Category: Transportation

Why Building Metros is Necessary for the Green Transition Away from Cars

There’s controversy in Germany over building U- and S-Bahn extensions, in which environmentalists argue against them on the grounds that people can just take trams and the environmental benefits of urban rail are not high. For example, the Ariadne project prefers push factors (green regulations and taxes) to pull factors (building better alternatives), BUND opposes U- and S-Bahn expansion, and a report endorsed by Green politicians argued based on shoddy analysis leading to retraction that the embodied carbon emissions of tunneling exceeded any savings, which it estimated at only 714 t-CO2 per underground km built. Against this, it’s important to sanity-check car and public transport ridership to arrive at more solid figures.

To start with, virtually everyone travels by car or by public transport. There’s a notable exception for cycling, but cycling is typically done at short ranges, and the metro expansions under discussion here (all outside the Ring) are beyond that range. In Berlin, the modal split for cycling peaks in the 1-3 km range and is small past 10 km. Beyond the scale of a neighborhood or maybe a college town, cars and mass transit are substitutes for each other.

Nor does public transport expansion lead to hypermobility, in which overall trips grow longer as people commute from farther away and car use doesn’t decline or only weakly declines. If anything, the ratio of substitution for passenger-km rather than trips is that a p-km by metro substitutes for more than one p-km by cars, because metro-oriented cities can be denser and allow for shorter commute trips. Berliners average 3.3 4.6-km trips per day, or 15 km/day; Germany-wide, it’s 35.5 km/day (see table 11 of MiD). If anything, the presence of a large city core also shortens the average car trip by reducing exurb-to-exurb driving at low density.

Nor does polycentricity solve the problem. Indeed, ridership in polycentric regions is weaker than in monocentric ones. MiD has data by state and Verkehrsverbund in Germany, with modal splits by trips (all trips, not just work trips) and passenger-km, the latter measure having far less in the way of cycling and walking. From this, we have the following table:

| Geography | Transit % (trips) | Car % (trips) | Transit % (p-km) | Car % (p-km) |

| Berlin | 27 | 24 | 47 | 40 |

| Brandenburg | 9 | 51 | 22 | 71 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 7 | 52 | 14 | 80 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 9 | 48 | 12 | 81 |

| Saxony | 11 | 56 | 16 | 77 |

| Thuringia | 9 | 55 | 16 | 79 |

| Hamburg | 22 | 29 | 43 | 47 |

| Bremen | 14 | 33 | 30 | 60 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 8 | 56 | 14 | 79 |

| Lower Saxony | 8 | 53 | 15 | 77 |

| Nordrhein-Westfalen | 10 | 55 | 18 | 74 |

| Rheinland-Pfalz | 9 | 57 | 19 | 75 |

| Saarland | 10 | 65 | 15 | 79 |

| Hesse | 12 | 52 | 19 | 74 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 9 | 53 | 17 | 75 |

| Bavaria | 10 | 56 | 18 | 75 |

| Munich (city) | 25 | 29 | 39 | 51 |

| Frankfurt (city) | 24 | 29 | 38 | 52 |

| Stuttgart (city) | 23 | 36 | 33 | 60 |

| Munich (MVV) | 19 | 41 | 31 | 61 |

| Hamburg (HVV) | 16 | 33 | 29 | 63 |

| Hanover (Region) | 15 | 42 | 25 | 66 |

| Rhine-Main (RMV) | 13 | 49 | 22 | 71 |

| Rhine-Neckar (VRN) | 10 | 51 | 17 | 75 |

| Rhine-Ruhr (VRR) | 12 | 53 | 20 | 73 |

| Rhine-Sieg (VRS) | 12 | 49 | 22 | 70 |

Berlin is by all measures the most public transport-oriented and least car-oriented part of Germany. The source doesn’t explicitly break out VBB, but VBB comprises Berlin and Brandenburg, whose population ratio is 59:41, so we get a modal split by trips of 20% transit, 35% car; a similar computation for p-km is less certain since Brandenburgers, many of whom commute to Berlin, have longer trip lengths, but it’s likely Berlin and Brandenburg’s combined modal split is slightly better than those of MVV and HVV, both monocentric. Brandenburg, notably, has the highest modal split by p-km outside the city-states, owing to the Berlin commuters.

In contrast, the polycentric regions – Rhine-Neckar (Mannheim), Rhine-Ruhr (excluding Cologne), Rhine-Sieg (Cologne-Bonn), and to a large extent also Rhine-Main (Frankfurt) – all have weak modal splits. The cities themselves have healthy usage of public transport, judging by the data that’s available and by ridership on their Stadtbahn systems, but most of the Rhine-Ruhr’s population doesn’t live in Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Essen, Dortmund, or Wuppertal, and this population drives.

The upshot is that rail development that strengthens city center at the expense of suburban job clusters should be considered a positive development for transitioning from cars to public transport. Job clusters outside city center do not reduce commuting, but instead make commuting more auto-oriented.

This, in turn, creates serious estimation problems for the diversion rate, which is why environmental benefit-cost analyses underrate the effect of urban rail construction. An expansion of a north-south line like U8 would not just increase the residential connectivity of Märkisches Viertel but also, on the margins, increase the commercial connectivity of Alexanderplatz and other central stations served by the line. This, in turn, should induce additional ridership on lines nowhere near Märkisches Viertel, for example, east-west lines like U5 and U2. At the neighborhood level, the construction of the line would create a lot of induced trips and not have a high diversion rate from cars. But at the city level, little examples of diversion as more work and non-work destinations cluster in Mitte would multiply, never enough for an easy comparison, and yet enough that, as we see, more people would be living and working here without driving, where otherwise they’d be driving between two Kreise elsewhere in Germany.

Taken all together, the diversion rate at the level of trips should be considered 100%: at large enough scale, every trip by public transport is a trip not done by car, perhaps in the city, perhaps elsewhere in the country. Every p-km by public transport is multiple p-km not done by car, since dense cities allow for shorter trips without the traffic congestion problems caused by trying to fit high density and also a high modal split for driving.

With that in mind, a calculation of a first-order diversion rate is in order. A daily trip by rail is a daily trip not done by car. The average trip length in Germany by all modes is 12 km, but this is weighed down by short walking and biking trips; the average daily driving rate per car is 26 km (see table 21 of MiD) when the car is in use, and is 10,000 km/year per car. If we take 10,000 v-km to be the diversion rate per 3 public transport trips, we get that, at the emissions intensity of 2017, a daily public transport trip represents an annual emissions reduction of 0.43 t-CO2. The Märkisches Viertel extension of U8, estimated to get 25,000 trips/day, would reduce Germany-wide emissions by 10,000 t/year, which is nearly an order of magnitude more than the carbon critique of Berlin U-Bahn expansion got. At the current 670€/t cost used in German benefit-cost analyses this is around a 2% rate of return on cost purely from the carbon savings, never mind anything else – and usually green policy uses a low discount rate due to the long-term effects of greenhouse gas emissions, 1.4% in the Stern review.

Against Land Value Capture

An otherwise-good video by the Joint Transit Association about A Better Billion criticizes us for not proposing value capture to fund the scheme. I’ve seen other otherwise-good American transit advocates back this, and I’ve seen many a thinktank propose it and similar nonconventional schemes to fund public transit, in lieu of taxes. Taxes are political. Taxes annoy voters. So why not get around them by taxing development behind the scenes? It’s attractive on the surface, but in truth, broad taxes are the only way to fund government and expect it to perform as expected; value capture is so opaque that it is very easily wasted, to the point that 100% of the funds it provides can sometimes be wasted on excess construction costs, as has been the case in Hong Kong. Good transit advocates should reject this scheme and demand that funding be as straightforward as possible, with the understanding that the part about taxes that annoys voters is what ensures the money is spent well.

What is value capture?

Value capture is the name for any of a set of programs aiming to fund infrastructure by taxing the development that it would unlock – in other words, to capture some of the value gained by the private sector. This contrasts with broad-based taxes, which capture value from the entire economy and not just from specific developments or developments in specific areas. The idea is that the infrastructure generates value not just for the broad economy but also specifically in the area it serves, so it’s right to tax that area.

In practice, value capture schemes are most common when there’s perception that raising broad taxes is too difficult politically, or undesirable otherwise. Hong Kong extensively uses value capture to fund MTR expansion, not because its taxes are too high but because it wishes to keep its taxes very low. American cities have begun looking into such schemes in much higher-tax environments, with limited willingness to fund things out of the general budget; the 7 extension in New York was built with bonds tied to tax increment financing (TIF), which promised that the higher property taxes generated by Hudson Yards development would pay the bonds back.

Which projects are funded by value capture?

Naturally, value capture and TIF systems favor projects that have the most real estate value to capture. In New York, this meant the 7 extension but not Second Avenue Subway, which the real estate advisors to Bloomberg denigrated on the grounds that the Upper East Side was already developed.

This already creates biases, in favor of not just wealthier areas (the Upper East Side is after all rather rich) but also ones with high redevelopment potential, for example because they are underbuilt. This, in turn, favors worse projects, because they serve lower preexisting density.

The dominant benefit of public transportation in benefit-cost analyses, which are not undertaken in the United States, is the benefit to passengers, representing social surplus. For an example that was just sent to me, a study from last month analyzing a further Nuremberg U-Bahn extension classifies the total benefits of the chosen alternative on p. 30 as 5.73 million €/year in passenger benefits, plus about 3 million €/year in various externalities of which the biggest are reduced accident costs and reduced traffic congestion. Similarly, Börjesson et al’s ex post analysis of the T-bana, finding a benefit-cost ratio of 6, has consumer surplus dominating the benefits of the system. Land use changes are helpful, but the main purpose of a subway is to be ridden rather than to stimulate real estate development. A Better Billion looks at the possibilities of development unlocked by new lines, but not for nothing, we also look at existing bus ridership and subway capacity problems in analyzing which projects to recommend; development-oriented transit can work but only as a secondary option, and value capture overemphasizes it in preference to other needs.

Value capture and costs

Hong Kong is famous in the core English-speaking world for linking development with MTR construction. It’s also a very good example of what not to do. I complained mightily about value capture in 2017, but if anything I pulled punches, because while I did talk about Hong Kong’s use of MTR value capture as a corrupt slush fund, I didn’t know enough to connect this with Hong Kong’s other problems:

- Very high infrastructure construction costs. They are so high that value capture only covers about half the project costs, and the other half, funded directly by the government, is still more per kilometer than the world average cost. Hong Kong, moreover, has been ground zero for the adoption of the consultant-centric globalized system of procurement – British consultants who were there in the 1980s and 90s workshopped the system and then brought it home, leading to a cost explosion that rendered first London, then Australian and Canadian cities, incapable of building urban rail. In this sense, value capture is an attempt to paper over the inability to build by using a tool perfected in the city that has extreme construction costs and can only build anything because, with car ownership suppressed by taxes, it has atypically high demand.

- Overcrowding, likely the worst in the developed world. The data out of Hong Kong isn’t quite comparable to the most overcrowded cities in the democratic world (Paris averages 31 m^2/capita). Hong Kong reports median rather than mean housing size: its median is 16 m^2, and while it has a lot of inequality, it doesn’t produce nearly a factor of 2 of a mean-median spread. Hong Kong has atypically high inequality, but even that only produces a mean-to-median income ratio of 0.67, and housing surface area is distributed more equally than income. So it’s almost certain Hong Kong is the first world’s overcrowding capital, all because the state doesn’t develop enough land or housing (net annual housing growth is 3.8 dwellings/1,000 people, low for East Asia) in order to create more profits for the MTR to fund ever growing construction costs.

The way forward

Value capture and other nonconventional funding strategies should be categorically rejected. They lead to poor project selection, high construction costs through opacity, and, in the most extreme cases, other governance problems including Hong Kong’s legendarily bad overcrowding. The only legitimate way to fund public transportation and other infrastructure project is through broad-based taxes, either directly as in some dedicated payroll and sales taxes found in both the United States and Europe or, better yet, through the general budget, debated at the highest responsible level of government (municipal, provincial, or national), itself funded largely by broad taxes.

Against Free Buses

Much of the public discussion over A Better Billion, our proposal to increase New York’s subway construction spending by $1 billion a year in lieu of Zohran Mamdani’s free bus plan, has taken it for granted that free buses are good, and it’s just a matter of arguing over spending priorities. Charlie Komanoff, who I deeply respect, proposes to combine subway construction with making the buses free. And yet, free buses remain a bad idea, regardless of funding, because of the effects of breaking fare integration between buses and the subway. If there is money for making the buses free, and it must go to fare reductions rather than to better service, then it should go to a broad reduction in fares, especially if it can also reduce the monthly rate in order to align with best practices.

Planning with fare integration

The current situation in New York is that buses and the subway have nearly perfect fare integration: the fares are the same, the fare-capped passes apply to both modes equally, and one free transfer (bus-bus or bus-subway) is allowed before the passenger hits the cap. Regular riders who would be taking multi-transfer trips are likely to be hitting the cap anyway so that restriction, while annoying, doesn’t change how passengers travel.

Under this regime of fare integration, buses and the subway are planned together. The bus network is not planned to connect every pair of points in the city, because the subway does that at 2.5 times the average speed. Instead, it’s designed to connect subway deserts to the subway, offer crosstown service where the subway only points radially toward the Manhattan core, and run service on streets with such high demand that buses get high ridership even with a nearby subway. The same kinds of riders use both modes.

The bus network has accumulated a lot of cruft in it over the generations and the redesigns are half-measures, but there’s very little duplication of service, if we define duplication as a bus that is adjacent to the subway and has middling or weak ridership. For example, the B25 runs on Fulton on top of the A/C, and the B37 and B63 run respectively on Third and Fifth Avenues a block away from the R, and all have middling traffic. In contrast, the Bx1/2 runs on Grand Concourse on top of the B/D but is one of the highest-ridership buses in the system. B25-type situations are rare, and most of the bus service that needs to be cut as part of system modernization is of a different form, for example routes in Williamsburg that function as circulators with maybe half the borough’s average ridership per service hour.

In this schema, the replacement of a bus with a train is an unalloyed good. The train is faster, more reliable, more comfortable. Owing to those factors, the train can also support higher ridership and thus frequency. If the train stops every 800 meters and averages 30 km/h and the bus stops every 400 and averages 15 (the current New York average is much lower; 15 is what is possible with stop consolidation from 200 to 400 meter interstations and other treatments), then it takes a 2.5 km trip for the replacement to be worth it on trip time even for a passenger living right on top of the deleted bus stop, and a 5 km one if we take into account the walk penalty – and that’s before we include all the bonuses for rail travel over bus travel, which fall under the rubric of rail bias.

The consequences of differentiated fares

All of the above planning goes out the window if there are large enough differences in fares that passengers of different classes or travel patterns take different modes. Commuter rail, not part of this system of fare integration in New York or anywhere else in the United States, is not planned in coordination with the subway or the buses, and fundamentally can’t be until the fares are fixed. Indeed, busy buses run in parallel to faster but more expensive and less frequent commuter lines in New York and other American cities, and when the buses happen to feed the stations, as at Jamaica Station on the LIRR or some Metro-North stations or at some Fairmount Line stations in Boston, interchange volumes are limited.

Commuter rail has many problems in addition to fares. But when the subway charges noticeably higher fares than the bus to the point that passengers sort by class, the same planning problems emerge. In Washington, the cheap, flat-fare bus and more expensive, distance-based fare on Metro led to two classes of users on two distinct classes of transit. When Metro finally extended to Anacostia with the opening of the Green Line in 1991, an attempt to redesign the buses to feed the station rather than competing with Metro by going all the way into Downtown Washington led to civil rights protests and lawsuits alleging that it was racist to force low-income black riders onto the more expensive product.

Whenever fares are heavily differentiated, any shift toward the higher-fare service involves such a fight. One of the factors behind the reluctance of the New York public transit advocacy sphere to come out in favor of commuter rail improvements is that those are white middle class-coded because that’s the profile of the LIRR and Metro-North ridership, caused by a combination of high fares and poor urban service. Fare integration is a fight as well, but it’s one fight per city region rather than one fight per rail project.

And more to the point, New York doesn’t even need to have that one fight at least as far as subway-bus integration is concerned, because the subways and buses are already fare integrated. What’s more, free bus supporters like Mamdani and Komanoff aren’t proposing this out of belief that fares should be disintegrated, but out of belief that it’s a stalking horse for free transit, a policy that Komanoff has backed for decades (he proposed to pair it with congestion pricing in the Bloomberg era) and that the Democratic Socialists of America have been in favor of. The latter is loosely inspired by 1960s movements and by reading many tourist-level descriptions in the American press of European cities with too weak a transit system for revenue to matter very much. Free buses in this schema are on the road to fully free transit, but then the argument for them involves the very small share of transit revenue contributed by buses rather than the subway. In effect, an attempt to make the system free led to a proposal that could only ever result in disintegrated fares, even though that is not the intent.

But good intent does not make for a good program. That free buses are not proposed with the intent of breaking fare integration is irrelevant; if the program is implemented, it will break fare integration, and turn every bus redesign into a new political fight and even create demand for buses that have no reason to exist except to parallel subway lines. The program should be rejected, not just because it costs money that can be better spent on other things, but because it is in itself bad.

A Better Billion and the Cost Model versus the 125th Street Subway Extension

We released a new report called A Better Billion. It was covered rather positively in the New York Times yesterday, with quotes from other transit advocacy groups. The idea for our report is that Zohran Mamdani promised free buses in his successful primary campaign, and promised free and fast buses in his successful general election campaign for mayor, so let’s take the $1 billion a year this could cost in forgone revenue and see how to spend it on subway expansion instead.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the article and on social media about the idea of free buses, but instead I want to talk about our proposal’s cost model, in the context of a rather incompetent plan the MTA released recently for a subway extension of Second Avenue Subway under 125th Street, at twice the per-km cost of Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, and twice the cost we project. Our model is not based on non-Anglo costs, but rather on real New York costs, modified to incorporate the one major cost saving coming from our previous reports, namely, shrinking station size. Based on everything combined, we came up with the following medium cost model:

| Item | Cost (2025 prices) |

| Tunnel (1 km) | $530 million |

| Tunnel, underwater (1 km) | $1,050 million |

| El or trench (1 km) | $260 million |

| Station, cut-and-cover | $510 million |

| Station, mined | $770 million |

| Station, el or trench | $240 million |

These costs include apportioned soft costs and not just hard costs. Altogether, an extension of Second Avenue Subway from Park Avenue to Broadway, a distance of 2 km with three mined stations at the intersections with the north-south subway lines, should cost $3.4 billion. This is not much less per kilometer than Second Avenue Subway Phases 1 and 2, which can be explained by the denser stop spacing and the need for mined stations at the undercrossings. If everything else were done in the right way rather than the American way, the low cost model would apply and costs would be reduced further by a factor of about 3, but the per-km cost would remain one of the highest outside the Anglosphere for those geotechnical reasons.

But the MTA and its consultants, in this case AECOM, project $7.7 billion, not $3.4 billion. Why?

Worse project delivery

We’ve assumed the existing project delivery systems the MTA is familiar with. However, what doesn’t move forward moves backward, and the procurement strategy at the MTA is moving backward rapidly, for which the primary culprit is Janno Lieber, first in his role at MTA Capital Construction (now Construction and Development), and then in his role as MTA head, pushing alternative delivery methods, especially design-build and increasingly progressive design-build (unfortunately legalized in New York last year). Such methods add to the procurement costs and especially to the soft costs. Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 had an overall soft cost multiplier of about 1.5: the total cost including soft costs was 1.5 times the hard costs (Italy: 1.2-1.25 times). This proposal, in contrast, has a multiplier of 1.75: the hard costs are estimated at $4.4 billion, and the total costs are 75% higher, technically including rolling stock except rolling stock at current New York costs is $80 million.

Contingency

The soft costs include a federally mandated 40% contingency. The FTA mandates excessive contingencies – the norm in low-cost countries is 10-20%, and anything more than that is just wasted. The contingency figure varies by phase of design and decreases as it advances, but in the earliest phase it is 40%, and it’s in that phase that budgeting is done. However, 40% is only required over hard costs based on standardized cost categories (SCCs), and not over past ex post costs that incorporated contingency themselves. In effect, the estimation method the MTA and AECOM prefer bakes in a 40% overrun at each stage, letting project delivery get worse over time as the globalized system of procurement takes deeper roots in New York.

Overdesign and overbuilding

Based on our recommendations, the MTA shrank the station overages in Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. Phase 1 had station digs 100% longer than the platforms, based on standards that were both extravagant to the taxpayer and spartan to the end user – the extra space is not usable by passengers but instead for unnecessary break rooms, separated by department. By Phase 2, this was reduced to a 50% overage, and we hoped that proactive design around best practices would reduce this further.

Unfortunately, the overages are still substantial, 50% at St. Nicholas and 25% at the other two stations (Italy, Sweden, France, Germany, China: 3-20%). Moreover, the stations still have full-length mezzanines. This a longstanding New York tradition, going back to the 1930s with the opening of the IND lines starting with the A on Eighth Avenue in 1933. And like all other New York subway building traditions that conflict with how things are done in more advanced, non-English speaking countries, it belongs in the ashbin of history. Mined stations’ costs are sensitive to dig volume, and there is little need for such additional circulation space, for passenger comfort or fire safety. Mezzanines are essentially free if the stations are built cut-and-cover, in which case they are used for back-of-the-house space in advanced countries, but not if the stations are mined, in which case the best place for break rooms is under stairs and escalators.

Moreover, as we will explain soon at the Effective Transit Alliance, mined stations and bored tunnel require a minimum spacing from the street and from other tunnels – but the proposal includes much more space than necessary, forcing the stations to be deeper, more expensive, and less convenient as it takes a full five minutes to transfer between platforms or to get from the platform to the street. It’s possible to ge even shallower with shoring techniques used in China to reduce tunnel and station depth in complex urban undergrounds.

Proactive and reactive cost control

When the MTA announced cost savings and station size shrinkage in Phase 2, we were excited. But on hindsight, costs in effect fell from $7 billion to $7 billion. The savings were entirely reactive, designed to limit further cost overruns, and are not proactively incorporated into further projects.

No doubt, if a $7.7 billion project is approved against any honest benefit-cost analysis (which is not required in American law), then shrinkage in station footprint and reduction in mezzanine length will be found to be saving money in 2032, and the successor of Lieber, hired from the same pipeline of people whose takes on other countries are “I had a kid who did a semester abroad in Stockholm,” will be proud of reducing costs from $7.7 billion to $7.7 billion.

The path forward must instead incorporate cost savings proactively. There’s a way of building subway stations cost-effectively, and instead of quarter-measures, the MTA should adopt it; we have blueprints from a growing selection of examples, all in places that have avoided the destruction of subway building capacity infecting the entire English-dominant world in the last 25 years. The MTA can even hire people with direct transport official-to-transport official communication with peers at other agencies (for example, through COMET) and with the language skills to read documents produced in lower-cost countries, instead of people whose best skill is giving interviews to softball interviewers and talking about sports.

British Construction Costs and Centralization

There’s an ongoing conversation in the United Kingdom right about state capacity and centralization. The United Kingdom is notable for how centralized it is compared with peer first-world democracies of similar size. It also has weak state capacity on matters including infrastructure construction, which quite a lot of analysts and thinktanks assume is connected. Most recently, I’ve seen conversations on Bluesky in British media, talking about how the loss of state capacity in the UK in the last 45 years has really been about centralization of functions that local and county governments used to do and therefore the solution is to devolve some functions in England to counties or regions. Much of this discourse is by people I deeply respect, like the Financial Times’ Stephen Bush, pointing out sundry services Greater London ran before Margaret Thatcher’s anti-local government reforms in the 1980s. And yet none of this is relevant to infrastructure construction costs and the country’s inability to build more than a half-phase high-speed line at costs that would be high for a subway.

English centralization…

England has been very centralized for a long time, since the Early Middle Ages. It never really had anything like the German or Italian states, or even French provinces, not have its reforms to local government established anything like the French regions. Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have extensive devolution, but 85% of the population lives in England, and the overall character of the state is never driven by peripheral regions comprising 15% of it. Indeed, in the OECD, by one measure, the United Kingdom has the single largest share of taxes going to the central government, and the second largest share of spending decided by the central government behind New Zealand. The other reasonable measure of centralization would be to do the same but assign social security to the central government, since it invariably either is national or comes with extensive equalization payments; then a few small countries like Israel and Ireland end up more centralized, but none of the European countries of comparable population.

How to fund and what to devolve to local government in England has been a complex issue over the last few generations. Local taxation is weak, and there is nothing like the German system in which the federal government, which collects 95% of taxes, distributes the taxes to the states by formula to do with as they please. The succession of local council tax programs to fund such governments culminated in Margaret Thatcher’s community charge, better known as the poll tax, which was so unpopular it led to her overthrow in a palace coup; at the time, Labour was polling 20% ahead due to backlash against the proposal.

Thatcher herself worked to disempower regional governance that had been established in the two decades before she took office. She aimed to destroy three institutions that she believed were keeping Britain socialist and thus backward: unions, public-sector bureaucracies, and regional governments. On the last point, she led a reform that eliminated regional governance in the Metropolitan Counties, creating a unique situation in which the constituent municipalities of these counties are single-tier municipalities with no level of governance between them and the state. Anything else would permit powerful Labour regions to challenge state privatization and deunionization schemes. Indeed, reforms by the New Tories to undo this and devolve some functions to the Met Counties created elected mayors, and now the mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, has arisen as a powerful Labour politician who is mooted by many (including the Green Party) as a potential replacement for Keir Starmer in an intra-party palace coup.

…is not the reason for high costs

The truth is that while the United Kingdom is atypically centralized, at least in England, the exact same problems are seen across the Anglosphere, with roughly the same origin (except in the United States, whose problems have a different origin). British costs exploded in the 1990s, and Canadian and Australian costs followed suit in the 2000s and 2010s, imitating bad British practices. Australia and Canada both have some of the fiscally strongest states/provinces in the OECD, the exact opposite of the United Kingdom.

Across Europe, subtracting the United Kingdom, there isn’t an obvious relationship between centralization and poor state capacity. The Nordic countries are both rather devolved for small unitary states, managing health care and education subnationally. For example, in Finland it’s done in 21 health care regions, with ongoing debates over reducing the number of regions, but no attempt to eliminate devolution and make it a national system, in a country that after all has about the same population as Scotland. On the other hand, Italy is not much less centralized than the United Kingdom, and its infrastructure construction program is excellent, limited by money and uncertain growth prospects but perfectly capable of building a national high-speed rail network for less than half the budget of the 225 km High Speed 2. In democratic Europe, the strongest correlate of high costs is exposure to the United Kingdom and its way of doing things, with the Netherlands having the worst costs and most compromised infrastructure construction.

The privatization of state planning

At the Transit Costs Project, we are putting together a cost report on London, largely about Crossrail but also other recent urban rail expansion including the Docklands Light Railway and the Northern line extension. And what comes out of this history is that it’s not really about centralization. Rather, the United Kingdom invented what I called in the Stockholm report the globalized system, in which planning functions are privatized to large consultant firms while the role of the state is reduced to at most light oversight.

The explosion in costs in the 1990s, producing the Jubilee line extension at nearly four times the real per-km cost of the original Jubilee line, was part of this transition. It was easy to miss the first time we looked because the telltale signs of the globalized system, like design-build contracts, weren’t there yet. If anything, DLR was more privatized in its project delivery, and had reasonable costs until the Bank extension. And yet, delving more deeply, we (by which I mean Borners) found that beneath the surface it did have quite a lot of those negative features.

For example, while the Jubilee line extension was designed with in-house planning, it was understood that future projects would transition to more privatized planning. Thus, there was no expectation that the knowledge gained while building the extension would stick around, and at any rate, there was pressure to build like in Hong Kong, where pro-privatization British consultants cut their teeth in the 1980s and early 1990s. In effect, while the extension was designed in-house, it had all the features of a special purpose delivery vehicle (SPDV, or SPV), the preferred British and increasingly pan-Anglosphere way of delivering large projects: each project’s team is specific to the project itself and after completion the employees, drawn from a mix of private consultancies and public agencies, scatter and are not reassembled as a team for future projects. DLR was if anything the opposite: it was nominally private in its delivery but the same designers were involved throughout, moving between private employers and functions, so it was not de facto an SPDV, whereas the Jubilee line extension de facto was one.

Why do Brits blame centralization?

High costs in the United Kingdom cannot have much to do with the extent of devolution. Australia and Canada have adopted the same way of planning, after all. The British system in which big decisions can only be made by the minister and not by senior, let alone mid-level, civil servants, can be implemented regardless of scale, and Canadian provinces and Australian states are thus without exception not capable of building infrastructure for costs that were routine as late as 20 years ago.

But it can look like centralization, for all of the following reasons:

- The United Kingdom really does have issues with overcentralization and underempowerment of regional governments, though the latter is being fixed to some extent, at least for the Met Counties. It is natural to see two governance problems that cooccur and assume they’re related.

- The origin of the British cost explosion is, ideologically, the same process that also disempowered regional governments. It took some work to figure out the exact process, which was not at all the same as the conversion of the Met Counties to single-tier authorities. Indeed, in Canada the disempowerment of local or regional authorities never happened, but the transition to privatized planning with political rather than civil service oversight did happen, with large design-build contracts with more consultant involvement.

- The implementation of centralization in the United Kingdom has relied on ministerial approvals, and those genuinely bottleneck the state. A better system of centralization, such as in Italy, relies on trust in the civil service. But a prime minister whose favorite television show was Yes, Minister would never have produced such a system.

But that it may be reasonable for a Brit who doesn’t look too closely at how Canada and Australia fail in parallel ways to assume that it’s about centralization does not mean that it is in fact about centralization. Centralized states that don’t speak English routinely build infrastructure efficiently and highly devolved ones that do are incapable of relieving the most important bottlenecks in their city centers.

Fare Practices

Here’s a table of urban public transport fares for various cities, covering the United States, Canada, parts of Europe, Turkey, and Japan. Included are single fares, multi-ride discounts, day passes, weeklies, and monthlies, with the last three shown with their ratios to single fares. As far as possible we’ve tried doing fares as of 2026, but it’s possible a few numbers are not updated and depict 2025 figures.

The thing to note is that in Continental Europe, there are steeply discounted monthlies – only two cities in the table charge for a monthly more than for 30 single-trips (Paris at 35.5, Bari at 35). Most Italian cities cluster around 20, and Barcelona, Lisbon, and especially Porto are even lower. Berlin used to have a multiplier of 32 before the 9€ monthly and the subsequent Deutschlandticket but the current multiplier is 15.75 within the city. Stockholm has a monthly multiplier of 24.7. Prague’s multiplier is 12.

Japanese monthly fares are strange by Western standards, in the sense that they are station-to-station, with subsegments allowed but no trips outside the segment; subject to this constraint the multiplier is 30-40, with small additional discount for buying 3-6 months in advance, but the unrestricted monthly fare is very high. London and Istanbul functionally do not have monthlies, in the sense that the multiplier is so high (78.5 Istanbul-wide, and it’s not truly unlimited but is capped at 180 trips/month) that except for trips within Central London it might as well not exist.

American and Canadian monthly fares are usually higher than in Continental Western Europe, with multipliers in the 30s. New York’s multiplier was especially high, about 46, and the MTA has just abolished the monthly fare entirely and phased out the MetroCard (as of the new year, starting in two hours), making people use the weekly cap with OMNY instead, which has a multiplier of 11.7 and, over a 30-day month, forces a monthly multiplier of 50. Toronto has a very high monthly multiplier as well, 46.6. This is bad practice: a high monthly discount functions as a technologically simple off-peak discount (indeed, London pairs its stingy monthly discount with a substantial off-peak discount), and OMNY itself is buggy to the point that fare inspectors on the buses can’t tell if someone has actually paid except by looking at debit card statements, which do not show one as having paid if one has a valid transfer or has reached the weekly cap (and not tapping in this case is still illegal fare dodging in New York law).

The practice of the cap, increasingly popular in the US under London influence, is rare as well. London’s fare cap originates in its complex zone system: the Underground has nine zones with zone 1 only covering Central London so that passengers taking multiple trips per day can expect to take trips across different zones that they may not be familiar with; there isn’t fare integration, but rather there’s a special surcharge on some commuter train trips and a discount on buses; peak and off-peak fares are different. Thus, the calculation for the passenger of whether to buy tickets one at a time or get a pass is difficult, so Oyster does this calculation automatically to give the most advantageous fare. In a Continental city where fares are either flat regionwide or have zones with limited granularity (often the entire metro is in the innermost zone) and monthly discounts are steep, the calculation is simple: an even semi-regular rider should always get a monthly.

American and Canadian cities typically have flat fares or a simple zone system, good fare integration between buses and the subway or light rail, and commuter rail that’s functionally unusable for urban trips rather than resembling the subway with a $2 surcharge. The use case of London does not apply to such cities. New York should not have a fare cap, but a heavily surcharged single trip, perhaps $5, and an attractive flat monthly fare, perhaps $130. This system ensures passengers are incentivized to pay and there is little opportunistic fare dodging as the user has already prepaid for the entire month, so it pairs well with proof-of-payment fare collection, common in many of the European examples (though metro systems outside Germany and its immediate vicinity do have faregates).

The overall level of the fare is determined by the willingness of the government at various levels to subsidize public transport; the table can be used to compare these at PPP rates as well. However, the distribution of fares across different products and distances is not a matter of subsidy but a matter of good and bad industry practices, and the best practice for simple fare collection is to offer a prepaid monthly at a heavy discount compared with the single ride.

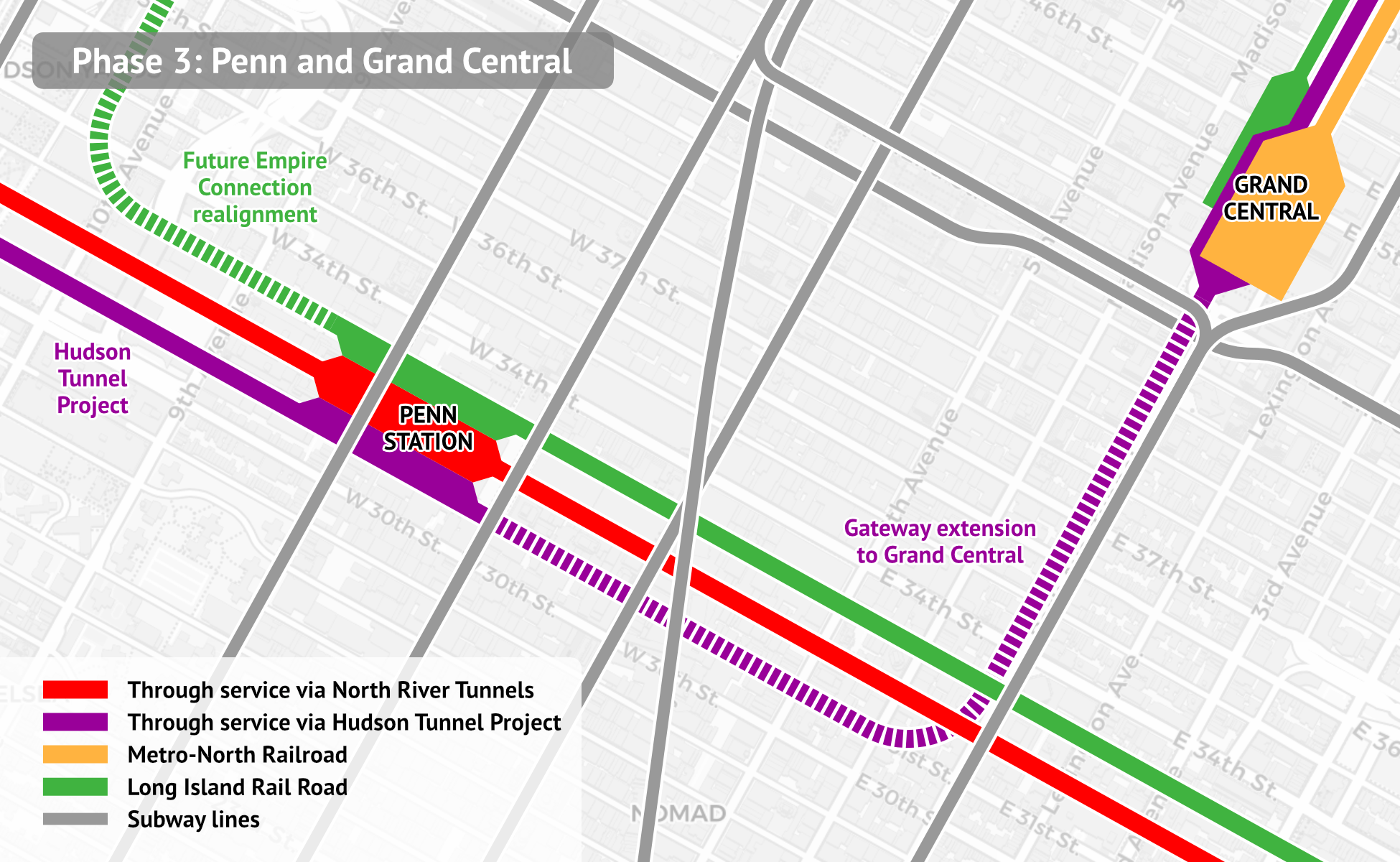

Quick Note: The Importance of Penn Station Access West to Through-Running

A video by the Joint Transit Association talks at length about through-running in New York – which lines are easier and which are harder, what some of the tradeoffs are, what sequencing works best with ongoing infrastructure plans starting with the Gateway tunnel. It’s a good video and I recommend watching – and not just because it gets a lot of its ideas from ETA reports but also because of its own analysis and own points (about, for example, Mott Haven Junction) – but it has one miss that I’d like to highlight: it neglects Penn Station Access West, the proposal to connect the Hudson Line to Penn Station via the Empire Connection.

The issue is that without the realignment, too many trains would be going into Grand Central – all preexisting Metro-North service minus trains diverted to Penn Station Access. We expect all this through-running infrastructure to add to peak demand substantially. Today it fills about 50 peak trains per hour, which a four-track trunk line would struggle with (Metro-North runs trains three-and-one at the peak). Even with diversion of 6-10 trains to Penn Station Access, the extra demand would saturate the line. Penn Station Access West is important in reducing this capacity crunch.

The realignment is both important and cheap. The Empire Connection exists and the tunnel has room for two tracks; it needs a short realignment to reach the right part of Penn Station – the high-numbered northern tracks as in the image, where today there is a single-track link from the Connection proper to the low-numbered tracks – but that realignment is much cheaper than a full through-tunnel such as between Penn Station and Grand Central or the various lines to Lower Manhattan mooted for longer-term plans.

The total capacity produced should be every train that doesn’t have to go to Grand Central. It’s hard to exactly say what the split should be – there should be a minimum of a train every 10 minutes to each destination, if only to serve the inner stations that are (or would be infill) on the lower Hudson Line or the Empire Connection before the two routes meet at Spuyten Duyvil. Beyond that it’s a matter of measuring demand and seeing what the limit of timed connections are; ideally there should be 12 peak trains per hour on Penn Station Access West and only 6 on the preexisting route, up from 14 total on the Hudson Line today due to service improvements brought by through-running and related upgrades. This is necessary to create the capacity to run more service on the other lines – today the Harlem Line peaks at 16 trains per hour and the New Haven Line at 20, but these upgrades would create a lot more demand and my assumption in sketching through-running tunnels is that the Harlem Line would need 24 and the New Haven Line would need 18 to Grand Central and 6 on Penn Station Access.

It’s not the Baumol Effect

The Baumol effect is an observation that wages in an economy rise based on its average productivity, and therefore the wages also rise in sectors with low or no productivity growth, increasing their real costs. The classical example is that it takes the same number of people to play an opera today as in the 19th century, but wages have to be competitive with the 21st-century economy, and therefore opera tickets cost in real terms more than they did in the 19th century. People from time to time invoke this effect to explain rising infrastructure construction costs in the United States, relating it to a broader cost disease affecting health care and education. But it’s not really a correct explanation for what’s going on at global scale. High American construction costs are not downstream of high incomes, but rather of poor governance leading to low labor efficiency, poor procurement practices, nonstandard systems, and overbuilding.

At global scale, there is no significant correlation between GDP per capita and tunneling construction costs. There’s a significant but weak correlation between GDP per capita and metro construction costs, but it comes from the fact that developing countries like India build mostly elevated systems. Adjusted for the ratio between subway and elevated cost, which is about 2 in both India and China, the correlation is reduced to insignificance.

There is extensive temporal correlation between GDP per capita and costs, in the sense that the US, UK, and France were all capable of tunneling for around $40 million/km in today’s prices in the early 1900s, and aren’t capable of doing so today. But then countries with the GDP per capita of early-1900s America, like India, build subways for maybe $400 million/km. The techniques used in the early 1900s were labor-intensive, with workers digging up streets by hand. These techniques are not used today in low-income countries, which instead use capital-intensive techniques learned from Western countries, Japan, or increasingly China, and which rarely have the mass industrial working class that characterized rich cities around 1900. That is not Baumol; that is a transition to capital-intensive techniques that are then applied where it’s inappropriate.

Nor has there been an explosion of costs since the 1970s globally. The US has gone from high to very high costs, and the UK from medium to very high ones. But German construction costs are barely higher now than then. Italian ones have if anything fallen a bit, due to anti-corruption laws in the 1990s. If anything, Germany is seeing an increase in construction costs now, with rather high NBS construction costs even without tunneling, at a time in which economic growth is weak. The weak economic growth here – Germany’s GDP per capita has been essentially constant since 2019 – combined with fast economic growth in the United States means that German elites are starting to imitate American procurement practices, with Deutsche Bahn starting to use previously unheard of design-build contracts and public-private partnerships, with the attendant costs.

In the UK, similarly, high costs interact with weak growth, in that weak growth leads to cancellation of infrastructure projects like High Speed 2 north of Birmingham, which cancellation then leads to orphaned designs. There’s been growing discourse in the UK about the problem of feast-or-famine projects, with rail electrification proceeding in waves rather than at a constant rate as at Continental European comparanda like Italy. Italy is hardly posting Polish economic growth rates, but in the UK the origin of the feast-or-famine problem is in the cycle of top-down infrastructure plans and cancellations.

In truth, while the US has had higher economic growth than nearly all of Western Europe since 2019, GDP per hour remains barely above the weighted average of the Germanic-majority Continental countries and France. This is not why the US is expensive; poor project delivery is.

New York Isn’t Special

A week ago, we published a short note on driver-only metro trains, known in New York as one-person train operation or OPTO. New York is nearly unique globally in running metro trains with both a driver and a conductor, and from time to time reformers have suggested switching to OPTO, so far only succeeding in edge cases such as a few short off-peak trains. A bill passed the state legislature banning OPTO nearly unanimously, but the governor has so far neither signed nor vetoed it. The New York Times covered our report rather favorably, and the usual suspects, in this case union leadership, are pissed. Transportation Workers Union head John Samuelsen made the usual argument, but highlighted how special New York is.

“Academics think working people are stupid,” [Samuelsen] said. “They can make data lie for them. They conducted a study of subway systems worldwide. But there’s no subway system in the world like the NYC subway system.”

Our report was short and didn’t go into all the ways New York isn’t special, so let me elaborate here:

- On pre-corona numbers, New York’s urban rail network ranked 12th in the world in ridership, and that’s with a lot of London commuter rail ridership excluded, including which would likely put London ahead and New York 13th.

- New York was among the first cities in the world to open its subway – but London, Budapest, Chicago (dating from the electrification and opening of the Loop in 1897), Boston, Paris, and Berlin all opened earlier.

- New York has some tight curves on its tracks, but the minimum curve radius on Paris Métro Line 1, 40 meters, is comparable to the New York City Subway’s.

- The trains on the New York City Subway are atypically long for a metro system, at 151 meters on most of the A division and 183 on most of the B division, but trains on some metro systems are even longer (Tokyo has some 200 m trains, Shanghai 180 m trains) and so are trains on commuter rail systems like the RER (204 m on the B, 220 m on the A), Munich S-Bahn (201 m), and Elizabeth line (205 m, extendable to 240).

- New York has crowded trains at rush hour, with pre-Second Avenue Subway trains peaking at 4 standees per square meter, but London peaks at 5/m^2 and trains in Tokyo and the bigger Chinese cities at more than that. Overall ridership, irrespective of crowding, peaked around 30,000 passengers per direction per hour on the 4 and 5 trains in New York, compared with 55,000 on the RER A.

New York is not special, not in 2025, when it’s one of many megacities with large subway systems. It’s just solipsistic, run by managers and labor leaders who are used to denigrating cities that are superior to New York in every way they run their metro systems as mere villages unworthy of their attention. Both groups are overpaid: management is hired from pipelines that expect master-of-the-universe pay and think Sweden is a lower-wage society, and labor faces such hurdles with the seniority system that new hires get bad shifts and to get enough workers New York City Transit has had to pay $85,000 at start, compared with, in PPP terms, around $63,000 in Munich after recent negotiations. The incentive in New York should be to automate aggressively, and look for ways to increase worker churn and not to turn people who earn 2050s wages for 1950s productivity be a veto point to anything.

High Speed Rail-Airport Links

As somewhat of a followup to my last post on how successful high-speed rail isn’t really made for tourists, I’d like to talk about the issue of air-rail links. Those are beloved by both foreign tourists and domestic residents using them to travel abroad, and American high-speed rail planning has on occasion tried focusing on them. This has always been awkward for both environmental and ridership goals. Such links are not inherently bad, but they are often overrated in planning, especially at the level of public advocacy and shadow planning agencies, which reproduce the biases of frequent fliers.

Skipping the airports in rich Asia

The Shinkansen does not serve Narita. There were plans for it to do so but they have not been implemented. Such service would require a dedicated line, since the Shinkansen is on a different gauge from the classical JR network and the standard-gauge link between the city and the airport is owned by private railway Keisei, and Narita itself is not important enough to drive such a line, not at the urban tunneling construction costs of Japan.

But the same lack of service to airports is seen in the two most Shinkansen-like systems outside Japan, Korea and especially Taiwan. The airport is not in Taipei but in Taoyuan, and is connected to the city by an express commuter train, the Taoyuan Airport MRT, but the Taiwan High-Speed Rail system does not serve it, instead having a different Taoyuan station on the Airport MRT. Even in Korea, which uses standard gauge and runs KTX trains through on classical lines in the French style, there is no KTX service to Incheon or to Gimpo.

The issue in all three countries is that the role of the capital’s international airport is to connect passengers between the capital region and the rest of the world. Tourists visiting the capital don’t need a train to secondary cities; in South Korea, last year, 66% of tourism by spending was in Seoul, and in Taiwan, 53% of tourism by occupied hotel nights was in Taipei, New Taipei, and Taoyuan (PDF-pp. 20-21 of the 2024 annual report). Domestic residents using the airport to travel abroad are a more serious use case, but far more residents of Busan or Kaohsiung are going to their respective country’s capital than abroad, and so the airport link is not a high priority for planning.

Serving the airports in Europe if they’re on the way

Three of the four busiest airports in the EU – CDG, Schiphol, and Frankfurt (the fourth is Barajas) – have high-speed rail links. However, in all cases, it’s because they’re on the way somewhere. CDG and Frankfurt are both on valuable bypass routes around the primary city with its terminal-only train stations, so they might as well be served. Schiphol is between Rotterdam and Amsterdam, but serving it involved high-cost tunneling, on a high-speed line, HSL Zuid, that has in retrospect been more a case of imitating the TGV than responding to Dutch intercity rail needs.

In all cases, the airport link is decidedly secondary to the network, and is not a major planning goal. There are intercity trains routed into Berlin-Brandenburg, but these are intended for long-distance regional use: the extensive rail tunneling to the new airport is for various regional express trains, with a 15-minute Takt to Berlin Hauptbahnhof and four hourly Takt trains to regional destinations starting next month and only one intercity train on a two-hour Takt between Berlin and Dresden. Munich has no ICE connection, and a proposal for one never got beyond the conceptual stage because the airport-city center connection was deemed a higher priority. It’s notable that even high-cost, high-prestige air-rail links here prioritize connections to city center, and not to the national network.

The awkward environmental politics of air-rail links

High-speed rail is justified on both economic and environmental grounds. But sometimes these different justifications end up conflicting. It’s noteworthy that in the United States, a common argument for high-speed rail in California and the Northeast has been that the airports are too clogged with short-haul regional flights and if high-speed trains replaced them then the gates and runway slots would be usable by long-haul flights. This argument is made at the same time as arguments about reducing greenhouse gas emissions – but long-haul flights contribute far more emissions than short-haul ones per unit of airport capacity consumed, airport capacity not particularly caring if you’re flying 700 km or 7,000.

It’s possible to ignore the environmental effects and just focus on the economic benefits; in Europe, the broad environmental movement is neutral or even hostile to high-speed rail, viewing it as inferior to running more night trains and regional trains. But then in Europe the economic-only planning for high-speed rail does not prioritize the air links, because they are fundamentally secondary. In a country like France, the demand for high-fare rail links to CDG is to the center of Paris, not Marseille.