Don’t Romanticize Traditional Cities that Never Existed

(I’m aware that I’ve been posting more slowly than usual; you’ll be rewarded with train stations soon.)

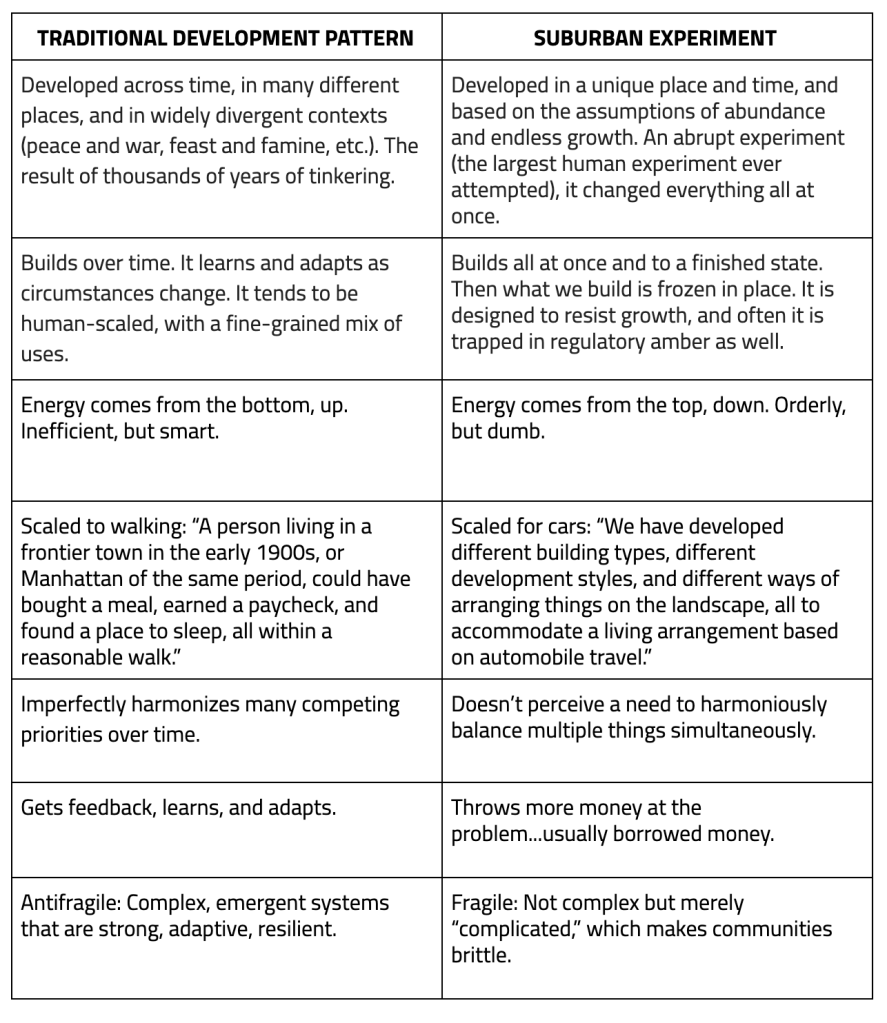

I saw a tweet by Strong Towns that compared traditional cities with the suburbs, and the wrongness of everything there reminded me of how much urbanists lie to themselves about what cities were like before cars. Strong Towns is more on the traditional urbanism side (to the point of rejecting urban rail on the grounds that it leads to non-gradual development), but a lot of what I’m critiquing here is, regrettably, commonly believed across the urbanist spectrum.

The basic problem with this comparison is that there was never such a thing as traditional urbanism. There are others; all of the claims in the comparison are false – for example, the line about “makes communities brittle” misses how little community empowerment cities had in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before zoning, and the line about top-down versus bottom-up energy misses how centralized coal and hydroelectric plants were at the turn of the century whereas left-voting NIMBY suburbs today are the most reliable place to find decentralized rooftop solar plants. But the fundamental problem is that Strong Town, and most urbanists, assume that there was a relatively fixed urban model around walkability, which cars came in and wrecked in the 20th century.

What’s true is that before mass motorization, people didn’t use cars to get around. But beyond that tautology, every principle of urban walkability was being violated in one pre-automobile urban typology or another.

Local commuting

Pre-automobile industrial cities were not 15-minute cities by any means. Marchetti’s constant of commuting goes back to at least the early 19th century; people in pre-automobile New York or London or Berlin commuted to a commercializing city center. This was to some extent understood in the second half of the 19th century: the purpose of rapid transit in New York, first steam els and then the subway, was to provide a fast enough commute so that the working class of the Lower East Side would get out of its tenements and into lower-density houses where they’d be turned from hyphenated Jews and Italians into proper Americans.

There has been a real change in that, in Gilded Age New York (and, I believe, in third-world cities today like Nairobi), people worked either locally or in city center. There was very little crosstown commuting, and so the Commissioners’ Plan for Manhattan in 1811 emphasized north-south commuting to Lower Manhattan, while private streetcar concessionaires likewise built routes to city center and rarely crosstown. Nor was there much long-distance travel except by the people who did work in city center: there were people who lived their entire lives in Brooklyn without visiting Manhattan, which became unthinkable by the early 20th century already. But this hardly makes Gilded Age Brooklyn a 15-minute city, any more than a modern suburb where most people do not visit city center out of fears of crime is anything but a suburb of the city, living off of the income generated by people who do commute in.

In truly premodern city, the situation depended on the time and place. Medieval European cities famously had little commuting – shopkeepers would live in the same building that housed their store, sleeping on an upper floor. But in Tang-era Chang’an, people did commute (my reference is the History of Imperial China series, no link, sorry). This is very far from the result of thousands of years of tinkering, when each time and place did something different before industrialization, and then went to yet another set of layouts after.

Local infrastructure

Pre-automobile industrial cities mixed top-down and bottom-up approaches, same as today. The grid plans favored in the United States, China, and the Roman Empire were more top-down than the unplanned street networks of most medieval and Early Modern European cities, each designed for a different cultural context. (In Imperial Rome much of the context was about following military manuals, for those cities that descend from forts.) In the medieval Muslim world, cities had cul-de-sacs long before cars, because this way each clan could have its own walled garden, so to speak.

Widely divergent contexts

Premodern cities developed in widely divergent contexts. Based on these contexts, they could look radically different. The comparison mentions war and peace; well, defensive walls were a fixture in many cities, and these mattered for their urban development. They were not nice strolls the way some embankments are today. There aren’t any good examples of walls in North America, but there are star forts, and they’re not usually pleasant walks – their purpose was to make the day of besieging troops as bad as possible, not to make tourists feel good about the city’s history. Medieval walls were completely different from star forts, and didn’t make for a walkable environment, either – in Paris I would routinely walk to the park and to the exterior of the Château de Vincennes, and while the park was pleasant, the castle has a moat and none of the street uses that activate a street, like retail or windows. The modern equivalents of such fixtures should be compared with prisons and modern military bases (some using the historic star forts), not touristy palaces.

Even the concept of city center is, as mentioned above on commuting, neither timeless (it didn’t exist in premodern Europe) nor a product of cars (it did exist in 19th-century America and Europe). Joel Garreau points out, either in Edge City or in some of the articles he’s written about the concept, that the traditional downtown was really only a fixture for a few generations, from the early 19th century to the middle of the 20th.

The issue of fragility

The entire comparison is grating, but smoehow the thing that bothers me most there is not the elementary errors, but the last point, about how traditional cities were antifragile for millennia before modern suburbia came in and wrecked them with debt.

This, to be very clear, is bullshit. Premodern cities could depopulate with one plague, famine, or war; these often co-occurred, such as when Louis XIV’s wars led to such food shortages that 10% of France’s population died in two famines spaced 15 years apart (put another way: France underwent a Reign of Terror’s worth of deaths every two weeks for a year and a half, and then a second for somewhat less than a year). In 1793, 10% of Philadelphia’s population died of yellow fever within the span of a few months. After repeated sacks and economic decline, Jaffa was abandoned in much of the Early Modern era.

Industrial cities generally do not undergo any of these things. (They can be subjected to genocide, like the Jews of Europe in the Holocaust, but that’s not at all about urbanism.) But that’s hardly a millennia-old tradition when it only goes back to about the middle of the 19th century, after the Great Hunger. In the UK, the Great Hunger affected rural areas like Ireland and Highland Scotland, but in a country that was at the time majority-rural – Britain would only flip to an urban majority in 1851 – it’s hardly a defense. Nor did the era after 1850 feature much stability in the cities; boom-and-bust cycles were common and the risk of unemployment and poverty was constant.

I’m not fully awake which might explain why I can’t seem to get some of your arguments. Am I being too literalist or are you? Like:

You must be using some alt concept of what “centre” means because all the biggest medieval cities had what I call a city centre.

Again, it must be some fine point of interpretation. I mean Euro cities suffered a population decline with the plague but they all survived and growth eventually picked up–in exactly the same cities which remained prime (as centres of rule & commerce etc). I’d call that “anti fragile”. A bit like Covid dealt a blow to many city centres but they recovered/are recovering.

Well, maybe 30 minutes or whatever but they had to be, and were, very limited by means of transport for workers etc. The vast majority of people clearly lived close enough to where they worked etc. The only real exceptions were farmers who spent half the day travelling into some central trading point on market day one day of the week etc. Equally clearly it was the invention of motorised* transport in the early 19th century that changed everything. (*I’d include horse-drawn trams on steel rails.)

That does strike me as true and I can’t get my head around your every principle of urban walkability was being violated in one pre-automobile urban typology or another. How? Putting minor exceptions aside I can’t see how your statement stands up. In cities with large rivers, like Manhattan/Brooklyn but even my current city of Brisbane/Sth Brisbane, either side of the water operated as separate cities with duplication of all functions because boat travel between them was simply too slow & inefficient; this changed once bridges could connect them (only in late 19th century) and, now within that 15-minutes or whatever, essentially one of the two sides became the dominant city centre. In London or Paris where bridges could traverse their rivers from early days this didn’t happen and to this day there is the clear original city centre on one side only (Northbank not Southbank, Right bank (+Ile de la Cité), not Left bank). Using these as examples of both true city centres and the 15-minute (whatever) rule.

I’ll have to come back later and re-read all this.

When you say that growth eventually picked up, the “eventually” is doing a lot of work. Rome depopulated by 95% during the fall of the Western Empire, it took until the 20th century until its population reached one million again. Bruges also suffered from large depopulation when it lost its direct access to the sea and would only regain its late medieval peak population in the industrial era.

And then there are the ancient cities that don’t even exist anymore like Babylon or Cahokia.

By about 1330 Paris reached about 250,000, the largest city in Europe, and after the waves of plague in 1348, 1360 and 1375 up to 50,000 Parisians died. Population had recovered by the late 1500s so yes its affects spanned two and half centuries, however historians also attribute some of this sluggishness to the attrition of the Hundred Years war and periods of low harvests.

Due to this and general health affects of crowded city conditions, some improvements were begun such as paved roads with central channels to act as open sewers (a lot better than without) and Henri IV built Hopital St Louis (as it happens where my institute was located) in 1607-1611 with a plague wing, and located outside the city walls at that time.

Source: Paris, the shaping of the French capital by Paul N. Baldachin, 2021.

And here is a graph:

Okay, so for the most part, cities weren’t wholly abandoned (there’s always stuff like Dunwich but it’s rare). But then neither has any modern auto-oriented city. They sometimes lose population due to economic decline, but that’s not new – Paris had some historical bouts of depopulation due to wars and epidemics, some larger than the decline in intra muros population in the 20th century.

Re violations of principles of walkability: castles and city walls were not at all walkable by modern standards. They didn’t have an active street wall or anything like that – they presented a blank wall to the street because their purpose was military defense, not pleasant urbanism. Then there’s the cul-de-sac development of some MENA cities (but not European ones).

In London, there was commuting by carriage already in the early 19th century – the popular book I read about this, The Victorian City, is really good and describes it early, including how hectic it all was (overcrowded carriages, etc.).

To be fair all of the rotten boroughs that were abolished in the 1832 reform act were larger places that had seen population decline.

The only real exceptions were farmers who spent half the day travelling into some central trading point on market day one day of the week etc.

The exception were the people living in towns. Most people were farmers or some sort of resource extractor living out in the rural areas. Families living on individual farms is an exception too.

Stay on topic. The discussion is about cities. Of the 250,000 medieval Parisians essentially none were farmers. Perhaps the Benedictines, Augustinians and Franciscans grew their own food inside their monasteries but then they didn’t haul it to market (and actually they owned most of Left Bank all along the Seine but they lost most of that when the medieval city spread there in the 12-13th century).

OTOH the Paris basin was apparently the richest agricultural land in Europe and that is the reason for the city. Also, the faubourgs (“suburbs”) immediately outside the walls would have had market gardens; about one in ten or twenty of non-city residents would have transported produce to central markets in the city. Incidentally Alon is wrong about the walls because they served both defensive and tax points for goods entering the city, like the Fermiers Gènèraux Wall (Farmers General) (1785). Indeed that was the sole purpose of the last wall built, the Thiers Wall of 1844.

Of course from an urbanist point of view the walls served their most important function as growth boundaries forcing very high city densities.

Yeah, I was debating whether to mention tax walls around Paris and Berlin, compared with their absence in London, and what this meant for urban density. Thanks for bringing it up.

Speaking of Paris and walls: to again reinforce my points that walls don’t make for a walkable environment, the boundary of the buildable area of the city was not the modern Périphérique, which was the outer wall, but the Boulevards of the Marshals; between them was military usage, and when the wall was torn down, that area was somewhat of a no man’s land (“the zone”) before it was redeveloped as high-density HLMs and other such land use.

@Alon

Sorry, I don’t get that. I am not sure there is any real argument about it: the various walls of Paris (beginning 12th century) acted as growth boundaries and consequently directly caused Paris’ high density. Paul Balchin claims this made Paris unique among major cities of the world. Almost certainly it is why it is the densest city in Europe (and he gives it as 2.4x the density of “west London”–which itself is a bit of a fudge since I believe London is even lower density if you used a Paris-size circle on the centre of London). Both its constrained size and high population and density of features, make it the most walkable (‘complete’) city in the world.

I am trying to find some other meaning in what you wrote but fail. It seems to me the walls have been critical in its creation and is what modern day city growth boundaries (virtual walls) are attempting to do.

Yes, I think I have described it in some detail on this blog. The Thiers wall zone was ≈400m wide, kept clear for various reasons. The Petite Ceinture railway, with spurs to all the mainline railway stations/lines, was built to supply material for its construction; as I have argued on this blog, being built below grade so as to not disrupt surface streets, it was a proto-Metro (and in the repurposed section St Lazare to Auteil passenger line in 1954 was arguably the world’s first actual Metro!). The wall is yet another arguably entirely fortuitous event in creation of modern Paris. The first piece of luck is that it is amazing it was built at all–as late as 1844–and was barely finished before it became totally redundant. The second amazing piece of ‘luck’ was that the huge space (v. approx. 16km2) remained undeveloped for close to a century which meant it ended up being used optimally; it seems a curious black hole in most histories of Paris but I have to assume it lying fallow for so long is at least partly due to lack of political consensus on its reuse (and of course wars & budgets). Obviously the Peripherique (which was even later in the 60s) which, contrary to its many critics, I claim is crucial in keeping traffic ‘manageable’ in central Paris (and arguably everywhere else in Ile de France, as it feeds/redistributes to all the arterial freeways). London would kill to have something so central compared to its M25 which is >25km from the centre. A lot of that 400m deep ribbon was used for green space including sports fields (I count 34 stades/fields), the Cité Universitaire residential campus, hospitals, the huge Pte de Versailles exposition site, and HLM public housing (again, luckily mostly built inter-war so it is Haussmannian and not hi-rise horror towers-in-park style).

Incidentally I would claim that the water boundaries of Manhattan performed the same function as Paris’ physical walls, and no accident that this is the densest urban environment in the US. Significant parts of it are also very walkable but it is rather ruined by being very long and narrow. I have walked from the Columbia medical centre (just south of GW bridge) all the way to Battery Park but it is too long. San Francisco is similar in having water on three sides and mountains on the fourth side, resulting in the second highest urban density in the US, and very walkable.

I am sure there are other similar examples, most notably Hong Kong island. Ha, Kowloon Walled City at some impossible density. Malé, the capital of the Maldives and a ridiculous barely credible example with 150,000 on a small island. Oh, and my old island home of Ile St Louis which has a density of 100,000/km2 and you’d be nuts to drive there (except on Pont Sully linking Leftbank to Rightbank so not really the island).

“the various walls of Paris (beginning 12th century) acted as growth boundaries and consequently directly caused Paris’ high density”

Hard to argue that Paris’ walls led to its high density when:

1) Virtually every city in Europe had walls at the time of the 12th century and the rest of the middle ages

2) Paris had no walls for a century from ~1680-1780

3) The Farmer’s General Wall of the 1780’s were not a growth boundary, in some cases they promoted growth outside of the wall to avoid taxes – Bercy for instance was originally an independent town and became a major wine market because it was outside the Farmer’s General and didn’t have to pay taxes.

4) The Thiers wall encompassed so much area that it placed no major limit on Paris’ growth, and after Paris’ annexed all space inside the wall it’s population density never reached that of the old city inside of the Farmer’s General again.

5) The Thiers wall was also not a formal growth boundary, and while it did have the Zone outside it with no structures to allow fields of fire, many suburbs grew just outside it like St. Denis.

@Onux

Oops, I inadvertently inverted the Fermiers and Thiers walls. I actually knew that.

I didn’t mean that they were ‘formal’ growth boundaries but that that is what became their de facto function, essentially unplanned. And assuredly they did. It’s why other cities continued to sprawl outwards and be under the same city jurisdiction while Paris remained Paris (intramuros). As you say yourself, while many cities had walls at various earlier times only Paris retained such a wall into the late 19th century. The distinction between intra- and extra-muros remains discussed today with some arguing there would be benefits (exactly what I am not clear about) by demolishing the Peripherique etc. I don’t think much of this is in contention, perhaps just varied explanations of cause-effect.

The fact that population fell in the 20th century has nothing to do with anything except a reduction in the awful living conditions of many, concomitant with increasing cost of intramuros housing and a middle-class that wanted more space that they could get more easily extramuros. In fact it made intramuros even more desirable. And it has maintained its high population whereas most other cities lost a lot more population out of their centres.

The Bercy wine zone was outside because there was not the (industrial) space inside, and all but a tiny amount of wines came from all over France and so it had to be on the rail tracks; of course the biggest richest consumers were intramuros and that wine was taxed as it entered from the Bercy warehouses. The tax thing became moot as the whole world went to national taxes, usually provoked by the world wars.

@Onux

What reason would you give for Paris’ unusually high density? The Thiers wall, and maybe Paris’ unusually narrow city boundaries, seem to be the only things that distinguish Paris from other European cities, and Paris is unique among European cities in having maintained the wall all the way to the 1920s.

Regarding point 4, by 1900 or so, the area inside the Thiers wall was pretty much filled up and it was definitely playing a role in structuring Paris’ growth. The main counterpoint I can think of to the Thiers wall->high density hypothesis is that some neighboring communes like Levallois, Vincennes, or Saint Mandé achieve Paris or near-Paris level density, but even then I could still see that as being artifacts of the way the Thiers wall has structured the Paris agglomeration.

I’ve thought of a counter-example for the wall hypothesis: London’s Greenbelt could be compared to Paris’ Thiers Wall (but with many exceptions, see below). Although one can find discussion of it being a mechanism against endless urban sprawl of London, it was mostly justified on the basis of providing green space as refuge from the city: proposed by the Greater London Regional Planning Committee in 1935, “to provide a reserve supply of public open spaces and of recreational areas and to establish a green belt or girdle of open space”. I am not sure it has worked in those terms but anyway, what it hasn’t done is caused any serious densification of London, which is the least-dense Euro city. The last 15 years orgy of building hi-rise luxury apartments along the river doesn’t matter because 1. they don’t actually house many people and 2. they house almost no real Londoners due to unaffordability. Indeed they are displacing ordinary Londoners who used to live in those zones.

Perhaps the main difference to Paris’ wall makes it ineffective. It is far more distant, being already at the outer limits of modern London when it was finally designated in the late 50s (1958?). I think that that is more than enough to make it ineffective. But the more relevant reason is my old fave of the Brits’ (and Anglosphere in general) total resistance to Euro (Haussmannian) style dense housing. Demographers say that London will need another one million homes to house the predicted 2+m residents in the next few decades; in passing one wonders if this will hold post-Brexit? This has provoked suggestion of building on the Greenbelt, rather than serious densification of existing urban zones! It is true that the belt is huge, at 5,100km2, but the problem is that the Brits would indeed sprawl all over it with their low-density terrace (row) or semi-detached houses. There is an estimated 200km2 of the belt which is within 800m of a railway station and deemed suitable for housing. That’s twice the size of intramuros Paris and shows the density disparity. If they would embrace Haussmannian typology they wouldn’t need to encroach on the Greenbelt at all, as those million houses could fit into ≈40km2 which is ≈ half a percent of London’s existing urbanised area. The big point is that while some may think a home in the Greenbelt would be nice, by very definition it would be at the furthest distance from everything else in London. Oh, and the real killer, as many have pointed out, these desirable Greenbelt homes would be very expensive. At least they are not talking about building more Grenfell’s or equivalent hi-rise public housing (mostly because they simply aren’t building much social housing at all).

This problem afflicts many cities, especially in the Anglosphere. As it happens one of Australia’s most prominent urbanists (and architect, and former Sydney city councilman) Elizabeth Farrelly had an article on exactly this topic a few days ago. She explicitly proposed that we have to use Paris as a model: (She makes an error in saying that Paris apartments are 8 floors which might actually put off some.)

So, after all that, I don’t think this example of London’s Greenbelt has much useful to say about it acting as a growth boundary at least from the densification point of view. Perhaps if they had created it a century earlier (when in fact it was first discussed) and magically much closer to the centre, and had a cultural change of heart on housing typology …

@minhn1994

I don’t know the reason for Paris’ density. I know that Athens proper is almost as dense, even though it lost the remnants of its last walls in the 1820s/30s, before the Theirs wall was built around Paris. I know that Barcelona proper is not far behind (and supposedly has the densist sq km in Europe) even though it tore down its walls and expanded into the L’Eixample around the same time. I can see the argument for “walls=density” in pre 1854 Barcelona when the Spanish government forcibly prevented construction outside them as a way to punish the Catalonians, but none of Paris’ walls had that character. You point that communities outside the walls have similar density to Paris intramuros twice contradicts the notion that Paris is dense because of walls: first because it shows that not all development was inside the walls and second because if development inside and outside the walls are of similar density then the wall is not the factor; causation requires correlation.

@Onux

OK, it’s good that you keep me on my toes.

I made a relatively minor arithmetic error: the 1 million houses would require about the same space as the 89km2 of Paris that houses 2.2m people. Actually 80.9km2. (The large bois are not included in urban area calcs.) I see that I mixed houses versus people. Note, it doesn’t touch the argument about the fraction of either the Greenbelt or of existing urbanised London that it consumes to fill the predicted housing need, ie. it requires the square root of stuff all space.

But the arguments about Barcelona don’t jibe. First, the Paris wall persisted essentially to today–in the form of the Peripherique which urbanists and Parisians and Franciliens refer to as a massive barrier between intra- and extra-muros (and why some want to tear it down). Second, the Eixample was modelled on Haussmannian Paris with wide avenues and Euroblock apartments of similar height. But again, Paris was ‘lucky’ in that Haussmann was modifying an existing city and, even if he had the same inclination as Cerda he couldn’t wipe away everything that was there. This explains why the Eixample has such a high density (36,000/km2 vs Paris av. of ≈25,000/km2) and it gave rise to the Eixample’s well known problems: too dense with not enough open space or space for people/pedestrians and too much traffic. Incidentally it covers 7.8km2 and roughly compares to Paris-11 which is 3.7 km2 for 41,600/km2.

Anyway, the point is that while walls did not play a direct role in the high density of the Eixample, in fact it was modelled on the city that (I theorise) was totally influenced by its walls/growth boundary, even if Napoleon III and Haussmann may not have conceptualised it in those terms. Further, the Eixample was in fact enclosed by old Barcelona: the old city to the south and the old towns of Gracia, Sants & Sant Andreu to north, west & east. Same effect as a wall or the water-walls of Manhattan. The city administration and Cerda wanted to squeeze the maximum residents into the remaining available central developable space.

Your calculations of density for Ile de France are not correct. You’ve done simple/simplistic arithmetic calc of density. One needs to use the urbanised area, and that is something I haven’t been able to track down. But as I have noted endlessly on Alon’s blog the zone has a huge amount of green space (just the Foret de Fontainebleau is 250km2, 2.6x Paris) plus agricultural land. No doubt it has considerably lower density than Paris etc but OTOH the various old towns that represent the cores of the urbanised areas are surprisingly high density, like Melun or Versailles etc. Anyone who has visited Ile de France via the RER, or just glanced at a map, can see how the urban areas stand out from the rest, and how it really doesn’t resemble Anglosphere suburban sprawl. A more realistic comparison would be the Petite Couronne, the ring of suburbs adjoining Paris with area of 657km2, population of 4,445,258 for density of 6,766/km2, approx. one quarter of Paris’ density. I can’t agree with your logic, for the reasons I have already given in earlier posts.

“London will need another one million homes to house the predicted 2+m residents”

“If they would embrace Haussmannian typology . . . those million houses could fit into ≈40km2 . . .”

Paris has about 2.2M in an area of 105km2, but you want London to fit the same pop into 40km2?!?!?! That’s a population density of ~55,000/km2, higher than the density of Manilla proper (with 1.8M in 43km2). The highest single km2 spot density in Paris is ~52k/km2, but you think “Haussmannian typology” leads to equal or higher density for dozens of km2?

“they wouldn’t need to encroach on the Greenbelt at all . . . which is ≈ half a percent of London’s existing urbanised area” Oh wait! You are actually proposing even higher density because all of the existing urbanized area already had people living on it!

Of course Ile-de-France has 12.3M in ~12000km2 for a density of just over 1000/km2. No department outside the Periphique exceeds 10,000/km2. Metro London has 14.8M in 8,382km, for a density of ~1,700/km. 60% of that space is the Metro Greenbelt; inside of it London is 9.8M in 1,738km, for a density of 5,600/km2. Grand Paris + Val de Oise is 8M in 2000km2, or a density of only 4,000/km2. Maybe instead of England adopting Hausmannian typology France should adopt terrace houses and achieve higher density outside of city center. Or maybe London should build within 800m (or 1200m!) of existing railway stations (like the Copenhagen Finger Plan) or just reduce the Green Belt in general so people can have a better quality of life with more affordable housing and an easier commute to work.

Since London’s urban area is 1,738km2, 40km2 would be 2% of it, not half a percent. The 200km2 in proximity to an existing rail station is 3.9% of the 5,160km2 greenbelt. 1200m around each station would be 450km2, 8.7% of the greenbelt, and would house 2.5M at London’s existing average urban density.

The thing that is different about Britain than other countries in terms of housing is that we built working class housing from the mid-19th century that was built well enough that it is still standing today 150 years later.

In many ways this is bad because this housing is only medium density – and is also super expensive to insulate and there isn’t space for off road car parking for electric cars.

However it is what it is.

I wrote:

Arggh. 1854.

Incidentally I believe the PC was built not only to help with the building of the Thiers Wall but also to facilitate rapid relocation of arms and soldiers to where they were needed during battle on the 35km boundary.

“Your calculations of density for Ile de France are not correct. You’ve done simple/simplistic arithmetic calc of density. One needs to use the urbanised area, and that is something I haven’t been able to track down. But as I have noted endlessly on Alon’s blog the zone has a huge amount of green space”

Yes Ile-de-France has a lot of green space, but I already noted above that it has a lower density (1,000/km2) than *Metro* London (1,700/km2) – and Metro London ALSO has a lot of green space because 60% of it is the greenbelt.

I also already gave the figures for urbanized area. Inside the greenbelt London is 5,600/km2, while the closest comparison in size is Grand Paris + Val d’Oise, with a density of 4,000/km2. Cut out the western half of that department because of Parc Vexin and you have urban Paris at 8.04M in 1460km2 for a density of ~5,500 which is still just behind London.

So no, my calculations are correct and my arithmetic is not simple, I have accurate compared like areas (full metro/commuting or full urban) and Paris is less dense than London at scales larger than the Peripherique.

“Second, the Eixample was modelled on Haussmannian Paris”

Since Haussmann took charge in 1853 while planning for the Eixample began in 1854 with Cerda’s plan adopted in 1859, no, the Eixample was NOT modelled on Hausmannian Paris. There are extensive primary source notes which show that Cerda developed his plans for street widths, lot coverages, and building heights himself (these notes also show that he developed his plans from formulas he made up himself with basically no empirical basis – but that’s a different story).

“the Eixample’s well known problems: too dense with not enough open space”

“it covers 7.8km2 and roughly compares to Paris-11 which is 3.7 km2 for 41,600/km2.”

Ah ha! So you agree that Paris is too dense, given that it has districts exceeding the ‘too dense’ Eixample!

“Further, the Eixample was in fact enclosed by old Barcelona: the old city to the south and the old towns of Gracia, Sants & Sant Andreu to north, west & east.”

The Eixample was “enclosed” by ***open land*** the same way other cities are enclosed by walls or islands by water!!?!!?!!? You are an idiot. I’m sorry for the direct language but this is like saying Dallas is “enclosed” by Arlington, Irvine, and Plano. The Eixample was the antithesis of bounded development; a direct counter-reaction to the prior constriction of Barcelona by Spanish domestic colonialism. Gracia, Sants, etc. were not a continuous wall of development ringing Barcelona but rural villages that the city absorbed, surrounded, and continued past as it grew. Good heavens, just Google “Eixample Plan” or something before writing things like this, you can easily find a map that shows how there was around 3 km of open space between Gracia and Sants in 1855.

@Onux

Now you’re just being disingenuous, and overtly discourteous to me and to logic.

How could anyone imagine that London, anywhere, is denser than Paris, anywhere whether intramuros, Petite-Couronne or Ile-de-France. For Greater London you’ve done exactly what I pointed out is against the convention on how one calculates density, namely any large un-developed land (and water) is excluded. It is absurd to include the Greenbelt’s ≈5,000km2 in such calculations if you want comparable, meaningful figures. Three quarters of Ile-de-France live in Petite Couronne + Paris at density of ≈8,000/km2. No one says that the urbanised area outside of this core is not considerably less dense but nothing as silly as your figure.

As to Eixample, you appear to be wilfully misinterpreting what I wrote. I did not write “The Eixample was “enclosed” by ***open land*** the same way other cities are enclosed by walls or islands by water!!?!!?!!?” You did and then insulted me for what you wrote/misinterpreted. Indeed, you’ve confirmed what I wrote and intended: the Eixample was in fact the open space enclosed between the old city of Barcelona and several outlying towns (Gracia etc). The fact is that the Eixample filled that space so that Gracia and the old town is continuous as is obvious if one walks the whole route along Passeig de Gràcia. How is it not accurate to describe that as the Eixample being bounded by those outlying towns?

As to French influence, you’ve typically over-reacted but in so doing gone in the other direction and over the cliff. Cerda wasn’t even formally part of the original competition for the enlargement of Barcelona but eventually, in 1860 Madrid overruled Barcelona and installed Cerda’s plan (over Antoni Rovira). Cerda’s first construction was forcing thru the Diagonal which is kinda reminiscent of hmm … and his plan was to create the direct equivalent of a Grande Croiseé! Of course as I have said before, Haussmann/Napoleon-III were working on much earlier plans of Paris so “Haussmannian” is just shorthand for the outcome; for example Le Vau’s influence is huge (and who imagines his works didn’t influence all of Europe? All those broad boulevards with avenues of trees and promenades … ).

Further the area didn’t develop for a long time, finally taking shape after several revisions in the 1890s (and later) which was when the Belle Époque was in full bloom. But it continued to develop into the 20th century which is why one sees the influence of Art Nouveau and Art Deco (and yes, some very Catalonian derivations of it).

Here’s a brief extract from Peter Rowe’s Building. Barcelona, A Second Renaixenca (2006):

Probably for those few decades (1850-1870) the greatest active Saint-Simonians were Monturiol & Cerda and Napoleon-III & Haussmann, though curious to see the former were socialists and the latter were the opposite. But they shared the principles of “Enlightenment valorization of scientific knowledge”. Barcelona was a veritable manifestation of Saint-Simonianism: with only 10% of Spain’s population it had 60% of Spain’s industry.

“How could anyone imagine that London, anywhere, is denser than Paris, anywhere whether intramuros, Petite-Couronne or Ile-de-France.”

I never said that Intramuros or Petite-Couronne was less dense than London, quite the opposite, they are both denser for areas of equivalent area or population in London.

But I don’t have to *imagine* that Ile-de-France is less dense than Metro London, I *know* that it is because the figures are right here in the thread. Let’s get to some even better figures!

“For Greater London you’ve done exactly what I pointed out is against the convention on how one calculates density, namely any large un-developed land (and water) is excluded. It is absurd to include the Greenbelt’s ≈5,000km2 in such calculations if you want comparable, meaningful figures.”

My figures are exactly comparable because I am taking equivalent definitional areas (Ile-de-France, Metro London) or areas of generally similar population. But let’s find some figures that exclude “large un-developed land.” The British Office of National Statistics defines the Greater London Built-Up Area. It omits wooded area and isn’t identical to Greater London the polity (it includes areas beyond it, and omits some within it). GLBUA has 9.78M in 1,738 km2 for a density of ~5,700/km2. France’s INSEE defines the ‘urban unit’ as a contiguously built-up area, and for Paris it is 10.86M in 2,854km2 for a density of 3,8000/km2.

I know this is where you will cry “but they must be including Bois de Vincennes and you shouldn’t!” however London has Richmond Park, Hyde Park, etc. Face it, at scales larger than the Petite Couronne London is denser than Paris.

“Three quarters of Ile-de-France live in Petite Couronne + Paris at density of ≈8,000/km2.”

Ile-de-France is 12.27M. The Petite Couronne (Intramuros + the three inner departments) is 6.79M. That’s only 55% not 75%. Density of the Petit C. is ~9,000/km2 (not 8,000) per official French figures, denser than an equivalent area of London. I know you really want to believe certain things about Paris, but facts say otherwise. Density of the Paris Metro/Urban area is less than Metro/Urban London.

@Onux

[earlier I missed your second comment]

To the overall city comparisons. I think your own figures prove the point. Obviously inner Paris is much denser by several factors than inner London (indeed, unlike Paris, parts of inner London are relatively short on private residences). To the greater metro areas of both cities. Here, I see that we are talking about different things. I have a graphic of IdF superimposed on greater London (the link is dead, or at least has changed since the original post of 2015: https://citymonitor.ai/government/screw-it-heres-map-paris-superimposed-london-976) and, while I haven’t verified it (one of these days I’ll try to do it de novo from Google maps) it looks right, and notwithstanding the different and irregular shapes, the edges of London corresponding to the edges of IdF are St Albans (north), Slough (west), Woking (south-west), Tunbridge (south-east) and Romford/Brentwood (east). To me, these are all in London, and this area is perhaps a bit smaller than IdF’s 12,000km2 but not hugely. And I’d say another pointer would be the Metro (Underground, RER whatever) which actually goes further out than this, eg. Metropolitan line to Amersham and Uxbridge.

But what you presented is “1,738 km2 for a density of ~5,700/km2”. So, as if often the case, we’re not comparing like-with-like. Indeed you give the entity we should be comparing: Paris + Petite Couronne which is smaller but broadly comparable in both area and population; your figures: 6.79M [on ≈750km2] at ~9,000/km2. And actually if extended to cover the equivalent 1700km2 I reckon it would remain of similar density (the PC boundary remains fixed but the densification zone grows outwards). But anyway, do not get hung up on exactitude (sheesh so sue me for saying PC was 8,000 not 9,000/km2!) but on why any of this matters. London has a housing crisis based on lack of housing and especially on affordability. Paris (and here one has to include at least the PC if not IdF) does not. (Forget the bullshit Anglo media that carp on about “Paris” affordability when just literally 100m across the Peripherique the prices drop bigly.) More than that, London has crap urbanity, and seriously crap unless you are seriously rich. No one on average incomes can live anywhere convenient nor afford all the so-called delights of London the travel mags go on about; more or less the exact opposite of Paris/Greater Paris.

This all comes down to the housing typology. I read recently that the densest part of London (as a district, not some ridiculous 1x1km square!) is “west London” by which I believe they mean Notting Hill, Kensington etc. This is because the most common residential typology there is the 4-5-6 storey townhouse typically divided into multi-apartment dwellings (not like more exclusive zones like Chelsea, Belgravia or Mayfair etc which have similar townhouses but which are SFH and strictly for the monied class, well the most monied class). Go further out and it quickly becomes SFH-terraces at much lower density. Anyway West London is apparently 10,000/km2, so you know, a fraction of Paris’ (or Barcelona) average; and of course this is not even a like-for-like comparison (eg. probably ≈5km2 versus 89km2 ie. one district versus a whole city).

You can’t achieve the required density with SFH-terrace housing, ie. the dominant London house. This is possibly why they built hi-rise social housing post-war but we know where that led (in most cities including Paris-IdF) and they are not about to repeat that error (probably; I’m not convinced the blingy hi-end hi-rise won’t turn into the same failures a la JG Ballard). Would building on the Greenbelt solve London’s problems? I doubt it. While it could technically fill the supply gap, the fact is that such housing would be both too expensive and by definition, have the longest commutes. What is most needed is truly affordable housing and properly within the city for these residents/workers who keep the city running. The solution is to densify in existing London and with Haussmannian typology which is proven to give density and urbanity. (One could almost call those 5-6 floor Georgian London townhouses “Haussmannian”. What it’s called is not important.) Who knows, it could even reverse the urban decline seen everywhere: local pubs shops are closing etc.

This is what Elizabeth Farrelly (Australian architect-urbanist but to my knowledge she has never lived in Paris) has recommended last week for Sydney which is sprawled across about 7,000km2 (of course at even lower density than London) and is close to “full up” due to being enclosed by the ocean, the Blue Mountains and huge national parks north & south (which is just as well because people at the edge already do 50+km commutes). But being Anglos, neither London or Sydney nor anywhere in the Anglosphere will do it. They’ll stubbornly stick to housing typologies that have given us the exact problems we’re trying to solve, plus the bonus of depressing drab urban environs.

“As to Eixample, you appear to be wilfully misinterpreting what I wrote. I did not write “The Eixample was “enclosed” by ***open land*** the same way other cities are enclosed by walls or islands by water!!?!!?!!?””

Your ***exact words*** from this thread posted at 2023-09-15 – 17:56:

‘Further, the Eixample was in fact enclosed by old Barcelona: the old city to the south and the old towns of Gracia, Sants & Sant Andreu to north, west & east. Same effect as a wall or the water-walls of Manhattan.’

I know it is an overused phrase but you *literally* said ‘Same effect as a wall or the water-walls of Manhattan.’

The fact that there was a village at one edge of the Eixample and another village kilometers away with completely open space in between does not in any way shape or form have the same effect as a wall or the shore of an island. You cannot build on water or walk through a wall, you can do both on an open field. To state otherwise – as you did – is what is discourteous to logic.

To be clear, the open space around Barcelona was not ‘enclosed’ by Sants, Gracia, etc. It was not enclosed in the sense of being surrounded – the villages were a few hundred meters wide with kilometers between them. It was not enclosed in the sense of being bounded – the open space continued for kilometers beyond them to Badalona, Llobregat, etc.

Onux: “The Eixample was “enclosed” by ***open land*** the same way other cities are enclosed by walls or islands by water!!?!!?!!?””

MJ: the Eixample was in fact enclosed by old Barcelona: the old city to the south and the old towns of Gracia, Sants & Sant Andreu to north, west & east

I admit I don’t even know why you are using *** but your edit of what I wrote is nonsensical and inverted my meaning. I guess you are sticking with your odd interpretation, which means there is nothing more to ***discuss***.

It is on topic. The vast majority of the population did not live in cities until recently.

No, the topic is cities. Not nationwide demographics.

“tax points for goods entering the city….Indeed that was the sole purpose of the last wall built, the Thiers Wall of 1844.”

This is completely wrong. The primary purpose of the Thiers Wall was defensive:

1) Initial planning began in 1818, after the Allies captured Paris in one day in 1814 (Louis XIV had previous walls demolished).

2) The impetus for construction was the Oriental Crisis of 1840, when France faced war with Britain for the first time since Napoleon.

3) Work was overseen by the Chair of the Fortifications Committee, not any tax official.

4) The wall was built with defensive features of the day (scarp, counterscarp, glacis) totally unnecessary for a tax wall.

5) In addition to the wall there were 16 forts built outside the wall for advance defense – again totally unnecessary for tax collection.

6) There was a zone hundreds of meters wide outside the wall kept clear of buildings for fields of fire.

7) The wall and forts were in fact manned to defend Paris against the Prussians.

The Farmer’s General wall built in the 1780’s was a wall designed solely for tax purposes, with none of the features above.

> I mean Euro cities suffered a population decline with the plague but they all survived and growth eventually picked up–in exactly the same cities which remained prime (as centres of rule & commerce etc).

I think a better frame for this is “many places where early cities were built, remained good places for cities over historically observable time scales.” We have plenty of examples of ancient cities–Babylon, Nippur, Mohenjo-Daro, to name a few–that stopped being good places for cities due to environmental changes; that’s why they’re now archaeological sites.

By contrast, lots of Old World cities that went through similar processes largely eventually became “good places to have a city” again. There was the Roman example cited earlier; a similar thing happened in the sometime Chinese capitals of Luoyang and Chang’an (which went from “largest city in the world” status at their heights to “mostly depopulated” for several hundred years due to political shifts). But they were also sited at good points on the Yellow River, so when the political context later shifted, they got repopulated.

But that doesn’t point to something “resilient” in the nature of old-growth cities themselves. “Resilient” implies the ability to avoid decline in the first place, or advantages that lead to uninterrupted continuity of high-level population. This is more “the site has natural advantages that make it worth rebuilding here later.” If you control for “advantageously located”, there’s no obvious connection to urban-vs-suburban.

To be concrete about it: if a magical force of time-traveling Viking raiders appeared tomorrow and completely razed Westchester County while (somehow) leaving New York untouched, I guarantee you that people would be drawing up rebuilding plans as soon as the last longboat was headed home. Not because suburban bedroom communities are somehow innately resilient, but because you aren’t going to leave fallow a bunch of land that’s a decent commuting distance from Manhattan.

—-

To return to the original post that Alon’s citing: that post describes ‘traditional cities’ as “complex, emergent systems that are strong, adaptive, [and] resilient.” This is not just specious, it’s practically self-contradictory–emergent behavior is exactly what gets *disrupted* if any of the underlying conditions change, and complexity means a lot more underlying conditions that have to be just right for the emergent behavior to occur. This is why you get the concept of “low” and “high” equilibria (discussed in e.g. https://acoup.blog/2022/02/11/collections-rome-decline-and-fall-part-iii-things/). If you want to argue that urban polities are more resilient, you really have to point to some kind of homeostatic or damping process, which is a lot less obvious–while cities are certainly “homeostatic” in the sense that (from time immemorial) the people who enjoy their benefits have tried to keep non-residents from likewise enjoying their benefits, that doesn’t differentiate cities from suburbs and it certainly doesn’t predict greater resilience in the NIMBY polity…

Perhaps this is where the mutual lack of comprehension comes from. To me, any response to changes to underlying conditions (in cities) is “emergent”. What else?

We’ve seen in the past 200 years amazing changes to our big cities. From Paris & London’s potable water supplies and sewers in the 1860s, to roads & bridges and street lighting, to rapid transit especially Metros above or below ground, to regulation of air quality, and of course the nature and scale of buildings (and solutions that permit them, elevators, escalators, air-conditioning, special window glasses). Today we see the move to reduce vehicle dominance and biophilic design, eg. taking back street parking for other uses during Covid. Even micro-mobility solutions. All of that is emergent and IMO shows the continued resilience of cities, perhaps with the qualification of less in American cities.

That original chart did indeed have much wrong with it, underlining error or gross generalization between city and suburb. Having been a child of the suburbs, I’m now more a fan of urban concentration, even though hometown Girona is not at all a huge city. During age of population explosion chief reason to concentrate human species in cities is for preservation of what’s left of farm and wildlife habitat. Spreading human habitat into widely spaced single family home suburbs not only destroys farmland and animal habitat, appears unsustainable economically because of longer distances for basic services of water, sewer, fiber optic, police, ambulance, garbage, street pavement, transit, etc. But, mega cities like NYC nevertheless destroy habitat far away by virtue of destructive extraction of resources elsewhere on wholesale basis, their wasteful of import of energy by a grid, energy waste in delivery of products, wholesale export of garbage waste, etc. But, careful analysis of farm, factory, warehousing, and energy (despite rooftop solar), will still show suburban single family home or row house, stick or brick construction like is currently popular in USA and UK will be more wasteful than the grimy urban core. This is because the same farm, factory and energy grid that supplies the city by countless 53′ trailer load full must also do same in suburb, with suburb having longer delivery span for smaller widely distributed retail units.

Yeah, there’s a big gap between “it’s more economically efficient for cities to be compact” or “it’s more economically efficient to use public transportation than cars” than “traditional cities are timeless, honed over millennia.”

You have to remember that Strong Towns is an American movement. “Timeless” here means, at most, late 19th century, unless we’re talking about New York or other older east coast cities, but then, those aren’t “real America” to a lot of people.

It also helps to remember that the founder lives in a city with about 25,000 residents (Brainard is 14,000, Baxtor 7000, plus some small towns close). That number easily doubles on summer weekends as it is a tourist area (A large number of people who live in Minneapolis – ~2 hours away – own a second home in the area – people in MN are much more likely to own a second home vs anywhere else in the world).

This makes his experience with cities very different what most people reading this think of as a city. He has occasionally used a definition of suburbs to include places that none of us would recognize as a suburbs.

It is not at all my impressed that any city in the world before 1850 or so had any meaningful amount of anything that could be commuting. If so it would be because of restrictions in the urban form where some central palace or urban area was of limits to live in, and some people would be forced to take longer walks to get there. Non-walking mobility except for the very elites were not the case anywhere I think.

That the urban form of the largest richest cities like London, New York and Berlin was heavily shaped by commuting in 1850-1920 I agree is clearly correct though.

Even if we consider only the transport technology and not the unrelated ways in which the pre-car world was inferior to today (coal heating, lack of antibiotics), there’s nothing to be nostalgic about.

Horses and their excrement were everywhere and their drivers still asserted their ROW violently and occasionally killed people in traffic accidents (most famously Pierre Curie).

Cobblestone streets are awful to cycle on, especially before the invention of pneumatic tires. Also not ideal for walking either, Pierre Curie’s accident involved slipping on wet cobblestones.

Surface public transport was really slow, and while rapid transit was already a thing, S-Bahns didn’t really exist yet (or were really uncommon, I don’t know my history perfectly).

I think disease, mostly due to bad sanitation, was by far the biggest disadvantage of cities prior to 1900 or so.

For sure, but you can imagine fixing that without inventing the internal combustion engine.

Exactly this; it is possible, to rationally, discuss specific aspects of a time or place.

Not without counters though. But they usually require state investment usually from Imperial states taxing provinces. Although the semi-autonomous communities of the Principate did a lot on their own. Rome-Constantinople had aqueducts and cisterns. Or you have the East Asian model which reached its peak with Early Modern Edo, wooden pipes, canals and an economy of shit (as fertiliser)*.

*Edo rental agreements often included clauses about who got to sell the piss and who got to sell the Poo.

But most cities didn’t have either the revenues or the political incentives.

A thing on pre-modern urban fragility…yes and no. I mean there are some places that have very intense urban collapse most notably Mesoamerica where relatively weak water communications geography means cities are very dependent on tribute or narrow and vulnerable agro-ecological bases (Teotihuacan, Tikal etc) hence you get urban collapses that make the fall of Rome look like a cakewalk. Chinese and Indian urban settlements often have consistent regions (Xian area, Delhi area) with the cities being torn down and rebuild according to Empire du jour. After the Northern Song if not the Tang though you get a much more stable urban system based on trade with politics, economics and ecology changing the balance of importance not existence (top city Jiangnan; Northern Song its Hangzhou, Early Ming Nanjing, Late Ming Suzhou, Qing Yangzhou, Post-Qing Songjiang becomes Shanghai). Indian cities stay much more unstable until the British conquest.

But in West Eurasia lots of cities have ancient pedigrees and continuous settlement. In Western Europe the survival of as cities as bishops headquarters then the creation of borough/city states in the high middle ages anchors things. In the Islamic world urban living never really stops and the elites are always living there. The exceptions are North Africa and Egypt where the post-Roman collapse of Med trade roots pushes government inland to Cairo and Kairoun until the Fatimids (in competition and co-operation with Italians) rebuild the system on new cities (Tunis, Damietta etc).

Borners rules for pre-modern urban continuity 1. Water trade seaborn especially 2. Anchor institutions 3. No super-empires

Regarding pre-modern urban continuity, what of maritime Southeast Asia? Most cities there were city-states (sometimes one became a small kingdom or empire like Majapahit) so there were no super-empires, they all depended on maritime trade, and they just kept getting abandoned or moved once market conditions changed. I’m thinking in particular of Singapura, which shut down like 200 years before modern Singapore was built on its ruins, but examples are all over the place. Basically trading cities kept getting founded and abandoned pretty regularly. Though I’m not sure what you meant by anchor institutions.

Someone correct me if I’m way off, but as far as I know, an anchor institution is any form of organization that is geographically fixed for a long time for various reasons. Some of these–especially land-intensive ones such as agriculture–don’t lead to urbanism because it’s not ultimately the people in those places that matter; farming in the American west doesn’t ultimately depend on any particular variety of people to work the land (though which group of people it is may affect other factors).

The most prominent in my mind are governmental and educational institutions. Moving a capitol or a major university is a rare thing relative to, e.g., moving a factory or retail store (though of course these can be anchor institutions if they’re around long enough).

Ayutthaya is also a good example of a hugely important city where hundreds of thousands of people lived that was later razed to the ground.

The modern city is located some distance away from the ruins of the old city, and is also much smaller (~50k people).

Governments with large bureaucracies or significant “elite-democratic-ish” elements (e.g. House of Commons pre-Ind. Rev.) have difficulty with moving their capitals. However, historically many governments did not have these features, and the royal court would regularly move about, thus to the extent anything resembling a singular capital even existed, it was relatively mobile.

Rough stages of development:

1) Long/indefinite-term (sometimes outright hereditary) vassals, who are in some ways allies rather than proper subordinates.

2) Governors on short, definite terms. They can still revolt, because they both raise taxes and spend it on the military, but at least they quickly run out of legitimacy.

3) Ministers, dividing the functions of tax collection and (military) spending at the highest level of organization, and the geographic subdivisions of the respective ministries are siloed from each other. Requires lots of literate bureaucrats.

Wait – stage #2 isn’t exactly “governors” but something like “governors who have authority over the local garrison,” like Byzantine themes or Early Modern European colonial governors on fixed terms (Portugal did three years to optimize between local knowledge and revolts). But then American governors today have control over the National Guard, which they use for disaster relief, photo-ops for running for president, etc.

SE Asia is complicated and the least understood because we have so few documentary sources and the archaeology is immature outside Ankor Wat. Ecology is part of it, Tropical zone agriculture is quite difficult because soils are generally poorer and cutting down forests can cause rapid river course changes or even aridity. But that hasn’t stopped Hanoi being Vietnam’s main northern city for a very long time albeit under different names in a very Chinese pattern.

Its not just stability of capitals, at least in West Eurasia (i.e. Christendom and Islamdom) commercial or regional capitals are pretty stable even with their names.

Anchor institutions; religious institutions are the big ones in the premodern world. The Abrahamic faiths in particular because they have weekly community worship inside them, build in masonry and prefer to nick each other’s buildings rather abandon them. Buddhism can have some of that (Nara and Kamakura maintain some significance thanks to just 100 years of foundations) but its greater reliance monastic foundations are a weaker basis than community worship

N/b These patterns follow documentary continuity very well. Oldest paper continually preserved paper trails are in Europe (we have late Roman legal casework copies from St Denis and the Vatican), Middle East (Armenia and Egypt) and Japan/Korea*.

*China is weird. The literary source tradition in China is by far the strongest surviving thanks to scale and early printing. But actual continually preserved archives are absent. We have more from Medieval Catalonia than Medieval China. That’s because new dynasties tend to year zero things which makes land documentation preservation kind of pointless.

My understanding is that Chinese sources have been decently integrated into SE Asian studies but Indian ones haven’t because a lot of their scholars are Hindutva “you’re actually part of Greater India” weirdos. Which of course sets off the SE Asian scholars.

The Chinese sources are the main literary sources for anything pre-1300 in SE Asia. There are problems there since Chinese historians underestimate how import SE Asia is. I remember reading Keith Taylor great history of Vietnam where he reveals part of the reason the Song dynasty Wang Anshi reforms is he gets them involved in a war against Dai Viet. And there similar stories for the Yuan and Ming (none of the puff pieces on Zhenghe fleet mentions the attempted conquest of Vietnam).

Depends what you mean by India. Since the best South Asian sources for SE asia are Sri Lankan. You don’t need just Hindutva dicks. Indian history as done by the Congress tradition is trashfire bad since its basically a bunch of brahmins related to Congress politicians whining about how everybody is mean to them. And because western historians are generally gullible racists (the Mughals were awesome because they translated Upanishads into Persian! The British invented caste etc). Hinduvta seeped into the vacuum they manufactured.

Part of that history is to write Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka or what’s now Bangladesh out of the story because they don’t recognise Delhi’s overlordship. SE asia connections are either vague globalisation-connections studies or puff-pieces on a Chola dynasty attempt to build a trans-bay of Bengal empire. It makes English attempts to write the Celtic fringe out of their history look respectable.

Yes, the gears matter, not the job title. A proconsul is an example of “appointed governor”, whereas the thing that US states (uhh!) have is functionally closer to a mayor.

For most of human history cities had a higher death rate than birth rate and the population was maintained or grew through migration through rural areas. It wasn’t until sometime in the 19th century that the birth rate in cities exceeded the death rate and city growth was natural.

Sure, but it would be misleading to attribute all of that to the ‘toxic’ effect of cities. Some of it was the phenomenon of people with higher education and better employment and income choosing to have smaller families. Eventually that spread to rural areas until today the entire developed world has endogenous ZPG and only grows thru immigration.

As a Strongtowns member, and even a local chapter organizer: Yes. Everything you said is true. And it is frustrating. Sometimes all the “incrementalism” talk requires a few deep breaths, it is completely ahistorical.

So many cities in the Midwest, including mine (Grand Rapids, MI), were rapidly developed mercantile downtowns next to a railyard. Nothing incremental what-so-ever.

Fortunately most Strongtowners I know understand that the Strongtown’s message around transportation infrastructure, like rail, is gonzo. Chuck is a fun guy to listen to, but sometimes: yikes! OTOH, I’d take his brand of “yikes!” over the whimpering and hang-wringing of my local ‘leaders’. In the end that’s what politics seems to be – choosing the most tolerable brand of yikes.

Chuck Marohn did start with that important insight in his home town that the new business that was up to the latest auto-oriented standards paid less tax than the total from the 3 or so old businesses it replaced.

The rapid growth of American cities in the 19th Century is very comparable to rapid urbanization in China and other developing nations, certainly not developed incrementally over centuries by tinkering. This makes urbanism sound like gardening, which is perhaps the problem when too much historic preservation and NIMBYism prevents new housing being built, leading to ever more expensive cities.

I think the argument here is that 19th century urbanism was done by individual land and property owners. I know enough to say that it was, at the very least, not solely that, but I know little enough to say how much of it was top down, though I suspect it’s more than Strong Towns thinks.

My biggest issue is with the thinking that says that good urbanism can ONLY be done incrementally. However much that was the case in the past, the invention of mass transit makes it at least inadvisable. Once you start needing to coordinate multiple bus lines, building out a tramway network, building a subway line….These are not things that are going to be done individually or communally. A professional, apolitical bureaucracy is just unavoidable beyond a certain level of population or economic activity unless you want it all the be unsustainably fragile.

It’s the refusal to acknowledge that–and the consequent failure to realize that many, many more American towns/cities are already at that than just NYC, LA, Chicago, Boston, Seattle, St. Louis, etc.–that I think does the most damage to Strong Town’s most defensible position (the suburbs as Ponzi scheme).

Yes. As adamtaunowilliams alluded to, during their era of westward push, the railroads founded lots of towns, and invariably built a relatively standardized (i.e. top-down planned)… well, hamlet or small village, just for the people working the station itself. Other that that, rapid development of a few of these nuclei into actual towns or even cities — on the one hand, it happened on the standard street grid platted by the railroad, but on the other hand, it happened mostly by individuals (households) or small companies buying individual plots.

On the second point, Alon already has a post:

“My suspicion is that this involves business culture. Urban transit is extremely Fordist: it has interchangeable vehicles and workers, relentlessly regular schedules, and central allocation of resources based on network effects. […] The idea that there should be people writing down precise schedules for service is alien, as is any coordinated planning; order should be emergent, and if it doesn’t work at the scale of a startup, then it’s not worth pursuing.”

By the same token, I think that several items in the table would be better understood as referring to the Invisible Hand (addressed to an audience which requires that) in opposition to central planning. This particularly influences two items:

– “energy comes from the bottom upward vs. from the top downward”

I would like to propose that here “energy” refers to “initiative” (or some word referring to ultimate deciding power). That if I want to build an ADU, or turn the front of the building into a café,

nobody can veto itthe only person who can veto it is my wife.– “antifragile”

Perhaps I’m too charitable and am overinterpreting this, but I think this should be understood to mean something closer to graceful degradation. The arguments around growth scenarios take the spotlight — by-right piecemeal densification — but equally, scenarios around shrinkage should be looked at. If two factories are the “economic purpose” of a town, and one of them closes down, then it is entirely correct if a roughly proportionate fraction of the total population — most of whom are stuff like grocers, barbers,

candlestick-makersteachers — ends up leaving. The people directly working in the one remaining factory neither need, nor can pay for, as much “support” or “comfort” as the combined worker pool of both factories.It messes up this scenario if there are big nonlinearities, make-or-break things, anything of the sort where someone sits down and checks, to a yes/no result, whether an idea pencils out, based on assumptions that can later turn out to have been wrong. Some of these are physical infrastructure (and Strongtowns has been beating the drum about overcommitments to roads and utilities), sometimes they are purely financial (since municipal governments sell bonds, where they either pay in full or are bankrupt, rather than stocks or some other kind of instrument that can float/”feather fall”). Now a town cannot elastically shrink, moving down a steady slope (of less consumption amenities), but there are at best cliffs where suddenly the town doesn’t generate enough wealth to justify its utilities, transport network, etc., and realistically the actions people and organizations take worsen the situation (allegorically, they try their damnedest to avoid falling off the cliff and having to admit they fell off, thus instead they do as Wile E. Coyote, walking off in mid-air (supported on deferred maintenance and debt), as the slope continues to recede under them, therefore when they do eventually fall, they fall a greater height all at once). Hence “brittle” — “make or break”, not stretch.

Post-Covid, the idea that cities are less fragile than suburbs seems like a farce. Presented with the stress of a global pandemic, it was cities that lost population and economic activity as people chose (or were forced) to work from home. While commercial real estate values in cities dropped as businesses shed office space, residential values in the suburbs went up as some people decided they didn’t want to live in the city if they didn’t have to commute. While downtown dining/retail struggles, suburban establishments are seeing an uptick. The effect varies (San Francisco seems to particularly hard hit, other places less so) but you can’t escape the fact that in a globally disruptive event the suburbs got better while cities got worse. Strongtowns’ fragile argument seems baseless in practice.

@Onux I think you’re missing several important points, here.

1. Kind of a meta-point, but the COVID-induced flight from cities seems to have been worst in North American cities, in part because downtowns in NA are job centers before they’re anything else. The same level of flight didn’t occur in East Asia (in part because they managed the pandemic better)–nor, to my knowledge, in most of Europe–because people don’t live outside the city and commute for work to nearly the same extent

2. I know people like work-from-home, but I think that change isn’t going to be as permanently dramatic as it has been for the past couple of years. Yes, lacking the obligation to physically be somewhere is nice, but that your home (even if it’s just a room in it) is now also a place where you work seems like a further erosion of the work/home boundary that I can’t help but think employers will do whatever they can to take advantage of. There’s also the fact that you do lose SOME amount of efficiency from spontaneous in-person interaction. That particular efficiency is among the reasons that collaborative workspaces of any kind exist at all.

3. San Francisco, like every West Coast city (including my home region of Portland), was dealing with a trifecta of too-slow development causing higher rents, increasing drug usage with a lack of support services, and–I think this is substantially underrated in the gravity of its effects–media fearmongering about both of those causing a positive feedback loop making people all-too-ready to abandon ship. Honestly, the way the press here talks about downtown–never even mind during the “riots” that were just a few handfuls of protesters in one central square–is completely disconnected from reality.

TL;DR, “suburbs got better while cities got worse” is only meaningfully true because America does cities badly and Americans have been predisposed to think cities are prima facie bad since segregation became de jure illegal.

1. Strongtowns is an American organization and it’s critique of the “suburban experiment” applies almost entirely to post-war American development so if American cities are declining while American suburbs are growing under stress that completely invalidates their argument that suburbs are more fragile.

2. It doesn’t matter if WFH is a good idea or is permanent. What matters is that under stress (global pandemic, massive unemployment (admittedly by choice), economic disruption) cities with a “traditional” development pattern generally did worse (population loss, budget problems, shrinking economy) while suburbs of the post-war experiment did better. This is the exact opposite of what Strong Towns claims: the cities were more fragile (did worse under stress) than the suburbs.

3. First west coast cities were booming before Covid, populations rising (Seattle fastest in the country at some points), budget surpluses, Silicon Valley (suburban office parks) was becoming Silicon Alley (Twitter downtown and Salesforce Tower). Sound Transit 2 & 3, Tillikum Crossing, Caltrain electrification; the feedback loop was positive in that everything was looking up. Second, if there were underlying structural problems making people ready to leave the city that just further undercuts the strong towns argument that the traditionally laid out cities are more resilient (according to ST the suburbs are supposed to have the underlying issues). Third, I’m well aware the media distorts most things, and that SF and Portland are not continuous slum (neither does every Chicago and Philadelphia corner see a murder each weekend). But the “media’s fault” argument falls apart in relation to out migration because it’s not as if someone living in Portland needs to watch the news to know what Portland is like – they see it everyday and know much more than a news anchor. And people are choosing to leave.

Fourth, this isn’t a West Coast thing. Chicago, NY and DC have all lost population. Fort Worth growth slowed to about 1%. People are choosing suburbs over cities. Strong Towns was wrong.

Onus, outside the North East and Mid-West, determining the difference between city and suburb is hard. Many Sun Belt cities like Fort Worth or Phoenix are collections of suburbs under one municipal government. There may or may not be a traditional downtown. Lots of Sun Belt Cities are basically giant suburbs. In the Bay Area, San Francisco is built more like an East Coast city but also has a lot of single family housing that looks very suburban. Same with Oakland and Berkeley.

@Onux

First, even American cities are not declining (on any meaningful timescale), ie. the growth of the suburbs (which is not in contention) is due to overall national immigration & growth.

Second, cities, ie inner-cities, even American ones, will recover from Covid and will continue to grow in popularity and to meet that they will continue to densify. Possibly more on their inner-fringes but still.

The effect of Covid was somewhat paradoxical in that I don’t for a second believe it was any ‘better’ for surviving Covid than anywhere else, and I know I was glad to be living in the inner city than the isolated suburbs where you’d go crazy (or crazier). In Australia there was a “treechange*” movement during Covid but that was not people relocating out of inner cities to country towns but suburbanites fed up with endless commutes from exurban zones where they have to spend their lives driving everywhere for absolutely anything (work, sport, school, retail, entertainment etc) all of which I can do on foot. Of course it can only be possible for a relatively tiny fraction of the population for reasons of jobs–either those rare local jobs or a job that can be done WFH.

*Treechange is a variant on the more popular seachange, ie. relocating to a seaside town which is no longer affordable for the majority of Australians. The term seachange actually came from a tv sitcom of that name from 2 decades ago.

> but I know little enough to say how much of it was top down,

The Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central railroad existed; even into the Midwest. It was all very top-down and financialized. Differently than it would be today, but to say most American cities were built bottom-up is, IMO, essentially ahistorical.