Category: New York

The Danbury Branch and Rail Modernization

I’ve been asked to talk about how rail modernization programs, like the high-speed rail plan we published at Marron this month, affect the Danbury Branch of the New Haven Line. The proposal barely talks about branch modernization beyond saying that the branches should be electrified; we didn’t have time to write precise branch timetables, which means that the timetable I’m going to post here is going to have more rounding artifacts. The good news is that modernization can be done cheaply, piggybacking on required work on the main of the New Haven Line.

Current conditions

The Danbury Branch is a 38 km single-track unelectrified line, connecting South Norwalk with Danbury making six additional intermediate stops. All stations have high platforms, but they are short, ranging between three and six cars.

Ridership is essentially unidirectional: toward Norwalk and New York in the morning, back north in the afternoon. There is little job concentration near the stations. Within 1 km of Danbury there are only 5,000 jobs per OnTheMap, rising to 10,000 if we include Danbury Hospital, which is barely outside the station’s 1 km radius (but is not easily walkable from it). Merritt 7 is in an office park, but there are only 6,000 jobs there, and nearly everyone drives. The other stations are parking lots, and Bethel is somewhat outside the town center for better parking.

The right-of-way is very curvy, much more so than the main line. Where most of the New Haven Line is built to a standard of 2° curves (radius 873 m), permitting 157 km/h with modern cant and cant deficiency, the Danbury Branch scarcely has a section straight enough with gentler curves than 3°, and much of it has such frequent 4° curves that trains cannot go faster than 100 km/h except for speedups of a few seconds at a time to recover delays.

A first pass on infrastructure and operations

It is effectively free to electrify a 38 km single-track line. The high-speed rail report estimates it at $75 million based on both European electrification costs (see report for sources) and the Southern Transcon proposal, which is $2 million/km on a busy double-track line. The junction between the branch and the main line is flat, but outbound trains can be timetabled to avoid conflict, and inbound trains have no at-grade conflict to begin with. If platform lengthening is desired, then it is a noticeable extra expense; figure $30 million for each eight-car platform, or perhaps half that on single track (but then some stops are double-track), maybe with some pro-rating for existing platforms if they can be easily reused.

The tracks should also be maintained to higher speed, which is a routine application of a track laying machine, with some weekend closures for construction followed by what should be an uninterrupted multidecade period of operations. The curves are already superelevated to a maximum of 5-6″; this is less than the 7″ maximum in US law (180 mm here), but the difference is not massive. The line has a 50 mph speed limit today for the most part, whereas it can be boosted to about 100-110 km/h depending on section, a smaller difference than taking the main line’s 70 mph and turning it into 150-160 km/h.

With a blanket speed limit of 110 km/h – in truth some sections need to dip down to 100 or even less whereas the Bethel-Danbury and Merritt 7-Wilton interstations can be done mostly at 130 – the trip time between South Norwalk and Danbury is, inclusive of 7% pad, 28.75 minutes. The Northeast Corridor report timetables have express New Haven Line commuter trains arriving South Norwalk southbound at :15.25 every 20 minutes and departing northbound at :14.75, so they’d be departing Danbury at :46.5 and arriving :43.5. Meets would occur at the :20, :30, and :40 points.

The :30 point, important as it is a meet even if service is reduced to every 30 minutes, is just south of Branchville, likely too far to use the existing meet at the station. Thus, at first pass, some additional double-tracking is needed, a total of 6 km if it covers the entire Cannondale-Branchville interstation, which would cost around $50 million at MBTA Franklin Line costs. MBTA Franklin Line costs are likely an underestimate, since the terrain on the Cannondale-Branchville interstation is hillier and some additional earthworks would be required on part of the section. A high-end estimate should be the cost of a high-speed rail line without elevated or tunneled segments, around $30 million/km or even less (cut-and-fill isn’t needed as much when the line curves with the topography), say $150 million.

The :20 point southbound is at or just south of Bethel. While this is in a built-up area, the right-of-way looks wide enough for two tracks and the topography is easier; if the station is the meet, then the cost is effectively zero, bundled into a platform lengthening project. Potentially, this could even be further bundled with moving the station slightly south to be closer to the town center. The :40 point southbound is at Merritt 7, which has room for a second track but not necessarily for a platform at it, and could instead get a second track on the opposite side of the platform if there’s enough of a rebuild to turn it into an island with additional vertical circulation; the cost of the second track itself would be a rounding error but the cost of station reconstruction would not be and would likely be in the mid-tens of millions.

How this fits into the broader system

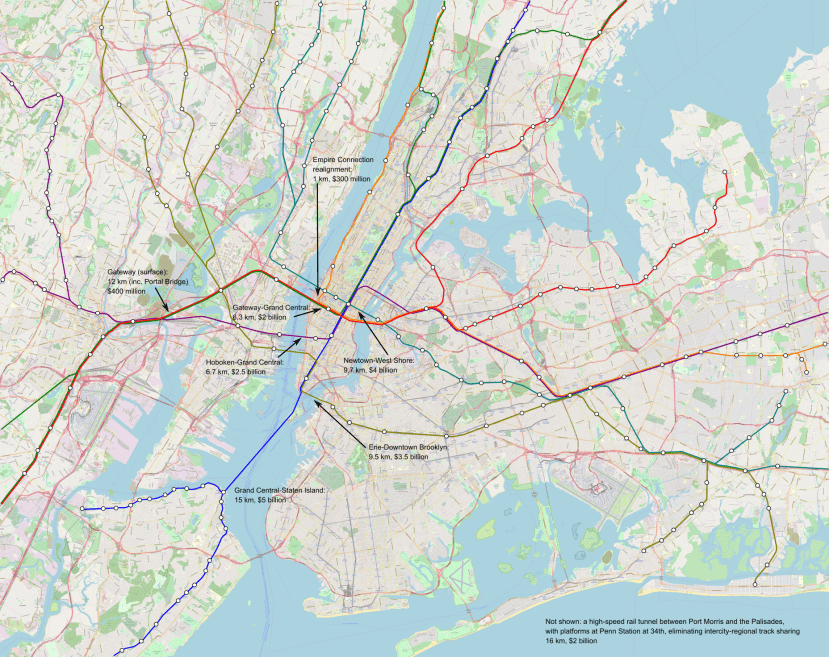

The timetable in the report already assumes that New Haven Line service comprises 6 peak trains per hour (tph) that use the branches. The default assumption, reproduced in the service network graphic, is that New Canaan and Danbury get 3 tph each, and New Canaan gets a grade-separated junction but Danbury does not. Those trains all go to Grand Central with no through-running: only the local trains on the New Haven Line get to run through, since local trains are the highest priority for through-running. If a tunnel connecting the Gateway tunnel with Grand Central is opened, as in some long-term plans (here’s ETA’s, which isn’t very different from past blog posts’), then they can run through to it.

The establishment of this service is not going to, by itself, change the characteristic of ridership on the line. Electrification, better timetabling, and better rolling stock (in this order) can reduce the trip time from an hour today to 29 minutes, and the trip time to Grand Central from about 2:25 to 1:09, but the main effect would be to greatly improve the connectivity of existing users, who’d be driving to the parking lot stations more often, perhaps working from the office more and from home less, or taking the train to social events in the city. Some would opt to use the train to get to work at Stamford, as a secondary market. Over time, I expect that people would buy in the area to commute to work in New York (or at Stamford), but housing permit rates in Fairfield County are low and only limited TOD is likely. It would take concerted commercial TOD at the stations to produce reverse-peak ridership, likely starting with expanding the Merritt 7 office park and making it a bit less auto-oriented.

If the ridership isn’t there, then a train every 20 minutes is not warranted and only a train every 30 minutes should be provided. This reduces the double-track infrastructure requirement but only marginally, as the meets that are no longer needed are the easy ones and the one that still is is the hard one to build, south of Branchville. In effect, something like 80% of the cost provides two thirds of the capacity; this is common to rail projects, in that small cuts in an already optimized budget lead to much larger cuts in benefits, the opposite of what one hopes to achieve when optimizing cuts.

The Problems of not Killing Penn Expansion and of Tariffs

Penn Station Expansion is a useless project. This is not news; the idea was suspicious from the start, and since then we’ve done layers of simulation, most recently of train-platform-mezzanine passenger flow. However, what is news is that the Trump administration is aiming to take over Penn Reconstruction (a separate, also bad project) from the MTA, in what looks like the usual agency turf battles, except now given a partisan spin. I doubt there’s going to be any money for Reconstruction (budgeted at $7 billion), let alone expansion (budgeted at $17 billion), and overall this looks like the usual promises that nobody intends to act upon. The problem is that this project is still lurking in the background, waiting for someone insane enough to say what not a lot of people think but few are willing to openly disagree with and find some new source of money to redirect there. And oddly, this makes me think of tariffs.

The commonality is that free trade is not just good, but is more or less an unmixed blessing. In public transport rolling stock procurement, the costs of tariffs are so high that a single job created in the 2010s cost $1 million over 4-6 years, paying $20/hour. In infrastructure, in theory most costs are local and so it shouldn’t matter, but in practice some materials need to be imported, and when they run into trade barriers, they mess entire construction schedules. Boston’s ability to upgrade commuter rail stations with high platform was completely lost due to successive tightening of the Buy America waiver process under Trump and then Biden, to the point that even materials that were just not made in America (steel, FRP) could not be imported. The problem is that nobody was willing to say this out loud, and instead politicians chose to interfere with bids to get some photo-ops, getting trains that are overpriced and fail to meet schedule and quality standards.

Thus, the American turn away from free trade, starting with Trump’s 2016 campaign. During the Obama-Trump transition, the FTA stopped processing Buy America waivers, as a kind of preemptive obedience to something that was never written into the law, which includes several grounds for waivers. During the Trump-Biden transition, the standards were tightened, and waivers required the approval of a political office at the White House, which practiced a hostile environment, hence the above example of the MBTA’s platform problems. Now there are general tariffs, at a rate that changes frequently with little justification. The entire saga, especially in the transit industry, is a textbook example not just of comparative advantage, but of the point John Williamson made in the original Washington Consensus that trade barriers were a net negative to the country that imposes them even if there’s no retaliation, purely from the negative effects on transparency and government cleanliness. This occurred even though tariffs were not favored in the political elite of the United States, or even in the general public; but nobody would speak out except special interests and populists who favored trade barriers.

And Penn Expansion looks the same. It’s an Amtrak turf game, which NJ Transit and the MTA are indifferent to. NJ Transit’s investment plan is not bad and focuses on actual track-level improvements on the surface. The MTA has a lot of problems, including the desire for Penn Reconstruction, but Penn Expansion is not among them. The sentiments I’m getting when I talk to people in that milieu is that nobody really thinks it’s going to happen, and as a result most people don’t think it’s important to shoot down what is still a priority for Amtrak managers who don’t know any better.

The problem is that when the explicit argument isn’t made, the political system gets the message that Penn Expansion is not necessarily bad, but now is not the time for it. It will not invest in alternatives. (On tariffs, the alternative is to repeal Buy America.) It will not cancel the ongoing design work, but merely prolong it by demanding more studies, more possibilities for adding new tracks (seven? 12? Any number in between?). It will insist that any bounty of money it gets go toward more incremental work on this project, and not on actually useful alternatives for what to do with $17 billion.

This can go on for a while until some colossally incompetent populist of the type that can get elected mayor or governor in New York, or perhaps president, decides to make it a priority. Then it can happen, and $17 billion plus future escalation would be completely wasted, and further investment in the system would suffer because everyone would plainly see that $17 billion buys next to nothing in New York so what’s the point in spending a mere $300 million here and there on a surface junction? If it were important then Amtrak would have prioritized that, no? Even people who get on some level that the agencies are bad with money will believe them on technical matters like scheduling and cost estimation over outsiders, in the same manner that LIRR riders think the LIRR is incompetent and also has nothing to learn from outsiders.

The way forward is to be more formal about throwing away bad ideas. Does Penn Expansion have any transportation value? No. So cancel it. Drop it from the list of Northeast Corridor projects, cancel all further design work, and spend about 5 orders of magnitude less money on timetabling trains at Penn Station within its existing footprint. Don’t let it lurk in the background until someone stupid enough decides to fund it; New York is rather good lately at finding stupid people and elevating them to positions of power. And learn to make affirmative arguments for this rather than the usual “it will just never happen” handwringing.

New York Mayoral Race Thrown Wide Open as Cuomo is Prosecuted, Adams Removed

The June 24th Democratic primary for mayor of New York City has been thrown wide open as both the incumbent mayor Eric Adams and the frontrunner, former governor Andrew Cuomo, have been dealt serious blows. State prosecutors announced an indictment of Cuomo on multiple charges including sexual assault and corruption stemming from his response to the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. Shortly after the indictments were handed, Governor Kathy Hochul announced that in light of the corruption charges against the mayor, she would exercise her gubernatorial prereogative to suspend him for 30 days, and unless new exculpatory evidence came to light would remove him subsequently. The winner of the June primary, she said, will then be appointed as interim mayor until an election can be held.

The governor’s power to remove local officials, including mayors, has not been used since 1932, when governor and president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt removed New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker following a corruption trial in which he served as prosecutor, judge, and jury. However, it remains part of the state constitution, and is not limited by the judiciary. Political operatives speculate that Hochul refrained from using this power against Adams partly because it had been so rarely used in the past but also partly to avoid empowering the wrong figures. With the new indictments against the former governor, it is speculated that the removal of Adams is intended to send a message to Cuomo that he’s a target as well should he become mayor.

Political figures in the city who have endorsed Cuomo in the primary express shock. A federally elected Democrat says that with Cuomo gone, there is a real risk of the anti-Israel Zohran Mamdani winning, and moderates and liberals should unite around a pro-Israel candidate, who the source did not yet name. The Brooklyn Democratic Party organization released a statement attacking Hochul for interfering with the election and saying that Cuomo’s handling of the pandemic was exemplary.

The remaining candidates in the primary who have made statements by the time this article has gone to press all reacted positively but reservedly. The two who have been running the deepest in the recent polls are Mamdani and City Comptroller Brad Lander, and who have so far refrained from responding to the shifting situation by attacking each other, both focusing on saying that Cuomo and Adams are not appropriate for leading New York.

Quick Note: Report on Electrification and Medium-Speed Rail Upgrades

Nolan Hicks has wrapped up nearly a year of work at Marron on a proposal called Momentum, to upgrade mainline rail in the United States with electrification, high platforms, and additional tracks where needed, short of high-speed rail. The aim is to build low- or perhaps medium-speed rail; the proposed trip times are New York-Albany in 2:05 (averaging 109 km/h) and New York-Buffalo in 5:38 to 5:46 (averaging 123 km/h). The concept is supposed to be used US-wide, but the greatest focus is on New York State, where the plan devotes a section to Network West, that is New York-Buffalo, and another to Network East, that is the LIRR, in anticipation of the upcoming state budget debate.

The costs of this plan are high. Nolan projects $33-35.6 billion for New York-Buffalo, entirely on existing track. The reasoning is that his cost estimation is based on looking at comparable American projects, and there aren’t a lot of such upgrades in the US, so he’s forced to use the few that do exist. A second track on single-track line is costed cheaply with references to various existing projects (in Michigan, Massachusetts, etc.), but third and fourth tracks on a double-track line like the Water Level Route are costed at $30 million/km, based on a proposal in the built-up area of Chicago to Michigan City.

In effect, the benefits are a good way of seeing what upgrades to best American industry practices would do. The idea, as with the costing, is to justify everything with current or past American plans, and the sections on the history of studies looking at electrification projects are indispensable. This covers both intercity and regional rail upgrades, and we’ve used some of the numbers in the drafts at ETA to argue, as Nolan does, against third rail extensions and in favor of catenary on the LIRR and Metro-North.

(Update 4-3: and now the full proposal is out, see here.)

Open BRT

BRT, or bus rapid transit, can be done in one of two ways: closed and open. Closed systems imitate rail lines, in that there is a BRT route along the entire length of the corridor; open ones instead take a trunk route, upgrade it with dedicated lanes and other BRT features, and let routes run through from it to branches that are not so equipped, perhaps because there is less traffic on the branches. I complained 14 years ago that New York City Transit was planning closed BRT in the form of SBS on Hylan Boulevard on Staten Island, a good route for open BRT. Well, now the MTA is planning BRT on the disused North Shore Branch of the Staten Island Railway, arguing that it is better than reactivating rail service because buses could use it as an open corridor – except that this is a poor corridor for open BRT. This leads to the question: which corridors are good for open BRT to begin with?

Trunks and branches are good

Open BRT can be analogized to a Stadtbahn system, fast in the core and slow outside it. Like a Stadtbahn, it works best where several branches can converge onto a single route, where the high traffic both requires higher capacity and justifies higher investment; just as grade separation increases the throughput of a rail line, BRT treatments increase those of a bus through greater separation from other traffic and regularity of service.

Unlike a Stadtbahn, open BRT remains a bus. This means two things:

- The trunk route must itself be a strong surface route. It had better be a wide street with room for physically separated bus lanes, or else a city center route that could be turned into a transit mall. A Stadtbahn system puts the fast central portion underground and could do it independently of the street network, or even run under a slow narrow street like Tremont Street in Boston.

- The connections from the trunk route to the branches must themselves be strong bus links. If the bus needs to zigzag on narrow residential streets to get between two wider arterials, then it will be unreliable and slow even if one of the wider arterials gets dedicated lanes. A Stadtbahn system can tunnel a few hundred meters here and there to ensure the onramps are adequate, but a surface bus system cannot, not without driving its cost structure to that of a subway but with few of the benefits of underground running.

The North Shore Branch could pass a modified version of criterion 1, but fails criterion 2. In general, former rail lines are bad for such BRT systems, since the street network was never set up for such connections. In contrast, street networks with a central artery and streets of intermediate importance between it and residential side streets emanating from it, which were never used for grade-separated rail lines, are more ideal for this treatment.

Grids are bad

Street grids eliminate the branch hierarchy of traditional street networks. There is still a hierarchy of more and less important grid streets – in Manhattan, the avenues and two-way streets are wider and more used for traffic than the one-way streets – but there is little branching. Bus networks can still branch if they move between streets, which happens in Manhattan, but it’s not usually a good idea: Barcelona’s Nova Xarxa uses the grid to run mostly independent bus routes, each route mostly sticking to a grid arterial, and the extent of branching on the Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx bus networks is limited to a handful of short segments like the Washington Bridge.

In situations like this, open BRT would not work. Hylan is possibly the only route in New York that has any business running open BRT. For this reason, our Brooklyn bus redesign proposal, and any work we could do for Queens, Manhattan, or the Bronx, eschews the open BRT concept. The buses are upgraded systemwide, since features like off-board fare collection and wider stop spacing are not really special BRT features but are rather normal in, for example, the urban German-speaking world. Center bus lanes are provided wherever there is need and room. There is more identification of a bus route with the street it runs on, but it isn’t really closed BRT, which is a series of treatments giving the BRT routes dedicated fleets and stations, for example with left-side doors to board from metro-style island platforms like Transmilenio.

What this means more broadly is that the open BRT is not a good fit for most of North America, with its grid routes. Occasionally, a diagonal street could act as a trunk if available, but this is uncommon. Broadway is famous for running diagonally to the Manhattan grid, but that’s not a BRT route but a subway route.

Public Transportation and Crime are not About Each Other

Noah Smith is trying to make public transportation and YIMBYism about crime, and I don’t think he succeeds. In short, he says that transit cities and higher housing growth levels would be more publicly acceptable if American central cities were more sensitive to conservative concerns about crime. In effect, he is making public transportation investment not a matter of frequency or network design or reliability or good maintenance or transit priority on streets or low construction costs or any of the other technocratic issues that distinguish the Seouls and Zurichs and Stockholms of the world from the Los Angeleses (which, to give credit, he acknowledges are important), but about crime, conceived as a culture war issue about more police and more police visibility. And in this, he ends up ignoring both the literature on this and what makes good government tick in parts of the developed world that are not the United States.

Now, Noah is a pundit, who’s more pro-transit than the average in his milieu. He’s not the reason American cities are poorly governed or the separate suite of reasons American public transit is so bad and isn’t improving. He writes as a way of trying to engage conservative NIMBYs, I just don’t think he succeeds – and the way he fails is for many of the same reasons American public transit managers fails. Chief of those is American triumphalism, of the kind that will retweet a viral tweet that pretends Europe has no biotech or advanced physics and that uses the expression “europoor” unironically in a flamewar. People who fail to recognize how Europe and East Asia work are not going to be able to learn what works here and how to adapt it; I’m less familiar with Asian discourse, but Noah’s description of Europe is unrecognizable. Even the basic thesis about urbanism and crime isn’t correct in a global perspective. This leads to serious problems in diagnosing how European cities got to have the housing and transportation policies that they do; the solutions are, by the black-and-white polarization of American politics, best thought of as a blue-and-orange spectrum, starting with lack of local empowerment and inattention to neighborhood-scale stereotypes

Cities and crime

The American association between high crime rates and deurbanization is not at all normal. Globally, it’s the exact opposite; Gaviria-Goldwyn-Galarza-Angel find that high risk of violence leads to higher urban density, because of the effect of safety in numbers. Simon Gaviria roots this in the history of his own country, Colombia. In Latin America, crime rates are infamously high. Noah’s post compares the American homicide rate with a selection of European and Asian countries, topping at 6.8/100,000 in Russia (US: 5.8), but in Colombia it is 25.7, and in the 1990s it ranged between 60 and 85. People can’t suburbanize the way they have in the United States, even with a GDP per capita in line with that of midcentury America, because, in a sufficiently high-crime environment, driving to work means taking the risk of being carjacked at an intersection.

Now, public transportation in Latin America is not especially good, not by European or East Asian standards. Most cities haven’t built much recently; Mexico City deserves especial demerits, but Brazil has been flagging as well, and Argentina has no money for anything. Chile and the Dominican Republic are both expanding metros, Santiago doing so rather rapidly, and both have the same order of magnitude of homicide as the US (Chile: 4.5, Dominican Republic: 11.5), rather than that of Colombia or Brazil or Mexico. But this still does not make high crime a relevant factor in deurbanization.

Now, in the history of the United States, people do associate postwar suburbanization with high crime rates. While the crime rate rose rapidly in the 1960s, and remained high until the 1990s, there was little transportation risk. The stereotype of poverty-induced social disorder as seen from a car in an American city, at least in the 1990s and 2000s, was a panhandler coming to the car at a traffic jam with a squeegee, washing it, and expecting payment; jacking was (and still is) more or less unheard of. The stereotype was, safety on the road and in the suburbs, danger in the city. But that is a feature of relatively moderate crime rates. Indeed, the destruction of American public transit in the middle of the 20th century and the suburbanization of the middle class and aspirants both came before the increase in crime rates; two thirds of the fall in New York subway ridership from its twin peaks in 1930 and 1946 to its nadir in 1982 had occurred by 1960, on the eve of the explosion in the city’s homicide rate.

And to be clear, this is a matter of stereotypes, more than reality. New York is one of the safest large cities in the United States (4.7/100,000 in 2023). San Francisco is even safer: in 2024 through December 10th, the pro-rated homicide rate was 4.3. Texan urbanists outside Austin (4.7) have to contend with higher homicide rates: 15.7 in Dallas, 12.8 in Houston, 8.4 in San Antonio, all averaged over the first six months of 2024 and pro-rated. But Dallas and Houston are perceived as far safer than New York. This can’t exactly be racism – these two cities are nearly as black as New York and considerably more Hispanic. But whatever is causing the stereotype needs to be separated from the reality; the Texan rail advocates I talk to on social media don’t treat crime as a major obstacle for finding more money for public transit, and instead cite car culture, low perceived value of rail, and high costs, and if that’s not a problem there, it shouldn’t be in New York or San Francisco.

Stereotypes in Paris

Noah talks about how Europe succeeded in curbing crime rates – and to again give credit, recognizes that New York is safe – and says that this is driving greater acceptance of public transportation and housing growth here.

Except, this isn’t quite right. I don’t have comparable surveys asking people if they find Paris safe, but I do have access to French discourse at hand, and it does not at all say “Paris is safe, people who think crime is a problem there are idiots,” except maybe when an American is in the room and then the point is to pull rank on the American.

In Paris, in French, there are lists of sensitive city quarters, and there are arrondissements that are more fashionable than others. The 18th, 19th, and 20th are usually negatively stereotyped, if less so than the adjacent department, Seine-Saint-Denis, which is extremely negatively stereotyped. The 13th is negatively stereotyped, but this is likely to be missed by Americans – the population there is disproportionately Asian, and negative stereotypes of Asians by white people are worse in France than in the United States. Belleville, straddling the 10th/11th/19th/20th boundary, was listed as a sensitive quarter when I lived just outside its limits and went in frequently to buy tahini – and at the time, I saw either British or American media, I forget which, list these quarters as no-go zones.

Now, these are residential areas. The center of Paris is well to the west of these. But Paris has a low job density gradient within city limits between commercial areas (like the 1st or the 8th) and residential ones, and the Ministry of the Interior, for example, is located in the 20th, close to Nation. People commute to these neighborhoods, usually by the Métro or RER. Nation, at the 11th/12th/20th boundary, is a mixed zone, with features that connote middle-class consumption (like the farmer’s market) and others that connote poverty (like a Resto du Cœur; see citywide map here). The sort of people in France who see a black or Arab person on the street and immediately panic find the area dangerous, including at one point the minister of the interior himself, who professed to being shocked at seeing ethnic food at the supermarket.

And none of this matters to public transportation investment, or to housing. In a country where people treat the entire department of Seine-Saint-Denis as a no-go zone except for football games at the Stade de France, where the RER B has such a negative reputation for passing through this area that two different airport connectors are planned to parallel it, Grand Paris Express is still planned to make stops in Seine-Saint-Denis, and connect it better with the rest of the region, including the wealthy suburbs around La Défense. This was a bipartisan decision – there were differences between the Socialists’ and the Gaullists’ ideas of what exactly to build, but there was core agreement on a circumferential line through the inner suburbs, and it is considered a social policy to connect working-class suburbia with jobs.

Stereotypes and local empowerment

The stereotypes of crime in parts of the Paris region do not affect urban rail investment plans. Where they do matter is at the level that doesn’t matter: the local one. Anne Hidalgo is a committed leftist (and NIMBY), but centrist and center-right politicians in the region have long wanted an urban renewal project around Gare du Nord, which they consider a poor area, not because it’s especially poor, but because it’s where the commuter trains from Seine-Saint-Denis go and thus young black and Arab men congregate there, and the station’s facilities could genuinely use some modernization. Occasionally the negative stereotypes of the station even get to British media. But whether Paris engages in a wholesale renewal project around the station to make it more upscale is not going to matter in the grand scheme of things to either its public transport ridership or its overall level of housing production.

The difference between Paris and New York or San Francisco is not that it has lower crime, although its homicide rate is certainly lower. It’s that it doesn’t derail its social policy discourse by turning technocratic issues into culture wars. Paris has unstaffed sanisettes; in a handful of areas there’s drug use, seen as used syringes. San Francisco, like Paris, has a handful of areas with drugs in its sanisettes, but the moral panic got to the point that the city decided to staff all sanisettes 24/7, with two attendants at night. Paris’s 435 sanisettes cost 11 million € a year to operate, 25,300€ per unit; San Francisco’s annual operating costs are on the order of $1 million per unit because of staffing.

This isn’t because of crime, because San Francisco is not sufficiently more dangerous than Paris to explain this, or even the perceptions thereof. The difference is that European governance is, across the board, better than American governance at disempowering local actors, who are driven by stereotypes. Anne Hidalgo doesn’t want to build housing in significant quantities, but does want to build some public housing in rich neighborhoods to own the libs (French definition of libs), and she’s the mayor and the residents of the 16th are not; Ile-de-France writ large wants to do more transit-oriented development, and so it builds some, even with some local grumbling about how redeveloping a disused factory brings gentrification.

And the way forward is to build institutions that bypass and disempower those local actors. People almost never stay within a neighborhood, but the small minority who do are overly empowered in the system of councilmanic prerogative that governs American cities. This does not involve treating their perception as if it is based in reality; this does involve passing preemption laws at the level where democratic politics is possible, such as the state, and doing much more than the weak bills California allows.

Ideology and reform

I think Noah is uncomfortable with American YIMBY praxis, because the rhetoric in a place like New York or California aims at the median Democrat in the state, to activate liberal political ideology as a substitute for the failures of non-ideological localism. This ideology is not especially radical, but does violate maxims that liberal pundits who specifically pitch to a conservative audience have learned to follow, like the taboo on calling people racist. The mainstream of political YIMBY advocacy has, I think, chosen better, understanding that at the end of the day, an upzoning bill in a safely blue state passes without Republican votes, and cutting deals with state Democratic actors, which can be localist (like exempting certain NIMBY suburbs with low transit-oriented development value) or more left-wing (like bundling with some left-wing elements, like Oregon’s introduction of weak rent controls).

And in a way, this is also how YIMBYism and public transportation investment work here, politically. As of late, social democratic parties have leaned on YIMBYism as a reason for non-pensioners to vote for them, calling for more housing permits; Olaf Scholz even called for redeveloping Tempelhofer Feld. Because it lives within a party, rather than among people who try to acknowledge culture war paranoias, the policy is clear, and sometimes can even be enacted – Germany would have built more housing if interest rates hadn’t simultaneously risen for unrelated reasons (namely, the combination of inflation and the Ukraine war). In France, it was a bipartisan effort in the sense that there wasn’t much daylight between the center-left and the center-right on the need for more housing in Ile-de-France, but the enactment did not involve the sort of horse trading that Noah envisions. This is not too different from infrastructure investments with bipartisan support elsewhere, such as the Madrid Metro, or Crossrail.

I think it’s telling that the greatest successes in the United States have not been in the most liberal places, but in swing states with liberal governance but competitive elections, like Minnesota. The barrier is not that the cities have crime or are negatively stereotyped (suburbanites around Minneapolis have plenty of those against the city), but that safe states have developed such a democratic deficit that they can’t govern. I’m fairly certain Noah is aware of this (Matt Yglesias certainly is). It just implies that this really is about seizing control of state government through ideological persuasion – in other words, reminding the Democrats of safely blue states that they are Democrats – and not about telling people way to the right of the median in these states that they are valid. We don’t do that here and American YIMBYs don’t need to do it on their side of the Pond.

Commuter Rail to Staten Island

A debate in my Discord channel about trains between Manhattan and Staten Island clarified to me why it’s so important that, in the event there is ever rail service there, it should use large commuter trains rather than smaller subway stations. The tradeoff is always that the longer trains used on commuter services lead to higher station construction costs than the smaller trains used on captive subway lines. However, the more difficult the tunnel construction is, and the fewer stations there are, the smaller the cost of bigger trains is. This argues in favor of commuter trains across the New York Harbor, and generally on other difficult water or mountain crossings.

When costing how much expansive commuter rail crayon is, like my Assume Normal Costs map, I have not had a hard time figuring out the station costs. The reason is that the station costs on commuter rail, done right, are fairly close to subway station costs, done wrong. As we find in the New York construction cost report, Second Avenue Subway’s 72nd and 86th Street stations were built about twice as large as necessary, and with deep-mined caverns. If you’re building a subway with 180 m long trains under Second Avenue, then mining 300-400 m long stations is an extravagance. If you’re building a regional rail tunnel under city center, and the surface stations are largely capable of 300 m long trains or can be so upgraded, then it’s normal. Thus, a cost figure of about $700 million per station is not a bad first-order estimate in city center, or even $1 billion in the CBD; outside the center, even large tunneled stations should cost less.

The cost above can be produced, for example, by setting the Union Square and Fulton Street stations at a bit less than $1 billion each (let’s say, $1.5 billion each, with each colored line contributing half), and a deep station under St. George at $500 million, totaling $2 billion. The 15 km of tunnel are then doable for $3 billion at costs not far below current New York tunneling costs. Don’t get me wrong, it still requires cost control policies on procurement and systems, but relative to what this includes, it’s not outlandish.

This, in turn, also helps explain the concept of regional rail tunnels. These are, in our database, consistently more expensive than metros in the same city; compare for example RER with Métro construction costs, or London Underground extensions with Crossrail, or especially the Munich U- and S-Bahn. The reason is that the concept of regional rail tunneling is to only build the hard parts, under city center, and then use existing surface lines farther out. For the same reason, the stations can be made big – there are fewer of them, for example six on the original Munich S-Bahn and three on the second trunk line under construction whereas the Munich U-Bahn lines have between 13 and 27, which means that the cost of bigger stations is reduced compared with the benefit of higher capacity.

This mode is then appropriate whenever there is good reason to build a critical line with relatively few stations. This can be because it’s a short connection between terminals, the usual case of most RER and S-Bahn lines; in the United States, the Center City Commuter Connection is such an example, and so is the North-South Rail Link if it is built. This can also be because it’s an express line parallel to slower lines, like the RER A. But it can also be because it doesn’t need as many stations because it crosses water, like any route serving Staten Island.

The flip side is that whenever many stations are required on an urban rail tunnel, it becomes more important to keep costs down by, potentially, shrinking the station footprint through using shorter trains. In small enough cities, as is the case in some of the Italian examples discussed in that case, like Brescia and Turin, it’s even possible to build very short station platforms and compensate by running driverless trains very frequently, producing an intermediate-capacity system. In larger cities, this trick is less viable, but sometimes there are corridors where there is no alternative to a frequent-stop urban tunnel, such as Utica in New York, and then, regional rail loses value. But in the case of Staten Island, to the contrary, commuter rail is the most valuable option.

Quick Note: Kathy Hochul and Eric Adams Want New York to Be Worse at Building Infrastructure

Progressive design-build just passed. This project delivery system brings New York in full into the globalized system of procurement, which has led to extreme cost increases in the United Kingdom, Canada, and other English-speaking countries, making them unable to build any urban transit megaprojects. Previously, New York had most of the misfeatures of this system, largely through convergent evolution, but due to slowness in adapting outside ideas, the state took until now, with extensive push from Adams’ orbit, for which Adams is now taking credit, to align. Any progress in cost control through controlling project scope will now be wasted on the procurement problems caused by this delivery method.

What is progressive design-build?

Progressive design-build is a variant on design-build. There is some divergence between New York terminology and rest-of-world terminology; for people who know the latter, progressive design-build is approximately what the rest of the world calls design-build.

To give more detail, designing and constructing a piece of infrastructure, say a single subway station, are two different tasks. In the traditional system of procurement, the public client contracts the design with one firm, and then bids it out to a different firm for construction; this is called design-bid-build. All low-construction cost subway systems that we are aware of use a variant of design-bid-build, but two key features are required to make it work: sufficient in-house supervision capacity since the agency needs to oversee both the design and the build contracts, and flexibility to permit the build contractors to make small changes to the design based on spot prices of materials and labor or meter-scale geological discoveries. The exact details of both in-house capacity and flexibility differ by country; for example, Turkey codifies the latter by having the design contract only cover 60% design, and bundling going from 60% to 100% design with the build contract. Despite the success of the system in low-construction cost environments, it is unpopular among the global, especially English-speaking, firms, because it is essentially client-centric, relying on high competence levels in the public sector to work.

To deal with the facts that large global firms think they are better than the public sector, and that the English-speaking world prefers its public sector to be drowned in a bathtub, there are alternative, contractor-centric systems of project delivery. The standard one in the globalized system is called design-build or design-and-build, and simply means that the same contractor does both. This means less public-facing friction between designers and builders, and more friction that’s hidden from public view. Less in-house capacity is required, and the contracts grow larger, an independent feature of the globalized system. As the Swedish case explains in the section on the traditional and globalized systems, globalized Swedish contracts go up to $300-500 million per contract (and Swedish costs, once extremely low, are these days only medium-low); in New York, contracts for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 are already in the $1-2 billion range.

In New York, the system is somewhat complicated by the text of legacy rules on competitive bidding, which outright forbid a company from portraying itself as doing both design and construction. It took recent changes to legalize the Turkish system of bundling the two contracts differently; this changed system is what is called design-build in New York and is used for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, even though there are still separate design and construction contracts, and is even called design-build in Turkey.

Unfortunately, New York did not stop at this, let’s call it, des-bid-ign-build system. Adams and Hochul want to be sure to wreck state capacity. Thus, they’ve pushed for progressive design-build, which is close to what the rest of the world calls design-build. More precisely, the design contractor makes a build bid at the end of the design phase, and is presumed to become the build contractor, but if the price is too high, there’s an escape clause and then it becomes essentially design-bid-build.

The globalized system that led to a cost explosion in the UK and Canada in the 1990s and 2000s from reasonable to strong candidates for second worst in the world (after the US) is now coming to New York, which already has a head start in high construction costs due to other problems. It’s a win-win for political appointees and cronies, and they clearly matter more than the people of the city and state of New York.

Kathy Hochul Can Only Solve Problems She Created

After the election, with the congestion pricing lawsuit hearings looming, Kathy Hochul announced that she’s going to restore congestion pricing, at the lower rate of $9 per entry, as opposed to the $15 per entry in the original program that she’d unilaterally canceled in June weeks before it was supposed to begin implementation.

The main reaction by transit advocacy groups in the region seems to be “We did it”: the combination of political pressure (reducing the governor’s approval rate), bottom-up pressure like mass phone calls, and lawfare led her to go back and restore 60% of congestion pricing. Perhaps, after the lawsuit is resolved, she will stop violating 40% of the law and go back to following it entirely.

But then there are people who insist that this was some savvy political move to delay congestion pricing until after the election, to save some congressional Democrats. This is stupid. The Democrats did okay in the congressional elections in the region, but their performance in the presidential election, in which Donald Trump tried to make congestion pricing an issue, was beyond awful, with the single largest Republican swing in the country from 2020, followed by adjacent New Jersey and frequent destination for out-migrants Florida. No: people rejected Hochul’s capricious government as much as they could given other partisan and ideological views.

Because what we’re seeing is that Hochul is perfectly capable of solving a problem – well, 60% of a problem – provided she is the sole cause of it. Otherwise, she can’t do anything. The state has a stack of problems, and she and the political appointees, including both her own and those carried over from Cuomo, can’t do anything to solve them, and I don’t even think they have any interest in. They lower people’s expectations so that they can claim credit for meeting 60% of them. No wonder people think so little of New York governance.

Transit Advocacy and (Lack of) Ideology in New York

I wrote recently about ideology in transit advocacy and in advocacy in general. The gist is that New York lacks any ideological politics, and as a result, transit advocacy either is genuinely non-ideological, or sweeps ideology under the rug; dedicated ideological advocates tend to either be subsumed in this sphere or go to places that don’t really connect with transit as it is and propose increasingly unhinged ideas. The ideological mainstream in the city is not bad, but the lack of choice makes it incapable of delivering results, and the governments at both the city and state levels are exceptionally clientelist, due to the lack of political competition. I’m not optimistic about political competition at the level of advocacy, but it would be useful to try introducing some in order to create more surface area for solutions to come through, and to make it harder for lobbyists to buy interest groups.

Political divides in New York

The political mainstream in New York is broadly left-liberal. New York voters consistently vote for federal politicians who promise to avoid tax cuts on high-income earners and corporations and even increase taxes on this group, and in exchange increase spending on health care, with some high-profile area politicians pushing for nationwide universal health care. They vote for more stringent regulations on businesses, for labor-friendlier administrative actions during major strikes, and for more hawkish solutions to climate change.

And none of that is really visible in state or city politics. Moreover, there isn’t really any political faction that voters can pick to support any of these positions, or to oppose them (except the Republicans, who are well to the right of the median state voter). The Working Families Party exists to cross-endorse Democrats via a different line; there is no fear by a Democrat that if they are too centrist for the district voters will replace them with a WFP representative, or that if they are too left-wing they will replace them with a non-WFP representative. There was a primary bloodbath in 2018, but it came from people running for the State Senate as party Democrats opposed to the Cuomo-endorsed Independent Democratic Conference, which broke from the party to caucus with Republicans.

The political divides that do exist, especially at the city level, break down as machine vs. reform candidates. But even that is not always clear, even as Eric Adams is unambiguously machine. The 2013 Democratic mayoral primary did not feature a clear machine candidate facing a clear reform candidate: Bill de Blasio ran on an ideologically progressive agenda, and implemented one small element of it in universal half-day pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds, but he ingratiated himself with the Brooklyn machine, to the point of steering endorsements in the 2021 primary toward Adams, and against the reform candidate, his own appointee Kathryn Garcia.

Political divides and advocacy

The mainstream of political opinion in New York ranges from center to mainline-left. But within that mainstream, there is no ideological competition, not just in politics, but also in advocacy. Transit advocacy, in particular, is not divided into more centrist and more left-wing groups.

The main transit advocacy groups in New York are instead distinguished by focus and praxis, roughly in the following way:

- The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA (PCAC) is on the inside track of advocacy, proposing small changes within the range of opinions on the MTA board.

- Riders Alliance (RA) is on the outside track, focusing on public transit, with praxis that includes rallies, joint proposals with large numbers of general or neighborhood-scale advocacy groups, and some support for lawfare (they are part of the lawsuit against Kathy Hochul’s cancellation of congestion pricing).

- Transportation Alternatives (TransAlt) focuses on street-level changes including pedestrian and bike advocacy, using the same tools of praxis as RA.

- Streetsblog is advocacy-oriented media.

- Straphangers Campaign is subway-focused, and uses reports and media outreach as its praxis, like the Pokey Awards for the slowest bus routes.

- Charlie Komanoff (of the Carbon Tax Center) focuses on producing research that other advocacy groups can use, for example about the benefits of congestion pricing.

The group I’m involved in, the Effective Transit Alliance, is distinguished by doing technical analysis that other groups can use, for example on RA’s Six-Minute Service campaign (statement 1, statement 2), or other-city groups pushing rail electrification; it is in the middle between outside and inside strategies.

Of note, none of these is distinguished by ideology. There is no specifically left-wing transit advocacy group, focusing on issues like supporting the TWU and ATU in disputes with management, getting cops off the subway, and investing in environmental justice initiatives like bus depot electrification to reduce local diesel pollution.

Neither is there a specifically neoliberal transit advocacy group. There are plenty of general advocacy groups with that background, like Abundance New York, but they’re never specific to transit, and much of their agenda, like expansion of renewable power, would not offend ideological socialists. YIMBY as a movement has neoliberal roots, going back to the original New York YIMBY publication, but these days is better viewed as a reform movement fighting the reformers of the last quarter of the 20th century, with the machine adjudicating between the two sides (City of Yes is an Adams proposal; the machine was historically pro-developer).

Instead, all advocacy groups end up arguing using a combination of median-New Yorker ideological language and technocratic proposals (again, Six-Minute Service). Taking sides in labor versus management disputes is viewed as the domain of the unions and managers, not outside groups. RA’s statement on cops on the subway is telling: it uses left-wing NGO language like “people experiencing homelessness,” but of its four policy proposals, only the last, investing in supportive housing for the homeless, is ideologically left-wing, and the first and third, respectively six-minute service and means-tested fare reductions for the poor, would find considerable support in the growing neoliberal community.

The consequences to the extremes

If the mainstream in New York ranges from dead center to center-left, both the general right and the radical left end up on the extremes. These have their own general advocacy groups: the Manhattan Institute (MI) on the right, and the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and its allies on the radical left. MI has recently moved to the right on national culture war issues, especially under Reihan Salam as he hired Christopher Rufo, but on local governance issues it’s not at all radical, and highlights center-right concerns with crime and with waste, fraud, and abuse in the public sector. DSA intends to take the most radical left position on issues that is available within the United States.

And both, as organizations, are pretty bad on this issue. MI, in particular, uses SeeThroughNY, the applet for public-sector worker salaries, not for analysis, but for shaming. I’ve had to complain to MI members on Twitter just to get the search function on job titles to work better, and even after they did some UI improvements, it’s harder to find the average salaries and headcounts by position to figure out things like maintenance worker productivity or white-collar overhead rates, than to find the highest-paid workers in a given year and write articles in the New York Post to shame them for racking so much overtime.

Then there is the proposal, I think by Nicole Gelinas, to stop paying subway crew for their commutes. This is not possible under current crew scheduling: train operators and conductors pick their shifts in seniority order, and low-seniority workers have no control over which of the railyards located at the fringes of the city they will have to report to. A business can reasonably expect a worker to relocate if the place the worker reports to will stay the same for the next few years; but if the schedules change every six months and even within this period they send workers to inconsistent railyards, it is not reasonable and the employer must pay for the commute, which in this circumstance is within private-sector norms.

DSA, to the extent it has a dedicated platform on public transit, is for free transit, and failing that, for effectively decriminalizing fare beating. More informed transit advocates, even very left-wing ones, persistently beg DSA to understand that for any given subsidy level, it’s better to increase service than to reduce fares, with exceptions only for places with extremely low ridership, low average rider incomes, and near-zero farebox recovery ratios. In Boston, Michelle Wu was even elected mayor on this agenda; her agenda otherwise is good, but MBTA farebox recovery ratios are sufficient that the revenue loss would bite, and as a result, all the city has been able to fund is some pilot projects on a few bus routes, breaking fare integration in the process since there is no way the subway is going fare-free.

In both cases, what is happening is that the ideological advocacy groups are distinct from the transit advocacy groups, and people are rarely well-respected in both – at most, they can be on the edge in both (like Gelinas). The result is that DSA will come up with ideas that are untethered from the reality of transit, and that every left-wing idea that could work would rapidly be taken up by groups that are not ideologically close to DSA, giving it a neoliberal reputation; symmetrically, this is true of the entire right, including MI.

The limits of the lack of ideology

The lack of ideology is not a good thing. With no ideological competition, voters have no clear way of picking politicians, which results in dynasties and handpicked successors. Lobbyists know who they need to curry favor with, making it cheaper to buy the government than to improve productivity; once it’s cheap to buy the government, the tax system ends up falling on whoever has been worst at buying influence, leading to high levels of distortion even with tax rates that, by Western European standards, are not high.

The quality of government in this situation is not good; corruption parties are not good when they govern entire countries, like the LDP in Japan or Democrazia Cristiana in Cold War Italy, and they’re definitely not good at the subnational level, where there is less media oversight. On education, for example, New York City pays starting teachers with a master’s degree $72,832/year in 2024, which compares with a German range for A13 starting teachers (in most states covering all teachers, in some only academic secondary teachers) of 50,668€/year in Rhineland-Pfalz to 57,288€/year in Bavaria; the PPP rate these days is 1€ = $1.45, so German teachers earn 1-14% more than their New York counterparts, while the average income from work ranges from 5% higher in New York than in Bavaria to 68% higher than Saxony-Anhalt. This stinginess with teacher salaries does not go to a higher teacher-to-student ratios, both New York and Germany averaging about 1:13, or to savings on the education budget, New York spending around twice as much as Germany. The waste is not talked about in the open, and even the concept that teachers deserve a raise, independently of budgetary efficiency, does not exist in city politics; it’s viewed as the sole domain of the unions to demand salary increases, and the idea that people can elect more pro-labor politicians who run on explicit platforms of salary increases is unthinkable.

In transit, I don’t have a good comparison of New York. But I do suspect that the single-party rule of CSU in Bavaria is responsible for the evident corruption levels in the party and the high costs of the urban rail projects that CSU cares about, namely the Munich S-Bahn second trunk line, which is setting Continental European records for its high costs. Likewise, in Italy, the era of DC domination was also called the Tangentopoli, and bribes for contracts were common, raising costs; the destruction of that party system under mani pulite and its replacement with alternation of power between left and right coalitions since has coincided with strong anti-corruption laws and real reductions in costs from the levels of the 1980s.

We haven’t found corruption in New York when researching the Second Avenue Subway case. But we have found extreme levels of intellectual laziness at the top, by political appointees who are under pressure not to innovate rather than to showcase success.

And likewise, at ETA, I’m seeing an advocacy sphere that is constrained by court politics. It’s considered uncouth to say that the governor is a total failure and so are all of her and her predecessor’s political appointees until proven otherwise. There’s no party or faction system that has incentives to find and publicize their failures; as it is, the people trying to replace Adams as mayor are barely even factional, and name recognition is so important that Andrew Cuomo is thinking of making a comeback, perhaps to kill another few tens of thousands of city residents that he missed in 2020. Any advocacy subject to these constraints will fail to break the hierarchy that resists change, and reduce itself to flattering failed leaders in vain hopes that they might one day implement one good idea, take credit for it, and use the credit to legitimize their other failures.

Is there a way out?

I’m pessimistic; there’s a reason I chose not to live in New York despite, effectively, working there. Alternation of parties at the state or even city level is not useful. The Republicans are a permanent minority party in New York, at least in federal votes, and so a Republican who wants to win needs to not just moderate ideologically, which is not enough by itself, but also buy off non-ideological actors, leading to comparable levels of clientelism to those of the Democratic machine.

For example, Mike Bloomberg ran on his own technocratic competence, but lacking a party to work with in City Council, he failed on issues that today are considered core neoliberal priorities, namely housing. Housing permitting in 2002-13, when the city was economically booming, averaged 20,276/year, or around 2.5/1,000 people, rising slightly to 25,222/year, or around 3/1,000, during Bill de Blasio’s eight years; every European country builds more except economic basket cases, and the major cities and metro areas typically build more than the national average. The system of councilmanic privilege, in which City Council defers to the opinions of the member representing the district each proposed development, is a natural outgrowth of the lack of ideological competition, and blocks housing production; the technocrat Bloomberg was less capable of striking deals to build housing than the political hack de Blasio. And Bloomberg is a best-case scenario; George Pataki as governor was not at all a reformer, he just had somewhat different (mostly Long Island) clientelist interests.

David Schleicher proposes state parties as a solution to the system of single-party domination and councilmanic privilege. But in practice, there’s little reason for such parties to thrive. If two New York parties aim for the median state voter, then one will comprise Republicans and the rightmost 20% of Democrats and the other will comprise the remaining Democrats, and Democrats from the former party will be required to defend so many Republican policies for coalitional reasons. There’s no neat separation of state and federal priorities that would permit such Democrats to compartmentalize, and not enough specifically in-state media that would cover them in such a way rather than based on national labels; in practice, then, any such Democrat will be unable to win federal office as a Democrat, and as ambitious Democrats stick with the all-Democratic party, the 62-38 pattern of today will reassert itself.

In the city, two Democratic factions are in theory possible, a centrist one and a leftist one. A left-wing solution is in theory favored by most of the city, which is happy to vote for federal politicians who promise universal health care, free university tuition, universal daycare, or more support for teachers, which more or less exist in Germany with a much less left-wing electorate. In practice, none of these is even semi-seriously attempted city- or statewide, and the machine views its role as, partly, gatekeeping left-wing organizations, which in turn have little competence to implement these, and often get sidetracked with other priorities (like teacher union opposition to phonics, or extracting more money from developers for neighborhood priorities).

Public transit is, in effect, caught in a crossfire of political incompetence. I think advocacy would be better if there were a persistently left-wing advocacy org and a persistently neoliberal one, but in practice, machine domination is such that the socialists and neoliberals often agree on a lot of reforms (for example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has become fairly YIMBY).

But even then, advocacy organizations should be using their outside voice more and avoiding flattering people who don’t deserve it. People in New York know that they are governed by failures. The lack of ideology means that the Republican nearly 40% of the state thinks they are governed by left-wing failures while the Democratic base thinks they are governed by centrist and Republicratic failures, but there’s widespread understanding that the government is inefficient. Advocates do not need to debase themselves in front of people who cost the region millions of dollars every day that they get up in the morning, go to work, and make bad decisions on transit investment and operations. There’s a long line of people who do flattery better than any advocate and will get listened to first by the hierarchy; the advocates’ advantage is not in flattery but in knowing the system better than the political appointees to the point of being able to make good proposals that the hierarchy is too incompetent to come up with or implement on its own.