Category: Germany

The Four Quadrants of Cities for Transit Revival

Cities that wish to improve their public transportation access and usage are in a bind. Unless they’re already very transit-oriented, they have not only an entrenched economic elite that drives (for example, small business owners almost universally drive), but also have a physical layout that isn’t easy to retrofit even if there is political consensus for modal shift. Thus, to shift travel away from cars, new interventions are needed. Here, there is a distinction between old and new cities. Old cities usually have cores that can be made transit-oriented relatively easily; new cities have demand for new growth, which can be channeled into transit-oriented development. Thus, usually, in both kinds of cities, a considerably degree of modal shift is in fact possible.

However, it’s perhaps best to treat the features of old and new cities separately. The features of old cities that make transit revival possible, that is the presence of a historic core, and those of new cities, that is demand for future growth, are not in perfect negative correlation. In fact, I’m not sure they consistently have negative correlation at all. So this is really a two-by-two diagram, producing four quadrants of potential transit cities.

Old cities

The history of public transportation is one of decline in the second half of the 20th century in places that were already rich then; newly-industrialized countries often have different histories. The upshot is that an old auto-oriented place must have been a sizable city before the decline of mass transit, giving it a large core to work from. This core is typically fairly walkable and dense, so transit revival would start from there.

The most successful examples I know of involve the restoration of historic railroads as modern regional lines. Germany is full of small towns that have done so; Hans-Joachim Zierke has some examples of low-cost restoration of regional lines. Overall, Germany writ large must be viewed as such an example: while German economic growth is healthy, population growth is anemic, and the gradual increase in the modal split for public transportation here must be viewed as more intensive reuse of a historic national rail network, anchored by tens of small city cores.

At the level of a metropolitan area, the best candidates for such a revival are similarly old places; in North America, the best I can think of for this are Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago. Americans don’t perceive any of the three as especially auto-oriented, but their modal splits are comparable to those of small French cities. But in a way, they show one way forward. If there’s a walkable, transit-oriented core, then it may be attractive for people to live near city center; in those three cities it’s also possible to live farther away and commute by subway, but in smaller ones (say, smaller New England cities), the subway is not available but conversely it’s usually affordable to live within walking distance of the historic city center. This creates a New Left-flavored transit revival in that it begins with the dense city center as a locus of consumption, and only then, as a critical mass of people lives there, as a place that it’s worth building new urban rail to.

New cities

Usually, if a city has a lot of recent growth from the era in which it has become taken for granted that mobility is by car, then it should have demand for further growth in the future. This demand can be planned around growth zones with a combination of higher residential density and higher job density near rail corridors. The best time to do transit-oriented development is before auto-oriented development patterns even set in.

There are multiple North American examples of how this works. The best is Vancouver, a metropolitan area that has gone from 560,000 people in the 1951 census to 2.6 million in the 2021 census. Ordinarily, one should expect such a region to be entirely auto-oriented, as most American cities with almost entirely postwar growth are; but in 2016, the last census before corona, it had a 20% work trip modal split, and that was before the Evergreen extension opened.

Vancouver has achieved this by using its strong demand for growth to build a high-rise city center, with office towers in the very center and residential ones ringing it, as well as high-density residential neighborhoods next to the Expo Line stations. The biggest suburbs of Vancouver have followed the same plan: Burnaby built an entirely new city center at Metrotown in conjunction with the Expo Line, and even more auto-oriented Surrey has built up Whalley, at the current outer terminal of the line, as one of its main city centers. Housing growth in the region is rapid; YIMBY advocacy calls for more, but the main focus isn’t on broad development (since this already happens) but on permitting more housing in recalcitrant rich areas, led by the West Side, which will soon have its Broadway extension of the Millennium Line.

Less certain but still interesting examples of the same principle are Calgary, Seattle, and Washington. Calgary, a low-density city, planned its growth around the C-Train, and built a high-rise city center, limiting job sprawl even as residential sprawl is extensive; Seattle and the Virginia-side suburbs of Washington have permitted extensive infill housing and this has helped their urban rail systems achieve high ridership by American standards, Seattle even overtaking Philadelphia’s modal split.

The four quadrants

The above contrast of old and new cities misses cities that have positive features of both – or neither. The cities with both positive features have the easiest time improving their public transportation systems, and many have never been truly auto-oriented, such as New York or Berlin, to the point that they’re not the best examples to use for how a more auto-oriented city can redevelop as a transit city.

In North America, the best example of both is San Francisco, which simultaneously is an old city with a high-density core and a place with immense demand for growth fueled by the tech industry. The third-generation tech firms – those founded from the mid-2000s onward (Facebook is in a way the last second-generation firm, which generation began with Apple and Microsoft) – have generally headquartered in the city and not in Silicon Valley. Twitter, Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Dropbox, and Slack are all in the city, and the traditional central business district has expanded to South of Market to accommodate. This is really a combination of the consumption-oriented old-city model, as growing numbers of employees of older second-generation firms chose to live in the city and reverse-commute to Silicon Valley, and the growth-oriented new-city model. Not for nothing, the narrower metropolitan statistical area of San Francisco (without Silicon Valley) reached a modal split of 17% just before corona, the second highest in the United States, with healthy projections for growth.

But then there is the other quadrant, comprising cities that have neither the positive features of old cities nor those of new cities. To be in this quadrant, a city must not be so old as to have a large historic core or an extensive legacy rail network that can be revived, but also be too poor and stagnant to generate new growth demand. Such a city therefore must have grown in a fairly narrow period of time in the early- to mid-20th century. The best example I can think of is Detroit. The consumption-centric model of old city growth can work even there, but it can’t scale well, since there’s not enough of a core compared with the current extent of the population to build out of.

Berlin Greens Know the Price of Everything and Value of Nothing

While trying to hunt down some numbers on the costs of the three new U5 stations, I found media discourse in Berlin about the U-Bahn expansion plan that was, in effect, greenwashing austerity. This is related to the general hostility of German urbanists and much of the Green Party (including the Berlin branch) to infrastructure at any scale larger than that of a bike lane. But the specific mechanism they use – trying to estimate the carbon budget – is a generally interesting case of knowing the costs more certainly than the benefits, which leads to austerity. The underlying issue is that mode shift is hard to estimate accurately at the level of the single piece of infrastructure, and therefore benefit-cost analyses that downplay ridership as a benefit and only look at mode shift lead to underbuilding of public transport infrastructure.

The current program in Berlin

In the last generation, Berlin has barely expanded its rapid transit network. The priority in the 1990s was to restore sections that had been cut by the Berlin Wall, such as the Ringbahn, which was finally restored with circular service in 2006. U-Bahn expansion, not including restoration of pre-Wall services, included two extensions of U8, one north to Wittenau that had begun in the 1980s and a one-stop southward extension of U8 to Hermannstrasse, which project had begun in the 1920s but been halted during the Depression. Since then, the only fully new extension have been a one-stop extension of U2 to Pankow, and the six-stop extension of U5 west from Alexanderplatz to Hauptbahnhof.

However, plans for much more expansive construction continue. Berlin was one of the world’s largest and richest cities before the war, and had big plans for further growth, which were not realized due to the war and division; in that sense, I believe it is globally only second to New York in the size of its historic unrealized expansion program. The city will never regain its relative wealth or size, not in a world of multiple hypercities, but it is growing, and as a result, it’s dusting off some of these plans.

Most of the lines depicted in red on the map are not at all on the city’s list of projects to be built by the 2030s. Unfortunately, the most important line measured by projected cost per rider, the two-stop extension of U8 north (due east) to Märkisches Viertel, is constantly deprioritized. The likeliest lines to be built per current politicking are the extensions of U7 in both directions, southeast ti the airport (beyond the edge of the map) and west from Spandau to Staaken, and the one-stop extension of U3 southwest to Mexikoplatz to connect with the S-Bahn. An extension to the former grounds of Tegel is also considered, most likely a U6 branch depicted as a lower-priority dashed yellow line on the map rather than the U5 extension the map depicts in red.

The carbon critique

Two days after the U5 extension opened two years ago, a report dropped that accused the proposed program of climate catastrophe. The argument: the embedded concrete emissions of subway construction are high, and the payback time on those from mode shift is more than 100 years.

The numbers in the study are, as follows: each kilometer of construction emits 98,800 tons of CO2, which is 0.5% of city emissions (that is, 5.38 t/person, cf. the German average of about 9.15 in 2021). It’s expected that through mode shift, each subway kilometer saves 714 t-CO2 in annual emissions through mode shift, which is assumed to be 20% of ridership, for a payback time of 139 years.

And this argument is, frankly, garbage. The scale of the difference in emissions between cities with and without extensive subway systems is too large for this to be possibly true. The U-Bahn is 155 km long; if the 714 t/km number holds, then in a no U-Bahn counterfactual, Berlin’s annual greenhouse gas emissions grow by 0.56%, which is just ridiculous. We know what cities with no or minimal rapid transit systems look like, and they’re not 0.56% worse than comparanda with extensive rapid transit – compare any American city to New York, for one. Or look again at the comparison of Berlin to the German average: Berlin has 327 cars per 1,000 people, whereas Germany-wide it’s 580 and that’s with extensive rapid transit systems in most major cities bringing down the average from the subway-free counterfactual of the US or even Poland.

The actual long-term effect of additional public transport ridership on mode shift and demotorization has to be much more than 20%, then. It may well be more than 100%: the population density that the transit city supports also increases the walking commute modal split as some people move near work, and even drivers drive shorter distances due to the higher density. This, again, is not hard to see at the level of sanity checks: Europeans drive considerably less than Americans not just per capita but also per car, and in the United States, people in New York State drive somewhat shorter distance per car than Americans elsewhere (I can’t find city data).

The measurement problem

It’s easy to measure the embedded concrete of infrastructure construction: there are standardized itemized numbers for each element and those can be added up. It’s much harder to measure the carbon savings from the existence of a better urban rail system. Ridership can be estimated fairly accurately, but long-term mode shift can’t. This is where rules of thumb like 20% can look truthy, even if they fail any sanity check.

But it’s not correct to take any difficult to estimate number and set it to zero. In fact, there are visible mode shift effects from a large mass transit system. The difficulty is with attributing specific shifts to specific capital investments. Much of the effect of mode shift comes from the ability of an urban rail system to contribute to the rise of a strong city center, which can be high-rise (as in New York), mid-rise (as in Munich or Paris), or a mix (as in Berlin). Once the city center anchored by the system exists, jobs are less likely to suburbanize to auto-oriented office parks, and people are likelier to work in city center and take the train. Social events will likewise tend to pick central locations to be convenient for everyone, and denser neighborhoods make it easier to walk or bike to such events, and this way, car-free travel is possible even for non-work trips.

This, again, can be readily verified by looking at car ownership rates, modal splits (for example, here is Berlin’s), transit-oriented development, and so on, but it’s difficult to causally attribute it to a specific piece of infrastructure. Nonetheless, ignoring this effect is irresponsible: it means the carbon benefit-cost analysis, and perhaps the economic case as well, knows the cost of everything and the value of little, which makes investment look worse than it is.

I suspect that this is what’s behind the low willingness to invest in urban rail here. The benefit-cost analyses can leave too much value on the table, contributing to public transport austerity. When writing the Sweden report, I was stricken by how the benefit-cost analyses for both Citybanan and Nya Tunnelbanan were negative, when the ridership projections were good relative to costs. Actual ridership growth on the Stockholm commuter trains from before the opening of Citybanan to 2019 was enough to bring cot per new daily trip down to about $29,000 in 2021 PPP dollars, and Nya Tunnelbanan’s daily ridership projection of 170,000 means around $23,000/rider. The original construction of the T-bana cost $2,700/rider in 2021 dollars, in a Sweden that was only about 40% as rich as it is today, and has a retrospective benefit-cost ratio of between 6 and 8.5, depending on whether broader agglomeration benefit are included – and these benefits are economic (for example, time savings, or economic productivity from agglomeration) scale linearly with income.

At least Sweden did agree to build both lines, recognizing the benefit-cost analysis missed some benefits. Berlin instead remains in austerity mode. The lines under discussion right now are projected between 13,160€ and 27,200€ per weekday trip (and Märkisches Viertel is, again, the cheapest). The higher end, represented by the U6 branch to Tegel, is close to the frontier of what a country as rich as Germany should build; M18 in Paris is projected to be more than this, but area public transport advocates dislike it and treat it as a giveaway to rich suburbs. And yet, the U6 branch looks unlikely to be built right now. When the cost per rider of what is left is this low, what this means is that the city needs to build more infrastructure, or else it’s leaving value on the table.

S-Bahn Frequency and Job Centralization

Commuter rail systems with high bidirectional frequency succeed in monocentric cities. This can look weird from the perspective of rail advocacy: American rail advocates who call for better off- and reverse-peak frequency argue that it is necessary for reverse-commuters. The present-day American commuter rail model, which centers suburban commuters who work in city center between 9 am and 5 pm, doesn’t work for other workers and for non-work trips, and so advocates for modernization bring up these other trips. And yet, the best examples of modern commuter rail networks with high frequency are in cities with much job centralization within the inner areas and relatively little suburbanization of jobs. What gives?

The ultimate issue here is that S-Bahn-style operations are not exactly about the suburbs or about reverse-commutes. They’re about the following kinds of trips, in roughly descending order of importance:

- Urban commuter trips to city center

- Commuter trips to a near-center destination, which may not be right at the one train station of traditional operations

- Urban non-work trips, of the same kind as subway ridership

- Middle-class suburban commutes to city center at traditional midcentury work hours, the only market the American commuter rail model serves today

- Working-class reverse-commutes, not to any visible office site (which would tilt middle-class) but to diffuse retail, care, and service work

- Suburban work and non-work trips to city center that are not at traditional midcentury hours

- Middle-class reverse-commutes and cross-city commutes

The best example of a frequent S-Bahn in a monocentric city is Munich. The suburbs of Munich have a strong anti-city political identity, rooted in the pattern in which the suburbs vote CSU and the city votes SPD and Green and, increasingly, in white flight from the diverse city. But the jobs are in the city, so the suburbanites ride the commuter trains there, just as their counterparts in American cities like New York do. The difference is that the same trains are also useful for urban trips.

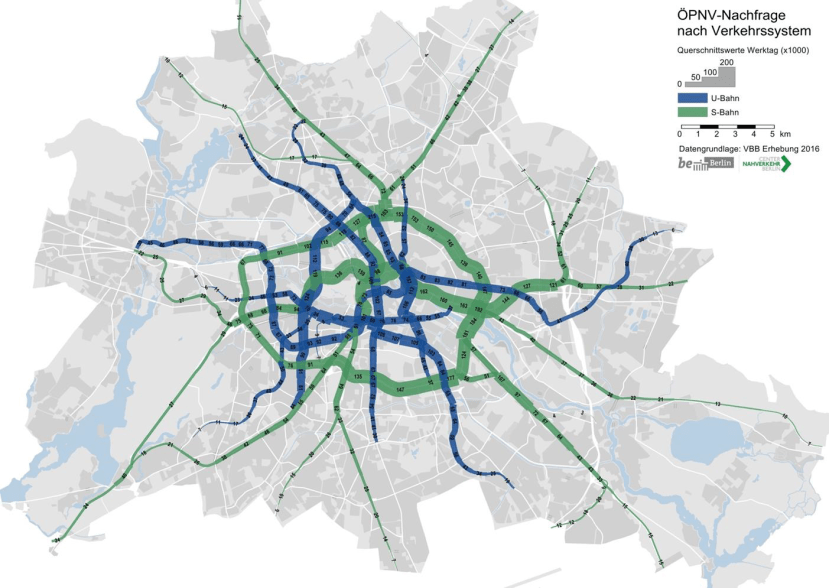

I don’t know the ridership by segment in Munich, but I do know it in Berlin, as of 2016 (source, p. 6):

Between Ostkreuz and Hauptbahnhof, just west of the meeting point with the North-South Tunnel, the east-west Stadtbahn has 160,000 daily riders. The proper suburbs are mostly less than 10,000 each, and even the more suburban neighborhoods of the city, like Wannsee, don’t contribute much. Overall, the majority of S-Bahn traffic is urban, consisting of trips taken either within the Ring or in the more urban outside-the-Ring areas, like Pankow, Steglitz, and especially Lichtenberg.

The high-frequency model of the S-Bahn works not because there is a mass of people who work in these outer areas. I don’t know the proportion of jobs in the Berlin region that are within the Ring, but I doubt it’s low. For reference, about 35% of Ile-de-France jobs are in a 100 km^2 blob (about the same area enclosed by the Ring) consisting of Paris, La Défense, and the suburbs in between. New York likewise has about 35% of metro area jobs in a 100 km^2 blob chosen to include Manhattan and the major non-Manhattan job centers like Downtown Brooklyn, Long Island City, and the Jersey City waterfront. I imagine Berlin should be the same or even somewhat higher (this proportion is inversely correlated with city population all else being equal) – Berlin is polycentric but all of its centers are on or within the Ring.

Rather, the reason the high-frequency model works is that there is a lot more ridership in urban areas than in low-density suburbs generating strictly unidirectional trips. The main users of the S-Bahn are city residents, or maybe residents of dense inner suburbs in regions with unusually tightly drawn city limits like Paris. If the highest demand is by people whose trip is 20 minutes and not 90 minutes, then the trains must run very frequently, or else they won’t ride. And if the highest demand is by people who are traveling all over the urban core, even if they travel to the central business district more than to other inner neighborhoods, then the trains must have good connections to the subway and buses and many urban stops.

In this schema, the suburbs still get good service because the S-Bahn model, unlike the traditional metro model (but like the newer but more expensive suburban metro), is designed to be fast enough that suburb-to-city trips are still viable. This way, middle-class suburbanites benefit from service whose core constituency is urban, and can enjoy relatively fast, frequent trips to the city and other suburbs all day.

I emphasize middle-class because lower-income jobs are noticeably less centralized. I don’t have any European data on this, but I do have American data. In New York, as of 2015, 57% of $40,000-a-year-and-up workers worked in Manhattan south of 60th Street, but only 37% of under-$40,000-a-year workers did. Moreover, income is probably a better way of conceptualizing this than the sociological concept of class – the better-off blue-collar workers tend to be centralized at industrial sites or they’re owner-operators with their own vans and tools and in either case they have very low mass transit ridership. The sort of non-middle-class workers who high-frequency suburban transit appeals to are more often pink-collar workers cleaning the houses of the middle class, or sometimes blue-collar workers with unpredictable work assignments, who might need cross-city transit.

In contrast, the sort of middle-class ridership that is sociologically the same as the remnants of the midcentury 9-to-5 suburban commuters but reverse-commutes to the suburbs is small. American commuter rail does take it into account: Metro-North has some reverse-peak trains for city-to-White Plains and city-to-Stamford commuters, and Caltrain runs symmetric peak service for the benefit of city-to-Silicon Valley commuters. And yet, even on Caltrain ridership is much more traditional- than reverse-peak; on Metro-North, the traditional peak remains dominant. There just isn’t enough transit-serviceable ridership in a place like Stamford the way it looks today.

So the upshot of commuter rail modernization is that it completely decenters the suburban middle class with its midcentury aspirations of living apart from the city. It does serve this class, because the S-Bahn model is good at serving many kinds of trips at once. But the primary users are urban and inner-suburban. I would even venture and presume that if, on the LIRR, the only options were business-as-usual and ceasing all service to Long Island while providing modern S-Bahn service within city limits, Long Island should be cut off and ridership would increase while operating expenses would plummet. The S-Bahn model does not force such a choice – it can serve the suburbs too, on local trains making some additional city stops at frequencies and fares that are relevant to city residents – but the primacy of city ridership means that the system must be planned from the inside out and not from the outside in.

Eno’s Project Delivery Webinar

Eno has a new report out about mass transit project delivery, which I encourage everyone to read. It compares the American situation with 10 other countries: Canada, Mexico, Chile, Norway, Germany, Italy, South Africa, Japan, South Korea, and Australia. Project head Paul Lewis just gave a webinar about this, alongside Phil Plotch. Eno looks at high-level governance issues, trying to figure out if there’s some correlation with factors like federalism, the electoral system, and the legal system; there aren’t any. Instead of those, they try teasing out project delivery questions like the role of consultants, the contracting structure, and the concept of learning from other people.

This is an insightful report, especially on the matter of contract sizing, which they’ve learned from Chile. But it has a few other gems worth noting, regarding in-house planning capacity and, at meta level, learning from other people.

How Eno differs from us

The Transit Costs Project is a deep dive into five case studies: Boston, New York, Stockholm (and to a lesser extent other Nordic examples), Istanbul (and to a lesser extent other Turkish examples), and the cities of Italy. This does not mean we know everything there is to know about these cases; for example, I can’t speak to the issues of environmental review in the Nordic countries, since they never came up in interviews or in correspondence with people discussing the issue of the cost escalation of Nya Tunnelbanan. But it does mean knowing a lot about the particular history of particular projects.

Eno instead studies more cases in less detail. This leads to insights about places that we’ve overlooked – see below about Chile and South Korea. But it also leads to some misinterpretations of the data.

The most significant is the situation in Germany. Eno notes that Germany has very high subway construction costs but fairly low light rail costs. The explanation for the latter is that German light rail is at-grade trams, the easiest form of what counts as light rail in their database to build. American light rail construction costs are much higher partly because American costs are generally very high but also partly because US light rail tends to be more metro-like, for example the Green Line Extension in Boston.

However, in the video they were asked about why German subway costs were high and couldn’t answer. This is something that I can answer: it’s an artifact of which subway projects Germany builds. Germany tunnels so little, due to a combination of austerity (money here goes to gas subsidies, not metro investments) and urbanist preference for trams over metros, that the tunnels that are built are disproportionately the most difficult ones, where the capacity issues are the worst. The subways under discussion mostly include the U5 extension in Berlin, U4 in Hamburg, the Kombilösung in Karlsruhe, and the slow expansion of the tunneled part of the Cologne Stadtbahn. These are all city center subways, and even some of the outer extensions, like the ongoing extension of U3 in Nuremberg, are relatively close-in. The cost estimates for proposed outer extensions like U7 at both ends in Berlin or the perennially delayed U8 to Märkisches Viertel are lower, and not too different per kilometer from French levels.

This sounds like a criticism, because it mostly is. But as we’ll see below, even if they missed the ongoing changes in Nordic project delivery, what they’ve found from elsewhere points to the exact same conclusions regarding the problems of what our Sweden report calls the globalized system, and it’s interesting to see it from another perspective; it deepens our understanding of what good cost-effective practices for infrastructure are.

The issue of contract sizing in the Transit Costs Project

Part of what we call the globalized system is a preference for fewer, larger contracts over more, smaller ones. Trafikverket’s procurement strategy backs this as a way of attracting international bidders, and thus the Västlänken in Gothenburg, budgeted at 20,000 kronor in 2009 prices or around $2.8 billion in 2022 prices, comprises just six contracts. A planner in Manila, which extensively uses international contractors from all over Asia to build its metro system (which has reasonable elevated and extremely high underground costs), likewise told us that the preference for larger contracts is good, and suggested that Singapore may have high costs because it uses smaller contracts.

While our work on Sweden suggests that the globalized system is not good, the worst of it appeared to us to be about risk allocation. The aspects of the globalized system that center private-sector innovation and offload the risk to the contractor are where we see defensive design and high costs, while the state reacts by making up new regulations that raise costs and achieve little. But nothing that we saw suggested contract sizing was a problem.

And in comes Eno and brings up why smaller contracts are preferable. In Chile, where Eno appears to have done the most fieldwork, metro projects are chopped into many small contracts, and no contractor is allowed to get two adjacent segments. The economic logic for this is the opposite of Sweden’s: Santiago wishes to make its procurement open to smaller domestic firms, which are not capable of handling contracts as large as those of Västlänken.

And with this system, Santiago has lower costs than any Nordic capital. Project 63, building Metro Lines 3 and 6 at the same time, cost in 2022 PPP dollars $170 million/km; Nya Tunnelbanan is $230 million/km if costs don’t run over further, and the other Nordic subways are somewhat more expensive.

Other issues of state capacity

Eno doesn’t use the broader political term state capacity, but constantly alludes to it. The report stresses that project delivery must maintain large in-house planning capacity. Even if consultants are used, there must be in-house capacity to supervise them and make reasonable requests; clients that lack the ability to do anything themselves end up mismanaging consultants and making ridiculous demands, which point comes out repeatedly and spontaneously for our sources as well as those of Eno. While Trafikverket aims to privatize the state on the British model, it tries to retain some in-house capacity, for example picking some rail segments to maintain in-house to benchmark private contractors against; at least so far, construction costs in Stockholm are around two-fifths those of the Battersea extension in London, and one tenth those of Second Avenue Subway Phase 1.

With their broader outlook, Eno constantly stresses the need to devolve planning decisions to expert civil servants; Santiago Metro is run by a career engineer, in line with the norms in the Spanish- and Portuguese-language world that engineering is a difficult and prestigious career. American- and Canadian-style politicization of planning turns infrastructure into a black hole of money – once the purpose of a project is spending money, it’s easy to waste any budget.

Finally, Eno stresses the need to learn from others. The example it gives is from Korea, which learned the Japanese way of building subways, and has perfected it; this is something that I’ve noticed for years in my long-delayed series on how various countries build, but just at the level of a diachronic metro map it’s possible to see how Tokyo influenced Seoul. They don’t say so, but Ecuador, another low-cost Latin American country, used Madrid Metro as consultant for the Quito Metro.

The Nine-Euro Ticket

A three-month experiment has just ended: the 9€ monthly, valid on all local and regional public transport in Germany. The results are sufficiently inconclusive that nobody is certain whether they want it extended or not. September monthlies are reverting to normal fares, but some states (including Berlin and Brandenburg) are talking about restoring something like it starting October, and Finance and Transport Ministers Christian Lindner and Volker Wissing (both FDP) are discussing a higher-price version on the same principle of one monthly valid nationwide.

The intent of the nine-euro ticket

The 9€ ticket was a public subsidy designed to reduce the burden of high fuel prices – along with a large three-month cut in the fuel tax, which is replaced by a more permanent cut in the VAT on fuel from 19% to 7%. Germany has 2.9% unemployment as of July and 7.9% inflation as of August, with core inflation (excluding energy and food) at 3.4%, lower but still well above the long-term target. It does not need to stimulate demand.

Moreover, with Russia living off of energy exports, Germany does not need to be subsidizing energy consumption. It needs to suppress consumption, and a few places like Hanover are already restricting heating this winter to 19 degrees and no higher. The 9€ ticket has had multiple effects: higher use of rail, more domestic tourism, and mode shift – but because Germany does not need fiscal stimulus right now and does need to suppress fuel consumption, the policy needs to be evaluated purely on the basis of mode shift. Has it done so?

The impact of the nine-euro ticket on modal split

The excellent transport blog Zukunft Mobilität aggregated some studies in late July. Not all reported results of changes in behavior. One that did comes from Munich, where, during the June-early July period, car traffic fell 3%. This is not the effect of the 9€ ticket net of the reduction in fuel taxes – market prices for fuel rose through this period, so the reduction in fuel taxes was little felt by the consumer. This is just the effect of more-or-less free mass transit. Is it worth it?

Farebox recovery and some elasticities

In 2017 and 2018, public transport in Germany had a combined annual expenditure of about 14 billion €, of which a little more than half came from fare revenue (source, table 45 on p. 36). In the long run, maintaining the 9€ ticket would thus involve spending around 7 billion € in additional annual subsidy, rising over time as ridership grows due to induced demand and not just modal shift. The question is what the alternative is – that is, what else the federal government and the Länder can spent 7 billion € on when it comes to better public transport operations.

Well, one thing they can do is increase service. That requires us to figure out how much service growth can be had for a given increase in subsidy, and what it would do to the system. This in turn requires looking at service elasticity estimates. As a note of caution, the apparent increase in public transport ridership over the three months of more or less free service has been a lot less than what one would predict from past elasticity estimates, which suggests that at least fare elasticity is capped – demand is not actually infinite at zero fares. Service elasticities are uncertain for another reason: they mostly measure frequency, and frequency too has a capped impact – ridership is not infinite if service arrives every zero minutes. Best we can do is look at different elasticity estimates for different regimes of preexisting frequency; in the highest-frequency bucket (every 10 minutes or better), which category includes most urban rail in Germany, it is around 0.4 per the review of Totten-Levinson and their own work in Minneapolis. If it’s purely proportional, then doubling the subsidy means increasing service by 60% and ridership by 20%.

The situation is more complicated than a purely proportional story, though, and this can work in favor of expanding service. Just increasing service does not mean doubling Berlin U-Bahn frequency from every 5 to every 2.5 minutes; that would achieve very little. Instead, it would bump up midday service on the few German rail services with less midday than peak frequency, upgrade hourly regional lines to half-hourly (in which case the elasticity is not 0.4 but about 1), add minor capital work to improve speed and reliability, and add minor capital work to save long-term operating costs (for example, by replacing busy buses with streetcars and automating U-Bahns).

The other issue is that short- and long-term elasticities differ – and long-term elasticities are higher for both fares (more negative) and service (more positive). In general, ridership grows more from service increase than from fare cutting in the short and long run, but it grows more in the long run in both cases.

The issue of investment

The bigger reason to end the 9€ ticket experiment and instead improve service is the interaction with investment. Higher investment levels call for more service – there’s no point in building new S-Bahn tunnels if there’s no service through them. The same effect with fares is more muted. All urban public transport agencies project ridership growth, and population growth is largely urban and transit-oriented suburban.

An extra 7 billion € a year in investment would go a long way, even if divided out with direct operating costs for service increase. It’s around 250 km of tramway, or 50 km of U-Bahn – and at least the Berlin U-Bahn (I think also the others) operationally breaks even so once built it’s free money. In Berlin a pro-rated share – 300 million €/year – would be a noticeable addition to the city’s 2035 rail plan. Investment also has the habit to stick in the long term once built, which is especially good if the point is not to suppress short-term car traffic or to provide short-term fiscal stimulus to a 3% unemployment economy but to engage in long-term economic investment.

When Different Capital Investments Compete and When They Don’t

Advocates for mass transit often have to confront the issue of competing priorities for investment. These include some long-term tensions: maintenance versus expansion, bus versus rail, tram versus subway and commuter rail, high-speed rail versus upgraded legacy rail, electronics versus concrete. In some cases, they genuinely compete in the sense that building one side of the debate makes the other side weaker. But in others, they don’t, and instead they reinforce each other: once one investment is done, the one that is said to compete with it becomes stronger through network effects.

Urban rail capacity

Capacity is an example of when priorities genuinely compete. If your trains are at capacity, then different ways to relieve crowding are in competition: once the worst crowding is relieved, capacity is no longer a pressing concern.

This competition can include different relief lines. Big cities often have different lines that can be used to provide service to a particular area, and smaller ones that have to build a new line can have different plausible alignments for it. If one line is built or extended, the case for parallel ones weakens; only the strongest travel markets can justify multiple parallel lines.

But it can also include the conflict between building relief lines and providing extra capacity by other means, such as better signaling. The combination of conventional fixed block signaling and conventional operations is capable of moving maybe 24 trains per hour at the peak, and some systems struggle even with less – Berlin moves 18 trains per hour on the Stadtbahn, and has to turn additional peak trains at Ostbahnhof and make passengers going toward city center transfer. Even more modern signals struggle in combination with too complex branching, as in New York and some London lines, capping throughput at the same 24 trains per hour. In contrast, top-of-line driverless train signaling on captive metro lines can squeeze 42 trains per hour in Paris; with drivers, the highest I know of is 39 in Moscow, 38 on M13 in Paris, and 36 in London. Put another way, near-best-practice signaling and operations are equivalent in capacity gain to building half a line for every existing line.

Reach and convenience

In contrast with questions of capacity, questions of system convenience, accessibility, reliability, and reach show complementarity rather than competition. A rail network that is faster, more reliable, more comfortable to ride, and easier to access will attract more riders – and this generates demand for extensions, because potential passengers would be likelier to ride in such case.

In that sense, systematic improvements in signaling, network design, and accessibility do not compete with physical system expansion in the long run. A subway system with an elevator at every station, platform edge doors, and modern (ideally driverless) signaling enabling reliable operations and high average speeds is one that people want to ride. The biggest drawback of such a system is that it doesn’t go everywhere, and therefore, expansion is valuable. Expansion is even more valuable if it’s done in multiple directions – just as two parallel lines compete, lines that cross (such as a radial and a circumferential) reinforce each other through network effects.

This is equally true of buses. Interventions like bus shelter interact negatively with higher frequency (if there’s bus shelter, then the impact of wait times on ridership is reduced), but interact positively with everything else by encouraging more people to ride the bus.

The interaction between bus and rail investments is positive as well, not negative. Buses and trains don’t really compete anywhere with even quarter-decent urban rail. Instead, in such cities, buses feed trains. Bus shelter means passengers are likelier to want to ride the bus to connect the train, and this increases the effective radius of a train station, making the case for rail extensions stronger. The same is true of other operating treatments for buses, such as bus lanes and all-door boarding – bus lanes can’t make the bus fast enough to replace the subway, but do make it fast enough to extend the subway’s range.

Mainline rail investments

The biggest question in mainline rail is whether to build high-speed lines connecting the largest cities on the French or Japanese model, or to invest in more medium-speed lines to smaller cities on the German or especially Swiss model. German rail advocates assert the superiority of Germany to France as a reason why high-speed rail would detract from investments in everywhere-to-everywhere rail transport.

But in fact, those two kinds of investment complement each other. The TGV network connects most secondary cities to Paris, and this makes regional rail investments feeding those train stations stronger – passengers have more places to get to, through network effects. Conversely, if there is a regional rail network connecting smaller cities to bigger ones, then speeding up the core links gives people in those smaller cities more places to get to within two, three, four, five hours.

This is also seen when it comes to reliability. When trains of different speed classes can use different sets of track, it’s less likely that fast trains will get stuck behind slow ones, improving reliability; already Germany has to pad the intercity lines 20-25% (France: 10-14%; Switzerland: 7%). A system of passenger-dedicated lines connecting the largest cities is not in conflict with investments in systemwide reliability, but rather reinforces such reliability by removing some of the worst timetable conflicts on a typical intercity rail system in which single-speed class trains never run so often as to saturate a line.

Recommendation: invest against type

The implication of complementarity between some investment types is that a system that has prioritized one kind of investment should give complements a serious look.

For example, Berlin has barely expanded the U-Bahn in the last 30 years, but has built orbital tramways, optimized timed connections (for example, at Wittenbergplatz), and installed elevators at nearly all stations. All of these investments are good and also make the case for U-Bahn expansion stronger to places like Märkisches Viertel and Tegel.

In intercity rail, Germany has invested in medium-speed and regional rail everywhere but built little high-speed rail, while France has done the opposite. Those two countries should swap planners, figuratively and perhaps even literally. Germany should complete its network of 300 km/h lines to enable all-high-speed trips between the major cities, while France should set up frequent clockface timetables on regional trains anchored by timed connections to the TGV.

Deutsche Bahn’s Meltdown and High-Speed Rail

A seven-hour rail trip from Munich to Berlin – four and a half on the timetable plus two and a half of sitting at and just outside Nuremberg – has forced me to think a lot more about the ongoing collapse of the German intercity rail network. Ridership has fully recovered to pre-corona levels – in May it was 5% above 2019 levels, and that was just before the nine-euro monthly ticket was introduced, encouraging people to shift their trips to June, July, and August to take advantage of what is, among other things, free transit outside one’s city of residence. But at the same time, punctuality has steadily eroded this year:

It’s notable that the June introduction of the 9€ ticket is invisible in the graphic for intercity rail; it did coincide with deterioration in regional rail punctuality, but the worst problems are for the intercity trains. My own train was delayed by a mechanical failure, and then after an hour of failed attempts to restart it we were put on a replacement train, which spent around an hour sitting just outside Nuremberg, and even though it skipped Leipzig (saving 40 minutes in the process), it arrived at Berlin an hour and a half behind its schedule and two and a half behind ours.

Sometimes, those delays cascade. It’s not that high ridership by itself produces delays. The ICEs are fairly good at access and egress, and even a full train unloads quickly. Rather, it’s that if a train is canceled, then the passengers can’t get on the next one because it’s full beyond standing capacity; standing tickets are permitted in Germany, but there are sensors to ensure the train’s mass does not exceed a maximum level, which can be reached on unusually crowded trains, and so a train’s ability to absorb passengers on canceled trains as standees is limited.

But it’s not the short-term delays that I’m most worried about. One bad summer does not destroy a rail network; riders can understand a few bad months provided the problem is relieved. The problem is that there isn’t enough investment, and what investment there is is severely mistargeted.

Within German discourse, it’s common to assert superiority to France and Southern Europe in every possible way. France is currently undergoing an energy crisis, because the heat wave is such that river water cannot safely cool down its nuclear power plants; German politicians have oscillated between using this to argue that nuclear power is unreliable and the three remaining German plants should be shut down and using this to argue that Germany should keep its plants open as a gesture of magnanimity to bail out France.

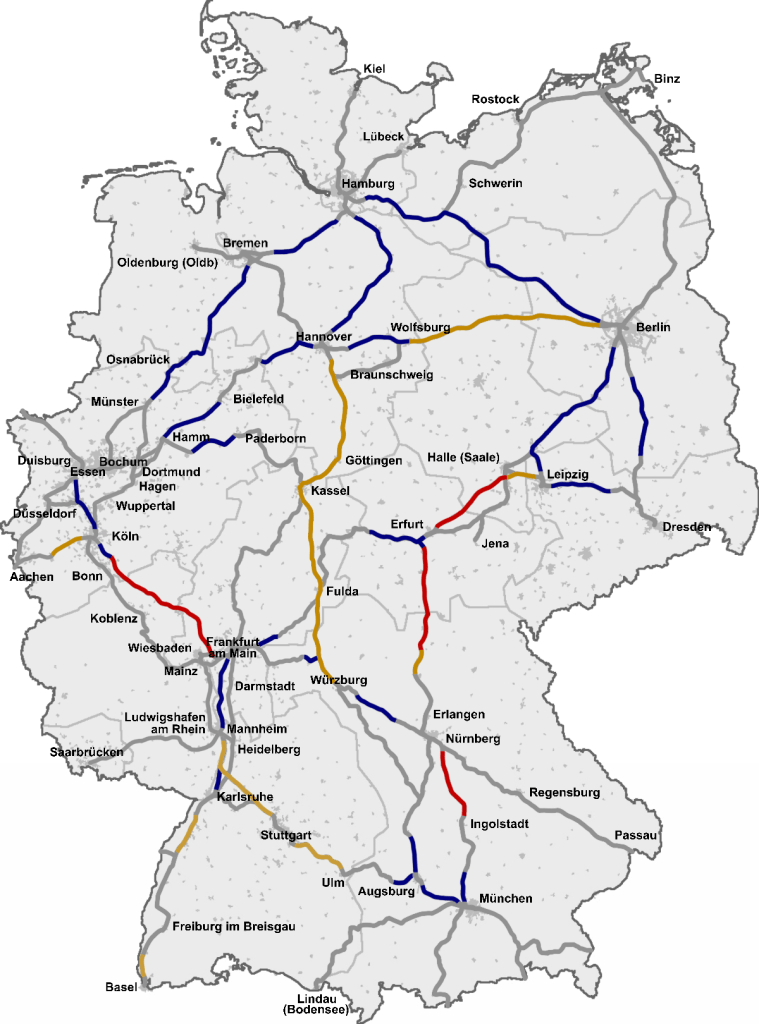

Rail transport features a similar set of problems. France has a connected network of high-speed lines, nearly all of which are used to get between Paris and secondary cities. Germany does not – it has high-speed lines but the longest connection between major cities allowing more than 200 km/h throughout is Cologne-Frankfurt, a distance of 180 km.

The natural response of most German rail advocates is to sneer at the idea of high-speed rail; France has genuine problems with punctuality, neglect of legacy rail lines, and poor interconnections between lines (it has nothing like the hourly or two-hour clockface timetables of German intercity rail), and those are all held as reasons why Germany has little to learn from France. Instead, those advocates argue, Germany should be investing in network-wide punctuality, because reliability matters more than speed.

The problem is that the sneering at France is completely unjustified. A French government investigation into punctuality in 2019-20 found that yes, French intercity trains suffered from extensive delays – but in 2019 intercity trains were on-time at the terminus 77.4% of the time, compared with 73.8% in Germany. Germany did better in 2020 when nobody was riding, but went back to 75% in 2021 as ridership began to recover. High-speed trains were the most punctual in Spain and the Netherlands, where they do not run on classical lines for significant stretches, unlike in France, Germany, or Italy.

Moreover, German trains are extremely padded. Der Spiegel has long been a critic of poor planning in German railways, and in 2019 it published a comparison of the TGV and ICE. The selected ICE connections were padded more than 20%; only Berlin-Munich was less, at 18%. The TGV comparisons were padded 11-14%; these are all lines running almost exclusively on LGVs, like Paris-Bordeaux, rather than the tardier lines running for significant distances on slow lines, like Paris-Nice. And even 11-14% is high; Swiss planning is 7% on congested urban approaches, with reliability as the center of the country’s design approach, while JR East suggested 4% for Shinkansen-style entirely dedicated track in its peer review of California High-Speed Rail.

Thus, completing a German high-speed rail network is not an opposed goal to reliability. Quite to the contrary, creating a separate network running only or almost only ICEs to connect Berlin, Hamburg, Hanover, Bremen, the main cities of the Rhine-Ruhr, Frankfurt, Munich, and Stuttgart means that there is less opportunity for delays to propagate. A delayed regional train would not slow down an intercity train, permitting not just running at high punctuality but also doing so while shrinking the pad from 25% to 7%, which offers free speed.

Cutting the pad to 7% interacts especially well with some of the individual lines Germany is planning. Hanover-Bielefeld, a distance of 100 km, can be so done in 27-28 minutes; this can be obtained from looking at the real performance specs of the Velaro Novo, but also from a Japanese sanity check, as the Nagoya-Kyoto distance is not much larger and taking the difference into account is easy. But the current plan is to do this in 31 minutes, just more than half an hour rather than just less, complicating the plan for regular timed connections on the half-hour.

German rail traffic is not collapsing – quite to the contrary. DB still expects to double intercity ridership by the mid-2030s. This requires investments in capacity, connectivity, speed, and reliability – and completing the high-speed network, far from prioritizing speed at the expense of the other needs, fulfills all needs at once. Half-hourly trains could ply every connection, averaging more than 200 km/h between major cities, and without cascading delays they would leave the ongoing summer of hell in the past. But this requires committing to building those lines rather than looking for excuses for why Germany should not have what France has.

German Rail Traffic Surges

DB announced today that it had 500,000 riders across the two days of last weekend. This is a record weekend traffic; May is so far 5% above 2019 levels, representing full recovery from corona. This is especially notable because of Germany’s upcoming 9-euro ticket: as a measure to curb high fuel price from the Russian war in Ukraine, during the months of June, July, and August, Germany is both slashing fuel taxes by 0.30€/liter and instituting a national 9€/month public transport ticket valid not just in one’s city of domicile but everywhere. In practice, rail riders respond by planning domestic rail trips for the upcoming three months; intercity trains are not covered by the 9€ monthly pass, but city transit in destination cities is, so Berliners I know are planning to travel to other parts of Germany during the window when local and regional transit is free, displacing trips that might be undertaken in May.

This is excellent news, with just one problem: Germany has not invested in its rail network enough to deal with the surge in traffic. Current traffic is already reaching projections made in the 2010s for 2030, when most of the Deutschlandtakt is supposed to go into effect, with higher speed and higher capacity than the network has today. Travel websites are already warning of capacity crunches in the upcoming three months of effectively free regional travel (chaining regional trains between cities is possible and those are covered by the 9€ monthly pass). Investment in capacity is urgent.

Sadly, such investment is still lagging. Germany’s intercity rail network rarely builds complete high-speed lines between major cities. The longest all-high-speed connection is between Cologne and Frankfurt, 180 km apart. Longer connections always have significant slow sections: Hamburg-Hanover remains slow due to local NIMBY opposition to a high-speed line, Munich’s lines to both Ingolstadt and Augsburg are slow, Berlin’s line toward Leipzig is upgraded to 200 km/h but not to full high-speed standards.

Moreover, plans to build high-speed rail in Germany remain compromised in two ways. First, they still avoid building completely high-speed lines between major cities. For example, the line from Hanover to the Rhine-Ruhr is slow, leading to plans for a high-speed line between Hanover and Bielefeld, and potentially also from Bielefeld to Hamm; but Hamm is a city of 180,000 people at the eastern margin of the Ruhr, 30 km from Dortmund and 60 from Essen. And second, the design standards are often too slow as well – Hanover-Bielefeld, a distance that the newest Velaro Novo trains could cover in about 28 minutes, is planned to be 31, compromising the half-hourly and hourly connections in the D-Takt. Both of these compromises create a network that 15 years from now is planned to have substantially lower average speeds than those achieved by France 20 years ago and by Spain 10 years ago.

But this isn’t just speed, but also capacity. An incomplete high-speed rail network overloads the remaining shared sections. A complete one removes fast trains from the legacy network except in legacy rail terminals where there are many tracks and average speeds are never high anyway; Berlin, for example, has four north-south tracks feeding Hauptbahnhof with just six trains per hour per direction. In China, very high throughput of both passenger rail (more p-km per route-km than anywhere in Europe) and freight rail (more ton-km per route-km than the United States) through the removal of intercity trains from the legacy network to the high-speed one, whose lines are called passenger-dedicated lines.

So to deal with the traffic surge, Germany needs to make sure it invests in intercity rail capacity immediately. This means all of the following items:

- Building all the currently discussed high-speed lines, like Frankfurt-Mannheim, Ulm-Augsburg (Stuttgart-Ulm is already under construction), and Hanover-Bielefeld.

- Completing the network by building high-speed lines even where average speeds today are respectable, like Berlin-Halle/Leipzig and Munich-Ingolstadt, and making sure they are built as close to city center as possible, that is to Dortmund and not just Hamm, to Frankfurt and not just Hanau, etc.

- Purchasing 300 km/h trains and not just 250 km/h ones; the trains cost more but the travel time reduction is noticeable and certain key connections work out for a higher-speed D-Takt only at 300, not 250.

- Designing high-speed lines for the exclusive use of passenger trains, rather than mixed lines with gentler freight-friendly grades and more tunnels. Germany has far more high-speed tunneling than France, not because its geography is more rugged, but because it builds mixed lines.

- Accelerating construction and reducing costs through removal of NIMBY veto points. Groups should have only two months to object, as in Spain; current practice is that groups have two months to say that they will object but do not need to say what the grounds for those objections are, and subsequently they have all the time they need to come up with excuses.

Free Public Transport: Why Now of All Times?

This is the second in a series of four posts about the poor state of political transit advocacy in the United States, following a post about the Green Line Extension in metro Boston, to be followed by the topics of operating aid and an Urban Institute report by Yonah Freemark.

There’s a push in various left-wing places to make public transportation free. It comes from various strands of governance, advocacy, and public transport, most of which are peripheral but all together add up to something. The US has been making some pushes recently: Boston made three buses fare-free as a pilot program, and California is proposing a three-month stimulus including free transit for that period and a subsidy for car owners. Germany is likewise subsidizing transport by both car and public transit. It’s economically the wrong choice for today’s economy of low unemployment, elevated inflation, and war, and it’s especially troubling when public transport advocates seize upon it as their main issue, in lieu of long-term investments into production of transit rather than its consumption.

Who’s for free public transit?

Historically, public transit was expected to be profitable, even when it was publicly-run. State-owned railroads predate the modern welfare state, and it was normal for them to not just break even but, in the case of Prussia, return profits to the state in preference to broad-based taxes. This changed as operating costs mounted in the middle of the 20th century and competition with cars reduced patronage. The pattern differs by country, and in some places (namely, rich Asia), urban rail remained breakeven or profitable, but stiff competition bit into ridership even in Japan. The norm in most of the West has been subsidies, usually at the local or regional level.

As subsidies were normalized, some proposed to go ahead and make public transport completely free. In the American civil rights movement, this included Ted Kheel, a backer of free public transit advocates like the activist Charles Komanoff and the academic Mark Delucchi. Reasons for free transit have included social equality (since it acts as a poll tax on commuters) and environmental benefits (since it competes with cars).

Anne Hidalgo has attempted and so far failed to find the money for free public transport in Paris, and other parts of Europe have settled for deep discounts in lieu of going fully fareless: Vienna charges 365€ for an annual pass (Berlin, which breaks even on the U-Bahn as far as I can tell, does so charging 86€/month).

In the United States, free transit has recently become a rallying cry for DSA, where it crowds out any discussion of improvement in the quality of service. Building new rail lines is the domain of wonks and neoliberals; socialists call for making things free, in analogy with their call for free universal health care. Boston has gotten in on the act, with conventional progressive (as opposed to DSA) mayor Michelle Wu campaigning on free buses within the municipality and getting the state-run MBTA to pilot free buses on three routes in low-income neighborhoods.

What’s wrong with free transit?

It costs money.

More precisely, it costs money that could be spent on other things. In Ile-de-France, as of 2018, fare revenues including employer benefits amounted to 4 billion euros, out of a total budget of 10.5 billion. The region can zero out this revenue, but on the same budget it can expand the Métro network by around 20-25 km a year – and the Métro is as far as I can tell profitable, subsidies going to suburban RER tails and buses. For that matter, the heavy subsidies to the suburbs, which pay the same cheap monthly rate as the city, could be replaced with investment in more and better lines.

The experiments with actually-free transit so far are in places with very weak revenues, like Estonia. Some American cities like it in context where public transport is only used by the desperate and no attempt is made at making service attractive to anyone else. Boston is unique in trying it in a context with higher fare revenue – but the buses are rail feeders, so the early pilot piggybacks on this and spends relatively little money in lost revenue, ignoring the long-term costs of breaking the (limited) fare integration between the buses and the subway.

What’s wrong with free transit now?

Free transit as deployed in the California proposal is in effect a stimulus project: the government gives people money in various ways. Germany is doing something similar, in a package including 9€ monthly tickets, a 0.30€ fuel tax cut, and a cut in energy taxes.

In Germany, unemployment right now is 2.9% and core inflation (without food and energy) is 3%. This is a country that spent a decade thinking going over 2% was immoral, and now the party that considers itself the most budget hawkish is cutting fuel taxes, in a time of conflict with an oil and gas exporter and a rise in military spending.

In the United States, unemployment is low as well, and inflation is high, 6.4%. This is not the time for stimulus or investments in consumption. It’s time for investments in production and suppression of consumption. So what gives?

Institutional Issues: Dealing with Technological and Social Change

I’ve covered issues of procurement, professional oversight, transparency, and proactive regulations so far. Today I’m going to cover a related institutional issue, regarding sensitivity to change. It’s imperative for the state to solve the problems of tomorrow using the tools that it expects to have, rather than wallowing in the world of yesterday. To do this, the civil service and the political system both have to be sensitive to ongoing social, economic, and technological changes and change their focus accordingly.

Most of this is not directly relevant to construction costs, except when changes favor or disfavor certain engineering methods. Rather, sensitivity to change is useful for making better projects, running public transit on the alignments where demand is or will soon be high using tools that make it work optimally for the travel of today and tomorrow. Sometimes, it’s the same as what would have worked for the world of the middle of the 20th century; other times, it’s not, and then it’s important not to get too attached to nostalgia.

Yesterday’s problems

Bad institutions often produce governments that, through slowness and stasis, focus on solving yesterday’s problems. Good institutions do the opposite. This problem is muted on issues that do not change much from decade to decade, like the political debate over overall government spending levels on socioeconomic programs. But wherever technology or some important social aspect changes quickly, this problem can grow to the point that outdated governance looks ridiculous.

Climate change is a good example, because the relative magnitudes of its various components have shifted in the last 20 years. Across the developed world, transportation emissions are rising while electricity generation emissions are falling. In electricity generation, the costs of renewable energy have cratered to the point of being competitive from scratch with just the operating costs of fossil and nuclear power. Within renewable energy, the revolution has been in wind (more onshore than offshore) and utility-scale solar, not the rooftop panels beloved by the greens of last generation; compare Northern Europe’s wind installation rates with what seemed obvious just 10 years ago.

I bring this up because in the United States today, the left’s greatest effort is spent on the Build Back Better Act, which they portray as making the difference between climate catastrophe and a green future, and which focuses on the largely solved problem of electricity. Transportation, which overtook electricity as the United States’ largest source of emissions in the late 2010s, is shrugged off in the BBB, because the political system of 2021 relitigates the battles of 2009.

This slowness cascades to smaller technical issues and to the civil service. A slow civil service may mandate equity analyses that assume that the needs of discriminated-against groups are geographic – more transit service to black or working-class neighborhoods – because they were generations ago. Today, the situation is different, and the needs are non-geographic, but not all civil service systems are good at recognizing this.

The issue of TOD

Even when the problem is static, for example how to improve public transit, the solutions may change based on social and technological changes.

The most important today is the need to integrate transportation planning with land use planning better. Historically, this wasn’t done much – Metro-land is an important counterexample, but in general, before mass motorization, developers built apartments wherever the trains went and there was no need for public supervision. The situation changed in the middle of the 20th century with mass competition with the automobile, and thence the biggest successes involved some kind of transit-oriented development (TOD), built by the state like the Swedish Million Program projects in Stockholm County or by private developer-railroads like those of Japan. Today, the default system is TOD built by private developers on land released for high-density redevelopment near publicly-built subways.

Some of the details of TOD are themselves subject to technological and social change:

- Deindustrialization means that city centers are nice, and waterfronts are desirable residential areas. There is little difference between working- and middle-class destinations, except that city center jobs are somewhat disproportionately middle-class.

- Secondary centers have slowly been erased; in New York, examples of declining job centers include Newark, Downtown Brooklyn, and Jamaica.

- Conversely, there is job spillover from city center to near-center areas, which means that it’s important to allow for commercialization of near-center residential neighborhoods; Europe does this better than the United States, which is why at scale larger than a few blocks, European cities are more centralized than American ones, despite the prominent lack of supertall office towers. Positive New York examples include Long Island City and the Jersey City waterfront, both among the most pro-development parts of the region.

- Residential TOD tends to be spiky: very tall buildings near subway stations, shorter ones farther away. Historic construction was more uniformly mid-rise. I encourage the reader to go on some Google Earth or Streetview tourism of a late-20th century city like Tokyo or Taipei and compare its central residential areas with those of an early-20th century one like Paris or Berlin.

The ideal civil service on this issue is an amalgamation of things seen in democratic East Asia, much of Western and Central Europe, and even Canada. Paris and Stockholm are both pretty good about integrating development with public transit, but only in the suburbs, where they build tens of thousands of housing units near subway stations. In their central areas, they are too nostalgic to redevelop buildings or build high-rises even on undeveloped land. Tokyo, Seoul, and Taipei are better and more forward-looking.

Public transit for the future

Besides the issue of TOD, there are details of how public transportation is built and operated that change with the times. The changes are necessarily subtle – this is mature technology, and VC-funded businesspeople who think they’re going to disrupt the industry invariably fail. This makes the technology ideal for treatment by a civil service that evolves toward the future – but it has to evolve. The following failures are regrettably common:

- Overfocus on lines that were promised long ago. Some of those lines remain useful today, and some are underrated (like Berlin’s U8 extension to Märkisches Viertel, constantly put behind higher cost-per-rider extensions in the city’s priorities). But some exist out of pure inertia, like Second Avenue Subway phases 3-4, which violates two principles of good network design.

- Proposals that are pure nostalgia, like Amtrak-style intercity trains running 1-3 times per day at average speeds that would shame most of Eastern Europe. Such proposals try to fit to the urban geography of the world of yesterday. In Germany, the coalition’s opposition to investment in high-speed rail misses how in the 21st century, German urban geography is majority-big city, where a high-speed rail network would go.

- Indifference to recent news relevant to the technology. Much of the BART to San Jose cost blowout can still be avoided if the agency throws away the large-diameter single-bore solution, proposed years ago by people who had heard of its implementation in Barcelona on L9 but perhaps not of L9’s cost overruns, making it by far Spain’s most expensive subway. In Germany, the design of intercity rail around the capabilities of the trains of 25 years ago falls in this category as well; technology moves on and the ongoing investments here work much better if new trains are acquired based on the technology of the 2020s.

- Delay in implementation of easy technological fixes that have been demonstrated elsewhere. In a world with automatic train-mounted gap fillers, there is no excuse anywhere for gaps between trains and platforms that do not permit a wheelchair user to board the train unaided.

- Slow reaction time to academic research on best practices, which can cover issues from timetabling to construction methods to pricing to bus shelter.

Probably the most fundamental issue of sensitivity to social change is that of bus versus rail modal choice. Buses are labor-intensive and therefore lose value as the economy grows; the high-frequency grid of 1960s Toronto could not work at modern wages, hence the need to shift public transit from bus to rail as soon as possible. This in turn intersects with TOD, because TOD for short-stop surface transit looks uniformly mid-rise rather than spiky. The state needs to recognize this and think about bus-to-rail modal shift as a long-term goal based on the wages of the 21st century.

The swift state

In my Niskanen piece from earlier this year, I used the expression building back, quickly, and made references to acting swiftly and the swift state. I brought up the issue of speeding up the planning lead time, such as the environmental reviews, as a necessary component for improving infrastructure. This is one component of the swift state, alongside others:

- Fast reaction to new trends, in technology, where people travel, etc. Even in deeply NIMBY areas like most of the United States, change in urban geography is rapid: job centers shift, new cities that are less NIMBY grow (Nashville’s growth rates should matter to high-speed rail planning), and connections change over time.

- Fast rulemaking to solve problems as they emerge. This means that there should be fewer layers of review; a civil servant should be empowered to make small decisions, and even the largest decisions should be delegated to a small expert team, intersecting with my previous posts about civil service empowerment.

- Fast response time to civil complaints. It’s fine to ignore a nag who thinks their property values deserve state protection, but if people complain about noise, delays, slow service, poor UI, crime, or sexism or racism, take them seriously. Look for solutions immediately instead of expecting them to engage in complex nonprofit proof-of-work schemes to show that they are serious. The state works for the people, and not the other way around.

- Constant amendment of priorities based on changes in the rest of society. A state that wishes to fight climate change must be sensitive to what the most pressing sources of emissions are and deal with them. If you’re in a mature urban or national economy, and you’re not frustrating nostalgics who show you plans from the 1950s, you’re probably doing something wrong.

In all cases, it is critical to build using the methods of the world of today, aiming to serve the needs of the world of tomorrow. Those needs are fairly predictable, because public transit is not biotech and changes therein are nowhere near as revolutionary as mRNA and viral vector vaccines. But they are not the same as the needs of 60 years ago, and good institutions recognize this and base their budgetary and regulatory focus on what is relevant now and not what was relevant when color TVs were new.