Category: New York

Penn Station 3D Model

As part of our high-speed rail program at Marron, I designed and other people made a 3D model of the train station I referenced in 2015 in what was originally a trollish proposal, upgraded to something more serious. For now there’s still a password: letsredothis. This is a playable level, so have a look around.

The playable 3D model shows what Penn Station could look like if it were rebuilt from the ground up, based on best industry practices. It is deliberately minimalistic: a train station is an interface between the train and the city it serves, and therefore its primary goal is to get passengers between the street or the subway and the platform as efficiently as possible. But minimalism should not be conflated with either architectural plainness (see below on technical limitations) or poor passenger convenience. The open design means that pedestrian circulation for passengers would be dramatically improved over today’s infamously cramped passageways.

Much of the design for this station is inspired by modern European train stations, including Berlin Hauptbahnhof (opened 2006), the under-construction Stuttgart 21 (scheduled to open 2025), and the reconstruction of Utrecht Central (2013-16); Utrecht, in turn, was inspired by the design of Shinagawa in Tokyo.

As we investigate which infrastructure projects are required for a high-speed rail program in the Northeast, we will evaluate the place of this station as well. Besides intangible benefits explained below in background, there are considerable tangible benefits in faster egress from the train to the street.

Moreover, the process that led to this blueprint and model can be reused elsewhere. In particular, as we explain in the section on pedestrian circulation, elements of the platform design should be used for the construction of subway stations on some lines under consideration in New York and other American cities, to minimize both construction costs and wasted time for passengers to navigate underground corridors. In that sense, this model can be viewed not just as a proposal for Penn Station, but also as an appendix to our report on construction costs.

Background

New York Penn Station is unpopular among users, and has been since the current station opened in 1968 (“One entered the city like a God; one scuttles in now like a rat” -Vincent Scully). From time to time, proposals for rebuilding the station along a better or grander design have been floated, usually in connection with a plan for improving the track level below.

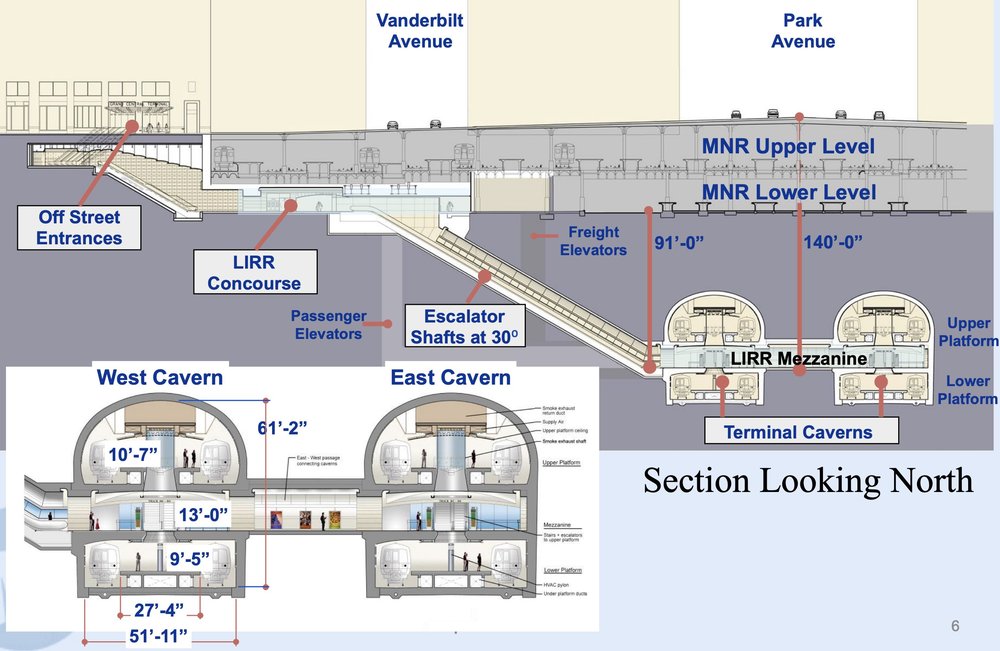

Right now, such a track-level improvement is beginning construction, in the form of the Gateway Project and its Hudson Tunnel Project (HTP). The purpose of HTP is to add two new tracks’ worth of rail capacity from New Jersey to Penn Station; currently, there are only two mainline tracks under the Hudson, the North River Tunnels (NRT), with a peak throughput of 24 trains per hour across Amtrak’s intercity trains and New Jersey Transit’s (NJT) commuter trains, and very high crowding levels on the eve of the pandemic; 24 trains per hour is usually the limit of mainline rail, with higher figures only available on more self-contained systems. In contrast, going east of Penn Station, there are four East River Tunnel (ERT) tracks to Long Island and the Northeast Corridor, with a pre-corona peak throughput of not 48 trains per hour but only about 40.

Gateway is a broader project than HTP, including additional elements on both the New Jersey and Manhattan sides. Whereas HTP has recently been funded, with a budget of $14-16 billion, the total projected cost of Gateway is $50 billion, largely unfunded, of which $20 billion comprises improvements and additions to Penn Station, most of which are completely unnecessary.

Those additions include the $7 billion Penn Reconstruction and the $13 billion Penn Expansion. Penn Reconstruction is a laundry list of improvements to the existing Penn Station, including 29 new staircases and escalators from the platforms to the concourses, additional concourse space, total reconstruction of the upper concourse to simplify the layout, and new entrances from the street to the station. It’s not a bad project, but the cost is disproportionate to the benefits. Penn Expansion would build upon it and condemn the block south of the station, the so-called Block 780, to excavate new tracks; it is a complete waste of money even before it has been funded, as scarce planner resources are spent on it.

The 3D model as depicted should be thought of as an alternative form of Penn Reconstruction, for what is likely a similar cost. It bakes in assumptions on service, as detailed below, that assume both commuter and intercity trains run efficiently and in a coordinated manner.

Station description

The station in the model is fully daylit, with no obstruction above the platforms. There are eight wide platforms and 16 tracks, down from 11 platforms and 21 tracks today. The station box is bounded by 7th Avenue, 31st Street, 8th Avenue, and 33rd Street, as today; also as today, the central platforms continue well to the west of 8th Avenue, using the existing Moynihan Train Hall. No expansion of the footprint is required. The existing track 1 (the southernmost) becomes the new track 1A and the existing track 21 becomes the new track 8B.

The removal of three platforms and five tracks and some additional track-level work combine to make the remaining platforms 11.5 meters wide each, compared with a range of 9-10 meters at some comparable high-throughput stations, such as Tokyo.

With wide platforms, the platforms themselves can be part of the station. A persistent difference between American and European train stations is that at American stations, even beloved ones like Grand Central, the station is near where the tracks are, whereas in Europe, the station is where the tracks are. Grand Central has a majestic waiting hall, but the tracks and platforms themselves are in cramped, dank areas with low ceilings and poor lighting. The 3D model, in contrast, integrated the tracks into the station structure: the model includes concessions below most escalator and stair banks, which could offer retail, fast food, or coffee. Ticketing machines can be placed throughout the complex, on the platforms as well as at places along the access corridors that are not needed for rush hour pedestrian circulation. This, more than anything, explains the minimalistic design, with no concourses: concourses are not required when there is direct access between the street and the platforms.

For circulation, there are two walkways, labeled East and West Walkways; these may be thought of as 7⅓th and 7⅔th Avenues, respectively. West End Corridor is kept, as is the circulation space under 33rd Street connecting West End Corridor and points east, currently part of the station concourse. A new north-south corridor called East End Corridor appears between the station and 7th Avenue, with access to the 1/2/3 trains.

What about Madison Square Garden?

Currently, Penn Station is effectively in the basement of Madison Square Garden (MSG) and Two Penn Plaza. Both buildings need to come down to build this vision.

MSG has come under attack recently for competing for space with the train station; going back to the early 2010s, plans for rebuilding Penn Station to have direct sunlight have assumed that MSG should move somewhere else, and this month, City Council voted to extend MSG’s permit by only five years and not the expected 10, in effect creating a five-year clock for a plan to daylight Penn Station. There have been recent plans to move MSG, such as the Vishaan Chakrabarti vision for Penn Station; the 3D model could be viewed as the rail engineering answer to that architecture-centric vision.

Two Penn Plaza is a 150,000 m^2 skyscraper, in a city where developers can build a replacement for $900 million in 2018 prices.

The complete removal of both buildings makes work on Penn Station vastly simpler. The station is replete with columns, obstructing sight lines, taking up space between tracks, and constraining all changes. The 3D model’s blueprint takes care to respect column placement west of 8th Avenue, where the columns are sparser and it’s possible to design tracks around them, but it is not possible to do so between 7th and 8th Avenues. Conversely, with the columns removed, it is not hard to daylight the station.

Station operations

The operating model at this station is based on consistency and simplicity. Every train has a consistent platform to use. Thus, passengers would be able to know their track number months in advance, just as in Japan and much of Europe, train reservations already include the track number at the station. The scramble passengers face at Penn Station today, waiting to see their train’s track number posted minutes in advance and then rushing to the platform, would be eliminated.

Each approach track thus splits into two tracks flanking the same platform. This is the same design used at Stuttgart 21 and Berlin Hauptbahnhof: if a last-minute change in track assignment is needed, it can be guaranteed to face the same platform, limiting passenger confusion. At each platform, numbered south to north as today, the A track is to the south of the B track, but the trains on the two tracks would be serving the same line and coming from and going to the same approach track. This way, a train can enter the A track at a station while the previous train is still departing the B track, which provides higher capacity.

The labels on the signage are by destination:

- Platform 1: eastbound trains from the HTP, eventually going to a through-tunnel to Grand Central

- Platform 2: westbound trains to the HTP, connecting from Grand Central

- Platform 3: eastbound trains from the preexisting North River Tunnels (NRT) to the existing East River Tunnels (ERT) under 32nd Street

- Platform 4: eastbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 5: westbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 6: westbound trains from the ERT under 32nd Street to the NRT

- Platform 7: eastbound trains to the ERT under 33rd Street and the LIRR, eventually connecting to a through-tunnel from the Hudson Line

- Platform 8: westbound trains from LIRR via the ERT under 33rd Street, eventually going to a through-tunnel to the Hudson Line

Signage labels except for the intercity platforms 4 and 5 state the name of the commuter railway that the trains would go to. Thus, a train from Trenton to Stamford running via the Northeast Corridor and the under-construction Penn Station Access line would use platform 3, and is labeled as Metro-North, as it goes toward Metro-North territory; the same train going back, using platform 6, is labeled as New Jersey Transit, as it goes toward New Jersey.

Such through-running is obligatory for efficient station operations. There are many good reasons to run through, which are described in detail in a forthcoming document by the Effective Transit Alliance. But for one point about efficiency, it takes a train a minimum of 10 minutes to turn at a train station and change direction in the United States, and this is after much optimization (Penn Station’s current users believe they need 18-22 minutes to turn). In contrast, a through-train can unload at even an extremely busy station like Penn in not much more than a minute; the narrow platforms of today’s station could clear a full rush hour train in emergency conditions today in about 3-4 minutes, and the wide platforms of the 3D model could do so in about 1.5 minutes in emergencies and less in regular operations.

Supporting infrastructure assumptions

The assumption for the model is that the HTP is a done deal; it was recently federally funded, in a way that is said to be difficult to repeal in the future in the event of a change in government. The HTP tunnel is slated to open in 2035; the current timetable is that full operations can only begin in 2038 after a three-year closure of NRT infrastructure for long-term repairs, but in fact those repairs can be done in weekend windows—indeed, present-day rail timetables through the NRT assume that one track is out for a 55-hour period each weekend, but investigative reporting has shown that Amtrak takes advantage of this outage only once every three months. If repairs are done every weekend, then it will be possible to refurbish the tunnels by 2035, for full four-track operations in 12 years.

The HTP approach to Penn Station assumes that trains from the tunnel would veer south, eventually to tracks to be excavated out of Block 780 for $13 billion. However, nothing in the current design of the tunnel forces tracks to veer so far south to Penn Expansion. There is room, respecting the support columns west of 8th Avenue, to connect the HTP approach to the new platforms 1 and 2, or for that matter to present-day tracks 1-5.

It is also assumed that Penn Station Access (PSA) is completed; the project’s current timeline is that it will open in 2026, offering Metro-North service from the New Haven Line to Penn Station. As soon as PSA opens, trains should run through to New Jersey, for the higher efficiency mentioned above.

The additional pieces of major infrastructure required for this vision are a tunnel from Penn Station to Grand Central, and an Empire Connection realignment.

The Penn Station-Grand Central connection (from platforms 1 and 2) has been discussed for at least 20 years, but not acted upon, since it would force coordination between New Jersey Transit and Metro-North. Such a connection would offer riders at both systems the choice between either Manhattan station—and the choice would be on the same train, whereas on the LIRR, the same choice offered by East Side Access cuts the frequency to each terminal in half, which has angered Long Island commuters.

Overall, it would be a tunnel of about 2 km without stations. It would require some mining under the corner of Penn 11, the building east of 7th Avenue between 31st and 32nd Street, but only to the same extent that was already done in the 1900s to build the ERT under 32nd Street. Subsequently, the tunnel would nimbly weave between older tunnels, using an aggressive 4% grade with modern electric trainsets (the subway even climbs 5.4% out of a station at Manhattan Bridge, whereas this would descend 4% from a station). The cost should be on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions—the billions of dollars in per-km cost in New York today are driven by station construction rather than tunnels, and by poor project delivery methods that can be changed to better ones.

The Empire Connection realignment is a shorter tunnel, but in a more constrained environment. Today, Amtrak trains connect between Penn Station and Upstate New York via the existing connection, going in tunnel under Riverside Park until it joins the tracks of the current Hudson Line in Spuyten Duyvil. Plans for electrifying the connection and using it for commuter rail exist but are not yet funded; these should be reactivated, since otherwise there’s nowhere for trains from the 33rd Street ERT to run through to the west.

It is necessary to realign the last few hundred meters of the Empire Connection. The current alignment is single-track and connects to more southerly parts of the station, rather than to the optimal location at the northern end. This is a short tunnel (perhaps 500 meters) without stations, but the need to go under an active railyard complicates construction. That said, this too should cost on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions.

Finally, platforms 3-6 all feed the same approach tracks on both sides, but in principle they could be separated into two. There are occasional long-term high-cost plans to fully separate out intercity rail tracks from commuter tracks even in New York, with dedicated tunnels all the way. The model does not assume that such plans are actualized, but if they are, then there is room to connect the new high-speed rail approach tunnel to platforms 4 and 5 at both ends.

Overall, the model gives the station just 20 turnouts, down from hundreds today. This is a more radical version of the redesign of Utrecht Station in the 2010s, which removed pass-through tracks, simplified the design, and reduced the number of turnouts from 200 to 70, in order to make the system more reliable; turnouts are failure-prone, and should be installed only when needed based on current or anticipated train movements.

Pedestrian circulation

The station in the model has very high pedestrian throughput. The maximum capacities are 100 passengers/minute on a wide escalator, 49 per minute per meter of staircase width, and 82 per minute per meter of walkway width. A full 12-car commuter train has about 1,800 passengers; the vertical access points—a minimum of seven up escalators, five 2.7 meter wide staircases, and three elevators per platform—can clear these in about 80 seconds. In the imperfect conditions of rush hour service or emergency evacuation, this is doable in about 90 seconds. A 16-car intercity train has fewer passengers, since all passengers are required to have a seat, and thus they can evacuate even faster in emergency conditions.

Not only is the throughput high but also the latency is low. At the current Penn Station, it can take six minutes just to get between a vertical access point and an exit, if the passenger gets off at the wrong part of the platform. In contrast, with the modeled station, the wide platforms make it easier for passengers to choose the right exit, and connect to a street corner or subway entrance within a maximum of about three minutes for able-bodied adults.

This has implications for station design more generally. At the Transit Costs Project, we have repeatedly heard from American interviewees that subway stations have to have full-length mezzanines for the purposes of fire evacuation, based on NFPA 130. In fact, NFPA 130 requires evacuation in four minutes of throughput, and in six minutes when starting from the most remote point on the platform; at a train station where trains are expected to run every 2-2.5 minutes at rush hour and unload most of their passengers in regular service, it is dead letter.

Thus, elements of the platform design can be copied and pasted into subway expansion programs with little change. A subway station could have vertical circulation at both ends of the platform as portrayed at any of the combined staircase and escalator banks, with wider staircases if there’s no need for passengers to walk around them. No mezzanine is required, nor complex passageways: any train up to the size of the largest New York City Subway trains could satisfy the four-minute rule with a 10-meter island platform (albeit barely for 10-car lettered lines).

Technical limitations and architecture

The model is designed around interactivity and playability. This has forced us to make some artistic compromises, compared with what one sees in 3D architectural renderings that are not interactive. To run on an average home machine, the design has had to reduce its polygon count and limit the detail of renderings that are far from the camera position.

For the same reason, the level shows the exterior of Moynihan Station as an anchor, but not the other buildings across from the station at 31st Street, 33rd Street, or 7th Avenue.

In reality, both East and West Walkways would be more architecturally notable than as they are depicted in the level. Our depiction was inspired by walkways above convention centers and airport terminals, but in reality, if this vision is built, then the walkways should be able to support themselves without relying too much on the tracks. Designs with massive columns flanking each elevator are possible, but so are designs with arches, through-arches, or tied arches, the latter two options avoiding all structural dependence on the track level.

Some more architectural elements could be included in an actual design based on this model, which could not be easily modeled in an interactive environment. The platforms certainly must have shelter from the elements, which could be simple roofs over the uncovered parts of the platform, or large glass panels spanning from 31st to 33rd Street, or even a glass dome large enough to enclose the walkways.

Finally, some extra features could be added. For example, there could be more vertical circulation between 7th Avenue and East End Corridor (which is largely a subway access corridor) than just two elevators—there could be stairs and escalators as well. There is also a lot of dead space as the tracks taper from the main of the station to the access tunnels, which could be used for back office space, ticket offices, additional concessions, or even some east-west walkways functioning as 31.5th and 32.5th Streets.

Don’t Romanticize Traditional Cities that Never Existed

(I’m aware that I’ve been posting more slowly than usual; you’ll be rewarded with train stations soon.)

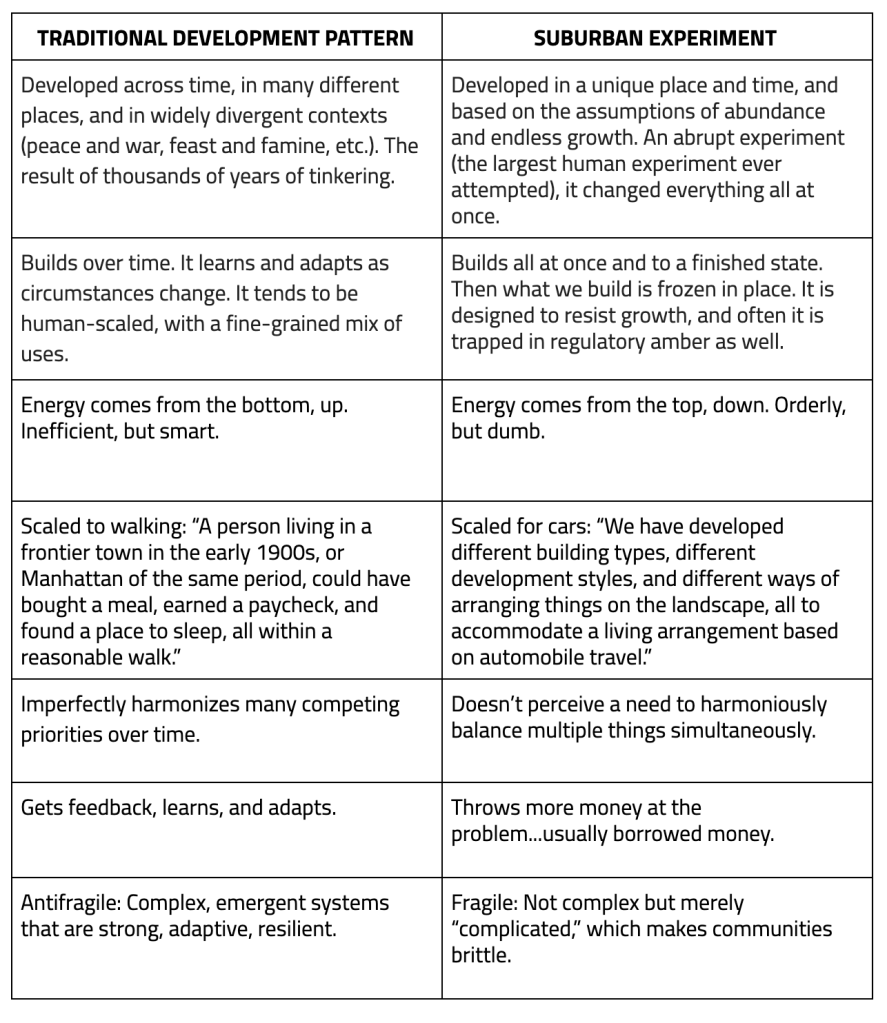

I saw a tweet by Strong Towns that compared traditional cities with the suburbs, and the wrongness of everything there reminded me of how much urbanists lie to themselves about what cities were like before cars. Strong Towns is more on the traditional urbanism side (to the point of rejecting urban rail on the grounds that it leads to non-gradual development), but a lot of what I’m critiquing here is, regrettably, commonly believed across the urbanist spectrum.

The basic problem with this comparison is that there was never such a thing as traditional urbanism. There are others; all of the claims in the comparison are false – for example, the line about “makes communities brittle” misses how little community empowerment cities had in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before zoning, and the line about top-down versus bottom-up energy misses how centralized coal and hydroelectric plants were at the turn of the century whereas left-voting NIMBY suburbs today are the most reliable place to find decentralized rooftop solar plants. But the fundamental problem is that Strong Town, and most urbanists, assume that there was a relatively fixed urban model around walkability, which cars came in and wrecked in the 20th century.

What’s true is that before mass motorization, people didn’t use cars to get around. But beyond that tautology, every principle of urban walkability was being violated in one pre-automobile urban typology or another.

Local commuting

Pre-automobile industrial cities were not 15-minute cities by any means. Marchetti’s constant of commuting goes back to at least the early 19th century; people in pre-automobile New York or London or Berlin commuted to a commercializing city center. This was to some extent understood in the second half of the 19th century: the purpose of rapid transit in New York, first steam els and then the subway, was to provide a fast enough commute so that the working class of the Lower East Side would get out of its tenements and into lower-density houses where they’d be turned from hyphenated Jews and Italians into proper Americans.

There has been a real change in that, in Gilded Age New York (and, I believe, in third-world cities today like Nairobi), people worked either locally or in city center. There was very little crosstown commuting, and so the Commissioners’ Plan for Manhattan in 1811 emphasized north-south commuting to Lower Manhattan, while private streetcar concessionaires likewise built routes to city center and rarely crosstown. Nor was there much long-distance travel except by the people who did work in city center: there were people who lived their entire lives in Brooklyn without visiting Manhattan, which became unthinkable by the early 20th century already. But this hardly makes Gilded Age Brooklyn a 15-minute city, any more than a modern suburb where most people do not visit city center out of fears of crime is anything but a suburb of the city, living off of the income generated by people who do commute in.

In truly premodern city, the situation depended on the time and place. Medieval European cities famously had little commuting – shopkeepers would live in the same building that housed their store, sleeping on an upper floor. But in Tang-era Chang’an, people did commute (my reference is the History of Imperial China series, no link, sorry). This is very far from the result of thousands of years of tinkering, when each time and place did something different before industrialization, and then went to yet another set of layouts after.

Local infrastructure

Pre-automobile industrial cities mixed top-down and bottom-up approaches, same as today. The grid plans favored in the United States, China, and the Roman Empire were more top-down than the unplanned street networks of most medieval and Early Modern European cities, each designed for a different cultural context. (In Imperial Rome much of the context was about following military manuals, for those cities that descend from forts.) In the medieval Muslim world, cities had cul-de-sacs long before cars, because this way each clan could have its own walled garden, so to speak.

Widely divergent contexts

Premodern cities developed in widely divergent contexts. Based on these contexts, they could look radically different. The comparison mentions war and peace; well, defensive walls were a fixture in many cities, and these mattered for their urban development. They were not nice strolls the way some embankments are today. There aren’t any good examples of walls in North America, but there are star forts, and they’re not usually pleasant walks – their purpose was to make the day of besieging troops as bad as possible, not to make tourists feel good about the city’s history. Medieval walls were completely different from star forts, and didn’t make for a walkable environment, either – in Paris I would routinely walk to the park and to the exterior of the Château de Vincennes, and while the park was pleasant, the castle has a moat and none of the street uses that activate a street, like retail or windows. The modern equivalents of such fixtures should be compared with prisons and modern military bases (some using the historic star forts), not touristy palaces.

Even the concept of city center is, as mentioned above on commuting, neither timeless (it didn’t exist in premodern Europe) nor a product of cars (it did exist in 19th-century America and Europe). Joel Garreau points out, either in Edge City or in some of the articles he’s written about the concept, that the traditional downtown was really only a fixture for a few generations, from the early 19th century to the middle of the 20th.

The issue of fragility

The entire comparison is grating, but smoehow the thing that bothers me most there is not the elementary errors, but the last point, about how traditional cities were antifragile for millennia before modern suburbia came in and wrecked them with debt.

This, to be very clear, is bullshit. Premodern cities could depopulate with one plague, famine, or war; these often co-occurred, such as when Louis XIV’s wars led to such food shortages that 10% of France’s population died in two famines spaced 15 years apart (put another way: France underwent a Reign of Terror’s worth of deaths every two weeks for a year and a half, and then a second for somewhat less than a year). In 1793, 10% of Philadelphia’s population died of yellow fever within the span of a few months. After repeated sacks and economic decline, Jaffa was abandoned in much of the Early Modern era.

Industrial cities generally do not undergo any of these things. (They can be subjected to genocide, like the Jews of Europe in the Holocaust, but that’s not at all about urbanism.) But that’s hardly a millennia-old tradition when it only goes back to about the middle of the 19th century, after the Great Hunger. In the UK, the Great Hunger affected rural areas like Ireland and Highland Scotland, but in a country that was at the time majority-rural – Britain would only flip to an urban majority in 1851 – it’s hardly a defense. Nor did the era after 1850 feature much stability in the cities; boom-and-bust cycles were common and the risk of unemployment and poverty was constant.

Connecticut Pays Double for Substandard Trains

Alstom and Connecticut recently announced an order for 60 unpowered coaches, to cost $315 million. The cost – $5.25 million per 25 meter long car – is about twice as high as the norm for powered cars (electric multiple units, or EMUs), and close to the cost of an electric locomotive in Europe. It goes without saying that top officials at the Connecticut Departmemarknt of Transportation (CTDOT) need to lose their jobs over this.

The frustrating thing is that unlike the construction costs of physical infrastructure, the acquisition costs of rolling stock were not traditionally at a premium in the United States. Metro-North’s EMUs, the M8s, were acquired in 2006 for $760.3 million covering 300 cars (see PDF-p. 16); a subsequent order in 2013 for the LIRR and Metro-North was $1.83 billion for 676 cars. But then over the 2010s, the MTA’s commuter railways lost their ability to procure rolling stock at such cost. The $5.25 million/car cost is not even an artifact of recent inflation – the cost explosion was visible already on the eve of corona.

It appears that some of the trains are on their way to the fully wired Penn Station Access project, expanding Metro-North service to Penn Station via the line currently used only by Amtrak (today, Metro-North only serves Grand Central). The excuse I’ve heard is that it’s happening too fast for Metro-North or CTDOT to order proper EMUs. In reality, Penn Station Access has been under construction and previously under design for many years, and the regular replacement of the rolling stock on the other lines is also known well in advance.

Nor are these unpowered coaches some kind of fast off-the-shelf order. If they were, they wouldn’t cost like an electric locomotive. The Trains.com article says,

The 85-foot stainless steel cars, designed for at least a 40-year service life, will be based on Alstom’s X’Trapolis European EMU railcar, designed to meet Federal Railroad Administration requirements and tailored to meet Connecticut Department of Transportation needs.

In other words, Alstom took an existing EMU, gutted it to make it an unpowered coach, and then added extra weight on it for buff strength, to satisfy regulations that have already been superseded: the FRA rolling stock regulations were aligned with European norms in 2018, in dialog with the European vendors, and yet not a single one of the American commuter rail operators has seen fit to make use of the new regulations, instead insisting on buying substandard trains that no other market has any use for.

Ideally, this order should be stopped, even if CTDOT needs to pay a penalty – perhaps laying off top management would partly defray that penalty. The options should not be exercised. All future procurement should be done by people with experience buying trains that cost $100,000 per meter of length, not $210,000. If this is not done, then no public money should be given to such operations.

Rolling stock costs, Europe version

Meanwhile, in Europe, inflation hasn’t made trains cost $210,000 per meter of length. In the 2010s, nominal costs were actually decreasing for Swiss FLIRTs. Costs seem to have risen somewhat in the last few years, but overall, the cost inflation looks lower than the general inflation rate – manufacturing is getting more efficient, so the costs are falling, just as the costs of televisions and computers are falling.

Even with recent inflation, Alstom’s Coradia Stream order for RENFE cost 8.95 million € per train. I can’t find the train length – the press release only says six cars of which two are bilevel. An earlier press release says that this is 100 meters long in total, but I don’t believe this number – the bilevel Streams in Luxembourg are 27 meters long per car (and cost 2.53 million €/car; Wikipedia says the 34 trains break down as 22 short, 12 long), and other Streams tend to be longer per car as well. Bear in mind that even at 100 meters, it’s barely more than $100,000/m for a train that’s partly bilevel.

Other Coradia Stream orders have a similar or slightly higher cost. An order for 100 trains for DSB, all single-level, is 14 million €/train, including 15 years of full maintenance; Wikipedia says that these are 109 meter long. An order for 17 trains totaling 72 27-meter cars for the Rhine-Main region cost 218.2 million €. A three four-car, 84-meter train order for Abruzzo costs 19 million €.

To be fair, some orders look more expensive. For new regional operations through the soon to open Stuttgart 21 station, Baden-Württemberg has ordered 130 106-meter Streams, mixed single- and double-deck, for 2.5 billion €; I think this is the right comparison, but the cost may also include an option for 100 trains, which makes it clearer why this costs double what the rest of Europe pays. Baden-Württemberg’s Mireo order costs 300 million € for 28 three-car, 70 meter long EMUs – less than the Streams, more than the norm elsewhere in Europe for single-deck EMUs.

But what we don’t have in Europe is unpowered single-level coaches at $210,000/meter. That is ridiculous. Orders would be canceled and retendered at this cost, and the media would question the agencies and governments that approved such a waste.

It’s only Americans who have no standards at all for their government. Because they have no standards, they are okay with being led by people who cost the public several million dollars per day that they choose to wake up and go to work, like MTA head Janno Lieber or his predecessor Pat Foye, or many others at that level. Because those leaders are extraordinarily incompetent, they have not fixed what their respective agencies were bad at (physical infrastructure construction) but have presided over the destruction of what they used to be good at and no longer are (rolling stock procurement). The result is worse trains than any self-respecting first-world city gets for its commuter rail system, at a cost that is literally the highest in the world.

Quick Note: Andy Byford and Through-Running

At an event run by ReThinkNYC, Andy Byford spoke for five minutes in support of through-running at Penn Station. They put out the press release, so I feel it’s fine to reprint it in full here with some comments.

The timing works well for what I’m involved in. The Transportation and Land Use program at Marron is about to release a playable 3D model of a reimagined Penn Station designed around through-running and around maximally efficient passenger egress, with above-ground structures like Madison Square Garden removed; I was hoping for the model to come out in June in time for the debate about whether to extend the Garden’s operating permit, but that debate seems to be going the right way regardless, and the Garden itself is open to moving, for a price. Then, the Effective Transit Alliance is about to release a long report explaining the issue of through-running, why it’s good for New York, and how to implement it.

The bulk of what we’re about to do on this side of the TLU program for the next year is figure out timetable coordination for regional and intercity rail, so showing how everything would fit together should take some time, but the question of feasibility has already been answered; the work is about how to optimize questions like “where do high-speed bypasses go?” or “which curves is it worthwhile to fix?” or “which junctions should be grade-separated?”.

First of all I am honored to be in a conversation with people that I regard as absolutely luminaries in the transit space, people like Prof. [Robert] Paaswell, people like Dr. [Vukan] Vuchic. These are luminaries to me in the field of, not only transport planning, but in the particular area we’re talking about today, namely through-running.

I was very encouraged to hear Assemblymember [Tony] Simone talk about the benefit of avoiding demolishing a beautiful part of New York City, which although I live in D.C. now, is a city that is so dear to my heart. I feel I’m an adopted New Yorker, I love that place and it would break my heart to see beautiful buildings torn down on Eighth and Seventh Aves. when they don’t need to be.

I should say at the get-go, that I’m not speaking on behalf of Amtrak. I’m speaking as a railway professional. I’ve worked in transit now for 34 years. But I just feel this is a golden opportunity — and the assembly member mentioned that — and one of the other speakers also mentioned the benefits of through-running and made reference to what happened in London. London learned that lesson. There are two effectively two cross London railroads.

There’s the Elizabeth Line, which I had the pleasure of opening with Her Majesty the Queen back in 2022, and that’s has been transformative in that where people used to have to jump on the Central Line, had to get off at Paddington and then go down to the Central Line and or down to Lancaster Gate and go through Central London to go to East London to Liverpool St. and then go out the other side, now they don’t have to.

The Central Line has been immediately relieved of pressure and you’ve got a state of the art, very high speed actually, through-service state of the art railway, under the wires. Beautiful stations, air conditioned, which at a stroke has been a game changer for London, connecting not only the key parts of Central London, but also Heathrow Airport, Paddington, Liverpool St., Canary Wharf and the City of London. It is a game changer. People in Frankfurt, people in Amsterdam, people in Paris and dare I say, New York, are probably gnashing their teeth because that was a game changer for London.

Well, I live in the States now, I’m going to be an American hopefully in a few years time and I want to do my bit for the States. So it seems to me that this is a golden opportunity for the U.S. and for New York City to have something similar to the Elizabeth Line, to have something that has that economic regenerative impact in New York.

And the other corridor of course, was Thameslink, that preceded Crossrail, but that’s the north/south corridor. There again, once upon a time you used to rock up in South London and have to get on the Tube you’ll be getting on the Vic Line or you’re getting on the Northern and have to go up to Euston or Kings Cross to go north.

Now, you don’t have to do that and what London has seen is the benefit of that cross-London traffic and that through-running because you’ve got not only the economic benefits of the City but the knock-on effect of north, south, east and west of businesses popping up, of housing being developed and of relief to the existing transport lines.

So I don’t know how this is going to pan out, but what I would say, Sam [Turvey]: is good for you for at least calling the question. This is a golden opportunity. It’s not just about building something that’s more aesthetically pleasing — important as though that is, Penn Station is kind of an embarrassment — but you can’t fix it by just putting in a few light boxes, by just heightening the ceilings, by just widening a few corridors.

If we’re going to do all of that, why not take the opportunity to fix the damn thing once and for all, which is, I’m going to say: get rid of the pillars, which means move MSG, but at the very least, do something with the track configuration to enable through-running.

So that’s it, that’s my pitch. I do stress that’s my personal opinion. I’m not speaking on behalf of Amtrak. I don’t know all the facts. If it was the case that someone asked me to have a look at this, I’ll be honored to do that, but I’m just speaking as a private person who cares about New York City, who cares about the States and who’s seen what good looks like along with people far smarter than me like Prof. Paaswell and Dr. Vuchic. So thank you so much.

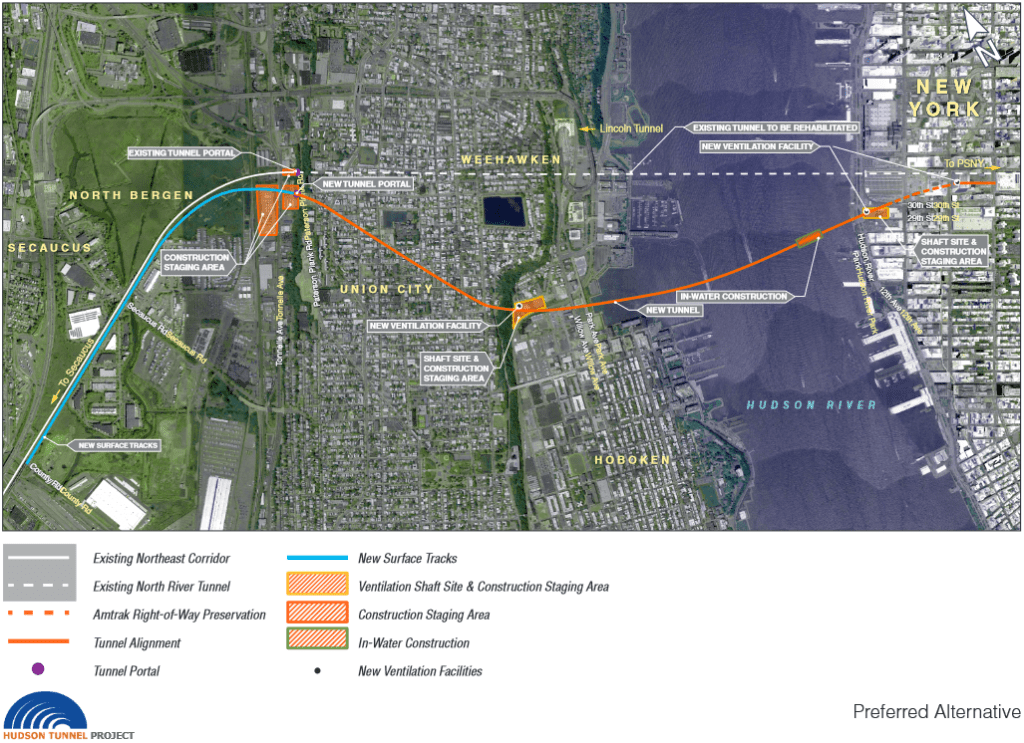

The Hudson Tunnel Project is Funded!

Two days ago, the federal government announced that it was funding the Hudson Tunnel Project, adding two new tunneled tracks between New Jersey and New York Penn Station. The total grant is $6.88 billion, representing slightly less than half of the projected cost, which is officially still $16 billion in year-of-expenditure dollars but may rise to $17 billion; nearly all of the rest of the budget is already matched in state grants from New York and New Jersey, and so for all intents and purposes, the project should be considered fully funded. Frustratingly, it’s an extremely expensive project, and yet its benefits are high that it may still pass a benefit-cost analysis – and the more operational improvements there are down the line, the higher the benefits.

The grant only covers the bare tunnels and a $2 billion project to do long-term repairs to the existing tunnels after damage suffered in Hurricane Sandy. The $14 billion new tunnels are the centerpiece of the wider $40 billion Gateway Program, which includes other items that are said to be necessary for an increase in capacity. But most of those items by cost are duds, such as the completely useless $7 billion Penn Station Expansion program to condemn an entire city block to add tracks, or the useful but not at this price $6 billion Penn Station Reconstruction program to improve pedestrian circulation at the existing station. There still remain necessary improvements on the surface to go along the Hudson Tunnel Project, but they are small – a junction fix here, some double-tracking of a single-track branch there, some high-platform projects to improve reliability yonder.

The reporting on the project says that it will be overseen by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), not the mainline-specific Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). It looks like this is coming from the general bucket of money for mass transit in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, rather than from the $30 billion dedicated to the Northeast Corridor; thus, the budget for other Northeast Corridor improvements should remain $30 billion, rather than $23.12 billion.

The issue of costs

The Hudson Tunnel Project is about five kilometers in length, from the portal on the western slope of the Palisades to the existing Penn Station:

The alignment, as can be seen in the picture, is not closely parallel to the existing tunnels. On the Manhattan side, the alignment is fixed in place, due to the construction of the Hudson Yards project since the project was first mooted in the early 2000s, when it was called Access to the Region’s Core (ARC); the only available alignment between building foundations is as depicted. Under the Hudson and in New Jersey, there are no such constraints.

What is far more suspicious is that 5 km of double-track tunnel, even partly underwater, even partly in Manhattan between skyscraper foundations, are said to cost $14 billion in total. This is not just the usual problem of high New York costs. Second Avenue Subway’s hard costs were 77% stations and station finishes and only 23% tunnels and systems; excluding the stations, and pro-rating the soft costs, the costs in 2022 dollars were only about $500 million per km. There is an underwater premium, but it doesn’t turn $500 million per km into nearly $3 billion per km, nor is the expected inflation rate over the project’s 2023-35 lifetime high enough to make a difference.

What’s more, the underwater premium is highest where the costs are already the lowest. The New York cost premium for civil infrastructure is rather small, only about a factor of around 3 over comparable European projects. Systems and finishes have a considerably higher premium, due to lack of standardization; stations have an even higher premium, due to overbuilding (the Second Avenue Subway stations were 2-3 times as big as necessary, and the two smaller ones were also deep-mined at an additional cost). The installation of systems like electrification and cables should not cost more underwater than underground – the construction of the tunnel and its lining is where the premium is. Whatever we think the underwater construction premium is – a factor of 2 is consistent with some Stockholm numbers and also with the original BART construction in the 1960s and early 70s – it should be lower in New York.

Some of it must come from ever worse project management and soft costs. The destruction of state capacity in the English-speaking world, and increasingly in nonnative English-speaking countries influenced by the UK like the Netherlands, is not a completed process; it is still ongoing. Soft costs keep rising, and the response to every failure is to add yet another layer of consultants or another layer of review. Second Avenue Subway phase 2 manages slightly higher per-km costs than phase 1, despite having less overbuilding, and from my encounters with the people in charge of capital construction at the MTA, it’s not hard to see why.

And yet, even relative to the highest costs of phase 2, Gateway is overpriced. The level of experience the people running this project have with capital construction at this scale is less than that of the MTA, and this should matter. And yet, even that doesn’t explain the large jump in costs.

Is it possible to do better?

Well, once the almost $16 billion for the project is there, it will be spent. The main reason one might oppose overpriced projects like Second Avenue Subway phase 2 even if their benefit-cost ratio is okay (which, for both phase 2 and the Hudson Tunnel Project, is iffy, though not obviously bad), is that pressure to reduce costs before approval can result in efficiencies. But once a budget is approved, nobody will make a serious effort to go significantly below it.

That said, the only smoking gun I have for how to make this project cheaper pertains to the $2 billion for fixing the existing tunnels. Currently, the timetables for both Amtrak and New Jersey Transit trains across the tunnels are written so that on weekends, only one of the two single-track tubes is in operation. Thus, maintenance work can be done on the other tunnel for an uninterrupted 55-hour period. However, Amtrak rarely takes advantage of this. In fact, reporting in the New York Daily News has found that over the last few years, only about once every three months – 13 times in a four-year period from mid-2017 to mid-2021 – has there been a full weekend repair job in one of the tunnels. Accelerated repairs would be able to reduce the costs of the fixes through greater efficiency, and, since American government budgeting is done in nominal dollars, a lower price level than in the mid-2030s.

It’s likely that such egregious examples also exist for the main project, the $14 billion new tunnels. I don’t know of any such example, and I don’t think it’s worthwhile stopping the project over this; but it’s important to remain vigilant and remember that while the tunnels are fully funded for all intents and purposes, a small gap remains and should be fillable without new money.

The benefits of the tunnels

The costs are very high. But what are the benefits?

In isolation, the benefits are that capacity across the Hudson would double. This would enable doubling commuter rail traffic. Before corona, the trains were very crowded, to the point of suppressing demand; ridership is lower now than it was then, but east of the Hudson, Metro-North is at 78% of pre-corona ridership and rising fast. Moreover, the prospects of future growth in commuting in New Jersey are better than those in suburban New York and Connecticut, since New Jersey permits housing at an almost healthy rate, 4 annual housing units per 1,000 people, whereas Long Island permits about 1, Westchester 2-3, and Fairfield County 1.5-2.5. There’s enough pressure in New Jersey even in the short term that a ridership flop like that of East Side Access is very unlikely.

That said, New Jersey Transit only had about 310,000 weekday riders in 2019, double-counting transfers (of which there aren’t many, unlike on the LIRR). Not many more than half those trips even originated or ended at Penn Station – one of the adaptations to overcrowding on New Jersey Transit is to send about half the trains from the Morris and Essex Lines to Hoboken, from which passengers take PATH into the city, and another is for passengers to get off at Newark and transfer to PATH there. Penn Station’s ridership in 2019 was 94,000 boardings, or 188,000 trips; that is the number that could potentially be doubled. So, $14 billion for 188,000 trips; this is $74,000 per rider, which is too high, and if that is the only benefit, then the project should be canceled.

However, the Hudson Tunnel Project interacts positively with every operational improvement in commuter rail. If off-peak frequencies are increased so that passengers can use the trains not just for rush hour commuting, then ridership will rise. Of course, peak frequency is not really relevant to off-peak ridership – but there are advantages from the new tunnels to off-peak service, such as more cleanly separating Northeast Corridor service from Morris and Essex service, improving reliability for both.

And then there are all the necessary small improvements, such as electrification. For example, right now, the Raritan Valley Line today is unelectrified, and passengers have to transfer at Newark to either PATH or a Northeast Corridor or North Jersey Coast Line train to Manhattan; only a handful of trains run to Manhattan using dual-mode locomotives, none at rush hour. The current service plan with the new tunnels is to run ever more trains with dual-mode locomotives, which are exceptionally expensive, heavy, and unreliable. However, the new tunnels interact positively with electrifying the Raritan Valley Line, currently the busiest diesel line in New Jersey, and with wiring short unelectrified tails on the North Jersey Coast and Morris and Essex Lines. These would raise both peak and off-peak ridership – and the extra capacity provided by the new tunnels improves the business case for them, even if the business case is healthy even purely on off-peak travel.

The same is true of platforms. The low platforms at most stations impede efficient boardings. They take too long at rush hour, and they’re inaccessible unless a conductor manually operates a wheelchair lift; conductors are not really cost-effective on commuter trains even at the wages of the 2020s, let alone those of the future. As with electrification, the case for converting all stations to high platforms for level boarding is strong even on off-peak ridership; the benefits are high and the costs are low (New Jersey Transit appears capable of raising platforms for $25 million per station). However, commuter rail managers and suburban politicians are squeamish and ignorant of best practices and only really get peak ridership; thus, the higher peak ridership expected from the new tunnels not only improves the already-strong business case for high platforms, but also makes this business case easier to explain to people who think that off-peak, everyone must drive.

With such improvements to speed and reliability – modern rolling stock (which none of the region’s agencies is interested in acquiring), electrification, high platforms, some junction fixes, and better timetabling (which the region will have to adopt for greater peak throughput) combine to a speed increase of a factor of about 1.5, with all the benefits that this entails.

Necessary efficiencies

Much of the benefit of the Hudson Tunnel Project comprises necessary improvements on the surface, some of which I expect to happen as ancillaries. But then there is also the issue of necessary efficiencies in New York.

The issue is that the current operating paradigm involves very long turns at Penn Station. LIRR trains terminate from the east and New Jersey Transit trains terminate from the west, and neither railroad turns trains especially quickly. The turn times are on the order of 20 minutes; mainline trains in the United States can reverse direction in service in 10 minutes when they need to (for example, if they’ve arrived late), and even eight minutes look possible, and outside the United States, constrained terminals like Tokyo Station on the Chuo Line or Catalunya on FGC do it much faster.

The relevance is that agency officials keep saying, falsely, that Penn Station Expansion is necessary for the full increase in capacity coming from the new tunnels. But they are not going to get the money for the expansion; it competes with so many other priorities for a pool of money, $30 billion for the entire Northeast Corridor, that is large compared to normal-world costs but small compared to American ones. This means that they’re going to have to make necessary efficiencies.

Through-running is one such efficiency. But there are others – chiefly, turning faster at terminals, since the new tunnels would mainly feed stub-end tracks. This, in turn, means better service in general, with lower operating costs and (if there’s through-running) better service for passengers.

On just a raw estimate of extra peak capacity, there just isn’t enough ridership to justify $14-16 billion in funding for new tunnels. But once all the necessary improvements and efficiencies come in, the benefit-cost analysis looks much healthier. It doesn’t mean anyone should be happy about the budget – agencies and area advocates should do what they can to make sure money is saved and the same budget can build more things (like all these necessary improvements) – but it could be more like the extremely high-cost and yet high-benefit Second Avenue Suwbay phase 1 and not like the failure that is East Side Access.

The LIRR and East Side Access

East Side Access opened in February, about four months ago, connecting the LIRR to Grand Central; previously, trains only went to Penn Station. The opening was not at all smooth – commuters mostly wanted to keep going to Penn Station, contrary to early-2000s projections, and stories of confused riders were common in local media. I held judgment at the time because big changes take time to show their benefits, but in the months since, ridership has not done well. On current statistics, it appears that the opening of the new tunnel to Grand Central has had no benefit at all, making this project not just the world leader in tunneling cost per kilometer (about $4 billion) but also one with no apparent transportation value.

What is East Side Access?

Traditionally, of New York’s two main train stations, Penn Station only served Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and the LIRR, whereas Grand Central only served Metro-North. East Side Access is a tunnel from the LIRR Main Line to Grand Central, permitting trains to serve either of the two stations; an under-construction project called Penn Station Access likewise will permit one Metro-North line to serve Penn Station.

The tunnel across the East River was built in the 1970s and 80s together with the tunnel that now carries the F train; East Side Access was the project to build the connection from this tunnel to Grand Central as well as to the LIRR Main Line in Queens. The Grand Central connection does not lead to the preexisting Metro-North terminal with its tens of tracks, but to a deep cavern:

What was East Side Access supposed to serve?

Penn Station’s location is at the southwestern margin of the job concetration of Midtown Manhattan. Grand Central’s location is better; the studies done for the project 20 years ago found that for the majority of LIRR commuters, Grand Central was closer to their job than Penn Station. In 2019, there were 589,770 jobs within 1 km of Penn Station’s northeast corner at 7th and 33rd, of whom 48,460 lived on Long Island; within 1 km of Grand Central’s southern entrance at Park and 42nd, the corresponding numbers are 680,586 and 57,457.

Based on such analysis, the plan was to send as many trains as possible to Grand Central, at the expense of trains that used not to enter Manhattan at all but instead diverted to Downtown Brooklyn (within 1 km of Atlantic and Flatbush there were 41,360 jobs in 2019, of which 3,895 were held by Long Islanders). The central transfer point at Jamaica was reconfigured to no longer permit cross-platform transfers between Brooklyn- and Penn Station-bound trains in order to facilitate more direct trains to Grand Central.

The state promised large increases in both capacity and ridership; in 2022, joint Metro-North and LIRR head Catherine Rinaldi said they were increasing service by 40%. Unfortunately, ridership has flopped.

Ridership is a flop

The most recent publication about New York commuter rail ridership is from a week ago. LIRR ridership in May was about 5.6 million, with a peak of 229,000 passengers per weekday; ridership before corona was 316,000 per weekday. Metro-North, with no opening comparable to that of East Side Access, had 5.43 million riders in May with a peak of 215,000 passengers – but pre-corona ridership was 276,000. Metro-North has held up better the LIRR and recovered faster: May 2023 was 28% above May 2022, whereas for the LIRR, it was only 23%.

The same publication speaks of East Side Access positively – as it must, as an official report. It says the share of LIRR ridership is transitioning toward 65% Penn Station, 35% Grand Central. But this by itself already raises questions. The easier access to Grand Central and the extra capacity should have raised ridership; in the report, no surge is apparent since February of this year. Judging by the example of Metro-North, it appears that no net ridership has appeared as a result of the new project.

What’s going on here?

I’ve spent many years criticizing reverse-branching, in which a trunk line outside city center splits into branches in the core, in this case some trains serving Penn Station and others serving Grand Central. For East Side Access, my recommendation was to have one specific track pair, such as the express Main Line tracks, only carry trains to Grand Central, and the rest, such as the local tracks and Port Washington Branch tracks, only carry trains to Penn Station. The disappointing ridership of East Side Access has led some area transit advocates to criticize the MTA on the grounds that the problem is one of reverse-branching.

The media stories in late winter and early spring of confused commuters are certainly consistent with my criticism of reverse-branching. Everything that’s happened is consistent with that criticism, and yet I’m not certain that this is what’s going on. After all, East Side Access also adds new service and new capacity. Potentially, it’s about the loss of Jamaica transfers, but then which trains would people even want to transfer from?

The main mechanisms by which reverse-branching hurts ridership are that it makes schedule planning too complex and thereby reduces reliability, and that the frequency on each reverse-branch is reduced. LIRR scheduling is already extremely complex, with one-off express patterns and trains weaving around one another at rush hour; in 2015, I looked at some rush hour schedules and compared them with the rolling stock’s technical capabilities and found that even relative to the derated capabilities of the trains, the timetables are padded by 32% on the Main Line. (Metro-North seems comparably padded.) East Side Access would hardly make this much worse. The second mechanism is frequency – but at rush hour, frequency at each suburban station is decent, if not great.

But then, I can’t think of anything else that fits. The issue could not be some permanent decrease in commuting, or some permanent decrease in commuting to Grand Central specifically, since Metro-North ridership has recovered better and all trains there go to Grand Central. It could potentially be some force of habit inducing LIRR commuters to stay on the trains they’re familiar with, but then we should see gradual increase in ridership since opening and we’re not seeing that at any higher rate than at Metro-North.

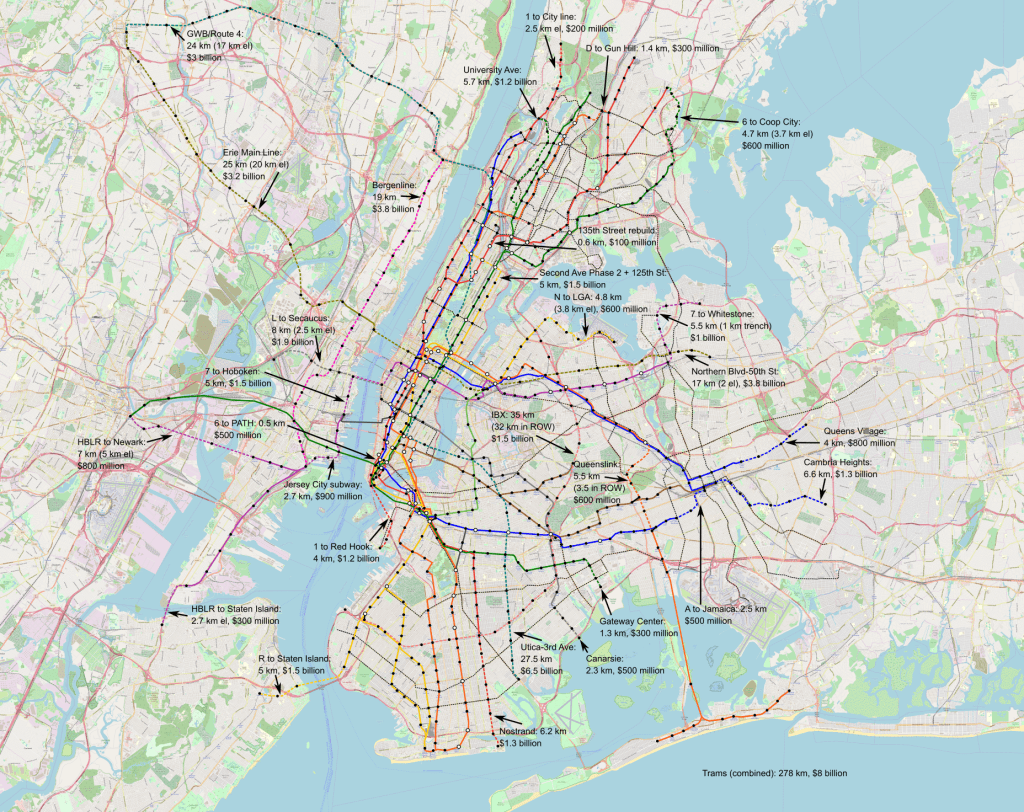

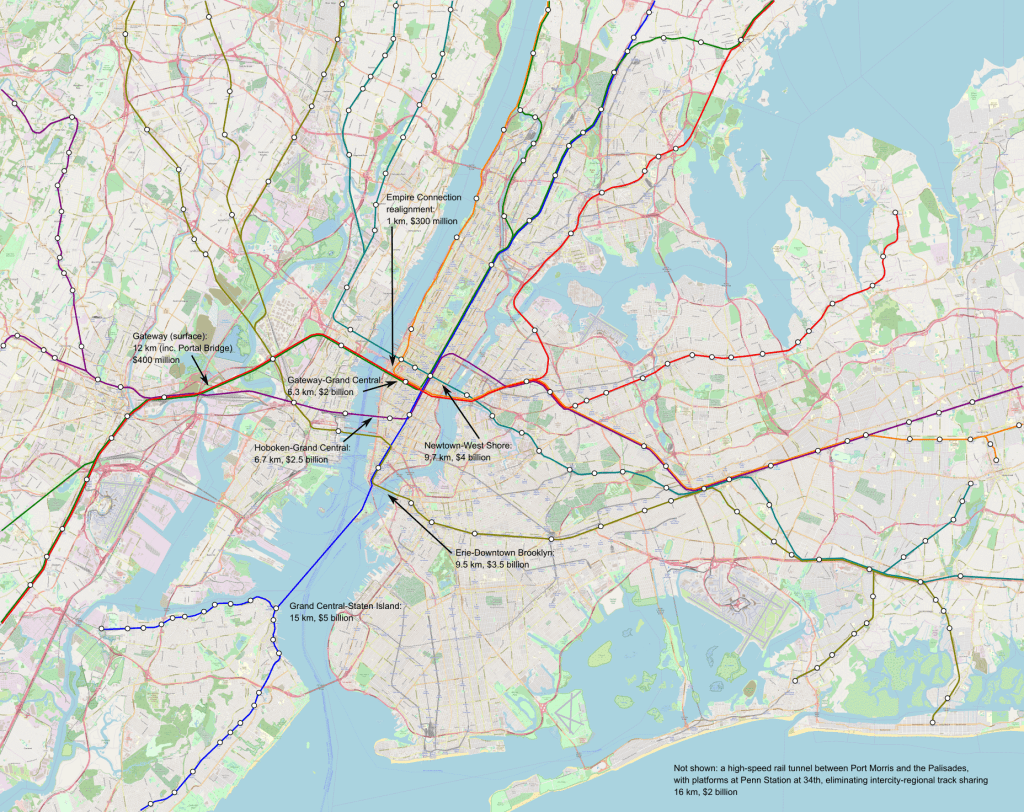

Assume Normal Costs: An Update

The maps below detail what New York could build if its construction costs were normal, rather than the highest in the world for reasons that the city and state could choose to change. I’ve been working on this for a while – we considered including these maps in our final report before removing them from scope to save time.

Higher-resolution images can be found here and here; they’re 53 MB each.

Didn’t you do this before?

Yes. I wrote a post to a similar effect four years ago. The maps here are updated to include slightly different lines – I think the new one reflects city transportation needs better – and to add light rail and not just subway and commuter rail tunnels. But more importantly, the new maps have much higher costs, reflecting a few years’ worth of inflation (this is 2022 dollars) and some large real cost increases in Scandinavia.

What’s included in the maps?

The maps include the following items:

- 278 km of new streetcars, which are envisioned to be in dedicated lanes; on the Brooklyn and Queensborough Bridges, they’d share the bridges’ grade separation from traffic into Manhattan, which in the case of the Brooklyn Bridge should be an elevated version of the branched subway-surface lines of Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and most German cities. Those should cost $8 billion in total, based on Eno’s European numbers plus some recent urban German projects.

- 240 km of new subway lines, divided as 147.6 km in the city (97.1 km underground) and 92.4 km across the Hudson and in New Jersey (45.2 km underground). Of those 240 km, 147.5 km comprise four new trunk lines, including the already-planned IBX, and the rest are extensions of existing lines. Those should cost $25.2 billion for the city lines and $15.4 billion for the New Jersey lines.

- Rearrangement of existing lines to reduce branching (“deinterlining“) and improve capacity and schedule robustness; the PATH changes are especially radical, turning the system into extensions of the 6 and 7 trains plus a Hoboken-Herald Square shuttle.

- 48.2 km of commuter rail tunnels, creating seven independent trunk lines across the region, all running across between suburbs through the Manhattan core. In addition to some surface improvements between New York and Newark, those should cost $17.7 billion, but some additional costs, totaling low single-digit billions, need to be incurred for further improvements to junctions, station platforms, and electrification.

The different mode of transportation are intended to work together. They’re split across two maps to avoid cluttering the core too much, but the transfers should be free and the fares should be the same within each zone (thus, all trains within the city must charge MetroCard/OMNY fare, including commuter rail and the JFK AirTrain). The best way to connect between two stations may involve changing modes – this is why there are three light rail lines terminating at or near JFK not connecting to one another except via the AirTrain.

What else is included?

There must be concurrent improvements in the quality of service and stations that are not visible on a map:

- Wheelchair accessibility at every station is a must, and must be built immediately; a judge with courage, an interest in improving the region, and an eye for enforcing civil rights and accessibility laws should impose a deadline in the early to mid 2030s for full compliance. A reasonable budget, based on Berlin, Madrid, and Milan, is about $10-15 million per remaining station, a total of around $4 billion.

- Platform edge doors at every station are a good investment as well. They facilitate air conditioning underground; they create more space on the platform because they make it easier to stand closer to the platform edge when the station is crowded; they eliminate deaths and injuries from accidental falls, suicides, and criminal pushes. The only data point I have is from Paris, where pro-rated to New York’s length it should be $10 million per station and $5 billion citywide.

- Signaling must be upgraded to the most modern standards; the L and 7 trains are mostly there already, with communications-based train control (CBTC). Based on automation costs in Nuremberg and Paris, this should be about $6 billion systemwide. The greater precision of computers has sped up Paris Métro lines by almost 20% and increased capacity. Together with the deinterlining program, a single subway track pair, currently capped at 24 trains an hour in most cases, could run about 40 trains per hour.

- Improvements in operations and maintenance efficiency don’t cost money, just political capital, but permit service to be more reliable while cutting New York’s operating expense, which are 1.5-2.5 time a high as the norm for large first-world subway systems.

The frequency on the subway and streetcar lines depicted on the map must conform to the Six-Minute Service campaign demand of Riders Alliance and allies. This means that streetcars and subway branches run very six minute all day, every day, and subway trunk lines like the 6, 7, and L get twice as much frequency.

What alternatives are there?

Some decisions on the map are set in stone: an extension of Second Avenue Subway into Harlem and thence west along 125th Street must be a top priority, done better than the present-day project with it extravagant costs. However, others have alternatives, not depicted.

One notable place where this could easily be done another way is the assignment of local and express trains feeding Eighth and Sixth Avenues. As depicted, in Queens, F trains run local to Sixth Avenue and E trains run express to Eighth; then, to keep the local and express patterns consistent, Washington Heights trains run local and Grand Concourse trains run express. But this could be flipped entirely, with the advantage of eliminating the awkward Jamaica-to-Manhattan-to-Jamaica service and replacing it with straighter lines. Or, service patterns could change, so that the E runs express in Queen and local in Manhattan as it does today.

Another is the commuter rail tunnel system in Lower Manhattan. There are many options for how to connect New Jersey, Lower Manhattan, and Brooklyn; I believe what I drew, via the Erie Railroad’s historic alignment to Pavonia/Newport, is the best option, but there are alternatives and all must be studied seriously. The location of the Lower Manhattan transfer station likewise requires a delicate engineering study, and the answer may be that additional stops are prudent, for example two stops at City Hall and South Ferry rather than the single depicted station at Fulton Street.

What are those costs?

I encourage people to read our costs report to look at what goes into the numbers. But, in brief, we’ve identified a recipe to cut New York subway construction costs by a factor of 9-10. On current numbers, this means New York can cut its subway construction costs to $200-250 million per kilometer – a bit less in the easiest places like Eastern Queens, somewhat more in Manhattan or across water. Commuter rail tunnel costs are higher, first because they tend to be built only in the most difficult areas – in easier ones, commuter rail uses legacy lines – and second because they involve bigger stations in more constrained areas. Those, too, follow what we’ve found in comparison cases in Southern Europe, the Nordic countries, Turkey, France, and Germany.

In total, the costs so projected on the map, $66.3 billion in total, are only slightly higher than the total cost of Grand Paris Express, which is $60 billion in 2022 dollars. But Paris is also building other Métro, RER, and tramway extensions at the same time; this means that even the program I’m proposing, implemented over 15 years, would still leave New York spending less money than Paris.

Is this possible?

Yes. The governance changes we outline are all doable at the state level; federal officials can nudge things and city politician can assist and support. There’s little confidence that current leadership even wants to build, let alone knows what to do, but it’s all doable, and our report linked in the lede provides the blueprint.

Through-Running and American Rail Activism

A bunch of us at the Effective Transit Alliance (mostly not me) are working on a long document about commuter rail through-running. I’m excited about it; the quality of the technical detail (again, mostly not by me) is far better than when I drew some lines on Google Maps in 2009-10. But it gets me thinking – how come through-running is the ask among American technical advocates for good passenger rail? How does it compare with other features of commuter rail modernization?

Note on terminology

In American activist spaces, good commuter rail is universally referred to as regional rail and the term commuter rail denotes peak-focused operations for suburban white flighters who work in city center and only take the train at rush hour. If that’s what you’re used to, mentally search-and-replace everything I say below appropriately. I have grown to avoid this terminology in the last few years, because in France and Germany, there is usually a distinction between commuter rail and longer-range regional rail, and the high standards that advocates demand are those of the former, not the latter. Thus, for me, a mainline rail serving a metropolitan area based on best practices is called commuter and not regional rail; there’s no term for the traditional American system, since there’s no circumstance in which it is appropriate.

The features of good commuter rail

The highest-productivity commuter rail systems I’m aware of – the Kanto area rail network, the Paris RER, S-Bahns in the major German-speaking cities, and so on – share certain features, which can be generalized as best practices. When other systems that lack these features adopt them, they generally see a sharp increase in ridership.

All of the features below fall under the rubric of planning commuter rail as a longer-range subway, rather than as something else, like a rural branch line or a peak-only American operation. The main alternative for providing suburban rapid transit service is the suburban metro, typical of Chinese cities, but the suburban metro and commuter rail models can coexist, as in Stockholm, and in either case, the point is to treat the suburbs as a lower-density, longer-distance part of the metropolitan area, rather than as something qualitatively different from the city. To effect this type of planning, all or nearly all of the following features are required, with the names typically given by advocates:

- Electrification/EMUs: the line must run modern equipment, comprising electric multiple units (self-propelled, with no separate locomotive) for their superior performance and reliability

- Level boarding/standing space: interior train design must facilitate fast boarding and alighting, including many wide doors with step-free boarding (which also provides wheelchair accessibility) and ample standing space within the car rather than just seated space, for example as in Berlin’s new Class 484

- Frequency: the headway between trains set at a small fraction of the typical trip time – neighborhoods 10 km from city center warrant a train every 5-10 minutes, suburbs 20-30 km out a train every 10-20 minutes, suburbs farther out still warrant a train every 20-30 minutes

- Schedule integration: train timetables must be planned in coordination with connecting suburban buses (or streetcars if available) to minimize connection time – the buses should be timed to arrive at each major suburban station just before the train departs, and depart just after it arrives

- Pedestrian-friendliness: train stations designed around connections with buses, streetcars if present, bikes, and pedestrian activity – park-and-rides are acceptable but should be used sparingly, and at stations in the suburbs, the nearby pedestrian experience must come first, in order to make the station area attractive to non-drivers

- Fare integration/Verkehrsverbund: the system may charge higher fares for longer trips, but the transfers to urban and suburban mass transit must be free even if different companies or agencies run the commuter trains and the city’s internal bus and rail system

- Infill: stations should be spaced regularly every 1-3 km within the built-up area, including not just the suburbs but also the city; slightly longer stop spacing may be acceptable if the line acts as an express bypass of a nearby subway line, but not the long stretches of express running American commuter trains do in their central cities

- Through-running: most trains that enter city center go through it, making multiple central stops, and then emerge on the other side to serve suburbs in that direction

Is through-running special?

Among the above features, through-running has a tendency to capture the imagination, because it lends itself to maps of how the lines fit together in the region; I’ve done more than my share of this, in the 2009 post linked in the intro, in 2014, in 2017, and in 2019. This is a useful feature, and in nearly every city with mainline rail, it’s essential to long-term modernization; the exceptions are cities where the geography puts the entirety of suburbia in one direction of city center, and even there, Sydney has through-running (all lines go west of city center) and Helsinki is building a tunnel for it (all lines go north).

The one special thing about through-running is that usually it is the most expensive item to implement, because it requires building new tunnels. In Philadelphia, this was the Center City Commuter Connection, opened in 1984. In Boston, it’s the much-advocated for North-South Rail Link. In Paris, Munich, Tokyo, Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Milan, Madrid, Sydney, Zurich, and other cities that I’m forgetting, this involved building expensive city center tunnels, usually more than one, to turn disparate lines into parts of a coherent metropolitan system. New York is fairly unique in already having the infrastructure for some through-running, and even there, several new tunnels are necessary for systemwide integration.

But there are so many other things that need to be done. In much of the United States, transit advocacy has recently focused on the issue of frequency, brought into the mainstream of advocacy by Jarrett Walker. Doing one without the other leads to awkward situations: after opening the tunnel, Philadelphia branded the lines R1 through R8 modeled on German S-Bahns while still running them hourly off-peak, even within the city, and charging premium fares even right next to overcrowded city buses.

This is something advocates generally understand. There’s a reason the TransitMatters Regional Rail program for commuter rail modernization puts the North-South Rail Link on the back burner and instead focuses on all the other elements. But there’s still something about through-running that lends itself to far more open argumentation than talking about off-peak frequency. Evidently, the Regional Plan Association and other organizations keep posting through-running maps rather than frequency maps or sample timetables.

Through-running as revolution

I suspect one reason for the special place of through-running, besides the attractiveness of drawing lines on a map, is that it most blatantly communicates that this is no longer the old failed system. There are good ways of running commuter rail, and bad ways, and all present-day American commuter rail practices are bad ways.

It’s possible to make asks about modernization that don’t touch through-running, such as integrating the fares; in Germany, the Verkehrsverbund concept goes back to the 1960s and is contemporary with the postwar S-Bahn tunnels, but Berlin and Hamburg had had through-running for decades before. But because these asks look small, it’s easy to compromise them down to nothing. This has happened in Boston, where there’s no fare integration on the horizon, but a handful of commuter rail stations have their fares reduced to be the same as on the subway, still with no free transfers.

Through-running is hard to compromise this way. As soon as the lines exist, they’re out there, requiring open coordination between different railroads, each of which thinks the other is incompetent and is correct. It’s hard to sell it as nothing, and thus it has to be done as a true leap generations forward, catching up with where the best places have been for 50+ years.

CNBC Video on Construction Costs

There’s a CNBC video about construction costs. It references our data a bunch, and I’d like to make a few notes about this.

Urban rail and GDP

CNBC opens by saying better urban rail would increase American GDP by 10%, sourcing the claim to our report. This isn’t quite right: our report references Hsieh-Moretti on upzoning in New York and the Bay Area; they estimate that relaxing zoning restrictions in those two regions to the US median starting in 1964 would have, assuming perfect mobility, raised American GDP by 9% in the conditions of 2009 (and the effect size should have grown since).

The relevance of transportation is that the counterfactual involves both regions growing explosively: New York employment grows by 1,010% more than in reality, so by a factor of about five compared with actual 1960s population and about 3.6 compared with actual 2009 (in 1969-2009, metro employment grew 35.4%), and likewise San Francisco would be 3.9 times bigger than in reality in 2009 and San Jose, having had much faster growth in the previous decades in reality, would have still been 2.5 times bigger. Hsieh-Moretti assume infrastructure expands to accommodate this growth. But if it can’t, then the growth in GDP is lower and the growth in consumer welfare is massively lower due to congestion externalities, hence our citation of Devin Bunten’s paper on this subject.