An article by Ben Hopkinson at Works in Progress is talking about what Madrid has been doing right to build subways at such low costs, and is being widely cited. It sounds correct, attributing the success to four different factors, all contrasted with the high-cost UK. The first of these factors, decentralization in Spain compared with its opposite in England, is unfortunately completely wrong (the other three – fast construction, standardized designs, iterative in-house designs – are largely right, with quibbles). Even more unfortunately, it is this mistake that is being cited the most widely in the discussion that I’m following on social media. The mentality, emanating from the UK but also mirrored elsewhere in Europe and in much of the American discourse, is that decentralization is obviously good, so it must be paired with other good things like low Spanish costs. In truth, the UK shares high costs with more decentralized countries, and Spain shares low ones with more centralized ones. The emphasis on decentralization is a distraction, and people should not share such articles without extensive caveats.

The UK and centralization

The UK is simultaneously expensive to build infrastructure in and atypically centralized. There is extensive devolution in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, but it’s asymmetric, as 84% of the population lives in England. Attempts to create symmetric devolution to the Regions of England in the Blair era failed, as there is little identity attached to them, unlike Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland. Regional identities do exist in England, but are not neatly slotted at that level of the official regions – Cornwall has a rather strong one but is only a county, the North has a strong one but comprises three official regions, and the Home Counties stretch over parts of multiple regions. Much of this is historic – England was atypically centralized even in the High Middle Ages, with its noble magnates holding discontinuous lands; identities that could form the basis of later decentralization as in France and Spain were weaker.

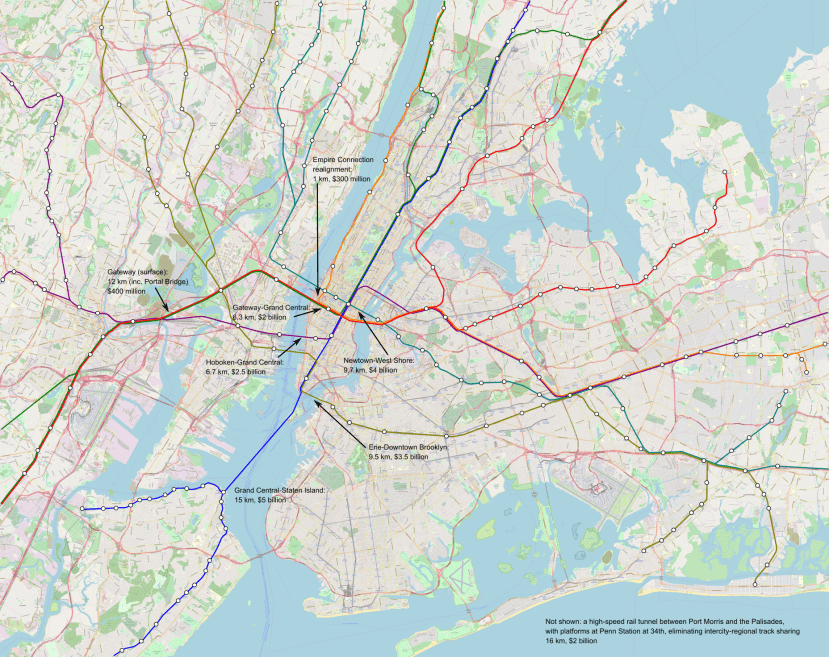

People in the UK understand that their government isn’t working very well, and focus on this centralization as a culprit; they’re aware of the general discourse from the 1960s onward, associating decentralization with transparency and accountability. After the failure of Blair-era devolution, the Cameron cabinet floated the idea of doing devolution but at lower level, to the metropolitan counties, comprising the main provincial cities, like Greater Manchester or the West Midlands (the county surrounding Birmingham, not the larger official region). Such devolution would probably be good, but is not really the relevant reform, not when London, with its extreme construction costs, already has extensive devolved powers.

But in truth, the extreme construction costs of the UK are mirrored in the other English-speaking countries. In such countries, other than the US, even the cost history of similar, rising sharply in the 1990s and 2000s with the adoption of the more privatized, contractor-centric globalized system of procurement. The English story of devolution is of little importance there – Singapore and Hong Kong are city-states, New Zealand is small enough there is little reason to decentralize there, and Canada and Australia are both highly decentralized to the provinces and states respectively. The OECD fiscal decentralization database has the UK as one of the more centralized governments, with, as of 2022, subnational spending accounting for 9.21% of GDP and 19.7% of overall spending, compared with Spain’s 20.7% and 43.6% respectively – but in Australia the numbers are 17.22% and 46.2%, and in Canada they are 27.8% and 66.5%.

American construction costs have a different history from British ones. For one, London built for the same costs as German and Italian cities in the 1960s and 70s, whereas New York was already spending about four times as much per km at the time. But this, too, is an environment of decentralization of spending; the OECD database doesn’t mention local spending, but if what it includes in state spending is also local spending, then that is 19.07% of American GDP and 48.7% of American government spending.

In contrast, low-cost environments vary in centralization considerably. Spain is one of the most decentralized states in Europe, having implemented a more or less symmetric system in response to Catalan demands for autonomy, but Italy is fairly centralized (13.9% of GDP and 24.8% of government spending are subnational), and Greece and Portugal are very centralized and Chile even more so (2.77%/8.1%). The OECD doesn’t include numbers for Turkey and South Korea so we can merely speculate, but South Korea is centralized, and in Istanbul there are separate municipal and state projects, both cheap.

Centralization and decisionmaking

Centralization of spending is not the same thing as centralization of decisionmaking. This is important context for Nordic decentralization, which features high decentralization of the management of welfare spending and related programs, but more centralized decisionmaking on capital city megaprojects. In Stockholm, both Citybanan and Nya Tunnelbanan were decided by the state. Congestion pricing, in London and New York a purely subnational project, involved state decisions in Stockholm and a Riksdag vote; the Alliance victory in 2006 meant that the revenue would be spent on road construction rather than on public transport.

In a sense, the norm in unitary European states like the Nordic ones, or for that matter France, is that the dominant capital has less autonomy than the provinces, because the state can manage its affairs directly; thus, RATP is a state agency, and until 2021 all police in Paris was part of the state (and the municipal police today has fewer than 10% of the total strength of the force). In fact, on matters of big infrastructure projects, the state has to do so, since the budgets are so large they fall within state purview. Hopkinson’s article complaining that Crossrail and Underground extensions are state projects needs to be understood in that context: Grand Paris Express is a state project, debated nationally with the two main pre-Macron political parties both supporting it but having different ideas of what to do with it, not too different from Crossrail; the smaller capitals of the Nordic states have smaller absolute budgets, but those budgets are comparable relative to population or GDP, and there, again, state decisionmaking is as unavoidable as in London and Paris.

The purest example of local decisionmaking in spending is not Spain but the United States. Subway projects in American cities are driven by cities or occasionally state politicians (the latter especially in New York); the federal government isn’t involved, and FTA and FRA grants are competitive and decided by people who do not build but merely regulate and nudge. This does not create flexibility – to the contrary, the separation between builders and regulators means that the regulators are not informed about the biggest issues facing the builders and come up with ideas that make sense in their heads but not on the ground, while the builders are too timid to try to innovate because of the risk that the regulators won’t approve. With this system, the United States has not seen public-sector innovation in a long while, even before it became ideologically popular to run against the government.

In finding high American costs in the disconnect between those who do and those who oversee, at multiple levels – the agencies are run by an overclass of political appointees and directly-reporting staff rather than by engineers, states have a measure of disconnect from agencies, and the FTA and FRA practice government-by-nudge – we cannot endorse any explanation of high British costs that comes from centralization.

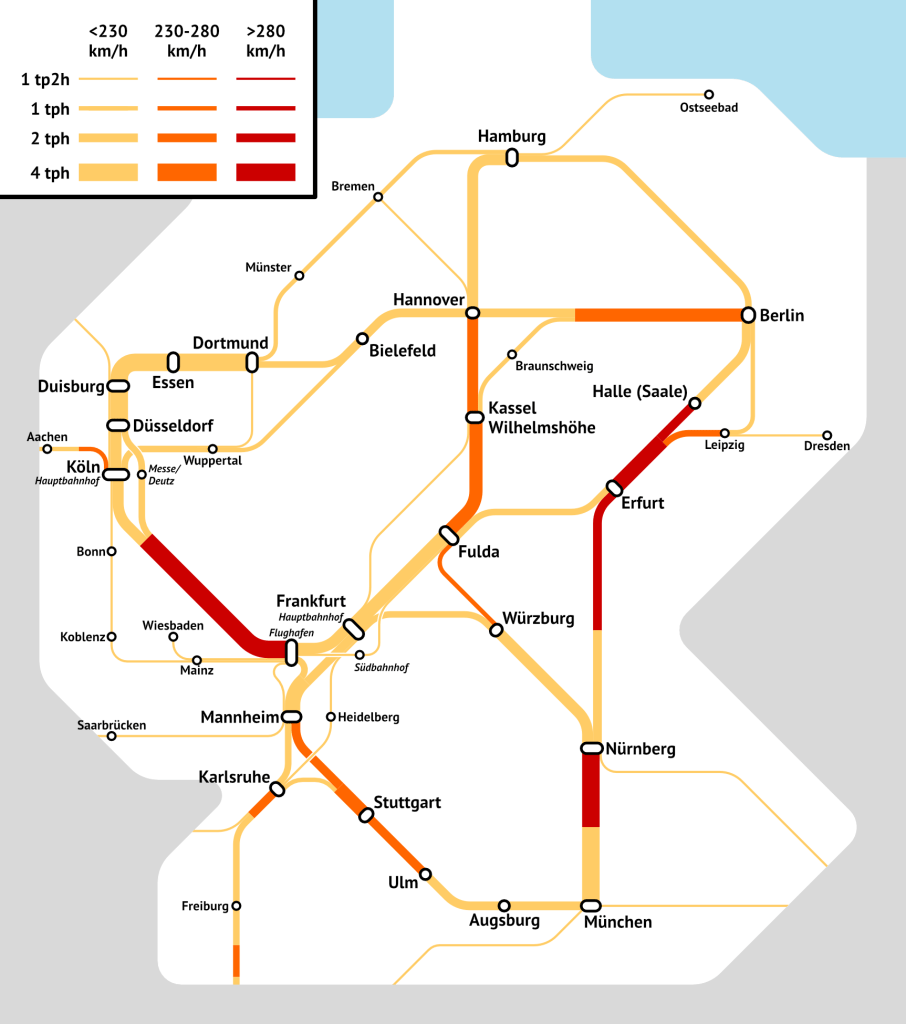

If the policy implications of such an explanation are to devolve further powers to London or a Southeast England agency, then they are likely to backfire, by removing the vestiges of expertise of doers from the British state; the budgets involves in London expansion are too high to be handled at subnational level. Moreover, reduction in costs – the article’s promise of a Crossrail 2, 3, and 4 if costs fall – has no chance of reducing the overall budget; the same budget would just be spent on further tunnels, in the same manner the lower French costs lead to a larger Grand Paris Express program. Germany and Italy in the same schema have less state-centric decisionmaking in their subway expansion, for the simple reason that both countries underbuild, which can be seen in the very low costs per rider – a Berlin with the willingness to build infrastructure of London or Paris would have extended U8 to Märkisches Viertel in the 1990s at the latest.

One possible way this can be done better is if it’s understood in England that decentralization only really works in the sense of metropolitanization in secondary cities, where the projects in question are generally below the pay grade of state ministers or high-level civil servants. In the case of England, this would mean devolution to the metropolitan counties, giving them the powers that Margaret Thatcher instead devolved to the municipalities. But that, by itself, is not going to reduce costs; those devolved governments would still need outside expertise, for which public-sector consultants, in the British case TfL, are necessary, using the unitariness of the state to ensure that the incentives of such public-sector consultants are to do good work and push back against bad ideas rather than to just profit off of the management fees.

The first-line effect

The article tries to argue for decentralization so much it ends up defending an American failure, using the following language:

But the American projects that are self-initiated, self-directed, self-funded, self-approved, and in politically competitive jurisdictions do better. For example, Portland, Oregon’s streetcar was very successful at regenerating the Pearl District’s abandoned warehouses while being cutting-edge in reducing costs. Its first section was built for only £39 million per mile (inflation adjusted), half as much as the global average for tram projects.

To be clear, everything in the above paragraph is wrong. The Portland Streetcar was built for $57 million/4 km in 1995-2001, which is $105.5 million/4 km in 2023 dollars, actually somewhat less than the article says. But $26.5 million/km was, in the 1990s, an unimpressive cost – certainly not half as much as the global average for tram projects. The average for tram projects in France and Germany is around 20 million euros/km right now; in 2000, it was lower. So Portland managed to build one very small line for fairly reasonable costs, but they were not cutting edge; this is a common pattern to Western US cities, in that the first line has reasonable costs and then things explode, even while staying self-funded and self-directed. Often this is a result of overall project size – a small pilot project can be overseen in-house, and then when it is perceived to succeed, the followup is too large for the agency’s scale and then things fall apart. Seattle was building the underground U-Link for $457 million/km in 2023 dollars; the West Seattle extension, with almost no tunneling, is budgeted at $6.7-7.1 billion/6.6 km, which would be a top 10 cost for an undeground line, let alone a mostly elevated one. What has changed in 15 years since the beginning of U-Link isn’t federal involvement, but rather the scope of the program, funded by regional referendum.

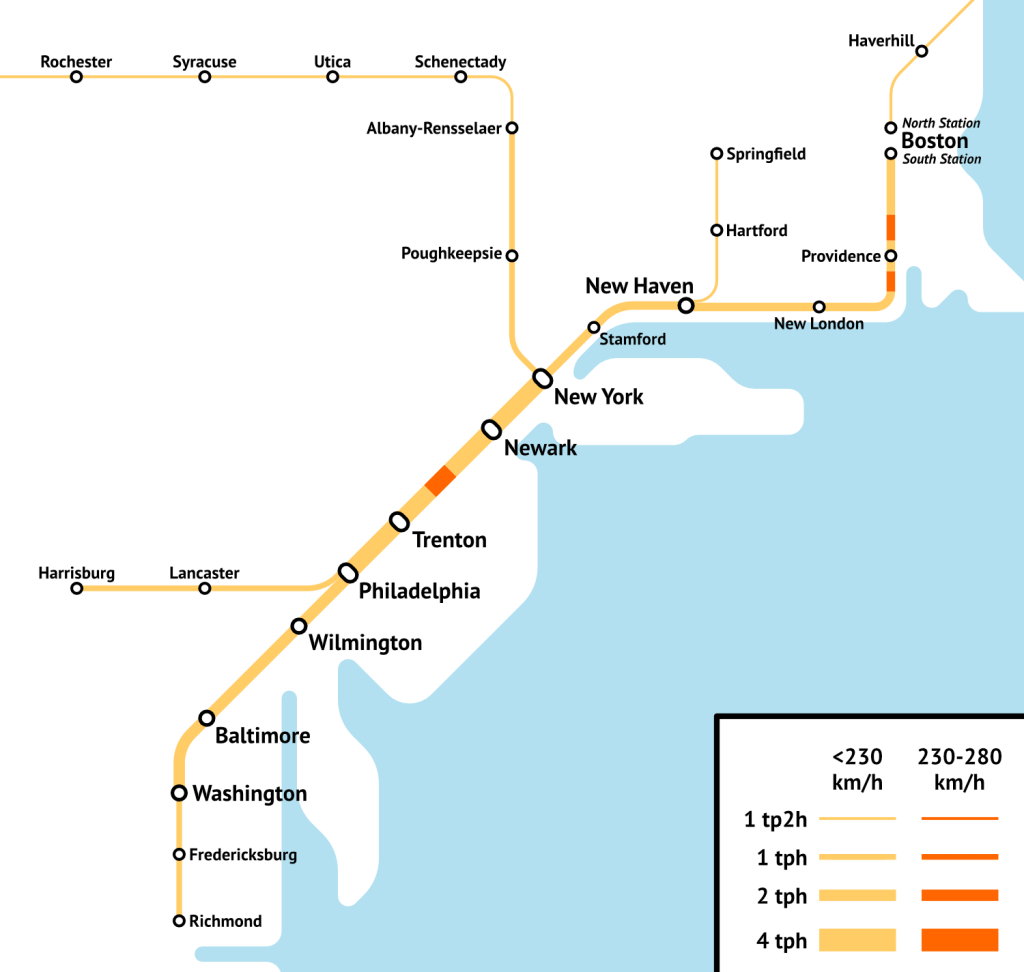

The truth is that there’s nothing that can be learned from American projects within living memory except what not to do. There’s always an impulse to look for the ones that aren’t so bad and then imitate them, but they are rare and come from a specific set of circumstances – again, first light rail lines used to be like this and then were invariably followed by cost increases. But the same first-line effect also exists in the reasonable-cost world: the three lowest-cost high-speed rail lines in our database built to full standards (double track, 300+ km/h) are all first lines, namely the Ankara-Konya HST ($8.1 million/km in 2023 PPPs), the LGV Sud-Est ($8.9 million/km), and the Madrid-Seville LAV ($15.4 million/km); Turkey, Spain, and France have subsequently built more high-speed lines at reasonable costs, but not replicated the low costs of their first respective lines.

On learning from everyone

I’ve grown weary of the single case study, in this case Madrid. A single case study can lead to overlearning from the peculiarities of one place, where the right thing to do is look at a number of successes and look at what is common to all of them. Spain is atypically decentralized for a European state and so the article overlearns from it, never mind that similarly cheap countries are much more centralized.

The same overall mistake also permeates the rest of the article. The other three lessons – time is money, trade-offs matter and need to be explicitly considered, and a pipeline of projects enables investment in state capacity, are not bad; much of what is said in them, for example the lack of NIMBY veto power, is also seen in other low-cost environments, and is variable in medium-cost ones like France and Germany. However, the details leave much to be desired.

In particular, one the tradeoffs mentioned is that of standardization of systems, which is then conflated with modernization of systems. The lack of CBTC in Madrid is cited as one way it kept construction costs down, unlike extravagant London; the standardized station designs are said to contrast with more opulent American and British ones. In fact, neither of these stories is correct. Manuel Melis Maynar spoke of Madrid’s lack of automation as one way to keep systems standard, but that was in 2003, and more recently, Madrid has begun automating Line 6, its busiest; for that matter, Northern Europe’s lowest-construction cost city, Nuremberg, has automated trains as well. And standardized stations are not at all spartan; the lack of standardization driving up costs is not about nice architecture, which can be retrofitted rather cheaply like the sculptures and murals that the article mentions positively, but behind-the-scenes designs for individual system components, placement of escalators and elevators, and so on.

The frustrating thing about the article, then, is that it is doing two things, each of which is suspect, the combination of which is just plain bad. The first is that it tries to overlearn from a single famous case. The second is that it isn’t deeply aware of this case; reading the article, I was stricken by how nearly everything it said about Madrid I already knew, whereas quite a lot of what it said about the UK I did not, as if the author was cribbing off the same few reports that everyone in this community has already read and then added original research not about the case study but about Britain.

And then the discourse, unfortunately, is not about the things in the article that are right – the introduction in lessons 2-4 into how the civil service in Madrid drives projects forward – but about the addition of the point about centralization, which is not right. Going forward, reformers in the UK need far better knowledge of how the low- and medium-construction cost world looks, both deeper and broader than is on display here.