Category: Urban Transit

Why Building Metros is Necessary for the Green Transition Away from Cars

There’s controversy in Germany over building U- and S-Bahn extensions, in which environmentalists argue against them on the grounds that people can just take trams and the environmental benefits of urban rail are not high. For example, the Ariadne project prefers push factors (green regulations and taxes) to pull factors (building better alternatives), BUND opposes U- and S-Bahn expansion, and a report endorsed by Green politicians argued based on shoddy analysis leading to retraction that the embodied carbon emissions of tunneling exceeded any savings, which it estimated at only 714 t-CO2 per underground km built. Against this, it’s important to sanity-check car and public transport ridership to arrive at more solid figures.

To start with, virtually everyone travels by car or by public transport. There’s a notable exception for cycling, but cycling is typically done at short ranges, and the metro expansions under discussion here (all outside the Ring) are beyond that range. In Berlin, the modal split for cycling peaks in the 1-3 km range and is small past 10 km. Beyond the scale of a neighborhood or maybe a college town, cars and mass transit are substitutes for each other.

Nor does public transport expansion lead to hypermobility, in which overall trips grow longer as people commute from farther away and car use doesn’t decline or only weakly declines. If anything, the ratio of substitution for passenger-km rather than trips is that a p-km by metro substitutes for more than one p-km by cars, because metro-oriented cities can be denser and allow for shorter commute trips. Berliners average 3.3 4.6-km trips per day, or 15 km/day; Germany-wide, it’s 35.5 km/day (see table 11 of MiD). If anything, the presence of a large city core also shortens the average car trip by reducing exurb-to-exurb driving at low density.

Nor does polycentricity solve the problem. Indeed, ridership in polycentric regions is weaker than in monocentric ones. MiD has data by state and Verkehrsverbund in Germany, with modal splits by trips (all trips, not just work trips) and passenger-km, the latter measure having far less in the way of cycling and walking. From this, we have the following table:

| Geography | Transit % (trips) | Car % (trips) | Transit % (p-km) | Car % (p-km) |

| Berlin | 27 | 24 | 47 | 40 |

| Brandenburg | 9 | 51 | 22 | 71 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 7 | 52 | 14 | 80 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 9 | 48 | 12 | 81 |

| Saxony | 11 | 56 | 16 | 77 |

| Thuringia | 9 | 55 | 16 | 79 |

| Hamburg | 22 | 29 | 43 | 47 |

| Bremen | 14 | 33 | 30 | 60 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 8 | 56 | 14 | 79 |

| Lower Saxony | 8 | 53 | 15 | 77 |

| Nordrhein-Westfalen | 10 | 55 | 18 | 74 |

| Rheinland-Pfalz | 9 | 57 | 19 | 75 |

| Saarland | 10 | 65 | 15 | 79 |

| Hesse | 12 | 52 | 19 | 74 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 9 | 53 | 17 | 75 |

| Bavaria | 10 | 56 | 18 | 75 |

| Munich (city) | 25 | 29 | 39 | 51 |

| Frankfurt (city) | 24 | 29 | 38 | 52 |

| Stuttgart (city) | 23 | 36 | 33 | 60 |

| Munich (MVV) | 19 | 41 | 31 | 61 |

| Hamburg (HVV) | 16 | 33 | 29 | 63 |

| Hanover (Region) | 15 | 42 | 25 | 66 |

| Rhine-Main (RMV) | 13 | 49 | 22 | 71 |

| Rhine-Neckar (VRN) | 10 | 51 | 17 | 75 |

| Rhine-Ruhr (VRR) | 12 | 53 | 20 | 73 |

| Rhine-Sieg (VRS) | 12 | 49 | 22 | 70 |

Berlin is by all measures the most public transport-oriented and least car-oriented part of Germany. The source doesn’t explicitly break out VBB, but VBB comprises Berlin and Brandenburg, whose population ratio is 59:41, so we get a modal split by trips of 20% transit, 35% car; a similar computation for p-km is less certain since Brandenburgers, many of whom commute to Berlin, have longer trip lengths, but it’s likely Berlin and Brandenburg’s combined modal split is slightly better than those of MVV and HVV, both monocentric. Brandenburg, notably, has the highest modal split by p-km outside the city-states, owing to the Berlin commuters.

In contrast, the polycentric regions – Rhine-Neckar (Mannheim), Rhine-Ruhr (excluding Cologne), Rhine-Sieg (Cologne-Bonn), and to a large extent also Rhine-Main (Frankfurt) – all have weak modal splits. The cities themselves have healthy usage of public transport, judging by the data that’s available and by ridership on their Stadtbahn systems, but most of the Rhine-Ruhr’s population doesn’t live in Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Essen, Dortmund, or Wuppertal, and this population drives.

The upshot is that rail development that strengthens city center at the expense of suburban job clusters should be considered a positive development for transitioning from cars to public transport. Job clusters outside city center do not reduce commuting, but instead make commuting more auto-oriented.

This, in turn, creates serious estimation problems for the diversion rate, which is why environmental benefit-cost analyses underrate the effect of urban rail construction. An expansion of a north-south line like U8 would not just increase the residential connectivity of Märkisches Viertel but also, on the margins, increase the commercial connectivity of Alexanderplatz and other central stations served by the line. This, in turn, should induce additional ridership on lines nowhere near Märkisches Viertel, for example, east-west lines like U5 and U2. At the neighborhood level, the construction of the line would create a lot of induced trips and not have a high diversion rate from cars. But at the city level, little examples of diversion as more work and non-work destinations cluster in Mitte would multiply, never enough for an easy comparison, and yet enough that, as we see, more people would be living and working here without driving, where otherwise they’d be driving between two Kreise elsewhere in Germany.

Taken all together, the diversion rate at the level of trips should be considered 100%: at large enough scale, every trip by public transport is a trip not done by car, perhaps in the city, perhaps elsewhere in the country. Every p-km by public transport is multiple p-km not done by car, since dense cities allow for shorter trips without the traffic congestion problems caused by trying to fit high density and also a high modal split for driving.

With that in mind, a calculation of a first-order diversion rate is in order. A daily trip by rail is a daily trip not done by car. The average trip length in Germany by all modes is 12 km, but this is weighed down by short walking and biking trips; the average daily driving rate per car is 26 km (see table 21 of MiD) when the car is in use, and is 10,000 km/year per car. If we take 10,000 v-km to be the diversion rate per 3 public transport trips, we get that, at the emissions intensity of 2017, a daily public transport trip represents an annual emissions reduction of 0.43 t-CO2. The Märkisches Viertel extension of U8, estimated to get 25,000 trips/day, would reduce Germany-wide emissions by 10,000 t/year, which is nearly an order of magnitude more than the carbon critique of Berlin U-Bahn expansion got. At the current 670€/t cost used in German benefit-cost analyses this is around a 2% rate of return on cost purely from the carbon savings, never mind anything else – and usually green policy uses a low discount rate due to the long-term effects of greenhouse gas emissions, 1.4% in the Stern review.

Against Free Buses

Much of the public discussion over A Better Billion, our proposal to increase New York’s subway construction spending by $1 billion a year in lieu of Zohran Mamdani’s free bus plan, has taken it for granted that free buses are good, and it’s just a matter of arguing over spending priorities. Charlie Komanoff, who I deeply respect, proposes to combine subway construction with making the buses free. And yet, free buses remain a bad idea, regardless of funding, because of the effects of breaking fare integration between buses and the subway. If there is money for making the buses free, and it must go to fare reductions rather than to better service, then it should go to a broad reduction in fares, especially if it can also reduce the monthly rate in order to align with best practices.

Planning with fare integration

The current situation in New York is that buses and the subway have nearly perfect fare integration: the fares are the same, the fare-capped passes apply to both modes equally, and one free transfer (bus-bus or bus-subway) is allowed before the passenger hits the cap. Regular riders who would be taking multi-transfer trips are likely to be hitting the cap anyway so that restriction, while annoying, doesn’t change how passengers travel.

Under this regime of fare integration, buses and the subway are planned together. The bus network is not planned to connect every pair of points in the city, because the subway does that at 2.5 times the average speed. Instead, it’s designed to connect subway deserts to the subway, offer crosstown service where the subway only points radially toward the Manhattan core, and run service on streets with such high demand that buses get high ridership even with a nearby subway. The same kinds of riders use both modes.

The bus network has accumulated a lot of cruft in it over the generations and the redesigns are half-measures, but there’s very little duplication of service, if we define duplication as a bus that is adjacent to the subway and has middling or weak ridership. For example, the B25 runs on Fulton on top of the A/C, and the B37 and B63 run respectively on Third and Fifth Avenues a block away from the R, and all have middling traffic. In contrast, the Bx1/2 runs on Grand Concourse on top of the B/D but is one of the highest-ridership buses in the system. B25-type situations are rare, and most of the bus service that needs to be cut as part of system modernization is of a different form, for example routes in Williamsburg that function as circulators with maybe half the borough’s average ridership per service hour.

In this schema, the replacement of a bus with a train is an unalloyed good. The train is faster, more reliable, more comfortable. Owing to those factors, the train can also support higher ridership and thus frequency. If the train stops every 800 meters and averages 30 km/h and the bus stops every 400 and averages 15 (the current New York average is much lower; 15 is what is possible with stop consolidation from 200 to 400 meter interstations and other treatments), then it takes a 2.5 km trip for the replacement to be worth it on trip time even for a passenger living right on top of the deleted bus stop, and a 5 km one if we take into account the walk penalty – and that’s before we include all the bonuses for rail travel over bus travel, which fall under the rubric of rail bias.

The consequences of differentiated fares

All of the above planning goes out the window if there are large enough differences in fares that passengers of different classes or travel patterns take different modes. Commuter rail, not part of this system of fare integration in New York or anywhere else in the United States, is not planned in coordination with the subway or the buses, and fundamentally can’t be until the fares are fixed. Indeed, busy buses run in parallel to faster but more expensive and less frequent commuter lines in New York and other American cities, and when the buses happen to feed the stations, as at Jamaica Station on the LIRR or some Metro-North stations or at some Fairmount Line stations in Boston, interchange volumes are limited.

Commuter rail has many problems in addition to fares. But when the subway charges noticeably higher fares than the bus to the point that passengers sort by class, the same planning problems emerge. In Washington, the cheap, flat-fare bus and more expensive, distance-based fare on Metro led to two classes of users on two distinct classes of transit. When Metro finally extended to Anacostia with the opening of the Green Line in 1991, an attempt to redesign the buses to feed the station rather than competing with Metro by going all the way into Downtown Washington led to civil rights protests and lawsuits alleging that it was racist to force low-income black riders onto the more expensive product.

Whenever fares are heavily differentiated, any shift toward the higher-fare service involves such a fight. One of the factors behind the reluctance of the New York public transit advocacy sphere to come out in favor of commuter rail improvements is that those are white middle class-coded because that’s the profile of the LIRR and Metro-North ridership, caused by a combination of high fares and poor urban service. Fare integration is a fight as well, but it’s one fight per city region rather than one fight per rail project.

And more to the point, New York doesn’t even need to have that one fight at least as far as subway-bus integration is concerned, because the subways and buses are already fare integrated. What’s more, free bus supporters like Mamdani and Komanoff aren’t proposing this out of belief that fares should be disintegrated, but out of belief that it’s a stalking horse for free transit, a policy that Komanoff has backed for decades (he proposed to pair it with congestion pricing in the Bloomberg era) and that the Democratic Socialists of America have been in favor of. The latter is loosely inspired by 1960s movements and by reading many tourist-level descriptions in the American press of European cities with too weak a transit system for revenue to matter very much. Free buses in this schema are on the road to fully free transit, but then the argument for them involves the very small share of transit revenue contributed by buses rather than the subway. In effect, an attempt to make the system free led to a proposal that could only ever result in disintegrated fares, even though that is not the intent.

But good intent does not make for a good program. That free buses are not proposed with the intent of breaking fare integration is irrelevant; if the program is implemented, it will break fare integration, and turn every bus redesign into a new political fight and even create demand for buses that have no reason to exist except to parallel subway lines. The program should be rejected, not just because it costs money that can be better spent on other things, but because it is in itself bad.

Fare Practices

Here’s a table of urban public transport fares for various cities, covering the United States, Canada, parts of Europe, Turkey, and Japan. Included are single fares, multi-ride discounts, day passes, weeklies, and monthlies, with the last three shown with their ratios to single fares. As far as possible we’ve tried doing fares as of 2026, but it’s possible a few numbers are not updated and depict 2025 figures.

The thing to note is that in Continental Europe, there are steeply discounted monthlies – only two cities in the table charge for a monthly more than for 30 single-trips (Paris at 35.5, Bari at 35). Most Italian cities cluster around 20, and Barcelona, Lisbon, and especially Porto are even lower. Berlin used to have a multiplier of 32 before the 9€ monthly and the subsequent Deutschlandticket but the current multiplier is 15.75 within the city. Stockholm has a monthly multiplier of 24.7. Prague’s multiplier is 12.

Japanese monthly fares are strange by Western standards, in the sense that they are station-to-station, with subsegments allowed but no trips outside the segment; subject to this constraint the multiplier is 30-40, with small additional discount for buying 3-6 months in advance, but the unrestricted monthly fare is very high. London and Istanbul functionally do not have monthlies, in the sense that the multiplier is so high (78.5 Istanbul-wide, and it’s not truly unlimited but is capped at 180 trips/month) that except for trips within Central London it might as well not exist.

American and Canadian monthly fares are usually higher than in Continental Western Europe, with multipliers in the 30s. New York’s multiplier was especially high, about 46, and the MTA has just abolished the monthly fare entirely and phased out the MetroCard (as of the new year, starting in two hours), making people use the weekly cap with OMNY instead, which has a multiplier of 11.7 and, over a 30-day month, forces a monthly multiplier of 50. Toronto has a very high monthly multiplier as well, 46.6. This is bad practice: a high monthly discount functions as a technologically simple off-peak discount (indeed, London pairs its stingy monthly discount with a substantial off-peak discount), and OMNY itself is buggy to the point that fare inspectors on the buses can’t tell if someone has actually paid except by looking at debit card statements, which do not show one as having paid if one has a valid transfer or has reached the weekly cap (and not tapping in this case is still illegal fare dodging in New York law).

The practice of the cap, increasingly popular in the US under London influence, is rare as well. London’s fare cap originates in its complex zone system: the Underground has nine zones with zone 1 only covering Central London so that passengers taking multiple trips per day can expect to take trips across different zones that they may not be familiar with; there isn’t fare integration, but rather there’s a special surcharge on some commuter train trips and a discount on buses; peak and off-peak fares are different. Thus, the calculation for the passenger of whether to buy tickets one at a time or get a pass is difficult, so Oyster does this calculation automatically to give the most advantageous fare. In a Continental city where fares are either flat regionwide or have zones with limited granularity (often the entire metro is in the innermost zone) and monthly discounts are steep, the calculation is simple: an even semi-regular rider should always get a monthly.

American and Canadian cities typically have flat fares or a simple zone system, good fare integration between buses and the subway or light rail, and commuter rail that’s functionally unusable for urban trips rather than resembling the subway with a $2 surcharge. The use case of London does not apply to such cities. New York should not have a fare cap, but a heavily surcharged single trip, perhaps $5, and an attractive flat monthly fare, perhaps $130. This system ensures passengers are incentivized to pay and there is little opportunistic fare dodging as the user has already prepaid for the entire month, so it pairs well with proof-of-payment fare collection, common in many of the European examples (though metro systems outside Germany and its immediate vicinity do have faregates).

The overall level of the fare is determined by the willingness of the government at various levels to subsidize public transport; the table can be used to compare these at PPP rates as well. However, the distribution of fares across different products and distances is not a matter of subsidy but a matter of good and bad industry practices, and the best practice for simple fare collection is to offer a prepaid monthly at a heavy discount compared with the single ride.

New York Isn’t Special

A week ago, we published a short note on driver-only metro trains, known in New York as one-person train operation or OPTO. New York is nearly unique globally in running metro trains with both a driver and a conductor, and from time to time reformers have suggested switching to OPTO, so far only succeeding in edge cases such as a few short off-peak trains. A bill passed the state legislature banning OPTO nearly unanimously, but the governor has so far neither signed nor vetoed it. The New York Times covered our report rather favorably, and the usual suspects, in this case union leadership, are pissed. Transportation Workers Union head John Samuelsen made the usual argument, but highlighted how special New York is.

“Academics think working people are stupid,” [Samuelsen] said. “They can make data lie for them. They conducted a study of subway systems worldwide. But there’s no subway system in the world like the NYC subway system.”

Our report was short and didn’t go into all the ways New York isn’t special, so let me elaborate here:

- On pre-corona numbers, New York’s urban rail network ranked 12th in the world in ridership, and that’s with a lot of London commuter rail ridership excluded, including which would likely put London ahead and New York 13th.

- New York was among the first cities in the world to open its subway – but London, Budapest, Chicago (dating from the electrification and opening of the Loop in 1897), Boston, Paris, and Berlin all opened earlier.

- New York has some tight curves on its tracks, but the minimum curve radius on Paris Métro Line 1, 40 meters, is comparable to the New York City Subway’s.

- The trains on the New York City Subway are atypically long for a metro system, at 151 meters on most of the A division and 183 on most of the B division, but trains on some metro systems are even longer (Tokyo has some 200 m trains, Shanghai 180 m trains) and so are trains on commuter rail systems like the RER (204 m on the B, 220 m on the A), Munich S-Bahn (201 m), and Elizabeth line (205 m, extendable to 240).

- New York has crowded trains at rush hour, with pre-Second Avenue Subway trains peaking at 4 standees per square meter, but London peaks at 5/m^2 and trains in Tokyo and the bigger Chinese cities at more than that. Overall ridership, irrespective of crowding, peaked around 30,000 passengers per direction per hour on the 4 and 5 trains in New York, compared with 55,000 on the RER A.

New York is not special, not in 2025, when it’s one of many megacities with large subway systems. It’s just solipsistic, run by managers and labor leaders who are used to denigrating cities that are superior to New York in every way they run their metro systems as mere villages unworthy of their attention. Both groups are overpaid: management is hired from pipelines that expect master-of-the-universe pay and think Sweden is a lower-wage society, and labor faces such hurdles with the seniority system that new hires get bad shifts and to get enough workers New York City Transit has had to pay $85,000 at start, compared with, in PPP terms, around $63,000 in Munich after recent negotiations. The incentive in New York should be to automate aggressively, and look for ways to increase worker churn and not to turn people who earn 2050s wages for 1950s productivity be a veto point to anything.

Can Ridership Surges Disrupt Small, Frequent Driverless Metros?

A recent discussion about the Nuremberg U-Bahn got me thinking about the issue of transfers from infrequent to frequent vehicles and how they can disrupt service. The issue is that driverless metros like Nuremberg’s rely on very high frequency on relatively small vehicles in order to maintain adequate capacity; Nuremberg has the lowest U-Bahn construction costs in Germany, and Italian cities with even smaller vehicles use the combination of short stations and very high frequency to reduce costs even further. However, all of this assumes that passengers arrive at the station evenly; an uneven surge could in theory overwhelm the system. The topic of the forum discussion was precisely this, but it left me unconvinced that such surges could be real on a driverless urban metro (as opposed to a landside airport people mover). The upshot is that there should not be obstacles to pushing the Nuremberg U-Bahn and other driverless metros to their limit on frequency and capacity, which at this point means 85-second headways as on the driverless Parisian lines.

What is the issue with infrequent-to-frequent transfers?

Whenever there is a transfer from a large, infrequent vehicle to a small, frequent one, passengers overwhelm systems that are designed around a continuous arrival rate rather than surges. Real-world examples include all of the following:

- Transfers from the New Jersey Transit commuter trains at the Newark Airport station to the AirTrain.

- Transfers from OuiGo TGVs at Marne-la-Vallée to the RER.

- In 2009, transfers from intercity CR trains at Shanghai Station to the metro.

In the last two cases, the system that is being overwhelmed is not the trains themselves, which are very long. Rather, what’s being overwhelmed is the ticket vending machines: in Shanghai the TVMs frequently broke, and with only one of three machines at the station entrance in operation, there was a 20-minute queue. A similar queue was observed at Marne-la-Vallée. Locals have reusable farecards, but non-locals would not, overwhelming the TVM.

In the first case, I think the vehicles themselves are somewhat overwhelmed on the first train that the commuter train connects to, but that is not the primary system capacity issue either. Rather, the queues at the faregates between the two systems can get long (a few minutes, never 20 minutes).

In contrast, I have never seen the transfer from the TGV to the Métro break the system at Gare de Lyon. The TGV may be unloading 1,000 passengers at once, but it takes longer for all of them to disembark than the headway between Métro trains; I’ve observed the last stragglers take 10 minutes to clear a TGV Duplex in Paris, and between that, long walking paths from the train to the Métro platforms, and multiple entrances, the TGV cannot meaningfully be a surge. Nor have I seen an airplane overwhelm a frequent train, for essentially the same reason.

What about school trips?

The forum discussion brings up two surges that limit the capacity of the Nuremberg U-Bahn: the airport, and school trips. The airport can be directly dispensed with – individual planes don’t do this at airside people movers, and don’t even do this at low-capacity landside people movers like the JFK and Newark AirTrains. But school trips are a more intriguing possibility.

What is true is that school trips routinely overwhelm buses. Students quickly learn to take the last bus that lets them make school on time: this is the morning and they don’t want to be there, so they optimize for how to stay in bed for just a little longer. Large directional commuter volumes can therefore lead to surges on buses: in Vancouver, UBC-bound buses routinely have passups in the morning rush hour, because classes start at coordinated times and everyone times themselves to the last bus that reaches campus on time.

However, the UBC passups come from a combination of factors, none of which is relevant to Nuremberg:

- They’re on buses. SkyTrain handles surges just fine.

- UBC is a large university campus tucked at the edge of the built-up area.

- UBC has modular courses, as is common at American universities, and coordinated class start and end times (on the hour three days a week, every 1.5 hours two days a week).

It is notable that Vancouver does not have any serious surges coming from school trips, even with trainsets that are shorter than those of Nuremberg (40 meters on the Canada Line and 68-80 meters on the Expo and Millennium lines, compared with 76 meters). Schools are usually sited to draw students from multiple directions, and are usually not large enough to drive much train crowding on their own. A list on Wikipedia has the number of students per Gymnasium, and they’re typically high three figures with one at 1,167, none of which is enough to overwhelm a driverless 76 meter long train. Notably, school trips do not overwhelm the New York City Subway; New York City Subway rolling stock ranges from 150 to 180 meters long rather than 76 as in Nuremberg, but then the specialized high schools go as far up as 5,800 students, and one has 3,000 and is awkwardly located in the North Bronx.

Indeed, neither Vancouver nor New York schedules its trains based on whether school is in session. Both run additional buses on school days to avoid school surges, but SkyTrain and the subway do not run additional vehicles, and in both formal planning and informal railfan lore about crowding, school trips are not considered important. So school surges are absolutely real on buses, and university surges are real everywhere, but not enough to overwhelm trains. Nuremberg should not consider itself special on this regard, and can plan its U-Bahn systems as if it does not have special surges and passengers do arrive continuously at stations.

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 Station Design is Incompetent

A few hours ago, the MTA presented on the latest of Second Avenue Subway Phase 2. The presentation includes information about the engineering and construction of the three stations – 106th, 116th, and 125th Streets. The new designs are not good, and the design of 116th in particular betrays severe incompetence about how modern subway stations are built: the station is fairly shallow, but has a mezzanine under the tracks, with all access to or from the station requiring elevator-only access to the mezzanine.

What was in the presentation?

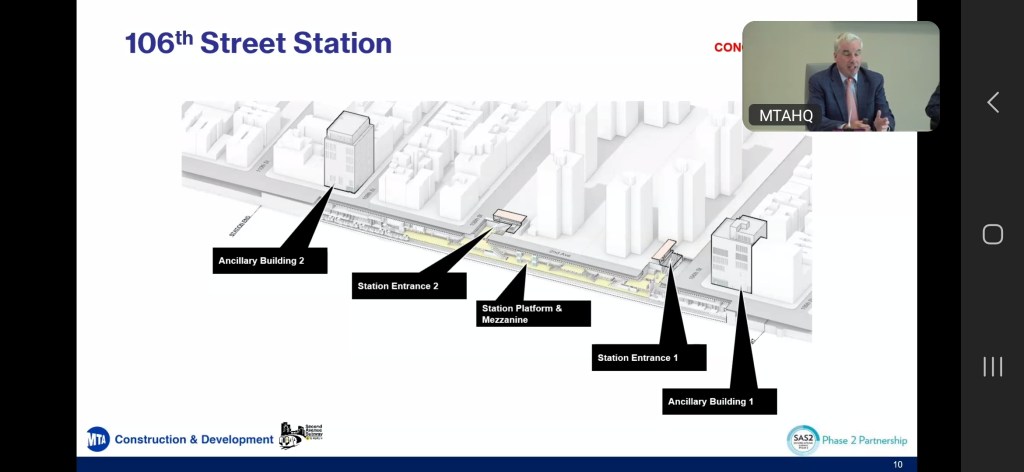

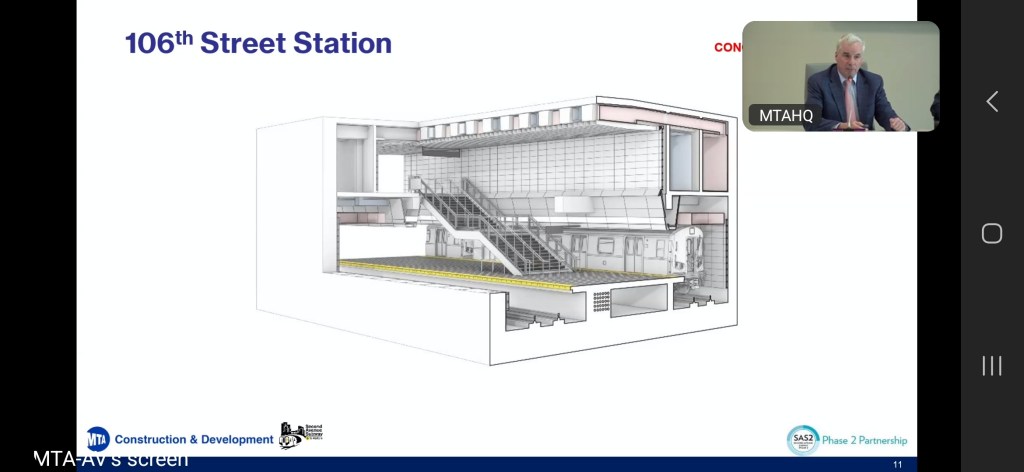

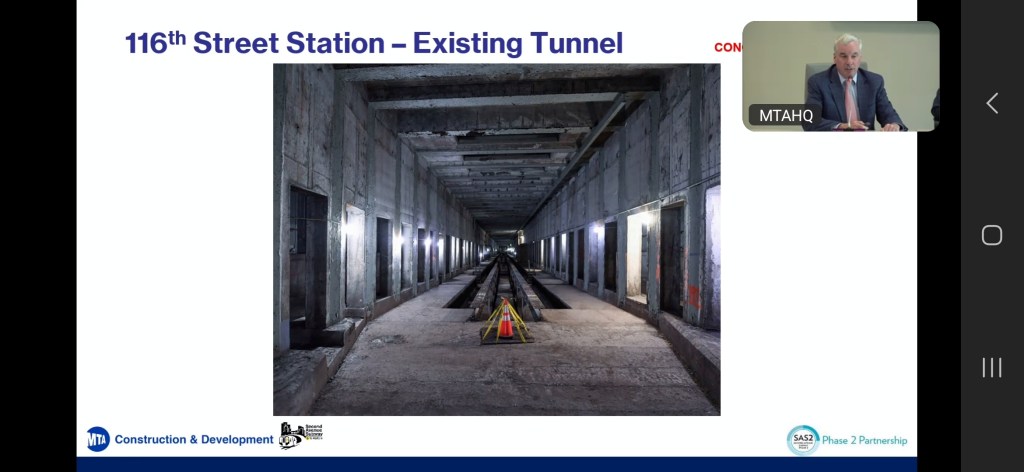

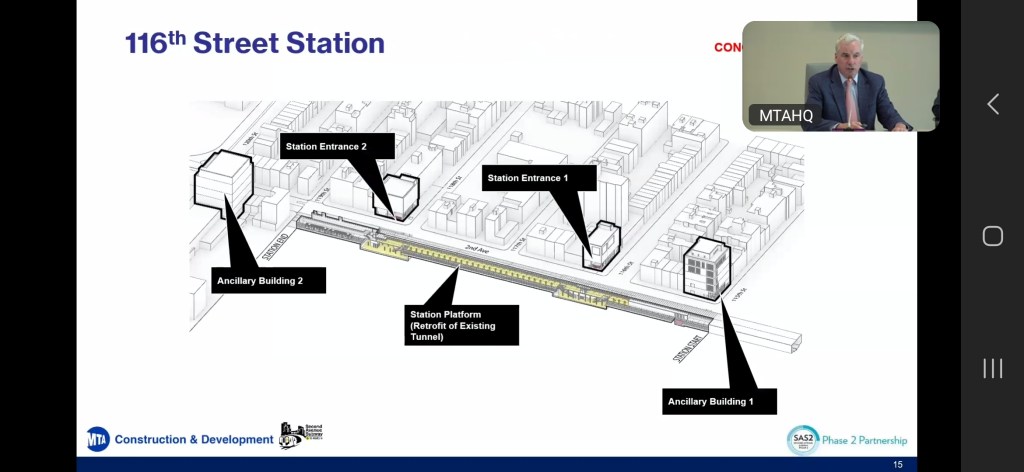

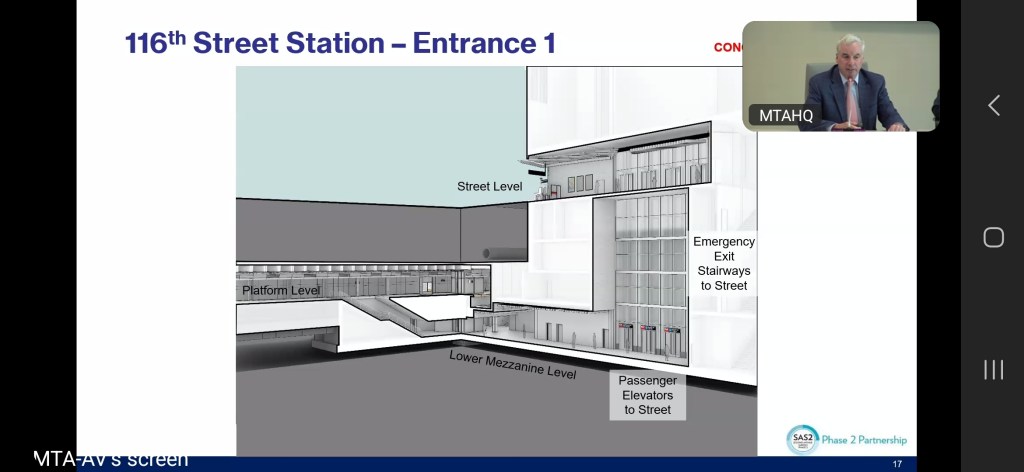

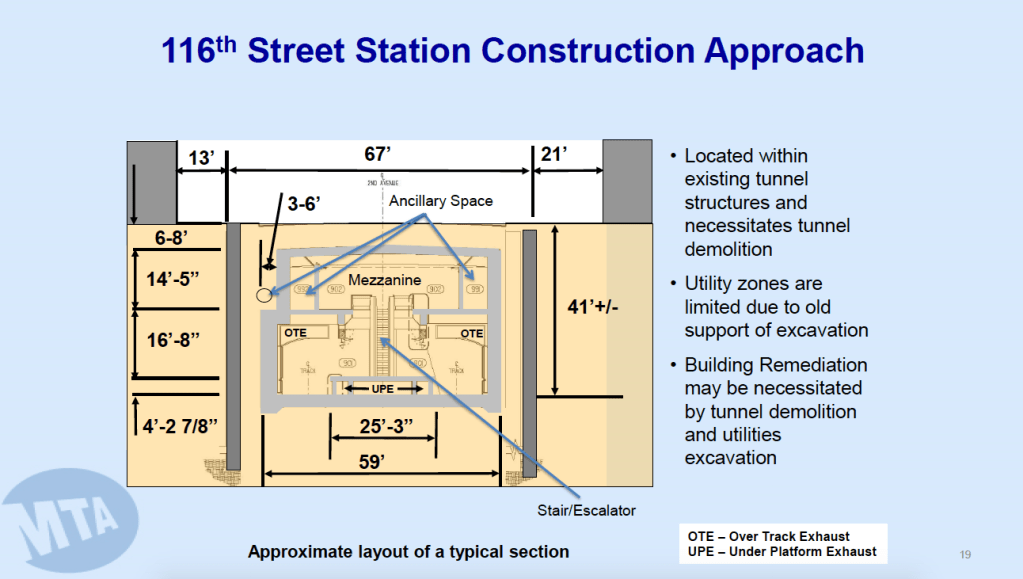

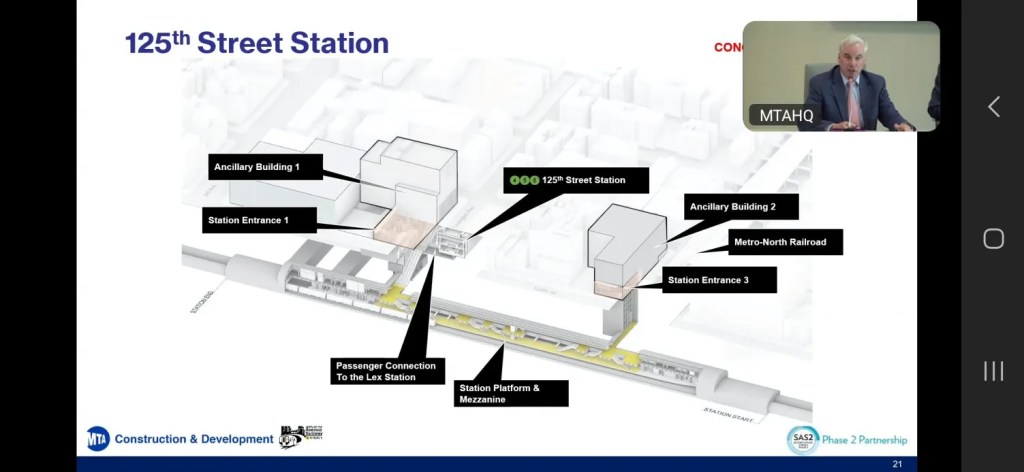

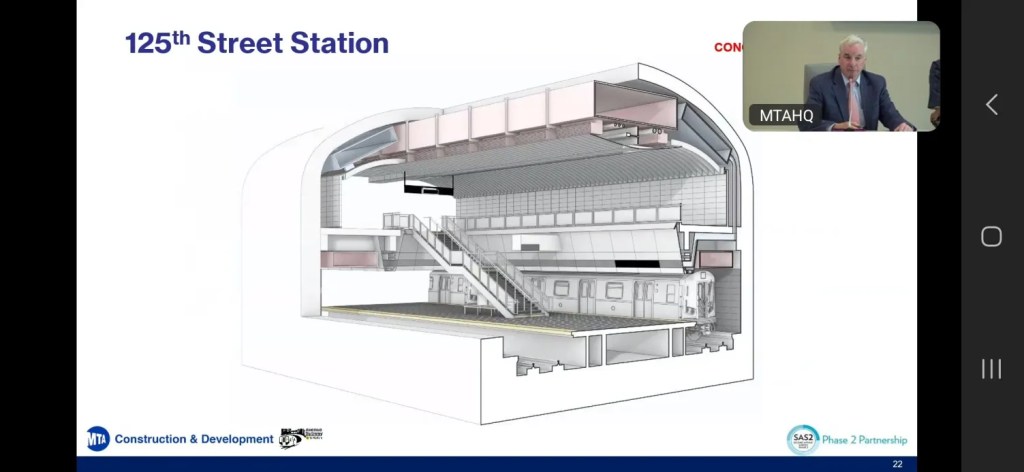

Here is a selection of slides, describing station construction. 106th Street is to be built cut-and-cover; 116th is to use preexisting construction but avoid cut-and-cover to reach them from the top and instead mine access from the bottom; 125th is to be built deep-level, with 125′ deep (38 m) platforms, underneath its namesake street between Lexington and Park Avenues.

The problems with 116th Street

Elevator-only access

Elevator-only access is usually stupid. It’s especially stupid when it’s at a shallow station; as the page 19 slide above shows, the platforms are about 11.5 meters below ground, which is an easy depth for both stair and escalator access.

Now, to be clear, there are elevator-only stations built in countries with reasonable subway construction programs. Sofia on Nya Tunnelbanan is elevator-only, because it is 100 meters below street level, due to the difficult topography of Södermalm and Central Stockholm, in which Sofia, 26 meters above sea level, is right next to Riddarfjärden, 23 meters deep. Emergency access is provided via ramps to the sea-level freeway hugging the north shore of Södermalm, used to construct the mined cavern in the first place. Likewise, the Barcelona L9 construction program, by far the most expensive in Spain and yet far cheaper than in any recent English-speaking country, has elevator-only access to the deep stations, in order to avoid any construction outside a horizontal or vertical tunnel boring machine.

The depth excuse does not exist in East Harlem. 11.5 meters is not an elevator-only access depth. It’s a stair access depth with elevators for wheelchair accessibility. Stairs are planned to be provided only for emergency access, without public usage. Under NFPA 130 the stairs are going to have to have enough capacity for full trains, much more than is going to be required in ordinary service, and they’d lead passengers to the same street as the elevators, nothing like the freeway egress of Sofia.

Below-platform mezzanines

To avoid any shallow construction, the mezzanines will be built below the platforms and not above them. As a result, access to the station means going down a level and then going back up to the platform level. In effect, the station is going to behave as a rather deep station as far as passenger access time to the platforms is concerned: the planned depth is 57′, or 17.4 meters, which means that the total vertical change from street level is around 23.5 meters, twice the actual depth of the platforms.

Dig volume

Even with the reuse of existing infrastructure, the station is planned to have too much space north and south of the platforms, as seen with the locations of the ancillary buildings.

I think that this is due to designs from the 2000s, when the plan was to build all stations with extensive back-of-the-house space on both sides of the platform. Phase 1 was built this way, as we cover in our New York case, and after we yelled at the MTA about it, it eventually shrank the footprint of the stations. 116th’s station start and end are four blocks apart, a total of about 300 meters, comparable to 86th Street; the platform is 186 m wide and the station overall has no reason to be longer than 190-200. But it’s possible the locations of the ancillary buildings were fixed from before the change, in which case the incompetence is not of the current leadership but of previous leadership.

Why?

On Bluesky, I’m seeing multiple activists I think well of assume that this is because the MTA is under pressure to either cut costs or avoid adverse community impact. Neither of these explanations makes much sense in context. 106th Street is planned to be built cut-and-cover, in the same neighborhood as 116th, with the same street width, which rules out the community opposition explanation. Cut-and-cover is cheaper than alternatives, which also rules out the cost explanation.

Rather, what’s going on is that MTA leadership does not know how a modern cut-and-cover subway station looks like. American construction prefers to avoid cut-and-cover even for stations, and over time such stations have been laden with things that American transit managers think are must-haves (like those back-of-the-house spaces) and that competent transit managers know they don’t need to build. They may want to build cut-and-cover, as at 106th, but as soon as there’s a snag, they revert to form and look for alternatives. They complain about utility relocation costs, which are clearly not blocking this method at 106th, and which did not prevent Phase 1’s 96th Street from costing about 2/3 as much as 86th and 72nd per cubic meter dug.

Under pressure to cut costs and shrink the station footprint, the MTA panicked and came up with the best solution the political appointees, that is to say Janno Lieber and Jamie Torres-Springer and their staff, and the permanent staff that they deign to listen to, could do. Unfortunately for New York, their best is not good enough. They don’t know how to build good stations – there are no longer any standardized designs for this that they trust, and the people who know how to do this speak English with an accent and don’t earn enough to command the respect of people on a senior American political appointee’s salary. So they improvise under pressure, and their instincts, both at doing things themselves and at supervising consultants, are not good. To Londoners, Andy Byford is a workhorse senior civil servant, with many like him, and the same is true in other large European cities with large subway systems. But to Americans, the such a civil servant is a unicorn to the point that people came to call him Train Daddy, because this is what he’s being compared with.

Against State of Good Repair

We’re releasing our high-speed rail report later this week. It’s a technical report rather than a historical or institutional one, so I’d like to talk about a point that is mentioned in the introduction explaining why we think it’s possible to build high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor for $17 billion: the current investment program, Connect 2037, centers renewal and maintenance more than expansion, under the moniker State of Good Repair (SOGR). In essence, megaprojects have a set of well-understood problems of high costs and deficient outcomes, behind-the-scenes maintenance has a different set of problems, and SOGR combines the worst of both worlds and the benefits of neither. I’ve talked about this before in other contexts – about Connecticut rail renewal costs, or leakage in megaproject budgeting, or the history of SOGR on the New York City Subway, or Northeast Corridor catenary. Here I’d like to synthesize this into a single critique.

What is SOGR?

SOGR is a long-term capital investment to bring all capital assets into their expected lifespan and maintenance status. If a piece of equipment is supposed to be replaced every 40 years and is currently over 40, it’s not in good repair. If the mean distance between failures falls below a certain prescribed level, it’s not in good repair. If maintenance intervals grow beyond prescription, then the asset to be maintained is not in good repair. In practice, the lifespans are somewhat conservative so in practice a lot of things fall out of good repair and the system keeps running. The upshot is that because the maintenance standards are somewhat flexible, it’s easy to defer maintenance to make the system look financially healthier, or to deal with an unexpected budget shortfall.

Modern American SOGR goes back to the New York subway renewal programs of the 1980s and 90s, which worked well. The problem is that, just as the success of one infrastructure expansion tempts the construction of other, less socially profitable ones, the success of SOGR tempted agencies to justify large capital expenses on SOGR grounds. In effect, what should have been a one-time program to recover from the 1970s was generalized as a way of doing maintenance and renewal to react to the availability of money.

Megaprojects and non-megaprojects

In practice, what defines a megaproject is relative – a 6 km light rail extension is a megaproject in Boston but not in Paris – and this also means that they are not easy to locally benchmark, or else there would be many like them and they would be more routine. This means that megaprojects are, by definition, unusual. Their outcome is visible, and this attracts high-profile politicians and civil servants looking to make their mark. Conversely, their budgeting is less visible, because what must be included is not always clear. This leads to problems of bloat (this is the leakage problem), politicization, surplus extraction, and plain lying by proponents.

Non-megaprojects have, in effect, the opposite set of problems. Their individual components can be benchmarked easily, because they happen routinely. A short Paris Métro extension, a few new infill stations, and a weekend service change for track renewal in New York are all examples of non-megaprojects. These are done at the purely professional level, and if politicians or top managers intervene, it’s usually at the most general level, for example the institution of Fastrack as a general way of doing subway maintenance, and that too can be benchmarked internally. In this case, none of the usual problems of megaprojects is likely. Instead, problems occur because, while the budgeting can be visible to the agency, the project itself is not visible to the general public. If an entire new subway line’s construction fails and the line does not open, this is publicly visible, to the embarrassment of the politicians and agency heads who intended to take credit for it. In contrast, if a weekend service change has lower productivity than usual, the public won’t know until this problem has metastasized in general, by which point the agency has probably lost the ability to do this efficiently.

And to be clear, just as megaprojects like new subway lines vary widely in their ability to build efficiently, so do non-megaproject capital investments vary, if anything even more. The example I gave writing about Connecticut’s ill-conceived SOGR program, repeated in the high-speed rail report, is that per track- or route-km the state spends in one year about 60% as much as what Germany spends on a once per generation renewal program, to be undertaken about every 35 years. Annually, the difference is a factor of about 20. New York subway maintenance has degraded internally over time, due to ever tighter flagging rules, designed for worker protection, except that worker injuries rose from 1999 to the 2010s.

The Transit Costs Project

The goal of the Transit Costs Project is to use international benchmarking to allow cities to benefit from the best of both worlds. Megaprojects benefit from public visibility and from the inherent embarrassment to a politician or even a city or state that can’t build them: “New York can’t expand the subway” is a common mockery in American good-government spaces, and people in Germany mock both Bavaria for the high costs and long timeline of the second Munich S-Bahn tunnel and Berlin for, while its costs are rather normal, not building anything, not even the much-promised tram alternatives to the U-Bahn. Conversely, politicians do get political capital from the successful completion of a megaproject, encouraging their construction, even when not socially profitable.

Where we come in is using global benchmarking to remove the question marks from such projects. A subway extension may be a once in a generation effort in an American city, but globally it is not, and therefore, we look into how as much of the entire world as we can see into does this, to establish norms. This includes station designs to avoid overbuilding, project delivery and procurement strategies, system standards, and other aspects. Not even New York is as special as it thinks it is.

To some extent, this combination of the best features of both megaprojects and non-megaprojects exists in cities with low construction costs. This is not as tautological as it sounds. Rather, I claim that when construction costs are low, even visible extensions to the system fall below the threshold of a megaproject, and thus incremental metro extensions are built by professionals, with more public visibility providing a layer of transparency than for a renewal project. This way, growth can sustain itself until the city runs out of good places to build or until an economic crisis like the Great Recession in Spain makes nearly all capital work stop. In this environment, politicians grow to trust that if they want something big built, they can just give more money to more of the same, serving many neighborhoods at once.

In places with higher costs, or in places that are small enough that even with low costs it’s rare to build new metro lines, this is not available. This requires the global benchmarking that we use; occasionally, national benchmarking could work, in a country with medium costs and low willingness to build (for example, Germany), but this isn’t common.

The SOGR problem

If what we aim to do with the Transit Costs Project is to combine the positive features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects, SOGR does the exact opposite. It is conceived as a single large program, acting as the centerpiece of a capital plan that can go into the tens of billions of dollars, and is therefore a megaproject. But then there’s no visible, actionable, tangible promise there. There is no concrete promise of higher speed or capacity. To the extent some programs do have such a promise, they are subsumed into something much bigger, which means that failing to meet standards on (say) elevator reliability can be excused if other things are said to go into a state of good repair, whatever that means to the general public.

Thus, SOGR invites levels of bloat going well beyond those of normal expansion megaprojects. Any project can be added to the SOGR list, with little oversight – it isn’t and can’t be locally benchmarked so there is no mid-career professional who can push back, and conversely it isn’t so visible to the general public that a general manager or politician can push back demanding a fixed opening deadline. For the same reason, inefficiency can fester, because nobody at either the middle or upper level has the clear ability to demand better.

Worse, once the mentality of SOGR is accepted, more capital projects, on either the renewal side or the expansion side, are tied to it, reducing their efficiency. For example, the catenary on the Northeast Corridor south of New York requires an upgrade from fixed termination/variable tension to auto-tension/constant tension. But Amtrak has undermaintained the catenary expecting money for upgrades any decade now, and now Amtrak claims that the entire system must be replaced, not just the catenary but also the poles and substations. The language used, “the system is falling apart” and “the system is maintained with duct tape,” invites urgency, and not the question, “if you didn’t maintain this all this time, why should we trust you on anything?”. With the skepticism of the latter question, we can see that the substations are a separate issue from the catenary, and ask whether the poles can be rebuilt in place to reduce disruption, to which the vendors I’ve spoken with suggested the answer is yes using bracing.

The Connecticut track renewal program falls into the same trap. With no tangible promise of better service, the state’s rail lines are under constant closures for maintenance, which is done at exceptionally low productivity – manually usually, and when they finally obtained a track laying machine recently they’ve used it at one tenth its expected productivity. Once this is accepted as the normal way of doing things, when someone from the outside suggests they could do better, like Ned Lamont with his 30-30-30 proposal, the response is to make up excuses why it’s not possible. Why disturb the racket?

The way forward

The only way forward is to completely eliminate SOGR from one’s lexicon. Big capital programs must exclusively fund expansion, and project managers must learn to look with suspicion on any attempt to let maintenance projects piggyback on them.

Instead, maintenance and renewal should be budgeted separately from each other and separately from expansion. Maintenance should be budgeted on the same ongoing basis as operations. If it’s too expensive, this is evidence that it’s not efficient enough and should be mechanized better; on a modern railroad in a developed country, there is no need to have maintenance of way workers walk the tracks instead of riding a track inspection train or a track laying machine. With mechanized maintenance, inventory management is also simplified, in the sense that an entire section of track has consistent maintenance history, rather than each sleeper having been installed in a different year replacing a defective one.

Renewal can be funded on a one-time basis since the exact interval can be fudged somewhat and the works can be timed based on other work or even a recession requiring economic stimulus. But this must be held separate from expansion, again to avoid the Connecticut problem of putting the entire rail network under constant maintenance because slow zones are accepted as a fact of life.

The importance of splitting these off is that it makes it easier to say “no” to bad expansion projects masquerading as urgent maintenance. No, it’s not urgent to replace a bridge if the cost of doing so is $1 billion to cross a 100 meter wide river. No, the substations are a separate system from the overhead catenary and you shouldn’t bundle them into one project.

With SOGR stripped off, it’s possible to achieve the Transit Costs Project goal of combining the best rather than the worst features of megaprojects and non-megaprojects. High-speed rail is visible and has long been a common ask on the Northeast Corridor, and with the components split off, it’s possible to look into each and benchmark to what it should include and how it should be built. Just as New York is not special when it comes to subways, the United States is not special when it comes to intercity rail, it just lags in planning coordination and technology. With everything done transparently based on best practices, it is indeed possible to build this on an expansion budget of about $17 billion and a rounding-error track laying machine budget.

Open BRT

BRT, or bus rapid transit, can be done in one of two ways: closed and open. Closed systems imitate rail lines, in that there is a BRT route along the entire length of the corridor; open ones instead take a trunk route, upgrade it with dedicated lanes and other BRT features, and let routes run through from it to branches that are not so equipped, perhaps because there is less traffic on the branches. I complained 14 years ago that New York City Transit was planning closed BRT in the form of SBS on Hylan Boulevard on Staten Island, a good route for open BRT. Well, now the MTA is planning BRT on the disused North Shore Branch of the Staten Island Railway, arguing that it is better than reactivating rail service because buses could use it as an open corridor – except that this is a poor corridor for open BRT. This leads to the question: which corridors are good for open BRT to begin with?

Trunks and branches are good

Open BRT can be analogized to a Stadtbahn system, fast in the core and slow outside it. Like a Stadtbahn, it works best where several branches can converge onto a single route, where the high traffic both requires higher capacity and justifies higher investment; just as grade separation increases the throughput of a rail line, BRT treatments increase those of a bus through greater separation from other traffic and regularity of service.

Unlike a Stadtbahn, open BRT remains a bus. This means two things:

- The trunk route must itself be a strong surface route. It had better be a wide street with room for physically separated bus lanes, or else a city center route that could be turned into a transit mall. A Stadtbahn system puts the fast central portion underground and could do it independently of the street network, or even run under a slow narrow street like Tremont Street in Boston.

- The connections from the trunk route to the branches must themselves be strong bus links. If the bus needs to zigzag on narrow residential streets to get between two wider arterials, then it will be unreliable and slow even if one of the wider arterials gets dedicated lanes. A Stadtbahn system can tunnel a few hundred meters here and there to ensure the onramps are adequate, but a surface bus system cannot, not without driving its cost structure to that of a subway but with few of the benefits of underground running.

The North Shore Branch could pass a modified version of criterion 1, but fails criterion 2. In general, former rail lines are bad for such BRT systems, since the street network was never set up for such connections. In contrast, street networks with a central artery and streets of intermediate importance between it and residential side streets emanating from it, which were never used for grade-separated rail lines, are more ideal for this treatment.

Grids are bad

Street grids eliminate the branch hierarchy of traditional street networks. There is still a hierarchy of more and less important grid streets – in Manhattan, the avenues and two-way streets are wider and more used for traffic than the one-way streets – but there is little branching. Bus networks can still branch if they move between streets, which happens in Manhattan, but it’s not usually a good idea: Barcelona’s Nova Xarxa uses the grid to run mostly independent bus routes, each route mostly sticking to a grid arterial, and the extent of branching on the Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx bus networks is limited to a handful of short segments like the Washington Bridge.

In situations like this, open BRT would not work. Hylan is possibly the only route in New York that has any business running open BRT. For this reason, our Brooklyn bus redesign proposal, and any work we could do for Queens, Manhattan, or the Bronx, eschews the open BRT concept. The buses are upgraded systemwide, since features like off-board fare collection and wider stop spacing are not really special BRT features but are rather normal in, for example, the urban German-speaking world. Center bus lanes are provided wherever there is need and room. There is more identification of a bus route with the street it runs on, but it isn’t really closed BRT, which is a series of treatments giving the BRT routes dedicated fleets and stations, for example with left-side doors to board from metro-style island platforms like Transmilenio.

What this means more broadly is that the open BRT is not a good fit for most of North America, with its grid routes. Occasionally, a diagonal street could act as a trunk if available, but this is uncommon. Broadway is famous for running diagonally to the Manhattan grid, but that’s not a BRT route but a subway route.

Transit Advocacy and (Lack of) Ideology in New York

I wrote recently about ideology in transit advocacy and in advocacy in general. The gist is that New York lacks any ideological politics, and as a result, transit advocacy either is genuinely non-ideological, or sweeps ideology under the rug; dedicated ideological advocates tend to either be subsumed in this sphere or go to places that don’t really connect with transit as it is and propose increasingly unhinged ideas. The ideological mainstream in the city is not bad, but the lack of choice makes it incapable of delivering results, and the governments at both the city and state levels are exceptionally clientelist, due to the lack of political competition. I’m not optimistic about political competition at the level of advocacy, but it would be useful to try introducing some in order to create more surface area for solutions to come through, and to make it harder for lobbyists to buy interest groups.

Political divides in New York

The political mainstream in New York is broadly left-liberal. New York voters consistently vote for federal politicians who promise to avoid tax cuts on high-income earners and corporations and even increase taxes on this group, and in exchange increase spending on health care, with some high-profile area politicians pushing for nationwide universal health care. They vote for more stringent regulations on businesses, for labor-friendlier administrative actions during major strikes, and for more hawkish solutions to climate change.

And none of that is really visible in state or city politics. Moreover, there isn’t really any political faction that voters can pick to support any of these positions, or to oppose them (except the Republicans, who are well to the right of the median state voter). The Working Families Party exists to cross-endorse Democrats via a different line; there is no fear by a Democrat that if they are too centrist for the district voters will replace them with a WFP representative, or that if they are too left-wing they will replace them with a non-WFP representative. There was a primary bloodbath in 2018, but it came from people running for the State Senate as party Democrats opposed to the Cuomo-endorsed Independent Democratic Conference, which broke from the party to caucus with Republicans.

The political divides that do exist, especially at the city level, break down as machine vs. reform candidates. But even that is not always clear, even as Eric Adams is unambiguously machine. The 2013 Democratic mayoral primary did not feature a clear machine candidate facing a clear reform candidate: Bill de Blasio ran on an ideologically progressive agenda, and implemented one small element of it in universal half-day pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds, but he ingratiated himself with the Brooklyn machine, to the point of steering endorsements in the 2021 primary toward Adams, and against the reform candidate, his own appointee Kathryn Garcia.

Political divides and advocacy

The mainstream of political opinion in New York ranges from center to mainline-left. But within that mainstream, there is no ideological competition, not just in politics, but also in advocacy. Transit advocacy, in particular, is not divided into more centrist and more left-wing groups.

The main transit advocacy groups in New York are instead distinguished by focus and praxis, roughly in the following way:

- The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA (PCAC) is on the inside track of advocacy, proposing small changes within the range of opinions on the MTA board.

- Riders Alliance (RA) is on the outside track, focusing on public transit, with praxis that includes rallies, joint proposals with large numbers of general or neighborhood-scale advocacy groups, and some support for lawfare (they are part of the lawsuit against Kathy Hochul’s cancellation of congestion pricing).

- Transportation Alternatives (TransAlt) focuses on street-level changes including pedestrian and bike advocacy, using the same tools of praxis as RA.

- Streetsblog is advocacy-oriented media.

- Straphangers Campaign is subway-focused, and uses reports and media outreach as its praxis, like the Pokey Awards for the slowest bus routes.

- Charlie Komanoff (of the Carbon Tax Center) focuses on producing research that other advocacy groups can use, for example about the benefits of congestion pricing.

The group I’m involved in, the Effective Transit Alliance, is distinguished by doing technical analysis that other groups can use, for example on RA’s Six-Minute Service campaign (statement 1, statement 2), or other-city groups pushing rail electrification; it is in the middle between outside and inside strategies.

Of note, none of these is distinguished by ideology. There is no specifically left-wing transit advocacy group, focusing on issues like supporting the TWU and ATU in disputes with management, getting cops off the subway, and investing in environmental justice initiatives like bus depot electrification to reduce local diesel pollution.

Neither is there a specifically neoliberal transit advocacy group. There are plenty of general advocacy groups with that background, like Abundance New York, but they’re never specific to transit, and much of their agenda, like expansion of renewable power, would not offend ideological socialists. YIMBY as a movement has neoliberal roots, going back to the original New York YIMBY publication, but these days is better viewed as a reform movement fighting the reformers of the last quarter of the 20th century, with the machine adjudicating between the two sides (City of Yes is an Adams proposal; the machine was historically pro-developer).

Instead, all advocacy groups end up arguing using a combination of median-New Yorker ideological language and technocratic proposals (again, Six-Minute Service). Taking sides in labor versus management disputes is viewed as the domain of the unions and managers, not outside groups. RA’s statement on cops on the subway is telling: it uses left-wing NGO language like “people experiencing homelessness,” but of its four policy proposals, only the last, investing in supportive housing for the homeless, is ideologically left-wing, and the first and third, respectively six-minute service and means-tested fare reductions for the poor, would find considerable support in the growing neoliberal community.

The consequences to the extremes

If the mainstream in New York ranges from dead center to center-left, both the general right and the radical left end up on the extremes. These have their own general advocacy groups: the Manhattan Institute (MI) on the right, and the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and its allies on the radical left. MI has recently moved to the right on national culture war issues, especially under Reihan Salam as he hired Christopher Rufo, but on local governance issues it’s not at all radical, and highlights center-right concerns with crime and with waste, fraud, and abuse in the public sector. DSA intends to take the most radical left position on issues that is available within the United States.

And both, as organizations, are pretty bad on this issue. MI, in particular, uses SeeThroughNY, the applet for public-sector worker salaries, not for analysis, but for shaming. I’ve had to complain to MI members on Twitter just to get the search function on job titles to work better, and even after they did some UI improvements, it’s harder to find the average salaries and headcounts by position to figure out things like maintenance worker productivity or white-collar overhead rates, than to find the highest-paid workers in a given year and write articles in the New York Post to shame them for racking so much overtime.

Then there is the proposal, I think by Nicole Gelinas, to stop paying subway crew for their commutes. This is not possible under current crew scheduling: train operators and conductors pick their shifts in seniority order, and low-seniority workers have no control over which of the railyards located at the fringes of the city they will have to report to. A business can reasonably expect a worker to relocate if the place the worker reports to will stay the same for the next few years; but if the schedules change every six months and even within this period they send workers to inconsistent railyards, it is not reasonable and the employer must pay for the commute, which in this circumstance is within private-sector norms.

DSA, to the extent it has a dedicated platform on public transit, is for free transit, and failing that, for effectively decriminalizing fare beating. More informed transit advocates, even very left-wing ones, persistently beg DSA to understand that for any given subsidy level, it’s better to increase service than to reduce fares, with exceptions only for places with extremely low ridership, low average rider incomes, and near-zero farebox recovery ratios. In Boston, Michelle Wu was even elected mayor on this agenda; her agenda otherwise is good, but MBTA farebox recovery ratios are sufficient that the revenue loss would bite, and as a result, all the city has been able to fund is some pilot projects on a few bus routes, breaking fare integration in the process since there is no way the subway is going fare-free.

In both cases, what is happening is that the ideological advocacy groups are distinct from the transit advocacy groups, and people are rarely well-respected in both – at most, they can be on the edge in both (like Gelinas). The result is that DSA will come up with ideas that are untethered from the reality of transit, and that every left-wing idea that could work would rapidly be taken up by groups that are not ideologically close to DSA, giving it a neoliberal reputation; symmetrically, this is true of the entire right, including MI.

The limits of the lack of ideology

The lack of ideology is not a good thing. With no ideological competition, voters have no clear way of picking politicians, which results in dynasties and handpicked successors. Lobbyists know who they need to curry favor with, making it cheaper to buy the government than to improve productivity; once it’s cheap to buy the government, the tax system ends up falling on whoever has been worst at buying influence, leading to high levels of distortion even with tax rates that, by Western European standards, are not high.

The quality of government in this situation is not good; corruption parties are not good when they govern entire countries, like the LDP in Japan or Democrazia Cristiana in Cold War Italy, and they’re definitely not good at the subnational level, where there is less media oversight. On education, for example, New York City pays starting teachers with a master’s degree $72,832/year in 2024, which compares with a German range for A13 starting teachers (in most states covering all teachers, in some only academic secondary teachers) of 50,668€/year in Rhineland-Pfalz to 57,288€/year in Bavaria; the PPP rate these days is 1€ = $1.45, so German teachers earn 1-14% more than their New York counterparts, while the average income from work ranges from 5% higher in New York than in Bavaria to 68% higher than Saxony-Anhalt. This stinginess with teacher salaries does not go to a higher teacher-to-student ratios, both New York and Germany averaging about 1:13, or to savings on the education budget, New York spending around twice as much as Germany. The waste is not talked about in the open, and even the concept that teachers deserve a raise, independently of budgetary efficiency, does not exist in city politics; it’s viewed as the sole domain of the unions to demand salary increases, and the idea that people can elect more pro-labor politicians who run on explicit platforms of salary increases is unthinkable.

In transit, I don’t have a good comparison of New York. But I do suspect that the single-party rule of CSU in Bavaria is responsible for the evident corruption levels in the party and the high costs of the urban rail projects that CSU cares about, namely the Munich S-Bahn second trunk line, which is setting Continental European records for its high costs. Likewise, in Italy, the era of DC domination was also called the Tangentopoli, and bribes for contracts were common, raising costs; the destruction of that party system under mani pulite and its replacement with alternation of power between left and right coalitions since has coincided with strong anti-corruption laws and real reductions in costs from the levels of the 1980s.

We haven’t found corruption in New York when researching the Second Avenue Subway case. But we have found extreme levels of intellectual laziness at the top, by political appointees who are under pressure not to innovate rather than to showcase success.

And likewise, at ETA, I’m seeing an advocacy sphere that is constrained by court politics. It’s considered uncouth to say that the governor is a total failure and so are all of her and her predecessor’s political appointees until proven otherwise. There’s no party or faction system that has incentives to find and publicize their failures; as it is, the people trying to replace Adams as mayor are barely even factional, and name recognition is so important that Andrew Cuomo is thinking of making a comeback, perhaps to kill another few tens of thousands of city residents that he missed in 2020. Any advocacy subject to these constraints will fail to break the hierarchy that resists change, and reduce itself to flattering failed leaders in vain hopes that they might one day implement one good idea, take credit for it, and use the credit to legitimize their other failures.

Is there a way out?

I’m pessimistic; there’s a reason I chose not to live in New York despite, effectively, working there. Alternation of parties at the state or even city level is not useful. The Republicans are a permanent minority party in New York, at least in federal votes, and so a Republican who wants to win needs to not just moderate ideologically, which is not enough by itself, but also buy off non-ideological actors, leading to comparable levels of clientelism to those of the Democratic machine.

For example, Mike Bloomberg ran on his own technocratic competence, but lacking a party to work with in City Council, he failed on issues that today are considered core neoliberal priorities, namely housing. Housing permitting in 2002-13, when the city was economically booming, averaged 20,276/year, or around 2.5/1,000 people, rising slightly to 25,222/year, or around 3/1,000, during Bill de Blasio’s eight years; every European country builds more except economic basket cases, and the major cities and metro areas typically build more than the national average. The system of councilmanic privilege, in which City Council defers to the opinions of the member representing the district each proposed development, is a natural outgrowth of the lack of ideological competition, and blocks housing production; the technocrat Bloomberg was less capable of striking deals to build housing than the political hack de Blasio. And Bloomberg is a best-case scenario; George Pataki as governor was not at all a reformer, he just had somewhat different (mostly Long Island) clientelist interests.

David Schleicher proposes state parties as a solution to the system of single-party domination and councilmanic privilege. But in practice, there’s little reason for such parties to thrive. If two New York parties aim for the median state voter, then one will comprise Republicans and the rightmost 20% of Democrats and the other will comprise the remaining Democrats, and Democrats from the former party will be required to defend so many Republican policies for coalitional reasons. There’s no neat separation of state and federal priorities that would permit such Democrats to compartmentalize, and not enough specifically in-state media that would cover them in such a way rather than based on national labels; in practice, then, any such Democrat will be unable to win federal office as a Democrat, and as ambitious Democrats stick with the all-Democratic party, the 62-38 pattern of today will reassert itself.

In the city, two Democratic factions are in theory possible, a centrist one and a leftist one. A left-wing solution is in theory favored by most of the city, which is happy to vote for federal politicians who promise universal health care, free university tuition, universal daycare, or more support for teachers, which more or less exist in Germany with a much less left-wing electorate. In practice, none of these is even semi-seriously attempted city- or statewide, and the machine views its role as, partly, gatekeeping left-wing organizations, which in turn have little competence to implement these, and often get sidetracked with other priorities (like teacher union opposition to phonics, or extracting more money from developers for neighborhood priorities).

Public transit is, in effect, caught in a crossfire of political incompetence. I think advocacy would be better if there were a persistently left-wing advocacy org and a persistently neoliberal one, but in practice, machine domination is such that the socialists and neoliberals often agree on a lot of reforms (for example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has become fairly YIMBY).

But even then, advocacy organizations should be using their outside voice more and avoiding flattering people who don’t deserve it. People in New York know that they are governed by failures. The lack of ideology means that the Republican nearly 40% of the state thinks they are governed by left-wing failures while the Democratic base thinks they are governed by centrist and Republicratic failures, but there’s widespread understanding that the government is inefficient. Advocates do not need to debase themselves in front of people who cost the region millions of dollars every day that they get up in the morning, go to work, and make bad decisions on transit investment and operations. There’s a long line of people who do flattery better than any advocate and will get listened to first by the hierarchy; the advocates’ advantage is not in flattery but in knowing the system better than the political appointees to the point of being able to make good proposals that the hierarchy is too incompetent to come up with or implement on its own.

Mass Transit on Orbital Boulevards

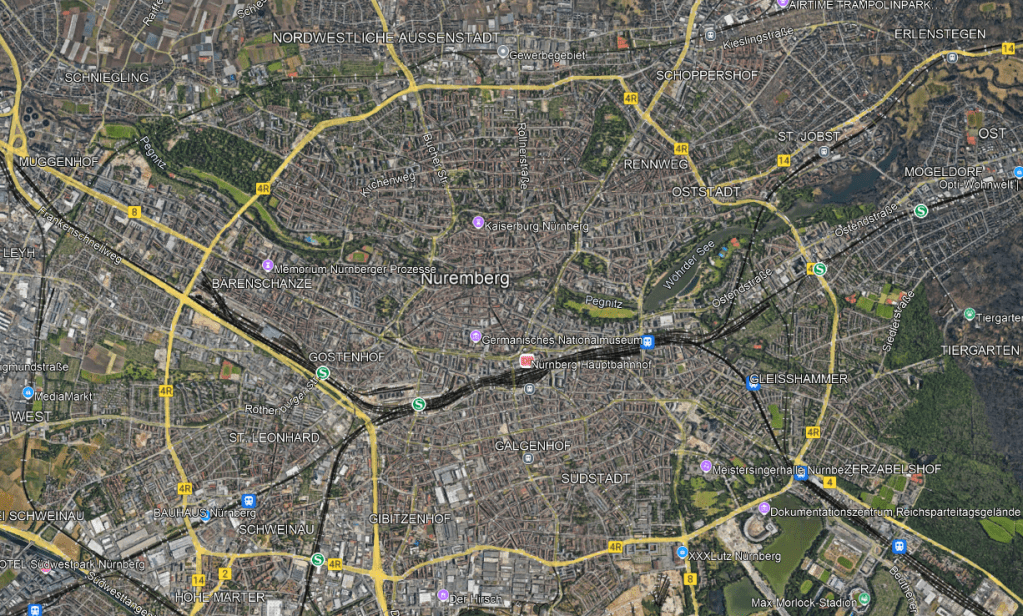

Herbert in comments has been asking me about urban rail on ring roads; Nuremberg has such a road with an active debate about what to do with it. Ring roads are attractive targets for urban rail, since they tend to be wide commercial throughfares. The one in Nuremberg is especially attractive for a tramway, or possibly a medium-capacity metro if one can be built cheaply; this is an artifact of its circumference (18 km) and the city’s size, reminiscent of the Boulevards of the Marshals hosting Paris Tramway Line 3, and the Cologne Gürtel, most of whose length has a tramway as well. Significantly closer-in ring roads, often delineating the medieval or Early Modern walls, are too small for this.

The history of such rings tends to be that they were built based on the extent of the industrial city. Cologne’s was built in the 19th century to connect growing bedroom communities to one another, where they previously only extended along the radial boulevards connecting them to the historic center. The Boulevards of the Marshals delineated the inner end of the Thiers wall from the 1840s; the Périphérique motorway is where the outer end had been. The upshot is that the construction standards are rather modern – for one, the roads are wide. Another upshot is that those roads are often destinations in and of themselves, so that radial rail lines have stops at them; the Métro has stops at every intersection with the Boulevards of the Marshals, generally named after the nearby gate (for example, I lived near Porte de Vincennes, due east along Métro Line 1).

This contrasts with older rings, including one visible on the screenshot above. Those older rings come from premodern city walls, and may not always have enough width to make it easy to build two tram lanes in the center or to do cheap cut-and-cover without disturbing the residences and businesses too much. Even when they do, they’re so close to the center the time savings from a ring at that radius are moderate. Jarrett Walker has long pointed out that people don’t travel in circles, giving the example of the Vienna Ring Road, which has two U-Bahn lines on different sections of it but no continuous ring, as a 5.3 km circle is too small to have viable long relatively linear sections. In Paris, old boulevards closer in than the ring forming Métro Lines 2 and 6 generally have Métro stops but it’s inconsistent, and there’s no coherent circular route to be built.

The modal question – tram or metro – is complicated by special elements of orbital boulevards, which sometimes cancel out, and can work differently in different cities.

In favor of light rail, there’s the issue of speed. Normally, the advantage of subways over tramways is that they’re faster. However, on a circumferential route, the importance of speed is reduced, since people are likely to only travel a relatively short arc, connecting between different radials or from a radial to an off-radial destination. What are more important than speed on such a route are easy transfers and high frequency. Easy transfers could go either way: if the radial routes are underground then it may be possible to construct underground interchanges with short walking, but it isn’t guaranteed, and if there are any difficulties, it’s better to keep it on the surface to shorten the walk time. This has in general been an argument used by pro-tram, anti-subway advocates in Germany, but on routes that rely on multiple transfers, potentially three-legged trips, it is a stronger argument than on a radial line from a suburban housing project to city center.

Frequency is especially delicate. It can be high regardless of mode. Driverless metros can reach 90-second headways or even less, but those are achieved on very busy lines, which need that frequency for throughput more than anything, like Lines 1 and 14 in Paris with their 85-second peak headways. In practice, an orbital tram, especially one in a smaller city than Paris, needs to be prioritizing frequency in order to shorten the trip, not to provide very high throughput, which means that the vehicles could be made smaller than full-size metros, to support frequency in the 3-6 minute range. This could be done at-grade with light rail, or underground with very small-profile metros akin to those used in small Italian cities like Brescia, or even some larger ones like Turin.

In favor of metro, there is the cost issue. The same factors that make speed less important and frequency more important also make it easier to build a metro. If the road is wide enough, which I think the one in Nuremberg is, then cut-and-cover is more feasible, reducing costs. The low required capacity permits intermediate-capacity metros (again, as in Brescia or some smaller French cities), with stations of perhaps 40-50 meters, reducing their construction costs. Nuremberg in particular has had some very low U-Bahn construction costs, so its ability to build an orbital U-Bahn should not be discounted. That said, even at Nuremberg costs – around $100 million/km in 2023 PPPs for U3 extensions – the extra speed provided by such a line, say half an hour to do a full orbit compared with a little less than an hour on a tram, may not be worth it necessarily, whereas such a speedup on a line that passengers may ride for 10 km unlinked would be extremely beneficial.