Category: High-Speed Rail

16-Car Trains on the Northeast Corridor

The dominant length of high-speed rail platforms in China, Japan, South Korea, and Europe is 400 meters, which usually corresponds to 16-car trains. The Northeast Corridor unfortunately does not run such long trains; intercity trains on it today are usually eight cars long, and the under construction Avelia Liberty sets are 8.5 cars long. Demand even today is high enough that trains fill even with very high fares, and so providing more service through both higher frequency and longer trains should be a priority. This post goes over what needs to happen to lengthen the trains to the global norm for high-speed rail. More trains need to be bought, but also the platforms need to be lengthened at many stations, with varying levels of difficulty.

The station list to consider is as follows:

- Boston South Station

- Providence

- New London-HSR

- New Haven

- Stamford

- New York Penn Station

- Newark Penn Station

- Trenton

- Philadelphia 30th Street

- Wilmington

- Baltimore Penn Station

- BWI

- Washington Union Station

Some of these are local-only stations – the fastest express trains should not be stopping at New London or BWI, and whether any train stops at Stamford or Trenton is a matter of timetabling (the headline timetable we use includes Stamford on all trains but I am not wedded to it). In order, allowing 16-car trains at these stations involves the following changes.

Boston

South Station’s longest platforms today are those between tracks 8 and 9 and between tracks 10 and 11, both 12 cars long. To their immediate south is the interlocking, so lengthening would be difficult.

Moreover, the best platforms for Northeast Corridor trains to use at South Station are to the west. The best way to organize South Station is as four parallel stations, from west to east (in increasing track number order) the Worcester Line, the Northeast Corridor and branches, the Fairmount Line, and the Old Colony Lines, with peak traffic of respectively 8, 12 or 16, 4 or 8, and 6 trains per hour. This gives the Northeast Corridor tracks 4-7 or possibly 4-9; 4-7 means the Franklin Line has to pair with the Fairmount Line to take advantage of having more tracks, and may be required anyway since pairing the Franklin Line with the Northeast Corridor (Southwest Corridor within the city of Boston) would constrain the triple-track corridor too much, with 12 peak commuter trains and 4 peak intercity trains an hour.

The platform between tracks 6 and 7 is 11 cars long, but to its south is a gap in the tracks as the interlocking leads tracks 6 and 7 in different directions, and thus it can be lengthened to 16 cars within its footprint. The platform between tracks 4 and 5 is harder to lengthen, but this is still doable if the track that tracks 5 and 6 merge into south of the station is moved in conjunction with a project to lengthen the other platform.

Of note, the other Boston station, Back Bay, is rather constrained, with nearly the entire platforms under an overbuild, complicating any rebuild.

Providence

Providence has 12-car platforms. The southern edge is under an overbuild with rapid convergence between the tracks and cannot reasonably be extended. But the northern edge is in the open air, and lengthening is possible. The northern edge would be on rather tight curves, which is not acceptable under most standards, but in such a constrained environment, waivers are unavoidable, as is the case throughout urban Germany.

New London

This is a new station and can be built to the required length from the start.

New Haven

The current station platforms are only 10 cars long, but there is space to expand them in both directions. The platform area is in effect a railyard, a good example of the American tradition in which the train station is not where the trains are (as in Europe) but rather next to where the trains are.

A rebuild is needed anyway, for two reasons. First, it is desirable to build a bypass roughly following I-95 to straighten the route beginning immediately north of the station, even cutting off State Street in order to go straight to East Haven rather than curve to the north as on the current route. And second, the current usage of the station is that Amtrak uses tracks 1-4 (numbered west to east as in Boston) and Metro-North uses tracks 8-14, which forces Amtrak and Metro-North trains to cross each other at grade from their slow-fast-fast-slow pattern on the running line to the fast-fast-slow-slow pattern at the station. In the future, the station should be used in such a way that intercity trains either divert north to Hartford or Springfield or go immediately east on a flying junction to the high-speed bypass toward Rhode Island, without opposed-direction flat junctions; the flying junction is folded into the cost of the bypass and dominates the cost of rebuilding the platforms, as the space immediately north and south of the platforms is largely empty.

Stamford

Stamford has 12-car platforms. Going beyond that is hard, to the point that a more detailed alternatives analysis must include the option of not having intercity trains stop there at all, and instead running 12-car express commuter trains, lengthening major intermediate stops like South Norwalk (currently 10 cars long) and Bridgeport (currently 8) instead.

To keep the mainline option of stopping at Stamford, a platform rebuild is needed, in two ways. First, the station today has five tracks, a both literally and figuratively odd number, not useful for any timetable, with the middle track, numbered 1 (from north to south the numbers are 5, 3, 1, 2, 4), not served by a platform. And second, the platform between tracks 3 and 5 can at best be lengthened to 14 cars, while that between tracks 2 and 4 cannot be lengthened without moving tracks on viaducts. This means that some mechanism to rebuild the station should be considered, to create four tracks with more space between them so that 16-car platforms are viable; this should be bundled with a flying junction farther east to grade-separate the New Canaan Branch from the mainline.

A quick-and-dirty option, potentially viable here but almost nowhere else, is selective door opening, at the cost of longer dwell times. Normally selective door opening should not be used – it confuses passengers, for one. However, here it may be an option, as intercity traffic here is unlikely to be high; traffic today is 323,791 in financial 2023, the lowest of any station under consideration in this post unless one counts New London. The only reason to stop here in the first place is commuter ridership, in which case mechanisms such as restricting unreserved seats to the central 12 cars can be used.

New York

Penn Station has multiple platforms already long enough for 16- and even 17-car trains, including the one we pencil for all high-speed intercity trains in the proposal, platform 6 between tracks 11 and 12, as well as the two adjacent platforms, 5 and 7. (Note that unlike at New Haven and Boston, platform numbers at Penn increase south to north, that is right to left from the perspective of a Boston-bound traveler.)

Thank the god of railways, since platform expansion requires a multi-billion dollar project to remove the Madison Square Garden overbuild in the most optimistic case; in a more pessimistic case, it would also require removing the Moynihan Station overbuild.

Newark

Newark Penn Station’s platforms are in a grand structure about 14.5 cars long. Thankfully, they extend a bit south of it, producing about 16 cars’ worth of platform on the west (southbound) side, between tracks 3 and 4; as in New York, track numbers increase east to west. On the east side, PATH interposes between the two tracks, which have a cross-platform transfer from northbound New Jersey Transit trains to PATH. The platform structures and their extensions do have enough length to allow 16-car trains – indeed they go as long as 18 – but the southern ends are currently disused and would require some rehabilitation.

Trenton

Trenton has a 12.5 car long southbound platform and an 11.5 car long northbound platform. There is practically no room for an expansion if no tracks are moved. If tracks are moved, then some space can be created, but only enough for about 14 cars, not 16.

However, traffic is low, the second lowest among stations under consideration next to Stamford. The suite of Stamford solutions is thus most appropriate here: selective door opening with only the middle 12 cars (naturally the same as at Stamford) open to commuters, or just not stopping at this station at all. The only reason we’re even considering stopping here is timetabling-related: trains should be running every 10 minutes around New York but every 15 between Baltimore and Washington, or else significant expansion of quad-tracking on the Penn Line is required, and so a local stop should be added as a buffer, which can be Trenton or BWI, and BWI has twice the current Amtrak traffic of Trenton.

Philadelphia

30th Street Station has 14-car platforms. Selective door opening is basically impossible given the high expected traffic at this station, and instead platform expansion is required. There is an overbuild, but the tracks stay straight and only begin curving after a few tens of meters, which gives room for extension; from the north end to the overbuild to where the tracks begin curving toward one another to the south is 15.5 cars, and there is room north of the overbuild between the tracks.

Whatever reconstruction project is needed is helped by the low traffic at these platforms. SEPTA uses the upper level of the station, with tracks oriented east-west. The north-south lower level is only used by Amtrak, which could be easily reduced to three platform tracks (two Northeast Corridor, one Keystone) if need be, out of 11 today. Thus, staging construction can be done easily and intrusively, with no care taken to preserve track access during the work, as half the station platforms can be closed off at once.

Wilmington

Wilmington is frustrating, in that there is platform space for 16 cars rather easily, but it’s on inconsistent sides of the tracks. Track numbers increase south to north; track 1 has a side platform, there’s an island platform between tracks 2 and 3, and then track 3 also has a side platform on the other side, extending well to the east of the island platform. The island platform and the track 1 platform are about 12.5 cars long, and the track 3 side platform is 13.5 cars long. Thus, an extension, selective door opening, or a station rebuild is required.

The island platform can be extended about one car in each direction, so it cannot be the solution without selective door opening. Both side platforms can be extended somewhat to the west: the track 1 platform can be extended to 16 cars, but it would need to be elevated in the narrow space between the track viaduct and the station parking garage; the track 3 platform can be extended in both directions, avoiding a new elevated extension over North King Street.

If for some reason an extension of the track 1 platform is not possible, then selective door opening can be used, but not as reliably as at lower-traffic Stamford or Trenton, and overall I would not recommend this solution. A station rebuild then becomes necessary: the station has three tracks but doesn’t need more than two if SEPTA and Amtrak can be timetabled right, and then the removal of either track 1 or track 2 would create space for a longer platform.

Baltimore

Baltimore Penn has seven tracks, numbered from south to north 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, F. Their platforms are 10 to 13 cars long. Northbound trains are more or less forced to use the platform between tracks 1 and 3, since the way the route tapers to a three-, then four-track line to the east forces all eastbound trains to use mainline track 1; this platform is rather narrow at its east end but has space to the west for a 16-car extension. Westbound trains can use either the platform between tracks 4 and 5 or that between tracks 6 and 7, with tracks 4 and 6 preferred over 7 as they reach the express westbound track (track 5 stub-ends). Both platforms can be extended, with the platform between tracks 6 and 7 requiring a one-car extension to the east where a ramp down to track level for track workers exists whereas that between tracks 4 and 5 has ample unused space to its west.

BWI

The two side platforms at BWI are just under 13 cars long. However, nowhere else on the corridor is an extension easier: the station is located in an undeveloped wooded area, with space cleared on both sides of the track so that tree cutting is likely unnecessary west of the tracks and certainly unnecessary east of them.

The station itself needs a rebuild anyway, due to already existing plans to widen it from three to four tracks. This is required to enable intercity trains to overtake commuter trains anyway, unless delicate timetabling on triple track is used or another part of the Penn Line is set up as a four-track overtake. The plans are rather advanced, but platform extensions can be pursued as an add-on, without disturbing them due to the easy nature of the right-of-way.

Washington

Washington is set up as two separate stations, a high-platform terminal to the west and a low-platform through-station to the east on a lower level. Track numbers increase west to east, the western part taking 7-20 (though only 9-20 are high and wired) and the eastern part 23-30. None of the western platforms is long enough, but multiple options still exist:

- The platform between tracks 9 and 10 has room for an extension.

- The platforms between tracks 15 and 16 and between tracks 16 and 17 look like they already have extensions, if not open for passengers.

- The platforms between track 17 and track 18 and between tracks 19 and 20 are only 12 cars long, but tracks could be cannibalized in the open air to make a long enough platform, especially since the reason track numbers 21 and 22 are skipped is that there used to be tracks there and now there’s empty space.

- The platform between tracks 25 and 26 is long enough, and could be raised to have level boarding.

The existing platforms that can be extended easily are sufficient in number, but probably not in location – it’s ideal for the platforms to be close together, to simplify the interlocking as trains have to be scheduled to enter and leave the station without opposite-direction conflicts. If it’s doable even with a split between platforms separated by multiple tracks then it’s ideal, but otherwise, the extra work on tracks 17-20 may be necessary, converting a part of the station that presently has six tracks and four platforms into likely four tracks and two platforms.

Conclusion

All of this looks doable. The hardest station, Stamford, is skippable if selective door opening is unviable after all and a rebuild is too expensive. Among the other stations, light rebuilds are needed at Boston, Wilmington, and maybe Washington; New Haven needs a more serious rebuild as part of the bypass, but the station platforms are a routine extension where there is already room between the tracks. The most untouchable station, New York, already has multiple platforms of the required length at the required location within the station.

Northeast Corridor Profits and Amtrak Losses

In response to my previous post, it was pointed out to me that Amtrak finances can’t really be viewed in combination, but have to be split between the Northeast Corridor, the state-supported routes, and the long-distance trains. Long-distance is defined by a 750 mile (1,200 km) standard, comprising the night trains plus the Palmetto; these trains have especially poor financial performance. The question is what level of Northeast Corridor profitability is required to cover those losses.

In financial 2024 (ending 2024-09-30), Amtrak finances per route category were as follows, in millions of dollars or passenger-km or in dollars per p-km:

| Category | Ridership | P-km | Cost | Cost/p-km | Revenue | Revenue/p-km |

| NEC | 14 | 4,053.3 | 1,146.8 | 0.283 | 1,414.6 | 0.349 |

| State-supported | 14.5 | 2,972.6 | 1,110.7 | 0.374 | 859.2 | 0.289 |

| Long-distance | 4.3 | 3,505.8 | 1,261.2 | 0.36 | 626.1 | 0.179 |

The long-distance trains don’t actually have higher cost structure than the state-supported ones. Their greater losses are because fares are degressive in distance, and so the longer distances traveled translate to lower revenue per kilometer. This is also observable on some high-speed routes in Europe – the fares on TGVs using the LGV Sud-Est are very degressive, with little premium on Paris-Nice over Paris-Lyon despite the factor of 2.5 longer distance and factor of almost 3 longer time.

Revenue per passenger-km in France and Germany is around $0.15, as I explain in this post with links, and revenue per passenger-km in Japan is $0.25, both with average trip lengths similar to those of the Northeast Corridor and state-supported trains. Getting operating costs for just high-speed trains in France and Germany is surprisingly tricky; the Spinetta report says the TGV costs 0.06€/seat-km without capital, which at current seat occupancy is around 0.08€/p-km or around $0.11/p-km.

The upshot is that Northeast Corridor profits need to be $886.6 million a year to cover losses elsewhere, and if the operating costs on the corridor were the same as on the TGV, this could be achieved now with no further increases in service.

Now, in reality, high-speed rail would both massively increase ridership and also have to involve reducing fares to more normal levels than $0.35/p-km. If the revenue is $0.15/p-km and the cost is $0.11/p-km, then traffic in p-km has to rise to 22.165 billion/year, a fivefold increase, to cover. This is less implausible than it sounds – my gravity-based ridership model predicts about that ridership. Potentially, operating costs could be lower than on the TGV, if the entire corridor is (relatively) fast, with no long sections on slow lines as in France, and if traffic is less peaky than in France. But to first order, the answer to the profits question should be “probably but not certainly.”

Amtrak’s Failure

An article in Streetsblog by Jim Mathews of the Rail Passengers Association talking up Amtrak as a success has left a sour taste in my mouth as well as those of other good transit activists. The post says that Amtrak is losing money and it’s fine because it’s a successful service by other measures. I’ve talked before about why good intercity rail is profitable – high-speed trains are, for one, and has a cost structure that makes it hard to lose money. But even setting that aside, there are no measures by which Amtrak is a successful, if one is willing to look away from the United States for a few moments. What the post praises, Amtrak’s infrastructure construction, is especially bad by any global standard. It is unfortunate that American activists for mainline rail are especially unlikely to be interested in how things work in other parts of the world, and instead are likely to prefer looking back to American history. I want to like the RPA (distinct from the New York-area Regional Plan Association, which this post will not address), but its Americanism is on full display here and this blinds its members to the failures of Amtrak.

Amtrak ridership

The ridership on intercity rail in the United States is, by most first-world standards, pitiful. Amtrak reports, for financial 2023, 5.823 billion passenger-miles, or 9.371 billion p-km; Statista gives it at 9.746 billion p-km for 2023, which I presume is for calendar 2023, capturing more corona recovery. France had 65 billion p-km on TGVs and international trains in 2023.

More broadly than the TGV, Eurostat reports rail p-km without distinction between intercity and regional trains; the total for both modes in the US was 20.714 billion in 2023 and 30.89 billion in 2019, commuter rail having taken a permanent hit due to the decline of its core market of 9-to-5 suburb-to-city middle-class commuting. These figures are, per capita, 62 and 94 p-km/year. In the EU and environs, only one country is this low, Greece, which barely runs any intercity rail service and even suspended it for several months in 2023 after a fatal accident. The EU-wide average is 955 p-km/year. Dense countries like Germany do much better than the US, as do low-density countries like Sweden and Finland. Switzerland has about the same mainline rail p-km as the US as of 2023, 20.754 billion, on a population of 8.9 million (US: 335 million).

So purely on the question of whether people use Amtrak, the answer is, by European standards, a resounding no. And by Japanese standards, Europe isn’t doing that great – Japan is somewhat ahead of Switzerland per capita. Amtrak trains are slow: the Northeast Corridor is slower than the express trains that the TGV replaced, and the other lines are considerably slower, running at speeds that Europeans associate with unmodernized Eastern European lines. They are infrequent: service is measured in trains per day, usually just one, and even the Northeast Corridor has rather bad frequencies for the intensely used line it wants to be.

Is this because of public support?

No. American railroaders are convinced that all of this is about insufficient public funding, and public preference for highways. Mathews’ post repeats this line, about how Amtrak’s 120 km/h average speeds on a good day on its fastest corridor should be considered great given how much money has been spent on highways in America.

The issue is that other countries spend money on highways too. High American construction costs affect highway megaprojects as well, and thus the United States brings up the rear in road tunneling. The highway competition for Amtrak comprises fairly fast, almost entirely toll-free roads, but this is equally true of Deutsche Bahn; the competition for SNCF and Trenitalia is tollways, but then those tollways are less congested, and drivers in Italy routinely go 160 km/h on the higher-quality stretches of road.

Amtrak itself has convinced itself that everyone else takes subsidies. For example, here it says “No country in the world operates a passenger rail system without some form of public support for capital costs and/or operating expenses,” mirroring a fraudulent OIG report that compares the Northeast Corridor (alone) to European intercity rail networks. Technically it’s true that passenger rail in Europe receives public subsidies; but what receives subsidies is regional lines, which in the US would never be part of the Amtrak system, and some peripheral intercity lines run as passenger service obligation (PSO) with in theory competitive tendering, on lines that Amtrak wouldn’t touch. Core lines, equivalent to Chicago-Detroit, New York-Buffalo, Washington-Charlotte-Atlanta, Los Angeles-San Diego, etc., would be high-speed and profitable.

But what about construction?

What offends me the most about the post is that it talks up Amtrak’s role as a construction company. It says,

Today, our nationalized rail operator is also a construction company responsible for managing tens of billions of dollars for building bridges, tunnels, stations, and more – with all the overhead in project-management staff and capital delivery that this entails.

The problem is that Amtrak is managing those tens of billions of dollars extremely inefficiently. Tens of billions of dollars is the order of magnitude that it took to build the entire LGV network to day ($65.5 billion in 2023 prices), or the entire NBS network in Germany ($68.6 billion). Amtrak and the commuter rail operators think that if they are given the combined cost to date of both networks, they can upgrade the Northeast Corridor to be about as fast as a mixed high- and low-speed German line, or about the fastest legacy-line British trains (720 km in 5 hours).

The rail operations are where Amtrak is doing something that approximates good rail work – lots of extraneous spending, driving up Northeast Corridor operating costs to around twice the fares on German and French high-speed trains, probably around 3-4 times the operating costs on those trains. But capital construction is a bundle of bad standards for everything, order-of-magnitude cost premiums, poor prioritization, and agency imperialism leading Amtrak to want to spend $16 billion on a completely unnecessary expansion of Penn Station. The long-term desideratum of auto-tensioned (“constant-tension”) catenary south of New York, improving reliability and lifting the current 135 mph (217 km/h) speed limit, would be a routine project here, reusing the poles with their 75-80 meter spacing; an incompetent (since removed) Amtrak engineer insisted on tightening to 180′ (54 m) so the project is becoming impossibly expensive as the poles have to be replaced during service. “Amtrak is also doing construction” is a derogatory statement about Amtrak.

Why are they like this?

Americans generally resent having to learn about the rest of the world. This disproportionately affects industries where the United States is clearly ahead (for example, software), but also ones where internal American features incline Americans to overfocus on their own internal history. Railroad history is rich everywhere, and the relative decline of the railway in favor of the highway lends itself to wistful alternative history, with intense focus on specific lines or regions. New Yorkers are, in the same vein, atypically provincial when it comes to the subway’s history, and end up making arguments, such as about the difficulty of accessibility retrofits on an old system, that can be refuted by looking at peer American systems, not just foreign ones.

The upshot is that an industry and an advocacy ecosystem that both intensely believe that railroad decline was because government investment favored roads – something that’s only partly true, since the same favoring of roads happened more or less everywhere – will want to learn from their own local histories. Quite a lot of advocacy by the RPA falls into the realm of trying to revive the intercity rail system the US had in the 1960s, before the bankruptcies and near-bankruptcies that led to the creation of Amtrak – but this system was what lost out to highways and cars to begin with. The innovations that allowed East Asia to avoid the same fate, and the innovations that allowed Western Europe to partly reverse this fate, involve different ideas of how to build and operate intercity rail.

And all of this requires understanding that, on a basic level, Amtrak is best described as a mishmash of the worst features of every European and East Asian railway: speed, fares, frequency, reliability, coverage. Each country that I know of misses on at least one of these aspects – Swiss trains are slow, the Shinkansen is expensive, the TGV has multi-hour midday gaps, German trains barely run on a schedule, China puts its train stations at inconvenient locations. Amtrak misses on all of those, at once.

And while Amtrak misses on service quality in operations, it, alongside the rest of the American rail construction industry, practically defines bad capital planning. Cities can build the right project wrong, or build the wrong project right, or have poor judgment about standards but not project delivery or the reverse, and somehow, Amtrak’s current planning does all of these wrong all at once.

Quick Note: High-Speed Rail and Decarbonization

I keep seeing European advocates for decarbonizing transportation downplay the importance of big infrastructure, especially high-speed rail. To that end, I’d like to proffer one argument for why high-speed rail decarbonizes transportation even when it induces new trips. Namely: induced leisure trips come at the expense of higher-carbon travel to other destinations. In the 2010s discussion on High Speed 2, for example, induced trips were counted as raising greenhouse gas emissions (while having economic benefits elsewhere), and with this understanding I think that that is wrong. This becomes especially important with the growing focus on flight shaming in Europe. A 1,000 km high-speed rail link doesn’t just compete with flying on the same corridor, but also with flying to a different destination, which may be much farther away, and thus its effect on decarbonizing transport is much larger than a model of corridor-scale competition with cars and planes predicts.

Aviation emissions

A common argument for high-speed rail in the 2000s was that it would displace on-corridor flights, reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In the American version, this argument awkwardly coexisted with a separate argument for high-speed rail, namely that it would decongest airports and allow more flight slots to faraway destinations. In the 2010s and in this decade, this contradictory thinking fell away – the United States hasn’t built anything, China builds for non-environmentalist reasons, Europe gave up on cross-border rail construction and its activists became more interested in trams-and-bikes urbanism. This is also reflected in research: for all of the hype about high-speed rail as a substitute for aviation, researchers like Giulio Mattioli point out that aviation emissions are dominated by long-distance flights, with <500 km flights comprising only 5% of aviation fuel burn and >4,000 km ones comprising 39%. Activist response to policies like France’s ban on flights competing with <2.5 hour TGVs has been to mock it as the gimmick that it is.

For this and other reasons, on-corridor competition with air travel is no longer considered an important issue. This is now being taken in the direction of arguing against 300 km/h lines; the thinking is that high speed is only really needed to compete with flights, whereas competing with cars requires something else. But that argument misses the importance of off-corridor competition. Passengers don’t just choose what mode to take on a fixed corridor; they also choose where to travel, and transport options matter to that choice.

The limits of ridership models

Ridership models tend to be local. SNCF uses a gravity model, in which the ridership between a pair of cities with populations , of distance

, is said to be proportional to about

. I’ve used the same in my modeling, which predicts Tokyo-to-province ridership rather well but then severely underpredicts Taiwanese ridership.

The issue is that the model is local: if I live in Berlin and want to go to Munich, the model looks only at what’s between Berlin and Munich, and doesn’t consider that I can go to other cities instead if they’re more convenient to get to. One consequence of this is that the model probably overpredicts ridership in larger milieus than in smaller ones for this reason (the Tokyo resident can go to Osaka but also to Tohoku, etc.). But an equal consequence is that off-corridor competition is global.

The limits of leisure travel

Leisure travel is discretionary, and limited by vacation time. Building new high-speed lines does not mean that the country is offering workers more vacation days. The upshot is that every new line competes off-corridor with other lines, but also with other modes. A tightly integrated national high-speed rail system offers domestic tourism by rail, competing not just with flying on longer corridors like Berlin-Cologne, where the trains take four hours and are unreliable, but also with flying to places that the train doesn’t get to.

This has implications to a Europe-wide system as well. Right now, flights from Northern Europe to Southern Europe are on corridors where rail travel is only viable if you are an environmental martyr, really like 14-hour train trips, or ideally both. High-speed rail would by itself not compete on most of these corridors – those Spanish coastal cities are too far from Northern Europe for a mode other than flying, for one. But it would offer reasonable service to other places in Southern Europe with warm climate. Speeding up the Paris-Nice TGV means Parisians would choose to travel to Nice more and to islands less. Building high-speed rail approaches connecting to the base tunnels across the Alps means Germans, especially Southern Germans, could just go to large Italian cities instead of flying to islands or to Turkey. Even business travel may be affected, through replacement of flights to other continents.

One- and Two-Dimensional Rail Networks

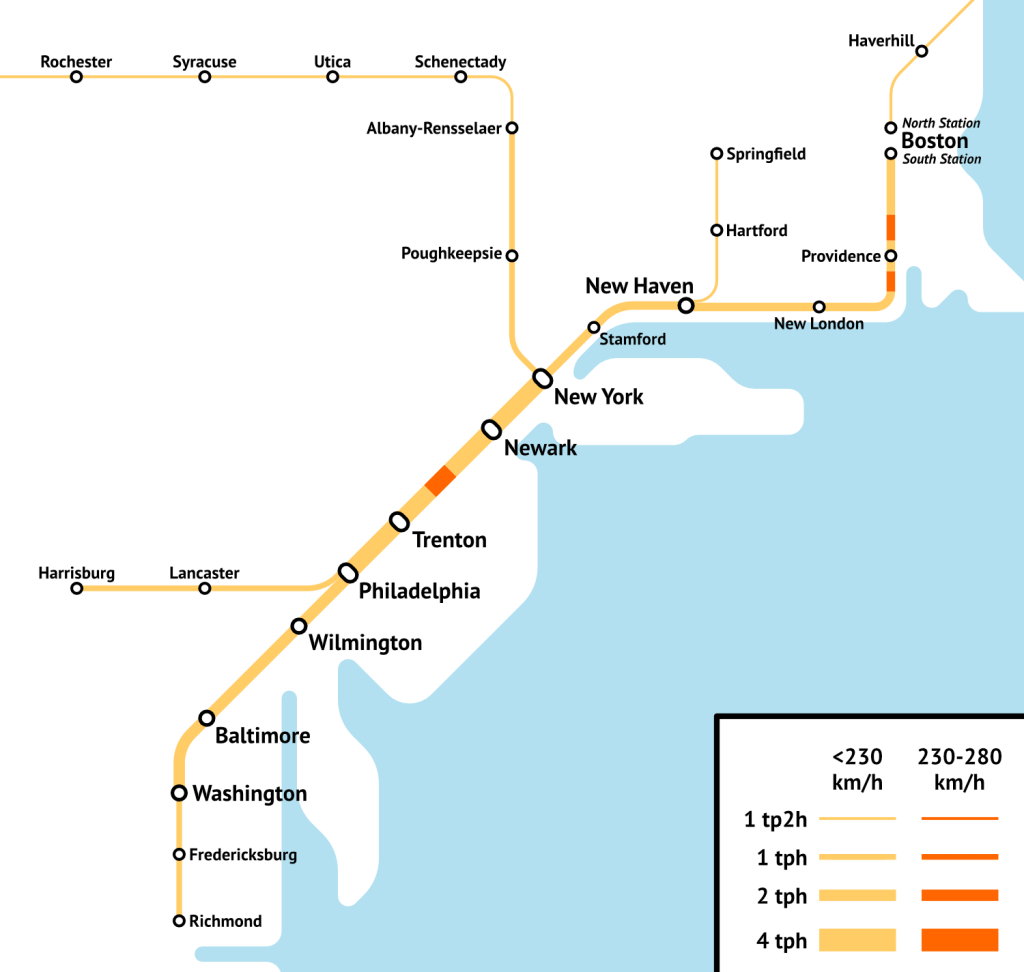

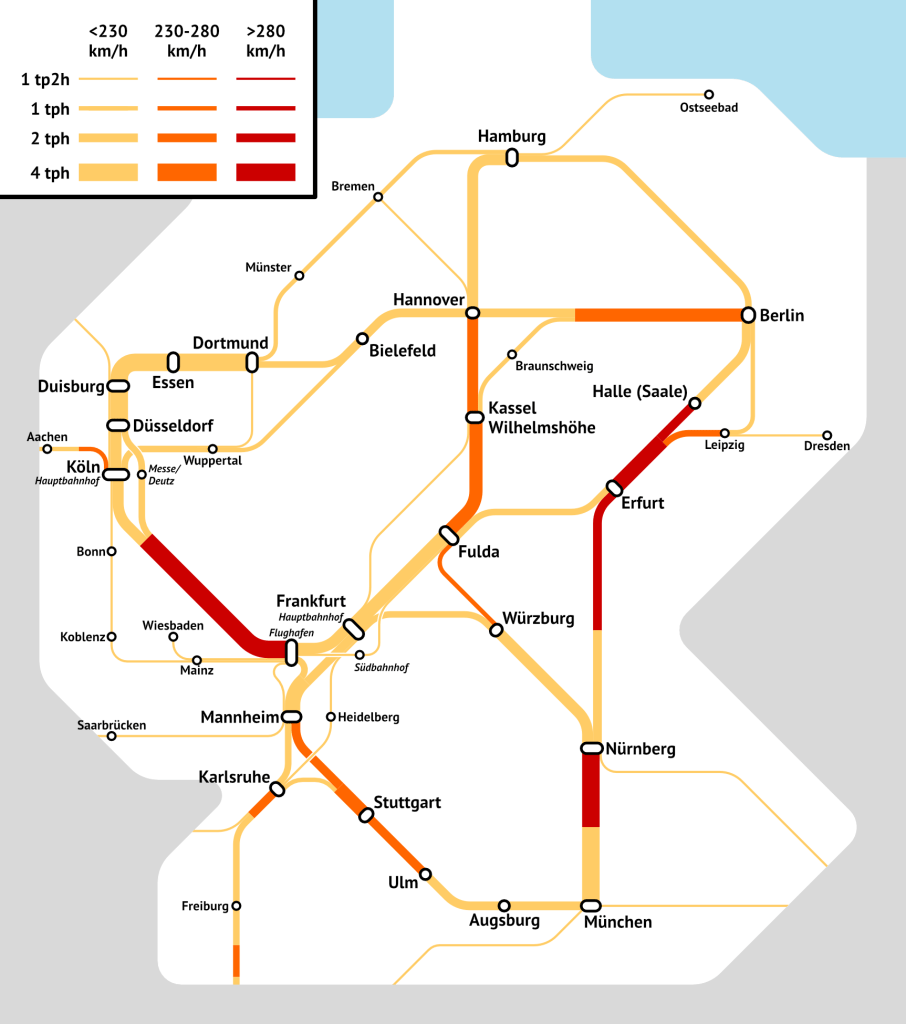

As people on social media compare the German and American rail networks, I’m going to share two graphics from the upcoming Northeast Corridor report, made by Kara Fischer. They are schematic so it’s not possible to speak of scale, but the line widths and colors are the same in both; both depict only lines branded as Amtrak or ICE, so Berlin-Dresden, where the direct trains are branded IC or EuroCity, is not shown, and neither are long-range commuter lines even if they are longer than New Haven-Springfield.

The Northeastern United States has smaller population than that of Germany but not by much (74 million including Virginia compared with 84 million), on a similar land area. Their rail networks should be, to first order, comparable. Of course they aren’t – the map above shows just how much denser the German rail network is than the American one, not to mention faster. But the map also shows something deeper about rail planning in these two places: Germany is two-dimensional, whereas the Northeastern US is one-dimensional. It’s not just that the graph of the Northeastern rail network is acyclic today, excluding once-a-day night trains. More investment in intercity rail would produce cycles in the Northeastern network, through a Boston-Albany line for one. But the cycles would be peripheral to the network, since Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington are collinear on the Northeast Corridor, and the smallest of these four metro areas, Philadelphia, is larger than all those on the branches depicted above, combined.

The most important effect on network planning is that it turns the Northeast Corridor into easy mode. We would not be able to come up with a coherent timetable for Germany on the budget that our program at Marron had. In the Northeast, we did, because it’s a single line, the main difficulty being overtakes of commuter trains that run along subsections.

This, in turn, has two different implications, one for each place.

The one-dimensionality of the Northeast

In the Northeast, the focus has to be on compatibility between intercity and commuter trains. Total segregation of tracks requires infrastructure projects that shouldn’t make the top 50 priorities in the Northeast, especially at the throats of Penn Station, South Station, and Washington Union Station. Total segregation of tracks not counting those throats requires projects that are probably in the top 50 but not top 20. Instead, it’s obligatory to plan everything as a single system, with all of the following features:

- Timed overtakes, with infrastructure planning integrated into timetable design so that the places with overtakes, and only the places with overtakes, get extra tracks as necessary.

- Simpler commuter rail timetabling, so that the overtakes can be made consistent, and so that trains can substitute for each other as much as possible in case of train delays or cancellation.

- Higher-performance commuter rail rolling stock, to reduce the speed difference between commuter and intercity trains; the trains in question are completely routine in German regional service, where they cost about as much as unpowered coaches do in the United States, but they are alien to the American planning world, which does not attend InnoTrans, does not know how to write an RFP that European vendors will respect, and does not know what the capabilities of the technology are.

- Branch pruning on commuter rail, which comes at a cost for some potential through-running pairs – trains from New Jersey, if they run through to points east of Penn Station, should be going to the New Haven Line and Port Washington Branch, and probably not to Jamaica; Newark-Jamaica service is desirable, but it would force dependency between the LIRR and intercity trains, which may lead to too many delays.

In effect, even an intercity rail investment plan would be mostly commuter rail by spending. The projects mentioned in this post are, by spending, almost half commuter rail, but they come on top of projects that are already funded that are commuter rail-centric, of which the biggest is the Hudson Tunnel Project of the Gateway Program. This is unavoidable, given the amount of right-of-way sharing between intercity trains and the busiest commuter rail lines in the United States. The same one-dimensionality that makes intercity rail planning easier also means that commuter rail must use the same non-redundant infrastructure that intercity rail does, especially around Penn Station.

The two-dimensionality of Germany

A two-dimensional network cannot hope to put all of the major cities on one line, by definition. Germany’s largest metro areas are not at all collinear. In theory, the Rhine-Ruhr, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Munich are collinear. In practice, not only does this still exclude Berlin and Hamburg, which is not at all like how Northeastern US collinearity works, but also the Rhine-Ruhr is a two-dimensional polycentric region, and Frankfurt is a terminal station oriented in such a way that a Stuttgart 21-style through-running project would allow for through-service from Stuttgart or from Cologne to points east but not from Stuttgart to Cologne. There’s also a tail of regions in the 1-1.5 million population range – Leipzig, Dresden, Nuremberg, Hanover, Karlsruhe – that are collectively larger than the largest single-core region (Berlin), even if they’re still smaller collectively than the eight-core Rhine-Ruhr region. The highest-demand link, Frankfurt-Mannheim, is a bottleneck between many city pairs, and is not at all dominant over other links in frequency or demand.

This makes for a network that is, by necessity, atypically complex. Train delays between Frankfurt and Mannheim can cascade as far as Berlin and Hamburg. There are timed connections, timed overtakes of slower regional trains on shared links (more or less everything in yellow on the map), and bypasses around terminal stations including Frankfurt and Leipzig as well as around Cologne, which is a through-station oriented east-west permitting through-service from Belgium and Aachen to the rest of Germany but not between Frankfurt and Dusseldorf.

Not for nothing, Deutsche Bahn has not really been able to make all of this work. The timetable padding is around 25%, compared with 10-13% on the TGV, and even so, delays are common and the padding is evidently not enough to recover from them.

The solution has to be reducing the extent of track sharing. The yellow lines on the map should not be yellow; they should be red, with dedicated passenger-only service, turning Germany into a smaller version of China. The current paradigm pretends Germany can be a larger version of Switzerland instead. But Switzerland builds tunnels galore to go around strategic bottlenecks, and even then makes severe compromises on train speeds – the average speeds between Zurich, Basel, and Bern are around 100 km/h, which works for a country the size of Switzerland but not for one the size of Germany, in which even the current 130-150 km/h average speeds are enough to get rail advocates to never take any other mode but not enough to get other people to switch.

In effect, the speed vs. reliability tradeoff that German rail advocates think in terms of is fictional. The two-dimensionality of Germany means that the only way to run reliably is not to have high frequency of both fast and slow trains on the same tracks between Berlin and Halle, between Munich and Ingolstadt, between Hanover and Hamburg, etc. Eliminating the regional trains is a nonstarter, so this means the intercity trains need to go on passenger-dedicated tracks.

In contrast, careful timetabling of intercity and regional trains on the same line has limited value in Germany. The regional trains in question have low ridership – the core of German commuter rail is S-Bahn systems that run in dedicated city center tunnels and have limited track sharing with the rest of the network, much less with the ICEs. If there’s high regional traffic on a particular link, it comes from combining hourly trains on many origin-destination pairs, in which case trains cannot possibly substitute for one another during traffic disturbances, and timetabling with low padding is unlikely to work.

Like Takt-based planning for Americans, building a separate intercity rail network for Germans comes off as weird and foreign. France and Southern Europe do it, and Germans look down on France and Southern Europe almost to the same extent that Americans look down on Europe. But it’s the only path forward. If anything, this combination of speed with reliability means that completing an all-high-speed connection on a major trunk line, like Berlin-Munich or Cologne-Munich, would permit cutting the timetable padding to more reasonable levels, which would save time on top of what is saved by the higher top speed. Germany could have TGV average speeds as part of this system, if it realized that these average speeds are both necessary and useful for passengers.

Consultant Slop and Europe’s Decision not to Build High-Speed Rail

I’m sitting on a series of three trains to Rome, totaling 14 hours of travel. If a high-speed rail network is built connecting those cities, the trip can be reduced to about 7.5 hours: 2.5 Berlin-Munich (currently 4), 2 Munich-Verona (currently 5.5), around 2.75 Verona-Rome (currently 3.5), around 0.25 changing time (currently 1). The slowest section is being bypassed with the under-construction Brenner Base Tunnel, but not all of the approaches to the tunnel are, and Germany is happy with its trains averaging slightly slower speeds than the 1960s express Shinkansen.

I bring this up because it’s useful background for a rather stupid report by Transport and Environment that was making the rounds on European social media, purporting to rank the different intercity rail operators of Europe, according to criteria that make it clear nobody involved in the process cares much about infrastructure construction or about what has made high-speed rail work at the member state level. It’s consultant slop, based on a McKinsey report that conflicts with the published literature on intercity rail ridership elasticity, which makes it clear that speed matters greatly. Astonishingly, even negative discourse about the study, by people who I respect, talks about the slop and about the problems of privatization, but not about the need to actually go ahead and build those high-speed connections, without which there are sharp limits to the quality of life available to the zero-carbon lifestyle, limits that make people avoid that lifestyle and instead fly and drive. In effect, Europe and its institutions have made a collective decision over the last 10 or so years not to build high-speed rail, to the point that activism suggesting it reverse course and do so is treated as self-evidently laughable.

The T&E study

The T&E study purports to rank the intercity rail operators of Europe. There are 27 operators so ranked, which do not exactly correspond to the 27 member states, but instead omit some peripheral states, include British and Swiss options, and have some private operators, including inexplicably treating OuiGo as separate from the rest of the TGV. The ranking is of operators rather than infrastructure systems; there is no attention given to planning infrastructure and operations together. Trenitalia comes first, followed by a near-tie between RegioJet and SBB; Eurostar is last. Jon Worth had to pour cold water on the conclusions and the stenography in various European newspapers about them.

In fact, the study fits so perfectly into my post about making up rankings that it is easy to think I wrote the post about T&E – but no, the post is from 2.5 years ago. The issue is that it came up with such bad weighting in judging railways that one is left to wonder if it specifically picked something that would sound truthy and put SBB at or near the top just to avoid raising too many questions. The criteria used are as follows:

- Ticket prices: 25%

- Special fares and reductions: 15%

- Reliability: 15%

- Booking experience: 15%

- Compensation policies: 10%

- Traveler experience (speed and comfort): 10%

- Night trains and bicycle policy: 5%

None of this is even remotely defensible, and none of this passes any sanity check. No, it is not 1.5 times as important to have special reductions in fares for advance bookings or other forms of price discrimination as to have a combination of speed and comfort. The Shinkansen has fixed fares and is doing fine, thank you very much; SNCF’s own explanations of its airline-style yield management system portray it as a positive but not essential feature – its reports from 2009 recommending high-speed rail development in the United States cite yield management as a 4% increase in revenue, which is good but not amazing.

But more broadly, it is daft to set a full 50% of the weight on fares and fare-related issues (i.e. compensation), and 15% on the booking experience, and relegate speed to part of an issue that is only 10%. That’s not how high-speed rail ridership works. Cascetta-Coppola find a ridership elasticity with respect to trip time of about -2, but only -0.37 with respect to fares. Börjesson finds a much narrower spread, -1.12 and -0.67 respectively, but still the same directionally. Speed matters.

And yet, T&E doesn’t seem to care. The best hints for the reason why are in the way it compares operators rather than national networks, and relies on a McKinsey report pitched at private entrants and not at member state policymakers, who do not normally outsource decisionmaking to international consultants. It doesn’t think in terms of systems or networks, because it isn’t trying to make a pitch at how a member state can improve its rail network, but rather at how a private competitor should aim to make a profit on infrastructure built previously by the state.

The need for state planning

Every intercity rail network worth its name was built and planned publicly, by a state empowered to do so. In East Asia, this comprises the high-speed rail networks of China, Japan, Korean, and Taiwan, all funded publicly, even if Japan subsequently privatized Shinkansen operation (though not construction) to regional monopolies that, while investor-owned, are too prestigious to fail. In Europe, some networks have high-speed rail at their core, like France, and others don’t, like Switzerland or the Netherlands, but the latter instead optimize state planning at lower speed, with tightly timed connections, strategic investments to speed up bottlenecks, and integration between rolling stock, the timetable, and infrastructure.

This feature of the main low-speed European rail network frustrates some attempts at disaggregating the effects of different inputs on ridership and revenue. At the level of a sanity check, there does not appear to be a noticeable malus to French rail ridership from its low frequency at outlying stations. But then France relies on one-seat rides from Paris to rather small cities, which do not have convenient airport access, and in its own way integrates this operating paradigm with rolling stock (bilevels optimized for seating capacity, not fast egress or acceleration) and infrastructure (bypasses around intermediate cities, even Lyon). Switzerland, in contrast, has these timed connections such that the effective frequency even on three-seat rides is hourly, with guaranteed short waits at the transfers, and this provides an alternative way to connect small cities with not just large ones but also each other.

But in both cases, the operating paradigm is connected with the infrastructure, and this was decided publicly by the state, based on governmental financial constraints, imposed in the 1970s in France (leading to extraordinarily low construction costs for the LGV Sud-Est) and the 1980s in Switzerland (leading to the hyper-optimized operations of Bahn 2000 in lieu of a high-speed rail system). A private operator can come in, imitate the same paradigm that the infrastructure was built for, and sometimes achieve lower operating costs by being more aggressive about eliminating redundant positions that a state operator may feel too constrained by unions to. But it cannot innovate in how to run trains. Even in Italy and Spain, where private competition has led to lower fares and higher ridership, all the private competitors have done is force service to look more like the TGV as it is and less like the TGV as SNCF management would like it to be internationally. Even there, they do not innovate, but merely imitate what the TGV already had purely publicly, on infrastructure that was designed for TGV or ICE service intensity all along.

The idea that the private sector can innovate in intercity rail comes from the same imitation of airline thinking that led to the failure of Eurostar, with its high fares and airline-style boarding and queuing. In the airline business, integration between infrastructure and operations is weak, and private airlines can innovate in aircraft utilization, fast boarding, no-frills service, and other aspects that led low-cost carriers to success. Business analysts drawn from that world keep trying to make this work for trains, and fail; the Spinetta Report mentions that OuiGo tanked TGV revenues, and ridership did not materially increase when it was introduced due to inconveniences imposed by the system of segmenting the market by fare.

Europe’s decision not to build high-speed rail

In the 2000s, there was semi-official crayon, such as the TEN-T system, for EU-wide high-speed rail, inspired by the success of the TGV. Little of it happened, and by the 2010s, it became more common to encounter criticism alleging that it could not be done, and it was more important to focus on other things – namely, private competition, the thing that cannot innovate in rail but could in airlines.

At no point was there a formal decision not to build high-speed rail at a European scale. Projects just fell aside, unless they were megaproject tunnels across mountains like the Brenner Base Tunnel or water like the Fehmarn Belt Tunnel, and then there is underinvestment in the approaches, so that the average speed remains shrug-worthy. The discourse shifted from building infrastructure to justifying not building it and pitching on-rail competition instead. This, I believe, is due to factors going back to the 1990s:

- The failure of Eurostar to produce high ridership. It underperformed expectations; it also underperforms domestic city pairs. SNCF is happy to collect monopoly profits from international travelers, and, in turn, potential travelers associate high-speed rail with high fares and inconvenience and look elsewhere. One failed prominent project can and does poison the technology, potentially indefinitely.

- The anti-state zeitgeist at the EU level. This can be described as neoliberalism, but the thoroughly neoliberal Blair/Brown and Cameron cabinets happily planned High Speed 2. The EU goes beyond that: it is too scared to act as a state on matters other than trade, and that leads people in EU policy to think in terms of government-by-nudge, rather like the Americans.

- SNCF and DB’s profiteering off of cross-border travelers in different ways turns them into Public Enemies #1 and #2 for people who travel between different member states by rail, who are then reluctant to see them as successes domestically.

For all of these reasons, it’s preferred at the level of EU policymaking and advocacy not to build infrastructure. Infrastructure requires there to be a public sector, and the EU only does that on matters of trade and regulatory harmonization.

Jon Worth has done a lot of work on getting a passenger rights clause into the agenda for the new EU Parliament, to deal with friction between DB and SNCF when each blames the other when a cross-border passenger is stranded (roughly: DB blames SNCF for running low frequencies so that if DB’s last train is delayed the passenger is stranded, SNCF blames DB for being so delayed in the first place). This is a good kind of regulatory harmonization. It reminds me of the EU’s role in health care: there’s reciprocity among the universal health care systems of Europe, for example allowing EU immigrants but not non-European ones to switch to the Kasse upon arrival; but at the same time, the EU has practically no role in designing or providing these universal health care system or even, as the divergent responses to corona showed in 2020, in coordinating non-pharmaceutical interventions for public health in a pandemic.

But health care does not require large coordinating bodies, and infrastructure does. Refugee camps tended to by UN agencies that have to pay bribes and protection fees to local gangs can have surprisingly good health care outcomes. Cox’s Bazar’s Rohingya camps have infant mortality rates comparable to those of Bangladesh and Burma; Gaza had good if worse-than-Israeli life expectancy and infant mortality until the war started. But nobody can build infrastructure this way. Top-down state action is needed to coordinate, which means actual infrastructure construction, not just passenger rights.

The thinking at the EU level is that greater on-rail competition can improve service quality. But that’s just a form of denial. The EU has no willingness to actually build the high-speed rail segments required to enable rail trips across borders, and so various anti-state actors, most on the center-to-center-right but not all, lie to themselves that it’s okay, that if the EU fails to act as a state then the private sector can step in if allowed to. That’s where the T&E study comes in: it rates operators on how to act like a competitive flight level-zero airline, going with this theory of private-sector innovation to cope with the fact that cross-border rail isn’t being built and try to salvage something out of it.

But it can’t be salvaged, not in this field; the best the private sector can do is provide equivalent service to a good state service on infrastructure that the state built. The alternative to the state is not greater private initiative. In infrastructure, the political alternative is that people who are not Green voters, which group comprises 92.6% of the European Parliament, are going to just drive and fly and associate low-carbon transportation with being contained to within biking distance of city center. The economic alternative is that ties between European cities will remain weak, to the detriment of the European economy and its ability to scale up.

We Have Northeast Corridor Runtimes

After finally looking at the options, we have a main low-investment proposal; the writeup will appear soon (optimistically this month, pessimistically next month). Here is the timetable for the fastest intercity trains:

Boston 0:00

Providence 0:23

New Haven 1:04

Stamford 1:30

New York 1:56 (arrival)

New York 1:59 (departure)

Newark 2:07

Philadelphia 2:46

Wilmington 3:00

Baltimore 3:32

Washington 3:55

This timetable incorporates schedule padding, of 4% on the Providence-New Haven section (dedicated to high-speed trains except at the north end with marginal commuter traffic) and 7% on the others. All station stops except New York take 1 minute, and the times above except that for Boston denote arrival time, not departure time.

This includes some nonnegotiable investments into reliability and capacity, such as switch upgrades within footprint at the major stations to raise speeds from 10 miles an hour to around 50 km/h and grade separations of some rail junctions near New York and Philadelphia; this post describes the main ones and is largely still valid. As far as big deviations from the existing Northeast Corridor right-of-way go, there’s only one: the bypass between Kingston and New Haven, saving around 27 minutes of trip time. None of the New Haven Line bypasses and curve easements on the webtool map has made it, except at Cos Cob Bridge, which should be turned from two short, sharp curves into one wider curve as it is replaced.

The menu of options of what to do with the corridor further, with speed impacts, is as follows:

- If the other long non-shared sections are timetabled with 4% and not 7% padding – New Haven-Stamford and New Brunswick-Perryville – then this saves, respectively, 43 and 93 seconds. But I am uncomfortable with this little timetable padding when these sections are directly adjacent to complex commuter rail track-sharing arrangements around New York and in Maryland.

- Restoring the Back Bay stop costs 107 seconds. Restoring the Route 128 stop costs 187 seconds. These and all subsequent figures include padding.

- There are a bunch of 1,746 m radius curves between the Canton Viaduct (which is very difficult to move) and Mansfield, all short and without difficult terrain or property on their inside; easing all of them to allow 320 km/h cruise speed saves 63 seconds.

- A New London stop for local intercity trains, in the middle of high-speed territory, costs 3:58; this should be padded to 5 minutes to space trains correctly to Boston, under a service pattern where out of every three trains going up to New Haven every 30 minutes, one runs express to Boston, one runs local, and one goes up to Hartford and Springfield.

- A rather destructive Milford curve easement saves 22 seconds (with 7% pad, not 4%), at the cost of four entire condo buildings near the station, 20 single-family houses, and most of Green Apartments; we do not recommend this even in a high-investment scenario due to the small time saving.

- A curve easement in Stratford taking some back space near the Walmart would by itself save 8 seconds, but the saving grows if adjacent curve fixes are conducted, for example, if the Milford curve easement is included, the saving is not 8 but 14 seconds, with intercity trains going at 240 km/h.

- A bypass complex for the curves of Bridgeport and Fairfield, including a tunnel under the Pequonnock, saves 2:54. The same bypass raises the time saving of the above Stratford curve by another 11 seconds, so combined they are 3:13, and the Milford easement would cut another 28 seconds.

- Trains can skip Stamford, saving 2:15.

- A destructive bypass of Darien would save 2:14, with trains running at 250 km/h, with around 300 properties taken, about as many as on the eight times as long Kingston-New Haven bypass. This figure assumes that trains continue to stop at Stamford. If the bypass is combined with skipping Stamford on express trains, then then are an extra 11 seconds saved.

- A bypass of Greenwich and Port Chester’s tight curves saves 63 seconds, and also changes the way intercity trains have to be timetabled with express commuter trains; whereas the default option without this bypass requires express trains to run as today and local trains to make all stops, the bypass forces express trains to stop at a rebuilt Greenwich station to be overtaken by intercity trains that use the bypass.

- A series of curve easements at Metuchen, not included in the plan, saves around 6 seconds and is not included.

- Trains could stop at Trenton, at the cost of 3:52 minutes. This could potentially be padded to 5 minutes to space trains south of Philadelphia correctly, if a train in three diverts at Philadelphia to the Keystone corridor.

- Trains could bypass Wilmington. On the current alignment, it only saves 1:44 due to sharp curves at both ends of the station, but if a bypass alignment near I-95 and the freight bypass is built, then trains would save about 3:20 compared with stopping trains.

- A bypass of BWI or realignment, including moving the station and the access road and parking garage, would save 15 seconds.

TGV Imitators: Learning the Wrong Lessons From the Right Places

I talked last time about how high-speed rail in Texas is stuck in part because of how it learned the wrong lessons from the Shinkansen. That post talks about several different problems briefly, and here I’d like to develop one specific issue I see recur in a bunch of different cases, not all in transportation: learning what managers in a successful case say is how things should run, rather than how the successful case is actually run. In transportation, the most glaring case of learning the wrong lessons is not about the Shinkansen but about the TGV, whose success relies on elements that SNCF management was never comfortable with and that are the exact opposite of what has been exported elsewhere, leading countries that learned too much from France, like Spain, to have inferior outcomes. This also generalizes to other issues, such as economic development, leading to isomorphic mimicry.

The issue is that the TGV is, unambiguously, a success. It has produced a system with high intercity rail ridership; in Europe, only Switzerland has unambiguously more passenger-km/capita (Austria is a near-tie, and the Netherlands doesn’t report this data). It has done so financially sustainably, with low construction costs and, therefore, operating profits capable of paying back construction costs, even though the newer lines have lower rates of return than the original LGV Sud-Est.

This success brought in imitators, comprising mostly countries that looked up to France in the 1990s and 2000s; Germany never built such a system, having always looked down on it. In the 2010s and 20s, the imitation ceased, partly due to saturation (Spain, Italy, and Belgium already had their own systems), partly because the mediocre economic growth of France reduced its soft power, and partly because the political mood in Europe shifted from state-built infrastructure projects to on-rail private competition. I wrote three years ago about the different national traditions of building high-speed rail, but here it’s best to look not at the features of the TGV today but at those of 15 years ago:

- High average speed, averaging around 230 km/h between Paris and Marseille; this was the highest in the world until China built out its own system, slightly faster than the Shinkansen and much faster than the German, Korean, and Taiwanese systems. Under-construction lines that have opened since have been even faster, reaching 260 km/h between Paris and Bordeaux.

- Construction on cut-and-fill, with passenger-only lines with steep grades (a 300 km/h train can climb 3.5% grades just fine), limited use of viaducts and tunnels, and extensive public outreach including land swap deals with farmers and overcompensation of landowners in order to reduce NIMBY animosity.

- Direct service to the centers of major cities, using classical lines for the last few kilometers into Paris and most other major cities; cities far away from the network, such as Toulouse and Nice, are served as well, on classical lines with the trains often spending hours at low speed in addition to their high-speed sections.

- Extensive branching: every city of note has its own trains to Paris.

- Little seat turnover: trains from Paris to Lyon do not continue to Marseille and trains from Paris to Marseille do not stop at Lyon, in contrast with the Shinkansen or ICE, which rely on seat turnover and multiple major-city stops on the same train.

- Open platforms: passengers can get on the platform with no security theater or ticket gates, and only have to show their ticket on the train to a conductor. This has changed since, and now the platforms are increasingly gated, though there is still no security theater.

- No fare differentiation: all trains have the same TGV brand, and charge similar fares as the few remaining slow intercity trains, on average much lower than on the Shinkansen. Fares do depend on airline-style buckets including when and how one books a train, and on service class, but there is no premium for speed or separation into high- and low-fare trains. This has also changed since, as SNCF has sought to imitate low-cost airlines and split the trains into the high-fare InOui brand and low-fare OuiGo brand, differentiated in that OuiGo sometimes doesn’t go into traditional city stations but only into suburban ones like Marne-la-Vallée, 25 minutes from Paris by RER. However, InOui and OuiGo are still not differentiated by speed.

SNCF management’s own beliefs on how trains should operate clearly differ from how TGVs actually did operate in the 1990s and 2000s, when the system was the pride of Europe. Evidently, they have introduced fare differentiation in the form of the InOui-OuiGo distinction, and ticket-gated the platforms. The aim of OuiGo was to imitate low-cost airlines, one of whose features is service at peripheral airports like Beauvais or Stansted, hence the use of peripheral train stations. However, even then, SNCF has shown some flexibility: it is inconvenient when a train unloads 1,000 passengers at an RER station, most of whom are visitors to the region and do not have a Navigo card and therefore must queue at ticket vending machines just to connect; therefore, OuiGo has been shifting to the traditional Parisian terminals.

However, the imitators have never gotten the full package outlined above. They’ve made some changes, generally in the direction of how SNCF management and the consultants who come from that milieu think trains ought to run, which is more like an airline. The preference for direct trains and no seat turnover has been adopted into Spain and Italy, and the use of classical lines to go off-corridor has been adopted as well, not just into standard-gauge imitators but also into broad-gauge Spain, using some variable-gauge trains. In contrast, the lack of fare differentiation by speed did not make it to Spain. Fast trains charge higher fares than slow trains, and before the opening of the market to private competition, RENFE ran seven different fare/speed classes on the Madrid-Barcelona lines, with separate tickets.

Ridership, as a result, was disappointing in Spain and Italy. The TGV had around 100 million annual passengers before the Great Recession, and is somewhat above that level today, thanks to the opening of additional lines. The AVE system has never been close to that. The high-speed trains in Italy, a country with about the same population as France, have been well short of the TGV’s ridership as well. Relative to metro area size, ridership in both countries on the city pairs for which I can find data was around half as high as on the TGV. Private competition has partly fixed the problem on the strongest corridors, but nationwide ridership in Spain and Italy remains deficient.

The issue in Spain in particular is that while the construction efficiency is even better than in France, management bought what France said trains should be like and not what French trains actually are. The French rail network is not the dictatorship of SNCF management. Management has to jostle with other interest groups, such as labor, NIMBY landowners, socialist politicians, (right-)liberal politicians, and EU regulators. It hates all of those groups for different reasons and can find legitimate reasons why each of those groups is obstructionist, and yet at least some of those groups are evidently keeping it honest with its affordable fares and limited market segmentation (and never by speed).

More generally, when learning from other places, it’s crucial not just to invite a few of their managers to your country to act as consultants. As familiar as they are with their own success, they still have their prejudices of how things ought to work, which are often not how they actually do work. Experience in the country in question is crucial; if you represent a peripheral country, you need to not just rely on consultants from a success case but also send your own people there to live as locals and get local impressions of how things work (or don’t), so that you can get what the success case actually is.

Why Texas High-Speed Rail is Stuck

I’ve been asked on social media why the US can’t build a Shinkansen-style network, with a specific emphasis on Texas. There is an ongoing project, called Texas Central, connecting Dallas with Houston, using Shinkansen technology; the planning is fairly advanced but the project is unfunded and predicted to cost $33.6 billion for a little less than 400 km of route in easy terrain. Amtrak is interested, but it doesn’t seem to be a top priority for it. I gave the skeet-length answer centering costs, blaming, “Farm politics, prior commitments, right-wing populism, and Japanese history.” These all help explain why the project is stuck, despite using technology that in its home country was a success.

How Texas Central is to be constructed

The line is planned to run between Dallas and Houston, but the Houston station is not in Downtown Houston, in order to avoid construction in the built-up area. There are rail corridors into city center, but Texas Central does not want to use them; the concept, based on the Shinkansen, does not permit sharing tracks with legacy railways, and as it developed in the 2010s, it did not want to modify the system for that. Sharing the right-of-way without sharing tracks is possible, but requires new construction within the built-up area. To avoid spending this money, the Texas Central plan is for the Houston station to be built at the intersection of I-610 and US 290, 9 km from city center. Between the cities, the line is not going into intermediate urban areas; a Brazos Valley stop is planned as a beet field station 40 km east of College Station.

Despite all this cost cutting, the line is also planned to run on viaducts. This is in line with construction norms on the newer Shinkansen lines as well as in the rest of Asia; in Europe, high-speed rail outside tunnels runs at-grade or on earthworks, and viaducts are only used for river crossings. As a result, on lines with few tunnels, construction is usually more expensive in Asia than in Europe, with some notable exceptions like High Speed 2 or HSL Zuid. Heavily-tunneled lines sometimes exhibit the opposite, since Japanese standards permit narrower tunnels (more precisely, a slightly wider tunnel accommodates two tracks whereas elsewhere the norm is that each track goes in a separate bore); this works because the Shinkansen trainsets are more strongly pressurized than TGVs or ICEs and also have specially designed noses to reduce tunnel boom.

But in an environment like Texas’s, the recent norm of all-elevated construction drives up costs. This is how, in an easy construction environment, costs have blown to around $87 million/km. For one, recently-opened Shinkansen extensions have cost less than this even while being maybe half or even more in tunnel (that said, the Tsuruga extension that opened earlier this year cost much more). But it’s not the only reason; the construction method interacts poorly with the state’s politics and with implicit and explicit promises made too early.

Japanese history and turnkey projects

The Shinkansen is successful within Japan, and has spawned imitators and attempts at importing the technology wholesale. The imitators have often succeeded on their own terms, like the TGV and the KTX. The attempts at importing the technology wholesale, less so.

The issue here is twofold. First, state railways that behave responsibly at home can be unreasonable abroad. SNCF is a great example, running the TGV at a consistent but low profit to keep ticket fares affordable domestically but then extracting maximum surplus as a monopolist charging premium fares on Eurostar and Thalys. Japan National Railways, now the JR group, is much the same. Domestically, it is constrained by not just implicit expectations of providing a social service (albeit profitably) but also local institutions that push back against some of management’s thinking about how things ought to be. With SNCF, it’s most visible in how management wants to run the railway like an airline, but is circumscribed by expectations such as open platforms, whereas on Eurostar it is freer to force passengers to wait until the equivalent of an airline gate opens. With JR, it’s a matter of rigidity: the Shinkansen does run through to classical lines on the Mini-Shinkansen, but it’s considered a compromise, which is not to be tolerated in the idealized export product.

And second, the history of Taiwan High-Speed Rail left everyone feeling a little dirty, and led Japan to react by insisting on total turnkey products. THSR, unlike the contemporary KTX or the later CRH network, was not run on the basis of dirigistic tech transfers but on that of buying imported products. To ensure competition, Taiwan insisted on designing the infrastructure to accommodate both Japanese and European trains; for example, the tunnels were built to the larger European standard. There were two bidders, the Japanese one (JRs do not compete with one another for export orders) and a Franco-German one called the Eurotrain, coupling lighter TGV coaches to the stronger motor of the ICE 2.

The choice between the two bids was mired in the corruption typical of 1990s Taiwan. The Taiwanese government relied on external financing, and Japan offered financing just to get the built-operate-transfer consortium allied with the Eurotrain to switch to the Shinkansen. Meetings with European and Japanese politicians hinged on other scandals, such as the one for the frigate purchase. Taiwan eventually chose the Shinkansen, using a variant of the 700 Series called the 700T, but the Eurotrain consortium sued alleging the choice was improperly made, and was awarded a small amount of damages including covering the development cost of the train.

The upshot is that in the last 20 years, a foreign country buying Shinkansen tech has had to buy the entire package. This includes not just the trainsets, which are genuinely better than their European and Chinese counterparts, but also construction standards (at this point all-elevated) and signaling (DS-ATC rather than the more standard ETCS or its Chinese derivative CTCS). It includes the exact specifications of the train, unmodified for the local loading gauge; in India, this means that the turnkey Shinkansen used on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad line is not only on standard gauge rather than broad gauge, but also uses the dimensions of the Shinkansen, 3.36 m wide trains with five-abreast seating, rather than those of Indian commuter lines, 3.66 m with six-abreast seating. It’s unreasonably rigid and yet Japan finds buyers who think that this lets them have a system as successful as the Shinkansen, rather than one component of it, not making the adjustments for local needs that Japan itself made from French and German technology in the 1950s and 60s when it developed the Shinkansen in the first place.

Prior commitments

Texas Central began as a private consortium; JR Central saw it as a way of selling an internationalized eight-car version of the N700 Series, called the N700-I. It developed over the 2010s, as Republican governors were canceling intercity rail projects that they associated with the Obama administration, including one high-speed one (Florida) and two low-speed ones (Ohio, Wisconsin). As a result, it made commitments to remain a private-sector firm, to entice conservative politicians in Texas.

One of the commitments was to minimize farmland takings. This was never a formal commitment, but one of the selling points of the all-elevated setup is that farmers can drive tractors underneath the viaducts, and only the land directly beneath the structures needs to be purchased. At-grade construction splits plots; in France, this is resolved through land swap agreements and overcompensation of farmers by 30%, but this has not yet been done in the United States or in Japan.

Regular readers of this blog, as well as people familiar with the literature on cost overruns, will recognize the problem as one of early commitment and lock-in. The system was defined early as one with features including very limited land takings and no need for land swaps, no interface with existing railroads to the point that the Houston terminal is not central, and promises of external funding and guidance by JR Central. This circumscribed the project and made it difficult to switch gears as the funding situation changed and Amtrak got more interested, for one.

Farm politics and right-wing populism

Despite the promises of private-sector action and limited takings, not everyone was happy. Texas Central is still a train; in a state with the politics of Texas, enough people are against that on principle. The issue of takings looms large, and features heavily in the communications of Texans Against High-Speed Rail.

The combination of this politics and prior commitments made by Texas Central has been especially toxic to the project. Under American law, private railroads are allowed to expropriate land for construction, and only the federal government, not the states, is allowed to expropriate railroads. Texas Central intended to use this provision to assemble land for its right-of-way, leading to lawsuits about whether it can legally be defined as a railroad, since it doesn’t yet operate as one.

Throughout the 2010s, Governor Greg Abbott supported the project, on the grounds that he’s in favor of private-sector involvement in infrastructure and Texas Central is private-sector. But his ability to support it has always been circumscribed by this political opposition from the right. The judicial system ruled in favor of Texas Central, but state legislative sessions trying to pass laws in support of the project were delayed, and relying on Abbott meant not seeking federal funds.