Mixing High- and Low-Speed Trains

I stream on Twitch (almost) every week on Saturdays – the topic starting now is fare systems. Two weeks ago, I streamed about the topic of how to mix high-speed rail and regional rail together, and unfortunately there were technical problems that wrecked the recording and therefore I did not upload the video to YouTube as I usually do. Instead, I’d like to write down how to do this. The most obvious use case for such a blending is the Northeast Corridor, but there are others.

The good news is that good high-speed rail and good legacy rail are complements, rather than competing priorities. They look like competing priorities because, as a matter of national tradition of intercity rail, Japan and France are bad at low-speed rail outside the largest cities (and China is bad even in the largest cities) and Germany is bad at high-speed rail, so it looks like one or the other. But in reality, a strong high-speed rail network means that distinguished nodes with high-speed rail stations become natural points of convergence of the rail network, and those can then be set up as low-speed rail connection nodes.

Where there is more conflict is on two-track lines with demand for both regional and intercity rail. Scheduling trains of different speeds on the same pair of tracks is dicey, but still possible given commitment to integration of schedule, rolling stock, and timetable. The compromises required are smaller than the cost of fully four-tracking a line that does not need so much capacity.

Complementarity

Whenever a high-speed line runs separately from a legacy line, they are complements. This occurs on four-track lines, on lines with separate high-speed tracks running parallel to the legacy route, and at junctions where the legacy lines serve different directions or destinations. In all cases, network effects provide complementarity.

As a toy model, let’s look at Providence Station – but not at the issue of shared track on the Northeast Corridor. Providence has a rail link not just along the Northeast Corridor but also to the northwest, to Woonsocket, with light track sharing with the mainline. Providence-Woonsocket is 25 km, which is well within S-Bahn range in a larger city, but Providence is small enough that this needs to be thought of as scheduled regional rail. A Providence-Woonsocket regional link is stronger in the presence of high-speed rail, because then Woonsocket residents can commute to Boston with a change in Providence, and travel to New York in around 2 hours also with a change in Providence.

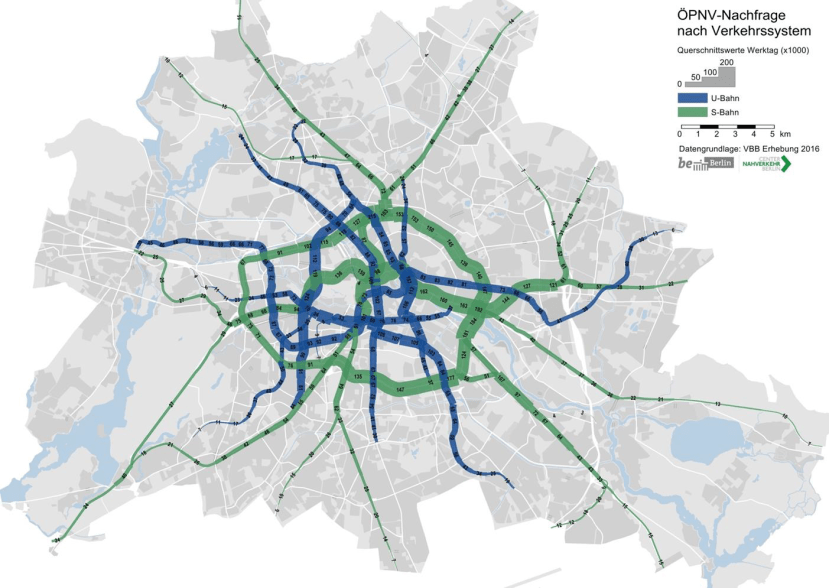

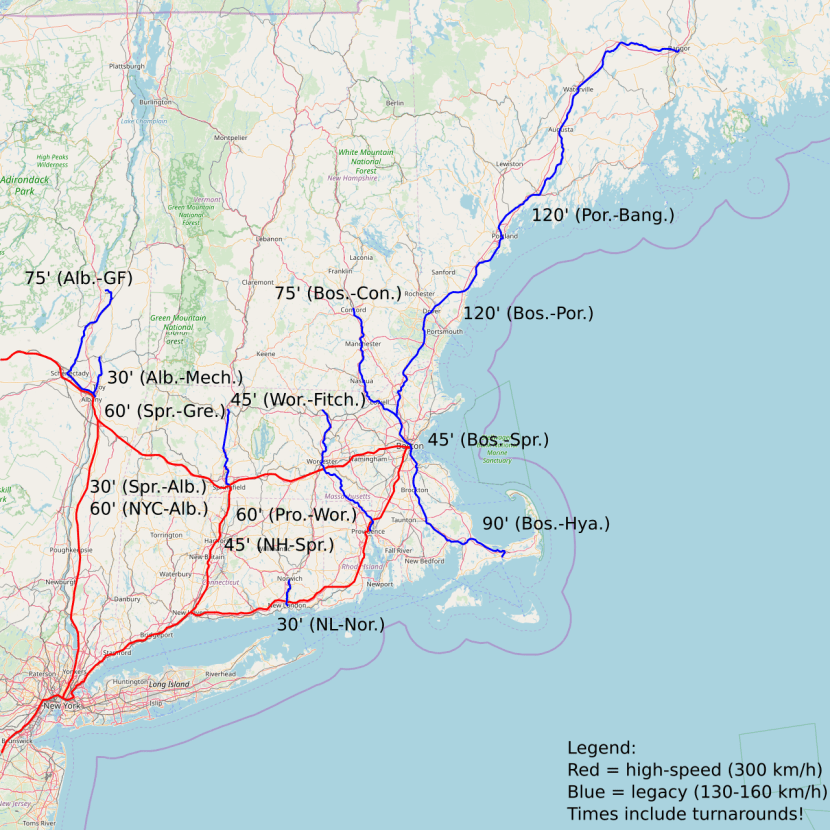

More New England examples can be found with Northeast Corridor tie-ins – see this post, with map reproduced below:

The map hides the most important complement: New Haven-Hartford-Springfield is a low-speed intercity line, and the initial implementation of high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor should leave it as such, with high-speed upgrades later. This is likely also the case for Boston-Springfield – the only reason it might be worthwhile going straight from nothing to high-speed rail is if negotiations with freight track owner CSX get too difficult or if for another reason Massachusetts can’t electrify the tracks at reasonable cost and run fast regional trains.

There’s also complementarity with lines that are parallel to the Northeast Corridor, like the current route east of New Haven, which the route depicted in the map bypasses. This route serves Southeast Connecticut communities like Old Saybrook and can efficiently ferry passengers to New Haven for onward connections.

In all of these cases, there is something special: Woonsocket-Boston is a semireasonable commute, New London connects to the Mohegan Sun casino complex, New Haven-Hartford and Boston-Springfield are strong intercity corridors by themselves, Cape Cod is a weekend getaway destination. That’s fine. Passenger rail is not a commodity – something special almost always comes up.

But in all cases, network effects mean that the intercity line makes the regional lines stronger and vice versa. The relative strength of these two effects varies; in the Northeast, the intercity line is dominant because New York is big and off-mainline destinations like Woonsocket and Mohegan are not. But the complementarity is always there. The upshot is that in an environment with a strong regional low-speed network and not much high-speed rail, like Germany, introducing high-speed rail makes the legacy network stronger; in one that is the opposite, like France, introducing a regional takt converging on a city center TGV station would likewise strengthen the network.

Competition for track space

Blending high- and low-speed rail gets more complicated if they need to use the same tracks. Sometimes, only two tracks are available for trains of mixed speeds.

In that case, there are three ways to reduce conflict:

- Shorten the mixed segment

- Speed up the slow trains

- Slow down the fast trains

Shortening the mixed segment means choosing a route that reduces conflict. Sometimes, the conflict comes pre-shortened: if many lines converge on the same city center approach, then there is a short shared segment, which introduces route planning headaches but not big ones. In other cases, there may be a choice:

- In Boston, the Franklin Line can enter city center via the Northeast Corridor (locally called Southwest Corridor) or via the Fairmount Line; the choice between the two routes is close based on purely regional considerations, but the presence of high-speed rail tilts it toward Fairmount, to clear space for intercity trains.

- In New York, there are two routes from New Rochelle to Manhattan. Most commuter trains should use the route intercity trains don’t, which is the Grand Central route; the only commuter trains running on Penn Station Access should be local ones providing service in the Bronx.

- In the Bay Area, high-speed rail can center from the south via Pacheco Pass or from the east via Altamont Pass. The point made by Clem Tillier and Richard Mlynarik is that Pacheco Pass involves 80 km of track sharing compared with only 42 km for Altamont and therefore it requires more four-tracking at higher cost.

Speeding up the slow trains means investing in speed upgrades for them. This includes electrification where it’s absent: Boston-Providence currently takes 1:10 and could take 0:47 with electrification, high platforms, and 21st-century equipment, which compares with a present-day Amtrak schedule of 0:35 without padding and 0:45 with. Today, mixing 1:10 and 0:35 requires holding trains for an overtake at Attleboro, where four tracks are already present, even though the frequency is worse than hourly. In a high-speed rail future, 0:47 and 0:22 can mix with two overtakes every 15 minutes, since the speed difference is reduced even with the increase in intercity rail speed – and I will defend the 10-year-old timetable in the link.

If overtakes are present, then it’s desirable to decrease the speed difference on shared segments but then increase it during the overtake: ideally the speed difference on an overtake is such that the fast train goes from being just behind the slow train to just ahead of it. If the overtake is a single station, this means holding the slow train. But if the overtake is a short bypass of a slow segment, this means adding stops to the slow train to slow it down even further, to facilitate the overtake.

A good example of this principle is at the New York/Connecticut border, one of the slowest segments of the Northeast Corridor today. A bypass along I-95 is desirable, even at a speed of 200-230 km/h, because the legacy line is too curvy there. This bypass should also function as an overtake between intercity trains and express commuter trains, on a line that today has four tracks and three speed classes (those two and local commuter trains). To facilitate the overtake, the slow trains (that is, the express commuter trains – the locals run on separate track throughout) should be slowed further by being made to make more stops, and thus all Metro-North trains, even the express trains, should stop at Greenwich and perhaps also Port Chester. The choice of these stops is deliberate: Greenwich is one of the busiest stops on the line, especially for reverse-commuters; Port Chester does not have as many jobs nearby but has a historic town center that could see more traffic.

Slowing down the intercity trains is also a possibility. But it should not be seen as the default, only as one of three options. Speed deterioration coming from such blending in a serious problem, and is one reason why the compromises made for California High-Speed Rail are slowing down the trip time from the originally promised 2:40 for Los Angeles-San Francisco to 3:15 according to one of the planners working on the project who spoke to me about it privately.