Category: High-Speed Rail

What is Incrementalism, Anyway?

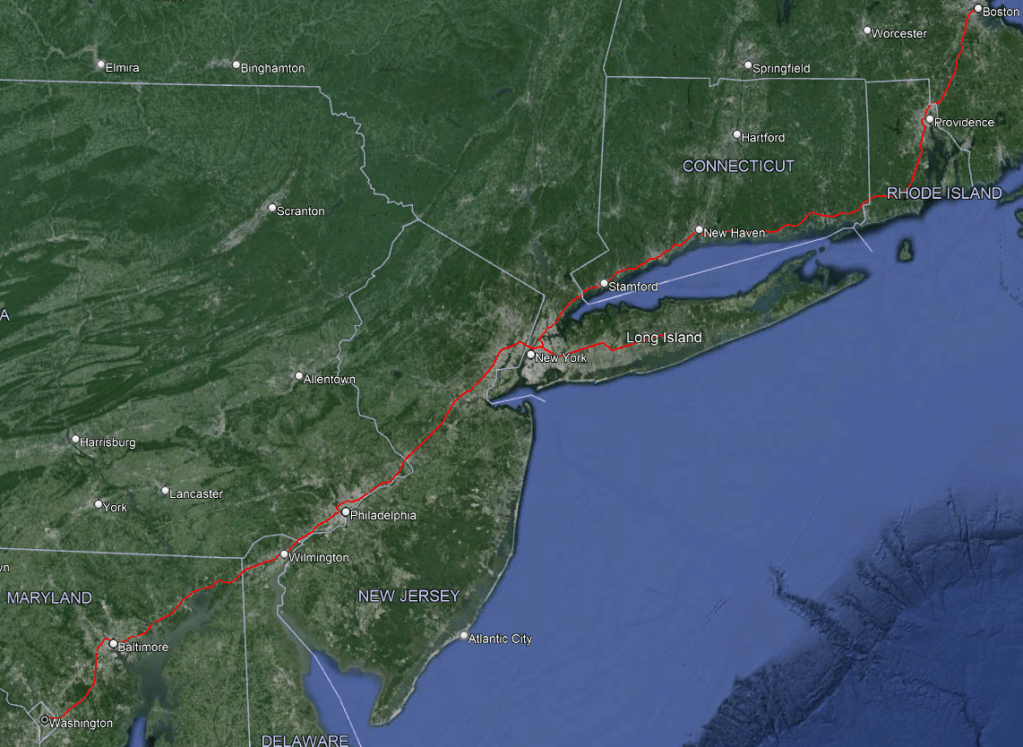

The American conversation about high-speed rail has an internal debate that greatly bothers me, about whether investments should be incremental or not. An interview with the author of a new book about the Northeast Corridor reminded me of this; this is not the focus of the interview, but there was an invocation of incremental vs. full-fat high-speed rail, which doesn’t really mean much. The problem is that the debate over incrementalism can be broken down into separate categories – infrastructure, top speed, planning paradigm, operations, marketing; for example, investment can be mostly on existing tracks or mostly on a new right-of-way, or something in between, but this is a separate questions from whether operations planning should remain similar to how it works today or be thrown away in favor of something entirely new. And what’s more, in some cases the answers to these questions have negative rather than positive correlations – for example, the most aggressively revolutionary answer for infrastructure is putting high-speed trains on dedicated tracks the entire way, including new urban approaches and tunnels at all major cities, but this also implies a deeply conservative operating paradigm with respect to commuter rail.

Instead of talking about incrementalism, it’s better to think in terms of these questions separately. As always, one must start with goals, and then move on to service planning, constraints, and budgets.

Planners who instead start with absolute political demands, like “use preexisting rights-of-way and never carve new ones through private property,” end up failing; California High-Speed Rail began with that demand, as a result of which it planned to use existing freight rail corridors that pass through unserved small towns with grade crossings; this was untenable, so eventually the High-Speed Rail Authority switched to swerving around these unserved towns through farmland, but by then it had made implicit promises to the farmers not to use eminent domain on their land, and when it had to violate the promise, it led to political controversy.

Switzerland

Instead of California’s negative example, we can look to more successful ones, none of which is in an English-speaking country. I bring up Switzerland over and over, because as far as infrastructure goes, it has an incremental intercity rail network – there are only a handful of recently-built high-speed lines and they’re both slow (usually 200 km/h, occasionally 250 km/h) and discontinuous – but its service planning is innovative. This has several features:

Infrastructure-rolling stock-timetable integration

To reduce the costs of infrastructure, Swiss planning integrates the decision of what kind of train to run into the investment plan. To avoid having to spend money on lengthening platforms, Switzerland bought double-deck trains as part of its Rail 2000 plan; double-deckers have their drawbacks, mainly in passenger egress time, but in the case of Switzerland, which has small cities with a surplus of platform tracks, double-deckers are the right choice.

California made many other errors, but its decision to get single-deck trains is correct in its use case: the high-speed trainset market is almost entirely single-deck, and the issue of platform length is not relevant to captive high-speed rail since the number of stations that need high-speed rail service is small and controllable.

Timetable integration is even more important. If the point is to build a rail network for more than just point-to-point trips connecting Zurich, Basel, Bern, and Geneva, then trains have to connect at certain nodes; already in the 1970s, SBB timetables were such that trains arrived at Zurich shortly before the hour every hour and departed on or shortly after the hour. The Rail 2000 plan expanded these timed connections, called Knoten or knots, to more cities, and prioritized speed increases that would enable trains to connect two knots in just less than an hour, to avoid wasting time for passengers and equipment. The slogan is run trains as fast as necessary, not as fast as possible: expensive investment is justifiable to get the trip times between two knots to be a little less than an hour instead of a little more than an hour, but beyond that, it isn’t worth it, because connecting passengers would not benefit.

Tunnels where necessary

The incremental approach of Rail 2000, borne out of a political need to limit construction costs, is sometimes cited by German rail advocates and NIMBYs who assume that Switzerland does not build physical infrastructure. Since the 1980s, when investment in the Zurich S-Bahn and Rail 2000 began, Switzerland has built rail tunnels with gusto, and not just across the Alpine mountain passes for freight but also in and between cities to speed up passenger trains and create more capacity. Relative to population, Switzerland has built more rail tunnel per capita than Germany since the 1980s, let alone France, excluding the trans-Alpine base tunnels.

So overall, this is a program that’s very incremental and conservative when it comes to top speed (200 km/h, rarely 250), and moderately incremental when it comes to infrastructure but does build strategic bypasses, tunnels to allow trains to run as fast as necessary, and capacity improvements. But its planning paradigm and operations are both innovative – Rail 2000 was the first national plan to integrate infrastructure improvements into a knot system, and its successes have been exported into the Netherlands, Austria, and more slowly Germany.

Incrementalism in operations versus in infrastructure

The current trip times between New York and New Haven are 1:37 on intercity trains and 2:02 to 2:08 on commuter trains depending on how many stops they skip between Stamford and New Haven. The technical capability of modern trainsets with modern timetabling is 52 minutes on intercity trains and about 1:17 on commuter trains making the stopping patterns of today’s 2:08 trains.

This requires a single deviation from the right-of-way, at Shell Interlocking just south of New Rochelle, which deviation is calibrated not to damage a historic building close to the track and may not require any building demolitions at all; the main purpose of the Shell Interlocking project is to grade-separate the junction for more capacity, not to plow a right-of-way for fast trains. The impact of this single project on the schedule is hard to quantify but large, because it simplifies timetabling to the point that late trains on one line would not delay others on connecting lines; Switzerland pads the timetable 7%, whereas the TGV network (largely on dedicated tracks, thus relatively insulated from delays) pads 11-14%, and the much more exposed German intercity rail network pads 20-30%. The extent of timetable padding in and around New York is comparable to the German level or even worse; those two-hour trip times include what appears to be about 25 minutes of padding. The related LIRR has what appears to be 32% padding on its Main Line, as of nine years ago.

So in that sense, it’s possible to be fairly conservative with infrastructure, while upending operations completely through tighter scheduling and better trainsets. This should then be reinforced through upending planning completely through providing fewer train stopping patterns, in order to, again, reduce the dependence of different train types on one another.

Is this incremental? It doesn’t involve a lot of physical construction, so in a way, the answer is yes. The equivalent of Shell on the opposite side of New York, Hunter Interlocking, is on the slate of thoroughly incremental improvement projects that New Jersey Transit wishes to invest in, and while it has not been funded yet unfortunately, it is fairly likely to be funded soon.

But it also means throwing out 70 years of how American rail agencies have thought about operations. American agencies separate commuter and intercity rail into different classes of train with price differentiation, rather than letting passengers ride intercity trains within a large metropolitan area for the same price as commuter rail so long as they don’t book a seat. They don’t run repeating timetables all day, but instead aim to provide each suburban station direct service to city center with as few stops as possible at rush hour, with little concern for the off-peak. They certainly don’t integrate infrastructure with rolling stock or timetable decisions.

Incrementalism in different parts of the corridor

The answer to questions of incrementalism does not have to be the same across the country, or even across different parts of the same line. It matters whether the line is easy to bypass, how many passengers are affected, what the cost is, and so on.

Between New York and New Haven, it’s possible to reduce trip times by 7 minutes through various bypasses requiring new rights-of-way, including some tunneling and takings of a number of houses in the low hundreds, generally in wealthy areas. My estimate for how much these bypasses should cost is around $5 billion in total. Is it worth it? Maybe. But it’s not really necessary, and there are lower-hanging fruit elsewhere. (One bypass, west of Stamford, may be desirable – it would save maybe 100 seconds for maybe $500 million, and also provide more capacity on a more constrained section, whereas the other potential bypasses are east of Stamford, where there is much less commuter traffic.)

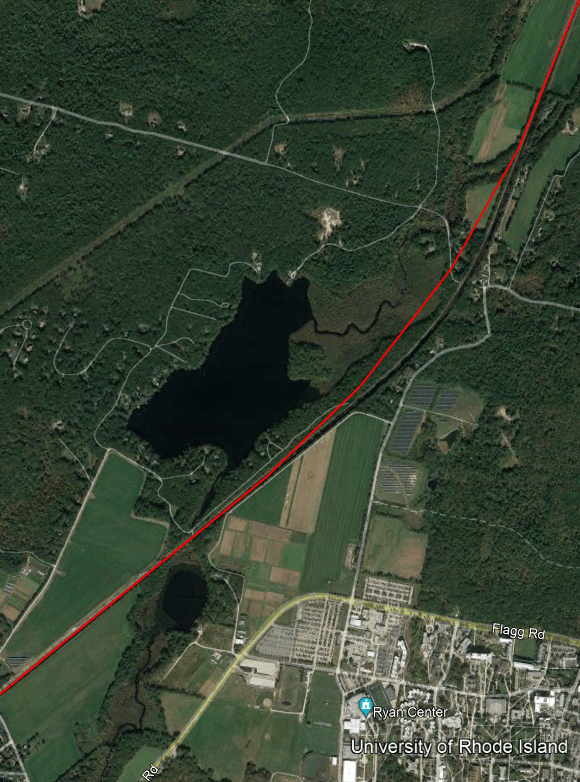

Between New Haven and Kingston, in contrast, the same $5 billion in bypass would permit a 320 km/h line to run continuously from just east of New Haven to not far south of Providence, with no tunnels, and limited takings. The difference in trip times is 25 minutes. Is that worth it? It should be – it’s a factor of around 1.2 in the New York-Boston trip times, so close to a factor of 1.5 in the projected ridership, which means its value is comparable to spending $15 billion on the difference between this service (including the $5 billion for the bypass) and not having any trains between New York and Boston at all.

South of New York, the more Devin and I look at the infrastructure, the more convinced I am that significant deviations from the right-of-way are unnecessary. The curves on the line are just not that significant, and there are long stretches in New Jersey where the current infrastructure is good and just needs cheap fixes to signals and electrification, not tunnels. Even very tight curves that should be fixed, like Frankford Junction in Philadelphia, are justifiable on the basis of a high benefit-cost ratio but are not make-or-break decisions; getting the timetabling integration right is much more important. This could, again, be construed to mean incrementalism, but we’re also looking at New York-Philadelphia trip times of around 46 minutes where the Acela takes about 1:09 today.

Overall, this program can be described as incremental in the sense of, over than 500 km between Boston and Philadelphia, only proposing 120 km of new right-of-way, plus a handful of junction fixes, switch rebuilds, and curve modifications; curve regradings within the right-of-way can be done by a track-laying machine cheaply and quickly. But it also assumes running trains without any of the many overly conservative assumptions of service in the United States, which used to be enshrined in FRA regulations but no longer are, concerning speed on curves, signaling, rolling stock quality, etc. If the trip time between Boston and Philadelphia is reduced by a factor of 1.8, how incremental is this program, exactly?

Incrementalism in marketing and fares

Finally, there are questions about business planning, marketing, segmentation, and fares. Here, the incremental option depends on what is the prior norm. In France, after market research in advance of the TGV showed that passengers expected the new trains to charge premium fares, SNCF heavily marketed the trains as TGV pour tous, promising to charge the same fares for 260 km/h trains as for 160 km/h ones. Since then, TGV fares have been revamped to resemble airline pricing with fare buckets, but the average fares remain low, around 0.11€/km. But international trains run by companies where SNCF has majority stake, namely Thalys and Eurostar, charge premium fares, going exclusively after the business travel market.

This, too, can be done as a break from the past or as a more incremental system. The American system on the Northeast Corridor is, frankly, bad: there are Acela and Regional trains, branded separately with separate tickets, the Regionals charging around twice as much as European intercity trains per km and the Acelas more than three times as much. Incrementalism means keeping this distinction – but then again, this distinction was not traditional and was instead created for the new Acela trains as they entered into service in 2000. (California High-Speed Rail promised even lower fares than the European average in the 2000s.)

Conclusion

There’s no single meaning to incrementalism in rail investment. Systems that are recognized for avoiding flashy infrastructure can be highly innovative in other ways, as is the case for Rail 2000. At the same time, such systems often do build extensive new infrastructure, just not in ways that makes for sleek maps of high-speed rail infrastructure in the mold of Japan, France, or now China.

What’s more, the question of how much to break from the past in infrastructure, operations, or even marketing depends on both what the past is and what the local geography is. The same planner could come to different conclusions for different lines, or different sections on the same line; it leads to bad planning if the assumption is that the entire line must be turned into 300+ km/h high-speed rail at once or none of it may be, instead of different sections having different solutions. Benefit-cost analyses need to rule the day, with prioritization based on centrally planned criteria of ridership and costs, rather than demands to be incremental or to be bold.

Venture Capital Firms Shift to Green Infrastructure

Several Bay Area major venture capital firms announce that they will shift their portfolios toward funding physical green infrastructure, including solar and wind power generation, utility lines, hydroelectric dams, environmental remediation projects for dams, and passenger and freight rail.

One founder of a firm in the public transit industry, speaking on condition of anonymity because the deal is still in process, points out that other VC investments have not been successful in the last 10-15 years. Cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and other blockchain technologies have not succeeded in transforming the finance sector; the Metaverse flopped; AI investments in driverless cars are still a long way from deployment, while LLMs are disappointing compared with expectations of artificial general intelligence. In contrast, the founder explains, there are great opportunities for new passenger rail lines and renewable and at places nuclear power.

Another founder points out the example of Brightline West and says that with upcoming reforms in permitting, pushed by many of the same VCs, it will be profitable to complete new domestic and international intercity rail lines between cities; a $15 billion investment in connecting Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland is underway.

On Sand Hill Roads, VC attitudes to the new investment are jubilant. One VC admits to never having heard much about public transit, but, after a three-day factfinding mission can tell you everything you could possibly want to know about the Singapore MRT. Other VCs say that Peter Thiel and Mark Zuckerberg are both especially interested in funding public transit initiatives after Elon Musk retweeted the X account TruthSeeker1488 saying that public transit is a conspiracy by international finance communists.

Local and Intercity Rail are Complements

An argument in my comments section is reminding me of a discussion by American transit advocates 15 years ago, I think by The Overhead Wire, about the tension between funding local transit and high-speed rail. I forget who it was – probably Jeff Wood himself – pointing out that the argument in 2008-9 about whether the priority was local transit or intercity rail didn’t make much sense. There are separate questions of how to allocate funding for intercity transportation and how to do the same for local transportation, and in both cases the same group of activists can push for a more favorable rail : car funding ratio. Jeff was talking about this in the sense of political activism; the purpose of this post is to explain the same concept from the point of view of public transportation connectivity and network effects. This is not an obvious observation, judging by how many people argue to the contrary – years ago I had a debate with Noah Smith about this, in which he said the US shouldn’t build high-speed rail like the Shinkansen before building urban rail systems like those of Japanese cities (see my side here and here).

I’ve written about related issues before, namely, in 2022 when I recommended that countries invest against type. For example, France with its TGV-centric investment strategy should invest in connecting regional lines, whereas Germany with its hourly regional train connections should invest in completing its high-speed rail network. It’s also worthwhile to reread what I wrote about Metcalfe’s law for high-speed rail in 2020, here and here. Metcalfe’s law is an abstract rule about how the value of a network with n nodes is proportional to , and Odlyzko-Tilly argue strongly that it is wrong and in fact the value is

; my post just looks at specific high-speed rail connections rather than trying to abstract it out, but the point is that in the presence of an initial network, even weaker-looking extensions can be worth it because of the connections to more nodes. Finally, this builds on what I said five days ago about subway-intercity rail connections.

The combined point is that whenever two forms of local, regional, or intercity public transportation connect, investments in one strengthen the case for investments in the other.

In some edge cases, those investments can even be the same thing. I’ve been arguing for maybe 12 years that MBTA electrification complements Northeast Corridor high-speed rail investment, because running fast electric multiple units (EMUs) on the Providence Line and its branches instead of slow diesel locomotive-hauled trains means intercity trains wouldn’t get stuck behind commuter trains. Similarly, I blogged five years ago, and have been doing much more serious analysis recently with Devin Wilkins, that coordinating commuter rail and intercity rail schedules on the New Haven Line would produce very large speed gains, on the order of 40-45 minutes, for both intercity and commuter trains.

But those are edge cases, borne of exceptionally poor management and operations by Amtrak and the commuter railroads in the Northeast. Usually, investments clearly are mostly about one thing and not another – building a subway line is not an intercity rail project, and building greenfield high-speed rail is not a local or regional rail project.

And yet, they remain complements. The time savings that better operations and maintenance can produce on the New Haven Line are also present on other commuter lines in New York, for example on the LIRR (see also here, here, and here); they don’t speed up intercity trains, but do mean that people originating in the suburbs have much faster effective trips to where they’d take intercity rail. The same is true for physical investments in concrete: the North-South Rail Link in Boston and a Penn Station-Grand Central connection in New York both make it easier for passengers to connect to intercity trains, in addition to benefits for local and regional travel, and conversely, fast intercity trains strengthen the case for these two projects since they’d connect passengers to better intercity service.

Concretely, let’s take two New York-area commuter lines, of which one will definitely never have to interface with intercity rail and one probably will not either. The definitely line is the Morristown Line: right now it enters New York via the same North River Tunnels as all other trains from points west, intercity or regional, but the plan for the Gateway Tunnel is to segregate service so that the Morris and Essex Lines use the new tunnel and the Northeast Corridor intercity and commuter trains use the old tunnel, and so in the future they are not planned to interact. The probably line is the LIRR Main Line, which currently doesn’t interface with intercity trains as I explain in my post about the LIRR and Northeast Corridor, and which should keep not interfacing, but there are Amtrak plans to send a few daily intercities onto it.

Currently, the trip time from Morristown to New York is around 1:09 off-peak, with some peak-only express trains doing it in 1:01. With better operations and maintenance, it should take 0:47. The upshot is that passengers traveling from Morristown to Boston today have to do the trip in 1:09 plus 3:42-3:49 (Acela) or 4:15-4:35 (Regional). The commuter rail improvements, which other than Gateway and about one unfunded tie-in do not involve significant investment in concrete, turn the 4:51 plus transfer time trip to 4:29 plus transfer time – say 5 hours with the transfer, since the intercities run hourly and the transfers are untimed and, given the number of different branches coming in from New Jersey, cannot be timed. High-speed rail, say doing New York-Boston in 2 hours flat (which involves an I-95 bypass from New Haven to Kingston but no other significant deviations from the right-of-way), would make it 2:47 with a transfer time capped at 10 minutes, so maximum 2:57. In effect, these two investments combine to give people from Morristown an effective 41% reduction in trip time to Boston, which increases trip generation by a factor of 2.87. Of course, far more people from Morristown are interested in traveling to New York than to Boston, but the point is that in the presence of cheap interventions to rationalize and speed up commuter rail, intercity rail looks better.

The same is true from the other direction, from the LIRR Main Line. The two busiest suburban stations in the United States are on 2000s and 10s numbers Ronkonkoma and Hicksville, each with about 10,000 weekday boardings. Ronkonkoma-Penn Station is 1:18 and Hicksville-Penn Station is 0:42 off-peak; a few peak express trains per day do the trip a few minutes faster from Ronkonkoma by skipping Hicksville, but the fastest looks like 1:15. If the schedule is rationalized, Ronkonkoma is about 0:57 from New York and Hicksville 0:31, on trains making more stops than today. I don’t have to-the-minute New York-Washington schedules with high-speed rail yet, but I suspect 1:50 plus or minus 10 minutes is about right, down from 2:53-3:01 on the Acela and 3:17-3:38 on the Regional. So the current timetable for Ronkonkoma-Washington is, with a half-hour transfer time, around 4:45 today and 2:57 in the future, which is a 38% reduction in time and a factor of 2.59 increase in the propensity to travel. From Hicksville, the corresponding reduction is from 4:09 to 2:31, a 39% reduction and a factor of 2.72 increase in trip generation. Again, Long Islanders are far more interested in traveling to Manhattan than to Washington, but a factor of 2.59-2.72 increase in trip generation is nothing to scoff at.

The issue here is that once the cheap upgrades are done, the expensive ones start making more sense – and this is true for both intercity and regional trains. The New York-Boston timetable assumes an I-95 bypass between New Haven and Kingston, saving trains around 24 minutes, at a cost of maybe $5 billion; those 24 minutes matter more when they cut the trip time from 2:24 to 2:00 than when the current trip time is about 3:45 and the capacity on the line is so limited any increase in underlying demand has to go to higher fares, not more throughput. For suburban travelers, the gains are smaller, but still, going from 5:00 to 4:36 matters less than going from 3:21 to 2:57.

Conversely, the expensive upgrades for regional trains – by which I mean multi-billion dollars tunnels, not $300 million junction grade separations like Hunter or the few tens of millions of dollars on upgrading the junction and railyard at Summit – work better in a better-operated system. Electronics before concrete, not instead of concrete – in fact, good operations (i.e. good electronics) create more demand for megaprojects.

At no point are these really in competition, not just because flashy commuter rail projects complement intercity rail through mutual feeding, but also because the benefits for non-connecting passengers are so different that different funding mechanisms make sense. The North-South Rail Link has some benefits to intercity travel, as part of the same program with high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor, and as such, it could be studied as part of the same program, if there is enough money in the budget for it, which there is not. Conversely, it has very strong local benefits, ideal for a funding partnership between the federal government and Massachusetts; similarly, New York commuter rail improvements are ideal for a funding partnership between the federal government, New York State, New Jersey, and very occasionally Connecticut.

In contrast, intercity rail benefits people who are far away from where construction is done: extensive bypasses built in Connecticut would create a small number of jobs in Connecticut temporarily, but the bigger benefits would accrue not just to residents of the state (through better New Haven-Boston and perhaps New Haven-New York trip times) but mostly to residents of neighboring states traveling through Connecticut. This is why there’s generally more national coordination of intercity rail planning than of regional rail planning: the German federal government, too, partly funds S-Bahn projects in major German cities, but isn’t involved in planning S21 S15 or the second S-Bahn trunk in Munich, whereas it is very involved in decisions on building high-speed rail lines. The situation in France is similar – the state is involved in decisions on LGVs and on Parisian transit but not on provincial transit, though it helps fund the latter; despite the similarity in the broad outlines of the funding structure, the outcomes are different, which should mean that the differences between France and Germany do not boil down to funding mechanisms or to inherent competition between intercity rail funds and regional rail funds.

Subway-Intercity Rail Connections

Something Onux said in comments on yesterday’s post, about connecting Brooklyn to intercity rail, got me thinking more about how metro lines and intercity rail can connect better. This matters for mature cities that build little infrastructure like New York or Berlin, but also for developing-world cities with large construction programs ahead of them. For the most part, a better subway system is automatically one that can also serve the train station better – the train station is usually an important destination for urban travel and therefore, usually the same things that make for a stronger subway system also make for better subway-intercity rail connections.

Subways and commuter trains

Like gender, transit mode is a spectrum. There are extensive systems that are clearly metro and ones that are clearly commuter rail, but also things in between, like the RER A, and by this schema, the Tokyo and Seoul subways are fairly modequeer.

The scope of this post is generally pure subway systems – even the most metro-like commuter lines, like the RER A and the Berlin S-Bahn, use mainline rail rights-of-way and usually naturally come to connect with intercity train stations. Of note, RER A planning, as soon as SNCF got involved, was modified to ensure the line would connect with Gare de Lyon and Gare Saint-Lazare; previous RATP-only plans had the line serving Bastille and not Gare de Lyon, and Concorde and not Auber. So here, the first rule is that metro (and metro-like commuter rail) plans should, when possible, be modified to have the lines serve mainline train stations.

Which train stations?

A city designing a subway system should ensure to serve the train station. This involves nontrivial questions about which train stations exactly.

On the one hand, opening more train stations allows for more opportunities for metro connections. In Boston, all intercity trains serve South Station and Back Bay, with connections to the Red and Orange Lines respectively. In Berlin, north-south intercity trains call not just at Hauptbahnhof, which connects to the Stadtbahn and (since 2020) U5, but also Gesundbrunnen and Südkreuz, which connect to the northern and southern legs of the Ringbahn and to the North-South Tunnel; Gesunbrunnen also has a U8 connection. In contrast, trains into Paris only call at the main terminal, and intercity trains in New York only stop at Penn Station.

On the other hand, extra stations like Back Bay and delay trains. The questions that need to be answered when deciding whether to add stations on an intercity line are,

- How constructible is the new station? In New York, this question rules out additional stops; some of the through-running plans involve a Penn Station-Grand Central connection to be used by intercity trains, but there are other reasons to keep it commuter rail-only (for example, it would make track-sharing on the Harlem Line even harder).

- How fast is the line around the new station? More stations are acceptable in already slow zones (reducing the stop penalty), on lines where most trips take a long time (reducing the impact of a given stop penalty). Back Bay and Südkreuz are in slow areas; Gesundbrunnen is north of Hauptbahnhof where nearly passengers are going south of Berlin, so it’s free from the perspective of passengers’ time.

- How valuable are the connections? This depends on factors like the ease of internal subway transfers, but mostly on which subway lines the line can connect to. Parisian train terminals should in theory get subsidiary stations because internal Métro transfers are so annoying, but there’s not much to connect to – just the M2/M6 ring, generally with no stations over the tracks.

Subway operations

In general, most things that improve subway operations in general also improve connectivity to the train station. For example, in New York, speeding up the trains would be noticeable enough to induce more ridership for all trips, including access to Penn Station; this could be done through reducing flagging restrictions (which we briefly mention at ETA), among other things. The same is true of reliability, frequency, and other common demands of transit advocates.

Also in New York, deinterlining would generally be an unalloyed good for Penn Station-bound passengers. The reason is that the north-south trunk lines in Manhattan, other than the 4/5/6, either serve Penn Station or get to Herald Square one long block away. The most critical place to deinterline is at DeKalb Avenue in Brooklyn, where the B/D/N/Q switch from a pattern in which the B and D share one track pair and the N and Q share another to one in which the B and Q share a pair and the D and N share a pair; the current situation is so delicate that trains are delayed two minutes just at this junction. The B/D and N/Q trunk lines in Manhattan are generally very close to each other, so that the drawback of deinterlining is reduced, but when it comes to serving Penn Station, the drawback is entirely eliminated, since both lines serve Herald Square.

If anything, it’s faster to list areas where subway service quality and subway service quality to the train station specifically are not the same than to list areas where they are:

- The train station is in city center, and so circumferential transit, generally important, doesn’t generally connect to the station; exceptions like the Ringbahn exist but are uncommon.

- If too many lines connect to the one station, then the station may become overloaded. Three lines are probably fine – Stockholm has all three T-bana lines serving T-Centralen, adjacent to the mainline Stockholm Central Station, and there is considerable but not dangerous crowding. But beyond that, metro networks need to start spreading out.

- Some American Sunbelt cities if anything have a subway connection to the train station, for example Los Angeles, without having good service in general. In Los Angeles, the one heavy rail trunk connects to Union Station and so does one branch of the Regional Connector; the city’s problems with subway-intercity rail connections are that it doesn’t really have a subway and that it doesn’t really have intercity rail either.

Intercity Trains and Long Island

Amtrak wants to extend three daily Northeast Corridor trains to Long Island. It’s a bad idea – for one, if the timetable can accommodate three daily trains, it can accommodate an hourly train – but beyond the frequency point, this is for fairly deep reasons, and it took me years of studying timetabling on the corridor to understand why. In short, the timetabling introduces too many points of failure, and meanwhile, the alternative of sending all trains that arrive in New York from Philadelphia and Washington onward to New Haven is appealing. To be clear, there are benefits to the Long Island routing, they’re just smaller than the operational costs; there’s a reason this post is notably not tagged “incompetence.”

How to connect the Northeast Corridor with Long Island

The Northeast Corridor has asymmetric demand on its two halves. North of New York, it connects the city with Boston. But south of New York, it connects to both Philadelphia and Washington. As a result, the line can always expect to have more traffic south of New York than north of it; today, this difference is magnified by the lower average speed of the northern half, due to the slowness of the line in Connecticut. Today, many trains terminate in New York and don’t run farther north; in the last 20 years, Amtrak has also gone back and forth on whether some trains should divert north at New Haven and run to Springfield or whether such service should only be provided with shuttle trains with a timed connection. Extending service to Long Island is one way to resolve the asymmetry of demand.

Such an extension would stop at the major stattions on the LIRR Main Line. The most important is Jamaica, with a connection to JFK; then, in the suburbs, it would be interesting to stop at least at Mineola and Hicksville and probably also go as far as Ronkonkoma, the end of the line depicted on the map. Amtrak’s proposed service makes exactly these stops plus one, Deer Park between Hicksville and Ronkonkoma.

The entire Main Line is electrified, but with third rail, not catenary. The trains for it therefore would need to be dual-voltage. This requires a dedicated fleet, but it’s not too hard to procure – it’s easier to go from AC to DC than in the opposite direction, and Amtrak and the LIRR already have dual-mode diesel locomotives with third rail shoes, so they could ask for shoes on catenary electric locomotives (or on EMUs).

The main benefit of doing this, as opposed to short-turning surplus Northeast Corridor trains in New York, is that it provides direct service to Long Island. In theory, this provides access to the 2.9 million people living on Long Island. In practice, the shed is somewhat smaller, because people living near LIRR branches that are not the Main Line would be connecting by train anyway and then the difference between connecting at Jamaica and connecting at Penn Station is not material; that said, Ronkonkoma has a large parking lot accessible from all of Suffolk County, and between it and significant parts of Nassau County near the Main Line, this is still 2 million people. There aren’t many destinations on Long Island, which has atypically little job sprawl for an American suburb, but 2 million originating passengers plus people boarding at Jamaica plus people going to Jamaica for JFK is a significant benefit. (How significant I can’t tell you – the tools I have for ridership estimation aren’t granular enough to detect the LIRR-Amtrak transfer penalty at Penn Station.)

My early Northeast Corridor ideas did include such service, for the above reasons. However, there are two serious drawbacks, detailed below.

Timetabling considerations

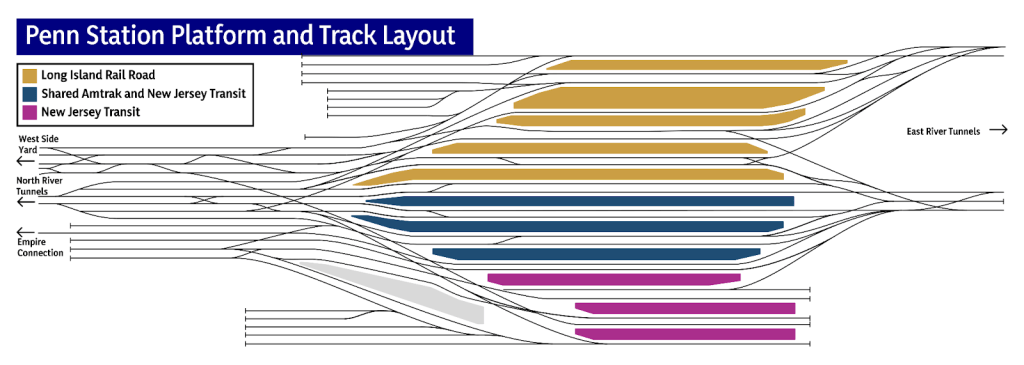

Under current plans, there is little interaction between the LIRR and the Northeast Corridor. There are two separate routes into Penn Station from the east, one via 32nd Street (“southern tunnels”) and one via 33rd (“northern tunnels”), each a two-track line with one track in each direction. The North River Tunnels, connecting Penn Station with New Jersey and the rest of the United States, face the southern tunnels; the Gateway tunnels under construction to double trans-Hudson capacity are not planned to pair with the northern tunnels, but rather to connect to stub-end tracks facing 31st Street. For this reason, Amtrak always or almost always enters Penn Station from the east using the southern tunnels; the northern tunnels do have some station tracks that connect to them and still allow through-service to the west, but the moves through the station interlocking are more complex and more constrained.

As seen on the map, east of Penn Station, the Northeast Corridor is to the north of the LIRR. Thus, Amtrak has to transition from being south of the LIRR to being north of it. This used to be done at-grade, with conflict with same-direction trains (but not opposite-direction ones); it has since been grade-separated, at excessive cost. With much LIRR service diverted to Grand Central via the East Side Access tunnel, current traffic can be divided so that LIRR Main Line service exclusively uses the northern tunnels and Northeast Corridor (Amtrak or commuter rail under the soon to open Penn Station Access project) service exclusively uses the southern tunnels; the one LIRR branch not going through Jamaica, the Port Washington Branch, can use the southern tunnels as if it is a Penn Station Access branch. This is not too far from how current service is organized anyway, with the LIRR preferring the northern (high-numbered) tracks at Penn Station, Amtrak the middle ones, and New Jersey Transit the southern ones with the stub end:

The status quo, including any modification thereto that keeps the LIRR (except the Port Washington Branch) separate from the Northeast Corridor, means that all timetabling complexity on the LIRR is localized to the LIRR. LIRR timetabling has to deal with all of the following issues today:

- There are many different branches, all of which want to go to Manhattan rather than to Brooklyn, and to a large extent they also want to go on the express tracks between Jamaica and Manhattan rather than the local tracks.

- There are two Manhattan terminals and no place to transfer between trains to different ones except Jamaica; an infill station at Sunnyside Yards, permitting trains from the LIRR going to Grand Central to exchange passengers with Penn Station Access trains, would be helpful, but does not currently exist.

- The outer Port Jefferson Branch is unelectrified and single-track and yet has fairly high ridership, so that isolating it with shuttle trains is infeasible except in the extreme short run pending electrification.

- All junctions east of Jamaica are flat.

- The Main Line has three tracks east of Floral Park, the third recently opened at very high cost, purely for peak-direction express trains, but cannot easily schedule express trains in both directions.

There are solutions to all of these problems, involving timetable simplification, reduction of express patterns with time saved through much reduced schedule padding, and targeted infrastructure interventions such as electrifying and double-tracking the entire Port Jefferson Branch.

However, Amtrak service throws multiple wrenches in this system. First, it requires a vigorous all-day express service between New York and Hicksville if not Ronkonkoma. Between Floral Park and Hicksville, there are three tracks. Right now the local demand is weak, but this is only because there is little local service, and instead the schedule encourages passengers to drive to Hicksville or Mineola and park there. Any stable timetable has to provide much stronger local service, and this means express trains have to awkwardly use the middle track as a single track. This isn’t impossible – it’s about 15 km of fast tracks with only one intermediate station, Mineola – but it’s constraining. Then the constraint propagates east of Hicksville, where there are only two tracks, and so those express trains have to share tracks with the locals and be timetabled not to conflict.

And second, all these additional conflict points would be transmitted to the entire Northeast Corridor. A delay in Deer Park would propagate to Philadelphia and Washington. Even without delays, the timetabling of the trains in New Jersey would be affected by constraints on Long Island; then the New Jersey timetabling constraints would be transmitted east to Connecticut and Massachusetts. All of this is doable, but at the price of worse schedule padding. I suspect that this is why the proposed Amtrak trip time for New York-Ronkonkoma is 1:25, where off-peak LIRR trains do it in 1:18 making all eight local stops between Ronkonkoma and Hicksville, Mineola, Jamaica, and Woodside. With low padding, which can only be done with more separated out timetables, they could do it in 1:08, making four more net stops.

Trains to New Haven

The other reason I’ve come to believe Northeast Corridor trains shouldn’t go to Jamaica and Long Island is that more trains need to go to Stamford and New Haven. This is for a number of different reasons.

The impact of higher average speed

The higher the average speed of the train, the more significant Boston-Philadelphia and Boston-Washington ridership is. This, in turn, reduces the difference in ridership north and south of New York somewhat, to the point that closer to one train in three doesn’t need to go to Boston than one train in two.

Springfield

Hartford and Springfield can expect significant ridership to New York if there is better service. Right now the line is unelectrified and runs haphazard schedules, but it could be electrified and trains could run through; moreover, any improvement to the New York-Boston line automatically also means New York-Springfield trains get faster, producing more ridership.

New Haven-New York trips

If we break my gravity model of ridership not into larger combined statistical areas but into smaller metropolitan statistical areas, separating out New Haven and Stamford from New York, then we see significant trips between Connecticut and New York. The model, which is purely intercity, at this point projects only 15% less traffic density in the Stamford-New York section than in the New York-Trenton section, counting the impact of Springfield and higher average speed as well.

Commutes from north of New York

There is some reason to believe that there will be much more ridership into New York from the nearby points – New Haven, Stamford, Newark, Trenton (if it has a stop), and Philadelphia – than the model predicts. The model doesn’t take commute trips into account; thus, it projects about 7.78 million annual trips between New York and either Stamford or New Haven, where in fact the New Haven Line was getting 125,000 weekday passengers and 39 million annual passengers in the 2010s, mostly from Connecticut and not Westchester County suburbs. Commute trips, in turn, accrete fairly symmetrically around the main city, reducing the difference in ridership between New York-Philadelphia and New York-New Haven, even though Philadelphia is the much larger city.

Combining everything

With largely symmetric ridership around New York in the core, it’s best to schedule the Northeast Corridor with the same number of trains immediately north and immediately south of it. At New Haven, trains should branch. The gravity model projects a 3:1 ratio between the ridership to Boston and to Springfield. Thus, if there are eight trains per hour between New Haven and Washington, then six should go to Boston and two to Springfield; this is not even that aggressive of an assumption, it’s just hard to timetable without additional bypasses. If there are six trains per hour south of New Haven, which is more delicate to timetable but can be done with much less concrete, then two should still go to Springfield, and they’ll be less full but over this short a section it’s probably worth it, given how important frequency is (hourly vs. half-hourly) for trips that are on the order of an hour and a half to New York.

Northeast Corridor Travel Markets and Fares

I’m optimistic about the ability of fast trains on the Northeast Corridor to generate healthy ridership at all times of day. This is not just a statement about the overall size of the travel market, which is naturally large since the line connects three pretty big metro areas and one very big one. Rather, it’s also a statement about how the various travel markets on the corridor fit atypically well together, creating demand that is fairly consistent throughout the day, permitting trains with a fixed all-day schedule to still have high occupancy – but only if the trains are fast. Today, we’re barely seeing glimpses of that, and instead there are prominent peak times on the corridor, due to a combination of fares and slowness.

Who travels by high-speed rail?

High-speed intercity rail can expect to fill all of the following travel markets:

- Business trips

- Tourism and other recreational trips (including visits to friends and family)

- Commute trips

The key here is that the first two kinds of trips can be either day trips or multiday trips. I day-tripped to the Joint Mathematics Meeting in 2012 when I lived in Providence and the conference was in Boston, about an hour away by commuter rail, but when there was an AMS sectional conference in Worcester in 2011 (from which my blog’s name comes – I found Worcester unwalkable and uploaded an album to Facebook with the name “pedestrian observations from Worcester”) I took trains. I probably would have taken trains from New York to Worcester for the weekend rather than day-tripped even if they were fast – fast trains would still be doing it in around 2:30, which isn’t a comfortable day trip for work.

Non-work trips are the same – they can be day trips or not. Usually recreational day trips are uncommon because train travel is expensive, especially at current Amtrak pricing – the Regional costs twice as much per passenger-km as the TGV and ICE, and the Acela costs three times as much. But there are some corner cases: I moved to Providence with a combination of day trips (including two to view apartments and one to pick up keys) and multiday trips. Then, at commuter rail range, there are more recreational day trips – I’ve both done this and invited others to do so on Boston-Providence and New York-New Haven. Recreational rail trips, regardless of length, are more often taken by individuals and not groups, since car travel costs are flat in the number of passengers and train costs are linear, but even groups sometimes ride trains.

We can turn this into a two-dimensional table of the various kinds of trips, classified by purpose and whether they are day trips or multiday trips:

| Purpose | Day trip | Multiday trip |

| Business | Work trips between city centers, usually in professional services or other high-value added firms, such as lawyers traveling between New York and Washington, or tech workers between New York and Boston; academic seminar trips | Conference trips, more intensive work trips often involving an entire team, and likely all business trips between Boston and Washington or Boston and Philadelphia |

| Tourism | Trips to a specific amenity, which could be urban, such as going to a specific museum in New York or Washington or walking around a historic town like Plymouth, or not, such as taking the train to connect to a beach or hiking trail | Long trips to a specific city or region, stringing many amenities at once |

| Other non-work | College visits, especially close to the train stations; meetings with friends within short range (such as New York-Philadelphia); advocacy groups meeting on topics of interest; apartment viewings; some trips to concerts and sports games | Visits to friends and family; some moving trips; some trips to concerts and sports games |

| Commute | Long-range commutes | — |

Day trips and different peaks

The different trips detailed in the above table peak at different times. The commute trips peak at the usual commute times: into the big cities at 9 in the morning, out of them at 5 in the afternoon. But the rest have different peaks.

In particular, multiday tourism trips peak on weekends – out on Friday, back on Sunday night – while multiday business trips peak during the week. This is consistent enough that airlines use this to discriminate in prices between different travelers: trips are cheaper if booked as roundtrips over Saturday nights, because such trips are likely to be taken by more price-sensitive leisure travelers rather than by less price-sensitive business travelers.

Nonetheless, even with this combination of patterns, the most common pattern I am aware of on intercity rail, at the very least on the Northeast Corridor and on the TGV network, is that the trains are busier during the weekend leisure peak than during the weekday business peaks (except during commute times). Regardless of the distribution of business and leisure trips, leisure trips have a narrow peak, leaving within a window just a few hours long on Friday, whereas business trips may occur on any combination of weekdays; for this reason, leisure-dominated railroads, such as any future service to Las Vegas, are likely to have to deal with very prominent peaking, reducing their efficiency (capacity has to be built for all hours of the week).

But then day trips introduce additional trip types. The leisure day trip is unlikely to be undertaken on a Friday – the traveler who is free during the weekend but not the week might as well travel for the entire weekend. Rather, it’s either a Saturday or Sunday trip, or a weekday trip for the traveler who can take a day off, is not in the workforce, or is in the region on a leisure trip from outside the Northeast and is stringing multiple Northeastern cities on one trip. This day trip then misses the leisure peak, and usually also misses the commuter peak.

The business day trip is likely to be undertaken during the week, probably outside the peak commute time – rather, it’s a trip internal to the workday, to be taken midday and in the afternoon. It may overlap the afternoon peak somewhat – the jobs that I think are likeliest to take such trips, including law, academia, and tech, typically begin and end their workdays somewhat later than 9-to-5 – but the worst peak crowding is usually in the morning and not the afternoon, since the morning peak is narrower, in the same manner that the Friday afternoon peak for leisure travel is narrower than other peaks.

The day trips are rare today; I’ve done them even at the New York-Providence range, but only for the purpose of moving to Providence, and other times I visited New York or even New Haven for a few days at a time. However, the possibility of getting between New York and Providence in 1:20 changes everything. The upshot is that high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor is certain to massively boost demand on all kinds of trips, but stands to disproportionately increase the demand for non-peak travel, making train capacity more efficient – running the same service all day would incur less waste in seat-km.

The issue of fares

All of this analysis depends on fares. These are not too relevant to business trips, and I suspect even to business day trips – if you’re the kind of person who could conceivably day trip between New York and Washington on a train taking 1:45 each way to (say) meet with congressional staffers, you’re probably doing this even if the fares are as high as they are today. But they are very relevant to all other trips.

In particular, non-work day trips are most likely not occurring during any regular peak travel time. Thus, the fare system should not attempt to discourage such trips. Even commute trips, with their usual peak, can be folded into this system, since pure intercity trips peak outside the morning commute period.

The upshot is that it is likely good to sell intercity and commuter rail tickets between the same pair of stations for the same fare. This means that people traveling on sections currently served by both intercity and commuter rail, like Boston-Providence, New York-New Haven, New York-Trenton, and Baltimore-Washington, would all be taking the faster intercity trains. This is not a problem from the point of view of capacity – intercity trains are longer (they serve fewer stations, so the few stations on the corridor not long enough for 16-car trains can be lengthened), and, again, the travel peaks for multiday trips are distinct from the commute peak. Commuter trains on the corridor would be serving more local trips, and help feed the intercity trains, with through-ticketing and fare integration throughout.

New York-New Haven Trains in an Hour

Devin Wilkins and I are still working on coming up with a coordinated timetable on the Northeast Corridor, north to south. Devin just shared with me the code she was running on both routes from New Haven to New York – to Grand Central and to Penn Station – and, taking into account the quality of the right-of-way and tunnels but not timetable padding and conservative curve speeds – it looks like intercity trains would do it in about an hour. The current code produces around 57 minutes with 7% timetable pad if I’m getting the Penn Station throat and tunnel slowdowns right – but that’s an if; but at this point, I’m confident about the figure of “about an hour” on the current right-of-way.

I bring this up to give updates on how the more accurate coding is changing the timetable compared to previous estimates, but also to talk about what this means for future investment priorities.

First, the curve radii I was assuming in posts I was writing last decade were consistently too optimistic. I wrote three months ago about how even within the highest speed zone in southern Rhode Island, there’s a curve with radius 1,746 meters (1 degree in American parlance), which corresponds to about 215 km/h with aggressive cant and cant deficiency. At this point we’ve found numbers coming straight from Amtrak, Metro-North, and MBTA, letting us cobble together speed zones for the entire system.

But second, conversely, I was being too conservative with how I was setting speed zones. My principle was that the tightest curve on a section sets the entire speed limit; when writing commuter rail timetables, I would usually have each interstation segment be a uniform speed zone, varying from this practice only when the interstation was atypically long and had long straight sections with a tight curve between them. When writing intercity timetables, I’d simplify by having the typical curves on a line set the speed limit and then have a handful of lower speed limits for tighter curves; for example, most curves on the New Haven Line are 873 meters, permitting 153 km/h with aggressive high-speed rail cant and cant deficiency, and 157 km/h with aggressive limits for slower trains, which can run at slightly higher cant deficiency, but those sections are punctuated by some sharper curves with lower limits. Devin, using better code than me, instead lets a train accelerate to higher speed on straight sections and then decelerate as soon as it needs to. Usually such aggressive driving is not preferred, and is used only when recovering from delays – but the timetable is already padded somewhat, so it might as well be padded relative to the fastest technical speed.

The upshot of all of this is that the speed gains from just being able to run at the maximum speed permitted by the right-of-way are massive. The trip time today is 1:37 on the fastest trains between New York and New Haven. Commuter trains take 2:10, making all stops from New Haven to Stamford and then running nonstop between Stamford and Manhattan; in our model, with a top speed of 150 km/h, high-performance regional trains like the FLIRT, Talent 3, or Mireo should do the trip in about 1:15-1:20, and while we didn’t model the current rolling stock, my suspicion is that it should be around six minutes longer. The small difference in trip time is partly because Penn Station’s approach is a few kilometers longer than Grand Central’s and the curves in Queens and on the Hell Gate Bridge are tight.

What this means is that the highest priority should be getting trains down to this speed. In the Swiss electronics-before-concrete schema, the benefits of electronics on the Northeast Corridor are massive; concrete has considerable benefits as well, especially on sections where the current right-of-way constrains not just speed but also reliability and capacity, like New Haven-Kingston, but the benefits of electronics are so large that it’s imperative to make targeted investments to allow for such clean schedules.

Those investments do include concrete, to be clear. But it’s concrete that aims to make the trains flow more smoothly, in support of a repetitive schedule with few variations in train stopping patterns, so that the trains can be timetabled in advance not to conflict. At this point, I believe that grade-separating the interlocking at New Rochelle, popularly called Shell Interlocking and technically called CP 216, is essential and must be prioritized over anything else between the city limits of New York and New Haven Union Station. Currently, there’s very high peak traffic through the interlocking, with a flat junction between trains to Penn Station and trains to Grand Central.

On the electronics side, the timetables must become more regular. There are currently 20 peak trains per hour on the New Haven Line into Grand Central; of those, four go to branches and 16 are on the main line, and among the 16, there are 13 different stopping patterns, on top of the intercity trains. It is not possible to timetable so many different trains on a complex system and be sure that everything is conflict-free, and as a result, delays abound, to which the response is to pad the schedules. But since the padded schedules still have conflicts, there is a ratchet of slowdowns and padding, to the point that a delayed train can recover 20 minutes on less than the entire line. Instead, every train should either be a local train to Stamford or an express train beyond Stamford, and there should only be a single express pattern on the inner line, which today is nonstop between Harlem and Stamford and in the future should include a stop at New Rochelle; this means that, not taking intercity trains into account, the main line should have at most four stopping patterns (local vs. express, and Penn Station vs. Grand Central), and probably just three, since express commuter trains should be going to Grand Central and not Penn Station, as passengers from Stamford to Penn Station can just ride intercity trains.

Also on the electronics side, the way the line is maintained currently is inefficient to an extent measured in orders of magnitude and not factors or percents. Track inspection is manual; Metro-North finally bought a track geometry machine but uses it extremely unproductively, with one report saying it gets one tenth as much work done as intended. Normally these machines can do about a track-mile in an overnight work window, which means the entire four-track line can be regraded and fixed in less than a year of overnights, but they apparently can’t achieve that. Whatever they’re doing isn’t working; the annual spending on track renewal in Connecticut is what Germany spends on once-in-a-generation renewal. The endless renewal work includes a plethora of ever-shifting slow zones, and at no point is the entire system from New York to New Haven clear for trains, even on weekdays. The excessively complex schedule, on tracks that constantly shift due to segment-by-segment daytime repairs, is turning a trip that should be doable on current rolling stock in perhaps 1:23 into one that takes 2:10.

The billions of dollars in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that are dedicated to the Northeast Corridor and have not yet been spent can reduce trip times further. But the baseline should be that the bucket of money is a few hundreds of millions smaller and the base case trip time from New York to New Haven is an hour and not 1:37; this is what the system should be compared with.

Eurostar Security Theater and French Station Size

Jon Worth has been doing a lot of good work lately pouring cold water on various press releases of new rail service in Europe. Yesterday he wrote a long post, reacting to some German rail discourse about the possibility of Eurostar service between London and Germany; he explained the difficulties of connecting Eurostar to new cities, discussing track and station capacity, signaling, and rolling stock.

Jon, whose background is in EU politics, wastes no time in identifying the ultimate problem: the UK demands passport controls, and this demand is unlikely to be waived in the near future due to concerns over Brexit and the need to have visible border control theater. In turn, the passport control and the accompanying security theater (not strictly required, but the UK insists for Channel Tunnel security) mean that boarding trains is a slow process since platforms must be kept sterile; thus, a Eurostar station requires dedicated platforms, and if it has significant rail traffic then it requires many of them, with low throughput per track. This particularly impacts the prospects of Eurostar service to Germany, because it would go via Belgium and Cologne, which has far from enough platforms for this operation.

What I’d like to add to this analysis is that Eurostar made a choice to engage in such controlled operations in the 1990s. The politics of Brexit can explain why there’s no reform that is acceptable to the British political system now; it cannot explain why this was chosen in the 1990s. The norm in Europe before Schengen was that border control officers would perform on-board checks while the train traveled between the last station in the origin country and the first station in the destination country; long nonstop trains between Paris and London or even Lille and London are ideal for such a system. Britain insists on the current system of border control before boarding because this way it can deny entry to people who otherwise would enjoy non-refoulement protections – but in the 2000s the politics in Britain was not significantly more anti-immigration than in, for example, Germany, or France.

Rather, the issue is that Britain insisted on some nebulous notion of separateness, and this interacted poorly with train station design in France compared with in Germany. Parisian train stations are huge, and have a large number of terminating tracks. Dedicating a few terminal tracks to sterile operations is possible at Gare du Nord, and would be possible at other Parisian terminals like Gare de Lyon if they pointed in the direction of a place that demanded them. SNCF has conceived of its operations, especially internationally, as airline-like, and this contributed to complacency about how the train stations are being treated like airports.

Germany developed different (and better) ways of conceiving of train operations. More to the point, Germany doesn’t really have Paris’s terminals with their surplus of tracks, except for Frankfurt and Munich. Cologne, the easiest place to get to London from, doesn’t have enough tracks for sterile operations. This is fine, because German domestic trains do not imitate airlines, even where there is room (instead, the surplus of tracks is used for timed connections between regional trains); this also cascades to international trains connecting to Germany, whether from countries that have more punctual rail networks like Switzerland or from countries that work by a completely different paradigm like Belgium or France.

And now Eurostar politically froze a system that was only workable at low throughput, at a handful of stations with more room for sterile operations than is typical. The system is still below its ridership projections from before opening; it was supposed to be part of a broader international rail network, but that never materialized, because of the burden of security theater, the high fares, and the indifference of Belgium to extending high-speed rail so that it would be useful for international travelers (the average speeds between Brussels-Midi and the German border are within the upper end of the range for upgraded classical lines, even though HSL 2 and 3 are new high-speed lines).

And now, with the knowledge of the 2010s, it’s clear that any future expansion of Eurostar requires forgoing the airline-like paradigm that led SNCF to stagnation in the same decade. This clashes with British political theater now, but there’s no other way forward.

And this even affects domestic British rail planning. London planners are fixated on Paris as their main comparison. This way, they are certain trains must turn slowly at city terminals, requiring additional tracks at Euston and other stations that are or until recently were part of High Speed 2, at a total cost of several billion pounds. In Germany and the Netherlands (at Utrecht) trains can move faster, down to turns of seven to eight minutes on German regional trains and four to five minutes on intercity trains pinching at terminal stations like Frankfurt. But planners in large cities look down on smaller cities; it’s no different from how planners in New York assume that because New York is bigger than Stockholm, Second Avenue Subway’s stations have higher ridership than the stations of Citybanan (in fact, Citybanan’s two stations, located in city center, are significantly busier).

This way, a particular feature of historic Parisian stations – they have a lot of tracks – got turned into something that every city’s train station is assumed to have. It means Eurostar can’t operate into other stations, because there is no surplus of platforms allowing segregating service to the UK away from all other traffic; it also means that planners in the UK that are trying to engineer stations assume British stations must be overbuilt to Parisian specs.

The United States Learned Little from Obama-Era Rail Investment

A few days ago, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) announced Bipartisan Infrastructure Law grants for intercity rail that are not part of the Northeast Corridor program. The total amount disbursed so far is $8.2 billion; more will come, but the slate of projects funded fills me with pessimism about the future of American intercity rail. The total amount of money at stake is a multiple of what the Obama-era stimulus offered, which included $8 billion for intercity rail. The current program has money to move things, but is repeating the mistakes of the Obama era, even as Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg clearly wants to make a difference. I expect the money to, in 10 years, be barely visible as intercity rail improvement – just enough that aggrieved defenders will point to some half-built line or to a line where the program reduced trip times by 15 minutes for billions of dollars, but not enough to make a difference to intercity rail demand.

What happened in the Obama era

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), better known as the Obama stimulus, included $8 billion for what was branded as high-speed rail. Obama and Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood spoke favorably of European and East Asian high-speed rail at the time. And yet, the impetus to spread the money across multiple states’ programs meant that the sum was, by spending, around half for legacy rail projects euphemistically branded as higher-speed rail, a term that denotes “faster than the Amtrak average.” Ohio, Wisconsin, and Illinois happily applied that term to slow lines. The other half went to the Florida and California programs, which were genuinely high-speed rail. In Florida, the money was enough to build the first phase from Orlando to Tampa, together with a small state contribution.

Infamously, Governor Rick Scott rejected the money after he was elected in the 2010 midterms, and so did Governors Scott Walker (R-WI) and John Kasich (R-OH). The money was redistributed to states that wanted it, of which the largest sums went to California and Illinois. And yet, what California got was a fraction of the $10 billion that the High-Speed Rail Authority had been hoping for when it went to ballot in 2008; in turn, the cost overruns that were announced in 2011 meant that even the original hoped-for sum could not build a usable segment. The line has languished since, to the point that Governor Gavin Newsom said “let’s be real” regarding the prospects of finishing the line. Planning is continuing, and the mostly funded, under-construction segment connecting Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced is slated to open 2030-33 (in 2008 the promise was Los Angeles-San Francisco by 2020), but this is a fraction of what was promised by cost or utility; Newsom even defended the Bakersfield-Merced segment on the merits, saying that connecting three small, decentralized metro areas to one another with no onward service to Los Angeles or San Francisco would provide good value and taking umbrage at the notion that it was a “train to nowhere.”

In Illinois, the money went toward improving the Chicago-St. Louis line. However, Union Pacific owns the tracks and demanded, as a precondition of allowing faster trains, that the money be spent on increasing its own capacity, leading to double-tracking on a line that only run five trains a day in each direction; service opened earlier this year, cutting trip times from 5:20-5:35 in 2010 to 4:46-5:03 now, at a cost of $2 billion. This is a 457 km line; the cost per kilometer was not much less than that of the greenfield commuter line to Lahti, which has an hourly commuter train averaging 96 km/h from Helsinki and a sometimes hourly, sometimes bihourly intercity train averaging 120. In effect, UP extracted so much surplus that a small improvement to an existing line cost almost as much as a greenfield medium-speed line.

Lessons not learned

The failure of the ARRA to lead to any noticeable improvement in rail service can be attributed to a number of factors:

- The money was spread thinly to avoid favoring just one state, which was perceived as politically unacceptable (somehow, spending money on a flashy project with no results to show for it was perceived as politically acceptable).

- The federal government could only spend the money on projects that the states planned and asked for – there was no independent federal planning.

- There was inattention to best practices in legacy rail planning, such as clockface timetabling, higher cant deficiency (allowed by FRA regulation since 2010), etc.; while the high-speed rail program aimed to imitate European and East Asian examples, the legacy program had little interest in doing so, even though successful legacy rail improvements in such countries as the UK, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands were available already.

- A dual mandate of both jobs and infrastructure, so that high costs were a positive to an interest group that the federal government and the states announced they wanted to support.

- California specifically was a series of unforced errors, including a politicized High-Speed Rail Authority board representing parochial rather than statewide interests, disinterest in developing any state capacity to plan things (the expression “state capacity” wouldn’t even enter common American political discourse until the late 2010s), early commitment, and, once the combo of cost overruns and insufficient money on hand meant the project had no hope of finishing in the political lifetime of anyone important, disinterest in expediting things.

I have not seen any indication that Buttigieg and his staff learned any of these lessons, and I have seen some indication that they have not.

For one, the dual mandate problem is if anything getting worse, with constant invocations of job creation even as unemployment is below 4% where in 2010 it was 10%, and with growing protectionism; the US has practically no internal market for modern rolling stock and the recent spate of protectionism is leading to surging costs, where until recently there was no American rolling stock cost premium. This is not an intercity rail problem but an infrastructure problem in general in the US, and every time a politician says “this will create jobs,” a surplus-extracting actor gets their wings.

Then, even though the NGO space has increasingly been figuring out some best practices for regional trains, there is still no integration of these practices into infrastructure planning. The allergy to electrification remains, and mainline rail agency officials keep making things up about rest-of-world practices and getting rewarded for it with funds. Despite wide recognition of the extent of surplus extraction by the Class I freight carriers, there is no attempt to steer funding toward lines that are already owned by passenger rail-focused public-sector carriers, like the Los Angeles-San Diego line, much of the Chicago-Detroit line, and the New York-Albany line.

The lack of independent federal planning is if anything getting worse, relative to circumstances. In the Obama era, the Northeast Corridor was put aside. Today, it is the centerpiece of the investment program; I’ve been told that Biden asks about it at briefings about transportation investment and views it as his personal legacy. Well, it could be, but that would require toothy federal planning, and this doesn’t really exist – instead, the investment program is a staple job of parochial interests. Based on this, I doubt that there’s been any progress in federal planning for intercity rail outside the Northeast.

And finally, the money is still being spread too thinly. California is getting $3.1 billion, which is close to but not quite enough to complete Bakersfield-Merced, whose cost is in year-of-expenditure dollars at this point $34 billion for a 275 km system in the easiest geography it could possibly have. Another $3 billion is slated to go to Brightline West, a private scheme to run high-speed trains from Rancho Cucamonga in exurban Los Angeles, about 65 km from city center, to a greenfield site 4 km south of the Las Vegas Strip; the overall cost of the line is projected at $12 billion over a distance of 350 km. It’s likely that this split is worse than either giving all $6 billion to California or giving all of it to Brightline West. But as I am going to point out in the following section, it’s worse than giving the money to places that are not the Western United States.

The frustrating thing is that, just as I am told that Biden deeply cares about the Northeast Corridor, Buttigieg has been quoted as saying that he cares about developing at least one high-speed rail line, as a legacy that he can point to and say “I did that.” Buttigieg is a papabile for the 2028 presidential primary, and is young enough he can delay running for many cycles if he feels 2028 is not the right time, to the point that “I built that” will strengthen his political prospects even if he has to wait until opening in the 2030s. And yet, the money committed will not build high-speed rail. It might build a demonstration segment in California, but a Bakersfield-Fresno line and even a Bakersfield-Merced one with additional funds would scream “white elephant” to the general public.

Is it salvagable?

Yes.

There are, as I understand it, $21.8 billion in uncommitted funds.

What the $21.8 billion is required to achieve is a) a complete high-speed line, b) not touching the Northeast Corridor (which is funded separately and also poorly), c) connecting cities of sufficient size that passenger ridership would make people say “this is a worthy government investment” rather than “this is a bridge to nowhere on steroids.” Even a complete Los Angeles-Las Vegas line is not guaranteed to be it, and Brightline West is saving money by dumping passengers tens of kilometers along congested roads from Downtown Los Angeles.

Given adequate cost control, Chicago-Detroit/Cleveland is viable. It’s around 370 km Chicago-Toledo, 100 km Toledo-Detroit, 180 km Toledo-Cleveland, depending on alignments chosen; $21.8 billion can build it at the same cost projected for Brightline West, in easier topography. If money is almost but not quite enough, then either Cleveland or Detroit can be dropped, which would make the system substantially less valuable but still create some demand for completing the system (Michigan could fund Toledo-Detroit with state money, for example).

But this means that all or nearly all of the remaining funds need to go into that one basket, and Buttigieg needs to gamble that it works. This requires federal coordination – none of the four states on the line has the ability to plan it by itself, and two of them, Indiana and Ohio, are actively hostile. It’s politically fine as a geographic split as it is – that part of the Midwest is sacralized in American political discourse due to its industrial history, which history has also supplied it with large cities that could fill trains to Chicago and even to one another; politicians can more safely call Los Angeles “not real America” than they can Detroit and Cleveland.

But so far, the way the Northeast Corridor money and the recently-announced $8.2 billion for non-Northeast Corridor service have been spent fills me with confidence that this will not be done. The program is salvageable, but I don’t think it will be salvaged. There’s just no interest in having the federal government do this by itself as far as I can see, and the state programs are either horrifically expensive (California) or too compromised (Midwest, Southeast, Pacific Northwest).