Category: New York

How Tunneling in New York is Easier Than Elsewhere

I hate the term “apples-to-apples.” I’ve heard those exact three words from so many senior people at or near New York subway construction in response to any cost comparison. Per those people, it’s inconceivable that if New York builds subways for $2 billion/km, other cities could do it for $200 million/km. Or, once they’ve been convinced that those are the right costs, there must be some justifiable reason – New York must be a uniquely difficult tunneling environment, or its size must mean it needs to build bigger stations and tunnels, or it must have more complex utilities than other cities, or it must be harder to tunnel in an old, dense industrial metropolis. Sometimes the excuses are more institutional but always drawn to exculpate the political appointees and senior management – health benefits are a popular excuse and so is a line like “we care about worker rights/disability rights in America.” The excuses vary but there’s always something. All of these excuses can be individually disposed of fairly easily – for example, the line about worker and disability rights is painful when one looks at the construction costs in the Nordic countries. But instead of rehashing this, it’s valuable to look at some ways in which New York is an easier tunneling environment than many comparison cases.

Geology

New York does not have active seismology. The earthquake-proofing required in such cities as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Tokyo, Istanbul, and Naples can be skipped; this means that simpler construction techniques are viable.

Nor is New York in an alluvial floodplain. The hard schist of Manhattan is not the best rock to tunnel in (not because it’s hard – gneiss is hard and great to tunnel in – but because it’s brittle), but cut-and-cover is viable. The ground is not going to sink 30 cm from subway construction as it did in Amsterdam – the hard rock can hold with limited building subsidence.

The underwater crossings are unusually long, but they are not unusually deep. Marmaray and the Transbay Tube both had to go under deep channels; no proposed East River or Hudson crossing has to be nearly so deep, and conventional tunnel boring is unproblematic.

History and archeology

In the United Kingdom, 200 miles is a long way. In the United States, 200 years is a long time. New York is an old historic city by American standards and by industrial standards, but it is not an old historic city by any European or Asian standard, unless the standard in question is that of Dubai. There are no priceless monuments in its underground, unlike those uncovered during tunneling in Mexico City, Istanbul, Rome, or Athens; the last three have tunneled through areas with urban history going back to Classical Antiquity.

In addition to past archeological artifacts, very old cities also run into the issue of priceless ruins. Rome Metro Line C’s ongoing expansion is unusually expensive for Italy – segment T3 is $490 million per km in PPP 2022 dollars – because it passes by the Imperial Forum and the Colosseum, where no expense can be spared in protecting monuments from destruction by building subsidence, limited by law to 3 mm; the stations are deep-mined because cut-and-cover is too destructive and so is the Barcelona method of large-diameter bores. More typical recent tunnels in Rome and Milan, even with the extra costs of archeology and earthquake-proofing, are $150-300 million/km (Rome costing more than Milan).

In New York, in contrast, buildings are valued for commercial purposes, not historic purposes. Moreover, in the neighborhoods where subways are built or should be, there is extensive transit-oriented development opportunity near the stations, where the subsidence risk is the greatest. It’s possible to be more tolerant of risk to buildings in such an environment; in contrast, New York spent effort shoring up a building on Second Avenue that is now being replaced with a bigger building for TOD anyway.

Street network

New York is a city of straight, wide streets. A 25-meter avenue is considered narrow; 30 is more typical. This is sufficient for cut-and-cover without complications – indeed, it was sufficient for four-track cut-and-cover in the 1900s. Bored tunnels can go underneath those same streets without running into building foundations and therefore do not need to be very deep unless they undercross older subway lines.

Moreover, the city’s grid makes it easier to shut down traffic on a street during construction. If Second Avenue is not viable as a through-route during construction, the city can make First Avenue two-way for the duration. Few streets are truly irreplaceable, even outside Manhattan, where the grid has more interruptions. For example, if an eastward extension of the F train under Hillside is desired, Jamaica can substitute for Hillside during construction and this makes the cut-and-cover pain (even if just at stations) more manageable.

The straightforward grid also makes station construction easier. There is no need to find staging grounds for stations such as public parks when there’s a wide street that can be shut down for construction. It’s also simple to build exits onto sidewalks or street medians to provide rapid egress in all directions from the platform.

Older infrastructure

Older infrastructure, in isolation, makes it difficult to build new tunnels, and New York has it in droves. But things are rarely isolated. It matters what older infrastructure is available, and sometimes it’s a boon more than a bane.

One way it can be a boon is if older construction made provisions for future expansion. This is the most common in cities with long histories of unrealized plans, or else the future expansion would have been done already; worldwide, the top two cities in such are New York and Berlin. The track map of the subway is full of little bellmouths and provisions for crossing stations, many at locations that are not at all useful today but many others at locations that are. Want to extend the subway to Kings Plaza under Utica? You’re in luck, there’s already a bellmouth leading from the station on the 3/4 trains. How about going to Sheepshead Bay on Nostrand? You’re in luck again, trackways leading past the current 2/5 terminus at Flatbush Avenue exist as the station was intended to be only a temporary terminal.

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 also benefits from such older infrastructure – cut-and-cover tunnels between the stations preexist and will be reused, so only the stations need to be built and the harder segment curving under 125th Street crossing under the 4/5/6.

Penn Station Expansion is Based on Fraud

New York is asking for $20 billion for reconstruction ($7 billion) and physical expansion ($13 billion) of Penn Station. The state is treating it as a foregone conclusion that it will happen and it will get other people’s money for it; the state oversight board just voted for it despite the uncertain funding. Facing criticism from technical advocates who have proposed alternatives that can use Penn Station’s existing infrastructure, lead agency Empire State Development (ESD) has pushed back. The document I’ve been looking at lately is not new – it’s a presentation from May 2021 – but the discussion I’ve seen of it is. The bad news is that the presentation makes fraudulent claims about the capabilities of railroads in defense of its intention to waste $20 billion, to the point that people should lose their jobs and until they do federal funding for New York projects should be stingier. The good news is that this means that there are no significant technical barriers to commuter rail modernization in New York – the obstacles cited in the presentation are completely trivial, and thus, if billions of dollars are available for rail capital expansion in New York, they can go to more useful priorities like IBX.

What’s the issue with Penn Station expansion?

Penn Station is a mess at both the concourse and track levels. The worst capacity bottleneck is the western approach across the river, the two-track North River Tunnels, which on the eve of corona ran about 20 overfull commuter trains and four intercity trains into New York at the peak hour; the canceled ARC project and the ongoing Gateway project both intend to address this by adding two more tracks to Penn Station.

Unfortunately, there is a widespread belief that Penn Station’s 21 existing tracks cannot accommodate all traffic from both east (with four existing East River Tunnel tracks) and west if new Hudson tunnels are built. This belief goes back at least to the original ARC plans from 20 years ago: all plans involved some further expansion, including Alt G (onward connection to Grand Central), Alt S (onward connection to Sunnyside via two new East River tunnel tracks), and Alt P (deep cavern under Penn Station with more tracks). Gateway has always assumed the same, calling for a near-surface variation of Alt P: instead of a deep cavern, the block south of Penn Station, so-called Block 780, is to be demolished and dug up for additional tracks.

The impetus for rebuilding Penn Station is a combination of a false belief that it is a capacity bottleneck (it isn’t, only the Hudson tunnels are) and a historical grudge over the demolition of the old Beaux-Arts station with a labyrinthine, low-ceiling structure that nobody likes. The result is that much of the discourse about the need to rebuild the station is looking for technical justification for an aesthetic decision; unfortunately, nobody I have talked to or read in New York seems especially interested in the wayfinding aspects of the poor design of the existing station, which are real and do act as a drag on casual travel.

I highlight the history of Penn Station and the lead agency – ESD rather than the MTA, Port Authority, or Amtrak – because it showcases how this is not really a transit project. It’s not even a bad transit project the way ARC Alt P was or the way Gateway with Block 780 demolition is. It’s an urban renewal project, run by people who judge train stations by which starchitect built them and how they look in renderings rather than by how useful they are for passengers. Expansion in this context is about creating the maximum footprint for renderings, and not about solving a transportation problem.

Why is it believed that Penn Station needs more tracks?

Penn Station tracks are used inefficiently. The ESD pushback even hints at why, it just treats bad practices as immutable. Trains have very long dwell times: per p. 22 of the presentation, the LIRR can get in and out in a quick 6 minutes, but New Jersey Transit averages 12 and Amtrak averages 22. The reasons given for Amtrak’s long dwell are “baggage” (there is no checked baggage on most trains), “commissary” (the cafe car is restocked there, hardly the best use of space), and “boarding from one escalator” (this is unnecessary and in fact seasoned travelers know to go to a different concourse and board there). A more reasonable dwell time at a station as busy as Penn Station on trains designed for fast access and egress is 1-2 minutes, which happens hundreds of times a day at Shin-Osaka; on the worse-designed Amtrak rolling stock, with its narrower doors, 5 minutes should suffice.

New Jersey Transit can likewise deboard fast, although it might need to throw away the bilevels and replace them with longer single-deck trains. This reduces on-board capacity somewhat, but this entire discussion assumes the Gateway tunnel has been built, otherwise even present operations do not exhaust the station’s capacity. Moreover, trains can be procured for comfortable standing; subway riders sometimes have to stand for 20-30 minutes and commuter rail riders should have similar levels of comfort – the problem today is standees on New Jersey Transit trains designed without any comfortable standing space.

But by far the biggest single efficiency improvement that can be done at Penn Station is through-running. If trains don’t have to turn back or even continue to a yard out of service, but instead run onward to suburbs on the other side of Manhattan, then the dwell time can be far less than 6 minutes and then there is much more space at the station than it would ever need. The station’s 21 tracks would be a large surplus; some could be removed to widen the platform, and the ESD presentation does look at one way to do this, which isn’t necessarily the optimal way (it considers paving over every other track to widen the platforms and permit trains to open doors on both sides rather than paving over every other track pair to widen the platforms much more but without the both-side doors). But then the presentation defrauds the public on the opportunity to do so.

Fraudulent claim #1: 8 minute dwells

On p. 44, the presentation compares the capacity with and without through-running, assuming half the tracks are paved over to widen the platforms. The explicit assumption is that through-running commuter rail requires trains to dwell 8 minutes at Penn Station to fully unload and load passengers. There are three options: the people who wrote this may have lied, or they may be incompetent, or they be both liars and incompetent.

In reality, even very busy stations unload and load passengers in 30-60 seconds at rush hour. Limiting cases reaching up to 90-120 seconds exist but are rare; the RER A, which runs bilevels, is the only one I know of at 105.

On pp. 52-53, the presentation even shows a map of the central sections of the RER, with the central stations (Gare du Nord, Les Halles, and Auber/Saint-Lazare) circled. There is no text, but I presume that this is intended to mean that there are two CBD stations on each line rather than just one, which helps distribute the passenger load better; in contrast, New York would only have one Manhattan station on through-trains on the Northeast Corridor, which requires a longer dwell time. I’ve heard this criticism over the years from official and advocate sources, and I’m sympathetic.

What I’m not sympathetic to is the claim that the dwell time required at Penn Station is more than the dwell time required at multiple city center stations, all combined. On the single-deck RER B, the combined rush hour dwell time at Gare du Nord and Les Halles is around 2 minutes normally (and the next station over, Saint-Michel, has 40-60 second rush hour dwells and is not in the CBD unless you’re an academic or a tourist); in unusual circumstances it might go as high as 4 minutes. The RER A’s combined dwell is within the same range. In Munich, there are six stations on the S-Bahn trunk between Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof – but at the intermediate stations (with both-sides door opening) the dwell times are 30 seconds each and sometimes the doors only stay open 20 seconds; Hauptbahnhof and Ostbahnhof have longer dwell times but are not busier, they just are used as control points for scheduling.

The RER A’s ridership in 2011 was 1.14 million trips per weekday (source, p. 22) and traffic was 30 peak trains per hour and 24 reverse-peak trains; at the time, dwell times at Les Halles and Auber were lower than today, and it took several more years of ridership growth for dwell times to rise to 105 seconds, reducing peak traffic to 27 and then 24 tph. The RER B’s ridership was 983,000 per workday in 2019, with 20 tph per direction. Munich is a smaller city, small enough New Yorkers may look down on it, but its single-line S-Bahn had 950,000 trips per workday in 2019, on 30 peak tph in each direction. In contrast, pre-corona weekday ridership was 290,000 on the LIRR, 260,000 on Metro-North, and around 270,000 on New Jersey Transit – and the LIRR has a four-track tunnel into Manhattan, driving up traffic to 37 tph in addition to New Jersey’s 21. It’s absurd that the assumption on dwell time at one station is that it must be twice the combined dwell times at all city center stations on commuter lines that are more than twice as busy per train as the two commuter railroads serving Penn Station.

Using a more reasonable figure of 2 minutes in dwell time per train, the capacity of through-running rises to a multiple of what ESD claims, and through-running is a strong alternative to current plans.

Fraudulent claim #2: no 2.5% grades allowed

On pp. 38-39, the presentation claims that tracks 1-4 of Penn Station, which are currently stub-end tracks, cannot support through-running. In describing present-day operations, it’s correct that through-running must use the tracks 5-16, with access to the southern East River Tunnel pair. But it’s a dangerously false assumption for future infrastructure construction, with implications for the future of Gateway.

The rub is that the ARC alternatives that would have continued past Penn Station – Alts P and G – both were to extend the tunnel east from tracks 1-4, beneath 31st Street (the existing East River Tunnels feed 32nd and 33rd). Early Gateway plans by Amtrak called for an Alt G-style extension to Grand Central, with intercity trains calling at both stations. There was always a question about how such a tunnel would weave between subway tunnels, and those were informally said to doom Alt G. The presentation unambiguously answers this question – but the answer it gives is the exact opposite of what its supporting material says.

The graphic on p. 39 shows that to clear the subway’s Sixth Avenue Line, the trains must descend a 2.45% grade. This accords with what I was told by Foster Nichols, currently a senior WSP consultant but previously the planner who expanded Penn Station’s lower concourse in the 1990s to add platform access points and improve LIRR circulation, thereby shortening LIRR dwell times. Nichols did not give the precise figure of 2.45%, but did say that in the 1900s the station had been built with a proviso for tracks under 31st, but then the subway under Sixth Avenue partly obstructed them, and extension would require using a grade greater than 2%.

The rub is that modern urban and suburban trains climb 4% grades with no difficulty. The subway’s steepest grade, climbing out of the Steinway Tunnel, is 4.5%, and 3-3.5% grades are routine. The tractive effort required can be translated to units of acceleration: up a 4% grade, fighting gravity corresponds to 0.4 m/s^2 acceleration, whereas modern trains do 1-1.3 m/s^2. But it’s actually easier than this – the gradient slopes down when heading out of the station, and this makes the grade desirable: in fact, the subway was built with stations at the top of 2.5-3% grades (for example, see figure 7 here) so that gravity would assist acceleration and deceleration.

The reason the railroaders don’t like grades steeper than 2% is that they like the possibility of using obsolete trains, pulled by electric locomotives with only enough tractive effort to accelerate at about 0.4 m/s^2. With such anemic power, steeper grades may cause the train to stall in the tunnel. The solution is to cease using such outdated technology. Instead, all trains should be self-propelled electric multiple units (EMUs), like the vast majority of LIRR and Metro-North rolling stock and every subway train in the world. Japan no longer uses electric locomotives at all on its day trains, and among the workhorse European S-Bahn systems, all use EMUs exclusively, with the exception of Zurich, which still has some locomotive-pulled trains but is transitioning to EMUs.

It costs money to replace locomotive-hauled trains with EMUs. But it doesn’t cost a lot of money. Gateway won’t be completed tomorrow; any replacement of locomotives with EMUs on the normal replacement cycle saves capital costs rather than increasing them, and the same is true of changing future orders to accommodate peak service expansion for Gateway. Prematurely retiring locomotives does cost money, but New Jersey Transit only has 100 electric locomotives and 29 of them are 20 years old at this point; the total cost of such an early retirement program would be, to first order, about $1 billion. $1 billion is money, but it has independent transportation benefits including faster acceleration and higher reliability, whereas the $13 billion for Penn Station expansion have no transportation benefits whatsoever. Switzerland may be a laggard in replacing the S-Bahn’s locomotives with EMUs, but it’s a leader in the planning maxim electronics before concrete, and when the choice is between building a through-running tunnel for EMUs and building a massive underground station to store electric locomotives, the correct choice is to go with the EMUs.

How do they get away with this?

ESD is defrauding the public. The people who signed their names to the presentation should most likely not work for the state or any of its contractors; the state needs honest, competent people with experience building effective mass transit projects.

Those people walk around with their senior manager titles and decades of experience building infrastructure at outrageous cost and think they are experts. And why wouldn’t they? They do not respect any knowledge generated outside the New York (occasionally rest-of-US) bubble. They think of Spain as a place to vacation, not as a place that built 150 kilometers of subway 20 years ago for the same approximate cost as Second Avenue Subway phases 1 and 2. They think of smaller cities like Milan as beneath their dignity to learn about.

And what’s more, they’ve internalized a culture of revealing as little as possible. That closed attitude has always been there; it’s by accident that they committed two glaring acts of fraud to paper with this presentation. Usually they speak in generalities: the number of people who use the expression “apples-to-apples” and provide no further detail is staggering. They’ve learned to be opaque – to say little and do little. Most likely, they’re under political pressure to make the Penn Station reconstruction and expansion look good in order to generate what the governor thinks are good headlines, and they’ve internalized the idea that they should make up numbers to justify a political project (and in both the Transit Costs Project and previous reporting I’d talked to people in consulting who said they were under such formal or informal pressure for other US projects).

The way forward

With too much political support for wasting $20 billion at the state level, the federal government should step in and put an end to this. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) has $66 billion for mainline rail; none of this money should go to Penn Station expansion, and the only way any money should go to renovation is if it’s part of a program for concrete improvement in passenger rail function. If New York wishes to completely remodel the platform level, and not just pave over every other track or every other track pair, then federal support should be forthcoming, albeit not for $7 billion or even half that. But it’s not a federal infrastructure priority to restore some kind of social memory of the old Penn Station. Form follows function; beautiful, airy train stations that people like to travel through have been built under this maxim, for example Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

To support good rail construction, it’s obligatory that experts be put in charge – and there aren’t any among the usual suspects in New York (or elsewhere in the US). Americans respect Germany more than they do Spain but still less than they should either; unless they have worked in Europe for years, their experience at Berlin Hbf and other modern stations is purely as tourists. The most celebrated New York public transportation appointment in recent memory, Andy Byford, is an expert (on operations) hired from abroad; as I implored the state last year, it should hire people like him to head major efforts like this and back them up when they suggest counterintuitive things.

Mainline rail is especially backward in New York – in contrast, the subway planners that I’ve had the fortune to interact with over the years are insightful and aware of good practices. Managers don’t need much political pressure to say absurd things about gradients and dwell times, in effect saying things are impossible that happen thousands of times a day on this side of the Pond. The political pressure turns people who like pure status quo into people who like pure status quo but with $20 billion in extra funding for a shinier train hall. But both the political appointees and the obstructive senior managers need to go, and managers below them need to understand that do-nothing behavior doesn’t get them rewarded and (as they accumulate seniority) promoted but replaced. And this needs to start with a federal line in the sand: BIL money goes to useful improvements to speed, reliability, capacity, convenience, and clarity – but not to a $20 billion Penn Station reconstruction and expansion that do nothing to address any of these concerns.

New York Commuter Rail Rolling Stock Needs

Last night I was asked on Twitter about the equipment needs for an integrated commuter rail system in New York, with through-running from the New Jersey side to the Long Island and Connecticut side. So without further ado, let’s work this out, based on different scenarios for how much infrastructure is built and how much capacity there is.

Assumptions on speed

The baseline assumptions in all scenarios should be,

- The rolling stock is new – this is about a combined purchase of trains, so the trains should be late-model international EMUs with the appropriate performance specs.

- Trains are single-deck, to speed up boarding and alighting in Manhattan.

- The entire system is electrified and equipped with high platforms, to enable rapid acceleration and limit dwell times to 30 seconds, except at Grand Central and Penn Station, where they are 2 minutes each.

- Non-geometric speed limits (such as difficult turnouts) are lifted through better track maintenance standards and the use of track renewal machines, and geometric speed limits are based on 300 mm of total equivalent cant, or a lateral acceleration of 2 m/s^2 in the horizontal plane.

- However, speed limits through new urban tunnels, except those used by intercity trains, are at most 130 km/h even when interstations are long.

- Every junction that needs to be grade-separated for reliability is.

- Peak and reverse-peak service are symmetric (asymmetric service may not even save rolling stock if the peak is long enough).

- Urban areas have infill stations as needed to provide coverage, except where lines are parallel to the subway, such as the LIRR Main Line west of Jamaica.

- Timetables are padded 7% over the technical travel time, and the turnaround time is set at 10 minutes per terminal.

Line trip times

With the above assumptions in mind, let’s compute end-to-end trip times by line. Note that we do not care which lines match up with which lines east and west of Penn Station – the point is not to write complete timetables, but to estimate rolling stock needs. The shortcut we can take is that trains are sufficiently frequent at the peak that artifacts coming from the question of which lines match with which likes are not going to matter. Trip times without links are directly computed for the purposes of this post, and should be viewed as somewhat less certain, within a few percent in each direction.

| Terminus | Service pattern | Trip time |

| Great Neck | Local | 0:32 |

| Port Washington | Local | 0:39 |

| Hempstead | Local | 0:37 |

| East Garden City | Local | 0:37 |

| Far Rockaway | Local | 0:39 |

| Long Beach | Local | 0:40 |

| West Hempstead | Local | 0:36 |

| West Hempstead Dinky | Local | 0:10 |

| Babylon | Local | 0:58 |

| Montauk | Local | 2:20 |

| Huntington | Express west of Floral Park | 0:43 |

| Port Jefferson | Express west of Floral Park | 1:10 |

| Ronkonkoma | Express west of Floral Park | 0:57 |

| Greenport | Express west of Floral Park | 1:42 |

| Oyster Bay Dinky | Local | 0:25 |

| New Rochelle (via NEC) | Local | 0:26 |

| New Rochelle (to GCT) | Local | 0:21 |

| Stamford (via NEC) | Local | 0:50 |

| Stamford (to GCT) | Local | 0:45 |

| New Haven (to GCT) | Express south of Stamford | 1:18 |

| New Canaan (to GCT) | Express south of Stamford | 0:43 |

| Danbury (to GCT) | Express south of Stamford | 1:15 |

| Waterbury (to GCT) | Express south of Stamford | 1:40 |

| North White Plains | Local | 0:40 |

| Southeast | Local | 1:16 |

| Wassaic | Local | 1:48 |

| Yonkers (to GCT) | Local | 0:25 |

| Yonkers (via West Side) | Local | 0:23 |

| Croton-Harmon (to GCT) | Local | 0:52 |

| Croton-Harrmon (via West Side) | Local | 0:50 |

| Poughkeepsie (to GCT) | Express south of Croton | 1:12 |

| Poughkeepsie (via West Side) | Express south of Croton | 1:10 |

| Jersey Avenue | Local | 0:41 |

| Trenton | Local | 1:01 |

| Trenton | Express north of New Brunswick | 0:52 |

| Princeton Dinky | Local | 0:03 |

| Long Branch | Local | 1:01 |

| Bay Head | Local | 1:23 |

| Raritan | Local | 0:47 |

| High Bridge | Local | 1:04 |

| Dover (via Summit) | Local | 1:00 |

| Dover (via Montclair) | Local | 1:04 |

| Hackettstown (via Summit) | Local | 1:22 |

| Montclair State University | Local | 0:33 |

| Gladstone | Local | 1:08 |

| Summit | Local | 0:34 |

| Suffern (via Paterson) | Local | 0:50 |

| Suffern (via Radburn) | Local | 0:47 |

| Port Jervis (via Radburn) | Local | 1:50 |

| Spring Valley | Local | 0:50 |

| Nyack | Local | 0:51 |

| Tottenville (to GCT) | Local | 0:47 |

| Port Ivory (to GCT) | Local | 0:28 |

| GCT-Penn (with dwells) | Local | 0:04 |

| Jamaica-FiDi adjustment | Local | 0:02 |

The last two adjustment numbers are designed to be added to other lines: Grand Central-Penn Station with 2 minute dwell times at each stop adds 4 minutes to the total trip time, net of savings from no longer having bumper tracks at Grand Central. The Staten Island numbers are also net of such savings. The Jamaica-Lower Manhattan adjustment reflects the fact that, I believe, Jamaica-Lower Manhattan commuter trains with several infill stops would take 0:19, compared with 0:17 on local trains to Penn Station (also with infill).

The 3-line system

The 3-line system is a bare Gateway tunnel with a continuing tunnel to Grand Central (Line 2) and a realignment of the Empire Connection to permit through-service to the northern tunnel pair under the East River (Line 3); Line 1 is, throughout this post, the present-day Hudson tunnel paired with the southern tunnel pair under the East River.

With no Lower Manhattan service, the Erie lines and the Staten Island lines would not be part of this system. Long Island would need to economize by cutting the West Hempstead Branch to a shuttle train connecting to frequent Atlantic Branch and Babylon Branch trains at Valley Stream. The Harlem Line would terminate at Grand Central. Moreover, the weakest tails of the lines today, that is to say Wassaic, Waterbury, Greenport, and Montauk, would not be part of this system – they should be permanently turned into short dinkies.

The table below makes some implicit assumptions about which lines run through and which do not; those that do only require one turnaround as they are paired at the Manhattan end. Overall this does not impact the regionwide fleet requirement.

Total peak service under this is likely to be,

| Terminus | Trip time | Tph | Fleet size |

| Great Neck | 0:32 | 6 | 8 |

| Port Washington | 0:39 | 6 | 9 |

| Hempstead | 0:37 | 12 | 17 |

| Far Rockaway | 0:39 | 6 | 10 |

| Long Beach | 0:40 | 6 | 10 |

| West Hempstead Dinky | 0:10 | 6 | 4 |

| Babylon | 0:58 | 12 | 28 |

| Huntington | 0:43 | 6 | 11 |

| Port Jefferson | 1:10 | 6 | 16 |

| Ronkonkoma | 0:57 | 12 | 27 |

| Oyster Bay Dinky | 0:25 | 3 | 4 |

| Stamford (via NEC) | 0:50 | 6 | 11 |

| Stamford (to GCT, via Alt G) | 0:49 | 6 | 11 |

| New Haven (via Alt G) | 1:22 | 6 | 18 |

| New Canaan (via Alt G) | 0:47 | 3 | 6 |

| Danbury (via Alt G) | 1:19 | 3 | 9 |

| North White Plains | 0:40 | 12 | 20 |

| Southeast | 1:16 | 12 | 35 |

| Yonkers (to GCT, via Alt G) | 0:29 | 6 | 7 |

| Croton-Harmon (via West Side) | 0:50 | 6 | 11 |

| Poughkeepsie (via West Side) | 1:10 | 6 | 15 |

| Jersey Avenue | 0:41 | 6 | 10 |

| Trenton | 1:01 | 6 | 14 |

| Long Branch | 1:01 | 3 | 7 |

| Bay Head | 1:23 | 3 | 9 |

| Raritan | 0:47 | 3 | 6 |

| High Bridge | 1:04 | 3 | 7 |

| Dover (via Summit) | 1:00 | 3 | 7 |

| Dover (via Montclair) | 1:04 | 3 | 7 |

| Hackettstown | 1:22 | 3 | 9 |

| Montclair State U | 0:33 | 3 | 4 |

| Gladstone | 1:08 | 3 | 8 |

| Summit | 0:34 | 3 | 4 |

This totals 379 trainsets; most should be 12 cars long, and only a minority should be as short as 8 cars; only the dinkies should be shorter than that. Off-peak, service is likely to be much less frequent – perhaps half as frequent on most lines, with some less frequent lines reduced to dinkies with timed connections to maintain base 20-minute frequencies – but the peak determines the capital needs, not the off-peak.

The 5-line system

The Lower Manhattan tunnels connecting Jersey City (or Hoboken) with Downtown Brooklyn and Grand Central with Staten Island make for a Line 4 (Harlem-Grand Central-Staten Island) and a Line 5 (Erie-Atlantic Branch). With such a system in place, more service can be run. The Babylon Branch no longer needs to use the Main Line west of Jamaica, making room for very frequent service on the Hempstead Line, with very high frequency to East Garden City.

In addition to the 379 trainsets for the 3-line system, rolling stock needs to be procured for Staten Island, the Erie lines, and incremental service for extra LIRR trains. In the table below, trip times for the Erie lines absorb the 2-minute adjustment for the LIRR trains they connect to; Staten Island lines are already reckoned from Grand Central. Dwell times for such lines are not included at all, as they are already included in the 3-line table.

The table also omits Port Jervis, as a tail of the Erie Main Line.

| Terminus | Trip time | Tph | Fleet size |

| East Garden City | 0:37 | 12 | 19 |

| Suffern (via Paterson) | 0:52 | 6 | 6 |

| Suffern (via Radburn) | 0:49 | 6 | 5 |

| Spring Valley | 0:52 | 6 | 6 |

| Nyack | 0:53 | 6 | 6 |

| Tottenville | 0:47 | 12 | 19 |

| Port Ivory | 0:28 | 12 | 12 |

This is an extra 73 trainsets, for a total of 452.

Further lines

Most of my maps also depict a Line 6 through-tunnel, connecting East Side Access with Hoboken and completely separating the Morris and Essex system from the Northeast Corridor. This only adds trains in New Jersey, including 6 on the M&E system (say, all turning at Summit, roughly at the outer end of high-density suburbanization), and presumably 6 on the Raritan Valley Line (all turning at Raritan or even closer in, such as at Westfield) and 12 on the Northeast Corridor and North Jersey Coast Line (say, 6 to Jersey Avenue, 3 to Long Branch, and 3 to Bay Head). This adds a total of 37 trainsets. As a sanity check, this is really half a line – all timetables, including the 3-line one, assume East Side Access exists – and the 5-line system with its extra 73 trainsets really only adds 2.5 half-lines (the Harlem Line and 5-minute Atlantic Branch service preexist) and those lines are shorter than average.

More speculative is a Line 7, connecting the Lower Montauk Line with an entirely new route through Manhattan to add capacity to New Jersey; this is justified by high commuter volumes from the Erie lines, which under the 6-line system have the highest present-day commute volume to New York divided by peak service. On the Long Island side, it entails restoring through-service to the West Hempstead Branch instead of reducing it to a dinky, changing a 4-trainset shuttle line into a 19-trainset ((36+10)*2*12/60) through-line, and also doubling service on the Far Rockaway and Long Beach Branches, adding a total of 20 trainsets, a total of 35 for the half-line. On the New Jersey side, it depends on what the service plan is for the Erie Lines and on what is done with the West Shore Line and the Susquehanna; the number of extra trainsets is likely about 40, making the 7-line system require about 600 trainsets.

If ridership grows to the point that outer tails like Wassaic, Waterbury, Greenport, and Montauk justify through-service, then this adds a handful of trains to each. Every hourly train to Southeast that extends to Wassaic requires slightly more than one extra trainset; every hourly train to Greenport requires 1.5 (thus, half-hourly requires 3); every hourly train to Montauk requires three. Direct service to Waterbury, displacing trains going to New Haven, is slightly less than one trainset per hourly train; the most likely schedule that fits everything else is a peak train every 20 minutes, which requires 2 extra trainsets.

Quick Note: Bureaucratic Legalism in the United States

After I wrote about the absurdly high construction cost of wheelchair accessibility in New York and the equally absurd timeline resulting from said cost, I got some criticism from people I respect, who say, in so many words, that without government by lawsuit, there’s no America. Here, for example, is Alex Block extolling the notion of accessibility as a right, and talking about how consent decrees can compel change.

But in reality, accessibility is never a right. Accessibility is a feature. The law can mandate a right to certain standards, but the practice of accessibility law in the United States is a constant negotiation. The Americans with Disabilities Act mandated full accessibility everywhere – but even the original text included a balancing test based on the cost of compliance. In practice, legacy public transportation providers negotiated extensive grandfather clauses, and in New York the result was an agreement to make 100 key stations accessible by 2020. Right now, the negotiation has been extended to making 95% of the system accessible by 2055.

And this is why adversarial legalism must be viewed as a dead-end. The courts are not expert on matters of engineering or planning, and in recognizing their technical incompetence they remain extremely deferential to the state on matters of fact. If the MTA says “we can’t,” the courts are not going to order the system shut down until it is compliant, nor do they have the ability to personally penalize can’t-do or won’t-do managers. They can impose consent decrees but the people implementing those decrees can remain adversarial and be as difficult as possible when it comes to coordinating plans; the entire system assumes the state cannot function, and delivers as intended.

So as adversarial legalism is thrown into the ashbin of history as it should be, what can replace it? The answer is, bureaucratic legalism. This already has plenty of precedents in the United States:

- Drug approval is a bureaucratic process – the courts were only peripherally involved in the process of corona vaccination policy.

- The US Army Corps of Engineers can make determinations regarding environmental matters, for example the wetlands that the deactivated railway to be restored for South Coast Rail passes through, with professional opinions about mitigations required through Hockomock and Pine Swamp.

- Protection of National Parks is a bureaucratic process: the National Park Service can impose regulations on the construction of infrastructure, and during the planning for the Washington Metro it demanded that the Red Line cross Rock Creek in tunnel rather than above ground to limit visual impact.

- While the ADA is said to be self-enforcing via the courts, in practice many of the accessibility standards in the US, such as ramp slope, maximum gap between train and platform, elevator size, maximum path of travel, and paratransit availability are legislative or regulatory.

Right now, there’s an attempt by the FTA to improve public transit access to people with limited English proficiency. This, too, can be done the right way, that is bureaucratically, or the wrong way, that is through lawsuits. Last year, we wrote a response to an RFI about planning for equity highlighting some practices that would improve legibility to users who speak English poorly. Mandating certain forms of clarity in language to be more legible to immigrants who speak poor English and recommending others on a case-by-case basis does not involve lawsuits. It has no reason to – people who don’t speak the language don’t have access to the courts except through intermediaries, and if intermediaries are needed, then they might as well be a regulator with ethnographic experience.

What’s more, the process of government by lawsuits doesn’t just fail to create value (unless 95% accessibility by 2055 counts as value). It also removes value. The constant worry about what if the agency gets sued leads to kludgy solutions that work for nobody and often create new expected and unexpected problems.

Public Transportation in the Southeastern Margin of Brooklyn

Geographic Long Island’s north and south shores consist of series of coves, creeks, peninsulas, and barrier islands. Brooklyn and Queens, lying on the same island, are the same, and owing to the density of New York, those peninsulas are fully urbanized. In Southeastern Brooklyn, moreover, those peninsulas are residential and commercial rather than industrial, with extensive mid-20th century development. Going northeast along the water, those are the neighborhoods of Manhattan Beach, Gerritsen Beach, Mill Basin, Bergen Beach, Canarsie, Starrett City, and Spring Creek. The connections between them are weak, with no bridges over the creeks, and this affects their urbanism. What kind of public transportation solution is appropriate?

The current situation

The neighborhoods in the southeastern margin of Brooklyn and the southern margin of Queens (like Howard Beach) are disconnected from one another by creeks and bays; transportation arteries, all of which are currently streets rather than subway lines, go north and northwest toward city center. At the outermost margin, those neighborhoods are connected by car along the Shore Parkway, but there is no access by any other mode of transportation, and retrofitting such access would be difficult as the land use near the parkway is parkland and some auto-oriented malls with little to no opportunity for sprawl repair. The outermost street that connects these neighborhoods to one another is Flatlands, hosting the B6 and B82 buses, and if a connection onward to Howard Beach is desired, then one must go one major street farther from the water to Linden, hosting the B15.

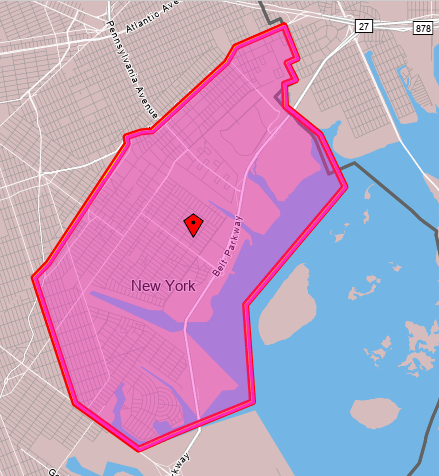

For the purposes of this post, the study area will be in Brooklyn, bounded by Linden, the Triboro/IBX corridor, and Utica:

This is on net a bedroom community. In 2019, it had 85,427 employed residents and 39,382 jobs. Very few people both live and work in this area – only 4,005. This is an even smaller proportion than is typical in the city, where 8% of employed city residents work in the same community board they live in – the study zone is slightly smaller than Brooklyn Community Board 18, but CB 18 writ large also has a lower than average share of in-board workers.

In contrast with the limited extent of in-zone work travel, nearly all employed zone residents, 76,534, work in the city as opposed to its suburbs (and 31,685 of the zone’s 39,382 jobs are held by city residents). Where they work looks like where city workers work in general, since the transportation system other than the Shore Parkway is so radial:

Within the zone, the southwestern areas, that is Mill Basin and Bergen Beach, are vaguely near Utica Avenue, hosting the B46 and hopefully in the future a subway line, first as an extension of the 4 train and later as an independent trunk line.

To the northeast, Canarsie, Starrett City, and Spring Creek are all far from the subway, and connect to it by dedicated buses to an outer subway station – see more details on the borough’s bus map. Canarsie is connected to the L subway station named after it by the B42, a short but high-productivity bus route, and to the 3 and 4 trains at Utica by the B17, also a high-productivity route. Starrett City does not have such strong dedicated buses: it is the outer terminus of the circumferential B82 (which is very strong), but its dedicated radial route, the B83 to Broadway Junction, is meandering and has slightly below-average ridership for its length. Spring Creek is the worst: it is a commercial rather than residential area, anchored by the Gateway Center mall, but the mall is served by buses entering it from the south and not the north, including the B83, the B84 to New Lots on the 3 (a half-hourly bus with practically no ridership), the rather weak B13 to Crescent Street and Ridgewood, and the Q8 to Jamaica.

The implications for bus design

The paucity of east-west throughfares in this area deeply impacts how bus redesign in Brooklyn ought to be done, and this proved important when Eric and I wrote our bus redesign proposal.

First, there are so few crossings between Brooklyn and Queens that the routes crossing between the two boroughs are constrained and can be handled separately. This means that it’s plausible to design separate bus networks for Brooklyn and Queens. In 2018 it was unclear whether they’d be designed separately or together; the MTA has since done them separately, which is the correct decision. The difficulty of crossings argues in favor of separation, and so does the difference in density pattern between the two boroughs: Brooklyn has fairly isotropic density thanks to high-density construction in Coney Island, which argues in favor of high uniform frequency borough-wide, whereas Queens grades to lower density toward the east, which argues in favor of more and less frequent routes depending on neighborhood details.

Second, the situation in Starrett City is unacceptable. This is an extremely poor, transit-dependent neighborhood, and right now its bus connections to the rest of the world are lacking. The B82 is a strong bus route but many rush hour buses only run from the L train west; at Starrett City, the frequency is a local bus every 10-12 minutes and another SBS bus every 10-12 minutes, never overlying to produce high base frequency. The B83 meanders and has low ridership accordingly; it should be combined with the B20 to produce a straight bus route going direct on Pennsylvania Avenue between Starrett City and Broadway Junction, offering neighborhood residents a more convenient connection to the subway.

Third, the situation in Spring Creek is unacceptable as well. Gateway Center is a recent development, dating only to 2002, long after the last major revision of Brooklyn buses. The bus network grew haphazardly to serve it, and does so from the wrong direction, forcing riders into a circuitous route. Only residents of Starrett City have any direct route to the mall, but whereas Starrett City has 5,724 employed residents (south of Flatlands), and Spring Creek has 4,980 workers, only 26 people commute from Starrett City to Spring Creek. It’s far more important to connect Spring Creek with the rest of the city, which means buses entering it from the north, not the south. Our bus redesign proposal does that with two routes: a B6/B82 extension making this and not Starrett City the eastern anchor, and a completely redone B13 going directly north from the mall to New Lots and thence hitting Euclid Avenue on the A/C and Crescent Street on the J/Z.

What about rail expansion?

New York should be looking at subway expansion, and not just Second Avenue Subway. Is subway expansion a good solution for the travel needs of this study zone?

For our purposes, we should start with the map of the existing subway system; the colors indicate deinterlining, but otherwise the system is exactly as it is today, save for a one-stop extension of the Eastern Parkway Line from New Lots to the existing railyard.

Starrett City does not lie on or near any obvious subway expansion; any rail there has to be a tram. But Canarsie is where any L extension would go – in fact, the Canarsie Line used to go there until it was curtailed to its current terminus in 1917, as the trains ran at-grade and grade-separating them in order to run third rail was considered impractically expensive. Likewise, extending the Eastern Parkway Line through the yard to Gateway Center is a natural expansion, running on Elton Street.

Both potential extensions should be considered on a cost per rider basis. In both cases, a big question is whether they can be built elevated – neither Rockaway Parkway nor Elton is an especially wide street most of the way, about 24 or 27 meters wide with 20-meter narrows. The Gateway extension would be around 1.3 km and the Canarsie one 1.8 km to Seaview Avenue or 2.3 km to the waterfront. These should cost around $250 million and $500 million respectively underground, and somewhat less elevated – I’m tempted to say elevated extensions are half as expensive, but this far out of city center, the underground premium should be lower, especially if cut-and-cover construction is viable, which it should be; let’s call it two-thirds as expensive above-ground.

Is there enough ridership to justify such expansion?

Let’s start with Canarsie, which has 28,515 employed residents between Flatlands and the water. Those workers mostly don’t work along the L, which manages to miss all of the city’s main job centers, but the L does have good connections to lines connecting to Downtown Brooklyn (A/C), Lower Manhattan (A/C again), and Midtown (4/5/6, N/Q/R/W, F/M, A/C/E). Moreover, the density within the neighborhood is uniform, and so many of the 28,515 are not really near where the subway would go – Rockaway/Flatlands, Rockaway/Avenue L, Rockaway/Seaview, and perhaps Belt Parkway for the waterfront. Within 500 meters of Rockaway/L and Rockaway/Seaview there are only 9,602 employed residents, but then it can be expected that nearly all would use the subway.

The B42 an B17 provide a lower limit to the potential ridership of a subway extension. The subway would literally replace the B42 and its roughly 4,000 weekday riders; nearly all of the 10,000 riders of the B17 would likely switch as well. What’s more, those buses were seeing decreases in ridership even before corona due to traffic and higher wages inducing people to switch away from buses – and in 2011, despite high unemployment, those two routes combined to 18,000 weekday riders.

If that’s the market, then $500 million/18,000 weekday riders is great and should be built.

Let’s look at Gateway now. Spring Creek has 4,980 workers, but first of all, only 3,513 live in the city. Their incomes are very low – of the 3,513, only 1,030, or 29%, earned as much as $40,000/year in 2019 – which makes even circuitous mass transit more competitive with cars. There’s a notable concentration of Spring Creek workers among people living vaguely near the 3/4 trains in Brooklyn, which may be explained by the bus connections; fortunately, there’s also a concentration among people living near the proposed IBX route in both Brooklyn and Queens.

The area is the opposite of a bedroom community, unlike the other areas within the study zone – only 1,114 employed people live in it. Going one block north of Flatlands boosts this to 1,923, but a block north of Flatlands it’s plausible to walk to a station at Linden at the existing railyard. 51% of the 1,114 and 54% of the 1,923 earn at least $40,000 a year. Beyond that, it’s hard to see where neighborhood residents work – nearly 40% work in the public sector and OnTheMap’s limitations are such that many of those are deemed to be working at Brooklyn Borough Hall regardless of their actual commute destination.

There’s non-work travel to such a big shopping center, but there are grounds to discount it. It’s grown around the Shore Parkway, and it’s likely that every shopper in the area who can afford a car drives in; in Germany, with generally good off-peak frequency and colocation of retail at train stations, the modal split for public transit is lower for shopping trips than for commutes to work or school. Such trips can boost a Gateway Center subway extension but they’re likely secondary, at least in the medium run.

The work travel to the mall is thankfully on the margin of good enough to justify a subway at $50,000/daily trip, itself a marginal cost. Much depends on IBX, which would help deliver passengers to nearby subway nodes, permitting such radial extensions to get more ridership.

Adversarial Legalism and Accessibility

New York State just announced that per the result of a legal settlement, it is committing to make 95% of the subway accessible… by 2055. Every decade, 80-90 stations will be made accessible, out of 472. Area advocates for disability rights are elated; in addition to those cited in the press release or in the New York Times article covering the news, Effective Transit Alliance colleague Jessica Murray speaks of it as a great win and notes that, “The courts are the only true enforcement mechanism of the Americans with Disabilities Act.” But to me, it’s an example not of the success of the use of the courts for civil rights purposes, in what is called adversarial legalism, but rather its failure. The timeline is a travesty and the system of setting the government against itself with the courts as the ultimate arbiter must be viewed as a dead-end and replaced with stronger administration.

The starting point for what is wrong is that 2055 is, frankly, a disgrace. By the standards of most other old urban metro systems, it is a generation behind. In Berlin, where the U-Bahn opened in 1902, two years before the New York City Subway did, there has been media criticism of BVG for missing its 2022 deadline for full accessibility; 80% of the system is accessible, and BVG says that it will reach 100% in 2024. Madrid is slower, planning only for 82% by 2028, with full accessibility possible in the 2030s. Barcelona is 93% accessible and is in the process of retrofitting its remaining stations. Milan has onerous restrictions such that only one wheelchair user may board each train, but the majority of stations have elevators, and 76% have elevators or stairlifts. In Tokyo, Toei is entirely accessible, and so is nearly the entirety of Tokyo Metro. Even London is 40% accessible, somewhat ahead of New York. Only Paris stands as a less accessible major world metro system.

The primary reason for this is costs. The current program to make 81 stations accessible by 2025 is $5.2 billion. This is $64 million per station, and nearly all are single-line stations requiring three elevators, one between the street and the outside of fare control and one from just inside fare control to each of two side platforms. Berlin usually only requires one elevator as it has island platforms and no fare barriers, but sometimes it needs two at stations with side platforms, and the costs look like 1.5-2 million € per elevator. Madrid the cost per elevator is slightly higher, 3.2 million €. New York, in contrast, spends $20 million, so that a single station in New York is comparable in scope to the entirety of the remainder of the Berlin U-Bahn.

And this is what adversarial legalism can’t fix. The courts can compel the MTA to install elevators, but have no way of ensuring the MTA do so efficiently. They can look at capital plans and decree that a certain proportion be spent on accessibility; seeing $50 billion five-year capital plans, they can say, okay, you need to spend 5-10% of that on subway accessibility. But if the MTA says that a station costs $64 million to retrofit and therefore there is no room in the budget to do it by 2030, the courts have to defer.

This, in turn, is a severe misjudgment of what the purpose of civil rights legislation is. Civil rights laws giving individuals and classes the right to sue the government already presuppose that the government may be racist, sexist, or ableist. This is why they confer individual and group rights to sue under Title VI (racial equality in transportation and other facilities), Title IX (gender equality in education), and the ADA. If the intention was to defer to the judgment of government agencies, no such laws would be necessary.

And yet, the nature of adversarial legalism is that on factual details, courts are forced to defer to government agencies. If the MTA says it costs $64 million to retrofit a station, the courts do not have the power to dismiss managers and hire people who can do it for $10 million. If the MTA says it has friction with utilities, the courts cannot compel the utilities to stop being secretive and share the map of underground infrastructure in the city or to stop being obstructive and start cooperating with the MTA’s contractors when they need to do street work to root an elevator. Judges are competent in legal analysis and incompetent in planning or engineering, and this is the result.

Worse, the adversarial process encourages obstructive behavior. The response to any request from the public or the media soon becomes “make me”; former Capital Construction head and current MTA head Janno Lieber said “file a Freedom of Information request” to a journalist who asked what 400 questions federal regulators asked regarding congestion pricing. Nothing goes forward this way, unless accessibility in 33 years counts, and it shouldn’t.

How Many Tracks Do Train Stations Need?

A brief discussion on Reddit about my post criticizing Penn Station expansion plans led me to write a very long comment, which I’d like to hoist to a full post explaining how big an urban train station needs to be to serve regional and intercity rail traffic. The main principles are,

- Good operations can substitute for station size, and it’s always cheaper to get the system to be more reliable than to build more tracks in city center.

- Through-running reduces the required station footprint, and this is one of the reasons it is popular for urban commuter rail systems.

- The simpler and more local the system is, the fewer tracks are needed: an urban commuter rail system running on captive tracks with no sharing tracks with other traffic and with limited branching an get away with smaller stations than an intercity rail station featuring trains from hundreds of kilometers away in any direction.

The formula for minimum headways

On subways, where usually the rush hour crunches are the worst, trains in large cities run extremely frequently, brushing up against the physical limitation of the tracks. The limit is dictated by the brick wall rule, which states that the signal system must at any point assume that the train ahead can turn into a brick wall and stop moving and the current train must be able to brake in time before it reaches it. Cars, for that matter, follow the same rule, but their emergency braking rate is much faster, so on a freeway they can follow two seconds apart. A metro train in theory could do the same with headways of 15 seconds, but in practice there are stations on the tracks and dealing with them requires a different formula.

With metro-style stations, without extra tracks, the governing formula is,

Platform clearing time is how long it takes the train to clear its own length; the idea of the formula is that per the brick wall rule, the train we’re on needs to begin braking to enter the next station only after the train ahead of ours has cleared the station.

But all of this is in theory. In practice, there are uncertainties. The uncertainties are almost never in the stopping or platform clearing time, and even the dwell time is controllable. Rather, the schedule itself is uncertain: our train can be a minute late, which for our purpose as passengers may be unimportant, but for the scheduler and dispatcher on a congested line means that all the trains behind ours have to also be delayed by a minute.

What this means that more space is required between train slots to make schedules recoverable. Moreover, the more complex the line’s operations are, the more space is needed. On a metro train running on captive tracks, if all trains are delayed by a minute, it’s really not a big deal even to the control tower; all the trains substitute for one another, so the recovery can be done at the terminal. On a mainline train running on a national network in which our segment can host trains to Budapest, Vienna, Prague, Leipzig, Munich, Zurich, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, and Paris, trains cannot substitute for one another – and, moreover, a train can be easily delayed 15 minutes and need a later slot. Empty-looking space in the track timetable is unavoidable – if the schedule can’t survive contact with the passengers, it’s not a schedule but crayon.

How to improve operations

In one word: reliability.

In two words: more reliability.

Because the main limit to rail frequency on congested track comes from the variation in the schedule, the best way to increase capacity is to reduce the variation in the schedule. This, in turn, has two aspects: reducing the likelihood of a delay, and reducing the ability of a delay to propagate.

Reducing delays

The central insight about delays is that they may occur anywhere on the line, roughly in proportion to either trip time or ridership. This means that on a branched mainline railway network, delays almost never originate at the city center train station or its approaches, not because that part of the system is uniquely reliable, but because the train might spend five minutes there out of a one-hour trip. The upshot is that to make a congested central segment more reliable, it is necessary to invest in reliability on the entire network, most of which consists of branch segments that by themselves do not have capacity crunches.

The biggest required investments for this are electrification and level boarding. Both have many benefits other than schedule reliability, and are underrated in Europe and even more underrated in the United States.

Electrification is the subject of a TransitMatters report from last year. As far as reliability is concerned, the LIRR and Metro-North’s diesel locomotives average about 20 times the mechanical failure rate of electric multiple units (source, PDF-pp. 36 and 151). It is bad enough that Germany is keeping some outer regional rail branches in the exurbs of Berlin and Munich unwired; that New York has not fully electrified is unconscionable.

Level boarding is comparable in its importance. It not only reduces dwell time, but also reduces variability in dwell time. With about a meter of vertical gap between platform and train floor, Mansfield has four-minute rush hour dwell times; this is the busiest suburban Boston commuter rail station at rush hour, but it’s still just about 2,000 weekday boardings, whereas RER and S-Bahn stations with 10 time the traffic hold to a 30-second standard. This also interacts positively with accessibility: it permits passengers in wheelchairs to board unaided, which both improves accessibility and ensures that a wheelchair user doesn’t delay the entire train by a minute. It is fortunate that the LIRR and (with one peripheral exception) Metro-North are entirely high-platform, and unfortunate that New Jersey Transit is not.

Reducing delay propagation

Even with reliable mechanical and civil engineering, delays are inevitable. The real innovations in Switzerland giving it Europe’s most reliable and highest-use railway network are not about preventing delays from happening (it is fully electrified but a laggard on level boarding). They’re about ensuring delays do not propagate across the network. This is especially notable as the network relies on timed connections and overtakes, both of which require schedule discipline. Achieving such discipline requires the following operations and capital treatments:

- Uniform timetable padding of about 7%, applied throughout the line roughly on a one minute in 15 basis.

- Clear, non-discriminatory rules about train priority, including a rule that a train that’s more than 30 minutes loses all priority and may not delay other trains at junctions or on shared tracks.

- A rigid clockface schedule or Takt, where the problem sections (overtakes, meets, etc.) are predictable and can receive investment. With the Takt system, even urban commuter lines can be left partly single-track, as long as the timetable is such that trains in opposite directions meet away from the bottleneck.

- Data-oriented planning that focuses on tracing the sources of major delays and feeding the information to capital planning so that problem sections can, again, receive capital investment.

- Especial concern for railway junctions, which are to be grade-separated or consistently scheduled around. In sensitive cases where traffic is heavy and grade separation is too expensive, Switzerland builds pocket tracks at-grade, so that a late train can wait for a slot without delaying cross-traffic.

So, how big do train stations need to be?

A multi-station urban commuter rail trunk can get away with metro-style operations, with a single station track per approach track. However, the limiting factor to capacity will be station dwell times. In cases with an unusually busy city center station, or on a highly-interlinked regional or intercity network, this may force compromises on capacity.

In contrast, with good operations, a train station with through-running should never need more than two station tracks per approach track. Moreover, the two station tracks that each approach track splits into should serve the same platform, so that if there is an unplanned rescheduling of the train, passengers should be able to use the usual platform at least. Berlin Hauptbahnhof’s deep tracks are organized this way, and so is the under-construction Stuttgart 21.

Why two? First, because it is the maximum number that can serve the same platform; if they serve different platforms, it may require lengthening dwell times during unscheduled diversions to deal with passenger confusion. And second, because every additional platform track permits, in theory, an increase in the dwell time equal to the minimum headway. The minimum headway in practice is going to be about 120 seconds; at rush hour Paris pushes 32 trains per hour on the shared RER B and D trunk, which is not quite mainline but is extensively branched, but the reliability is legendarily poor. With a two-minute headway, the two-platform track system permits a straightforward 2.5-minute dwell time, which is more than any regional railway needs; the Zurich S-Bahn has 60-second dwells at Hauptbahnhof, and the Paris RER’s single-level trains keep to about 60 seconds at rush hour in city center as well.

All of this is more complicated at a terminal. In theory the required number of tracks is the minimum turn time divided by the headway, but in practice the turn time has a variance. Tokyo has been able to push station footprint to a minimum, with two tracks at Tokyo Station on the Chuo Line (with 28 peak trains per hour) and, before the through-line opened, four tracks on the Tokaido Main Line (with 24). But elsewhere the results are less optimistic; Paris is limited to 16-18 trains per hour at the four-track RER E terminal at Saint-Lazare.

At Paris’s levels of efficiency, which are well below global best practices, an unexpanded Penn Station without through-running would still need two permanent tracks for Amtrak, leaving 19 tracks for commuter traffic. With the Gateway tunnel built, there would be four two-track approaches, two from each direction. The approaches that share tracks with Amtrak (North River Tunnels, southern pair of East River Tunnels) would get four tracks each, enough to terminate around 18 trains per hour at rush hour, and the approaches that don’t would get five, enough for maybe 20 or 22. The worst bottleneck in the system, the New Jersey approach, would be improved from today’s 21 trains per hour to 38-40.

A Penn Station with through-running does not have the 38-40 trains per hour limit. Rather, the approach tracks would become the primary bottleneck, and it would take an expansion to eight approach tracks on each side for the station itself to be at all a limit.

The Northeastern United States Wants to Set Tens of Billions on Fire Again

The prospect of federal funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill is getting every agency salivating with desires for outside money for both useful and useless priorities. Northeastern mainline rail, unfortunately, tilts heavily toward the useless, per a deep dive into documents by New York-area activists, for example here and here.

Amtrak is already hiring project management for Penn Station redevelopment. This is a project with no transportation value whatsoever: this is not the Gateway tunnels, which stand to double capacity across the Hudson, but rather a rebuild of Penn Station to add more tracks, which are not necessary. Amtrak’s current claim is that the cost just for renovating the existing station is $6.5 billion and that of adding tracks is $10.5 billion; the latter project has ballooned from seven tracks to 9-12 tracks, to be built on two levels.

This is complete overkill. New train stations in big cities are uncommon, but they do exist, and where tracks are tunneled, the standard is two platform tracks per approach tracks. This is how Berlin Hauptbahnhof’s deep section goes: the North-South Main Line is four tracks, and the station has eight, on four platforms. Stuttgart 21 is planned in the same way. In the best case, each of the approach track splits into two tracks and the two tracks serve the same platform. Penn Station has 21 tracks and, with the maximal post-Gateway scenario, six approach tracks on each side; therefore, extra tracks are not needed. What’s more, bundling 12 platform tracks into a project that adds just two approach tracks is pointless.

This is a combined $17 billion that Amtrak wants to spend with no benefit whatsoever; this budget by itself could build high-speed rail from Boston to Washington.

Or at least it could if any of the railroads on the Northeast Corridor were both interested and expert in high-speed rail construction. Connecticut is planning on $8-10 billion just to do track repairs aiming at cutting 25-30 minutes from the New York-New Haven trip times; as I wrote last year when these plans were first released, the reconstruction required to cut around 40 minutes and also upgrade the branches is similar in scope to ongoing renovations of Germany’s oldest and longest high-speed line, which cost 640M€ as a once in a generation project.

In addition to spending about an order of magnitude too much on a smaller project, Connecticut also thinks the New Haven Line needs a dedicated freight track. The extent of freight traffic on the line is unclear, since the consultant report‘s stated numbers are self-contradictory and look like a typo, but it looks like there are 11 trains on the line every day. With some constraints, this traffic fits in the evening off-peak without the need for nighttime operations. With no constraints, it fits on a single track at night, and because the corridor has four tracks, it’s possible to isolate one local track for freight while maintenance is done (with a track renewal machine, which US passenger railroads do not use) on the two tracks not adjacent to it. The cost of the extra freight track and the other order-of-magnitude-too-costly state of good repair elements, including about 100% extra for procurement extras (force account, contingency, etc.), is $300 million for 5.4 km.

I would counsel the federal government not to fund any of this. The costs are too high, the benefits are at best minimal and at worst worse than nothing, and the agencies in question have shown time and time again that they are incurious of best practices. There is no path forward with those agencies and their leadership staying in place; removal of senior management at the state DOTs, agencies, and Amtrak and their replacement with people with experience of executing successful mainline rail projects is necessary. Those people, moreover, are mid-level European and Asian engineers working as civil servants, and not consultants or political appointees. The role of the top political layer is to insulate those engineers from pressure by anti-modern interest groups such as petty local politicians and traditional railroaders who for whatever reasons could not just be removed.

If federal agencies are interested in building something useful with the tens of billions of BIL money, they should instead demand the same results seen in countries where the main language is not English, and staff up permanent civil service run by people with experience in those countries. Following best industry practices, $17 billion is enough to renovate the parts of the Northeast Corridor that require renovation and bypass those that require greenfield bypasses; even without Gateway, Amtrak can squeeze a 16-car train every 15 minutes, providing 4,400 seats into Penn Station in an hour, compared with around 1,700 today – and Gateway itself is doable for low single-digit billions given better planning and engineering.

Systemic Investments in the New York City Subway

Subway investments can include expansion of the map of lines, for example Second Avenue Subway; proposals for such extensions are affectionately called crayon, a term from London Reconnections that hopped the Pond. But they can also include improvements that are not visible as lines on a map, and yet are visible to passengers in the form of better service: faster, more reliable, more accessible, and more frequent.

Yesterday I asked on Twitter what subway investments people think New York should get, and people mostly gave their crayons. Most people gave the same list of core lines – Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, an extension of the 2 and 5 on Nostrand, an extension of the 4 on Utica, an extension of the N and W to LaGuardia, the ongoing Interborough Express proposal, and an extension of Second Avenue Subway along 125th – but beyond that there’s wide divergence and a lot of people argue over the merits of various extensions. But then an anonymous account that began last year and has 21 followers and yet has proven extremely fluent in the New York transit advocacy conversation, named N_LaGuardia, asked a more interesting question: what non-crayon systemic investments do people think the subway needs?

On the latter question, there seems to be wide agreement among area technical advocates, and as far as I can tell the main advocacy organizations agree on most points. To the extent people gave differing answers in N_LaGuardia’s thread, it was about not thinking of everything at once, or running into the Twitter character limit.

It is unfortunate that many of these features requiring capital construction run into the usual New York problem of excessive construction costs. The same institutional mechanisms that make the region incapable of building much additional extension of the system also frustrate systemwide upgrades to station infrastructure and signaling.

Accessibility

New York has one of the world’s least accessible major metro systems, alongside London and (even worse) Paris. In contrast, Berlin, of similar age, is two-thirds accessible and planned to reach 100% soon, and the same is true of Madrid; Seoul is newer but was not built accessible and retrofits are nearly complete, with the few remaining gaps generating much outrage by people with disabilities.

Unfortunately, like most other forms of capital construction in New York, accessibility retrofits are unusually costly. The elevator retrofits from the last capital plan were $40 million per station, and the next batch is in theory $50 million, with the public-facing estimates saying $70 million with contingency; the range in the European cities with extensive accessibility (that is, not London or Paris) is entirely single-digit million. Nonetheless, this is understood to be a priority in New York and must be accelerated to improve the quality of universal design in the system.

Platform screen doors

The issue of platform screen doors (PSDs) or platform edge doors (PEDs) became salient earlier this year due to a much-publicized homicide by pushing a passenger onto a train, and the MTA eventually agreed to pilot PSDs at three stations. The benefits of PSDs are numerous, including,

- Safety – there are tens of accident and suicide deaths every year from falling onto tracks, in addition to the aforementioned homicide.

- Greater accessibility – people with balance problems have less to worry about from falling onto the track.

- Capacity – PSDs take up platform space but they permit passengers to stand right next to them, and the overall effect is to reduce platform overcrowding at busy times.

- Air cooling – at subway stations with full-height PSDs (which are rare in retrofits but I’m told exist in Seoul), it’s easier to install air conditioning for summer cooling.

The main difficulty is that PSDs require trains to stop at precise locations, to within about a meter, which requires signaling improvements (see below). Moreover, in New York, trains do not yet have consistent door placement, and the lettered lines even have different numbers of doors sometimes (4 per car but the cars can be 60′ or 75′ long) – and the heavily interlined system is such that it’s hard to segregate lines into captive fleets.

But the biggest difficulty, as with accessibility, is again the costs. In the wake of public agitation for PSDs earlier this year, the MTA released as 2019 study saying only 128 stations could be retrofitted with PSDs, at a cost of $7 billion each, or $55 million per station; in Paris, PSDs are installed on Métro lines as they are being automated, at a cost of (per Wikipedia) 4M€ per station of about half the platform length as in New York.

Signaling improvements