Category: Incompetence

Stop Imitating the High Line

I streamed a longer version of this on Twitch on Tuesday, but the recording cut out, so instead of uploading to YouTube as a vlog, I’m summarizing it here

Manhattan has an attractive, amply-used park in the Meatpacking District, called the High Line. Here it is, just west of 10th Avenue:

It was originally a freight rail branch of the New York Central, running down the West Side of Manhattan to complement the railroad’s main line to Grand Central, currently the Harlem Line of Metro-North. As such, it was a narrow el with little direct interface with the neighborhood, unlike the rapid transit els like that on Ninth Avenue. The freight line was not useful for long: the twin inventions of trucking and electrification led to the deurbanization of manufacturing to land-intensive, single-story big box-style structures. Thus, for decades, it lay unused. As late as 2007, railfans were dreaming about reactivating it for passenger rail use, but it was already being converted to a park, opening in 2009. The High Line park is a successful addition to the neighborhood, and has spawned poor attempt at imitation, like the Low Line (an underground rapid transit terminal since bypassed by the subway), the Queensway (a similar disused line in Central Queens), and some plans in Jersey City. So what makes the High Line so good?

- The neighborhood, as can be seen above in the picture, has little park space. The tower-in-a-park housing visible to the east of the High Line, Chelsea-Elliott Houses, has some greenery but it’s not useful as a neighborhood park. The little greenery to the west is on the wrong side of 12th Avenue, a remnant of the West Side Highway that is not safe for pedestrians to cross, car traffic is so fast and heavy. Thus, it provides a service that the neighborhood previously did not have.

- The area has very high density, both residential and commercial. Chelsea is a dense residential neighborhood, but at both ends of the line there is extensive commercial development. Off-screen just to the south, bounded by Eighth, Ninth, 15th, and 16th, is Google’s building in New York, with more floor area than the Empire State Building and almost as much as One World Trade Center. Off-screen just to the north is the Hudson Yards development, which was conceived simultaneously with the High Line. This guarantees extensive foot traffic through the park.

- The linear park is embedded in a transit-rich street grid. Getting on at one end and off at the other is not much of a detour to the pedestrian tourist, or to anyone with access to the subway near both ends, making it a convenient urban trail.

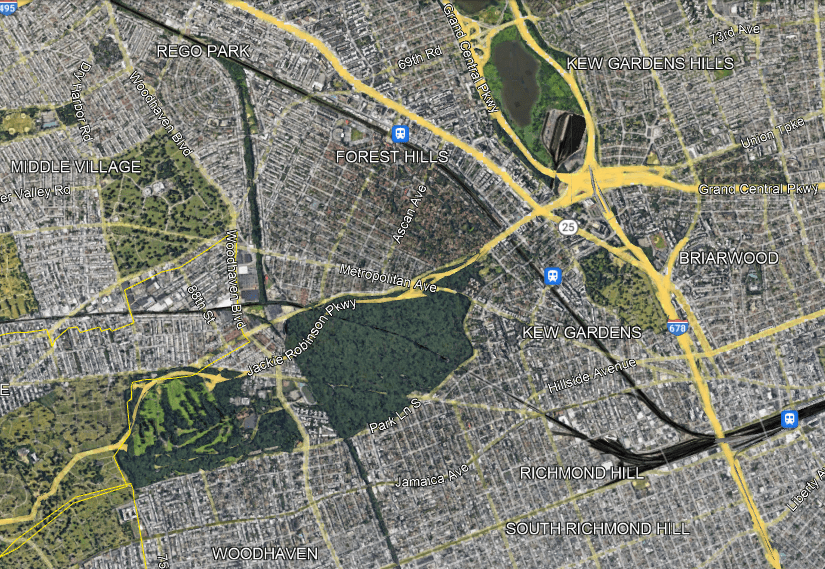

These three conditions are not common, and trying to replicate the same linear park in their absence is unlikely to produce good results. For example, consider the Rockaway Cutoff, or Rockaway Beach Branch:

The Cutoff has two competing proposals for what to do with this disused LIRR branch: the Queenslink, aiming to convert it to a rapid transit branch (connecting to the subway, not the LIRR), and the Queensway, aiming to convert it to a linear park. The Queenslink proposal is somewhat awkward (which doesn’t mean it’s bad), but the Queensway one is completely drunk. Look at the satellite photo above and compare to that of the High Line:

- The area is full of greenery and recreation already, easily accessible from adjoining areas. Moreover, many residents live in houses with backyards.

- The density is moderate at the ends (Forest Hills and Woodhaven) and fairly low in between, with all these parks, cemeteries, and neighborhoods of single-family houses and missing middle density. Thus, local usage is unlikely to be high. Nor is this area anyone’s destination – there are some jobs at the northern margin of the area along Queens Boulevard (the wide road signed as Route 25 just north of the LIRR) but even then the main job concentrations in Queens are elsewhere.

- There is no real reason someone should use this as a hiking trail unless they want to hike it twice, one way and then back. The nearest viable parallel transit route, Woodhaven, is a bus rather than a subway.

The idea of a park is always enticing to local neighborhood NIMBYs. It’s land use that only they get to have, designed to be useless to outsiders; it is also at most marginally useful to neighborhood residents, but neighborhood politics is petty and centers exclusion of others rather than the actual benefits to residents, most of whom either don’t know their self-appointed neighborhood advocates or quietly loathe them and think of them as Karens and Beckies. Moreover, the neighborhood residents don’t pay for this – it’s a city project, a great opportunity to hog at the trough of other people’s money. Not for nothing, the Queensway website talks about how this is a community-supported solution, a good indication that it is a total waste of money.

But in reality, this is not going to be a useful park. The first park in a neighborhood is nice. The second can be, too. The fifth is just fallow land that should be used for something more productive, which can be housing, retail, or in this case a transportation artery for other people (since there aren’t enough people within walking distance of a trail to justify purely local use). The city should push back against neighborhood boosters who think that what worked in the Manhattan core will work in their explicitly anti-Manhattan areas, and preserve the right-of-way for future subway or commuter rail expansion.

It’s Easy to Waste Money

As we’re finalizing edits on our New York and synthesis reports, I’m rereading about Second Avenue Subway. In context, I’m stricken by how easy it is to waste money – to turn what should be a $600 million project into a $6 billion one or what should be a $3 billion project into a $30 billion one. Fortunately, it is also not too hard to keep costs under control if everyone involved with the project is in on the program and interested in value engineering. Unfortunately, once promises are made that require a higher budget figure, getting back in line looks difficult, because one then needs to say “no” to a lot of people.

This combination – it’s easy to stay on track, it’s easy to fall aside, it’s hard to get back on track once one falls aside – also helps explain some standard results in the literature about costs. There’s much deeper academic literature about cost overruns than absolute costs; the best-known reference is the body of work of Bent Flyvbjerg about cost overruns (which in his view are not overruns but underestimations – i.e. the real cost was high all along and the planners just lied to get the approval), but the work of Bert van Wee and Chantal Cantarelli on early commitment as a cause of overruns is critical to this as well. In van Wee and Cantarelli, once an extravagant promise is made, such a 300 km/h top speed on Dutch high-speed rail, it’s hard to walk it back even if it turns out to be of limited value compared with its cost. But equally, there are examples of promises made that have no value at all, or sometimes even negative value to the system, and are retained because of their values to specific non-state actors, such as community advocacy, which are incorrectly treated as stakeholders rather than obstacles to be removed.

In our New York report, we include a flashy example of $20 million in waste on the project: the waste rock storage chamber. The issue is that tunnel-boring machines (TBMs) in principle work 24/7; in practice they constantly break down (40% uptime is considered good) and require additional maintenance, but this can’t be predicted in advance or turned into a regular cycle of overnight shutdowns, and therefore, work must be done around the clock either way. This means that the waste rock has to be hauled out around the clock. The agency made a decision to be a good neighbor and not truck out the muck overnight – but because the TBM had to keep operating overnight, the contractor was required to build an overnight storage chamber and haul it all away with a platoon of trucks in the morning rush hour. The extra cost of the chamber and of rush hour trucking was $20 million.

Another $11 million is surplus extraction at a single park, the Marx Brothers Playground. As is common for subway projects around the world, the New York MTA used neighborhood parks to stage station entrances where appropriate. Normally, this is free. However, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation viewed this as a great opportunity to get other people’s money; the MTA had to pay NYC Parks $11 million to use one section of the playground, which the latter agency viewed as a great success in getting money. Neither agency viewed the process as contentious; it just cost money.

But both of these examples are eclipsed by the choice of construction method for the stations. Again in order to be a good neighbor, the MTA decided to mine two of the project’s three stations, instead of opening up Second Avenue to build cut-and-cover digs. Mined stations cost extra, according to people we’ve spoken to at a number of agencies; in New York, the best benchmark is that these two stations cost the same as cut-and-cover 96th Street, a nearly 50% longer dig.

Moreover, the stations were built oversize, for reasons that largely come from planner laziness. The operating side of the subway, New York City Transit, demanded extravagant back-of-the-house function spaces, with each team having its own rooms, rather than the shared rooms typical of older stations or of subway digs in more frugal countries. The spaces were then placed to the front and back of the platform, enlarging the digs; the more conventional place for such spaces is above the platform, where there is room between the deep construction level and the street. Finally, the larger of the two station, 72nd Street, also has crossovers on both sides, enlarging the dig even further; these crossovers were included based on older operating plans, but subsequent updates made them no longer useful, and yet they were not descoped. Each station cost around $700 million, which could have been shrunk by a factor of three, keeping everything else constant.

Why are they like this?

They do not care. If someone says, “Give me an extra,” they do not say, “no.” It’s so easy not to care when it’s a project whose value is so obvious to the public; even with all this cost, the cost per rider for Second Avenue Subway is pretty reasonable. But soon enough, norms emerge in which the appearance of neighborhood impact must always be avoided (but the mined digs still cause comparable disruption at the major streets), the stations must be very large (but passengers still don’t get any roomy spaces), etc. Projects that have less value lose cost-effectiveness, and yet there is no way within the agency to improve them.

Who Through-Running is For

Shaul Picker is working on an FAQ for the benefit of people in the New York area about the concept of commuter rail through-running and what it’s good for. So in addition to contributing on some specific points, I’d like to step back for a moment and go over who the expected users are. This post needs to be thought of as a followup from what I wrote a month ago in which I listed the various travel markets used by modern commuter rail in general, making the point that this is a predominantly urban and inner-suburban mode, in which suburban rush hour commuters to city center are an important but secondary group, even where politically commuter rail is conceived of as For the Suburbs in opposition to the city, as in Munich. My post was about all-day frequency, but the same point can be made about the physical infrastructure for through-running, with some modifications.

The overall travel markets for regional rail

The assumption throughout is that the city region has with a strong center. This can come from a few square kilometers of city center skyscrapers, as is the norm in the United States (for example, in New York, Chicago, or Boston, but not weaker-centered Los Angeles), or from a somewhat wider region with office mid-rises, as is the norm in European cities like Paris, Stockholm, Munich, Zurich, and Berlin. Berlin is polycentric in the sense of having different job centers, including Mitte, City-West at the Zoo, and increasingly Friedrichshain at Warschauer Strasse, but these are all within the Ring, and overall this inner zone dominates citywide destinations. In cities like this, the main travel markets for commuter rail are, in roughly descending order of importance,

- Urban commuter trips to city center

- Commuter trips to a near-center destination, which may not be right at the one train station of traditional operations

- Urban non-work trips, of the same kind as subway ridership

- Middle-class suburban commutes to city center at traditional mid-20th century work hours, the only market the American commuter rail model serves today

- Working-class reverse-commutes, not to any visible office site (which would tilt middle-class) but to diffuse retail, care, and service work

- Suburban work and non-work trips to city center that are not at traditional mid-20th century hours

- Middle-class reverse-commutes and cross-city commutes

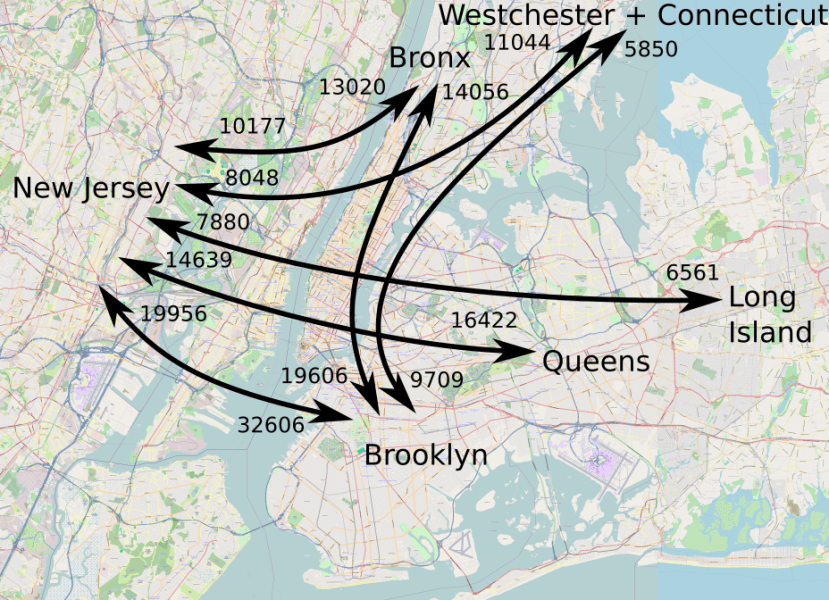

I center urban commuter trips because even in places with extensive suburbanization, commutes are more urban than suburban. Long Island, an unusually job-poor, commuter-oriented suburb, has 2.9 million people as of the 2020 census and, per OnTheMap, 191,202 Manhattan-bound commuters and 193,536 outer borough-bound commuters. Queens has 2.4 million people, 871,253 in-city commuters, 384,223 Manhattan-bound commuters, and 178,062 commuters to boroughs other than itself and Manhattan. The Metro-North suburbs – Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, and Fairfield Counties (New Haven omitted as it’s not really a suburb) – have 2.35 million people and 143,862 Manhattan-bound commuters and 79,821 outer borough-bound commuters. To work regionwide, commuter rail needs to be usable by the largest commute market; it’s urban rail that’s capable of also serving the suburbs without building suburban metro tunnels, rather than predominantly suburban rail.

Through-running

Through-running means that trains run from one side of the region to the other through city center, rather than terminating at a traditional city terminal. Rarely, this means running trains through a city center station that already has through-tracks, like Penn Station or Stockholm Central; usually, this requires building new tunnels to connect different terminals, as it would to get to Grand Central and as it did in the other European comparison cases.

This rearranges the travel markets for commuter rail, but only somewhat. The largest group, urban commuters to city center, shrinks somewhat: terminating trains to some extent already serve it. The qualifiers come from the fact that city center is rarely entirely within walking distance of the terminal; it is in Stockholm, but it’s small and I suspect the reason Stockholm’s monocentric CBD is walking distance from the intercity station is that it opened as a through-station in 1871 already. In Boston, most of the CBD is close to South Station, but much of it isn’t, and little is within walking distance of North Station. In New York, the CBD is large enough that service to multiple destinations is desirable when feasible, for example both East Side and West Side destinations in Midtown and even Lower Manhattan, requiring additional through-running commuter rail tunnels.

What really shines with through-running is urban trips that are not commutes, or are commutes to a near-center destination on the wrong side of the CBD (for example, south of it for commuters from Uptown Manhattan or the Bronx). New York is unusually asymmetric in that there’s much more city east of Manhattan than west of it, where there’s just the urban parts of Hudson County and Newark. But even there, New Jersey-Brooklyn and New Jersey-Queens commutes matter, as do Bronx-Brooklyn commutes.

Even then, the urban commutes are significant: there are 55,000 commuters from the Bronx to Manhattan south of 23rd Street. These in-city travel markets are viable by subway today, but are for the most part slow even on the express trains – the A train’s run from Inwood to Jay Street and the 4’s run from Woodlawn to Brooklyn Bridge are both scheduled to take 45 minutes for 22.5 km, an average speed of 30 km/h. And then the New Jersey-to-outer borough commutes are largely unviable by public transportation – they cost double because there’s no fare integration between PATH and the subway and the transfers are onerous and slow, and besides, PATH’s coverage of the urban parts of North Jersey leaves a lot to be desired.

Adapting the city

Berlin is in a way the most S-Bahn-oriented city I know of. It’s polycentric but all centers are within the Ring and close to either the Stadtbahn or (for Potsdamer Platz) the North-South Tunnel. This shouldn’t be surprising – the Stadtbahn has been running since the 1880s, giving the city time to adapt to it, through multiple regime changes, division, and reunification. Even Paris doesn’t quite compare – the RER’s center, Les Halles, is a retail but not job center, and the five-line system only has two CBD stops, the RER A’s Auber and the RER E’s Haussmann-Saint-Lazare.

Can New York become more like Berlin if it builds through-running? The answer is yes. Midtown would remain dominant, and overall the region would become less rather than more polycentric as better commuter rail service encouraged job growth in the Manhattan core. But it’s likely any of the following changes would grow the market for commuter rail to take advantage of through-running over time:

- Job growth in Lower Manhattan, which has struggled with office vacancy for decades

- Job growth in non-CBD parts of Manhattan that would become accessible, like Union Square, or even Midtown South around Penn Station, which is lower-rise than the 40s and 50s

- Job growth in near-center job centers – Downtown Brooklyn may see a revival, and Long Island City is likely to see a larger upswing than it is already seeing if it becomes more accessible from New Jersey and not just the city

- Residential location adjustment – Brooklyn workers may choose to depend on the system and live in the Bronx or parts of New Jersey with good service instead of moving farther out within Brooklyn or suburbanizing and driving to work

- Residential transit-oriented development near outlying stations, in urban as well as suburban areas

Berlin Greens Know the Price of Everything and Value of Nothing

While trying to hunt down some numbers on the costs of the three new U5 stations, I found media discourse in Berlin about the U-Bahn expansion plan that was, in effect, greenwashing austerity. This is related to the general hostility of German urbanists and much of the Green Party (including the Berlin branch) to infrastructure at any scale larger than that of a bike lane. But the specific mechanism they use – trying to estimate the carbon budget – is a generally interesting case of knowing the costs more certainly than the benefits, which leads to austerity. The underlying issue is that mode shift is hard to estimate accurately at the level of the single piece of infrastructure, and therefore benefit-cost analyses that downplay ridership as a benefit and only look at mode shift lead to underbuilding of public transport infrastructure.

The current program in Berlin

In the last generation, Berlin has barely expanded its rapid transit network. The priority in the 1990s was to restore sections that had been cut by the Berlin Wall, such as the Ringbahn, which was finally restored with circular service in 2006. U-Bahn expansion, not including restoration of pre-Wall services, included two extensions of U8, one north to Wittenau that had begun in the 1980s and a one-stop southward extension of U8 to Hermannstrasse, which project had begun in the 1920s but been halted during the Depression. Since then, the only fully new extension have been a one-stop extension of U2 to Pankow, and the six-stop extension of U5 west from Alexanderplatz to Hauptbahnhof.

However, plans for much more expansive construction continue. Berlin was one of the world’s largest and richest cities before the war, and had big plans for further growth, which were not realized due to the war and division; in that sense, I believe it is globally only second to New York in the size of its historic unrealized expansion program. The city will never regain its relative wealth or size, not in a world of multiple hypercities, but it is growing, and as a result, it’s dusting off some of these plans.

Most of the lines depicted in red on the map are not at all on the city’s list of projects to be built by the 2030s. Unfortunately, the most important line measured by projected cost per rider, the two-stop extension of U8 north (due east) to Märkisches Viertel, is constantly deprioritized. The likeliest lines to be built per current politicking are the extensions of U7 in both directions, southeast ti the airport (beyond the edge of the map) and west from Spandau to Staaken, and the one-stop extension of U3 southwest to Mexikoplatz to connect with the S-Bahn. An extension to the former grounds of Tegel is also considered, most likely a U6 branch depicted as a lower-priority dashed yellow line on the map rather than the U5 extension the map depicts in red.

The carbon critique

Two days after the U5 extension opened two years ago, a report dropped that accused the proposed program of climate catastrophe. The argument: the embedded concrete emissions of subway construction are high, and the payback time on those from mode shift is more than 100 years.

The numbers in the study are, as follows: each kilometer of construction emits 98,800 tons of CO2, which is 0.5% of city emissions (that is, 5.38 t/person, cf. the German average of about 9.15 in 2021). It’s expected that through mode shift, each subway kilometer saves 714 t-CO2 in annual emissions through mode shift, which is assumed to be 20% of ridership, for a payback time of 139 years.

And this argument is, frankly, garbage. The scale of the difference in emissions between cities with and without extensive subway systems is too large for this to be possibly true. The U-Bahn is 155 km long; if the 714 t/km number holds, then in a no U-Bahn counterfactual, Berlin’s annual greenhouse gas emissions grow by 0.56%, which is just ridiculous. We know what cities with no or minimal rapid transit systems look like, and they’re not 0.56% worse than comparanda with extensive rapid transit – compare any American city to New York, for one. Or look again at the comparison of Berlin to the German average: Berlin has 327 cars per 1,000 people, whereas Germany-wide it’s 580 and that’s with extensive rapid transit systems in most major cities bringing down the average from the subway-free counterfactual of the US or even Poland.

The actual long-term effect of additional public transport ridership on mode shift and demotorization has to be much more than 20%, then. It may well be more than 100%: the population density that the transit city supports also increases the walking commute modal split as some people move near work, and even drivers drive shorter distances due to the higher density. This, again, is not hard to see at the level of sanity checks: Europeans drive considerably less than Americans not just per capita but also per car, and in the United States, people in New York State drive somewhat shorter distance per car than Americans elsewhere (I can’t find city data).

The measurement problem

It’s easy to measure the embedded concrete of infrastructure construction: there are standardized itemized numbers for each element and those can be added up. It’s much harder to measure the carbon savings from the existence of a better urban rail system. Ridership can be estimated fairly accurately, but long-term mode shift can’t. This is where rules of thumb like 20% can look truthy, even if they fail any sanity check.

But it’s not correct to take any difficult to estimate number and set it to zero. In fact, there are visible mode shift effects from a large mass transit system. The difficulty is with attributing specific shifts to specific capital investments. Much of the effect of mode shift comes from the ability of an urban rail system to contribute to the rise of a strong city center, which can be high-rise (as in New York), mid-rise (as in Munich or Paris), or a mix (as in Berlin). Once the city center anchored by the system exists, jobs are less likely to suburbanize to auto-oriented office parks, and people are likelier to work in city center and take the train. Social events will likewise tend to pick central locations to be convenient for everyone, and denser neighborhoods make it easier to walk or bike to such events, and this way, car-free travel is possible even for non-work trips.

This, again, can be readily verified by looking at car ownership rates, modal splits (for example, here is Berlin’s), transit-oriented development, and so on, but it’s difficult to causally attribute it to a specific piece of infrastructure. Nonetheless, ignoring this effect is irresponsible: it means the carbon benefit-cost analysis, and perhaps the economic case as well, knows the cost of everything and the value of little, which makes investment look worse than it is.

I suspect that this is what’s behind the low willingness to invest in urban rail here. The benefit-cost analyses can leave too much value on the table, contributing to public transport austerity. When writing the Sweden report, I was stricken by how the benefit-cost analyses for both Citybanan and Nya Tunnelbanan were negative, when the ridership projections were good relative to costs. Actual ridership growth on the Stockholm commuter trains from before the opening of Citybanan to 2019 was enough to bring cot per new daily trip down to about $29,000 in 2021 PPP dollars, and Nya Tunnelbanan’s daily ridership projection of 170,000 means around $23,000/rider. The original construction of the T-bana cost $2,700/rider in 2021 dollars, in a Sweden that was only about 40% as rich as it is today, and has a retrospective benefit-cost ratio of between 6 and 8.5, depending on whether broader agglomeration benefit are included – and these benefits are economic (for example, time savings, or economic productivity from agglomeration) scale linearly with income.

At least Sweden did agree to build both lines, recognizing the benefit-cost analysis missed some benefits. Berlin instead remains in austerity mode. The lines under discussion right now are projected between 13,160€ and 27,200€ per weekday trip (and Märkisches Viertel is, again, the cheapest). The higher end, represented by the U6 branch to Tegel, is close to the frontier of what a country as rich as Germany should build; M18 in Paris is projected to be more than this, but area public transport advocates dislike it and treat it as a giveaway to rich suburbs. And yet, the U6 branch looks unlikely to be built right now. When the cost per rider of what is left is this low, what this means is that the city needs to build more infrastructure, or else it’s leaving value on the table.

How Sandbagged Costs Become Real

Sandbagging is the practice of making a proposal one does not wish to see enacted look a lot weaker than it is. In infrastructure, this usually takes the form of making the cost look a lot higher than it needs to be, by including extra scope, assuming constraints that are not in fact binding, or just using high-end estimates for costs and low-end estimates for benefits. Unfortunately, once a sandbagged estimate circulates, it becomes real: doing the project cleanly without the extras and without fake constraints becomes politically difficult, especially if the sandbaggers are still in charge.

Examples of sandbagging

I’ve written before about some ways Massachusetts sandbags commuter rail electrification and the North-South Rail Link. In both cases, Governor Charlie Baker and the state’s Department of Transportation are uninterested in commuter rail modernization and therefore ensured the studies in that direction would put their fingers on the scale to arrive at the desired conclusion. As we will see, the electrification sandbag is one example of how sandbagged estimates can become real.

In New York, the best example is of sandbagging alternatives. Disgraced then-governor Andrew Cuomo wanted to build a people mover to LaGuardia Airport in the wrong direction, and to that effect, Port Authority made a study that found ways to sandbag other alignments; here at least there’s a happy ending, in that as soon as Cuomo left office, the process was restarted and the rapid transit options studied the most seriously are the better ones.

Another example I have just seen is in Philadelphia. There have long been calls for extending the subway to the northeast along Roosevelt Boulevard; Pennsylvania DOT has just released a cost estimate of $1-4 billion/mile ($600 million-$2.5 billion/km). The high end would beat both phases of Second Avenue Subway, in an environment that both is objectively easier to tunnel in and has a recent history of building and operating services much less expensively than New York.

How to sandbag public transportation

An obstructionist manager who does not care much for public transit, or doesn’t care about the specific project being proposed, has a number of tools with which they can make costs appear higher and benefits appear lower. These are not hard to bake into an official proposal. These include the following:

- Invocation of NIMBYs as a reason not to build. The NIMBYs in question can be a complete phantom – perhaps the region in question is supportive of transit expansion, or perhaps there was NIMBYism in recent memory but the NIMBYs have since died or moved away. Or they can be real but far less powerful than the obstructionist says, with a recent history of the state beating NIMBYs in court when it cares.

- Scope creep. Complex public transportation projects often require additional scope to be viable – for example, regional rail tunnels often require additional spending on surface improvements for the branches that are to use the tunnels. How much extra scope is required is a subtle technical question and there is usually room for creative innovation for how to schedule around bottlenecks (whence the Swiss slogan electronics before concrete). The obstructionist can take a maximalist approach for the scope and just avoid any attempt to optimize, making the costs appear higher.

- Scope deflection. This is similar to scope creep in that the project gets laden with additional items, but differs from scope creep in that the items are what the obstructionist really wants to build, rather than lazy irrelevances.

- Excessive contingency. Cost estimates are uncertain and the earlier the design is, the more uncertain they are. Adding 40% contingency is a surefire way to ensure the money will be spent, as is citing a large range of costs as in the above-mentioned case in Philadelphia.

How sandbags become real

Normally, the purpose of a sandbag is to block or delay the entire project; the scope deflection point is an exception to this. And yet, once a sandbagged estimate is announced, it often turns into the real cost. Philadelphia was recently planning subway expansion for not much more than the international cost, but now that numbers comparable to Second Avenue Subway are out there, area advocates should expect them to turn into the real cost, absent a strong counterforce, involving public dismissal and humiliation of people engaged in such tactics.

The reason for this is that cost control doesn’t always occur naturally, unless one is already used to it. It’s very easy to waste money on irrelevant extras, some with real value to another group (“betterments”), some without. Second Avenue Subway has stations that are two to three times as big as they needed to be, without any sandbagging – different requirements just piled up, including mechanical rooms, crew rooms with each department having its own space, and additional crossovers, and nobody said “Wait a minute, this is too much.” The station designs are also not standardized, again without a sandbag, and it’s very easy to promise neighborhood groups bespoke design just to make them feel important, even if the bespoke design isn’t architecturally notable or useful for passengers.

Likewise, if there’s any conflict between different users, for example different utilities and infrastructure providers in a city, then it takes some effort to rein it in and coordinate. The same situation occurs for conflict between different users of the same tracks on mainline rail: it takes some effort to coordinate timetables between local and long-distance rail services. The planning effort required is ultimately orders of magnitude cheaper than the cost of segregating the uses – hence the electronics before concrete maxim – but people who don’t care for coordination can find ways to define a project in a way that makes additional concrete (on mainline rail) or extra work with utilities (in urban subways) seem unavoidable.

Moreover, a betterment, non-standardized design, concrete-instead-of-electronics, or scope deflection occurs in context of other people’s money (OPM). If a light rail project pays for a municipality’s streetscaping, the municipality will not try to value-engineer any of it, resulting in unusually high costs.

In New York, one of the reasons for high accessibility costs on the subway, beyond the usual problems of procurement and utility conflict, is scope deflection. The agency doesn’t care about disabled people, and treats disability law as a nuisance. Thus it sandbags elevator installations by bundling them with other projects that it does care about, like adding more staircases or renewing the station finishes, and charging those projects to the accessibility bucket and telling judges how much it is spending on mandated accessibility.

Political advocacy is unwittingly one of the mechanisms for this cost blowout. Transit advocates tend to value transit more than the average person, by definition, and therefore are okay with pushing for projects at higher costs than are acceptable to most. Once a sandbagged budget is out there, such groups often say that even at the higher estimate the project is a bargain and should go ahead. And once there’s political support, it’s easy to spend money with nothing to show for it.

Annoying Announcements

My last two New York trips suddenly made me aware of how obtrusive and loud subway announcements can be. I visited the US many times in the years between when I left (summer 2012) and the start of the pandemic in early 2020, so even while living first in Canada and then in a succession of European capitals known to Americans chiefly as vacation spots, I found New York reassuringly familiar. The two-year gap between when corona started and when I first came back this March should not have been that big, and yet it was. And the constant annoyance of those messages hit me.

I know a lot of people writing about their experiences in New York talk about how it changed dramatically during corona. I get some of this – I see some differences, even if not in as much detail as people who have been here in the city throughout and survived the spring of 2020. But this is not, as far as I remember, a difference. The New York City Subway was always like this – always this hectic and stressful, not so much because of the passengers as because of the system itself. I’ve just, over the years, gotten used to the much more focused and less noisy European systems.

I focus on the announcements because, having talked to some other immigrants who don’t speak the language very well or used not to – a task that’s easier for me in Berlin than in New York – I’ve gotten more sensitive to the issue of tuning out announcements.

The issue here is that passengers learn to tune out unnecessary announcements. “This is 57th Street, Brooklyn-bound F, next stop is 50th Street-Rockefeller Center, stand clear of the closing doors” is a fine announcement. Passengers learn to tune out the ending, but that’s fine – the rest of the message stands and helps anchor where the train is and how long it is until my station.

The problem is announcements like “This is an important message from the New York City Police Department.” These are, at best, an irrelevant annoyance. Experienced riders tune them out and just learn to live with the random noise and distraction that they provide. Less experienced ones may wait for something useful and be disappointed it’s another useless public service announcement.

But one should not assume the best. Annoying announcements are worse than useless, for two reasons. First, any announcement telling people to be afraid of crime is counterproductive. Scared passengers react to such announcements or signs by feeling up their wallets to make sure they’re still there, alerting every thief as to their wallets’ locations on their persons.

And second, the effect on system legibility for riders who speak poor English is large and negative. Such riders strain to get the meaning until they realize it was for nothing, and they might well assume any announcement other than the stops is like this and miss real information. Announcements other than regular stops may be irrelevant PSAs, but they may also be important information about the trip, such as service changes down the line, and the more riders who tune them out, the more they are going to miss connections and attempt to get on a train that isn’t running.

This is really a matter of universal design. Even experienced riders who (like most New Yorkers) speak the language fluently sometimes tune out real announcements and make mistakes. But this effect is larger for new riders, especially immigrants who struggle with the language.

The right way to structure announcements is not to say anything that isn’t directly relevant to the trip. Stations and connections should be announced, and so should service changes on the line itself or on connecting lines. PSAs should not exist; they make the user experience worse and improve nothing except the self-satisfaction of managers who do not use their own system.

Who Learns from Who?

My interactions with Americans in the transit industry, especially mainline rail, repeatedly involve their telling me personally or in their reports that certain solutions are impossible when they in fact happen every day abroad, usually in countries that don’t speak English. When they do reference foreign examples, it’s often shallow or even wrong; the number of times I’ve heard American leftists attribute cost differences to universal health care abroad (in most of these countries, employers still have to pay health benefits) is too high to count. Within the US, New York stands head and shoulders above the rest in its incuriosity. This is part of a general pattern of who learns from who, in which the US’s central location in the global economy and culture makes it collectively stupid.

Symmetric learning

Some learning is symmetric. The Nordic countries learn from one another extensively. The Transit Costs Project’s Sweden case study has various references in the literature to such comparisons:

- Eliasson-Börjesson-Odeck-Welde compare Sweden and Norway in the use of benefit-cost analyses for road projects.

- Smith-Sochor-Sarasini compare Sweden and Finland in Mobility as a Service.

- The Finnish transport ministry compares Finland’s public transport system with those of the other Nordic countries and a selection of other Northern European countries.

- The Nordic Council of Ministers has long worked on pan-Nordic horizontal ties; here is its report on investment in transport infrastructure.

- Södrström-Schulman-Ristimäki compare Stockholm and Helsinki’s urban forms.

- Nilsson-Nyström benchmark Sweden’s privatization of maintenance to Finland, the Netherlands, and Britain.

- LO’s report on labor rights and repression in Swedish tunnel projects compares the situation to that of Norway (where immigrant workers readily join unions) and Denmark (where they do at much lower rates, albeit higher than Sweden’s).

This goes beyond transportation. People in the four mainland Nordic states constantly benchmark their own national performance to that of the other three on matters like immigration, education, energy, corona, and labor. This appears in the academic literature to some extent and is unavoidable in popular culture, including media and even casual interactions that I had in two years of living in Sweden. Swedes who criticize their country’s poor handling of the corona crisis don’t compare it with Taiwan or South Korea but with Norway. Likewise, Swedes who think of a country with open hostility to immigration think of Denmark rather than, say, the United States, Italy, or Lithuania.

Other macro regions exist, too, with similar levels of symmetric learning. The German-speaking world features some of this as well: the advocacy group ProBahn has long championed learning from Switzerland and Austria, and the current Deutschlandtakt plan for intercity rail is heavily based on both Swiss practice and the advocacy of ProBahn and other technically adept activists. Switzerland, in turn, developed its intercity rail planning tradition in the 1980s and 1990s by adopting and refining German techniques, taking the two-hour clockface developed in 1970s Germany under the brand InterCity and turning it into a national investment strategy integrating infrastructure construction with the hourly timetable.

This, as in the Nordic countries, goes beyond transport. Where Swedes’ prototype for hostility to immigrants is Denmark, Germans’ is Austria with its much more socially acceptable extreme right.

Asymmetric learning

Most of the learning from others that we see is not symmetric but asymmetric: one place learns from another but not vice versa, in a core-periphery pattern. Countries and cities prefer to learn from countries that are bigger, wealthier, and culturally more dominant than they are. In our Istanbul case, we detail how the Turks built up internal expertise by bringing in consultants from Italy, Germany, and France and using those experiences to shape new internal practices.

In Europe, the biggest asymmetry is between Southern and Northern Europe. Few Spaniards, Italians, and Turks believe that their respective countries build higher-quality infrastructure than Germans – some readily believe that the costs are lower but assume it must be lower quality rather than higher efficiency. The experts know costs are low, but anything better from Northern Europe or France penetrates into Southern European planning with relative ease. It didn’t make it to the infrastructure-focused Italian case, but Marco Chitti documents how the German clockface schedule is now influencing Italian operations planning, for example here and here on Twitter. Spain’s high-speed rail infrastructure provides another example: it was deeply influenced by France in the 1990s, including the idea of building it, the technical standards and the (unfortunate) operating practices, but the signaling system is more influenced by Germany.

In contrast, in the other direction, there is little willingness to learn. Nordic capital planners and procurement experts cite other Northern European examples (in and out of Scandinavia) as cases to learn from but never Southern European or French ones. The same technically literate German rail activists who speak favorably of Swiss planning look down on French high-speed rail, and one American ESG investor even assumed Italy is falsifying its data. In the European core-periphery model, the North is the core and the South and East are the periphery, and the core will not learn from the periphery even where the periphery produces measurably better results.

Domestically, it’s often the case that smaller cities learn from larger ones in the same country. Former Istanbul Metropolitan staff members were hired by the state, and many staff and contractors went on to build urban rail projects in Bursa, İzmir, and Mersin. In France, RATP acts as consultant to smaller cities, which do not have in-house capacity for metro construction, and overall there is obvious Parisian influence on how such cities build their urban rail. In Italy, Metropolitana Milano has acted as consultant to other cities. This is the primary mechanism that makes construction costs so uniform within countries and within macro regions like Scandinavia.

In this core-periphery model, the Anglosphere is the global core, the United States views itself as its core (Britain disagrees but only to some extent), and New York is the core of the core. New Yorkers respond to any invocation of another city or country with “we are not [that country],” and expect that their audience will believe that New York is superior; occasionally they engage in negative exceptionalism, but as with positive exceptionalism, it exists to deflect from the possibility of learning.

This asymmetry may not be apparent in transportation – after all, Europe and Asia (correctly) feel like they have little to learn from the United States. But on matters where the United States is ahead, Europeans and Asians notice. For example, the US military is far stronger than European militaries, even taking different levels of spending into account – and Europeans backing an EU army constantly reference how the US is more successful due to scale (for examples, here, here, and here). Likewise, in rich Asia, corporations at least in theory are trying to make their salaryman systems more flexible on the Western model, while so little learning happens in the other direction that at no point did Europe or the US seriously attempt to imitate Taiwan’s corona fortress success or the partial successes of South Korea and Japan.

In this schema, it is not surprising that New York (and the United States more generally) has the highest construction costs in the world, and that London has among the highest outside the United States. Were New York and London more institutionally efficient than Italian cities, Italian elites would notice and adapt their practices, just as they have begun to adapt German practices for timetabling and intermodal integration.

Superficial learning

On the surface, Americans do learn from the periphery. There are immigrant planners at American transit agencies. There’s some peer learning, even in New York – for example, New York City Transit used RATP consultants to help develop the countdown clocks, which required some changes to how train control works. And yet, most of this is too shallow to matter.

What I mean by “shallow” is that the learning is more often at the level of a quip comment, with no followup: “[the solution we want] is being used in [a foreign case],” with little investigation into whether it worked or is viewed positively where it is used. Often, it’s part of a junket trip by executives who hoard (the appearance of) knowledge an refuse to let their underlings work. Two notable examples are ongoing in Boston and the Bay Area.

In Boston, the state is making a collective decision not to wire the commuter rail network. Instead, there are plans to electrify the network in small patches, using battery trains with partial wiring; see here and follow links for more background. Battery-electric trains (BEMUs) exist and are procured in European examples that the entire Boston region agrees are models for rail modernization, so in that sense, this represents learning. But it’s purely superficial, because nowhere with the urban area size of Boston or the intensity of its peak commuter rail traffic are BEMUs used. BEMUs trade off higher equipment cost and lower performance for lower infrastructure costs; they’re used in Germany on lines that run an hourly three-car train or so, whereas Massachusetts wants to foist this solution on lines where peak traffic is an eight-car train every 15 minutes.

And in San Jose, the plan for the subway is to use a large-diameter bore, wide enough for two tracks side-by-side as well as a platform in between, to avoid having to either mine station cavern or build cut-and-cover stations. This is an import from Barcelona Metro Lines 9 and 10, and agency planners and consultants did visit Barcelona to see how the method works. Unfortunately, what was missing in that idea is that L9 is by a large margin Spain’s most expensive subway per kilometer, and locally it is viewed as a failure. In Rome, the same method was studied and rejected as too risky to millennia-old monuments, so the most sensitive parts of Metro Line C use mined stations at very high costs by Italian standards. Barcelona’s use case – a subway built beneath a complex underground layer of older metro lines – does not apply to San Jose, which is building its first line and should build its stations cut-and-cover as is more usual.

No such superficiality is apparent in the core examples of both symmetric and asymmetric learning. Swedes, Danes, Finns, and Norwegians are acutely aware of the social problems of one another, and will not propose to adopt a system that is locally viewed as a failure. At most, they will propose an import that is locally controversial, with the same ideological load as at its home. In other words, if a Swede (or more generally a Western European) proposes to import a solution from another European country that is in its home strongly identified with a political party or movement, it’s because the Swede supports the movement at home. This can include privatization, cancellation of privatization, changes to environmental policy, changes to immigration policy, or tax shifts.

This includes more delicate cases. In general the US and UK are viewed as inegalitarian Thatcherite states in Sweden, so in most cases it’s the right that wants to Anglicize government practice. But when it comes to monetary policy, it was Stefan Löfven who tried to shift Riksbank policy toward a US-style dual mandate from the current single mandate for price stability, which the left views as too austerian and harsh toward workers; globally the dual mandate is viewed as more left-wing and so it was the Swedish left that tried to adopt it.

In contrast, in superficial learning, the political load may be the opposite of what it is in its origin country, because the person or movement who purport to want to import it are ignorant of and incurious about its local context. Thus, I’ve seen left-wing Americans proposing education reforms reinvent the German Gymnasium system in which the children of the working class are sent to vocational schools, a system that within Germany relies on the support of the middle-class right and is unpopular on the left.

Individual versus collective knowledge

Finally, I want to emphasize that the issue is less about individual knowledge and learning than about collective knowledge. Individual Americans are not stupid. Many are worldly, visit other countries regularly and know how things work there, and speak other languages as heritage learners or otherwise. But their knowledge is not transmitted collectively. Their peers view it at best as a really cool hobby rather than a key skill, at worst as a kind of weirdness.

For example, an American planner who speaks Spanish because they are a first- or second-generation Hispanic immigrant is not going to get a grant to visit Madrid, or for that matter Santo Domingo, and form horizontal ties with planners and engineers there to figure out how to build at low Spanish or Dominican costs. Their peers are not going to nudge them to tell them more about Hispanic engineering traditions and encourage them to develop their interests. American culture writ large does not treat them as benefiting from bicultural ties but instead treats them as deficient Americans who must forget the Spanish language to assimilate; it’s the less educated immigrants’ children who maintain the Spanish language. In this way, it’s not too different from how Germany treats Turks as a social problem rather than as valuable bicultural ambassadors to a country with four times Germany’s housing production and one third its metro construction costs.

Nor is experience abroad valued in planning or engineering, let alone in politics. A gap year is a fun experience. Five years of work abroad are the mark of a Luftmensch rather than valued experience on a CV, whereas an immigrant who comes with foreign work experience will almost universally find this experience devalued.

Even among the native-born, the standard pipelines through which one expresses interest in foreign ideas are not designed for this kind of learning. The United States most likely has the strongest academic programs in the world for Japanese studies, outside Japan itself. Those programs are designed to critique Japanese society, and Israeli military historian of Japanese imperialism Danny Orbach has complained that from reading much of the critical theory work on the country one is left to wonder how it could have ever developed. It goes without saying such programs do not prepare anyone to adapt the successes of the big Japanese cities in transportation and housing.

This, as usual, goes beyond transportation. I saw minimal curiosity among Americans in the late 2000s about universal health care abroad, while a debate about health care raged and “every rich country except the US has public universal health care” was a common and wrong line among liberals. Individual Americans and immigrants to the US might be able to talk about the French or Japanese or Israeli or Ghanaian health care system, but nobody would be interested to hear except their close friends; political groups they were involved with would shrug that off even while going off about the superiority of those countries’ health care (well, not Ghana’s, but all of the other three for sure, in ignorance of Israel’s deep problem with nosocomial infections, responsible for 9-14% of the national death rate).

The result is that while individual Americans can be smart, diligent, and curious, collectively the United States is stupid, lazy, and ignorant on every matter that other parts of the world do better. This is bad in public transportation and lethal in those aspects of it that use mainline rail, where the US is generations behind and doesn’t even know where to start learning, let alone how to learn. It’s part of a global core-periphery model in which Europe hardly shines when it comes to learning from poorer parts of Europe or from non-Western countries, but the US adds even more to that incuriosity. Within the US, the worst is New York, where even Chicago is too suspect to learn from. No wonder New York’s institutions drifted to the point that construction costs in the city are 10 times higher than they can be, and nearly 20 times as high as absolute best practice.

Deinterlining and Schedule Robustness

There’s an excellent Uday Schultz blog post (but I repeat myself) about subway scheduling in New York. He details some stunning incompetence, coming from the process used to schedule special service during maintenance (at this point, covering the entirety of the weekend period but also some of the weekday off-peak). Some of the schedules are physically impossible – trains are scheduled to overtake other trains on the same track, and at one point four trains are timetabled on the same track. Uday blames this on a combination of outdated software, low maintenance productivity, aggressive slowdowns near work zones, and an understaffed planning department.

Of these, the most important issue is maintenance productivity. Uday’s written about this issue in the past and it’s a big topic, of similar magnitude to the Transit Costs Project’s comparison of expansion costs. But for a fixed level of maintenance productivity, there are still going to be diversions, called general orders or GOs in New York, and operations planning needs to schedule for them. How can this be done better?

The issue of office productivity

Uday lists problems that are specific to scheduling, such as outdated software. But the software is being updated, it just happens to be near the end of the cycle for the current version.

More ominous is the shrinking size of ops planning: in 2016 it had a paper size of 400 with 377 positions actually filled, and by 2021 this fell to 350 paper positions and 284 actually filled ones. Hiring in the American public sector has always been a challenge, and all of the following problems have hit it hard:

- HR moves extraordinarily slowly, measured in months, sometimes years.

- Politicians and their appointees, under pressure to reduce the budget, do so stupidly, imposing blanket hiring freezes even if some departments are understaffed; those politicians universally lack the competence to know which positions are truly necessary and where three people do the job of one.

- The above two issues interact to produce soft hiring freezes: there’s no hiring freeze announced, but management drags the process in order to discourage people from applying.

- Pay is uncompetitive whenever unemployment is low – the compensation per employee is not too far from private-sector norms, but much of it is locked in pensions that vest after 25 years, which is not the time horizon most new hires think in.

- The combination of all the above encourages a time clock managerial culture in which people do not try to rock the boat (because then they will be noticed and may be fired – lifetime employment is an informal and not a formal promise) and advancement is slow, and this too deters junior applicants with ambition.

Scheduling productivity is low, but going from 377 to 284 people in ops planning has not come from productivity enhancements that made 93 workers redundant. To the contrary, as Uday explains, the workload has increased, because the maintenance slowdowns have hit a tipping point in which it’s no longer enough to schedule express trains on local train time; with further slowdowns, trains miss their slots at key merge points with other lines, and this creates cascading delays.

Deinterlining and schedule complexity

One of the benefits of deinterlining is that it reduces the workload for ops planning. There are others, all pertaining to the schedule, such as reliability and capacity, but in this context, what matters is that it’s easier to plan. If there’s a GO slowing down the F train, the current system has to consider how the F interacts with every other lettered route except the L, but a deinterlined system would only have to consider the F and trains on the same trunk.

This in turn has implications for how to do deinterlining. The most urgent deinterlining in New York is at DeKalb Avenue in Brooklyn, where to the north the B and D share two tracks (to Sixth Avenue) and the N and Q share two tracks (to Broadway), and to the south the B and Q share tracks (to Coney Island via Brighton) and the D and N share tracks (to Coney Island via Fourth Avenue Express). The junction is so slow that trains lose two minutes just waiting for the merge point to clear, and a camera has to be set up pointing at the trains to help dispatch. There are two ways of deinterlining this system: the Sixth Avenue trains can go via Brighton and Broadway trains via Fourth Avenue, or the other way around. There are pros and cons either way, but the issue of service changes implies that Broadway should be paired with Fourth Avenue, switching the Q and D while leaving the B and N as they are. The reason is that the Fourth Avenue local tracks carry the R, which then runs local along Broadway in Manhattan; if it’s expected that service changes put the express trains on local tracks often, then it’s best to set the system up in a way that local and express pairings are consistent, to ensure there’s no interlining even during service changes.

This should also include a more consistent clockface timetable for all lines. Present-day timetabling practice in New York is to fine-tune each numbered and lettered service’s frequency at all times of day based on crowding at the peak point. It creates awkward situations in which the 4 train may run every 4.5 minutes and the 5, with which it shares track most of the way, runs every 5.5, so that they cannot perfectly alternate and sometimes two 4s follow in succession. This setup has many drawbacks when it comes to reliability, and the resulting schedule is so irregular that it visibly does not produce the intended crowding. Until 2010 the guideline was that off-peak, every train should be occupied to seated capacity at the most crowded point and since 2010 it has been 125% of seated capacity; subway riders know how in practice it’s frequently worse than this even when it shouldn’t be, because the timetables aren’t regular enough. As far as is relevant for scheduling, though, it’s also easier to set up a working clockface schedule guaranteeing that trains do not conflict at merge points than to fine-tune many different services.

Deinterlining and delocalization of institutional knowledge

Uday talks about New York-specific institutional knowledge that is lost whenever departments are understaffed. There are so many unique aspects of the subway that it’s hard to rely on scheduling cultures that come from elsewhere or hire experienced schedulers from other cities.

There is a solution to this, which is to delocalize knowledge. If New York does something one way, and peers in the US and abroad do it another way, New York should figure out how to delocalize so that it can rely on rest-of-world knowledge more readily. Local uniqueness works when you’re at the top of the world, but the subway has high operating costs and poor planning and operations productivity and therefore its assumption should be that its unique features are in fact bugs.

Deinterlining happens to achieve this. If the subway lines are operated as separate systems, then it’s easier to use the scheduling tools that work for places with a high degree of separation between lines, like Boston or Paris or to a large extent London and Berlin. This also has implications for what capital work is to be done, always in the direction of streamlining the system to be more normal, so that it can cover declining employee numbers with more experienced hires from elsewhere.

The Baboon Rule

I made a four-hour video about New York commuter rail timetabling on Tuesday (I stream on Twitch most Tuesdays at 19:00 Berlin time); for this post, I’d like to extract just one piece of this, which informs how I do commuter rail proposals versus how Americans do them. For lack of a better term, on video I called one of the American planning maxims that I violate the baboon rule. The baboon rule states that an agency must assume that other agencies that it needs to interface with are run by baboons, who are both stupid and unmovable. This applies to commuter rail schedule planning but also to infrastructure construction, which topic I don’t cover in the video.

How coordination works

Coordination is a vital principle of good infrastructure planning. This means that multiple users of the same infrastructure, such as different operators running on the same rail tracks, or different utilities on city streets, need to communicate their needs and establish long-term horizontal relationships (between different users) and vertical ones (between the users and regulatory or coordinating bodies).

In rail planning this is the Verkehrsverbund, which coordinates fares primarily but also timetables. There are timed transfers between the U- and S-Bahn in Berlin even though they have two different operators and complex networks with many nodes. In Zurich, not only are bus-rail transfers in the suburbs timed on a 30-minute Takt, but also buses often connect two distinct S-Bahn lines, with timed connections at both ends, with all that this implies about how the rail timetables must be built.

But even in urban infrastructure, something like this is necessary. The same street carries electric lines, water mains, sewer mains, and subway tunnels. These utilities need to coordinate. In Milan, Metropolitana Milanese gets to coordinate all such infrastructure; more commonly, the relationships between the different utilities are horizontal. This is necessary because the only affordable way to build urban subways is with cut-and-cover stations, and those require some utility relocation, which means some communication between the subway builders and the utility providers is unavoidable.

The baboon rule

The baboon rule eschews coordination. The idea, either implicit or explicit, is that it’s not really possible to coordinate with those other agencies, because they are always unreasonable and have no interest in resolving the speaker’s problems. Commuter rail operators in the Northeastern US hate Amtrak and have a litany of complaints about its dispatching, and vice versa – and as far as I can tell those complaints are largely correct.

Likewise, subway builders in the US, and not just New York, prefer deep tunneling at high costs and avoid cut-and-cover stations just to avoid dealing with utilities. This is not because American utilities are unusually complex – New York is an old industrial city but San Jose, where I’ve heard the same justification for avoiding cut-and-cover stations, is not. The utilities are unusually secretive about where their lines are located, but that’s part of general American (or pan-Anglosphere) culture of pointless government secrecy.

I call this the baboon rule partly because I came up with it on the fly during a Twitch stream, and I’m a lot less guarded there than I am in writing. But that expression came to mind because of the sheer horror that important people at some agencies exuded when talking about coordination. Those other agencies must be completely banally evil – dispatching trains without regard for systemwide reliability, or demanding their own supervisors have veto power over plans, or (for utilities) demanding their own supervisors be present in all tunneling projects touching their turf. And this isn’t the mastermind kind of evil, but rather the stupid kind – none of the complaints I’ve heard suggests those agencies get anything out of this.

The baboon rule and coordination

The commonality to both cases – that of rail planning and that of utility relocation – is the pervasive belief that the baboons are unmovable. Commuter rail planners ask to be separated from Amtrak and vice versa, on the theory that the other side will never get better. Likewise, subway builders assume electric and water utilities will always be intransigent and there’s nothing to be done about it except carve a separate turf.

And this is where they lose me. These agencies largely answer to the same political authority. All Northeastern commuter rail agencies are wards of the federal government; in Boston, the idea that they could ever modernize commuter rail without extensive federal funding is treated as unthinkable, to the point that both petty government officials and advocates try to guess what political appointees want and trying to pitch plans based on that (they never directly ask, as far as I can tell – one does not communicate with baboons). Amtrak is of course a purely federal creature. A coordinating body is fully possible.

Instead, the attempts at coordination, like NEC Future, ask each agency what it wants. Every agency answers the same: the other agencies are baboons, get them out of our way. This way the plan has been written without any meaningful coordination, by a body that absolutely can figure out combined schedules and a coordinated rolling stock purchase programs that works for everyone’s core passenger needs (speed, capacity, reliability, etc.).

The issue of utilities is not too different. The water mains in New York are run by DEP, which is a city agency whereas the MTA is a state agency – but city politicians constantly proclaim their desire to improve city infrastructure, contribute to MTA finances and plans (and the 7 extension was entirely city-funded), and would gain political capital from taking a role in facilitating subway construction. And yet, it’s not possible to figure out where the water mains are, the agency is so secretive. Electricity and steam are run by privately-owned Con Ed, but Con Ed is tightly regulated and the state could play a more active role in coordinating where all the underground infrastructure is.

And yet, in no case do the agencies even ask for such coordination. No: they ask for turf separation. They call everyone else baboons, if not by that literal term, but make the same demands as the agencies that they fight turf wars with.

Negative Exceptionalism and Fake Self-Criticism

Yesterday, Sandy Johnston brought up a point he had made in his thesis from 2016: riders on the Long Island Rail Road consider their system to be unusually poorly-run (PDF-pp. 19-20), and have done so for generations.

The 100,000 commuters on Long Island—the brave souls who try to combine a job in New York City with a home among the trees—represent all shades of opinion on politics, religion, and baseball. But they are firmly agreed on one thing—they believe that the Long Island Rail Road, which constitutes their frail and precarious life line between home and office, is positively the worst railroad in the world. This belief is probably ill considered, because no one has ever made a scientific survey, and it is quite possible that there are certain short haul lines in the less populous parts of Mongolia or the Belgian Congo where the service is just as bad if not worse. But no Long Islander, after years of being trampled in the crowded aisles and arriving consistently late to both job and dinner, would ever admit this.

(Life, 1948, p. 19)

The quoted Life article goes over real problems that plagued the LIRR even then, such as absent management and line worker incompetence stranding passengers for hours. This kind of “we are the worst” criticism can be easily mistaken for reform pressure and interest in learning from others who, by the critic’s own belief, are better. But it’s not. It’s fake self-criticism; the “we are the worst” line is weaponized in the exact opposite direction – toward entrenchment and mistrust of any outside ideas, in which reformers are attacked as out of touch far more than the dispatcher who sends a train to the wrong track.

Negative exceptionalism

The best way to view this kind of fake self-criticism is, I think, through the lens of negative exceptionalism. Negative exceptionalism takes the usual exceptionalism and exactly inverts it: we have the most corrupt government, we have the worst social problems, we are the most ungovernable people. The more left-wing version also adds, we have the worst racism/sexism. In all cases, this is weaponized against the concept of learning from elsewhere – how can we learn from countries where I spent three days on vacation and didn’t feel viscerally disgusted by their poor people?

For example, take the political party Feminist Initiative, which teetered on the edge of the electoral threshold in the 2014 election in Sweden and won a few seats in municipal elections and one in the European Parliament. It defined itself in favor of feminism and against racism, and talked about how the widespread notion that Sweden is a feminist society is a racist myth designed to browbeat immigrants, and in reality Sweden is a deeply sexist place (more recently, Greta Thunberg would use the same negative exceptionalism about environmentalism, to the point of saying Sweden is the most environmentally destructive country). The party also advocated enforcing the Nordic model of criminalization of sex work on the rest of the EU; the insight that Sweden is a sexist society does not extend to the notion that perhaps it should not tell the Netherlands what to do.

Sweden is an unusually exceptionalist society by European standards. The more conventional Sweden-is-the-best exceptionalism is more common, but doesn’t seem to produce any different prescriptions regarding anything Sweden is notable for – transit-oriented development, criminalizing sex work, taking in large numbers of refugees, deliberately infecting the population with corona, building good digital governance. This mentality passes effortlessly between conventional and negative exceptionalism, and at no point would anyone in Sweden stop and say “maybe we have something to learn from Southern Europe” (the literature I’ve consulted for the soon-to-be-released Sweden case of the Transit Costs Project is full of intra-Nordic comparisons, and sometimes also comparisons with the UK and the Netherlands, but never anything from low-cost Southern Europe).

And of course, the United States matches or even outdoes Sweden. The same effortless change between we’re-the-best and we’re-the-worst is notable. Americans will sometimes in the same thread crow about how their poorest states are richer than France and say that poor people in whichever country they’ve visited last are better-behaved than the American poor (read: American tourists can’t understand what they’re saying) and that’s why those countries do better. They will in the same thread say the United States is uniquely racist and also uniquely anti-racist and in either case has nothing to learn from other places. The most outrage I’ve gotten from left-wing American activists was when I told them my impression of racism levels in the United States is that they are overall similar to levels in Western Europe; the US is allowed to be uniquely racist or uniquely anti-racist, but not somewhere in the middle.

The situation in New York

New York’s exceptionalism levels are extreme even by American standards. This, again, includes both positive and negative exceptionalism. New Yorkers hold their city to be uniquely diverse (and not, say, very diverse but at levels broadly comparable with Toronto, Singapore, Gush Dan, or Dubai), but look down on the same diversity – “they don’t have the social problems we do” is a common refrain about any non-US comparison. Markers of socioeconomic class are local, regional, or national, but not global, so a New Yorker who visits Berlin will not notice either the markers of poverty that irk the German middle class or general antisocial German behavior. For example, in Berlin, rail riders are a lot worse at letting passengers get off the train before getting on than in New York, where subway riders behave more appropriately; but New York fears of crime are such that “Germans are better-behaved than New Yorkers” is a common trope in discussion of proof of payment and driver-only trains.

This use of negative exceptionalism as fake criticism with which to browbeat actual criticism extends to the lede from Life in 1948. Sandy’s thesis spends several more pages on the same article, which brings up the informal social camaraderie among riders on those trains, where the schedules were (and still are) bespoke and commuters would take the same trains every day and sit at the same location with the same group of co-commuters, all of the same social class of upper middle-class white men. These people may hold themselves as critics of management, but in practice what they demanded was to make the LIRR’s operating practices even worse: more oriented around their specific 9-to-5 use case, and certainly not service akin to the subway, which they looked down, as did the planners.

Fake criticism as distraction from reform

The connection between negative exceptionalism and bad practices is that negative exceptionalism always tells the reformer: “we’re ungovernable, this can’t possibly work here.” The case of proof-of-payment is one example of this: New York is the greatest city in the world but it’s also the most criminal and therefore New Yorkers, always held to be different from (i.e. poorer than) the speaker who after all is a New Yorker too, must be disciplined publicly and harshly. Knowledge of how POP works in Germany is irrelevant to New York because Germans are rulebound and New Yorkers are ungovernable. Knowledge of how street allocation works in the Netherlands is irrelevant to the United States because the United States is either uniquely racist (and thus planners are also uniquely racist) or uniquely antiracist (and thus its current way of doing things is better than foreign ways). Knowledge of integrated timetable and infrastructure planning in Switzerland or Japan is irrelevant because New York has a uniquely underfunded infrastructure system (and not, say, a $50 billion five-year MTA capital plan).

More broadly, it dovetails into New Right fake criticism of things that annoy the local notables. The annoyance is real, but because those local notables are local, they reject any solution that is not taken directly from their personal prejudices; they lack the worldliness to learn and implement best practices and they know it, and so their status depends on the continuation of bad practices. (Feminist Initiative is not a New Right party, or any kind of right, but its best national result was 3%; decline-of-the-West parties more rooted in the New Right do a lot better.)

The good news for New York at least is that the LIRR and Metro-North are genuinely bad. This means that even a program of social and physical bulldozing of the suburban forces that keep those systems the way they are generates real physical value in reliability and convenience to compensate some (not all) for the loss of status. The complaints will continue because the sort of person who announces with perfect confidence that their commute is the worst in the world always finds things to complain about, but the point is not to defuse complaints, it’s to provide good service, and those people will adjust.