As part of our high-speed rail program at Marron, I designed and other people made a 3D model of the train station I referenced in 2015 in what was originally a trollish proposal, upgraded to something more serious. For now there’s still a password: letsredothis. This is a playable level, so have a look around.

The playable 3D model shows what Penn Station could look like if it were rebuilt from the ground up, based on best industry practices. It is deliberately minimalistic: a train station is an interface between the train and the city it serves, and therefore its primary goal is to get passengers between the street or the subway and the platform as efficiently as possible. But minimalism should not be conflated with either architectural plainness (see below on technical limitations) or poor passenger convenience. The open design means that pedestrian circulation for passengers would be dramatically improved over today’s infamously cramped passageways.

Much of the design for this station is inspired by modern European train stations, including Berlin Hauptbahnhof (opened 2006), the under-construction Stuttgart 21 (scheduled to open 2025), and the reconstruction of Utrecht Central (2013-16); Utrecht, in turn, was inspired by the design of Shinagawa in Tokyo.

As we investigate which infrastructure projects are required for a high-speed rail program in the Northeast, we will evaluate the place of this station as well. Besides intangible benefits explained below in background, there are considerable tangible benefits in faster egress from the train to the street.

Moreover, the process that led to this blueprint and model can be reused elsewhere. In particular, as we explain in the section on pedestrian circulation, elements of the platform design should be used for the construction of subway stations on some lines under consideration in New York and other American cities, to minimize both construction costs and wasted time for passengers to navigate underground corridors. In that sense, this model can be viewed not just as a proposal for Penn Station, but also as an appendix to our report on construction costs.

Background

New York Penn Station is unpopular among users, and has been since the current station opened in 1968 (“One entered the city like a God; one scuttles in now like a rat” -Vincent Scully). From time to time, proposals for rebuilding the station along a better or grander design have been floated, usually in connection with a plan for improving the track level below.

Right now, such a track-level improvement is beginning construction, in the form of the Gateway Project and its Hudson Tunnel Project (HTP). The purpose of HTP is to add two new tracks’ worth of rail capacity from New Jersey to Penn Station; currently, there are only two mainline tracks under the Hudson, the North River Tunnels (NRT), with a peak throughput of 24 trains per hour across Amtrak’s intercity trains and New Jersey Transit’s (NJT) commuter trains, and very high crowding levels on the eve of the pandemic; 24 trains per hour is usually the limit of mainline rail, with higher figures only available on more self-contained systems. In contrast, going east of Penn Station, there are four East River Tunnel (ERT) tracks to Long Island and the Northeast Corridor, with a pre-corona peak throughput of not 48 trains per hour but only about 40.

Gateway is a broader project than HTP, including additional elements on both the New Jersey and Manhattan sides. Whereas HTP has recently been funded, with a budget of $14-16 billion, the total projected cost of Gateway is $50 billion, largely unfunded, of which $20 billion comprises improvements and additions to Penn Station, most of which are completely unnecessary.

Those additions include the $7 billion Penn Reconstruction and the $13 billion Penn Expansion. Penn Reconstruction is a laundry list of improvements to the existing Penn Station, including 29 new staircases and escalators from the platforms to the concourses, additional concourse space, total reconstruction of the upper concourse to simplify the layout, and new entrances from the street to the station. It’s not a bad project, but the cost is disproportionate to the benefits. Penn Expansion would build upon it and condemn the block south of the station, the so-called Block 780, to excavate new tracks; it is a complete waste of money even before it has been funded, as scarce planner resources are spent on it.

The 3D model as depicted should be thought of as an alternative form of Penn Reconstruction, for what is likely a similar cost. It bakes in assumptions on service, as detailed below, that assume both commuter and intercity trains run efficiently and in a coordinated manner.

Station description

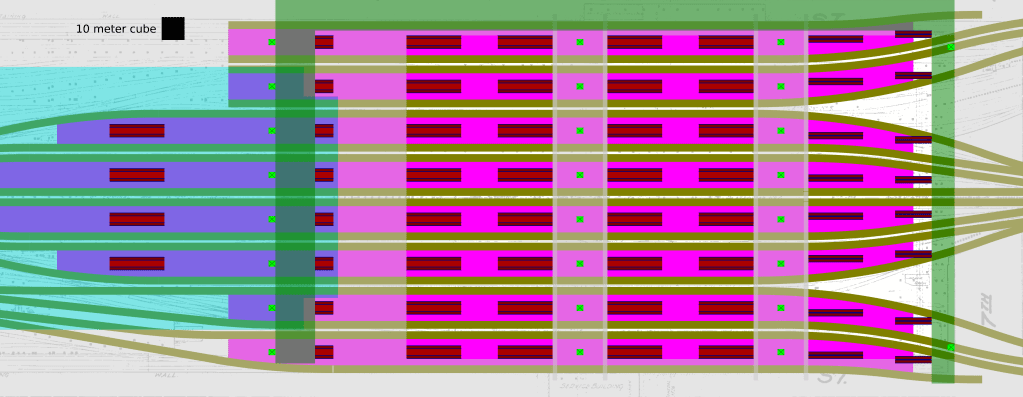

The station in the model is fully daylit, with no obstruction above the platforms. There are eight wide platforms and 16 tracks, down from 11 platforms and 21 tracks today. The station box is bounded by 7th Avenue, 31st Street, 8th Avenue, and 33rd Street, as today; also as today, the central platforms continue well to the west of 8th Avenue, using the existing Moynihan Train Hall. No expansion of the footprint is required. The existing track 1 (the southernmost) becomes the new track 1A and the existing track 21 becomes the new track 8B.

The removal of three platforms and five tracks and some additional track-level work combine to make the remaining platforms 11.5 meters wide each, compared with a range of 9-10 meters at some comparable high-throughput stations, such as Tokyo.

With wide platforms, the platforms themselves can be part of the station. A persistent difference between American and European train stations is that at American stations, even beloved ones like Grand Central, the station is near where the tracks are, whereas in Europe, the station is where the tracks are. Grand Central has a majestic waiting hall, but the tracks and platforms themselves are in cramped, dank areas with low ceilings and poor lighting. The 3D model, in contrast, integrated the tracks into the station structure: the model includes concessions below most escalator and stair banks, which could offer retail, fast food, or coffee. Ticketing machines can be placed throughout the complex, on the platforms as well as at places along the access corridors that are not needed for rush hour pedestrian circulation. This, more than anything, explains the minimalistic design, with no concourses: concourses are not required when there is direct access between the street and the platforms.

For circulation, there are two walkways, labeled East and West Walkways; these may be thought of as 7⅓th and 7⅔th Avenues, respectively. West End Corridor is kept, as is the circulation space under 33rd Street connecting West End Corridor and points east, currently part of the station concourse. A new north-south corridor called East End Corridor appears between the station and 7th Avenue, with access to the 1/2/3 trains.

What about Madison Square Garden?

Currently, Penn Station is effectively in the basement of Madison Square Garden (MSG) and Two Penn Plaza. Both buildings need to come down to build this vision.

MSG has come under attack recently for competing for space with the train station; going back to the early 2010s, plans for rebuilding Penn Station to have direct sunlight have assumed that MSG should move somewhere else, and this month, City Council voted to extend MSG’s permit by only five years and not the expected 10, in effect creating a five-year clock for a plan to daylight Penn Station. There have been recent plans to move MSG, such as the Vishaan Chakrabarti vision for Penn Station; the 3D model could be viewed as the rail engineering answer to that architecture-centric vision.

Two Penn Plaza is a 150,000 m^2 skyscraper, in a city where developers can build a replacement for $900 million in 2018 prices.

The complete removal of both buildings makes work on Penn Station vastly simpler. The station is replete with columns, obstructing sight lines, taking up space between tracks, and constraining all changes. The 3D model’s blueprint takes care to respect column placement west of 8th Avenue, where the columns are sparser and it’s possible to design tracks around them, but it is not possible to do so between 7th and 8th Avenues. Conversely, with the columns removed, it is not hard to daylight the station.

Station operations

The operating model at this station is based on consistency and simplicity. Every train has a consistent platform to use. Thus, passengers would be able to know their track number months in advance, just as in Japan and much of Europe, train reservations already include the track number at the station. The scramble passengers face at Penn Station today, waiting to see their train’s track number posted minutes in advance and then rushing to the platform, would be eliminated.

Each approach track thus splits into two tracks flanking the same platform. This is the same design used at Stuttgart 21 and Berlin Hauptbahnhof: if a last-minute change in track assignment is needed, it can be guaranteed to face the same platform, limiting passenger confusion. At each platform, numbered south to north as today, the A track is to the south of the B track, but the trains on the two tracks would be serving the same line and coming from and going to the same approach track. This way, a train can enter the A track at a station while the previous train is still departing the B track, which provides higher capacity.

The labels on the signage are by destination:

- Platform 1: eastbound trains from the HTP, eventually going to a through-tunnel to Grand Central

- Platform 2: westbound trains to the HTP, connecting from Grand Central

- Platform 3: eastbound trains from the preexisting North River Tunnels (NRT) to the existing East River Tunnels (ERT) under 32nd Street

- Platform 4: eastbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 5: westbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 6: westbound trains from the ERT under 32nd Street to the NRT

- Platform 7: eastbound trains to the ERT under 33rd Street and the LIRR, eventually connecting to a through-tunnel from the Hudson Line

- Platform 8: westbound trains from LIRR via the ERT under 33rd Street, eventually going to a through-tunnel to the Hudson Line

Signage labels except for the intercity platforms 4 and 5 state the name of the commuter railway that the trains would go to. Thus, a train from Trenton to Stamford running via the Northeast Corridor and the under-construction Penn Station Access line would use platform 3, and is labeled as Metro-North, as it goes toward Metro-North territory; the same train going back, using platform 6, is labeled as New Jersey Transit, as it goes toward New Jersey.

Such through-running is obligatory for efficient station operations. There are many good reasons to run through, which are described in detail in a forthcoming document by the Effective Transit Alliance. But for one point about efficiency, it takes a train a minimum of 10 minutes to turn at a train station and change direction in the United States, and this is after much optimization (Penn Station’s current users believe they need 18-22 minutes to turn). In contrast, a through-train can unload at even an extremely busy station like Penn in not much more than a minute; the narrow platforms of today’s station could clear a full rush hour train in emergency conditions today in about 3-4 minutes, and the wide platforms of the 3D model could do so in about 1.5 minutes in emergencies and less in regular operations.

Supporting infrastructure assumptions

The assumption for the model is that the HTP is a done deal; it was recently federally funded, in a way that is said to be difficult to repeal in the future in the event of a change in government. The HTP tunnel is slated to open in 2035; the current timetable is that full operations can only begin in 2038 after a three-year closure of NRT infrastructure for long-term repairs, but in fact those repairs can be done in weekend windows—indeed, present-day rail timetables through the NRT assume that one track is out for a 55-hour period each weekend, but investigative reporting has shown that Amtrak takes advantage of this outage only once every three months. If repairs are done every weekend, then it will be possible to refurbish the tunnels by 2035, for full four-track operations in 12 years.

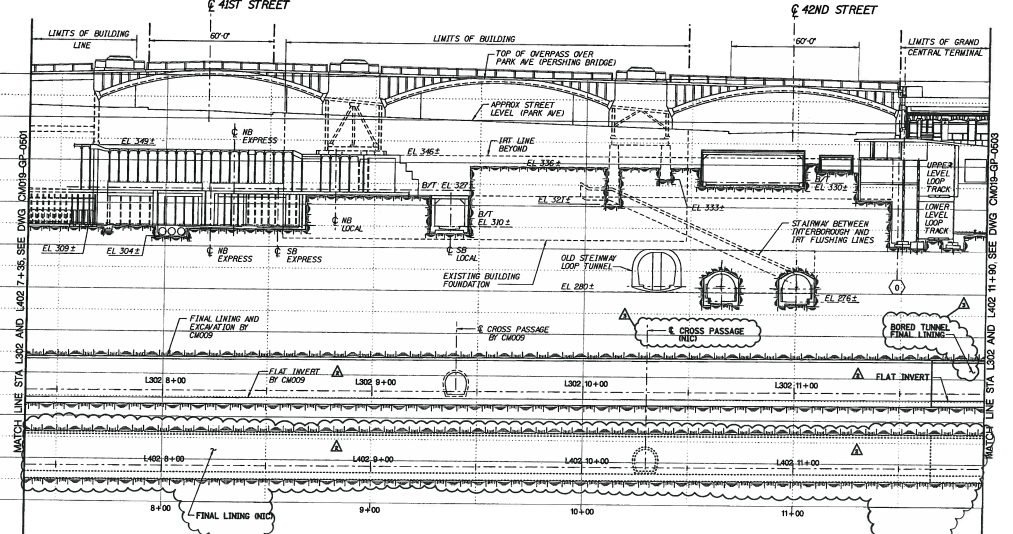

The HTP approach to Penn Station assumes that trains from the tunnel would veer south, eventually to tracks to be excavated out of Block 780 for $13 billion. However, nothing in the current design of the tunnel forces tracks to veer so far south to Penn Expansion. There is room, respecting the support columns west of 8th Avenue, to connect the HTP approach to the new platforms 1 and 2, or for that matter to present-day tracks 1-5.

It is also assumed that Penn Station Access (PSA) is completed; the project’s current timeline is that it will open in 2026, offering Metro-North service from the New Haven Line to Penn Station. As soon as PSA opens, trains should run through to New Jersey, for the higher efficiency mentioned above.

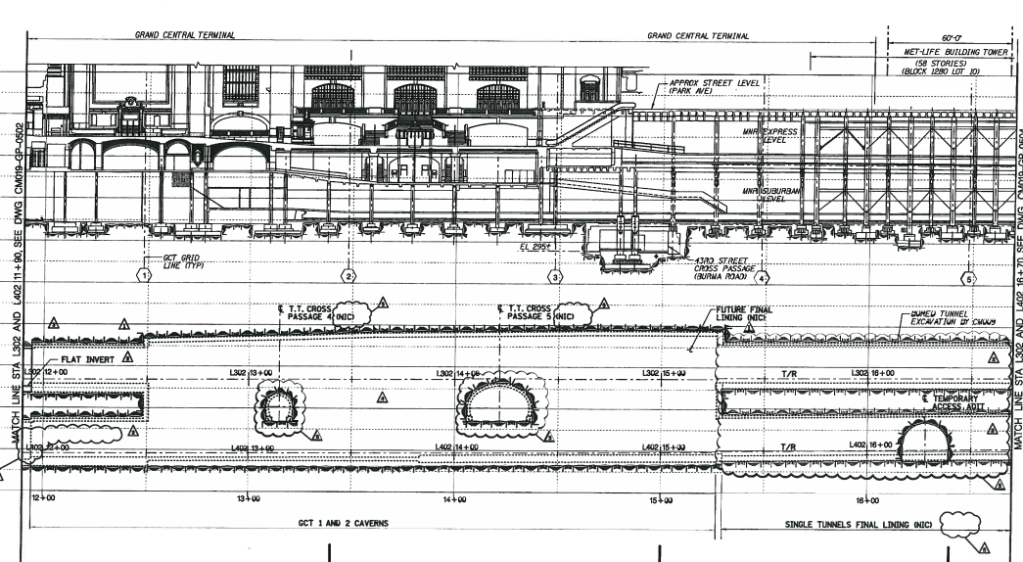

The additional pieces of major infrastructure required for this vision are a tunnel from Penn Station to Grand Central, and an Empire Connection realignment.

The Penn Station-Grand Central connection (from platforms 1 and 2) has been discussed for at least 20 years, but not acted upon, since it would force coordination between New Jersey Transit and Metro-North. Such a connection would offer riders at both systems the choice between either Manhattan station—and the choice would be on the same train, whereas on the LIRR, the same choice offered by East Side Access cuts the frequency to each terminal in half, which has angered Long Island commuters.

Overall, it would be a tunnel of about 2 km without stations. It would require some mining under the corner of Penn 11, the building east of 7th Avenue between 31st and 32nd Street, but only to the same extent that was already done in the 1900s to build the ERT under 32nd Street. Subsequently, the tunnel would nimbly weave between older tunnels, using an aggressive 4% grade with modern electric trainsets (the subway even climbs 5.4% out of a station at Manhattan Bridge, whereas this would descend 4% from a station). The cost should be on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions—the billions of dollars in per-km cost in New York today are driven by station construction rather than tunnels, and by poor project delivery methods that can be changed to better ones.

The Empire Connection realignment is a shorter tunnel, but in a more constrained environment. Today, Amtrak trains connect between Penn Station and Upstate New York via the existing connection, going in tunnel under Riverside Park until it joins the tracks of the current Hudson Line in Spuyten Duyvil. Plans for electrifying the connection and using it for commuter rail exist but are not yet funded; these should be reactivated, since otherwise there’s nowhere for trains from the 33rd Street ERT to run through to the west.

It is necessary to realign the last few hundred meters of the Empire Connection. The current alignment is single-track and connects to more southerly parts of the station, rather than to the optimal location at the northern end. This is a short tunnel (perhaps 500 meters) without stations, but the need to go under an active railyard complicates construction. That said, this too should cost on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions.

Finally, platforms 3-6 all feed the same approach tracks on both sides, but in principle they could be separated into two. There are occasional long-term high-cost plans to fully separate out intercity rail tracks from commuter tracks even in New York, with dedicated tunnels all the way. The model does not assume that such plans are actualized, but if they are, then there is room to connect the new high-speed rail approach tunnel to platforms 4 and 5 at both ends.

Overall, the model gives the station just 20 turnouts, down from hundreds today. This is a more radical version of the redesign of Utrecht Station in the 2010s, which removed pass-through tracks, simplified the design, and reduced the number of turnouts from 200 to 70, in order to make the system more reliable; turnouts are failure-prone, and should be installed only when needed based on current or anticipated train movements.

Pedestrian circulation

The station in the model has very high pedestrian throughput. The maximum capacities are 100 passengers/minute on a wide escalator, 49 per minute per meter of staircase width, and 82 per minute per meter of walkway width. A full 12-car commuter train has about 1,800 passengers; the vertical access points—a minimum of seven up escalators, five 2.7 meter wide staircases, and three elevators per platform—can clear these in about 80 seconds. In the imperfect conditions of rush hour service or emergency evacuation, this is doable in about 90 seconds. A 16-car intercity train has fewer passengers, since all passengers are required to have a seat, and thus they can evacuate even faster in emergency conditions.

Not only is the throughput high but also the latency is low. At the current Penn Station, it can take six minutes just to get between a vertical access point and an exit, if the passenger gets off at the wrong part of the platform. In contrast, with the modeled station, the wide platforms make it easier for passengers to choose the right exit, and connect to a street corner or subway entrance within a maximum of about three minutes for able-bodied adults.

This has implications for station design more generally. At the Transit Costs Project, we have repeatedly heard from American interviewees that subway stations have to have full-length mezzanines for the purposes of fire evacuation, based on NFPA 130. In fact, NFPA 130 requires evacuation in four minutes of throughput, and in six minutes when starting from the most remote point on the platform; at a train station where trains are expected to run every 2-2.5 minutes at rush hour and unload most of their passengers in regular service, it is dead letter.

Thus, elements of the platform design can be copied and pasted into subway expansion programs with little change. A subway station could have vertical circulation at both ends of the platform as portrayed at any of the combined staircase and escalator banks, with wider staircases if there’s no need for passengers to walk around them. No mezzanine is required, nor complex passageways: any train up to the size of the largest New York City Subway trains could satisfy the four-minute rule with a 10-meter island platform (albeit barely for 10-car lettered lines).

Technical limitations and architecture

The model is designed around interactivity and playability. This has forced us to make some artistic compromises, compared with what one sees in 3D architectural renderings that are not interactive. To run on an average home machine, the design has had to reduce its polygon count and limit the detail of renderings that are far from the camera position.

For the same reason, the level shows the exterior of Moynihan Station as an anchor, but not the other buildings across from the station at 31st Street, 33rd Street, or 7th Avenue.

In reality, both East and West Walkways would be more architecturally notable than as they are depicted in the level. Our depiction was inspired by walkways above convention centers and airport terminals, but in reality, if this vision is built, then the walkways should be able to support themselves without relying too much on the tracks. Designs with massive columns flanking each elevator are possible, but so are designs with arches, through-arches, or tied arches, the latter two options avoiding all structural dependence on the track level.

Some more architectural elements could be included in an actual design based on this model, which could not be easily modeled in an interactive environment. The platforms certainly must have shelter from the elements, which could be simple roofs over the uncovered parts of the platform, or large glass panels spanning from 31st to 33rd Street, or even a glass dome large enough to enclose the walkways.

Finally, some extra features could be added. For example, there could be more vertical circulation between 7th Avenue and East End Corridor (which is largely a subway access corridor) than just two elevators—there could be stairs and escalators as well. There is also a lot of dead space as the tracks taper from the main of the station to the access tunnels, which could be used for back office space, ticket offices, additional concessions, or even some east-west walkways functioning as 31.5th and 32.5th Streets.