Category: Transportation

High-Speed Rail is not for Tourists

Foreigners to a country often get a warped idea of what its infrastructure is like. Most infrastructure is used for day-to-day domestic travel, for commuting to work or school, for visits to family and friends, for social gatherings, for business travel within the national internal market. Foreign travelers make use of this infrastructure when they visit, but they use it differently, and can make erroneous assumptions about how locals use it and what it means for transportation in general. This has two policy implications: one concerns American misconceptions about European rail travel; the other concerns pan-European misconceptions about European rail travel, which is almost entirely domestic, based on domestic networks, and planned and debated in the local language and not in English.

The Europe of the tourists

To estimate how foreign tourists may view Europe, we need some information on tourist travel within the bloc. The best I have is lists of the most visited cities in the world, and unfortunately, the only lists I have that go beyond the global top 10 are from before corona. But 2019 should not be too different to first order from the present. Here are international arrivals, from the global top 50:

| City | Millions of arrivals (2019) |

| London | 19.55 |

| Paris | 19.08 |

| Istanbul | 14.71 |

| Rome | 10.31 |

| Prague | 9.15 |

| Amsterdam | 8.83 |

| Barcelona | 7.01 |

| Vienna | 6.63 |

| Milan | 6.6 |

| Athens | 6.3 |

| Berlin | 6.19 |

| Moscow | 5.96 |

| Venice | 5.59 |

| Madrid | 5.59 |

| Dublin | 5.46 |

Notably, there’s almost no intersection with any of the busiest intercity rail links in Europe. The top two are the trunk from Paris on the LGV Sud-Est to the bifurcation between Dijon and Lyon, and the Frankfurt-Mannheim trunk line. Paris is a huge international tourist draw, but nothing on the LGV Sud-Est and its extensions is; the top department outside Ile-de-France in tourism overnight stays is Alpes-Maritimes, a 5.5-6 hour trip from Paris by TGV. Germany has little tourism for its size, especially not in Mannheim – foreigners come to Berlin or Munich, or maybe Frankfurt for business trips. Only two city pairs in Europe with solid high-speed rail links appear in the table above, Milan-Rome and Madrid-Barcelona.

The upshot is that the American tourist who comes here and marvels at the fact that even in Germany the trains are faster and more reliable than in the United States isn’t really experiencing the system as most users do. If they take the TGV, it’s much likelier that they’re taking Eurostar and dealing with its premium prices and probably also with its security theater if they’re going to London rather than Brussels or Amsterdam. They have nothing to do in Lyon or Bordeaux or Strasbourg or Lille, so it’s unlikely they see the workhorse domestic lines. It’s even more unlikely they take the train to the smaller cities with direct TGVs, such as Saint-Etienne, Chambéry, and others that beef up the ridership of the LGV Sud-Est without serving Lyon itself; there were considerable errors made by American analysts in the Obama era about high-speed rail coming from looking only at the million-plus metro areas and not at these secondary ones.

By the same token, the American tourist in question is much likelier to be riding Spanish trains with their brand and price differentiation by speed than to be riding the workhorse regional and intercity trains anywhere in Northern Europe. ICEs charitably average 160 km/h on a handful of lines when they’re on time, which isn’t often, and on key corridors like Berlin-Cologne or Berlin-Frankfurt are closer to 120 km/h. The reason Germany is close to even with France on ridership per capita and well ahead of Italy and Spain is that these trains have decent connections with one another and with slower regional trains, so that people can connect to those secondary cities better. Trips from Berlin to Augsburg with a connection in Munich are not hard to plan, or trips to city cores in the Rhine-Ruhr and other polycentric regions. These are largely invisible to the foreign tourist, who doesn’t have anything to do in a city like Münster.

This also applies to the European tourist, not just the American or Asian or Middle Eastern one. A German who visits France is interested in trains from Germany to Paris, and those are not that good, but will probably not be taking TGVs between Paris and Rennes or Lille. From that, they’ll conclude the TGVs aren’t that useful in general.

The Europe of the typical intercity rail traveler

In contrast with the tourists’ picture of the countries of Europe, the typical intercity rail traveler uses the system in a way that the table above doesn’t really capture. All of the following characteristics are likely:

- They are traveling domestically since cross-border rail within Europe is practically never good.

- They are traveling based on domestic business, leisure, and social networks: if French, they can be going between Paris and anywhere else in France, and very occasionally even between two places outside Ile-de-France; if German, they are likely going between two major cities or maybe between a major and a midsize city.

- They are a regular traveler, which implies good knowledge of the system and its quirks, experience with large complex stations allowing getting between the train and the street within minutes, and probably also some kind of discounted fare card such as the BahnCard 25 in Germany or the half-fare card of Switzerland.

- They have the disposable income to drive, and choose to take the train because of a combination of speed, fares, and convenience rather than because they truly can’t afford a car or because they are ideologically opposed to travel modes with high greenhouse gas emissions.

The upshot is that finicky systems like the TGV and ICE are useful to their current travelers, even if foreigners and people who move in pan-European networks find them unreliable for various reasons. Any kind of EU-wide policy on rail has to acknowledge that SNCF and DB may have problems but are the main providers of solid intercity rail within Europe and are not the enemy, they just focus on city pairs that reflect their domestic travel needs.

And any attempt to learn from Europe and adapt our intercity rail successes has to look beyond what a tourist visiting for a few days would notice. It’s not just the wow effect of speed; Eurostar has that too and its ridership is an embarrassment, with fewer London-Paris trips per day than Paris-Lyon even though metro London is around six times the size of metro Lyon. It’s other details of the network, including how far it reaches into the longer tail of secondary markets.

The secondary markets require especial concern, first because they form a large fraction (likely a majority) of European high-speed rail travel, second because they’re invisible to tourists, and third because they require careful optimization.

One issue is that secondary markets are great for cars, decent for trains, and awful for planes. The TGV owns them at distances where cars take too many hours longer than the train, which helps extend the trains well past the three- to four-hour limit that rail executives quote as the upper bound for competitive train trip time. At shorter range, high-speed rail competes with cars more than with planes, and so the secondary markets lose value.

Another issue is that it’s easy to overdo secondary markets at the expense of compromising speed on the primary ones. This is usually not because of tourists, who almost never ride them, but rather because of domestic travelers who are atypically familiar with and dependent on the system and will use it not just on city pairs like Berlin-Augsburg or Berlin-Münster but also things like Wismar-Jena, on which most people will just drive. In the United States, groups of users of Amtrak trains outside the Northeast Corridor like the Rail Passengers’ Association (RPA, distinct from the New York-area planning organization) routinely make this mistake and overrate the viability of slow night trains. I bring this up here because it is possible to overcorrect from the principle of “don’t rely on tourist reports too much, and do pay attention to the secondary markets” and instead pay too much attention to the secondary markets.

Why is Janno Lieber Constantly Blaming Other People for Problems?

The Editorial Board posted an interview with MTA head Janno Lieber about sundry public transit-related issues. His answers for the most part aren’t bad until he gets to construction costs (and misgenders me), but alongside other recent news about Penn Station Access, they reveal a pattern: Lieber loves blaming other people for problems – nothing is ever the MTA’s fault, everything is someone else’s fault. Nor is he curious about acquiring expertise, to the point that everything is defensive, and everything is about reducing transparency and accountability. Someone like this should not be heading a public transit agency.

Penn Station Access

Penn Station Access, the project to run Metro-North trains from New Rochelle to Penn Station via the Hell Gate Line currently used only by Amtrak, was announced earlier this month to be delayed by a further two years, from 2028 to 2030. The MTA blames Amtrak, which owns most of the line, for not giving it enough work windows.

And, excuse me, but this is bullshit for two separate reasons. The first is that the opening date was said to be 2027 until this year and then 2028. Other people made plans based on MTA announcements; quite a lot of behind-the-scenes advocacy was designed specifically around this date. The state was among those other people: in March, it decided to buy new battery-powered locomotives, each costing $23.45 million (about the same as an eight-car EMU set), on the grounds that it would take too long to acquire new EMUs that were compatible with the different electrification systems used on the line. It’s not at all hard to get new EMUs compatible with both the 12 kV 60 Hz electrification used on most of the line and the 12 kV 25 Hz system used in the last few km into Penn Station based on current New York lead times if the project opens in 2030. But the state made a decision based on the assumption it would need this well before 2030.

In other words, the MTA only discovered that there would be Amtrak-induced delays around two and a half years before planned opening for a project that had been going on for three years and approved for six – and now it’s blaming it on Amtrak instead of on its own poor project management and lack of transparency.

The second reason it’s bullshit is that the relationship between Amtrak and the MTA is mutually abusive. Amtrak is not giving the MTA enough work windows on the Hell Gate Line; the MTA is slowing down Amtrak trains on the New Haven Line between New Rochelle and New Haven, where it owns the tracks, the only part of the Northeast Corridor that is both owned and dispatched by a commuter railroad and not Amtrak (in Massachusetts the MBTA owns the tracks but Amtrak controls dispatching). The maximum allowed cant deficiency on Metro-North territory is based on unmodernized Metro-North values and not based on the modern values that Amtrak rolling stock has been tested for, and there is no attempt to keep Amtrak and Metro-North trains separate east of Stamford, where there are four tracks and light enough traffic that it’s possible, that the top speeds can have a mismatch.

In other words, the MTA complains about being abused by Amtrak, and is likely correct, but refuses to stop abusing Amtrak where it does have control. It could manage this relationship better, but it doesn’t and Lieber isn’t competent enough to know how to do it better.

Fares

The conversation in The Editorial Board heavily features talking about fares, in context of fare evasion and mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani’s proposal for free buses. Lieber is suggesting that instead of free buses, buses can have all-door boarding without free fares, unlocking the speed benefits without forgoing the revenue. He’s right and I want to sympathize with his critique of free buses. But it was Lieber who scuttled plans by Andy Byford to install back-door OMNY card readers and enable all-door boarding without free fares. He calls for all-door boarding as an alternative to free buses now, but when all-door boarding was available as an internally developed plan, he killed it.

He speaks about Europe this and Europe that in the interview, but he’s too ignorant and incurious to understand how things go here and how we make all-door boarding work with proof-of-payment. And the best way to see that is his abominable line, “had a kid who did a semester abroad in Stockholm, and you see them all over in Europe.” That’s his only reference – his kid did a semester abroad. He didn’t ring up any transit agency to ask how to do it. It’s all superficial, almost tourist-level understanding of better-run systems.

This is especially bad in context of what he says about construction costs at the end. He says,

I don’t accept the Alon Levy theory, which, you know, you’re articulating — that somehow, if we just had like this massive in-house force, we would be building everything way, way cheaper. That’s like, hiring— you cannot compete with private-sector engineering. And we don’t have one project after another, like he loves, like Madrid, which built all these subways in a row.

Setting aside the fact that calling me “he” in New York, a city with better access to gender-neutral bathrooms than my own, is obnoxious, we didn’t do a report on Madrid, but did do one on Stockholm. He’s aware of the report (and of the points it makes about ridership per station, the excuse he uses farther down the line for bigger stations). And he still reduces Stockholm to where his kid did a one-semester study abroad to give a little anecdote on fare evasion, which boils down to Americans being so detached from internal national discourses in Europe (except maybe the UK) that they don’t know that we’ve had to deal with the same questions they did, we just have public agencies run by competent people who sometimes make the right decisions and not by people like Janno Lieber.

Reverse-Branching on Commuter Rail

Koji asked me 3.5 days ago about why my proposal for New York commuter rail through-tunnels has so much reverse-branching. I promised I’d post in some more detail, because in truth, reverse-branching is practically inevitable on every commuter rail system with multiple trunk lines, even systems that are rather metro-like like the RER or the S-Bahns here and in Hamburg.

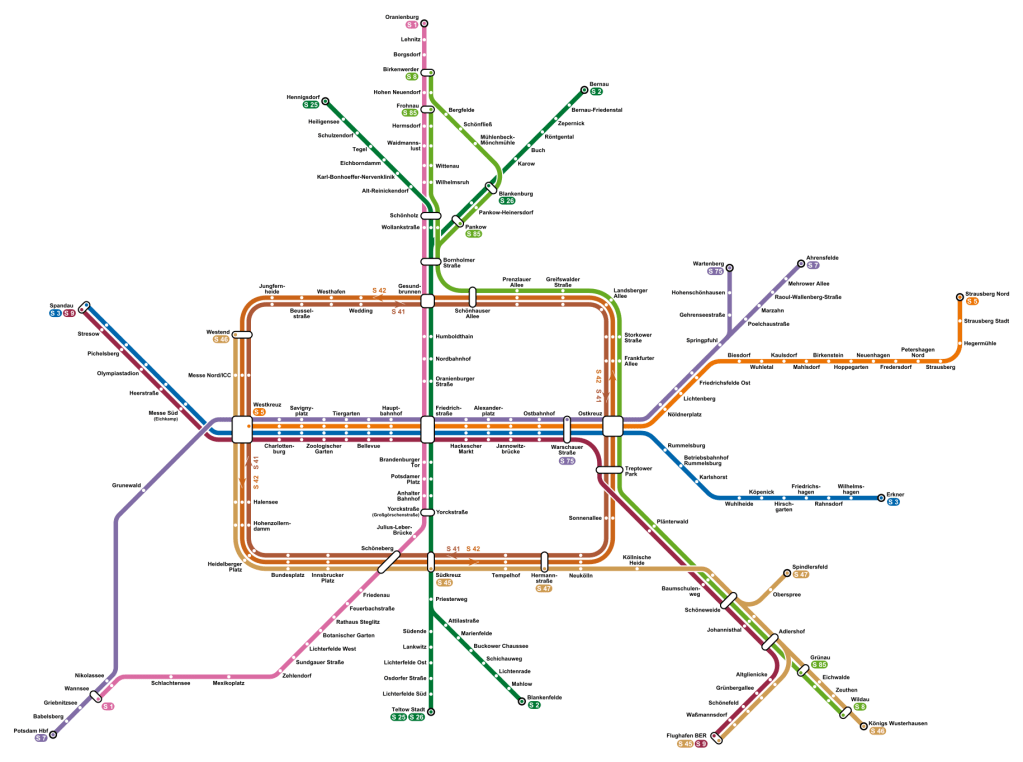

This doesn’t mean that reverse-branches, in this case the split from the Görlitzer Bahn trunk toward the Stadtbahn via S9 and the Ring in two different directions via S45/46/47 and S8/85, are good. It would be better if Berlin invested in turning this trunk into a single trunk into city center, provided it were ready to build a third through-city line (in fact, it is, but this project, S21, essentially twins the North-South Tunnel). However, given the infrastructure or small changes to it, the current situation is unavoidable.

Moreover, the current situation is not the end of the world. The reasons such reverse-branches are not good for the health of the system are as follows:

- They often end up creating more frequency outside city center than toward it.

- If there is too much interlining, then delays on one branch cascade to the others, making the system more fragile.

- If there is too much interlining, then it’s harder to write timetables that satisfy every constraint of a merge point, even before we take delays into account.

All of these issues are more pressing on a metro system than on a commuter rail system. The extent of branching on commuter rail is such that running each line as a separate system is unrealistic; tight timetabling is required no matter what, and in that case, the lines could reverse-branch if there’s no alternative without much loss of capacity. The S-Bahn here is notoriously unreliable, but that’s the case even without cascading delays on reverse-branches – the system just assumes more weekend shutdowns, less reliable systems (28,000 annual elevator outages compared with 1,800 on the similar-size U-Bahn), and worse maintenance practices.

So, on the one hand, the loss from reverse-branching is reduced. On the other hand, it’s harder to avoid reverse-branching on commuter rail. The reason is that, unlike a metro (including a suburban metro), the point of the system is to use old commuter lines and connect them to form a usable urban and suburban service. Because the system relies on old lines more, it’s less likely that they’re at the right places for good connections. In the case of Berlin, it’s that there’s an east-west imbalance that forces some east-center-east lines via S8, which was reinforced by the context of the Cold War and the Wall.

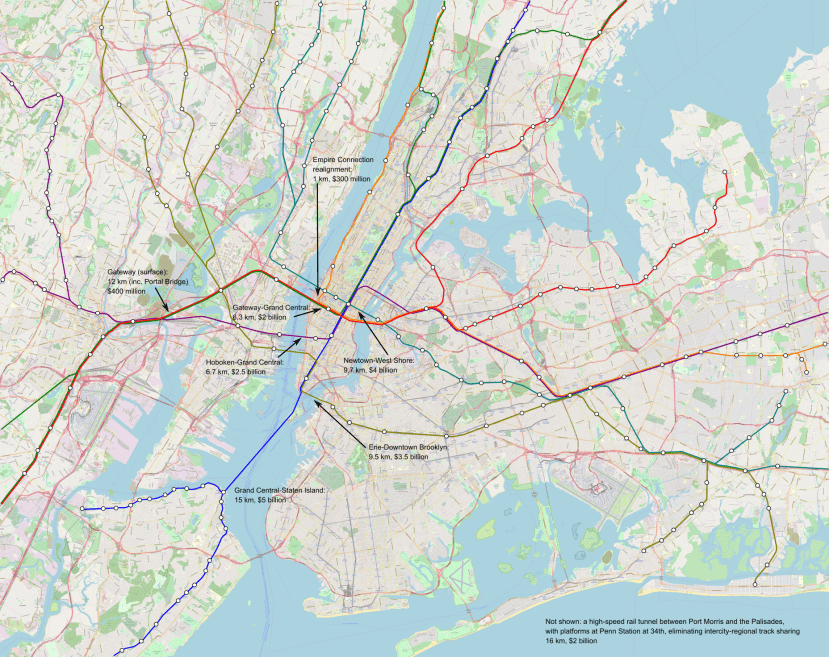

In the case of New York, consider this map:

The issue is that too much traffic wants to use the Northeast Corridor lines in both New Jersey and Connecticut. Therefore, it’s not possible to segregate everything, with lines using the preexisting North River Tunnels and the new Gateway tunnels having to share tracks. It’s not optimal, but it’s what’s possible.

The Invention of the Traditional System of Project Delivery

In the Sweden case, I contrasted the emerging UK-influenced norms of infrastructure project delivery, which I called the globalized system, with the way Nordic procurement was previously done, which I called the traditional system. This explained Nordic trends well, in which Stockholm went from having construction costs so low in the second half of the 20th century they were at times even lower than those of Spain to having rather average costs for Europe. But elsewhere, calling the set of good project delivery practices reliant on an active, expert, apolitical public sector traditional ended up obscuring too much. In the United States, for one, the traditional practices did not work like that at all. In Italy, the project delivery practices are thoroughly traditional in the Nordic sense, but go back to mani pulite in the 1990s.

That said, this procurement system represents an evolution of prior norms of state-led planning, and is less of a break from them than the globalized system is. It’s best viewed as a system based on transparency and good government insights from the second half of the 20th century, rather than on giving up on good government and privatizing to the private sector as the globalized system does. In either case, it has little to do with traditional or emerging American practices, the former based on the good government practices of the early 20th century and the latter an adaptation of the globalized system in an even worse context. Regardless, its benefits are extensive, with interviewees in New York and increasingly London finding various wastes in the process of their own project delivery that can double the cost or even worse.

Good procurement practices: a recap

Good infrastructure megaproject delivery – at least subways, but also likely road tunnels as far as we can tell from small data – requires an active public sector that can supervise consultants and contractors, learn within its own institutions, and assume risk.

In Southern Europe today, and in the Nordic countries until recently, this means the following:

- Technical scoring: infrastructure contracts must be awarded primarily on the technical score of the proposal (50-80% of the weight of the contract) and not on the cost (maximum 50%, ideally about 30%)

- Itemized costs: contracts must have a bill of items, priced based on transparent lists produced by the state, with change orders using the same itemized list to reduce conflict

- Separation of design and construction into two contracts (design-bid-build), rather than bundling into design-build contracts

- Public-sector planning, with the decisions on the type of project and technology made before any designers are contracted

- Flexibility for the builders to vary from the design, so that in practice the design only covers 60-80% of the design, as 100% design is impossible underground until one starts digging

- Moderate-size contracts (tens of millions of dollars or euros to very low hundreds), to allow more contractors to compete

- Limited use of consultants, or, if consultants are used, regular public-sector supervision

This is not entirely in pure contrast to the globalized system, which centers the needs of large multinationals. The large multinationals prefer large-size fixed-price design-build contracts with early contractor involvement and extensive reliance on consultants, but they also prefer technical scoring, which makes them feel like racing to the top rather than the bottom.

This is also not always traditional. In the United States, for example, there is no tradition of technical scoring, itemization of costs, or any flexibility for builders to vary from design. This is because American procurement laws and traditions go back to the Progressive Era, when lowest-bid contracts were thought to be a good government innovation; as it is, American law permits technical scoring as the law states lowest responsible bid, but it’s almost never used, and never to the full extent, so the tradition remains lowest-bid.

The evolution of project delivery in Scandinavia

Traditional Nordic subway infrastructure project delivery was largely in line with the above outline of good practices. However, two variations are notable, one small and one large.

The small variation is that Nordic governments have been happier to outsource operations and even some construction design to private contractors than governments in the rest of Europe; in Finland, project delivery was largely done by private consultants, but under public-sector supervision, with institutional knowledge retained in government agencies even in an environment of privatization.

The large variation is that the risk allocation did not, in practice, permit flexibility for the building contractors. The traditional implementation of design-bid-build assigned the risk to the build contractors if they made any change to the design and to the design contractors if the build contractors made no such changes. This led to defensive design: the build contractors never varied from the design, and the design contractors knew this and prescribed some overbuilding to account for risks that could be discovered later in the process, for example grouting tunnels that might not be necessary. It’s this conflict, driving up costs in Oslo, that contributed to the acceptance of design-build in Scandinavia.

But it wasn’t just the failure of one of the features of the otherwise good project delivery system. It was British soft power, and the perception that English-speaking multinational consultants with extensive experience in megaprojects that use consultants knew better than the Swedish or Danish or Finnish or Norwegian state. There was limited attention in the Nordic procurement strategy to largely traditional Germany, which does not exert this soft power on countries that are richer than Germany and speak English and not German, let alone Southern Europe, which Northern Europe constantly looks down on.

In this sense, Sweden has not been too different from France. France, too, began implementing globalized system features under the soft power of English-speaking multinationals; for all of their frothing at the mouth about France’s superiority to the UK and US, the top 1% of France wish they were the top 1% in a higher-inequality country like the US, and are happy with privatization. And in both France and Sweden, the process is being halted as its poor results are visible; Swedish public transport watchers are already noticing how the emerging system is based on the needs of large multinationals and not those of society, and in France, the delivery of Grand Paris Express in a UK/US-style single-purpose delivery vehicle (SPDV) turned into a permanent institution to build suburban rail extensions throughout France.

The invention of itemization in Italy

Italy is the only case I’m aware of in which there was a large systemic reduction in the cost of subway construction. This occurred in the environment of mani pulite, in which outrage over the endemic corruption of the Cold War-era Italian state led to massive, mediagenic investigations, forcing former Prime Minister Bettino Craxi into exile, putting half of parliament under indictment, and destroying all major political parties. The remnants of the communist party (PCI), the largest and most moderate in Europe, formed the new center-left, the present-day Democratic Party (PD); on the right, the dominant element in the coalition was previously nonpartisan media mogul Berlusconi and later the coalescence of fringe far right parties into more serious conservative blocs, currently Fratelli d’Italia (FdI).

In Italian historiography, mani pulite is rather bittersweet. Berlusconi himself was openly corrupt, and used his media influence to shut down the investigations before they could get to him as he entered politics, since he too had been involved in the corruption of the 1980s, including influence peddling with Craxi. I analogize it to civil rights in the United States, in which by the late 1960s, early-1960s optimism about ending racism was dashed, and the civil rights laws and court rulings led to a backlash symbolized by the election of Richard Nixon on a law-and-order platform. But just as the racial wage gaps in the United States markedly fell in the 1960s-70s, so did Italian infrastructure corruption levels markedly fall in the 1990s due to the legislation passed in the wake of mani pulite.

The history of itemization in Italy goes back to those post-mani pulite reforms. By the 1990s, it was clear that fighting corruption required extensive sunshine, as well as a proactive apolitical state willing to put people in prison; this was the same era of prosecutors and judges putting Cosa Nostra leaders in prison, with some being assassinated during trial and many of the others having to hide out for the duration. One can’t privatize the state in face of the mafia. The upshot is that instead of American-style rules and traditions aiming to solve the problems of the late 19th century, Italian public procurement law aims to solve those of the late 20th century.

Implementing good project delivery practices

If there’s a common theme to the various elements of Southern European (and largely also French and German) urban rail procurement norms, it’s that they require an expert civil service. Teams of engineers, planners, architects, procurement experts, and public-sector project managers are required to manage such a system, and they need to be empowered to make decisions.

This empowerment contrasts with American public-sector norms, in which to a small extent in law and to a very large extent in political culture, civil servants are constantly told that they are dregs and cannot make any decisions. Instead, they are bound by red tape requirements that can only be waived if a political appointee wants to take the risk. The United Kingdom is similar, except without the political appointees, so ministerial approval is required. Everything below that level is designed to avoid change and avoid any decisionmaking. The role of the public-sector engineer in these societies is to prostrate before the political advisor who went to the right elite universities and went through the right pipelines. The idea of listening to engineers and planners is denigrated as siloing, whereas generalist managers with little knowledge are elevated to near-godhood. Much of the growth of the globalized system in these environment comes from the fact that in privatizing planning to multibillion-dollar design-build contracts, the only public-sector decisions are made at the level of a top political leader, such as a governor, without having to deal with civil servants.

In contrast, it is less important how many civil servants are hired to supervise contracts than that they have the authority to make judgment calls and that they do not have to answer to an overclass of generalist managers. Italy and France use very large bureaucracies of planners and engineers at Metropolitana Milanese and RATP respectively, but Nordic planning always used smaller teams with more use of consultants under client supervision. In this sense, the fact that a Swedish procurement civil servant who didn’t know me was willing to tell me on the record that functional procurement doesn’t work speaks louder than any organization chart; in the United States, civil servants would never criticize their own organizations’ plans so openly.

Once the civil servants can make decisions and supervise contractors, they can look at bids and score them technically, or delve through itemized lists, or oversee changes and make quick yes-or-no decisions as the builders are forced to vary from the design. With such tight project management, they do with one dollar what 10 years ago New York procurement did with two, and what today New York does with more than two, making this the most significant single intervention in reducing infrastructure construction costs.

Transit-Oriented Development and Rail Capacity

Hayden Clarkin, inspired by the ongoing YIMBYTown conference in New Haven, asks me about rail capacity on transit-oriented development, in a way that reminds me of Donald Shoup’s critique of trip generation tables from the 2000s, before he became an urbanist superstar. The prompt was,

Is it possible to measure or estimate the train capacity of a transit line? Ie: How do I find the capacity of the New Haven line based on daily train trips, etc? Trying to see how much housing can be built on existing rail lines without the need for adding more trains

To be clear, Hayden was not talking about the capacity of the line but about that of trains. So adding peak service beyond what exists and is programmed (with projects like Penn Station Access) is not part of the prompt. The answer is that,

- There isn’t really a single number (this is a trip generation question).

- Moreover, under the assumption of status quo service on commuter rail, development near stations would not be transit-oriented.

Trip generation refers to the formula connecting the expected car trips generated by new development. It, and its sibling parking generation, is used in transportation planning and zoning throughout the United States, to limit development based on what existing and planned highway capacity can carry. Shoup’s paper explains how the trip and parking generation formulas are fictional, fitting a linear curve between the size of new development and the induced number of car trips and parked cars out of extremely low correlations, sometimes with an R^2 of less than 0.1, in one case with a negative correlation between trip generation and development size.

I encourage urbanists and transportation advocates and analysts to read Shoup’s original paper. It’s this insight that led him to examine parking requirements in zoning codes more carefully, leading to his book The High Cost of Free Parking and then many years of advocacy for looser parking requirements.

I bring all of this up because Hayden is essentially asking a trip generation question but on trains, and the answer there cannot be any more definitive than for cars. It’s not really possible to control what proportion of residents of new housing in a suburb near a New York commuter rail stop will be taking the train. Under current commuter rail service, we should expect the overwhelming majority of new residents who work in Manhattan to take the train, and the overwhelming majority of new residents who work anywhere else to drive (essentially the only exception is short trips on commuter rail, for example people taking the train from suburbs past Stamford to Stamford; those are free from the point of view of train capacity). This is comparable mode choice to that in the trip and parking generation tables, driven by an assumption of no alternative to driving, which is correct in nearly all of the United States. However, figuring out the proportion of new residents who would be commuting to Manhattan and thus taking the train is a hard exercise, for all of the following reasons:

- The great majority of suburbanites do not work in the city. For example, in the Western Connecticut and Greater Bridgeport Planning Regions, more or less coterminous with Fairfield County, 59.5% of residents work within one of these two regions, and only 7.4% work in Manhattan as of 2022 (and far fewer work in the Outer Boroughs – the highest number, in Queens, is 0.7%). This means that every new housing unit in the suburbs, even if it is guaranteed the occupant works in Manhattan, generates demand for more destinations within the suburb, such as retail and schools.

- The decision of a city commuter to move to the suburbs is not driven by high city housing prices. The suburbs of New York are collectively more expensive to live in than the city, and usually the ones with good commuter rail service are more expensive than other suburbs. Rather, the decision is driven by preference for the suburbs. This means that it’s hard to control where the occupant of new suburban housing will work purely through TOD design characteristics such as proximity to the station, streets with sidewalks, or multifamily housing.

- Among public transportation users, what time of day they go to work isn’t controllable. Most likely they’d commute at rush hour, because commuter rail is marginally usable off-peak, but it’s not guaranteed, and just figuring the proportion of new users who’d be working in Manhattan at rush hour is another complication.

All of the above factors also conspire to ensure that, under the status quo commuter rail service assumption, TOD in the suburbs is impossible except perhaps ones adjacent to the city. In a suburb like Westport, everyone is rich enough to afford one car per adult, and adding more housing near the station won’t lower prices by enough to change that. The quality of service for any trip other than a rush hour trip to Manhattan ranges from low to unusable, and so the new residents would be driving everywhere except their Manhattan job, even if they got housing in a multifamily building within walking distance of the train station.

This is a frustrating answer, so perhaps it’s better to ask what could be modified to ensure that TOD in the suburbs of New York became possible. For this, I believe two changes are required:

- Improvements in commuter rail scheduling to appeal to the growing majority of off-peak commuters as well as to non-commute trips. I’ve written about this repeatedly as part of ETA but also the high-speed rail project for the Transit Costs Project.

- Town center development near the train station to colocate local service functions there, including retail, a doctor’s office and similar services, a library, and a school, with the residential TOD located behind these functions.

The point of commercial and local service TOD is to concentrate destinations near the train station. This permits trip chaining by transit, where today it is only viable by car in those suburbs. This also encourages running more connecting bus service to the train station, initially on the strength of low-income retail workers who can’t afford a car, but then as bus-rail connections improve also for bus-rail commuters. The average income of a bus rider would remain well below that of a driver, but better service with timed connections to the train would mean the ridership would comprise a broader section of the working class rather than just the poor. Similarly, people who don’t drive on ideological or personal disability grounds could live in a certain degree of comfort in the residential TOD and walk, and this would improve service quality so that others who can drive but sometimes choose not to could live a similar lifestyle.

But even in this scenario of stronger TOD, it’s not really possible to control train capacity through zoning. We should expect this scenario to lead to much higher ridership without straining capacity, since capacity is determined by the peak and the above outline leads to a community with much higher off-peak rail usage for work and non-work trips, with a much lower share of its ridership occurring at rush hour (New York commuter rail is 67-69%, the SNCF part of the RER and Transilien are about 46%, due to frequency and TOD quality). But we still have no good way of controlling the modal choice, which is driven by personal decisions depending on local conditions of the suburb, and by office growth in the city versus in the suburbs.

High-Speed Rail Ridership Estimator Applet

Thijs Niks made a web applet for calculating high-speed rail network ridership estimates. This is based on the gravity model that I’ve used to construct estimates. The applet lets one add graph nodes representing metro areas and edges representing connections between them. It estimates ridership based on the model, construction costs based on a given choice of national construction costs, and overall profitability after interest. It can also automate the exact distances and populations, using estimates of population within a radius of 30 km from a point, and estimates of line length based on great circle length. The documentation can be found here and I encourage people to read it.

This is a very good way of visualizing certain things both about high-speed rail networks and the implications of a pure gravity model. For one, Metcalfe’s law is in full swing, to the point that adding to a network improves its finances through adding more city pairs than just the new edges. The German network overall is deemed to have insufficient financial rate of return due to the high costs of construction (and due to a limitation in the applet, which is that it assumes all links cost like high-speed rail, even upgraded classical lines like Berlin-Hamburg). But if the network is augmented with international connections to Austria, Czechia, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and Switzerland, then it moves into the black.

To be clear, this is not a conclusion of the applet. Rather, the applet is a good visualization that this is a conclusion of the model. The model, with the following formula,

is open to critique. The minimum distance d can be empirically derived from ridership along a line with intermediate stops; I use 500 km, or around a trip time of 2:15. The constant c is different in different geographies, and I don’t always have a good explanation for it. The TGV has a much higher constant than the Shinkansen (by a factor of 1.5), which can be explained by its much lower fares (a factor of about 1.7). But Taiwan HSR has a much higher constant than either, with no such obvious explanation. This is perilous, because Taiwan is a much smaller country than the others for which I’ve tested the model (Japan, South Korea, France, Germany, Spain, Italy). There may be reason to believe that at large scale, c should be lower for higher-population geographies, like the entirety of Europe; the reason is that if c is truly independent of population size, then the model implies that the propensity to travel per individual is not constant, but rather is larger in larger geographies, with an exponent of 0.6. This could to some extent be resolved if we have robust Chinese data – but China has other special elements that make a straight comparison uncertain, namely much lower incomes (reducing travel) and much higher average speeds (increasing travel).

The other issue is that the value of c used in the applet is much higher than the one I use. I use 75,000 for Shinkansen and 112,500 for Europe, with the populations of the metro areas stated in millions of people, the distance given in kilometers, and the ridership given in millions of riders per year. The applet uses 200,000, because its definition of metro area is not taken from national lists but from a flat applet giving the population in a 30 km radius from a point, which reduces Paris from 13 million people to 10.3 million people; it also omits many secondary cities in France that get direct TGVs to the capital, most notably Saint-Etienne and Valence, collectively dropping 12% of the modeled Paris-PACA ridership and 37% of the Paris-Rhône-Alpes ridership. (Conversely, the same method overestimates the size of metro Lille.)

Potentially, if the definition of a metro area is the population within a fixed radius, then the 0.8 exponent may need to be replaced with 1, since the fixed radius already drops many of the suburbs of the largest cities. The reason the gravity model has an exponent of 0.8 and not 1 is that larger metro areas have diseconomies of scale, as the distance from the average residence to the train station grows. Empirically, splitting combined statistical areas in the US into smaller metro areas and metropolitan divisions fits an exponent of 0.8 rather than 1, as some of those divisions (for example, Long Island) don’t have intercity train stations and have a longer trip time; it is fortunate that training the same model on Tokyo-to-secondary city Shinkansen ridership results in the same 0.8 exponent. However, if the definition of the metropolitan area is atypically unfair to New York and other megacities then the exponent is likely better converted to the theoretically simpler 1.

Timetable Padding Practices

Two weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal wrote this piece about our Northeast Corridor report. Much of it was based on a series of interviews William Boston did with me, explaining what the main needs on the corridor are. One element stands out since the MTA responded to what I was saying about schedule padding – I talk about how Amtrak and Metro-North both pad the timetables on the Northeast Corridor by about 25%, turning a technical travel time of an hour into 1:15 (best practices are 7%), and in response, the MTA said that they pad their schedules 10% and not 7%. This is an incorrect understanding of timetable padding, which speaks poorly to the competence of the schedule planners and managers at Metro-North.

The article says,

Aaron Donovan, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, says the extra time built into Metro-North schedules generally averages 10%, depending on destination and length of trips, and takes into account routine track maintenance and capital work that can increase runtime. Metro-North continually reviews models, signal timing, equipment, and other elements of operation to improve travel times and reliability for customers, he says.

This is, to be clear, incorrect. Metro-North routinely recovers longer delays than 10%; delay recovery on the New Haven Line can reach well over 20 minutes out of a nominally two-hour trip, around 25% of the unpadded trip length. The reason this is incorrect isn’t that Donovan is dishonest or incompetent (he is neither of these two things), but almost certainly that the planners he spoke with genuinely believe they only pad 10%, because they, like all American railroaders, do not know how modern rail scheduling is done.

Modern rail scheduling practices in the higher-reliability parts of Europe and Japan start with the technical timetable, based on the actual speed zones and trains’ performance characteristics. This includes temporary speed restrictions. The ideal maintenance regime does not use them, instead relying on regular nighttime maintenance windows during which all tracks are out of service. However, temporary restrictions may exist if a line is taken out of service and trains are rerouted along a slower route, which is regrettably common in Germany. Modern signaling systems are capable of incorporating temporary speed restrictions – this is in fact a core requirement for American positive train control (PTC), since American maintenance practices rely on extensive temporary restrictions for work zones and one-off slowdowns. If the signal system knows the exact speed zones on each section of track, then so can the schedule planners.

The schedule contingency figure is computed relative to the best technical schedule. It is not computed relative to any assumption of additional delays due to dispatch holds or train congestion. The 7% figure used in Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands takes care of the high levels of congestion on key urban segments.

The core urban networks in these countries stack favorably with Metro-North in track utilization. The Hirschengraben Tunnel in Zurich runs 18 S-Bahn trains per hour in each direction most of the day and 20 at rush hour with some extra S20 runs, and the Weinberg Tunnel runs 8 S-Bahn trains per hour and if I understand the network graphic right 7.5 additional intercities per hour. I urge people to go look at the graphic and try tracking down the lines just to see how extensively branched and reverse-branched they are; this is not a simple network, and delays would propagate. The reason the Swiss rail network is so punctual is that, unlike American rail planning, it integrates infrastructure and timetable development. This means many things, but what is relevant here is that it analyzes where delays originate and how they propagate, and focuses investments on these sections, grade-separating problematic flat junctions if possible and adding pocket tracks if not.

Were I to only take timetable padding into account relative to an already more tolerant schedule incorporating congestion and signaling limitations, I would cite much lower figures for timetable padding. Switzerland speaks of a uniform 7% pad, but in Sweden the figures include two components, a percentage (taking care of, among other things, suboptimal driver behavior) and a fixed number of minutes per 100 km, which at current intercity speeds resolve to 7% as in Switzerland. But relative to the technical trip time, the pad factors based on both observed timetable recovery and actual calculations on current speed zones are in the 20-30% range, and not 10%.

Of course, at no point do I suggest that Metro-North and Amtrak could achieve 7% right now, through just writing more aggressive timetables. To achieve Swiss, Dutch, and Swedish results, they would need Swiss, Dutch, or Swedish planning quality, which is sorely lacking at both railroads. They would need to write better timetables – not just more aggressive ones but also simpler ones: Metro-North’s 13 different stopping patterns on New Haven Line trains out of 16 main line peak trains per hour should be consolidated to 2. This is key to the plan – the only way Northern Europe makes anything work is with fairly rigid clockface timetables, so that one hour or half-hour is repeated all day, and conflicts can be localized to be at the same place every time.

Then they would need to invest based on reliability. Right now, the investment plans do not incorporate the timetable, and one generally forward-thinking planner found it odd that the NEC report included both high-level infrastructure proposals and proposed timetables to the minute. In the United States, that’s not the normal practice – high-level plans only discuss high-level issues, and scheduling is considered a low-level issue to be done only after the concrete is completed. In Northern European countries with competently-run railways and also in Germany, the integration of the timetable and infrastructure is so complete that draft network graphics indicating complete timetables of every train to the minute are included in the proposal phase, before funding is committed. In Switzerland, such a timetable is available before the associated infrastructure investments go to referendum.

Under current American planning, the priorities for Metro-North are in situ bridge replacements in Connecticut because their maintenance costs are high even by Metro-North’s already very expensive standards. But under good planning, the priority must be grade-separating Shell Interlocking (CP 216) just south of New Rochelle, currently a flat junction between trains bound for Grand Central and ones bound for Penn Station. The flat junctions to the branches in Connecticut need to be evaluated for grade-separation as well, and I believe the innermost, to the New Canaan Branch, needs to be grade-separated due to its high traffic while the ones to the two farther out branches can be kept flat.

None of this is free, but all of this is cheap by the standards of what the MTA is already spending on Penn Station Access for Metro-North. The rewards are substantial: 1:17 trip times from New Haven to Grand Central making off-peak express stops, down from 2 hours today. The big ask isn’t money – the entire point of the report is to figure out how to build high-speed rail on a tight budget. Rather, the big ask is changing the entire planning paradigm of intercity and commuter rail in the United States from reactive to proactive, from incremental to comfortable with groun-up redesigns, from stuck in the 1950s to ready for the transportation needs of the 21st century.

Reasons and Explanations

David Schleicher has a proposal for how Congress can speed up infrastructure construction and reduce costs for megaprojects. Writing about what further research needs to be done, he distinguishes reasons from explanations.

I have argued that many of the stories we tell about infrastructure costs involve explanations but not reasons. There are plenty of explanations for why projects cost so much, from too-deep train stations to out-of-control contractors, but they don’t help us understand why politicians often seem not to care about increasing costs. For that, we need to understand why there is insufficient political pressure to encourage politicians to do better.

I hope in this post to go over this distinction in more detail and suggest reasons. The key here is to look not just at costs per kilometer, but also costs per rider, or benefit-cost ratios in general. The American rail projects that are built tend to have very high benefits, to the point that at normal costs, their benefit-cost ratios would be so high that they’d raise the question of why it didn’t happen generations ago. (If New York’s construction costs had stayed the same as those of London and Paris in the 1930s, then Second Avenue Subway would have opened in the 1950s from Harlem to Lower Manhattan.) The upshot is that such projects have decent benefit-cost ratios even at very high costs, which leads to the opposite political pressure.

Those high benefit-cost ratios can be seen in low costs per rider, despite very high costs per kilometer. Second Avenue Subway Phase 1 cost $6 billion in today’s money and was projected to get 200,000 daily riders, which figure it came close to before the pandemic led to reductions in ridership. $30,000/rider is perfectly affordable in a developed country; Grand Paris Express, in 2024 prices, is estimated to cost 45 billion € and get 2 million daily riders, which at PPP conversion is if anything a little higher than for Second Avenue Subway. And the United States is wealthier than France.

I spoke to Michael Schabas in 2017 or 2018 about the Toronto rail electrification project, asking about its costs. He pointed out to me that when he was involved in the early 2010s studies for it, the costs were only mildly above European norms, but the benefits were so high that the benefit-cost ratio was estimated at 8. Such a project could only exist because Canada is even more of a laggard on passenger rail electrification than the United States – in Australia, Europe, Japan, or Latin America a system like GO Transit would have been electrified generations earlier, when the benefit-cost ratio would have been solid but not 8. The ratio of 8 seemed unbelievable, so Metrolinx included 100% contingency right from the start, and added scope instead of fighting it – the project was going to happen at a ratio of 2 or 8, and the extra costs bringing it down to 2 are someone else’s revenue.

The effect can look, on the surface, as one of inexperience: the US and Canada are inexperienced with projects like passenger rail electrification, and so they screw them up and costs go up, and surely they’ll go down with experience. But that’s not quite what’s happening. Costs are very high even for elements that are within the American (or Canadian) experience, such as subway and light rail lines, often built continuously in Canadian and Western US cities. Rather, what’s going on is that if a feature has been for any reason underrated (in this case, mainline rail electrification, due to technological conservatism), then by the time anyone bothers building it, its benefit-cost ratio at normal costs will be very high, creating pressure to add more costs to mollify interest groups that know they can make demands.

This effect even happens outside the English-speaking world, occasionally. Parisian construction costs for metro and RER tunnels are more or less the world median. Costs for light rail are high by French standards and low by Anglosphere ones. However, wheelchair accessibility is extremely expensive: Valérie Pécresse’s plan to retrofit the entire Métro with elevators, which are currently only installed on Line 14, is said to cost 15 to 20 billion euros. There are 300 stations excluding Line 14, so the cost per station, at 50-67 million € is even higher than in New York. In Madrid, a station is retrofit with four elevators for about 10 million €; in Berlin, they range between 2 and 6 million (with just one to two elevators needed; in Paris, three are needed); in London, a tranche of step-free access upgrades beginning in 2018 cost £200 million for 13 stations. This is not because France is somehow inexperienced in this – such projects happen in secondary cities at far lower costs. Moreover, when France is experimenting with cutting-edge technology, like automation of the Métro starting with Line 1, the costs are not at all high. Rather, what’s going on with accessibility costs is that Paris is so tardy with upgrading its system to be accessible that the benefits are enormous and there’s political pressure to spend a lot of money on it and not try saving much, not when only one line is accessible.

In theory, this reason should mean that once the projects with the highest benefit-cost ratios are built, the rest will have more cost control pressure. However, one shouldn’t be so optimistic. When a country or city starts out building expensive infrastructure, it gets used to building in a certain way, and costs stay high. Taiwanese MRT construction costs began high in the 1990s, and the result since then has not been cost control pressure as more marginal lines are built, but fewer lines built, and rather weak transit systems in the secondary cities.

Major reductions happen only in an environment of extreme political pressure. In Italy, the problem in the 1980s was extensive corruption, which was solved through mani pulite, a process that put half of parliament under indictment and destroyed all extant political parties, and reforms passed in its wake that increased transparency and professionalized project delivery. High costs by themselves do not guarantee such pressure – there is none in Taiwan or the United Kingdom. In the United States there is some pressure, in the sense that the thinktanks are aware of the problem and trying to solve it and there’s a decent degree of consensus across ideologies about how. But I don’t think there’s extreme political pressure – if anything the tendency for local activist groups is to work toward the same failed leadership that kept supervising higher costs, whereas mani pulite was a search-and-destroy operation.

Without such extreme pressure, what happens is that a very strong project like Caltrain or GO Transit electrification, the MBTA Green Line Extension, the Wilshire subway, or Second Avenue Subway is built, and then few to no similar things can be, because people got used to doing things a certain way. The project managers who made all the wrong decisions that let costs explode are hailed as heroes for finally completing the project and surmounting all of its problems, never mind that the problems were caused either by their own incompetence or that of predecessors who weren’t too different from them. The regulations are only tweaked or if anything tightened if a local political power broker feels not listened to. Countries and cities build to a certain benefit-cost ratio frontier, and accept the cost of doing business up to it; the result is just that fewer things are built in high cost per kilometer environments.

How One Bad Project Can Poison the Entire Mode

There are a few examples of rail projects that fail in a way that poisons the entire idea among decisionmakers. The failures can be total, to the point that the project isn’t built and nobody tries it again. Or the outcome can be a mixed blessing: an open project with some ridership, but not enough compared with the cost or hassle, with decisionmakers still choosing not to do this again. The primary cases I have in mind are Eurostar and Caltrain electrification, both mixed blessings, which poisoned international high-speed rail in Europe and rail electrification in the United States respectively. The frustrating thing about both projects is that their failures are not inherent to the mode, but rather come from bad project management and delivery, which nonetheless is taken as typical by subsequent planners, who benchmark proposals to those failed projects.

Eurostar: Flight Level Zero airline

The infrastructure built for Eurostar is not at all bad: the Channel Tunnel, and the extensions of the LGV Nord thereto and to Brussels. The UK-side high-speed line, High Speed 1, had very high construction costs (about $160 million/km in today’s prices), but it’s short enough that those costs don’t matter too much. The concept of connecting London and Paris by high-speed rail is solid, and those trains get a strong mode share, as do trains from both cities to Brussels.

Unfortunately, the operations are a mess. There’s security and border control theater, which is then used as an excuse to corral passengers into airline-style holding areas with only one or two boarding queues for a train of nearly 1,000 passengers. The extra time involved, 30 minutes at best and an hour at worst, creates a serious malus to ridership – the elasticity of ridership with respect to travel time in the literature I’ve seen ranges from -1 to -2, and at least in the studies I’ve read about local transit, time spent out of vehicle usually counts worse than time spent on a moving train (usually a factor of 2). It also holds up tracks, which is then used as an excuse not to run more service.

The excusemaking about service is then used to throttle the service offer, and raise prices. As I explain in this post, the average fare on domestic TGVs is 0.093€/passenger-km, whereas that on international TGV services (including Eurostar) is 0.17€/p-km, with the Eurostar services costing more than Lyria and TGV services into Germany. This includes both Eurostar to London and the services between Paris and Brussels, which used to be called Thalys, which have none of the security and border theater of London and yet charge very high fares, with low resulting ridership.

The origin of this is that Eurostar was conceived as a partnership between British and French elites, in management as well as the respective states. They thought of the Chunnel as a flashy project, fit for high-end service, designed for business travelers. SNCF management itself believes in airline-style services, with fares that profiteer off of riders; it can’t do it domestically due to public pressure to keep the TGV affordable to the broad public, but whenever it is freed from this pressure, it builds or recommends that others build what it thinks trains should be like, and the results are not good.

What rail advocates have learned from this saga is that cross-border rail should decenter high-speed rail. Their first association of cross-border high-speed rail is Eurostar, which is unreasonably expensive and low-ridership even without British border and security theater. Thus, the community has retreated from thinking in terms of infrastructure, and is trying to solve Eurostar’s problem (not enough service) even on lines where they need competitive trip times before anything else. Why fight for cross-border high-speed rail if the only extant examples are such underperformers?

This dovetails with the mentality that private companies do it better than the state, which is dominant at the EU level, as the eurocrats prefer not to have any visible EU state. This leads to ridiculous press releases by startups that lie to the public or to themselves that they’re about to launch new services, and consultant slop that treats rail services as if they are airlines with airline cost structures. Europe itself gave up on cross-border rail infrastructure – the EU is in panic mode on all issues, the states that would be building this infrastructure (like Belgium on Brussels-Antwerp) don’t care, and even bilateral government agreements don’t touch the issue, for example France and Germany are indifferent.

Caltrain: electrification at extreme costs

In the 2010s, Caltrain electrified its core route from San Francisco to Tamien just south of San Jose Diridon Station, a total length of 80 km, opening in 2024. This is the only significant electrification of a diesel service in the United States since Amtrak electrified the Northeast Corridor from New Haven to Boston in the late 1990s. The idea is excellent: a dense corridor like this with many stations would benefit greatly from all of the usual advantages of electrification, including less pollution, faster acceleration, and higher reliability.

Unfortunately, the costs of the project have been disproportionate to any other completed electrification program that I am aware of. The entire Caltrain Modernization Project cost $2.4 billion, comprising electrification, resignaling (cf. around $2 million/km in Denmark for ETCS Level 2), rolling stock, and some grade crossing work. Netting out the elements that are not direct electrification infrastructure, this is till well into the teens of millions per kilometer. Some British experiments have come close, but the RIA Electrification Challenge overall says that the cost on double track is in the $3.8-5.7 million/km range in today’s prices, and typical Continental European costs are somewhat lower.

The upshot is that Americans, never particularly curious about the world outside their border, have come to benchmark all electrification projects to Caltrain’s costs. Occasionally they glance at Canada, seeing Toronto’s expensive electrification project and confirming their belief that it is far too expensive. They barely look at British electrification projects, and never look at ones outside the English-speaking world. Thus, they take these costs as a given, rather than as a failure mode, due to poor design standards, poor project management, a one-off signaling system that had very high costs by American standards, and inflexible response to small changes.

And unfortunately, there was no pot of gold at the end of the Caltrain rainbow. Ridership is noticeably up since electric service opened, but is far below pre-corona levels, as the riders were largely tech workers and the tech industry went to work-from-home early and has still not quite returned to the office, especially not in the Bay Area. This one failure, partly due to unforeseen circumstances, partly due to poor management, has led to the poisoning of overhead wire electrification throughout the United States.

Did the Netherlands Ever Need 300 km/h Trains?

Dutch high-speed rail is the original case of premature commitment and lock-in. A decision was made in 1991 that the Netherlands needed 300 km/h high-speed rail, imitating the TGV, which at that point was a decade old, old enough that it was a clear success and new enough that people all over Europe wanted to imitate it to take advantage of this new technology. This decision then led to complications that caused costs to run over, reaching levels that still hold a European record, matched only by the almost entirely tunneled Florence-Bologna line. But setting aside the lock-in issue, is it good for such a line to run at 300 km/h?

The question can be asked in two ways. The first is, given current constraints on international rail travel, did it make sense to build HSL Zuid at 300 km/h?. It has an easy answer in the negative, due to the country’s small size, complications in Belgium, and high fares on international trains. The second and more interesting is, assuming that Belgium completes its high-speed rail network and that rail fares drop to those of domestic TGVs and ICEs, did it make sense to build HSL Zuid at 300 km/h?. The answer there is still negative, but the reasons are specific to the urban geography of Holland, and don’t generalize as well.

How HSL Zuid is used today

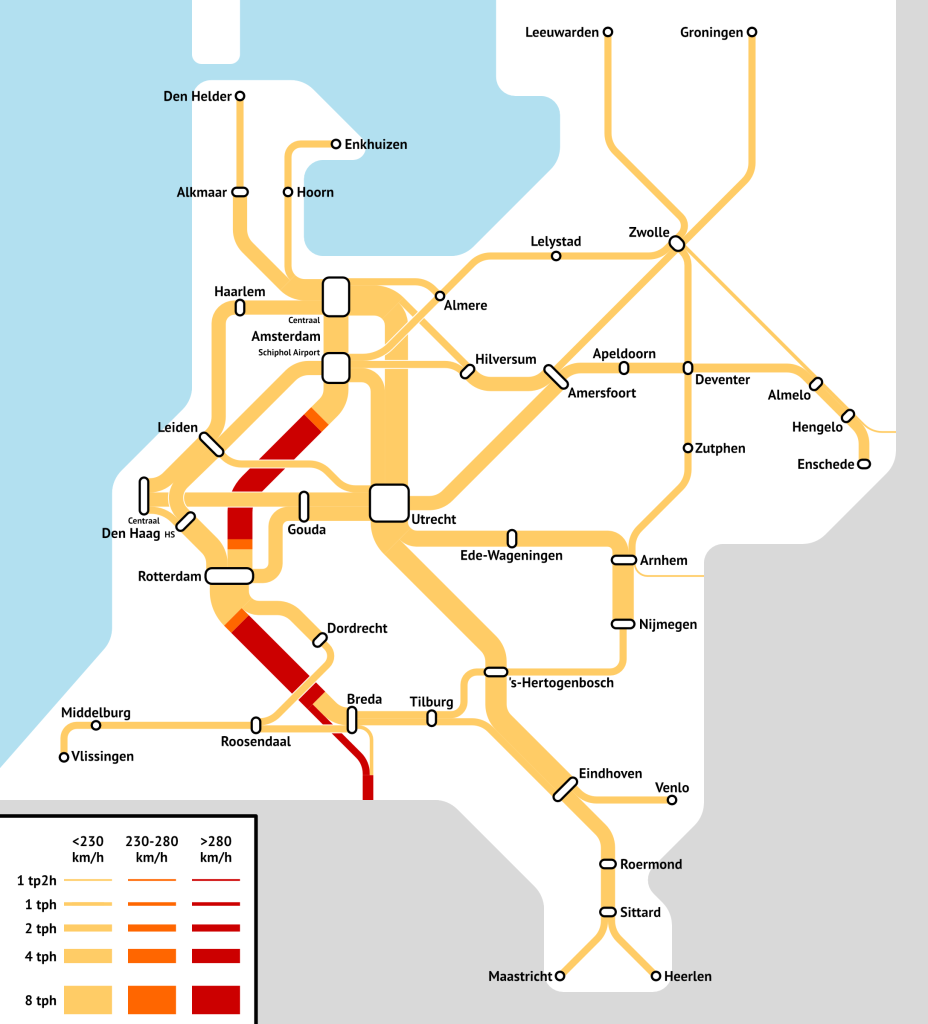

This is a schematic of Dutch lines branded as intercity. The color denotes speed and the thickness denotes frequency.

The most important observation about this system is that HSL Zuid is not the most frequent in the country. Frequency between Amsterdam and Utrecht is higher than between Amsterdam and Rotterdam; the frequency stays high well southeast of Utrecht, as far as Den Bosch and Eindhoven. The Dutch rail network is an everywhere-to-everywhere mesh with Utrecht as its central connection point, acting as the main interface between Holland in the west and the rest of the country in the east. HSL Zuid is in effect a bypass around Utrecht, faster but less busy than the routes that do serve Utrecht.

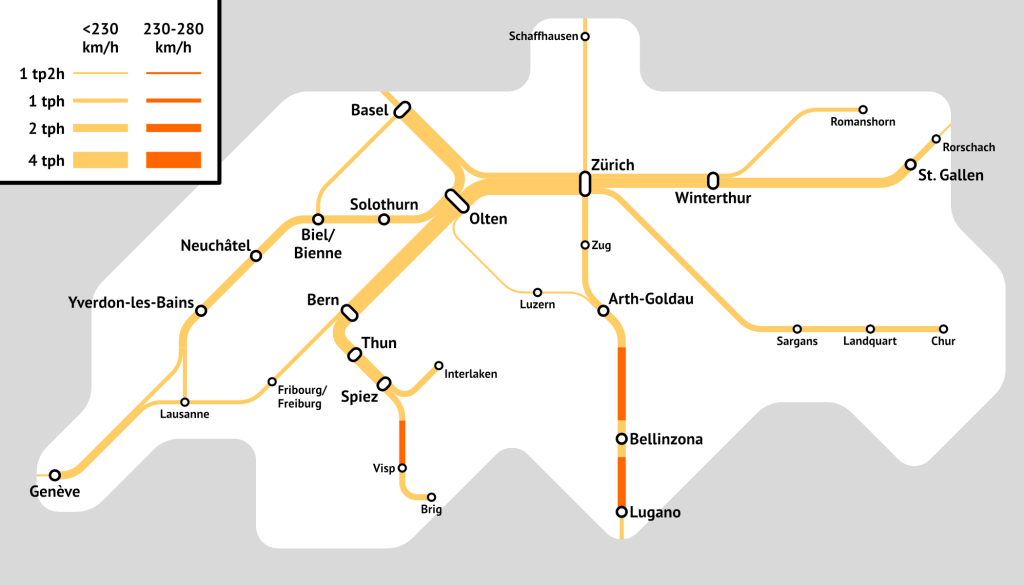

This needs to be compared with the other small Northern European country with a very strong legacy rail network, Switzerland. The map, with the same thickness and color scheme but not the same length scale, is here:

The orange segments are Alpine base tunnels, with extensive freight rail. The main high-cost investment in passenger-dedicated rail in Switzerland is not visible on the map, because it was built for 200 km/h to reduce costs: Olten-Bern, with extensive tunneling as well as state-of-the-art ETCS Level 2 signaling permitting 110 second headways. The Swiss rail network is centered not on one central point but on a Y between Zurich, Basel, and Bern, and the line was built as one of the three legs of the Y, designed to speed up Zurich-Bern and Basel-Bern trains to be just less than an hour each, to permit on-the-hour connections at all three stations.

By this comparison, HSL Zuid should not have been built this way. It is not useful for a domestic network designed around regular clockface frequencies and timed connections, in the Netherlands as much as in Switzerland. There is little interest in further 300 km/h domestic lines – any further proposals for increasing speeds on domestic trains are at 200 km/h, and as it is the domestic trains only go 160. In a country this size, so much time is spent on station approaches that the overall benefit of high top speed is reduced. Indeed, from Antwerp to Amsterdam, Eurostar trains take 1:20 over a distance of 182 km, an average speed comparable to the fastest classical lines in Europe such as the East Coast Main Line or the Southern Main Line in Sweden. The heavily-upgraded but still legacy Berlin-Hamburg line averages about 170 km/h when the trains are on time, and if German trains ran with Dutch punctuality and Dutch padding it would average 190 km/h.

What about international services?

The fastest trains using HSL Zuid are international, formerly branded Thalys, now branded Eurostar. They are also unfathomably expensive. Where NS’s website will sell me Amsterdam-Antwerp tickets for around 20€ if I’m willing to chain trips on slow regional trains, or 27€ on intercities doing the trip in 1:37 with one transfers, Eurostar charges 79-99€ for this trip when I look up available trains in mid-August on a weekday. For reference, the average domestic TGV trip over this distance is around 18€ and the average domestic ICE trip is around 22€. It goes without saying that the line is underused by international travelers – the fares are prohibitive.

Beyond Antwerp, the other problem is that Belgium has built HSL 1 from the French border to Brussels, HSL 2 and 3 from Leuven to the German border, and HSL 4 from Antwerp to the Dutch border, but has not bothered building a fast line between Brussels and Antwerp (or Leuven). The 46 km line between Brussels South and Antwerp Central takes 46 minutes by the fastest train. A 200 km/h high-speed line would do the trip in about 20, skipping Brussels Central and North as the Eurostars do.

But what if the fares were more reasonable and if Belgian trains weren’t this slow? Then, we would expect to see a massive increase in ridership, since the line would be connecting Amsterdam with Brussels in 1:40 and Paris in slightly more than three hours, with fares set at rates that would get the same ridership seen on domestic trains. The line would get much higher ridership.

And yet the trip time benefits of 300 km/h on HSL Zuid over 250 km/h are only 3 minutes. While much of the line is engineered for 300, the line is really two segments, one south of Rotterdam and one north of it, totaling 95 km of 300 km/h running plus extensive 200 and 250 km/h connections, and the total benefit to the higher top speed net of acceleration and deceleration time is only about 3 minutes. The total benefit of 300 km/h relative to 200 km/h is only about 8 minutes.

Two things are notable about this geography. The first is that the short spacing between must-serve stations – Amsterdam, Schiphol, Rotterdam, Antwerp – means that trains never get the chance to run fast. This is partly an artifact of Dutch density, but not entirely. England is as dense as the Netherlands and Belgium, but the plan for HS2 is to run nonstop trains between London and Birmingham, because between them there is nothing comparable in size or importance to Birmingham. North Rhine-Westphalia is about equally dense, and yet trains run nonstop between Cologne and Frankfurt, averaging around 170 km/h despite extensive German timetable padding and a slow approach to Cologne on the Hohenzollernbrücke.

The second is that the Netherlands is not a country of big central cities. Randstad is a very large metropolitan area, but it is really an agglomeration of the separate metro areas for Amsterdam, Rotterdam, the Hague, and Utrecht, each with its own set of destinations. The rail network needs to serve this geography with either direct trains or convenient transfers to all of the major centers. HSL Zuid does not do that – it has an easy transfer to the Hague at Rotterdam, but connecting to Utrecht (thus with the half of the Netherlands that isn’t Holland) is harder.

In retrospect, the Netherlands should have built more 200 and 250 km/h lines instead of building HSL Zuid. It could have kept the higher speed to Rotterdam but then built direct Rotterdam-Amsterdam and Rotterdam-Utrecht lines topping at 200 km/h, using the lower top speed to have more right-of-way flexibility to avoid tunnels. Separate trains would be running from points south to either Amsterdam or Utrecht, and fares in line with those of domestic trains would keep demand high enough that the frequency to both destinations would be acceptable.

In contrast, 300 km/h lines, if there are no slow segments like Brussels-Antwerp in their midst and if fares are reasonable, can be successful, if the single-core cities served are larger and the distances between stations are longer. The distances do not need to be as long as on some LGVs, with 400 km of nonstop running between Paris and Lyon – on a 100 km nonstop line, such as the plans for Hanover-Bielefeld including approaches or just the greenfield segment on Hamburg-Hanover, the difference between 200 and 300 km/h is 9 minutes, so about twice as much as on HSL Zuid and HSL 4 relative to their total length. This works, because while western Germany is dense much like the Netherlands, it is mostly a place of larger city cores separated by greater distances. The analogy to HSL Zuid elsewhere in Europe is as if Germany decided to build a line to 300 km/h standards internally to the Rhine-Ruhr region, or if the UK decided to build one between Liverpool and Manchester.