Category: Transportation

Can Ridership Surges Disrupt Small, Frequent Driverless Metros?

A recent discussion about the Nuremberg U-Bahn got me thinking about the issue of transfers from infrequent to frequent vehicles and how they can disrupt service. The issue is that driverless metros like Nuremberg’s rely on very high frequency on relatively small vehicles in order to maintain adequate capacity; Nuremberg has the lowest U-Bahn construction costs in Germany, and Italian cities with even smaller vehicles use the combination of short stations and very high frequency to reduce costs even further. However, all of this assumes that passengers arrive at the station evenly; an uneven surge could in theory overwhelm the system. The topic of the forum discussion was precisely this, but it left me unconvinced that such surges could be real on a driverless urban metro (as opposed to a landside airport people mover). The upshot is that there should not be obstacles to pushing the Nuremberg U-Bahn and other driverless metros to their limit on frequency and capacity, which at this point means 85-second headways as on the driverless Parisian lines.

What is the issue with infrequent-to-frequent transfers?

Whenever there is a transfer from a large, infrequent vehicle to a small, frequent one, passengers overwhelm systems that are designed around a continuous arrival rate rather than surges. Real-world examples include all of the following:

- Transfers from the New Jersey Transit commuter trains at the Newark Airport station to the AirTrain.

- Transfers from OuiGo TGVs at Marne-la-Vallée to the RER.

- In 2009, transfers from intercity CR trains at Shanghai Station to the metro.

In the last two cases, the system that is being overwhelmed is not the trains themselves, which are very long. Rather, what’s being overwhelmed is the ticket vending machines: in Shanghai the TVMs frequently broke, and with only one of three machines at the station entrance in operation, there was a 20-minute queue. A similar queue was observed at Marne-la-Vallée. Locals have reusable farecards, but non-locals would not, overwhelming the TVM.

In the first case, I think the vehicles themselves are somewhat overwhelmed on the first train that the commuter train connects to, but that is not the primary system capacity issue either. Rather, the queues at the faregates between the two systems can get long (a few minutes, never 20 minutes).

In contrast, I have never seen the transfer from the TGV to the Métro break the system at Gare de Lyon. The TGV may be unloading 1,000 passengers at once, but it takes longer for all of them to disembark than the headway between Métro trains; I’ve observed the last stragglers take 10 minutes to clear a TGV Duplex in Paris, and between that, long walking paths from the train to the Métro platforms, and multiple entrances, the TGV cannot meaningfully be a surge. Nor have I seen an airplane overwhelm a frequent train, for essentially the same reason.

What about school trips?

The forum discussion brings up two surges that limit the capacity of the Nuremberg U-Bahn: the airport, and school trips. The airport can be directly dispensed with – individual planes don’t do this at airside people movers, and don’t even do this at low-capacity landside people movers like the JFK and Newark AirTrains. But school trips are a more intriguing possibility.

What is true is that school trips routinely overwhelm buses. Students quickly learn to take the last bus that lets them make school on time: this is the morning and they don’t want to be there, so they optimize for how to stay in bed for just a little longer. Large directional commuter volumes can therefore lead to surges on buses: in Vancouver, UBC-bound buses routinely have passups in the morning rush hour, because classes start at coordinated times and everyone times themselves to the last bus that reaches campus on time.

However, the UBC passups come from a combination of factors, none of which is relevant to Nuremberg:

- They’re on buses. SkyTrain handles surges just fine.

- UBC is a large university campus tucked at the edge of the built-up area.

- UBC has modular courses, as is common at American universities, and coordinated class start and end times (on the hour three days a week, every 1.5 hours two days a week).

It is notable that Vancouver does not have any serious surges coming from school trips, even with trainsets that are shorter than those of Nuremberg (40 meters on the Canada Line and 68-80 meters on the Expo and Millennium lines, compared with 76 meters). Schools are usually sited to draw students from multiple directions, and are usually not large enough to drive much train crowding on their own. A list on Wikipedia has the number of students per Gymnasium, and they’re typically high three figures with one at 1,167, none of which is enough to overwhelm a driverless 76 meter long train. Notably, school trips do not overwhelm the New York City Subway; New York City Subway rolling stock ranges from 150 to 180 meters long rather than 76 as in Nuremberg, but then the specialized high schools go as far up as 5,800 students, and one has 3,000 and is awkwardly located in the North Bronx.

Indeed, neither Vancouver nor New York schedules its trains based on whether school is in session. Both run additional buses on school days to avoid school surges, but SkyTrain and the subway do not run additional vehicles, and in both formal planning and informal railfan lore about crowding, school trips are not considered important. So school surges are absolutely real on buses, and university surges are real everywhere, but not enough to overwhelm trains. Nuremberg should not consider itself special on this regard, and can plan its U-Bahn systems as if it does not have special surges and passengers do arrive continuously at stations.

The Hamburg-Hanover High-Speed Line

A new high-speed line (NBS) between Hamburg and Hanover has received the approval of the government, and will go up for a Bundestag vote shortly. The line has been proposed and planned in various forms since the 1990s, the older Y-Trasse plan including a branch to Bremen in a Y formation, but the current project omits Bremen. The idea of building this line is good and long overdue, but unfortunately everything about it, including the cost, the desired speed, and the main public concerns, betray incompetence, of the kind that gave up on building any infrastructure and is entirely reactive, much like in the United States.

The route, in some of the flattest land in Germany, is a largely straight new high-speed rail line. Going north from Hanover to Hamburg, it departs somewhat south of Celle, and rejoins the line just outside Hamburg’s city limits in Meckelfeld. The route appears to be 107 km of new mainline route, not including other connections adding a few kilometers, chiefly from Celle to the north. An interactive map can be found here; the map below is static, from Wikipedia, and the selected route is the pink one.

For about 110 km in easy topography, the projected cost is 6.7 billion € per a presentation from two weeks ago, which is about twice as high as the average cost of tunnel-free German NBSes so far. It is nearly as high as the cost of the Stuttgart-Ulm NBS, which is 51% in tunnel.

And despite the very high cost, the standards are rather low. The top speed is intended to be 250 km/h, not 300 km/h. The travel time savings is only 20 minutes: trip times are to be reduced from 79 minutes today to 59 minutes. Using a top speed of 250 km/h, the current capabilities of ICE 3/Velaro trains, and the existing top speeds of the approaches to Hamburg and Hanover, I’ve found that the nonstop trip time should be 46 minutes, which means the planned timetable padding is 28%. Timetable padding in Germany is so extensive that trains today could do Hamburg-Hanover in 63 minutes.

As a result, the project isn’t really sold as a Hamburg-Hanover high-speed line. Instead, the presentation above speaks of great trip time benefits to the intermediate towns with local stops, Soltau (population: 22,000) and Bergen (population: 17,000). More importantly, it talks about capacity, as the Hamburg-Hanover line is one of the busiest in Germany.

As a capacity reliever, a high-speed line is a sound decision, but then why is it scheduled with such lax timetabling? It’s not about fitting into a Takt with hourly trip times, first of all because if the top speed were 300 km/h and the padding were the 7% of Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Sweden then the trip time would be 45 minutes, and second of all because Hamburg is at the extremity of the country and therefore it’s not meaningfully an intercity knot that must be reached on the hour.

Worse, the line is built with the possibility of freight service. Normal service is designed to be passenger-only, but in case of disruptions on the classical line, the line is designed to be freight-ready. This is stupid: it’s much cheaper to invest in reliability than to build a dual-use high-speed passenger and freight line, and the one country in the world with both a solid high-speed rail network and high freight rail usage, China, doesn’t do this. (Italy builds its high-speed lines with freight-friendly standards and has high construction costs, even though its construction costs in general, e.g. for metro lines or electrification, are rather low.)

Cross-Border Rail and the EU’s Learned Helplessness

I’m sitting on a EuroCity train from Copenhagen back to Germany. It’s timetabled to take 4:45 to do 520 km, an average speed of 110 km/h, and the train departed 25 minutes late because the crew needed to arrive on another train and that train was late. One of the cars on this train is closed due to an air conditioner malfunction; Cid and I rode this same line to Copenhagen two years ago and this also happened in one direction then.

This is a line that touches, at both ends, two of the fastest conventional lines in Europe, Stockholm-Malmö taking 4:30 to do 614 km (136 km/h) and Berlin-Hamburg normally taking 1:45 to do 287 km (164 km/h) when it is on time. This contrast between good lines within European member states, despite real problems with the German and Swedish rail networks, and much worse ones between them, got me thinking about cross-border rail more. Now, this line in particular is getting upgraded – the route is about to be cut off when the Fehmarn Belt Line opens in four years, reducing the trip time to 2:30. But more in general, cross-border and near-border lines that slow down travel that’s otherwise decent on the core within-state city pairs are common, and so far there’s no EU action on this. Instead, EU action on cross-border rail shows learned helplessness of avoiding the only solution for rail construction: top-down state-directed infrastructure building.

The upshot is that there is good cross-border rail advocacy here, most notably by Jon Worth, but because EU integration on this matter is unthinkable, this advocacy is forced to treat the railroads as if they are private oligopolies rather than state-owned public services. Jon successfully pushed for the incoming EU Commission of last year to include passenger rights in its agenda, to deal with friction between different national railroads. The issue is that SNCF and DB have internal ways of handling passenger rights in case of delays, due to domestic pressure on the state not to let the state railroad exploit its users, and they are not compatible across borders: SNCF is on time enough not to strand passengers, DB has enough frequency and extreme late-night timetable padding (my connecting train to Berlin is padded from 1:45 to 2:30, getting me home well past midnight) not to strand passengers; but when passengers cross from Germany to France, these two internal methods both fail.

At no point in this discussion was any top-down EU-level coordination even on the table. The mentality is that construction of new lines doesn’t matter – it’s a megaproject and these only generate headaches and cost overruns, not results, so instead everything boils down to private companies competing on the same lines. That the companies are state-owned is immaterial at the EU level – SNCF has no social mission outside the borders of France and therefore in its international service it usually behaves as a predatory monopoly profiteering off of a deliberately throttled Eurostar/Thalys market.

If there’s no EU state action, then the relationship between the operator, which is not part of the state, and the passenger, is necessarily adversarial. This is where the preference for regulations that assume this relationship must be adversarial and aim to empower the individual consumer comes from. It’s logical, if one assumes that there will never be an EU-wide high-speed intercity rail network, just a bunch of national networks with one-off cross-border megaprojects compromised to the point of not running particularly quickly or frequently.

And that is, frankly, learned helplessness on the part of the EU institutions. They take it for granted that state-led development is impossible at higher level than member states, and try to cope by optimizing for a union of member states whose infrastructure systems don’t quite cohere. Meanwhile, at the other end of the Eurasian continent, a continental-scale state has built a high-speed rail network that at this point has higher ridership per capita than most European states and is not far behind France or Germany, designed around a single state-owned network optimized for very high average speeds.

This occurs at a time when support for the EU is high in the remaining member states. There’s broad understanding that scale is a core benefit of the union, hence the regulatory harmonization ensuring that products can be shipped union-wide without cross-border friction. But for personal travel by train, these principles go away, and friction is assumed to only comprise the least important elements, because the EU institutions have decided that solving the most important ones, that is speed and frequency, is unthinkable.

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 Station Design is Incompetent

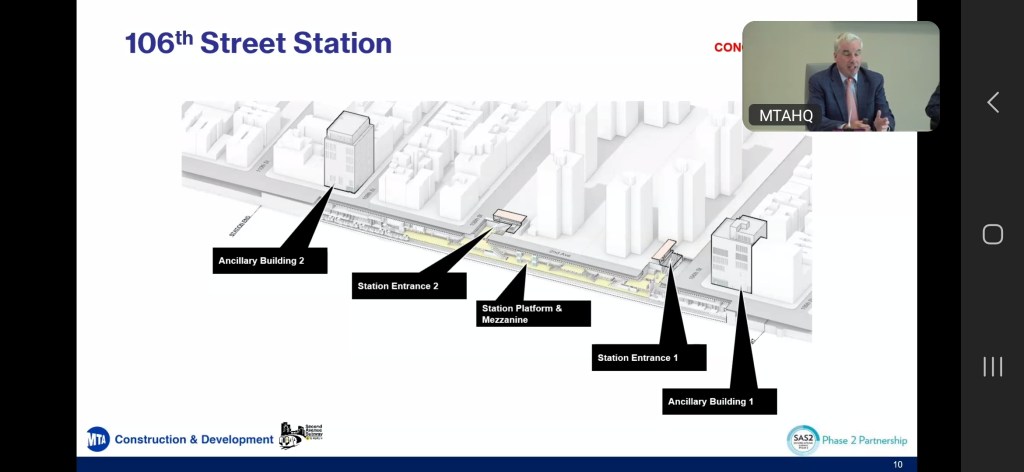

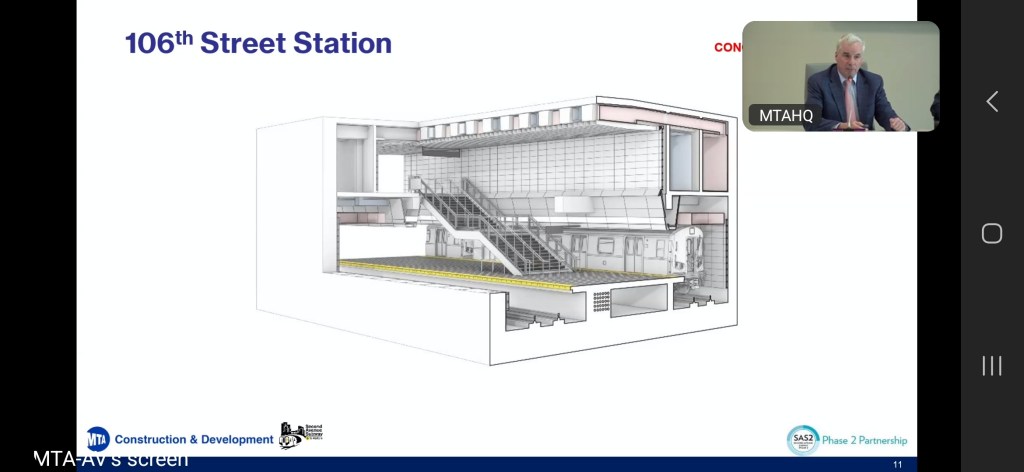

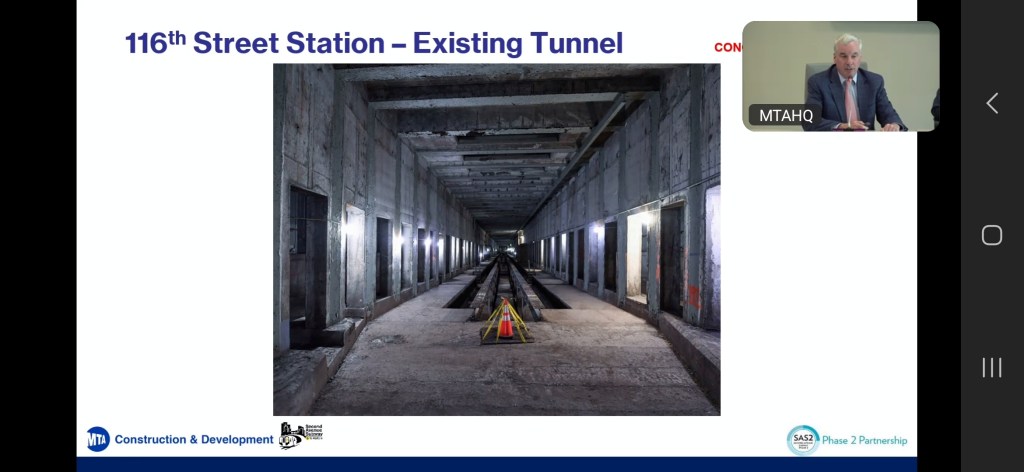

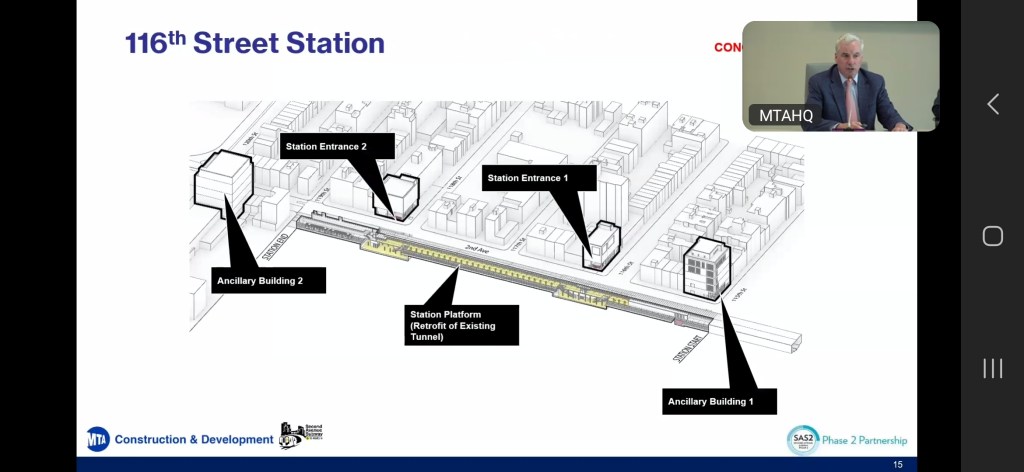

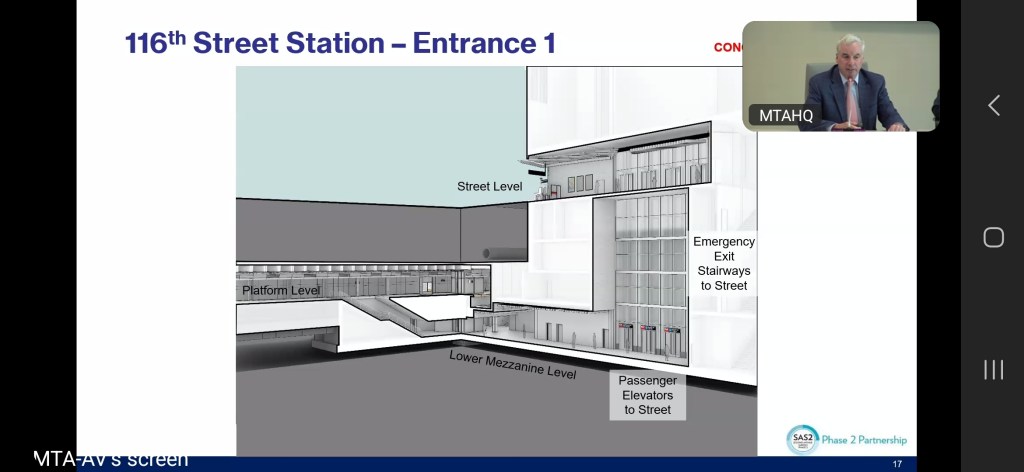

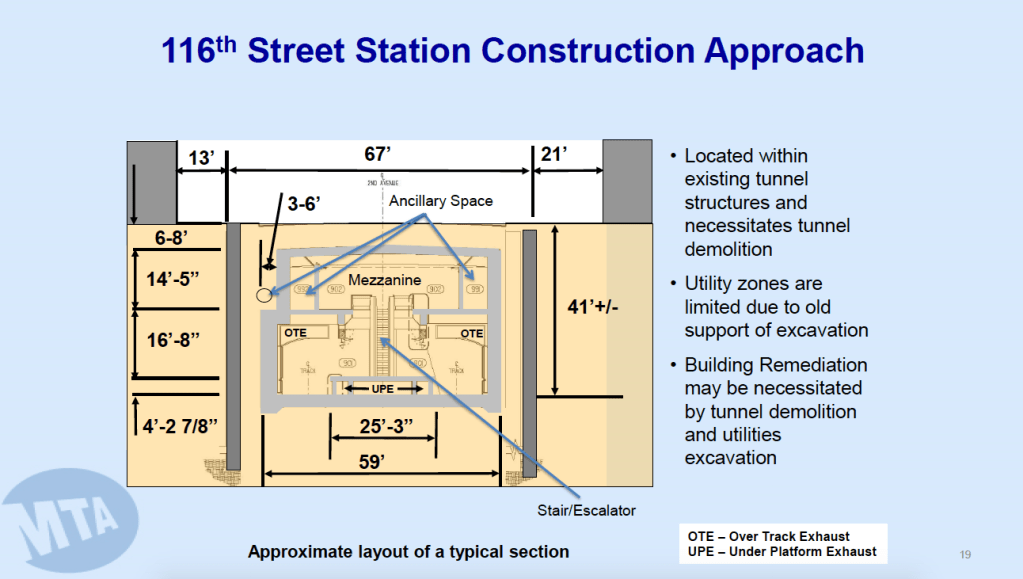

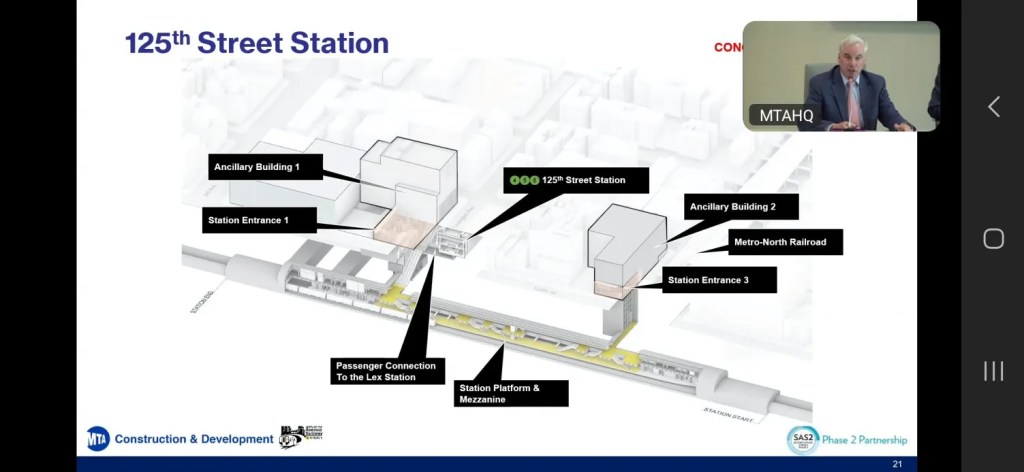

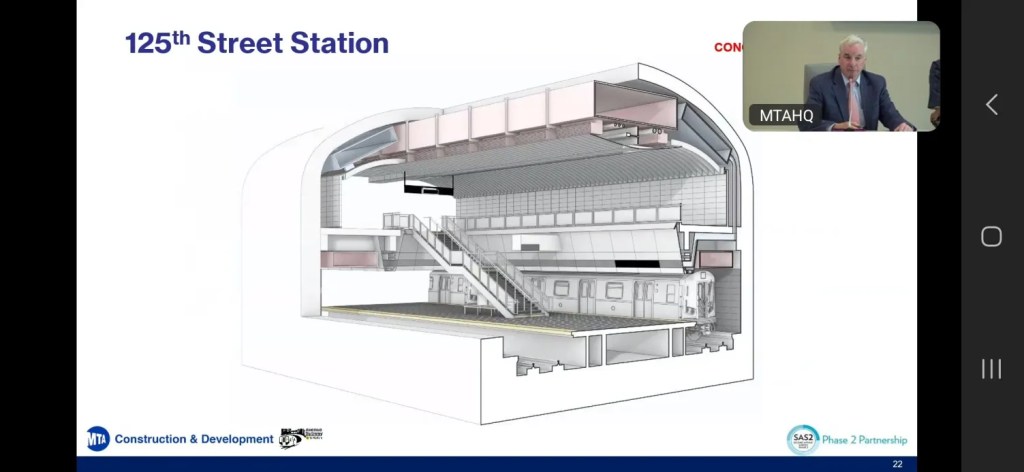

A few hours ago, the MTA presented on the latest of Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. The presentation includes information about the engineering and construction of the three stations – 106th, 116th, and 125th Streets. The new designs are not good, and the design of 116th in particular betrays severe incompetence about how modern subway stations are built: the station is fairly shallow, but has a mezzanine under the tracks, with all access to or from the station requiring elevator-only access to the mezzanine.

What was in the presentation?

Here is a selection of slides, describing station construction. 106th Street is to be built cut-and-cover; 116th is to use preexisting construction but avoid cut-and-cover to reach them from the top and instead mine access from the bottom; 125th is to be built deep-level, with 125′ deep (38 m) platforms, underneath its namesake street between Lexington and Park Avenues.

The problems with 116th Street

Elevator-only access

Elevator-only access is usually stupid. It’s especially stupid when it’s at a shallow station; as the page 19 slide above shows, the platforms are about 11.5 meters below ground, which is an easy depth for both stair and escalator access.

Now, to be clear, there are elevator-only stations built in countries with reasonable subway construction programs. Sofia on Nya Tunnelbanan is elevator-only, because it is 100 meters below street level, due to the difficult topography of Södermalm and Central Stockholm, in which Sofia, 26 meters above sea level, is right next to Riddarfjärden, 23 meters deep. Emergency access is provided via ramps to the sea-level freeway hugging the north shore of Södermalm, used to construct the mined cavern in the first place. Likewise, the Barcelona L9 construction program, by far the most expensive in Spain and yet far cheaper than in any recent English-speaking country, has elevator-only access to the deep stations, in order to avoid any construction outside a horizontal or vertical tunnel boring machine.

The depth excuse does not exist in East Harlem. 11.5 meters is not an elevator-only access depth. It’s a stair access depth with elevators for wheelchair accessibility. Stairs are planned to be provided only for emergency access, without public usage. Under NFPA 130 the stairs are going to have to have enough capacity for full trains, much more than is going to be required in ordinary service, and they’d lead passengers to the same street as the elevators, nothing like the freeway egress of Sofia.

Below-platform mezzanines

To avoid any shallow construction, the mezzanines will be built below the platforms and not above them. As a result, access to the station means going down a level and then going back up to the platform level. In effect, the station is going to behave as a rather deep station as far as passenger access time to the platforms is concerned: the planned depth is 57′, or 17.4 meters, which means that the total vertical change from street level is around 23.5 meters, twice the actual depth of the platforms.

Dig volume

Even with the reuse of existing infrastructure, the station is planned to have too much space north and south of the platforms, as seen with the locations of the ancillary buildings.

I think that this is due to designs from the 2000s, when the plan was to build all stations with extensive back-of-the-house space on both sides of the platform. Phase 1 was built this way, as we cover in our New York case, and after we yelled at the MTA about it, it eventually shrank the footprint of the stations. 116th’s station start and end are four blocks apart, a total of about 300 meters, comparable to 86th Street; the platform is 186 m wide and the station overall has no reason to be longer than 190-200. But it’s possible the locations of the ancillary buildings were fixed from before the change, in which case the incompetence is not of the current leadership but of previous leadership.

Why?

On Bluesky, I’m seeing multiple activists I think well of assume that this is because the MTA is under pressure to either cut costs or avoid adverse community impact. Neither of these explanations makes much sense in context. 106th Street is planned to be built cut-and-cover, in the same neighborhood as 116th, with the same street width, which rules out the community opposition explanation. Cut-and-cover is cheaper than alternatives, which also rules out the cost explanation.

Rather, what’s going on is that MTA leadership does not know how a modern cut-and-cover subway station looks like. American construction prefers to avoid cut-and-cover even for stations, and over time such stations have been laden with things that American transit managers think are must-haves (like those back-of-the-house spaces) and that competent transit managers know they don’t need to build. They may want to build cut-and-cover, as at 106th, but as soon as there’s a snag, they revert to form and look for alternatives. They complain about utility relocation costs, which are clearly not blocking this method at 106th, and which did not prevent Phase 1’s 96th Street from costing about 2/3 as much as 86th and 72nd per cubic meter dug.

Under pressure to cut costs and shrink the station footprint, the MTA panicked and came up with the best solution the political appointees, that is to say Janno Lieber and Jamie Torres-Springer and their staff, and the permanent staff that they deign to listen to, could do. Unfortunately for New York, their best is not good enough. They don’t know how to build good stations – there are no longer any standardized designs for this that they trust, and the people who know how to do this speak English with an accent and don’t earn enough to command the respect of people on a senior American political appointee’s salary. So they improvise under pressure, and their instincts, both at doing things themselves and at supervising consultants, are not good. To Londoners, Andy Byford is a workhorse senior civil servant, with many like him, and the same is true in other large European cities with large subway systems. But to Americans, the such a civil servant is a unicorn to the point that people came to call him Train Daddy, because this is what he’s being compared with.

S-Bahn and RER Ridership is Urban

People in my comments and on social media are taking it for granted that investments into modernizing commuter rail predominantly benefit the suburbs. Against that, I’d like to point out how on the modern commuter rail systems I know best – the RER and the Berlin S-Bahn – ridership is predominantly urban. Whereas the typical American commuter rail use case is a suburban resident commuting to a central business district job at rush hour, the typical use case on the commuter trains here is an urban resident going to work or a social outing in or near city center. Suburban ridership is strong by American standards, benefiting from being able to piggyback on the high frequency and levels of physical investment produced by the urban ridership.

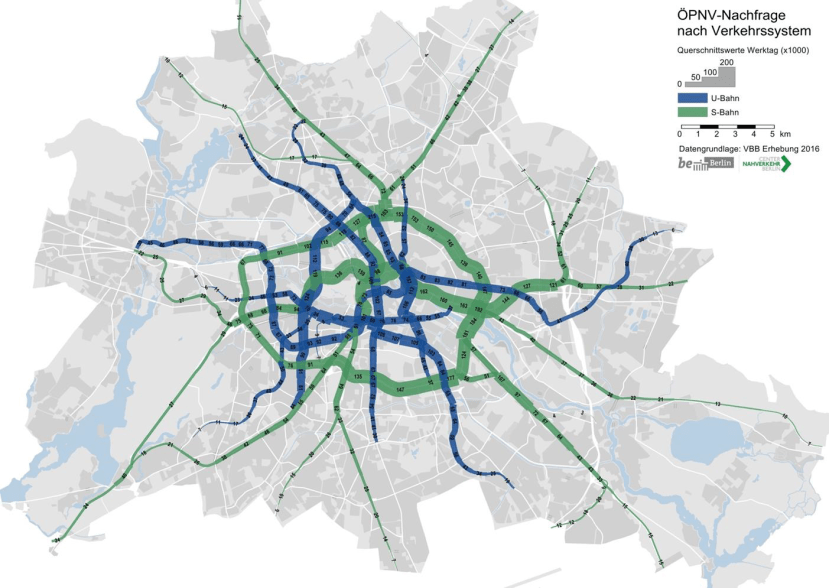

Here’s Berlin’s passenger traffic density on the U- and S-Bahn, as of 2016 (source, p. 6):

The busiest section of the S-Bahn is the Stadtbahn from Ostkreuz to Hauptbahnhof, with about 160,000 passengers per weekday through each interstation. The eastern sections of both the north and the south arms of the Ringbahn are close, with about 150,000 each, and the North-South Tunnel has 100,000. These traffic density levels extend into outer urban neighborhoods outside the ring – ridership on the Stadtbahn trunk remains high well into Lichtenberg – but by the time the trains cross city limits, ridership is rather low. All tails crossing city limits combined have 150,000 riders/day, so a little more than a quarter of the ridership density on the city center segments. Of those tails, the busiest, with a traffic density of 24,000/day, is to Potsdam, which is a suburb but is an independent job center rather than a pure commuter suburb like the rest of the towns in Brandenburg adjacent to Berlin.

I don’t have similar graphics for Paris, only a table of ridership on the SNCF-RER and Transilien by station and time of day and a separate table with annual ridership on the RATP-RER and Métro. But the results there are similar. Total boardings on the RATP-RER in 2019 was 399 million, of which 52 million originated in stations in the Grande Couronne, 186 million in the Petite Couronne, and 161 million in the city. If we double the Grande Couronne boardings, to account for the fact that just about all of those riders are going to the city or a Petite Couronne job center like La Défense, then we get just over a quarter of overall ridership, a similar result to the traffic density of Berlin. On the SNCF-RER, the share of the Grande Couronne is higher, around half.

The city stations include job centers and transfer points from mainline rail and the Métro – there aren’t 47 million people a year whose residential origin station is Gare du Nord – so it’s best to view the system as one used predominantly by Petite Couronne residents, with a handful using it as I did internally to the city and another handful commuting in from the Grand Couronne. This is technically suburban, but the Petite Couronne is best viewed as a ring of city neighborhoods that are not annexed to the city for sociopolitical reasons; the least dense of its three departments, Val-de-Marne, is denser than the densest German city, Munich.

The difference in this pattern with the United States is not hard to explain. Here and in Paris, commuter rail charges the same fares as the subway, runs every 5-10 minutes in urban neighborhoods (even less on the city center trunks), and makes stops at the rate of an express subway line. Of course urban residents use the trains, and we greatly outnumber suburbanites among people traveling to city center. It’s the United States that’s weird, with its suburb-only rail system stuck in the Mad Men era trying to stick with its market of Don Drapers and Pete Campbells.

Quick Note: RER and S-Bahn Line Length

An email correspondent asks me about whether cities should build subway or commuter rail lines, and Adirondacker in comments frequently compares the express lines in New York to the RER. So to showcase the difference, here are some lines with their lengths. The length is measured one-tailed, from a chosen central point.

| Line | Central point | Length (km) |

| RER A to MLV | Les Halles | 37 |

| RER A to Cergy | Les Halles | 40.5 |

| RER B to CDG | Les Halles | 31 |

| RER B to Saint-Rémy | Les Halles | 32.5 |

| RER D to Malesherbes | Les Halles | 79 |

| Crossrail to Shenfield | Farringdon | 34 |

| Crossrail to Reading | Farringdon | 62.5 |

| Thameslink to Brighton | Farringdon | 81 |

| Thameslink to Bedford | Farringdon | 82 |

Express subway lines in New York never go that far; the A train, the longest in the system, is 50 km two-tailed, and not much more than 30 km one-tailed to Far Rockaway. The Berlin S-Bahn is about comparable, in a metro area one quarter the size.

The Danbury Branch and Rail Modernization

I’ve been asked to talk about how rail modernization programs, like the high-speed rail plan we published at Marron this month, affect the Danbury Branch of the New Haven Line. The proposal barely talks about branch modernization beyond saying that the branches should be electrified; we didn’t have time to write precise branch timetables, which means that the timetable I’m going to post here is going to have more rounding artifacts. The good news is that modernization can be done cheaply, piggybacking on required work on the main of the New Haven Line.

Current conditions

The Danbury Branch is a 38 km single-track unelectrified line, connecting South Norwalk with Danbury making six additional intermediate stops. All stations have high platforms, but they are short, ranging between three and six cars.

Ridership is essentially unidirectional: toward Norwalk and New York in the morning, back north in the afternoon. There is little job concentration near the stations. Within 1 km of Danbury there are only 5,000 jobs per OnTheMap, rising to 10,000 if we include Danbury Hospital, which is barely outside the station’s 1 km radius (but is not easily walkable from it). Merritt 7 is in an office park, but there are only 6,000 jobs there, and nearly everyone drives. The other stations are parking lots, and Bethel is somewhat outside the town center for better parking.

The right-of-way is very curvy, much more so than the main line. Where most of the New Haven Line is built to a standard of 2° curves (radius 873 m), permitting 157 km/h with modern cant and cant deficiency, the Danbury Branch scarcely has a section straight enough with gentler curves than 3°, and much of it has such frequent 4° curves that trains cannot go faster than 100 km/h except for speedups of a few seconds at a time to recover delays.

A first pass on infrastructure and operations

It is effectively free to electrify a 38 km single-track line. The high-speed rail report estimates it at $75 million based on both European electrification costs (see report for sources) and the Southern Transcon proposal, which is $2 million/km on a busy double-track line. The junction between the branch and the main line is flat, but outbound trains can be timetabled to avoid conflict, and inbound trains have no at-grade conflict to begin with. If platform lengthening is desired, then it is a noticeable extra expense; figure $30 million for each eight-car platform, or perhaps half that on single track (but then some stops are double-track), maybe with some pro-rating for existing platforms if they can be easily reused.

The tracks should also be maintained to higher speed, which is a routine application of a track laying machine, with some weekend closures for construction followed by what should be an uninterrupted multidecade period of operations. The curves are already superelevated to a maximum of 5-6″; this is less than the 7″ maximum in US law (180 mm here), but the difference is not massive. The line has a 50 mph speed limit today for the most part, whereas it can be boosted to about 100-110 km/h depending on section, a smaller difference than taking the main line’s 70 mph and turning it into 150-160 km/h.

With a blanket speed limit of 110 km/h – in truth some sections need to dip down to 100 or even less whereas the Bethel-Danbury and Merritt 7-Wilton interstations can be done mostly at 130 – the trip time between South Norwalk and Danbury is, inclusive of 7% pad, 28.75 minutes. The Northeast Corridor report timetables have express New Haven Line commuter trains arriving South Norwalk southbound at :15.25 every 20 minutes and departing northbound at :14.75, so they’d be departing Danbury at :46.5 and arriving :43.5. Meets would occur at the :20, :30, and :40 points.

The :30 point, important as it is a meet even if service is reduced to every 30 minutes, is just south of Branchville, likely too far to use the existing meet at the station. Thus, at first pass, some additional double-tracking is needed, a total of 6 km if it covers the entire Cannondale-Branchville interstation, which would cost around $50 million at MBTA Franklin Line costs. MBTA Franklin Line costs are likely an underestimate, since the terrain on the Cannondale-Branchville interstation is hillier and some additional earthworks would be required on part of the section. A high-end estimate should be the cost of a high-speed rail line without elevated or tunneled segments, around $30 million/km or even less (cut-and-fill isn’t needed as much when the line curves with the topography), say $150 million.

The :20 point southbound is at or just south of Bethel. While this is in a built-up area, the right-of-way looks wide enough for two tracks and the topography is easier; if the station is the meet, then the cost is effectively zero, bundled into a platform lengthening project. Potentially, this could even be further bundled with moving the station slightly south to be closer to the town center. The :40 point southbound is at Merritt 7, which has room for a second track but not necessarily for a platform at it, and could instead get a second track on the opposite side of the platform if there’s enough of a rebuild to turn it into an island with additional vertical circulation; the cost of the second track itself would be a rounding error but the cost of station reconstruction would not be and would likely be in the mid-tens of millions.

How this fits into the broader system

The timetable in the report already assumes that New Haven Line service comprises 6 peak trains per hour (tph) that use the branches. The default assumption, reproduced in the service network graphic, is that New Canaan and Danbury get 3 tph each, and New Canaan gets a grade-separated junction but Danbury does not. Those trains all go to Grand Central with no through-running: only the local trains on the New Haven Line get to run through, since local trains are the highest priority for through-running. If a tunnel connecting the Gateway tunnel with Grand Central is opened, as in some long-term plans (here’s ETA’s, which isn’t very different from past blog posts’), then they can run through to it.

The establishment of this service is not going to, by itself, change the characteristic of ridership on the line. Electrification, better timetabling, and better rolling stock (in this order) can reduce the trip time from an hour today to 29 minutes, and the trip time to Grand Central from about 2:25 to 1:09, but the main effect would be to greatly improve the connectivity of existing users, who’d be driving to the parking lot stations more often, perhaps working from the office more and from home less, or taking the train to social events in the city. Some would opt to use the train to get to work at Stamford, as a secondary market. Over time, I expect that people would buy in the area to commute to work in New York (or at Stamford), but housing permit rates in Fairfield County are low and only limited TOD is likely. It would take concerted commercial TOD at the stations to produce reverse-peak ridership, likely starting with expanding the Merritt 7 office park and making it a bit less auto-oriented.

If the ridership isn’t there, then a train every 20 minutes is not warranted and only a train every 30 minutes should be provided. This reduces the double-track infrastructure requirement but only marginally, as the meets that are no longer needed are the easy ones and the one that still is is the hard one to build, south of Branchville. In effect, something like 80% of the cost provides two thirds of the capacity; this is common to rail projects, in that small cuts in an already optimized budget lead to much larger cuts in benefits, the opposite of what one hopes to achieve when optimizing cuts.

The Northeast Corridor Report is Out

Here is the link. If people have questions, please post them in comments and I’ll address; see also Bluesky thread (and Mastodon but there are no questions there yet).

Especial thanks go to everyone who helped with it – most of all Devin Wilkins for the tools, analysis, and coding work that produced the timetables, which, as the scheduling section says, are the final product as perceived by the passenger. Other than Devin, the other members of the TCP/TLU program at Marron gave invaluable feedback, and Elif has done extensive work with both typesetting and managing the still under-construction graphical narrative we’re about to do (expected delivery: mid-June). Members of ETA have looked over as well, and Madison and Khyber nitpicked the overhead electrification section in infrastructure investment until it was good. And finally, Cid was always helpful, whether with personal support, or with looking over the overview as a layperson.

Against State of Good Repair

We’re releasing our high-speed rail report later this week. It’s a technical report rather than a historical or institutional one, so I’d like to talk about a point that is mentioned in the introduction explaining why we think it’s possible to build high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor for $17 billion: the current investment program, Connect 2037, centers renewal and maintenance more than expansion, under the moniker State of Good Repair (SOGR). In essence, megaprojects have a set of well-understood problems of high costs and deficient outcomes, behind-the-scenes maintenance has a different set of problems, and SOGR combines the worst of both worlds and the benefits of neither. I’ve talked about this before in other contexts – about Connecticut rail renewal costs, or leakage in megaproject budgeting, or the history of SOGR on the New York City Subway, or Northeast Corridor catenary. Here I’d like to synthesize this into a single critique.

What is SOGR?

SOGR is a long-term capital investment to bring all capital assets into their expected lifespan and maintenance status. If a piece of equipment is supposed to be replaced every 40 years and is currently over 40, it’s not in good repair. If the mean distance between failures falls below a certain prescribed level, it’s not in good repair. If maintenance intervals grow beyond prescription, then the asset to be maintained is not in good repair. In practice, the lifespans are somewhat conservative so in practice a lot of things fall out of good repair and the system keeps running. The upshot is that because the maintenance standards are somewhat flexible, it’s easy to defer maintenance to make the system look financially healthier, or to deal with an unexpected budget shortfall.

Modern American SOGR goes back to the New York subway renewal programs of the 1980s and 90s, which worked well. The problem is that, just as the success of one infrastructure expansion tempts the construction of other, less socially profitable ones, the success of SOGR tempted agencies to justify large capital expenses on SOGR grounds. In effect, what should have been a one-time program to recover from the 1970s was generalized as a way of doing maintenance and renewal to react to the availability of money.

Megaprojects and non-megaprojects

In practice, what defines a megaproject is relative – a 6 km light rail extension is a megaproject in Boston but not in Paris – and this also means that they are not easy to locally benchmark, or else there would be many like them and they would be more routine. This means that megaprojects are, by definition, unusual. Their outcome is visible, and this attracts high-profile politicians and civil servants looking to make their mark. Conversely, their budgeting is less visible, because what must be included is not always clear. This leads to problems of bloat (this is the leakage problem), politicization, surplus extraction, and plain lying by proponents.

Non-megaprojects have, in effect, the opposite set of problems. Their individual components can be benchmarked easily, because they happen routinely. A short Paris Métro extension, a few new infill stations, and a weekend service change for track renewal in New York are all examples of non-megaprojects. These are done at the purely professional level, and if politicians or top managers intervene, it’s usually at the most general level, for example the institution of Fastrack as a general way of doing subway maintenance, and that too can be benchmarked internally. In this case, none of the usual problems of megaprojects is likely. Instead, problems occur because, while the budgeting can be visible to the agency, the project itself is not visible to the general public. If an entire new subway line’s construction fails and the line does not open, this is publicly visible, to the embarrassment of the politicians and agency heads who intended to take credit for it. In contrast, if a weekend service change has lower productivity than usual, the public won’t know until this problem has metastasized in general, by which point the agency has probably lost the ability to do this efficiently.

And to be clear, just as megaprojects like new subway lines vary widely in their ability to build efficiently, so do non-megaproject capital investments vary, if anything even more. The example I gave writing about Connecticut’s ill-conceived SOGR program, repeated in the high-speed rail report, is that per track- or route-km the state spends in one year about 60% as much as what Germany spends on a once per generation renewal program, to be undertaken about every 35 years. Annually, the difference is a factor of about 20. New York subway maintenance has degraded internally over time, due to ever tighter flagging rules, designed for worker protection, except that worker injuries rose from 1999 to the 2010s.

The Transit Costs Project

The goal of the Transit Costs Project is to use international benchmarking to allow cities to benefit from the best of both worlds. Megaprojects benefit from public visibility and from the inherent embarrassment to a politician or even a city or state that can’t build them: “New York can’t expand the subway” is a common mockery in American good-government spaces, and people in Germany mock both Bavaria for the high costs and long timeline of the second Munich S-Bahn tunnel and Berlin for, while its costs are rather normal, not building anything, not even the much-promised tram alternatives to the U-Bahn. Conversely, politicians do get political capital from the successful completion of a megaproject, encouraging their construction, even when not socially profitable.

Where we come in is using global benchmarking to remove the question marks from such projects. A subway extension may be a once in a generation effort in an American city, but globally it is not, and therefore, we look into how as much of the entire world as we can see into does this, to establish norms. This includes station designs to avoid overbuilding, project delivery and procurement strategies, system standards, and other aspects. Not even New York is as special as it thinks it is.

To some extent, this combination of the best features of both megaprojects and non-megaprojects exists in cities with low construction costs. This is not as tautological as it sounds. Rather, I claim that when construction costs are low, even visible extensions to the system fall below the threshold of a megaproject, and thus incremental metro extensions are built by professionals, with more public visibility providing a layer of transparency than for a renewal project. This way, growth can sustain itself until the city runs out of good places to build or until an economic crisis like the Great Recession in Spain makes nearly all capital work stop. In this environment, politicians grow to trust that if they want something big built, they can just give more money to more of the same, serving many neighborhoods at once.

In places with higher costs, or in places that are small enough that even with low costs it’s rare to build new metro lines, this is not available. This requires the global benchmarking that we use; occasionally, national benchmarking could work, in a country with medium costs and low willingness to build (for example, Germany), but this isn’t common.

The SOGR problem

If what we aim to do with the Transit Costs Project is to combine the positive features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects, SOGR does the exact opposite. It is conceived as a single large program, acting as the centerpiece of a capital plan that can go into the tens of billions of dollars, and is therefore a megaproject. But then there’s no visible, actionable, tangible promise there. There is no concrete promise of higher speed or capacity. To the extent some programs do have such a promise, they are subsumed into something much bigger, which means that failing to meet standards on (say) elevator reliability can be excused if other things are said to go into a state of good repair, whatever that means to the general public.

Thus, SOGR invites levels of bloat going well beyond those of normal expansion megaprojects. Any project can be added to the SOGR list, with little oversight – it isn’t and can’t be locally benchmarked so there is no mid-career professional who can push back, and conversely it isn’t so visible to the general public that a general manager or politician can push back demanding a fixed opening deadline. For the same reason, inefficiency can fester, because nobody at either the middle or upper level has the clear ability to demand better.

Worse, once the mentality of SOGR is accepted, more capital projects, on either the renewal side or the expansion side, are tied to it, reducing their efficiency. For example, the catenary on the Northeast Corridor south of New York requires an upgrade from fixed termination/variable tension to auto-tension/constant tension. But Amtrak has undermaintained the catenary expecting money for upgrades any decade now, and now Amtrak claims that the entire system must be replaced, not just the catenary but also the poles and substations. The language used, “the system is falling apart” and “the system is maintained with duct tape,” invites urgency, and not the question, “if you didn’t maintain this all this time, why should we trust you on anything?”. With the skepticism of the latter question, we can see that the substations are a separate issue from the catenary, and ask whether the poles can be rebuilt in place to reduce disruption, to which the vendors I’ve spoken with suggested the answer is yes using bracing.

The Connecticut track renewal program falls into the same trap. With no tangible promise of better service, the state’s rail lines are under constant closures for maintenance, which is done at exceptionally low productivity – manually usually, and when they finally obtained a track laying machine recently they’ve used it at one tenth its expected productivity. Once this is accepted as the normal way of doing things, when someone from the outside suggests they could do better, like Ned Lamont with his 30-30-30 proposal, the response is to make up excuses why it’s not possible. Why disturb the racket?

The way forward

The only way forward is to completely eliminate SOGR from one’s lexicon. Big capital programs must exclusively fund expansion, and project managers must learn to look with suspicion on any attempt to let maintenance projects piggyback on them.

Instead, maintenance and renewal should be budgeted separately from each other and separately from expansion. Maintenance should be budgeted on the same ongoing basis as operations. If it’s too expensive, this is evidence that it’s not efficient enough and should be mechanized better; on a modern railroad in a developed country, there is no need to have maintenance of way workers walk the tracks instead of riding a track inspection train or a track laying machine. With mechanized maintenance, inventory management is also simplified, in the sense that an entire section of track has consistent maintenance history, rather than each sleeper having been installed in a different year replacing a defective one.

Renewal can be funded on a one-time basis since the exact interval can be fudged somewhat and the works can be timed based on other work or even a recession requiring economic stimulus. But this must be held separate from expansion, again to avoid the Connecticut problem of putting the entire rail network under constant maintenance because slow zones are accepted as a fact of life.

The importance of splitting these off is that it makes it easier to say “no” to bad expansion projects masquerading as urgent maintenance. No, it’s not urgent to replace a bridge if the cost of doing so is $1 billion to cross a 100 meter wide river. No, the substations are a separate system from the overhead catenary and you shouldn’t bundle them into one project.

With SOGR stripped off, it’s possible to achieve the Transit Costs Project goal of combining the best rather than the worst features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects. High-speed rail is visible and has long been a common ask on the Northeast Corridor, and with the components split off, it’s possible to look into each and benchmark to what it should include and how it should be built. Just as New York is not special when it comes to subways, the United States is not special when it comes to intercity rail, it just lags in planning coordination and technology. With everything done transparently based on best practices, it is indeed possible to build this on an expansion budget of about $17 billion and a rounding-error track laying machine budget.

The Problems of not Killing Penn Expansion and of Tariffs

Penn Station Expansion is a useless project. This is not news; the idea was suspicious from the start, and since then we’ve done layers of simulation, most recently of train-platform-mezzanine passenger flow. However, what is news is that the Trump administration is aiming to take over Penn Reconstruction (a separate, also bad project) from the MTA, in what looks like the usual agency turf battles, except now given a partisan spin. I doubt there’s going to be any money for Reconstruction (budgeted at $7 billion), let alone expansion (budgeted at $17 billion), and overall this looks like the usual promises that nobody intends to act upon. The problem is that this project is still lurking in the background, waiting for someone insane enough to say what not a lot of people think but few are willing to openly disagree with and find some new source of money to redirect there. And oddly, this makes me think of tariffs.

The commonality is that free trade is not just good, but is more or less an unmixed blessing. In public transport rolling stock procurement, the costs of tariffs are so high that a single job created in the 2010s cost $1 million over 4-6 years, paying $20/hour. In infrastructure, in theory most costs are local and so it shouldn’t matter, but in practice some materials need to be imported, and when they run into trade barriers, they mess entire construction schedules. Boston’s ability to upgrade commuter rail stations with high platform was completely lost due to successive tightening of the Buy America waiver process under Trump and then Biden, to the point that even materials that were just not made in America (steel, FRP) could not be imported. The problem is that nobody was willing to say this out loud, and instead politicians chose to interfere with bids to get some photo-ops, getting trains that are overpriced and fail to meet schedule and quality standards.

Thus, the American turn away from free trade, starting with Trump’s 2016 campaign. During the Obama-Trump transition, the FTA stopped processing Buy America waivers, as a kind of preemptive obedience to something that was never written into the law, which includes several grounds for waivers. During the Trump-Biden transition, the standards were tightened, and waivers required the approval of a political office at the White House, which practiced a hostile environment, hence the above example of the MBTA’s platform problems. Now there are general tariffs, at a rate that changes frequently with little justification. The entire saga, especially in the transit industry, is a textbook example not just of comparative advantage, but of the point John Williamson made in the original Washington Consensus that trade barriers were a net negative to the country that imposes them even if there’s no retaliation, purely from the negative effects on transparency and government cleanliness. This occurred even though tariffs were not favored in the political elite of the United States, or even in the general public; but nobody would speak out except special interests and populists who favored trade barriers.

And Penn Expansion looks the same. It’s an Amtrak turf game, which NJ Transit and the MTA are indifferent to. NJ Transit’s investment plan is not bad and focuses on actual track-level improvements on the surface. The MTA has a lot of problems, including the desire for Penn Reconstruction, but Penn Expansion is not among them. The sentiments I’m getting when I talk to people in that milieu is that nobody really thinks it’s going to happen, and as a result most people don’t think it’s important to shoot down what is still a priority for Amtrak managers who don’t know any better.

The problem is that when the explicit argument isn’t made, the political system gets the message that Penn Expansion is not necessarily bad, but now is not the time for it. It will not invest in alternatives. (On tariffs, the alternative is to repeal Buy America.) It will not cancel the ongoing design work, but merely prolong it by demanding more studies, more possibilities for adding new tracks (seven? 12? Any number in between?). It will insist that any bounty of money it gets go toward more incremental work on this project, and not on actually useful alternatives for what to do with $17 billion.

This can go on for a while until some colossally incompetent populist of the type that can get elected mayor or governor in New York, or perhaps president, decides to make it a priority. Then it can happen, and $17 billion plus future escalation would be completely wasted, and further investment in the system would suffer because everyone would plainly see that $17 billion buys next to nothing in New York so what’s the point in spending a mere $300 million here and there on a surface junction? If it were important then Amtrak would have prioritized that, no? Even people who get on some level that the agencies are bad with money will believe them on technical matters like scheduling and cost estimation over outsiders, in the same manner that LIRR riders think the LIRR is incompetent and also has nothing to learn from outsiders.

The way forward is to be more formal about throwing away bad ideas. Does Penn Expansion have any transportation value? No. So cancel it. Drop it from the list of Northeast Corridor projects, cancel all further design work, and spend about 5 orders of magnitude less money on timetabling trains at Penn Station within its existing footprint. Don’t let it lurk in the background until someone stupid enough decides to fund it; New York is rather good lately at finding stupid people and elevating them to positions of power. And learn to make affirmative arguments for this rather than the usual “it will just never happen” handwringing.