Category: Good/Interesting Studies

Transfer Penalty Followup

My previous post‘s invocation of Reinhard Clever’s lit review of transfer penalties was roundly criticized on Skyscraper City Page for failing to take into account special factors of the case study. Some of the criticism is just plain mad (people don’t transfer from the Erie Lines to the NEC because trains don’t terminate at Secaucus the way they do at Jamaica?), but some is interesting:

This is what the paper says:

Go Transit commuter rail in Toronto provides a good example for Hutchinson’s findings. In spite of being directly connected to one of the most efficient subway systems in North America, Go’s ridership potential is limited to the number of work locations within an approximately 700 m radius around the main railroad station. Most of the literature points to the fact that the ridership already drops off dramatically beyond 400 m. This phenomenon is generally referred to as the “Quarter Mile Rule.”

Let’s look at WHY that is. If you live North of downtown and work North of about Dundas Street, it is probably faster for you to take the subway to work. So people aren’t avoid the commuter train because it imposes a transfer, but just because the subway is faster. Same thing if you live along the Bloor-Danforth line. Toronto’s subway runs at about the same average speed as NYC’s express trains. If one lives east or west of the city along the lakeshore, they are going to take the GO Train to Union Station and transfer to the subway to reach areas north of Dundas. I really doubt these people are actually “avoiding” the GO Train, though if there is evidence to the contrary I’d like to see it.

Toronto also has higher subway fares than NYC.

The issue is whether the subway and commuter rail in Toronto are substitutes for each other. My instinct is to say no: on each GO Transit line, only the first 1-3 stations out of Union Station are in the same general area served by the subway, and those are usually at the outer end of the subway, giving GO an advantage on time. Although the Toronto subway is fast for the station spacing, it’s only on a par with the slower express trains in New York; on the TTC trip planner the average speed on both main subway lines is about 32 km/h at rush hour and 35 km/h at night.

Unfortunately I don’t know about GO Transit usage beyond that. My attempt to look for ridership by station only yielded ridership by line, which doesn’t say much about where those riders are coming from, much less potential riders allegedly deterred by the transfer at Union Station. So I yield the floor to Torontonians who wish to chime in.

Update: a kind reader sent me internal numbers. The busiest stations other than Union Station are the suburban stations on the Lakeshore lines, led by Oakville, Clarkson, and Pickering; the stations within Toronto, especially subway-competitive ones such as Kipling, Oriole, and Kennedy, are among the least busy. Some explanations: the subway is cheaper, and (much) more frequent; Toronto’s GO stations have no bus service substituting rail service in the off-peak, whereas the suburban stations do; Toronto’s stations have little parking.

Congestion, Freeways, and Size, Redux

As a followup to my previous post about the TTI’s new congestion report, I finally did a multivariate regression analysis, with the dependent variable being cost and the independent variables being size and freeway lane-miles per capita. Such an analysis reduces the regression coefficient between freeways and congestion even more, to -42.5 from the uncontrolled -233. More interestingly, if we log all numbers (population, congestion cost, and freeways), the regression coefficient becomes a positive 0.02 – that is, adding freeways is correlated with making congestion a little worse.

Of course, it’s not literally true that adding freeways makes congestion worse. There’s a correlation if we look at the variables in some way, but it’s not going to have any statistical significance. Therefore tweaking variables slightly can make a correlation go from weakly positive to weakly negative.

In univariate regression, we can think about the square of the correlation as the percentage of the variance that is explained by the regression line. Freeway lane-miles per capita explain 3.8% of the variance in congestion (and logging either variable makes this number smaller); with 101 urban areas surveyed, it’s statistically significant, but barely so. But after controlling for population, this proportion drops to 0.7%. Thus, any sentence of the form “adding one freeway lane-mile per thousand people only cuts $42.5 from the annual congestion cost per capita” is inherently misleading: the correlation is so weak that some cities can reduce congestion without building the requisite amount of roads, or building any roads at all (for example, nearly all American cities in the last five years, congestion having crashed in the oil price boom and the recession), while others can keep building but see congestion increase (for example, Houston since the 1980s, and even today).

It goes without saying that such analysis is not going to appear in the TTI report itself. The TTI gets funding from APTA and the American Road and Transportation Builders Association. It pays lip service to congestion pricing as a solution to congestion, and instead talks a lot about building public transportation and even more about building freeways to keep up with demand. American cities may be building freeways faster than their population growth, but cities that enact no traffic restraint and just pour concrete can expect demand to grow faster than population as people become more hypermobile.

Congestion and Size

The Texas Transportation Institute has just released the latest version of its much-criticized Urban Mobility Report. Although the conclusions and recommendations made by the TTI tend to reflect its funding sources (APTA, American Road and Transportation Builders Association), the underlying data seems sound, and suggests conclusions orthogonal to those made by the report. In addition, looking at the correlations more closely suggests obvious hazards coming from any simplistic analysis of linear regression. It even showcases how we could use data dishonestly and lie with statistics. So let’s take the data that’s relevant right now and see what we can conclude ourselves.

First, the size of an urban area is a very strong correlate of its level of congestion. The linear correlation between size and per capita congestion cost is 0.71. The correlation increases to 0.8 if we take the log of population and the log of congestion, or if we consider congestion in the absence of public transportation; in both cases, it comes from the fact that New York is far below the population-congestion regression line.

Now, more freeways do not really lead to congestion reduction. There’s some correlation between freeway miles per capita and congestion per capita, going in the expected direction, but it’s weak, -0.2, and while it’s statistically significant, the p-value is an uninspiring one-tailed 0.025. Looking at a scattergram doesn’t make any nonlinear relationship obvious.

Moreover, size is a correlate of both congestion (0.71 as above) and freeways (-0.23). This is fully expected: literature on cities’ economies of scale (here is a story of one controversial example) suggests that congestion and the economic activity causing it grow faster than linearly in city size while the amount of required energy and infrastructure grows slower than linearly. I open the floor to anyone with more powerful tools than OpenOffice Calc to do multiple regression; again, the sanitized data is here.

Even without controlling for population, freeways are not a very strong correlate. The regression coefficient is -233: increasing the number of freeway miles per thousand people by 1 (the range is 0.13-1.4, with few large metros above 1 or below 0.35) reduces the congestion cost per capita by $233 per year, also uninspiring.

The regression number alone can be used as a dishonest trick when arguing on the Internet. If we overinterpret weak correlations, we can declare that the only way to decrease congestion is to build an unrealistic number of freeways, and thus declare the problem unsolvable. Of course, for most cities we can find other cities of comparable size with much less congestion and without enormous amounts of asphalt – this is why the correlation is so weak. But a good hack should not bother himself with such caveats to talking points.

So if making an urban area larger makes it more congested, independently of and much more strongly than all else, should we give up on cities? Well, no. Assuming no change in traffic policy, congestion results from more economic activity. It then becomes straightforward to institute congestion pricing. It’s no different from how big cities can use their resources to hire more cops to deal with the crime that could result from extra interactions between people. On top of this, in very large cities, mass transit becomes a serious option: this not only reduces the amount of congestion per capita, but also removes many people from the highways to the point that congestion becomes irrelevant to their daily lives, except perhaps through higher transportation prices, which they can fully afford given the extra wealth.

Another thing to consider is that most American cities have added more freeways than people since 1982, the first year for which TTI data is available, while also becoming much more congested. If a simple relationship between freeway miles per capita and congestion held, it would be robust to these changes over time. Of course, traffic has grown even faster, leading the main report to showcase on PDF-page 21 how congestion increased the fastest in regions where road demand outgrew supply the most. But this raises the question of whether the main issue is one of demand, rather than one of supply. This is not just an issue of size: the log-log regression coefficients with cost and time is 0.42, i.e. doubling an urban area’s population will raise its per-driver congestion cost and travel delay by a factor of 2^0.42; since 1982, the average urban area on the list has seen its population grow by a factor of 1.46 and its travel delay per driver grow by a factor of 2.85 = 1.46^2.77. Cost has grown even faster, because of higher value of time.

That said, quantity of freeways does not equal quality (from the drivers’ perspective, of course, rather than the city’s). On paper, Greater New York has added freeway lanes about 9% faster than people over the last thirty years. In practice, none has addressed the major chokepoints within and into the city itself, where traffic is worst. Of course, commutes involving Manhattan are overwhelmingly likely to be done on public transportation, but diagonal commutes within the city are more likely to be done by car than on transit.

On a parenthetical note, the units of comparison here are TTI-defined urban areas. TTI’s belief about urban area population growth trends is sometimes at odds with that of the Census Bureau, but the raw population numbers are close enough. More important is the question of what to do about urban areas that are really exurbs of larger areas, such as Poughkeepsie-Newburgh and the Inland Empire. My first instinct was to lump them in with their core metro areas, but their congestion level per capita is not high. Their commutes are long, but not very congested for their size. Finally, although most correlations here are with congestion cost, the correlation numbers with travel delay and excess fuel consumptions are very similar; the one exception I’ve checked, for which I have no explanation, is log-log congestion-fuel correlation (0.84, with regression coefficient 0.73).

Disappointment 2050

The political transit bloggers are talking about the new RPA/America 2050 report on high-speed rail published by the Lincoln Institute, which recommends a focus on the Northeast and California. Unfortunately, this is not an accurate description of the report. Although it does indeed propose to start with the Northeast and California, that’s not the focus of the report; instead, the focus is to argue that HSR is everything its boosters claim it is and then some more, and demand more money for HSR, from whatever source.

Look more closely at the section proposing to focus on New York and California. Although the authors say the US should prioritize, minimal argument was offered for why these are the best options. The report shows the map from the RPA’s study on the subject, which proposes a few other priorities and isn’t that good to begin with (it grades cities on connecting transit based on which modes they have, not how much they’re used). But it says nothing more; I’d have been interested to hear about metro area distribution questions as discussed on pages 113-5 in Reinhard Clever’s thesis and pp. 10-11 of his presentation on the same topic, and alignment and regional rail integration questions such as those discussed by the much superior Siemens Midwest study, but nothing like that appears in this report.

The report then pivots to the need to come up with $40 billion for California and $100 billion for the Northeast Corridor, under either the RPA’s gold-plated plan or Amtrak’s equally stupid Vision. The RPA first came up with the idea of spending multiple billions on brand new tunnels under Philadelphia, which was then copied by the Vision, and wants trains to go through Long Island to New Haven through an undersea tunnel. Clearly, cost-effectiveness is not the goal. Since the methodology of finding the best routes is based on ridership per km, offering a gold-plated plan is the equivalent of trying to connect much longer distances without a corresponding increase in ridership, which goes against the original purpose of the RPA study.

Together with the neglect of corridors that scored high on the RPA’s study but have not had official high-speed rail proposals costing in the tens of billions (the SNCF proposal and the above-mentioned Siemens report are neither official nor affiliated with the RPA), the conclusion is not favorable. The most charitable explanation is that the RPA was looking for an official vehicle to peddle its own Northeast HSR plan but actually believes it has merit. The least charitable is that the RPA wants to see spending on HSR megaprojects regardless of cost-effectiveness.

The treatment of other issues surrounding HSR is in line with a booster mentality, in which more is always better. Discussing station placement, the report talks about the development benefits that come from downtown stations and the lack of benefit coming from exurban stations, as nearly all stations on LGVs are. It does not talk about the tradeoff in costs and benefits; others have done so, for example the chief engineer of Britain’s High Speed 2, who also talks about other interesting tradeoffs such as speed versus capacity versus reliability, but the report prefers to just boost the most expensive plan.

More specifically, the report contrasts CBD stations, suburban stations, and exurban stations. In reality, many stations are outside the CBD but still in the urban core with good transit connections, such as Shin-Osaka, Lyon Part-Dieu, and 30th Street Station, but those are implicitly lumped with beet field stations. This helps make spending billions on tunnels through Philadelphia, as both the RPA and Amtrak propose, look prudent, when in reality both Japan and France are happy to avoid urban tunneling and instead build major city stations in conveniently urban neighborhoods. In fact, Japan’s own boosters and lobbyists crow about the development around such stations.

In line with either view of the report’s purpose, the literature it studies is partial. Discussing the effect of HSR on development, it quotes a study about the positive effect of HSR on small towns in Germany on the Cologne-Frankfurt line, but not other studies done in other countries. For example, in Japan, the effect of the Shinkansen on the Tohoku and Joetsu regions was decidedly mixed. The report also quotes the positive story of Lille’s TGV-fueled redevelopment, which was not replicated anywhere else in France, where cities just passively waited for infrastructure to rescue them. But instead of talking about Lille’s program of redevelopment, the report contrasts it with failed development cases in cities with exurban stations, never mind that no city achieved what Lille did, even ones with downtown stations, like Marseille. It’s not quite a Reason-grade lie, but it’s still very misleading.

Finally, the section about how to fund the $100 billion Northeast system and California’s $43 billion starter line has suggestions that are so outlandish they defy all explanation. The authors propose the following:

1. Raise the gas tax by 15 cents a gallon or more. Several cents could be devoted to passenger rail.

2. Add a $1 surcharge on current passenger rail tickets to produce approximately $29 million annually.

3. Shift from a national gas tax to a percentage tax on crude oil and imported refined petroleum products. RAND estimated that an oil tax of 17 percent would generate approximately $83 billion a year. Five billion dollars of this amount could be dedicated to passenger rail.

Of these, proposal #2 is by far the stupidest. Amtrak receives subsidies; to tax tickets is to propose shifting some change from the left pocket to the right pocket. Why not go ahead and propose to reduce Amtrak’s subsidy by the same amount and require it to raise fares or improve efficiency?

But proposals #1 and 3 are equally bad. Wedding train funding to a steady stream of gas taxes has been the status quo for decades; the result is that APTA is so used to this unholy marriage that it opposed a climate change bill that would tax gas without diverting the funds back to transportation. (That by itself should be reason for good transit advocates to dismiss APTA as a hostile organization, just one degree less malevolent than Reason and Cato and one degree less obstructionist than the FRA.) And if it were a wise long-term choice, if it were politically feasible to add to the gas tax just to build competing trains, the US political climate would look dramatically different, and instead of talking about focus, we’d be talking about how to extend the under-construction Florida HSR line.

A report that was serious about a mode shift from cars to cleaner forms of transportation would not talk about 15 cents per gallon; it would talk in terms of multiple dollars per gallon, as gas is taxed in Europe and high-income Asia. The best explanation I can think of for the funding mechanisms is that the RPA has internalized the tax-as-user-fee model of ground transportation, one that has never worked for cars despite the AAA’s pretense otherwise and that won’t work for anything else.

The overall tone of the report slightly reminds me of Thomas MacDonald’s Highway Education Board, with its industry-sponsored “How Good Roads Help the Religious Life of My Community” essay contests. It reminds me of Thomas Friedman’s “win, win, win, win, win” columns even more – which is unsurprising since I think of Friedman as the archetypal booster – but when this boosterism applies not to a policy preference but to spending very large amounts of public money, I begin to suspect that it’s advertising rather than optimism. Friedman for all his faults crows about American and Indian entrepreneurs inventing new things rather than about extracting $100 billion from the Northeast to pay for unnecessary greenfield tunneling.

Therefore, good transit activists should dismiss this report, and avoid quoting it as evidence that prioritizing is necessary. This was not what the RPA was preaching back when it thought it could get away with proposing more, and the rest of the report is so shoddy it’s not a reliable source of analysis. There may be other reasons to focus on those corridors, but the RPA did not argue them much, instead preferring to literally go for big bucks.

Quick Note: Comfort

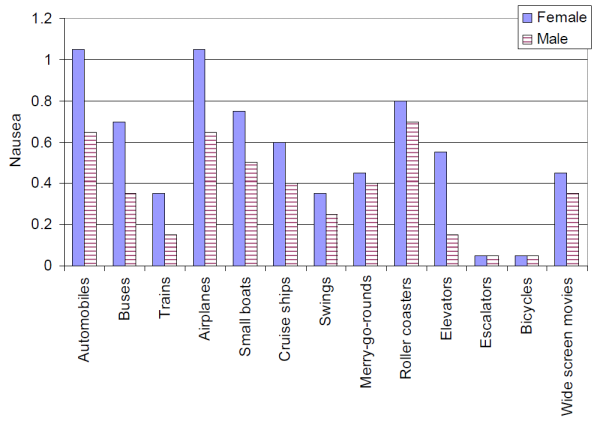

While reading a thesis about tilting trains, I saw a comparison of passenger comfort on different modes of transportation. This includes the following graph (p. 30), which the thesis sources to a study of motion sickness in US children and teenagers:

The scale is originally 0-3: this study polled a sample aged 9-18 and asked whether they feel nauseous on any of the above modes, where 0 is “never” and 3 “always.”

Selective Application of Smeed’s Law

A few months ago, in response to the Raquel Nelson case, author Tom Vanderbilt found an FHWA study from 2005 that finds that on wide, busy roads, pedestrian death rates are higher on marked crosswalks than on unmarked ones. The study itself is worth reading; its explanation of the finding is that,

These results may be somewhat expected. Wide, multilane streets are difficult for many pedestrians to cross, particularly if there is an insufficient number of adequate gaps in traffic due to heavy traffic volume and high vehicle speed. Furthermore, while marked crosswalks in themselves may not increase measurable unsafe pedestrian or motorist behavior (based on the Knoblauch et al. and Knoblauch and Raymond studies) one possible explanation is that installing a marked crosswalk may increase the number of at-risk pedestrians (particularly children and older adults) who choose to cross at the uncontrolled location instead of at the nearest traffic signal.

An even greater percentage of older adults (81.3 percent) and young children (76.0 percent) chose to cross in marked crosswalks on multilane roads compared to two-lane roads. Thus, installing a marked crosswalk at an already undesirable crossing location (e.g., wide, high-volume street) may increase the chance of a pedestrian crash occurring at such a site if a few at-risk pedestrians are encouraged to cross where other adequate crossing facilities are not provided. This explanation might be evidenced by the many calls to traffic engineers from citizens who state, “Please install a marked crosswalk so that we can cross the dangerous street near our house.” Unfortunately, simply installing a marked crosswalk without other more substantial crossing facilities often does not result in the majority of motorists stopping and yielding to pedestrians, contrary to the expectations of many pedestrians.

This is a rather standard application of Smeed’s law and similar rules governing traffic, whose one-line form is that traffic fatalities are determined primarily by psychology. This is not a problem; the problem is why such issues are only ever brought up in case of pedestrian fatalities.

In 1949, R. J. Smeed found a simple explanation for traffic fatalities: they depend less-than-linearly on the number of cars on the road. In the 1980s John Adams revised this to a more accurate rule based on VMT rather than the number of cars, and based on a constant decline in per-VMT accidents over time. Safety improvements do not bend or break the general trend. Quoting Adams again, the introduction of seat belts caused no reduction in traffic fatalities, and on the contrary caused pedestrian fatalities to temporarily inch up, as drivers felt safer and drove more recklessly. The only way to reduce the number of car accident victims is to reduce traffic.

And yet, government reaction is consistently on the side of accepting Smeed’s law when it implies there’s no need to improve pedestrian facilities, and rejecting it when its implication is bad for cars or good for pedestrians and cyclists. Local governments in the US routinely argue that safety is at stake when they want to upgrade a road with grade crossings into a full freeway. The FHWA helpfully adds that intersections are responsible to half of all car crashes and “FHWA will identify the most common and severe problems and compile information on the applications and design of innovative infrastructure configurations and treatments.”

In reality, all building freeways does is create more traffic, and cause more people to die in crashes. The average per-VMT death rate in the US has declined by 3.3% per year, but in the years following the Interstate Highway Act, it was practically flat – in other words, building freeways did nothing to accelerate the trend for reduction in per-VMT accident deaths. Although an individual freeway is undoubtedly safer than an individual road with intersections, the road network has to be viewed as a system: increase safety in one area and people will drive more recklessly elsewhere.

This systemwide view is clearly present in the case of pedestrians: the FHWA isn’t claiming that crosswalks are inherently unsafe, only that they cause more at-risk pedestrians to cross. In other words, the problem is that they cause too many of the wrong kind of pedestrians to cross. The implication is never used for roads. Traffic is never treated as variable, and if people shoot down freeway upgrades on the grounds that they’ll induce more traffic, it’s always on environmental or community grounds rather than on safety grounds.

Cost Overruns: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Hate Bent Flyvbjerg

Let me preface this post by saying I have nothing against Bent Flyvbjerg or his research. My problem is purely with how it’s used in the public media, and frequently even in other academic studies, which assume overruns take place even when they do not.

Stephen Smith sent me a link to an article in The Economist complaining about cost overruns on the California HSR Central Valley segment. The article gets its numbers wrong – for one, the original cost estimate for Merced-Bakersfield was never $6.8 billion, but instead was $7.2 billion in 2006 dollars and $8 billion in YOE dollars, according to CARRD, and as a result it portrays a 25% overrun as a 100% overrun. But the interest is not the wrong numbers, but the invocation of Flyvbjerg again.

Nowhere does the article say anything about actual construction costs – it talks about overruns, but doesn’t compare base costs. It’s too bad; Flyvbjerg himself did a cost comparison for rapid transit, on the idea that the only way to reliably estimate costs ex ante is to look at similar projects’ ex post costs. His paper has some flaws – namely, the American projects he considers are older than the European projects, and there’s no systematic attempt at controlling for percentage of the line that’s underground, both resulting in underestimating the US-Europe cost difference – but the method is sound. Unfortunately, this paper is obscure, whereas his work on cost overruns is famous.

In the case of high-speed rail, it seems to me, from pure eyeballing, that there is a difference between countries in how much costs run over, and that this correlates strongly with high construction costs. German train projects, including the one example cited by the Economist, run over a lot. French and Spanish high-speed lines do not, and also cost much less.

Of course, this by itself doesn’t mean this correlation should keep holding: up until Barcelona Line 9, originally budgeted at €1.9 billion but now up to €6.5 billion, Spanish subway lines were built within budget. France has not yet had a factor-of-3 overrun on a major project, but it might in the future, and I’m not going to bet my life that it won’t. But what this does suggest is that looking at German overruns as if they’re typical rather than extremal cases is deeply misleading.

There’s an argument to be made that California’s inability to rein in the contractors will in fact lead to German cost overruns. California HSR’s projected costs look downright reasonable, whereas rapid transit projects in the state are unusually expensive. The proposed BART to San Jose tunnel is $4 billion for 8 km – very high by general subway standards, and unheard of for a subway in low-density suburbia. Going by Flyvbjerg’s own attempts to find ex ante cost estimates that are reliable, this could be used as evidence for future cost escalations; general overruns couldn’t, not without being more specific.

Carbon Costs May Be Far Higher Than Previously Thought

A pair of economists at Economics for Equity and the Environment (E3) have just released a study positing that the social cost of carbon is far higher than previous estimates, by up to an order of magnitude. The official estimate used by the US government is $21 per metric ton of CO2 as of 2010, and various estimates go up to about $100-200, e.g. the Swedish carbon tax is 101 Euros per ton, and James Hansen recommended $115 per ton. In contrast, the E3 study’s range, using newer estimates of damages, goes up to $900 per ton of CO2 as of 2010, escalating to $1,500 in 2050, when the discount rate is low and the price is based on a worst case scenario (95th percentile) rather than the average.

One should bear in mind that the discount rate used to get the high numbers is 1.5%, in line with what was used by the economists at Bjorn Lomborg’s Copenhagen Consensus to arrive at the conclusion that climate change mitigation was a waste of time. It’s not a radical estimate, although some commentators have wrongly confused it with zero discount rate; it’s in line with the long-term risk-free bond yields. Even using average rather than worst-case damages (but still averages coming from the newer, higher estimates) would give a carbon tax of $500 as of 2010, escalating to $800 by 2050.

The carbon content of gasoline is such that a $900/ton tax would be almost to $8 per gallon of gasoline, or $2 per liter. For diesel, make it $9 per gallon. Good transit advocates are engaging in fantasy if they think this, even together with other costs such as air pollution, would eliminate driving; however, it would severely curtail it, inducing people to take shorter trips, switch some trips to public transportation, and drive much more fuel-efficient cars. All three are necessary: not even in Switzerland has the transit revival gotten to the point of abolishing the car. However, the current US car mode share – 86% for work trips – is unsustainable and has to go down under any scenario with a high carbon tax.

More intriguing would be the effect on electricity consumption and generation. Current coal-fired plants in the US would see an average tax of about $0.89 per kWh; natural gas plants would be taxed $0.49 per kWh. Cities already have an advantage there – New York City claims 4,700 kWh of annual electricity consumption per capita, while the current US average is about 13,000. Obviously, in both cases, fossil-fired electricity consumption would crash, while solar and wind power would become a bargain, but it would be easier to do this in large cities. But again, urban revival has its limits; suburban houses would still exist, just with much more passive solar design and extensive solar panels.

Quick Note: Are HSR Transfers Acceptable?

When SNCF built the first TGV line, it did not have funding to complete the full line from Paris to Lyon. Instead, it built two thirds of the line’s length, with the remaining third done on legacy track at reduced speed. The travel time was 4 hours; when the full line was completed a few years later, it was reduced to 2. The one-seat ride remains the TGV’s current operating model, to the point that one unelectrified branch got direct service with a diesel locomotive attached to the trains at the end, and was only electrified recently.

In Japan, transfers are more common, because of the different track gauges. At the outer ends of the Shinkansen, it is common for people to transfer to a legacy express train at the northern end of the line, though on two branches JR East built two Mini-Shinkansen lines, regauging or dual-gauging legacy track to make TGV-style through-running possible. In Germany, the entire system is built on transfers, typically timed between two high-speed trains.

I mention this because the California HSR activists are talking about the possibility of transfers as an initial phase. Some politicians occasionally hint about forced transfers at San Jose, even though it is relatively easy (in fact, planned) to electrify Caltrain and run trains through to San Francisco, but more intriguing is Clem Tillier and Richard Mlynarik’s proposal about running to Livermore first:

This is predicated on prioritizing the San Francisco to Los Angeles connection. It has nothing to do with Sacramento or the East Bay… those are just the cherry on top. Focus on the cake, not the cherry.

LA – Livermore HSR 2:06

Transfer in Livermore 0:10

Livermore – SF Embarcadero BART 0:57

TOTAL SF-LA via Altamont/Livermore BART 3:13LA – Gilroy HSR 1:57

Transfer in Gilroy 0:10

Gilroy – SF 4th & King by Caltrain 2:00

TOTAL SF-LA via Pacheco/Gilroy Caltrain 4:07It’s simply not a contest. Even for San Jose, LA – SJ downtown times would be approximately equivalent via Livermore BART once BART to SJ is built. So let me reiterate: No other alternative, least of all Pacheco, provides such a “Phase Zero” access to SF.

The one possible problem: Livermore’s quality of service will be low after BART goes there. From their 1982 opening until 1985, the Tohoku and Joetsu Shinkansen only served Omiya, located 30 km north of central Tokyo; however, Omiya was already connected to Tokyo by multiple high-capacity rapid transit lines, and an additional line was built at the same time as mitigation for the line’s construction impacts.

Quick Note: Midwest HSR Study

I’m usually skeptical of industry-funded studies about the value of megaprojects, but despite the involvement of Siemens I recommend reading the 2011 Economic Study for Midwest high-speed rail.

Building up on previous ideas for the 110 mph Midwest high-speed rail and on SNCF’s proposal, the study goes through all the nitty-gritty details that are often missing from publications geared toward investors and urban boosters. The technical report addresses questions about alignment, transfer convenience, integration with commuter rail, and FRA regulations. It discusses such issues as how to build a tunnel for Metra providing useful regional rail service, why the FRA is likely to let lightweight high-speed trains operate in the US, or whether to route trains through Eau Claire along I-94 or through La Crosse and Rochester on a greenfield alignment.

The proposed cost of the project is $83.6 billion, in 2010 dollars (compare $69 billion in SNCF’s proposal, or $117 billion in year of construction in Amtrak’s one third as long Northeast Corridor proposal). It works out to $35 million per kilometer, which isn’t outrageous but still a little higher than normal for flat terrain; the total contingency in the proposal’s budget is 35% of the base, which is higher than the norm, which is 25%. Construction costs on the French LGV Est‘s second phase are $24 million per km, and those on Belgium’s HSL 3 were $29 million per km.