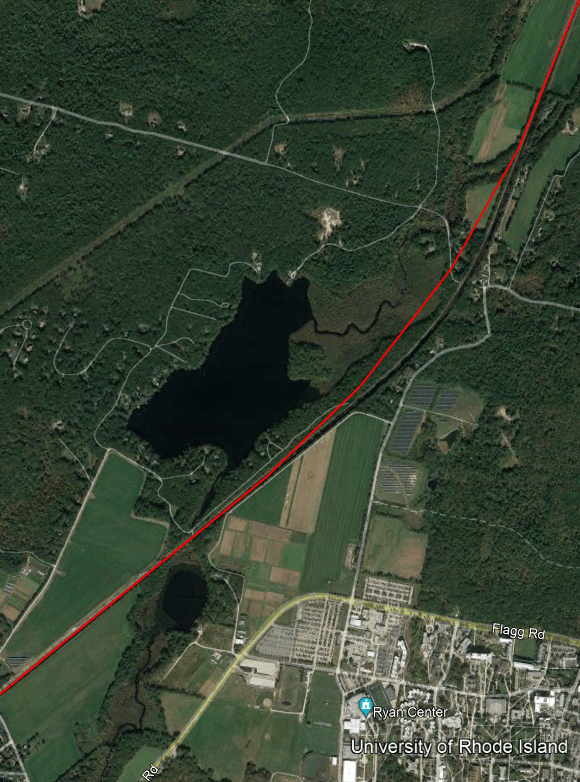

Case in point: the curve between Kingston and Wickford Junction in South County, Rhode Island is such a curve. The red line below denotes a 4 km radius curve, good for a little more than 320 km/h (360 with tilt), deviating from the black line of the existing curve.

The length of the existing curve is about 1.3 km, so to the above penalties, add 6 seconds if the top speed is 300 km/h, 7 if it’s 320, or 8.7 if it’s 360 (in which case the curve needs to be a bit wider unless tilting is used). If it’s not possible to build a wider curve than this, then from a top speed of 360 km/h, the 320 km/h slowdown adds 10 seconds of travel time, including a small penalty for the 1.3 km of the curve and a larger one for acceleration and deceleration; thus, widening the curve from the existing one to 4 km radius actually has a larger effect if the top speed on both sides is intended to be 360 and not 320 km/h.

The inside of this curve is not very developed. This is just about the lowest-density part of the Northeast Corridor. I-95 has four rather than six lanes here. Land acquisition for curve easement is considerably easier than in higher-density sprawl in New Jersey or Connecticut west of New Haven.

The same situation occurs north of Providence, on the Providence Line. There’s a succession of these 1,746 meter curves, sometimes slightly tighter, between Mansfield and Canton. The Canton Viaduct curve is unfixable, but the curves farther to the south are at-grade, with little in the way; there are five or six such curves (the sixth is just south of the viaduct and therefore less relevant) and fixing all of them together would save intercity trains around 1:15.

For context, 1.3 km of at-grade construction in South County with minimal land acquisition should not cost more than $50 million, even with the need to stage construction so that the new alignment can be rapidly connected to the old one during the switchover. Saving more than a minute for $50 million, or even saving 42 seconds for $50 million, is around 1.5 orders of magnitude more cost-effective than the Frederick Douglass Tunnel in Baltimore ($6 billion for 2.5 minutes); there aren’t a lot of places where it’s possible to save so much time at this little cost.

It creates a weird situation in which while the best place to invest in physical infrastructure is near urban stations to allow trains to approach at 50-80 km/h and not 15-25, the next best is to relieve 210 km/h speed zones that should be 300 km/h or more. It’s the curvy sections with long stretches of 120-160 km/h that are usually more difficult to fix.

Going and sensibly handling the interests of people who properly live in the countryside is something our governments have found very challenging.

And while being flexible and making bespoke changes is a good idea – also its a good space for steamrolling as few votes are at stake.

That said the left winning over the farmers will create a very interesting dynamic at the next election in the UK. Farmers sticking up massive billboards for left wing candidates next to the motorway will be good for the left and will get us a lot of votes.

How does one fix such a curve? Is it possible without shutting the line for a somewhat extended period?

Maybe you can tear up and replace the “inner” track of the curve while preserving service on the “outer” track, then repeat the other way?

Would it be possible to build the new curve mostly separately, then do the final segments on the ends over night?

I’m not sure how much work it is to do that, but people have switched tracks from running elevated to into a tunnel overnight before.

In the example in the image, you build the line on the inside of the curve – there’s enough separation that the civils shouldn’t require much disruption. The last bits connecting the curve to the line may be troublesome, I’m not sure.

You just need to do a punctual operation where you remove the old section on both ends and the replace it with a new one that connects to the new line. It is not very different from the work you would need to do to say, replace a switch. In Switzerland they would typically do this over a week-end where they stop traffic.

“fixing all of them together would save intercity trains around 1:15”

Is this figure correct? Above, your calculations seem to indicate that each curve saves no more than 90s, so that 1:15 corresponds to at least 50 curves.

I was wondering the same. Is the 1:15 figure a typo, or is that what you can save in combination with other speed improvements.

1 minute 15 seconds.

Yeah, this. 75 seconds, not minutes.

I think framing this as a steal vs. a lot of other infra spending is important, but difficult, at least in North America. As we well know, the U.S. doesn’t build a lot of rail infrastructure, and what we do build more of–roads–produces results that are (I would imagine) a lot more difficult to model, so pols and DOTs can often sell road projects as just “improving congestion”, without explicating how many minutes, how long the “improvement” can be expected to last, etc.

Some roadway projects do say “will save x minutes on commutes from Abc to Def”, but that gets lost in the wash. However–if the U.S. actually had meaningful rail scheduling, or if a line is purely for passengers–a definite, measurable improvement is possible. The fact that public spending on infrastructure can lead to a quantifiable output is not something that I think most Americans are used to either expecting or anticipating; that rail makes it possible ought to be a saleable point.

From the picture included with the post I saw “wetlands”. Turn on terrain, in Google maps they were avoiding the swamp and built the least amount of berm. Through the swamp. It didn’t matter until recently because it was diesel hauled. That’s going to be a bit more expensive than your guesstimate because it’s going to be going through a swamp. I’m imagining an elevated structure to allow the floods to flood and the wildlife to do their things. There’s remediating the old berm too. Still cheaper than a tunnel but it’s not going to be 50 million dollars either.

…. Through a swamp. I’m seeing a decade or two of environmental review.

Very wealthy area too looking at some of the houses. Going to run into a lot of difficulties at the community meetings – and if you don’t have community meetings it’s the kind of people who could lobby privately for sure.

If there are no community meetings in your Draft Environmental Impact Statement anybody/everybody will sue because it didn’t include community meetings.

As you implicitly said, civil engineers already knew how to drain wetlands and build causeways through them before the earliest steam-hauled railways were built. In this case, you outright happen to already have “for free” a rail line on which to bring in the fill needed for the embankment. This project should be very easy. The berm of the existing alignment can be left in place — why would you spend any effort changing it?

It’s the politics that is the hard bit – not the physical work of building a causeway over the wetlands.

From the looks of the terrain-view map they didn’t drain wetlands when the railroad came through almost 200 years ago. They put it up on a berm. We can’t fill in or drain wetlands willy-nilly anymore. Because wetlands are environmentally sensitive important parts of the river’s ecology these days, not a worthless swamp. Alter a chunk of the swamp you have to remediate that. Taking out some of the old berm for instance. So there is someplace for the floods to flood and for the wildlife to do it’s things. Abandon a railroad right of way you have to remediate all the crud that has accumulated around a railroad too.

It’s not going to be plopping gravel and tracks down.

Most realistically the minimum viable plan would be to put the entire bit over the wetlands on a nice looking bridge and to completely remove the existing berm.

Something to be negotiated during the Major Investment Study, Draft Environmental Impact Study and approved in the Final Environmental Impact. And the multiple lawsuits. The berm makes a good sound barrier for the clump of suburbia south of the existing tracks. And could provide access to the Chipuxet River Nature Reserve. They can hash it out during the decade long study period. And in the lawsuit filings.

In America at least, some low hanging fruit (things other countries just naturally would have done already) is to simply upgrade crossing gates to quad gates or grade separation so that trains are legally allowed to travel at higher speeds. This is likely more true along straight alignments in the Midwest

Electrification is also a very low hanging fruit however I do not know if that is remotely possible given the politics surrounding freight company owned rail alignments.

It does make me wonder what the national policy should be toward existing freight rail infrastructure. Strike a deal with freight railroads for time slots? Use legal authority to require them to accommodate passenger trains? Buy the freight tracks out from the companies? Just build entirely new passenger rail right of ways?

There are no “time slots” over long distances. The fast trains catch up to the slow trains.

I took “the Canadian” VIA long distance train in 2017, which mostly follows the CN line between Toronto and Vancouver, and throughout the entire route, oncoming trains pushing us to passing sidings were no more than 2 hours apart at any time of night or day (12 trains daily). At that frequency, we caught up to a lot of freight trains travelling the same direction (which we usually couldn’t pass).

Amtrak has to replace the 155-year-old 3-track tunnels under Baltimore with a new 4-track tunnel that also lets trains increase from 30 to 100 mph several miles sooner and the same its it must build a 2 -track new tunnels & fix the old tunnels having 2-tracks under the Hudson River.

(The new Douglass Tunnel has been descoped from four to two tracks to limit the cost blowout.)

Yeah, it’s a pretty serious increase in speed, but at the end of the day it’s 2.5 minutes for $6 billion. It’d be a great project at $1 billion, since much of that capital cost would be netteed out in lower maintenance costs. It’s just not a great $6 billion one.

Alon are there any countries that are good at solving these kinds of problems with not particularly sexy solutions. Italy?

Italy just builds greenfield high-speed lines. Not a lot of places need to convert a medium-speed line to a high-speed line; Germany is doing it on Berlin-Hanover.

What about England, the Great Western lines west of Bristol?

Personally since capacity is a bigger issue than speed for England, I think HS2B was always mistake compared to just extending the Midland Mainline’s 4 track to Sheffield with a high speed corridor north of Kettering.

I think even in the example in this discussion while there will undoubtedly be political negotiations around the wetlands the people living there will at least likely use the existing train service.

They will be more sympathetic than rich people who don’t live near a train station for sure.

Plus improvements to the existing line also should improve the semi-fast services that they currently and will continue to use so there is at least part of a quid-pro-quo already.

<blockquote>Italy just builds greenfield high-speed lines.</blockquote>

That’s not remotely the case!

Marco Chitti, who inexplicably continues to post on the xitter Nazi Hellsite, has been providing fabulous examples for years of Italian “continuous improvements” (as opposed to high speed “not disruption (whatever than means)”) in line speeds and capacities, starting in the early 1900s. (I look for stuff he’s written <a href=”https://nitter.poast.org/ChittiMarco/”>here</a>, but it’s <a href=”https://nitter.poast.org/ChittiMarco/search?f=tweets&q=direttissime”>a slog to find stuff</a> and deal with the stupid xitter format of threads.

It’s not all about not the Direttissime, and the direttissime themselves aren’t “draw a line from A to B and run at 350kmh” but far more in the style of strategic cutoffs, incrementally assembled into longer high-speed sections over many decades. And quite successfully.

(I’m sure the new GUI-ish but still preview-free wordpress comment plugin is going to screw up my unfrozen caveman raw html. Also, it totally fucks up undo/redo. If you’re going to try to comment here, I suggest using an external editor and only pasting into the trying-to-be-too-clever blog comment box when you’re done.)

I’ve been trying to get him to come to the Fediverse for a year :(.

Marco’s stuff on Italy is what I was thinking of! England has an insane number of legacy quadtracks.

N/B I’m not against HS2 at all, its just that the political fallout is so catastrophic I don’t think Labour will necessarily touch it. And I have learnt that the UK rail industry is filled with bad actors who have refused to deal with their role in enabling this disaster. Hence “half-measures”.

I don’t want to comment on the eastern leg as I am much less familiar with it. However I don’t think HS2 phase two has ever done much if anything for rail capacity in the Western side of the country.

I guess that it bypasses Stafford helps – but I would have thought a classic compatible four tracking of that section would be a better bang for your buck that could hopefully be used by all the express trains and perhaps even the cross country ones.

WCML handles a lot of freight, commuter services (esp in London orbit), intercity between the 3 largest urban areas, plus Glasgow, Lake district, North wales. And branching from hell to service all of them.

UK outside the London area is not at capacity, mostly because we haven’t properly wired and signalled everything. But as we talked before the UK rail industry is still very Victorian and does Victorian solutions.

Your hand-drawn red line makes it look a lot easier than it is in fact – if it departs from the tangents at the same locations, it will have the same radius. In order to increase the radius, you need to start and end the curve further back, which increases the length of the reconstruction significantly.

Is there a similar argument to be made where the track geometry is already straight, but trains are not running at full speed due to signaling or other legacy issues? What needs to happen? Higher quality track along with updated PTC?

LIRR between Penn Station and Jamaica comes to mind – especially when riding east, the trains poke along around 45 mph or so. On the other hand, Caltrain out of San Francisco, kicks it up to 79 mph right after 22nd street.

Yeah, signaling is a very low-hanging electronics-before-concrete fruit, with a lot of non-obvious improvements that can be done (many of which already are being done, at elevated cost where the MTA or Amtrak is involved).

Everything on the NEC is using ACSES.

Yes, but ACSES is not the same as the signal block system, which uses discrete speed steps (20, 30, 45 mph, etc.) and assumes trains brake at the rate of freight trains on shared lines, with individual train braking curve capability possible but not yet used.

It’s not 2001 anymore. Supposedly everything with scheduled passenger service or carrying hazardous material etc. has something more sophisticated than block signals. It’s ACSES for the passenger trains and some of the freight trains, on the NEC. Whatever the freight companies are calling their system can interoperate in ACSES territory. It seems the freight companies settled on ITS. Interoperable Train Control.

ACSES is a train protection system, not a signaling system (whereas ETCS is both). It really is a block signal system; ACSES’s role is to enforce the cab signals incrementally upgraded from the original PRR system.

What’s the functional difference. The trains using ITS or ACSES or both aren’t getting their information by osmosis or Ouiji board.

It’s lower-capacity because of those legacy issues (but again, that’s fixable without full replacement of the signals).

Block signalling is used in Britain to run 14tph off peak at up to 200km/h.

Obviously in cab signalling and moving away from blocks is better, but it’s perfectly possible to run a fast, safe and frequent rail service using them.

You didn’t answer the question. What’s the functional difference between ACSES and ETCS?

One of them is a big black box that attempts to prevent the trains from crashing into each other. the other one is a big black box that attempts to prevent the trains from crashing into each other. Or off the tracks or into work crews. ITS does the same thing.

ETCS is also a signaling system with its own blocks. Relevantly, ETCS comes equipped with “who am I?” identification to calculate each train’s individual braking curve, whereas ACSES could have that functionality but doesn’t.

ACSES sends different messages to different trains. To send different messages to different trains it has to be able to identify each one.

The floppy catenary hanging off 1930s era poles limits speed to 135 mph many many places west/south of New York. Replacing it and converting to 60Hz has been on Amtrak’s wishlist since there has been an Amtrak. Upgrade the catenary, the trackbed needs to be rehabilitated. You then need a new fleet to take advantage of it.

Well, the existing Acela could take advantage of speeds >135 mph, but you’re right we might as well for the new Acela 2 and go up to 160+ mph.

This also begs the question, but the Siemen’s Viaggio cars are good for 230 km/h (145 mph) in Europe on RailJet trains. What extra equipment would it take for the new Amtrak Airo sets to be upgraded from 125 mph to 145 mph limit? This also falls into the electronics-before-concrete area, right?

They’ve been talking about how they are gonna make New York to Washington D.C. since Lyndon Johnson was president. I don’t hold much hope of anybody doing anything. My choice for replacing antique Amfleets running on the NEC was to replace them with more of the new Acela trains. They didn’t do that.

Yeah, I agree 110% that Regionals should’ve been replaced with more Acela 2 trains. The tilting would also help on the Keystone Corridor, where speed is only 110 mph due to curves. Strangely, the Avelia Liberty contract doesn’t seem to include options beyond 28 trainsets.

I recently watched an interesting video in German about lifting the speed of a track from 160km/h to 200km/h. There is also a section about curves: https://youtu.be/cI5n6vGx70A?t=164

I was wondering, when are you gonna post your Twitch TV Video from November 18 on Youtube?

Anything that involves changing the use of land is a minefield in New England. Even shifting a rail line 100 feet from it’s current location could be extraordinarily complicated. New Englanders have learned how to kill project they don’t like with a thousand articles, committee hearings, and lawsuits. Ironically, this would all be easier politically south of NYC.