Category: Regional Rail

The Hudson Tunnel Project is Funded!

Two days ago, the federal government announced that it was funding the Hudson Tunnel Project, adding two new tunneled tracks between New Jersey and New York Penn Station. The total grant is $6.88 billion, representing slightly less than half of the projected cost, which is officially still $16 billion in year-of-expenditure dollars but may rise to $17 billion; nearly all of the rest of the budget is already matched in state grants from New York and New Jersey, and so for all intents and purposes, the project should be considered fully funded. Frustratingly, it’s an extremely expensive project, and yet its benefits are high that it may still pass a benefit-cost analysis – and the more operational improvements there are down the line, the higher the benefits.

The grant only covers the bare tunnels and a $2 billion project to do long-term repairs to the existing tunnels after damage suffered in Hurricane Sandy. The $14 billion new tunnels are the centerpiece of the wider $40 billion Gateway Program, which includes other items that are said to be necessary for an increase in capacity. But most of those items by cost are duds, such as the completely useless $7 billion Penn Station Expansion program to condemn an entire city block to add tracks, or the useful but not at this price $6 billion Penn Station Reconstruction program to improve pedestrian circulation at the existing station. There still remain necessary improvements on the surface to go along the Hudson Tunnel Project, but they are small – a junction fix here, some double-tracking of a single-track branch there, some high-platform projects to improve reliability yonder.

The reporting on the project says that it will be overseen by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), not the mainline-specific Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). It looks like this is coming from the general bucket of money for mass transit in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, rather than from the $30 billion dedicated to the Northeast Corridor; thus, the budget for other Northeast Corridor improvements should remain $30 billion, rather than $23.12 billion.

The issue of costs

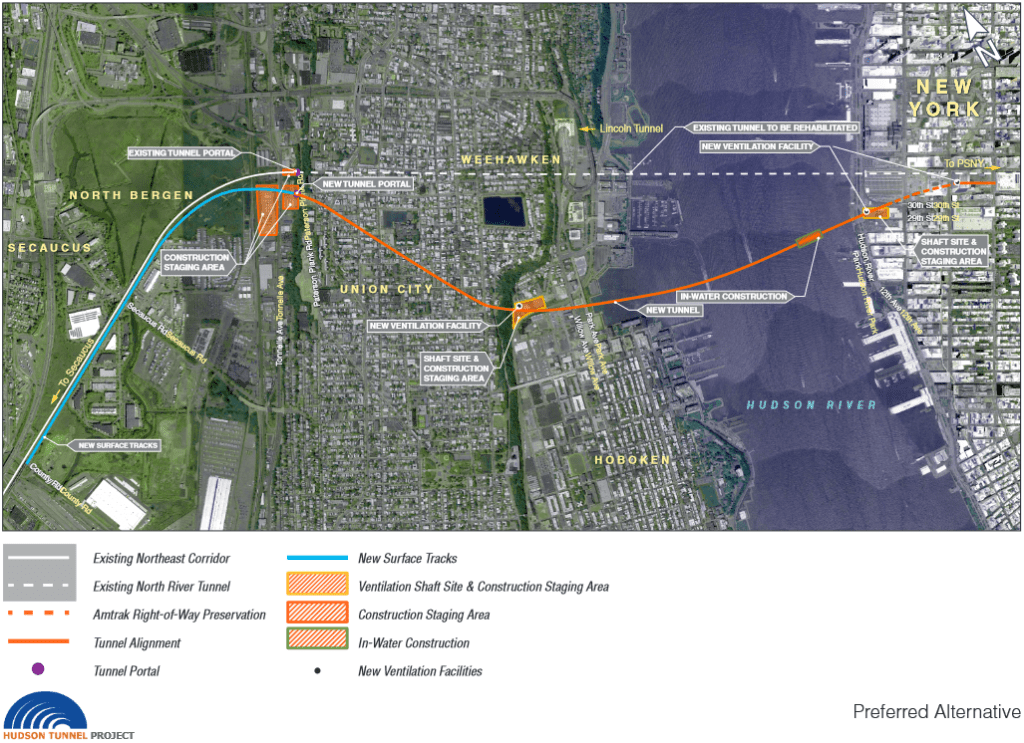

The Hudson Tunnel Project is about five kilometers in length, from the portal on the western slope of the Palisades to the existing Penn Station:

The alignment, as can be seen in the picture, is not closely parallel to the existing tunnels. On the Manhattan side, the alignment is fixed in place, due to the construction of the Hudson Yards project since the project was first mooted in the early 2000s, when it was called Access to the Region’s Core (ARC); the only available alignment between building foundations is as depicted. Under the Hudson and in New Jersey, there are no such constraints.

What is far more suspicious is that 5 km of double-track tunnel, even partly underwater, even partly in Manhattan between skyscraper foundations, are said to cost $14 billion in total. This is not just the usual problem of high New York costs. Second Avenue Subway’s hard costs were 77% stations and station finishes and only 23% tunnels and systems; excluding the stations, and pro-rating the soft costs, the costs in 2022 dollars were only about $500 million per km. There is an underwater premium, but it doesn’t turn $500 million per km into nearly $3 billion per km, nor is the expected inflation rate over the project’s 2023-35 lifetime high enough to make a difference.

What’s more, the underwater premium is highest where the costs are already the lowest. The New York cost premium for civil infrastructure is rather small, only about a factor of around 3 over comparable European projects. Systems and finishes have a considerably higher premium, due to lack of standardization; stations have an even higher premium, due to overbuilding (the Second Avenue Subway stations were 2-3 times as big as necessary, and the two smaller ones were also deep-mined at an additional cost). The installation of systems like electrification and cables should not cost more underwater than underground – the construction of the tunnel and its lining is where the premium is. Whatever we think the underwater construction premium is – a factor of 2 is consistent with some Stockholm numbers and also with the original BART construction in the 1960s and early 70s – it should be lower in New York.

Some of it must come from ever worse project management and soft costs. The destruction of state capacity in the English-speaking world, and increasingly in nonnative English-speaking countries influenced by the UK like the Netherlands, is not a completed process; it is still ongoing. Soft costs keep rising, and the response to every failure is to add yet another layer of consultants or another layer of review. Second Avenue Subway phase 2 manages slightly higher per-km costs than phase 1, despite having less overbuilding, and from my encounters with the people in charge of capital construction at the MTA, it’s not hard to see why.

And yet, even relative to the highest costs of phase 2, Gateway is overpriced. The level of experience the people running this project have with capital construction at this scale is less than that of the MTA, and this should matter. And yet, even that doesn’t explain the large jump in costs.

Is it possible to do better?

Well, once the almost $16 billion for the project is there, it will be spent. The main reason one might oppose overpriced projects like Second Avenue Subway phase 2 even if their benefit-cost ratio is okay (which, for both phase 2 and the Hudson Tunnel Project, is iffy, though not obviously bad), is that pressure to reduce costs before approval can result in efficiencies. But once a budget is approved, nobody will make a serious effort to go significantly below it.

That said, the only smoking gun I have for how to make this project cheaper pertains to the $2 billion for fixing the existing tunnels. Currently, the timetables for both Amtrak and New Jersey Transit trains across the tunnels are written so that on weekends, only one of the two single-track tubes is in operation. Thus, maintenance work can be done on the other tunnel for an uninterrupted 55-hour period. However, Amtrak rarely takes advantage of this. In fact, reporting in the New York Daily News has found that over the last few years, only about once every three months – 13 times in a four-year period from mid-2017 to mid-2021 – has there been a full weekend repair job in one of the tunnels. Accelerated repairs would be able to reduce the costs of the fixes through greater efficiency, and, since American government budgeting is done in nominal dollars, a lower price level than in the mid-2030s.

It’s likely that such egregious examples also exist for the main project, the $14 billion new tunnels. I don’t know of any such example, and I don’t think it’s worthwhile stopping the project over this; but it’s important to remain vigilant and remember that while the tunnels are fully funded for all intents and purposes, a small gap remains and should be fillable without new money.

The benefits of the tunnels

The costs are very high. But what are the benefits?

In isolation, the benefits are that capacity across the Hudson would double. This would enable doubling commuter rail traffic. Before corona, the trains were very crowded, to the point of suppressing demand; ridership is lower now than it was then, but east of the Hudson, Metro-North is at 78% of pre-corona ridership and rising fast. Moreover, the prospects of future growth in commuting in New Jersey are better than those in suburban New York and Connecticut, since New Jersey permits housing at an almost healthy rate, 4 annual housing units per 1,000 people, whereas Long Island permits about 1, Westchester 2-3, and Fairfield County 1.5-2.5. There’s enough pressure in New Jersey even in the short term that a ridership flop like that of East Side Access is very unlikely.

That said, New Jersey Transit only had about 310,000 weekday riders in 2019, double-counting transfers (of which there aren’t many, unlike on the LIRR). Not many more than half those trips even originated or ended at Penn Station – one of the adaptations to overcrowding on New Jersey Transit is to send about half the trains from the Morris and Essex Lines to Hoboken, from which passengers take PATH into the city, and another is for passengers to get off at Newark and transfer to PATH there. Penn Station’s ridership in 2019 was 94,000 boardings, or 188,000 trips; that is the number that could potentially be doubled. So, $14 billion for 188,000 trips; this is $74,000 per rider, which is too high, and if that is the only benefit, then the project should be canceled.

However, the Hudson Tunnel Project interacts positively with every operational improvement in commuter rail. If off-peak frequencies are increased so that passengers can use the trains not just for rush hour commuting, then ridership will rise. Of course, peak frequency is not really relevant to off-peak ridership – but there are advantages from the new tunnels to off-peak service, such as more cleanly separating Northeast Corridor service from Morris and Essex service, improving reliability for both.

And then there are all the necessary small improvements, such as electrification. For example, right now, the Raritan Valley Line today is unelectrified, and passengers have to transfer at Newark to either PATH or a Northeast Corridor or North Jersey Coast Line train to Manhattan; only a handful of trains run to Manhattan using dual-mode locomotives, none at rush hour. The current service plan with the new tunnels is to run ever more trains with dual-mode locomotives, which are exceptionally expensive, heavy, and unreliable. However, the new tunnels interact positively with electrifying the Raritan Valley Line, currently the busiest diesel line in New Jersey, and with wiring short unelectrified tails on the North Jersey Coast and Morris and Essex Lines. These would raise both peak and off-peak ridership – and the extra capacity provided by the new tunnels improves the business case for them, even if the business case is healthy even purely on off-peak travel.

The same is true of platforms. The low platforms at most stations impede efficient boardings. They take too long at rush hour, and they’re inaccessible unless a conductor manually operates a wheelchair lift; conductors are not really cost-effective on commuter trains even at the wages of the 2020s, let alone those of the future. As with electrification, the case for converting all stations to high platforms for level boarding is strong even on off-peak ridership; the benefits are high and the costs are low (New Jersey Transit appears capable of raising platforms for $25 million per station). However, commuter rail managers and suburban politicians are squeamish and ignorant of best practices and only really get peak ridership; thus, the higher peak ridership expected from the new tunnels not only improves the already-strong business case for high platforms, but also makes this business case easier to explain to people who think that off-peak, everyone must drive.

With such improvements to speed and reliability – modern rolling stock (which none of the region’s agencies is interested in acquiring), electrification, high platforms, some junction fixes, and better timetabling (which the region will have to adopt for greater peak throughput) combine to a speed increase of a factor of about 1.5, with all the benefits that this entails.

Necessary efficiencies

Much of the benefit of the Hudson Tunnel Project comprises necessary improvements on the surface, some of which I expect to happen as ancillaries. But then there is also the issue of necessary efficiencies in New York.

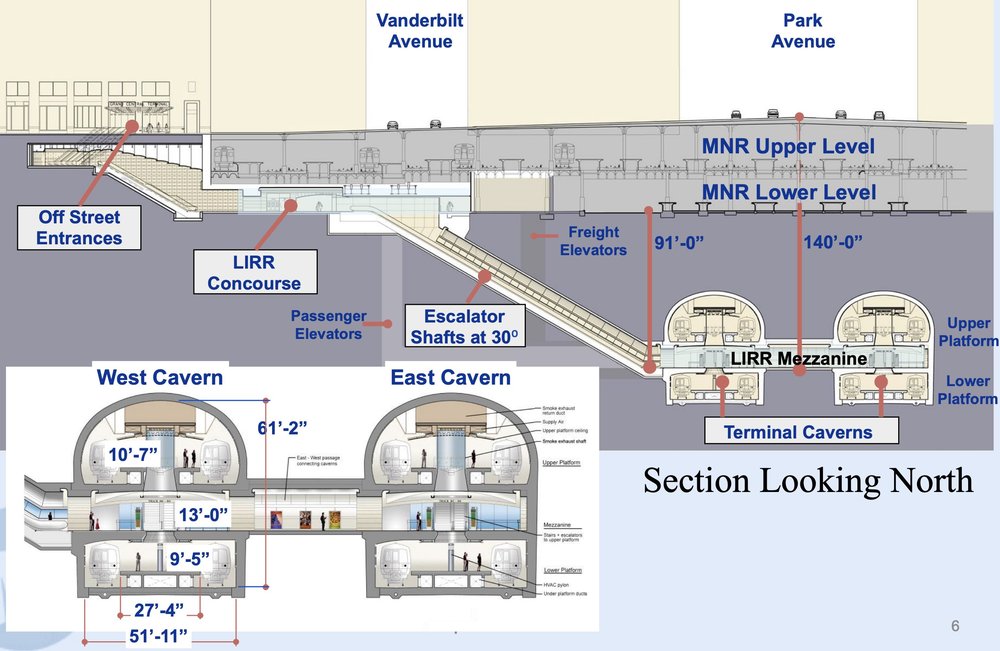

The issue is that the current operating paradigm involves very long turns at Penn Station. LIRR trains terminate from the east and New Jersey Transit trains terminate from the west, and neither railroad turns trains especially quickly. The turn times are on the order of 20 minutes; mainline trains in the United States can reverse direction in service in 10 minutes when they need to (for example, if they’ve arrived late), and even eight minutes look possible, and outside the United States, constrained terminals like Tokyo Station on the Chuo Line or Catalunya on FGC do it much faster.

The relevance is that agency officials keep saying, falsely, that Penn Station Expansion is necessary for the full increase in capacity coming from the new tunnels. But they are not going to get the money for the expansion; it competes with so many other priorities for a pool of money, $30 billion for the entire Northeast Corridor, that is large compared to normal-world costs but small compared to American ones. This means that they’re going to have to make necessary efficiencies.

Through-running is one such efficiency. But there are others – chiefly, turning faster at terminals, since the new tunnels would mainly feed stub-end tracks. This, in turn, means better service in general, with lower operating costs and (if there’s through-running) better service for passengers.

On just a raw estimate of extra peak capacity, there just isn’t enough ridership to justify $14-16 billion in funding for new tunnels. But once all the necessary improvements and efficiencies come in, the benefit-cost analysis looks much healthier. It doesn’t mean anyone should be happy about the budget – agencies and area advocates should do what they can to make sure money is saved and the same budget can build more things (like all these necessary improvements) – but it could be more like the extremely high-cost and yet high-benefit Second Avenue Suwbay phase 1 and not like the failure that is East Side Access.

The LIRR and East Side Access

East Side Access opened in February, about four months ago, connecting the LIRR to Grand Central; previously, trains only went to Penn Station. The opening was not at all smooth – commuters mostly wanted to keep going to Penn Station, contrary to early-2000s projections, and stories of confused riders were common in local media. I held judgment at the time because big changes take time to show their benefits, but in the months since, ridership has not done well. On current statistics, it appears that the opening of the new tunnel to Grand Central has had no benefit at all, making this project not just the world leader in tunneling cost per kilometer (about $4 billion) but also one with no apparent transportation value.

What is East Side Access?

Traditionally, of New York’s two main train stations, Penn Station only served Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and the LIRR, whereas Grand Central only served Metro-North. East Side Access is a tunnel from the LIRR Main Line to Grand Central, permitting trains to serve either of the two stations; an under-construction project called Penn Station Access likewise will permit one Metro-North line to serve Penn Station.

The tunnel across the East River was built in the 1970s and 80s together with the tunnel that now carries the F train; East Side Access was the project to build the connection from this tunnel to Grand Central as well as to the LIRR Main Line in Queens. The Grand Central connection does not lead to the preexisting Metro-North terminal with its tens of tracks, but to a deep cavern:

What was East Side Access supposed to serve?

Penn Station’s location is at the southwestern margin of the job concetration of Midtown Manhattan. Grand Central’s location is better; the studies done for the project 20 years ago found that for the majority of LIRR commuters, Grand Central was closer to their job than Penn Station. In 2019, there were 589,770 jobs within 1 km of Penn Station’s northeast corner at 7th and 33rd, of whom 48,460 lived on Long Island; within 1 km of Grand Central’s southern entrance at Park and 42nd, the corresponding numbers are 680,586 and 57,457.

Based on such analysis, the plan was to send as many trains as possible to Grand Central, at the expense of trains that used not to enter Manhattan at all but instead diverted to Downtown Brooklyn (within 1 km of Atlantic and Flatbush there were 41,360 jobs in 2019, of which 3,895 were held by Long Islanders). The central transfer point at Jamaica was reconfigured to no longer permit cross-platform transfers between Brooklyn- and Penn Station-bound trains in order to facilitate more direct trains to Grand Central.

The state promised large increases in both capacity and ridership; in 2022, joint Metro-North and LIRR head Catherine Rinaldi said they were increasing service by 40%. Unfortunately, ridership has flopped.

Ridership is a flop

The most recent publication about New York commuter rail ridership is from a week ago. LIRR ridership in May was about 5.6 million, with a peak of 229,000 passengers per weekday; ridership before corona was 316,000 per weekday. Metro-North, with no opening comparable to that of East Side Access, had 5.43 million riders in May with a peak of 215,000 passengers – but pre-corona ridership was 276,000. Metro-North has held up better the LIRR and recovered faster: May 2023 was 28% above May 2022, whereas for the LIRR, it was only 23%.

The same publication speaks of East Side Access positively – as it must, as an official report. It says the share of LIRR ridership is transitioning toward 65% Penn Station, 35% Grand Central. But this by itself already raises questions. The easier access to Grand Central and the extra capacity should have raised ridership; in the report, no surge is apparent since February of this year. Judging by the example of Metro-North, it appears that no net ridership has appeared as a result of the new project.

What’s going on here?

I’ve spent many years criticizing reverse-branching, in which a trunk line outside city center splits into branches in the core, in this case some trains serving Penn Station and others serving Grand Central. For East Side Access, my recommendation was to have one specific track pair, such as the express Main Line tracks, only carry trains to Grand Central, and the rest, such as the local tracks and Port Washington Branch tracks, only carry trains to Penn Station. The disappointing ridership of East Side Access has led some area transit advocates to criticize the MTA on the grounds that the problem is one of reverse-branching.

The media stories in late winter and early spring of confused commuters are certainly consistent with my criticism of reverse-branching. Everything that’s happened is consistent with that criticism, and yet I’m not certain that this is what’s going on. After all, East Side Access also adds new service and new capacity. Potentially, it’s about the loss of Jamaica transfers, but then which trains would people even want to transfer from?

The main mechanisms by which reverse-branching hurts ridership are that it makes schedule planning too complex and thereby reduces reliability, and that the frequency on each reverse-branch is reduced. LIRR scheduling is already extremely complex, with one-off express patterns and trains weaving around one another at rush hour; in 2015, I looked at some rush hour schedules and compared them with the rolling stock’s technical capabilities and found that even relative to the derated capabilities of the trains, the timetables are padded by 32% on the Main Line. (Metro-North seems comparably padded.) East Side Access would hardly make this much worse. The second mechanism is frequency – but at rush hour, frequency at each suburban station is decent, if not great.

But then, I can’t think of anything else that fits. The issue could not be some permanent decrease in commuting, or some permanent decrease in commuting to Grand Central specifically, since Metro-North ridership has recovered better and all trains there go to Grand Central. It could potentially be some force of habit inducing LIRR commuters to stay on the trains they’re familiar with, but then we should see gradual increase in ridership since opening and we’re not seeing that at any higher rate than at Metro-North.

Why Commuters Prefer Origin to Destination Transfers

It’s an empirical observation that rail riders who are faced with a transfer are much more likely to make the trip if it’s near their home than near their destination. Reinhard Clever’s since-linkrotted work gives an example from Toronto, and American commuter rail rider behavior in general; I was discussing it from the earliest days of this blog. He points out that American and Canadian commuter rail riders drive long distances just to get to a cheaper or faster park-and-ride stations, but are reluctant to take the train if they have any transfer at the city center end.

This pattern is especially relevant as, due to continued job sprawl, American rail reformers keep looking for new markets for commuter rail to serve and set their eyes on commutes to the suburbs. Garrett Wollman is giving an example, in the context of the Agricultural Branch, a low-usage freight line linking to the Boston-Worcester commuter line that could be used for local passenger rail service. Garrett talks about the potential ridership of the line, counting people living near it and people working near it. And inadvertently, his post makes it clear why the pattern Clever saw in Toronto is as it is.

Residential and job sprawl

The issue at hand is that residential sprawl and job sprawl both require riders to spend some time connecting to the train. The more typical example of residential sprawl involves isotropic single-family density in a suburban region, with commuters driving to the train station to get on a train to city center; they could be parking there or being dropped off by family, but in either case, the interface to the train for them is in their own car.

Job sprawl is different. Garrett points out that there are 79,000 jobs within two miles of a potential station on the Ag Branch, within the range of corporate shuttles. With current development pattern, rail service on the branch could follow the best practices there are and I doubt it would get 5% of those workers as riders, for all of the following reasons:

- The corporate shuttle is a bus, with all the discomfort that implies; it usually is also restricted in hours even more than traditional North American commuter rail – the frequency on the LIRR or even Caltrain is low off-peak but the trains do run all day, whereas corporate shuttles have a tendency to only run at peak. There is no own-car interface involved.

- The traditional car-commuter train interface is to jobs in areas with traffic congestion and difficult parking. The jobs in the suburbs face neither constraint. Of note, Long Islanders working in Manhattan do transfer to the subway, because driving to the East Side to avoid the transfer from Penn Station is not a realistic option.

- The traditional car-commuter train interface is to jobs in a city center served from all directions by commuter rail. In contrast, the jobs in the suburbs are only served by commuter rail along a single axis. There is a fair amount of reverse-peak ridership from San Francisco to Silicon Valley jobs or from New York to White Plains and Stamford jobs, even if at far lower rates than the traditional peak direction – but most people working at a suburban job center live in another suburb, own a car, and either commute in a different direction from that of the train or don’t live and work close enough to a station that the car-train-shuttle trip is faster than an all-car trip.

Those features are immutable without further changes in urban design. Then there are other features that interact with the current timetables and fares. North American commuter rail has so many features designed to appeal to the type of person who drives everywhere and uses the train as a shuttle extending their car-oriented lifestyle into the city – premium fares, heavy marketing as different from normal public transit, poor integration with said normal public transit – that interface with one’s own car is especially valuable, and interface with public transit is especially unvalued.

And yet, it’s clearly possible to make it work. How?

How Europe makes it work

Commuter trains in Europe (nobody calls them regional rail here – that term is reserved for hourly long-range trains) get a lot of off-peak ridership and are not at all used exclusively by 9-to-5 commuters who drive for all other purposes. Some of this is to suburban job centers. How does this work, besides timetables and other operating practices that American reformers recognize as superior to what’s available in the US and Canada?

The primary answer is near-center jobs. Paris and La Défense have, between them, about 37% of the total jobs of Ile-de-France. Within the same land area, 100 km^2, both New York and Boston have a similar proportion of the jobs in their respective metro areas, about 35% each, as does San Francisco within the smaller definition of the metro area, excluding Silicon Valley. Ile-de-France’s work trip modal split is about 43%, metro New York’s is 33%, metro San Francisco’s is 17%, metro Boston’s is 12%.

So where Boston specifically fails is not so much office park jobs, such as those on Route 128, but near-center jobs. Its urban and suburban transit networks do a poor job of getting people to job centers like Longwood, the airport, Cambridge, and the Seaport. The same is true of San Francisco. New York’s network does a better but still mediocre job at connecting to Long Island City and Downtown Brooklyn, and a rather bad job at connecting to inner-suburban New Jersey jobs, but so many of those 35% jobs in the central 100 km^2 are in fact in the central 23 km^2 of the Manhattan core, and nearly half are in the central 4 km^2 comprising Midtown, that the poor service to the other 77 km^2 can be overlooked.

As far as commuter rail is concerned, the main difference in ridership between the main European networks – the Paris RER, the Berlin S-Bahn, and so on – and the American ones is how useful they are for plain urban service. Nearly all Berlin S-Bahn traffic is within the city, not the suburbs; the RER’s workhorse stations are mostly in dense inner suburbs that in most other countries would have been amalgamated into the city already.

To the extent that this relates to American commuter rail reforms, it’s about coverage within the city: multiple city stations, good (free, frequent) connections to local urban rail, high frequency all day to encourage urban travel (a train within the city that runs every half an hour might as well not run).

Suburban ridership is better here as well, but this piggybacks on very strong urban service, giving strong service from the suburbs to the city. Suburb-to-suburb commutes are done largely by car – Ile-de-France’s modal split is 43%, not 80%; there are fewer of them than in most of the US, but not fewer than in New York, Boston, or San Francisco.

But, well, Paris’s modal split is noticeably higher than the job share within the city – a job share that does include drivers. What gives?

Suburban transit-oriented development

TOD in the suburbs can create a pleasant enough rail commute that the modal split is respectable, if nothing like what is seen for jobs in Paris or Manhattan. However, for this to work, planners must eliminate the expression “corporate shuttle” from their lexicon.

Instead, suburban job sites must be placed right on top of the train station, or within walking distance along streets that are decently walkable. I can’t think of good Berlin examples – Berlin maintains high modal split through a strong center – but I can think of several Parisian ones: Marne-la-Vallée (including Disneyland), Noisy, Evry, Cergy. Those were often built simultaneously with greenfield suburban lines that were then connected to the RER, rather than on top of preexisting commuter lines.

They look nothing like American job sprawl. Here, for example, is Cergy:

There are parking garages visible near the train stations, but also a massing of mid-rise residential and commercial buildings.

But speaking of residential, the issue is that employers looking for sites to locate to have no real reason to build offices on top of most suburban train stations – the likeliest highest and best usage is residential. In the case of American TOD, even the secondary-urban centers, like Worcester, probably have much more demand for residential than commercial TOD within walking distance of the train station – employers who are willing to pay near-train station premium rent might as well pay the higher premium of locating within the primary city, where the commuter shed is much larger.

In effect, the suburban TOD model does not counter the traditional monocentric urban layout. It instead extends it to a much larger scale. In this schema, the entirety of the city, and not just its central few square kilometers, is the monocenter, served by different lines with many stations on them. Berlin is ahead of the curve by virtue of its having multiple close-by centers as a Cold War legacy, but Paris is similar (its highest-intensity commercial TOD is in La Défense and in in-city sites like Bercy, on top of former railyards attached to Gare de Lyon).

At no point does this model include destination-end transfers in the suburbs. In the city, it does: a single line cannot cover all urban job sites; but the transfer is within the rapid transit system. But in the suburbs, the jobs that are serviceable by public transportation are within walking distance of the station. Shuttles may exist, but are secondary, and job sites that require them are and will always be auto-centric.

Assume Normal Costs: An Update

The maps below detail what New York could build if its construction costs were normal, rather than the highest in the world for reasons that the city and state could choose to change. I’ve been working on this for a while – we considered including these maps in our final report before removing them from scope to save time.

Higher-resolution images can be found here and here; they’re 53 MB each.

Didn’t you do this before?

Yes. I wrote a post to a similar effect four years ago. The maps here are updated to include slightly different lines – I think the new one reflects city transportation needs better – and to add light rail and not just subway and commuter rail tunnels. But more importantly, the new maps have much higher costs, reflecting a few years’ worth of inflation (this is 2022 dollars) and some large real cost increases in Scandinavia.

What’s included in the maps?

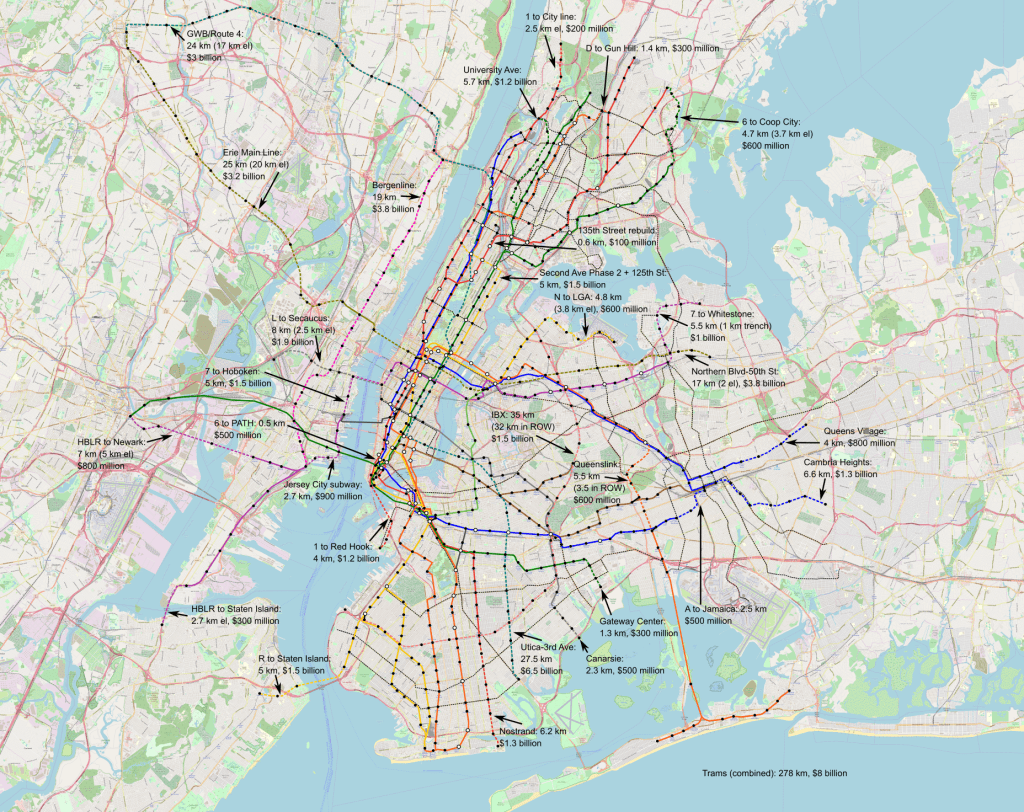

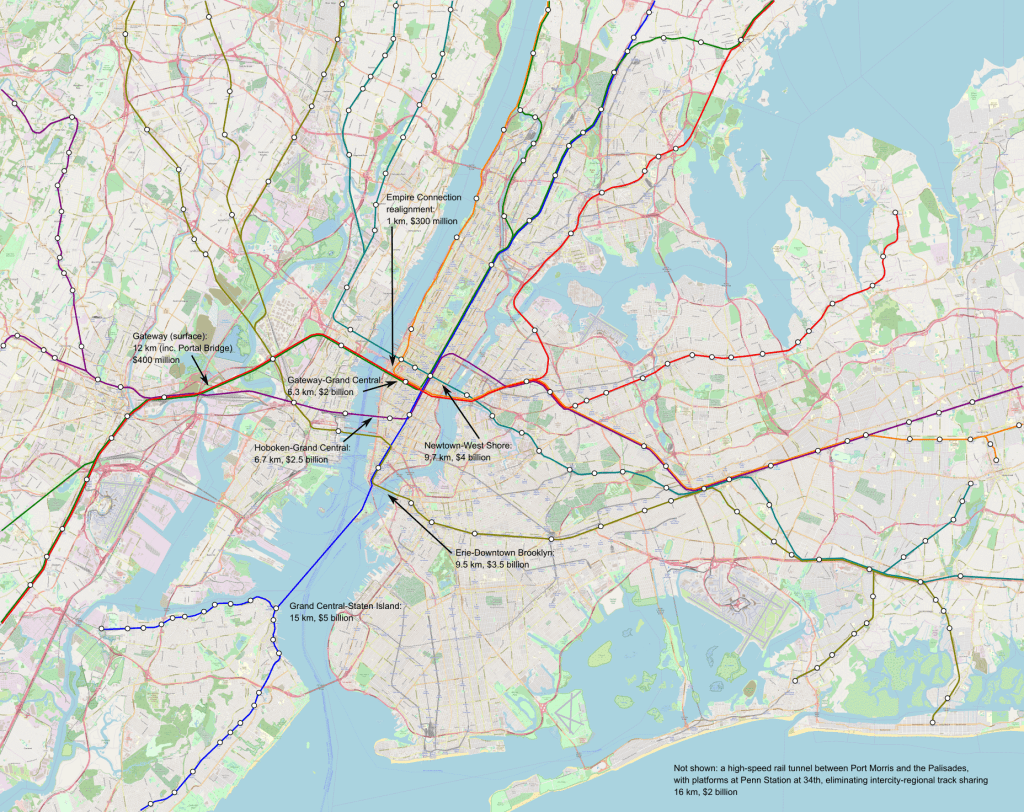

The maps include the following items:

- 278 km of new streetcars, which are envisioned to be in dedicated lanes; on the Brooklyn and Queensborough Bridges, they’d share the bridges’ grade separation from traffic into Manhattan, which in the case of the Brooklyn Bridge should be an elevated version of the branched subway-surface lines of Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and most German cities. Those should cost $8 billion in total, based on Eno’s European numbers plus some recent urban German projects.

- 240 km of new subway lines, divided as 147.6 km in the city (97.1 km underground) and 92.4 km across the Hudson and in New Jersey (45.2 km underground). Of those 240 km, 147.5 km comprise four new trunk lines, including the already-planned IBX, and the rest are extensions of existing lines. Those should cost $25.2 billion for the city lines and $15.4 billion for the New Jersey lines.

- Rearrangement of existing lines to reduce branching (“deinterlining“) and improve capacity and schedule robustness; the PATH changes are especially radical, turning the system into extensions of the 6 and 7 trains plus a Hoboken-Herald Square shuttle.

- 48.2 km of commuter rail tunnels, creating seven independent trunk lines across the region, all running across between suburbs through the Manhattan core. In addition to some surface improvements between New York and Newark, those should cost $17.7 billion, but some additional costs, totaling low single-digit billions, need to be incurred for further improvements to junctions, station platforms, and electrification.

The different mode of transportation are intended to work together. They’re split across two maps to avoid cluttering the core too much, but the transfers should be free and the fares should be the same within each zone (thus, all trains within the city must charge MetroCard/OMNY fare, including commuter rail and the JFK AirTrain). The best way to connect between two stations may involve changing modes – this is why there are three light rail lines terminating at or near JFK not connecting to one another except via the AirTrain.

What else is included?

There must be concurrent improvements in the quality of service and stations that are not visible on a map:

- Wheelchair accessibility at every station is a must, and must be built immediately; a judge with courage, an interest in improving the region, and an eye for enforcing civil rights and accessibility laws should impose a deadline in the early to mid 2030s for full compliance. A reasonable budget, based on Berlin, Madrid, and Milan, is about $10-15 million per remaining station, a total of around $4 billion.

- Platform edge doors at every station are a good investment as well. They facilitate air conditioning underground; they create more space on the platform because they make it easier to stand closer to the platform edge when the station is crowded; they eliminate deaths and injuries from accidental falls, suicides, and criminal pushes. The only data point I have is from Paris, where pro-rated to New York’s length it should be $10 million per station and $5 billion citywide.

- Signaling must be upgraded to the most modern standards; the L and 7 trains are mostly there already, with communications-based train control (CBTC). Based on automation costs in Nuremberg and Paris, this should be about $6 billion systemwide. The greater precision of computers has sped up Paris Métro lines by almost 20% and increased capacity. Together with the deinterlining program, a single subway track pair, currently capped at 24 trains an hour in most cases, could run about 40 trains per hour.

- Improvements in operations and maintenance efficiency don’t cost money, just political capital, but permit service to be more reliable while cutting New York’s operating expense, which are 1.5-2.5 time a high as the norm for large first-world subway systems.

The frequency on the subway and streetcar lines depicted on the map must conform to the Six-Minute Service campaign demand of Riders Alliance and allies. This means that streetcars and subway branches run very six minute all day, every day, and subway trunk lines like the 6, 7, and L get twice as much frequency.

What alternatives are there?

Some decisions on the map are set in stone: an extension of Second Avenue Subway into Harlem and thence west along 125th Street must be a top priority, done better than the present-day project with it extravagant costs. However, others have alternatives, not depicted.

One notable place where this could easily be done another way is the assignment of local and express trains feeding Eighth and Sixth Avenues. As depicted, in Queens, F trains run local to Sixth Avenue and E trains run express to Eighth; then, to keep the local and express patterns consistent, Washington Heights trains run local and Grand Concourse trains run express. But this could be flipped entirely, with the advantage of eliminating the awkward Jamaica-to-Manhattan-to-Jamaica service and replacing it with straighter lines. Or, service patterns could change, so that the E runs express in Queen and local in Manhattan as it does today.

Another is the commuter rail tunnel system in Lower Manhattan. There are many options for how to connect New Jersey, Lower Manhattan, and Brooklyn; I believe what I drew, via the Erie Railroad’s historic alignment to Pavonia/Newport, is the best option, but there are alternatives and all must be studied seriously. The location of the Lower Manhattan transfer station likewise requires a delicate engineering study, and the answer may be that additional stops are prudent, for example two stops at City Hall and South Ferry rather than the single depicted station at Fulton Street.

What are those costs?

I encourage people to read our costs report to look at what goes into the numbers. But, in brief, we’ve identified a recipe to cut New York subway construction costs by a factor of 9-10. On current numbers, this means New York can cut its subway construction costs to $200-250 million per kilometer – a bit less in the easiest places like Eastern Queens, somewhat more in Manhattan or across water. Commuter rail tunnel costs are higher, first because they tend to be built only in the most difficult areas – in easier ones, commuter rail uses legacy lines – and second because they involve bigger stations in more constrained areas. Those, too, follow what we’ve found in comparison cases in Southern Europe, the Nordic countries, Turkey, France, and Germany.

In total, the costs so projected on the map, $66.3 billion in total, are only slightly higher than the total cost of Grand Paris Express, which is $60 billion in 2022 dollars. But Paris is also building other Métro, RER, and tramway extensions at the same time; this means that even the program I’m proposing, implemented over 15 years, would still leave New York spending less money than Paris.

Is this possible?

Yes. The governance changes we outline are all doable at the state level; federal officials can nudge things and city politician can assist and support. There’s little confidence that current leadership even wants to build, let alone knows what to do, but it’s all doable, and our report linked in the lede provides the blueprint.

Large Urban Terminals are Unnecessary

London and Paris are both famous for their elaborate rail terminals, each with many tracks to store trains connecting the capital with one direction of the country’s provinces. This leads rail advocates to romanticize this type of station; Jarrett Walker said in 2009 that these stations make the arriving passengers feel grander for, in theory, being able to walk directly from platform to station entrance without changing levels. Earlier this month, Ido Klein generalized from London and Paris to the rest of Europe, arguing that the setup in Tel Aviv, with only through-tracks on the Ayalon Railway and only six platform tracks at Savidor Center, is inadequate. Ido is incorrect on this; the Israel Railways network needs continued capital investment in the Ayalon Railway and not in alternatives such as more terminating tracks or a bypass.

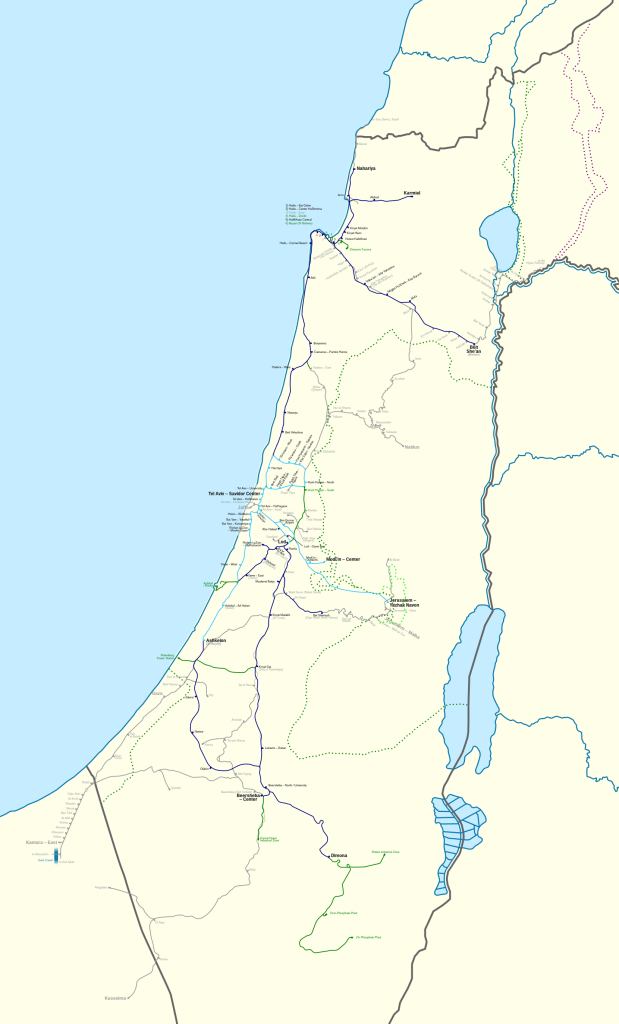

What is the situation in Israel?

The Israel Railways network, owing to Israel’s small size and lack of connections to other countries, is in effect an interregional system, in which the most common intercity trips are 60 km (Tel Aviv-Jerusalem) or 90 km (Tel Aviv-Haifa). Due to the country’s narrow width, it is entirely centered on Tel Aviv, where the four stations of the Ayalon Railway – University, Savidor Center, HaShalom, HaHagana – are on pre-corona numbers the four busiest in the country; this leads to much political distaste, as everywhere else in the Israeli economy.

The Ayalon Railway has three tracks, with plans for a fourth in the design phase; capacity is said to be around 14 trains per hour per track, even with the latest ETCS signals, and I’ve been told of at least one Israel Railways manager who disbelieved that the Munich S-Bahn could push 30 trains per hour per track. The main station in construction is Savidor Center, which has six platform tracks, but in ridership it is second to HaShalom, which is better-located in the Tel Aviv central business district and has only three tracks. Practically all trains run through Tel Aviv – only the trains to Jerusalem terminate in Tel Aviv.

Do trains need to terminate in or bypass Tel Aviv?

No.

There are plans for a bypass railway east of the city, but they’re largely for political reasons, signifying that the state supports decentralizing economic geography away from Tel Aviv. The most important city pair not involving Tel Aviv, Haifa-Jerusalem, does not get any faster via the bypass, and will be direct via the Ayalon Railway as soon as electrification is completed up to Haifa. The city pair that could most gain from a Tel Aviv bypass, Jerusalem-Beer Sheva, has its most direct route passing through Bethlehem and Hebron, which besides being in the Territories (and in Area A) have terrain from hell.

Terminal tracks are likewise useless. Demand from Tel Aviv to points north and south is fairly symmetric on both intercity and commuter rail; there was some asymmetry before the new Tel Aviv-Jerusalem line opened, but at this point Jerusalem’s one station has elbowed its way to the number four position, narrowly ahead of Tel Aviv University, and together with Beer Sheva, Jerusalem forms a fine counterpart to Haifa.

But what about Europe?

Ido’s thread goes over the largest 10 metropolitan areas in the EU and UK, and looks at their intercity rail stations, which he defines as stations serving lines of at least 200 km in length. Among those, he finds that London and Paris only have terminals (their through-stations are for regional rail), and the same is true of Milan, Rome, and Athens. However, from that point, things fall apart.

First, Madrid, Barcelona, and Warsaw have intercity rail through-stations; Ido incorrectly says they are not. Madrid Atocha is a through-station; there’s little to no AVE through-service there or at Chamartín, but they are both through-stations, and the medium-speed Alvias, which are faster than anything in Israel, run through routinely. Barcelona-Sants has AVE through-service between Madrid and France; most trains terminate, but that’s because of asymmetric demand, not because it’s inherently better. Warsaw has a through-tunnel and many through-running intercity trains listed as serving Warszawa Centralna.

Second, Ido skips over Germany. He portrays Berlin as atypical for having a through-station at Hauptbahnhof, but the Berlin way is what Germany wishes were the norm for all cities. Smaller German cities either have through-stations, like Hanover or the cities of the Rhine-Ruhr, or act as pinch-points, with through-trains coming in and reversing direction to continue onward, including Leipzig, Frankfurt, and (until Stuttgart 21 opens) Stuttgart. The pinch-point operations are as efficient as they can be, but still occupy more platform and approach slots than through-trains would.

Third, the actual practice of Paris and London is that it’s assumed people only travel between the capital and a provincial city. France and the UK do not have good everywhere-to-everywhere trains. Paris has a bypass, the Interconnexion Est, but the service quality on it is terrible: the operating paradigm is that trains that bypass Paris make every intermediate stop, which takes 5-10 minutes per station, as the TGVs are not designed for fast boarding and alighting at intermediate points but for nonstop Paris-provincial city trips.

The way forward

Province-province trips are difficult to serve with high frequency. Therefore, the best practice for them is to run through the main city if possible. Israel can do it, using the Ayalon Railway, and once electrification provides through-service from Haifa to Jerusalem, this city pair can piggyback on the higher demand of Haifa-Tel Aviv and Tel Aviv-Jerusalem to serve passengers frequently. Israel is famously small; Haifa-Jerusalem is around 150 km and 1:36 with upcoming speedups planned for electrification and other investments – trains have to run at worst every 20-30 minutes to avoid throwing away ridership, and this can only be supported if they run through Tel Aviv.

London and Paris have many rail terminals because they were huge cities in the steam era and private railroads figured they should connect the capital with one section of the country. This inherited infrastructure is a liability to both of their respective national rail networks, especially that of France, where Paris is centrally located and could be the center of a Lille-Marseille spine. Israel’s newer network lacks this seam, and this should be celebrated and form the basis of further investment.

The most important investment is to ensure that the Ayalon Railway can run at decent capacity. Electric multiple units on regional and interregional rail systems with more complexity than that of Israel Railways do much better than 14 trains per hour on each track: Zurich does 16 and is (I believe) capable of 24, Munich does 30, Tokyo does 24 on some commuter lines with comparable length to Israel’s intercity lines. This is not a problem of the signaling system, which has been upgraded to ETCS Level 2 at the same time as the electrification project. Rather, it’s a problem of how the trains are timetabled, and possibly also of infrastructure on the commuter rail branches, some of which are still single-track.

If it’s possible to cancel the Eastern Railway plans, it should be canceled. There isn’t much that’s being served on the way, and the split in frequency between Haifa-Tel Aviv, Tel-Aviv Jerusalem, and Haifa-Jerusalem trains would seriously hurt ridership on the last of the three city pairs. The fourth track on Ayalon Railway is useful, but long-term plans to go up to six tracks should be shelved – a four-track electrified line could support a large multiple of current traffic.

Can Intercity Trains into Boston Enter from Springfield?

From time to time, I see plans for intercity rail service into Boston going via Springfield. These include in-state rail plans to run trains between the two cities, but also grander plans to have train go between Boston and New Haven via Springfield, branded as the Inland Route, as an alternative to the present-day Northeast Corridor. In-state service is fine, and timed connections to New Haven are also fine for the benefit of interregional travel like Worcester-Hartford, but as an intercity connection, the Inland Route is a terrible choice, and no accommodation should be made for it in any plans. This post goes over why.

What is the Inland Route?

Via Wikipedia, here’s a map of the Northeast Corridor and connecting passenger rail lines:

Red denotes Amtrak ownership, and thus some non-Northeast Corridor sections owned by Amtrak are included, whereas the New Rochelle-New Haven section, while part of the corridor, is not in red because it is owned by state commuter rail authorities. Blue denotes commuter rail lines that use the corridor.

The Inland Route is the rail route in red and black from New Haven to Boston via Springfield. Historically, it was the first all-rail route between New York and Boston: the current route, called the Shore Line, was difficult to build with the technology of the 1840s because it required many river crossings, and only in 1889 was the last river bridged, the Thames just east of New London. However, as soon as the all-rail Shore Line route opened, mainline traffic shifted to it. Further investment in the Shore Line relegated the Inland Route to a secondary role, and today, the only passenger rail at all between Boston and Springfield comprises a daily night train to Chicago, the Lake Shore Limited. More recently, there has been investment in New Haven-Springfield trains, dubbed the Hartford Line, which runs every 1-2 hours with a few additional peak trips.

What rail service should run to Springfield?

Springfield is a secondary urban center, acting as the most significant city in the Pioneer Valley region, which has 700,000 people. It’s close to Hartford, with a metro population of 1.3 million, enough that the metro areas are in the process of merging; this is enough population that some rail service to both New York and Boston is merited.

In both cases, it’s important to follow best practices, which the current Hartford Line does not. I enumerated them for urban commuter rail yesterday, and in the case of intercity or interregional rail, the points about electrification and frequency remain apt. The frequency section on commuter rail talks about suburbs within 30 km of the city, and Springfield is much farther away, so the minimum viable frequency is lower than for suburban rail – hourly service is fine, and half-hourly service is at the limit beyond which further increases in frequency no longer generate much convenience benefit for passengers.

It’s also crucial to timetable the trains right. Not only should they be running on a clockface hourly (ideally half-hourly) schedule, but also everything should be timed to connect. This includes all of the following services:

- Intercity trains to Hartford, New Haven, and New York

- Intercity trains to Boston

- Regional trains upriver to smaller Pioneer Valley cities like Northampton and Greenfield (those must be at least half-hourly as they cover a shorter distance)

- Springfield buses serving Union Station, which acts as a combined bus-rail hub (PVTA service is infrequent, so the transfers can and should be timed)

The timed connections override all other considerations: if the demand to Boston and New York is asymmetric, and it almost certainly is, then the trains to New York should be longer than those to Boston. Through-running here is useful but not essential – there are at least three directions with viable service (New York, Boston, Greenfield) so some people have to transfer anyway, and the frequency is such that transfers have to be timed anyway.

What are the Inland Route plans?

There are perennial plans to add a few intercity trains on the New Haven-Springfield-Boston route. Some such trains ran in my lifetime – Amtrak only canceled the last ones in the 2000s, as improvements in the Shore Line for the Acela, including electrification of the New Haven-Boston section, made the Inland Route too slow to be viable.

Nonetheless, plans for restoration remain. These to some extent extend the plans for in-state Boston-Springfield rail, locally called East-West Rail: if trains run from Boston to Springfield and from Springfield to New Haven, then they might as well through-run. But some plans go further and posit that this should be a competitive end-to-end service, charging lower fares than the faster Northeast Corridor. Those plans, sitting on a shelf somewhere, are enough that Massachusetts is taking them into account when designing South Station.

Of note, no modernization is included in these plans. The trains are to be towed by diesel locomotives, and run on the existing line. Both the Inland Route and East-West plans assume frequency is measured in trains per day, designed by people who look backward to a mythologized golden age of American rail and not forward to foreign timetabling practices that have only been figured out in the last 50 years.

Is the Inland Route viable as an intercity route into Boston?

No. This is not even a slag on the existing plans; I’m happy assuming best practices in other cases, hence my talk of timed half-hourly connections between trains and buses above. The point is that even with best practices, there is no way to competitively run a New Haven-Springfield-Boston route.

The graphic above is suggestive of the first problem: the route is curvy. The Shore Line is very curvy as well, but less so; it has a bad reputation because its curves slow trains that in theory can run at 240 km/h down to about 150-180 km/h, but the Boston-Springfield Line has tighter curves over a longer stretch, they’re just less relevant now because the trains on the line don’t run fast anyway. In contrast, the existing Northeast Corridor route is fast in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

The Inland Route is also curvy on the Boston-Worcester stretch, where consideration for slow trains is a must. The main way to squeeze extra speed out of a curvy line is to cant it, but this is less viable if there is a mix of fast and slow trains, since slow trains would be overcanted. This, in fact, is the reason Amtrak trains outside the Northeast are slower than they were in the middle of the 20th century – long-distance passenger trains have less priority for infrastructure design than slow freight trains, and so cant is limited, especially when there are hills. Normally, it’s not a problem if the slower trains are commuter trains, which run fast enough that they can just take the curve, but some curves are adjacent to passenger train stations, where passengers would definitely notice the train sitting still on canted track, leaning to the inside of the curve.

Then, there is the issue of how one gets into Boston. The Providence Line is straight and fast and can be upgraded to provide extra capacity so that fast intercity trains can overtake slow ones if need be. The Worcester Line has a two-track narrows in Newton, hemmed by I-90 with no possibility of expansion, with three stations on this stretch and a good location for a fourth one at Newton Corner. Overtakes are possible elsewhere (one is being designed just to the west, in Wellesley – see my sample timetable here), but they still constrain capacity. It’s comparably difficult from the point of view of infrastructure design to run a 360 km/h intercity train every 15 minutes via Providence and to run a 160 km/h intercity train every 30 minutes via Springfield and Worcester. Both options require small overtake facilities; higher frequency requires much more in both cases.

The Worcester Line is difficult enough that Boston-Springfield trains should be viewed as Boston-Worcester trains that go farther west. If there’s room in the timetable to include more express trains then these can be the trains to Springfield, but if there’s any difficulty, or if the plan doesn’t have more than a train every half hour to Worcester, then trains to Springfield should be making the same stops as Boston-Worcester trains.

Incentives for passengers

The worst argument I’ve seen for Inland Route service is that it could offer a lower-priced alternative to the Northeast Corridor. This, frankly, is nuts.

The operating costs of slower trains are higher than those of faster trains; this is especially true if, as in current plans, the slow trains are not even electrified. Crew, train maintenance, and train acquisition costs all scale with trip time rather than trip distance. Energy costs are dominated by acceleration and deceleration cycles rather than by cruise speed at all speeds up to about 300 km/h. High-speed trains sometimes still manage lower energy consumption per seat-km than slow trains, since slow trains have many acceleration cycles as track speeds change between segments whereas high-speed lines are built for consistent cruise speed.

The only reason to charge less for the trains that are more expensive to operate is to break the market into slow trains for poor people and fast trains for rich people. But this doesn’t generate any value for the customer – it just grabs profits through price discrimination that are then wasted on the higher operating costs of the inferior service. It’s the intercity equivalent of charging more for trains than for buses within a city, which practice is both common in the United States and a big negative to public transit ridership.

If, in contrast, the goal is to provide passengers with good service, then intercity trains to Boston must go via Providence, not Springfield. It’s wise to keep investing in the Shore Line (including bypasses where necessary) to keep providing faster and more convenient service. Creating a class system doesn’t make for good transit at any scale.

Through-Running and American Rail Activism

A bunch of us at the Effective Transit Alliance (mostly not me) are working on a long document about commuter rail through-running. I’m excited about it; the quality of the technical detail (again, mostly not by me) is far better than when I drew some lines on Google Maps in 2009-10. But it gets me thinking – how come through-running is the ask among American technical advocates for good passenger rail? How does it compare with other features of commuter rail modernization?

Note on terminology

In American activist spaces, good commuter rail is universally referred to as regional rail and the term commuter rail denotes peak-focused operations for suburban white flighters who work in city center and only take the train at rush hour. If that’s what you’re used to, mentally search-and-replace everything I say below appropriately. I have grown to avoid this terminology in the last few years, because in France and Germany, there is usually a distinction between commuter rail and longer-range regional rail, and the high standards that advocates demand are those of the former, not the latter. Thus, for me, a mainline rail serving a metropolitan area based on best practices is called commuter and not regional rail; there’s no term for the traditional American system, since there’s no circumstance in which it is appropriate.

The features of good commuter rail

The highest-productivity commuter rail systems I’m aware of – the Kanto area rail network, the Paris RER, S-Bahns in the major German-speaking cities, and so on – share certain features, which can be generalized as best practices. When other systems that lack these features adopt them, they generally see a sharp increase in ridership.

All of the features below fall under the rubric of planning commuter rail as a longer-range subway, rather than as something else, like a rural branch line or a peak-only American operation. The main alternative for providing suburban rapid transit service is the suburban metro, typical of Chinese cities, but the suburban metro and commuter rail models can coexist, as in Stockholm, and in either case, the point is to treat the suburbs as a lower-density, longer-distance part of the metropolitan area, rather than as something qualitatively different from the city. To effect this type of planning, all or nearly all of the following features are required, with the names typically given by advocates:

- Electrification/EMUs: the line must run modern equipment, comprising electric multiple units (self-propelled, with no separate locomotive) for their superior performance and reliability

- Level boarding/standing space: interior train design must facilitate fast boarding and alighting, including many wide doors with step-free boarding (which also provides wheelchair accessibility) and ample standing space within the car rather than just seated space, for example as in Berlin’s new Class 484

- Frequency: the headway between trains set at a small fraction of the typical trip time – neighborhoods 10 km from city center warrant a train every 5-10 minutes, suburbs 20-30 km out a train every 10-20 minutes, suburbs farther out still warrant a train every 20-30 minutes

- Schedule integration: train timetables must be planned in coordination with connecting suburban buses (or streetcars if available) to minimize connection time – the buses should be timed to arrive at each major suburban station just before the train departs, and depart just after it arrives

- Pedestrian-friendliness: train stations designed around connections with buses, streetcars if present, bikes, and pedestrian activity – park-and-rides are acceptable but should be used sparingly, and at stations in the suburbs, the nearby pedestrian experience must come first, in order to make the station area attractive to non-drivers

- Fare integration/Verkehrsverbund: the system may charge higher fares for longer trips, but the transfers to urban and suburban mass transit must be free even if different companies or agencies run the commuter trains and the city’s internal bus and rail system

- Infill: stations should be spaced regularly every 1-3 km within the built-up area, including not just the suburbs but also the city; slightly longer stop spacing may be acceptable if the line acts as an express bypass of a nearby subway line, but not the long stretches of express running American commuter trains do in their central cities

- Through-running: most trains that enter city center go through it, making multiple central stops, and then emerge on the other side to serve suburbs in that direction

Is through-running special?

Among the above features, through-running has a tendency to capture the imagination, because it lends itself to maps of how the lines fit together in the region; I’ve done more than my share of this, in the 2009 post linked in the intro, in 2014, in 2017, and in 2019. This is a useful feature, and in nearly every city with mainline rail, it’s essential to long-term modernization; the exceptions are cities where the geography puts the entirety of suburbia in one direction of city center, and even there, Sydney has through-running (all lines go west of city center) and Helsinki is building a tunnel for it (all lines go north).

The one special thing about through-running is that usually it is the most expensive item to implement, because it requires building new tunnels. In Philadelphia, this was the Center City Commuter Connection, opened in 1984. In Boston, it’s the much-advocated for North-South Rail Link. In Paris, Munich, Tokyo, Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Milan, Madrid, Sydney, Zurich, and other cities that I’m forgetting, this involved building expensive city center tunnels, usually more than one, to turn disparate lines into parts of a coherent metropolitan system. New York is fairly unique in already having the infrastructure for some through-running, and even there, several new tunnels are necessary for systemwide integration.

But there are so many other things that need to be done. In much of the United States, transit advocacy has recently focused on the issue of frequency, brought into the mainstream of advocacy by Jarrett Walker. Doing one without the other leads to awkward situations: after opening the tunnel, Philadelphia branded the lines R1 through R8 modeled on German S-Bahns while still running them hourly off-peak, even within the city, and charging premium fares even right next to overcrowded city buses.

This is something advocates generally understand. There’s a reason the TransitMatters Regional Rail program for commuter rail modernization puts the North-South Rail Link on the back burner and instead focuses on all the other elements. But there’s still something about through-running that lends itself to far more open argumentation than talking about off-peak frequency. Evidently, the Regional Plan Association and other organizations keep posting through-running maps rather than frequency maps or sample timetables.

Through-running as revolution

I suspect one reason for the special place of through-running, besides the attractiveness of drawing lines on a map, is that it most blatantly communicates that this is no longer the old failed system. There are good ways of running commuter rail, and bad ways, and all present-day American commuter rail practices are bad ways.

It’s possible to make asks about modernization that don’t touch through-running, such as integrating the fares; in Germany, the Verkehrsverbund concept goes back to the 1960s and is contemporary with the postwar S-Bahn tunnels, but Berlin and Hamburg had had through-running for decades before. But because these asks look small, it’s easy to compromise them down to nothing. This has happened in Boston, where there’s no fare integration on the horizon, but a handful of commuter rail stations have their fares reduced to be the same as on the subway, still with no free transfers.

Through-running is hard to compromise this way. As soon as the lines exist, they’re out there, requiring open coordination between different railroads, each of which thinks the other is incompetent and is correct. It’s hard to sell it as nothing, and thus it has to be done as a true leap generations forward, catching up with where the best places have been for 50+ years.

Quick Note: New Jersey Highway Widening Alternatives

The Effective Transit Alliance just put out a proposal for how New Jersey can better spend the $10 billion that it is currently planning on spending on highway widening.

The highway widening in question is a simple project, and yet it costs $10.7 billion for around 13 km. I’m unaware of European road tunnels that are this expensive, and yet the widening is entirely above-ground. It’s not even good as a road project – it doesn’t resolve the real bottleneck across the Hudson, which requires rail anyway. It turns out that even at costs that New Jersey Transit thinks it can deliver, there’s a lot that can be done for $10.7 billion:

I contributed to this project, but not much, just some sanity checks on costs; other ETA members who I will credit on request did the heavy pulling of coming up with a good project list and prioritizing them even at New Jersey costs, which are a large multiple of normal costs for rail as well as for highways. I encourage everyone to read and share the full report, linked above; we worked on it in conjunction with some other New Jersey environmental organizations, which supplied some priorities for things we are less familiar with than public transit technicalities like bike lane priorities.

The RENFE Scandal and Responsibility

I’ve been repeatedly asked about a RENFE scandal about its rolling stock purchase. The company ordered trains too big for its rolling stock, and this has been amplified to a scandal that is said to be “incompetence beyond imagination” leading to several high-level resignations, including that of the ministry of transport’s chief civil servant, former ADIF head Isabel Pardo de Vera Posada. In reality, this is a real scandal but not a monumental one, and Pardo de Vera is not at fault; what it does show is both a culture of responsibility and a degree of political deflection.

What is the scandal?

RENFE, the state-owned Spanish rail operating firm, ordered regional trains for service in Asturias and Cantabria on a meter-gauge mountain railway with many narrow tunnels of nonstandard sizes. RENFE did not properly spec out the loading gauge, which vendor CAF noticed in 2021, shortly after the order was tendered but before manufacturing began; thereafter, both tried fixing the error, which has not led to any increase in cost, but has led to a delay in the entry of the under-construction equipment into service from 2024 to 2026.

The head of the regional government of Cantabria, Miguel Ángel Revilla Roiz, demanded that heads roll over the spectacular botch and delay. The context is that regional rail service outside Madrid and Barcelona has been steadily deteriorating, and people outside those two regions have long complained about the domination of the economy and society by those two cities and the depopulation of rural areas. Frequency is low and lines are threatened with closure due to the consequent poor ridership, and there is deep mistrust of the central government (a mistrust that is also common enough in Barcelona, where it is steered toward Catalan nationalism).

The other piece of context is the election at the end of this year. Nearly all polls have the right solidly defeating the incumbent PSOE; Revilla is a PSOE ally and so Asturias head Adrián Barbón Rodríguez is a PSOE member, and both are trying to save their political support by distinguishing themselves from the central government, which is unpopular due to the impact of corona on the Spanish economy.

What is Pardo de Vera’s role?

She was at ADIF when the contract came down; ADIF manages infrastructure, not operations. She was viewed as a consummate technocrat, and I became aware of her work through Roger Senserrich’s interview with her; as such, she was elevated to the position of secretary of state for transport, the chief civil servant in the ministry. Once the ministry became aware of the scandal in 2021, she tried to fix the contract, leading to the current result of a two-year delay; she is now under fire for not having been transparent with the public about it, as the story only became public after a local newspaper broke it.

This needs to be viewed not as incompetence on her part. The scandal is real, but moderate in scope; delays of this magnitude are unfortunately common, and Berlin is having one on the U-Bahn due to vendor lawsuits. Rather, the success of Spain in infrastructure procurement (if not in rail operations, where it unfortunately lags) has created high expectations. In the United States, where standards are the worst, a similar mistake by the MBTA in the ongoing process of procuring electric trains – the RFI did not properly specify the catenary height – is leading to actual increases in costs and it’s not even viewed as a minor problem as in Berlin but as just how expensive electrification is.

I urge Northern European and American agencies to reach out to Pardo de Vera. In Spain she may be perceived as scandalized, but she has real expertise in infrastructure construction, engineering, and procurement. Often boards, steering committees, and review panels comprise retired agency heads who left for a reason; she left for a reason that is not her fault.

Quick Note: Catalunya Station

Barcelona’s commuter rail network has a few distinct components. In addition to the main through-running sections, there are some captive lines terminating at one of two stations, Espanya and Catalunya. Catalunya is especially notable for its very high throughput: the system feeding it, the Barcelona-Vallès Line, has two running tracks, fanning out onto five station tracks, of which only three are used in regular service. Despite the austere infrastructure, the station turns 32 trains per hour on these tracks. I believe this is the highest turnback rate on a commuter rail network. The Chuo Line in Tokyo turns 28 trains per hour on two rather than three tracks but it’s with the same two running tracks as the Catalunya system, and with considerably less branching.

I bring this up because I was under the impression Catalunya turned 24 rather than 32 trains per hour when writing about how Euston could make do with fewer tracks than planned for High Speed 2. But several people since have corrected me, including Shaul Picker (who looked at the timetables) and planning engineer Joan Bergas Massó (who, I believe, wrote them).

The current situation is that the Vallès Line includes both proper commuter lines and metro, sharing tracks. The commuter part of the system comprises two branches, Terrassa carrying S1 and short-turning trains on S7 and Sabadell carrying S2 and short-turning trains on S6; some trains skip stops, but it’s not a consistent pattern in which S1 and S2 run express and S6 and S7 run local. A branch entirely within the city is signed as a metro line, designated L7. Currently, all L7 trains use track 4, turning 8 trains per hour, while the other lines use tracks 1 and 2, turning 24 trains per hour in total.

I stress that while this is a commuter line – it goes into suburbia and descends from a historic steam train rather than a greenfield metro – it is not connected with the mainline network. So it’s easier to turn trains there than on an intricately branched system; the Chuo Line is not as hermetically sealed but is similar in having little other traffic on it than the rapid trains from Tokyo to its in-prefecture western suburbs. Nonetheless, there are multiple branches and stopping patterns; this is not a metro system where all trains are indistinguishable and passengers only care about the interval between trains rather than about the overall schedule.