Category: New York

The Hempstead Line

This is a writeup I prepared for modernization of the Hempstead Branch of the LIRR in the same style as our ongoing Regional Rail line by line appendices for Boston at TransitMatters, see e.g. here for the Worcester Line. This will be followed up in a few days by a discussion of the writing process and what it means for the advocacy sphere.

Regional rail for New York: the Hempstead Line

New York has one of the most expansive commuter rail networks in the world. Unfortunately, its ridership underperforms such peer megacities as London, Paris, Tokyo, Osaka, and Seoul. Even Berlin has almost twice as much ridership on its suburban rail network, called S-Bahn, as the combined total of the Long Island Railroad, Metro-North, and New Jersey Transit. This is a draft proposal of one component of how to modernize New York’s commuter rail network.

The core of modernization is to expand the market for commuter rail beyond its present-day core of 9-to-5 suburban commuters who live in the suburbs and work in Manhattan. This group already commutes by public transportation at high rates, but drives everywhere except to Manhattan. To go beyond this group requires expanding off-peak service to the point of making the commuter railroads like longer-range, higher-speed Queens Boulevard express trains, with supportive fares and local transit connections.

The LIRR Hempstead Line is a good test case for beginning with such a program. It is fortunate that on this line the capital and operating costs of modernization are low, and service would be immediately useful within the city as well as dense inner suburbs. With better service, the line would still remain useful to 9-to-5 commuters – in fact it would become more useful through higher speed and more flexibility for office workers who sometimes stay at the office until late. But in addition, people could take it for ordinary transit trips, including work trips to job centers in Queens or on Long Island, school trips, or social gatherings with friends in the region.

The Hempstead Line

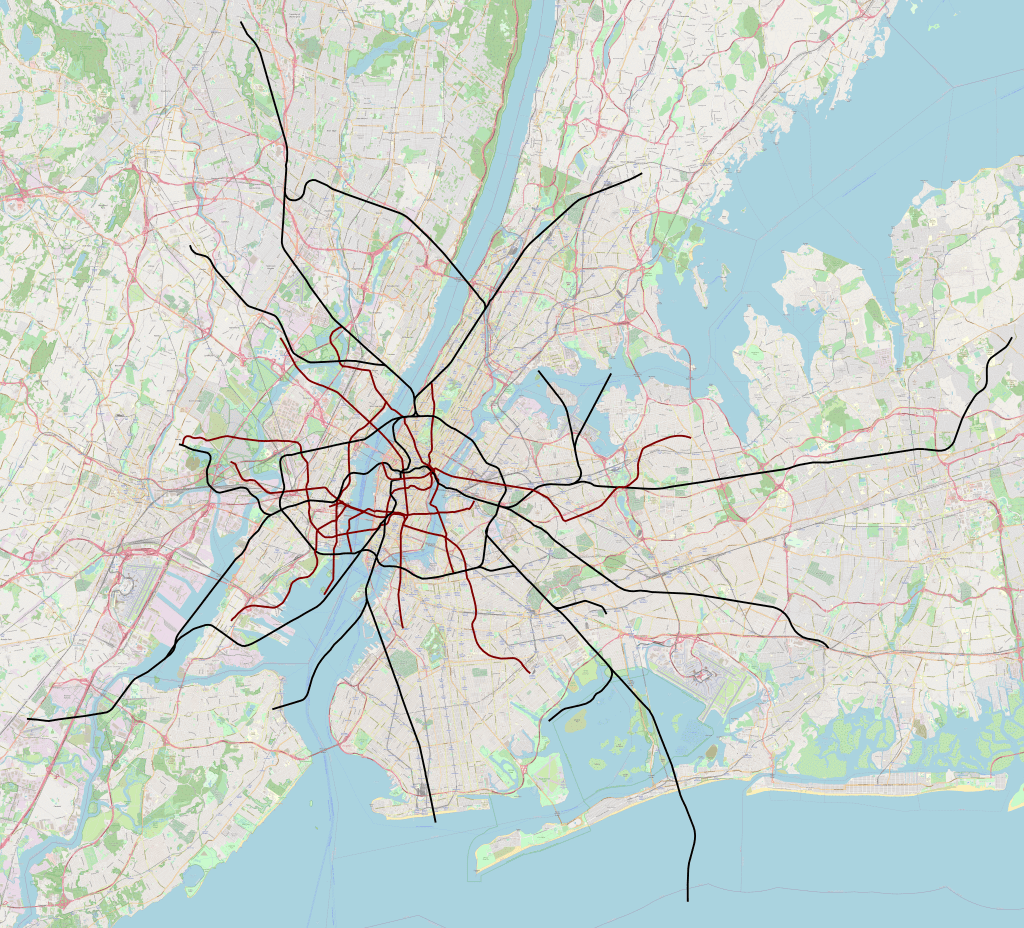

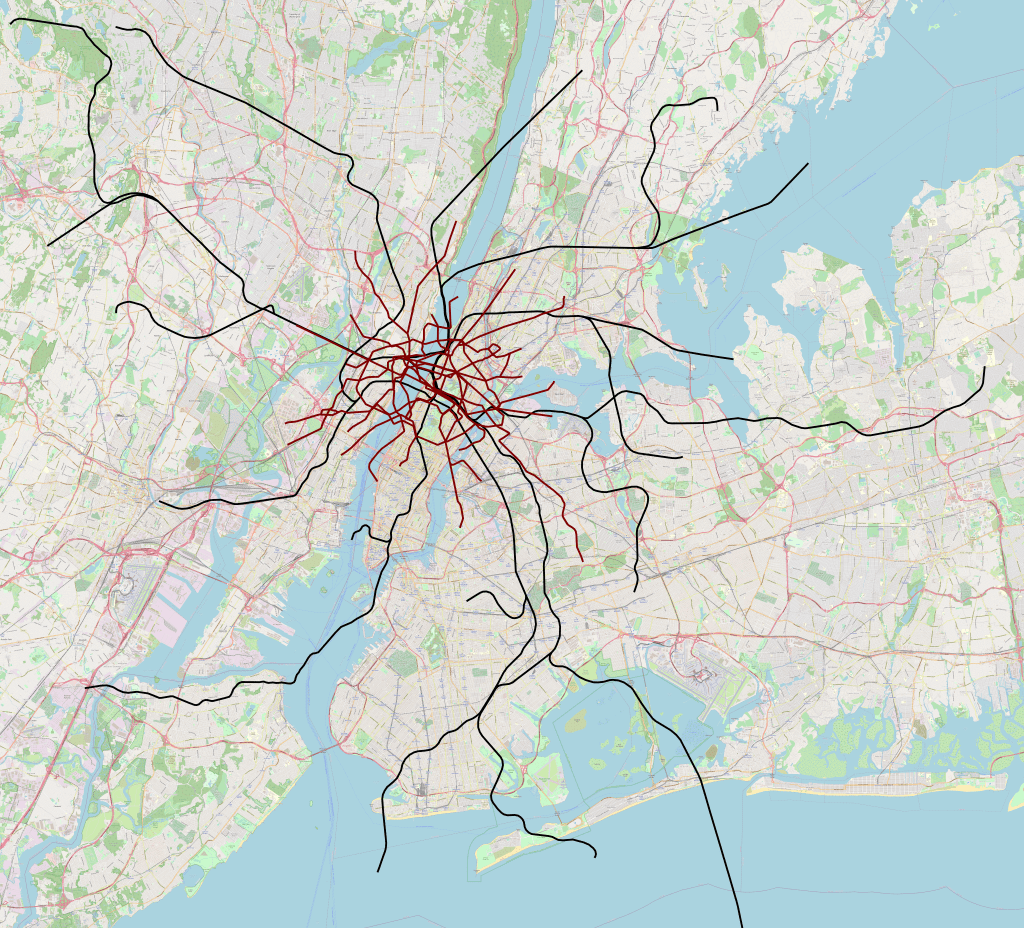

The Hempstead Line consists of the present-day LIRR Hempstead Branch and a branch to be constructed to East Garden City. The Hempstead Branch today is 34 km between Penn Station and Hempstead, of which 24 km lie within New York City and 10 lie within Long Island.

Most trains on the branch today do not serve Penn Station because of the line’s low ridership, but instead divert to the Atlantic Branch to Downtown Brooklyn, and Manhattan-bound passengers change at Jamaica to any of the branches that run through to Midtown. Current frequency is an hourly train off-peak, and a train every 15-20 minutes for a one-hour peak. Peak trains do not all run local, but rather one morning peak train runs express from Bellerose to Penn Station.

Ridership is weak, in fact weaker than on any other line except West Hempstead and the diesel tails of Oyster Bay, Greenport, and Montauk. In the 2014 station counts, the sum of boardings at all stations was 7,000 a weekday, and the busiest stations were Floral Park with 1,500 and Hempstead with 1,200. But commute volumes from the suburbs served by the Hempstead Branch to the city are healthy, about 7,500 to Manhattan and another 10,500 to the rest of the city, many near LIRR stations in Brooklyn and Queens. Moreover, 13,500 city residents work in those suburbs, and they disproportionately live near the LIRR, but very few ride the train. Finally, the majority of the line’s length is within the city, but premium fares and low frequency make it uncompetitive with the subway, and therefore ridership is weak.

Despite the weak ridership, the line is a good early test case for commuter rail modernization in New York. Most of it lies in the city, paralleling the overcrowded Queens Boulevard Line of the subway. As explained below, there is also a healthy suburban job market, which not only attracts many city reverse-commuters today, but is likely to attract more if public transportation options are better.

Destinations

The stations of the Hempstead Line already have destinations that people can walk to, so that if service is improved as in the following outline, people can ride the LIRR there. These include the following:

- JFK, accessible via Jamaica Station.

- Adelphi University, midway between Garden City and Nassau Boulevard, walkable to both.

- York University, fairly close to Jamaica and very close to a proposed Merrick Boulevard infill station.

- Primary and secondary schools near stations within the city, where students often have long commutes.

- Penn Station as an intercity station – passengers from Queens and Long Island traveling to Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington would benefit from faster and more frequent trains.

- Many jobs near stations in Queens and on Long Island as described below.

Jobs

Within a kilometer of all stations except Penn Station, there is a total of 182,000 jobs in Queens and 50,000 on Long Island. The spine of the Main Line through Queens closely parallels the overcrowded Queens Boulevard express tracks, and in the postwar era was proposed for a Queens Super-Express subway line. But on Long Island, too, it serves the edge city cluster of Garden City and the city center of Hempstead. All of those jobs should generate healthy amounts of reverse-peak ridership and ridership terminating short of Manhattan.

| Station | Jobs within 1 km |

| Penn Station | 522904 |

| Queensboro Plaza (@ QB) | 62266 |

| Sunnyside Jct (@ 43th) | 23655 (with QBP: 78219) |

| Woodside | 14409 (with Sunnyside: 36469) |

| Triboro Jct (@ 51st Ave) | 14339 (Elmhurst Hospital) |

| Forest Hills | 21926 |

| Kew Gardens | 17855 |

| Jamaica | 19794 |

| Merrick Blvd | 17020 (with Jamaica: 29260) |

| Hollis | 2918 |

| Queens Village | 4758 |

| Bellerose | 3014 (with QV: 7735) |

| Floral Park | 5389 (with Bellerose: 6776) |

| Stewart Manor | 3203 |

| Nassau Blvd | 859 |

| Garden City | 9643 |

| Country Life Press | 5404 (with GC: 10865) |

| Hempstead | 10896 (with CLP: 15823) |

| East Garden City (@Oak) | 12461 |

| Nassau Center (@Endo) | 6352 (with EGC: 17904) |

Required infrastructure investment

The LIRR has fairly high quality of infrastructure. Every single station has high platforms, permitting level boarding to trains with doors optimized for high-throughput stations. Most of the system is electrified with third rail, including the entirety of the Hempstead Branch. High-frequency regional rail can run on this system without any investment. However, to maximize utility and reliability, some small capital projects are required.

Queens Interlocking separation

Queens Interlocking separates the Hempstead Line from the Main Line. Today, the junction is flat: two two-track lines join together to form a four-track line, but trains have to cross opposing traffic at-grade. The LIRR schedules trains around this bottleneck, but it makes the timetable more fragile, especially at rush hour, when trains run so frequently that there are not enough slots for recovering from delays.

The solution is to grade-separate the junction. The project should also be bundled with converting Floral Park to an express station with four tracks and two island platforms; local trains should divert to the shorter Hempstead Line and all express trains should continue on the longer Main Line to Hicksville and points east. Finding cost figures for comparable projects is difficult, but Harold Interlocking was more complex and cost $250 million to grade-separate, even with a large premium for New York City projects.

Turnout modification

Trains switch from one track to another at a junction using a device called a switch or turnout. There are two standards for turnouts: the American standard, dating to the 1890s, in which the switch is simpler to construct but involves an abrupt change in azimuth, called a secant switch; and the German standard from 1925, adopted nearly globally, in which the switch tapers to a thin blade to form what is called a tangential switch.

Passengers on a train that goes on a secant turnout are thrown sideways. To maintain adequate safety, trains are required to traverse such switches very slowly, at a speed comparable to 50 mm of cant deficiency on the curve of the switch. In contrast, German and French turnout standards permit 100 mm on their tangential switches; the double cant deficiency allows a nominal 40% increase in speed on a switch of given number (such as an American #10 vs. a German 1:10 or a French 0.1, all measuring the same frog angle). The real speed increase is usually larger because the train sways less, which creates more space in constrained train station throats.

With modern turnouts, Penn Station’s throat, currently limited to 10 15 mph (16 24 km/h), could be sped up to around 50 km/h, saving every train around 2 minutes just in the last few hundred meters into the station. Installation typically can be done in a few weekends, at a cost of around $200,000 per physical switch, which corresponds to high single-digit millions for a station as large as Penn. Amtrak has even taken to installing tangential switches on some portions of the Northeast Corridor, though not at the stations; unfortunately, instead of building these switches locally at local costs, it pays about $1.5 million per unit, even though in Germany and elsewhere in Europe installation costs are similar to those of American secant switches.

Speed

In addition to modifying the physical switches as outlined above, the LIRR should pursue speedups through better use of the rolling stock and better timetabling. In fact, the trains currently running are capable of 0.9 m/s^2 acceleration, but are derated to 0.45 without justification, which increases the time cost of every stop by about 30 seconds. In addition, LIRR timetables are padded about 20% over the technical running time, even taking into account the slow Penn Station throat and the derating. A more appropriate padding factor is 7%, practiced throughout Europe even on very busy mainlines, such as the Zurich station throat, where traffic is comparable to that of the rush hour LIRR.

To get to 7%, it is necessary to design the infrastructure so that delays do not propagate. Grade-separating Queens Interlocking is one key component, but another is better timetabling. Complex timetables require more schedule padding, because each train has a unique identity, and so if it is late, other trains on the line cannot easily substitute for it. In contrast, subway-style service with little branching is the easiest to schedule, because passengers do not distinguish different trains; not for nothing, the 7 and L trains, which run without sharing tracks with other lines, tend to be the most punctual and were the first two to implement CBTC signaling.

In the case of the LIRR, achieving this schedule requires setting things up so that all Hempstead Line trains run local on the Main Line to Penn Station, and all trains from Hicksville and points east run express to Grand Central. Atlantic and Babylon Branch trains can run to Atlantic Terminal, or to the local tracks to Penn, depending on capacity; Babylon can presumably run to Penn while the Far Rockaway and Long Beach Lines, already separated from the rest of the system, can run to Downtown Brooklyn.

Infill stations

Within the city, commuter rail station spacing is sparse. The reason is that the frequency and fares are uncompetitive. Historically, the LIRR had tight spacing in the city, with nine more stations on the Main Line within city limits, but it closed most of them in the 1920s and 30s as the subway opened to Queens. The subway offered very high frequency for a 5-cent fare compared with the LIRR’s 20-to-30-cent fares. Today, the fares remain unequal, but this can be changed, as can the off-peak frequency. In that case, it becomes useful to open some additional infill stops.

The cost of an infill station is unclear. There is a wide range; Boston and Philadelphia both open infill stations with high platforms for about $15-25 million each, and the European range is lower. Urban infill stations in constrained locations like Sunnyside can be more expensive, but not by more than a factor of 2. In the past, LIRR and Metro-North infill stops, such as those for Penn Station Access, have gone up to the three figures, and it is critical to prevent such costs from recurring.

Queensboro Plaza

This station is already part of the Sunnyside Yards master plan, by the name Sunnyside, and is supposed to begin construction immediately after the completion of the East Side Access project. This proposal gives it a different name only because there is another station called Sunnyside (see below).

Located at the intersection of the Main Line with Queens Boulevard, this would be a local station for trains heading toward Penn Station. It is close to the Queensboro Plaza development, which has the tallest building in the city outside Manhattan and more jobs than anywhere in the Outer Boroughs save perhaps Downtown Brooklyn. Within a kilometer of the station there are more than 60,000 jobs already, and this is before planned redevelopment of Sunnyside Yards.

Sunnyside Junction

The opening of East Side Access and Penn Station Access will create a zone through Sunnyside Yards where trains will run in parallel. LIRR trains will run toward either Penn Station or Grand Central, and Metro-North trains will run toward Penn Station.

It is valuable to build an express station to permit passengers to transfer. This way, passengers from the Penn Station Access stations in the Bronx could connect to Grand Central, and passengers from farther out on the New Haven Line who wish to go to Penn Station Grand Central could board a train to either destination, improving the effective frequency. Likewise, LIRR passengers could change to a different destination across the platform at Sunnyside, improving their effective frequency.

The area is good for a train station by itself as well. It has 24,000 jobs within a kilometer, more than any other on the line except Penn Station and Queensboro Plaza. There is extensive overlap with the 1 km radius of Queensboro Plaza, but even without the overlap, there are 16,000 jobs, almost as many as within 1 km of Jamaica, and this number will rise with planned redevelopment of the Yards.

Triboro Junction

This station is at 51st Avenue, for future transfers to the planned Triboro RX orbital. Population and job density here are not high by city standards: the 14,000 jobs include 5,000 at Elmhurst Hospital on Broadway, which is at the periphery of the 1 km radius and is poorly connected to the railroads on the street network. The value of the station is largely as a transfer for passengers from Astoria and Brooklyn.

Merrick Blvd

About 1.5 km east of Jamaica, Merrick Boulevard catches the eastern end of the Jamaica business district. It also connects to one of Eastern Queens’ primary bus corridors, and passengers connecting from the buses to Manhattan would benefit from being able to transfer outside the road traffic congestion around Jamaica Station.

The East Garden City extension

The Hempstead Branch was historically part of the Central Railroad of Long Island. To the west, it continued to Flushing, which segment was abandoned in 1879 as the LIRR consolidated its lines. To the east, it continued through Garden City and what is now Levittown and ran to Babylon on a segment the LIRR still uses sporadically as the Central Branch. The right-of-way between Garden City and Bethpage remains intact, and it is recommended that it be reactivated at least as far as East Garden City, with an East Garden City station at Oak Street and a Nassau Center station at Endo Boulevard. This is for two reasons.

Jobs

Long Island is unusually job-poor for a mature American suburb. This comes partly from the lack of historic town centers like Stamford or Bridgeport on the New Haven Line or White Plains and Sleepy Hollow in Westchester. More recently, it is also a legacy of Robert Moses, who believed in strict separation of urban jobs from suburban residences and constructed the parkway system to feed city jobs. As a result of both trends, Long Island has limited job sprawl.

However, East Garden City specifically is one of two exceptions, together with Mineola: it has a cluster with 18,000 jobs within 1 km of either of the two recommended stations. Reopening the branch to East Garden City would encourage reverse-commuting by train.

Demand balance

Opening a second branch on the Hempstead Line helps balance demand in two separate ways. First, the population and job densities in Queens are a multiple of those of Long Island and always will be, and therefore the frequency of trains that Queens would need, perhaps a local train every 5 minutes all day, would grossly overserve Hempstead. At the distance of Hempstead or East Garden City, only a train every 10-15 minutes (in a pinch, even every 20) is needed, and so having two branches merging for city service is desirable.

And second, having frequent Hempstead Line local service forces all of the trains on the outer tracks of the Main Line in Queens to run local, just as the subway has consistent local and express tracks. The LIRR gets away with mixing different patterns on the same track because local frequency is very low; at high frequency, it would need to run like the subway. Because passengers from outer suburbs should get express trains, it is valuable to build as much infrastructure as possible to help feed the local tracks, which would be the less busy line at rush hour.

Train access and integration

Today, the LIRR primarily interfaces with cars. LIRR capital spending goes to park-and-rides, and it is expected that riders should drive to the most convenient park-and-ride, even on a different branch from the one nearest to their home. This paradigm only fills trains at rush hour to Manhattan, and is not compatible with integrated public transportation. In working-class suburbs like Hempstead, many take cheaper, slower buses. Instead, the system should aim for total integration at all levels, to extend the city and its relative convenience of travel without the car into suburbia.

Fare integration

Fares must be mode-neutral. This means that, just as within the city the fares on the buses and subways are the same, everywhere else in the region a ticket should be valid on all modes within a specified zone. Within the city, all trains and buses should charge the same fares, with free intermodal transfers.

Such a change would entice city residents to switch from the overcrowded E and F trains to the LIRR, which is by subway standards empty: the average Manhattan-bound morning rush hour LIRR train has only 85% of its seats occupied. In fact, if every E or F rider switches to the LIRR, which of course will not happen as they don’t serve exactly the same areas, then the LIRR’s crowding level, measured in standees per m^2 of train area, will be lower than that of the E and F today.

In the suburbs, the fares can be higher than in the city, in line with the higher operating costs over longer distances. But the fares must likewise be mode-neutral, with free transfers. For example, within western Nassau County, fares could be set at 1.5 times subway fare, which means that all public transit access between the city and Hempstead would cost $190 monthly or $4.00 one-way, by any mode: NICE bus, the LIRR, or a bus-train combo.

This would be a change from today’s situation, where premium-price trains only attract middle-class riders, while the working class rides buses. In fact, the class segregation today is such that in the morning rush hour, trains run full to Manhattan and empty outbound and NICE buses, which carry working-class reverse-commuters, are the opposite. Thus, half of each class’s capacity is wasted.

Bus redesign and bus access

Instead of competing with the trains, buses should complement them, just as they do within the city with the subway. This means that the NICE system should be designed along the following lines:

- More service perpendicular to the LIRR, less parallel to it.

- Bus nodes at LIRR stations, enabling passengers to connect.

- Timed transfers: at each node the buses should arrive and depart on the same schedule, for example on the hour every 20 minutes, to allow passengers to change with minimal hassle. This includes timed transfers with the trains if they run every 15 minutes or worse, but if they run more frequently, passengers can make untimed connections as they do in the city.

Bike access

Urban and suburban rail stations should include bike parking. Bikes take far less space than cars, and thus bike park-and-ride stations in the Netherlands can go up to thousands of stalls while still maintaining a walkable urban characteristic.

In many countries, including the United States on the West Coast, systems encourage riders to bring their bikes with them on the train. However, in New York it’s preferably to adopt the Dutch system, in which bikes are not allowed on trains, and instead stations offer ample bike parking. This is for two reasons. First, New York is so large and has such a rush hour capacity crunch that conserving capacity on board each train is important. And second, cultures that bring bikes on trains, such as Northern California, arise where people take trains to destinations that are not walkable from the station; but in New York, passengers already connect to the subway for the last mile from Penn Station to their workplaces, and thus bikes are not necessary.

Train scheduling

Trains should run intensively, with as little distinction between the peak and off-peak as is practical. At most, the ratio between peak and off-peak service should be 2:1. Already, the LIRR’s high ratio, 4:1 on the Hempstead Branch, means that trains accumulate at West Side Yard at the end of the morning peak. The costs of raising off-peak service to match peak service are fairly low to begin with, but they are especially low when the alternative is to expand a yard in Midtown Manhattan, paying Midtown Manhattan real estate prices.

For an early timetable in which the Babylon Branch provides extra frequency in the city, the following frequencies are possible:

| Segment | Peak | Off-peak |

| Penn Station-Garden City | 5 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Garden City-Hempstead | 10 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Garden City-Nassau Center | 10 minutes | 20 minutes |

A more extensive service, with all LIRR South Side diverting to a separate line from the Main Line, perhaps the Atlantic Branch to Downtown Brooklyn, requires an increase in off-peak urban service:

| Segment | Peak | Off-peak |

| Penn Station-Garden City | 5 minutes | 5 minutes |

| Garden City-Hempstead | 10 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Garden City-Nassau Center | 10 minutes | 10 minutes |

Further increases in peak service may be warranted for capacity reasons if there is more redevelopment than currently planned or legal by city and suburban zoning codes.

Travel times

With rerating the LIRR equipment to its full acceleration rate, a fix to the Penn Station throat, and standard European schedule padding, the following timetable is feasible:

| Station | Time (current) | Time (future, M7) | Time (Euro-EMU) |

| Penn Station | 00:00 | 00:00 | 00:00 |

| Queensboro Plaza | — | 00:04 | 00:04 |

| Sunnyside Jct | — | 00:06 | 00:06 |

| Woodside | 00:10 | 00:09 | 00:09 |

| Triboro Jct | — | 00:12 | 00:11 |

| Forest Hills | 00:15 | 00:15 | 00:13 |

| Kew Gardens | 00:17 | 00:17 | 00:15 |

| Jamaica | 00:22 | 00:19 | 00:17 |

| Merrick Blvd | — | 00:21 | 00:19 |

| Hollis | 00:29 | 00:24 | 00:21 |

| Queens Village | 00:31 | 00:26 | 00:23 |

| Bellerose | 00:35 | 00:28 | 00:25 |

| Floral Park | 00:38 | 00:30 | 00:27 |

| Stewart Manor | 00:41 | 00:32 | 00:29 |

| Nassau Blvd | 00:44 | 00:34 | 00:31 |

| Garden City | 00:46 | 00:36 | 00:33 |

| Country Life Press | 00:49 | 00:38 | 00:35 |

| Hempstead | 00:52 | 00:40 | 00:37 |

| East Garden City | — | 00:38 | 00:35 |

| Nassau Center | — | 00:40 | 00:37 |

Providing peak service every 10 minutes to each of Hempstead and Nassau Center requires 20 trainsets, regardless of whether they are existing LIRR equipment or faster, lighter European trainsets.

The Need to Remove Bad Management

I’ve talked a lot recently about bad management as a root cause of poor infrastructure, especially on Twitter. The idea, channeled through Richard Mlynarik, is that the main barrier to good US infrastructure construction, or at least one of the main barriers, is personal incompetence on behalf of decisionmakers. Those decisionmakers can be elected officials, with levels of authority ranging from governors down to individual city council members; political appointees of said officials; quasi-elected power brokers who sit on boards and are seen as representative of some local interest group; public-sector planners; or consultants, usually ones who are viewed as an extension of the public sector and may be run by retired civil servants who get a private-sector salary and a public-sector pension. In this post I’d like to zoom in on the managers more than on the politicians, not because the politicians are not culpable, but because in some cases the managers are too. Moreover, I believe removal of managers with a track record of failure is a must for progress.

The issue of solipsism

Spending any time around people who manage poorly-run agencies is frustrating. I interview people who are involved in successful infrastructure projects, and then I interview ones who are involved in failed ones, and then people in the latter group are divided into two parts. Some speak of the failure interestingly; this can involve a blame game, typically against senior management or politics, but doesn’t have to, for example when Eric and I spoke to cost estimators about unit costs and labor-capital ratios. But some do not – and at least in my experience, the worst cases involve people who don’t acknowledge that something is wrong at all.

I connect this with solipsism, because this failure to acknowledge is paired with severe incuriosity about the rest of the world. A Boston-area official who I otherwise respect told me that it is not possible to electrify the commuter rail system cheaply, because it is 120 years old and requires other investments, as if the German, Austrian, etc. lines that we use as comparison cases aren’t equally old. The same person then said that it is not possible to do maintenance in 4-hour overnight windows, again something that happens all the time in Europe, and therefore there must be periodic weekend service changes.

A year and a half ago I covered a meeting that was videotaped, in which New Haven-area activists pressed $200,000/year managers at Metro-North and Connecticut Department of Transportation about their commuter rail investments. Those managers spoke with perfect confidence about things they had no clue about, saying it’s not possible that European railroads buy multiple-units for $2.5 million per car, which they do; one asserted the US was unique in having wheelchair accessibility laws (!), and had no idea that FRA reform as of a year before the meeting permitted lightly-modified European trains to run on US track.

The worst phrase I keep hearing: apples to apples. The idea is that projects can’t really be compared, because such comparisons are apples to oranges, not apples to apples; if some American project is more expensive, it must be that the comparison is improper and the European or Asian project undercounted something. The idea that, to the contrary, sometimes it’s the American project that is easier, seems beyond nearly everyone who I’ve talked to. For example, most recent and under-construction American subways are under wide, straight streets with plenty of space for the construction of cut-and-cover station boxes, and therefore they should be cheaper than subways built in the constrained center of Barcelona or Stockholm or Milan, not more expensive.

What people are used to

In Massachusetts, to the extent there is any curiosity about rest-of-world practice, it comes because TransitMatters keeps pushing the issue. Even then, there is reticence to electrify, which is why the state budget for regional rail upgrades in the next few years only includes money for completing the electrification of sidings and platform tracks on the already-electrified Providence Line and for short segments including the Fairmount Line, Stoughton Branch, and inner part of the Newburyport and Rockport Lines. In contrast, high platforms, which are an ongoing project in Boston, are easier to accept, and thus the budget includes more widespread money for it, even if it falls short of full high-level platforms at every station in the system.

In contrast, where high platform projects are not so common, railroaders find excuses to avoid them. New Jersey Transit seems uninterested in replacing all the low platforms on its system with high platforms, even though the budget for such an operation is a fraction of that of the Gateway tunnel, which the state committed $2.5 billion to in addition to New York money and requested federal funding. The railroad even went as far as buying new EMUs that are compatible not with the newest FRA regulations, which are similar to UIC ones used in Europe, but with the old ones; like Metro-North’s management, it’s likely NJ Transit’s had no idea that the regulations even changed.

The issue of what people are used to is critical. When you give someone authority over other people and pay them $200,000 a year, you’re signaling to them, “never change.” Such a position can reward ambition, but not the ambition of the curious grinder, but that of the manager who makes other people do their work. People in such a position who do not know what “electronics before concrete” means now never will learn, not will they even value the insights of people who have learned. The org chart is clear: the zoomer who’s read papers about Swiss railroad planning works for the boomer who hasn’t, and if the boomer is uncomfortable with change, the zoomer can either suck it up or learn to code and quit for the private sector.

You can remove obstructionist managers

From time to time, a powerful person who refuses to use their power except in the pettiest ways accidentally does something good. Usually this doesn’t repeat itself, despite the concrete evidence that it is possible to do things thought too politically difficult. For example, LIRR head Helena Williams channeled Long Island NIMBYism and opposed Metro-North’s Penn Station Access on agency turf grounds – it would intrude on what Long Islanders think is their space in the tunnels to Penn Station. But PSA was a priority for Governor Andrew Cuomo, so Cuomo fired Williams, and LIRR opposition vanished.

This same principle can be done at scale. Managers who refuse to learn from successful examples, which in capital construction regardless of mode and in operations of mainline rail are never American and rarely in English-speaking countries, can and should be replaced. Traditional railroaders who say things are impossible that happen all the time in countries they look down on can be fired; people from those same countries will move to New York for a New York salary.

This gets more important the more complex a project gets. It is possible, for example, to build high-speed rail between Boston and Washington for a cost in the teens of billions and not tens, let alone hundreds, but not a single person involved in any of the present effort can do that, because it’s a project with many moving parts and if you trust a railroad manager who says “you can’t have timed overtakes,” you’ll end up overbuilding unnecessary tunnels. In this case, managers with a track record of looking for excuses why things are impossible instead of learning from places that do those things are toxic to the project, and even kicking them up is toxic, because their subordinates will learn to act like that too. The squeaky wheel has to be removed and thrown into the garbage dumpster.

And thankfully, squeaky wheels that get thrown into the dumpster stop squeaking. All of this is possible, it just requires elected officials who have the ambition to take risks to effect tangible change rather than play petty office politics every day. Cuomo is the latter kind of politician, but he proved to everyone that a more competent leader could replace solipsists with curious learners and excusemongers with experts.

High Costs are not About Scarcity

I sometimes see a claim in comments here or on social media that the reason American costs are so high is that scarcity makes it hard to be efficient. This can be a statement about government practice: the US government supposedly doesn’t support transit enough. Sometimes it’s about priorities, as in the common refrain that the federal government should subsidize operations and not just capital construction. Sometimes it’s about ideology – the idea that there’s a right-wing attempt to defund transit so there’s siege mentality. I treat these three distinct claims as part of the same, because all of them really say the same thing: give American transit agencies more money without strings attached, and they’ll get better. All of these claims are incorrect, and in fact high costs cannot be solved by giving more money – more money to agencies that waste money now will be wasted in the future.

The easiest way to see that theories of political precarity or underresourcing are wrong is to try to see how agencies would react if they were beset mostly by scarcity as their defenders suggest. For example, the federal government subsidizes capital expansion and not operations, and political transit advocates in the United States have long called for operating funds. So, if transit agencies invested rationally based on this restrictions, what would they do? We can look at this, and see that this differs greatly from how they actually invest.

The political theory of right-wing underresourcing is similarly amenable to evaluation using the same method. Big cities are mostly reliant not on federal money but state and local money, so it’s useful to see how different cities react to different threat levels of budget cuts. It’s also useful to look historically at what happened in response to cuts, for example in the Reagan era, and spending increases, for example in the stimulus in the early Obama era and again now.

How to respond to scarcity

A public transit agency without regular funding would use the prospects of big projects to get other people’s money (OPM) to build longstanding priorities. This is not hypothetical: the OPM effect is real, and for example people have told Eric and me that Somerville used the original Green Line Extension to push for local amenities, including signature stations and a bike lane called the Community Path. In New York, the MTA has used projects that are sold to the public as accessibility benefits to remodel stations, putting what it cares about (cleaning up stations) on the budget of something it does not (accessibility).

The question is not whether this effect is real, but rather, whether agencies are behaving rationally, using OPM to build useful things that can be justified as related to the project that is being funded. And the answer to this question is negative.

For every big federally-funded project, one can look at plausible tie-ins that can be bundled into it that enhance service, which the Somerville Community Path would not. At least the ongoing examples we’ve been looking at are not so bundled. Consider the following misses:

Green Line Extension

GLX could include improvements to the Green Line, and to some extent does – it bundles a new railyard. However, there are plenty of operational benefits on the Green Line that are somewhere on the MBTA’s wishlist that are not part of the project. Most important is level boarding: all vehicles have a step up from the platform, because the doors open outward and would strike the platform if there were wheelchair-accessible boarding. The new vehicles are different and permit level boarding, but GLX is not bundling full level boarding at all preexisting stations.

East Side Access and Gateway

East Side Access and Gateway are two enormous commuter rail projects, and are the world’s two most expensive tunnels per kilometer. They are tellingly not bundled with any capital improvements that would boost reliability and throughput: completion of electrification on the LIRR and NJ Transit, high platforms on NJ Transit, grade separations of key junctions between suburban branches.

The issue of operating expenses

More broadly, American transit agencies do not try to optimize their rail capital spending around the fact that federal funding will subsidize capital expansion but not operations. Electrification is a good deal even for an agency that has to fund everything from one source, cutting lifecycle costs of rolling stock acquisition and maintenance in half; for an agency that gets its rolling stock and wire from OPM but has to fund maintenance by itself, it’s an amazing investment with no downside. And yet, American commuter rail agencies do not prioritize it. Nor do they prioritize high platforms – they invest in them but in bits and pieces. This is especially egregious at SEPTA, which is allowed by labor agreement to remove the conductors from its trains, but to do so needs to upgrade all platforms to level boarding, as the rolling stock has manually-operated trap doors at low-platform stations.

Agencies operating urban rail do not really invest based on operating cost minimization either. An agency that could get capital funding from OPM but not operating funding could transition to driverless trains; American agencies do not do so, even in states with weak unions and anti-union governments, like Georgia and Florida. New York specifically is beset by unusually high operating expenses, due to very high maintenance levels, two-person crews, and inefficient crew scheduling. If the MTA has ever tried to ask for capital funding to make crew scheduling more efficient, I have not seen it; the biggest change is operational, namely running more off-peak service to reduce shift splitting, but it’s conceivable that some railyards may need to be expanded to position crews better.

Finally, buses. American transit agencies mostly run buses – the vast majority of US public transport service is buses, even if ridership splits fairly evenly between buses and trains. The impact of federal aid for capital but not operations is noticeable in agency decisions to upgrade a bus route to rail perhaps prematurely in some medium-size cities. It’s also visible in bus replacement schedules: buses are replaced every 12 years because that’s what the Federal Transit Administration will fund, whereas in Canada, which has the same bus market and regulations but usually no federal funding for either capital or operations, buses are made to last slightly longer, around 15 years.

It’s hard to tell if American transit agencies are being perfectly rational with bus investment, because a large majority of bus operating expenses are the driver’s wage, which is generally near market rate. That said, the next largest category is maintenance, and there, it is possible to be efficient. Some agencies do it right, like the Chicago Transit Authority, which replaces 1/12 of its fleet every year to have long-term maintenance stability, with exactly 1/12 of the fleet up for mid-life refurbishment each year. Others do it wrong – the MTA buys buses in bunches, leading to higher operating expenses, even though it has a rolling capital plan and can self-fund this system in years when federal funds are not forthcoming.

Right-wing budget cuts

Roughly the entirety of the center-right policy sphere in the United States is hostile to public transportation. The most moderate and least partisan elements of it identify as libertarian, like Cato and Reason, but mainstream American libertarianism is funded by the Koch Brothers and tends toward climate change denial and opposition to public transportation even where its natural constituency of non-left-wing urbane voters is fairly liberal on this issue. The Manhattan Institute is the biggest exception that I’m aware of – it thinks the MTA needs to cut pension payments and weaken the unions but isn’t hostile to the existence of public transportation. In that environment, there is a siege mentality among transit agencies, which associate any criticism on efficiency grounds as part of a right-wing strategy to discredit the idea of government.

Or is there?

California does not have a Republican Party to speak of. The Democrats have legislative 2/3 majorities, and Senate elections, using a two-round system, have two Democrats facing each other in the runoff rather than a Democrat and a Republican. In San Francisco, conservatism is so fringe that the few conservatives who remain back the moderate faction of city politics, whose most notable members are gay rights activist and magnet for alt-right criticism Scott Wiener, (until his death) public housing tenant organizer Ed Lee, and (currently) Mayor London Breed, who is building homeless shelters in San Francisco over NIMBY objections. The biggest organized voices in the Bay Area criticizing the government on efficiency grounds and asserting that the private sector is better come from the tech industry, and usually the people from that industry who get involved with politics are pro-immigration climate change hawks. Nobody is besieging the government in the Bay Area. Nor is anybody besieging public transit in particular – it is popular enough to routinely win the required 2/3 majority for tax hikes in referendums.

In New York, this is almost as true. The Democrats have a legislative 2/3 majority as of the election that just concluded, there does not appear to be a serious Republican candidate for either mayor or governor right now, and the Manhattan Institute recognizes its position and, on local issues of governance, essentially plays the loyal opposition. The last Republican governor, George Pataki, backed East Side Access, trading it for Second Avenue Subway Phase 1, which State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver favored.

One might expect that the broad political consensus that more public transportation is good in New York and the Bay Area would enable long-term investment. But it hasn’t. The MTA has had five-year capital plans for decades, and has known it was going to expand with Second Avenue Subway since the 1990s. BART has regularly gotten money for expansion, and Caltrain has rebuilt nearly all of its platforms in the last generation without any attempt at level boarding.

How a competent agency responds to scarcity

American transit agencies’ extravagant capital spending is not in any way a rational response to any kind of precarity, economic or political. So what is? The answer is, the sum total of investment decisions made in most low-cost countries fits the bill well.

Swiss planning maxims come out of a political environment without a left-wing majority; plans for high-speed rail in the 1980s ran into opposition on cost grounds, and the Zurich U-Bahn plans had lost two separate referendums. The kind of planning Switzerland has engaged in in the last 30 years to become Europe’s strongest rail network came precisely because it had to be efficient to retain public trust to get funds. The Canton of Zurich has to that end had to come up with a formula to divide subsidies between different municipalities with different ideas of how much public services they want, and S-Bahn investment has always been about providing the best passenger experience at the lowest cost.

Elsewhere in Europe, one sees the same emphasis on efficiency in the Nordic countries. Scandinavia as a whole has a reputation for left-wing politics, because of its midcentury social democratic dominance and strong welfare states. But as a region it also practices hardline monetary austerity, to the point that even left-led governments in Sweden and Finland wanted to slow down EU stimulus plans during the early stages of the corona crisis. There is a great deal of public trust in the state there, but it is downstream of efficiency and not upstream of it – high-cost lines get savaged in the press, which engages in pan-Nordic comparisons to assure that people get value for money.

Nor is there unanimous consensus in favor of public transportation anywhere in Europe that I know of, save Paris and London. Center-right parties support cars and oppose rail in Germany and around it. Much of the Swedish right loathes Greta Thunberg, and the center-right diverted all proceeds from Stockholm’s congestion charge to highway construction. The British right has used the expression “war on the motorist” even more than the American right has the expression “war on cars.” The Swiss People’s Party is in government as part of the grand coalition, has been the largest party for more than 20 years, and consistently opposes rail and supports roads, which is why the Lötschberg Base Tunnel’s second track is only 1/3 complete.

Most European transit agencies have responded effectively to political precarity and budget crunches. They invest to minimize future operating expenses, and make long-term plans as far as political winds permit them to. American transit agencies don’t do any of this. They’re allergic to mainline rail electrification, sluggish about high platforms, indifferent to labor-saving signaling projects, hostile to accessibility upgrades unless sued, and uncreative about long-term operating expenses. They’re not precarious – they’re just incompetent.

Sorry Eno, the US Really Has a Construction Cost Premium

There’s a study by Eno looking at urban rail construction costs, comparing the US to Europe. When it came out last month I was asked to post about it, and after some Patreon polling in which other posts ranked ahead, here it goes. In short: the study has some interesting analysis of the American cost premium, but suffers from some shortcomings, particularly with the comprehensiveness of the non-American data. Moreover, while most of the analysis in the body of the study is solid, the executive summary-level analysis is incorrect. Streetsblog got a quote from Eno saying there is no US premium, and on a panel at Tri-State a week ago T4A’s Beth Osborne cited the same study to say that the US isn’t so bad by European standards, which is false, and does not follow from the analysis. The reality is that the American cost premium is real and large – larger than Eno thinks, and in particular much larger than the senior managers at Eno who have been feeding these false quotes to the press think.

What’s the study?

Like our research group at Marron, Eno is comparing American urban rail construction costs per kilometer with other projects around the world. Three key differences are notable:

- Eno looks at light rail and not just rapid transit. We have included a smattering of projects that are called light rail but are predominantly rapid transit, such as Stadtbahns, the Green Line Extension in Boston, and surface portions of some regional rail lines (e.g. in Turkey), but the vast majority of our database is full rapid transit, mostly underground and not elevated. This means that Eno has a mostly complete database for American urban rail, which is by construction length mostly light rail and not subways, whereas we have gaps in the United States.

- Eno only compares the United States with other Western countries, on the grounds that they are the most similar. There is a fair amount of Canada in their database, one Australian line, and a lot of Europe, but no high-income Asia at all. Nor do they look at developing countries, or even upper-middle-income ones like Turkey.

- Eno’s database in Europe is incomplete. In particular, it looks by country, including lines in Britain, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and France, but even there it has coverage gaps, and there is no Switzerland, little Scandinavia (in particular, no ongoing Stockholm subway expansion), and no Eastern Europe.

The analysis is similar to ours, i.e. they look at average costs per km controlling for how much of the line is underground. They include one additional unit of analysis that we don’t, which is station spacing; ex ante one expects closer station spacing to correlate with higher costs, since stations are a significant chunk of the cost and this is especially notable for very expensive projects.

The main finding in the Eno study is that the US has a significant cost premium over Europe and Canada. The key here is figure 5 on takeaway 4. All costs are in millions of PPP dollars per kilometer.

| Tunnel proportion | Median US cost | Median non-US cost |

| 0-20% | $56.5 | $43.8 |

| 20-80% | $194.4 | $120.7 |

| 80-100% | $380.6 | $177.9 |

However, the study lowballs the US premium in two distinct ways: poor regression use, and upward bias of non-US data.

Regression and costs

The quotes saying the US has no cost premium over Europe come from takeaways 2 and 3. Those are regression analyses comparing cost per km to the tunnel proportion (takeaway 3) or at-grade proportion (takeaway 2). There are two separate regression lines for each of the two takeaways, one looking at US projects and one at non-US ones. In both cases, the American regression line is well over the European-and-Canadian line for tunneled projects but the lines intersect roughly when the line goes to 0% underground. This leads to the conclusion that the US has no premium over Europe for light rail projects. Moreover, because the US has outliers in New York, the study concludes that there is no US premium outside New York. Unfortunately, these conclusions are both false.

The reason the regression lines intersect is that regression is a linear technique. The best fit line for the US construction cost per km relative to tunnel proportion has a y-intercept that is similar to the best fit line for Europe. However, visual inspection of the scattergram in takeaway 3 shows that at 0% underground, most US projects are somewhat more expensive than most European projects; this is confirmed in takeaway 4. All this means that the US has an unusually large premium for tunneled projects, driven by the fact that the highest-cost part of the US, New York, builds fully-underground subways and not els or light rail. If instead of Second Avenue Subway and the 7 extension New York had built high-cost els, for example the plans for a PATH extension to Newark Airport, then a regression line would show a large US premium for elevated projects but not so much for tunnels.

I tag this post “good/interesting studies” and not just “shoddy studies” because the inclusion of takeaway 4 makes this clear: there is a US premium for light rail, it’s just smaller than for subways, and then regression analysis can falsely make this premium disappear. This is an error, but an interesting one, and I urge people who use statistics and data science to study the difference between takeaways 2 and 3 and takeaway 4 carefully, to avoid making the same error in their own work.

Upward bias

Eno has a link to its dataset, from which one can see which projects are included. It’s notable that Eno is comprehensive within the United States, but not in Europe. Unfortunately, this introduces a bias into the data, because it’s easier to find information about expensive projects than about cheap ones. Big projects are covered in the media, especially if there are cost overruns to report. There is also a big-city premium because it’s more complicated to build line 14 of a metro system than to build line 1, and this likewise biases incomplete data because it’s easier to find what goes on in Paris than to find what goes on in a sleepy provincial town like Besançon. Yonah Freemark thankfully has good coverage of France and includes low-cost Besançon, but Eno does not – its French light rail database is heavy on Paris and has big gaps in the provinces. French Wikipedia in fact has a list, and all of the listed systems, which are provincial, have lower costs than Paris.

There is also no coverage of German tramways; we don’t have such coverage either, since there are many small projects and they’re in small cities like Bielefeld, but my understanding is that they are not very expensive. Traditionally German rail advocates held the cost of a tramway to be €10 million/km, which is clearly too low for the 2010s, but it should lower the median cost compared to the Paris-heavy, Britain-heavy Eno database.

Is Remote Work Viable?

No, not in the long run.

This has big implications for cities in the future, because it means firms will want to cluster more near production amenities – that is, other high-productivity firms. A city like New York manifestly has very weak consumption amenities, because in the spring it proved that its government is dangerously incompetent in a crisis – but its production amenities are likely to grow, because more firms will want to locate there and in other big, rich cities.

Remote work and the tech industry

The tech industry has long been familiar with remote work. The big multinationals have offices worldwide and some teams are remote, and some small firms are even all-remote. Much of this is an adaptation to the industry’s inability to bring everyone to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, where housing is too expensive and work visas are scarce. This has led to a big internal debate about the future of work; for decades now there have been predictions that the Internet would facilitate remote work and therefore reduce the need for cities to exist as office work centers.

The industry also reacted to corona slightly faster than the rest of the Western world. I’m not sure why – usually the American tech industry sneers at anything that comes out of Asia. But for whatever reason, Google sent its workers home in early March, and has been on work-from-home since, as have the other tech employers.

However, this was always intended to be a temporary arrangement. Workers were told to go back to the office when the crisis ended, at a date that keeps being pushed back and is now September 2021. Moreover, it appears that the industry wants to consolidate rather than disperse: Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple are all buying up office space in Manhattan, planning to add 22,000 jobs there. This is not San Francisco, but it’s the closest thing: New York is the United States’ second richest metropolitan region, and (I believe) the second biggest tech job center, with New York hosting the largest non-Bay Area Google office.

The problems with remote work

I have asked a number of people to talk to me about their experience with working from home. All are American professionals; this is far and away the easiest socioeconomic class to do an ethnography of. At no point did anyone ever tell me that everyone in their office is as productive working from home as they had been working as a team at the office. The work from home productivity loss is real; it does not affect everyone, but it affects enough people to be noticeable.

Specific problems I was told include,

- Corona specifically is a very stressful event, so everyone is on edge and less productive than the usual.

- Without continuous office work, it’s harder to onboard junior workers, even when senior workers are fine at home. Junior workers also lose the benefits of close mentoring.

- Parents with children have to take on additional care duties, and without a stay-at-home parent this is difficult.

- I believe in one case I was told the opposite of the above – that given that children are at home, it’s easier for parents than for non-parents.

- At least per the CEO of United, who is obviously biased on this, firms perceive in-person sales to be more successful than virtual ones. In general, I’ve been told that work facing clients is less productive when it’s virtual and law firms can work remotely in the short run with their existing client base but in the long run they need the office.

The standard production theory, articulated for example by Alain Bertaud, is that working from home is less productive because there are no spontaneous interactions, and this seems true although I don’t recall anyone telling me this exact thing literally, but very similar problems are apparent.

What does this mean for cities?

Before corona, it was not always clear whether advances in telecommunications would make remote work viable. It increasingly looks like the answer is no, and therefore the most productive firms are likely to center around their usual clusters, just as the tech firms are buying up Manhattan office space. The upshot, then, is that high-cost, high-productivity city centers are likely to see more commercial demand in the medium and long runs.

One model that I’ve heard from multiple sources is mixed, for example 2-4 days a week at the office, 1-3 days remote. If this happens, then it will mean that people commute fewer days. This has opposite effects on office and residential geography: fewer commutes mean it’s more acceptable to live farther out and have longer work trips on work-at-office days, which encourages either suburbanization or hopping over to the next city over; for the exact same reason, it’s also more acceptable to site offices in areas with more traffic congestion, that is city center.

What does this mean for public transportation?

More urban job concentration universally requires better public transportation, since rapid transit is far and away the most efficient mode of transportation measured in capacity provided per unit of right-of-way width. However, the details are subtle. Most importantly, the American upper middle class mostly does not work 9 to 5 at the most productive firms. The tech industry tends toward shifted hours, especially on the East Coast in order to overlap Silicon Valley better, and even for the same reason in Israel. So the impact of more tech employment in Midtown is not that New York desperately needs more subway capacity, but rather that it needs to broaden the peak to last until 10 in the morning rather than 9. This conclusion does not depend much on whether workers show up at the office every day or only 3-4 days a week, because 60-80% of rush hour traffic still requires peak or near-peak train throughput.

There were many Americans who, back when corona seemed to be first and foremost a New York problem, predicted the end of cities, or the conversion of cities to spaces of consumption. Joel Kotkin even blamed New York’s density for corona and praised Los Angeles’s sprawl; now that Los Angeles is running out of hospital beds, nobody in the US blames density anymore. (One could also point out Seoul and Tokyo’s density, but not even 460,000 deaths and counting will make Americans say “our country needs to be more like other countries.”)

But this is not looking to happen. The most productive firms in the US are urbanizing – and those are the most productive firms in the world; it averages out with horrific American public-sector inefficiency to about the same GDP per hour as in Germany. And this means that going forward, the richest, most productive, and most expensive cities will remain spaces of high-end production, and will need to build sufficient numbers of office towers and residences and improve public transportation infrastructure to accommodate.

Costs Matter: Some Examples

A bunch of Americans who should know better tell me that nobody really cares about construction costs – what matters is getting projects built. This post is dedicated to them; if you already believe that efficiency and social return on investment matter then you may find these examples interesting but you probably are not looking for the main argument.

Exhibit 1: North America

Vancouver

I wrote a post focusing on some North American West Coast examples 5 years ago, but costs have since run over and this matters from the point of view of building more in the future. In the 2000s and 10s, Vancouver had the lowest construction costs in North America. The cost estimate for the Broadway subway in the 2010s was C$250 million per kilometer, which is below world median; subsequently, after I wrote the original post, an overrun by a factor of about two was announced, in line with real increases in costs throughout Canada in the same period.

Metro Vancouver has always had to contend with small, finite amounts of money, especially with obligatory political waste. The Broadway subway serves the two largest non-CBD job centers in the region, the City Hall/Central Broadway area and the UBC, but in regional politics it is viewed as a Vancouver project that must be balanced with a suburban project, namely the lower-performing Surrey light rail. Thus, the amount of money that was ever made available was about in line with the original budget, which is currently only enough to build half the line. Owing to the geography of the West Side, half a line is a lot less than half as good as the full line, so Vancouver’s inability to control costs has led to worse public transportation investment.

Toronto

Like Vancouver, Toronto has gone from having pretty good cost control 20 years ago to having terrible cost control today. Toronto’s situation is in fact worse – its urban rail program today is a contender for the second most expensive per kilometer in the world, next to New York. The question of whether it beats Singapore, Hong Kong, London, Melbourne, Manila, Qatar, and Los Angeles depends on project details, essentially on scoring which of these is geologically and geographically the hardest to build in assuming competent leadership, which is in short supply in all of these cities. I am even tempted to specifically blame the most recent political interference for the rising costs, just as the adoption of design-build in the 2000s as an in-vogue reform must be blamed for the beginning of the cost blowouts.

The result is that Toronto is building less stuff. It’s been planning a U-shaped Downtown Relief Line for decades, since only the Yonge-University-Spadina (“YUS”) line serves downtown proper and is therefore overcrowded. However, it’s not really able to afford the full line, and hence it keeps downgrading it with various iterations, right now to an inverted L for the Ontario Line project.

Los Angeles

Los Angeles’s costs, uniquely in the United States, seemed reasonable 15 years ago, and no longer are. This, as in Canada, can be seen in building less stuff. High-ranking officials at Los Angeles Metro explained to me and Eric that the money for capital expansion is bound by formulas decided by referendum; there is a schedule for how to spend the money as far as 2060, which means that anything that is not in the current plan is not planned to be built in the next 40 years. Shifting priorities is not really possible, not with how Metro has to buy off every regional interest group to ensure the tax increases win referendums by the required 2/3 supermajority. And even then, the taxes imposed are rising to become a noticeable fraction of consumer spending – even if California went to majority vote, its tax capacity would remain very finite.

New York

The history of Second Avenue Subway screams “we would have built more had costs been lower.” People with deeper historic grounding than I do have written at length about the problems of the Independent Subway System (“IND”) built in the 1920s and 30s; in short, construction costs were in today’s terms around $140 million per km, which at the time was a lot (London and Paris were building subways for $30-35 million/km), and this doomed the Second System. But the same impact of high costs, scaled to the modern economy, is seen for the current SAS project.

The history of SAS is that it was planned as a single system from 125th Street to Hanover Square. The politician most responsible for funding it, Sheldon Silver, represented the Lower East Side. But spending capacity was limited, and in particular Silver had to trade that horse for East Side Access serving Long Island, which was Governor George Pataki’s base. The package was such that SAS could only get a few billion dollars, whereas at the time the cost estimate for the entire 13-km line was $17 billion. That’s why SAS was chopped into four phases, starting on the Upper East Side. Silver himself signed off on this in the early 2000s even though his district would only be served in phase four: he and the MTA assumed that there would be further statewide infrastructure packages and the entire line would be complete by 2020.

Exhibit 2: Israel

Israel is discussing extending the Tel Aviv Metro. It sounds weird to speak of extensions when the first line is yet to open, but that line, the Red Line, is under construction and close enough to the end that people are believing it will happen; Israelis’ faith that there would ever be a subway in Tel Aviv was until recently comparable to New Yorkers’ faith until the early 2010s that Second Avenue Subway would ever open. The Red Line is a subway-surface Stadtbahn, as is the under-construction Green Line and the planned Purple Line. But metropolitan Tel Aviv keeps growing and is at this point an economic conurbation of about 3-4 million people, with a contiguous urban core of 1.5 million. It needs more. Hence, people keep discussing additions. The Ministry of Finance, having soured on the Stadtbahn idea, bypassed the Ministry of Transport and introduced a complementary three-line underground driverless metro system.

The cost of the system is estimated at 130-150 billion shekels, which is around $39 billion. This is not a sum Israelis are used to seeing for a government project. It’s about two years’ worth of IDF spending, and Israeli is a militarized society. It’s about 10% of annual GDP, which in American or EU-wide terms would be $2 trillion. The state has many competing budget priorities, and there are so many other valid claims on the state coffers. It is therefore likely that the metro project’s construction will stretch over many years, not out of planning latency but out of real resource limits. People in Israel understand that Gush Dan has severe traffic congestion and needs better transportation – this is not a point of political controversy in a society that has many. But this means the public is willing to spend this amount of money over 15-20 years at the shortest. Were costs to double, in line with the costs in most of th Anglosphere, it would take twice as long; were they to fall in half, in line with Mediterranean Europe, it would take half as long.

Exhibit 3: Spain

As the country with the world’s lowest construction costs for infrastructure, Spain builds a lot of it, everywhere. This includes places where nobody else would think to build a metro tunnel or an airport or a high-speed rail line; Spain has the world’s second longest high-speed rail network, behind China. Many of these lines probably don’t even make sense within a Spanish context – RENFE at best operationally breaks even, and the airports were often white elephants built at the peak of the Spanish bubble before the 2008 financial crisis.

One can see this in urban rail length just as in high-speed rail. Madrid Metro is 293 km long, the third longest in Europe behind London and Moscow. This is the result of aggressive expansion in the 1990s and 2000s; new readers are invited to read Manuel Melis Maynar’s writeup of how when he was Madrid Metro’s CEO he built tunnels so cheaply. Expansion slowed down dramatically after the financial crisis, but is starting up again; the Spanish economy is not good, but when one can build subways for €100 million per kilometer, one can build subways that other cities would not. In addition to regular metros, Madrid also has regional rail tunnels – two of them in operation, going north-south, with a third under construction going east-west and a separate mainline rail tunnel for cross-city high-speed rail.

Exhibit 4: Japan

Japan practices economic austerity. It wants to privatize Tokyo Metro, and to get the best price, it needs to keep debt service low. When the Fukutoshin Line opened in 2008, Tokyo Metro said it would be the system’s last line, to limit depreciation and interest costs. The line amounted to around $280 million/km in today’s money, but Tokyo Metro warned that the next line would have to cost $500 million/km, which was too high. The rule in Japan has recently been that the state will fund a subway if it is profitable enough to pay back construction costs within 30 years.

Now, as a matter of politics, on can and should point out that a 30-year payback, or 3.3% annual interest, is ridiculously high. For one, Japan’s natural interest rate is far lower, and corporations borrow at a fraction of that interest; JR Central is expecting to be paying down Chuo Shinkansen debt until the 2090s, for a project that is slated to open in full in the 2040s. However, if the state changes its rule to something else, say 1% interest, all that will change is the frontier of what it will fund; lines will continue to be built up to a budgetary limit, so that the lower the construction costs, the more stuff can be built.

Conclusion: the frontier of construction

In a functioning state, infrastructure is built as it becomes cost-effective based on economic growth, demographic projections, public need, and advances in technology. There can be political or cultural influences on the decisionmaking process, but they don’t lead to huge swings. What this means is that as time goes by, more infrastructure becomes viable – and infrastructure is generally built shortly after it becomes economically beneficial, so that it looks right on the edge of viability.

This is why megaprojects are so controversial. Taiwan High-Speed Rail and Korea Train Express are both very strong systems nowadays. Total KTX ridership stood at 89 million in 2019 and was rising on the eve of corona, thanks to Korea’s ability to build more and more lines, for example the $69 million/km, 82% underground SRT reverse-branch. THSR, which has financial data on Wikipedia, has 67 million annual riders and is financially profitable, returning about 4% on capital after depreciation, before interest. But when KTX and THSR opened, they both came far below ridership projections, which were made in the 1990s when they had much faster economic convergence before the 1997 crisis. They were viewed as white elephants, and THSR could not pay interest and had to refinance at a lower rate. Taiwan and South Korea could have waited 15 years and only opened HSR now that they have almost fully converged to first-world Western incomes. But why would they? In the 2000s, HSR in both countries was a positive value proposition; why skip on 15 years of good infrastructure just because it was controversially good then and only uncontroversially good now?

In a functioning state, there is always a frontier of technology. The more cost-effective construction is, the further away the frontier is and the more infrastructure can be built. It’s likely that a Japan that can build subways for Korean costs is a Japan that keeps expanding the Tokyo rail network, because Japan is not incompetent, just austerian and somewhat high-cost. The way one gets more stuff built is by ensuring costs look like those of Spain and Korea and not like those of Japan and Israel, let alone those of the United States and Canada.

What Suburban Poverty?

Myth: American cities have undergone inversion, in which poorer people are more suburban than richer people.

Reality: at least on the level of people commuting to city center, wages generally rise with commute distance. In particular, the phenomenon of supercommuters – people traveling very long distances to work – is a middle- and high-income experience more than a low-income one. This is true even in Los Angeles, a Sunbelt city with more of a drive-until-you-qualify history than the Northeastern cities. The only exception among the largest US cities is San Francisco, and there too, the poorest distance is 5-10 km out of the Financial District.

All data in this post comes from OnTheMap and is as of 2017, the latest year for which there is data. The methodology is to define a central business district, generally a looser one than in past post but still much smaller than the entirety of the city, and look at people who work in it and live within annuli of increasing radius from a specific central point within the CBD. OnTheMap puts jobs into three income buckets, the boundary points being $1,250 and $3,333 per month; we look at the proportion of jobs in the highest category.

I report the annuli in kilometers, but technically they’re in multiples of 3.11 miles, which is very close to 5 km.

| City | New York | Los Angeles | Chicago | Washington | San Francisco | Boston |

| CBD | 3rd, 60th, 9th, 30th | I-10, I-110, river | Congress, I-90, Grand | 6th, R, river, E | Broadway, Van Ness, 101, 16th | I-90, water, Arlington |

| Point | Grand Central | 7th/Metro Center | State/Madison | Farragut | Market/2nd | Downtown Crossing |

| Jobs | 1,017,175 | 310,111 | 558,379 | 249,707 | 441,104 | 241,775 |

| 40k+ % | 68.7% | 68.8% | 70.4% | 69.8% | 73.2% | 71.7% |

| 0-5 km | 211,910 | 22,557 | 67,348 | 56,578 | 86,845 | 41,912 |

| 40k+ % | 79.8% | 44.6% | 84% | 75.1% | 76.6% | 70.5% |

| 5-10 km | 205,215 | 38,986 | 91,332 | 56,154 | 67,063 | 52,499 |

| 40k+ % | 63.6% | 53.2% | 70.1% | 61.5% | 68.3% | 64.3% |

| 10-15 km | 172,117 | 42,391 | 88,604 | 38,233 | 49,111 | 30,619 |

| 40k+ % | 51.9% | 65.1% | 58.8% | 66.2% | 73.6% | 73.3% |

| 15-20 km | 101,543 | 41,229 | 67,620 | 23,589 | 35,692 | 20,444 |

| 40k+ % | 62% | 71.3% | 67.3% | 69.8% | 74.5% | 76.8% |

| 20-30 km | 92,871 | 53,809 | 68,571 | 27,921 | 40,170 | 29,271 |

| 40k+ % | 74.4% | 75.6% | 73.5% | 75.8% | 76.9% | 79% |

| 30-40 km | 61,236 | 33,051 | 49,374 | 15,568 | 33,395 | 17,511 |

| 40k+ % | 81.1% | 77.6% | 76.1% | 78% | 80.1% | 77.8% |

| 40-50 km | 37,931 | 17,561 | 41,745 | 8,403 | 20,509 | 12,738 |

| 40k+ % | 82.1% | 81% | 78.7% | 82% | 82.4% | 78.7% |

| 50-60 km | 26,746 | 13,853 | 25,872 | 3,346 | 15,981 | 9,321 |

| 40k+ % | 81.3% | 82.3% | 74.9% | 76.7% | 78.7% | 76.9% |

| 60-70 km | 21,860 | 8,561 | 14,940 | 2,596 | 14,682 | 6,101 |

| 40k+ % | 80.3% | 83.6% | 74.5% | 76.9% | 73.3% | 71.5% |

| 70-80 km | 14,007 | 7,720 | 5,471 | 1,444 | 9,151 | 4,757 |

| 40k+ % | 77.8% | 79.7% | 72.4% | 79.3% | 69.8% | 74.2% |

In all six metro areas above except Los Angeles, the income in the innermost 5-km circle is higher than in the 5-10 km annulus. In Chicago that inner radius is in fact the wealthiest, but in Boston it’s below average, and in New York, Washington, and San Francisco it is poorer than wide swaths of suburbia. There is always a large region of poverty in an urban radius, which is roughly the inner 15 km in Los Angeles, the 5-20 km annulus in New York, the 10-15 km radius in Chicago, and so on.

This of course does not take directionality into account. In Chicago, it is especially important – to the north, there is wealth at all radii, and to the south, there is mostly poverty. In contrast, in New York directionality is less important, and it is in a way the purest example of the poverty donut model, in which the center is rich, the suburbs are rich, and the in-between neighborhoods are poor, without wedges that form favored quarters or wedges that form ill-favored quarters.

The importance of this is that because the inner and outer limits of the poverty donut are slowly moving outward, there is talk of suburbanization of poverty – or, rather, there was in the decade leading up to corona, but I suspect it will return once mass vaccination happens. However, even now, American cities are not Paris or Stockholm, where wealth mostly decreases as distance from the center increases, even though both cities have intense directionality (rich northeast, poor south and west in Stockholm, and the exact opposite in Paris). The poorest place remains the inner city, just beyond the near-downtown zone at what I would call biking range from city center jobs if any American city had even semi-decent biking infrastructure.

This contrasts with various schemes to subsidize suburbs that assume poverty has already suburbanized. Massachusetts, where even in the inner 5 km radius the $40,000+ share is below average, has a concept called Gateway Cities, defined to mean roughly “low- and lower-middle-income cities that aren’t Boston.” Of those, about one, Chelsea, is inner-urban, while the others include Springfield and various ex-industrial cities that are generally no poorer than Boston and lie amidst suburban wealth, like Lowell and Haverhill. Based on the idea that Massachusetts poverty is in the Gateway Cities and not in Boston itself, it justifies vast place-based subsidies that mostly go to people who are decently well-off while Dorchester has to beg for slightly better public transportation to Downtown Boston.

In New York, one likewise hears more about the poverty of Far Rockaway than about that of Harlem. There’s this widespread belief that Harlem is no longer poor, that it’s fully gentrified because there’s one bagel shop on 116th Street that caters to a mostly white middle-class clientele. This is related to the stereotype of the Real New Yorker, weaponized so that the cop or the construction worker who is a third-generation New Yorker and lives at the outermost edge of the city is an inherently more moral person than the Manhattanite or the immigrant and is the very definition of the working class while earning $90,000 a year. This goes double if this Real New Yorker lives on Long Island, usually with some catechism about how the city is too expensive even though the suburbs are about equally costly. The one place-based policy that would benefit the city, having the state integrate its schools with those of the generally better-resourced suburbs, is unthinkable.