Category: New York

Against Free Buses

Much of the public discussion over A Better Billion, our proposal to increase New York’s subway construction spending by $1 billion a year in lieu of Zohran Mamdani’s free bus plan, has taken it for granted that free buses are good, and it’s just a matter of arguing over spending priorities. Charlie Komanoff, who I deeply respect, proposes to combine subway construction with making the buses free. And yet, free buses remain a bad idea, regardless of funding, because of the effects of breaking fare integration between buses and the subway. If there is money for making the buses free, and it must go to fare reductions rather than to better service, then it should go to a broad reduction in fares, especially if it can also reduce the monthly rate in order to align with best practices.

Planning with fare integration

The current situation in New York is that buses and the subway have nearly perfect fare integration: the fares are the same, the fare-capped passes apply to both modes equally, and one free transfer (bus-bus or bus-subway) is allowed before the passenger hits the cap. Regular riders who would be taking multi-transfer trips are likely to be hitting the cap anyway so that restriction, while annoying, doesn’t change how passengers travel.

Under this regime of fare integration, buses and the subway are planned together. The bus network is not planned to connect every pair of points in the city, because the subway does that at 2.5 times the average speed. Instead, it’s designed to connect subway deserts to the subway, offer crosstown service where the subway only points radially toward the Manhattan core, and run service on streets with such high demand that buses get high ridership even with a nearby subway. The same kinds of riders use both modes.

The bus network has accumulated a lot of cruft in it over the generations and the redesigns are half-measures, but there’s very little duplication of service, if we define duplication as a bus that is adjacent to the subway and has middling or weak ridership. For example, the B25 runs on Fulton on top of the A/C, and the B37 and B63 run respectively on Third and Fifth Avenues a block away from the R, and all have middling traffic. In contrast, the Bx1/2 runs on Grand Concourse on top of the B/D but is one of the highest-ridership buses in the system. B25-type situations are rare, and most of the bus service that needs to be cut as part of system modernization is of a different form, for example routes in Williamsburg that function as circulators with maybe half the borough’s average ridership per service hour.

In this schema, the replacement of a bus with a train is an unalloyed good. The train is faster, more reliable, more comfortable. Owing to those factors, the train can also support higher ridership and thus frequency. If the train stops every 800 meters and averages 30 km/h and the bus stops every 400 and averages 15 (the current New York average is much lower; 15 is what is possible with stop consolidation from 200 to 400 meter interstations and other treatments), then it takes a 2.5 km trip for the replacement to be worth it on trip time even for a passenger living right on top of the deleted bus stop, and a 5 km one if we take into account the walk penalty – and that’s before we include all the bonuses for rail travel over bus travel, which fall under the rubric of rail bias.

The consequences of differentiated fares

All of the above planning goes out the window if there are large enough differences in fares that passengers of different classes or travel patterns take different modes. Commuter rail, not part of this system of fare integration in New York or anywhere else in the United States, is not planned in coordination with the subway or the buses, and fundamentally can’t be until the fares are fixed. Indeed, busy buses run in parallel to faster but more expensive and less frequent commuter lines in New York and other American cities, and when the buses happen to feed the stations, as at Jamaica Station on the LIRR or some Metro-North stations or at some Fairmount Line stations in Boston, interchange volumes are limited.

Commuter rail has many problems in addition to fares. But when the subway charges noticeably higher fares than the bus to the point that passengers sort by class, the same planning problems emerge. In Washington, the cheap, flat-fare bus and more expensive, distance-based fare on Metro led to two classes of users on two distinct classes of transit. When Metro finally extended to Anacostia with the opening of the Green Line in 1991, an attempt to redesign the buses to feed the station rather than competing with Metro by going all the way into Downtown Washington led to civil rights protests and lawsuits alleging that it was racist to force low-income black riders onto the more expensive product.

Whenever fares are heavily differentiated, any shift toward the higher-fare service involves such a fight. One of the factors behind the reluctance of the New York public transit advocacy sphere to come out in favor of commuter rail improvements is that those are white middle class-coded because that’s the profile of the LIRR and Metro-North ridership, caused by a combination of high fares and poor urban service. Fare integration is a fight as well, but it’s one fight per city region rather than one fight per rail project.

And more to the point, New York doesn’t even need to have that one fight at least as far as subway-bus integration is concerned, because the subways and buses are already fare integrated. What’s more, free bus supporters like Mamdani and Komanoff aren’t proposing this out of belief that fares should be disintegrated, but out of belief that it’s a stalking horse for free transit, a policy that Komanoff has backed for decades (he proposed to pair it with congestion pricing in the Bloomberg era) and that the Democratic Socialists of America have been in favor of. The latter is loosely inspired by 1960s movements and by reading many tourist-level descriptions in the American press of European cities with too weak a transit system for revenue to matter very much. Free buses in this schema are on the road to fully free transit, but then the argument for them involves the very small share of transit revenue contributed by buses rather than the subway. In effect, an attempt to make the system free led to a proposal that could only ever result in disintegrated fares, even though that is not the intent.

But good intent does not make for a good program. That free buses are not proposed with the intent of breaking fare integration is irrelevant; if the program is implemented, it will break fare integration, and turn every bus redesign into a new political fight and even create demand for buses that have no reason to exist except to parallel subway lines. The program should be rejected, not just because it costs money that can be better spent on other things, but because it is in itself bad.

A Better Billion and the Cost Model versus the 125th Street Subway Extension

We released a new report called A Better Billion. It was covered rather positively in the New York Times yesterday, with quotes from other transit advocacy groups. The idea for our report is that Zohran Mamdani promised free buses in his successful primary campaign, and promised free and fast buses in his successful general election campaign for mayor, so let’s take the $1 billion a year this could cost in forgone revenue and see how to spend it on subway expansion instead.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the article and on social media about the idea of free buses, but instead I want to talk about our proposal’s cost model, in the context of a rather incompetent plan the MTA released recently for a subway extension of Second Avenue Subway under 125th Street, at twice the per-km cost of Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, and twice the cost we project. Our model is not based on non-Anglo costs, but rather on real New York costs, modified to incorporate the one major cost saving coming from our previous reports, namely, shrinking station size. Based on everything combined, we came up with the following medium cost model:

| Item | Cost (2025 prices) |

| Tunnel (1 km) | $530 million |

| Tunnel, underwater (1 km) | $1,050 million |

| El or trench (1 km) | $260 million |

| Station, cut-and-cover | $510 million |

| Station, mined | $770 million |

| Station, el or trench | $240 million |

These costs include apportioned soft costs and not just hard costs. Altogether, an extension of Second Avenue Subway from Park Avenue to Broadway, a distance of 2 km with three mined stations at the intersections with the north-south subway lines, should cost $3.4 billion. This is not much less per kilometer than Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, which can be explained by the denser stop spacing and the need for mined stations at the undercrossings. If everything else were done in the right way rather than the American way, the low cost model would apply and costs would be reduced further by a factor of about 3, but the per-km cost would remain one of the highest outside the Anglosphere for those geotechnical reasons.

But the MTA and its consultants, in this case AECOM, project $7.7 billion, not $3.4 billion. Why?

Worse project delivery

We’ve assumed the existing project delivery systems the MTA is familiar with. However, what doesn’t move forward moves backward, and the procurement strategy at the MTA is moving backward rapidly, for which the primary culprit is Janno Lieber, first in his role at MTA Capital Construction (now Construction and Development), and then in his role as MTA head, pushing alternative delivery methods, especially design-build and increasingly progressive design-build (unfortunately legalized in New York last year). Such methods add to the procurement costs and especially to the soft costs. Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 had an overall soft cost multiplier of about 1.5: the total cost including soft costs was 1.5 times the hard costs (Italy: 1.2-1.25 times). This proposal, in contrast, has a multiplier of 1.75: the hard costs are estimated at $4.4 billion, and the total costs are 75% higher, technically including rolling stock except rolling stock at current New York costs is $80 million.

Contingency

The soft costs include a federally mandated 40% contingency. The FTA mandates excessive contingencies – the norm in low-cost countries is 10-20%, and anything more than that is just wasted. The contingency figure varies by phase of design and decreases as it advances, but in the earliest phase it is 40%, and it’s in that phase that budgeting is done. However, 40% is only required over hard costs based on standardized cost categories (SCCs), and not over past ex post costs that incorporated contingency themselves. In effect, the estimation method the MTA and AECOM prefer bakes in a 40% overrun at each stage, letting project delivery get worse over time as the globalized system of procurement takes deeper roots in New York.

Overdesign and overbuilding

Based on our recommendations, the MTA shrank the station overages in Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. Phase 1 had station digs 100% longer than the platforms, based on standards that were both extravagant to the taxpayer and spartan to the end user – the extra space is not usable by passengers but instead for unnecessary break rooms, separated by department. By Phase 2, this was reduced to a 50% overage, and we hoped that proactive design around best practices would reduce this further.

Unfortunately, the overages are still substantial, 50% at St. Nicholas and 25% at the other two stations (Italy, Sweden, France, Germany, China: 3-20%). Moreover, the stations still have full-length mezzanines. This a longstanding New York tradition, going back to the 1930s with the opening of the IND lines starting with the A on Eighth Avenue in 1933. And like all other New York subway building traditions that conflict with how things are done in more advanced, non-English speaking countries, it belongs in the ashbin of history. Mined stations’ costs are sensitive to dig volume, and there is little need for such additional circulation space, for passenger comfort or fire safety. Mezzanines are essentially free if the stations are built cut-and-cover, in which case they are used for back-of-the-house space in advanced countries, but not if the stations are mined, in which case the best place for break rooms is under stairs and escalators.

Moreover, as we will explain soon at the Effective Transit Alliance, mined stations and bored tunnel require a minimum spacing from the street and from other tunnels – but the proposal includes much more space than necessary, forcing the stations to be deeper, more expensive, and less convenient as it takes a full five minutes to transfer between platforms or to get from the platform to the street. It’s possible to ge even shallower with shoring techniques used in China to reduce tunnel and station depth in complex urban undergrounds.

Proactive and reactive cost control

When the MTA announced cost savings and station size shrinkage in Phase 2, we were excited. But on hindsight, costs in effect fell from $7 billion to $7 billion. The savings were entirely reactive, designed to limit further cost overruns, and are not proactively incorporated into further projects.

No doubt, if a $7.7 billion project is approved against any honest benefit-cost analysis (which is not required in American law), then shrinkage in station footprint and reduction in mezzanine length will be found to be saving money in 2032, and the successor of Lieber, hired from the same pipeline of people whose takes on other countries are “I had a kid who did a semester abroad in Stockholm,” will be proud of reducing costs from $7.7 billion to $7.7 billion.

The path forward must instead incorporate cost savings proactively. There’s a way of building subway stations cost-effectively, and instead of quarter-measures, the MTA should adopt it; we have blueprints from a growing selection of examples, all in places that have avoided the destruction of subway building capacity infecting the entire English-dominant world in the last 25 years. The MTA can even hire people with direct transport official-to-transport official communication with peers at other agencies (for example, through COMET) and with the language skills to read documents produced in lower-cost countries, instead of people whose best skill is giving interviews to softball interviewers and talking about sports.

Fare Practices

Here’s a table of urban public transport fares for various cities, covering the United States, Canada, parts of Europe, Turkey, and Japan. Included are single fares, multi-ride discounts, day passes, weeklies, and monthlies, with the last three shown with their ratios to single fares. As far as possible we’ve tried doing fares as of 2026, but it’s possible a few numbers are not updated and depict 2025 figures.

The thing to note is that in Continental Europe, there are steeply discounted monthlies – only two cities in the table charge for a monthly more than for 30 single-trips (Paris at 35.5, Bari at 35). Most Italian cities cluster around 20, and Barcelona, Lisbon, and especially Porto are even lower. Berlin used to have a multiplier of 32 before the 9€ monthly and the subsequent Deutschlandticket but the current multiplier is 15.75 within the city. Stockholm has a monthly multiplier of 24.7. Prague’s multiplier is 12.

Japanese monthly fares are strange by Western standards, in the sense that they are station-to-station, with subsegments allowed but no trips outside the segment; subject to this constraint the multiplier is 30-40, with small additional discount for buying 3-6 months in advance, but the unrestricted monthly fare is very high. London and Istanbul functionally do not have monthlies, in the sense that the multiplier is so high (78.5 Istanbul-wide, and it’s not truly unlimited but is capped at 180 trips/month) that except for trips within Central London it might as well not exist.

American and Canadian monthly fares are usually higher than in Continental Western Europe, with multipliers in the 30s. New York’s multiplier was especially high, about 46, and the MTA has just abolished the monthly fare entirely and phased out the MetroCard (as of the new year, starting in two hours), making people use the weekly cap with OMNY instead, which has a multiplier of 11.7 and, over a 30-day month, forces a monthly multiplier of 50. Toronto has a very high monthly multiplier as well, 46.6. This is bad practice: a high monthly discount functions as a technologically simple off-peak discount (indeed, London pairs its stingy monthly discount with a substantial off-peak discount), and OMNY itself is buggy to the point that fare inspectors on the buses can’t tell if someone has actually paid except by looking at debit card statements, which do not show one as having paid if one has a valid transfer or has reached the weekly cap (and not tapping in this case is still illegal fare dodging in New York law).

The practice of the cap, increasingly popular in the US under London influence, is rare as well. London’s fare cap originates in its complex zone system: the Underground has nine zones with zone 1 only covering Central London so that passengers taking multiple trips per day can expect to take trips across different zones that they may not be familiar with; there isn’t fare integration, but rather there’s a special surcharge on some commuter train trips and a discount on buses; peak and off-peak fares are different. Thus, the calculation for the passenger of whether to buy tickets one at a time or get a pass is difficult, so Oyster does this calculation automatically to give the most advantageous fare. In a Continental city where fares are either flat regionwide or have zones with limited granularity (often the entire metro is in the innermost zone) and monthly discounts are steep, the calculation is simple: an even semi-regular rider should always get a monthly.

American and Canadian cities typically have flat fares or a simple zone system, good fare integration between buses and the subway or light rail, and commuter rail that’s functionally unusable for urban trips rather than resembling the subway with a $2 surcharge. The use case of London does not apply to such cities. New York should not have a fare cap, but a heavily surcharged single trip, perhaps $5, and an attractive flat monthly fare, perhaps $130. This system ensures passengers are incentivized to pay and there is little opportunistic fare dodging as the user has already prepaid for the entire month, so it pairs well with proof-of-payment fare collection, common in many of the European examples (though metro systems outside Germany and its immediate vicinity do have faregates).

The overall level of the fare is determined by the willingness of the government at various levels to subsidize public transport; the table can be used to compare these at PPP rates as well. However, the distribution of fares across different products and distances is not a matter of subsidy but a matter of good and bad industry practices, and the best practice for simple fare collection is to offer a prepaid monthly at a heavy discount compared with the single ride.

Quick Note: The Importance of Penn Station Access West to Through-Running

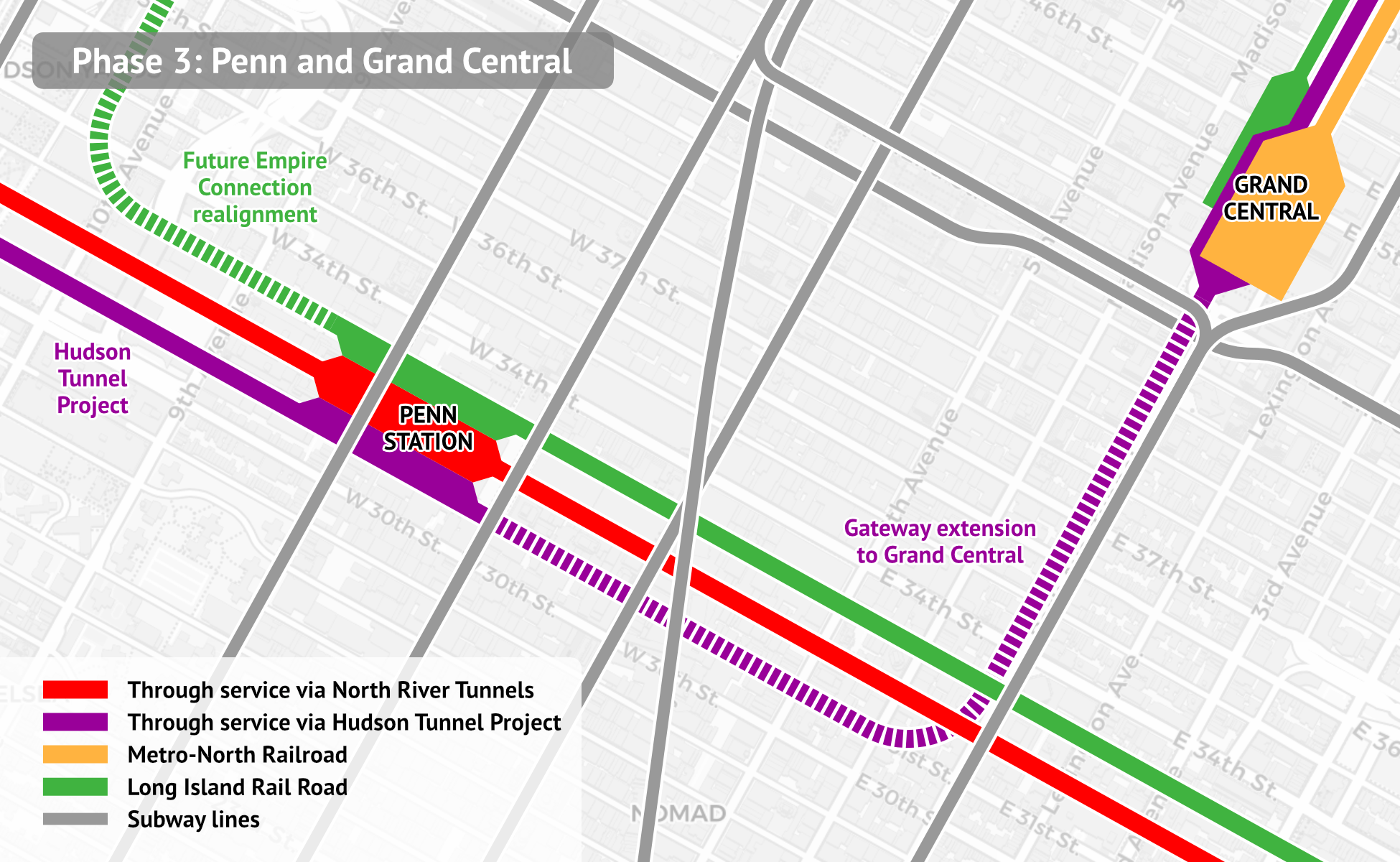

A video by the Joint Transit Association talks at length about through-running in New York – which lines are easier and which are harder, what some of the tradeoffs are, what sequencing works best with ongoing infrastructure plans starting with the Gateway tunnel. It’s a good video and I recommend watching – and not just because it gets a lot of its ideas from ETA reports but also because of its own analysis and own points (about, for example, Mott Haven Junction) – but it has one miss that I’d like to highlight: it neglects Penn Station Access West, the proposal to connect the Hudson Line to Penn Station via the Empire Connection.

The issue is that without the realignment, too many trains would be going into Grand Central – all preexisting Metro-North service minus trains diverted to Penn Station Access. We expect all this through-running infrastructure to add to peak demand substantially. Today it fills about 50 peak trains per hour, which a four-track trunk line would struggle with (Metro-North runs trains three-and-one at the peak). Even with diversion of 6-10 trains to Penn Station Access, the extra demand would saturate the line. Penn Station Access West is important in reducing this capacity crunch.

The realignment is both important and cheap. The Empire Connection exists and the tunnel has room for two tracks; it needs a short realignment to reach the right part of Penn Station – the high-numbered northern tracks as in the image, where today there is a single-track link from the Connection proper to the low-numbered tracks – but that realignment is much cheaper than a full through-tunnel such as between Penn Station and Grand Central or the various lines to Lower Manhattan mooted for longer-term plans.

The total capacity produced should be every train that doesn’t have to go to Grand Central. It’s hard to exactly say what the split should be – there should be a minimum of a train every 10 minutes to each destination, if only to serve the inner stations that are (or would be infill) on the lower Hudson Line or the Empire Connection before the two routes meet at Spuyten Duyvil. Beyond that it’s a matter of measuring demand and seeing what the limit of timed connections are; ideally there should be 12 peak trains per hour on Penn Station Access West and only 6 on the preexisting route, up from 14 total on the Hudson Line today due to service improvements brought by through-running and related upgrades. This is necessary to create the capacity to run more service on the other lines – today the Harlem Line peaks at 16 trains per hour and the New Haven Line at 20, but these upgrades would create a lot more demand and my assumption in sketching through-running tunnels is that the Harlem Line would need 24 and the New Haven Line would need 18 to Grand Central and 6 on Penn Station Access.

New York Isn’t Special

A week ago, we published a short note on driver-only metro trains, known in New York as one-person train operation or OPTO. New York is nearly unique globally in running metro trains with both a driver and a conductor, and from time to time reformers have suggested switching to OPTO, so far only succeeding in edge cases such as a few short off-peak trains. A bill passed the state legislature banning OPTO nearly unanimously, but the governor has so far neither signed nor vetoed it. The New York Times covered our report rather favorably, and the usual suspects, in this case union leadership, are pissed. Transportation Workers Union head John Samuelsen made the usual argument, but highlighted how special New York is.

“Academics think working people are stupid,” [Samuelsen] said. “They can make data lie for them. They conducted a study of subway systems worldwide. But there’s no subway system in the world like the NYC subway system.”

Our report was short and didn’t go into all the ways New York isn’t special, so let me elaborate here:

- On pre-corona numbers, New York’s urban rail network ranked 12th in the world in ridership, and that’s with a lot of London commuter rail ridership excluded, including which would likely put London ahead and New York 13th.

- New York was among the first cities in the world to open its subway – but London, Budapest, Chicago (dating from the electrification and opening of the Loop in 1897), Boston, Paris, and Berlin all opened earlier.

- New York has some tight curves on its tracks, but the minimum curve radius on Paris Métro Line 1, 40 meters, is comparable to the New York City Subway’s.

- The trains on the New York City Subway are atypically long for a metro system, at 151 meters on most of the A division and 183 on most of the B division, but trains on some metro systems are even longer (Tokyo has some 200 m trains, Shanghai 180 m trains) and so are trains on commuter rail systems like the RER (204 m on the B, 220 m on the A), Munich S-Bahn (201 m), and Elizabeth line (205 m, extendable to 240).

- New York has crowded trains at rush hour, with pre-Second Avenue Subway trains peaking at 4 standees per square meter, but London peaks at 5/m^2 and trains in Tokyo and the bigger Chinese cities at more than that. Overall ridership, irrespective of crowding, peaked around 30,000 passengers per direction per hour on the 4 and 5 trains in New York, compared with 55,000 on the RER A.

New York is not special, not in 2025, when it’s one of many megacities with large subway systems. It’s just solipsistic, run by managers and labor leaders who are used to denigrating cities that are superior to New York in every way they run their metro systems as mere villages unworthy of their attention. Both groups are overpaid: management is hired from pipelines that expect master-of-the-universe pay and think Sweden is a lower-wage society, and labor faces such hurdles with the seniority system that new hires get bad shifts and to get enough workers New York City Transit has had to pay $85,000 at start, compared with, in PPP terms, around $63,000 in Munich after recent negotiations. The incentive in New York should be to automate aggressively, and look for ways to increase worker churn and not to turn people who earn 2050s wages for 1950s productivity be a veto point to anything.

Why is Janno Lieber Constantly Blaming Other People for Problems?

The Editorial Board posted an interview with MTA head Janno Lieber about sundry public transit-related issues. His answers for the most part aren’t bad until he gets to construction costs (and misgenders me), but alongside other recent news about Penn Station Access, they reveal a pattern: Lieber loves blaming other people for problems – nothing is ever the MTA’s fault, everything is someone else’s fault. Nor is he curious about acquiring expertise, to the point that everything is defensive, and everything is about reducing transparency and accountability. Someone like this should not be heading a public transit agency.

Penn Station Access

Penn Station Access, the project to run Metro-North trains from New Rochelle to Penn Station via the Hell Gate Line currently used only by Amtrak, was announced earlier this month to be delayed by a further two years, from 2028 to 2030. The MTA blames Amtrak, which owns most of the line, for not giving it enough work windows.

And, excuse me, but this is bullshit for two separate reasons. The first is that the opening date was said to be 2027 until this year and then 2028. Other people made plans based on MTA announcements; quite a lot of behind-the-scenes advocacy was designed specifically around this date. The state was among those other people: in March, it decided to buy new battery-powered locomotives, each costing $23.45 million (about the same as an eight-car EMU set), on the grounds that it would take too long to acquire new EMUs that were compatible with the different electrification systems used on the line. It’s not at all hard to get new EMUs compatible with both the 12 kV 60 Hz electrification used on most of the line and the 12 kV 25 Hz system used in the last few km into Penn Station based on current New York lead times if the project opens in 2030. But the state made a decision based on the assumption it would need this well before 2030.

In other words, the MTA only discovered that there would be Amtrak-induced delays around two and a half years before planned opening for a project that had been going on for three years and approved for six – and now it’s blaming it on Amtrak instead of on its own poor project management and lack of transparency.

The second reason it’s bullshit is that the relationship between Amtrak and the MTA is mutually abusive. Amtrak is not giving the MTA enough work windows on the Hell Gate Line; the MTA is slowing down Amtrak trains on the New Haven Line between New Rochelle and New Haven, where it owns the tracks, the only part of the Northeast Corridor that is both owned and dispatched by a commuter railroad and not Amtrak (in Massachusetts the MBTA owns the tracks but Amtrak controls dispatching). The maximum allowed cant deficiency on Metro-North territory is based on unmodernized Metro-North values and not based on the modern values that Amtrak rolling stock has been tested for, and there is no attempt to keep Amtrak and Metro-North trains separate east of Stamford, where there are four tracks and light enough traffic that it’s possible, that the top speeds can have a mismatch.

In other words, the MTA complains about being abused by Amtrak, and is likely correct, but refuses to stop abusing Amtrak where it does have control. It could manage this relationship better, but it doesn’t and Lieber isn’t competent enough to know how to do it better.

Fares

The conversation in The Editorial Board heavily features talking about fares, in context of fare evasion and mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani’s proposal for free buses. Lieber is suggesting that instead of free buses, buses can have all-door boarding without free fares, unlocking the speed benefits without forgoing the revenue. He’s right and I want to sympathize with his critique of free buses. But it was Lieber who scuttled plans by Andy Byford to install back-door OMNY card readers and enable all-door boarding without free fares. He calls for all-door boarding as an alternative to free buses now, but when all-door boarding was available as an internally developed plan, he killed it.

He speaks about Europe this and Europe that in the interview, but he’s too ignorant and incurious to understand how things go here and how we make all-door boarding work with proof-of-payment. And the best way to see that is his abominable line, “had a kid who did a semester abroad in Stockholm, and you see them all over in Europe.” That’s his only reference – his kid did a semester abroad. He didn’t ring up any transit agency to ask how to do it. It’s all superficial, almost tourist-level understanding of better-run systems.

This is especially bad in context of what he says about construction costs at the end. He says,

I don’t accept the Alon Levy theory, which, you know, you’re articulating — that somehow, if we just had like this massive in-house force, we would be building everything way, way cheaper. That’s like, hiring— you cannot compete with private-sector engineering. And we don’t have one project after another, like he loves, like Madrid, which built all these subways in a row.

Setting aside the fact that calling me “he” in New York, a city with better access to gender-neutral bathrooms than my own, is obnoxious, we didn’t do a report on Madrid, but did do one on Stockholm. He’s aware of the report (and of the points it makes about ridership per station, the excuse he uses farther down the line for bigger stations). And he still reduces Stockholm to where his kid did a one-semester study abroad to give a little anecdote on fare evasion, which boils down to Americans being so detached from internal national discourses in Europe (except maybe the UK) that they don’t know that we’ve had to deal with the same questions they did, we just have public agencies run by competent people who sometimes make the right decisions and not by people like Janno Lieber.

Reverse-Branching on Commuter Rail

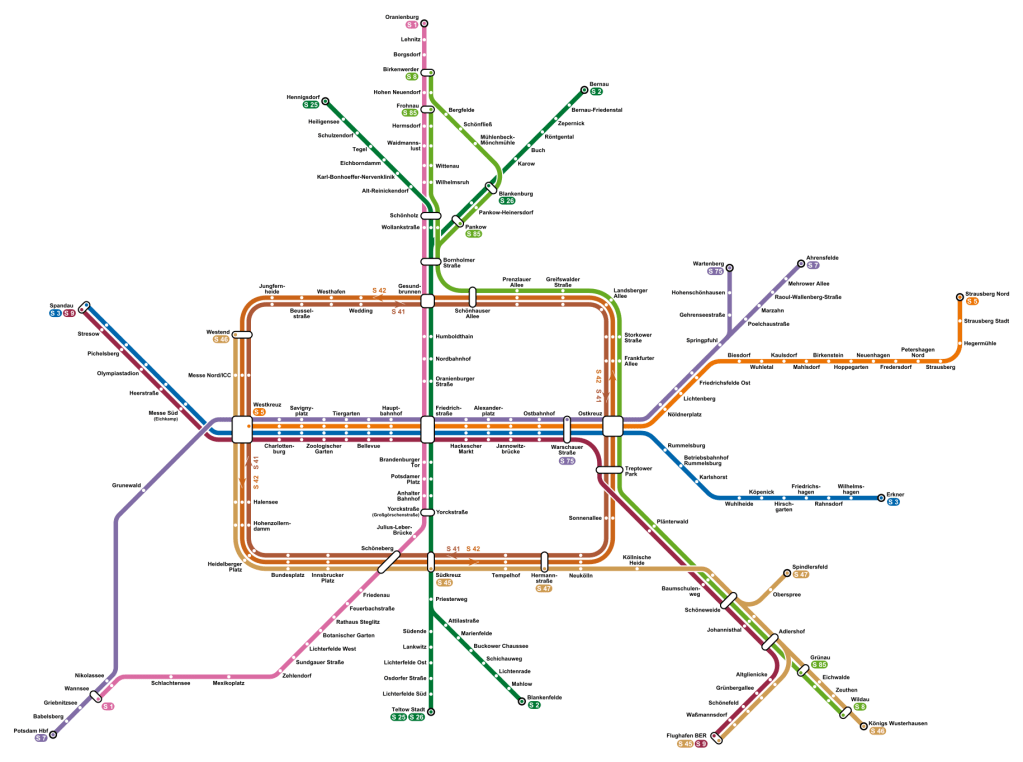

Koji asked me 3.5 days ago about why my proposal for New York commuter rail through-tunnels has so much reverse-branching. I promised I’d post in some more detail, because in truth, reverse-branching is practically inevitable on every commuter rail system with multiple trunk lines, even systems that are rather metro-like like the RER or the S-Bahns here and in Hamburg.

This doesn’t mean that reverse-branches, in this case the split from the Görlitzer Bahn trunk toward the Stadtbahn via S9 and the Ring in two different directions via S45/46/47 and S8/85, are good. It would be better if Berlin invested in turning this trunk into a single trunk into city center, provided it were ready to build a third through-city line (in fact, it is, but this project, S21, essentially twins the North-South Tunnel). However, given the infrastructure or small changes to it, the current situation is unavoidable.

Moreover, the current situation is not the end of the world. The reasons such reverse-branches are not good for the health of the system are as follows:

- They often end up creating more frequency outside city center than toward it.

- If there is too much interlining, then delays on one branch cascade to the others, making the system more fragile.

- If there is too much interlining, then it’s harder to write timetables that satisfy every constraint of a merge point, even before we take delays into account.

All of these issues are more pressing on a metro system than on a commuter rail system. The extent of branching on commuter rail is such that running each line as a separate system is unrealistic; tight timetabling is required no matter what, and in that case, the lines could reverse-branch if there’s no alternative without much loss of capacity. The S-Bahn here is notoriously unreliable, but that’s the case even without cascading delays on reverse-branches – the system just assumes more weekend shutdowns, less reliable systems (28,000 annual elevator outages compared with 1,800 on the similar-size U-Bahn), and worse maintenance practices.

So, on the one hand, the loss from reverse-branching is reduced. On the other hand, it’s harder to avoid reverse-branching on commuter rail. The reason is that, unlike a metro (including a suburban metro), the point of the system is to use old commuter lines and connect them to form a usable urban and suburban service. Because the system relies on old lines more, it’s less likely that they’re at the right places for good connections. In the case of Berlin, it’s that there’s an east-west imbalance that forces some east-center-east lines via S8, which was reinforced by the context of the Cold War and the Wall.

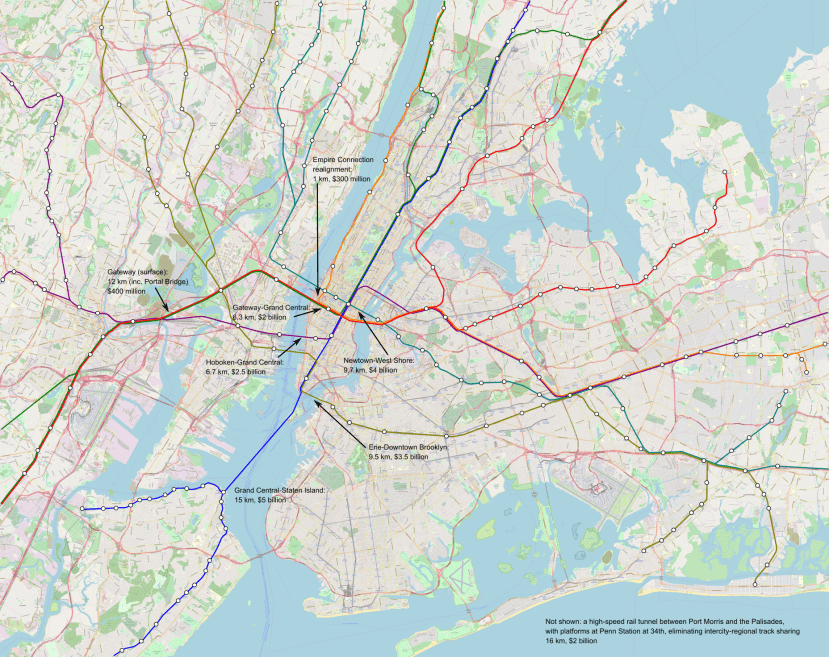

In the case of New York, consider this map:

The issue is that too much traffic wants to use the Northeast Corridor lines in both New Jersey and Connecticut. Therefore, it’s not possible to segregate everything, with lines using the preexisting North River Tunnels and the new Gateway tunnels having to share tracks. It’s not optimal, but it’s what’s possible.

Transit-Oriented Development and Rail Capacity

Hayden Clarkin, inspired by the ongoing YIMBYTown conference in New Haven, asks me about rail capacity on transit-oriented development, in a way that reminds me of Donald Shoup’s critique of trip generation tables from the 2000s, before he became an urbanist superstar. The prompt was,

Is it possible to measure or estimate the train capacity of a transit line? Ie: How do I find the capacity of the New Haven line based on daily train trips, etc? Trying to see how much housing can be built on existing rail lines without the need for adding more trains

To be clear, Hayden was not talking about the capacity of the line but about that of trains. So adding peak service beyond what exists and is programmed (with projects like Penn Station Access) is not part of the prompt. The answer is that,

- There isn’t really a single number (this is a trip generation question).

- Moreover, under the assumption of status quo service on commuter rail, development near stations would not be transit-oriented.

Trip generation refers to the formula connecting the expected car trips generated by new development. It, and its sibling parking generation, is used in transportation planning and zoning throughout the United States, to limit development based on what existing and planned highway capacity can carry. Shoup’s paper explains how the trip and parking generation formulas are fictional, fitting a linear curve between the size of new development and the induced number of car trips and parked cars out of extremely low correlations, sometimes with an R^2 of less than 0.1, in one case with a negative correlation between trip generation and development size.

I encourage urbanists and transportation advocates and analysts to read Shoup’s original paper. It’s this insight that led him to examine parking requirements in zoning codes more carefully, leading to his book The High Cost of Free Parking and then many years of advocacy for looser parking requirements.

I bring all of this up because Hayden is essentially asking a trip generation question but on trains, and the answer there cannot be any more definitive than for cars. It’s not really possible to control what proportion of residents of new housing in a suburb near a New York commuter rail stop will be taking the train. Under current commuter rail service, we should expect the overwhelming majority of new residents who work in Manhattan to take the train, and the overwhelming majority of new residents who work anywhere else to drive (essentially the only exception is short trips on commuter rail, for example people taking the train from suburbs past Stamford to Stamford; those are free from the point of view of train capacity). This is comparable mode choice to that in the trip and parking generation tables, driven by an assumption of no alternative to driving, which is correct in nearly all of the United States. However, figuring out the proportion of new residents who would be commuting to Manhattan and thus taking the train is a hard exercise, for all of the following reasons:

- The great majority of suburbanites do not work in the city. For example, in the Western Connecticut and Greater Bridgeport Planning Regions, more or less coterminous with Fairfield County, 59.5% of residents work within one of these two regions, and only 7.4% work in Manhattan as of 2022 (and far fewer work in the Outer Boroughs – the highest number, in Queens, is 0.7%). This means that every new housing unit in the suburbs, even if it is guaranteed the occupant works in Manhattan, generates demand for more destinations within the suburb, such as retail and schools.

- The decision of a city commuter to move to the suburbs is not driven by high city housing prices. The suburbs of New York are collectively more expensive to live in than the city, and usually the ones with good commuter rail service are more expensive than other suburbs. Rather, the decision is driven by preference for the suburbs. This means that it’s hard to control where the occupant of new suburban housing will work purely through TOD design characteristics such as proximity to the station, streets with sidewalks, or multifamily housing.

- Among public transportation users, what time of day they go to work isn’t controllable. Most likely they’d commute at rush hour, because commuter rail is marginally usable off-peak, but it’s not guaranteed, and just figuring the proportion of new users who’d be working in Manhattan at rush hour is another complication.

All of the above factors also conspire to ensure that, under the status quo commuter rail service assumption, TOD in the suburbs is impossible except perhaps ones adjacent to the city. In a suburb like Westport, everyone is rich enough to afford one car per adult, and adding more housing near the station won’t lower prices by enough to change that. The quality of service for any trip other than a rush hour trip to Manhattan ranges from low to unusable, and so the new residents would be driving everywhere except their Manhattan job, even if they got housing in a multifamily building within walking distance of the train station.

This is a frustrating answer, so perhaps it’s better to ask what could be modified to ensure that TOD in the suburbs of New York became possible. For this, I believe two changes are required:

- Improvements in commuter rail scheduling to appeal to the growing majority of off-peak commuters as well as to non-commute trips. I’ve written about this repeatedly as part of ETA but also the high-speed rail project for the Transit Costs Project.

- Town center development near the train station to colocate local service functions there, including retail, a doctor’s office and similar services, a library, and a school, with the residential TOD located behind these functions.

The point of commercial and local service TOD is to concentrate destinations near the train station. This permits trip chaining by transit, where today it is only viable by car in those suburbs. This also encourages running more connecting bus service to the train station, initially on the strength of low-income retail workers who can’t afford a car, but then as bus-rail connections improve also for bus-rail commuters. The average income of a bus rider would remain well below that of a driver, but better service with timed connections to the train would mean the ridership would comprise a broader section of the working class rather than just the poor. Similarly, people who don’t drive on ideological or personal disability grounds could live in a certain degree of comfort in the residential TOD and walk, and this would improve service quality so that others who can drive but sometimes choose not to could live a similar lifestyle.

But even in this scenario of stronger TOD, it’s not really possible to control train capacity through zoning. We should expect this scenario to lead to much higher ridership without straining capacity, since capacity is determined by the peak and the above outline leads to a community with much higher off-peak rail usage for work and non-work trips, with a much lower share of its ridership occurring at rush hour (New York commuter rail is 67-69%, the SNCF part of the RER and Transilien are about 46%, due to frequency and TOD quality). But we still have no good way of controlling the modal choice, which is driven by personal decisions depending on local conditions of the suburb, and by office growth in the city versus in the suburbs.

Timetable Padding Practices

Two weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal wrote this piece about our Northeast Corridor report. Much of it was based on a series of interviews William Boston did with me, explaining what the main needs on the corridor are. One element stands out since the MTA responded to what I was saying about schedule padding – I talk about how Amtrak and Metro-North both pad the timetables on the Northeast Corridor by about 25%, turning a technical travel time of an hour into 1:15 (best practices are 7%), and in response, the MTA said that they pad their schedules 10% and not 7%. This is an incorrect understanding of timetable padding, which speaks poorly to the competence of the schedule planners and managers at Metro-North.

The article says,

Aaron Donovan, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, says the extra time built into Metro-North schedules generally averages 10%, depending on destination and length of trips, and takes into account routine track maintenance and capital work that can increase runtime. Metro-North continually reviews models, signal timing, equipment, and other elements of operation to improve travel times and reliability for customers, he says.

This is, to be clear, incorrect. Metro-North routinely recovers longer delays than 10%; delay recovery on the New Haven Line can reach well over 20 minutes out of a nominally two-hour trip, around 25% of the unpadded trip length. The reason this is incorrect isn’t that Donovan is dishonest or incompetent (he is neither of these two things), but almost certainly that the planners he spoke with genuinely believe they only pad 10%, because they, like all American railroaders, do not know how modern rail scheduling is done.

Modern rail scheduling practices in the higher-reliability parts of Europe and Japan start with the technical timetable, based on the actual speed zones and trains’ performance characteristics. This includes temporary speed restrictions. The ideal maintenance regime does not use them, instead relying on regular nighttime maintenance windows during which all tracks are out of service. However, temporary restrictions may exist if a line is taken out of service and trains are rerouted along a slower route, which is regrettably common in Germany. Modern signaling systems are capable of incorporating temporary speed restrictions – this is in fact a core requirement for American positive train control (PTC), since American maintenance practices rely on extensive temporary restrictions for work zones and one-off slowdowns. If the signal system knows the exact speed zones on each section of track, then so can the schedule planners.

The schedule contingency figure is computed relative to the best technical schedule. It is not computed relative to any assumption of additional delays due to dispatch holds or train congestion. The 7% figure used in Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands takes care of the high levels of congestion on key urban segments.

The core urban networks in these countries stack favorably with Metro-North in track utilization. The Hirschengraben Tunnel in Zurich runs 18 S-Bahn trains per hour in each direction most of the day and 20 at rush hour with some extra S20 runs, and the Weinberg Tunnel runs 8 S-Bahn trains per hour and if I understand the network graphic right 7.5 additional intercities per hour. I urge people to go look at the graphic and try tracking down the lines just to see how extensively branched and reverse-branched they are; this is not a simple network, and delays would propagate. The reason the Swiss rail network is so punctual is that, unlike American rail planning, it integrates infrastructure and timetable development. This means many things, but what is relevant here is that it analyzes where delays originate and how they propagate, and focuses investments on these sections, grade-separating problematic flat junctions if possible and adding pocket tracks if not.

Were I to only take timetable padding into account relative to an already more tolerant schedule incorporating congestion and signaling limitations, I would cite much lower figures for timetable padding. Switzerland speaks of a uniform 7% pad, but in Sweden the figures include two components, a percentage (taking care of, among other things, suboptimal driver behavior) and a fixed number of minutes per 100 km, which at current intercity speeds resolve to 7% as in Switzerland. But relative to the technical trip time, the pad factors based on both observed timetable recovery and actual calculations on current speed zones are in the 20-30% range, and not 10%.

Of course, at no point do I suggest that Metro-North and Amtrak could achieve 7% right now, through just writing more aggressive timetables. To achieve Swiss, Dutch, and Swedish results, they would need Swiss, Dutch, or Swedish planning quality, which is sorely lacking at both railroads. They would need to write better timetables – not just more aggressive ones but also simpler ones: Metro-North’s 13 different stopping patterns on New Haven Line trains out of 16 main line peak trains per hour should be consolidated to 2. This is key to the plan – the only way Northern Europe makes anything work is with fairly rigid clockface timetables, so that one hour or half-hour is repeated all day, and conflicts can be localized to be at the same place every time.

Then they would need to invest based on reliability. Right now, the investment plans do not incorporate the timetable, and one generally forward-thinking planner found it odd that the NEC report included both high-level infrastructure proposals and proposed timetables to the minute. In the United States, that’s not the normal practice – high-level plans only discuss high-level issues, and scheduling is considered a low-level issue to be done only after the concrete is completed. In Northern European countries with competently-run railways and also in Germany, the integration of the timetable and infrastructure is so complete that draft network graphics indicating complete timetables of every train to the minute are included in the proposal phase, before funding is committed. In Switzerland, such a timetable is available before the associated infrastructure investments go to referendum.

Under current American planning, the priorities for Metro-North are in situ bridge replacements in Connecticut because their maintenance costs are high even by Metro-North’s already very expensive standards. But under good planning, the priority must be grade-separating Shell Interlocking (CP 216) just south of New Rochelle, currently a flat junction between trains bound for Grand Central and ones bound for Penn Station. The flat junctions to the branches in Connecticut need to be evaluated for grade-separation as well, and I believe the innermost, to the New Canaan Branch, needs to be grade-separated due to its high traffic while the ones to the two farther out branches can be kept flat.

None of this is free, but all of this is cheap by the standards of what the MTA is already spending on Penn Station Access for Metro-North. The rewards are substantial: 1:17 trip times from New Haven to Grand Central making off-peak express stops, down from 2 hours today. The big ask isn’t money – the entire point of the report is to figure out how to build high-speed rail on a tight budget. Rather, the big ask is changing the entire planning paradigm of intercity and commuter rail in the United States from reactive to proactive, from incremental to comfortable with groun-up redesigns, from stuck in the 1950s to ready for the transportation needs of the 21st century.

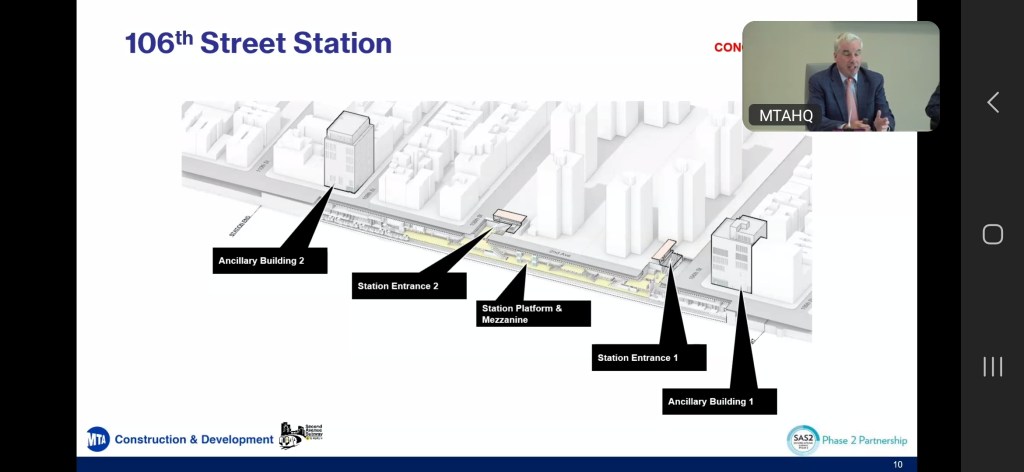

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 Station Design is Incompetent

A few hours ago, the MTA presented on the latest of Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. The presentation includes information about the engineering and construction of the three stations – 106th, 116th, and 125th Streets. The new designs are not good, and the design of 116th in particular betrays severe incompetence about how modern subway stations are built: the station is fairly shallow, but has a mezzanine under the tracks, with all access to or from the station requiring elevator-only access to the mezzanine.

What was in the presentation?

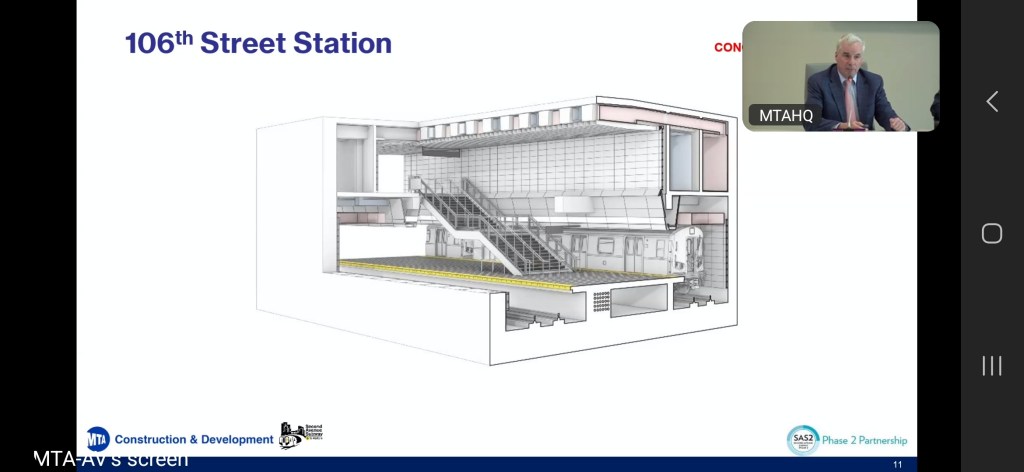

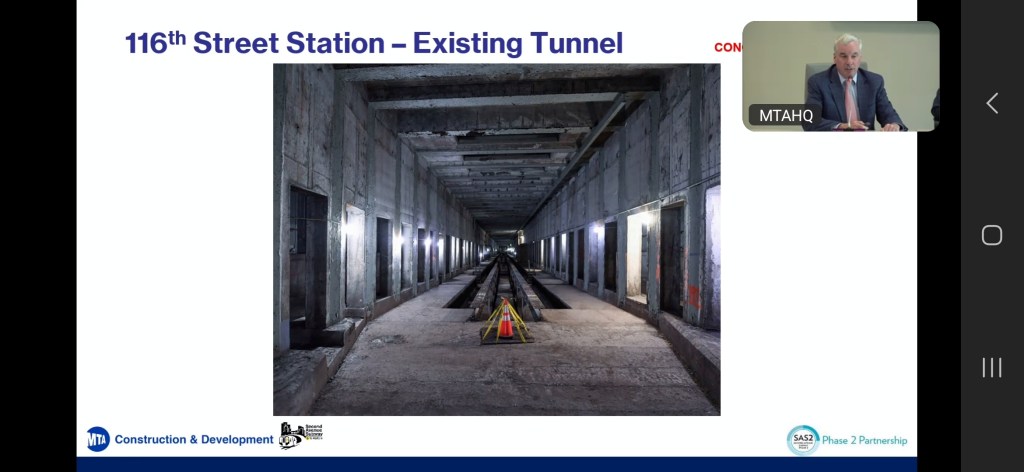

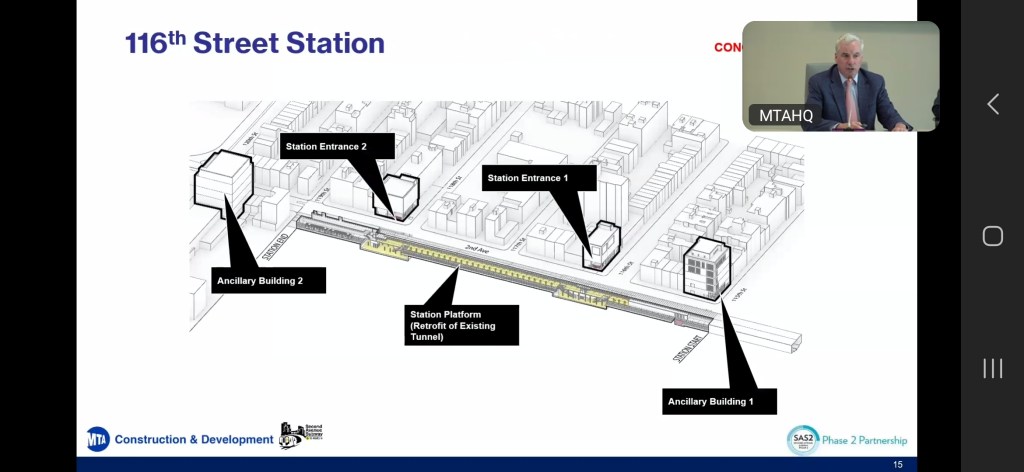

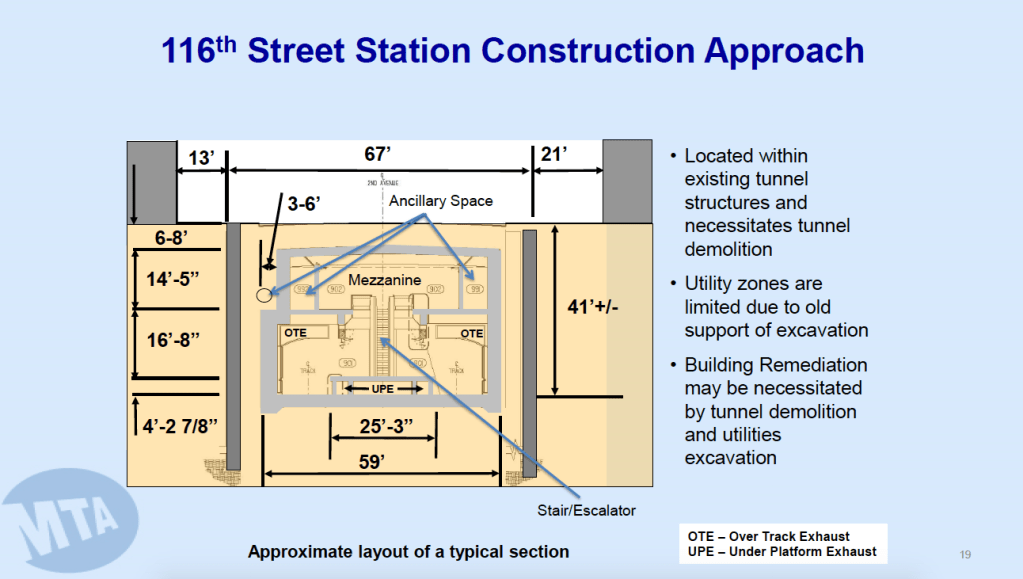

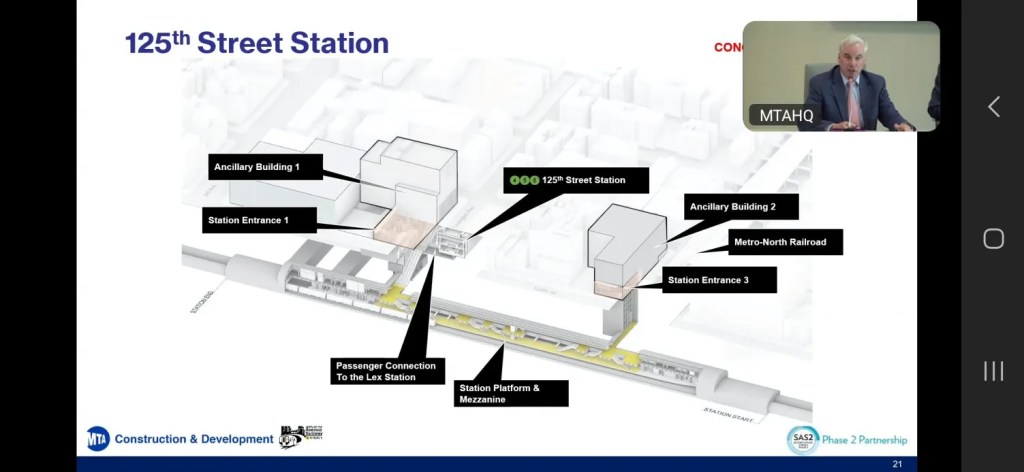

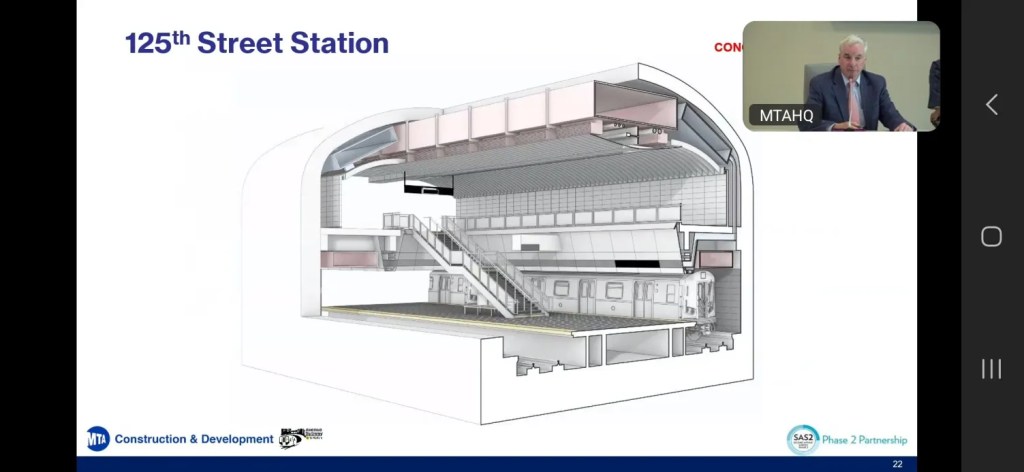

Here is a selection of slides, describing station construction. 106th Street is to be built cut-and-cover; 116th is to use preexisting construction but avoid cut-and-cover to reach them from the top and instead mine access from the bottom; 125th is to be built deep-level, with 125′ deep (38 m) platforms, underneath its namesake street between Lexington and Park Avenues.

The problems with 116th Street

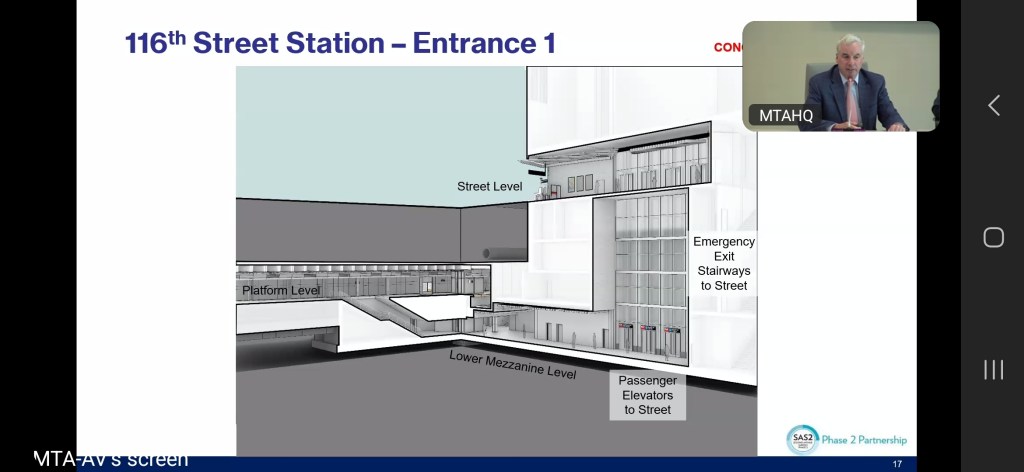

Elevator-only access

Elevator-only access is usually stupid. It’s especially stupid when it’s at a shallow station; as the page 19 slide above shows, the platforms are about 11.5 meters below ground, which is an easy depth for both stair and escalator access.

Now, to be clear, there are elevator-only stations built in countries with reasonable subway construction programs. Sofia on Nya Tunnelbanan is elevator-only, because it is 100 meters below street level, due to the difficult topography of Södermalm and Central Stockholm, in which Sofia, 26 meters above sea level, is right next to Riddarfjärden, 23 meters deep. Emergency access is provided via ramps to the sea-level freeway hugging the north shore of Södermalm, used to construct the mined cavern in the first place. Likewise, the Barcelona L9 construction program, by far the most expensive in Spain and yet far cheaper than in any recent English-speaking country, has elevator-only access to the deep stations, in order to avoid any construction outside a horizontal or vertical tunnel boring machine.

The depth excuse does not exist in East Harlem. 11.5 meters is not an elevator-only access depth. It’s a stair access depth with elevators for wheelchair accessibility. Stairs are planned to be provided only for emergency access, without public usage. Under NFPA 130 the stairs are going to have to have enough capacity for full trains, much more than is going to be required in ordinary service, and they’d lead passengers to the same street as the elevators, nothing like the freeway egress of Sofia.

Below-platform mezzanines

To avoid any shallow construction, the mezzanines will be built below the platforms and not above them. As a result, access to the station means going down a level and then going back up to the platform level. In effect, the station is going to behave as a rather deep station as far as passenger access time to the platforms is concerned: the planned depth is 57′, or 17.4 meters, which means that the total vertical change from street level is around 23.5 meters, twice the actual depth of the platforms.

Dig volume

Even with the reuse of existing infrastructure, the station is planned to have too much space north and south of the platforms, as seen with the locations of the ancillary buildings.

I think that this is due to designs from the 2000s, when the plan was to build all stations with extensive back-of-the-house space on both sides of the platform. Phase 1 was built this way, as we cover in our New York case, and after we yelled at the MTA about it, it eventually shrank the footprint of the stations. 116th’s station start and end are four blocks apart, a total of about 300 meters, comparable to 86th Street; the platform is 186 m wide and the station overall has no reason to be longer than 190-200. But it’s possible the locations of the ancillary buildings were fixed from before the change, in which case the incompetence is not of the current leadership but of previous leadership.

Why?

On Bluesky, I’m seeing multiple activists I think well of assume that this is because the MTA is under pressure to either cut costs or avoid adverse community impact. Neither of these explanations makes much sense in context. 106th Street is planned to be built cut-and-cover, in the same neighborhood as 116th, with the same street width, which rules out the community opposition explanation. Cut-and-cover is cheaper than alternatives, which also rules out the cost explanation.

Rather, what’s going on is that MTA leadership does not know how a modern cut-and-cover subway station looks like. American construction prefers to avoid cut-and-cover even for stations, and over time such stations have been laden with things that American transit managers think are must-haves (like those back-of-the-house spaces) and that competent transit managers know they don’t need to build. They may want to build cut-and-cover, as at 106th, but as soon as there’s a snag, they revert to form and look for alternatives. They complain about utility relocation costs, which are clearly not blocking this method at 106th, and which did not prevent Phase 1’s 96th Street from costing about 2/3 as much as 86th and 72nd per cubic meter dug.

Under pressure to cut costs and shrink the station footprint, the MTA panicked and came up with the best solution the political appointees, that is to say Janno Lieber and Jamie Torres-Springer and their staff, and the permanent staff that they deign to listen to, could do. Unfortunately for New York, their best is not good enough. They don’t know how to build good stations – there are no longer any standardized designs for this that they trust, and the people who know how to do this speak English with an accent and don’t earn enough to command the respect of people on a senior American political appointee’s salary. So they improvise under pressure, and their instincts, both at doing things themselves and at supervising consultants, are not good. To Londoners, Andy Byford is a workhorse senior civil servant, with many like him, and the same is true in other large European cities with large subway systems. But to Americans, the such a civil servant is a unicorn to the point that people came to call him Train Daddy, because this is what he’s being compared with.