Category: Incompetence

The MTA Sticks to Its Oversize Stations

In our construction costs report, we highlighted the vast size of the station digs for Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 as one of the primary reasons for the project’s extreme costs. The project’s three new stations cost about three times as much as they should have, even keeping all other issues equal: 96th Street’s dig is about three times as long as necessary based on the trains’ length, and 72nd and 86th Street’s are about twice as long but the stations were mined rather than built cut-and-cover, raising their costs to match that of 96th each. In most comparable cases we’ve found, including Paris, Istanbul, Rome, Stockholm, and (to some extent) Berlin, station digs are barely longer than the minimum necessary for the train platform.

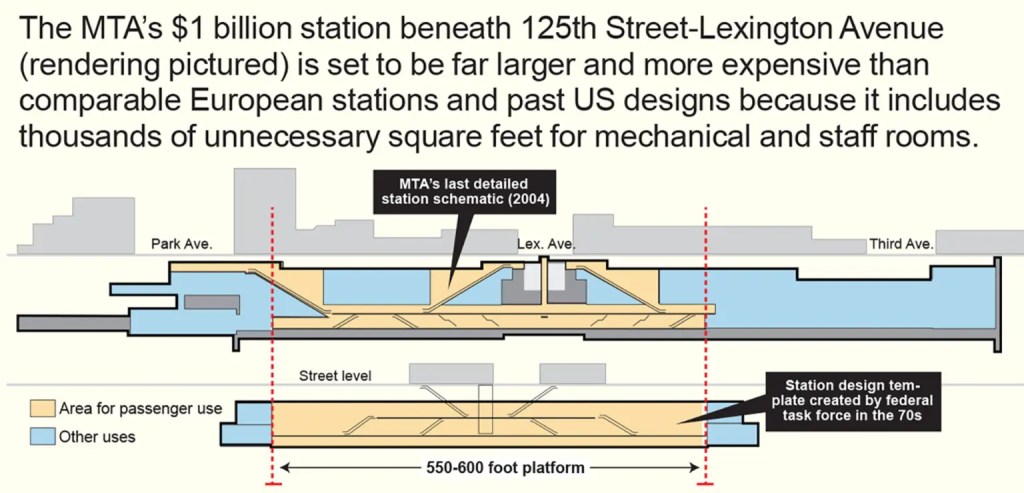

MTA Construction and Development has chosen to keep building oversize stations for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, a project that despite being for the most part easier than the already-open Phase 1, is projected to cost slightly more per kilometer. Nolan Hicks at the New York Post just published a profile diagram:

The enormous size of 125th Street Station is not going to be a grand civic space. As the diagram indicates, the length of the dig past the platforms will not be accessible to passengers. Instead, it will be used for staff and mechanical rooms. Each department wants its own dedicated space, and at no point has MTA leadership told them no.

Worse, this is the station that has to be mined, since it goes under the Lexington Avenue Line. A high-cost construction technique here is unavoidable, which means that the value of avoiding extra costs is higher than at a shallow cut-and-cover dig like those of 106th and 116th Streets. Hence, the $1 billion hard cost of a single station. This is an understandable cost for a commuter rail station mined under a city center, with four tracks and long trains; on a subway, even one with trains the length of those of the New York City Subway, it is not excusable.

When we researched the case report on Phase 1, one of the things we were told is that the reason for the large size of the stations is that within the MTA, New York City Transit is the prestige agency and gets to call the shots; Capital Construction, now Construction and Development, is smaller and lacks the power to tell NYCT no, and from NYCT’s perspective, giving each department its own break rooms is free money from outside. One of the potential solutions we considered was changing the organizational chart of the agency so that C&D would be grouped with general public works and infrastructure agencies and not with NYCT.

But now the head of the MTA is Janno Lieber, who came from C&D. He knows about our report. So does C&D head Jamie Torres-Springer. When one of Torres-Springer’s staffers said a year ago that of course Second Avenue Subway needs more circulation space than Citybanan in Stockholm, since it has higher ridership (in fact, in 2019 the ridership at each of the two Citybana stations, e.g. pp. 39 and 41, was higher than at each of the three Second Avenue Subway stations), the Stockholm reference wasn’t random. They no longer make that false claim. But they stick to the conclusion that is based on this and similar false claims – namely, that it’s normal to build underground urban rail stations with digs that are twice as long as the platform.

When I call for removing Lieber and Torres-Springer from their positions, publicly, and without a soft landing, this is what I mean. They waste money, and so far, they’ve been rewarded: Phase 2 has received a Full Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) from the United States Department of Transportation, giving federal imprimatur to the transparently overly expensive design. When they retire, their successors will get to see that incompetence and multi-billion dollar waste is rewarded, and will aim to imitate that. If, in contrast, the governor does the right thing and replaces Lieber and Torres-Springer with people who are not incurious hacks – people who don’t come from the usual milieu of political appointments in the United States but have a track record of success (which, in construction, means not hiring someone from an English-speaking country) – then the message will be the exact opposite: do a good job or else.

Quick Note: Anti-Green Identity Politics

In Northern Europe right now, there’s a growing backlash to perceived injury to people’s prosperity inflicted by the green movement. In Germany this is seen in campaigning this year by the opposition and even by FDP not against the senior party in government but against the Greens. In the UK, the (partial) cancellation of High Speed 2 involved not just cost concerns but also rhetoric complaining about a war on cars and shifting of high-speed rail money to building new motorway interchanges.

I bring this up for a few reasons. First, to point out a trend. And second, because the Berlin instantiation of the trend is a nice example of what I talked about a month ago about conspiracism.

The trend is that the Green Party in Germany is viewed as Public Enemy #1 by much of the center-right and the entire extreme right, the latter using the slogan “Hang the Greens” at some hate marches from the summer. This is obvious in state-level political campaigning: where in North-Rhine-Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein the unpopularity of the Scholz cabinet over its weak response to the Ukraine war led to CDU-Green coalitions last year (the Greens at the time enjoying high popularity over their pro-Ukraine stance), elections this year have produced CDU-SPD coalitions in Berlin and Hesse, in both cases CDU choosing SPD as a governing partner after having explicitly campaigned against the Greens.

This is not really out of any serious critique of the Green Party or its policy. American neoliberals routinely try to steelman this as having something to do with the party’s opposition to nuclear power, but this doesn’t feature into any of the negative media coverage and barely into any CDU rhetoric. It went into full swing with the heat pump law, debated in early summer.

In Berlin the situation has been especially perverse lately. One of the points made by CDU in the election campaign was that the red-red-green coalition failed to expand city infrastructure as promised. It ran on more room for cars rather than pedestrianization, but also U-Bahn construction; when the coalition agreement was announced, Green political operatives and environmental organizations on Twitter were the most aghast at the prospects of a massive U-Bahn expansion proposed by BVG and redevelopment of Tempelhofer Feld.

And then this month the Berlin government, having not made progress on U-Bahn expansion, announced that it would trial a maglev line. There hasn’t been very good coverage of this in formal English-language media, but here and here are writeups. The proposal is, of course, total vaporware, as is the projected cost of 80 million € for a test line of five to seven kilometers.

This has to be understood, I think, in the context of the concept of openness to new technology (“Technologieoffenheit”), which is usually an FDP slogan but seems to describe what’s going on here as well. In the name of openness to new tech, FDP loves raising doubts about proven technology and assert that perhaps something new will solve all problems better. Hydrogen train experiments are part of it (naturally, they failed). Normally this constant FUD is something I associate with people who are out of power or who are perpetually junior partners to power, like FDP, or until recently the Greens. People in power prefer to do things, and CDU thinks it’s the natural party of government.

And yet, there isn’t really any advance in government in Berlin. The U8 extension to Märkisches Viertel is in the coalition agreement but isn’t moving; every few months there’s a story in the media in which politicians say it’s time to do it, but so far there are no advances in the design, to the point that even the end point of the line is uncertain. And now the government, with all of its anti-green fervor – fervor that given Berlin politics includes support for subway construction – is not so much formally canceling it as just neglecting it, looking at shiny new technologies that are not at all appropriate for urban rail just because they’re not regular subways or regular commuter trains, which don’t have that identity politics load here.

The Northeast Corridor Rail Grants

The US government has just announced a large slate of grants to rail from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Amtrak has a breakdown of projects both for itself and partners, totaling $16.4 billion. There are a few good things there, like Delco Lead, or more significantly more money for the Hudson Tunnel Project (already funded separately, but this covers money the states would otherwise be expected to fund). There are also conspicuously missing items that should stay missing – But by overall budget, most of the grant is pretty bad, covering projects that are in principle good but far too expensive per minute saved.

This has implications to the future of the Northeast Corridor, because the total amount of money for it is $30 billion; I believe this includes Amtrak plus commuter rail agencies. Half of the money is gone already, and some key elements remain unfunded, some of which are still on agency wishlists like Hunter Flyover but others of which are still not, like Shell Interlocking. It’s still possible to cobble together the remaining $13.6 billion to produce something good, but there have to be some compromises – and, more importantly, the process that produced the grant so far doesn’t fill me with confidence about the rest of the money.

The Baltimore tunnel

The biggest single item in the grant is the replacement tunnel for the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel. The B&P was built compromised from the start, with atypically tight curves and steep grades for the era. An FRA report on its replacement from 2011 goes over the history of the project, originally dubbed the Great Circle Passenger Tunnel when first proposed in the 1970s; the 2011 report estimates the cost at $773 million in 2010 prices (PDF-p. 229), and the benefits at a two-minute time saving (PDF-p. 123) plus easier long-term maintenance, as the B&P has water leakage in addition to its geometric problems. At the time, the consensus of Northeastern railfans treated it as a beneficial and even necessary component of Northeast Corridor modernization, and the agencies kept working on it.

Since then, the project’s scope crept from two passenger tracks to four tracks with enough space for double-stacked freight and mechanical ventilation for diesel locomotives. The cost jumped to $4 billion, then $6 billion. The extra scope was removed to save money, said to be $1 billion, but the headline cost remained $6 billion (possibly due to inflation, as American government budgeting is done in current dollars, never constant dollars, creating a lot of fictional cost overruns). The FRA grant is for $4.7 billion out of $6 billion. Meanwhile, the environmental impact statements upped the trip time benefit of the tunnel for Amtrak from two to 2.5 minutes; this is understandable in light of either higher-speed (and higher-cost) redesign or an assumption of better rolling stock than in the 2011 report, higher-acceleration trains losing more time to speed restrictions near stations than lower-acceleration ones.

That this tunnel would be funded was telegraphed well in advance. The tunnel was named after abolitionist hero Frederick Douglass; I’m not aware of any intercity or commuter rail tunnel elsewhere in the developed world that gets such a name, and the choice to name it so about a year ago was a commitment. It’s not a bad project: the maintenance cost savings are real, as is the 2.5 minute improvement in trip time. But 2.5 minutes are not worth $6 billion, or even $6 billion net of maintenance. In 2023 dollars, the estimate from 2011 is $1.1 billion, which I think is fine on the margin – there are lower-hanging fruit out there, but the tunnel doesn’t compete with the lowest-hanging fruit but with the $29 billion-hanging fruit and it should be very competitive there. But when costs explode this much, there are other things that could be done better.

Bridge replacements

The Northeast Corridor is full of movable bridges, which are wishlisted for replacement with high fixed spans. The benefits of those replacements are there, mainly in maintenance costs (but see below on the Connecticut River), but that does not justify the multi-billion dollar budgets of many of them. The Susquehanna River Rail Bridge, the biggest grant in this section, is $2.08 billion in federal funding; the environmental impact study said that in 2015 dollars it was $930 million. The benefits in the EIS include lower maintenance costs, but those are not quantified, even in places where other elements (like the area’s demographics) are.

Like all state of good repair projects, this is spending for its own sake. There are no clear promises the way there are with the Douglass Tunnel, which promises to have a new tunnel with trip time benefits, small as they are. Nobody can know if these bridge replacement projects achieved any of their goals; there are no clear claims about maintenance costs with or without this, nor is there any concerted plan to improve maintenance productivity in general.

The East River Tunnel project, while not a bridge nor a visible replacement, has the same problem. The benefits are not made clear anywhere. There are some documents we found in the ETA commuter rail report saying that high-density signaling would allow increasing peak capacity on one of the two tunnel pairs from 20 to 24 trains per hour, but that’s a small minority of the overall project and in the description it’s an item within an item.

The one exception in this section is the Connecticut River. This bridge replacement has a much clearer benefit – but also is a down payment on the wrong choice. The issue is that pleasure boat traffic has priority over the railroad on the “who came first” principle; by agreement with the Coast Guard, there is a limited number of daily windows for Amtrak to run its trains, which work out to about an Acela and a Regional every hour in each direction. Replacing this bridge, unlike the others, would have a visible benefit: more trains could run (once new rolling stock comes in, but that’s already in production).

Unfortunately, the trains would be running on the curviest and also most easily bypassable section of the Northeast Corridor. The average speed on the New Haven-Kingston section of the Northeast Corridor is low, if not so low on the less curvy but commuter rail-primary New Haven Line farther west. The curves already have high superelevation and the Acelas tilt through them fully; there’s not much more that can be done to increase speed, save to bypass this entire section. Fortunately, a bypass parallel to I-95 is feasible here – there isn’t as much suburban development as west of New Haven, where there are many commuters to New York. Partial bypasses have been studied before, bypassing both the worst curves on this section and all movable bridges, including that on the Connecticut. To replace this bridge in place is a down payment on, in effect, not building genuine high-speed rail where it is most useful.

Other items

Some other items on the list are not so bad. The second largest item in the grant, $3.79 billion, is increasing the federal contribution to the Hudson Tunnel Project from about 50% to about 70%. I have questions about why it’s necessary – it looks like it’s covering a cost overrun – but it’s not terrible, and by cost it’s by far the biggest reasonable item in this grant.

Beyond that, there are some small projects that are fine, like Delco Lead, part of a program by New Jersey Transit to invest around New Brunswick and Jersey Avenue to create more yard space where it belongs, at the end of where local trains run (and not near city center, where land is expensive).

What’s not (yet) funded

Overall, around 25% of this grant is fine. But there are serious gaps – not only are the bridge replacements and the Douglass Tunnel not the best use of money, but also some important projects providing both reliability and speed are missing. The two most complex flat junctions of the Northeast Corridor near New York, Hunter in New Jersey and Shell in New Rochelle, are missing (and Hunter is on the New Jersey Transit wishlist); Hunter is estimated at $300 million and would make it much more straightforward to timetable Northeast Corridor commuter and intercity trains together, and Shell would likely cost the same and also facilitate the same for Penn Station Access. The Hartford Line is getting investment into double track, but no electrification, which American railroads keep underrating.

The MTA 20 Year Needs Assessment Reminds Us They Can’t Build

The much-anticipated 20 Year Needs Assessment was released 2.5 days ago. It’s embarrassingly bad, and the reason is that the MTA can’t build, and is run by people who even by Northeastern US standards – not just other metro areas but also New Jersey – can’t build and propose reforms that make it even harder to build.

I see people discuss the slate of expansion projects in the assessment – things like Empire Connection restoration, a subway under Utica, extensions of Second Avenue Subway, and various infill stations. On the surface of it, the list of expansion projects is decent; there are quibbles, but in theory it’s not a bad list. But in practice, it’s not intended seriously. The best way to describe this list is if the average poster on a crayon forum got free reins to design something on the fly and then an NGO with a large budget made it into a glossy presentation. The costs are insane, for example $2.5 billion for an elevated extension of the 3 to Spring Creek of about 1.5 km (good idea, horrific cost), and $15.9 billion for a 6.8 km Utica subway (see maps here); this is in 2027 dollars, but the inescapable conclusion here is that the MTA thinks that to build an elevated extension in East New York should cost almost as much as it did to build a subway in Manhattan, where it used the density and complexity of the terrain as an argument for why things cost as much as they did.

To make sure people don’t say “well, $16 billion is a lot but Utica is worth it,” the report also lowballs the benefits in some places. Utica is presented as having three alternatives: subway, BRT, and subway part of the way and BRT the rest of the way; the subway alternative has the lowest projected ridership of the three, estimated at 55,600 riders/weekday, not many more than ride the bus today, and fewer than ride the combination of all three buses in the area today (B46 on Utica, B44 on Nostrand, B41 on Flatbush). For comparison, where the M15 on First and Second Avenues had about 50,000 weekday trips before Second Avenue Subway opened, the two-way ridership at the three new stations plus the increase in ridership at 63rd Street was 160,000 on the eve of corona, and that’s over just a quarter of the route; the projection for the phase that opened is 200,000 (and is likely to be achieved if the system gets back to pre-corona ridership), and that for the entire route from Harlem to Lower Manhattan is 560,000. On a more reasonable estimate, based on bus ridership and gains from faster speeds and saving the subway transfer, Utica should get around twice the ridership of the buses and so should Nostrand (not included in the plan), on the order of 150,000 and 100,000 respectively.

Nothing there is truly designed to optimize how to improve in a place that can’t build. London can’t build either, even if its costs are a fraction of New York’s (which fraction seems to be falling since New York’s costs seem to be rising faster); to compensate, TfL has run some very good operations, squeezing 36 trains per hour out of some of its lines, and making plans to invest in signaling and route design to allow similar throughput levels on other lines. The 20 Year Needs Assessment mentions signaling, but doesn’t at all promise any higher throughput, and instead talks about state of good repair: if it fails to improve throughput much, there’s no paper trail that they ever promised more than mid-20s trains per hour; the L’s Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) signals permit 26 tph in theory but electrical capacity limits the line to 20, and the 7 still runs about 24 peak tph. London reacted to its inability to build by, in effect, operating so well that each line can do the work of 1.5 lines in New York; New York has little interest.

The things in there that the MTA does intend to build are slow in ways that cross the line from an embarrassment to an atrocity. There’s an ongoing investment plan in elevator accessibility on the subway. The assessment trumpets that “90% of ridership” will be at accessible stations in 2045, and 95% of stations (not weighted by ridership) will be accessible by 2055. Berlin has a two years older subway network than New York; here, 146 out of 175 stations have an elevator or ramp, for which the media has attacked the agency for its slow rollout of systemwide accessibility, after promises to retrofit the entire system by about this year were dashed.

The sheer hate of disabled people that drips from every MTA document about its accessibility installation is, frankly, disgusting, and makes a mockery of accessibility laws. Berlin has made stations accessible for about 2 million € apiece, and in Madrid the cost is about 10 million € (Madrid usually builds much more cheaply than Berlin, but first of all its side platforms and fare barriers mean it needs more elevators than Berlin, and second it builds more elevators than the minimum because at its low costs it can afford to do so). In New York, the costs nowadays start at $50 million and go up from there; the average for the current slate of stations is around $70 million.

And the reason for this inability to build is decisions made by current MTA leadership, on an ongoing basis. The norm in low- and medium-cost countries is that designs are made in-house, or by consultants who are directly supervised by in-house civil service engineers who have sufficient team size to make decisions. In New York, as in the rest of the US, the norms is that not only is design done with consultants, but also the consultants are supervised by another layer of consultants. The generalist leadership at the MTA doesn’t know enough to supervise them: the civil service is small and constantly bullied by the political appointees, and the political appointees have no background in planning or engineering and have little respect for experts who do. Thus, they tell the consultants “study everything” and give no guidance; the consultants dutifully study literally everything and can’t use their own expertise for how to prune the search tree, leading to very high design costs.

Procurement, likewise, is done on the principle that the MTA civil service can’t do anything. Thus, the political appointees build more and more layers of intermediaries. MTA head Janno Lieber takes credit for the design-build law from 2019, in which it’s legalized (and in some cases mandated) to have some merger of design and construction, but now there’s impetus to merge even more, in what is called progressive design-build (in short: New York’s definition of design-build is similar to what is used in Turkey and what we call des-bid-ign-build in our report – two contracts, but the design contract is incomplete and the build contract includes completing the design; progressive design-build means doing a single contract). Low- and medium-cost countries don’t do any of this, with the exception of Nordic examples, which have seen a sharp rise in costs from low to medium in conjunction with doing this.

And MTA leadership likes this. So do the contractors, since the civil service in New York is so enfeebled – scourged by the likes of Lieber, denied any flexibility to make decisions – that it can’t properly supervise design-bid-build projects (and still the transition to design-build is raising costs a bit). Layers of consultants, insulated from public scrutiny over why exactly the MTA can’t make its stations accessible or extend the subway, are exactly what incompetent political appointees (but I repeat myself) want.

Hence, the assessment. Other than the repulsively slow timeline on accessibility, this is not intended to be built. It’s not even intended as a “what if.” It’s barely even speculation. It’s kayfabe. It’s mimicry of a real plan. It’s a list of things that everyone agrees should be there plus a few things some planners wanted, mostly solidly, complete with numbers that say “oh well, we can’t, let’s move on.” And this will not end while current leadership stays there. They can’t build, and they don’t want to be able to build; this is the result.

High Speed 2 is (Partly) Canceled Due to High Costs

It’s not yet officially confirmed, but Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will formally announce that High Speed 2 will be paused north of Birmingham. All media reporting on this issue – BBC, Reuters, Sky, Telegraph – centers the issue of costs; the Telegraph just ran an op-ed supporting the curtailment on grounds of fiscal prudence.

I can’t tell you how the costs compare with the benefits, but the costs, as compared with other costs, really are extremely high. The Telegraph op-ed has a graph with how real costs have risen over time (other media reporting conflates cost overruns with inflation), which pegs current costs, with the leg to Manchester still in there, as ranging from about £85 billion to £112 billion in 2022 prices, for a full network of (I believe) 530 km. In PPP terms, this is $230-310 million/km, which is typical of subways in low-to-medium-cost countries (and somewhat less than half as much as a London Undeground extension). The total cost in 2022 terms of all high-speed lines opened to date in France and Germany combined is about the same as the low end of the range for High Speed 2.

I bring this up not to complain about high costs – I’ve done this in Britain many times – but to point out that costs matter. The ability of a country or city to build useful infrastructure really does depend on cost, and allowing costs to explode in order to buy off specific constituencies, out of poor engineering, or out of indifference to good project delivery practices means less stuff can be built.

Britain, unfortunately, has done all three. High Speed 2 is full of scope creep designed to buy off groups – namely, there is a lot of gratuious tunneling in the London-Birmingham first phase, the one that isn’t being scrapped. The terrain is flat by French or German standards, but the people living in the rural areas northwest of London are wealthy and NIMBY and complained and so they got their tunnels, which at this point are so advanced in construction that it’s not possible to descope them.

Then there are questionable engineering decisions, like the truly massive urban stations. The line was planned with a massive addition to Euston Station, which has since been descoped (I blogged it when it was still uncertain, but it was later confirmed); the current plan seems to be to dump passengers at Old Oak Common, at an Elizabeth line station somewhat outside Central London. It’s possible to connect to Euston with some very good operational discipline, but that requires imitating some specific Shinkansen operations that aren’t used anywhere in Europe, because the surplus of tracks at the Parisian terminals is so great it’s not needed there, and nowhere else in Europe is there such high single-city ridership.

And then there is poor project delivery, and here, the Tories themselves are partly to blame. They love the privatization of the state to massive consultancies. As I keep saying about the history of London Underground construction costs, the history doesn’t prove in any way that it’s Margaret Thatcher’s fault, but it sure is consistent with that hypothesis – costs were rising even before she came to power, but the real explosion happened between the 1970s (with the opening of the Jubilee line at 2022 PPP $172 million/km) and the 1990s (with the opening of the Jubilee line extension at $570 million/km).

The Importance of Tangibles

I’m writing this post on a train to Copenhagen. So many things about this trip are just wrong: the air conditioning in the car where we reserved seats is broken so we had to find somewhere else to sit, the train is delayed, there was a 10-minute stop at the border for Danish cops to check the IDs of some riders (with racial profiling). Even the booking was a bit jank: the Deutsche Bahn website easily sells one-ways and roundtrips, but this is a multi-city trip and we had to book it as two nested roundtrips. Those are the sort of intangibles that people who ride intercity trains a lot more than I do constantly complain about, usually when they travel to France and find that the TGV system does really poorly on all the metrics that the economic analysis papers looking at speed do not look at. And yet, those intangibles at the end of the day really are either just a matter of speed (like the 10-minute delay at the border) or not that important. But to get why it’s easy for rail users to overlook them, it’s important to understand the distinction between voice and exit.

Voice and exit strategies

The disgruntled customer, employee, or resident can respond in one of two ways. The traditional way as understood within economics is exit: switch to a competing product (or stop buying), quit, or emigrate. Voice means communicating one’s unhappiness to authority, which may include exercising political power if one has any; organizing a union is a voice strategy.

These two strategies are not at all mutually exclusive. Exit threat can enhance voice: Wikipedia in the link above gives the example of East Germany, where the constant emigration threat of the common citizenry amplified the protests of the late 1980s, but two more examples include union organizing and the history of Sweden. With unions, the use of voice (through organizing and engaging in industrial action) is stronger when there is an exit threat (through better employment opportunities elsewhere); it’s well-known that unions have an easier time negotiating better wages, benefits, and work conditions during times of low unemployment than during times of high unemployment. And with Sweden, the turn-of-the-century union movement used the threat of emigration to the United States to extract concessions from employers, to the point of holding English classes for workers.

Conversely, voice can amplify exit. To keep going with the example of unions, unions sometimes engage in coordinated boycotts to show strength – and they request that allies engage in boycotts when, and only when, the union publicly calls for them; wildcat boycotts, in which consumers stop using a product when there is a labor dispute without any union coordination, do not enhance the union’s negotiating position, and may even make management panic thinking the company is having an unrelated slump and propose layoffs.

The upshot is that constantly complaining about poor service is a voice strategy. It’s precise, and clearly communicates what the problem is. However, the sort of people who engage in such public complaints are usually still going to ride the trains. I’m not going to drive if the train is bad; I’d have to learn how to drive, for one. In my case, poor rail service means I’m going to take fewer trips – I probably would have done multiple weekend trips to each of Munich and Cologne this summer if the trains took 2.5 hours each way and not 4-4.5. In the case of more frequent travelers than me, especially railfans, it may not even mean that.

The trip not taken

On this very trip, we were trying to meet up in Hamburg with a friend who lives in Bonn, and who, like us, wants to see Hamburg. And then the friend tried booking the trip and realized that it was 4.5 hours Hbf-to-Hbf, and more than five hours door-to-door; we had both guessed it would be three hours; a high-speed rail network would do the trip in 2:15. The friend is not a railfan or much of a user of social media; to Deutsche Bahn, the revenue loss is noticeable, but not the voice.

And that’s where actually measuring passenger usage becomes so important. People who complain are not a representative cross-section of society: they use the system intensively, to the point that they’re unlikely to be the marginal users the railroad needs to attract away from driving or to induce to make the trip; they are familiar with navigating the red tape, to the point of being used to jank that turns away less experienced users; they tend to be more politically powerful (whereas my friend is an immigrant with about A2 German) and therefore already have a disproportionate impact on what the railroad does. Complaints can be a useful pilot, but they’re never a substitute for counting trips and revenue.

The issue is that the main threat to Deutsche Bahn, as to any other public railroad, is loss of passengers and the consequent loss of revenue. If the loss of revenue comes from a deliberate decision to subsidize service, then that’s a testament to its political power, as is the case for various regional and local public transport subsidy scheme like the Deutschlandticket and many more like it at the regional level in other countries. But if it comes from loss of passenger revenue, or even stagnation while other modes such as flying surge, then it means the opposite.

This is, if anything, more true of a public-sector rail operator than a private-sector one. A private-sector firm can shrink but maintain a healthy margin and survive as a small player, like so many Class II and III freight rail operators in the United States. But a national railway is, in a capitalist democracy, under constant threat of privatization. The threat is always larger when ridership is poor and when the mode is in decline; thus, British Rail was privatized near its nadir, and Japan National Railways was privatized while, Shinkansen or no Shinkansen, it was losing large amounts of money, in a country where the expectation was that rail should be profitable. Germany threatened to do the same to Deutsche Bahn in the 1990s and 2000s, leading to deferred maintenance, but the process was so slow that by the time it could happen, during the 12 years of CSU control of the Ministry of Transport, ridership was healthy enough there were no longer any demands for such privatization. The stagnant SNCF of the 2010s has had to accept outside reforms (“Société Anonyme”), stopping short of privatization and yet making it easier to do so in the future should a more right-wing government than that of Macron choose to proceed.

The path forward

Rail activists should recognize that the most important determinant of ridership is not the intangibles that irk people who plan complex multi-legged regional rail trips, but the basics: speed, reliability, fares, some degree of frequency (but the odd three-hour wait on a peripheral intercity connection, while bad, is not the end of the world).

On the train I’m on, the most important investment is already under construction: the Fehmarn Belt tunnel is already under construction, and is supposed to open in six years. The construction cost, 10 billion € for 18 km, is rather high, setting records in both countries. The project is said to stand to shorten the Hamburg-Copenhagen trip time, currently 4:40 on paper with an average delay of 21 minutes and a 0% on-time performance in the last month, to 2.5 hours. If Germany bothers to build high-speed approaches, and Denmark bothers to complete its own high-speed approaches and rate them at 300 km/h and not 200-250, the trip could be done in 1.5 hours.

Domestically, and across borders that involve regular overland high-speed rail rather than undersea tunnels, construction of fast trains proceeds at a sluggish pace. German rail advocates, unfortunately, want to see less high-speed rail rather than more, due to a combination of NIMBYism, the good-enough phenomenon, and constant sneering at France and Southern Europe.

But it’s important to keep focusing on a network of fast rail links between major cities. That’s the source of intercity rail ridership at scale. People love complaining about the lack of good rail for niche town pairs involving regional connections at both ends, but those town pairs are never going to get rail service that can beat the car for the great majority of potential riders who own a car and aren’t environmental martyrs. In contrast, the 2.5- and three-hour connection at long intercity distances reliably gets the sort of riders who are more marginal to the system and respond to seeing a five-hour trip with exit rather than voice.

Quick Note on Ecotourism and Climate

On Mastodon, I follow the EU Commission’s feed, which reliably outputs schlock that expresses enthusiasm about things that don’t excite anyone who doesn’t work for the EU. A few days ago, it posted something about green tourism that goes beyond the usual saying nothing, and instead actively promotes the wrong things.

The issue at hand is that the greenest way to do tourism is to avoid flying and driving. The origin of Greta Thunberg’s activism is that, in 2018, she was disturbed by the standard green message at school: recycle bottles, but fly to other continents for vacations and tell exciting stories. The concept of flight shame originates with her; she hasn’t flown at all since 2015 and famously traveled to New York by sailboat, but most of her followers are more pragmatic and shift to trains where possible (domestically) and not where it is too ridiculous (internationally, even within Europe).

So environmentally sustainable tourism means tourism that does not involve flying or driving. It means taking the train to Munich or Hamburg or Cologne – or Rome, for the dedicated environmental masochist – doing city center tourism, and at no point using a form of transportation that isn’t a train or maybe a bus.

But the European Commission isn’t recommending that. It’s telling people to choose ecotourism, with a top-down photo of a forest. From Europe, this invariably means flying long distances, and then getting around by taxi in a biome that Europe does not have, usually a tropical climate. The point of ecotourism is not to reduce emissions or any other environmental footprint; it’s to go see a place of natural beauty before it’s destroyed by climate change coming in part from the emissions generated by the trip to it.

This worse-than-nothing campaign comes at a time when there’s growth in demand for actually green tourism in sections of Europe. The more hardcore greens talk about night trains so that they can do those all-rail trips to more distant parts of Europe. People who believe that the Union might be able to do something instead hold out for high-speed trains.

Even with the Commission’s regular appetite for words over actions, there are things that can be done about greening tourism. For example, it could help advertise intra-European attractions that could be done by rail. Berlin is full of these “You are EU” posters that say nothing; they could be telling people how to get to Prague, to any Polish city within reasonable train range, to Jutland if there’s anything interesting there.

At longer range, it could be helping promote circuits of travel entirely by rail. There’s already an UNESCO initiative promoting circuits, designed entirely around ecotourism principles (i.e. drive to where you can see pretty landscapes). This could be adapted to rail circuits, perhaps with some promotional deals. People who go on vacation for 5 weeks at once could be induced to ride trains visiting a different city every few days, breaking what would be a flight or an unreasonably long rail trip into short segments; there are enough cycles in the European intercity rail network that people wouldn’t need to visit the same city twice. For example, one route could go Berlin-Prague-Vienna-Salzburg-Venice-Rome-Milan-Basel-Cologne-Berlin. This is a rather urban route; circuits that include non-urban rail destinations like Saxon Switzerland or the Black Forest are also viable, but the more destinations are added, the smaller the circuit can be.

Connecticut Pays Double for Substandard Trains

Alstom and Connecticut recently announced an order for 60 unpowered coaches, to cost $315 million. The cost – $5.25 million per 25 meter long car – is about twice as high as the norm for powered cars (electric multiple units, or EMUs), and close to the cost of an electric locomotive in Europe. It goes without saying that top officials at the Connecticut Departmemarknt of Transportation (CTDOT) need to lose their jobs over this.

The frustrating thing is that unlike the construction costs of physical infrastructure, the acquisition costs of rolling stock were not traditionally at a premium in the United States. Metro-North’s EMUs, the M8s, were acquired in 2006 for $760.3 million covering 300 cars (see PDF-p. 16); a subsequent order in 2013 for the LIRR and Metro-North was $1.83 billion for 676 cars. But then over the 2010s, the MTA’s commuter railways lost their ability to procure rolling stock at such cost. The $5.25 million/car cost is not even an artifact of recent inflation – the cost explosion was visible already on the eve of corona.

It appears that some of the trains are on their way to the fully wired Penn Station Access project, expanding Metro-North service to Penn Station via the line currently used only by Amtrak (today, Metro-North only serves Grand Central). The excuse I’ve heard is that it’s happening too fast for Metro-North or CTDOT to order proper EMUs. In reality, Penn Station Access has been under construction and previously under design for many years, and the regular replacement of the rolling stock on the other lines is also known well in advance.

Nor are these unpowered coaches some kind of fast off-the-shelf order. If they were, they wouldn’t cost like an electric locomotive. The Trains.com article says,

The 85-foot stainless steel cars, designed for at least a 40-year service life, will be based on Alstom’s X’Trapolis European EMU railcar, designed to meet Federal Railroad Administration requirements and tailored to meet Connecticut Department of Transportation needs.

In other words, Alstom took an existing EMU, gutted it to make it an unpowered coach, and then added extra weight on it for buff strength, to satisfy regulations that have already been superseded: the FRA rolling stock regulations were aligned with European norms in 2018, in dialog with the European vendors, and yet not a single one of the American commuter rail operators has seen fit to make use of the new regulations, instead insisting on buying substandard trains that no other market has any use for.

Ideally, this order should be stopped, even if CTDOT needs to pay a penalty – perhaps laying off top management would partly defray that penalty. The options should not be exercised. All future procurement should be done by people with experience buying trains that cost $100,000 per meter of length, not $210,000. If this is not done, then no public money should be given to such operations.

Rolling stock costs, Europe version

Meanwhile, in Europe, inflation hasn’t made trains cost $210,000 per meter of length. In the 2010s, nominal costs were actually decreasing for Swiss FLIRTs. Costs seem to have risen somewhat in the last few years, but overall, the cost inflation looks lower than the general inflation rate – manufacturing is getting more efficient, so the costs are falling, just as the costs of televisions and computers are falling.

Even with recent inflation, Alstom’s Coradia Stream order for RENFE cost 8.95 million € per train. I can’t find the train length – the press release only says six cars of which two are bilevel. An earlier press release says that this is 100 meters long in total, but I don’t believe this number – the bilevel Streams in Luxembourg are 27 meters long per car (and cost 2.53 million €/car; Wikipedia says the 34 trains break down as 22 short, 12 long), and other Streams tend to be longer per car as well. Bear in mind that even at 100 meters, it’s barely more than $100,000/m for a train that’s partly bilevel.

Other Coradia Stream orders have a similar or slightly higher cost. An order for 100 trains for DSB, all single-level, is 14 million €/train, including 15 years of full maintenance; Wikipedia says that these are 109 meter long. An order for 17 trains totaling 72 27-meter cars for the Rhine-Main region cost 218.2 million €. A three four-car, 84-meter train order for Abruzzo costs 19 million €.

To be fair, some orders look more expensive. For new regional operations through the soon to open Stuttgart 21 station, Baden-Württemberg has ordered 130 106-meter Streams, mixed single- and double-deck, for 2.5 billion €; I think this is the right comparison, but the cost may also include an option for 100 trains, which makes it clearer why this costs double what the rest of Europe pays. Baden-Württemberg’s Mireo order costs 300 million € for 28 three-car, 70 meter long EMUs – less than the Streams, more than the norm elsewhere in Europe for single-deck EMUs.

But what we don’t have in Europe is unpowered single-level coaches at $210,000/meter. That is ridiculous. Orders would be canceled and retendered at this cost, and the media would question the agencies and governments that approved such a waste.

It’s only Americans who have no standards at all for their government. Because they have no standards, they are okay with being led by people who cost the public several million dollars per day that they choose to wake up and go to work, like MTA head Janno Lieber or his predecessor Pat Foye, or many others at that level. Because those leaders are extraordinarily incompetent, they have not fixed what their respective agencies were bad at (physical infrastructure construction) but have presided over the destruction of what they used to be good at and no longer are (rolling stock procurement). The result is worse trains than any self-respecting first-world city gets for its commuter rail system, at a cost that is literally the highest in the world.

Pete Buttigieg, Bent Flyvbjerg, and My Pessimism About American Costs

A few days ago, US Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg appeared together with Bent Flyvbjerg to discuss megaprojects and construction costs. Flyvbjerg’s work on cost overruns is, in the English-speaking world, the starting point for any discussion of infrastructure costs, and I’m glad that it is finally noticed at such a high level.

Unfortunately, everything about the discussion, in context, makes me pessimistic. The appearance was about establishing a Center of Excellence at the Volpe Center to study project delivery and transmit best practices to various agencies; but, in context with what I’ve seen at agencies as well as federal regulators, it will not be able to figure out how to learn good practices the way it is currently set up, and what it can learn, it won’t be able to transmit. It’s sad, really, because Buttigieg clearly wants to be able to build; with his current position and presidential ambitions, his path upward relies on being able to build transportation megaprojects, but the current US Department of Transportation (USDOT) and the political system writ large seem uninterested in reforming in the right direction.

What Flyvbjerg said

Flyvbjerg’s studies are predominantly about cost overruns, rather than absolute costs. The insights required to limit overruns are not the same as those required to reduce costs in general, but they intersect substantially, and in recent years Flyvbjerg has written more about absolute costs as well. The topics he discussed with Buttigieg are in this intersection.

In latter-day Flyvbjerg, there’s a great emphasis on standardization and modularity. He speaks favorably of Spain’s standardized construction methods as one reason for its famously low construction costs – costs that remain very low in the 2020s. We found something similar in our own work, seeing an increase of 50% in New York construction costs coming from lack of standardization in track and station systems; in our own organization, we conceive of standardization as a design standard, separate from the issue of project delivery, but fundamentally it’s all about how to deliver infrastructure construction cost-effectively.

To an extent, the American public-sector transportation project managers I know are aware of the issue of modularity, and are trying to apply it at various levels. However, they are hampered both by obstructive senior managers and political appointees and by federal regulations. For example, to build commuter rail stations, modular design requires technology that, due to supply chain issues, is not made in the United States; this requires a waiver from Buy America rules, which should be straightforward since “not made in the US” is a valid legal reason, but the relevant federal regulatory body is swamped with requests and takes too long to process them, and the federal regulators we spoke to were sympathetic but didn’t seem interested in processing requests faster.

But Flyvbjerg goes further than just asking for design modularity. He uses the expression “You’re unique, like everybody else.” He talks about learning from other projects, and Buttigieg seems to get it. This is really useful in the sense that nothing that is done in the United States is globally unique; California High-Speed Rail, among the projects they discussed, was an attempt to import technology that already 15 years ago had a long history in Western Europe and Japan. But that project was still planned without any attempt to learn the successful project delivery mechanisms of those older systems. And the Volpe Center, federal regulators, and federal politicos writ large seem uninterested in foreign learning even now.

What we’ve seen

Eric, Elif, Marco, and I have presented our findings to Americans at various levels – not to Buttigieg himself, but to people who I think may regularly interact with him; I can’t tell the exact level, not being familiar with government insider culture. Some of the people we’ve interacted with seem helpful, interested in adopting some of our findings, and willing to change things; others are not.

But what we’ve persistently seen is an unwillingness to just go ahead and learn from foreigners. The new Center of Excellence is run by Cynthia Maloney, who’s worked for Volpe and DOT since 2014 and worked for NASA before; I know nothing of her, but I know what she isn’t, which is an experienced transportation professional who has delivered cost-effective projects before, a type of person who does not exist in the United States and barely exists in the rest of the English-speaking world.

And there’s the rub. We’ve talked to Americans at these levels – regulators, agency heads, political advisors, appointees – and they are often interested in issues of procurement reform, interagency coordination, modular design, and so on. But when we mention the issue of learning from outside the US, they react negatively:

- They rarely speak foreign languages or respect people who do, and therefore don’t try to read the literature if it’s not written in English, such as the Cour des Comptes report on Grand Paris Express.

- They have no interest in hiring foreigners with successful experience in Europe or Asia – the only foreigner whose name comes up is Andy Byford, for his success in New York.

- They don’t ever follow up with specifics that we bring up about Milan or Stockholm, let alone Istanbul, which Elif points out they don’t even register as a place that could be potentially worth looking at.

- They sometimes even make excuses for why it’s not possible to replicate foreign success, in a way that makes it clear they haven’t engaged with the material; for a non-transportation example, a New York sanitation communications official said, with perfect confidence, that New York cannot learn from Rome, because Rome was leveled during WW2 (in fact, Rome was famously an open city).

Even the choice of which academics to learn from exhibits this bias. Flyvbjerg is very well-known in the English-speaking world as well as in countries that speak perfect nonnative English, including his own native Denmark, the rest of Scandinavia, and the Netherlands. But in Germany, France, and Southern Europe, people generally work in the local language, with much lower levels of globalization, and I think this is also the case in East Asia (except high-cost Hong Kong). And there’s simply no engagement with what people here do from the US; the UK appears somewhat better.

You can’t change the United States from a country that builds subways for $2 billion/km in New York and $1 billion/km elsewhere to a country that does so for $200 million/km if all you ever do is talk to other Americans. But the Volpe Center appears on track to do just that. The American political sphere is an extremely insulated place. One of the staffers we spoke to openly told us that it’s hard to sell foreign learning to the American public; well, it’s even harder to sell infrastructure when it’s said to cost $300 billion to turn the Northeast Corridor into a proper high-speed line, where here it would cost $20 billion. DOT seems to be choosing, unconsciously, not to have public transportation.

How to Ensure You Won’t Have Public Transportation

In talking to both activists and government officials, I’ve encountered some assumptions that are clearly incompatible with any sort of viable public transportation provision. In some cases, when I don’t feel obliged to be polite, I immediately react, “Then you will not have public transit” or “you will not have trains.” These include both operations and construction. None of the political constraints mentioned in those conversations appears hard; it’s more a mental block on behalf of the people making this statement, who are uncomfortable with certain good practices. But there really is no alternative; social scientific results like various ridership elasticities can no more be broken than economic laws. Moreover, in some of these cases, half-measures are worse than nothing, leading reform among certain groups of activists to be worse than if those activists had done literally anything else with their spare time than advocacy.

The practices: operations

There’s a lot of resistance among American transit activists to the sort of bus operations that passengers who are not very poor are willing to rely on.

Frequency

American advocacy regarding frequency comes extremely compromised. The sort of frequencies that permit passengers to transfer between buses without timing the connection are single-digit headways, and the digit should probably not be a 9 or even an 8. Nova Xarxa successfully streamlined Barcelona’s bus network as a frequent grid, with buses coming every 3-8 minutes depending on the route. Vancouver and Toronto’s frequent grids are both in the 5-8 minute range.

However, American transit agencies think it’s unrealistic to provide a grid of routes running so frequently. Therefore, they compromise themselves down to a bus every 15 minutes. At 15 minutes, the wait time is too onerous; remember that these are buses that don’t run on a fixed schedule, so a transferring passenger is spending 15 minutes waiting in the average case and 30 minutes in the worst case. These are all city buses, with an in-vehicle trip time in the 15-30 minutes range. A bus system that requires 30 minutes of worst-case wait might as well not exist. If this replaces buses that run every 20 or 30 minutes on a fixed schedule, then this makes things worse.

Bus reliability

Buses naturally tend to bunch. The only lasting solution is active control, i.e. better dispatching. I’ve heard managers treat the prospects of hiring a few more dispatchers as a preposterous extravagance. This is not because of some political diktat; hiring freezes are stupid, but those managers don’t push back and don’t hire more dispatchers even when there’s no hiring freeze.

There’s a bit more interest in technological solutions, but when I was trying to explain conditional signal priority to some managers, they didn’t really get it. This is not quite the same issue – this is not a compromise due to perceived (almost never actual) political constraints, but rather lack of technical chops and disinterest in acquiring it. But lacking such chops, the marginally labor-intensive solution is the only one, and yet it’s not done.

Bus-rail integration

American managers love to slice the market; this includes transit managers, in a situation where the issue of frequency makes any makret segmentation a net negative to all riders. In the suburbs, this results in a segmentation of buses for the poor and trains for the rich; once the buses have average incomes that are only around half the area average, both managers and activists treat them as a kind of soup kitchen, and resist any attempt at integration.

This is less bad in the main cities – bus-subway integration in the American cities that have subways is good, except for Washington. But in Washington on Metro, and everywhere on commuter rail, there’s resistance to fare integration; New York makes incremental changes to reduce the commuter rail fare premium, but until fares are equalized and transfers made free, this is just a subsidy to the rich segment of the market, rather than a breaking down of the segmentation.

The practices: construction and governance

I bundle governance and construction because, in practice, all the examples I’ve seen of people compromising their own ability to do cost reform involve governance.

Learning from others

At a meeting with some government officials to discuss our costs report, one of the people involved asked us if there are any good examples from the United States, saying that as a matter of politics, it’s hard to get Americans to adapt foreign governance schemes. I don’t know how important this person was; long-time readers know that I don’t know Washington Bureaucratese or its Brussels, Albany, Sacramento, etc. equivalents, and in particular I can’t tell from a title, CV, or social cues whether I’m talking to a decider or a flunky. I certainly did not say “Okay, then you won’t have cost-effective construction, and over time, Americans will learn that the government can’t do anything”; I tried explaining why no, it’s really important to learn from foreigners, especially nonnative Anglophones, and I don’t think it got through.

Building up state capacity

Something about Americans makes them hostile to the idea that the government overtly governs. This is not because they’re inherently ungovernable, but because some of them like to pretend to be. This has led to workarounds, which Bring Back the Bureaucrats by John DiIulio (this is DIIULIO in all caps, not DILULIO) calls the leviathan by proxy model, in which the state is outsourced to consultants. Thus, dismantling the state and instead calling in consultants is supposedly the only way to get Americans to accept government spending. This was said to us, at the same meeting as in the above section, by a different person.

This is, like most political claims that justify inaction, bunk. Consultants are not a popular group in the broad public. “This all goes to consultants” is a standard line justifying misturst of government, regardless of politics, to the point that generic anti-everything populists like to make consultants public enemy #1. In New York, even the unions make this one of their rallying cries in opposition to various kinds of outsourcing; there’s no excuse there to keep hiring consultants to do design and then not knowing how to manage them, where what the MTA should do is replace its leadership with people who know better and staff up to the tune of a four-figure planning and engineering department. It costs money. It costs less money than the New York premium for construction, the difference amounting to around a full order of magnitude.

Saying no to surplus extraction

The United States abounds with examples of infrastructure projects that got outside funding, which could be federal, or even just state if the scale is small enough, that local departments took as opportunities for getting other people’s money.

The solution there is simple: just say no. This requires overruling local regulators, but I routinely see states do it when they care to – Long Island’s entire group of interests, including the LIRR, local officials, and state electeds, opposed Metro-North’s Penn Station Access due to turf battles over train slots into Penn Station that were not even in shortage, until Andrew Cuomo fired LIRR head Helena Williams and all of those supposedly intractable voices were silenced. The ability of California High-Speed Rail to defeat rich NIMBYs in Silicon Valley is also notable; the project is moribund, but not because of NIMBYs.

And somehow, when a municipal fire department or parks department makes demand, the immediate reaction in the same country that did the above is to give in. Federal officials who I’m fairly certain are important deciders told me stories about how “in our system of government” (exact words) there is expectation of municipal autonomy and it breaks some unwritten covenant to interfere when a fire department refuses to certify light rail construction that meets fire code, as in suburban Seattle, because the department wants it to go beyond the code. The state that does not take responsibility and respond appropriately – which in this case ranges from disestablishing the fire department in question to disestablishing the entire suburb – is the state that will not really be able to expand its urban rail network, which is really sad since Seattle’s last extension was good and its high rate of housing growth makes it a good place to invest.

Benchmarking to an external world

Activists and managers may tell themselves that they’re just following some kind of necessary political logic. But at the end of the day, neither the passengers nor the contractors care. If the political logic dictates that the bus system be bad, then passengers will just not use it, and instead get cars and drive and vote against any further increases in transit funding due to memory of its low quality. Likewise, if the political logic dictates that capital construction be run by incompetents with no successful (i.e. non-Anglosphere) experience who can’t say no to requests for other people’s money and who mismanage the consultants, then the region will just not be able to build, even if, like Seattle, it clearly wants to. There’s an external world out there and not just the machinations of political insiders.