The dominant length of high-speed rail platforms in China, Japan, South Korea, and Europe is 400 meters, which usually corresponds to 16-car trains. The Northeast Corridor unfortunately does not run such long trains; intercity trains on it today are usually eight cars long, and the under construction Avelia Liberty sets are 8.5 cars long. Demand even today is high enough that trains fill even with very high fares, and so providing more service through both higher frequency and longer trains should be a priority. This post goes over what needs to happen to lengthen the trains to the global norm for high-speed rail. More trains need to be bought, but also the platforms need to be lengthened at many stations, with varying levels of difficulty.

The station list to consider is as follows:

- Boston South Station

- Providence

- New London-HSR

- New Haven

- Stamford

- New York Penn Station

- Newark Penn Station

- Trenton

- Philadelphia 30th Street

- Wilmington

- Baltimore Penn Station

- BWI

- Washington Union Station

Some of these are local-only stations – the fastest express trains should not be stopping at New London or BWI, and whether any train stops at Stamford or Trenton is a matter of timetabling (the headline timetable we use includes Stamford on all trains but I am not wedded to it). In order, allowing 16-car trains at these stations involves the following changes.

Boston

South Station’s longest platforms today are those between tracks 8 and 9 and between tracks 10 and 11, both 12 cars long. To their immediate south is the interlocking, so lengthening would be difficult.

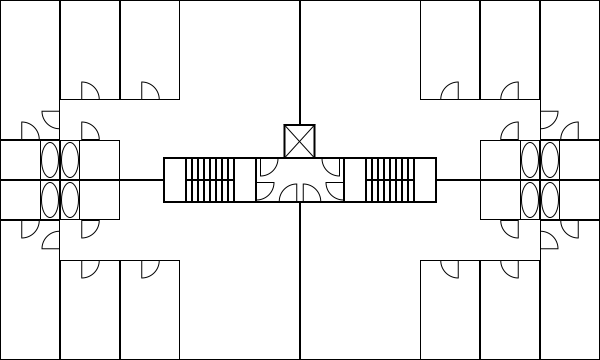

Moreover, the best platforms for Northeast Corridor trains to use at South Station are to the west. The best way to organize South Station is as four parallel stations, from west to east (in increasing track number order) the Worcester Line, the Northeast Corridor and branches, the Fairmount Line, and the Old Colony Lines, with peak traffic of respectively 8, 12 or 16, 4 or 8, and 6 trains per hour. This gives the Northeast Corridor tracks 4-7 or possibly 4-9; 4-7 means the Franklin Line has to pair with the Fairmount Line to take advantage of having more tracks, and may be required anyway since pairing the Franklin Line with the Northeast Corridor (Southwest Corridor within the city of Boston) would constrain the triple-track corridor too much, with 12 peak commuter trains and 4 peak intercity trains an hour.

The platform between tracks 6 and 7 is 11 cars long, but to its south is a gap in the tracks as the interlocking leads tracks 6 and 7 in different directions, and thus it can be lengthened to 16 cars within its footprint. The platform between tracks 4 and 5 is harder to lengthen, but this is still doable if the track that tracks 5 and 6 merge into south of the station is moved in conjunction with a project to lengthen the other platform.

Of note, the other Boston station, Back Bay, is rather constrained, with nearly the entire platforms under an overbuild, complicating any rebuild.

Providence

Providence has 12-car platforms. The southern edge is under an overbuild with rapid convergence between the tracks and cannot reasonably be extended. But the northern edge is in the open air, and lengthening is possible. The northern edge would be on rather tight curves, which is not acceptable under most standards, but in such a constrained environment, waivers are unavoidable, as is the case throughout urban Germany.

New London

This is a new station and can be built to the required length from the start.

New Haven

The current station platforms are only 10 cars long, but there is space to expand them in both directions. The platform area is in effect a railyard, a good example of the American tradition in which the train station is not where the trains are (as in Europe) but rather next to where the trains are.

A rebuild is needed anyway, for two reasons. First, it is desirable to build a bypass roughly following I-95 to straighten the route beginning immediately north of the station, even cutting off State Street in order to go straight to East Haven rather than curve to the north as on the current route. And second, the current usage of the station is that Amtrak uses tracks 1-4 (numbered west to east as in Boston) and Metro-North uses tracks 8-14, which forces Amtrak and Metro-North trains to cross each other at grade from their slow-fast-fast-slow pattern on the running line to the fast-fast-slow-slow pattern at the station. In the future, the station should be used in such a way that intercity trains either divert north to Hartford or Springfield or go immediately east on a flying junction to the high-speed bypass toward Rhode Island, without opposed-direction flat junctions; the flying junction is folded into the cost of the bypass and dominates the cost of rebuilding the platforms, as the space immediately north and south of the platforms is largely empty.

Stamford

Stamford has 12-car platforms. Going beyond that is hard, to the point that a more detailed alternatives analysis must include the option of not having intercity trains stop there at all, and instead running 12-car express commuter trains, lengthening major intermediate stops like South Norwalk (currently 10 cars long) and Bridgeport (currently 8) instead.

To keep the mainline option of stopping at Stamford, a platform rebuild is needed, in two ways. First, the station today has five tracks, a both literally and figuratively odd number, not useful for any timetable, with the middle track, numbered 1 (from north to south the numbers are 5, 3, 1, 2, 4), not served by a platform. And second, the platform between tracks 3 and 5 can at best be lengthened to 14 cars, while that between tracks 2 and 4 cannot be lengthened without moving tracks on viaducts. This means that some mechanism to rebuild the station should be considered, to create four tracks with more space between them so that 16-car platforms are viable; this should be bundled with a flying junction farther east to grade-separate the New Canaan Branch from the mainline.

A quick-and-dirty option, potentially viable here but almost nowhere else, is selective door opening, at the cost of longer dwell times. Normally selective door opening should not be used – it confuses passengers, for one. However, here it may be an option, as intercity traffic here is unlikely to be high; traffic today is 323,791 in financial 2023, the lowest of any station under consideration in this post unless one counts New London. The only reason to stop here in the first place is commuter ridership, in which case mechanisms such as restricting unreserved seats to the central 12 cars can be used.

New York

Penn Station has multiple platforms already long enough for 16- and even 17-car trains, including the one we pencil for all high-speed intercity trains in the proposal, platform 6 between tracks 11 and 12, as well as the two adjacent platforms, 5 and 7. (Note that unlike at New Haven and Boston, platform numbers at Penn increase south to north, that is right to left from the perspective of a Boston-bound traveler.)

Thank the god of railways, since platform expansion requires a multi-billion dollar project to remove the Madison Square Garden overbuild in the most optimistic case; in a more pessimistic case, it would also require removing the Moynihan Station overbuild.

Newark

Newark Penn Station’s platforms are in a grand structure about 14.5 cars long. Thankfully, they extend a bit south of it, producing about 16 cars’ worth of platform on the west (southbound) side, between tracks 3 and 4; as in New York, track numbers increase east to west. On the east side, PATH interposes between the two tracks, which have a cross-platform transfer from northbound New Jersey Transit trains to PATH. The platform structures and their extensions do have enough length to allow 16-car trains – indeed they go as long as 18 – but the southern ends are currently disused and would require some rehabilitation.

Trenton

Trenton has a 12.5 car long southbound platform and an 11.5 car long northbound platform. There is practically no room for an expansion if no tracks are moved. If tracks are moved, then some space can be created, but only enough for about 14 cars, not 16.

However, traffic is low, the second lowest among stations under consideration next to Stamford. The suite of Stamford solutions is thus most appropriate here: selective door opening with only the middle 12 cars (naturally the same as at Stamford) open to commuters, or just not stopping at this station at all. The only reason we’re even considering stopping here is timetabling-related: trains should be running every 10 minutes around New York but every 15 between Baltimore and Washington, or else significant expansion of quad-tracking on the Penn Line is required, and so a local stop should be added as a buffer, which can be Trenton or BWI, and BWI has twice the current Amtrak traffic of Trenton.

Philadelphia

30th Street Station has 14-car platforms. Selective door opening is basically impossible given the high expected traffic at this station, and instead platform expansion is required. There is an overbuild, but the tracks stay straight and only begin curving after a few tens of meters, which gives room for extension; from the north end to the overbuild to where the tracks begin curving toward one another to the south is 15.5 cars, and there is room north of the overbuild between the tracks.

Whatever reconstruction project is needed is helped by the low traffic at these platforms. SEPTA uses the upper level of the station, with tracks oriented east-west. The north-south lower level is only used by Amtrak, which could be easily reduced to three platform tracks (two Northeast Corridor, one Keystone) if need be, out of 11 today. Thus, staging construction can be done easily and intrusively, with no care taken to preserve track access during the work, as half the station platforms can be closed off at once.

Wilmington

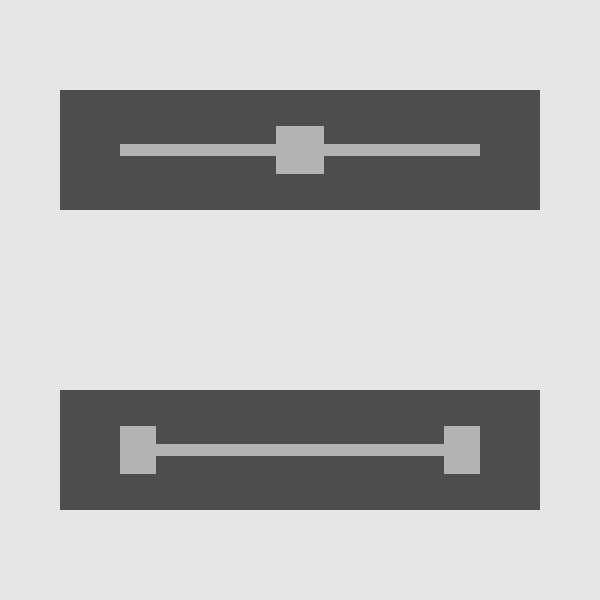

Wilmington is frustrating, in that there is platform space for 16 cars rather easily, but it’s on inconsistent sides of the tracks. Track numbers increase south to north; track 1 has a side platform, there’s an island platform between tracks 2 and 3, and then track 3 also has a side platform on the other side, extending well to the east of the island platform. The island platform and the track 1 platform are about 12.5 cars long, and the track 3 side platform is 13.5 cars long. Thus, an extension, selective door opening, or a station rebuild is required.

The island platform can be extended about one car in each direction, so it cannot be the solution without selective door opening. Both side platforms can be extended somewhat to the west: the track 1 platform can be extended to 16 cars, but it would need to be elevated in the narrow space between the track viaduct and the station parking garage; the track 3 platform can be extended in both directions, avoiding a new elevated extension over North King Street.

If for some reason an extension of the track 1 platform is not possible, then selective door opening can be used, but not as reliably as at lower-traffic Stamford or Trenton, and overall I would not recommend this solution. A station rebuild then becomes necessary: the station has three tracks but doesn’t need more than two if SEPTA and Amtrak can be timetabled right, and then the removal of either track 1 or track 2 would create space for a longer platform.

Baltimore

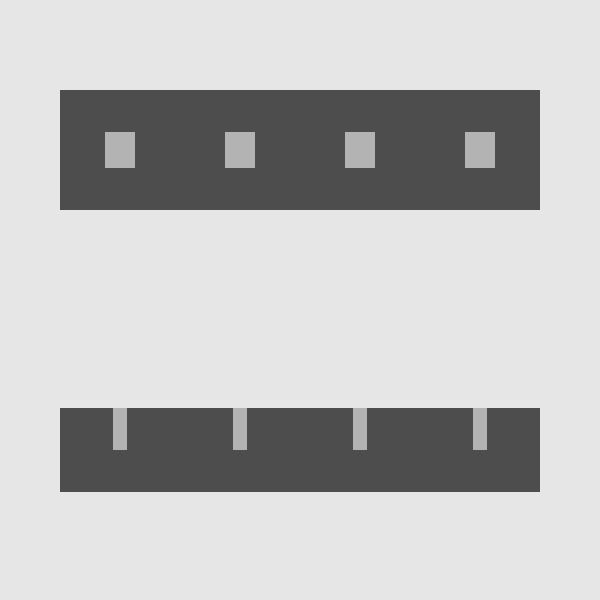

Baltimore Penn has seven tracks, numbered from south to north 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, F. Their platforms are 10 to 13 cars long. Northbound trains are more or less forced to use the platform between tracks 1 and 3, since the way the route tapers to a three-, then four-track line to the east forces all eastbound trains to use mainline track 1; this platform is rather narrow at its east end but has space to the west for a 16-car extension. Westbound trains can use either the platform between tracks 4 and 5 or that between tracks 6 and 7, with tracks 4 and 6 preferred over 7 as they reach the express westbound track (track 5 stub-ends). Both platforms can be extended, with the platform between tracks 6 and 7 requiring a one-car extension to the east where a ramp down to track level for track workers exists whereas that between tracks 4 and 5 has ample unused space to its west.

BWI

The two side platforms at BWI are just under 13 cars long. However, nowhere else on the corridor is an extension easier: the station is located in an undeveloped wooded area, with space cleared on both sides of the track so that tree cutting is likely unnecessary west of the tracks and certainly unnecessary east of them.

The station itself needs a rebuild anyway, due to already existing plans to widen it from three to four tracks. This is required to enable intercity trains to overtake commuter trains anyway, unless delicate timetabling on triple track is used or another part of the Penn Line is set up as a four-track overtake. The plans are rather advanced, but platform extensions can be pursued as an add-on, without disturbing them due to the easy nature of the right-of-way.

Washington

Washington is set up as two separate stations, a high-platform terminal to the west and a low-platform through-station to the east on a lower level. Track numbers increase west to east, the western part taking 7-20 (though only 9-20 are high and wired) and the eastern part 23-30. None of the western platforms is long enough, but multiple options still exist:

- The platform between tracks 9 and 10 has room for an extension.

- The platforms between tracks 15 and 16 and between tracks 16 and 17 look like they already have extensions, if not open for passengers.

- The platforms between track 17 and track 18 and between tracks 19 and 20 are only 12 cars long, but tracks could be cannibalized in the open air to make a long enough platform, especially since the reason track numbers 21 and 22 are skipped is that there used to be tracks there and now there’s empty space.

- The platform between tracks 25 and 26 is long enough, and could be raised to have level boarding.

The existing platforms that can be extended easily are sufficient in number, but probably not in location – it’s ideal for the platforms to be close together, to simplify the interlocking as trains have to be scheduled to enter and leave the station without opposite-direction conflicts. If it’s doable even with a split between platforms separated by multiple tracks then it’s ideal, but otherwise, the extra work on tracks 17-20 may be necessary, converting a part of the station that presently has six tracks and four platforms into likely four tracks and two platforms.

Conclusion

All of this looks doable. The hardest station, Stamford, is skippable if selective door opening is unviable after all and a rebuild is too expensive. Among the other stations, light rebuilds are needed at Boston, Wilmington, and maybe Washington; New Haven needs a more serious rebuild as part of the bypass, but the station platforms are a routine extension where there is already room between the tracks. The most untouchable station, New York, already has multiple platforms of the required length at the required location within the station.