Category: Urban Design

Don’t Romanticize Traditional Cities that Never Existed

(I’m aware that I’ve been posting more slowly than usual; you’ll be rewarded with train stations soon.)

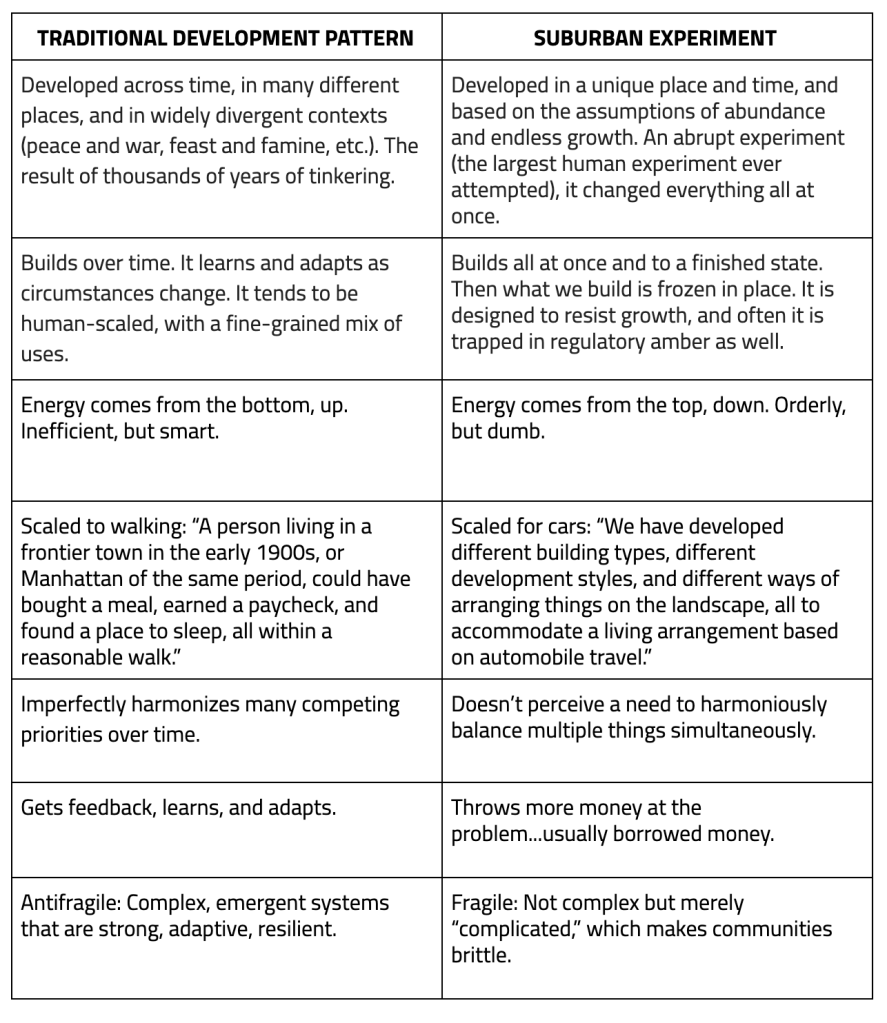

I saw a tweet by Strong Towns that compared traditional cities with the suburbs, and the wrongness of everything there reminded me of how much urbanists lie to themselves about what cities were like before cars. Strong Towns is more on the traditional urbanism side (to the point of rejecting urban rail on the grounds that it leads to non-gradual development), but a lot of what I’m critiquing here is, regrettably, commonly believed across the urbanist spectrum.

The basic problem with this comparison is that there was never such a thing as traditional urbanism. There are others; all of the claims in the comparison are false – for example, the line about “makes communities brittle” misses how little community empowerment cities had in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before zoning, and the line about top-down versus bottom-up energy misses how centralized coal and hydroelectric plants were at the turn of the century whereas left-voting NIMBY suburbs today are the most reliable place to find decentralized rooftop solar plants. But the fundamental problem is that Strong Town, and most urbanists, assume that there was a relatively fixed urban model around walkability, which cars came in and wrecked in the 20th century.

What’s true is that before mass motorization, people didn’t use cars to get around. But beyond that tautology, every principle of urban walkability was being violated in one pre-automobile urban typology or another.

Local commuting

Pre-automobile industrial cities were not 15-minute cities by any means. Marchetti’s constant of commuting goes back to at least the early 19th century; people in pre-automobile New York or London or Berlin commuted to a commercializing city center. This was to some extent understood in the second half of the 19th century: the purpose of rapid transit in New York, first steam els and then the subway, was to provide a fast enough commute so that the working class of the Lower East Side would get out of its tenements and into lower-density houses where they’d be turned from hyphenated Jews and Italians into proper Americans.

There has been a real change in that, in Gilded Age New York (and, I believe, in third-world cities today like Nairobi), people worked either locally or in city center. There was very little crosstown commuting, and so the Commissioners’ Plan for Manhattan in 1811 emphasized north-south commuting to Lower Manhattan, while private streetcar concessionaires likewise built routes to city center and rarely crosstown. Nor was there much long-distance travel except by the people who did work in city center: there were people who lived their entire lives in Brooklyn without visiting Manhattan, which became unthinkable by the early 20th century already. But this hardly makes Gilded Age Brooklyn a 15-minute city, any more than a modern suburb where most people do not visit city center out of fears of crime is anything but a suburb of the city, living off of the income generated by people who do commute in.

In truly premodern city, the situation depended on the time and place. Medieval European cities famously had little commuting – shopkeepers would live in the same building that housed their store, sleeping on an upper floor. But in Tang-era Chang’an, people did commute (my reference is the History of Imperial China series, no link, sorry). This is very far from the result of thousands of years of tinkering, when each time and place did something different before industrialization, and then went to yet another set of layouts after.

Local infrastructure

Pre-automobile industrial cities mixed top-down and bottom-up approaches, same as today. The grid plans favored in the United States, China, and the Roman Empire were more top-down than the unplanned street networks of most medieval and Early Modern European cities, each designed for a different cultural context. (In Imperial Rome much of the context was about following military manuals, for those cities that descend from forts.) In the medieval Muslim world, cities had cul-de-sacs long before cars, because this way each clan could have its own walled garden, so to speak.

Widely divergent contexts

Premodern cities developed in widely divergent contexts. Based on these contexts, they could look radically different. The comparison mentions war and peace; well, defensive walls were a fixture in many cities, and these mattered for their urban development. They were not nice strolls the way some embankments are today. There aren’t any good examples of walls in North America, but there are star forts, and they’re not usually pleasant walks – their purpose was to make the day of besieging troops as bad as possible, not to make tourists feel good about the city’s history. Medieval walls were completely different from star forts, and didn’t make for a walkable environment, either – in Paris I would routinely walk to the park and to the exterior of the Château de Vincennes, and while the park was pleasant, the castle has a moat and none of the street uses that activate a street, like retail or windows. The modern equivalents of such fixtures should be compared with prisons and modern military bases (some using the historic star forts), not touristy palaces.

Even the concept of city center is, as mentioned above on commuting, neither timeless (it didn’t exist in premodern Europe) nor a product of cars (it did exist in 19th-century America and Europe). Joel Garreau points out, either in Edge City or in some of the articles he’s written about the concept, that the traditional downtown was really only a fixture for a few generations, from the early 19th century to the middle of the 20th.

The issue of fragility

The entire comparison is grating, but smoehow the thing that bothers me most there is not the elementary errors, but the last point, about how traditional cities were antifragile for millennia before modern suburbia came in and wrecked them with debt.

This, to be very clear, is bullshit. Premodern cities could depopulate with one plague, famine, or war; these often co-occurred, such as when Louis XIV’s wars led to such food shortages that 10% of France’s population died in two famines spaced 15 years apart (put another way: France underwent a Reign of Terror’s worth of deaths every two weeks for a year and a half, and then a second for somewhat less than a year). In 1793, 10% of Philadelphia’s population died of yellow fever within the span of a few months. After repeated sacks and economic decline, Jaffa was abandoned in much of the Early Modern era.

Industrial cities generally do not undergo any of these things. (They can be subjected to genocide, like the Jews of Europe in the Holocaust, but that’s not at all about urbanism.) But that’s hardly a millennia-old tradition when it only goes back to about the middle of the 19th century, after the Great Hunger. In the UK, the Great Hunger affected rural areas like Ireland and Highland Scotland, but in a country that was at the time majority-rural – Britain would only flip to an urban majority in 1851 – it’s hardly a defense. Nor did the era after 1850 feature much stability in the cities; boom-and-bust cycles were common and the risk of unemployment and poverty was constant.

Urbanism for non-Tourists

There’s a common line among urbanists and advocates of car-free cities to the effect that all the nice places people go to for tourism are car-light, so why not have that at home? It’s usually phrased as “cities that people love” (for example, in Brent Toderian), but to that effect, mainly North American (or Australian) urbanists talk about how European cities are walkable, often in places where car use is rather high and it’s just the tourist ghetto that is walkable. Conversely, some of the most transit-oriented and dynamic cities in the developed world lack these features, or have them in rather unimportant places.

Normally, “Americans are wrong about Europe” is not that important in the grand scheme of things. The reason American cities with a handful of exceptions don’t have public transit isn’t that urbanist advocacy worries too much about pedestrianizing city center streets and too little about building subways to the rest of the city. Rather, the problem is the effect of tourism- and consumption-theoretic urbanism right here. It, of course, doesn’t come back from the United States – European urbanists don’t really follow American developments, which I’m reminded of every time a German activist on Mastodon or Reddit tries explaining metro construction costs to me. It’s an internal development, just one that is so parallel to how Americans analytically get Europe wrong that it’s worth discussing this in tandem.

The core of public transit

I wrote a blog post many years ago about what I called the in-between neighborhoods, and another after that. The two posts are rather Providence-centric – I lived there when I wrote the first post, in 2012 – but they describe something more general. The workhorses of public transit in healthy systems like New York’s or Berlin’s or Paris’s, or even barely-existing ones like Providence’s, are urban neighborhoods outside city center.

The definitions of both “urban” and “outside city center” are flexible, to be clear. In Providence, I was talking about the neighborhoods on what is now the R bus route, namely South Providence and the areas on North Main Street, plus some similar neighborhoods, including the East Side (the university neighborhood, the only one in Providence’s core that’s not poor) and Olneyville in the west. In larger, denser, more transit-oriented Berlin, those neighborhoods comprise the Wilhelmine Ring and thence stretch out well past the Ringbahn, sometimes even to city limits in those sectors where sufficient transit-oriented development has been built, and a single district like Neukölln may have more people than the entirety of Providence.

In Berlin, this can be seen in modal splits by borough; scroll down to the tables by borough, and go to page 45 of each PDF. The modal split does not at all peak in the center. Among the 12 boroughs, the one with the highest transit modal split for work trips is actually Marzahn-Hellersdorf, in deep East Berlin. The lowest car modal split is in the two centermost boroughs, Mitte and Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain, both with near-majorities for pedestrian and bike commutes – but the range of both of these modes is limited enough that it’s not supportable anywhere else in Berlin.

Nor is shrinking the city to the range of a bike going to help. Germany is full of cities of similar size to the combined total of Mitte and Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain; they have much higher car use, because what makes the center of Berlin work is the large concentration of jobs and other destinations brought about by the size of the city.

The same picture emerges in other transit cities. In Paris, the city itself is significant for the region’s public transit network, but its residents only comprise 30% of Francilien transit commuters, and even that figure should probably subtract out the outer areas of the city, which tourists don’t go to, like the entire northeast or the areas around and past the Boulevards of the Marshals. The city itself has much higher modal split than its suburbs, but that, again, depends on a thick network of jobs and other destinations that exist because of the dominance of the city as a commercial destination within a larger region.

Where tourists go

The in-between neighborhoods that drive the transit-oriented character of major cities are generally residential, or maybe mixed-use. Usually, they do not have tourist destinations. In Berlin, I advocate for tourists to visit Gropiusstadt and see its urbanism, but I get that people only do it if they’re especially interested in urban exploration. Instead, tourism clusters in city center; the museums are almost always in the center to the point that exceptions (like Balboa Park in San Diego) are notable, high-end hotels cluster in city center (the Los Angeles exception is again notable), and so on.

These tourism-oriented city centers often include pedestrianized street stretches. Berlin is rather atypical in Germany in not having such a stretch; in contrast, tourists can lose themselves in Marienplatz in Munich, or in various Altstadt areas of other cities, and forget that these cities have higher car use than Berlin, often much higher. For example, Leipzig’s car modal split for work trips is 47% (source, p. 13), higher than even Berlin’s highest-modal split borough, Spandau, which has 44% (Berlin overall is at 25%).

To be clear, Leipzig is, by most standards, fairly transit-oriented. Its tram network has healthy ridership, and its S-Bahn tunnel is a decent if imperfect compromise between the need to provide metro-like train service through the city and the need to provide long-distance regional rail to Halle and other independent cities in the region. But it should be more like Berlin and not the reverse.

Another feature of tourist cities is the premodern city core, with its charming very narrow streets. Berlin lacks such a core, and Paris only has a handful of such streets, mostly in the Latin Quarter. But Stockholm has an intact Early Modern core in Gamla Stan; it is for all intents and purposes a tourist ghetto, featuring retail catering to tourists and not much else. Stockholm is a very strong transit city with a monocentric core, but the core is not even at Gamla Stan, but to its north, north of T-Centralen, and thus the other tourist feature, the pedestrianized city center street with high-end retail, remains distinct from the premodern core.

Tellingly, these premodern cores exist even in thoroughly auto-oriented cities, ones with much weaker public transit than Leipzig. Italy supplies many examples of cities that were famously large in the Renaissance, and still have intact cores where one can visit the museums. A few years ago, Marco Chitti pointed out how Italian politicians, like foreign tourists, like taking photo-ops at farmers’ markets in small historic cities, while meanwhile, everyone in Italy does their shopping at suburban shopping centers offering far lower prices. To the tourist, Florence looks charming; to the resident, it is, in practice, a far more auto-oriented region than Stockholm or Berlin.

Why Commuters Prefer Origin to Destination Transfers

It’s an empirical observation that rail riders who are faced with a transfer are much more likely to make the trip if it’s near their home than near their destination. Reinhard Clever’s since-linkrotted work gives an example from Toronto, and American commuter rail rider behavior in general; I was discussing it from the earliest days of this blog. He points out that American and Canadian commuter rail riders drive long distances just to get to a cheaper or faster park-and-ride stations, but are reluctant to take the train if they have any transfer at the city center end.

This pattern is especially relevant as, due to continued job sprawl, American rail reformers keep looking for new markets for commuter rail to serve and set their eyes on commutes to the suburbs. Garrett Wollman is giving an example, in the context of the Agricultural Branch, a low-usage freight line linking to the Boston-Worcester commuter line that could be used for local passenger rail service. Garrett talks about the potential ridership of the line, counting people living near it and people working near it. And inadvertently, his post makes it clear why the pattern Clever saw in Toronto is as it is.

Residential and job sprawl

The issue at hand is that residential sprawl and job sprawl both require riders to spend some time connecting to the train. The more typical example of residential sprawl involves isotropic single-family density in a suburban region, with commuters driving to the train station to get on a train to city center; they could be parking there or being dropped off by family, but in either case, the interface to the train for them is in their own car.

Job sprawl is different. Garrett points out that there are 79,000 jobs within two miles of a potential station on the Ag Branch, within the range of corporate shuttles. With current development pattern, rail service on the branch could follow the best practices there are and I doubt it would get 5% of those workers as riders, for all of the following reasons:

- The corporate shuttle is a bus, with all the discomfort that implies; it usually is also restricted in hours even more than traditional North American commuter rail – the frequency on the LIRR or even Caltrain is low off-peak but the trains do run all day, whereas corporate shuttles have a tendency to only run at peak. There is no own-car interface involved.

- The traditional car-commuter train interface is to jobs in areas with traffic congestion and difficult parking. The jobs in the suburbs face neither constraint. Of note, Long Islanders working in Manhattan do transfer to the subway, because driving to the East Side to avoid the transfer from Penn Station is not a realistic option.

- The traditional car-commuter train interface is to jobs in a city center served from all directions by commuter rail. In contrast, the jobs in the suburbs are only served by commuter rail along a single axis. There is a fair amount of reverse-peak ridership from San Francisco to Silicon Valley jobs or from New York to White Plains and Stamford jobs, even if at far lower rates than the traditional peak direction – but most people working at a suburban job center live in another suburb, own a car, and either commute in a different direction from that of the train or don’t live and work close enough to a station that the car-train-shuttle trip is faster than an all-car trip.

Those features are immutable without further changes in urban design. Then there are other features that interact with the current timetables and fares. North American commuter rail has so many features designed to appeal to the type of person who drives everywhere and uses the train as a shuttle extending their car-oriented lifestyle into the city – premium fares, heavy marketing as different from normal public transit, poor integration with said normal public transit – that interface with one’s own car is especially valuable, and interface with public transit is especially unvalued.

And yet, it’s clearly possible to make it work. How?

How Europe makes it work

Commuter trains in Europe (nobody calls them regional rail here – that term is reserved for hourly long-range trains) get a lot of off-peak ridership and are not at all used exclusively by 9-to-5 commuters who drive for all other purposes. Some of this is to suburban job centers. How does this work, besides timetables and other operating practices that American reformers recognize as superior to what’s available in the US and Canada?

The primary answer is near-center jobs. Paris and La Défense have, between them, about 37% of the total jobs of Ile-de-France. Within the same land area, 100 km^2, both New York and Boston have a similar proportion of the jobs in their respective metro areas, about 35% each, as does San Francisco within the smaller definition of the metro area, excluding Silicon Valley. Ile-de-France’s work trip modal split is about 43%, metro New York’s is 33%, metro San Francisco’s is 17%, metro Boston’s is 12%.

So where Boston specifically fails is not so much office park jobs, such as those on Route 128, but near-center jobs. Its urban and suburban transit networks do a poor job of getting people to job centers like Longwood, the airport, Cambridge, and the Seaport. The same is true of San Francisco. New York’s network does a better but still mediocre job at connecting to Long Island City and Downtown Brooklyn, and a rather bad job at connecting to inner-suburban New Jersey jobs, but so many of those 35% jobs in the central 100 km^2 are in fact in the central 23 km^2 of the Manhattan core, and nearly half are in the central 4 km^2 comprising Midtown, that the poor service to the other 77 km^2 can be overlooked.

As far as commuter rail is concerned, the main difference in ridership between the main European networks – the Paris RER, the Berlin S-Bahn, and so on – and the American ones is how useful they are for plain urban service. Nearly all Berlin S-Bahn traffic is within the city, not the suburbs; the RER’s workhorse stations are mostly in dense inner suburbs that in most other countries would have been amalgamated into the city already.

To the extent that this relates to American commuter rail reforms, it’s about coverage within the city: multiple city stations, good (free, frequent) connections to local urban rail, high frequency all day to encourage urban travel (a train within the city that runs every half an hour might as well not run).

Suburban ridership is better here as well, but this piggybacks on very strong urban service, giving strong service from the suburbs to the city. Suburb-to-suburb commutes are done largely by car – Ile-de-France’s modal split is 43%, not 80%; there are fewer of them than in most of the US, but not fewer than in New York, Boston, or San Francisco.

But, well, Paris’s modal split is noticeably higher than the job share within the city – a job share that does include drivers. What gives?

Suburban transit-oriented development

TOD in the suburbs can create a pleasant enough rail commute that the modal split is respectable, if nothing like what is seen for jobs in Paris or Manhattan. However, for this to work, planners must eliminate the expression “corporate shuttle” from their lexicon.

Instead, suburban job sites must be placed right on top of the train station, or within walking distance along streets that are decently walkable. I can’t think of good Berlin examples – Berlin maintains high modal split through a strong center – but I can think of several Parisian ones: Marne-la-Vallée (including Disneyland), Noisy, Evry, Cergy. Those were often built simultaneously with greenfield suburban lines that were then connected to the RER, rather than on top of preexisting commuter lines.

They look nothing like American job sprawl. Here, for example, is Cergy:

There are parking garages visible near the train stations, but also a massing of mid-rise residential and commercial buildings.

But speaking of residential, the issue is that employers looking for sites to locate to have no real reason to build offices on top of most suburban train stations – the likeliest highest and best usage is residential. In the case of American TOD, even the secondary-urban centers, like Worcester, probably have much more demand for residential than commercial TOD within walking distance of the train station – employers who are willing to pay near-train station premium rent might as well pay the higher premium of locating within the primary city, where the commuter shed is much larger.

In effect, the suburban TOD model does not counter the traditional monocentric urban layout. It instead extends it to a much larger scale. In this schema, the entirety of the city, and not just its central few square kilometers, is the monocenter, served by different lines with many stations on them. Berlin is ahead of the curve by virtue of its having multiple close-by centers as a Cold War legacy, but Paris is similar (its highest-intensity commercial TOD is in La Défense and in in-city sites like Bercy, on top of former railyards attached to Gare de Lyon).

At no point does this model include destination-end transfers in the suburbs. In the city, it does: a single line cannot cover all urban job sites; but the transfer is within the rapid transit system. But in the suburbs, the jobs that are serviceable by public transportation are within walking distance of the station. Shuttles may exist, but are secondary, and job sites that require them are and will always be auto-centric.

The Origins of Los Angeles’s Car Culture and Weak Center

On Twitter, Armand Domalewski asks why Los Angeles is so much more auto-oriented than his city, San Francisco. Matt Yglesias responds that it’s because Los Angeles does not have a strong city center and San Francisco does. I am fairly certain that Matt is channeling a post I wrote about the subject 4.5 years ago (and insight by transit advocates that I don’t remember the source of, to the effect that the modal split for Downtown Los Angeles workers is a healthy 50%), looking at employment in these two cities’ central business districts as well as other comparison cases. In addition, Matt gives extra examples of how Los Angeles is unique in having prestige industries located outside city center: the movie studios are famously in Hollywood and not Downtown, and to that I’ll add that when I looked at high-end hotel locations in 2012, Los Angeles’s were all over the region and most concentrated on the Westside, which isn’t true of other big American coastal cities, even atypically job-sprawling Philadelphia. Because of my connection to this question, I’d like to inject some nuance.

The upshot is that Los Angeles’s car culture is clearly connected to its weak center. I wouldn’t even call it polycentric. Rather, employment there sprawls to small places, rarely even rising to the level of a recognizable edge city like Century City. It is weakly-centered, and this favors cars over public transit – public transit lives off of high-capacity, high-frequency connections, favoring places with high population density (which Los Angeles has) and high job density (which it does not), while cars prefer the opposite because excessive density with cars leads to traffic jams. However, historically, best I can tell, the weak center and the cars co-evolved – I don’t think Los Angeles was atypically weakly-centered on the eve of mass motorization, and in fact every city for which I can find such information, even model transit cities, has gotten steadily job-sprawlier in the last few generations.

How is Los Angeles weakly centered?

There are a number of ways of measuring city center dominance. My metric is the share of metro area employment that is in the central 100 km^2; some gerrymandering and water-hopping is permitted, but the 100 km^2 blob should still be a recognizable central blob rather than many disconnected islands. This is not because this is the best metric, but because my information about France and Canada is less granular than for the United States, and 100 km^2 lets me compare American cities with Vancouver and with the combination of Paris and La Défense; my data on Tokyo is of comparable granularity to Paris and this lets me pick out Central Tokyo plus some adjacent wards like Shinjuku.

As a warning, the fixed size of the central blob means that the proportion should be degressive in city size, which I notice when I compare auto-centric American metro areas of different sizes. It should also be higher all things considered in the United States, where I draw blobs on OnTheMap to capture as many jobs as possible without the blob looking like it has tendrils, than in the foreign comparisons.

I gave many examples in a Twitter thread from 2019, though not Los Angeles. Doing the same exercise for Los Angeles with 2019 data gives 1.6 million jobs in a 500 km^2 blob stretching as far as Culver City, UCLA, Downtown Burbank, and Downtown Pasadena; a 100 km^2 blob gerrymandered to just include Hollywood, West Hollywood, and Century City, none of which can reasonably be called city center, is already down to 820,000, where the roughly same-area city of San Francisco is 770,000, and more like 900,000 when taking its central 50 km^2 plus those of Oakland and Berkeley. A circle of area 100 km^2 centered on Vermont/Wilshire to include all of Downtown plus Hollywood is down to 620,000. This compares with a total of 6.5 million jobs in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, and 8.3 million including Ventura County and the Inland Empire.

The upshot is that Downtown Los Angeles is pretty big, but not relative to the size of the metro area it’s in. On an honest definition of the central business district, it is smaller in absolute job count than Downtown San Francisco, Boston (which has around 830,000), Washington (around 700,000), or Chicago (1 million), let alone New York (around 3 million) or Paris (2 million in the city and the communes comprising La Défense).

Nor are the secondary centers in Los Angeles substantial enough to make it polycentric. Downtown Burbank has around 20,000 jobs, Downtown Glendale around 50,000, Downtown Pasadena including Caltech 67,000, Century City (included in the less honest central 100 km^2) 54,000, UCLA 74,000, El Segundo 55,000, LAX 48,000, Culver City around 20,000, Downtown Long Beach around 35,000. New York, in contrast, has Downtown Newark around 60,000, the Jersey City and Hoboken waterfront around 80,000, Long Island City around 100,000, Downtown Brooklyn around 100,000 as well, Flushing 45,000. Morningside Heights has 42,000 jobs in 1 km^2, a job density that I don’t think any of Los Angeles’s secondary centers hits, and the neighborhood is not at all a pure job center. No: Los Angeles just has a weak center.

I bring up Paris as a comparison because there’s a myth on both sides of the Atlantic, peddled by European critical urbanists who think tall buildings are immoral and by American tourists whose experience of Europe is entirely within walking distance of their city center hotels, that European city centers are less dominant than American ones. But Paris has, within the same area, comfortably more jobs than the centers of Los Angeles and Chicago combined; its central-100-km^2 job share is somewhat higher than New York’s (though probably only by enough to countermand the degressivity of this measure).

Was Los Angeles always like this?

I don’t think so. My knowledge of Los Angeles history is imperfect; the closest connection I have with it is that my partner is developing a narrative video game set in 1920s Hollywood, intended to be a realistic depiction of that era. But Los Angeles as I understand it was not especially polycentric, historically.

Historically polycentric regions exist, and tend to have weaker public transit than similar-size monocentric ones. The Ruhr has several centers, each with decent urban rail within the core city and high car usage elsewhere; Upper Silesia is far more auto-oriented than similar-size metropolitan Warsaw; Randstad has rather low urban rail ridership as people bike (in the main cities) or drive (in the suburbs). All three are truly historically polycentric, having developed as different city cores merged into one metro area as mechanized transportation raised people’s commute range, and in the case of the first two, much of this history involves different coal mining sites, each its own city.

Los Angeles doesn’t really have this history. The city had a slight majority of the county’s population in 1920 (577,000/936,000) and 1930 (1,238,000/2,208,000), only falling below half in the 1940s – and in the 1920s the city was already notable for its high use of cars. The other four counties in the metro area were more or less irrelevant then – in 1920 they totaled 244,000 people, rising to 389,000 by 1930, actually less than the city. Glendale grew from 14,000 to 63,000, Long Beach from 56,000 to 142,000, Santa Ana from 15,000 to 30,000; other suburbs that are now among the largest in the country either were insignificant (Anaheim had 11,000 people in 1930) or didn’t exist (Irvine had 10,000 people in 1970).

Los Angeles did annex San Fernando Valley early, but there wasn’t much urban development there in the 1920s; Burbank, entirely contained within that region, had 17,000 people in 1930, and San Fernando had 8,000. There was a lot of suburbanization in this period, but it did not predate car culture.

This is not at all how a polycentric region’s demographic history looks – in the Rhine-Ruhr, in 1900, Dortmund and both cities that would later merge to form Wuppertal had 150,000 people, Essen had just over 100,000 and would annex to over 200,000 within five years, Duisburg and Bochum both had just less than 100,000 and would soon cross that mark, Cologne had 370,000 people.

The region had an oil-based economy at the time – in the early 20th century the center of the American oil industry was still California and not Texas – but evidently, development centered on Los Angeles and to a small extent Long Beach (in 1930 having about the same ratio of population to Los Angeles’s that the combination of Jersey City and Newark did to New York’s). The same can be said of the various beach resorts that were booming in that era – the largest, Santa Monica, had 37,000 people in 1930, 3% of the population of Los Angeles, at which point Yonkers had 2% of New York’s population.

Boomtown infrastructure

While Los Angeles did not have a polycentric history in the 1920s, it did have a noted car culture. I believe that this is the result of boomtown dynamics, visible in many places that grow suddenly, like Detroit in the same era (in the 2010s, metro Detroit had a transit modal split of about 1%, the lowest among the largest American metro areas, even less than Dallas and Houston). Infrastructure takes time and coordination to build. In a growing region, infrastructure is always a little bit behind population growth, and in a boomtown, it is far behind – who knows if the boom will last? Texas is having this issue with flood control right now, and that’s with far less growth than that of Southern California in the first half of the 20th century.

The upshot is that in a very wealthy boomtown like 1920s Los Angeles (California ranking as the fourth richest state in 1929 and third richest in 1950), people have a lot of disposable income and not much public infrastructure. This leads to consumer spending – hence, cars. It takes long-term planning to convert such a city into a transit city, and this was not done in Los Angeles; plans to build a subway-surface tunnel for the Red Cars did not materialize, and the streetcars were not really competitive with cars on speed. Compounding the problems, the Red Cars were never profitable, in an era when public transit was expected to pay for itself; they were a loss leader for real estate development by owner Henry Huntington, and by the 1920s the land had already been sold at a profit.

Then came the war, and the same issue of private wealth without infrastructure loomed even more. California boomed during the war, thanks to war industries; there was new suburban development in areas with no streetcar service, with people carpooling to work or taking the bus as part of the national scheme to save fuel for the war effort. Transit maintenance was deferred throughout the country (as well as in Canada); after the war, Los Angeles had a massive population of people with very high disposable income, whose alternative to the car was either streetcars that were falling apart or buses that were even slower and had even worse ride quality.

Everywhere in the United States at the time, bustitution led to falling ridership per Ed Tennyson’s since-link-rotted TRB paper on the subject, even net of speed – Tennyson estimates based on postwar streetcar removal and later light rail construction that rail by itself gets 34-43% more ridership than bus service net of speed, and in both the bustitution and light rail eras the trains were also faster than the buses. But the older million-plus cities in the United States at the time had their subways to fall back on. Los Angeles had grown up too quickly and didn’t have one; neither did Detroit, which has a broadly Rust Belt economic and social history but a much more car-oriented transportation history.

The sort of long-term planning that produced transit revival did happen in the Western United States and Canada, elsewhere. In the 1970s, Western American and Canadian cities invented what is now standard light rail in both countries, often out of a deliberate desire not to be Los Angeles, at the time infamous for its smog; those cities have had more success with transit revival and transit-oriented development, especially Vancouver with its SkyTrain metro and aggressive high-rise residential and commercial transit-oriented development. But in the 1920s-40s, there was no such political counter to automobile dominance. Los Angeles did start building urban rail in the 1980s, but not at the necessary scale, and with ridiculously low levels of transit-oriented development: in the 2010s, after the economy recovered from the Great Recession, the 10 million strong county approved a hair more than 20,000 housing units annually, slightly less than the 2.5 million strong Metro Vancouver region.

Co-evolution of transportation and development

Los Angeles was not very decentralized in the first half of the 20th century. It had lower residential density, but none of today’s edge cities and smaller sub-centers really existed then, with only a handful of exceptions like Long Beach. By today’s standards, every American city was very centralized, with people generally working either in their home neighborhood or in city center. The city did have high car ownership for the era, and this encouraged freeway construction after the war, but the weak central business district came later.

Rather, what has happened since the war is a co-evolution of car-oriented transportation and weakly-centered job geography. Cars got stuck in traffic jams trying to get to city center, so business and local elites banded together to build an edge city closer to where management lived, first Miracle Mile and then Century City; Detroit similarly had New Center, where General Motors headquartered starting 1923. New York underwent the same process as businesses looked for excuses to move closer to the CEO’s home in the favored quarter (IBM in Armonk, General Electric in Fairfield), but the existence of the subway meant that there was still demand for ever more city center skyscrapers, even as city residents of means fled to the suburbs.

This story of co-evolution is not purely American. I keep going back to Paul Barter’s thesis, which portrays the urban layout in his example cities in East and Southeast Asia as starting from a similar point in the middle of the 20th century. Density was high throughout, and central sectors in Southeast Asia were ethnically segregated, with a Chinatown, an Indian area, a low-density Western colonial sector, and so on. The divergence happened in the second half of the 20th century, Singapore choosing to be a transit city and Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok choosing to be car-oriented cities. I don’t have job data for these cities, but my impression as a visitor (and former Singapore resident) is that Singapore has a clear central office district and Bangkok has a hodgepodge of skyscrapers with no real structure to where they go within the central areas.

So yes, Los Angeles’s weak center is making it difficult to expand public transportation there now and get high ridership out of it; boosting the region’s transit-oriented development rate to that of Vancouver would help, but Los Angeles is far more decentralized and auto-oriented than Vancouver was in the 1990s. But the historic sequence is not first polycentrism and then automobility, unlike in Upper Silesia or the Ruhr. Rather, a weak center (never true polycentricity) and automobility co-evolved, reinforcing each other to this day – it’s hard to get ridership out of urban rail expansions since city center is so weak, so people drive, so jobs locate where there’s less traffic and avoid Downtown Los Angeles.

Edge Cities With and Without Historic Cores

An edge city is a dense, auto-oriented job center arising from nearby suburban areas, usually without top-down planning. The office parks of Silicon Valley are one such example: the area had a surplus of land and gradually became the core of the American tech industry. In American urbanism, Tysons in Virginia is a common archetype: the area was a minor crossroads until the Capital Beltway made it unusually accessible by car, providing extensive auto-oriented density with little historic core.

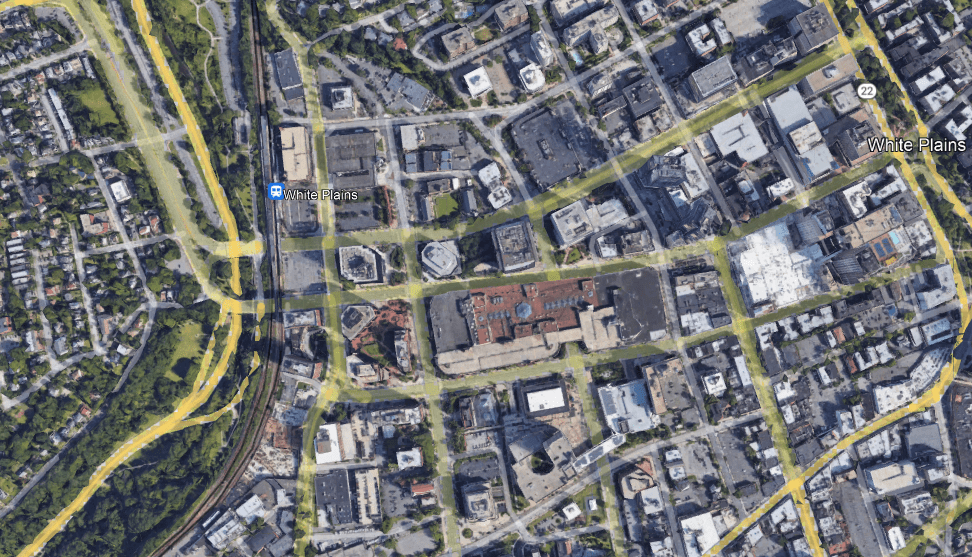

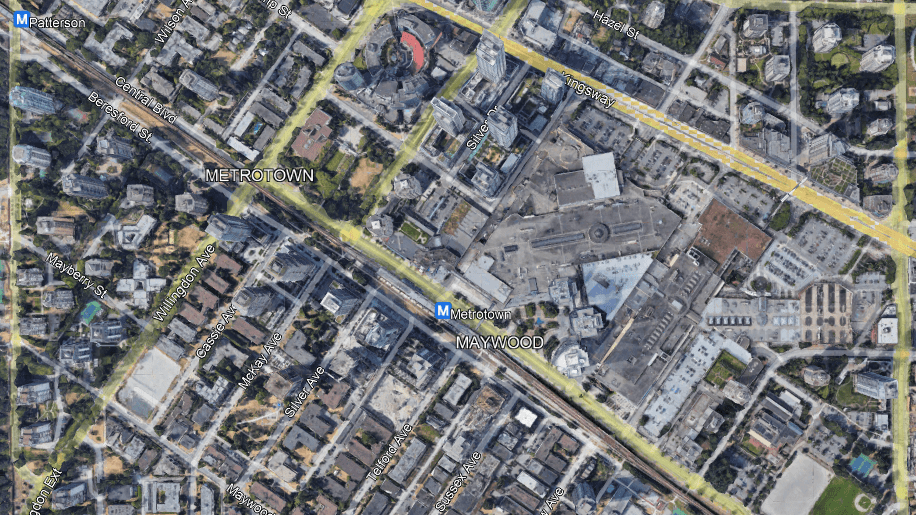

But there’s a peculiarity, I think mainly in the suburbs of New York. Unlike archetypal edge cities like Silicon Valley, Tysons, Century City in Los Angeles, or Route 128 north of Boston, some of the edge cities of New York are based on historic cores. Those include White Plains and Stamford, which have had booms in high-end jobs in the last 50 years due to job sprawl, but also Mineola, Tarrytown, and even New Brunswick and Morristown.

The upshot is that it’s much easier to connect these edge cities to public transportation than is typical. In Boston, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure out good last mile connections from commuter rail stations. Getting buses to connect outlying residential areas and shopping centers to town center stations is not too hard, but then Route 128 is completely unviable without some major redesign of its road network: the office parks front the freeway in a way that makes it impossible to run buses except dedicated shuttles from one office park to the station, which could never be frequent enough for all-day service. Tysons is investing enormous effort in sprawl repair, which only works because the Washington Metro could be extended there with multiple stations. Far and away, these edge cities are the most difficult case for transit revival for major employment centers.

And in New York, because so much edge city activity is close to historic cores, this is far easier. Stamford and White Plains already have nontrivial if very small transit usage among their workers, usually reverse-commuters who live in New York and take Metro-North. Mineola could too if the LIRR ran reverse-peak service, but it’s about to start doing so. Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow could be transit-accessible. The New Jersey edge cities are harder – Edison and Woodbridge have lower job density than Downtown Stamford and Downtown White Plains – but there are some office parks that could be made walkable from the train stations.

I don’t know what the history of this peculiar feature is. White Plains and Mineola are both county seats and accreted jobs based on their status as early urban centers in regions that boomed with suburban sprawl in the middle of the 20th century. Tarrytown happened to be the landfall of the Tappan Zee Bridge. Perhaps this is what let them develop into edge cities even while having a much older urban history than Tysons (a decidedly non-urban crossroads until the Beltway was built), Route 128, or Silicon Valley (where San Jose was a latecomer to the tech industry).

What’s true is that all of these edge cities, while fairly close to train stations, are auto-oriented. They’re transit-adjacent but not transit-oriented, in the following ways:

- The high-rise office buildings are within walking distance to the train station, but not with a neat density gradient in which the highest development intensity is nearest the station.

- The land use at the stations is parking garages for the use of commuters who drive to the station and use the train as a shuttle from a parking lot to Manhattan, rather than as public transportation the way subway riders do.

- The streets are fairly hostile to pedestrians, featuring fast car traffic and difficult crossing, without any of the walkability features that city centers have developed in the last 50 years.

The street changes required are fairly subtle. Let us compare White Plains with Metrotown, both image grabs taken from the same altitude:

These are both edge cities featuring a train station, big buildings, and wide roads. But in Metrotown, the big buildings are next to the train station, and the flat-looking building to its north is the third-largest shopping mall in Canada. The parking goes behind the buildings, with some lots adjoining Kingsway, which has a frequent trolleybus (line 19) but is secondary as a transportation artery to SkyTrain. Farther away, the residential density remains high, with many high-rises in the typical thin-and-tall style of Vancouver. In contrast, in White Plains, one side of the station is a freeway with low-density residential development behind it, and the other is parking garages with office buildings behind them instead of the reverse.

The work required to fix this situation is not extensive. Parking must be removed and replaced with tall buildings, which can be commercial or residential depending on demand. This can be done as part of a transit-first strategy at the municipal level, but can also be compelled top-down if the city objects, since the MTA (and other Northeastern state agencies) has preemption power over local zoning on land it owns, including parking lots and garages.

On the transit side, the usual reforms for improvements in suburban trains and buses would automatically make this viable: high local frequency, integrated bus-rail timetables (to replace the lost parking), integrated fares, etc. The primary target for such reforms is completely different – it’s urban and inner-suburban rail riders – but the beauty of the S-Bahn or RER concept is that it scales well for extending the same high quality of service to the suburbs.

The Four Quadrants of Cities for Transit Revival

Cities that wish to improve their public transportation access and usage are in a bind. Unless they’re already very transit-oriented, they have not only an entrenched economic elite that drives (for example, small business owners almost universally drive), but also have a physical layout that isn’t easy to retrofit even if there is political consensus for modal shift. Thus, to shift travel away from cars, new interventions are needed. Here, there is a distinction between old and new cities. Old cities usually have cores that can be made transit-oriented relatively easily; new cities have demand for new growth, which can be channeled into transit-oriented development. Thus, usually, in both kinds of cities, a considerably degree of modal shift is in fact possible.

However, it’s perhaps best to treat the features of old and new cities separately. The features of old cities that make transit revival possible, that is the presence of a historic core, and those of new cities, that is demand for future growth, are not in perfect negative correlation. In fact, I’m not sure they consistently have negative correlation at all. So this is really a two-by-two diagram, producing four quadrants of potential transit cities.

Old cities

The history of public transportation is one of decline in the second half of the 20th century in places that were already rich then; newly-industrialized countries often have different histories. The upshot is that an old auto-oriented place must have been a sizable city before the decline of mass transit, giving it a large core to work from. This core is typically fairly walkable and dense, so transit revival would start from there.

The most successful examples I know of involve the restoration of historic railroads as modern regional lines. Germany is full of small towns that have done so; Hans-Joachim Zierke has some examples of low-cost restoration of regional lines. Overall, Germany writ large must be viewed as such an example: while German economic growth is healthy, population growth is anemic, and the gradual increase in the modal split for public transportation here must be viewed as more intensive reuse of a historic national rail network, anchored by tens of small city cores.

At the level of a metropolitan area, the best candidates for such a revival are similarly old places; in North America, the best I can think of for this are Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago. Americans don’t perceive any of the three as especially auto-oriented, but their modal splits are comparable to those of small French cities. But in a way, they show one way forward. If there’s a walkable, transit-oriented core, then it may be attractive for people to live near city center; in those three cities it’s also possible to live farther away and commute by subway, but in smaller ones (say, smaller New England cities), the subway is not available but conversely it’s usually affordable to live within walking distance of the historic city center. This creates a New Left-flavored transit revival in that it begins with the dense city center as a locus of consumption, and only then, as a critical mass of people lives there, as a place that it’s worth building new urban rail to.

New cities

Usually, if a city has a lot of recent growth from the era in which it has become taken for granted that mobility is by car, then it should have demand for further growth in the future. This demand can be planned around growth zones with a combination of higher residential density and higher job density near rail corridors. The best time to do transit-oriented development is before auto-oriented development patterns even set in.

There are multiple North American examples of how this works. The best is Vancouver, a metropolitan area that has gone from 560,000 people in the 1951 census to 2.6 million in the 2021 census. Ordinarily, one should expect such a region to be entirely auto-oriented, as most American cities with almost entirely postwar growth are; but in 2016, the last census before corona, it had a 20% work trip modal split, and that was before the Evergreen extension opened.

Vancouver has achieved this by using its strong demand for growth to build a high-rise city center, with office towers in the very center and residential ones ringing it, as well as high-density residential neighborhoods next to the Expo Line stations. The biggest suburbs of Vancouver have followed the same plan: Burnaby built an entirely new city center at Metrotown in conjunction with the Expo Line, and even more auto-oriented Surrey has built up Whalley, at the current outer terminal of the line, as one of its main city centers. Housing growth in the region is rapid; YIMBY advocacy calls for more, but the main focus isn’t on broad development (since this already happens) but on permitting more housing in recalcitrant rich areas, led by the West Side, which will soon have its Broadway extension of the Millennium Line.

Less certain but still interesting examples of the same principle are Calgary, Seattle, and Washington. Calgary, a low-density city, planned its growth around the C-Train, and built a high-rise city center, limiting job sprawl even as residential sprawl is extensive; Seattle and the Virginia-side suburbs of Washington have permitted extensive infill housing and this has helped their urban rail systems achieve high ridership by American standards, Seattle even overtaking Philadelphia’s modal split.

The four quadrants

The above contrast of old and new cities misses cities that have positive features of both – or neither. The cities with both positive features have the easiest time improving their public transportation systems, and many have never been truly auto-oriented, such as New York or Berlin, to the point that they’re not the best examples to use for how a more auto-oriented city can redevelop as a transit city.

In North America, the best example of both is San Francisco, which simultaneously is an old city with a high-density core and a place with immense demand for growth fueled by the tech industry. The third-generation tech firms – those founded from the mid-2000s onward (Facebook is in a way the last second-generation firm, which generation began with Apple and Microsoft) – have generally headquartered in the city and not in Silicon Valley. Twitter, Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Dropbox, and Slack are all in the city, and the traditional central business district has expanded to South of Market to accommodate. This is really a combination of the consumption-oriented old-city model, as growing numbers of employees of older second-generation firms chose to live in the city and reverse-commute to Silicon Valley, and the growth-oriented new-city model. Not for nothing, the narrower metropolitan statistical area of San Francisco (without Silicon Valley) reached a modal split of 17% just before corona, the second highest in the United States, with healthy projections for growth.

But then there is the other quadrant, comprising cities that have neither the positive features of old cities nor those of new cities. To be in this quadrant, a city must not be so old as to have a large historic core or an extensive legacy rail network that can be revived, but also be too poor and stagnant to generate new growth demand. Such a city therefore must have grown in a fairly narrow period of time in the early- to mid-20th century. The best example I can think of is Detroit. The consumption-centric model of old city growth can work even there, but it can’t scale well, since there’s not enough of a core compared with the current extent of the population to build out of.

Stop Imitating the High Line

I streamed a longer version of this on Twitch on Tuesday, but the recording cut out, so instead of uploading to YouTube as a vlog, I’m summarizing it here

Manhattan has an attractive, amply-used park in the Meatpacking District, called the High Line. Here it is, just west of 10th Avenue:

It was originally a freight rail branch of the New York Central, running down the West Side of Manhattan to complement the railroad’s main line to Grand Central, currently the Harlem Line of Metro-North. As such, it was a narrow el with little direct interface with the neighborhood, unlike the rapid transit els like that on Ninth Avenue. The freight line was not useful for long: the twin inventions of trucking and electrification led to the deurbanization of manufacturing to land-intensive, single-story big box-style structures. Thus, for decades, it lay unused. As late as 2007, railfans were dreaming about reactivating it for passenger rail use, but it was already being converted to a park, opening in 2009. The High Line park is a successful addition to the neighborhood, and has spawned poor attempt at imitation, like the Low Line (an underground rapid transit terminal since bypassed by the subway), the Queensway (a similar disused line in Central Queens), and some plans in Jersey City. So what makes the High Line so good?

- The neighborhood, as can be seen above in the picture, has little park space. The tower-in-a-park housing visible to the east of the High Line, Chelsea-Elliott Houses, has some greenery but it’s not useful as a neighborhood park. The little greenery to the west is on the wrong side of 12th Avenue, a remnant of the West Side Highway that is not safe for pedestrians to cross, car traffic is so fast and heavy. Thus, it provides a service that the neighborhood previously did not have.

- The area has very high density, both residential and commercial. Chelsea is a dense residential neighborhood, but at both ends of the line there is extensive commercial development. Off-screen just to the south, bounded by Eighth, Ninth, 15th, and 16th, is Google’s building in New York, with more floor area than the Empire State Building and almost as much as One World Trade Center. Off-screen just to the north is the Hudson Yards development, which was conceived simultaneously with the High Line. This guarantees extensive foot traffic through the park.

- The linear park is embedded in a transit-rich street grid. Getting on at one end and off at the other is not much of a detour to the pedestrian tourist, or to anyone with access to the subway near both ends, making it a convenient urban trail.

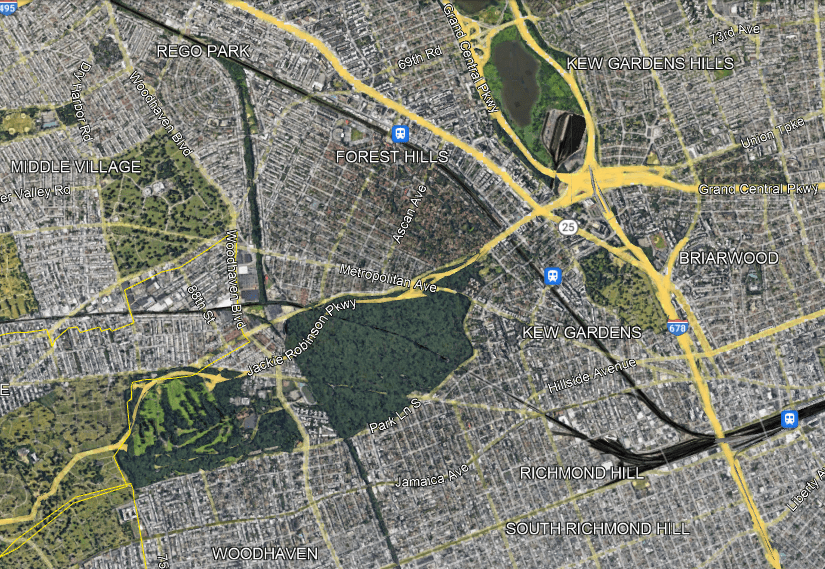

These three conditions are not common, and trying to replicate the same linear park in their absence is unlikely to produce good results. For example, consider the Rockaway Cutoff, or Rockaway Beach Branch:

The Cutoff has two competing proposals for what to do with this disused LIRR branch: the Queenslink, aiming to convert it to a rapid transit branch (connecting to the subway, not the LIRR), and the Queensway, aiming to convert it to a linear park. The Queenslink proposal is somewhat awkward (which doesn’t mean it’s bad), but the Queensway one is completely drunk. Look at the satellite photo above and compare to that of the High Line:

- The area is full of greenery and recreation already, easily accessible from adjoining areas. Moreover, many residents live in houses with backyards.

- The density is moderate at the ends (Forest Hills and Woodhaven) and fairly low in between, with all these parks, cemeteries, and neighborhoods of single-family houses and missing middle density. Thus, local usage is unlikely to be high. Nor is this area anyone’s destination – there are some jobs at the northern margin of the area along Queens Boulevard (the wide road signed as Route 25 just north of the LIRR) but even then the main job concentrations in Queens are elsewhere.

- There is no real reason someone should use this as a hiking trail unless they want to hike it twice, one way and then back. The nearest viable parallel transit route, Woodhaven, is a bus rather than a subway.

The idea of a park is always enticing to local neighborhood NIMBYs. It’s land use that only they get to have, designed to be useless to outsiders; it is also at most marginally useful to neighborhood residents, but neighborhood politics is petty and centers exclusion of others rather than the actual benefits to residents, most of whom either don’t know their self-appointed neighborhood advocates or quietly loathe them and think of them as Karens and Beckies. Moreover, the neighborhood residents don’t pay for this – it’s a city project, a great opportunity to hog at the trough of other people’s money. Not for nothing, the Queensway website talks about how this is a community-supported solution, a good indication that it is a total waste of money.

But in reality, this is not going to be a useful park. The first park in a neighborhood is nice. The second can be, too. The fifth is just fallow land that should be used for something more productive, which can be housing, retail, or in this case a transportation artery for other people (since there aren’t enough people within walking distance of a trail to justify purely local use). The city should push back against neighborhood boosters who think that what worked in the Manhattan core will work in their explicitly anti-Manhattan areas, and preserve the right-of-way for future subway or commuter rail expansion.

Quick Note on Los Angeles and Chicago Density and Modal Split

A long-running conundrum in American urbanism is that the urban area with the highest population density is Los Angeles, rather than New York. Los Angeles is extremely auto-oriented, with a commute modal split that’s only 5% public transit, same as the US average, and doesn’t feel dense the way New York or even Washington or Chicago or Boston is. In the last 15 years there have been some attempts to get around this, chiefly the notion of weighted or perceived density, which divides the region into small cells (such as census tracts) and averaged their density weighted by population and not area. However, even then, Los Angeles near-ties San Francisco for second densest in the US, New York being by far the densest; curiously, already in 2008, Chris Bradford pointed out that for American metro areas, the transit modal split was more strongly correlated with the ratio of weighted to standard density than with absolute weighted density.

DW Rowlands at Brookings steps into this debate by talking more explicitly about where the density is. She uses slightly different definitions of density, so that by the standard measure Los Angeles is second to New York, but this doesn’t change the independent variable enough to matter: Los Angeles’s non-car commute modal split still underperforms any measure of density. Instead of looking at population density, she looks at the question of activity centers. Those centers are a way to formalize what I tried to do informally by trying to define central business districts, or perhaps my attempts to draw 100 km^2 city centers and count the job share there (100 km^2 is because my French data is so coarse it’s the most convenient for comparisons to Paris and La Défense).

By Rowlands’ more formal definition, Los Angeles is notably weaker-centered than comparanda like Boston and Washington. Conversely, while I think of Los Angeles as not having any mass transit because I compare it with other large cities, even just large American cities, Brookings compares the region with all American metropolitan areas, and there, Los Angeles overperforms the median – the US-wide 5% modal split includes New York in the average so right off the bat the non-New York average is around 3%, and this falls further when one throws away secondary transit cities like Washington as well. So Los Angeles performs fairly close to what one would expect from activity center density.

But curiously, Chicago registers as weaker-centered than Los Angeles. I suspect this is an issue of different definitions of activity centers. Chicago’s urban layout is such that a majority of Loop-bound commutes are done by rail and a supermajority of all other commutes are done by car; the overall activity center density matters less than the raw share of jobs that are in a narrow city center. Normally, the two measures – activity center density and central business district share of jobs – correlate: Los Angeles has by all accounts a weak center – the central 100 km^2, which include decidedly residential Westside areas, have around 700,000 jobs, and this weakness exists at all levels. Chicago is different: its 100 km^2 blob is uninspiring, but at the scale of the Loop, the job density is very high – it’s just that outside the Loop, there’s very little centralization.

Meme Weeding: Rich West, Poor East

There’s a common line in global history – I think it’s popularized through Eric Hobsbawm – that there is a universal east-west divide in temperate latitude cities. The idea is that the west side of those cities is consistently richer than the east side and has been continuously since industrialization, because prevailing winds are westerly and so rich people moved west to be upwind of industrial pollution. I saw this repeated on Twitter just now and would like to push back. Some cities have this pattern, some don’t, some even have the opposite pattern. Among cities the casual urbanist reader is likely to be familiar with, about the only one where this is true is Paris.

London

London famously has a rich west and poor east. I think this is why the line positing this directional pattern as universal is so common. Unfortunately, the origin of this pattern is too recent to be about prevailing winds.

In an early example of data visualization, Charles Booth made a block by block map of London in 1889, colored by social class, with a narrative description of each neighborhood. The maps indeed show the expected directionality, but with far more nuance. The major streets were middle-class even on the East End: Mile End Road was lined with middle-class homes, hardly what one would expect based on pollution. The poverty was on back alleys. South London exhibited the same pattern: middle-class major throughfares, back alleys with exactly the kind of poverty Victorian England was infamous for. West London was different – most of it was well-off, either middle-class or wealthier than that – but even there one can find the occasional slum.

East London in truth had a lot of working poor because it had a lot of working-class jobs, thanks to its proximity to the docks, which were east of the City because ports have been moving downriver for centuries with the increase in ship size. Those working poor did not always have consistent work and therefore some slipped into non-working poverty. The rich clustered in enclaves away from the poverty and those happened to be in the west, some predating any kind of industrialization. Over time the horizontal segregation intensified, as slums were likelier to be redeveloped (i.e. evicted) in higher-property value areas near wealth, and the pattern diffused to the broader east-west one of today.

Berlin

Berlin has a rich west and poor east – but this is a Cold War artifact of when West Berlin was richer than East Berlin, and the easternmost neighborhoods of the West were poor because they were near the Wall (thus, half their walk radius was behind the Iron Curtain) and far from City West jobs.

Before WW2, the pattern was different. West of city center, Charlottenburg was pretty well-off – but so was Friedrichshain, to the east. The sharpest division in Berlin was as in London, often within the same apartment building, which would house tens of apartments: well-off people lived facing the street, while the poor lived in apartments facing internal courtyards, with worse lighting and no vegetation in sight.

Tokyo

Tokyo has a similar east-west directionality as London, but with its own set of nuances. This should not be too surprising – it’s at 35 degrees north, too far south for the westerlies of Northern Europe; the winds change and are most commonly southerly there. The directionality in Tokyo is more about the opposition between uphill Yamanote and sea-level Shitamachi (the Yamanote Line is so named because the neighborhoods it passes through – Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, and Shibuya – formed the old core of Yamanote).

What’s more, the old Yamanote-Shitamachi pattern is also layered with a rich-center-poor-outskirts pattern. Chuo, historically in Shitamachi, is one of the wealthiest wards of Tokyo, thanks to its proximity to CBD jobs and the high rents commanded in an area where businesses build office towers.

The American pattern

The most common American pattern is that rich people live in the suburbs and poor people live in the inner city; the very center of an American city tends to be gentrified, creating a poverty donut surrounding near-center gentrification and in turn surrounded by suburban wealth. Bill Rankin of Radical Cartography has some maps, all as of 2000, and yet indicative of longer-term patterns.

New York is perhaps the best example of the poverty donut model: going outside the wealthy core consisting of Manhattan south of Harlem, inner Brooklyn, and a handful of gentrified areas in Jersey City and Hoboken near Manhattan, one always encounters poor areas before eventually emerging into middle-class suburbia. Directionality is weak, and usually localized – for example, the North Shore of Long Island is much wealthier than the South Shore, but both are east of the city.

Many American cities tend to have strong directionality in lieu of or in addition to the poverty donut. In Chicago, the North Side is rich, the West Side is working-class, and the South Side is poor. Many cities have favored quarters, such as the Main Line of Philadelphia, but that’s in addition to a poverty donut: it’s silly to speak of rich people moving west of Center City when West Philadelphia is one of the poorest areas in the region.

Where east-west directionality exists as in the meme, it’s often in cities without westerly winds. Los Angeles is at 34 degrees north and famously has a rich Westside and a poor Eastside – but those cannot possibly emerge from a prevailing wind pattern that isn’t consistent until one travels thousands of kilometers north. Houston is at 30 degrees north. More likely, the pattern in Los Angeles emerges from the fact that beachfront communities have always been recreational and the rich preferred to live nearby, and only the far south near the mouth of the river, in San Pedro and Long Beach, had an active industrial waterfront.

Sometimes, the directionality is the opposite of that of the meme. Providence has a rich east and poorer west. This is partly a longstanding pattern: the rivers flow west to east and north to south, and normally you’d expect rich people to prefer to live upriver, but in Providence the rivers are so small that only at their falls was there enough water power for early mills, producing industrial jobs and attracting working-class residents. However, the pattern is also reinforced with recent gentrification, which has built itself out of Brown’s campus on College Hill, spreading from there to historically less-well off East Side neighborhoods like Fox Point; industrial areas have no reason to gentrify in a city the size of Providence, and, due to the generations-long deindustrialization of New England, every reason to decline.

How Tunneling in New York is Easier Than Elsewhere

I hate the term “apples-to-apples.” I’ve heard those exact three words from so many senior people at or near New York subway construction in response to any cost comparison. Per those people, it’s inconceivable that if New York builds subways for $2 billion/km, other cities could do it for $200 million/km. Or, once they’ve been convinced that those are the right costs, there must be some justifiable reason – New York must be a uniquely difficult tunneling environment, or its size must mean it needs to build bigger stations and tunnels, or it must have more complex utilities than other cities, or it must be harder to tunnel in an old, dense industrial metropolis. Sometimes the excuses are more institutional but always drawn to exculpate the political appointees and senior management – health benefits are a popular excuse and so is a line like “we care about worker rights/disability rights in America.” The excuses vary but there’s always something. All of these excuses can be individually disposed of fairly easily – for example, the line about worker and disability rights is painful when one looks at the construction costs in the Nordic countries. But instead of rehashing this, it’s valuable to look at some ways in which New York is an easier tunneling environment than many comparison cases.

Geology

New York does not have active seismology. The earthquake-proofing required in such cities as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Tokyo, Istanbul, and Naples can be skipped; this means that simpler construction techniques are viable.

Nor is New York in an alluvial floodplain. The hard schist of Manhattan is not the best rock to tunnel in (not because it’s hard – gneiss is hard and great to tunnel in – but because it’s brittle), but cut-and-cover is viable. The ground is not going to sink 30 cm from subway construction as it did in Amsterdam – the hard rock can hold with limited building subsidence.

The underwater crossings are unusually long, but they are not unusually deep. Marmaray and the Transbay Tube both had to go under deep channels; no proposed East River or Hudson crossing has to be nearly so deep, and conventional tunnel boring is unproblematic.

History and archeology

In the United Kingdom, 200 miles is a long way. In the United States, 200 years is a long time. New York is an old historic city by American standards and by industrial standards, but it is not an old historic city by any European or Asian standard, unless the standard in question is that of Dubai. There are no priceless monuments in its underground, unlike those uncovered during tunneling in Mexico City, Istanbul, Rome, or Athens; the last three have tunneled through areas with urban history going back to Classical Antiquity.

In addition to past archeological artifacts, very old cities also run into the issue of priceless ruins. Rome Metro Line C’s ongoing expansion is unusually expensive for Italy – segment T3 is $490 million per km in PPP 2022 dollars – because it passes by the Imperial Forum and the Colosseum, where no expense can be spared in protecting monuments from destruction by building subsidence, limited by law to 3 mm; the stations are deep-mined because cut-and-cover is too destructive and so is the Barcelona method of large-diameter bores. More typical recent tunnels in Rome and Milan, even with the extra costs of archeology and earthquake-proofing, are $150-300 million/km (Rome costing more than Milan).

In New York, in contrast, buildings are valued for commercial purposes, not historic purposes. Moreover, in the neighborhoods where subways are built or should be, there is extensive transit-oriented development opportunity near the stations, where the subsidence risk is the greatest. It’s possible to be more tolerant of risk to buildings in such an environment; in contrast, New York spent effort shoring up a building on Second Avenue that is now being replaced with a bigger building for TOD anyway.

Street network

New York is a city of straight, wide streets. A 25-meter avenue is considered narrow; 30 is more typical. This is sufficient for cut-and-cover without complications – indeed, it was sufficient for four-track cut-and-cover in the 1900s. Bored tunnels can go underneath those same streets without running into building foundations and therefore do not need to be very deep unless they undercross older subway lines.

Moreover, the city’s grid makes it easier to shut down traffic on a street during construction. If Second Avenue is not viable as a through-route during construction, the city can make First Avenue two-way for the duration. Few streets are truly irreplaceable, even outside Manhattan, where the grid has more interruptions. For example, if an eastward extension of the F train under Hillside is desired, Jamaica can substitute for Hillside during construction and this makes the cut-and-cover pain (even if just at stations) more manageable.

The straightforward grid also makes station construction easier. There is no need to find staging grounds for stations such as public parks when there’s a wide street that can be shut down for construction. It’s also simple to build exits onto sidewalks or street medians to provide rapid egress in all directions from the platform.

Older infrastructure

Older infrastructure, in isolation, makes it difficult to build new tunnels, and New York has it in droves. But things are rarely isolated. It matters what older infrastructure is available, and sometimes it’s a boon more than a bane.

One way it can be a boon is if older construction made provisions for future expansion. This is the most common in cities with long histories of unrealized plans, or else the future expansion would have been done already; worldwide, the top two cities in such are New York and Berlin. The track map of the subway is full of little bellmouths and provisions for crossing stations, many at locations that are not at all useful today but many others at locations that are. Want to extend the subway to Kings Plaza under Utica? You’re in luck, there’s already a bellmouth leading from the station on the 3/4 trains. How about going to Sheepshead Bay on Nostrand? You’re in luck again, trackways leading past the current 2/5 terminus at Flatbush Avenue exist as the station was intended to be only a temporary terminal.

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 also benefits from such older infrastructure – cut-and-cover tunnels between the stations preexist and will be reused, so only the stations need to be built and the harder segment curving under 125th Street crossing under the 4/5/6.