Trucking and Grocery Prices

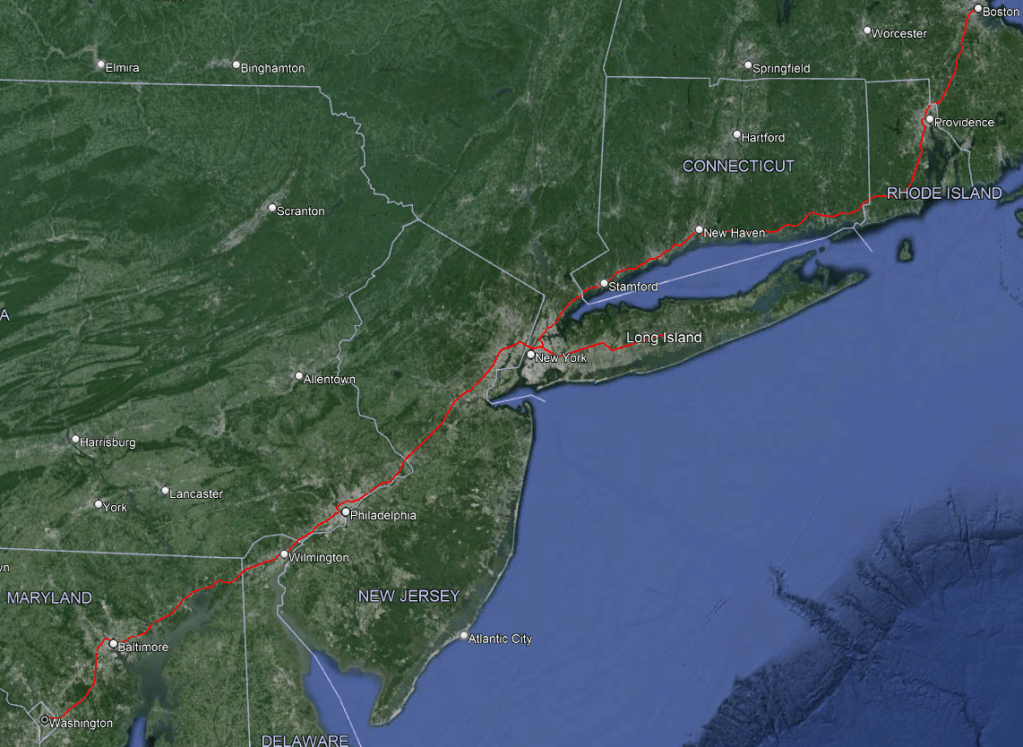

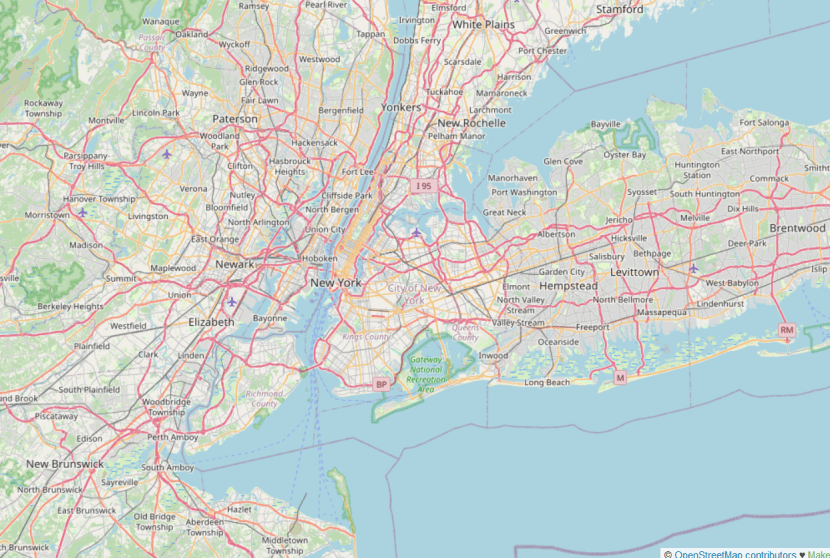

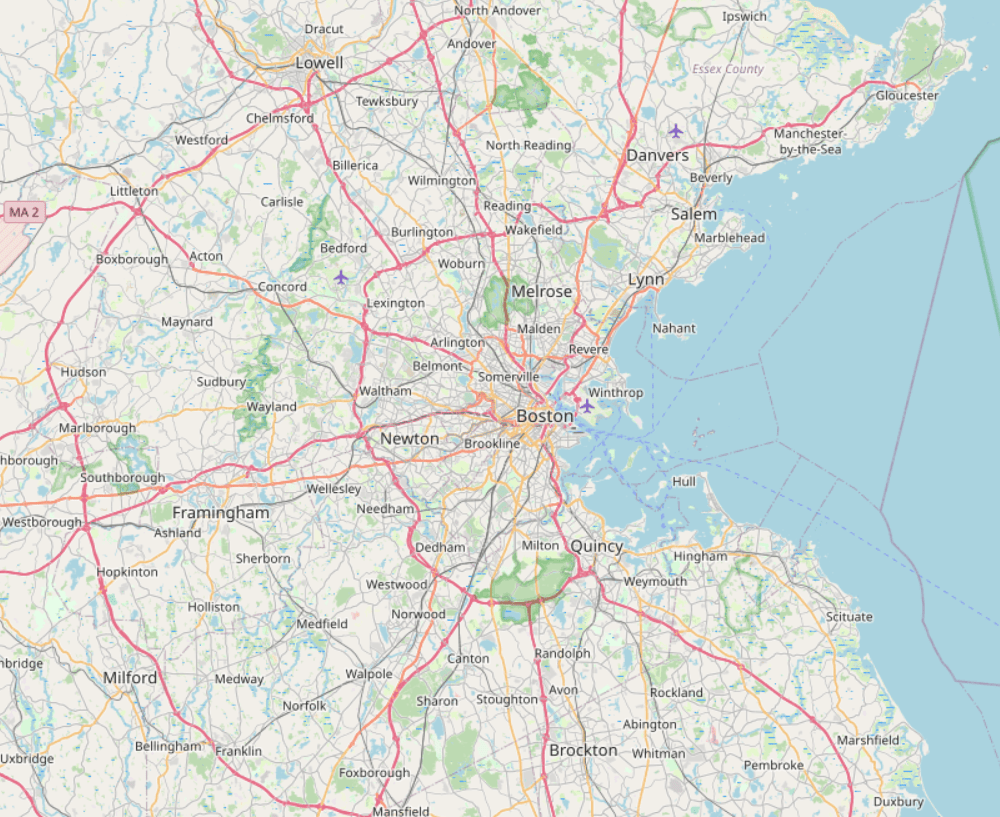

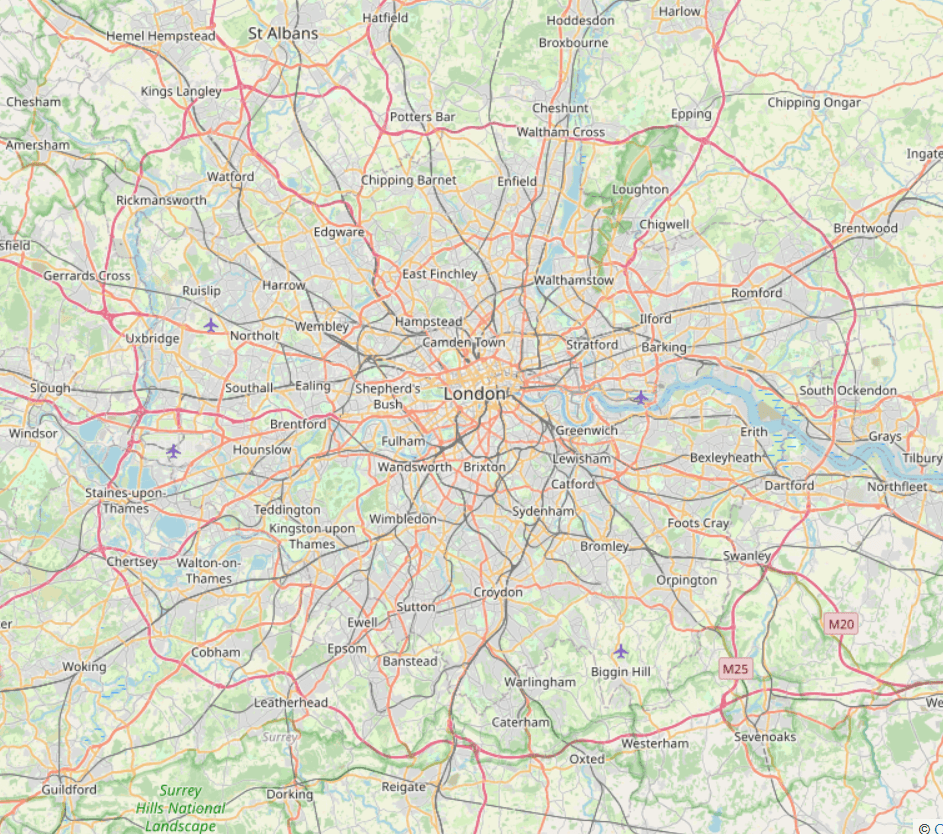

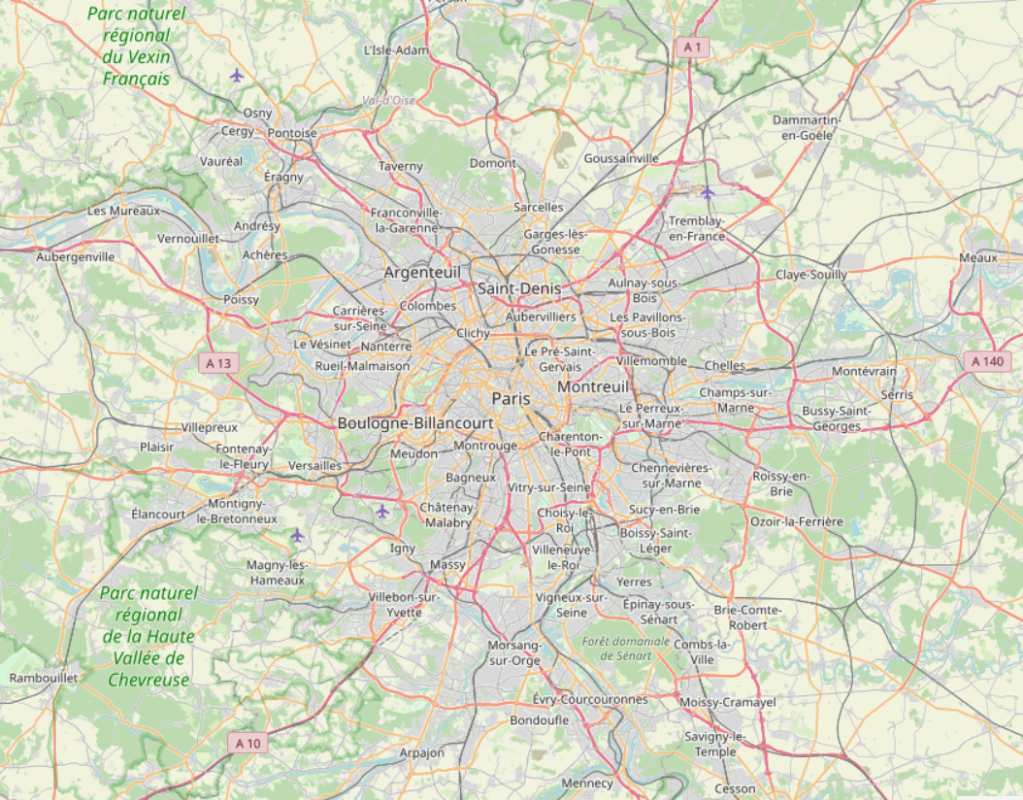

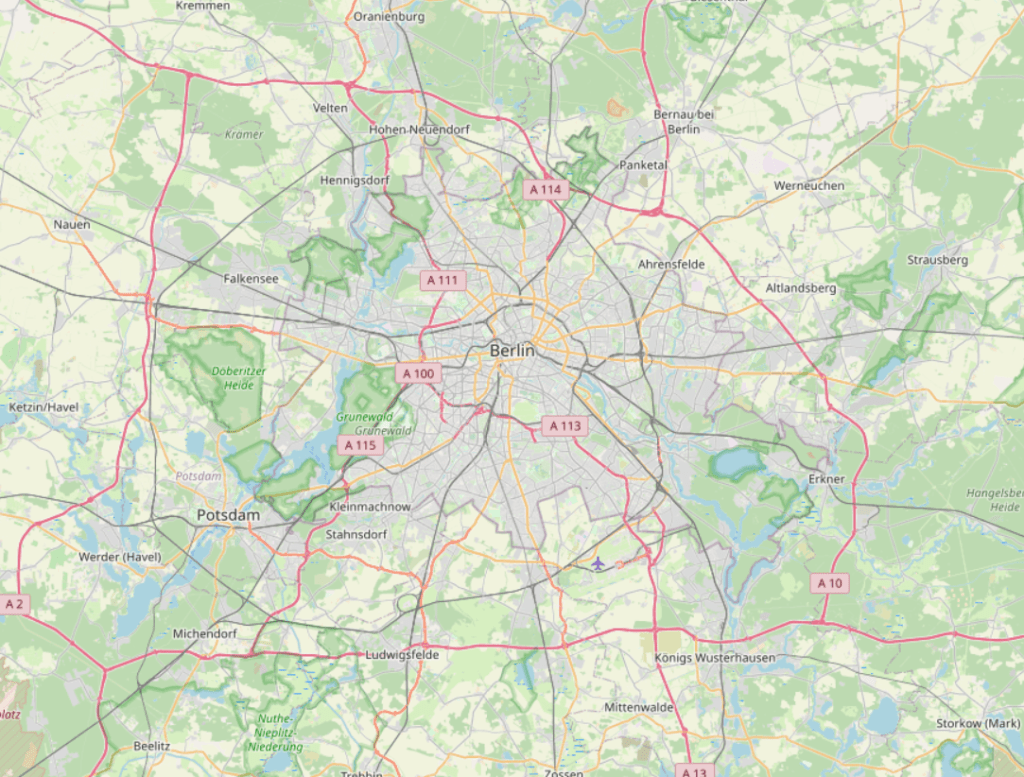

In dedication to people who argue in favor of urban motorways on the grounds that they’re necessary for truck access and cheap consumer goods, here are, at the same scale, the motorway networks of New York, London, Paris, and Berlin. While perusing these maps, note that grocery prices in New York are significantly higher than in its European counterparts. Boston is included as well, for an example of an American city with fewer inherent access issues coming from wide rivers with few bridges; grocery prices in Boston are lower than in New York but higher than in Paris and Berlin (I don’t remember how London compares).

The maps

The scale isn’t exactly the same – it’s all sampled from the same zoom level on OpenStreetMaps; New York is at 40° 45′ N and Berlin is at 52° 30′ N, so technically the Berlin map is at a 1.25 times closer zoom level than the New York map, and the others are in between. But it’s close. Motorways are in red; the Périphérique, delineating the boundary between Paris and its suburbs, is a full freeway, but is inconsistently depicted in red, since it gives right-of-way to entering over through-traffic, typical for regular roads but not of freeways, even though otherwise it is built to freeway standards.

Discussion

The Périphérique is at city limits; within it, 2.1 million people live, and 1.9 million work, representing 32% of Ile-de-France’s total as of 2020. There are no motorways within this zone; there were a few but they have been boulevardized under the mayoralty of Anne Hidalgo, and simultaneously, at-grade arterial roads have had lanes reduced to make room for bike lanes, sidewalk expansion, and pedestrian plazas. Berlin Greens love to negatively contrast the city with Paris, since Berlin is slowly expanding the A100 Autobahn counterclockwise along the Ring (in the above map, the Ring is in black; the under-construction 16th segment of A100 is from the place labeled A113 north to just short of the river), and is not narrowing boulevards to make room for bike lanes. But the A100 ring isn’t even complete, nor is there any plan to complete it; the controversial 17th segment is just a few kilometers across the river. On net, the Autobahn network here is smaller than in Ile-de-France, and looks similar in size per capita. London is even more under-freewayed – the M25 ring encloses nearly the entire city, population 8.8 million, and within it are only a handful of radial motorways, none penetrating into Central London.

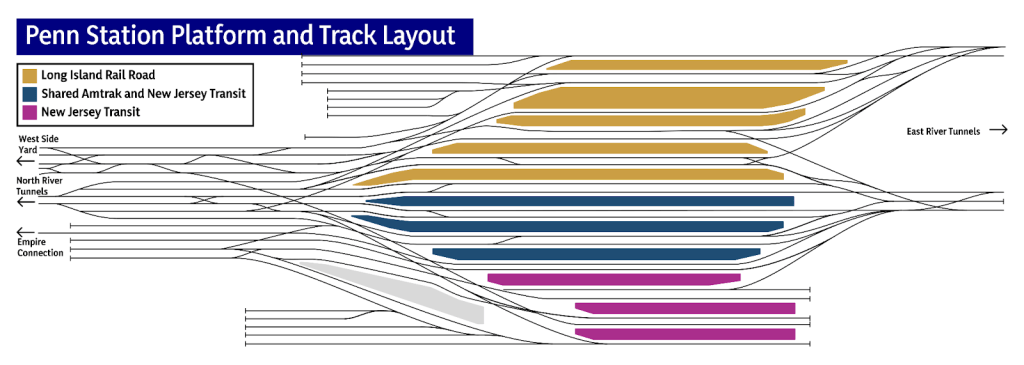

The contrast with American cities is stark. New York is, by American standards, under-freewayed, legacy of early freeway revolts going back to the 1950s and the opposition to the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have connected the Holland Tunnel with the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges; see map here. There’s practically no penetration into Manhattan, just stub connections to the bridges and tunnels. But Manhattan is not 2.1 million people but 1.6 million – and we should probably subtract Washington Heights (200,000 people in CB 12) since it is crossed by a freeway or even all of Upper Manhattan (650,000 in CBs 9-12). Immediately outside Manhattan, there are ample freeways, crossing close-in neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, the South Bronx, and Jersey City. The city is not automobile-friendly, but it has considerably more car and truck capacity than its European counterparts. Boston, with a less anti-freeway history than New York, has penetration all the way to Downtown Boston, with the Central Artery, now the Big Dig, having all-controlled-access through-connections to points north, west, and south.

Grocery prices

Americans who defend the status quo of urban freeways keep asking about truck access; this played a role in the debate over what to do about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway’s Downtown Brooklyn section. Against shutting it down, some New Yorkers said, there is the issue of the heavy truck traffic, and where it would go. This then led to American triumphalism about how truck access is important for cheap groceries and other goods, to avoid urban traffic.

And that argument does not survive a trip to a New York (or other urban American) supermarket and another trip to a German or French one. German supermarkets are famously cheap, and have been entering the UK and US, where their greater efficiency in delivering goods has put pressure on local competitors. Walmart, as famously inexpensive as Aldi and Lidl (and generally unavailable in large cities), has had to lower prices to compete. Carrefour and Casino do not operate in the US or UK, and my impression of American urbanists is that they stereotype Carrefour as expensive because they associate it with their expensive French vacations, but outside cities they are French-speaking Walmarts, and even in Paris their prices, while higher, are not much higher than those of German chains in Germany and are much lower than anything available in New York.

While the UK has not given the world any discount retailer like Walmart, Carrefour, or Lidl, its own prices are distinctly lower than in the US, at least as far as the cities are concerned. UK wages are infamously lower than US wages these days, but the UK has such high interregional inequality that wages in London, where the comparison was made, are not too different from wages in New York, especially for people who are not working in tech or other high-wage fields (see national inequality numbers here). In Germany, where inequality is similar to that of the UK or a tad lower, and average wages are higher, I’ve seen Aldi advertise 20€/hour positions; the cookies and cottage cheese that I buy are 1€ per pack where a New York supermarket would charge maybe $3 for a comparable product.

Retail and freight

Retail is a labor-intensive industry. Its costs are dominated by the wages and benefits of the employees. Both the overall profit margins and the operating income per employee are low; increases in wages are visible in prices. If the delivery trucks get stuck in traffic, are charged a congestion tax, have restricted delivery hours, or otherwise have to deal with any of the consequences of urban anti-car policy, the impact on retail efficiency is low.

The connection between automobility and cheap retail is not that auto-oriented cities have an easier time providing cheap goods; Boston is rather auto-oriented by European standards and has expensive retail and the same is true of the other secondary transit cities of the United States. Rather, it’s that postwar innovations in retail efficiency have included, among other things, adapting to new mass motorization, through the invention of the hypermarket by Walmart and Carrefour. But the main innovation is not the car, but rather the idea of buying in bulk to reduce prices; Aldi achieves the same bulk buying with smaller stores, through using off-brand private labels. In the American context, Walmart and other discount retailers have with few exceptions not bothered providing urban-scale stores, because in a country with, as of 2019, a 90% car modal split and a 9% transit-and-active-transportation modal split for people not working from home, it’s more convenient to just ignore the small urban patches that have other transportation needs. In France and Germany, equally cheap discounters do go after the urban market – New York groceries are dominated by high-cost local and regional chains, Paris and Berlin ones are dominated by the same national chains that sell in periurban areas – and offer low-cost goods.

The upshot is that a city can engage in the same anti-car urban policies as Paris and not at all see this in retail prices. This is especially remarkable since Paris’s policies do not include congestion pricing – Hidalgo is of the opinion that rationing road space through prices is too neoliberal; normally, congestion pricing regimes remove cars used by commuters and marginal non-commute personal trips, whereas commercial traffic happily pays a few pounds to get there faster. Even with the sort of anti-car policies that disproportionately hurt commercial traffic more than congestion pricing, Paris has significantly cheaper retail than New York (or Boston, San Francisco, etc.).

And Berlin, for all of its urbanist cultural cringe toward Paris, needs to be classified alongside Paris and not alongside American cities. The city does not have a large motorway network, and its inner-urban neighborhoods are not fast drive-throughs. And yet in the center of the city, next to pedestrian plazas, retailers like Edeka and Kaufland charge 1€ for items that New York chains outside Manhattan sell for $2.5-4. Urban-scale retail deliveries are that unimportant to the retail industry.