Category: New York

Platform Edge Doors

In New York, a well-publicized homicide by pushing the victim onto the subway tracks created a conversation about platform edge doors, or PEDs; A Train of Thought even mentions this New York context, with photos from Singapore.

In Paris, the ongoing automation of the system involves installing PEDs. This is for a combination of safety and precision. For safety, unattended trains do not have drivers who would notice if a passenger fell onto the track. For precision, the same technology that lets trains run with a high level of automation, which includes driverless operations but not just, can also let the train arrive with meter-scale precision so that PEDs are viable. This means that we have a ready comparison for how much PEDs should cost.

The cost of M4 PEDs is 106 M€ for 29 stations, or 3.7M€ per station. The platforms are 90 meters long; New York’s are mostly twice as long, but some (on the 1-6) are only 70% longer. So, pro-rated to Parisian length, this should be around $10 million per station with two platform faces. Based on Vanshnook’s track map, there are 204 pairs of platform faces on the IRT, 187 on the IND (including the entire Culver Line), and 165 on the BMT (including Second Avenue Subway). So this should be about $5.5 billion, systemwide.

Here is what the MTA thinks it should cost. It projects $55 million per station – but the study is notable in looking for excuses not to do it. Instead of talking about PEDs, it talks about how they are infeasible, categorizing stations by what the excuse is. At the largest group, it is accessibility; PEDs improve accessibility, but such a big station project voids the grandfather clause in the Americans with Disabilities Act that permits New York to keep its system inaccessible (Berlin, of similar age, is approaching 100% accessible), and therefore the MTA does not do major station upgrades until it can extort ADA funding for them.

Then there is the excuse of pre-cast platforms. These are supposed to be structurally incapable of hosting PEDs; in reality, PEDs are present on a variety of platforms, including legacy ones that are similar to those of New York, for example in Paris. (Singapore was the first full-size heavy rail system to have PEDs – in fact it has full-height platform screen doors, or PSDs, at the underground stations – but there are later retrofits in Singapore, Paris, Shanghai, and other cities.)

The trains in New York do not have consistent door placement. The study surprisingly does not mention that as a major impediment, only a minor one – but at any rate, there are vertical doors for such situations.

So there is a solution to subway falls and suicides; it improves accessibility because of accidental falls, and full-height PSDs also reduce air cooling costs at stations. Unfortunately, for a combination of extreme construction costs and an agency that doesn’t really want to build things with its $50 billion capital plans, it will not happen while the agency and its political leaders remain as they are.

The New Triboro/Interboro Plan

Governor Kathy Hochul announced a policy package for New York, and, in between freeway widening projects, there is an item about the Triboro subway line, renamed Interboro and shortened to exclude the Bronx. The item is brief and leaves some important questions unanswered, and this is good – technical analysis should not be encumbered by prior political commitments made ex cathedra. Good transit advocates should support the program as it currently stands and push for swift design work to nail down the details of the project and ensure the decisions are sound.

What is Triboro?

The Bronx Times has a good overview, with maps. The original idea, from the RPA’s Third Regional Plan in the 1990s, was to use various disused or barely-used freight lines, such as the Bay Ridge Branch, to cobble together an orbital subway from Bay Ridge via East New York and Jackson Heights to Yankee Stadium. Only about a kilometer of greenfield tunnel would be needed, at the northern end.

In the Fourth Plan from the 2010s, this changed. The Fourth Plan Triboro was like PennDesign’s Crossboro idea, differing from the Third Plan Triboro in three ways: first, the stop spacing would be wider; second, the technology used would be commuter rail for mainline compatibility and not subway; and third, the Bronx routing would not follow disused tunnels (by then sealed) to Yankee Stadium but go along the Northeast Corridor to Coop City. Years ago, I’ve said that the Fourth Plan Triboro is worse than the Third Plan.

Unlike the RPA Triboro plans, Hochul’s Interboro plan only connects Brooklyn and Queens, running from Jackson Heights to the south. I do not know why, but believe this has to do with right-of-way constraints further north. The Queens-Bronx connection is on Hell Gate Bridge, which has three tracks and room for a fourth (which historically existed), of which Amtrak uses two and CSX uses one; having the service run to the Bronx is valuable but requires figuring out what to do about CSX and track-sharing. The Third Plan version ignored this, which is harder now, in part because freight traffic has increased from effectively zero in the 1990s to light today.

Stop spacing

The stop spacing in the governor’s plan appears to be more express, as in the Fourth Regional Plan, where the service is to run mostly nonstop between subway connections. In contrast, the Third Regional Plan called for regular stop spacing of 800 meters, in line with subway guidelines for new lines, including Second Avenue Subway.

I’m of two minds on this. We can look at formulas derived here in previous years for optimal stop spacing; the formulas are most commonly applied to buses (see here and follow first paragraph links), which can change their stop pattern more readily, but can equally be used for a subway.

The line’s circumferential characteristic gives it two special features, which argue in opposite directions on the issue of stop spacing. On the one hand, trips are likely to be short, because many people are going to use the line as a way of connecting between two subway spokes and those are for the most part placed relatively close to one another; farther-away connections such as end-to-end can be done on a radial line. But on the other hand, trips are not isotropic, because most riders are going to connect to a line, and the stronger the distinguished nodes are on a line, the longer the optimal interstation is.

On this, further research is required and multiple options should be studied. My suspicion is that on balance the longer stop spacing will prove correct, but it’s plausible that the shorter one is better. A hybrid may well be good too, especially in conjunction with a bus redesign ensuring the stops on the new rail link are aligned with bus trunks.

The issue of frequency

The line’s short-hop characteristic has an unambiguous implication about service: it must be very frequent. The average trip length along the line is likely to be short enough, on the order of 15 minutes, that even 10-minute waits are a drag on ridership. Nor is it possible to set up some system of timed transfers to 10-minute subway lines, first of all because the subway does not run on a clockface timetable, and second because the only transfers that could be cross-platform are to the L train.

This means that all-day frequency must be very high, on the order of a train every 5 minutes. This complicates any track-sharing arrangement, because the upper limit of frequency on shared track with trains that run any other pattern is a bit worse than this. The North London Line runs every 10 minutes and shares track with freight, and I believe there are some short shared segments in Switzerland up to a train every 7.5 minutes.

The upshot is that freight can’t run during normal operations. This is mostly fine, there are only 2-4 freight trains a day on the Bay Ridge Branch, where there are segments of the right-of-way that are only wide enough for two tracks, not four. This means if freight is to be retained, it has to run during light periods, such as 5 in the morning or 11 at night, when it’s more acceptable to run passenger trains every 10 minutes and not 5.

Institutional Issues: Dealing with Technological and Social Change

I’ve covered issues of procurement, professional oversight, transparency, and proactive regulations so far. Today I’m going to cover a related institutional issue, regarding sensitivity to change. It’s imperative for the state to solve the problems of tomorrow using the tools that it expects to have, rather than wallowing in the world of yesterday. To do this, the civil service and the political system both have to be sensitive to ongoing social, economic, and technological changes and change their focus accordingly.

Most of this is not directly relevant to construction costs, except when changes favor or disfavor certain engineering methods. Rather, sensitivity to change is useful for making better projects, running public transit on the alignments where demand is or will soon be high using tools that make it work optimally for the travel of today and tomorrow. Sometimes, it’s the same as what would have worked for the world of the middle of the 20th century; other times, it’s not, and then it’s important not to get too attached to nostalgia.

Yesterday’s problems

Bad institutions often produce governments that, through slowness and stasis, focus on solving yesterday’s problems. Good institutions do the opposite. This problem is muted on issues that do not change much from decade to decade, like the political debate over overall government spending levels on socioeconomic programs. But wherever technology or some important social aspect changes quickly, this problem can grow to the point that outdated governance looks ridiculous.

Climate change is a good example, because the relative magnitudes of its various components have shifted in the last 20 years. Across the developed world, transportation emissions are rising while electricity generation emissions are falling. In electricity generation, the costs of renewable energy have cratered to the point of being competitive from scratch with just the operating costs of fossil and nuclear power. Within renewable energy, the revolution has been in wind (more onshore than offshore) and utility-scale solar, not the rooftop panels beloved by the greens of last generation; compare Northern Europe’s wind installation rates with what seemed obvious just 10 years ago.

I bring this up because in the United States today, the left’s greatest effort is spent on the Build Back Better Act, which they portray as making the difference between climate catastrophe and a green future, and which focuses on the largely solved problem of electricity. Transportation, which overtook electricity as the United States’ largest source of emissions in the late 2010s, is shrugged off in the BBB, because the political system of 2021 relitigates the battles of 2009.

This slowness cascades to smaller technical issues and to the civil service. A slow civil service may mandate equity analyses that assume that the needs of discriminated-against groups are geographic – more transit service to black or working-class neighborhoods – because they were generations ago. Today, the situation is different, and the needs are non-geographic, but not all civil service systems are good at recognizing this.

The issue of TOD

Even when the problem is static, for example how to improve public transit, the solutions may change based on social and technological changes.

The most important today is the need to integrate transportation planning with land use planning better. Historically, this wasn’t done much – Metro-land is an important counterexample, but in general, before mass motorization, developers built apartments wherever the trains went and there was no need for public supervision. The situation changed in the middle of the 20th century with mass competition with the automobile, and thence the biggest successes involved some kind of transit-oriented development (TOD), built by the state like the Swedish Million Program projects in Stockholm County or by private developer-railroads like those of Japan. Today, the default system is TOD built by private developers on land released for high-density redevelopment near publicly-built subways.

Some of the details of TOD are themselves subject to technological and social change:

- Deindustrialization means that city centers are nice, and waterfronts are desirable residential areas. There is little difference between working- and middle-class destinations, except that city center jobs are somewhat disproportionately middle-class.

- Secondary centers have slowly been erased; in New York, examples of declining job centers include Newark, Downtown Brooklyn, and Jamaica.

- Conversely, there is job spillover from city center to near-center areas, which means that it’s important to allow for commercialization of near-center residential neighborhoods; Europe does this better than the United States, which is why at scale larger than a few blocks, European cities are more centralized than American ones, despite the prominent lack of supertall office towers. Positive New York examples include Long Island City and the Jersey City waterfront, both among the most pro-development parts of the region.

- Residential TOD tends to be spiky: very tall buildings near subway stations, shorter ones farther away. Historic construction was more uniformly mid-rise. I encourage the reader to go on some Google Earth or Streetview tourism of a late-20th century city like Tokyo or Taipei and compare its central residential areas with those of an early-20th century one like Paris or Berlin.

The ideal civil service on this issue is an amalgamation of things seen in democratic East Asia, much of Western and Central Europe, and even Canada. Paris and Stockholm are both pretty good about integrating development with public transit, but only in the suburbs, where they build tens of thousands of housing units near subway stations. In their central areas, they are too nostalgic to redevelop buildings or build high-rises even on undeveloped land. Tokyo, Seoul, and Taipei are better and more forward-looking.

Public transit for the future

Besides the issue of TOD, there are details of how public transportation is built and operated that change with the times. The changes are necessarily subtle – this is mature technology, and VC-funded businesspeople who think they’re going to disrupt the industry invariably fail. This makes the technology ideal for treatment by a civil service that evolves toward the future – but it has to evolve. The following failures are regrettably common:

- Overfocus on lines that were promised long ago. Some of those lines remain useful today, and some are underrated (like Berlin’s U8 extension to Märkisches Viertel, constantly put behind higher cost-per-rider extensions in the city’s priorities). But some exist out of pure inertia, like Second Avenue Subway phases 3-4, which violates two principles of good network design.

- Proposals that are pure nostalgia, like Amtrak-style intercity trains running 1-3 times per day at average speeds that would shame most of Eastern Europe. Such proposals try to fit to the urban geography of the world of yesterday. In Germany, the coalition’s opposition to investment in high-speed rail misses how in the 21st century, German urban geography is majority-big city, where a high-speed rail network would go.

- Indifference to recent news relevant to the technology. Much of the BART to San Jose cost blowout can still be avoided if the agency throws away the large-diameter single-bore solution, proposed years ago by people who had heard of its implementation in Barcelona on L9 but perhaps not of L9’s cost overruns, making it by far Spain’s most expensive subway. In Germany, the design of intercity rail around the capabilities of the trains of 25 years ago falls in this category as well; technology moves on and the ongoing investments here work much better if new trains are acquired based on the technology of the 2020s.

- Delay in implementation of easy technological fixes that have been demonstrated elsewhere. In a world with automatic train-mounted gap fillers, there is no excuse anywhere for gaps between trains and platforms that do not permit a wheelchair user to board the train unaided.

- Slow reaction time to academic research on best practices, which can cover issues from timetabling to construction methods to pricing to bus shelter.

Probably the most fundamental issue of sensitivity to social change is that of bus versus rail modal choice. Buses are labor-intensive and therefore lose value as the economy grows; the high-frequency grid of 1960s Toronto could not work at modern wages, hence the need to shift public transit from bus to rail as soon as possible. This in turn intersects with TOD, because TOD for short-stop surface transit looks uniformly mid-rise rather than spiky. The state needs to recognize this and think about bus-to-rail modal shift as a long-term goal based on the wages of the 21st century.

The swift state

In my Niskanen piece from earlier this year, I used the expression building back, quickly, and made references to acting swiftly and the swift state. I brought up the issue of speeding up the planning lead time, such as the environmental reviews, as a necessary component for improving infrastructure. This is one component of the swift state, alongside others:

- Fast reaction to new trends, in technology, where people travel, etc. Even in deeply NIMBY areas like most of the United States, change in urban geography is rapid: job centers shift, new cities that are less NIMBY grow (Nashville’s growth rates should matter to high-speed rail planning), and connections change over time.

- Fast rulemaking to solve problems as they emerge. This means that there should be fewer layers of review; a civil servant should be empowered to make small decisions, and even the largest decisions should be delegated to a small expert team, intersecting with my previous posts about civil service empowerment.

- Fast response time to civil complaints. It’s fine to ignore a nag who thinks their property values deserve state protection, but if people complain about noise, delays, slow service, poor UI, crime, or sexism or racism, take them seriously. Look for solutions immediately instead of expecting them to engage in complex nonprofit proof-of-work schemes to show that they are serious. The state works for the people, and not the other way around.

- Constant amendment of priorities based on changes in the rest of society. A state that wishes to fight climate change must be sensitive to what the most pressing sources of emissions are and deal with them. If you’re in a mature urban or national economy, and you’re not frustrating nostalgics who show you plans from the 1950s, you’re probably doing something wrong.

In all cases, it is critical to build using the methods of the world of today, aiming to serve the needs of the world of tomorrow. Those needs are fairly predictable, because public transit is not biotech and changes therein are nowhere near as revolutionary as mRNA and viral vector vaccines. But they are not the same as the needs of 60 years ago, and good institutions recognize this and base their budgetary and regulatory focus on what is relevant now and not what was relevant when color TVs were new.

Institutional Issues: Procurement

This is the start of a multi-post series, of undecided length, focusing on institutional, managerial, and sociopolitical issues that govern the quality of infrastructure. I expect much of the content to also appear in our upcoming construction costs report, with more examples, but this is a collation of the issues that I think are most pertinent at the current state of our work.

Moreover, in this and many posts in the series, the issues covered affect both price and quality. These are not in conflict: the same institutions that produce low construction costs also produce rigorous quality of infrastructure. The tradeoffs between cost and quality are elsewhere, in some (not all) aspects of engineering and planning.

The common theme of much (but not all) of this runs through procurement. It’s not as exciting as engineering or architecture or timetables – how many railfans write contracts and contracting regulations for fun? – but it’s fundamental to a large fraction of the difference in construction costs between different countries. Some of the subheadings in this post deserve full treatments by themselves later, and thus this writeup is best viewed as an introductory overview of how things tie together.

What is procurement?

Procurement covers all issues of how the state contracts with providers of goods and services. In the case of public transportation, these goods and services may include consulting services, planning, design, engineering, construction services, equipment, materials, and operating concessions. The providers are almost always private-sector, but they can also be public companies in some cases – for example, Milan Metro provides consulting services for other Italian cities and Delhi Metro does for other Indian ones, and state-owned companies like RATP, SNCF/Keolis, and DB/Arriva sometimes bid on private contracts abroad.

The contracting process can be efficient, or it can introduce inefficiencies into the system. In the worst case I know of, that of New York, procurement problems alone can double the cost of a contract, independently of any other issue of engineering, utilities, labor, or management quality. In contrast, low-cost examples lack any such inefficiencies in construction.

The issue of oversight

On the list of services that are procured, some are more commonly contracted out than others. Construction is as far as I can tell always bid out to private-sector competition, including equipment (nobody makes their own trains), materials, and physical construction. Design and engineering may be contracted out to consultants, depending on the system. Planning never is anywhere I know of, except some unusually high-cost American examples in which public-sector planning has been hollowed out.

The best practice from Southern Europe as well as Scandinavia is that planning and oversight always stay with the public sector. Even with highly privatized contracts, there’s active in-house oversight over the entire process.

The issue of competition

It is necessary to ensure there’s healthy competition between contractors. This requires casting as wide a net as possible. This is easier to do in environments where there is already extensive private- and public-sector construction going on: Turkey builds about 1 million dwellings a year and many bridges, highways, and rail lines, and therefore has a thick domestic market. In Turkish law, it is required that every public megaproject procurement get at least three distinct bids, or else it must be rebid. This rule is generally easy to satisfy in the domestic market.

But if the domestic market is not enough, it is necessary to go elsewhere. This is fine – foreign bidders are common where they are allowed to participate, always with local oversight. Turkish contractors in Northern Europe are increasingly common, following all of the local labor laws, often partnering with a domestic firm.

Old boy networks, in which contractors are required to have a preexisting relationship with the client, are destructive. They lead to groupthink and stagnation. A Turkish contractor held an Android in front of me and, describing work in Sweden, said, “If a Swede said it’s an iPhone, the Swedes would accept that it’s an iPhone, but if I did, they’d check, and see it’s an Android.” In Sweden at least the domestic system is functional, but in a high-cost environment, it is critical to look elsewhere and let foreigners outcompete domestic business.

It is even more important to make sure the experience of bidding on public contracts is positive. A competent contractor has a choice of clients, and a nightmare client will soon lose its business. Such a loss is triple. First, the contractor would have done a good job at an affordable price. Second, the negative experience, such as micromanagement or stalling, is likely to increase costs and reduce the quality of work. And third, the loss of any contractor reduces competition. In the United States, we have repeatedly heard this complaint from contractors and their representatives, that they always have to deal with the “agency factor,” where the agency can be the MTA or any other transit agency, making things difficult and leading to higher bids.

Good client-contractor relations

The issue of avoiding being a nightmare client deserves special scrutiny. It is critical for agencies to make sure to be pleasant clients. This includes any of the following principles:

- Do not change important regulations midway through the project. In Stockholm, the otherwise-good Nya Tunnelbana project has had cost overruns due to new environmental regulations that required disposal of waste rock to the standards of toxic waste, introducing new costs of transportation.

- Avoid difficult change order process (see below for more details on itemization). It should be everyone against the project, not the agency against the contractors or one contractor against another.

- Avoid any weird process or requirements. The RFPs should look like what successful international contractors are used to; this has been a recent problem of American rolling stock procurement, which has excessively long RFPs defining what a train is, rather than the most standard documents used in Europe. This rule is especially important for peripheral markets, such as the entire United States – the contractor knows what they’re doing better than you, so you should adapt to them.

- Require some experience and track record to evaluate a bid, but do not require local experience. A contractor with extensive foreign experience may still be valuable: Israel’s rail electrification went to such a contractor, SEMI, and the results are positive in the sense that the bid was well below expectations and the only problems stem from a nuisance lawsuit launched by a competitor that bid higher and felt entitled to the contract.

- For a complex contract, the best practice here is to have an in-house team score every proposal for technical merit and make that the primary determinant of the final score, not cost. Across most of the low- and medium-cost examples we have looked at, the technical score is 50-70% of the total and cost 30-50%.

- Do not micromanage. New York’s lowest bid rules lead to a thick book of regulations that force the bids to be as similar to one another as possible in quantity and type of goods, to the point of telling contractors what materials they are allowed to use. This is bad practice. Oversight should always be done with flexibility and competent in-house engineers working in conversation with the stakeholders and never with a long checklist of rules.

Flexibility

Contracts should permit as much flexibility as practical, to allow contractors to take advantage of circumstances for everyone’s benefits and get around problems. This is especially important for underground construction and for construction in a constrained city, where geotechnical surprises are inevitable.

Most of the English-speaking world, and some parts of the rest (Copenhagen, to some extent Grand Paris Express) interpret flexibility to mean design-build (DB) contracts, in which the same firm is given a large contract to both design a project and then build it. However, DB is not used in the lowest-cost examples I know of, and rarely in medium-cost ones. If design is contracted out, then there are almost always two contracts, in what is called design-bid-build (DBB). Sources in Sweden say they use single build contracts, but they often use consultants for supplementary engineering and thus they are in practice DBB; Italy is DBB; Turkish sources claim to do design-build, but in reality there are two contracts, one for 60% design and another for going to 100% and then doing construction.

The Turkish system is a good example of how to ensure flexibility. Because the construction contractor is responsible for the finalized (but not most) design, it is possible to make little changes as needed based on market or in-the-ground conditions. In Italy and Spain, the DBB system is traditional, but the building contractor is allowed to propose changes and the in-house oversight team will generally approve them; this is also how the more functional American DBB contracts work, typically for small projects such as individual train stations, which are within the oversight capacity of the existing in-house teams.

DBB can be done inflexibly – that is, wrong – and often when this happens, everyone gets a bitter taste and comes out with the impression that DB is superior. If the building contractor has to go through onerous process to vary from the design, or is excessively incentivized to follow the design to the letter, then problems will occur.

One example of inflexibility comes from Norway. Norwegian construction costs are generally low, but the Fornebu Line’s cost is around $200 million/km, which is not as low as some other Nordic lines. Norway uses DBB, but its liability system incentivizes rigidly adhering to the design: any defect in the construction is deemed to be the designer’s fault if the builder followed the design exactly but the builder’s fault if the builder made any variation. This means small changes do not occur, and then the design consultants engage in defensive design, rather than letting the building contractor see later what risks are likely based on meter-scale geology.

Itemization and change orders

Change orders, and defensive design therefor, are a huge source of cost overruns and acrimony. Moreover, because of the risks involved, any cost overruns are transmitted back into the overall budget – that is, every attempt to clamp down on overruns will just increase absolute costs, as bidders demand more money in risk compensation. California is infamous for the way change orders drive up costs. New York only avoids that by imposing large and growing risk on the bidders (including, recently, a counterproductive blacklisting system called disbarment, a misplaced effort by Andrew Cuomo to rein in cost overruns); the bidders respond by bidding much higher.

Instead of the above morass, contracts should be itemized rather than lump-sum. The costs of materials are determined by the global, national, and local markets, and the contractor has little control over them; in fact, one of the examples an American source gave me of functional change orders in a DBB system is that the bench at a train station can be made of wood, metal, or another material, depending on what costs the least when physical construction happens.

Labor costs depend on large-scale factors as well, including market conditions and union agreements. The use of union labor ensures that the wages and benefits of the workers are known in advance and therefore unit costs can be written into the contract easily. Spain essentially turns contracts into cost-plus: costs depend on items as bid and as required by inevitable changes, and there is a fixed profit rate based on a large amount of competition between different construction firms.

The upshot is that itemized costs prevent the need to individually negotiate changes. If difficult ground conditions or unexpected utilities slow down the work, the wages of the workers during the longer construction period are already known. It is especially important to avoid litigation and the threat thereof – questions of engineering should be resolved by engineers, not lawyers.

Here, our results, based on qualitative interviews with industry experts, mirror some quantitative work in economics, including Ryan and Bolotnyy-Vasserman. Itemization reduces risk because it pre-decides some of the disputes that may arise, and therefore the required profit rate to break even net of risk is lower, reducing overall cost.

The impact of bad procurement practices

One of our sources told us that procurement problems add up to a factor of 2 increase in New York construction costs. Five specific problems of roughly equal magnitude were identified:

- A regulation for minority- and woman-owned businesses (MWB), which none of the pre-qualified contractors in the old boy network is.

- The MTA factor.

- Change order risk.

- Disbarment risk.

- Profit in a low-competition environment.

MWB and disbarment are New York-specific, but the other three appear US-wide. In California, the change order risk is if anything worse, judging by routine cost overruns coming from change orders. California, moreover, is very rigid whenever a contractor suggests design improvements, as Dragados did for its share of California High-Speed Rail, even while giving contracts to contractors that engage in nuisance change orders like Tutor Perini.

Aligning American procurement practice with best practice is therefore likely to halve construction costs across the board, and substantially reduce equipment costs due to better competition and easier contractor-client relations.

The Other People’s Money Problem

I did a poll on Patreon about cost issues to write about. This is the winning option, with 12 votes; project- vs. budget-driven plans came second with 11 and I will blog about it soon, whereas neighborhood empowerment got 8.

OPM, or other people’s money, is a big impediment to cost reform. In this context, OPM refers to any external infusion of money, typically from a higher-level government from that controlling an agency. Any municipal or otherwise local agency, not able or willing to raise local taxes to fund itself, will look for external grants, for example in a federal budget. The situation then is that the federal grantor gives money but isn’t involved in the design of where the money goes to, leading to high costs.

OPM at ground level

Local and regional advocates love OPM. Whenever they want something, OPM lets them have it without thinking in terms of tradeoffs. Want a new piece of infrastructure, including everything the local community groups want, with labor-intensive methods that also pay the wages the unions hop for? OPM is for you.

This was a big problem for the Green Line Extension’s first iteration. Somerville made ridiculous demands for signature stations and even a bike path (“Somerville Community Path”) thrown in – and all of these weren’t jut extra scope but also especially expensive, since the funding came from elsewhere. The Community Path, a 3 km bike path, was budgeted at $100 million. The common refrain on this is “we don’t care, it’s federally funded.” Once there’s an outside infusion of money, there is no incentive to spend it prudently.

OPM modifying projects

In capital construction, OPM can furthermore lead to worse projects, designed to maximize OPM rather than benefits. Thus, not only are costs high, but also the results are deficient. In my experience talking to New Englanders, this takes the form of trying to vaguely connect to a politician’s set of petty priorities. If a politician wants something, the groups will try pitching a plan that is related to that something as a sales pitch. The system thus encourages advocates and local agencies to invest in buying politicians rather than in providing good service.

This kind of behavior can persist past the petty politician’s shelf life. To argue their cases, advocates sometimes claim that their pet project is a necessary component of the petty politician’s own priority. Then the petty politician leaves and is replaced by another, but by now, the two projects have been wedded in the public discourse, and woe betide any advocate or civil servant who suggests separating them. With a succession of petty politicians, each expressing interest in something else, an entire ecosystem of extras can develop, compromising design at every step while also raising costs.

The issue of efficiency

In the 1960s, the Toronto Transit Commission backed keeping a law requiring it to fund its operations out of fares. The reason was fear of surplus extraction: if it could receive subsidies, workers could use this as an excuse to demand higher wages and employment levels, and thus the subsidy would not go to more service. As it is, by 1971 this was untenable and the TTC started getting subsidies anyway, as rising market wages required it to keep up.

In New York, the outcome of the cycle of more subsidies and less efficiency is clearer. Kyle Kirschling’s thesis points out on PDF-p. 106 that New York City Transit’s predecessors, the IRT and BMT, had higher productivity measured in revenue car-km per employee in the 1930s than the subway has today. The system’s productivity fell from the late 1930s to 1980, and has risen since 1980 but (as of 2010) not yet to the 1930s peak. The city is one of a handful where subway trains have conductors; maintenance productivity is very low as well.

Instead of demanding efficiency, American transit advocates tend to demand even more OPM. Federal funding only goes to capital construction, not operations – but the people who run advocacy organizations today keep calling for federal funding to operations, indifferent to the impact OPM would have on any effort to increase efficiency and make organizations leaner. A well-meaning but harmful bill to break this dam has been proposed in the Senate; it should be withdrawn as soon as possible.

The difference between nudging and planning

I am soon going to go over this in more details, but, in brief, the disconnect between funding and oversight is not a universal feature of state funding of local priorities. In all unitary states we’ve investigated, there is state funding, and in Sweden it’s normal to mix state, county, and municipal funding. In that way, the US is not unique, despite its federal system (which at any case has far more federal involvement in transportation than Canada has).

Where the US is unique is that the Washington political establishment doesn’t really view itself as doing concrete planning. It instead opts for government by nudge. A federal agency makes some metrics, knowing that local and state bodies will game them, creating a competition for who can game the other side better. Active planning is shunned – the idea that the FTA should have engineers who can help design subways for New York is unthinkable. Federal plans for high-speed rail are created by hiring an external consultant to cobble together local demands rather than the publicly-driven top-down planning necessary for rail.

The same political advocates who want more money and care little for technical details also care little for oversight. They say “regulations are needed” or “we’ll come up with standards,” but never point to anything concrete: “money for bus shelter,” “money for subway accessibility,” “money for subway automation,” etc. Instead, in this mentality the role of federal funding is to be an open tab, in which every leakage and every abnormal cost is justified because it employed inherently-moral $80,000/year tradesmen or build something that organized groups of third-generation homeowners in an expensive city want. The politics is the project.

Mixing High- and Low-Speed Trains

I stream on Twitch (almost) every week on Saturdays – the topic starting now is fare systems. Two weeks ago, I streamed about the topic of how to mix high-speed rail and regional rail together, and unfortunately there were technical problems that wrecked the recording and therefore I did not upload the video to YouTube as I usually do. Instead, I’d like to write down how to do this. The most obvious use case for such a blending is the Northeast Corridor, but there are others.

The good news is that good high-speed rail and good legacy rail are complements, rather than competing priorities. They look like competing priorities because, as a matter of national tradition of intercity rail, Japan and France are bad at low-speed rail outside the largest cities (and China is bad even in the largest cities) and Germany is bad at high-speed rail, so it looks like one or the other. But in reality, a strong high-speed rail network means that distinguished nodes with high-speed rail stations become natural points of convergence of the rail network, and those can then be set up as low-speed rail connection nodes.

Where there is more conflict is on two-track lines with demand for both regional and intercity rail. Scheduling trains of different speeds on the same pair of tracks is dicey, but still possible given commitment to integration of schedule, rolling stock, and timetable. The compromises required are smaller than the cost of fully four-tracking a line that does not need so much capacity.

Complementarity

Whenever a high-speed line runs separately from a legacy line, they are complements. This occurs on four-track lines, on lines with separate high-speed tracks running parallel to the legacy route, and at junctions where the legacy lines serve different directions or destinations. In all cases, network effects provide complementarity.

As a toy model, let’s look at Providence Station – but not at the issue of shared track on the Northeast Corridor. Providence has a rail link not just along the Northeast Corridor but also to the northwest, to Woonsocket, with light track sharing with the mainline. Providence-Woonsocket is 25 km, which is well within S-Bahn range in a larger city, but Providence is small enough that this needs to be thought of as scheduled regional rail. A Providence-Woonsocket regional link is stronger in the presence of high-speed rail, because then Woonsocket residents can commute to Boston with a change in Providence, and travel to New York in around 2 hours also with a change in Providence.

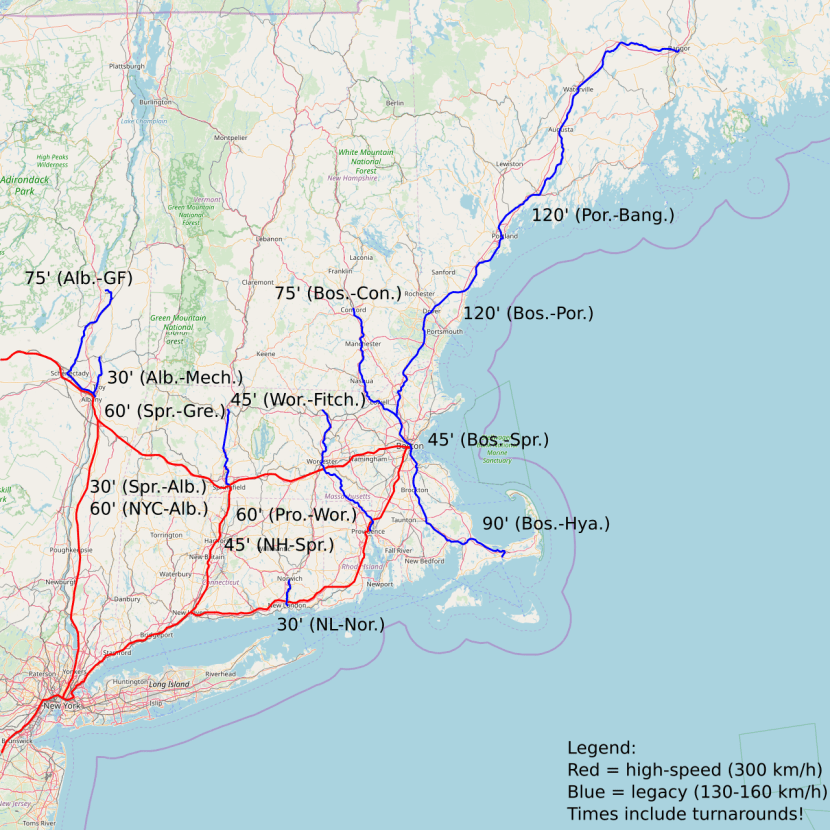

More New England examples can be found with Northeast Corridor tie-ins – see this post, with map reproduced below:

The map hides the most important complement: New Haven-Hartford-Springfield is a low-speed intercity line, and the initial implementation of high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor should leave it as such, with high-speed upgrades later. This is likely also the case for Boston-Springfield – the only reason it might be worthwhile going straight from nothing to high-speed rail is if negotiations with freight track owner CSX get too difficult or if for another reason Massachusetts can’t electrify the tracks at reasonable cost and run fast regional trains.

There’s also complementarity with lines that are parallel to the Northeast Corridor, like the current route east of New Haven, which the route depicted in the map bypasses. This route serves Southeast Connecticut communities like Old Saybrook and can efficiently ferry passengers to New Haven for onward connections.

In all of these cases, there is something special: Woonsocket-Boston is a semireasonable commute, New London connects to the Mohegan Sun casino complex, New Haven-Hartford and Boston-Springfield are strong intercity corridors by themselves, Cape Cod is a weekend getaway destination. That’s fine. Passenger rail is not a commodity – something special almost always comes up.

But in all cases, network effects mean that the intercity line makes the regional lines stronger and vice versa. The relative strength of these two effects varies; in the Northeast, the intercity line is dominant because New York is big and off-mainline destinations like Woonsocket and Mohegan are not. But the complementarity is always there. The upshot is that in an environment with a strong regional low-speed network and not much high-speed rail, like Germany, introducing high-speed rail makes the legacy network stronger; in one that is the opposite, like France, introducing a regional takt converging on a city center TGV station would likewise strengthen the network.

Competition for track space

Blending high- and low-speed rail gets more complicated if they need to use the same tracks. Sometimes, only two tracks are available for trains of mixed speeds.

In that case, there are three ways to reduce conflict:

- Shorten the mixed segment

- Speed up the slow trains

- Slow down the fast trains

Shortening the mixed segment means choosing a route that reduces conflict. Sometimes, the conflict comes pre-shortened: if many lines converge on the same city center approach, then there is a short shared segment, which introduces route planning headaches but not big ones. In other cases, there may be a choice:

- In Boston, the Franklin Line can enter city center via the Northeast Corridor (locally called Southwest Corridor) or via the Fairmount Line; the choice between the two routes is close based on purely regional considerations, but the presence of high-speed rail tilts it toward Fairmount, to clear space for intercity trains.

- In New York, there are two routes from New Rochelle to Manhattan. Most commuter trains should use the route intercity trains don’t, which is the Grand Central route; the only commuter trains running on Penn Station Access should be local ones providing service in the Bronx.

- In the Bay Area, high-speed rail can center from the south via Pacheco Pass or from the east via Altamont Pass. The point made by Clem Tillier and Richard Mlynarik is that Pacheco Pass involves 80 km of track sharing compared with only 42 km for Altamont and therefore it requires more four-tracking at higher cost.

Speeding up the slow trains means investing in speed upgrades for them. This includes electrification where it’s absent: Boston-Providence currently takes 1:10 and could take 0:47 with electrification, high platforms, and 21st-century equipment, which compares with a present-day Amtrak schedule of 0:35 without padding and 0:45 with. Today, mixing 1:10 and 0:35 requires holding trains for an overtake at Attleboro, where four tracks are already present, even though the frequency is worse than hourly. In a high-speed rail future, 0:47 and 0:22 can mix with two overtakes every 15 minutes, since the speed difference is reduced even with the increase in intercity rail speed – and I will defend the 10-year-old timetable in the link.

If overtakes are present, then it’s desirable to decrease the speed difference on shared segments but then increase it during the overtake: ideally the speed difference on an overtake is such that the fast train goes from being just behind the slow train to just ahead of it. If the overtake is a single station, this means holding the slow train. But if the overtake is a short bypass of a slow segment, this means adding stops to the slow train to slow it down even further, to facilitate the overtake.

A good example of this principle is at the New York/Connecticut border, one of the slowest segments of the Northeast Corridor today. A bypass along I-95 is desirable, even at a speed of 200-230 km/h, because the legacy line is too curvy there. This bypass should also function as an overtake between intercity trains and express commuter trains, on a line that today has four tracks and three speed classes (those two and local commuter trains). To facilitate the overtake, the slow trains (that is, the express commuter trains – the locals run on separate track throughout) should be slowed further by being made to make more stops, and thus all Metro-North trains, even the express trains, should stop at Greenwich and perhaps also Port Chester. The choice of these stops is deliberate: Greenwich is one of the busiest stops on the line, especially for reverse-commuters; Port Chester does not have as many jobs nearby but has a historic town center that could see more traffic.

Slowing down the intercity trains is also a possibility. But it should not be seen as the default, only as one of three options. Speed deterioration coming from such blending in a serious problem, and is one reason why the compromises made for California High-Speed Rail are slowing down the trip time from the originally promised 2:40 for Los Angeles-San Francisco to 3:15 according to one of the planners working on the project who spoke to me about it privately.

Modernizing Rail, and a Note on Gender

Modernizing Rail starts in 15 hours! Please register here, it’s free. The schedule can be viewed here (and the Zoom rooms all have a password that will be given to registered attendees); note that the construction costs talk is not given by me but by Elif Ensari, who for the first time is going to present the Turkish case, the second in our overall project, to the general public. But do not feel obligated to attend, not given what else it’s running against.

I made a video going into the various breakout talks that are happening, in which I devoted a lot of time to the issue of gender. This is because Grecia White didn’t have enough time at last year’s equity session to talk about it, so this time she’s getting a full session, which I have every intention of attending. The video mentions something that fizzled out because of difficulties dealing with US census UI, which is a lot harder to use than the old Factfinder: the issue of gender by commuting. So I’d like to give this more time, since I know Grecia is going to talk about something adjacent but not the same.

The crux is this: public transit ridership skews female, to some extent. US-wide, 55% of public transit trips are by women; an LA-specific report finds that there, women are 54% of bus riders and 51% of rail riders. The American Community Survey’s Means of Transportation to Work by Selected Characteristics Table has men at 53% of the overall workforce but transit commuters splitting 50-50; the difference, pointed out in both links, is that women ride more for non-work trips, often chaining trips for shopping and child care purposes rather than just commuting to work.

In the video, I tried to look at the gender skew in parts of the US where transit riders mostly use commuter rail, like Long Island, and there, the skew goes the other way, around 58-42 for men. In Westchester, it is 54-46. In New York, which I struggled to find data for in the video, the split is 52-48 female – more women than men get to work on public transit.

But an even better source is the Sex of Workers by Means of Transportation to Work table, which (unlike Selected Characteristics) details commute mode choice not just as car vs. transit but specifies which mode of public transit is taken. There are, as of the 2019 ACS, 3,898,132 male transit commuters and 3,880,312 female ones – that’s the 50-50 split above. But among commuter rail riders, the split is 533,556 men, 387,835 women, which is 58-42. Subways split about 50-50, buses skew 52-48 female.

In the video, I explain this referencing Mad Men. Commuter rail is stuck in that era, having shed all other potential riders with derogatory references to the subway; it’s for 9-to-5 suburban workers commuting to the city, and this is a lifestyle that is specifically gendered, with the man commuting to the city and the woman staying in the suburb.

This impacts advocacy as well. In planning meetings for the conference, we were looking for more diverse presenters, but ran into the problem that in the US, women and minorities abound in public transit advocacy but not really in mainline rail, which remains more white and male. I believe that this is true of the workforce as well, but the only statistics I remember are about race (New York subway and bus drivers are by a large majority nonwhite, commuter rail drivers and conductors are the opposite), and not gender. Of course there are women in the field – Adina Levin (who presented last year) and Elizabeth Alexis are two must-read names for understanding what goes on both in general and in the Bay Area in particular – but it’s unfortunately not as deep a bench as for non-mainline transit, from which it is siloed, which has too many activists to list them all.

Regional Rail and Subway Maintenance

Uday Schultz has a thorough post about New York’s subway service deterioration over the last decade, explaining it in terms of ever more generous maintenance slowdowns. He brings up track closures for renewal as a typical European practice, citing examples like Munich’s two annual weekends of S-Bahn outage and Paris’s summertime line closures. But there’s a key aspect he neglects: over here, the combination of regional rail and subway tunnels means that different trunk lines can substitute for one another. This makes long-term closures massively less painful and expensive.

S-Bahn and subway redundancy

S-Bahn or RER systems are not built to be redundant with the metro. Quite to the contrary, the aim is to provide service the metro doesn’t, whether it’s to different areas (typically farther out in the suburbs) or, in the case of the RER A in Paris, express overlay next to the local subway. The RER and Métro work as a combined urban rail network in Paris, as do the S- and U-Bahns in German cities that have both, or the Metro and Cercanías in Madrid and Barcelona.

And yet, in large urban rail systems, there’s always redundancy, more than planners think or intend. The cleanest example of this is that in Paris, the RER A is an express version of Métro Line 1: all RER A stops in the city have transfers to M1 with the exception of Auber, which isn’t too far away and has ample if annoying north-south transfers to the Champs-Elysées stations on M1. As a result, summertime closures on the RER A when I lived in the city were tolerable, because I could just take M1 and tolerate moderate slowdowns.

This is the case even in systems designed around never shutting down, like Tokyo. Japan, as Uday notes, doesn’t do unexpected closures – the Yamanote Line went decades with only the usual nighttime maintenance windows. But the Yamanote Line is highly redundant: it’s a four-track line, and it is paralleled at short distance by the Fukutoshin Line. A large city will invariably generate very thick travel markets, and those will have multiple lines, like the east-west axis of M1 and the RER A, the two north-south axes of M12 and M13 and of M4 and the RER B, the east-west spine from Berlin Hauptbahnhof east, the Ikebukuro-Shibuya corridor, or the mass of lines passing through Central Tokyo going northeast-southwest.

The issue of replacement service

In the United States, standard practice is that every time a subway line is shut for maintenance, there are replacement buses. The buses are expensive to run: they are slow and low-capacity, and often work off the overtime economy of unionized labor; their operating costs count as part of the capital costs of construction projects. Uday moreover points out that doing long-term closures in New York on the model of so many large European cities would stress the capacity of buses in terms of fleet and drivers, raising costs further.

This is where parallel rail lines come in. In some cases, these can be other subway lines: from north of Grand Central to Harlem-125th, the local 6 and express 4/5 tracks are on different levels, so the express tracks can be shut down overnight for free, and then during maintenance surges the local tracks can be shut and passengers told to ride express trains or Second Avenue Subway. On the West Side, the 1/2/3 and the A/B/C/D are close enough to substitute for each other.

But in Queens and parts of the Bronx, leveraging commuter rail is valuable. The E/F and the LIRR are close enough to substitute for each other; the Port Washington Branch can, to some extent, substitute for the 7; the Metro-North trunk plus east-west buses would beat any interrupted north-south subway and would even beat the subway in normal service to Grand Central.

Running better commuter rail

The use of commuter rail as a subway substitute, so common in this part of the world, requires New York to run service along the same paradigm that this part of the world does. Over here, the purpose of commuter rail is to run urban rail service without needing to build greenfield tunnels in the suburbs. The fares are the same, and the frequency within the city is high all day every day. It runs like the subway, grading into lower-density service the farther one goes; it exists to extend the city and its infrastructure outward into the suburbs.

This way, a coordinated urban rail system works the best. Where lines do not overlap, passengers can take whichever is closest. Where they do, as is so common in city center, disruption on one trunk is less painful because passengers can take the other. The system does not need an external infusion of special service via transportation-of-last-resort shuttle buses, and costs are easier to keep under control.

New Leadership for New York City Transit and the MTA

Andrew Cuomo resigned, effective two weeks from now, after it became clear that if he didn’t the state legislature would remove him. As much of the leadership of public transportation in the state is his political appointees, like Sarah Feinberg, the incoming state governor, Lieutenant-Governor Kathy Hochul, will need to appoint new heads in their stead. From my position of knowing more about European public transit governance than the New York political system does, I’d like to make some recommendations.

Hire from outside the US

New York’s construction costs are uniquely high, and its operating costs are on the high side as well; in construction and to a large extent also in operations, it’s a general American problem. Managers come to believe that certain things are impossible that in fact happen all the time in other countries, occasionally even in other US cities. As an example, we’ve constantly heard fire safety as an excuse for overbuilt subway stations – but Turkey piggybacks on the American fire safety codes and to a large extent so does Spain and both have made it work with smaller station footprints. Much of the problem is amenable to bringing in an outsider.

The outsider has to be a true outsider – outside the country, not just the agency. An American manager from outside transportation would come in with biases of how one performs management, which play to the groupthink of the existing senior management. Beware of managers who try to perform American pragmatism by saying they don’t care about “Paris or such,” as did the Washington Metro general manager. Consultants are also out – far too many are retirees of those agencies, reproducing the groupthink without any of the recent understanding by junior planners of what is going wrong.

Get a Byford, not Byford himself

Andy Byford is, by an overwhelming consensus in New York, a successful subway manager. Coming in from Toronto, where he was viewed as a success as well, he reformed operations in New York to reduce labor-management hostility, improve the agency’s accessibility program, and reduce the extent of slow orders. Those slow orders were put in there by overly cautious management, such as Ronnie Hakim, who came in via the legal department rather than operations, and viewed speed as a liability risk. Byford began a process called Save Safe Seconds to speed up the trains, which helped turn ridership around after small declines in ridership in the mid-2010s.

The ideal leader should be a Byford. It cannot be Byford himself: after Cuomo pushed him out for being too successful and getting too much credit, Byford returned to his native Britain, where Mayor Sadiq Khan appointed him head of Transport for London. Consulting with Byford on who to hire would be an excellent idea, but Byford has his dream job and is very unlikely to come back to New York.

Look outside the Anglosphere

High operating costs are a New York problem, and to some extent a US problem. Canada and the UK do just fine there. However, construction costs, while uniquely bad in New York, are also elevated everywhere that speaks English. The same pool of consultants travel across, spreading bad ideas from the US and UK to countries with cultural cringe toward them like Canada, Australia, and Singapore.

The MTA has a $50 billion 5-year capital plan. Paris could only dream of such money – Grand Paris Express is of similar size with the ongoing cost overruns but is a 15-year project. The ideal head of the MTA should come from a place with low or at worst medium construction costs, to supervise such a capital plan and coordinate between NYCT and the commuter rail operators.

Such a manager is not going to be a native English speaker, but that’s fine – quite a lot of the Continental European elite is fluent in English, though unfortunately this is not as true in Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan. If it is possible to entice a Spanish manager like Silvia Roldán Fernández of Madrid Metro to come in, then this is ideal, given the number of Spanish-speaking New Yorkers; Madrid of course also has legendarily low construction costs, even today. Gerardo Lertxundi Albéniz of Barcelona is a solid option. Italian managers are an option as well given the growing networks in Italy, not just building new lines but also making old stations accessible: Stefano Cetti of Milan’s public works arm MM, Gioia Ghezzi of the operating company ATM, Giovanni Mottura of Rome’s ATAC, etc. Germans like Munich’s Bernd Rosenbusch or Ingo Wortmann or Berlin’s Eva Kreienkamp have experience with juggling conflicting local and state demands and with more labor militancy than people outside Germany associate Germany with. Laurent Probst may well be a good choice with his experience coordinating an even larger transit network than New York’s – assuming that he wouldn’t view New York as a demotion; the same is true of RATP’s head, the generalist Catherine Guillouard.

This is not meant to be a shortlist – these are just the heads of the transit organs of most of the larger Continental Western European systems. Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese heads should be considered too, if they speak English and if they don’t view working in the US, in a city smaller than Tokyo or Seoul, as a demotion.

Let the civil service work

American civil service is broken – or, more precisely, was never allowed to become an administrative state, thanks to postwar anti-state paranoia. Professionals learn to be timid and wait for the word of a political appointee to do anything unusual. Cuomo did not create this situation – he merely abused it for his own personal gain, making sure the political appointees were not generic liberal Democrats but his own personal loyalists.

The future cannot be a return to the status quo that Cuomo exploited. The civil service has to be allowed to work. The role of elected politicians is to set budgets, say yes or no to megaproject proposals, give very broad directions (“hire more women,” “run like a business,” etc.), and appoint czars in extreme situations when things are at an impasse. Byford acted as if he could work independently, and Cuomo punished him for it. It’s necessary for New York to signal in advance that the Cuomo era is gone and the next Byford will be allowed to work and rewarded for success. This means, hiring someone who expects that the civil service should work, giving them political cover to engage in far-reaching reforms as required, and rewarding success with greater budgets and promotions.

Why It’s Important to Remove Failed Leaders

Andrew Cuomo has a Midas touch. Everything he touches turns to gold, that is, shiny, expensive, and useless. Bin Laden killed 3,000 people in New York on 9-11. Cuomo, through his preference for loyalists who cover up his sexual assaults over competent people, has killed 60,000 and counting in corona excess deaths – 50% more than the US-wide average. And the state let it slide, making excuses for his lying about the nursing home scandal. Eventually the sexual assault stories caught up with him, but not before every state politician preferred to extract some meaningless budget concessions instead of eliminate the killer of New Yorkers at the first opportunity. Even now they delay, not wanting to impeach; they do not believe in consequences for kings, only for subjects.

Time and time again, powerful people show that they don’t believe in accountability. After all, they might be held accountable too, one day. This cascades from the level of a mass killer of a governor down to every middle manager who excuses failure. The idea is that the appearance of scandal is worse than the underlying offense, that somehow things will get better by pretending nothing happened.

And here is the problem: bad leaders, whether they are bad due to pure incompetence or malevolence, don’t get good. People can improve at the start of their careers; leaders are who they are. They can only be thrown away, as far as down as practical, as an example. Anders Tegnell proposed herd immunity for Sweden in early 2020 and then pretended he never did, and the country remained unmasked for most of the year; deaths, while below European averages due to low Nordic levels of cohabitation, are far and away the worst in the Nordic countries, and yet Tegnell is still around, still directing an anti-mask policy. Tegnell is incompetent; Sweden is a worse country for not having gotten rid of him in late spring 2020. Cuomo is malevolent; New York is a worse state for every day that passes that he’s not facing trial for mass manslaughter and sexual assault, every day that passes that his mercenary spokespeople who attacked his victims remain employed.

This is not a moral issue. It’s a practical issue. The most powerful signal anyone can get is promotion versus dismissal (there’s also pay, but it’s not relevant to political power). When Andrew Cuomo stripped Andy Byford of responsibilities as head of New York City Transit, it was a clear signal: you can be a widely acclaimed success, but you failed to flatter the monarch and prostrate before him and this is what matters to me. Byford read the signal correctly, resigned, and ended up promoted to the head of Transport for London, because Sadiq Khan and TfL appreciate competence every bit as Cuomo does not.

Likewise, the retention of Tegnell sends a signal: keep doing what you’re doing. The same is true of Cuomo, and every other failure who is not thrown away from the public.

If anything, it’s worse for a sitting governor. Cuomo openly makes deals. The state legislators who can remove this killer from the body politic choose to negotiate, sending a clear signal: corrupt the state and be rewarded. 60,000 dead New York State residents mean little to them; many more who will die as variants come in mean even less.

The better signal is you have nothing anyone wants, go rot at Sing Sing. This is the correct way to deal with a failure even of three fewer orders of magnitude. Fortunately, there’s only one Cuomo – never before has New York had such mass man-made death. Unfortunately, incidents that are still deadly and require surgical removal of malefactors are far more common. Many come from Cuomo’s lackeys; in my field, the subway, Sarah Feinberg is responsible for around a hundred preventable transit worker deaths, and should never work in or adjacent to this field again. But apolitical managers too screw up on costs, on procurement, on maintenance, on operations, on safety – and rarely suffer for it. But then the fish rots from the head. Chop it off and move on.