I wrote a Twitter thread about high-speed rail in the United States that I’d like to expand to a full post, because it illustrates a key network design principle. It comes from Metcalfe’s law: the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of nodes. The upshot is that once you start a high-speed rail network, the benefits to extending it in every direction are large even if the subsequent cities connected are not nearly so large as on the initial segment. Conversely, isolated networks from the initial segments are of lower value.

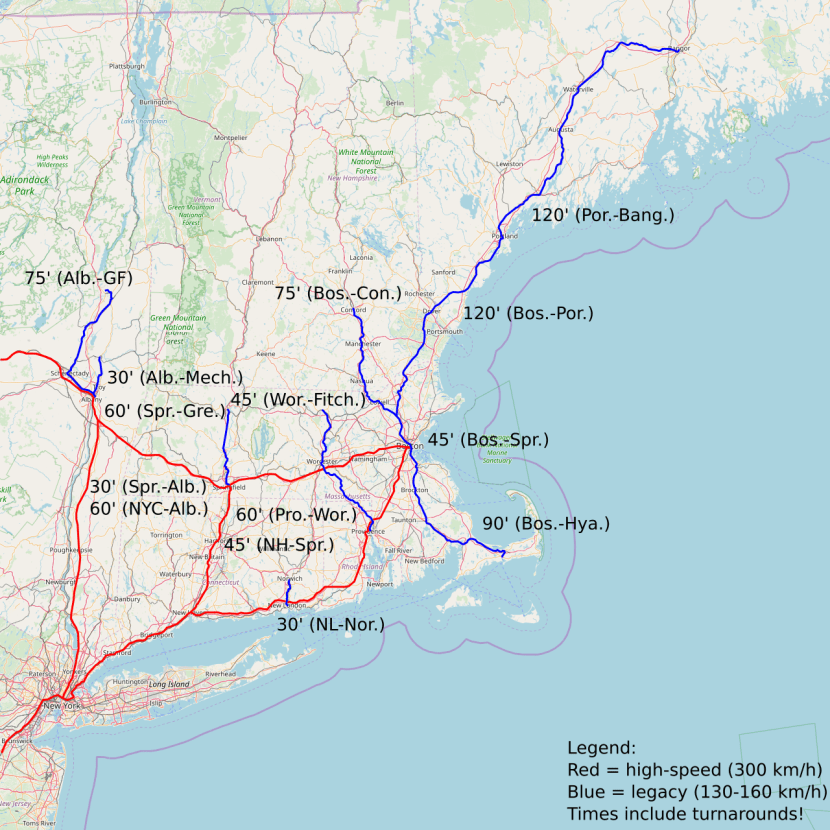

The implication for the United States is that, first of all, it should invest in high-speed rail on the entire Northeast Corridor from Boston to Washington, aiming for 3-3.5 hour end-to-end trip times. And as the Corridor is completed, the priority should be extensions in all directions: south to Atlanta, north to Springfield and (by legacy rail) Portland, west to Pittsburgh and Cleveland, northwest to Upstate New York and Toronto.

The model

To quantify the benefits, I’m going to look purely at railroad finances: construction costs go out, annual profits go in. Intercity high-speed rail pretty much universally turns an operating profit, the question is just how it compares with interest on capital construction. For this, in turn, we need to estimate ridership. Here is an illustrative photo of the sophistication of the model I am using:

In the picture: someone who gets on the train without letting you get off first. Credit: William O’Connor.

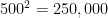

The theoretical model for ridership is called a gravity model: ridership between two cities of populations Pop_A and Pop_B at distance d is proportional to

However, two complications arise. First of all, there are some diseconomies of scale: the trip time from the train station to one’s ultimate destination is likely to be much higher if the city is as huge as Tokyo or New York than if it is smaller. Empirically, this can be resolved by raising the populations of both cities to an exponent slightly less than 1; on the data I have, which is Japanese (east and west of Tokyo), Spanish (Madrid-Barcelona, Madrid-Seville), and French (see post here – all its sources link-rotted), the best exponent looks like 0.8.

And second, at short distance, the gravity model fails for two reasons: first, access time dominates so in-vehicle time is less important, and second, passengers drive more and take fast trains less. In fact, on the data I’m most certain of the quality of – that from Japan – ridership seems insensitive to distance up to and beyond the distance of Tokyo-Osaka, which is 515 km by Shinkansen. Tokyo-Hiroshima, 821 km and 3:55 by Shinkansen, underperforms Tokyo-Osaka by a factor of about 1.6 if the model is  if we lump in air with rail traffic; of course, air travel time is incredibly insensitive to distance over this range, so it may not be fair to do so. French data taken about 3 hours out of Paris overperforms the mid-distance Shinkansen, although that’s partly an artifact of lower fares on the TGV.

if we lump in air with rail traffic; of course, air travel time is incredibly insensitive to distance over this range, so it may not be fair to do so. French data taken about 3 hours out of Paris overperforms the mid-distance Shinkansen, although that’s partly an artifact of lower fares on the TGV.

To square this circle, I’m going to make the following assumption: the model is,

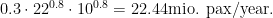

If the populations of the two metro areas so connected are in millions then the best constant for the model is 75,000: that is, take out the number the formula spits, multiply by  to get rid of the denominator at low d, multiply by 0.3, and make that your annual number of passengers in millions.

to get rid of the denominator at low d, multiply by 0.3, and make that your annual number of passengers in millions.

Finally, operating costs are set at $0.05/seat-km or $0.07/passenger-km, which is somewhat lower than on the TGV but realistic given how overstaffed and peaky the TGV is. This is inclusive of the capital costs of rolling stock, but not of fixed infrastructure. Fares are set at $0.135/passenger-km, a figure chosen to make New York-Boston and New York-Washington exactly $49 each, but on trips longer than 770 km, the fares rise more slowly so that profit is capped at $50/trip. Of note, Shinkansen fares are about $0.23/p-km on average, so training data on Shinkansen fares for a network that’s supposed to charge lower fares yields conservative ridership estimates; I try to be conservative since my model is, as the picture may indicate, not the most reliable.

The model on the Northeast Corridor

The Northeast Corridor connects four metropolitan areas: Boston (8 million people), New York (22), Philadelphia (7), Washington (10). All populations cover combined statistical areas, just as the metropolitan area definitions in Japan are expansive and include faraway exurbs. In the Northeast, the CSAs lump together some independent metro areas, such as Baltimore-Washington, but the largest of the subsidiary metro areas, including Baltimore, Providence, New Haven, and Trenton, are along the Northeast Corridor and would get their own stations.

The distances are 360 km Boston-New York, 140 km New York-Philadelphia, 220 km Philadelphia-Washington. I am not going to take into account subsidiary stations in passenger-km calculations, for simplicity’s sake. Splitting Baltimore apart from Washington would actually raise ridership by a little, first because the 0.8 exponent means that combining metro areas reduces ridership, and second because Boston-bound ridership is higher if we assume the destination is a little bit closer.

The highest-ridership city pair is New York-Washington. Per the formula above, we get

By the same formula, New York-Boston is 18.77 million, New York-Philadelphia is 16.87 million, Washington-Philadelphia is 8.98 million, and Boston-Philadelphia is 7.51 million. All of these are within the 500 km limit in which we assume distance doesn’t matter. Finally, Boston-Washington is

Overall, this is 79.4 million annual passengers, excluding shorter-distance commuter travel like New York-New Haven. Taking distance traveled into account, this is 26.4 billion annual p-km, generating $1.7 billion of operating profit. What I think it should cost to generate this service is investments that, with good value engineering that has been missing from all plans in the last 12 or so years, should cost in the low teens, say $13 billion. If costs can be held to $13 billion, or just less than $20 million per kilometer for a line of which about two-thirds of the physical infrastructure is good enough, then the financial return on investment is 13%. Not bad.

Of note, traffic density is fairly symmetric at the two ends. At the southern end, between Philadelphia and Washington, total traffic density is 36.24 million passengers per year; at the northern end, between New York and Boston, it is 31.1 million. So there should be some extra trains just for New York-Philadelphia, where the expected traffic density is 51.64 million – perhaps ones diverting west to inland Pennsylvania, perhaps interregional trains making an extra stop or two running 5-10 minutes slower than the trains to Washington – but otherwise trains should run on the entire corridor from Boston to Washington.

Also of note, I don’t expect much peakiness on the line – probably none outside the New York-Philadelphia segment. Short-distance lines, including New York-New Haven and New York-Philadelphia, have a rush hour peak in travel. But longer-range intercity lines generate weekend leisure travel and same-day business travel, both of which tend to peak outside the regular rush hour; TGV traffic, heavily weighted toward longer-range city pairs, peaks on Friday and Sunday, with weaker weekday ridership to balance it out. The Northeast Corridor thus benefits from mixing cities at various ranges, with the various peaks mostly canceling each other out. It’s plausible to get away with running service at a regular interval of every 15 minutes all day, with extra trains on New York-Philadelphia.

The Northeast Corridor and Metcalfe’s law

Two examples of Metcalfe’s law in action can be found on the corridor, one for an expansion and one for a contraction.

The contraction would be to ignore Boston and just focus on New York-Washington. The traffic density is higher there, for one. Moreover, no extensive civil infrastructure is required, only some small fixes in Maryland and New Jersey, a rebuild of the catenary, and rebuilds of the station throat interlockings. However, this is less prudent than it seems, because Boston doesn’t just generate traffic on New York-Boston, but also on New York-Washington, on trains bound from points south of New York to Boston.

If we exclude Boston, we have just three city pairs on what is left: New York-Washington, New York-Philadelphia, Washington-Philadelphia. They total 48.3 million passengers per year and 12.4 billion p-km – in other words, slightly less than half the p-km of the entire line including Boston. What’s more, there’s an extra fudge factor, not modeled in my ridership screen, coming from peakiness: a shorter line is one with a more prominent rush hour peak, as the longer trips on Boston-Washington are not included, and this ends up requiring more rush hour-only equipment and increases operating expenses per p-km.

The expansion is, in this section, one that is almost part of the Northeast Corridor today: New Haven-Springfield. The line is unelectrified today despite substantial investment by Connecticut, which like other American states is allergic to rail electrification for reasons that are beyond me. Speeds today are low, even though the right-of-way is straight. However, investment in bypasses and in speedups on the highest-quality legacy segment is possible, and would connect Hartford and Springfield to New York and points south.

The Hartford-Springfield region has 2 million people, and Springfield is 100 km from New Haven and 210 from New York. We apply our usual model and get New York-Springfield ridership of 6.19 million, Philadelphia-Springfield ridership of 2.48 million, and Washington-Springfield ridership of 3.3 million. In passenger-kilometers, these three city pairs amount to 1.3 billion, 620 million, and 1.55 billion respectively, for a total of 3.47 billion, which I will round to 3.5 billion to avoid giving the impression that the model is reliable to 3 significant figures (or even 2, to be honest).

So we have 3.5 billion additional p-km for just 100 km of new construction, or 35 million p-km per km of construction. Note that the expected density on New Haven-Springfield based on the model is just 12 million passengers – the remaining p-km are on the core Northeast Corridor, as passengers from New York and points south travel on a portion of the corridor to get up to the branch to Springfield. So even though the expected traffic is very light, the impact on revenue per kilometer of construction is comparable to that of the base corridor. If costs can be held to $2 billion, which is low-end for an entirely greenfield line but reasonable for service that would partly run on the existing legacy line, then the return on investment is $0.065*3.5/$2 = 11%, almost as high as on the base Northeast Corridor.

Further extensions

Portland (0.7)

To the north, it is valuable to run upgraded legacy trains between Boston and Portland, with a short connection to high-speed trains at South Station. Estimating ridership and revenue there is dicier, because the trains are slower and the data is trained on high-speed trains. We assume 190 km of revenue, as is the current length of the line. But costs and the ridership-suppressing effect of distance are charged at 350 km, roughly scaled for time.

With this in mind, ridership on Boston-Portland is 1.19 million, ridership on New York-Portland is 1.33 million, ridership on Philadelphia-Portland is 0.37 million, and ridership on Washington-Portland is 0.31 million. In total, this is about 1.5 billion p-km, of which 45 million, all from Washington, are beyond the 770 km at which fares are $0.135/km and are charged at the lower rate of $0.07/km. Altogether it’s around $200 million a year in revenue. Costs are around $140 million, including extra costs for service south of Boston. Operating profits are fairly low, but Boston-Portland legacy trains don’t cost per km nearly as much as high-speed rail; electrification and some track work can be done for maybe $600 million, for an ROI of 10%.

Of course, this ROI does not exist without high-speed rail the Northeast Corridor and without the separately-charged North-South Rail Link for local and regional trains. Like other tails, Boston-Portland is valuable once the mainline preexists – it isn’t so great on its own.

The South

The route from Washington to Atlanta has a sequence of cities roughly following the I-85 corridor. They are small and sprawly, but are still valuable to connect thanks to Metcalfe’s law. These include Richmond (1, and 180 km from Washington), Raleigh (2, and 240 km from Richmond), the Piedmont Triad (1.6, 120 km), Charlotte (2.6, 150 km), Greenville (1.4, 160 km), and finally Atlanta (7, 230 km).

The line is long, 50% longer than the Northeast Corridor. With quite sprawly cities in North Carolina and few good rights-of-way, takings and viaducts are needed and would raise construction costs, to perhaps $30 billion. Moreover, there is probably an intercity rail ridership penalty because these cities do not have public transportation; the model does not incorporate such a penalty, which should be regarded as a risk with investments made appropriately. And yet, each city in sequence generates ridership on the line to its north, creating decent ROI if we assume the model applies literally.

Take Richmond. It’s a small city, generating 1.89 million annual riders to Washington, 1.42 million to Philadelphia, 3.05 million to New York, 0.49 million to Boston. But this is 2.9 billion p-km for just 180 km of new construction, and nearly all of these p-km are chargeable at the full rate, giving us a total of $190 million in annual operating profit. If construction can be kept to $5 billion, this is just short of 4% ROI, which is not amazing but is decent for how small Richmond is compared with the cities to its north.

This calculation cascades farther south. We have the following table of ridership levels, in millions of annual passengers as always:

| City N\City S |

Richmond |

Triangle |

Triad |

Charlotte |

Greenville |

Atlanta |

| Boston |

0.49 |

0.66 |

0.36 |

0.43 |

0.21 |

0.58 |

| New York |

3.05 |

3.14 |

1.6 |

1.73 |

0.79 |

2.03 |

| Philadelphia |

1.42 |

1.87 |

0.9 |

0.92 |

0.41 |

1.13 |

| Washington |

1.89 |

3.3 |

2.36 |

2.13 |

0.86 |

1.92 |

| Richmond |

– |

0.64 |

0.44 |

0.62 |

0.22 |

0.44 |

| Triangle |

– |

– |

0.76 |

1.12 |

0.68 |

1.42 |

| Triad |

– |

– |

– |

0.94 |

0.57 |

1.78 |

| Charlotte |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.84 |

3.06 |

| Greenville |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1.9 |

This leads to the following operating profits, in millions of dollars per year:

| City N\City S |

Richmond |

Triangle |

Triad |

Charlotte |

Greenville |

Atlanta |

| Boston |

24.5 |

33 |

18 |

21.5 |

10.5 |

29 |

| New York |

107.06 |

157 |

80 |

86.5 |

39.5 |

101.5 |

| Philadelphia |

36.92 |

77.79 |

44.46 |

46 |

16.5 |

56.5 |

| Washington |

22.11 |

90.09 |

82.84 |

95.53 |

43 |

96 |

| Richmond |

– |

9.98 |

10.3 |

20.55 |

9.58 |

88 |

| Triangle |

– |

– |

5.93 |

19.66 |

19.01 |

60.92 |

| Triad |

– |

– |

– |

9.17 |

11.49 |

62.48 |

| Charlotte |

– |

– |

– |

– |

8.74 |

77.57 |

| Greenville |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

19.76 |

This totals to $1.8 billion a year, or an ROI of 6%. This is not a safe number – a hefty share of the figure comes from city pairs that trains would connect in 3.5+ hours, like New York-Charlotte, Washington-Atlanta, and even the 5.5-hour New York-Atlanta, in which range the model has essentially two data points (Tokyo-Hiroshima, Paris-Nice). Another noticeable share comes from intra-South connections, in which neither city in the pair has a strong center or a public transport network to connect the station with destinations.

But thankfully, because this line can build itself up by accretion of extensions, starting with Washington-Raleigh and seeing how ridership holds up would not create a white elephant, just missed benefits if the model is in fact correct.

Harrisburg (0.7), Pittsburgh (2.5), and Cleveland (3)

The Keystone corridor is an interesting example of a branch that gets stronger if it is longer. The reason for this is that Harrisburg is pretty small, and Harrisburg-Pittsburgh requires painful tunneling across the Appalachians. Philadelphia-Harrisburg is 170 km and can probably be done for $4 billion; Harrisburg-Pittsburgh is 280 km and, as a pure guess, requires around 40 kilometers of tunnel, let’s say $14 billion. Pittsburgh-Cleveland is 200 km and may require some tunneling near the Pittsburgh end to bypass suburban sprawl without good rights-of-way, but not too much – figure it for $6 billion.

For the benefits, we make a table similar to that for the South, but smaller. Of note, Washington-Harrisburg is 390 km and about 1:45, and costs accordingly to operate, but can only charge for 220 km, or $30, barely more than breakeven rate, because the straight line distance is short and high fares may not be competitive with driving on I-83. The straight line distance is even shorter than 220, about 190 via Baltimore, but Washington-Philadelphia is 220. Trains from Washington are assumed to earn the usual marginal profit west of Harrisburg, $0.065/km up to a maximum of $50, which is not reached even in Cleveland.

Finally, note that Cleveland has a big difference between the population of the core metro area (2 million) and the combined one (3.5), like Boston and Washington. Here we don’t take the bigger population but split the difference, since the biggest subsidiary regions in the combined area, Akron and Canton, could plausibly be on the line – and if they’re not then the line can serve Youngstown (0.7), and then  . Note, finally, that Boston-Cleveland is faster via Albany and Buffalo, so the line through Pittsburgh is not considered even if it is built first.

. Note, finally, that Boston-Cleveland is faster via Albany and Buffalo, so the line through Pittsburgh is not considered even if it is built first.

| City E\City W |

Harrisburg |

Pittsburgh |

Cleveland |

| Boston |

0.66 |

0.91 |

– |

| New York |

2.67 |

5.32 |

3.43 |

| Philadelphia |

1.07 |

2.96 |

2.03 |

| Washington |

1.42 |

2.19 |

1.51 |

| Harrisburg |

– |

0.47 |

0.54 |

| Pittsburgh |

– |

– |

1.5 |

And as before, using the special malus for the roundabout Washington-Harrisburg route, we have the following operating revenues in millions of annual dollars:

| City E\City W |

Harrisburg |

Pittsburgh |

Cleveland |

| Boston |

28.74 |

45.5 |

– |

| New York |

53.8 |

204.02 |

171.5 |

| Philadelphia |

11.82 |

86.58 |

85.77 |

| Washington |

3.41 |

45.11 |

50.74 |

| Harrisburg |

– |

8.55 |

16.85 |

| Pittsburgh |

– |

– |

19.5 |

Note that the relatively easy to build segment to Harrisburg only generates $98 million in operating profit on $4 billion in construction costs, just less 2.5% ROI – Harrisburg is almost as big as Richmond, but it’s a branch and not a direct extension. Then Pittsburgh generates $390 million on $14 billion, or 2.8%. But Cleveland, easier to build to and bigger than Pittsburgh, manages to generate $344 million on $6 billion, finally a respectable ROI of 6%.

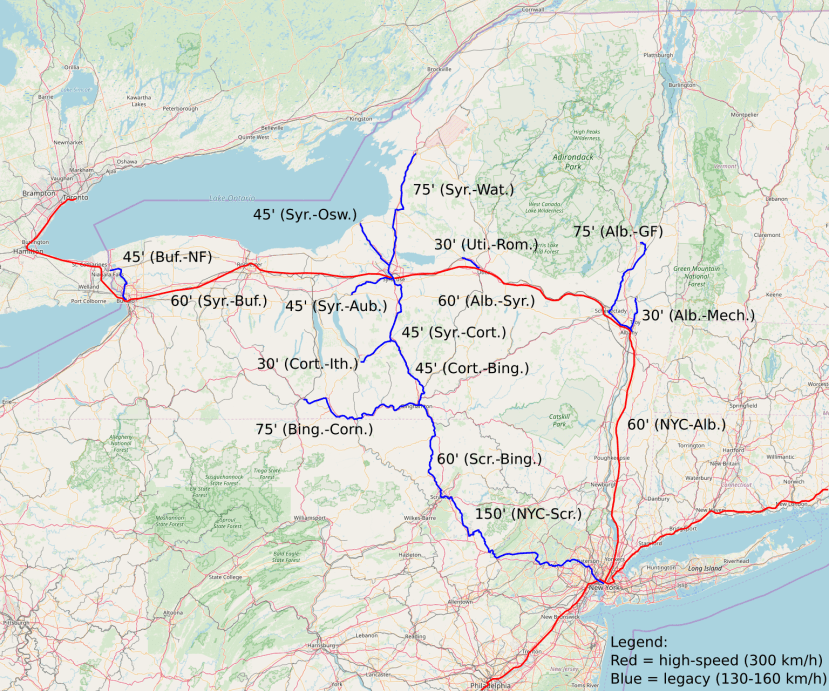

The northern cross

What may be caled the northern cross or the Albany cross – that is, a cruciform system consisting of lines from Albany to New York, Boston, Montreal, and Toronto – is an interesting case of a system where Metcalfe’s law again applies and encourages going big rather than small.

To apply the model, we make a crucial assumption: the same formula calibrated to domestic travel works internationally. Eurostar severely underperforms it – it has 10 million annual riders, of whom around 7-8 million go between London and Paris, where the formula predicts 18 million. Eurostar fares are very high, and has mandatory security theater and a slow boarding process that breaks down at peak travel time, and this may be enough to explain the low ridership. But then again, domestic TGVs overperform the model.

We also make a secondary assumption: fares charged are for actual distance traveled, even though the New York-Toronto routing isn’t the most direct.

We start with the New York-Toronto leg by itself. It connects New York to Albany (1.2, 220 km), Utica (0.3, 140 km from Albany), Syracuse (0.8, 80 km), Rochester (1.1, 120), Buffalo (1.2, 110), and Toronto (8, 160 km). Toronto’s metro population ranges between 6 million and 9 million depending on definition, and the high-end figure of 8 million is justifiable by the fact that Niagara Falls and Hamilton are on the line.

| City S\City N |

Albany |

Utica |

Syracuse |

Rochester |

Buffalo |

Toronto |

| Washington |

1.63 |

0.35 |

0.62 |

0.6 |

0.52 |

1.76 |

| Philadelphia |

1.65 |

0.54 |

0.88 |

0.78 |

0.63 |

2 |

| New York |

4.12 |

1.36 |

2.67 |

3.06 |

2.29 |

6.81 |

| Albany |

– |

0.13 |

0.26 |

0.37 |

0.4 |

1.23 |

| Utica |

– |

– |

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.6 |

| Syracuse |

– |

– |

– |

0.24 |

0.26 |

1.19 |

| Rochester |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0.37 |

1.71 |

| Buffalo |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1.83 |

And in operating profit:

| City S\City N |

Albany |

Utica |

Syracuse |

Rochester |

Buffalo |

Toronto |

| Washington |

61.45 |

16.38 |

31 |

30 |

26 |

88 |

| Philadelphia |

38.61 |

17.55 |

33.18 |

35.49 |

31.5 |

100 |

| New York |

58.92 |

31.84 |

76.36 |

109.4 |

99.73 |

340.5 |

| Albany |

– |

1.18 |

3.72 |

8.18 |

11.7 |

48.77 |

| Utica |

– |

– |

0.47 |

2.03 |

3.13 |

18.33 |

| Syracuse |

– |

– |

– |

1.87 |

3.89 |

30.17 |

| Rochester |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2.65 |

30.01 |

| Buffalo |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

19.03 |

New York-Albany should cost maybe $5 billion to build and generates $160 million a year in operating profit, just 3.2%. But Albany-Buffalo, for around $11 billion extra, generates $580 million, about 5.2%. And then Buffalo-Toronto, assuming no international penalty, should cost on the order of $3 billion (much of the line in the Toronto suburbs automatically follows from the ongoing electrification project) and generate $670 milion. So the last segment, Buffalo-Toronto, returns around 20% if New York-Buffalo preexists; even if there’s a serious international malus, the ROI is very high. Everything combined is around 7%.

None of this is robust. The model handwaves the forced transfer at Penn Station – through-service from points south to Albany and points north would be excellent given expected traffic levels, but the approaches to both Albany and Philadelphia point west. The model also assumes New York-Toronto fares are in line with rail distance, even though the route is 50% longer by rail than by air. Finally, it assumes no international penalty. A 7% ROI is robust to any one of these assumptions failing, but if all fail, the route drops in profitability.

Or, rather, the base route does. Just as completing Buffalo-Toronto makes New York-Buffalo seem far stronger, so do the two additional legs of the northern cross strengthen the initial Empire Corridor. Here’s the Boston-Albany leg, at 260 km, with Springfield at kp 135, recalling that Hartford and Springfield count as one region of 2 million:

| City W\City E |

Boston |

Springfield |

| Springfield |

2.76 |

– |

| Albany |

1.83 |

0.6 |

| Utica |

0.6 |

0.2 |

| Syracuse |

1.32 |

0.44 |

| Rochester |

1.19 |

0.56 |

| Buffalo |

0.91 |

0.46 |

| Toronto |

2.76 |

1.28 |

And in revenue:

| City W\City E |

Boston |

Springfield |

| Springfield |

24.22 |

– |

| Albany |

30.93 |

4.88 |

| Utica |

15.6 |

3.45 |

| Syracuse |

41.18 |

9.87 |

| Rochester |

46.41 |

16.93 |

| Buffalo |

45.5 |

17.19 |

| Toronto |

138 |

61.15 |

$450 million a year, of which nearly half comes out of connecting Toronto to Massachusetts and Hartford, is not a lot, but then constructing 260 km of high-speed rail is not that expensive either; my best guess is around $7 billion, with some tunnels between Springfield and the summit to the west but also some approaches at both ends that would already exist. This is 6.4% ROI, which is better than New York-Toronto gets without the assistance of Philadelphia and Washington even though that route connects to a bigger city and requires less tunneling.

The final leg of the northern cross is to Montreal (4, 370 km from Albany), and is the most speculative. If the model has an international malus, it may well apply here, crossing not just a national border but also a linguistic one. It may apply with no or limited penalty, if the underperformance of Eurostar can be ascribed entirely to fares; but if it applies and is serious, then there is less cushion for mistakes than there is for trains to Toronto. The only intermediate city is Burlington (0.2, kp 220 from Albany), which exists largely for state-level completeness. Note also that Buffalo-Montreal is faster via Toronto and is thus omitted, while Buffalo-Burlington would have third-order impact.

| City ESW\City N |

Burlington |

Montreal |

| Washington |

0.2 |

1.59 |

| Philadelphia |

0.29 |

2.02 |

| New York |

0.98 |

7.74 |

| Albany |

0.1 |

1.05 |

| Boston |

0.44 |

3.02 |

| Springfield |

0.14 |

1.58 |

| Utica |

0.03 |

0.33 |

| Syracuse |

0.06 |

0.49 |

| Rochester |

0.07 |

0.5 |

| Burlington |

– |

0.25 |

And in operating revenue:

| City ESW\City N |

Burlington |

Montreal |

| Washington |

10 |

31.8 |

| Philadelphia |

10.93 |

95.85 |

| New York |

28.03 |

296.83 |

| Albany |

1.43 |

25.25 |

| Boston |

13.73 |

123.67 |

| Springfield |

3.14 |

50.84 |

| Utica |

0.7 |

10.94 |

| Syracuse |

1.72 |

18.79 |

| Rochester |

2.55 |

23.08 |

| Burlington |

– |

2.44 |

This is $750 million a yeer, of which Burlington furnishes about 10%, and New York-Montreal about 40%. This isn’t bad ROI – about $10 billion is a reasonable construction cost – but since 90% of it is about Montreal, any serious international or interlinguistic penalty leads to a big drop in profitability. Worse, if traffic drops, there may be a frequency-ridership spiral – I am writing timetables assuming half-hourly frequency, which is just enough for the model’s projected 18 million passengers per year, but if ridership is off by a factor of more than 2, then hourly frequencies start taking a bite out of the nearer markets and trains start running less full.

Lines that do not touch the Northeast Corridor

In the previous sections, I’ve argued in favor of building out a high-speed rail network out of the Northeast Corridor, on the grounds that extensions would be profitable toward Pittsburgh-Cleveland, Montreal, Buffalo-Toronto, and Atlanta. What about other lines?

The answer is that lines that do not feed into the Northeast somehow are a lot weaker. California can get decent ridership out of Los Angeles-San Francisco and thence extensions to Sacramento and San Diego are pretty strong, but the traffic density per the model is both well below California HSR Authority projections and well below the Northeast Corridor.

And it gets worse in parts of the country without a Los Angeles-size city anchoring everything. Texas is currently building a Dallas (8)-Houston (7) high-speed line, using private money by Texas Central, a railroad owned by JR Central using Shinkansen technology. The model predicts 7.5 million annual riders between the two regions, and the system’s public ridership projections for the near term are pretty close. Moreover, construction costs are pretty high, $15 billion for 380 km, despite the flat terrain. If the operating costs and fares are what I’m projecting, the financial ROI is 1.2%.

What’s more, Texas can expect ridership to underperform any model trained on European or Japanese cities. Tokyo has the world’s largest central business district, and maintains high density of destinations at a distance of several kilometers from Tokyo Station as well, and 20-something rapid transit lines depending on how one counts feed this center. Paris is smaller but has a strong center and urban rail connections. The provincial cities in both countries are lower-density and have higher car ownership, but that’s still okay, because people from those cities are not driving into the capital. By the same token, trains to New York should not underperform a model trained on Japan, Spain, or France. But Texas is completely different, with very weak centers, no public transportation to speak of, and no walkable cores near the train stations. The penalty for poor public transport connections is likely to be serious.

The situation in the Midwest is more hopeful than in Texas, but still dicey. Chicago just isn’t that big. Yes, it’s about the same size as Paris, but the cities ringing it don’t form neat lines the way Lyon and Marseille are on the same line out of Paris, just with a short spur rather than through-service.

The funniest thing about the Midwest is that high-speed rail construction there may be justifiable as an accretion of western extensions from the Northeast and Keystone Corridors. Cleveland-Detroit (5) is 280 km long, and would put Detroit 1,070 km and slightly more than 4 hours away from New York. The distance penalty is hefty, but 2.81 million annual users is still a lot over such distance, and the $140 million in operating profits get to around 2.5% ROI on construction costs in flat Midwestern land, without taking any other connections into consideration: Chicago-Cleveland, Chicago-Detroit, Philadelphia-Detroit, Pittsburgh-Detroit, New York-Toledo, Washington-Detroit.

Even New York-Chicago is a fairly solid line per the model: it’s 1,340 km and slightly longer than 5 hours, but there is still a lot of travel volume between the two cities, mostly by air. The model says 3.12 annual high-speed rail riders, somewhat fewer than the current O&D flight volume (4.68 million annualized from 2018 Q2), which is believable by comparison with Paris-Nice’s mode share (70% air, 30% rail, ignoring all other modes). The required mode share is still more favorable to rail, but the airports in New York and Chicago have more congestion and more delays than in Nice, turning what is a little more than an hour in the air into a three-hour flight schedule.

In contrast, just starting from Chicago-Cleveland (550 km)/Detroit (470 km), without any other connections (and without Pittsburgh-Cleveland), would not be financially great. Ignoring Toledo, the three cities generate 13 million annual riders, 6 billion annual p-km, and $400 million in annual operating income, for a system that would take perhaps $13 billion to construct, perhaps slightly more.

What this means for high-speed rail construction

Metcalfe’s law implies that high-speed rail networks get stronger as they add more nodes, even if those nodes are somewhat weaker than the initial ones. But it gives guideines for how to build such networks more broadly:

- Don’t cheap out by only building a short segment.

- Once the initial segment is in place, invest in extending it and building branches off it as soon as possible, in preference to building unconnected segments elsewhere.

- A relatively empty tail may still be financially successful if it fills a trunk line.

- Unless all your cities are on one line, try to build a mesh of lines to allow many origin-destination pairs.

- You’ll always run into a frontier of marginal lines, so value-engineer infrastructure as much as possible to push that frontier forward.

- Be wary of lines for which the analysis involves extrapolation, for example if neither city has a strong center or usable public transport.

High-speed rail is cheap to run when there’s enough scale to fill trains – high speeds ensure that labor and equipment cost per seat-km are fairly low. This means that self-sustaining profits are viable, and once they’re in place, they can generate further borrowing capacity for rapid expansion.

The limit is not the sky. Beyond a certain point, no realistic value engineering can make lines financially viable. Sometimes the cities are just too small or too far apart. But a realistic limit for the United States is still most likely much farther than anyone proposing immediate investment plans thinks: the Northeast Corridor can generate good returns if investment there is ever done competently, and branches and extensions to smaller and less dense cities are still more viable than they look at first glance.