Serving Metro-North Fordham Station

In the Bronx, the Metro-North Harlem Line runs north-south, west of the 2/5 subway lines on White Plains Road and east of the 4 on Jerome Avenue and the B/D on Grand Concourse. It makes multiple stops, all served rather infrequently, currently about every half hour, with some hourly midday gaps, at premium fare. The north-south bus lines most directly parallel to the line, the Bx15 and Bx41, ranked #20 and #24 respectively in ridership on the New York City Transit system in 2019, though both have lost considerable ground since the pandemic. Overall, there is serious if not extremely high demand for service at those stations. There is already a fair amount of reverse-peak ridership: while those half-hourly frequencies can’t compete with the subway for service to Manhattan, they are the only non-car option for reverse-peak service to White Plains, and Fordham gets additional frequencies as well as some trains to Stamford. A city report from 2011 says that Fordham has 51 inbound passengers and 3,055 outbound ones boarding per weekday on Metro-North. Figuring out how to improve service in the Bronx requires a paradigm shift in how commuter rail is conceived in North America. Fordham’s reverse-peak service is a genuinely hard scheduling question, which we’re having to wrestle with as we’re proposing a (much) faster and smoother set of timetables for Northeast Corridor trains. Together, they make for a nontrivial exercise in tradeoffs on a busy commuter line, in which all options leave something to be desired.

Harlem Line local service

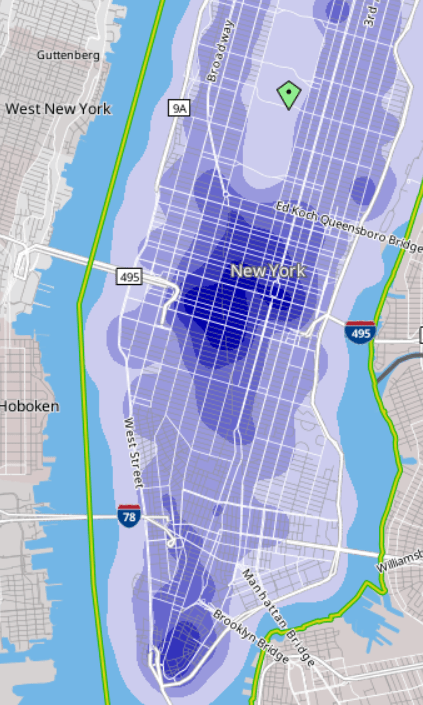

The bulk of demand from Fordham is local service, mostly toward Manhattan. The area is a bedroom community: within 1 km of the station at Park and Fordham there are 35,338 employed residents and only 22,515 jobs as of 2019; the largest destination is Manhattan (12,734 commuters), followed by the Bronx (7,744), then the rest of the city (8,069 across three boroughs), and only then Westchester (2,207), Long Island (1,660), and Connecticut (220). But to an extent, the station’s shed is larger for reverse-commute service, because people can connect from the Bx12 bus, which ranked second in the city behind the M15 in both 2019 and 2022; in contrast, Manhattan-bound commuters are taking the subway if they live well east or west of the station along Fordham. Nonetheless, the dominance of commutes to city destinations means that the most important service is to the rest of the city.

Indeed, the nearest subway stations have high subway ridership. The city report linked in the lede cites ridership of 11,521 on the B/D and another 12,560 on the 4 every weekday, as of 2012; both stations saw declines by 2019. The West Bronx’s hilly terrain makes these stations imperfect substitutes for each other and for the Metro-North station, despite the overlap in the walk sheds – along Fordham, Park is 600 meters from the Concourse and 950 from Jerome. Nonetheless, “roughly the same as either of the Fordham stations on the subway” should be a first-order estimate for the ridership potential; better Metro-North service would provide a much faster option to East Harlem and Grand Central, but conversely require an awkward transfer to get to points south, which predominate among destinations of workers from the area, who tilt working-class and therefore peak in Midtown South and not in the 50s:

Adding up all the Bronx stations on the line – Wakefield, Woodlawn, Williams Bridge, Botanical Garden, Fordham, Tremont, Melrose – we get 170,049 employed residents (as always, as of 2019), of whom 62,837 work in Manhattan. The line is overall in a subway desert, close to the 4 and B/D but along hills, and not so close to the 2/5 to the east; several tens of thousands of boardings are plausible if service is improved. For comparison, the combination of Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess Counties has 115,185 Manhattan-bound commuters, split across the Harlem Line, the Hudson Line, and the inner New Haven Line. The Bronx is thus likely to take a majority of Manhattan-bound ridership on the Harlem Line, though not an overwhelming one.

To serve all this latent demand, it is obligatory to run more local service. A minimum service frequency of a train every 10 minutes is required. The current outbound schedule is 20 minutes from Grand Central to Fordham, and about four of those are a slowdown in the Grand Central throat that can be waived (the current speed limit is 10 miles per hour for the last mile; the infrastructure can largely fit trains running three times that fast almost all the way to the bumpers). Lower frequency than this would not really make use of the line’s speed.

Moreover, using the track chart as of 2015 and current (derated) M7 technical performance, the technical trip time is 18 minutes, over which 20 minutes is not too onerously padded; but removing the derating and the four gratuitous minutes crawling into and out of Grand Central, this is about 14 minutes, with some pad. The speed zones can be further increased by using modern values of cant and cant deficiency on curves, but the difference isn’t very large, only 40 seconds, since this is a section with frequent stops. It’s fast, and to reinforce this, even higher frequency may be warranted, a train every 7.5 or 6 or even 5 minutes.

There is room on the tracks for all of this. The issue is that this requires dedicating the local tracks on the Harlem Line in the Bronx to local service, instead of having trains pass the platforms without stopping. This, in turn, requires slowing down some trains from Westchester to make more local stops. Current peak traffic on the Harlem Line is 15 trains per hour, of which 14 run past Mount Vernon West, the current northern limit of the four-track section, and 13 don’t stop in the Bronx at all. The line has three tracks through past Crestwood, and the stations are set up with room for a fourth track, but a full 10 trains per hour, including one that stops in the Bronx, run past Crestwood. In theory it’s possible to run 12 trains per hour to Mount Vernon West making all stops, and 12 trains past it skipping Bronx stops; this slows down the express trains from White Plains, which currently skip seven stops south of White Plains to Mount Vernon West inclusive, but higher speeds in the Bronx, speeding up the Grand Central throat, higher frequency, and lower schedule padding would together lead to improvements in trip times. However, this introduces a new set of problems, for which we need to consider the New Haven Line too.

Harlem Line express service and the New Haven Line

Currently, the New Haven Line runs 20 trains per hour into Grand Central at the peak. This number will go down after Penn Station Access opens in 2027, but not massively; a split of 6-8 trains per hour into Penn Station and 16-18 into Grand Central, with the new service mildly increasing total throughput, is reasonable.

Today, New Haven Line locals stop at Fordham, and nowhere else in the Bronx. This is inherited from the trackage rights agreement between the New York Central and the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, allowing the latter to make only one stop in the Bronx on the former’s territory; it used to be Woodlawn, the branch point, but has been moved to Fordham, which has busier reverse-peak traffic. The two railroads merged in 1969, and all service is currently run by Metro-North, but the practice persists. This is not necessarily stupid: the New Haven locals are long – Stamford is 53 km from Grand Central, 50% farther than White Plains – and a system in which the New Haven trains are more express than the Harlem trains is not by itself stupid, depending on other system constraints. Unfortunately, this setup introduces all manners of constraints into the system:

- Fordham is a local-only station, and thus New Haven locals have to use the local tracks, using awkwardly-placed switches to get between the express and the local tracks. In fact, all stations up to and including Woodlawn are local-only; the first station with platforms on the express tracks is Wakefield, just north of the split between the two lines.

- If there are 12 Harlem Line trains per hour expressing through the Bronx, then the New Haven Line is limited to about 12 trains per hour as well unless the local trains make all the Bronx local stops.

- The Hudson Line has a flat junction with the Harlem Line at Mott Haven Junction, which means that any regular schedule has to have gaps to let Hudson Line trains pass; current peak Hudson Line traffic is 11 trains per hour, but it was 14 before corona.

This leads to a number of different options, each problematic in its own way.

Maximum separation

In this schedule, all Harlem Line trains run local, and all New Haven Line trains run express in the Bronx. This is the easiest to timetable – the junction between the two lines, unlike Mott Haven, is grade-separated. This also requires splitting the Hudson Line between local and express tracks, so delays will still propagate in any situation unless the Hudson Line is moved to the Empire Connection (6-8 trains per hour can stay on the current route); but in a future with Penn Station Access West, building such service, it does allow for neat separation of the routes, and I usually crayon it this way in very high-investment scenarios with multiple through-running tunnels.

But in the near future, it is a massive slowdown for Harlem Line riders who currently have express service from White Plains to Manhattan. The current peak timetable has a 15-minute difference between local and express trains on this section; this figure is padded but not massively so, and conversely, higher speeds on curves increase the express train speed premium.

It also severs the connection between the Bronx and the New Haven Line, unless passengers take east-west buses to the Penn Station Access stations. It is possible to add infill at Wakefield on the New Haven Line: this is north of the junction with the Harlem Line, but barely, so the separation between the lines is short, and a transfer station is feasible. But it wouldn’t be a cross-platform transfer, and so Fordham-Stamford service would still be degraded.

Locals run local

The New Haven Line locals can make local stops in the Bronx. It’s a slowdown of a few minutes for those trains – the current outbound timetable is 18 minutes from Grand Central to Fordham, two minutes faster than on Harlem Line locals while skipping Melrose and Tremont. Overall, it’s a slowdown of around six minutes; the current speed zones are 60 and 75 mph, and while raising the speed limits increases the extent of the slowdown (most of the track geometry is good for 160 km/h), getting new trainsets with better acceleration performance decreases it, and overall it’s likely a wash.

From there, the service pattern follows. New Haven Line locals to Grand Central have little reason to run more frequently than every 10 minutes at peak – the local stations are 30-60 minutes out of Grand Central today, and this is massively padded, but with the timetables Devin produced, fixing the Grand Central throat, New Rochelle would still be 20 minutes out on a local train (stopping at Fordham only as is the case today) and Stamford would be 45 minutes out. What’s more, there will be some local trains to Penn Station starting in three years, boosting the effective frequency to a train every five minutes, with a choice of Manhattan station if express trains can be made to stop at New Rochelle with a timed connection.

Now, if there are six local trains per hour in the Bronx going to Stamford, then the Harlem Line locals only take six trains per hour of their own, and then 12 trains should run express from Wakefield to Harlem. What they do to the north depends. The simplest option is to have all of them make all stops, which costs White Plains 7-8 minutes relative to the express stopping pattern. But if the line can be four-tracked to Crestwood, then half the trains can run local to White Plains and half can run nonstop between Wakefield or Mount Vernon West and White Plains. Two local stations, Scarsdale and Hartsdale, are in two-track territory, but timetabling a local to follow an express when both run every 10 minutes and there are only two local stops’ worth of speed difference is not hard.

The New Haven Line, meanwhile, gets 12 express trains per hour. Those match 12 express Harlem Line trains per hour, and then there’s no more room on the express tracks; Hudson Line trains have to use the local tracks and somehow find slots for the northbound trains to cross both express tracks at-grade.

Status quo

The status quo balances Bronx-Stamford connectivity with speed. Bear in mind, the New Haven Line today has truly massive timetable padding, to the point that making trains make all six stops in the Bronx and not just Fordham would still leave New Rochelle locals faster than they are today if the other speedup treatments were put into place. But the status quo would allow New Rochelle, Larchmont, Rye, and Greenwich to take maximum advantage of the speedup, which is good. The problem with it is that it forces New Haven Line locals to take slots from both the express tracks and the local tracks in the Bronx.

In this situation, the New Haven Line still runs six locals and 12 express trains to Grand Central per hour. The Harlem Line is reduced to six express trains through the Bronx and has to run 12 trains local. Transfers at Wakefield allow people in suburbs south of White Plains to get on a faster train, but this in effect reduces the effective peak-of-peak throughput from the suburbs to Manhattan to just six trains per hour.

Express Fordham station

Rebuilding Fordham as an express station means there’s no longer any need to figure out which trains stop there and which don’t: all would. Then the New Haven Line would run express and the Harlem would either run local or run a mix.

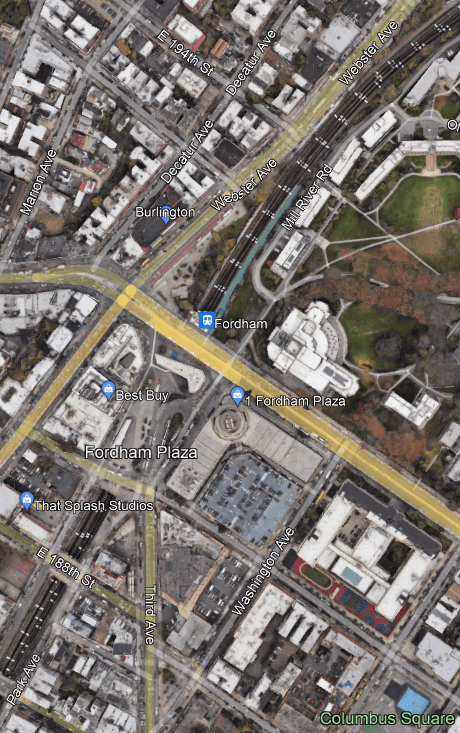

The problem is that Fordham is in a constrained location, where such a rebuild is hard:

The line is below-grade, with a tunnel from Fordham Road to 189th Street. The platforms are short and narrow, and partly overlap the tunnel. Any conversion has to involve two island platforms north of the tunnel, where there is room but only if the right-of-way is expanded a little, at the expense of some parkland, and possibly a lane of Webster Avenue. The cost would not be pretty, independently of the inability of the MTA to build anything on a reasonable budget.

That said, the timetables on the Northeast Corridor require some infrastructure intervention to smooth things, like grade-separating some junctions for hundreds of millions of dollars each. New Rochelle, which has only a local platform southbound, should almost certainly be rebuilt as a full express stop. So rebuilding Fordham is not out of the question, even if the cost is high (which it is).

In this situation, all New Haven Line trains should use the express tracks. Thus, as in the status quo alternative, the Harlem Line gets six express trains, the other trains having to run local. Potentially, there may be a schedule in which the New Haven Line runs 16 trains to Grand Central and eight to Penn Station, and then the Harlem Line can get eight local and eight express trains; but then the local trains have to be carrying the load well into Westchester, and four-tracking the line to Crestwood is likely obligatory.

The New Haven Line and intercity trains

The above analysis elides one important factor: intercity trains. The current practice in the United States is a three-way separation of urban rail, suburban commuter rail, and intercity rail, with fares designed to discourage riders from taking trains that are not in their sector. However, in much the same way the best industry practice is to charge mode-neutral fares within cities, it is also valuable to charge mode-neutral fares between them. In other words, it’s useful to look at the impact of permitting people with valid commuter rail tickets to take intercity trains, without seat reservations.

To be clear, this means that at rush hour, there are going to be standees on busy commuter routes including Stamford-New York and Trenton-New York. But it’s not necessarily bad. The intercity trip time in our timetables between Stamford and New York is around 29 minutes without high-speed bypasses; the standing time would be less than some subway riders endure today – in the morning rush hour the E train departs Jamaica Center full and takes 34 minutes to get to its first Manhattan stop. And then there’s the issue of capacity: commuter trains on the New Haven Line are eight cars long, intercity trains can be straightforwardly expanded to 16 cars by lengthening the platforms at a very small number of stations.

And if the intercity trains mop up some of the express commuter rail traffic, then the required service on the New Haven Line at rush hour greatly decreases. An intercity train, twice as long as a commuter train (albeit with somewhat fewer seats and less standing space per car), could plausibly displace so much commuter traffic that the peak traffic on the line could be reduced, say to 18 trains per hour from today’s 20. Moreover, the reduction would be disproportionately at longer distance: passengers west of Stamford would not have any replacement intercity train unless they backtracked, but passengers east of Stamford would likely switch. This way, the required New Haven Line traffic shrinks to 12 local trains per hour and six express trains; half the locals run to Penn Station and half to Grand Central, and all express trains run to Grand Central.

In that situation, we can rerun the scenarios for what to do about Fordham; the situation generally improves, since less commuter traffic is required. The maximum separation scenario finally permits actual separation – the Hudson Line would run on the express tracks into Grand Central and have to cross the southbound Harlem Line locals at Mott Haven Junction, with predictable gaps between trains. The locals-run-local scenario gives Harlem Line express trains more wiggle room to slot between New Haven Line express trains. The status quo option lets the Harlem Line run six local trains and 12 express trains, though that likely underserves the Bronx. Converting Fordham to an express stop straightforwardly works with zero, six, or 12 express Harlem Line trains per hour.

Or maybe not. It’s fine to assume that letting passengers get on a train that does Stamford-Penn Station in 29 minutes and New Haven-Penn Station in 57 for the price of a commuter pass is going to remove passengers from the express commuter trains and put them onto longer intercity trains. But by the same token, the massive speed improvements to the other stops could lead to an increase in peak demand. The current trip time to Stamford is 1:12 on a local train; cutting that to 45 minutes means so much faster trips to the suburbs in between that ridership could increase to the point of requiring even more service. I’m not convinced on this – the modal split for peak commutes to Manhattan is already very high (Metro-North claimed 80% in the 2000s), and these suburbs are incredibly NIMBY. But it’s worth considering. At the very least, more local service is easier to add to the timetable than more express service – locals to Grand Central don’t share tracks with intercities at all, and even locals to Penn Station only do on a controllable low-speed section in Queens.

Some history worth considering. In the 60s, when PRR ran all trains on their own tracks, one could buy 44 ride puncher unlimited flas tix from points on the Main Line as far as Paoli to NYC. They were good on all trains as walk ons. (the exceptions were the All Pullman Broadway, Pittsburgher, and through trains from south of DC. Thus when I commuted once a week or more between NYC and Philly I could ride in coach on the Senator, the various Congressionals etc. This also applied to the Clockers which were long strings of once luxury coaches randomly assembled into trains at Sunnyside with occasional Seaboard or other “its clean and fit” extra cars. Amtrak’s abolition of the Clockers sending riders to NJT toSEPTA connections at Trenton was IMHO a middle finger to riders who saw no value in the overpriced Acelas.) So, yes, single pricing any seat not on an Acela as a punch/flash on a monthly and selling walk up tix at commuter rates–which in turn should be subway fares within the 5 boros–would give ALL the riders a better deal, and since we are moving to fully electronic ticketing, apportioning the fare revenue is trivial.

Further ROW thoughts. Despite the grooss overpricing of all MTA related projects, yes,,Fordham andNew Rochelleneed to becomefull 4 track two island stations wih complete ADA compliance. Second,the Amtrak Hell Gate route needs to have the 3rd and 4th tracks restored, This will be a serious project because when the 4 trackmain was cut back to two, many curves were eased, so much re-engineering is needed including perhaps some property acquisition. Also the 4th track on Hell Gate it self should be restored.

Definitely having the same pricing for different intercity trains is bad.

I mean should Birmingham-London on an Avanti express train really cost the same as Birmingham-London via Banbury or via Northampton? And does that really make sense when the Avanti service is more congested?

And certainly shouldn’t doing Reading-Manchester via Oxford be cheaper than via London where you are on a less busy route throughout?

Yeah, London-Birmingham is the annoying case where it’s genuinely intercity. In Germany the fares are at this point different because of the 49€ ticket; I think they were pretty close before 2022.

That said, New York-New Haven is much more of a long-range commuter route than an intercity one. (I should possibly write a followup today about why I’m optimistic about NEC ridership and capacity.)

I think its reasonable to say that the regional/all-stop/kodama intercity service should have the same pricing as the commuter service from the same stations. Limited/hikari and express/nozomi services can have higher fares to reflect the fact that as faster/premium services they will have more demand.

Yeah that’s fair.

It’s probably reasonable for the via Banbury and via Northampton trains from London to Birmingham that take about 2 hours or a little more to cost the same.

I think in general for regional service having peak and off peak fares only aligned across modes is broadly sensible.

For intercity having advance, off peak and peak fares only with a maximum of two routes/cost levels with different costs seems like a decent balance. And either the two cost levels should probably be regional service vs intercity service or via London/New York/Paris vs not via those places.

Great write up, as always. I spent some time in Google Maps looking over Mott Haven to see if any kind of grade separation is feasible, and good lord it’s really constrained there. You have multiple bridges – E 144th, E 149th, and Grand Concourse, so I don’t think a “flyover” would be possible unless you closed at least one of them. Good luck with that. And then you have the IRT 2/5 lines running underneath 149th street, so you couldn’t really do a “dive under” either. You would have much better ease building a second flyover track at Woodlawn then you would doing a grade separation at Mott Haven. Alon – are you aware of any other location where a railroad has successfully grade separated in a location as constrained as Mott Haven?

If you want to win the argument in Britain that HS2 costs too much a good approach is to be able to go and say that some equivalent European project cost a lot less.

Much harder to make that argument if you are doing something meaningfully harder than anywhere else.

For the Hudson line trains in the locals run local scenario, it would still be possible to slot them on the northbound express tracks, therefore only having to have them cross the southbound tracks. As long as no local stops are reopened in Manhattan, any Harlem or New Haven express scheduled at the same time would use the local track and cross over to the express just north of Mott Haven Jcn.

Alon, I realize I’m making a request that I will contribute nothing to, but for a post like this some graphics showing the different service patterns – even at a very simplistic diagram level – would help immensely to grasp what you are talking about, instead of trying to mentally visualize what things like “six local trains per hour in the Bronx going to Stamford, then the Harlem Line locals only take six trains per hour of their own, and then 12 trains should run express from Wakefield to Harlem” actually means.

I concur. I think I’m usually good at following along, but kept getting lost on this one.

Yep, this wall of text article is hopeless unless you’re neck-deep in knowledge of the local environment already.

I have the same problem – making even simple diagrams is hard for those without the seemingly-simple skills. Do I understand that all too well.

how much do you think congestion pricing will effect ridership for commuter rail? hopefully it can fund some of these improvements once the lawsuits are over

For work trips, only on the margin. I can see it induce some recreational ridership for people in the suburbs who want to go out in Manhattan, but I don’t think it’s going to make a large difference. In London the most notable effect of congestion pricing on public transportation was that car traffic decreased so much that buses ran faster than scheduled.

“In London the most notable effect of congestion pricing on public transportation was that car traffic decreased so much that buses ran faster than scheduled.”

From: Tfl’s Impacts monitoring Fifth Annual Report, July 2007, Sect 4.4 pp. 57-58:

“Figure 4.1 shows these counts over the last twenty years. The increase in passengers entering central London by bus over more recent years and in particular following the introduction of charging in 2003 is clear. Bus passenger numbers increased by 18 percent and 12 percent respectively during the first and second years after charging. Passenger numbers have since settled at around 116,000 in the weekday morning peak period.”

Most New Haven line passengers are traveling to or from stations other than the ones Amtrak serves.

Wikipedia has average daily ridership from 2018. It was

New Rochelle 6,112

Stamford 15,216

Bridgeport 4,490

New Haven 3,216

Or roughly one quarter of the riders. The other three quarters are using other stations. How are they supposed to get to those stations? Personal helicopter?

If Metro North is running six trains an hour to Penn Station they could have a one seat ride three times an hour. Stamford local every 20 minutes and a New Haven express every 20. Metro North, for the umpteenth time, it going to be running trains six times an hour. Which is more frequently than Amtrak will be. THEY CAN USE METRO NORTH TRAINS.

Neither Alon – nor anyone else – is suggesting running only Amtrak trains on the NH lines and cancelling service to all other stations. The other 75% of riders don’t need helicopters to those four stations, they can continue to ride MNRR trains from the other 43 stations along the NH line and its branches, just as they do today.

So why allow same price rides on Amtrak from MNRR stops?

Come back to planet Earth. It’s New England not the Tokaido. There aren’t enough people east/north of New Haven to run 8 trains an hour. Everybody in New England decides to take a round trip a year, by train, outside of New England, it’s 3 trainloads west/south of New Haven an hour. Which is optimistic because people in New England want to go other places and some of them will be on trains that go through Albany. Reality sucks doesn’t it? The other way reality sucks is that other people use the East River Tunnels and they aren’t going to let New Englanders run mostly empty trains through them.

If you want to run ten trains an hour over the Hell Gate Bridge, two of them can go alllllllllllll the way to Boston, three of them can run local to Stamford and terminate and three of them can run express between New Rochelle and Stamford and then local to New Haven.

The Tokaido Shinkansen runs up to 16 tph, plus there are multiple commuter services calling at the old Tokaido line’s 166 stations. So I am well aware that N. Eng. is not the Tokaido, which is why I suggested 6-8 tph as reasonable.

The fantasy is the idea that if you had to move 14M people you could do it evenly with 3 tph, 16 hours a day, every day of the year, as if the travel demand at 9pm on Sunday is exactly that at 7am on Thursday. In the reality you speak of you have to provide travel opportunities when people want to travel, not assume you can force them to take a train when it is convenient for your load optimization (isn’t there someone who comments on this blog who always talks about how you have to take the needs of pesky passengers into consideration???) So instead of 3tph all year round you would run 6-8tph at high demand times, 4-6tph middle of the day, and 1-2tph in the of hours.

Note that Amtrak was moving about 40% of the population of N. Eng. in 2022, when ridership still had not recovered to pre-2020 levels, and with no real HSR. Provide HSR and you can reach that whole-of-N. Eng.-in-a-year statistic quickly.

Two tph to Boston? That’s about what it sees today!

In Railfanlandia there are an infinite number of trains and staff. In the real world there aren’t and there will be times when the train is sold out. Nor is there an infinite amount of space in the East River Tunnels. There will be compromises. It’s unlikely they will be the ones imagined in Railfanlandia.

More staff can be hired if necessary. The cost of station staff or guard plus a driver for a train service really isn’t high.

On the least popular railway in England and Wales there is a single track line and a train every 3 hours serving 100k passengers a year. Doubling the train frequency and therefore doubling even that low passenger count is almost certainly sufficient to staff the extra train and to buy and maintain it.

If there’s enough people to run 8 trains an hour between Providence and Boston and enough people to run 8 trains an hour between New York and New Haven then there’s justification to run 8 trains an hour between New Haven and Providence. Even if those trains were 60% empty (in adironacker12800 world perhaps, but in reality they’re going to fill up) it’s still justifiable to have the express train be the same express train in both places, centralizing operations and reducing the number of potential conflicts.

It’s wild that you’re accusing your opponents of being “railfans” when you’re the one advocating for 40-odd different service patterns operated on 20-odd different types of equipment by seven to ten different agencies (depending on how you would like to count CTRail and the LIRR or whether you believe VRE counts here) who refuse to even talk to each other in a mess that sucks for pretty much everyone except the “brings their spreadsheets to the train station” crowd of people foaming at the mouth over having the “opportunity” to ride thirty year old rust buckets which are in the process of literally shaking themselves apart on the tracks.

Back here in reality, consolidation and simplification are good goals worth working towards, and it’s generally understood that you have to share your train with other people who might have other destinations than you do.

It costs money to run empty trains 113 miles or 182 kilometers between New Haven and Providence. If you want to get from Wilmington to Philadephia why do you care what kind of train the MBTA uses or whether or not MARC fares are competitive with WMATA ones?

It also means that when it’s time for the MBTA and MARC and everyone else to get new trains, they can either join the order for the American Standard Local EMU, the order for the American Standard Local unpowered coach car with non-electric locomotive for those who haven’t recovered the lost technology known as overhead wiring yet, or they can simply do without.

Because it turns out that you only have so much of any given resource, which means that you have to use your resources effectively whether it’s space or money or even time. That means standard trains that work everywhere, one for each category of operation, with full interoperability at every level. It means that the LIRR and Metro-North have to give up their petty feifdoms, and it means that the people currently benefiting from nonstop express trains out of Stamford will have to accept that their train makes a few express station stops along the way, and it means that the future categories of high speed rail in America do not include the return of the Acela Nonstop. You have your all-stop local trains, your some-stops “regional” intercity trains, and your fewest-stops express “HSR” intercity trains, and you get on the train at your closest station and either get off at your destination or get off at a transfer point somewhere and then walk across the platform if you need a different type of service.

I know. It sucks! Why can’t we just have every region have their own special trains with their own special liveries and uniforms? Why do I have to share my train with the locals? Can’t they just have their own train with its own special stopping pattern? I’m sorry. They can’t. We’re all just going to have to learn how to share.

I don’t know why the comment system decided to reorder my paragraph blocks. The first one should be the second one.

Why would NJTransit want a 15 year old design, when they are ordering new stuff in 2040? From the only vendor who makes the magical standard design. At monopoly prices.

The standard design is not magical nor is it from a hypothetical company who doesn’t exist. It’s whatever design won the bidding process when the RFP was put out. NJTransit will have the choice of joining the order or sitting it out, just the same as MARC and SEPTA and Metro-North and CTRail and the MBTA all do. The economics of scale and simplification mean its cheaper per unit and we can get more of them.

Or, we can have less trains, but more different types of trains, something which will make railfans happy at the expense of people who are just trying to get where they’re going in a reasonable time for a reasonable price and do not care about which flavor of off-the-shelf EMU got purchased from Europe for use on this and only this segment of railroad, nor do they care about what uniform the employees operating that train are wearing.

Almost all European trains are too small to use in North America. The gap between the train and the platform would be too wide and the height difference would be dangerous.

Orders from NJTransit or the MTA are some of the biggest, worldwide. They already have economies of scale.

The loading gauge is modular due to differences within Europe; Nordic trains are a hair wider than American ones, to the point that the Copenhagen S-Tog has six-abreast seating.

“Fordham’s reverse-peak service is a genuinely hard scheduling question, which we’re having to wrestle with as we’re proposing a (much) faster and smoother set of timetables for Northeast Corridor trains. “

???

Northeast Corridor trains use Penn Sta, the Hell Gate Bridge and New Haven RR tracks, not tracks from Grand Central Terminal over the New York Central RR’s NY and Harlem RR branch. The tracks never cross.

Whether Metro-North chooses to operate over its Harlem Division at headways of 1 per day or 10 per hour, should have negligible effect on Northeast Corridor trains between Washington, Philadelphia, New York and Boston.

You are correct, however, Metro North trains from the New Haven RR tracks do not use the Hell Gate Bridge but instead join the Harlem and Hudson line tracks. The Metro North trains on the New Haven line cannot be in the same place as Northeast Corridor trains on that line (obviously) but when they join the old NY Central tracks they also cannot be in the same place as Metro North trains on the Harlem and Hudson lines on the way to Grand Central. Thus the scheduling on all branches interact, directly or indirectly, with Amtrak’s schedule.

This is compounded by the facts (which Akon note) that some portions of these routes are four track but others only two (limiting overtakes) and that some junctions are flat, with tracks crossing, instead of flying, with tracks going over each other (which means a train from New Haven cannot use Mott Haven at the same time as one going to Yonkers even though they are heading in opposite directions, southbound vs northbound).

” some junctions are flat, with tracks crossing, instead of flying, with tracks going over each other (which means a train from New Haven cannot use Mott Haven at the same time as one going to Yonkers even though they are heading in opposite directions, southbound vs northbound).”

The middle tracks leading to/from Grand Central Terminal are bi-directional. I’ve seen many instances where the western tracks are reserved for two-way Hudson Branch trains and the eastern tracks are reserved for two-way New Haven and Harlem Division trains. This eliminates the Mott Haven switching bottleneck your described.

The only two track stretch is Amtrak from Sunnyside to Mt Vernon. The New Haven is 4 tracks all the way to New Haven. The Hudson is 3 tracks from Mott Haven; the Harlem is 4 tracks to Mt Vernon West and 3 tracks thereafter. It’s a flying junction after Woodlawn, where the New Haven splits from the Harlem.

It’s a flat junction at Mt Vernon, where Amtrak joins the New Haven. However, a single flat junction should not be a problem. You schedule trains along the same branch to use the junction in both directions at the same time. You then work the schedule from there.

The single flat junction at CP 216/Shell (not Mount Vernon) is a pretty big problem if there’s a frequent two-way schedule, rather than a frequent peak-direction schedule and some reverse-peak trains that fit whenever the peak-direction trains aren’t needed. It may be possible to orient the entire NEC schedule around it, but then there are other pain points, like track sharing on Boston-Providence and Washington-Baltimore and the flat Mott Haven Junction, that it makes everything more brittle.

And the Park Avenue Tunnel is currently three-and-one, but I expect this to change after Penn Station Access opens; total inbound traffic today is 46 tph, and PSA should remove a few of those, enough that a two-and-two setup should be stable, if the Hudson Line can be appropriately timetabled between the other trains.

Make Larchmont the Amtrak station. Plenty of space between there and New Rochelle to dig a tunnel. Eyballing it, the ROW is still six tracks wide – to accommodate the New York, Westchester and Boston. There is something to be said for making Rye the Amtrak Station. with dedicated ramps to the Cross Westchester Expressway in addition to the New England Thruway.

Mr. Levy,

I read your interview in Asterisk magazine, excellent.

I was struck, however, by a notable lack of mention of China. There is reference to Japan, Korea, India, Europe, Canada and even North Africa but not of the middle kingdom.

Is this because there is little of note in public transit there?

Or lack of data? Or other reasons?

The former seems unlikely given the enormous scale of public transit which China has completed just in the past 2 decades.

(Not Mr.)

Re China: it builds a lot of infrastructure because it’s a big middle-income country, but the way it builds, as far as we’ve been able to see, is not terribly different from the normal non-English-speaking first-world way. There are environmental reviews and alternatives analyses, there is competition between construction firms (which are owned by various levels of government but compete with one another as if they’re private firms), there is some use of consultants, the engineering standards are the same as in most developed countries. We’re likely going to do a case on Shanghai or another Chinese city soon, but from preliminary checks, it’s remarkable for how unremarkable it is, except in size.

Sorry for the mistaken attribution! And thank you for the follow up.

I certainly defer to your expertise on per-project comparables, but it still seems that the sheer scale *and* speed at which such construction has occurred, seems unusual. Is this a mistaken impression?

I had read that the Shanghai subway construction had executed more miles of underground railway than the entire world, for a longer period than said construction was undertaken. This seems like a lot given that Shanghai is only one city, albeit a large one, compared to the entire rest of the world.

Of course, the West has largely already built such public transit (outside of the US) but it still seems the scale and speed of what China has already accomplished is exceptional – but again – this is your field of expertise.

(Rescued from spamfilter.)

Shanghai absolutely has not built more subway route-length than the rest of the world. In our database, China is about even with the rest of the world combined – it’s not just Shanghai but a long tail of cities of various sizes.

The speed of construction in China mostly just tells me that it’s a fast-growing middle-income country. Japan was in that situation in the 1960s and 70s, when in 20 years Tokyo opened eight subway lines and two new commuter rail through-routes. Korea was in that situation a generation later; counting subway lines in Seoul is getting hard just because of all the commuter lines, but it has a lot and keeps building more. India is the next frontier of this – it’s slower than China because it has higher construction costs and a more anti-urban priority list, but the absolute amount of metro built there is pretty large, if sub-Chinese.

If anything, the ordinariness of Chinese investment is what’s so remarkable. The costs there are normal. The timelines are on the fast side, but they’re not cutting corners. They just combine the continental superstate scale of the US with the investment priorities of Europe or Japan, and that’s enough to build a high-speed rail network with 2 billion riders a year pre-corona.