Category: Politics and Society

Transit Advocacy and (Lack of) Ideology in New York

I wrote recently about ideology in transit advocacy and in advocacy in general. The gist is that New York lacks any ideological politics, and as a result, transit advocacy either is genuinely non-ideological, or sweeps ideology under the rug; dedicated ideological advocates tend to either be subsumed in this sphere or go to places that don’t really connect with transit as it is and propose increasingly unhinged ideas. The ideological mainstream in the city is not bad, but the lack of choice makes it incapable of delivering results, and the governments at both the city and state levels are exceptionally clientelist, due to the lack of political competition. I’m not optimistic about political competition at the level of advocacy, but it would be useful to try introducing some in order to create more surface area for solutions to come through, and to make it harder for lobbyists to buy interest groups.

Political divides in New York

The political mainstream in New York is broadly left-liberal. New York voters consistently vote for federal politicians who promise to avoid tax cuts on high-income earners and corporations and even increase taxes on this group, and in exchange increase spending on health care, with some high-profile area politicians pushing for nationwide universal health care. They vote for more stringent regulations on businesses, for labor-friendlier administrative actions during major strikes, and for more hawkish solutions to climate change.

And none of that is really visible in state or city politics. Moreover, there isn’t really any political faction that voters can pick to support any of these positions, or to oppose them (except the Republicans, who are well to the right of the median state voter). The Working Families Party exists to cross-endorse Democrats via a different line; there is no fear by a Democrat that if they are too centrist for the district voters will replace them with a WFP representative, or that if they are too left-wing they will replace them with a non-WFP representative. There was a primary bloodbath in 2018, but it came from people running for the State Senate as party Democrats opposed to the Cuomo-endorsed Independent Democratic Conference, which broke from the party to caucus with Republicans.

The political divides that do exist, especially at the city level, break down as machine vs. reform candidates. But even that is not always clear, even as Eric Adams is unambiguously machine. The 2013 Democratic mayoral primary did not feature a clear machine candidate facing a clear reform candidate: Bill de Blasio ran on an ideologically progressive agenda, and implemented one small element of it in universal half-day pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds, but he ingratiated himself with the Brooklyn machine, to the point of steering endorsements in the 2021 primary toward Adams, and against the reform candidate, his own appointee Kathryn Garcia.

Political divides and advocacy

The mainstream of political opinion in New York ranges from center to mainline-left. But within that mainstream, there is no ideological competition, not just in politics, but also in advocacy. Transit advocacy, in particular, is not divided into more centrist and more left-wing groups.

The main transit advocacy groups in New York are instead distinguished by focus and praxis, roughly in the following way:

- The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA (PCAC) is on the inside track of advocacy, proposing small changes within the range of opinions on the MTA board.

- Riders Alliance (RA) is on the outside track, focusing on public transit, with praxis that includes rallies, joint proposals with large numbers of general or neighborhood-scale advocacy groups, and some support for lawfare (they are part of the lawsuit against Kathy Hochul’s cancellation of congestion pricing).

- Transportation Alternatives (TransAlt) focuses on street-level changes including pedestrian and bike advocacy, using the same tools of praxis as RA.

- Streetsblog is advocacy-oriented media.

- Straphangers Campaign is subway-focused, and uses reports and media outreach as its praxis, like the Pokey Awards for the slowest bus routes.

- Charlie Komanoff (of the Carbon Tax Center) focuses on producing research that other advocacy groups can use, for example about the benefits of congestion pricing.

The group I’m involved in, the Effective Transit Alliance, is distinguished by doing technical analysis that other groups can use, for example on RA’s Six-Minute Service campaign (statement 1, statement 2), or other-city groups pushing rail electrification; it is in the middle between outside and inside strategies.

Of note, none of these is distinguished by ideology. There is no specifically left-wing transit advocacy group, focusing on issues like supporting the TWU and ATU in disputes with management, getting cops off the subway, and investing in environmental justice initiatives like bus depot electrification to reduce local diesel pollution.

Neither is there a specifically neoliberal transit advocacy group. There are plenty of general advocacy groups with that background, like Abundance New York, but they’re never specific to transit, and much of their agenda, like expansion of renewable power, would not offend ideological socialists. YIMBY as a movement has neoliberal roots, going back to the original New York YIMBY publication, but these days is better viewed as a reform movement fighting the reformers of the last quarter of the 20th century, with the machine adjudicating between the two sides (City of Yes is an Adams proposal; the machine was historically pro-developer).

Instead, all advocacy groups end up arguing using a combination of median-New Yorker ideological language and technocratic proposals (again, Six-Minute Service). Taking sides in labor versus management disputes is viewed as the domain of the unions and managers, not outside groups. RA’s statement on cops on the subway is telling: it uses left-wing NGO language like “people experiencing homelessness,” but of its four policy proposals, only the last, investing in supportive housing for the homeless, is ideologically left-wing, and the first and third, respectively six-minute service and means-tested fare reductions for the poor, would find considerable support in the growing neoliberal community.

The consequences to the extremes

If the mainstream in New York ranges from dead center to center-left, both the general right and the radical left end up on the extremes. These have their own general advocacy groups: the Manhattan Institute (MI) on the right, and the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and its allies on the radical left. MI has recently moved to the right on national culture war issues, especially under Reihan Salam as he hired Christopher Rufo, but on local governance issues it’s not at all radical, and highlights center-right concerns with crime and with waste, fraud, and abuse in the public sector. DSA intends to take the most radical left position on issues that is available within the United States.

And both, as organizations, are pretty bad on this issue. MI, in particular, uses SeeThroughNY, the applet for public-sector worker salaries, not for analysis, but for shaming. I’ve had to complain to MI members on Twitter just to get the search function on job titles to work better, and even after they did some UI improvements, it’s harder to find the average salaries and headcounts by position to figure out things like maintenance worker productivity or white-collar overhead rates, than to find the highest-paid workers in a given year and write articles in the New York Post to shame them for racking so much overtime.

Then there is the proposal, I think by Nicole Gelinas, to stop paying subway crew for their commutes. This is not possible under current crew scheduling: train operators and conductors pick their shifts in seniority order, and low-seniority workers have no control over which of the railyards located at the fringes of the city they will have to report to. A business can reasonably expect a worker to relocate if the place the worker reports to will stay the same for the next few years; but if the schedules change every six months and even within this period they send workers to inconsistent railyards, it is not reasonable and the employer must pay for the commute, which in this circumstance is within private-sector norms.

DSA, to the extent it has a dedicated platform on public transit, is for free transit, and failing that, for effectively decriminalizing fare beating. More informed transit advocates, even very left-wing ones, persistently beg DSA to understand that for any given subsidy level, it’s better to increase service than to reduce fares, with exceptions only for places with extremely low ridership, low average rider incomes, and near-zero farebox recovery ratios. In Boston, Michelle Wu was even elected mayor on this agenda; her agenda otherwise is good, but MBTA farebox recovery ratios are sufficient that the revenue loss would bite, and as a result, all the city has been able to fund is some pilot projects on a few bus routes, breaking fare integration in the process since there is no way the subway is going fare-free.

In both cases, what is happening is that the ideological advocacy groups are distinct from the transit advocacy groups, and people are rarely well-respected in both – at most, they can be on the edge in both (like Gelinas). The result is that DSA will come up with ideas that are untethered from the reality of transit, and that every left-wing idea that could work would rapidly be taken up by groups that are not ideologically close to DSA, giving it a neoliberal reputation; symmetrically, this is true of the entire right, including MI.

The limits of the lack of ideology

The lack of ideology is not a good thing. With no ideological competition, voters have no clear way of picking politicians, which results in dynasties and handpicked successors. Lobbyists know who they need to curry favor with, making it cheaper to buy the government than to improve productivity; once it’s cheap to buy the government, the tax system ends up falling on whoever has been worst at buying influence, leading to high levels of distortion even with tax rates that, by Western European standards, are not high.

The quality of government in this situation is not good; corruption parties are not good when they govern entire countries, like the LDP in Japan or Democrazia Cristiana in Cold War Italy, and they’re definitely not good at the subnational level, where there is less media oversight. On education, for example, New York City pays starting teachers with a master’s degree $72,832/year in 2024, which compares with a German range for A13 starting teachers (in most states covering all teachers, in some only academic secondary teachers) of 50,668€/year in Rhineland-Pfalz to 57,288€/year in Bavaria; the PPP rate these days is 1€ = $1.45, so German teachers earn 1-14% more than their New York counterparts, while the average income from work ranges from 5% higher in New York than in Bavaria to 68% higher than Saxony-Anhalt. This stinginess with teacher salaries does not go to a higher teacher-to-student ratios, both New York and Germany averaging about 1:13, or to savings on the education budget, New York spending around twice as much as Germany. The waste is not talked about in the open, and even the concept that teachers deserve a raise, independently of budgetary efficiency, does not exist in city politics; it’s viewed as the sole domain of the unions to demand salary increases, and the idea that people can elect more pro-labor politicians who run on explicit platforms of salary increases is unthinkable.

In transit, I don’t have a good comparison of New York. But I do suspect that the single-party rule of CSU in Bavaria is responsible for the evident corruption levels in the party and the high costs of the urban rail projects that CSU cares about, namely the Munich S-Bahn second trunk line, which is setting Continental European records for its high costs. Likewise, in Italy, the era of DC domination was also called the Tangentopoli, and bribes for contracts were common, raising costs; the destruction of that party system under mani pulite and its replacement with alternation of power between left and right coalitions since has coincided with strong anti-corruption laws and real reductions in costs from the levels of the 1980s.

We haven’t found corruption in New York when researching the Second Avenue Subway case. But we have found extreme levels of intellectual laziness at the top, by political appointees who are under pressure not to innovate rather than to showcase success.

And likewise, at ETA, I’m seeing an advocacy sphere that is constrained by court politics. It’s considered uncouth to say that the governor is a total failure and so are all of her and her predecessor’s political appointees until proven otherwise. There’s no party or faction system that has incentives to find and publicize their failures; as it is, the people trying to replace Adams as mayor are barely even factional, and name recognition is so important that Andrew Cuomo is thinking of making a comeback, perhaps to kill another few tens of thousands of city residents that he missed in 2020. Any advocacy subject to these constraints will fail to break the hierarchy that resists change, and reduce itself to flattering failed leaders in vain hopes that they might one day implement one good idea, take credit for it, and use the credit to legitimize their other failures.

Is there a way out?

I’m pessimistic; there’s a reason I chose not to live in New York despite, effectively, working there. Alternation of parties at the state or even city level is not useful. The Republicans are a permanent minority party in New York, at least in federal votes, and so a Republican who wants to win needs to not just moderate ideologically, which is not enough by itself, but also buy off non-ideological actors, leading to comparable levels of clientelism to those of the Democratic machine.

For example, Mike Bloomberg ran on his own technocratic competence, but lacking a party to work with in City Council, he failed on issues that today are considered core neoliberal priorities, namely housing. Housing permitting in 2002-13, when the city was economically booming, averaged 20,276/year, or around 2.5/1,000 people, rising slightly to 25,222/year, or around 3/1,000, during Bill de Blasio’s eight years; every European country builds more except economic basket cases, and the major cities and metro areas typically build more than the national average. The system of councilmanic privilege, in which City Council defers to the opinions of the member representing the district each proposed development, is a natural outgrowth of the lack of ideological competition, and blocks housing production; the technocrat Bloomberg was less capable of striking deals to build housing than the political hack de Blasio. And Bloomberg is a best-case scenario; George Pataki as governor was not at all a reformer, he just had somewhat different (mostly Long Island) clientelist interests.

David Schleicher proposes state parties as a solution to the system of single-party domination and councilmanic privilege. But in practice, there’s little reason for such parties to thrive. If two New York parties aim for the median state voter, then one will comprise Republicans and the rightmost 20% of Democrats and the other will comprise the remaining Democrats, and Democrats from the former party will be required to defend so many Republican policies for coalitional reasons. There’s no neat separation of state and federal priorities that would permit such Democrats to compartmentalize, and not enough specifically in-state media that would cover them in such a way rather than based on national labels; in practice, then, any such Democrat will be unable to win federal office as a Democrat, and as ambitious Democrats stick with the all-Democratic party, the 62-38 pattern of today will reassert itself.

In the city, two Democratic factions are in theory possible, a centrist one and a leftist one. A left-wing solution is in theory favored by most of the city, which is happy to vote for federal politicians who promise universal health care, free university tuition, universal daycare, or more support for teachers, which more or less exist in Germany with a much less left-wing electorate. In practice, none of these is even semi-seriously attempted city- or statewide, and the machine views its role as, partly, gatekeeping left-wing organizations, which in turn have little competence to implement these, and often get sidetracked with other priorities (like teacher union opposition to phonics, or extracting more money from developers for neighborhood priorities).

Public transit is, in effect, caught in a crossfire of political incompetence. I think advocacy would be better if there were a persistently left-wing advocacy org and a persistently neoliberal one, but in practice, machine domination is such that the socialists and neoliberals often agree on a lot of reforms (for example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has become fairly YIMBY).

But even then, advocacy organizations should be using their outside voice more and avoiding flattering people who don’t deserve it. People in New York know that they are governed by failures. The lack of ideology means that the Republican nearly 40% of the state thinks they are governed by left-wing failures while the Democratic base thinks they are governed by centrist and Republicratic failures, but there’s widespread understanding that the government is inefficient. Advocates do not need to debase themselves in front of people who cost the region millions of dollars every day that they get up in the morning, go to work, and make bad decisions on transit investment and operations. There’s a long line of people who do flattery better than any advocate and will get listened to first by the hierarchy; the advocates’ advantage is not in flattery but in knowing the system better than the political appointees to the point of being able to make good proposals that the hierarchy is too incompetent to come up with or implement on its own.

Taxes are not About Urbanism

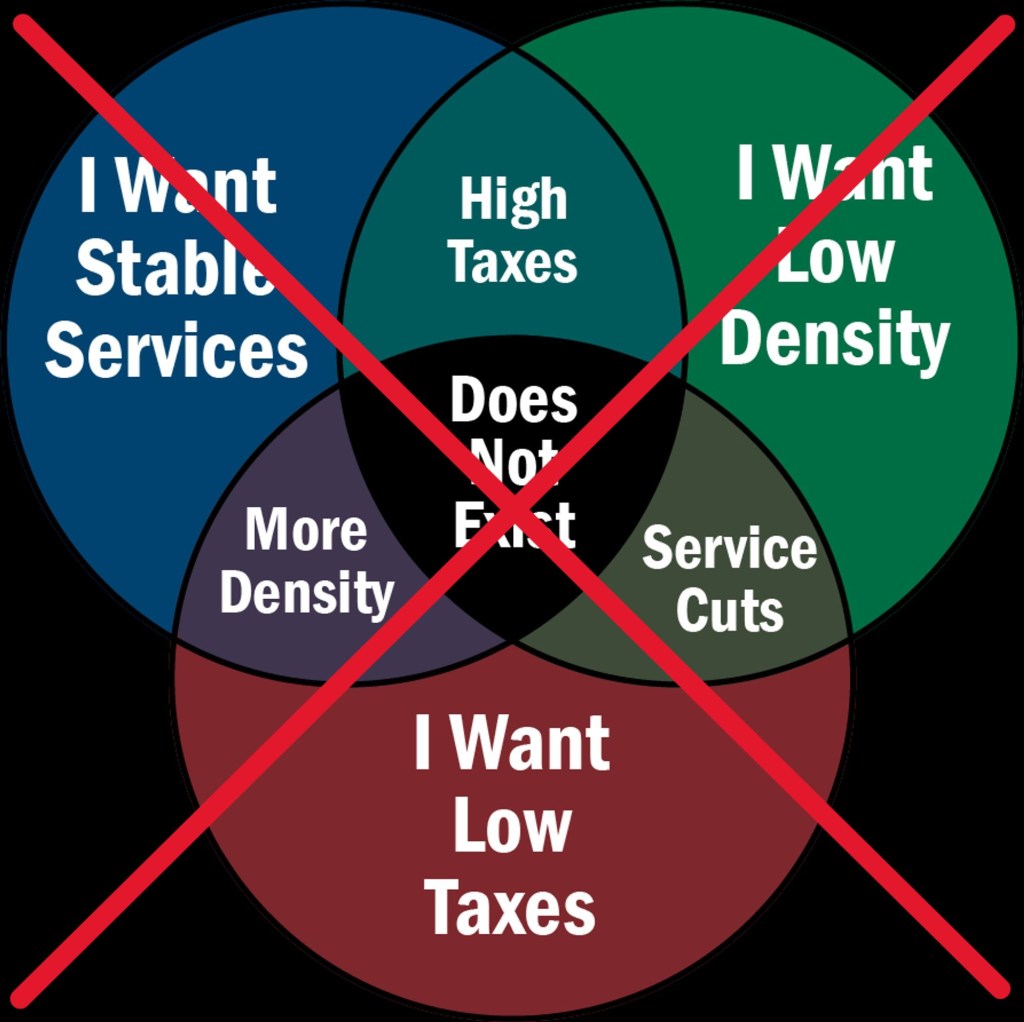

I caused a ruckus on social media when I pointed out that a Venn diagram commonly posted on Strong Towns and by American urbanists in general about taxes, services, and urbanism, is completely false:

The truth is that the overwhelming majority of taxes and services are about things that don’t meaningfully depend on local density. The overwhelming majority of those services are not even locally provided. In the United States, in 2022, taxes split as 67.5% federal, 19.1% state, 13.4% local. In Germany, in theory the division is similar, but in practice 95% of taxes are levied federally, but a portion are distributed to the states by formula.

Most of what all of this goes to is welfare programs. La Protection Sociale en France et en Europe puts the proportion of GDP going to social protection at 32% in France, 29% in Germany, and 27% Union-wide, all as of 2022. This includes programs whose recipients loudly insist that they are not welfare, including old age pensions and health care, comprising 82% of the above total. Government spending ranges around 50% of GDP here; France ranks first in the OECD, at 58%, so that its share of government spending going to social protection, slightly more than half, is if anything a little less than the European average. In the United States, these programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, income security) comprise two-thirds of non-interest federal spending, and one third of state and local spending. A couple additional percent – more in the United States than in Europe with one notable exception – is the military plus veteran-specific welfare in the US. None of this has anything to do with how much urban sprawl there is, or how municipal finances are structured.

Local taxes in the United States mostly go to schools. Education expenses are a combination of teacher and administrator salaries and facilities spending; these are not about density. Entire comparative tomes have been written about education funding, none touching density, because it doesn’t matter; for example, the OECD’s Education at a Glance database goes into per-student spending, teacher salaries, administrator salaries, student-teacher ratios, the public-private school division, the vocational-academic track division, graduation rates, the earnings advantages of graduates at various levels, and correlations with civic participation. The most notable features of the United States are high educational segregation, and low teacher salaries compared with the average for university-educated workers. This is not an urbanist issue; American urbanist activists have been spending generations avoiding talking about school segregation, to the point that the activists who do talk about education from any angle are more or less disjoint from the ones who talk about recognizably urbanist issue. The Venn diagram above is a good example of this: instead of talking about curricular rigor or teachers or segregation or how schools are funded, urbanists prefer to pretend reducing urban sprawl is the solution (not mentioned: any of the problems internal to, say, New York City public schools).

Once we get to items that do depend on what urbanists care about, it’s at the bottom of the list of budgetary priorities. Transportation costs are a small share of GDP; in the US, an extreme case in road costs, they’re 2% of federal spending and 5.6% of subnational spending, which averages out to somewhat more than 3% of GDP. German federal investment in roads is around 0.25% of GDP, and federal investment in rail is similar but planned to be double that in 2026-27. I haven’t seen more recent numbers, but in 2018, public transport finances across Germany amounted to 14.248 billion € in costs and 7.363 billion € in fare revenue; the difference, about 7 billion €, was 0.2% of 2018 GDP, covering about 16% of work trips Germany-wide.

So, yes, reduced sprawl would reduce the required spending on roads, but it’s not going to be especially visible in tax bills, which are dominated by other things. The biggest drivers of the cost of private transportation are the costs of buying, maintaining, and fueling the car. Those drive American spending on transportation to 17% of household spending, of which 8.3% are not cars, and buying the car and fuel for it are two thirds of the rest (that is, 10.3% of household spending). This is high per capita and per GDP; it is also not what urbanists who try to calculate operating ratios for roads talk about – the problem with private transportation is not the public cost of the roads, but the private cost to households.

Then there’s policing. Strong Towns has a particular infamy on the subject – Chuck Marohn essentially canceled himself among anyone concerned with civil rights when, during the initial Black Lives Matter protests in 2014, his take was about the lack of placemaking in suburbs like Ferguson, requiring people to protest in the middle of roads. On social media, multiple people insisted to me that higher density permits higher-quality (?) or lower-cost policing; at least as far as police brutality goes, the pattern is that it happens 1-2 orders of magnitude more in the US than in the rest of the developed world, and that in the US, it happens to black people about three times more than to white people, and it happens less in the Northeast than elsewhere, even in blacker-than-average places like Buffalo or Philadelphia. Urban departments are probably somewhat more professional than rural sheriffs’ departments, but this probably isn’t really a matter of suburban sprawl development but jurisdiction size, and is also not at all what the Venn diagram is trying to say. “Big central cities that have dense cores and can annex suburbs end up having very high police spending but get more professional departments out of this” is nowhere in the Venn diagram. It is not implied in it. It is directly opposed to what Strong Towns says about municipal finances, which is about long-term budgeting for municipalities with given borders and not about the desirability of delocalizing decisionmaking.

It’s always tempting to try to turn one’s issue into an omnicause. High taxes and poor services? Sprawl. Police violence? Sprawl. Schools? Sprawl. High housing costs? Sprawl. Government corruption? Sprawl. It creates an illusion of seriousness, of solving systemic social problems, while really only droning about one peripheral issue. It creates an illusion of outside-the-box solutions, while really ignoring real tradeoffs, in this case between taxes and government services. And it creates an illusion of solidarity and alliance between different advocacy groups, while really giving activists for one cause permission structure to bring up their pet cause no matter how unimportant it is in the moment.

Quick Note on Capital City Income Premiums

There’s a report by Sam Bowman, Samuel Hughes, and Ben Southwood, called Foundations, about flagging British growth, blaming among other things high construction costs for infrastructure and low housing production. The reaction on Bluesky seems uniformly negative, for reasons that I don’t think are fair (much of it boils to distaste for YIMBYism). I don’t want to address the construction cost parts of it for now, since it’s always more complicated and we do want to write a full case on London for the Transit Costs Project soon, but I do want to say something about the point about YIMBYism: dominant capitals and other rich cities (such as Munich or New York) have notable wage premiums over the rest of the country, but this seems to be the case in NIMBY environments more than in YIMBY ones. In fact, in South Korea and Japan, the premium seems rather low: the dominant capital attracts more domestic migration and becomes larger, but is not much richer than the rest of the country.

The data

In South Korea and Japan, what I have is Wikipedia’s lists of GDP per capita by province or prefecture. The capital city’s entire metro area is used throughout, comprising Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi in Korea, and Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama in Japan. In South Korea, the capital region includes 52.5% of GDP and 50.3% of population, for a GDP per capita premium of 4.4% over the country writ large, and (since half the country is metro Seoul) 9.2% over the rest of the country. In Japan, on OECD numbers, the capital region, labeled as Southern Kanto, has a 14.5% premium over the entire country, rising to around 19% over the rest of the country.

In contrast, in France, Ile-de-France’s premium from the same OECD data is 63% over France, rising to about 90% over provincial France. In the UK, London’s premium is 71% over the entire country and 92% over the entire country excluding itself; if we throw in South East England into the mix, the combined region has a premium of 38% over the entire country, and 62% over the entire country excluding itself.

Now, GDP is not the best measure for this. It’s sensitive to commute volumes and the locations of corporate headquarters, for one. That said, British, French, Korean and Japanese firms all seem to prefer locating firms in their capitals: Tokyo and Seoul are in the top five in Fortune 500 headquarters (together with New York, Shanghai, and Beijing), and London and Paris are tied for sixth, with one company short of #5. Moreover, the metro area definitions are fairly loose – there’s still some long-range commuting from Ibaraki to Tokyo or from Oise to Paris, but the latter is too small a volume to materially change the conclusion regarding the GDP per capita premium. Per capita income would be better, but I can only find it for Europe and the United States (look for per capita net earnings for the comparable statistic to Eurostat’s primary balance), not East Asia; with per capita income, the Ile-de-France premium shrinks to 45%, while that of Upper Bavaria over Germany is 39%, not much lower, certainly nothing like the East Asian cases.

Inequality

Among the five countries discussed above – Japan, Korea, the UK, Germany, France – the level of place-independent inequality does not follow the same picture at all. The LIS has numbers for disposable income, and Japan and Korea both turn out slightly more unequal than the other three. Of course, the statistics in the above section are not about disposable income, so it’s better to look at market income inequality; there, Korea is indeed far more equal than the others, having faced so much capital destruction in the wars that it lacks the entrenched capital income of the others – but Japan has almost the same market income inequality as the three European examples (which, in turn, are nearly even with the US – the difference with the US is almost entirely redistribution).

So it does not follow, at least not at first pass, that YIMBYism reduces overall inequality. It can be argued that it does and Japan and South Korea have other mechanisms that increase market income inequality, such as weaker sectoral collective bargaining than in France and Germany; then again, the Japanese salaryman system keeps managers’ wages lower than in the US and UK and so should if anything produce lower market income inequality (which it does, but only by about three Gini points). But fundamentally, this should be viewed as an inequality-neutral policy.

Discussion

What aggressive construction of housing in and around the capital does appear to do is permit poor people to move to or stay in the capital. European (and American) NIMBYism creates spatial stratification: the middle class in the capital, the working class far away unless it is necessary for it to serve the middle class locally. Japanese and Korean YIMBYism eliminate this stratification: the working class keeps moving to (poor parts of) the capital region.

What it does, at macro level, is increase efficiency. It’s not obvious to see this, since neither Japan nor Korea is a particularly high-productivity economy; then again, the salaryman system, reminiscent of the US before the 1980s, has long been recognized as a drag on innovation, so YIMBYism in effect countermands to some extent the problems produced by a dead-end corporate culture. It also reduces interregional inequality, but this needs to be seen less as more opportunity for Northern England as a region and more as the working class of Northern England as people moving to become the working class of London and getting some higher wages while also producing higher value for the middle class so that inequality doesn’t change.

Public Transportation and Gig Workers

An argument about public transportation fares on Bluesky two weeks ago led to the issue of gig workers, and how public transportation can serve their needs. Those are, for the purposes of this post, workers who do service jobs on demand, without fixed hours or a fixed place of work; these include delivery and cleaning workers. App-hailed drivers fall into this category too, but own cars and are by definition driving. When using public transit – and such workers rarely get paid enough to afford a car – they face long, unreliable travel times, usually by bus; their work travel is completely different from that of workers with consistent places of work, which requires special attention that I have not, so far, seen from transit agencies, even ones that do aim at service-sector shift workers.

The primary issue is one of work centralization. Public transit is the most successful when destinations are centralized; it scales up very efficiently because of the importance of frequency, whereas cars are the opposite, scaling up poorly and scaling down well because of the problems with traffic congestion. I went over this previously talking about Los Angeles, and then other American cities plus Paris. High concentration of jobs, more so than residential density (which Los Angeles has in droves), predicts transit usage, at metro area scale.

Job concentration is also fairly classed. In New York, as of 2015, the share of $40,000+/year workers who worked in the Manhattan core was 57%; for under-$40,000/year workers, it was 37%. It is not an enormous difference, but it makes enough of a difference that it makes it more convenient for the middle class to take transit, since it gets to where they want to go. In metro New York, the average income of transit commuters is the same as that of solo drivers; in secondary American transit cities like Chicago, transit commuters actually make more, since transit is so specialized to city center commutes.

Worse, those 37% of under-$40,000/year workers who work in the Manhattan core are ones with regular low-paying jobs in city center, rather than ones doing gig work. The difference is that gig workers work where the middle class lives, rather than where the middle class works (for example, food service workers at office buildings) or where it consumes (for example, mall retail workers). They still generally take transit or bike where that’s available (for example, in Berlin), because they don’t earn enough to afford cars, but their commutes are the ones that public transit is the worst at. They can’t even control where they work and move accordingly, because they by definition do gigs. In theory, it’s possible for apps to match workers to jobs within the right region or along the right line; in practice, the situation today is that the apps can send a worker from Bytom to Gliwice today and a worker from Gliwice to Bytom tomorrow, based on vagaries of regional supply and demand, and the Polish immigrant who complained to me about this with the names of those two specific cities wishes there were a way to match it better, but at least currently, there isn’t.

The upshot is that gig worker travel is, more or less, a subcase of isotropic, everywhere-to-everywhere systems, with no distinguished nodes. This has all of the following implications:

- Travel by rail alone is infeasible – last-mile bus connections are unavoidable, as are uncommon transfers, with three- and at times four-legged trips.

- The bus network has to have the usual features of a modernized, redesigned network, with high all-day frequency and regular transfers – suburb-to-city-center buses alone don’t cut it when the work is rarely in city center, and a focus on rush hour service is useless for workers who mostly travel outside peak hours. This also includes reforms that improve buses in general, regardless of the route taken: proof of payment, bus lanes, stop consolidation, bus shelter, signal priority at intersections.

- For the most part, the buses that take gig workers to work are the same that could take residents of those neighborhoods to work, in the opposite direction. However, in areas with weaker transit than Berlin or New York, much of the middle class drives, making buses within usually lower-density middle-class areas infeasible. In contrast, those buses are still likely to be used by gig workers doing service work in the homes of those drivers.

The last point, in particular, means that one of the more brutal features of bus redesigns – cutting coverage service in order to focus on the more useful routes – can be counterproductive. This is, again, not relevant to large enough cities that their middle classes mostly don’t live in coverage route territory (even Queens doesn’t need this tradeoff, let alone Brooklyn). But in New Haven, for example, Sandy Johnston long pointed out that some of the bus routes just don’t really work, no matter what, because the areas they serve are too low-density, so the only way forward is to prune them.

This more brutal treatment can still be understandable at times. If the route is being straightened rather than eliminated, as we discussed for Sioux City years later, then it provides all workers with faster service – the meanders if anything are to big job centers that are a few hundred meters off the arterial, and gig workers are less likely to be using those meanders than regular service workers. Moreover, if the part being pruned is genuinely low-density, then it may well also have low density of destinations for gig workers. However, if the part being pruned has moderate density, and is just considered low density because the residents are rich enough they never take the bus, then it’s likely to be useful for gig workers, and should when possible be retained, likely with no extra peak service, only base service.

Evidently, routes like that are sometimes understood to have this class of rider, though perhaps not in this language. This is most visible in suburban NIMBYism against buses: a number of middle-class American suburbs oppose the introduction of bus service that may be useful for regular riders, for fear that poor people might use it to get to their areas; in Massachusetts, those suburbs are fine with buses making one stop in the periphery of their town, triggering a paratransit mandate under the state’s interpretation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (in most states it’s within 0.75 miles, but in Massachusetts it’s town-wide), but oppose any further penetration by regular transit.

To be clear, most of the things that would disproportionately benefit gig workers also benefit the network writ large: faster buses with off-board fare collection and (in denser urban areas) bus lanes would make a great difference, and so would shifting service away from the peak. But the network design principles at granular enough a level to discuss pruning marginal routes really do differ, and it’s important to get this right and, at the very least, avoid empowering aggrieved rich people who hire maids and then do local activism to make it harder for their maids to get to their houses.

To be clear on another point, none of these reforms would make traveling to clean a randomly-selected apartment in a residential neighborhood pleasant. But they could, through smoother bus travel time and transfers, replace a 1.5-hour commute with a 1-1.25-hour one, which would make a significant, if not life-altering, improvement in the comfort levels as well as productivity (and thus pay) of gig workers. It mirrors many other egalitarian social interventions, in producing a moderate level of income and quality of life compression, rather than a change in the rank ordering by income.

What it Means That Miri Regev Wants to Cancel Congestion Pricing

Minister of Transportation Miri Regev is trying to cancel the Tel Aviv congestion pricing plan, slated to begin operations in 2026. Congestion pricing is still planned to happen, but 2026 is already behind schedule due to delays on past contracts required to set up the gantries. The plan is still to go ahead and use the revenue to help fund the Tel Aviv Metro project, to comprise three driverless metro lines at regional scale to complement both the longer-range commuter trains and the shorter-range Light Rail system, which opened last year with a subway segment after several decades of design and construction. But Regev has wanted to cancel it since she became transportation minister early last year, and her latest excuse is the war, never mind that usually during war one raises taxes and aims to restrain private consumption such as personal vehicle driving.

I bring this up partly to highlight that Regev has not been a good minister; the civil servants at the ministry quickly found that she routinely bypasses them, makes decisions purely with her own political team, and sometimes doesn’t even inform them before making public announcements. More recently, she’s been facing corruption investigations, since much of the above behavior is not legal in Israel, a country where one says “the state” with a positive connotation that exists in French and German but not in English.

But more than that, I bring this up to highlight the contrast between Regev and New York Governor Kathy Hochul, who outright canceled the New York congestion pricing plan last month on no notice, weeks before it was about to debut rather than years. At a personal level, Regev is a worse person than Hochul. But Regev’s ability to cause damage is constrained by far stronger state institutions. The cabinet can collectively decide to cancel congestion pricing, in the same way a state legislature could repeal its own laws, but that would involve extensive open debate within the coalition. Thus, the ministry of finance already said that if the ministry of transportation is bowing out, it will have to take over the program, since it’s necessary for financing the metro, which is still on-budget; the civil servants at finance have long drawn ire from populists over their control over the budget, called the Arrangements Law, and unless the metro is formally canceled, the money will have to come from somewhere.

A formal repeal is still possible, but it cannot be done on a whim. Netanyahu, an atypically monarchical prime minister in both power within the coalition and aspirations, might be able to swing it if he wants, but he’d still have to persuade coalition partners. His power derives from long-term deals with junior parties that are so widely loathed they feel like they have to stick with him, and from over time turning Likud into a party of personal loyalists; at the same time, he has to govern roughly within the spectrum of opinions of the loyalists, and while their opinions on the biggest issues facing the state align with his or else they would not be in this position, on issues like transportation they may have different opinions and express them. At no point does a loyalist like Regev get absolute control of one aspect of policy; the coalition gets a vote and absent a formal repeal, the legislation creating congestion pricing still binds.

In other words, Israel is a functioning multiparty parliamentary democracy, more or less. Mostly less these days, let’s be honest. But much of the “less” comes from a concerted attempt to politicize the civil service, which Regev is currently under investigation for. In the United States, it’s fully politicized; one governor can announce the cancellation of a legislatively mandated congestion pricing program on a whim, the MTA board (which she appointed) will affirm that she indeed can do it and will not sign a statement saying the state consents to congestion pricing, and the question of whether it’s legal will be deferred to courts where the judges were politically appointed based on governor-legislative chief deals. Israel can make long-term plans, and a minister like Regev can interfere with them, but would need to do a lot of work to truly wreck them. The United States, as we’re seeing with New York congestion pricing, really can’t.

Project 2025 and Public Transportation

The Republican Party’s Project 2025, outlining its governing agenda if it wins the election later this year, has been in the news lately, and I’ve wanted to poke around what it has to say about transportation policy, which hasn’t been covered in generalist news, unlike bigger issues. The answer is that, on public transportation at least, it doesn’t say much, and what it does say seems confused. The blogger Libertarian Developmentalism is more positive about it than I am but does point out that it seems to be written by people who don’t use public transit and therefore treat it as an afterthought – not so much as a negative thing to be defunded in favor of cars, but just as not a priority. What I’m seeing in the two pages the 922-page Project 2025 devotes to public transit is that the author of the transportation section, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, clearly read some interesting critiques but then applies them in a way that shows she didn’t really understand them, and in particular, the proposed solutions are completely unrelated to the problems she diagnoses.

What’s not in the report?

Project 2025 is notable not in what it says about public transit, but in what it doesn’t say. As I said in the lede, the 922-page Project 2025 only devotes slightly less than two pages to public transportation, starting from printed page 634. The next slightly more than one page is devoted to railroads, and doesn’t say anything beyond letting safety inspections be more automated with little detail. Additional general points about transportation that also apply to transit can be found on page 621 about grants to states and pp. 623-4 extolling the benefits of public-private partnerships (PPPs, or P3s). To my surprise, the word “Amtrak,” long a Republican privatization target, appears nowhere in the document.

There are no explicit funding cuts proposed. There are complaints that American transit systems need subsidies and that their post-pandemic ridership recovery has not been great. There is one concrete proposal, to stop using a portion of the federal gas tax revenue to pay for public transit, but then it’s not a proposal to use the money to fund roads instead in context of the rest of the transportation section. The current federal formula is that funds to roads and public transit are given in an 80:20 ratio between the two modes, which has long been the subject of complaints among both transit activists and anti-transit activists, and Project 2025 not only doesn’t side with the latter but also doesn’t even mention the formula or the possibility of changing it.

The love for P3s is just bad infrastructure construction; the analysis speaks highly of privatization of risk, which has turned entire parts of the world incapable of building anything. (Libertarian Developmentalism has specific criticism of that point.) But the section stops short of prescribing P3s or other mechanisms of privatization of risk. In this sense, it’s better than what I’ve heard from some apolitical career civil servants at DOT. In contrast, the Penn Station Reconstruction agreement among the agencies using the station explicitly states that the project must use an alternative procurement mechanism such as design-build, construction manager/general contractor, or progressive-design-build (which is what most of the world calls design-build), of which the last is illegal in New York but unfortunately there are attempts to legalize it. This way, Project 2025’s loose support for privatization of planning is significantly better than the actual privatization of planning seen in New York, ensuring it will stay incapable of building infrastructure.

This aspect of saying very little is not general to Project 2025, I don’t think. I picked a randomly-selected page, printed p. 346, which concerns education. There’s a title, “advance school choice policies,” which comprises a few paragraphs, but these clearly state what the party wants, which is to increase funding for school vouchers in Washington D.C., expanding the current program. Above that title is a title “protect parental rights in policy,” which is exclusively about opposing the rights of transgender children not to tell their parents they’re socially transitioning at school.

Okay, so what does Project 2025 say?

The public transit section of the report, as mentioned above, has little prescription, and instead complains about transit ridership. What it says is not even always true, regarding modal comparisons. For one, it gets the statistical definition of public transit in the United States wrong. Here is Project 2025 on how public transit is defined:

New micromobility solutions, ridesharing, and a possible future that includes autonomous vehicles mean that mobility options—particularly in urban areas—can alter the nature of public transit, making it more affordable and flexible for Americans. Unfortunately, DOT now defines public transit only as transit provided by municipal governments. This means that when individuals change their commutes from urban buses to rideshare or electric scooter, the use of public transit decreases. A better definition for public transit (which also would require congressional legislation) would be transit provided for the public rather than transit provided by a public municipality.

Leaving aside that the biggest public-sector transit agencies in the US are not municipal but state-run or occasionally county-run (in Los Angeles), the definition of public transit in federal statistics and funding is exactly what Project 2025 wants. There are private transit operators; the biggest single grouping is privately-operated buses in New Jersey running into Manhattan via the Lincoln Tunnel. These buses count as public transit in census commuting statistics; they have access to publicly-funded transit-only infrastructure including the Lincoln Tunnel’s peak-only Express Bus Lane (XBL) and Port Authority Bus Terminal.

What’s true is that rideshare vehicles aren’t counted as transit, but as taxis. Larger vanshare systems could count as public transit; the flashiest ones, like last decade’s Bridj in Boston and Chariot in San Francisco, were providing public transit privately, but went to great lengths to insist that they were doing something different.

Other complaints include waste, but as with the rest of this section, there isn’t a lot of detail. Project 2025 complains about the Capital Investment Grants (CIG) program, saying it leads to waste, but it treats canceling it as unrealistic and instead says “a new conservative Administration should ensure that each CIG project meets sound economic standards and a rigorous cost-benefit analysis.” In theory, I could read it as a demand that the FTA should demand benefit-cost analyses as a precondition of funding; current federal practices do not do so, and to an extent this can be blamed on changes in the early Obama administration. But the FTA is not even mentioned in this section, nor is there a specific complaint that American transit projects are federally funded based on vibes more than on benefit-cost analysis.

The two main asks as far as transit is concerned are about labor and grants to states.

On labor, the analysis is solid, and I can tell that the Project 2025 authors read some blue state right-wing thinktanks that do interface with the problems of transit agencies. Project 2025 correctly notes that transit worker compensation is driven by high fringe benefits and pensions but not wages; it’s loath to say “wages are well below competitive levels” but it does say “transit agencies have high compensation costs yet are struggling to attract workers.” So far, so good.

And then the prescribed solution, the only specific in the section, is to reinterpret a section of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 to permit transit agencies to reduce overall compensation, which is currently illegal. As a solution, it is unhinged: transit agencies are having trouble finding qualified hires, so reducing compensation is only going to make these problems worse. It doesn’t follow at all from Project 2025’s own analysis; what would follow is that agencies should shift compensation from benefits to cash pay, but that’s already legal, and at no point does Project 2025 say “we recommend that agencies shift to paying workers in cash and will legally and politically back agencies that do so against labor wishes,” perhaps with a mention that the Conservatives in the United Kingdom gave such support to rail operators to facilitate getting rid of conductors. There’s no mention of the problems of the seniority system. Furchtgott-Roth used to work at the Manhattan Institute, which talks about way more specific issues including backing management against labor during industrial disputes and how one could cut pensions, but this is nowhere in the report.

On grants to states, Project 2025 is on more solid grounds. It proposes on p. 621 that federal funding should be given to states by formula, to distribute as they see fit:

If funding must be federal, it would be more efficient for the U.S. Congress to send transportation grants to each of the 50 states and allow each state to purchase the transportation services that it thinks are best. Such an approach would enable states to prioritize different types of transportation according to the needs of their citizens. States that rely more on automotive transportation, for example, could use their funding to meet those needs.

American transit activists are going to hate this, because, as in Germany and perhaps everywhere else, they disproportionately use the public transit that most people don’t use. On pre-corona numbers, around 40% of transit commuters in the United States live in metropolitan New York, but among the activists, the New York share looks much lower than 40% – it’s lower than that in my social circle of American transit activists, and I lived in New York five years and founded a New York advocacy group. The advocates I know in Texas and Kentucky and Ohio are aware of their states’ problems and want ridership to be higher, but, at the end of the day, American transit ridership is not driven by these states. Texas is especially unfortunate in how, beyond Houston’s original Main Street light rail line, its investments have not been very good. Direct grants to states are likely going to defund such projects in the future, but such projects are invisible in overall US transit usage, unfortunately.

In the core states to US transit usage – New York, New Jersey, California, Massachusetts, Illinois, Washington, Pennsylvania – the outcome of such change would be to replace bad federal-state interactions with bad state politics. But then, to the extent that there’s a theme to the problems of Project 2025 beyond “they aren’t saying much,” it’s that it’s uninterested in solving competent governance problems in blue states, and essentially all of American public transit ridership today is about the poor quality of blue state governance.

What does this mean?

I’ve seen criticism of Project 2025 on left-wing social media (that is, Bluesky and Mastodon) that portrays it as evil. I haven’t read the document except for the transportation section and the aforementioned randomly-selected pair of pages, so I can’t judge fully, but on public transit, I’m not seeing any of this. I’m not seeing any clear defunding calls. I’m seeing a reference to anti-transit advocate Robert Poole, the director of transportation policy at Reason, but only on air traffic control; he’s written voluminously (and shoddily) about public transit, but Furchtgott-Roth isn’t referencing any of that.

What I am seeing is total passivity. Maybe it’s specific to Furchtgott-Roth, who I didn’t hear about before, and who just doesn’t seem to get transportation as an issue despite having served as a political appointee at USDOT. Or maybe, as Libertarian Developmentalism points out, it’s that the sort of people who’d write a Republican Party governing program don’t think about public transit very much and therefore resort to catechisms about reducing the role of the federal government and repealing a labor law that isn’t a binding constraint. Occasionally this can land on a proposal that isn’t uniformly bad, like granting money to states rather than projects; more commonly, it leads to misstating what the federal and state governments consider to be public transit. I’m not seeing anything nefarious here, but I am seeing a lot of ignorance and poor thinking about solutions.

Why is Kathy Hochul Against Masks on the Subway?

The New York City Subway is showing solidarity with Israel: like public transportation in Israel, it does not usefully run on weekends. Today, while going from my hotel to Marron, I waited 16 minutes for the F train, and when I got to the platform, there was already a small crowd there; the headway must have been 20 minutes. Now writing this on the way north to Queens, I’m seeing canceled trains and going through reroutes hoping that it’s possible to get from Marron to the Queens Night Market in under an hour; revising hours later, I now know it would have been but the 7 train is skipping the nearest stop to the Night Market, 111th Street.

This is on my mind as I see that Governor Kathy Hochul, after abruptly canceling congestion pricing in legally murky circumstances, wants to also ban wearing masks on the subway. I write this on a car where I’m the only person wearing a mask as far I can see, but usually I do see a handful of others who wear one like me or Cid. Hochul told the New York Post that Jewish groups asked her to do so citing security concerns, since some anti-Semitic rioters cover their faces. Jewish and pro-Israel groups have said no such thing, and I think it’s useful to bring this up, partly because it does affect the subway, and partly because it speaks to how bad Hochul’s political knowledge is that she would even say this.

Now, I don’t think the mask ban is going very far. For a few days, instead of getting constant constituent calls all the time demanding that congestion pricing be restored, legislators were getting such calls only half the time, and got calls demanding they oppose the mask ban the other half. Congestion pricing is likely not within Hochul’s personal authority to cancel, but evidently the MTA board did not overrule her and did not sign that the state consented to congestion pricing; but a mask ban is definitely not within her authority, certainly not when it would be new policy rather than status quo policy (if not status quo law, since congestion pricing did get signed into law).

That said, the invocation of Jewish or pro-Israel concerns was troubling, for a number of reasons, chief of which is that the groups so named did not in fact demand a subway mask ban. The Anti-Defamation League asked for a mask ban at protests, where the current left-wing American protest culture involves wearing masks but very rarely medical ones. Hochul cited unnamed Jewish advisors, when at no point has any significant element in the American Jewish community called for this. There are a number of possibilities, all of which are derogatory to her judgment, knowledge, or other political skills.

The first possibility is that she’s just lying. Nobody asked for this, not on the subway, and she’s trying to change the topic from her total failure on congestion pricing; a mask ban at protests alone, as proposed by Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass (at least before she just got corona), would not change the conversation on issues of public transportation.

The second is that she is using the ADL for cover because the ADL has little patience for anything it perceives as too left-wing, and Hochul wants to position herself as a moderate and her pro-congestion pricing opponents as too liberal. If that was the intent, then it’s dumb – subway advocacy is not at all radical, and the people spearheading both the lawsuit against Hochul and the rallies in favor of congestion pricing are neither anti-Israel nor baitable on this subject.

And the third is that she internalized a kind of conspiratorial anti-Semitism; she doesn’t weaponize it against Jews like properly anti-Semitic politicians, but a politician from Buffalo, thrust into a stage with different demographics from what she’s used to, might still believe, in the back of her mind, that Jews are conspiring and say things they do not mean. It’s complete hogwash – pro-Israel groups are open about who they are and what they want, and have little trouble calling for changes that they think are necessary for the protection of the great majority of American Jews who are at least somewhat pro-Israel. They have no need to whisper in a governor’s ear and every reason to call for such a ban in the open if they believe it is good; that they haven’t should end any suspicion that they want it.

In any of the above cases, the inevitable conclusion is that Hochul knows neither how to govern nor how to do politics effectively. She can’t distract the public from her own inability to run the state, certainly not by piling one failure upon another.

Quick Note on Respecting the Civil Service

The news about the congestion pricing cancellation in New York is slowing down. Governor Hochul is still trying to kill it, but her legal right to do so at this stage is murky and much depends on actors that are nominally independent even if they are politically appointed, especially New York State Department of Transportation Commissioner Marie Therese Dominguez. I blogged and vlogged about the news, and would like to dedicate this post to one issue that I haven’t developed and barely seen others do: the negative effect last-minute cancellations have on the cohesion of the civil service.

The problem with last-minute cancellations is that they send messages to various interest groups, all of which are negative. My previous blog post went over the message such caprice sends to contractors: “don’t do business with us, we’re an unreliable client.” But the same problem also occurs when politicians do this to the civil service, which spent years perfecting these plans. I previously wrote about the problem with Mayor Eric Adams last-minute canceling a bike lane in Brooklyn under pressure, but what Hochul is doing is worse, because there was no public pressure and the assumption until about 3.5 days ago was that congestion pricing was a done deal.

With the civil service, the issue is that people are remunerated in both money and the sense of accomplishment. Industries and companies with a social mission have been able to hire workers at lower pay, often to the point of exploitation, in which managers at NGOs tell workers that they should be happy to be earning retail worker wages while doing professional office work because it’s for the greater good. But even setting aside NGOs, a lot of workers do feel a sense of professional accomplishment even when what they do is in a field general society finds boring, like transportation. One civil servant in the industry, trying to encourage an activist to go into the public sector, said something to the effect that it takes a really long time to get a reform idea up the hierarchy but once it happens, the satisfaction is great; the activist in question now works for a public transit agency.

Below the threshold of pride in one’s accomplishments, there is the more basic issue of workplace dignity. Workers who don’t feel like what they do is a great accomplishment still expect not to be berated by their superiors, or have their work openly denigrated. This is visible in culture in a number of ways. For example, in Mad Men, the scene in which Don Draper won’t even show a junior copywriter’s idea to a client has led to the famous “I don’t think about you at all” meme. And in how customers deal with service workers, ostentatiously throwing the product away in front of the worker is a well-known and nasty form of Karenish disrespect.

What Hochul did – and to an extent what Adams did with the bike lane – was publicly throwing the product that the state’s workers had diligently made over 17 years on the floor. A no after years of open debate would be frustrating, but civil servants do understand that they work for elected leaders who have to satisfy different interest groups. A no that came out of nowhere showcases far worse disrespect. In the former case, civil servants can advocate for their own positions with their superiors; “If we’d played better we would have won” is a frustrating thing to come to believe in any conflict, from sports to politics, but it’s understandable. But in the latter case, the opacity and suddenness both communicate that there’s no point in coming up with long-term plans for New York, because the governor may snipe them at any moment. It’s turning working for a public agency into a rigged game; nobody enjoys playing that.

And if there’s no enjoyment or even basic respect, then the civil service will keep hemorrhaging talent. It’s already a serious problem in the United States: private-sector wages for office workers are extremely high (people earning $150,000 a year feel not-rich) and public-sector wages don’t match them, and there’s a longstanding practice by politicians and political appointees to scorn the professionals. It leaves the civil service with the dregs and the true nerds, and the latter group doesn’t always rise up in the hierarchy.

Such open contempt by the governor is going to make this problem a lot worse. If you want to work at a place where people don’t do the equivalent of customers taking the coffee you made for them and deliberately spilling it on the floor while saying “I want to speak to the manager,” you shouldn’t work for the New York public sector, not right now. I’ll revise my career recommendation if Dominguez and others show that the governor was merely bloviating but the state legislature had passed the law mandating congestion pricing and the governor had signed it. I expect this recommendation will be echoed by others as well, judging by the sheer scorn the entire transportation activist community is heaping on Hochul and her decision – even the congestion pricing opponents don’t trust her.

Hochul Suspends Congestion Pricing

New York Governor Kathy Hochul just announced that she’s putting congestion pricing on pause. The plan had gone through years of political and regulatory hell and finally passed the state legislature earlier this year, to go into effect on June 30th, in 25 days. There was some political criticism of it, and lawsuits by New Jersey, but all the expectations were that it would go into effect on schedule. Today, without prior warning, Hochul announced that she’s looking to pause the program, and then confirmed it was on hold. The future of the program is uncertain; activists across the region are mobilizing for a last-ditch effort, as are suppliers like Alstom. The future of the required $1 billion a year in congestion pricing revenue is uncertain as well, and Hochul floated a plan to instead raise taxes on businesses, which is not at all popular and very unlikely to happen.

So last-minute is the announcement that, as Clayton Guse points out, the MTA has already contracted with a firm to provide the digital and physical infrastructure for toll collection, for $507 million. If congestion pricing is canceled as the governor plans, the contract will need to be rescinded, cementing the MTA’s reputation as a nightmare client that nobody should want to work with unless they get paid in advance and with a risk premium. Much of the hardware is already in place, hardly a sign of long-term commitment not to enact congestion pricing.

Area advocates are generally livid. As it is, there are questions about whether it’s even legal for Hochul to do so – technically, only the MTA board can decide this. But then the governor appoints the MTA board, and the appointments are political. Eric is even asking about federal funding for Second Avenue Subway, since the MTA is relying on congestion pricing for its future capital plans.

The one local activist I know who opposes congestion pricing says “I wish” and “they’ll restart it the day after November elections.” If it’s a play for low-trust voters who drive and think the additional revenue for the MTA, by law at least $1 billion a year, will all be wasted, it’s not helping. The political analysts I’m seeing from within the transit advocacy community are portraying it as an unforced error, making Hochul look incompetent and waffling, rather than boldly blocking something that’s adverse to key groups of voters.

The issue here isn’t exactly that if Hochul sticks to her plan to cancel congestion pricing, there will not be congestion pricing in New York. Paris and Berlin don’t have congestion pricing either. In Paris, Anne Hidalgo is open about her antipathy to market-based solutions like congestion pricing, and prefers to reduce car traffic through taking away space from cars to give to public transportation, pedestrians, and cyclists. People who don’t like it are free to vote for more liberal (in the European sense) candidates. In Berlin, similarly, the Greens support congestion pricing (“City-Maut”), but the other parties on the left do not, and certainly not the pro-car parties on the right. If the Greens got more votes and had a stronger bargaining position in coalition negotiations, it might happen, and anyone who cares in either direction knows how to vote on this matter. In New York, there has never been such a political campaign. Rather, the machinations that led Hochul to do this, which people are speculating involve suburban representatives who feel politically vulnerable, have been entirely behind the scenes. There’s no transparency, and no commitment to providing people who are not political insiders with consistent policy that they can use to make personal, social, or business plans around.

Everything right now is speculation, precisely because there’s neither transparency nor certainty in state-level governance. Greg Shill is talking about this in the context of suburban members of the informal coalition of Democratic voters; but then it has to be informal, because were it formal, suburban politicians could have demanded and gotten disproportionately suburb-favoring public transit investments. Ben Kabak is saying that it was House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries who pressed Hochul for this; Jeffries himself said he supports the pause for further study (there was a 4,000 page study already).

The chaos of this process is what plays to the impression that the state can’t govern itself; Indignity mentions it alongside basic governance problems in the city and the state. This is how the governor is convincing anti-congestion pricing cynics that it will be back in November and pro-congestion pricing ones that it’s dead, the exact opposite of what she should be doing. Indecision is not popular with voters, and if Hochul doesn’t understand that, it makes it easy to understand why she won New York in 2022 by only 6.4%, a state that in a neutral environment like 2022 the Democrats usually win by 20%.

But it’s not about Hochul personally. Hochul is a piece of paper with “Democrat” written on it; the question is what process led to her elevation for governor, an office with dictatorial powers over policy as long as state agencies like the MTA are involved. This needs to be understood as the usual democratic deficit. Hochul acts like this because this signals to insiders that they are valued, as the only people capable of interpreting whatever is going on in state politics (or city politics – mayoral machinations are if anything worse). Transparency democratizes information, and what Hochul is doing right now does the exact opposite, in a game where everyone wins except the voters and the great majority of interests who are not political insiders.

American Myths of European Poverty

I occasionally have exchanges on social media or even in comments here that remind me that too many people in the American middle class believe that Europe is much poorer than the US. The GDP gap between the US and Northern Europe is small and almost entirely reducible to hours worked, but the higher inequality in the US means that the top 10-20% of the US compare themselves with their peers here and conclude that Europe is poor. Usually, it’s just social media shitposting, for example about how store managers in the US earn the same as doctors in Europe. But it becomes relevant to public transit infrastructure construction in two ways. First, Americans in positions of authority are convinced that American wages are far higher than European ones and that’s why American construction costs are higher than European ones. And second, more broadly, the fact that people in positions of authority really do earn much more in the US than here inhibits learning.

The income gap

The United States is, by a slight amount, richer than Northern Europe, which for the purposes of this post comprises the German-speaking world, the Nordic countries, and Benelux. Among the three largest countries in this area, Germany is 16.5% poorer than the US, the Netherlands 8.3% poorer, Sweden 14.3%. This is more than anything an artifact of shorter working hours – Sweden has an ever so slightly larger GDP per hour worked, the other two are 6-7% poorer per hour worked. All three countries have a much higher 15-64 labor force participation rate than the US, but they’re also older, which in the case of Germany actually gets its 15+ rate to be a hair less than the US’s. But there’s much more part-time work here, especially among women, who face large motherhood penalties in German society (see figures 5-7 in Herzberg-Druker, and Kleven et al). Germany is currently in full employment, so it’s not about hidden part-time work; it’s a combination of German-specific sexism and Europe-wide norms in which workers get around six weeks of paid vacation per year.

One implication of the small gap in income per hour is that wages for the same job are likely to be similar, if the jobs pay close to the mean wage. This is the case for tunnel miners, who are called sandhogs in the United States: the project labor agreements in New York are open – the only case in which itemized costs are publicly available – and showcase fully-laden employment costs that, as we document in our construction costs reports, work out to around $185,000/year in 2010 prices; there is a lot of overstaffing in New York and it’s disproportionately in the lower-earning positions, and stripping those, it’s $202,000/year. I was told that miners in Stockholm earn 70,000 kronor/month, or about $100,000/year in PPP terms (as of 2020-1), and the fully-laden cost is about twice that; a union report from the 2000s reports lower wages, but only to about the same extent one would expect from Sweden’s overall rate of economic growth between then and 2021. The difference at this point is second-order, lower than my uncertainty coming from the “about” element out of Sweden.

While we’re at it, it’s also the case for teachers: the OECD’s Education at a Glance report‘s indicator D3 covers teacher salaries by OECD country, and most Northern European countries pay teachers better than the US in PPP terms, much better in the case of Germany. Teacher wage scales are available in New York and Germany; the PPP rate is at this point around 1€ = $1.45, which puts starting teachers in New York with a master’s about on a par with their counterparts in the lowest-paying German state (Rhineland-Pfalz). New York is a wealthy city, with per capita income somewhat higher than in the richest German state (Bavaria), but it’s not really seen in teacher pay. I don’t know the comparative benefit rates, but whenever we interview people about European wage rates for construction, we’re repeatedly told that benefits roughly double the overall cost of employment, which is also what we see in the American public sector.

The issue of inequality

American inequality is far higher than European inequality. So high is the gap that, on LIS numbers, nearly all Western European countries today have lower disposable income inequality than the lowest recorded level for the US, 0.31 in 1980. Germany’s latest number is 0.302 as of 2021, and Dutch and Nordic levels are lower, as low as 0.26-0.27; the US is at 0.391 as of 2022. If distributions are log-normal (they only kind of are), then from a normal distribution log table lookup, this looks like the mean-to-median income ratios should be, respectively, 1.16 for Germany and 1.297 for the US.

However, top management is not at the median, and that’s the problem for comparisons like this. The average teacher or miner makes a comparable amount of money in the US and Northern Europe. The average private consultant deciding on how many teachers or miners to hire makes more money in the US. A 90th-percentile earner is somewhat wealthier in the US than here, again on LIS number; the average top-1%er is, in relative terms, 50% richer in the US than in Germany (and in absolute terms 80% richer) and nearly three times as rich in the US as in Sweden or the Netherlands, on Our World in Numbers data.

On top of that, I strongly suspect that not all 90th percentile earners are created equal, and in particular, the sort of industries that employ the mass (upper) middle class in each country are atypically productive there and therefore pay better than their counterparts abroad. So the average 90th-percentile American is noticeably but not abnormally better off than the average 90th-percentile German or Swede, but is much better off than the average German or Swede who works in the same industries as the average 90th-percentile American. Here we barely have a tech industry by American standards, for example; we have comparable biotech to the US, but that’s not usually where the Americans who noisily assert that Europe is poor work in.

Looking for things to mock

While the US is not really richer than Northern Europe, the US’s rich are much richer than Northern Europe’s. But then the statistics don’t bear out a massive difference in averages – the GDP gap is small, the GDP gap per hour worked is especially small and sometimes goes the other way, the indicators of social development rarely favor the US, immigration into Western Europe has been comparable to immigration to the US for some time now (here’s net migration, and note that this measure undercounts the 2022 Ukrainians in Germany and overcounts them in Poland).

So middle-class Americans respond by looking for creative measures that show the level of US-Europe income gap that they as 90th-percentile earners in specific industries experience (or more), often dropping the PPP adjustment, or looking at extremely specific things that are common in the US but not here. I’ve routinely seen American pundits who should know better complain that European washing machines and driers are slow; I’m writing this post during a 4.5-hour wash-and-dry cycle. Because they fixate on proving the superiority of the United States to the only part of the world that’s rich enough not to look up to it, they never look at other measures that might show the opposite; this apartment is right next to an elevated train, but between the lower noise levels of the S-Bahn, good insulation, and thick tilt-and-turn windows, I need to concentrate to even hear the train, and am never disturbed by it, whereas American homes have poor sound insulation to the point that street noise disturbs the sleep.

Learning to build infrastructure

The topline conclusion of any American infrastructure reform should be “the United States should look more like Continental Europe, Turkey, non-Anglophone East Asia, and the better-off parts of Latin America.”