Category: Construction Costs

The MTA Sticks to Its Oversize Stations

In our construction costs report, we highlighted the vast size of the station digs for Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 as one of the primary reasons for the project’s extreme costs. The project’s three new stations cost about three times as much as they should have, even keeping all other issues equal: 96th Street’s dig is about three times as long as necessary based on the trains’ length, and 72nd and 86th Street’s are about twice as long but the stations were mined rather than built cut-and-cover, raising their costs to match that of 96th each. In most comparable cases we’ve found, including Paris, Istanbul, Rome, Stockholm, and (to some extent) Berlin, station digs are barely longer than the minimum necessary for the train platform.

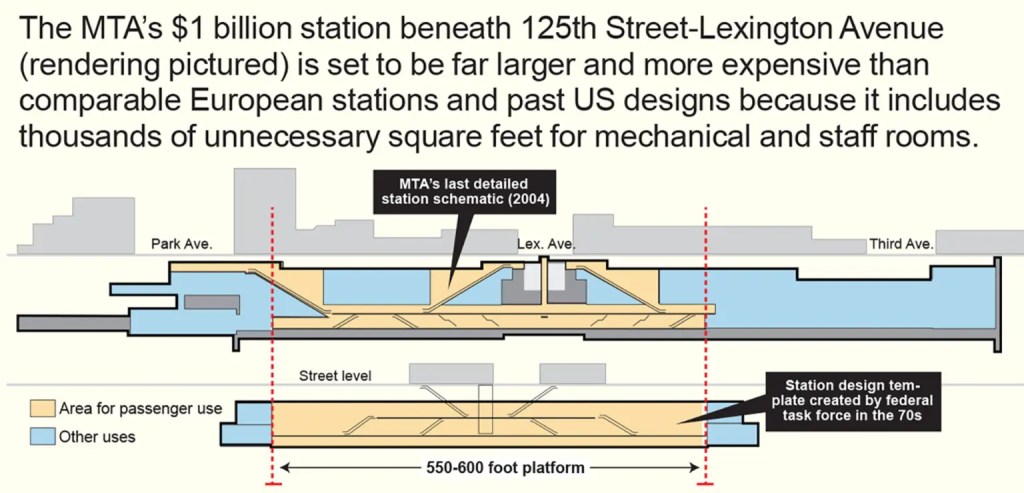

MTA Construction and Development has chosen to keep building oversize stations for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, a project that despite being for the most part easier than the already-open Phase 1, is projected to cost slightly more per kilometer. Nolan Hicks at the New York Post just published a profile diagram:

The enormous size of 125th Street Station is not going to be a grand civic space. As the diagram indicates, the length of the dig past the platforms will not be accessible to passengers. Instead, it will be used for staff and mechanical rooms. Each department wants its own dedicated space, and at no point has MTA leadership told them no.

Worse, this is the station that has to be mined, since it goes under the Lexington Avenue Line. A high-cost construction technique here is unavoidable, which means that the value of avoiding extra costs is higher than at a shallow cut-and-cover dig like those of 106th and 116th Streets. Hence, the $1 billion hard cost of a single station. This is an understandable cost for a commuter rail station mined under a city center, with four tracks and long trains; on a subway, even one with trains the length of those of the New York City Subway, it is not excusable.

When we researched the case report on Phase 1, one of the things we were told is that the reason for the large size of the stations is that within the MTA, New York City Transit is the prestige agency and gets to call the shots; Capital Construction, now Construction and Development, is smaller and lacks the power to tell NYCT no, and from NYCT’s perspective, giving each department its own break rooms is free money from outside. One of the potential solutions we considered was changing the organizational chart of the agency so that C&D would be grouped with general public works and infrastructure agencies and not with NYCT.

But now the head of the MTA is Janno Lieber, who came from C&D. He knows about our report. So does C&D head Jamie Torres-Springer. When one of Torres-Springer’s staffers said a year ago that of course Second Avenue Subway needs more circulation space than Citybanan in Stockholm, since it has higher ridership (in fact, in 2019 the ridership at each of the two Citybana stations, e.g. pp. 39 and 41, was higher than at each of the three Second Avenue Subway stations), the Stockholm reference wasn’t random. They no longer make that false claim. But they stick to the conclusion that is based on this and similar false claims – namely, that it’s normal to build underground urban rail stations with digs that are twice as long as the platform.

When I call for removing Lieber and Torres-Springer from their positions, publicly, and without a soft landing, this is what I mean. They waste money, and so far, they’ve been rewarded: Phase 2 has received a Full Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) from the United States Department of Transportation, giving federal imprimatur to the transparently overly expensive design. When they retire, their successors will get to see that incompetence and multi-billion dollar waste is rewarded, and will aim to imitate that. If, in contrast, the governor does the right thing and replaces Lieber and Torres-Springer with people who are not incurious hacks – people who don’t come from the usual milieu of political appointments in the United States but have a track record of success (which, in construction, means not hiring someone from an English-speaking country) – then the message will be the exact opposite: do a good job or else.

Boston Meetup and Consultants Supervising Consultants

The meetup was a lot less formal than expected; people who showed up included loyal blog readers (thank you for reading and showing up!), social media followers (same), and some people involved in politics or the industry. I don’t have any presentation to show – I talked a bit about the TransitMatters Regional Rail program and then people asked questions. Rather, I want to talk about something I’ve said on social media but not here, which I delivered a long rant about to the last people who stayed there.

The issue at hand is that the only way that seems to work to deliver complex infrastructure projects is with close in-house supervision. This is true even in places where the public-sector supervisors, frankly, suck – which they frequently do in the United States. It’s fine to outsource some capabilities to consultants, but if it happens, then the supervision must remain in the public sector, which requires hiring more in-house people, at competitive salaries.

Why?

The reason is that public-sector projects always involve some public-sector elements. This is true even in the emergent norm in the English-speaking world and in many other countries that take cues from it, in which not only is most work done by consultants, but also the consultants are usually supervised by other consultants. The remains of the public sector think they’re committed to light-touch supervision, but because they, by their own admission, don’t know how to do things themselves or even how to supervise consultants, they do a bad job at it.

The most dreaded request is “study everything.” It’s so easy to just add more scenarios, more possibilities, more caveats. It’s the bane of collaborative documents (ask me how I know). In the Northeast Corridor timetabling project I’m doing with Devin Wilkins, I could study everything and look at every possible scenario, with respect to electrification, which projects are undertaken, rolling stock performance profile, and so on. It would not be doable with just me and her in a year or so; I would need to hire a larger team and take several years, and probably break it down so that one person just does Boston, another just does Philadelphia, a third just does Washington and Baltimore, several do New York (by far the hardest case), and one (or more) assists me in stapling everything together. The result might be better than what we’re doing now, thanks to the greater detail; or it might be worse, due to slight inconsistencies between different people’s workflows, in which case a dedicated office manager would be needed to sort this out, at additional expense. But at least I’d study everything.

Because I’m doing this project for Marron and not for an American public-sector client, I can prune the search tree, and do it at relatively reasonable expense. That’s partly because I’m the lead, but also partly because I know what I’m doing, to an extent, and am not going to tell anyone “study everything” and then dismiss most scenarios after three months of no contact.

The behavior I’m contrasting myself with is, unfortunately, rife in the American public sector. And it’s the most common among exactly the set of very senior bureaucrats, often (not always) ones who are there by virtue of political appointment rather than the civil service process, who swear that consultants do things better than the public sector. There’s no real supervision, and no real narrowing of the process. This looks like an alternative to micromanagement, but is not, because the client at the end does say “no, not like this”; there’s a reason the consultants always feel the need to study everything rather than picking just a few alternatives and hoping the client trusts them to do it right.

It’s telling that the consultants and contractors we speak to don’t really seem happy with how they’re treated by the public-sector client in those situations. They’re happy when interfacing with other private actors, usually. I imagine that if I hired a larger team (which we don’t have the budget for) and gave each person a separate task, they’d be really happy to have come up with all those different scenarios for how to run trains in the Baltimore-Washington area, interfacing with other equally dedicated people doing other tasks of this size. When consultants are supervised by other consultants, only the top-level consultant interfaces with the remains of the civil service, hollowed out by hiring freezes, uncompetitive salaries, and political scourging; the others don’t and think things work really smoothly. This, I think, is why opaque design-build setups are so popular with the private consultants who are involved in them: by the time a country or region fully privatizes its supervision to a design-build consultant, its public sector has been hollowed so much that the consultants prefer to be supervised privately, even if the results are worse.

In contrast, the only way forward is a bigger civil service. This means hiring more people, in-house, and paying them on a par with what they would be earning in the private sector given their experience. As I said at the bar a few hours ago, I’m imagining someone whose CV is four years at the MTA, then five at a consultant, then four at the MBTA, and then six at a consultant; with these 19 years of experience, they could get hired at a senior engineer or project manager position, for which the market rate in Boston as I understand is in the high $100,000s. For some things, like commuter rail electrification, there are unlikely to be any suitable candidates from within the US, and so agencies would have to hire a European or Asian engineer.

With competitive salaries, people would move between different employers in the same industry, as is normal in American and European industries. They could move between public and private employers, because the wages and benefits should be similar. They’d pick up experience. An agency like the MBTA, with its five to six in-house design review engineers, could staff up appropriately to be able to supervise not just small projects like infill commuter rail station, which it built at reasonable cost on the Fairmount Line, but also large ones like the Green Line Extension and South Coast Rail, which it builds at outrageously high costs.

The MTA 20 Year Needs Assessment Reminds Us They Can’t Build

The much-anticipated 20 Year Needs Assessment was released 2.5 days ago. It’s embarrassingly bad, and the reason is that the MTA can’t build, and is run by people who even by Northeastern US standards – not just other metro areas but also New Jersey – can’t build and propose reforms that make it even harder to build.

I see people discuss the slate of expansion projects in the assessment – things like Empire Connection restoration, a subway under Utica, extensions of Second Avenue Subway, and various infill stations. On the surface of it, the list of expansion projects is decent; there are quibbles, but in theory it’s not a bad list. But in practice, it’s not intended seriously. The best way to describe this list is if the average poster on a crayon forum got free reins to design something on the fly and then an NGO with a large budget made it into a glossy presentation. The costs are insane, for example $2.5 billion for an elevated extension of the 3 to Spring Creek of about 1.5 km (good idea, horrific cost), and $15.9 billion for a 6.8 km Utica subway (see maps here); this is in 2027 dollars, but the inescapable conclusion here is that the MTA thinks that to build an elevated extension in East New York should cost almost as much as it did to build a subway in Manhattan, where it used the density and complexity of the terrain as an argument for why things cost as much as they did.

To make sure people don’t say “well, $16 billion is a lot but Utica is worth it,” the report also lowballs the benefits in some places. Utica is presented as having three alternatives: subway, BRT, and subway part of the way and BRT the rest of the way; the subway alternative has the lowest projected ridership of the three, estimated at 55,600 riders/weekday, not many more than ride the bus today, and fewer than ride the combination of all three buses in the area today (B46 on Utica, B44 on Nostrand, B41 on Flatbush). For comparison, where the M15 on First and Second Avenues had about 50,000 weekday trips before Second Avenue Subway opened, the two-way ridership at the three new stations plus the increase in ridership at 63rd Street was 160,000 on the eve of corona, and that’s over just a quarter of the route; the projection for the phase that opened is 200,000 (and is likely to be achieved if the system gets back to pre-corona ridership), and that for the entire route from Harlem to Lower Manhattan is 560,000. On a more reasonable estimate, based on bus ridership and gains from faster speeds and saving the subway transfer, Utica should get around twice the ridership of the buses and so should Nostrand (not included in the plan), on the order of 150,000 and 100,000 respectively.

Nothing there is truly designed to optimize how to improve in a place that can’t build. London can’t build either, even if its costs are a fraction of New York’s (which fraction seems to be falling since New York’s costs seem to be rising faster); to compensate, TfL has run some very good operations, squeezing 36 trains per hour out of some of its lines, and making plans to invest in signaling and route design to allow similar throughput levels on other lines. The 20 Year Needs Assessment mentions signaling, but doesn’t at all promise any higher throughput, and instead talks about state of good repair: if it fails to improve throughput much, there’s no paper trail that they ever promised more than mid-20s trains per hour; the L’s Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) signals permit 26 tph in theory but electrical capacity limits the line to 20, and the 7 still runs about 24 peak tph. London reacted to its inability to build by, in effect, operating so well that each line can do the work of 1.5 lines in New York; New York has little interest.

The things in there that the MTA does intend to build are slow in ways that cross the line from an embarrassment to an atrocity. There’s an ongoing investment plan in elevator accessibility on the subway. The assessment trumpets that “90% of ridership” will be at accessible stations in 2045, and 95% of stations (not weighted by ridership) will be accessible by 2055. Berlin has a two years older subway network than New York; here, 146 out of 175 stations have an elevator or ramp, for which the media has attacked the agency for its slow rollout of systemwide accessibility, after promises to retrofit the entire system by about this year were dashed.

The sheer hate of disabled people that drips from every MTA document about its accessibility installation is, frankly, disgusting, and makes a mockery of accessibility laws. Berlin has made stations accessible for about 2 million € apiece, and in Madrid the cost is about 10 million € (Madrid usually builds much more cheaply than Berlin, but first of all its side platforms and fare barriers mean it needs more elevators than Berlin, and second it builds more elevators than the minimum because at its low costs it can afford to do so). In New York, the costs nowadays start at $50 million and go up from there; the average for the current slate of stations is around $70 million.

And the reason for this inability to build is decisions made by current MTA leadership, on an ongoing basis. The norm in low- and medium-cost countries is that designs are made in-house, or by consultants who are directly supervised by in-house civil service engineers who have sufficient team size to make decisions. In New York, as in the rest of the US, the norms is that not only is design done with consultants, but also the consultants are supervised by another layer of consultants. The generalist leadership at the MTA doesn’t know enough to supervise them: the civil service is small and constantly bullied by the political appointees, and the political appointees have no background in planning or engineering and have little respect for experts who do. Thus, they tell the consultants “study everything” and give no guidance; the consultants dutifully study literally everything and can’t use their own expertise for how to prune the search tree, leading to very high design costs.

Procurement, likewise, is done on the principle that the MTA civil service can’t do anything. Thus, the political appointees build more and more layers of intermediaries. MTA head Janno Lieber takes credit for the design-build law from 2019, in which it’s legalized (and in some cases mandated) to have some merger of design and construction, but now there’s impetus to merge even more, in what is called progressive design-build (in short: New York’s definition of design-build is similar to what is used in Turkey and what we call des-bid-ign-build in our report – two contracts, but the design contract is incomplete and the build contract includes completing the design; progressive design-build means doing a single contract). Low- and medium-cost countries don’t do any of this, with the exception of Nordic examples, which have seen a sharp rise in costs from low to medium in conjunction with doing this.

And MTA leadership likes this. So do the contractors, since the civil service in New York is so enfeebled – scourged by the likes of Lieber, denied any flexibility to make decisions – that it can’t properly supervise design-bid-build projects (and still the transition to design-build is raising costs a bit). Layers of consultants, insulated from public scrutiny over why exactly the MTA can’t make its stations accessible or extend the subway, are exactly what incompetent political appointees (but I repeat myself) want.

Hence, the assessment. Other than the repulsively slow timeline on accessibility, this is not intended to be built. It’s not even intended as a “what if.” It’s barely even speculation. It’s kayfabe. It’s mimicry of a real plan. It’s a list of things that everyone agrees should be there plus a few things some planners wanted, mostly solidly, complete with numbers that say “oh well, we can’t, let’s move on.” And this will not end while current leadership stays there. They can’t build, and they don’t want to be able to build; this is the result.

High Speed 2 is (Partly) Canceled Due to High Costs

It’s not yet officially confirmed, but Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will formally announce that High Speed 2 will be paused north of Birmingham. All media reporting on this issue – BBC, Reuters, Sky, Telegraph – centers the issue of costs; the Telegraph just ran an op-ed supporting the curtailment on grounds of fiscal prudence.

I can’t tell you how the costs compare with the benefits, but the costs, as compared with other costs, really are extremely high. The Telegraph op-ed has a graph with how real costs have risen over time (other media reporting conflates cost overruns with inflation), which pegs current costs, with the leg to Manchester still in there, as ranging from about £85 billion to £112 billion in 2022 prices, for a full network of (I believe) 530 km. In PPP terms, this is $230-310 million/km, which is typical of subways in low-to-medium-cost countries (and somewhat less than half as much as a London Undeground extension). The total cost in 2022 terms of all high-speed lines opened to date in France and Germany combined is about the same as the low end of the range for High Speed 2.

I bring this up not to complain about high costs – I’ve done this in Britain many times – but to point out that costs matter. The ability of a country or city to build useful infrastructure really does depend on cost, and allowing costs to explode in order to buy off specific constituencies, out of poor engineering, or out of indifference to good project delivery practices means less stuff can be built.

Britain, unfortunately, has done all three. High Speed 2 is full of scope creep designed to buy off groups – namely, there is a lot of gratuious tunneling in the London-Birmingham first phase, the one that isn’t being scrapped. The terrain is flat by French or German standards, but the people living in the rural areas northwest of London are wealthy and NIMBY and complained and so they got their tunnels, which at this point are so advanced in construction that it’s not possible to descope them.

Then there are questionable engineering decisions, like the truly massive urban stations. The line was planned with a massive addition to Euston Station, which has since been descoped (I blogged it when it was still uncertain, but it was later confirmed); the current plan seems to be to dump passengers at Old Oak Common, at an Elizabeth line station somewhat outside Central London. It’s possible to connect to Euston with some very good operational discipline, but that requires imitating some specific Shinkansen operations that aren’t used anywhere in Europe, because the surplus of tracks at the Parisian terminals is so great it’s not needed there, and nowhere else in Europe is there such high single-city ridership.

And then there is poor project delivery, and here, the Tories themselves are partly to blame. They love the privatization of the state to massive consultancies. As I keep saying about the history of London Underground construction costs, the history doesn’t prove in any way that it’s Margaret Thatcher’s fault, but it sure is consistent with that hypothesis – costs were rising even before she came to power, but the real explosion happened between the 1970s (with the opening of the Jubilee line at 2022 PPP $172 million/km) and the 1990s (with the opening of the Jubilee line extension at $570 million/km).

Our Webinar, and Penn Reconstruction

Our webinar about the train station 3D model went off successfully. I was on video for a little more than two hours, Michael a little less; the recording is on YouTube, and I can upload the auto-captioning if people are okay with some truly bad subtitles.

I might even do more webinars as a substitute for Twitch streams, just because Zoom samples video at similar quality to Twitch for my purposes but at far smaller file size; every time I upload a Zoom video I’m reminded that it takes half an hour to upload a two-hour video whereas on Twitch it is two hours when I’m in Germany. (Internet service in other countries I visit is much better.)

The questions, as expected, were mostly not about the 3D model, but about through-running and Penn Station in general. Joe Clift was asking a bunch of questions about the Hudson Tunnel Project (HTP) and its own issues, and he and others were asking about commuter rail frequency. A lot of what we talked about is a preview of a long proposal, currently 19,000, by the Effective Transit Alliance; the short version can be found here. For example, I briefly mentioned on video that Penn Expansion, the plan to demolish a Manhattan block south of Penn Station to add more tracks at a cost of $17 billion, provides no benefits whatsoever, even if it doesn’t incorporate through-running. The explanation is that the required capacity can be accommodated on four to five tracks with best American practices for train turnaround times and with average non-US practices, 10 minutes to turn; the LIRR and New Jersey Transit think they need 18-22 minutes.

There weren’t questions about Penn Reconstruction, the separate (and much better) $7 billion plan to rebuild the station in place. The plan is not bad – it includes extra staircases and escalators, extra space on the lower concourse, and extra exits. But Reinvent Albany just found an agreement between the various users of Penn Station for how to do Penn Reconstruction, and it enshrines some really bad practices: heavy use of consultants, and a choice of one of four project delivery methods all of which involve privatization of the state; state-built construction is not on the menu.

In light of that, it may make sense to delay Penn Reconstruction. The plan as it is locks in bad procurement practices, which mean the costs are necessarily going to be a multiple of what they could be. It’s better to expand in-house construction capacity for the HTP and then deploy it for other projects as the agency gains expertise; France is doing this with Grand Paris Express, using its delivery vehicle Société du Grand Paris as the agency for building RER systems in secondary French cities, rather than letting the accumulated state capacity dissipate when Grand Paris Express is done.

This is separate from the issue of what to even do about Penn Station – Reconstruction in effect snipes all the reimaginings, not just ours but also ones that got more established traction like Vishaan Chakrabarti’s. But even then it’s not necessarily a bad project; it just really isn’t worth $7 billion, and the agreement makes it clear that it is possible to do better if the agencies in question learn what good procurement practices are (which I doubt – the MTA is very bought in to design-build failure).

Mineta Shows How not to Reduce Construction Costs

There’s a short proposal just released by Joshua Schank and Emma Huang at the Mineta Transportation Institute, talking about construction costs. It’s anchored in the experience of Los Angeles more than anything, and is a good example of what not to do. The connections the authors have with LA Metro make me less confident that Los Angeles is serious about reforming in order to be able to build cost-effective infrastructure. There are three points made in the proposal, of which two would make things worse and one would be at best neutral.

What’s in the proposal?

The report links to the various studies done about construction cost comparison, including ours but also Eno’s and Berkeley Law’s. It does so briefly, and then says,

Often overlooked are the inefficiencies and shortcomings inherent in the transportation planning process, which extend far beyond cost, to the quality of the projects, outcomes for the public, and benefits to the region. Rather than propose sweeping, but politically unfeasible, policy changes to address these issues, we focused on more attainable steps that agencies can take right now to improve the process and get to better outcomes.

Mineta’s more attainable steps, in lieu of what we say about project delivery and standardization, are threefold:

- Promise Outcomes, not Projects: instead of promising a concrete piece of infrastructure like a subway, agencies should promise abstract things: “mode-agnostic mobility solutions that ‘carried x riders per day’ or ‘reduced emissions by x%’ or ‘reduced travel time by x minutes,'” which may be “exclusive bus lanes, express bus services, or microtransit.”

- Separate the Planning and Environmental Processes: American agencies today treat the environmental impact statement (EIS) process as the locus of planning, and instead should separate the two out. The planning process should come first; one positive example is the privatized planning of the Sepulveda corridor in Los Angeles.

- Integrate Planning, Construction, and Operations Up Front: different groups handling operations and construction are siloed in the US today, and this should change. There are different ways to do it, but the report spends the longest time on a proposal to offload more responsibilities to public-private partnerships (PPPs or P3s), which should be given long-term contracts for both construction and maintenance.

Point #2 is not really meaningful either way, and the Sepulveda corridor planning is not at all a good example to learn from. The other two points have been to various extents been done before, always with negative consequences.

What’s the problem with the proposal?

Focusing on outcomes rather than projects is called functional procurement in the Nordic countries. The idea is that the state should not be telling contractors what to do, but only set broad goals, like “we need 15,000 passengers per hour capacity.” It’s a recent reform, along many others aiming to increase the role of the private sector in planning.

In truth, public transport is a complex enough system that it’s not enough to say “we need X capacity” or “we need Y speed.” Railways have far too many moving parts, to the point that there’s no alternative to just procuring a system. Too many other factors depend on whether it is a full metro, a tramway, a tram-train (in practice how American light rail systems function), a subway-surface line, or a commuter train. In practice, functional procurement in Sweden hasn’t brought in any change.

In the case of Sepulveda, LA Metro did send some of the high-level P3 proposals to Eric and me. What struck me was that the vendors were proposing completely different technologies. This is irresponsible planning: Sepulveda has a lot of different options for what to do to the north (on the San Fernando Valley side) and south (past LAX), and not all of them work with new technology. For example, one option must be running it through to the Green Line on the 105, but this is only viable if it’s the same light rail technology.

The alternative of microtransit is even worse. It does not work at scale; over a decade of promises by taxi companies that act like tech companies have failed to reduce the cost structure below that of traditional taxis. However, it does open the door for politicians who think they’re being innovative to bring in inefficient non-solutions that are getting a lot of hype. The report brings the example of a New York politician who was taking credit for (small) increases in subway frequency; well, many more politicians spent the 2010s saying that San Francisco’s biggest nonprofit, Uber, was the future of transportation.

The point recommending P3s for their integration of operations and infrastructure is even worse. The privatization of state planning has been an ongoing process in certain parts of the world – it’s universal in the English-speaking world and advancing in the Nordic countries. The outcomes are always the same: infrastructure construction gets worse.

The top-down Swedish state planning of the third quarter of the 20th century built around 104 km of the T-bana, of which 57 are underground, for $3.6 billion in 2022 prices. The present process, negotiated over decades with people who don’t like an obtrusive state and are inspired by British privatization, is building about 19 underground km, for $4.5 billion. This mirrors real increases in absolute costs (not just overruns) throughout Scandinavia. The costs of Sweden in the 1940s-70s were atypically low, but there’s no need for them to have risen so much since then; German costs have been fairly flat over this period, Italian costs rose to the 1970s-80s due to corruption and have since fallen, Spanish costs are still very low.

As we note in the Swedish case report, Nordic planners take it for granted that privatization is good, and ding Germany for not doing as much of it as the UK; of these two countries, one can build and one can’t, and the one that can is unfortunately not the one getting accolades. The United Kingdom, was building subways for the same costs as Germany and Italy in the 1960s and 70s, but its real costs have since grown by a factor of almost four. I can’t say for certain that it’s about Britain’s love affair with P3s, but the fact that the places that use P3s the most are the worst at building infrastructure should make people more critical of the process.

Britain Remade’s Report on Construction Costs

The group Britain Remade dropped a report criticizing Britain for its high infrastructure construction costs three days ago. I recommend everyone read Sam Dumitriu and Ben Hopkinson’s post on the subject. Sam and Ben constructed their own database. Their metro tunneling costs mostly (but not exclusively) come from our database but include more detail such as the construction method used; in addition, they have a list of tram projects, another list of highway projects, and a section about rail electrification. Over the last three days, this report has generated a huge amount of discussion on Twitter about this, with appearances in mainstream media. People have asked me for my take, so here it is. It’s a good report, and the recommendations are solid, but I think it would benefit from looking at historical costs in both the US and UK. In particular, while the report is good, the way it’s portrayed in the media misses a lot.

What’s in the report

Sam and Ben’s post talks about different issues, affecting different aspects of the UK, all leading to high costs:

NIMBYism

The report brings up examples of NIMBYs slowing down construction and making it more expensive, and quotes Brooks-Liscow on American highway cost growth in the 1960s and 70s. This is what has been quoted in the media the most: Financial Times call it the “NIMBY tax,” and the Telegraph spends more time on this than on the other issues detailed below.

The NIMBYs have both legal and political power. The legal power comes from American-style growth in red tape; the Telegraph article brings up that the planning application for a highway tunnel under the Thames Estuary is 63,000 pages long and has so far cost 250 million £ in planning preparations alone (the entire scheme is 9 billion £ for 23 km of which only 4.3 are in tunnel). The political power is less mentioned in the report, but remains important as well – High Speed 2 has a lot of gratuitous tunneling due to the political power of the people living along the route in the Home Counties.

Start-and-stop construction

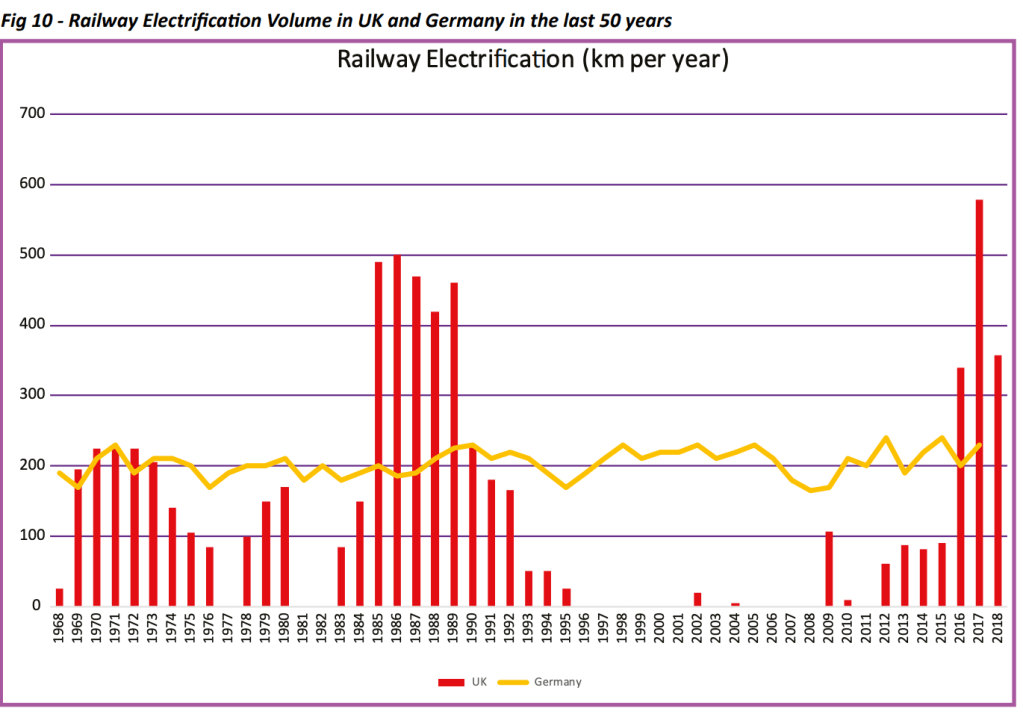

British rail electrification costs are noticeably higher than Continental European ones. The report points out that construction is not contiguous but is rather done in starts and stops, leading to worse outcomes:

Lack of standardization

Sam and Ben bring up the point Bent Flyvbjerg makes about modularization and standardization. This is the least-developed point in the report, to the point that I’m not sure this is a real problem in the United Kingdom. It is a serious problem in the United States, but while both American and British costs of infrastructure construction are very high, not every American problem is present in the UK – for example, none of the British consultants we’ve spoken to has ever complained about labor in the UK, even though enoguh of them are ideologically hostile to unions that they’d mention it if it were as bad as in the US.

What’s not in the report?

There are some gaps in the analysis, which I think compromise its quality. The analysis itself is correct and mentions serious problems, but would benefit from including more things, I believe.

Historical costs

The construction costs as presented are a snapshot in time: in the 21st century, British (and Canadian, and American) costs have been very high compared with Continental Europe. There are no trends over time, all of which point to some additional issues. In contrast, I urge people to go to my post from the beginning of the year and follow links. The biggest missing numbers are from London in the 1960s and 70s: the Victoria and Jubilee lines were not at all atypically expensive for European subway tunnels at the time – at the time, metro construction costs in London, Italian cities, and German cities were about the same. Since then, Germany has inched up slightly, Italy has gone down due to the anti-corruption laws passed in the 1990s, and the United Kingdom has nearly quadrupled its construction costs over the Jubilee, which was already noticeably higher than the Victoria.

The upshot is that whatever happened that made Britain incapable of building happened between the 1970s and the 1990s. The construction cost increase since the 1990s has been real but small: the Jubilee line extension, built 1993-9, cost 218.7 million £/km, or 387 million £/km in 2022 prices; the Northern line extension, built 2015-21, cost 375 million £/km, or 431 million £/km in 2022 prices. The Jubilee extension is only 80% underground, but has four Thames crossings; overall, I think it and the Northern extension are of similar complexity. It’s a real increase over those 22 years; but the previous 20 years, since the original Jubilee line (built 1971-9), saw an increase to 387 million £/km from 117 million £/km.

The issue of soft costs

Britain has a soft costs crisis. Marco Chitti points out how design costs that amount to 5-10% of the hard costs in Italy (and France, and Spain) are a much larger proportion of the overall budget in English-speaking countries, with some recent projects clocking in at 50%. In the American discourse, this is mocked as “consultants supervising consultants.” Every time something is outsourced, there’s additional friction in contracting – and the extent of outsourcing to private consultants is rapidly growing in the Anglosphere.

On Twitter, some people were asking if construction costs are also high in other Anglo countries, like Australia and New Zealand; the answer is that they are, but their cost growth is more recent, as if they used to be good but then learned bad practices from the metropole. In Canada, we have enough cost history to say that this was the case with some certainty: as costs in Toronto crept up in the 1990s, the TTC switched to design-build, supposed inspired by the Madrid experience – but Spain does not use design-build and sticks to traditional design-bid-build; subsequently, Toronto’s costs exploded, going, in 2022 prices, from C$305 million/km for the Sheppard line to C$1.2 billion/km for the Ontario Line. Every cost increase, Canada responds with further privatization; the Ontario Line is a PPP. And this is seen the most clearly in the soft cost multiplier, and in the rise in complaints among civil servants, contractors, and consultants about contracting red tape.

Britain Remade’s political recommendations

Britain Remade seems anchored not in London but in secondary cities, judging by the infrastructure projects it talks most about. One of its political recommendations is,

Britain is one of the most centralised countries in the world. Too often, Westminster prioritises investments in long-distance intercity rail such as HS2 or the Northern Powerhouse Rail when they would be better off focusing on cutting down commuting times. Local leaders understand local priorities better than national politicians who spend most of their time in Westminster. If we really devolved power and gave mayors real powers over spending, we’d get the right sort of transport more often.

Britain Remade is campaigning for better local transport. We want to take power from Westminster and give it to local leaders who know better. But, we also want to make sure transport investment stretches further. That’s why we are calling for the government to copy what other countries do to bring costs down, deliver projects on time, and build more.

https://www.britainremade.co.uk/building_better_local_transport

Devolution to the Metropolitan counties – those covering Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, and Newcastle – has been on the agenda in the UK for some time now. This reform is intended to give regions more power over spending, inspired by the success of devolution to London, where Transport for London has good operating practices and plenty of in-house capacity. More internationally-minded Brits (that is, to say, European-minded – there’s little learning from elsewhere except when consultants treat Singapore and Hong Kong as mirrors of their own bad ideas) will even point out the extensive regional empowerment in the Nordic countries: Swedish counties have a lot of spending power, and it’s possible to get all stakeholders in the room together in a county.

And yet, the United States is highly decentralized too, and has extreme construction costs. Conversely, Britain knew how to build infrastructure in the 1960s and 70s, under a centralized administrative state. Devolution to the Metropolitan counties will likely lead to good results in general, but not in infrastructure construction costs.

The media discourse

The report raises some interesting points. The start-and-stop nature of British electrification is a serious problem. To this, I’ll add that in Denmark, electrification costs are higher than in peer Northern European countries because its project, while more continuous, suffered from political football and was canceled and then uncanceled.

Unfortunately, all media discussion I can see, in the mainstream as well as on Twitter, misses the point. There’s too much focus on NIMBYism, for one. Britain is not the United States. In the United States, the sequence is that first of all the system empowered NIMBYs politically and legally starting in the 1960s and 70s, and only then did it privatize the state. In the United Kingdom, this is reversed: the growth in NIMBY empowerment is recent, with rapid expansion of the expected length of an environmental impact statement, and with multiplication of conflicting regulations – for example, there are equity rules requiring serving poor and not just rich neighborhoods, but at the same time, there must be a business case, and the value of time in the British benefit-cost analysis rules is proportional to rider income. This explosion in red tape is clearly increasing cost, but the costs were very high even before it happened.

Then, there are the usual incurious ideas from the Twitter reply gallery, including some people with serious followings: Britain must have stronger property rights (no it doesn’t, and neither does the US; look at Japan instead), or it’s related to a general cost disease (British health care costs are normal), or what about Hong Kong (it’s even more expensive).

Pete Buttigieg, Bent Flyvbjerg, and My Pessimism About American Costs

A few days ago, US Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg appeared together with Bent Flyvbjerg to discuss megaprojects and construction costs. Flyvbjerg’s work on cost overruns is, in the English-speaking world, the starting point for any discussion of infrastructure costs, and I’m glad that it is finally noticed at such a high level.

Unfortunately, everything about the discussion, in context, makes me pessimistic. The appearance was about establishing a Center of Excellence at the Volpe Center to study project delivery and transmit best practices to various agencies; but, in context with what I’ve seen at agencies as well as federal regulators, it will not be able to figure out how to learn good practices the way it is currently set up, and what it can learn, it won’t be able to transmit. It’s sad, really, because Buttigieg clearly wants to be able to build; with his current position and presidential ambitions, his path upward relies on being able to build transportation megaprojects, but the current US Department of Transportation (USDOT) and the political system writ large seem uninterested in reforming in the right direction.

What Flyvbjerg said

Flyvbjerg’s studies are predominantly about cost overruns, rather than absolute costs. The insights required to limit overruns are not the same as those required to reduce costs in general, but they intersect substantially, and in recent years Flyvbjerg has written more about absolute costs as well. The topics he discussed with Buttigieg are in this intersection.

In latter-day Flyvbjerg, there’s a great emphasis on standardization and modularity. He speaks favorably of Spain’s standardized construction methods as one reason for its famously low construction costs – costs that remain very low in the 2020s. We found something similar in our own work, seeing an increase of 50% in New York construction costs coming from lack of standardization in track and station systems; in our own organization, we conceive of standardization as a design standard, separate from the issue of project delivery, but fundamentally it’s all about how to deliver infrastructure construction cost-effectively.

To an extent, the American public-sector transportation project managers I know are aware of the issue of modularity, and are trying to apply it at various levels. However, they are hampered both by obstructive senior managers and political appointees and by federal regulations. For example, to build commuter rail stations, modular design requires technology that, due to supply chain issues, is not made in the United States; this requires a waiver from Buy America rules, which should be straightforward since “not made in the US” is a valid legal reason, but the relevant federal regulatory body is swamped with requests and takes too long to process them, and the federal regulators we spoke to were sympathetic but didn’t seem interested in processing requests faster.

But Flyvbjerg goes further than just asking for design modularity. He uses the expression “You’re unique, like everybody else.” He talks about learning from other projects, and Buttigieg seems to get it. This is really useful in the sense that nothing that is done in the United States is globally unique; California High-Speed Rail, among the projects they discussed, was an attempt to import technology that already 15 years ago had a long history in Western Europe and Japan. But that project was still planned without any attempt to learn the successful project delivery mechanisms of those older systems. And the Volpe Center, federal regulators, and federal politicos writ large seem uninterested in foreign learning even now.

What we’ve seen

Eric, Elif, Marco, and I have presented our findings to Americans at various levels – not to Buttigieg himself, but to people who I think may regularly interact with him; I can’t tell the exact level, not being familiar with government insider culture. Some of the people we’ve interacted with seem helpful, interested in adopting some of our findings, and willing to change things; others are not.

But what we’ve persistently seen is an unwillingness to just go ahead and learn from foreigners. The new Center of Excellence is run by Cynthia Maloney, who’s worked for Volpe and DOT since 2014 and worked for NASA before; I know nothing of her, but I know what she isn’t, which is an experienced transportation professional who has delivered cost-effective projects before, a type of person who does not exist in the United States and barely exists in the rest of the English-speaking world.

And there’s the rub. We’ve talked to Americans at these levels – regulators, agency heads, political advisors, appointees – and they are often interested in issues of procurement reform, interagency coordination, modular design, and so on. But when we mention the issue of learning from outside the US, they react negatively:

- They rarely speak foreign languages or respect people who do, and therefore don’t try to read the literature if it’s not written in English, such as the Cour des Comptes report on Grand Paris Express.

- They have no interest in hiring foreigners with successful experience in Europe or Asia – the only foreigner whose name comes up is Andy Byford, for his success in New York.

- They don’t ever follow up with specifics that we bring up about Milan or Stockholm, let alone Istanbul, which Elif points out they don’t even register as a place that could be potentially worth looking at.

- They sometimes even make excuses for why it’s not possible to replicate foreign success, in a way that makes it clear they haven’t engaged with the material; for a non-transportation example, a New York sanitation communications official said, with perfect confidence, that New York cannot learn from Rome, because Rome was leveled during WW2 (in fact, Rome was famously an open city).

Even the choice of which academics to learn from exhibits this bias. Flyvbjerg is very well-known in the English-speaking world as well as in countries that speak perfect nonnative English, including his own native Denmark, the rest of Scandinavia, and the Netherlands. But in Germany, France, and Southern Europe, people generally work in the local language, with much lower levels of globalization, and I think this is also the case in East Asia (except high-cost Hong Kong). And there’s simply no engagement with what people here do from the US; the UK appears somewhat better.

You can’t change the United States from a country that builds subways for $2 billion/km in New York and $1 billion/km elsewhere to a country that does so for $200 million/km if all you ever do is talk to other Americans. But the Volpe Center appears on track to do just that. The American political sphere is an extremely insulated place. One of the staffers we spoke to openly told us that it’s hard to sell foreign learning to the American public; well, it’s even harder to sell infrastructure when it’s said to cost $300 billion to turn the Northeast Corridor into a proper high-speed line, where here it would cost $20 billion. DOT seems to be choosing, unconsciously, not to have public transportation.

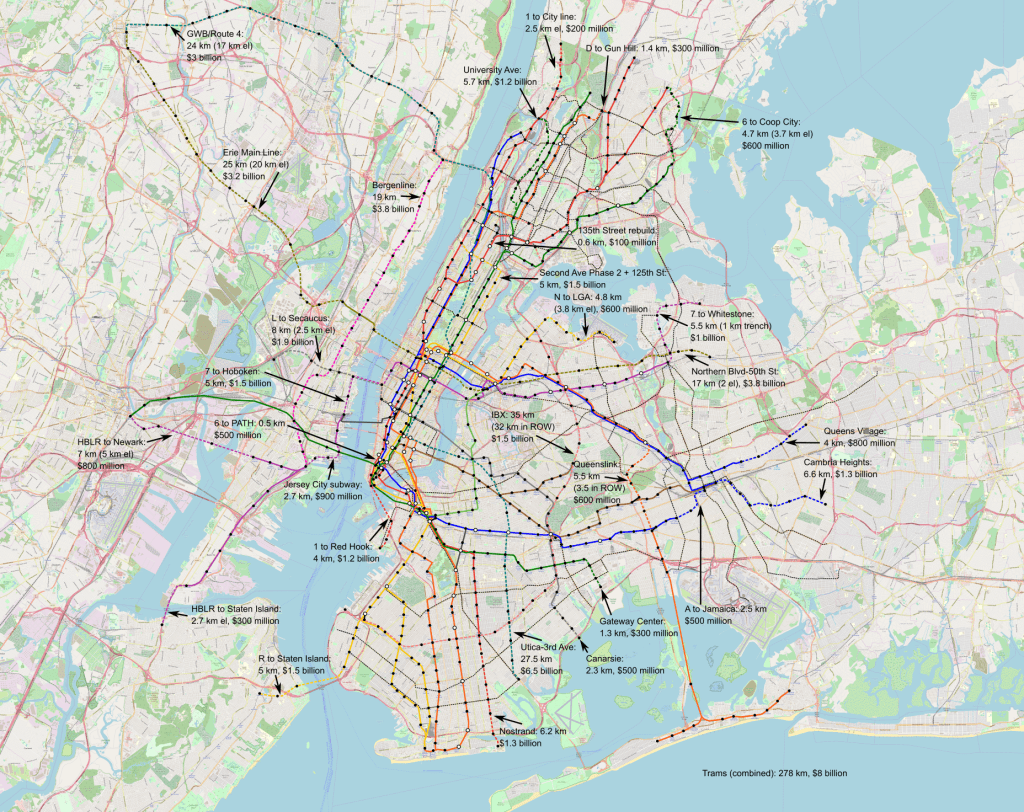

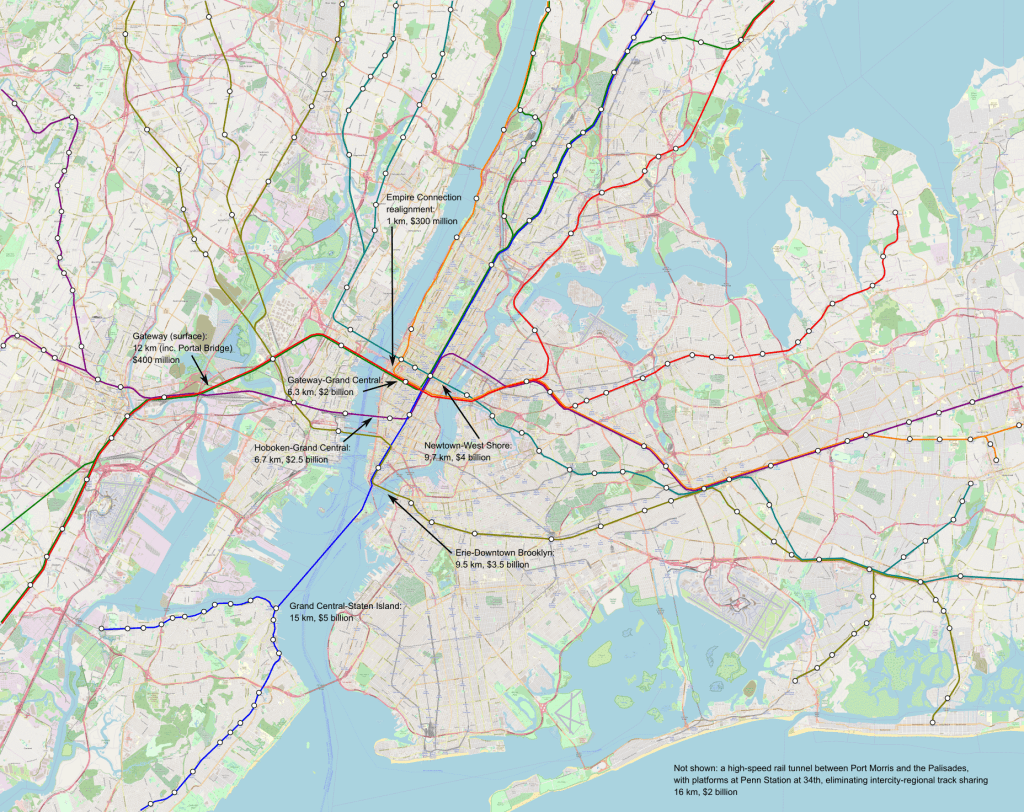

Assume Normal Costs: An Update

The maps below detail what New York could build if its construction costs were normal, rather than the highest in the world for reasons that the city and state could choose to change. I’ve been working on this for a while – we considered including these maps in our final report before removing them from scope to save time.

Higher-resolution images can be found here and here; they’re 53 MB each.

Didn’t you do this before?

Yes. I wrote a post to a similar effect four years ago. The maps here are updated to include slightly different lines – I think the new one reflects city transportation needs better – and to add light rail and not just subway and commuter rail tunnels. But more importantly, the new maps have much higher costs, reflecting a few years’ worth of inflation (this is 2022 dollars) and some large real cost increases in Scandinavia.

What’s included in the maps?

The maps include the following items:

- 278 km of new streetcars, which are envisioned to be in dedicated lanes; on the Brooklyn and Queensborough Bridges, they’d share the bridges’ grade separation from traffic into Manhattan, which in the case of the Brooklyn Bridge should be an elevated version of the branched subway-surface lines of Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and most German cities. Those should cost $8 billion in total, based on Eno’s European numbers plus some recent urban German projects.

- 240 km of new subway lines, divided as 147.6 km in the city (97.1 km underground) and 92.4 km across the Hudson and in New Jersey (45.2 km underground). Of those 240 km, 147.5 km comprise four new trunk lines, including the already-planned IBX, and the rest are extensions of existing lines. Those should cost $25.2 billion for the city lines and $15.4 billion for the New Jersey lines.

- Rearrangement of existing lines to reduce branching (“deinterlining“) and improve capacity and schedule robustness; the PATH changes are especially radical, turning the system into extensions of the 6 and 7 trains plus a Hoboken-Herald Square shuttle.

- 48.2 km of commuter rail tunnels, creating seven independent trunk lines across the region, all running across between suburbs through the Manhattan core. In addition to some surface improvements between New York and Newark, those should cost $17.7 billion, but some additional costs, totaling low single-digit billions, need to be incurred for further improvements to junctions, station platforms, and electrification.

The different mode of transportation are intended to work together. They’re split across two maps to avoid cluttering the core too much, but the transfers should be free and the fares should be the same within each zone (thus, all trains within the city must charge MetroCard/OMNY fare, including commuter rail and the JFK AirTrain). The best way to connect between two stations may involve changing modes – this is why there are three light rail lines terminating at or near JFK not connecting to one another except via the AirTrain.

What else is included?

There must be concurrent improvements in the quality of service and stations that are not visible on a map:

- Wheelchair accessibility at every station is a must, and must be built immediately; a judge with courage, an interest in improving the region, and an eye for enforcing civil rights and accessibility laws should impose a deadline in the early to mid 2030s for full compliance. A reasonable budget, based on Berlin, Madrid, and Milan, is about $10-15 million per remaining station, a total of around $4 billion.

- Platform edge doors at every station are a good investment as well. They facilitate air conditioning underground; they create more space on the platform because they make it easier to stand closer to the platform edge when the station is crowded; they eliminate deaths and injuries from accidental falls, suicides, and criminal pushes. The only data point I have is from Paris, where pro-rated to New York’s length it should be $10 million per station and $5 billion citywide.

- Signaling must be upgraded to the most modern standards; the L and 7 trains are mostly there already, with communications-based train control (CBTC). Based on automation costs in Nuremberg and Paris, this should be about $6 billion systemwide. The greater precision of computers has sped up Paris Métro lines by almost 20% and increased capacity. Together with the deinterlining program, a single subway track pair, currently capped at 24 trains an hour in most cases, could run about 40 trains per hour.

- Improvements in operations and maintenance efficiency don’t cost money, just political capital, but permit service to be more reliable while cutting New York’s operating expense, which are 1.5-2.5 time a high as the norm for large first-world subway systems.

The frequency on the subway and streetcar lines depicted on the map must conform to the Six-Minute Service campaign demand of Riders Alliance and allies. This means that streetcars and subway branches run very six minute all day, every day, and subway trunk lines like the 6, 7, and L get twice as much frequency.

What alternatives are there?

Some decisions on the map are set in stone: an extension of Second Avenue Subway into Harlem and thence west along 125th Street must be a top priority, done better than the present-day project with it extravagant costs. However, others have alternatives, not depicted.

One notable place where this could easily be done another way is the assignment of local and express trains feeding Eighth and Sixth Avenues. As depicted, in Queens, F trains run local to Sixth Avenue and E trains run express to Eighth; then, to keep the local and express patterns consistent, Washington Heights trains run local and Grand Concourse trains run express. But this could be flipped entirely, with the advantage of eliminating the awkward Jamaica-to-Manhattan-to-Jamaica service and replacing it with straighter lines. Or, service patterns could change, so that the E runs express in Queen and local in Manhattan as it does today.

Another is the commuter rail tunnel system in Lower Manhattan. There are many options for how to connect New Jersey, Lower Manhattan, and Brooklyn; I believe what I drew, via the Erie Railroad’s historic alignment to Pavonia/Newport, is the best option, but there are alternatives and all must be studied seriously. The location of the Lower Manhattan transfer station likewise requires a delicate engineering study, and the answer may be that additional stops are prudent, for example two stops at City Hall and South Ferry rather than the single depicted station at Fulton Street.

What are those costs?

I encourage people to read our costs report to look at what goes into the numbers. But, in brief, we’ve identified a recipe to cut New York subway construction costs by a factor of 9-10. On current numbers, this means New York can cut its subway construction costs to $200-250 million per kilometer – a bit less in the easiest places like Eastern Queens, somewhat more in Manhattan or across water. Commuter rail tunnel costs are higher, first because they tend to be built only in the most difficult areas – in easier ones, commuter rail uses legacy lines – and second because they involve bigger stations in more constrained areas. Those, too, follow what we’ve found in comparison cases in Southern Europe, the Nordic countries, Turkey, France, and Germany.

In total, the costs so projected on the map, $66.3 billion in total, are only slightly higher than the total cost of Grand Paris Express, which is $60 billion in 2022 dollars. But Paris is also building other Métro, RER, and tramway extensions at the same time; this means that even the program I’m proposing, implemented over 15 years, would still leave New York spending less money than Paris.

Is this possible?

Yes. The governance changes we outline are all doable at the state level; federal officials can nudge things and city politician can assist and support. There’s little confidence that current leadership even wants to build, let alone knows what to do, but it’s all doable, and our report linked in the lede provides the blueprint.

Quick Note: Los Angeles Spends $50,000 Per Bus Shelter

I saw a few months ago that Los Angeles was planning to equip its entire bus network with shelter, and rejoiced that such an underrated amenity finally gets the attention it deserves. Unfortunately, the cost of the program is now $50,000 per bus shelter; to lower the cost, the city is experimenting with a substandard shelter providing no protection from the elements for $10,000. In Victoria, as pointed out by one commenter on Twitter, a full shelter is around $15,000 in 2018 Canadian dollars, comparable to 2023 American ones.

Ordinarily, it would be a dog-bites-man story: of course the costs are at a premium of a factor of three over Canada (let alone a place that builds cheaply), it’s an American transit infrastructure project. But this one is significant because bus shelter is small in scope – it’s not a megaproject, and this means that rules of megaprojects do not apply to it.

For example, installing shelter at thousands of stops, as Los Angeles is doing, allows for repetition of a standard design that vendors can figure out on their own. This means that the usual privatization of decisionmaking should not be a problem. (It’s been pointed out to me that design-build works well for municipal parking garages, since they’re so streamlined at this point.)

Moreover, bus shelter, even repeated so many times, is still small enough scope that a small in-house team could handle it. LACMTA has been talking to us about how to scale up their in-house team, and we couldn’t give them concrete numbers, but I believe what they have for design review is in the teens, which is probably not enough for a subway extension but should be for a bus shelter program measured in the tens of millions of dollars or (with the cost blowouts factored in) very low hundreds of millions. Elsewhere, for example in Boston, we’ve seen agencies build small things affordably – Boston’s premium over Berlin for building infill commuter rail stations is a factor of maybe 1.5 – and fail at building large things such as urban rail expansion, because their design review team is sized for small and not large things.

Finally, there’s a problem with politicization, in which when politicians insert themselves into a piece of infrastructure, hoping to make it their legacy, it will end up raising costs with at best no and at worst negative benefit to users. Small items like this ordinarily do not have this problem, as they fly under the radar of politicians as well as surplus-extracting community groups.

So why is this so expensive?

I don’t know the details of this failure – all I know is a handful of links to the current cost. I suspect, judging by the tone used in press coverage, that it’s politicization. Note that the piece linked in the lead paragraph centers the issue of gender equity; this isn’t stupid (as the other link points out, bus shelter has a disproportionately positive impact on women), but it does suggest someone thought about the political implications of this. The piece also quotes the designers as having developed the new substandard option “with input from female riders,” suggesting some waste on community consultation.

If I’m right on this, then this suggests a great peril for any city that looks at small and large projects, finds that the small ones are more cost-effective, and decides to prioritize them over large ones. In a city that builds subway expansion and also installs bus shelter beneath anyone’s notice, the bus shelter may be achievable at reasonable cost. But as soon as the shelter turns into a splashy program, beloved by incompetent managers who figure it’s within their span of control and by politicians (who are by definition incompetent on managerial issues), it will acquire the same problems of politicization usually associated with megaprojects. In this case, it’s waste coming from community consultation. In other cases, it might be demands for neighborhood signatures, or intransigence by abutting property owners or by utilities figuring there is surplus to extract, or any of the other causes of cost overruns.

And in particular, downgrading your city’s investment plan just because the flashiest items have cost blowouts wouldn’t end the cost blowouts. If you can’t build subways, work on making yourself capable of building subways; avoiding that mess and building other things instead of subways would run into the same problems and soon you’d be paying $50,000 for a single bus shelter.