Category: Regional Rail

Quick Note: The Importance of Penn Station Access West to Through-Running

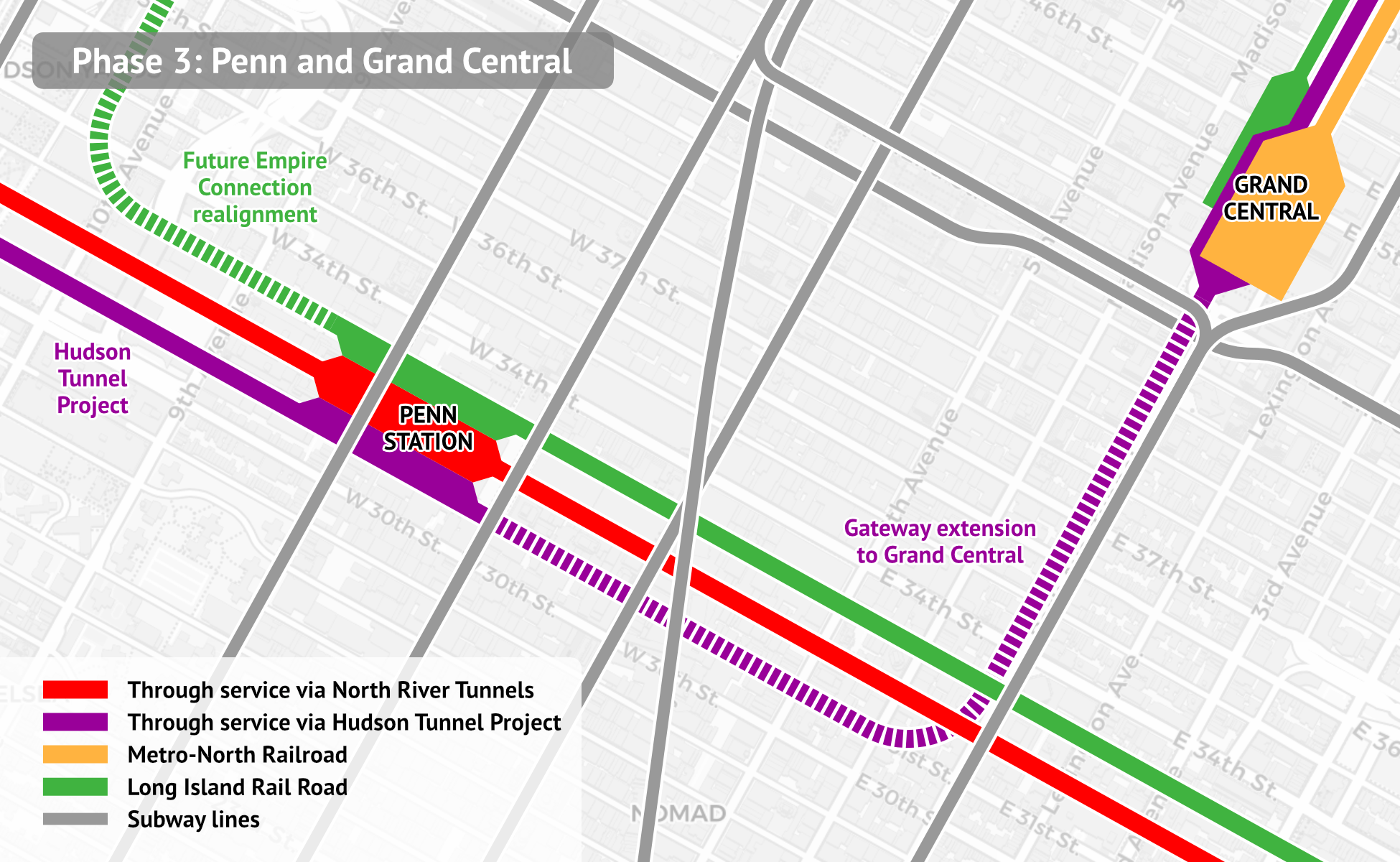

A video by the Joint Transit Association talks at length about through-running in New York – which lines are easier and which are harder, what some of the tradeoffs are, what sequencing works best with ongoing infrastructure plans starting with the Gateway tunnel. It’s a good video and I recommend watching – and not just because it gets a lot of its ideas from ETA reports but also because of its own analysis and own points (about, for example, Mott Haven Junction) – but it has one miss that I’d like to highlight: it neglects Penn Station Access West, the proposal to connect the Hudson Line to Penn Station via the Empire Connection.

The issue is that without the realignment, too many trains would be going into Grand Central – all preexisting Metro-North service minus trains diverted to Penn Station Access. We expect all this through-running infrastructure to add to peak demand substantially. Today it fills about 50 peak trains per hour, which a four-track trunk line would struggle with (Metro-North runs trains three-and-one at the peak). Even with diversion of 6-10 trains to Penn Station Access, the extra demand would saturate the line. Penn Station Access West is important in reducing this capacity crunch.

The realignment is both important and cheap. The Empire Connection exists and the tunnel has room for two tracks; it needs a short realignment to reach the right part of Penn Station – the high-numbered northern tracks as in the image, where today there is a single-track link from the Connection proper to the low-numbered tracks – but that realignment is much cheaper than a full through-tunnel such as between Penn Station and Grand Central or the various lines to Lower Manhattan mooted for longer-term plans.

The total capacity produced should be every train that doesn’t have to go to Grand Central. It’s hard to exactly say what the split should be – there should be a minimum of a train every 10 minutes to each destination, if only to serve the inner stations that are (or would be infill) on the lower Hudson Line or the Empire Connection before the two routes meet at Spuyten Duyvil. Beyond that it’s a matter of measuring demand and seeing what the limit of timed connections are; ideally there should be 12 peak trains per hour on Penn Station Access West and only 6 on the preexisting route, up from 14 total on the Hudson Line today due to service improvements brought by through-running and related upgrades. This is necessary to create the capacity to run more service on the other lines – today the Harlem Line peaks at 16 trains per hour and the New Haven Line at 20, but these upgrades would create a lot more demand and my assumption in sketching through-running tunnels is that the Harlem Line would need 24 and the New Haven Line would need 18 to Grand Central and 6 on Penn Station Access.

Reverse-Branching on Commuter Rail

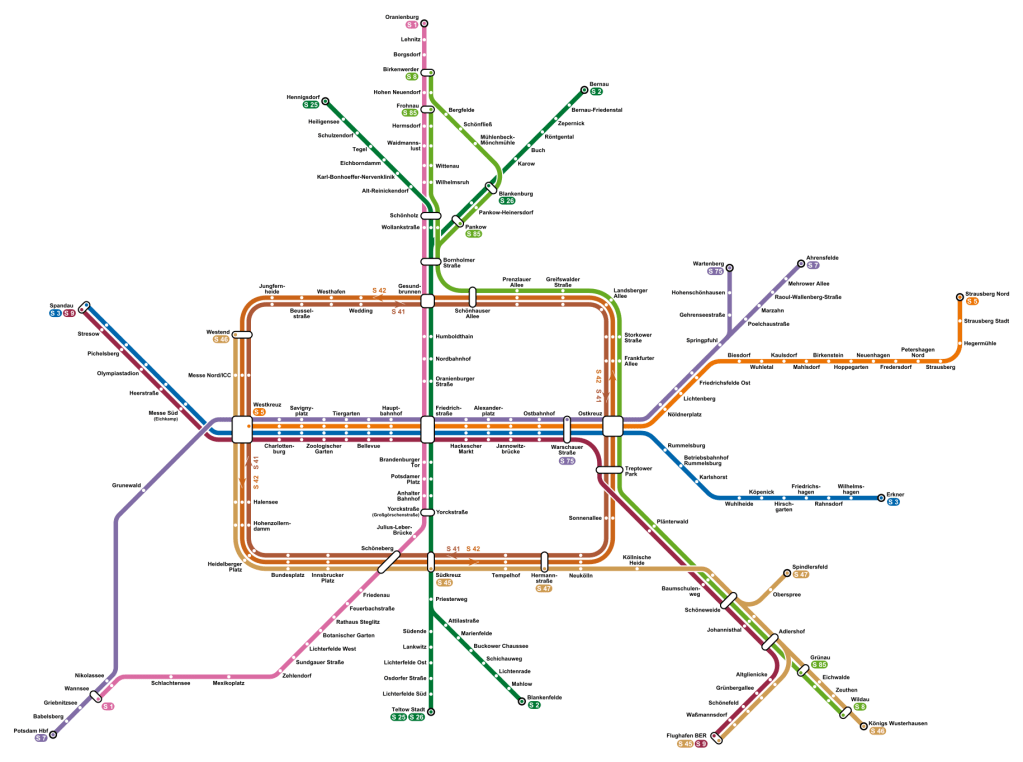

Koji asked me 3.5 days ago about why my proposal for New York commuter rail through-tunnels has so much reverse-branching. I promised I’d post in some more detail, because in truth, reverse-branching is practically inevitable on every commuter rail system with multiple trunk lines, even systems that are rather metro-like like the RER or the S-Bahns here and in Hamburg.

This doesn’t mean that reverse-branches, in this case the split from the Görlitzer Bahn trunk toward the Stadtbahn via S9 and the Ring in two different directions via S45/46/47 and S8/85, are good. It would be better if Berlin invested in turning this trunk into a single trunk into city center, provided it were ready to build a third through-city line (in fact, it is, but this project, S21, essentially twins the North-South Tunnel). However, given the infrastructure or small changes to it, the current situation is unavoidable.

Moreover, the current situation is not the end of the world. The reasons such reverse-branches are not good for the health of the system are as follows:

- They often end up creating more frequency outside city center than toward it.

- If there is too much interlining, then delays on one branch cascade to the others, making the system more fragile.

- If there is too much interlining, then it’s harder to write timetables that satisfy every constraint of a merge point, even before we take delays into account.

All of these issues are more pressing on a metro system than on a commuter rail system. The extent of branching on commuter rail is such that running each line as a separate system is unrealistic; tight timetabling is required no matter what, and in that case, the lines could reverse-branch if there’s no alternative without much loss of capacity. The S-Bahn here is notoriously unreliable, but that’s the case even without cascading delays on reverse-branches – the system just assumes more weekend shutdowns, less reliable systems (28,000 annual elevator outages compared with 1,800 on the similar-size U-Bahn), and worse maintenance practices.

So, on the one hand, the loss from reverse-branching is reduced. On the other hand, it’s harder to avoid reverse-branching on commuter rail. The reason is that, unlike a metro (including a suburban metro), the point of the system is to use old commuter lines and connect them to form a usable urban and suburban service. Because the system relies on old lines more, it’s less likely that they’re at the right places for good connections. In the case of Berlin, it’s that there’s an east-west imbalance that forces some east-center-east lines via S8, which was reinforced by the context of the Cold War and the Wall.

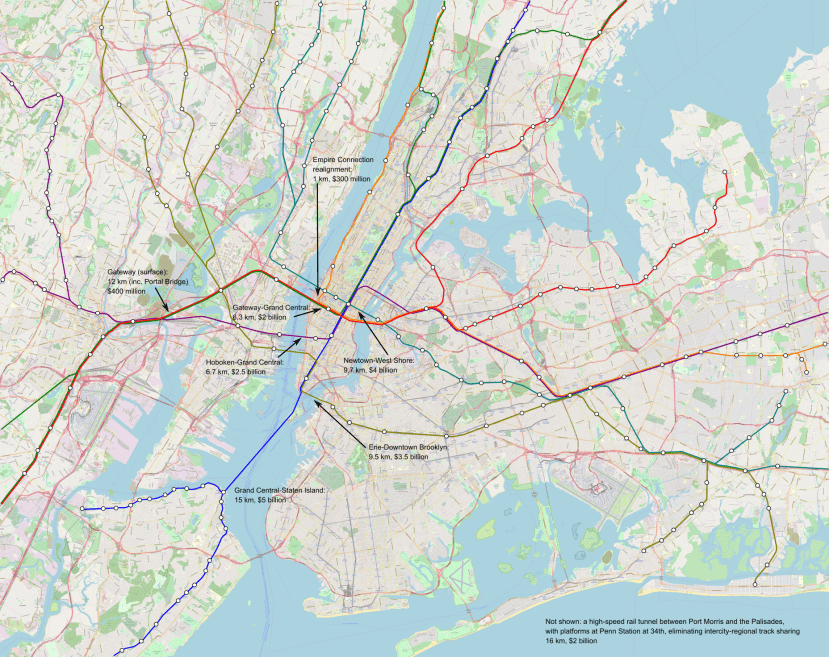

In the case of New York, consider this map:

The issue is that too much traffic wants to use the Northeast Corridor lines in both New Jersey and Connecticut. Therefore, it’s not possible to segregate everything, with lines using the preexisting North River Tunnels and the new Gateway tunnels having to share tracks. It’s not optimal, but it’s what’s possible.

Transit-Oriented Development and Rail Capacity

Hayden Clarkin, inspired by the ongoing YIMBYTown conference in New Haven, asks me about rail capacity on transit-oriented development, in a way that reminds me of Donald Shoup’s critique of trip generation tables from the 2000s, before he became an urbanist superstar. The prompt was,

Is it possible to measure or estimate the train capacity of a transit line? Ie: How do I find the capacity of the New Haven line based on daily train trips, etc? Trying to see how much housing can be built on existing rail lines without the need for adding more trains

To be clear, Hayden was not talking about the capacity of the line but about that of trains. So adding peak service beyond what exists and is programmed (with projects like Penn Station Access) is not part of the prompt. The answer is that,

- There isn’t really a single number (this is a trip generation question).

- Moreover, under the assumption of status quo service on commuter rail, development near stations would not be transit-oriented.

Trip generation refers to the formula connecting the expected car trips generated by new development. It, and its sibling parking generation, is used in transportation planning and zoning throughout the United States, to limit development based on what existing and planned highway capacity can carry. Shoup’s paper explains how the trip and parking generation formulas are fictional, fitting a linear curve between the size of new development and the induced number of car trips and parked cars out of extremely low correlations, sometimes with an R^2 of less than 0.1, in one case with a negative correlation between trip generation and development size.

I encourage urbanists and transportation advocates and analysts to read Shoup’s original paper. It’s this insight that led him to examine parking requirements in zoning codes more carefully, leading to his book The High Cost of Free Parking and then many years of advocacy for looser parking requirements.

I bring all of this up because Hayden is essentially asking a trip generation question but on trains, and the answer there cannot be any more definitive than for cars. It’s not really possible to control what proportion of residents of new housing in a suburb near a New York commuter rail stop will be taking the train. Under current commuter rail service, we should expect the overwhelming majority of new residents who work in Manhattan to take the train, and the overwhelming majority of new residents who work anywhere else to drive (essentially the only exception is short trips on commuter rail, for example people taking the train from suburbs past Stamford to Stamford; those are free from the point of view of train capacity). This is comparable mode choice to that in the trip and parking generation tables, driven by an assumption of no alternative to driving, which is correct in nearly all of the United States. However, figuring out the proportion of new residents who would be commuting to Manhattan and thus taking the train is a hard exercise, for all of the following reasons:

- The great majority of suburbanites do not work in the city. For example, in the Western Connecticut and Greater Bridgeport Planning Regions, more or less coterminous with Fairfield County, 59.5% of residents work within one of these two regions, and only 7.4% work in Manhattan as of 2022 (and far fewer work in the Outer Boroughs – the highest number, in Queens, is 0.7%). This means that every new housing unit in the suburbs, even if it is guaranteed the occupant works in Manhattan, generates demand for more destinations within the suburb, such as retail and schools.

- The decision of a city commuter to move to the suburbs is not driven by high city housing prices. The suburbs of New York are collectively more expensive to live in than the city, and usually the ones with good commuter rail service are more expensive than other suburbs. Rather, the decision is driven by preference for the suburbs. This means that it’s hard to control where the occupant of new suburban housing will work purely through TOD design characteristics such as proximity to the station, streets with sidewalks, or multifamily housing.

- Among public transportation users, what time of day they go to work isn’t controllable. Most likely they’d commute at rush hour, because commuter rail is marginally usable off-peak, but it’s not guaranteed, and just figuring the proportion of new users who’d be working in Manhattan at rush hour is another complication.

All of the above factors also conspire to ensure that, under the status quo commuter rail service assumption, TOD in the suburbs is impossible except perhaps ones adjacent to the city. In a suburb like Westport, everyone is rich enough to afford one car per adult, and adding more housing near the station won’t lower prices by enough to change that. The quality of service for any trip other than a rush hour trip to Manhattan ranges from low to unusable, and so the new residents would be driving everywhere except their Manhattan job, even if they got housing in a multifamily building within walking distance of the train station.

This is a frustrating answer, so perhaps it’s better to ask what could be modified to ensure that TOD in the suburbs of New York became possible. For this, I believe two changes are required:

- Improvements in commuter rail scheduling to appeal to the growing majority of off-peak commuters as well as to non-commute trips. I’ve written about this repeatedly as part of ETA but also the high-speed rail project for the Transit Costs Project.

- Town center development near the train station to colocate local service functions there, including retail, a doctor’s office and similar services, a library, and a school, with the residential TOD located behind these functions.

The point of commercial and local service TOD is to concentrate destinations near the train station. This permits trip chaining by transit, where today it is only viable by car in those suburbs. This also encourages running more connecting bus service to the train station, initially on the strength of low-income retail workers who can’t afford a car, but then as bus-rail connections improve also for bus-rail commuters. The average income of a bus rider would remain well below that of a driver, but better service with timed connections to the train would mean the ridership would comprise a broader section of the working class rather than just the poor. Similarly, people who don’t drive on ideological or personal disability grounds could live in a certain degree of comfort in the residential TOD and walk, and this would improve service quality so that others who can drive but sometimes choose not to could live a similar lifestyle.

But even in this scenario of stronger TOD, it’s not really possible to control train capacity through zoning. We should expect this scenario to lead to much higher ridership without straining capacity, since capacity is determined by the peak and the above outline leads to a community with much higher off-peak rail usage for work and non-work trips, with a much lower share of its ridership occurring at rush hour (New York commuter rail is 67-69%, the SNCF part of the RER and Transilien are about 46%, due to frequency and TOD quality). But we still have no good way of controlling the modal choice, which is driven by personal decisions depending on local conditions of the suburb, and by office growth in the city versus in the suburbs.

Timetable Padding Practices

Two weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal wrote this piece about our Northeast Corridor report. Much of it was based on a series of interviews William Boston did with me, explaining what the main needs on the corridor are. One element stands out since the MTA responded to what I was saying about schedule padding – I talk about how Amtrak and Metro-North both pad the timetables on the Northeast Corridor by about 25%, turning a technical travel time of an hour into 1:15 (best practices are 7%), and in response, the MTA said that they pad their schedules 10% and not 7%. This is an incorrect understanding of timetable padding, which speaks poorly to the competence of the schedule planners and managers at Metro-North.

The article says,

Aaron Donovan, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, says the extra time built into Metro-North schedules generally averages 10%, depending on destination and length of trips, and takes into account routine track maintenance and capital work that can increase runtime. Metro-North continually reviews models, signal timing, equipment, and other elements of operation to improve travel times and reliability for customers, he says.

This is, to be clear, incorrect. Metro-North routinely recovers longer delays than 10%; delay recovery on the New Haven Line can reach well over 20 minutes out of a nominally two-hour trip, around 25% of the unpadded trip length. The reason this is incorrect isn’t that Donovan is dishonest or incompetent (he is neither of these two things), but almost certainly that the planners he spoke with genuinely believe they only pad 10%, because they, like all American railroaders, do not know how modern rail scheduling is done.

Modern rail scheduling practices in the higher-reliability parts of Europe and Japan start with the technical timetable, based on the actual speed zones and trains’ performance characteristics. This includes temporary speed restrictions. The ideal maintenance regime does not use them, instead relying on regular nighttime maintenance windows during which all tracks are out of service. However, temporary restrictions may exist if a line is taken out of service and trains are rerouted along a slower route, which is regrettably common in Germany. Modern signaling systems are capable of incorporating temporary speed restrictions – this is in fact a core requirement for American positive train control (PTC), since American maintenance practices rely on extensive temporary restrictions for work zones and one-off slowdowns. If the signal system knows the exact speed zones on each section of track, then so can the schedule planners.

The schedule contingency figure is computed relative to the best technical schedule. It is not computed relative to any assumption of additional delays due to dispatch holds or train congestion. The 7% figure used in Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands takes care of the high levels of congestion on key urban segments.

The core urban networks in these countries stack favorably with Metro-North in track utilization. The Hirschengraben Tunnel in Zurich runs 18 S-Bahn trains per hour in each direction most of the day and 20 at rush hour with some extra S20 runs, and the Weinberg Tunnel runs 8 S-Bahn trains per hour and if I understand the network graphic right 7.5 additional intercities per hour. I urge people to go look at the graphic and try tracking down the lines just to see how extensively branched and reverse-branched they are; this is not a simple network, and delays would propagate. The reason the Swiss rail network is so punctual is that, unlike American rail planning, it integrates infrastructure and timetable development. This means many things, but what is relevant here is that it analyzes where delays originate and how they propagate, and focuses investments on these sections, grade-separating problematic flat junctions if possible and adding pocket tracks if not.

Were I to only take timetable padding into account relative to an already more tolerant schedule incorporating congestion and signaling limitations, I would cite much lower figures for timetable padding. Switzerland speaks of a uniform 7% pad, but in Sweden the figures include two components, a percentage (taking care of, among other things, suboptimal driver behavior) and a fixed number of minutes per 100 km, which at current intercity speeds resolve to 7% as in Switzerland. But relative to the technical trip time, the pad factors based on both observed timetable recovery and actual calculations on current speed zones are in the 20-30% range, and not 10%.

Of course, at no point do I suggest that Metro-North and Amtrak could achieve 7% right now, through just writing more aggressive timetables. To achieve Swiss, Dutch, and Swedish results, they would need Swiss, Dutch, or Swedish planning quality, which is sorely lacking at both railroads. They would need to write better timetables – not just more aggressive ones but also simpler ones: Metro-North’s 13 different stopping patterns on New Haven Line trains out of 16 main line peak trains per hour should be consolidated to 2. This is key to the plan – the only way Northern Europe makes anything work is with fairly rigid clockface timetables, so that one hour or half-hour is repeated all day, and conflicts can be localized to be at the same place every time.

Then they would need to invest based on reliability. Right now, the investment plans do not incorporate the timetable, and one generally forward-thinking planner found it odd that the NEC report included both high-level infrastructure proposals and proposed timetables to the minute. In the United States, that’s not the normal practice – high-level plans only discuss high-level issues, and scheduling is considered a low-level issue to be done only after the concrete is completed. In Northern European countries with competently-run railways and also in Germany, the integration of the timetable and infrastructure is so complete that draft network graphics indicating complete timetables of every train to the minute are included in the proposal phase, before funding is committed. In Switzerland, such a timetable is available before the associated infrastructure investments go to referendum.

Under current American planning, the priorities for Metro-North are in situ bridge replacements in Connecticut because their maintenance costs are high even by Metro-North’s already very expensive standards. But under good planning, the priority must be grade-separating Shell Interlocking (CP 216) just south of New Rochelle, currently a flat junction between trains bound for Grand Central and ones bound for Penn Station. The flat junctions to the branches in Connecticut need to be evaluated for grade-separation as well, and I believe the innermost, to the New Canaan Branch, needs to be grade-separated due to its high traffic while the ones to the two farther out branches can be kept flat.

None of this is free, but all of this is cheap by the standards of what the MTA is already spending on Penn Station Access for Metro-North. The rewards are substantial: 1:17 trip times from New Haven to Grand Central making off-peak express stops, down from 2 hours today. The big ask isn’t money – the entire point of the report is to figure out how to build high-speed rail on a tight budget. Rather, the big ask is changing the entire planning paradigm of intercity and commuter rail in the United States from reactive to proactive, from incremental to comfortable with groun-up redesigns, from stuck in the 1950s to ready for the transportation needs of the 21st century.

How One Bad Project Can Poison the Entire Mode

There are a few examples of rail projects that fail in a way that poisons the entire idea among decisionmakers. The failures can be total, to the point that the project isn’t built and nobody tries it again. Or the outcome can be a mixed blessing: an open project with some ridership, but not enough compared with the cost or hassle, with decisionmakers still choosing not to do this again. The primary cases I have in mind are Eurostar and Caltrain electrification, both mixed blessings, which poisoned international high-speed rail in Europe and rail electrification in the United States respectively. The frustrating thing about both projects is that their failures are not inherent to the mode, but rather come from bad project management and delivery, which nonetheless is taken as typical by subsequent planners, who benchmark proposals to those failed projects.

Eurostar: Flight Level Zero airline

The infrastructure built for Eurostar is not at all bad: the Channel Tunnel, and the extensions of the LGV Nord thereto and to Brussels. The UK-side high-speed line, High Speed 1, had very high construction costs (about $160 million/km in today’s prices), but it’s short enough that those costs don’t matter too much. The concept of connecting London and Paris by high-speed rail is solid, and those trains get a strong mode share, as do trains from both cities to Brussels.

Unfortunately, the operations are a mess. There’s security and border control theater, which is then used as an excuse to corral passengers into airline-style holding areas with only one or two boarding queues for a train of nearly 1,000 passengers. The extra time involved, 30 minutes at best and an hour at worst, creates a serious malus to ridership – the elasticity of ridership with respect to travel time in the literature I’ve seen ranges from -1 to -2, and at least in the studies I’ve read about local transit, time spent out of vehicle usually counts worse than time spent on a moving train (usually a factor of 2). It also holds up tracks, which is then used as an excuse not to run more service.

The excusemaking about service is then used to throttle the service offer, and raise prices. As I explain in this post, the average fare on domestic TGVs is 0.093€/passenger-km, whereas that on international TGV services (including Eurostar) is 0.17€/p-km, with the Eurostar services costing more than Lyria and TGV services into Germany. This includes both Eurostar to London and the services between Paris and Brussels, which used to be called Thalys, which have none of the security and border theater of London and yet charge very high fares, with low resulting ridership.

The origin of this is that Eurostar was conceived as a partnership between British and French elites, in management as well as the respective states. They thought of the Chunnel as a flashy project, fit for high-end service, designed for business travelers. SNCF management itself believes in airline-style services, with fares that profiteer off of riders; it can’t do it domestically due to public pressure to keep the TGV affordable to the broad public, but whenever it is freed from this pressure, it builds or recommends that others build what it thinks trains should be like, and the results are not good.

What rail advocates have learned from this saga is that cross-border rail should decenter high-speed rail. Their first association of cross-border high-speed rail is Eurostar, which is unreasonably expensive and low-ridership even without British border and security theater. Thus, the community has retreated from thinking in terms of infrastructure, and is trying to solve Eurostar’s problem (not enough service) even on lines where they need competitive trip times before anything else. Why fight for cross-border high-speed rail if the only extant examples are such underperformers?

This dovetails with the mentality that private companies do it better than the state, which is dominant at the EU level, as the eurocrats prefer not to have any visible EU state. This leads to ridiculous press releases by startups that lie to the public or to themselves that they’re about to launch new services, and consultant slop that treats rail services as if they are airlines with airline cost structures. Europe itself gave up on cross-border rail infrastructure – the EU is in panic mode on all issues, the states that would be building this infrastructure (like Belgium on Brussels-Antwerp) don’t care, and even bilateral government agreements don’t touch the issue, for example France and Germany are indifferent.

Caltrain: electrification at extreme costs

In the 2010s, Caltrain electrified its core route from San Francisco to Tamien just south of San Jose Diridon Station, a total length of 80 km, opening in 2024. This is the only significant electrification of a diesel service in the United States since Amtrak electrified the Northeast Corridor from New Haven to Boston in the late 1990s. The idea is excellent: a dense corridor like this with many stations would benefit greatly from all of the usual advantages of electrification, including less pollution, faster acceleration, and higher reliability.

Unfortunately, the costs of the project have been disproportionate to any other completed electrification program that I am aware of. The entire Caltrain Modernization Project cost $2.4 billion, comprising electrification, resignaling (cf. around $2 million/km in Denmark for ETCS Level 2), rolling stock, and some grade crossing work. Netting out the elements that are not direct electrification infrastructure, this is till well into the teens of millions per kilometer. Some British experiments have come close, but the RIA Electrification Challenge overall says that the cost on double track is in the $3.8-5.7 million/km range in today’s prices, and typical Continental European costs are somewhat lower.

The upshot is that Americans, never particularly curious about the world outside their border, have come to benchmark all electrification projects to Caltrain’s costs. Occasionally they glance at Canada, seeing Toronto’s expensive electrification project and confirming their belief that it is far too expensive. They barely look at British electrification projects, and never look at ones outside the English-speaking world. Thus, they take these costs as a given, rather than as a failure mode, due to poor design standards, poor project management, a one-off signaling system that had very high costs by American standards, and inflexible response to small changes.

And unfortunately, there was no pot of gold at the end of the Caltrain rainbow. Ridership is noticeably up since electric service opened, but is far below pre-corona levels, as the riders were largely tech workers and the tech industry went to work-from-home early and has still not quite returned to the office, especially not in the Bay Area. This one failure, partly due to unforeseen circumstances, partly due to poor management, has led to the poisoning of overhead wire electrification throughout the United States.

S-Bahn and RER Ridership is Urban

People in my comments and on social media are taking it for granted that investments into modernizing commuter rail predominantly benefit the suburbs. Against that, I’d like to point out how on the modern commuter rail systems I know best – the RER and the Berlin S-Bahn – ridership is predominantly urban. Whereas the typical American commuter rail use case is a suburban resident commuting to a central business district job at rush hour, the typical use case on the commuter trains here is an urban resident going to work or a social outing in or near city center. Suburban ridership is strong by American standards, benefiting from being able to piggyback on the high frequency and levels of physical investment produced by the urban ridership.

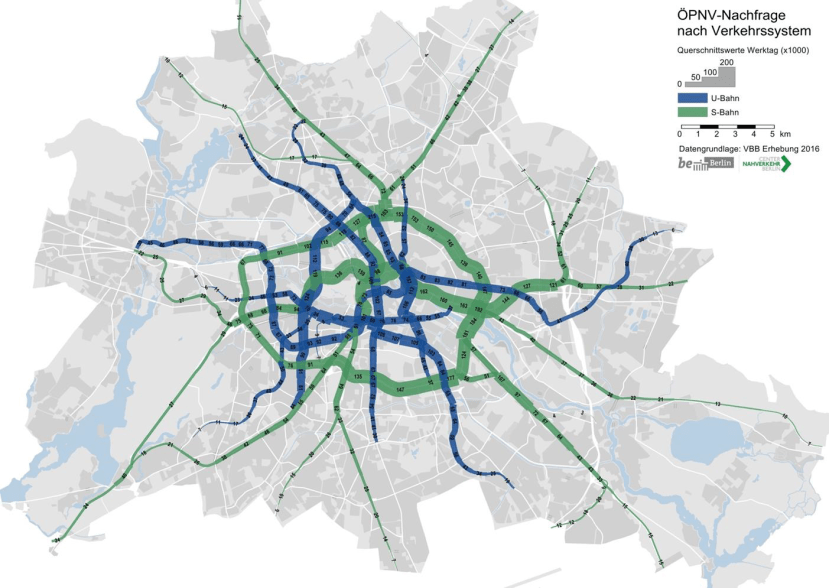

Here’s Berlin’s passenger traffic density on the U- and S-Bahn, as of 2016 (source, p. 6):

The busiest section of the S-Bahn is the Stadtbahn from Ostkreuz to Hauptbahnhof, with about 160,000 passengers per weekday through each interstation. The eastern sections of both the north and the south arms of the Ringbahn are close, with about 150,000 each, and the North-South Tunnel has 100,000. These traffic density levels extend into outer urban neighborhoods outside the ring – ridership on the Stadtbahn trunk remains high well into Lichtenberg – but by the time the trains cross city limits, ridership is rather low. All tails crossing city limits combined have 150,000 riders/day, so a little more than a quarter of the ridership density on the city center segments. Of those tails, the busiest, with a traffic density of 24,000/day, is to Potsdam, which is a suburb but is an independent job center rather than a pure commuter suburb like the rest of the towns in Brandenburg adjacent to Berlin.

I don’t have similar graphics for Paris, only a table of ridership on the SNCF-RER and Transilien by station and time of day and a separate table with annual ridership on the RATP-RER and Métro. But the results there are similar. Total boardings on the RATP-RER in 2019 was 399 million, of which 52 million originated in stations in the Grande Couronne, 186 million in the Petite Couronne, and 161 million in the city. If we double the Grande Couronne boardings, to account for the fact that just about all of those riders are going to the city or a Petite Couronne job center like La Défense, then we get just over a quarter of overall ridership, a similar result to the traffic density of Berlin. On the SNCF-RER, the share of the Grande Couronne is higher, around half.

The city stations include job centers and transfer points from mainline rail and the Métro – there aren’t 47 million people a year whose residential origin station is Gare du Nord – so it’s best to view the system as one used predominantly by Petite Couronne residents, with a handful using it as I did internally to the city and another handful commuting in from the Grand Couronne. This is technically suburban, but the Petite Couronne is best viewed as a ring of city neighborhoods that are not annexed to the city for sociopolitical reasons; the least dense of its three departments, Val-de-Marne, is denser than the densest German city, Munich.

The difference in this pattern with the United States is not hard to explain. Here and in Paris, commuter rail charges the same fares as the subway, runs every 5-10 minutes in urban neighborhoods (even less on the city center trunks), and makes stops at the rate of an express subway line. Of course urban residents use the trains, and we greatly outnumber suburbanites among people traveling to city center. It’s the United States that’s weird, with its suburb-only rail system stuck in the Mad Men era trying to stick with its market of Don Drapers and Pete Campbells.

Quick Note: RER and S-Bahn Line Length

An email correspondent asks me about whether cities should build subway or commuter rail lines, and Adirondacker in comments frequently compares the express lines in New York to the RER. So to showcase the difference, here are some lines with their lengths. The length is measured one-tailed, from a chosen central point.

| Line | Central point | Length (km) |

| RER A to MLV | Les Halles | 37 |

| RER A to Cergy | Les Halles | 40.5 |

| RER B to CDG | Les Halles | 31 |

| RER B to Saint-Rémy | Les Halles | 32.5 |

| RER D to Malesherbes | Les Halles | 79 |

| Crossrail to Shenfield | Farringdon | 34 |

| Crossrail to Reading | Farringdon | 62.5 |

| Thameslink to Brighton | Farringdon | 81 |

| Thameslink to Bedford | Farringdon | 82 |

Express subway lines in New York never go that far; the A train, the longest in the system, is 50 km two-tailed, and not much more than 30 km one-tailed to Far Rockaway. The Berlin S-Bahn is about comparable, in a metro area one quarter the size.

The Danbury Branch and Rail Modernization

I’ve been asked to talk about how rail modernization programs, like the high-speed rail plan we published at Marron this month, affect the Danbury Branch of the New Haven Line. The proposal barely talks about branch modernization beyond saying that the branches should be electrified; we didn’t have time to write precise branch timetables, which means that the timetable I’m going to post here is going to have more rounding artifacts. The good news is that modernization can be done cheaply, piggybacking on required work on the main of the New Haven Line.

Current conditions

The Danbury Branch is a 38 km single-track unelectrified line, connecting South Norwalk with Danbury making six additional intermediate stops. All stations have high platforms, but they are short, ranging between three and six cars.

Ridership is essentially unidirectional: toward Norwalk and New York in the morning, back north in the afternoon. There is little job concentration near the stations. Within 1 km of Danbury there are only 5,000 jobs per OnTheMap, rising to 10,000 if we include Danbury Hospital, which is barely outside the station’s 1 km radius (but is not easily walkable from it). Merritt 7 is in an office park, but there are only 6,000 jobs there, and nearly everyone drives. The other stations are parking lots, and Bethel is somewhat outside the town center for better parking.

The right-of-way is very curvy, much more so than the main line. Where most of the New Haven Line is built to a standard of 2° curves (radius 873 m), permitting 157 km/h with modern cant and cant deficiency, the Danbury Branch scarcely has a section straight enough with gentler curves than 3°, and much of it has such frequent 4° curves that trains cannot go faster than 100 km/h except for speedups of a few seconds at a time to recover delays.

A first pass on infrastructure and operations

It is effectively free to electrify a 38 km single-track line. The high-speed rail report estimates it at $75 million based on both European electrification costs (see report for sources) and the Southern Transcon proposal, which is $2 million/km on a busy double-track line. The junction between the branch and the main line is flat, but outbound trains can be timetabled to avoid conflict, and inbound trains have no at-grade conflict to begin with. If platform lengthening is desired, then it is a noticeable extra expense; figure $30 million for each eight-car platform, or perhaps half that on single track (but then some stops are double-track), maybe with some pro-rating for existing platforms if they can be easily reused.

The tracks should also be maintained to higher speed, which is a routine application of a track laying machine, with some weekend closures for construction followed by what should be an uninterrupted multidecade period of operations. The curves are already superelevated to a maximum of 5-6″; this is less than the 7″ maximum in US law (180 mm here), but the difference is not massive. The line has a 50 mph speed limit today for the most part, whereas it can be boosted to about 100-110 km/h depending on section, a smaller difference than taking the main line’s 70 mph and turning it into 150-160 km/h.

With a blanket speed limit of 110 km/h – in truth some sections need to dip down to 100 or even less whereas the Bethel-Danbury and Merritt 7-Wilton interstations can be done mostly at 130 – the trip time between South Norwalk and Danbury is, inclusive of 7% pad, 28.75 minutes. The Northeast Corridor report timetables have express New Haven Line commuter trains arriving South Norwalk southbound at :15.25 every 20 minutes and departing northbound at :14.75, so they’d be departing Danbury at :46.5 and arriving :43.5. Meets would occur at the :20, :30, and :40 points.

The :30 point, important as it is a meet even if service is reduced to every 30 minutes, is just south of Branchville, likely too far to use the existing meet at the station. Thus, at first pass, some additional double-tracking is needed, a total of 6 km if it covers the entire Cannondale-Branchville interstation, which would cost around $50 million at MBTA Franklin Line costs. MBTA Franklin Line costs are likely an underestimate, since the terrain on the Cannondale-Branchville interstation is hillier and some additional earthworks would be required on part of the section. A high-end estimate should be the cost of a high-speed rail line without elevated or tunneled segments, around $30 million/km or even less (cut-and-fill isn’t needed as much when the line curves with the topography), say $150 million.

The :20 point southbound is at or just south of Bethel. While this is in a built-up area, the right-of-way looks wide enough for two tracks and the topography is easier; if the station is the meet, then the cost is effectively zero, bundled into a platform lengthening project. Potentially, this could even be further bundled with moving the station slightly south to be closer to the town center. The :40 point southbound is at Merritt 7, which has room for a second track but not necessarily for a platform at it, and could instead get a second track on the opposite side of the platform if there’s enough of a rebuild to turn it into an island with additional vertical circulation; the cost of the second track itself would be a rounding error but the cost of station reconstruction would not be and would likely be in the mid-tens of millions.

How this fits into the broader system

The timetable in the report already assumes that New Haven Line service comprises 6 peak trains per hour (tph) that use the branches. The default assumption, reproduced in the service network graphic, is that New Canaan and Danbury get 3 tph each, and New Canaan gets a grade-separated junction but Danbury does not. Those trains all go to Grand Central with no through-running: only the local trains on the New Haven Line get to run through, since local trains are the highest priority for through-running. If a tunnel connecting the Gateway tunnel with Grand Central is opened, as in some long-term plans (here’s ETA’s, which isn’t very different from past blog posts’), then they can run through to it.

The establishment of this service is not going to, by itself, change the characteristic of ridership on the line. Electrification, better timetabling, and better rolling stock (in this order) can reduce the trip time from an hour today to 29 minutes, and the trip time to Grand Central from about 2:25 to 1:09, but the main effect would be to greatly improve the connectivity of existing users, who’d be driving to the parking lot stations more often, perhaps working from the office more and from home less, or taking the train to social events in the city. Some would opt to use the train to get to work at Stamford, as a secondary market. Over time, I expect that people would buy in the area to commute to work in New York (or at Stamford), but housing permit rates in Fairfield County are low and only limited TOD is likely. It would take concerted commercial TOD at the stations to produce reverse-peak ridership, likely starting with expanding the Merritt 7 office park and making it a bit less auto-oriented.

If the ridership isn’t there, then a train every 20 minutes is not warranted and only a train every 30 minutes should be provided. This reduces the double-track infrastructure requirement but only marginally, as the meets that are no longer needed are the easy ones and the one that still is is the hard one to build, south of Branchville. In effect, something like 80% of the cost provides two thirds of the capacity; this is common to rail projects, in that small cuts in an already optimized budget lead to much larger cuts in benefits, the opposite of what one hopes to achieve when optimizing cuts.

The Northeast Corridor Report is Out

Here is the link. If people have questions, please post them in comments and I’ll address; see also Bluesky thread (and Mastodon but there are no questions there yet).

Especial thanks go to everyone who helped with it – most of all Devin Wilkins for the tools, analysis, and coding work that produced the timetables, which, as the scheduling section says, are the final product as perceived by the passenger. Other than Devin, the other members of the TCP/TLU program at Marron gave invaluable feedback, and Elif has done extensive work with both typesetting and managing the still under-construction graphical narrative we’re about to do (expected delivery: mid-June). Members of ETA have looked over as well, and Madison and Khyber nitpicked the overhead electrification section in infrastructure investment until it was good. And finally, Cid was always helpful, whether with personal support, or with looking over the overview as a layperson.

Against State of Good Repair

We’re releasing our high-speed rail report later this week. It’s a technical report rather than a historical or institutional one, so I’d like to talk about a point that is mentioned in the introduction explaining why we think it’s possible to build high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor for $17 billion: the current investment program, Connect 2037, centers renewal and maintenance more than expansion, under the moniker State of Good Repair (SOGR). In essence, megaprojects have a set of well-understood problems of high costs and deficient outcomes, behind-the-scenes maintenance has a different set of problems, and SOGR combines the worst of both worlds and the benefits of neither. I’ve talked about this before in other contexts – about Connecticut rail renewal costs, or leakage in megaproject budgeting, or the history of SOGR on the New York City Subway, or Northeast Corridor catenary. Here I’d like to synthesize this into a single critique.

What is SOGR?

SOGR is a long-term capital investment to bring all capital assets into their expected lifespan and maintenance status. If a piece of equipment is supposed to be replaced every 40 years and is currently over 40, it’s not in good repair. If the mean distance between failures falls below a certain prescribed level, it’s not in good repair. If maintenance intervals grow beyond prescription, then the asset to be maintained is not in good repair. In practice, the lifespans are somewhat conservative so in practice a lot of things fall out of good repair and the system keeps running. The upshot is that because the maintenance standards are somewhat flexible, it’s easy to defer maintenance to make the system look financially healthier, or to deal with an unexpected budget shortfall.

Modern American SOGR goes back to the New York subway renewal programs of the 1980s and 90s, which worked well. The problem is that, just as the success of one infrastructure expansion tempts the construction of other, less socially profitable ones, the success of SOGR tempted agencies to justify large capital expenses on SOGR grounds. In effect, what should have been a one-time program to recover from the 1970s was generalized as a way of doing maintenance and renewal to react to the availability of money.

Megaprojects and non-megaprojects

In practice, what defines a megaproject is relative – a 6 km light rail extension is a megaproject in Boston but not in Paris – and this also means that they are not easy to locally benchmark, or else there would be many like them and they would be more routine. This means that megaprojects are, by definition, unusual. Their outcome is visible, and this attracts high-profile politicians and civil servants looking to make their mark. Conversely, their budgeting is less visible, because what must be included is not always clear. This leads to problems of bloat (this is the leakage problem), politicization, surplus extraction, and plain lying by proponents.

Non-megaprojects have, in effect, the opposite set of problems. Their individual components can be benchmarked easily, because they happen routinely. A short Paris Métro extension, a few new infill stations, and a weekend service change for track renewal in New York are all examples of non-megaprojects. These are done at the purely professional level, and if politicians or top managers intervene, it’s usually at the most general level, for example the institution of Fastrack as a general way of doing subway maintenance, and that too can be benchmarked internally. In this case, none of the usual problems of megaprojects is likely. Instead, problems occur because, while the budgeting can be visible to the agency, the project itself is not visible to the general public. If an entire new subway line’s construction fails and the line does not open, this is publicly visible, to the embarrassment of the politicians and agency heads who intended to take credit for it. In contrast, if a weekend service change has lower productivity than usual, the public won’t know until this problem has metastasized in general, by which point the agency has probably lost the ability to do this efficiently.

And to be clear, just as megaprojects like new subway lines vary widely in their ability to build efficiently, so do non-megaproject capital investments vary, if anything even more. The example I gave writing about Connecticut’s ill-conceived SOGR program, repeated in the high-speed rail report, is that per track- or route-km the state spends in one year about 60% as much as what Germany spends on a once per generation renewal program, to be undertaken about every 35 years. Annually, the difference is a factor of about 20. New York subway maintenance has degraded internally over time, due to ever tighter flagging rules, designed for worker protection, except that worker injuries rose from 1999 to the 2010s.

The Transit Costs Project

The goal of the Transit Costs Project is to use international benchmarking to allow cities to benefit from the best of both worlds. Megaprojects benefit from public visibility and from the inherent embarrassment to a politician or even a city or state that can’t build them: “New York can’t expand the subway” is a common mockery in American good-government spaces, and people in Germany mock both Bavaria for the high costs and long timeline of the second Munich S-Bahn tunnel and Berlin for, while its costs are rather normal, not building anything, not even the much-promised tram alternatives to the U-Bahn. Conversely, politicians do get political capital from the successful completion of a megaproject, encouraging their construction, even when not socially profitable.

Where we come in is using global benchmarking to remove the question marks from such projects. A subway extension may be a once in a generation effort in an American city, but globally it is not, and therefore, we look into how as much of the entire world as we can see into does this, to establish norms. This includes station designs to avoid overbuilding, project delivery and procurement strategies, system standards, and other aspects. Not even New York is as special as it thinks it is.

To some extent, this combination of the best features of both megaprojects and non-megaprojects exists in cities with low construction costs. This is not as tautological as it sounds. Rather, I claim that when construction costs are low, even visible extensions to the system fall below the threshold of a megaproject, and thus incremental metro extensions are built by professionals, with more public visibility providing a layer of transparency than for a renewal project. This way, growth can sustain itself until the city runs out of good places to build or until an economic crisis like the Great Recession in Spain makes nearly all capital work stop. In this environment, politicians grow to trust that if they want something big built, they can just give more money to more of the same, serving many neighborhoods at once.

In places with higher costs, or in places that are small enough that even with low costs it’s rare to build new metro lines, this is not available. This requires the global benchmarking that we use; occasionally, national benchmarking could work, in a country with medium costs and low willingness to build (for example, Germany), but this isn’t common.

The SOGR problem

If what we aim to do with the Transit Costs Project is to combine the positive features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects, SOGR does the exact opposite. It is conceived as a single large program, acting as the centerpiece of a capital plan that can go into the tens of billions of dollars, and is therefore a megaproject. But then there’s no visible, actionable, tangible promise there. There is no concrete promise of higher speed or capacity. To the extent some programs do have such a promise, they are subsumed into something much bigger, which means that failing to meet standards on (say) elevator reliability can be excused if other things are said to go into a state of good repair, whatever that means to the general public.

Thus, SOGR invites levels of bloat going well beyond those of normal expansion megaprojects. Any project can be added to the SOGR list, with little oversight – it isn’t and can’t be locally benchmarked so there is no mid-career professional who can push back, and conversely it isn’t so visible to the general public that a general manager or politician can push back demanding a fixed opening deadline. For the same reason, inefficiency can fester, because nobody at either the middle or upper level has the clear ability to demand better.

Worse, once the mentality of SOGR is accepted, more capital projects, on either the renewal side or the expansion side, are tied to it, reducing their efficiency. For example, the catenary on the Northeast Corridor south of New York requires an upgrade from fixed termination/variable tension to auto-tension/constant tension. But Amtrak has undermaintained the catenary expecting money for upgrades any decade now, and now Amtrak claims that the entire system must be replaced, not just the catenary but also the poles and substations. The language used, “the system is falling apart” and “the system is maintained with duct tape,” invites urgency, and not the question, “if you didn’t maintain this all this time, why should we trust you on anything?”. With the skepticism of the latter question, we can see that the substations are a separate issue from the catenary, and ask whether the poles can be rebuilt in place to reduce disruption, to which the vendors I’ve spoken with suggested the answer is yes using bracing.

The Connecticut track renewal program falls into the same trap. With no tangible promise of better service, the state’s rail lines are under constant closures for maintenance, which is done at exceptionally low productivity – manually usually, and when they finally obtained a track laying machine recently they’ve used it at one tenth its expected productivity. Once this is accepted as the normal way of doing things, when someone from the outside suggests they could do better, like Ned Lamont with his 30-30-30 proposal, the response is to make up excuses why it’s not possible. Why disturb the racket?

The way forward

The only way forward is to completely eliminate SOGR from one’s lexicon. Big capital programs must exclusively fund expansion, and project managers must learn to look with suspicion on any attempt to let maintenance projects piggyback on them.

Instead, maintenance and renewal should be budgeted separately from each other and separately from expansion. Maintenance should be budgeted on the same ongoing basis as operations. If it’s too expensive, this is evidence that it’s not efficient enough and should be mechanized better; on a modern railroad in a developed country, there is no need to have maintenance of way workers walk the tracks instead of riding a track inspection train or a track laying machine. With mechanized maintenance, inventory management is also simplified, in the sense that an entire section of track has consistent maintenance history, rather than each sleeper having been installed in a different year replacing a defective one.

Renewal can be funded on a one-time basis since the exact interval can be fudged somewhat and the works can be timed based on other work or even a recession requiring economic stimulus. But this must be held separate from expansion, again to avoid the Connecticut problem of putting the entire rail network under constant maintenance because slow zones are accepted as a fact of life.

The importance of splitting these off is that it makes it easier to say “no” to bad expansion projects masquerading as urgent maintenance. No, it’s not urgent to replace a bridge if the cost of doing so is $1 billion to cross a 100 meter wide river. No, the substations are a separate system from the overhead catenary and you shouldn’t bundle them into one project.

With SOGR stripped off, it’s possible to achieve the Transit Costs Project goal of combining the best rather than the worst features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects. High-speed rail is visible and has long been a common ask on the Northeast Corridor, and with the components split off, it’s possible to look into each and benchmark to what it should include and how it should be built. Just as New York is not special when it comes to subways, the United States is not special when it comes to intercity rail, it just lags in planning coordination and technology. With everything done transparently based on best practices, it is indeed possible to build this on an expansion budget of about $17 billion and a rounding-error track laying machine budget.