Category: New York

New York’s MTA Hates Transparency

The New York Post just published its piece, by Nolan Hicks, doing some construction cost comparisons. Nolan spoke to me multiple times on the subject of finding proper comparisons to New York’s subway station construction; he settled on the single most difficult Roman station, at the Colosseum, as well as a more prosaic station at Grand Paris Express and one on the Battersea extension in London. The goal was to look at the issue of New York’s overbuilt stations, with their full-length mezzanines and excessive back office space; New York’s stations turn out to be three to four times too expensive in his analysis.

So far, so good. But then there’s the official response to the story, which tells me that MTA head Janno Lieber is bad at his job – presuming that he views his job as about delivering good service, rather than stonewalling and kissing ass.

The Post quotes Lieber as saying, “you have to be careful with that subculture” and “those people get a lot of their cost information from the internet.” This is not too different from what he said when asked about our report by Jose Martinez: he got aggressive, said that we “group sourced” our data, and disclaimed responsibility for things that happened long ago, in the 2000s (Lieber at the time worked on the new World Trade Center).

People on Twitter are roasting Lieber about the phrases “that subculture” and “those people,” but I mind those appellations a lot less than what they are about. Lieber is in effect complaining that we use public sources for costs, which we access via the Internet, the same way we talk to other people in 2023. Using the Internet, for example, I can poke around for Swedish construction contracts, which are transparent with published lists of bidders and the winning bid, or I can look for historic German construction costs as reported in official channels and reputable media, and Marco can look for the same in Italy including publicly itemized costs, and Elif can look for the same in Turkey. What Lieber means when he says “information from the Internet” is really “articles in trade media and newspapers of record and detailed government reports, calibrated with some in-depth case studies to ensure we didn’t miss anything important.”

It jars him, perhaps because he’s used to secrecy. The idea that a report about the cost overruns of Grand Paris Express would just be out there, while the project was still going on, available to the public to review, may confuse Americans who are used to their country’s much lower level of transparency. In the US, everything requires affirmatively filing a freedom of information request that agencies can and often will deny on flimsy grounds. In Sweden, everything is online and I’ve been able to learn exactly how things work there from talking to not many people thanks to the wealth of public information about procurement strategy and individual contracts. The same is true of the issue of back office space and overbuilt station boxes – the MTA has not released blueprints, whereas in Sweden they’re available to the public in 3D.

Perhaps this is why Lieber talks to reporters with aggression and derision that fit would-be autocrats trying to put democratic media in its place. The idea that people would put all this information out there, voluntarily, seems weird to both, in the same way that a politician in an autocracy might find it jarring that politicians in democracies are subject to free media scrutiny.

This culture of secrecy cascades to itemized contracts. In our work, we’ve found that low-construction cost countries itemize their most complex rail infrastructure contracts, and the items are public. In the United States, contracts are fixed-price, and when agencies have itemized estimates as private benchmarks, they keep them from the public as a trade secret. MTA Construction and Development head Jamie Torres-Springer defended this system in November, saying that if the MTA revealed the numbers, contractors might use them as a floor.

Torres-Springer clearly stated a doctrine of the institutional culture that he and Lieber know. We can rate, overall, whether this culture is worth retaining, through seeing whether New York can build. It, of course, cannot. Lieber takes credit for delivering some projects for less than the budgeted amount, but the budget was inflated with large contingency figures; when someone promises to build something for $70 million and delivers it for $65 million, you don’t give credit for going under budget when other systems deliver it for $12 million. (These are all rough costs of making a subway station that is not a transfer wheelchair-accessible using three elevators in New York and some comparison cases respectively.)

Meanwhile, other systems, outside the high-cost Anglosphere (update 3-28: here is Ontario engaging in the same repulsive behavior toward Global News on the costs of the Ontario Line), can deliver. Germany doesn’t want to build much infrastructure unfortunately, but when it wants, it gets it done at reasonable if not low costs – and those costs are barely higher now in real terms than they were in the 1970s, having inched from maybe 150 million euros per km of subway to 200. Paris is building 200 km of mostly underground driverless metro, for about the same cost as one five-year MTA capital plan. Istanbul builds many metro lines all at once and may be the world’s top city in total route-length built this decade if Chinese investment slows down – Turkey is not a rich country but it has figured out how to build cheaply so that it can afford it. Seoul is expanding so rapidly, using so many different networks, that I can’t even track how much it builds. Italy not only can keep building infrastructure despite not having much money, but also managed to cut its real costs by adopting transparency as a core principle in the 1990s; contra Torres-Springer, contractors use published itemized costs as an anchor and not a floor.

But New York is the city that can’t, in the state that can’t. It treats a three-station subway expansion as a generational project. It clings to its way of doing things in face of obvious evidence that this way does not work; when it wants to do something different, it privatizes the state to consultants and huge design-build contractors, which has consistently raised costs wherever it is implemented. It’s not even aware of how success looks. Its leadership is rather like a Russian general who, seeing the army throw countless soldiers to take individual blocks of Bakhmut, population 70,000, insists things are going great and there is no need for anyone to learn anything about NATO standards, before ordering another wave of assault.

The press is ahead of the curve on this, since it does not need to kiss ass. I’ve been a source for New York media and for US-wide wonk networks for years, and the great majority of journalists I’ve spoken with, veterans and newcomers, generalists and specialists, have been curious and intelligent and could tell me important things I didn’t know before, including, in particular, reporters on this beat at all major city papers, such as Nolan. I sadly cannot say the same of MTA management: the career civil servants are good below the managerial level, the managers are hit-or-miss, and the political appointees are more miss than hit. The way the latter try to pull rank on good journalists like Martinez and Nolan is supercilious, authoritarian, and just plain nasty.

And if New York wants to avoid looking as ridiculous as that Russian general, it had better learn how successful cities do it, and invite in people who are intimately familiar with these cities to take in-house leadership jobs to implement the required reforms. This means, among other things, fostering a culture of openness and transparency. No more putdowns of journalists who ask hard questions, no more hiding behind NDAs and trade secrets, no more black boxes with no itemization beyond “this contract is $1 billion.” It’s easier than for Russia – the American field-grade officers who could do every Russian general’s job better don’t at all have Russia’s interests at heart, whereas the Continental European and East Asian transit managers who New York can bring it can be hired to have the MTA’s interests at heart, just as Andy Byford was. Learn from the best and face the reality that right now New York is the worst.

New York Can’t Build, LaGuardia Rail Edition

When Andrew Cuomo was compelled to resign, there was a lot of hope that the state would reset and finally govern itself well. The effusive language I was using at the time, in 2021 and early 2022, was shared by local advocates for public transportation and other aspects of governance. A year later, Governor Hochul has proven herself to be not much more competent than Cuomo, differing mainly in that she is not a violent sex criminal.

Case in point: the recent reporting that plans for rail to LaGuardia Airport are canceled, and the option selected for future development is just buses, makes it clear that New York can’t build. It’s an interesting case in which the decision, while bad, is still less bad than the justification for it. I think an elevated extension of the subway to LaGuardia is a neat project, but only at a normal cost, which is on the order of maybe $700 million for a 4.7 km extension, or let’s say $1 billion if it’s mostly underground. At New York costs, it’s fine to skip this. What’s not fine is slapping a $7 billion pricetag on such an endeavor.

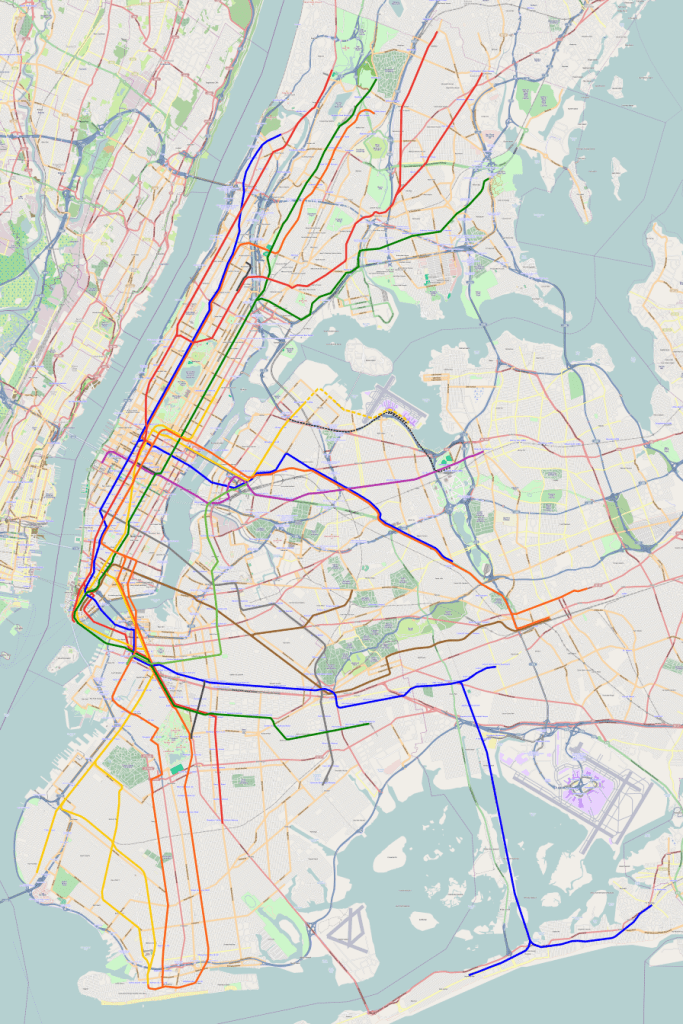

LaGuardia rail alignments

On my usual base map of a subway system with some lines swapped around to make the system more coherent but no new construction, here are the various rail alignments to the airport:

A full-size image can be found here. All alternatives are depicted as dashed lines; the subway extension is depicted in yellow in the same color as the Astoria Line, and would be elevated until it hit airport grounds, while the other two options, depicted as thinner black lines, are people movers or air trains. The air train option going east of airport grounds was Cuomo’s personal project and, since it went the wrong way, away from Manhattan, it was widely unpopular among anyone who did not work for Cuomo and was for all intents and purposes dead shortly after Hochul took office.

The issue of construction costs

Here’s what the above-linked New York Times article says about the rail alignments.

The panel’s three members — Janette Sadik-Khan, Mike Brown and Phillip A. Washington — said in a statement that they were unanimous in recommending that instead of building an AirTrain or extending a subway line to the airport, the Port Authority and the transportation authority should enhance existing Q70 bus service to the airport and add a dedicated shuttle between La Guardia and the last stop on the N/W subway line in Astoria.

The panel agreed that extending the subway to provide a “one-seat ride” from Midtown was “the optimal way to achieve the best mass transportation connection.” But they added that the engineers that reviewed the options could not find a viable way to build a subway extension to the cramped airport, which is hemmed in by the Grand Central Parkway and the East River.

Even if a way could be found to extend the subway that would not interfere with flight operations at La Guardia, the analysis concluded, it would take at least 12 years and cost as much as $7 billion to build.

The panel realized that the best option is an extension of the subway. Such an extension would be about 4.7 km long and around one third underground, or potentially around 5 km and entirely above-ground if for some reason tunneling under airport grounds were cost-prohibitive. This does not cost $7 billion, not even in New York. We know this, because Second Avenue Subway phase 1 was, in today’s money, around $2.2 billion per km, and phase 2 is perhaps a little more. There are standard subway : elevated cost ratios out there; the ones that emerge from our database tend to be toward the higher end perhaps, but still consistent with a ratio of about 2.5.

Overall, this is in theory pretty close to $7 billion for a one-third underground extension from Astoria to the airport. But in practice, the tunneling environment in question is massively easier than both phases of Second Avenue Subway – there’s plenty of space for cut-and-cover boxes in front of the terminal, a more controllable utilities environment, and not much development in the way of the elevated sections, which are mostly in an industrial zone to be redeveloped.

Does New York want to build?

New York can’t build. But to a significant extent, New York doesn’t even want to build. The report loves finding excuses why it’s not possible: they are squeamish about tunneling under the runways, they are worried an above-ground option would take lanes from the Grand Central Parkway (which a rail link would substitute for at higher capacity), they are worried about federal waivers.

In truth, in a constrained city, everything is under a waiver. In comments years ago, Richard Mlynarik pointed out that the desirable standard for railroad turnouts is that they should be straight – that is, the straight path should be on straight track, while the speed-restricted diverging path should curve away. But in practice, German train stations are full of curved turnouts, on which both paths are on a curve, because in a constrained urban zone it’s not possible to realize the desired standard, and a limit value is required. The same is true of any other engineering standard for a railroad, such as curve radii.

The issue of waivers is not limited to engineering or to rail. Roads are supposed to follow design standards, but land-constrained urban motorways are routinely on waivers. Even matters of safety can be grandfathered occasionally on a case-by-case basis. Financial and social standards are waived so often for urban megaprojects that it’s completely normal to decide them on a case-by-case basis; the United States doesn’t even have formal benefit-cost analyses the way Europe does.

And I’ve seen how American agencies are reluctant to even ask for waivers for things that politicians don’t really care about. Richard again brings up the example of platform heights on the San Francisco Peninsula: Caltrain rebuilt all platforms to a standard that didn’t have any level boarding, on the grounds that high platforms would interfere with oversize freight, which does not run on the line, and which the relevant state regulator, CPUC, indicated that they’d approve a waiver from if only the railroad asked. I have just seen an example of a plan to upgrade some stations in the Northeast that is running into trouble because the chosen construction material isn’t made in the United States, and even though “there’s no suitable made in America alternative” is legal grounds for a waiver from Buy America rules, the agency doesn’t so far seem interested in asking.

In general, New York can’t build. But in this case, it seems uninterested in even trying.

The bus alternative

Instead of a rail link, the plan now is to improve bus service. Here’s the New York Times story again:

The estimated $500 million in capital spending would also go toward creating dedicated bus lanes along 31st Street and 19th Avenue in Queens and making the Astoria-Ditmars Blvd. station on the N and W lines accessible to people with disabilities, the Port Authority said. Some of that money could also be spent to create a mile-long lane exclusive to buses on the northbound Brooklyn-Queens Expressway between Northern Boulevard and Astoria Boulevard, the Port Authority said.

Among the criticisms of the AirTrain plan was its indirect route. Arriving passengers bound for Manhattan would have had to travel in the opposite direction to catch a subway or L.I.R.R. train at Willets Point. The Port Authority chose that route, alongside the parkway, to minimize the need to acquire private property. Community groups were also concerned about the impact on property values in the neighborhoods near La Guardia in northern Queens.

To be very clear, it does not cost $500 million to make a station wheelchair-accessible. In New York, the average cost is around $70 million in 2021 dollars, with extensive contingency, planned by people who’d rather promise 70 and deliver 65 than promise 10 and deliver 12. In Madrid, the cost is around 10 million euros per station, with four elevators (the required minimum is three), and in Milan, shallow three-elevator station retrofits are around 2 million per station. Transfer stations cost more, proportionately to the number of lines served, but Astoria-Ditmars is not a transfer station and has no such excuse. So where is the other $430 million going?

The answer cannot just be bus lanes on 31st Street (on which the Astoria Line runs) or 19th Avenue (the industrial road the indicated extension on the map would run on). Bus lanes do not cost $430 million at this scale. They don’t normally cost anything – red paint and “bus only” markings are a rounding error, and bus shelter is $80,000 per stop with Californian cost control (to put things in perspective, I heard a $10,000-15,000 quote, in 2020 dollars, from a smaller American city).

We Gave a Talk About Our Construction Costs Report

Here are the slides; they are not in Beamer format but in Google Slides. They’re largely a summary of the New York report with analysis informed by the overview with more direct comparisons with other cities, and for example the recommendation section won’t tell you anything you didn’t know if you’ve read the overview or heard me talk about this issue before.

But I want to highlight one addition: the cost history of New York, on slides 5-8. Costs were elevated even in the 1930s; the references are JRTR for New York, Pascal Désabres for Paris, and Tube History for London. Midcentury New York costs are sourced to New York Magazine, with a Wikipedia article providing some references that match those numbers. The excessive costs of works in the 1930s ensured that the budget would not be sufficient to build desirable lines like Second Avenue Subway, an extension of the Nostrand Avenue Line to Sheepshead Bay, and a line under Utica; those costs kept growing into the 1950s and 60s, and the total amount of money at hand for Second Avenue Subway in the 1950s, about a fifth of the intended budget, would have built the entire line at the then-current costs of Milan or Stockholm. At even semi-reasonable costs, the budget identified for Second Avenue Subway in the late 1990s would have built the entire line, where instead it was cut into four phases with the money only sufficient to build the first.

The overall presentation was a bit stressful for me, especially at the beginning; the talk started at 3 in the afternoon and we finished the slide deck around 2:45. It was better afterward. One caution is that while the talk was recorded, it was a cellphone recording from the back, so Elif and I were not easy to hear. Another is that there were people I was hoping to talk to after the presentation that I didn’t get to; the attendance was on the order of 80 people, and we needed the full two hours we had the room booked for the presentation and Q&A afterward.

A number of people asked us if anything was changing. Eric seems more optimistic that people are listening. I’m less so; we’re talking to some people at government agencies but I can’t tell how important they are (I do not speak Washingtonian and cannot tell from the name and title of someone I talk to where they are on the spectrum of “someone who follows me on social media” to “Pete Buttigieg’s closest confidant”). At the MTA, things are not changing for the better; union head John Samuelsen is under the impression that French employers don’t have to pay pensions, MTA Construction and Development head Jamie Torres-Springer thinks the Second Avenue Subway stations have higher ridership than the stations of Citybanan, MTA head Janno Lieber is in full denial mode, and so on. The excuses might be getting more sophisticated, but, fundamentally, an American manager whose gut reaction to any kind of global benchmarking is to assert with perfect confidence that European employers don’t have to pay benefits needs to be fired and retrained, not given advice on how to come up with more plausibly-sounding excuses. Lieber and Torres-Springer are worth negative billions of dollars to the city and the state while they remain employed.

While some things are improving, the procurement problems are getting worse due to the growing privatization of the state, and, fundamentally, none of those people is willing to admit their mistake. There are some ongoing experiments in New York with itemized costs, but only as part of a PPP privatization, and only as pilots, where the place where itemizing costs and technical scoring are the most helpful is in the biggest and most complex contracts. Government-by-pilot doesn’t work any more than any of the other gimmicks that dimwitted political appointees use to avoid taking responsibility for decisions.

I’m Giving a Talk in New York on 3/3

We’re launching the Transit Costs Project conclusion and New York case this Friday at 3 pm. Unlike the October panel, this will not be moderated – Eric, Elif, and I will just talk about our report and take questions from the audience. While the talk will almost certainly be recorded, if you’re in the area you should still come in-person in order to be able to ask questions and interact.

As in our October event, the location is room 1201 of 370 Jay Street in Brooklyn, right on top of the subway stop that carries its name with A/C, F, and R service, and not far from other Downtown Brooklyn stops like Borough Hall on the 2/3/4/5, DeKalb Avenue on the B/Q, and Hoyt-Schermerhorn on the G. The building has access control so please tell us your name and email on this RSVP form so that security will know you can get in. If you crash the event you may still be allowed in but I won’t know until the day of, so do RSVP if you think you may attend; technically the room is capped at 180 people, around half seated, but I don’t expect to fill to even seated capacity, so don’t worry about taking someone else’s place.

Cost and Quality

From time to time, I see people assume that low-construction cost infrastructure must compromise on quality somehow. Perhaps it’s inaccessible: at a Manhattan Institute event from 2020, Philip Plotch even mentioned wheelchair accessibility as one factor leading to the increase in costs since the early 1900s; one of my long-term commenters on Twitter just repeated the same point. Perhaps the stations are cramped: I can’t count how many times I’ve heard the “transit riders deserve great stations” point from various Americans (there are several such examples in the thread in the last link alone), or for that matter from the people who built the Green Line Extension, and even Korean media got in on the action, falsely assuming that the spartan, brutalist stations of the Washington Metro were cheap (in fact, Washington is building an above-ground infill station for around an order of magnitude higher cost than Seoul’s cost for an underground infill station).

Please, stop.

If you want to know what very low-cost metro construction looks like, recall that the existing about 104 km (about 57 underground) Stockholm Metro was built in the middle of the 20th century for $3.6 billion in 2022 dollars. Here’s how the stations look:

Stockholm is famous for its exposed rock: the hard gneiss forms natural arches, and the T-bana elected to paint it over from the inside, producing the bright blue-and-white contrast with dark blue leaf paintings depicted above at T-Centralen. The stations look drastically different from one another, with many examples available from UrbanRail.Net, Flickr user Dyorex, Flickr user Kotka Molokovich, and the travel site Walk Slow Run Wild.

Swedish construction costs today are several times higher, but remain below world average, and are nearly a full order of magnitude lower than in New York. The stations remain artistic, but this coexists with consistent, standardized engineering specs, modified based on local conditions only when necessary. Citybanan’s Odenplan is not at all spartan; the entire station, berthing 214 meter trains mined below the T-bana station by the same name, cost $250 million in 2022 dollars, which cost includes not just the station but also 2 km of mined tunnel. The data that I’ve seen while researching our Sweden case suggests that Nya Tunnelbanan station costs are dominated by civil infrastructure and not systems or finishes, which look like they’re about a quarter of overall station costs, rather than nearly half as in New York. Nice art is not expensive; for that matter, New York’s subway stations have pretty tiles, and this includes old stations predating the 1930s’ cost explosion.

Moreover, I doubt it was the case when the system was first built, but nowadays the entire T-bana is accessible to wheelchair users. In fact, a number of metro systems have made themselves fully accessible or are in the process of doing so, generally at low costs; I have some numbers from 2019, and the programs cited for Berlin and Madrid are behind schedule, but Berlin seems to be sticking to a budget of 2 million € for an ordinary station, and even taking into account inflation that Berlin needs one elevator per station and most cities need three, this isn’t quite $10 million per station, a cost similar to that of Madrid’s ongoing program. In New York, the cost cited for accessibility is $70 million per station.

What goes on here isn’t really a matter of high quality for high cost. In fact, when Eric, Elif, and I researched the New York case, we were stricken by how little of the problem concerned actual quality or safety regulations (for example, the fire code in New York in practice requires mezzanines at the depth of Second Avenue, but does not require them to be full-length). The oversize stations are neither grand public atria nor revenue-generating commercial spaces, but rather conventional stations flanked by excessive amounts of back office space. The lack of standardization concerns fittings, not art. The massive costs of New York elevator installation are barely about redundancy (a requirement driven by low but fixable reliability) and largely about utility conflicts, bad-and-worsening project delivery, and the soft costs crisis.

Making the user experience worse is an easy way to signal that one is cutting costs. It’s a combination of vice-signaling and prudence theater. It also has little to do with how actually low-cost infrastructure construction programs look like. They can be highly standardized even without the artistic component found in Sweden and Finland, and then people may complain that the system looks bland and corporate – but bland and corporate is not the same as spartan, it just means it looks like the 21st century and not the imagined 20th.

Good systems are certainly not willing to make compromises on human rights and build inaccessible infrastructure. In Seoul, there are massive protests by disabled people demanding that the Seoul subway go from 93% to 100% accessible and that the bus fleet immediately be transitioned to low-floor equipment, and meanwhile, New York and London both loiter around 25-30% accessibility. The conservative governments of the state and the city both dither, but past competence by Korea has led to high expectations by users, in the same manner that people in developed country protest inequality and poverty even fully knowing that it’s nowhere near as bad as in the third world. While I don’t know Seoul’s accessibility costs, I do know a deep-bored Line 9 extension with an undercrossing of Line 5 is budgeted at $180 million/km.

Our Construction Costs Reports are Out!

Both the New York-specific report and the overall synthesis of all five cases plus more information from other cities are out, after three years of work.

At the highest level, it’s possible to break down the New York cost premium based on the following recipe:

To explain the animation a bit more:

- New York builds stations that are 3 times too expensive – either 3 times too big (96th Street) or twice as big but with a mining premium (72nd and 86th Streets). The 2.06 factor is what one gets when one takes into account that stations are 77% of Second Avenue Subway hard costs. This is independent of the issue of overall train size, which is longer in New York than in most (though not all) comparison cities.

- New York’s breakdown between civil structures and systems is about 53.5:46.5, where comparable cases are almost 3:1. This is caused by lack of standardization of systems and finishes, which ensures that even a large project has no economies of scale. This is a factor of about 2.3 increase in system costs, which corresponds to an overall cost increase of a factor of about 1.35. Together with the point above, this implies that the tunneling premium in New York is low, compared with system and station cost premiums, which I did notice in comparison with one Parisian project five years ago.

- Labor is 50% of the hard costs in the Northeastern United States; in our comparison cases, it ranges between 19% and 31%, and in Stockholm, which as the highest-wage comparison city is our closest analog for the United States, Citybanan’s contract costs were 23% labor. The difference between 50% labor and 25% labor is a factor of 3 difference in labor, coming from a combination of blue- and white-collar overstaffing and some agency turf battles that are represented as more workers, and a factor of 1.5 difference in overall costs.

- Procurement problems roughly double the costs; the factor of 1.85 is 2/1.08, dividing out by the usual 8% profit factor in Italy. Those problems can be broken out in different ways, but include red tape imposed by American agencies, red tape imposed by some specific regulations, a risk compensation factor whenever risk is privatized (just not itemizing costs by itself adds 10-20%, and there are other aspects of risk privatization).

- Third-party design costs add more. There are two ways to analyze it, both of which give about the same figure of a factor of 1.2 increase in costs: first, third-party design and management costs add 21% to Second Avenue Subway’s hard costs where various European comparanda add 7-8%, but the 21% should be incremented to 31% by adding the factor of 1.5 labor premium; and second, the inclusion of all soft costs combined is around 25% extra in Italy and 50% extra in New York, with the caveat that what counts as soft costs and what’s bundled into the hard costs sometimes differ.

I urge people to quote the cost premium as, at a minimum, a factor of 9-10, and not 9.34; please do not mistake the precision coming from needing to multiply numbers for accuracy.

I also urge people to read the conclusion and recommendations within the synthesis, because what we’ve learned the best practices are is not the same as what many reformers in the Anglosphere suggest. In particular, we urge more in-house hiring and deprivatization of risk, the exact opposite of the recipe that has been popularly followed in English-speaking countries in the last generation with such poor results.

Finally, if people have questions, please ask away! I read all comments here, and check email, and will vlog tomorrow on Twitch at 19:00 Berlin time and write any followups that are not already explained in the reports.

High Costs are not About Precarity

I’ve seen people who I think highly of argue that high construction costs in the United States are an artifact of precarity. The argument goes that the political support for public transportation there is so flimsy that agencies are forced to buy political support by spending more money than they need. This may include giving in to NIMBY pressure to use costlier but less impactful (or apparently less impactful) techniques, to spread money around with other government agencies and avoid fighting back, to build extravagant and fancier-looking but less standardized stations, and so on. The solution, per this theory, is to politically support public transportation construction more so that transit agencies will have more backing.

This argument also happens to be completely false, and the solution suggested is counterproductive. In fact, the worst cost blowouts are for the politically most certain projects; Second Avenue Subway enjoyed unanimous support in New York politics.

Cost-effectiveness under precarity

Three projects relevant to our work at the Transit Costs Project have been done exceptionally cost-effectively in an environment of political uncertainty: the T-bana, the LGV Sud-Est, and Bahn 2000.

T-bana

The original construction of the T-bana was done at exceptionally low cost. We go over this in the Sweden report to some extent, but, in short, between the 1950s and 70s, the total cost of the system’s construction was 5 billion kronor in 1975 prices, which built around 100 km, of which 57% are underground. In PPP 2022 dollars, this is $3.6 billion, or $35 million/km, not entirely but mostly underground. This was low for the time: for example, in London, the Victoria line was $122 million/km and the Jubilee line was $172 million/km (source, p. 78), and Italian costs in the 1960s and 70s were similar, averaging $129 million/km before 1970.

The era of Social Democrat dominance in Swedish politics on hindsight looks like one of consensus in favor of big public projects. But the T-bana itself was controversial. When the decision was made to build it in the 1940s, Stockholm County had about 1 million people; at the time, metros were present in much larger cities, like New York, London, Paris, Berlin, and Tokyo, and it was uncertain that a city the size of Stockholm would need such a system. Its closest analog, Copenhagen, did not build such a system until the 1990s, when it was a metro region of 2 million. It was uncertain that Stockholm should need rapid transit, and there were arguments for and against it in the city. Nor was there any transit-first policy in postwar Sweden: urban planning was the same modernist combination of urban renewal, automobile scale, and tower-in-a-park housing, and outside Stockholm County, the Million Program projects were thoroughly car-oriented.

Construction costs in Sweden are a lot higher now than they were in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Nya Tunnelbanan is $230 million/km, compared with a post-1990s Italian average of $220 million; British costs have exploded in tandem, so that now the Underground extensions clock at $600 million/km. Our best explanation is that the UK adopted what we call the globalized system of procurement, privatizing planning functions to consultants and privatizing risk to contractors, which creates more conflict; the UK also has an unusually high soft cost factor. From American data (and not just New York) and some British data, I believe that the roughly 2.5 cost premium of the UK over Italy is entirely reducible to such soft costs, procurement conflict, risk compensation, and excessive contingency. And yet, Sweden itself, with some elements of the same globalized system, maintains a roughly Italian cost level, albeit trending the wrong way.

And today, too, the politics of rail expansion in Sweden are uncertain. There was controversy over both Citybanan and Nya Tunnelbanan, neither of which passed a cost-benefit analysis (for reasons that I believe impugn the cost-benefit analysis more than those projects); it was uncertain that either would be funded. Controversy remained over plans to build high-speed rail connecting Stockholm with Gothenburg and Malmö, and the newly-elected right-wing government just canceled them in order to prioritize investment in roads. Swedish rail projects today remain precarious, and have to justify themselves on cost and efficiency grounds.

LGV Sud-Est

Like nearly all other rich countries, France was hit hard by the 1973 oil crisis; economic growth there and in the US, Japan, and most of the rest of Western Europe would never be as high as it was between the end of WW2 and the 1970s (“Trente Glorieuses“). On hindsight, France’s response to the crisis models can-go governance, with an energy saving ad declaring “in France we don’t have oil, but we have ideas.” The French state built nuclear power plants with gusto, peaking around 90% of national electricity use – and even today’s reduced share, around 70%, is by a large margin the highest in the world. At the same time, it built a high-speed rail network, connecting Paris with most other provincial cities at some of the highest average speeds outside China between major cities, reaching about 230 km/h between Paris and Marseille and 245 km/h between Paris and Bordeaux; usage per capita is one of the highest in Europe and, measured in passenger-km, not too bad by East Asian standards.

But in fact, the first LGV, the LGV Sud-Est, was deeply controversial. At the time, the only high-speed rail network in operation was the Shinkansen, and while France learned more from Japan than any other European country (for example, the RER was influenced by Tokyo rail operations), the circumstances for intercity were completely different. SNCF had benefited from having done many of its own experiments with high-speed technology, but the business case was murky. SNCF had to innovate in running an open system, with extensive through-running to cities off the line, which Japan would only introduce in the 1990s with the Mini-Shinkansen.

Within the French state, the project was controversial. Anthony Perl’s New Departures details how there were people within the government who wanted to cancel it entirely as it was unaffordable. At the end, the French state didn’t finance the line, and required SNCF to find private loans on the international market, though it did guarantee those loans. It also delayed the line’s opening: instead of opening the entire line from Paris to Lyon in one go, it opened two-thirds of it on the Lyon side in 1981 and the last third into Paris in 1983, requiring trains to run on the classical line at low speed between Paris and Saint-Florentin for two years; in that era, phased opening was uncommon, and lines generally opened to the end at once, such as between Tokyo and Shin-Osaka.

Construction was extraordinarily inexpensive. In PPP 2022 dollars, it cost $8.4 million/km. This is, by a margin, the lowest-cost high-speed rail line ever built that I know about. The Tokaido Shinkansen cost 380 billion yen, or in PPP 2022 dollars $40 million/km, representing a factor of two cost overrun that forced JNR’s head to resign. Spain has unusually low construction costs, and even there, Madrid-Seville was $15.7 million/km. SNCF innovated in every way possible to save money. Realizing that high-speed trains could climb steeper grades, it built the LGV Sud-Est with a ruling grade of 3.5%, which has since become a norm in and around Europe, compared with the Shinkansen’s 1.5-2%; the line has no tunnels, unlike the classical Paris-Lyon line. It built the line on the ground rather than on viaducts, and balanced cut and fill locally so that material cut to grade the line could be used for nearby fill. Thanks to the line’s low costs and high ridership, the financial return on investment for SNCF has been 15%, and social return on investment has been 30% (source, pp. 11-12).

This cost-effectiveness would never recur. The line’s success ensured that LGV construction would enjoy total political backing. The core features of LGV construction are still there – earthworks rather than viaducts, 3.5% grades, limited tunneling, overcompensation of landowners by about 30% with land swap deals to defuse the possibility of farmer riots. But the next few lines cost about $20 million/km or slightly less, and this cost has since crept up to about $30 million/km or even more. This remains low by international standards (but not by Spanish ones), but the trend is negative.

SNCF is coasting on its success from a generation ago, secure that funding for LGVs and state support in political contention is forthcoming, and the routing decisions have grown worse. In response to NIMBYism in Provence, the French state assented to a tunnel-heavy route, including a conversion of Marseille from an at-grade terminal to an underground through-station, akin to Stuttgart 21, which has not been done before in France, and the resulting high costs have led to delays on the project. Operations have grown ever more airline-style, experimenting with low-cost airline imitation to the point of reducing fare receipts without any increase in ridership. One of the French consultants we’ve spoken with said that their company’s third-party design costs are 7-8% of the hard costs, which figure is similar to what we’ve seen in Italy and to the in-house rate in Spain – but the same consultant told us that there is so much bloat at SNCF that when it designs its own projects, the costs are not 7% but 25%, a figure in line with American rates.

Bahn 2000

Switzerland has Europe’s strongest passenger rail network by all measures: highest traffic measured by passenger-km per capita, highest modal split for passenger-km, highest traffic density. Its success is well-known in surrounding countries, which are gradually either imitate its methods or, in the case of Germany, pretending to do so. It has achieved its success through continuous improvement over the generations, but the most notable element of this system was implemented in the 1990s as part of the Bahn 2000 project.

The current system is based on a national-scale clockface system (“Takt”) with trains repeating hourly, with the strongest links, like the Zurich-Bern-Basel triangle, running every half hour. Connections are timed in those three cities and several others, called knots, so that trains enter each station a few minutes before the connection time (usually the hour) and depart a few minutes after, permitting passengers to get between most pairs of Swiss cities with short transfers. Reliability is high, thanks to targeted investments designed to ensure that trains could make those connections in practice and not just in theory. Further planning centers adding more knots and expanding this system to the periphery of Switzerland.

Switzerland is famous for its consensus governance system – its plural executive is drawn from the four largest parties in proportion to their votes, with no coalition vs. opposition politics. But the process that led to the decision to adopt Bahn 2000 was not at all one of unanimity. There had been plans to build high-speed rail, as there were nearly everywhere else in Western Europe. But they were criticized for their high costs, and there was extensive center-right pressure to cut the budget. Bahn 2000 was thus conceived in an environment of austerity. Many of its features were explicitly about saving money:

- The knot system is connected with running trains as fast as necessary, not as fast as possible. Investments in speed are pursued only insofar as they permit trains to make their connections; higher speeds are considered gratuitous.

- Bilevel trains are an alternative to lengthening the platforms.

- Timed overtakes and meets are an alternative to more extensive multi-tracking of lines.

- Investment in better timetabling and systems (the electronics side of the electronics-before-concrete slogan) is cheaper than adding tunnels and viaducts.

Swiss megaprojects have to go to referendum, and sometimes the referendums return a no; this happened with the Zurich U-Bahn twice, leading to the construction of the S-Bahn instead. All Swiss planners know in a country this small and this fiscally conservative, any extravagance will lead to rejection. The result is that they’ve instead optimized construction at all levels, and even their unit costs of tunneling are low; thanks to such optimization, Switzerland has been able to build a fairly extensive medium-speed rail system, with more tunneling per capita than Germany (let alone France), and with two S-Bahn trunk tunnels in Zurich, where no German city today has more than one.

The American situation

The worst offenders in the United States are not at all politically precarious. There is practically unanimous consensus in New York about the necessity of Second Avenue Subway. At no point was the project under any threat. There is an ideological right in the city, rooted less in party politics and more in the New York Post and the Manhattan Institute, with a law-and-order agenda and hostility to unions and to large government programs, but at no point did they call for cancellation; the Manhattan Institute’s Nicole Gelinas has proposed pension cuts for workers and rule changes reducing certain benefits, but not canceling Second Avenue Subway.

At intercity scale, the same is true of Northeast Corridor investment. The libertarian and conservative pundits who say passenger rail is a waste of money tend to except the Northeast Corridor, or at least its southern half. When the Republicans won the 2010 midterm election, the new chair of the House of Representatives Transportation Committee, John Mica (R-FL), proposed a bill to seek private concessionaires to run intercity rail on the corridor. He did not propose canceling train service, even though in the wake of the same election, multiple conservative governors canceled intercity rail investments in their state, both high-speed (Florida) and low-speed (Wisconsin, Ohio).

In fact, both programs – New York subway expansion and the Northeast Corridor – are characterized by continuity across partisan shifts, as in more established consensus governance systems. The Northeast Corridor is especially notable for how little role ideological or partisan politics has played so far. New York has micromanagement by politicians – Andrew Cuomo had his pet projects in Penn Station Access and the backward-facing LaGuardia air train, and now Kathy Hochul has hers in the Interborough Express – but Second Avenue Subway was internal, and besides, political micromanagement is a different problem from political precarity.

And neither of these programs has engaged in any cost control. To the contrary, both are run as if money is infinite. The MTA would surrender to NIMBYs (“good neighbor policy”) and to city agencies looking to extract money from it. It built oversize stations. It spent money protecting buildings from excessive settlement that have been subsequently demolished for redevelopment at higher density.

The various agencies involved in the Northeast Corridor, likewise, are profligate, and not for lack of political support. Connecticut is full of NIMBYs; one of the consultants working on the plan a few years ago told me there was informal pressure not to ruffle feathers and not to touch anything in the wealthiest suburbs in the state, those of Fairfield County. In fact, high-speed rail construction would require significant house demolitions in the state’s second wealthiest town, Darien – but Darien is so infamously exclusive (“Darien rhymes with Aryan,” say other suburbanites in the area) that the rest of the region feels little solidarity with it.

NIMBYs aside, there has not been any effort at coordinating the different agencies in the Northeast along anything resembling the Swiss Takt system. This is not about precarity, because this is not a precarious project; this is about total ignorance and incuriosity about best practices, which emanate from a place that doesn’t natively speak English and doesn’t trade in American political references.

The Green Line Extension

Boston’s GLX is a fascinating example of cost blowouts without precarity. The history of the project is that its first iteration was pushed by Governor Deval Patrick (D), with the support of groups that sued the state for its delays in planning the project in the 1990s, as a court-mandated mitigation for the extra car traffic induced by the construction of the Big Dig. Patrick instituted a good neighbor policy, in which everything a community group wanted, it would get. Thus, stations were to become neighborhood signatures, and the project was laden with unrelated investments, called betterments, like a $100 million 3 km bike lane called the Somerville Community Path.

At no point in the eight years Patrick was in power was there a political threat to the project. It was court-mandated, and the extractive local groups that live off of suing the government favored it. The Obama administration was generous with federal stimulus funding, and the designs were rushed in order to use stimulus funding to pay for the project’s design, which would be done by consultants rather than with an expansion of in-house hiring. It’s in this atmosphere of profligacy that the project’s cost exploded to, in today’s money, around $3.5 billion, for 7 km of light rail in existing rights-of-way (albeit ones requiring overpass reconstruction).

The project did fall under political threat, after Charlie Baker (R) won the 2014 election. Baker’s impact on Massachusetts governance is fascinating, in that he unambiguously cut its budget significantly in the short run, but also had both before (as budget director in the 1990s) and during (through his actions as governor) wrecked the state’s long-term ability to execute infrastructure, setting up a machine intended to privatize the state and avoiding any in-house hiring. Nonetheless, the direct impact of precarity on GLX was to reduce scope: the betterments were removed and the stations were changed from too big to too small. The final cost was $2.3 billion, or around $2.8 billion in 2022 dollars, and half of that was sunk cot from the previous iteration.

There was no expectation that the project would be canceled – indeed, it was not. A Republican victory was unexpected in a state this left-wing. Then, as Baker was taking office, past governors from both parties expressed optimism that he would get not just GLX done but also the much more complex North-South Rail Link tunnel. Nor did contractors have their contracts yanked unexpectedly, which would get them to bid higher for risk compensation. Baker cold-shouldered not jut NSRL but also much smaller investments in commuter rail, but at no point was anyone stiffed in the process. No: the Patrick-era project was just poorly managed.

Project selection

As one caveat, I want to point out a place where precarity does lead to poor project cost-effectiveness: the project selection stage, in the context of tax referendums, especially in Southern California. None of this leads to high per-kilometer costs – Los Angeles’s are exactly as bad as in the rest of the United States – but it does lead to poor project selection, as an unintended consequence of anti-tax New Right politics.

The California-specific issue is that raising taxes requires a referendum, with a two-thirds vote. Swiss referendums are by simple majority, or at most double majority – but in practice most referendums that have a popular vote majority, even a small one, also have a double majority when needed, and in the last 15 years I believe the only two times they didn’t had the double majority veto overturning a 1.5% margin and a 9% margin.

California’s requirement of a two-thirds majority was intended to stop wasteful spending and taxation, but has had the opposite effect. In and around San Francisco, the voters are sufficiently left-wing that two-thirds majorities for social policy are not hard to obtain. But in Southern California, they are not; to build public transportation infrastructure, Los Angeles and San Diego County governments cannot rely on ideology, but instead cut deals with local, non-ideological actors through promising them a piece of the package. Los Angeles measures for transit expansion are, by share of money committed, largely not about transit expansion but operations, new buses, or leakage to roads and bridges; then, what does go to transit expansion is divvied by region, with each region getting something, no matter how cost-ineffective, while core improvements are neglected and so are cross-regional connections (since the local extractive actors aren’t going to ride the trains and can’t tell a circumferential project is useful for them).

This is not a US-wide phenomenon. It’s not even California-wide: this problem is absent from the Bay Area, where BART decided against an expansion to Livermore that was unpopular among technically-oriented advocates, and would like to build more core capacity if it could do so for much less than a billion dollars per km. New York does not have it at all (for one, it doesn’t require two-thirds majorities for budgeting).

At intercity scale, this precarity does cause Amtrak to maximize how many states and congressional districts it runs money-losing daily trains in. But wasting money on night trains and on peripheral regions is hardly a US-only problem – Japan National Railways did that until well past privatization, when its successors spun off money-losing branch lines to prefecture-subsidized third sector railways. This is not at all why there is no plan for Northeastern intercity rail that is worth its weight in dirt: Northeastern rail improvements have been amply funded relative to objective need (if not relative to American costs), and solid investments in the core coexist with wastes of money on the periphery of the network in many countries.

The issue of politicization

The precarious, low-cost examples all had to cut costs because of fiscal pressure. However, in all three, the pressure did not include any politicization of engineering questions. Sweden was setting up a civil service modeled on the American Bureau of Public Roads, currently the Federal Highway Administration, which in the middle of the 20th century was a model of depoliticized governance. France and Switzerland have strong civil service bureaucracies – if anything SNCF is too self-contained and needs reorganization, just not if it’s led by the usual French elites or by people from the airline industry.

Importantly, low-cost countries with more clientelism and politicization of the state tend to be more deferential to the expertise of engineers. Greece has a far worse problem of overreliance on political appointees than the United States, let alone the other European democracies; but engineering is somewhat of an exception. Hispanic and Portuguese-speaking cultures put great prestige on engineering, reducing the extent of political micromanagement, even in countries without strong apolitical civil service bureaucracies. Even in Turkey, the politicization of public transportation is entirely at macro level: AKP promises to prioritize investment in areas that vote for it and has denied financing to the Istanbul Metro since the city flipped to the opposition (the city instead borrows money from the European Investment Bank), but below that level there is no micromanagement.

The American examples, in contrast, show much more political micromanagement. This is part of the same package as the privatization of state planning in the globalized system; in the United States often there was never the depoliticization that most of the rest of the developed and middle-income world had, but on top of that, the tendency has been to shut down in-house planning departments or radically shrink them and replace them with consultants. The consultants are then supervised by political appointees with no real qualifications to head capital programs, and the remaining civil servants are browbeaten not to disagree with the political appointees’ proclamations.

Those political appointees rarely measure themselves by any criteria of infrastructure utility. Even in New York they and the managers don’t consistently use the system; in Los Angeles, they use it about as often as the executive director of a well-endowed charity eats at a soup kitchen. To them, the cost is itself a measure of success – and this is true of other agencies, which treat obtaining other people’s money as a mark of achievement and as testament to their power. This behavior then cascades to local advocacy groups, which try to push solutions that maximize outside funding and are at bet indifferent and at worst actively hostile to any attempt at efficiency.

Just giving more support to agencies in their current configuration is not going to help. To the contrary, it only confirms that profligacy gets rewarded. A program of depoliticization of the state is required in tandem with expanding in-house hiring and reversing the globalized system, and the political appointees and the managers and political advocates who are used to dealing with them don’t belong in this program.

Edge Cities With and Without Historic Cores

An edge city is a dense, auto-oriented job center arising from nearby suburban areas, usually without top-down planning. The office parks of Silicon Valley are one such example: the area had a surplus of land and gradually became the core of the American tech industry. In American urbanism, Tysons in Virginia is a common archetype: the area was a minor crossroads until the Capital Beltway made it unusually accessible by car, providing extensive auto-oriented density with little historic core.

But there’s a peculiarity, I think mainly in the suburbs of New York. Unlike archetypal edge cities like Silicon Valley, Tysons, Century City in Los Angeles, or Route 128 north of Boston, some of the edge cities of New York are based on historic cores. Those include White Plains and Stamford, which have had booms in high-end jobs in the last 50 years due to job sprawl, but also Mineola, Tarrytown, and even New Brunswick and Morristown.

The upshot is that it’s much easier to connect these edge cities to public transportation than is typical. In Boston, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure out good last mile connections from commuter rail stations. Getting buses to connect outlying residential areas and shopping centers to town center stations is not too hard, but then Route 128 is completely unviable without some major redesign of its road network: the office parks front the freeway in a way that makes it impossible to run buses except dedicated shuttles from one office park to the station, which could never be frequent enough for all-day service. Tysons is investing enormous effort in sprawl repair, which only works because the Washington Metro could be extended there with multiple stations. Far and away, these edge cities are the most difficult case for transit revival for major employment centers.

And in New York, because so much edge city activity is close to historic cores, this is far easier. Stamford and White Plains already have nontrivial if very small transit usage among their workers, usually reverse-commuters who live in New York and take Metro-North. Mineola could too if the LIRR ran reverse-peak service, but it’s about to start doing so. Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow could be transit-accessible. The New Jersey edge cities are harder – Edison and Woodbridge have lower job density than Downtown Stamford and Downtown White Plains – but there are some office parks that could be made walkable from the train stations.

I don’t know what the history of this peculiar feature is. White Plains and Mineola are both county seats and accreted jobs based on their status as early urban centers in regions that boomed with suburban sprawl in the middle of the 20th century. Tarrytown happened to be the landfall of the Tappan Zee Bridge. Perhaps this is what let them develop into edge cities even while having a much older urban history than Tysons (a decidedly non-urban crossroads until the Beltway was built), Route 128, or Silicon Valley (where San Jose was a latecomer to the tech industry).

What’s true is that all of these edge cities, while fairly close to train stations, are auto-oriented. They’re transit-adjacent but not transit-oriented, in the following ways:

- The high-rise office buildings are within walking distance to the train station, but not with a neat density gradient in which the highest development intensity is nearest the station.

- The land use at the stations is parking garages for the use of commuters who drive to the station and use the train as a shuttle from a parking lot to Manhattan, rather than as public transportation the way subway riders do.

- The streets are fairly hostile to pedestrians, featuring fast car traffic and difficult crossing, without any of the walkability features that city centers have developed in the last 50 years.

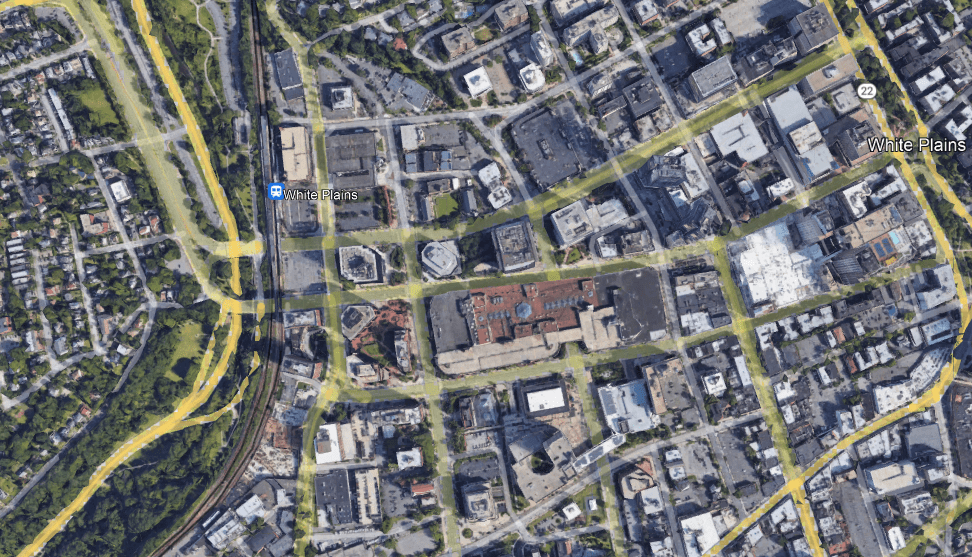

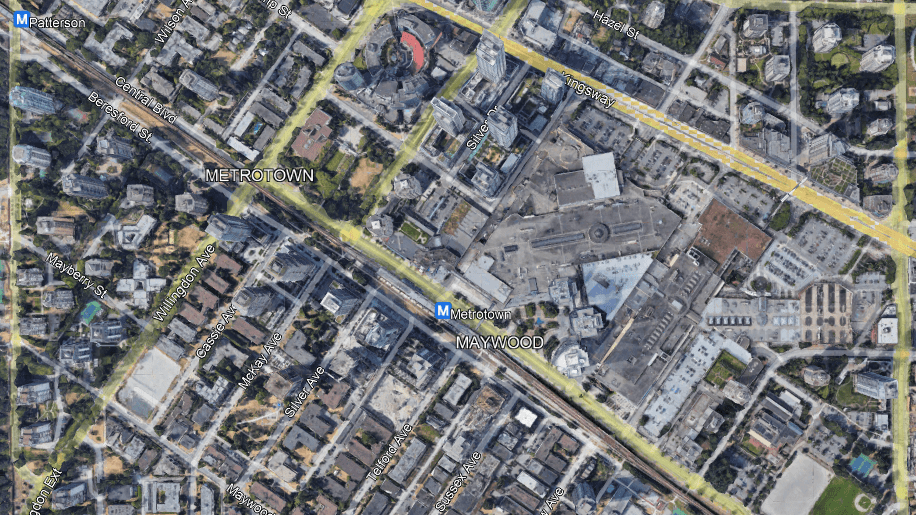

The street changes required are fairly subtle. Let us compare White Plains with Metrotown, both image grabs taken from the same altitude:

These are both edge cities featuring a train station, big buildings, and wide roads. But in Metrotown, the big buildings are next to the train station, and the flat-looking building to its north is the third-largest shopping mall in Canada. The parking goes behind the buildings, with some lots adjoining Kingsway, which has a frequent trolleybus (line 19) but is secondary as a transportation artery to SkyTrain. Farther away, the residential density remains high, with many high-rises in the typical thin-and-tall style of Vancouver. In contrast, in White Plains, one side of the station is a freeway with low-density residential development behind it, and the other is parking garages with office buildings behind them instead of the reverse.

The work required to fix this situation is not extensive. Parking must be removed and replaced with tall buildings, which can be commercial or residential depending on demand. This can be done as part of a transit-first strategy at the municipal level, but can also be compelled top-down if the city objects, since the MTA (and other Northeastern state agencies) has preemption power over local zoning on land it owns, including parking lots and garages.

On the transit side, the usual reforms for improvements in suburban trains and buses would automatically make this viable: high local frequency, integrated bus-rail timetables (to replace the lost parking), integrated fares, etc. The primary target for such reforms is completely different – it’s urban and inner-suburban rail riders – but the beauty of the S-Bahn or RER concept is that it scales well for extending the same high quality of service to the suburbs.

Schedule Planners as a Resource

The Effective Transit Alliance published its statement on Riders Alliance’s Six-Minute Service campaign, which proposes to run every subway line in New York and the top 100 bus routes every (at worst) six minutes every day from morning to evening. We’re positive on it, even more than Riders Alliance is. We go over how frequency benefits riders, as I wrote here and here, but also over how it makes planning easier. It is the latter benefit I want to go over right now: schedule planning staff is a resource, just as drivers and outside capital are, and it’s important for transit agencies to institute systems that conserve this resource and avoid creating unnecessary work for planners.

The current situation in New York

Uday Schultz writes about how schedule planning is done in New York. There’s an operations planning department, with 350 budgeted positions as of 2021 of which 284 are filled, down from 400 and 377 respectively in 2016. The department is responsible for all aspects of schedule planning: base schedules but also schedules for every service change (“General Order” or GO in short).

Each numbered or lettered route is timetabled on it own. The frequency is set by a guideline coming from peak crowding: at any off-peak period, at the most crowded point of a route, passenger crowding is supposed to be 25% higher than the seated capacity of the train; at rush hour, higher standee crowding levels are tolerated, and in practice vary widely by route. This way, two subway routes that share tracks for a long stretch will typically have different frequencies, and in practice, as perceived by passengers, off-peak crowding levels vary and are usually worse than the 25% standee factor.

Moreover, because planning is done by route, two trains that share tracks will have separate schedule plans, with little regard for integration. Occasionally, as Uday points out, this leads to literally impossible schedules. More commonly, this leads to irregular gaps: for example, the E and F trains run at the same frequency, every 4 minutes peak and every 12 minutes on weekends, but on weekends they are offset by just 2 minutes from each other, so on the long stretch of the Queens Boulevard Line where they share the express tracks, passengers have a 2-minute wait followed by a 10-minute wait.

Why?

The current situation creates more work for schedule planners, in all of the following ways:

- Each route is run on its own set of frequencies.

- Routes that share tracks can have different frequencies, requiring special attention to ensure that trains do not conflict.

- Each period of day (morning peak, midday, afternoon peak, evening) is planned separately, with transitions between peak and off-peak; there are separate schedules for the weekend.

- There are extensive GOs, each requiring not just its own bespoke timetable but also a plan for ramping down service before the start of the GO and ramping it up after it ends.

This way, a department of 284 operations planners is understaffed and cuts corners, leading to irregular and often excessively long gaps between trains. In effect, managerial rules for how to plan trains have created makework for the planners, so that an objectively enormous department still has too much work to do and cannot write coherent schedules.

Creating less work for planners

Operations planners, like any other group of employees, are a resource. It’s possible to get more of this resource by spending more money, but office staff is not cheap and American public-sector hiring has problems with uncompetitive salaries. Moreover, the makework effect doesn’t dissipate if more people are hire – it’s always possible to create more work for more planners, for example by micromanaging frequency at ever more granular levels.

To conserve this resource, multiple strategies should be used:

Regular frequencies

If all trains run on the same frequency all day, there’s less work to do, freeing up staff resources toward making sure that the timetables work without any conflict. If a distinction between peak and base is required, as on the absolute busiest routes like the E and F, then the base should be the same during all off-peak periods, so that only two schedules (peak and off-peak) are required with a ramp-up and ramp-down at the transition. This is what the six-minute service program does, but it could equally be done with a more austere and worse-for-passengers schedule, such as running trains every eight minutes off-peak.

Deinterlining

Reducing the extent of reverse-branching would enable planning more parts of the system separately from one another without so much conflict. Note that deinterlining for the purposes of good passenger service has somewhat different priorities from deinterlining for the purposes of coherent planning. I wrote about the former here and here. For the latter, it’s most important to reduce the number of connected components in the track-sharing graph, which means breaking apart the system inherited from the BMT from that inherited from the IND.

The two goals share a priority in fixing DeKalb Avenue, so that in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, the B and D share tracks as do the N and Q (today, in Brooklyn, the B shares track with the Q whereas the D shares track with the N): DeKalb Junction is a timetabling mess and trains have to wait two minutes there for a slot. Conversely, the main benefit of reverse-branching, one-seat rides to more places, is reduced since the two Manhattan trunks so fed, on Sixth Avenue and Broadway, are close to each other.

However, to enable more convenient planning, the next goal for deinterlining must be to stop using 11th Street Connection in regular service, which today transitions the R from the BMT Broadway Line and 60th Street Tunnel to the IND Queens Boulevard local tracks. Instead, the R should go where Broadway local trains go, that is Astoria, while the Broadway express N should go to Second Avenue Subway to increase service there. The vacated local service on Queens Boulevard should go to IND trunks in Manhattan, to Eighth or Sixth Avenue depending on what’s available based on changes to the rest of the system; currently, Eighth Avenue is where there is space. Optionally, no new route should be added, and instead local service on Queens Boulevard could run as a single service (currently the M) every 4 minutes all day, to match peak E and F frequencies.

GO reform

New York uses too many GOs, messing up weekend service. This is ostensibly for maintenance and worker safety, but maintenance work gets done elsewhere with fewer changes (as in Paris or Berlin) or almost none (as in Tokyo) – and Berlin and Tokyo barely have nighttime windows for maintenance, Tokyo’s nighttime outages lasting at most 3-4 hours and Berlin’s available only five nights a week. The system should push back against ever more creative service disruptions for work and demand higher maintenance productivity.

TransitCenter’s Commuter Rail Proposal

Last week, TransitCenter released a proposal for how to use commuter rail more effectively within New York. The centerpiece of the proposal is to modify service so that the LIRR and Metro-North can run more frequently to stations within the city, where today they serve the suburbs almost exclusively; at the few places near the outer end of the city where they run near the subway, they have far less ridership, often by a full order of magnitude, which pattern repeats itself around North America. There is much to like about what the proposal centers; unfortunately, it falls short by proposing half-hourly frequencies, which, while better than current off-peak service, are far short of what is needed within the city.

Commuter rail and urban ridership

TransitCenter’s proposal centers urban riders. This is a welcome addition to city discourse on commuter rail improvement. The highest-ridership, highest-traffic form of mainline rail is the fundamentally urban S-Bahn or RER concept. Truly regional trains, connecting distinct centers, coexist with them but always get a fraction of the traffic, because public transit ridership is driven by riders in dense urban and inner-suburban neighborhoods.

A lot of transit and environmental activists are uncomfortable with the idea of urban service. I can’t tell why, but too many proposals by people who should know better keep centering the suburbs. But in reality, any improvement in commuter rail service that does not explicitly forgo good practices in order to discourage urban ridership creates new urban ridership more than anything else. There just aren’t enough people in the suburbs who work in the city (even in the entire city, not just city center) for it to be any other way.

TransitCenter gets it. The proposal doesn’t even talk about inner-suburban anchors of local lines just outside the city, like Yonkers, New Rochelle, and Hempstead (and a future update of this program perhaps should). No: it focuses on the people near LIRR and Metro-North stations within the city, highlighting how they face the choice between paying extra for infrequent but fast trains to Midtown and riding very slow buses to the edge of the subway system. As these neighborhoods are for the most part on the spectrum from poor to lower middle-class, nearly everyone chooses the slow option, and ridership at the city stations is weak, except in higher-income Northeast Queens near the Port Washington Branch (see 2012-4 data here, PDF-pp. 183-207), and even there, Flushing has very little ridership since the subway is available as an alternative.

To that effect, TransitCenter proposes gradually integrating the fares between commuter rail and urban transit. This includes fare equalization and free transfers: if a bus-subway-bus trip between the Bronx and Southern Brooklyn is covered by the $127 monthly pass then so should a shorter bus-commuter rail trip between Eastern Queens or the North Bronx and Manhattan.

Interestingly, the report also shows that regionwide, poorer people have better job access by transit than richer people, even when a fare budget is imposed that excludes commuter rail. The reason is that in New York, suburbanization is a largely middle-class phenomenon, and in the suburbs, the only jobs accessible by mass transit within an hour are in Midtown Manhattan, whereas city residents have access to a greater variety of jobs by the bus and subway system. But this does not mean that the present system is equitable – rich suburbanites have cars and can use them to get to edge city jobs such as those of White Plains and Stamford, and can access the entire transit network without the fare budget whereas poorer people do have a fare budget.

The issue of frequency

Unfortunately, TransitCenter’s proposal on frequency leaves a lot to be desired. Perhaps it’s out of incrementalism, of the same kind that shows up in its intermediate steps toward fare integration. The report suggests to increase frequency to the urban stations to a train every half an hour, which it phrases in the traditional commuter rail way of trains per day: 12 roundtrips in a six-hour midday period.

And this is where the otherwise great study loses me. Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, and Flushing are all right next to subway stations. The LIRR charges higher fares there, but these are fairly middle-class areas – richer than Rosedale in Southeast Queens on the Far Rockaway Branch, which still gets more ridership than all three. No: the problem in these inner areas is frequency, and a train every half hour just doesn’t cut it when the subway is right there and comes every 2-3 minutes at rush hour and every 4-6 off-peak.

In this case, incremental increases from hourly to half-hourly frequency don’t cut it. The in-vehicle trip is so short that a train every half hour might as well not exist, just as nobody runs subway trains every half hour (even late at night, New York runs the subway every 20 minutes). At outer-urban locations like Bayside, Wakefield, and Rosedale, the absolute worst that should be considered is a train every 15 minutes, and even that is suspect and 10 minutes is more secure. Next to the subway, the absolute minimum is a train every 10 minutes.

All three mainlines currently radiating out of Manhattan in regular service – the Harlem Line, the LIRR Main Line, and the Port Washington Branch – closely parallel very busy subway trunk lines. One of the purposes of commuter rail modernization in New York must be decongestion of the subway, moving passengers from overcrowded 4, 5, 7, E, and F trains to underfull commuter trains. The LIRR and Metro-North are considered at capacity when passengers start having to use the middle seats, corresponding to 80% of seated capacity; the subway is considered at capacity when there are so many standees they don’t meet the standard of 3 square feet per person (3.59 people/m^2).

To do this, it’s necessary to not just compete with buses, but also directly compete with the subway. This is fine: Metro-North and the LIRR can act as additional express capacity, filling trains every 5 minutes using a combination of urban ridership and additional ridership at inner suburbs. TransitCenter has an excellent proposal for how to improve service quality at the urban stations but then inexplicably doesn’t go all the way and proposes a frequency that’s too low.