Continuing my series on different traditions of building urban rapid transit, today it’s time for Germany and Austria, following the posts on the US, the Soviet bloc, Britain, and France. Germany had a small maritime empire by British and French standards and lost it all after World War 1, but has been tremendously influential on its immediate neighbors as a continental power. This is equally true of rapid transit: Germany and Austria’s rail traditions have evolved in a similar direction, influential also in Switzerland, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Belgium to varying extents.

S-Bahns and U-Bahns

Germany is one of the origins of urban regional rail, called S-Bahn here in contrast with the U-Bahn subway. The first frequent urban rail service in the world appeared in London in 1836, but trains ran every 20 minutes and the stop spacing was only borderline urban. Berlin in contrast innovated when it opened the east-west elevated Stadtbahn in 1882, running frequent steam trains with local spacing.

As elevated steam-powered urban rail, the Stadtbahn was not particularly innovative. New York had already been running such service on its own els going back to 1872. But the Stadtbahn differed in being integrated into the mainline rail system from the start. Berlin already had the Ringbahn circling the city’s then-built up area to permit freight trains to go around, but it still built the Stadtbahn with four tracks, two dedicated to local traffic and two to intercity traffic. Moreover, it was built to mainline rail standards, and was upgraded over time as these standards changed with the new national rail regulation of 1925. This more than anything was the origin of the concept of regional rail or S-Bahn today.

Vienna built such a system as well, inspired by many sources, including Berlin, opening in 1898. Hamburg further built a mainline urban rail connection between Hauptbahnhof and Altona, electrifying it in 1907 to become the first electrified S-Bahn in the world. Copenhagen, today not particularly German in its transportation system, built an S-Bahn in the 1930s, naming it S-tog after the German term.

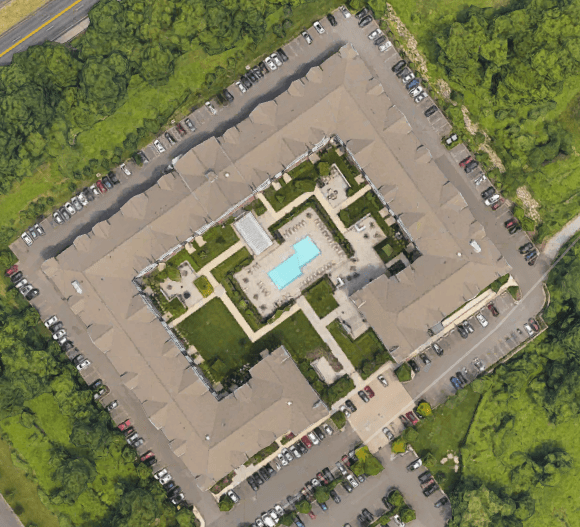

However, German cities that built such S-Bahn systems would also build separate U-Bahn systems. U-Bahns in Germany have short stop spacing and tend to mostly serve inner areas: for example, on this map of Munich, the U-Bahn is in blue, and the trams are in red. Berlin has some farther-reaching U-Bahn lines, especially U7, a Cold War line built when the West got the U-Bahn and the East got the S-Bahn; had the city not been divided, it’s unlikely it would have been built at all.

Some of the early U-Bahns were even elevated, similarly to New York subway lines and a few Paris Métro lines. Hamburg’s operator is even called Hochbahn in recognition of the elevated characteristic of much of its system. Like Paris and unlike New York, those elevated segments are on concrete viaducts and not steel structures, and therefore the trains above are not very noisy, generally quieter than the cars at street level.

Light rail and Stadtbahns

The early els of Berlin and Vienna were called Stadtbahn when built in the 19th century, but since the 1960s, the term has been used to refer to mixed subway-surface systems.

Germany had long been a world leader in streetcar systems – the first electric streetcar in the world opened in Berlin in 1881. But after World War Two, streetcars began to be viewed as old-fashioned and just getting in the way of cars. West German cities generally tore out their streetcars in their centers, but unlike American or French cities, they replaced those streetcars with Stadtbahn tunnels and retained the historic streetcar alignments in outer neighborhoods feeding those tunnels.

The closure of the streetcars was not universal. Munich and Vienna retained the majority of their tram route-length, though they did close lines parallel to the fully grade-separated U-Bahn systems both cities built postwar. Many smaller cities retained their trams, like Augsburg and Salzburg, though this was generally more consistent in the Eastern Bloc, which built very little rapid transit (East Berlin) or severed itself from the German planning tradition and Sovietized (Prague, Budapest).

The Stadtbahn concept is also extensively used in Belgium, where it is called pre-metro; the Vienna U-Bahn and even the generally un-German Stockholm T-bana both have pre-metro history, only later transitioning to full grade separation. Mixed rapid transit-streetcar operations also exist in the Netherlands, but not in the consistent fashion of either the fast-in-the-center-slow-outside Stadtbahn or its fast-outside-slow-in-the-center inverse, the Karlsruhe model of the tram-train.

Network design

Rail network design in German-speaking cities is highly coordinated between modes but is not very systematic or coherent.

The coordination means that different lines work together, even across modes. In the post about France, I noted that the Paris Métro benefited from coordinated planning from the start, so that on the current network, there is only one place where two lines cross without a transfer. This is true, but there are unfortunately many places where a Métro line and an RER line cross without a transfer; the central RER B+D tunnel alone crosses three east-west Métro lines without a transfer. In Berlin, in contrast, there are no missed connections on the U-Bahn and the S-Bahn, and only one between the U-Bahn and S-Bahn, which S21 plans do aim to fix. Hamburg has two missed connections on the U-Bahn and one between the U- and S-Bahn. Munich has no missed connections at all.

But while the lines work well as a graph, they are not very coherent in the sense of having a clear design paradigm. Berlin is the most obvious example of this, having an U-Bahn that is neither radial like London or Moscow nor a grid like Paris. This is not even a Cold War artifact: U6 and U8 are parallel north-south lines, and have been since they opened in the 1920s and early 20s. Hamburg and Vienna are haphazard too. Munich is more coherent – its U-Bahn has three trunk lines meeting in a Soviet triangle – but its branching structure is weird, with two rush hour-only reverse-branches running as U7 and U8. The larger Stadtbahn networks, especially Cologne, are a hodgepodge of mergers and splits.

Fares

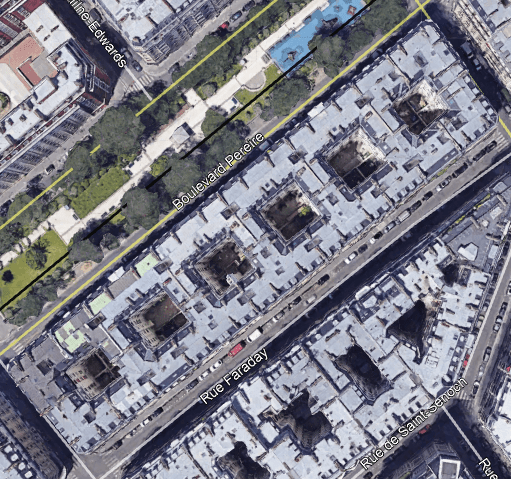

The German planning tradition has distinguishing characteristics that are rare in other traditions, particularly when it comes to fare payment – in many other respects, the Berlin U-Bahn looks similar to the Paris Métro, especially if one ignores regional rail.

Proof of payment: stations have no fare barriers, and the fare is enforced entirely with proof of payment inspections. This is common globally on light rail (itself partly a German import in North America) and on European commuter rail networks, but in Germany this system is used even on U-Bahns and on very busy S-Bahn trunks like Munich and Berlin’s; in Paris there’s POP on the RER but only in the suburbs, not in the city.

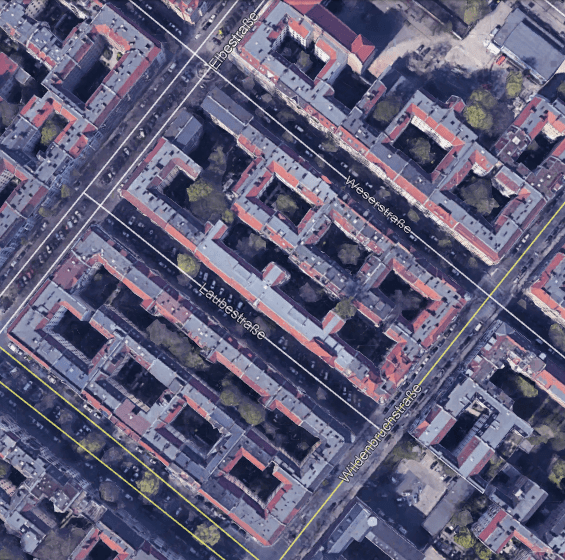

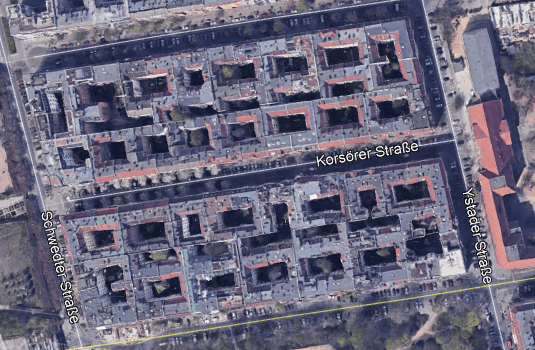

Unstaffed stations: because there are no fare barriers, stations do not require station agents, which reduces operating expenses. In Berlin, most U-Bahn stations have a consistent layout: an island platform with a stairway exit at each end. This is also common in the rest of the German-speaking world. Because there is no need for fare barriers, it is easy to make the stations barrier-free – only one elevator is needed per station, and thus Berlin is approaching fully wheelchair accessibility at low cost, even though it’s contemporary with New York (only 25% accessible) and Paris (only 3% accessible, the lowest among major world metros).

Fare integration: fares are mode-neutral, so riding an express regional train within the city costs the same as the U-Bahn or the bus, and transfers are free. This is such an important component of good transit that it’s spreading across Europe, but Germany is the origin, and this is really part of the coordination of planning between U- and S-Bahn service.

Zonal fares: fares are in zones, rather than depending more granularly on distance as is common in Asia. Zones can be concentric and highly non-granular as in Berlin, concentric and granular as in Munich, or non-concentric as in Zurich.

Monthly and annual discounts: there is a large discount for unlimited monthly tickets, in order to encourage people to prepay and not forget the fare when they ride the train. There are even annual tickets, with further discounts.

No smartcards: the German-speaking world has resisted the nearly global trend of smartcards. Passengers can use paper tickets, or pay by app. This feature, unlike many others, has not really been exported – proof-of-payment is common enough in much of Northern and Central Europe, but there is a smartcard and the fare inspectors have handheld card readers.

Verkehrsverbund: the Verkehrsverbund is an association of transport operators within a region, coordinating fares first of all, and often also timetables. This way, S-Bahn services operated by DB or a concessionaire and U-Bahn and bus services operated by a municipal corporation can share revenue. The first Verkehrsverbund was Hamburg’s, set up in 1965, and now nearly all of Germany is covered by Verkehrsverbünde. This concept has spread as a matter of fare integration and coordinated planning, and now Paris and Lyon have such bodies as well, as does Stockholm.

Germany has no head

The American, Soviet, British, and French traditions all rely on exports of ideas from one head megacity: New York, Moscow, London, Paris. This is not at all true of the German tradition. Berlin was the richest German city up until World War 2, and did influence planning elsewhere, inspiring the Vienna Stadtbahn and the re-electrification of the Hamburg S-Bahn with third rail in the late 1930s. But it was never dominant; Hamburg electrified its S-Bahn 20 years earlier, and the Rhine-Ruhr region was planning express regional service connecting its main cities as early as the 1920s.

Instead, German transportation knowledge has evolved in a more polycentric fashion. Hamburg invented the Verkehrsverbund. Munich invented the postwar S-Bahn, with innovations like scheduling a clockface timetable (“Takt”) around single-track branches. Cologne and Frankfurt opened the first German Stadtbahn tunnels (Boston had done so generations earlier, but this fell out of the American planning paradigm). Karlsruhe is so identified with the tram-train that this technology is called the Karlsruhe model. Nuremberg atypically built a fully segregated U-Bahn, and even more atypically was a pioneer of driverless operations, even beating Paris to be the first city in the world to automate a previously-manual subway, doing so in 2010 vs. 2012 for Paris.

There’s even significant learning from the periphery, or at least from the periphery that Germany deigns acknowledge, that is its immediate neighbors, but not anything non-European. Plans for the Deutschlandtakt are based on the success of intercity rail takt planning in Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands, and aim to build the same system at grander scale in a larger country.

The same polycentric, headless geography is also apparent in intercity rail. It’s not just Germany and Switzerland that build an everywhere-to-everywhere intercity rail system, in lieu of the French focus on connecting the capital with specific secondary cities. It’s Austria too, even though Vienna is a dominant capital. For that matter, the metropolitan area of Zurich too is around a fifth of the population of Switzerland, and yet the Swiss integrated timed transfer concept is polycentric.

Does this work?

On the most ridiculously wide definition of its metropolitan area, Vienna has 3.7 million people, consisting of the city proper and of Lower Austria. In 2012, it had 922 million rail trips (source, PDF-p. 44); the weighted average work trip modal split in these two states is 40% (source, PDF-p. 39). In reality, Vienna is smaller and its modal split is higher. Zurich, an even smaller and richer city, has a 30% modal split. Mode shares in Germany are somewhat lower – nationwide Austria’s is 20%, Germany’s is 16% – but still healthy for how small German cities are. Hamburg and Stuttgart both have metropolitan public transport modal splits of 26%, and neither is a very large city – their metro areas are about 3.1 and 2.6 million, respectively. Munich is within that range as well.

In fact, in the developed world, one doesn’t really find larger modal splits than these in the 2 million size class. Stockholm is very high as well, as are 1.5th-world Prague and Budapest, but one sees certain German influences in all three, even though for the most part Stockholm is its own thing and the other two are Soviet. Significantly higher rates of public transport usage exist in very large Asian cities and in Paris, and Germany does deserve demerits for its NIMBYism, but NIMBYism is not why Munich is a smaller city than Taipei.

To the extent there’s any criticism of the German rapid transit planning tradition, it’s that construction costs lately have been high by Continental European standards, stymieing plans for needed expansion. Märkisches Viertel has been waiting for an extension of U8 for 50 years and it might finally get it this decade.

The activist sphere in Germany is especially remarkable for not caring very much about U-Bahn expansion. One occasionally finds dedicated transport activists, like Zukunft Mobilität, but the main of green urbanist activism here is bike lanes and trams. People perceive U- and S-Bahn expansion as a center-right pro-car plot to remove public transit from the streets in order to make more room for cars.

The high construction costs in Germany and the slow, NIMBY-infused process are both big drags on Germany’s ability to provide better public transportation in the future. It’s plausible that YIMBYer countries will overtake it – that Korean and Taiwanese cities of the same size as Munich and Hamburg will have higher modal splits than Munich and Hamburg thanks to better transit-oriented development. But in the present, the systems in Munich and Zurich are more or less at the technological frontier of urban public transportation for cities of their size class, and not for nothing, much of Europe is slowly Germanizing its public transport planning paradigm.