Category: Urbanism

Trucking and Grocery Prices

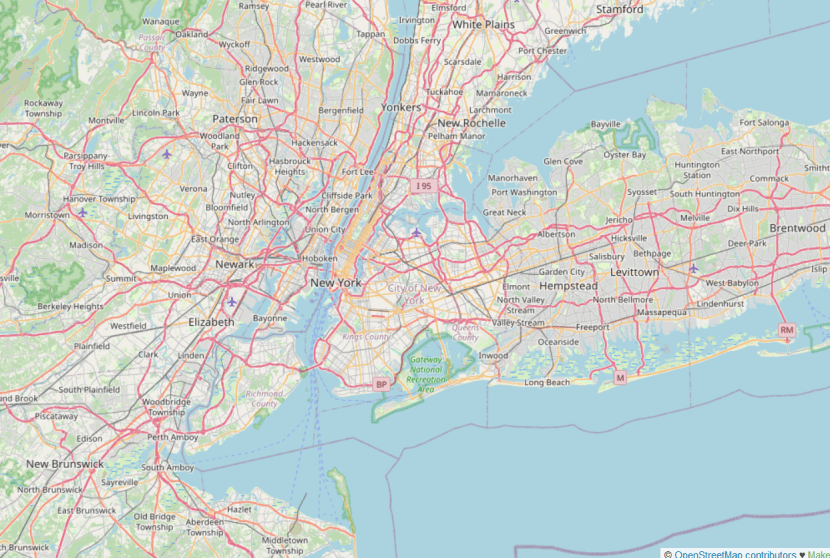

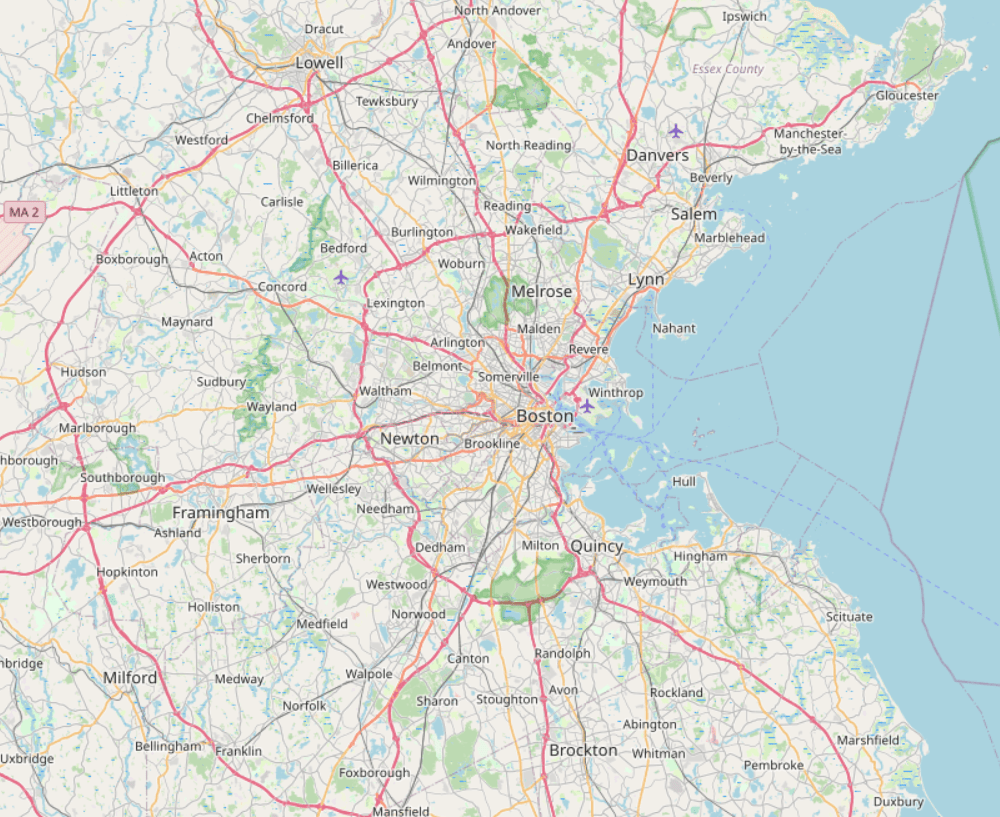

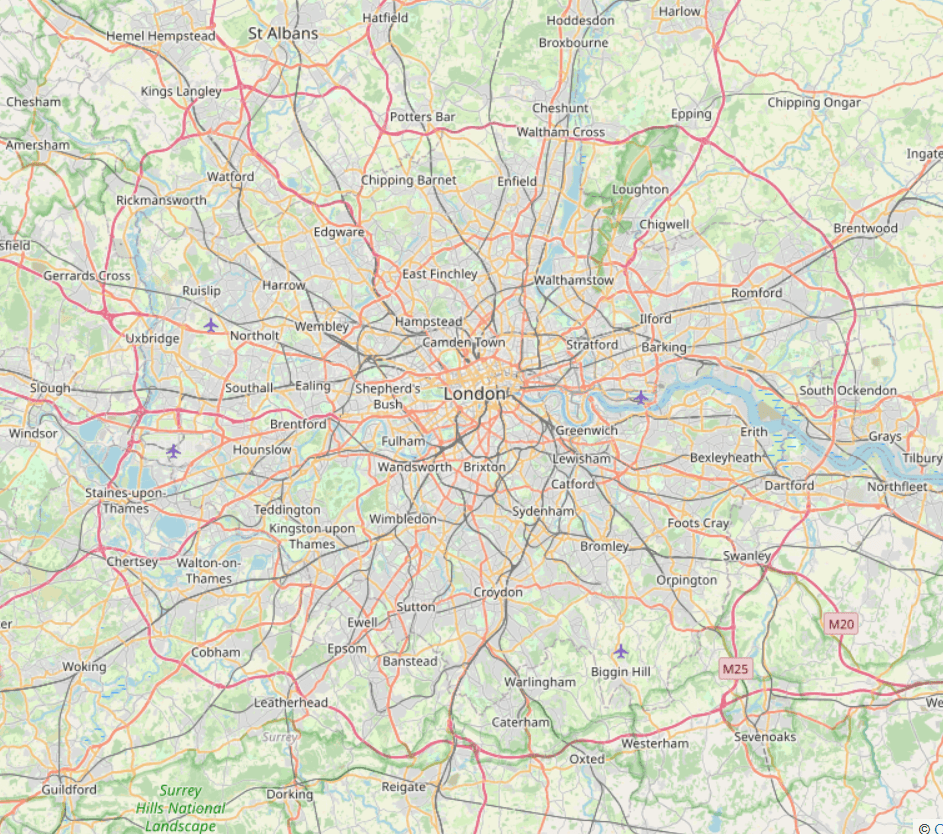

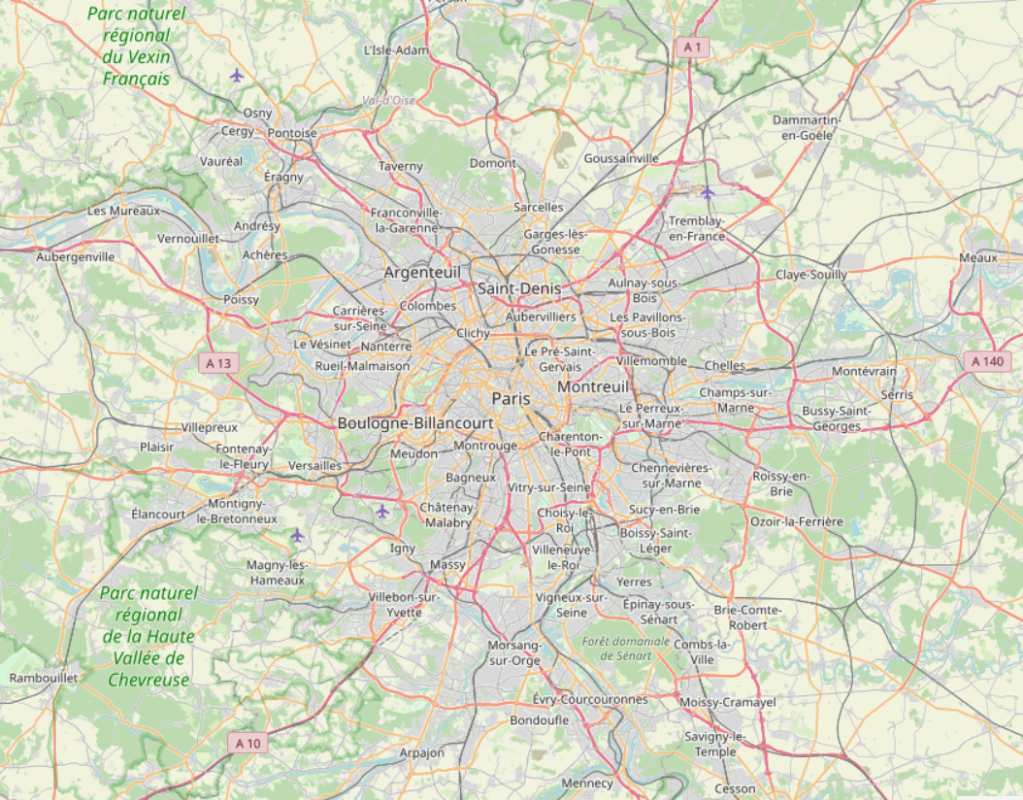

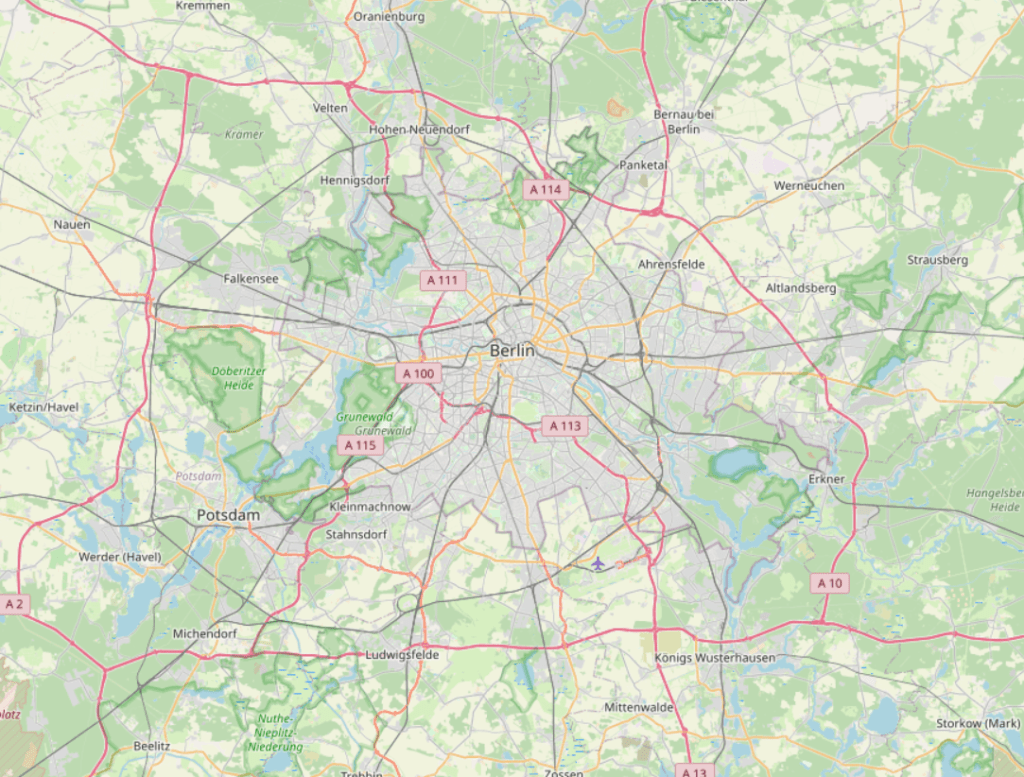

In dedication to people who argue in favor of urban motorways on the grounds that they’re necessary for truck access and cheap consumer goods, here are, at the same scale, the motorway networks of New York, London, Paris, and Berlin. While perusing these maps, note that grocery prices in New York are significantly higher than in its European counterparts. Boston is included as well, for an example of an American city with fewer inherent access issues coming from wide rivers with few bridges; grocery prices in Boston are lower than in New York but higher than in Paris and Berlin (I don’t remember how London compares).

The maps

The scale isn’t exactly the same – it’s all sampled from the same zoom level on OpenStreetMaps; New York is at 40° 45′ N and Berlin is at 52° 30′ N, so technically the Berlin map is at a 1.25 times closer zoom level than the New York map, and the others are in between. But it’s close. Motorways are in red; the Périphérique, delineating the boundary between Paris and its suburbs, is a full freeway, but is inconsistently depicted in red, since it gives right-of-way to entering over through-traffic, typical for regular roads but not of freeways, even though otherwise it is built to freeway standards.

Discussion

The Périphérique is at city limits; within it, 2.1 million people live, and 1.9 million work, representing 32% of Ile-de-France’s total as of 2020. There are no motorways within this zone; there were a few but they have been boulevardized under the mayoralty of Anne Hidalgo, and simultaneously, at-grade arterial roads have had lanes reduced to make room for bike lanes, sidewalk expansion, and pedestrian plazas. Berlin Greens love to negatively contrast the city with Paris, since Berlin is slowly expanding the A100 Autobahn counterclockwise along the Ring (in the above map, the Ring is in black; the under-construction 16th segment of A100 is from the place labeled A113 north to just short of the river), and is not narrowing boulevards to make room for bike lanes. But the A100 ring isn’t even complete, nor is there any plan to complete it; the controversial 17th segment is just a few kilometers across the river. On net, the Autobahn network here is smaller than in Ile-de-France, and looks similar in size per capita. London is even more under-freewayed – the M25 ring encloses nearly the entire city, population 8.8 million, and within it are only a handful of radial motorways, none penetrating into Central London.

The contrast with American cities is stark. New York is, by American standards, under-freewayed, legacy of early freeway revolts going back to the 1950s and the opposition to the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have connected the Holland Tunnel with the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges; see map here. There’s practically no penetration into Manhattan, just stub connections to the bridges and tunnels. But Manhattan is not 2.1 million people but 1.6 million – and we should probably subtract Washington Heights (200,000 people in CB 12) since it is crossed by a freeway or even all of Upper Manhattan (650,000 in CBs 9-12). Immediately outside Manhattan, there are ample freeways, crossing close-in neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, the South Bronx, and Jersey City. The city is not automobile-friendly, but it has considerably more car and truck capacity than its European counterparts. Boston, with a less anti-freeway history than New York, has penetration all the way to Downtown Boston, with the Central Artery, now the Big Dig, having all-controlled-access through-connections to points north, west, and south.

Grocery prices

Americans who defend the status quo of urban freeways keep asking about truck access; this played a role in the debate over what to do about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway’s Downtown Brooklyn section. Against shutting it down, some New Yorkers said, there is the issue of the heavy truck traffic, and where it would go. This then led to American triumphalism about how truck access is important for cheap groceries and other goods, to avoid urban traffic.

And that argument does not survive a trip to a New York (or other urban American) supermarket and another trip to a German or French one. German supermarkets are famously cheap, and have been entering the UK and US, where their greater efficiency in delivering goods has put pressure on local competitors. Walmart, as famously inexpensive as Aldi and Lidl (and generally unavailable in large cities), has had to lower prices to compete. Carrefour and Casino do not operate in the US or UK, and my impression of American urbanists is that they stereotype Carrefour as expensive because they associate it with their expensive French vacations, but outside cities they are French-speaking Walmarts, and even in Paris their prices, while higher, are not much higher than those of German chains in Germany and are much lower than anything available in New York.

While the UK has not given the world any discount retailer like Walmart, Carrefour, or Lidl, its own prices are distinctly lower than in the US, at least as far as the cities are concerned. UK wages are infamously lower than US wages these days, but the UK has such high interregional inequality that wages in London, where the comparison was made, are not too different from wages in New York, especially for people who are not working in tech or other high-wage fields (see national inequality numbers here). In Germany, where inequality is similar to that of the UK or a tad lower, and average wages are higher, I’ve seen Aldi advertise 20€/hour positions; the cookies and cottage cheese that I buy are 1€ per pack where a New York supermarket would charge maybe $3 for a comparable product.

Retail and freight

Retail is a labor-intensive industry. Its costs are dominated by the wages and benefits of the employees. Both the overall profit margins and the operating income per employee are low; increases in wages are visible in prices. If the delivery trucks get stuck in traffic, are charged a congestion tax, have restricted delivery hours, or otherwise have to deal with any of the consequences of urban anti-car policy, the impact on retail efficiency is low.

The connection between automobility and cheap retail is not that auto-oriented cities have an easier time providing cheap goods; Boston is rather auto-oriented by European standards and has expensive retail and the same is true of the other secondary transit cities of the United States. Rather, it’s that postwar innovations in retail efficiency have included, among other things, adapting to new mass motorization, through the invention of the hypermarket by Walmart and Carrefour. But the main innovation is not the car, but rather the idea of buying in bulk to reduce prices; Aldi achieves the same bulk buying with smaller stores, through using off-brand private labels. In the American context, Walmart and other discount retailers have with few exceptions not bothered providing urban-scale stores, because in a country with, as of 2019, a 90% car modal split and a 9% transit-and-active-transportation modal split for people not working from home, it’s more convenient to just ignore the small urban patches that have other transportation needs. In France and Germany, equally cheap discounters do go after the urban market – New York groceries are dominated by high-cost local and regional chains, Paris and Berlin ones are dominated by the same national chains that sell in periurban areas – and offer low-cost goods.

The upshot is that a city can engage in the same anti-car urban policies as Paris and not at all see this in retail prices. This is especially remarkable since Paris’s policies do not include congestion pricing – Hidalgo is of the opinion that rationing road space through prices is too neoliberal; normally, congestion pricing regimes remove cars used by commuters and marginal non-commute personal trips, whereas commercial traffic happily pays a few pounds to get there faster. Even with the sort of anti-car policies that disproportionately hurt commercial traffic more than congestion pricing, Paris has significantly cheaper retail than New York (or Boston, San Francisco, etc.).

And Berlin, for all of its urbanist cultural cringe toward Paris, needs to be classified alongside Paris and not alongside American cities. The city does not have a large motorway network, and its inner-urban neighborhoods are not fast drive-throughs. And yet in the center of the city, next to pedestrian plazas, retailers like Edeka and Kaufland charge 1€ for items that New York chains outside Manhattan sell for $2.5-4. Urban-scale retail deliveries are that unimportant to the retail industry.

How Residential is a Residential Neighborhood?

Last post, I brought up the point that the neighborhoods along the Interborough Express corridor in New York are residential. An alert commenter, Teban54transit, pointed out that this should weaken the line, since subway lines should connect residential neighborhoods with destinations and not just with other residential neighborhoods. To explain why this is not a major problem in this case, I’d like to go over what exactly is a residential neighborhood and what exactly is a destination. In short, a predominantly residential neighborhood may still have other functional uses, turning it into a destination. It’s imperfect in the case of IBX, but the relative ease of using the right-of-way makes the line still viable.

Residential-but-mixed neighborhoods

Residential neighborhoods always have nonresidential uses, serving the local population: supermarkets, schools, doctors’ offices, restaurants, pharmacies, clothing stores. These induce very few trips from out of the neighborhood, normally. But things are not always normal, and some residential areas end up getting a cluster of destinations.

In New York, the most common way such a cluster can form is as an ethnic center, including Harlem and several Chinatowns. People in and around New York travel to Harlem for specifically black cultural events, for example the shows at the Apollo Theater; they travel to Chinatown and Flushing for Chinese restaurants and supermarkets. Usually the people who so travel are members of the same ethnic community who live elsewhere; this way, in Washington Metro origin-and-destination travel data, one can see a few hundred extra trips a day between black neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River and Columbia Heights, whereas no noticeable bump is seen in work trips between those two areas on OnTheMap.

On the IBX route, this is Jackson Heights. It’s on net a bedroom community, whereas Flushing has within 1 km of Main and Roosevelt 43,000 jobs and 29,000 employed residents, but such ethnic cultural centers over time grow into destinations. People travel to the neighborhood for Indian restaurants, groceries, and cultural events, and it’s likely that over time the area will also get more professional services that cater to the community, creating more non-work and work destinations. The growth of Flushing as a job center is recent and has to be understood as part of this process: in 2007, on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis, there were only 17,000 jobs within 1 km of Main and Roosevelt. Jackson Heights, too, has seen growth in jobs from 2007 to 2019, though much less, by 27%, or 50% excluding Elmhurst Hospital, which over this period saw a small decrease in jobs.

Not only ethnic neighborhoods have this pattern. A neighborhood can grow to become mixed out of proximity to a business district, for example the Village, or out of a particular destination, for example anything near a university. On IBX, there’s nothing like the Village or Long Island City, but Brooklyn College is a destination in and of itself.

Building neighborhood-scale destinations

New public transit lines can help build neighborhoods into destinations. At the centers of cities, central business districts and rapid transit systems tend to co-evolve with each other: a high degree of centralization creates demand for more lines as the only way to truly serve all of those jobs, while a larger rapid transit system in turn can encourage the growth of city center as the place best served by the network. The same is true for secondary centers and junctions of other lines.

This, to be clear, is not a guarantee. Broadway Junction is very easily accessible by public transportation from a large fraction of New York. It’s also more or less the poorest area of the city, where working-class Bangladeshi immigrants living several to a room to save money on rent are considered a sign of gentrification and growth in rent. Adding IBX there is unlikely to change this situation.

But in Jackson Heights and around Brooklyn College, a change is more likely. Jackson Heights already has large numbers of residents using the radial subway lines to get to Manhattan for work, and a growing number of nonresidents who use its specialized businesses and cultural events. The latter group is the greatest beneficiary from circumferential transit, if it connects to the radial lines well; strong radial transit is a prerequisite, but in Jackson Heights, there already is such transit. Brooklyn College is already a destination, in a neighborhood that’s much better off than East New York and already draws widely because of the university trips; I expect that rapid transit service in three directions, up from the one direction available today (toward Manhattan), would encourage the growth of university-facing amenities, which generate their own trips.

Where to build circumferential rail

The best alignment for circumferential rail remains one that connects strong secondary destinations. However, that is strictly in theory, because usually such destinations don’t form a neat circle around city center, especially not in a city so divided by water like New York. If we were to draw the strongest secondary destinations in the city outside the Manhattan core excluding Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City on the G, we’d get Morningside Heights for Columbia (centered on 116th), maybe 125th Street, the Bronx Hub, LaGuardia, Flushing, Jamaica, and Kings County Hospital/SUNY Downstate. These barely even form a coherent line if dug entirely underground by tunnel boring machine, diagonally under private blocks. And this is without taking into account destinations in New Jersey on the waterfront, which don’t form any neat circle with those city destinations (for example, Fort Lee is well to the north of Morningside Heights and Harlem).

In practice, then, circumferential lines have to go where it is possible, making compromises along the way. This is why it’s so important to connect to every radial, with as short a walk as practical: they never connect the strongest destinations and therefore have to live off of transfers. The G, which does connect the two largest job centers in the region outside Manhattan, fails because of the poor transfers. IBX works as a compromise alignment, connecting to interesting secondary destinations, with transfers to the most important ones, like Flushing and Jamaica. It is fortunate that the route is not purely residential: the neighborhoods are all on net bedroom communities, but some have the potential to grow to be more than that through both processes that are already happening and ones that good rapid transit can unlock.

Land Use Around the Interborough Express

Eric and Elif are working on a project to analyze land use around the corridor of the planned Interborough Express line in New York. The current land use is mostly residential, and a fascinating mix of densities. This leads to work on pedestrian, car, and transit connectedness, and on modal split. As might be expected, car ownership is fairly high along the corridor, especially near the stations that are not at all served by the subway today, as opposed to ones that are only served by radial lines. Elif gave a seminar talk about the subject together with João Paulouro Neves, and I’d like to share some highlights.

The increase in transit accessibility in the above map is not too surprising, I don’t think. Stations at both ends of the line gain relatively little; the stations that gain the most are ones without subway service today, but Metropolitan Avenue, currently only on the M, gains dramatically from the short trip to Roosevelt with its better accessibility to Midtown.

More interesting than this, at least to me, is the role of the line as a way to gradually push out the boundary between the transit- and auto-oriented sections of the city. For this, we should look at a density map together with a modal split map.

At the seminar talk, Elif described IBX as roughly delineating the boundary between the auto- and transit-oriented parts of the city, at least in Brooklyn. (In Queens, the model is much spikier, with ribbons of density and transit ridership along subway lines.) This isn’t quite visible in population density, but is glaring on the second map, of modal split.

Now, to be clear, it’s not that the IBX route itself is a boundary. The route is not a formidable barrier to pedestrian circulation: there are two freight trains per day in each direction, I believe, which means that people can cross the trench without worrying about noise the way they do when crossing a freeway. Rather, it’s a transitional zone, with more line density to the north and less to the south.

The upshot is that IBX is likely to push this transitional zone farther out. There is exceptionally poor crosstown access today – the street network is slow, and while some of the crosstown Brooklyn buses are very busy, they are also painfully slow, with the B35 on Church Avenue, perennially a top 10 route in citywide ridership, winning the borough-wide Pokey Award for its slowness. So we’re seeing strong latent demand for crosstown access in Brooklyn with how much ridership these buses have, and yet IBX is likely to greatly surpass them, because of the grade-separated right-of-way. With such a line in place, it’s likely that people living close to the line will learn to conceive of the subway system plus the IBX route as capable of connecting them in multiple directions: the subway would go toward and away from Manhattan, and IBX orthogonally, providing enough transit accessibility to incentivize people to rely on modes of travel other than the car.

This is especially important since the city’s street network looks differently by mode. Here is pedestrian integration by street:

And here is auto integration:

The auto integration map is not strongly centered the way the pedestrian map is. Quite a lot of the IBX route is in the highest-integration zone, that is with the best access for cars, but the there isn’t really a single continuous patch of high integration the way Midtown Manhattan is the center of the pedestrian map. East Williamsburg has high car integration and is not at all an auto-oriented area; I suspect it has such high integration because of the proximity to the Williamsburg and Kosciuszko Bridges but also to Grand Street and Metropolitan Avenue toward Queens, and while the freeways are zones of pedestrian hostility, Grand and Metropolitan are not.

What this means is that the red color of so many streets along the IBX should not by itself mean the area will remain auto-oriented. More likely, the presence of the line will encourage people to move to the area if they intend to commute by train, and I suspect this will happen even at stations that already have service to Manhattan and even among people who work in Manhattan. The mechanism here is that a subway commuter chooses where to live based on commuter convenience but also access to other amenities, and being able to take the train (for example) from Eastern Brooklyn to Jackson Heights matters. It’s a secondary effect, but it’s not zero. And then for people commuting to Brooklyn College or intending to live at one of the new stops (or at Metropolitan, which has Midtown access today but not great access), it’s a much larger effect.

The snag is that transit-oriented development is required. To some extent, the secondary effect of people intending to commute by train coming to the neighborhood to commute from it can generate ridership by itself; in the United States, all ridership estimates assume no change in zoning, due to federal requirements (the Federal Transit Administration has been burned before by cities promising upzoning to get funding for lines and then not delivering). But then transit-oriented development can make it much more, and much of the goal of the project is to recommend best practices in that direction: how to increase density, improve pedestrian accessibility to ensure the areas of effect become more rather than less walkable, encourage mixed uses, and so on.

Worthless Canadian Initiative

Canada just announced a few days ago that it is capping the number of international student visas; the Times Higher Education and BBC both point out that the main argument used in favor of the cap is that there’s a housing shortage in Canada. Indeed, the way immigration politics plays out in Canada is such that the cap is hard to justify by other means: traditionally, the system there prioritized high-skill workers, to the point that there has been conservative criticism of the Trudeau cabinet for greatly expanding low-skill (namely, refugee) migration; capping student visas is not how one responds to such criticism.

The issue is that Canada builds a fair amount of housing, but not enough for population growth; the solution is to build more – in a fast-growing country like Canada, the finance sector expects housing demand to grow and therefore will readily build more if it is allowed to.

Vancouver deserves credit for the quality of its transit-oriented development and to a large extent also for the amount of absolute development it permits (about 10 units per 1,000 residents annually); but its ability to build is much greater than that, precisely because rapid immigration means that more housing is profitable, even at higher interest rates. The population growth coming from immigration sends a signal to the market, invest in long-term tangible goods like housing. Thus, Vancouver deserves less credit for its permissiveness of development – large swaths of the city are zoned for single-family housing with granny flats allowed, including in-demand West Side neighborhoods with good access to UBC and Downtown jobs by current buses and future SkyTrain.

The rub is that restricting student immigration is probably the worst possible way to deal with a housing shortage. Students live at high levels of crowding, and the marginal students, who the visa cap is excluding, live at higher levels of crowding than the rest because they tend to be at poorer universities and from poorer backgrounds. The reduction in present-day demand is limited. In Vancouver, an empty nester couple with 250 square meters of single-family housing in Shaughnessy is consuming far more housing, and sitting on far more land that could be redeveloped at high density, than four immigrants sharing a two-bedroom apartment in East Vancouver.

In contrast, the reduction in future demand is substantial, because those students then graduate and get work, and many of them get high-skill, high-wage jobs (the Canadian university graduate premium is declining but still large; the American one is larger, but the US is also a higher-inequality society in general); having fewer students, even fewer marginal students who might take jobs below their skill level, is still a reduction in both future population and future productivity. What this means is that capital owners deciding where to allocate assets are less likely to be financing construction.

The limiting factor on housing production is to a large extent NIMBYism, and there, in theory, immigration restrictions are neutral. (In practice, they can come out of a sense of national greatness developmental conservatism that wants to build a lot but restrict who can come in, or out of anti-developmental NIMBYism that feels empowered to build less as fewer people are coming; this situation is the latter.) However, it’s not entirely NIMBYism – private developmental still has to be profitable, and judging by the discourse I’m seeing on Canadian high-rise housing construction costs in Toronto and Vancouver, it’s not entirely a matter of permits. Even in an environment with extensive NIMBYism like the single-family areas of Vancouver and Toronto, costs and future profits matter.

The Need for Ample Zoning Capacity

An article by Vishaan Chakrabarti in last month’s New York Times about how to make room for a million more people in New York reminded me of something that YIMBY blogs a decade ago were talking about, regarding zoning capacity. Chakrabarti has an outline of where it’s possible to add housing under the constraints that it must be within walking distance of the subway, commuter rail, or Staten Island Railway, and that it must be of similar height to the preexisting character of the neighborhood. With these constraints, it’s possible to find empty lots, parking lots, disused industrial sites, and (in near-Midtown Manhattan) office buildings for conversion, allowing adding about half a million dwellings in the city. It’s a good exercise – and it’s a great explanation for why those constraints, together, make it impossible to add a meaningful quantity of housing. Transit-oriented development successes go far beyond these constraints and build to much higher density than is typical in their local areas, which can be mid-rise (in Europe) or high-rise (in Canada and Asia).

The issue with the proposal is that in practice, not all developable sites get developed. The reasons for this can include any of the following:

- The parcel owner can’t secure capital because of market conditions or because of the owner’s particular situation.

- The parcel is underdeveloped but not empty, and the owner chooses not to redevelop, for a personal or other reason.

- The area is not in demand, as is likely the case near the Staten Island Railway or commuter rail stations in Eastern Queens, or in much of the Bronx.

- The area is so auto-oriented, even if it is technically near a station, that prospective buyers (and banks) demand parking, reducing density.

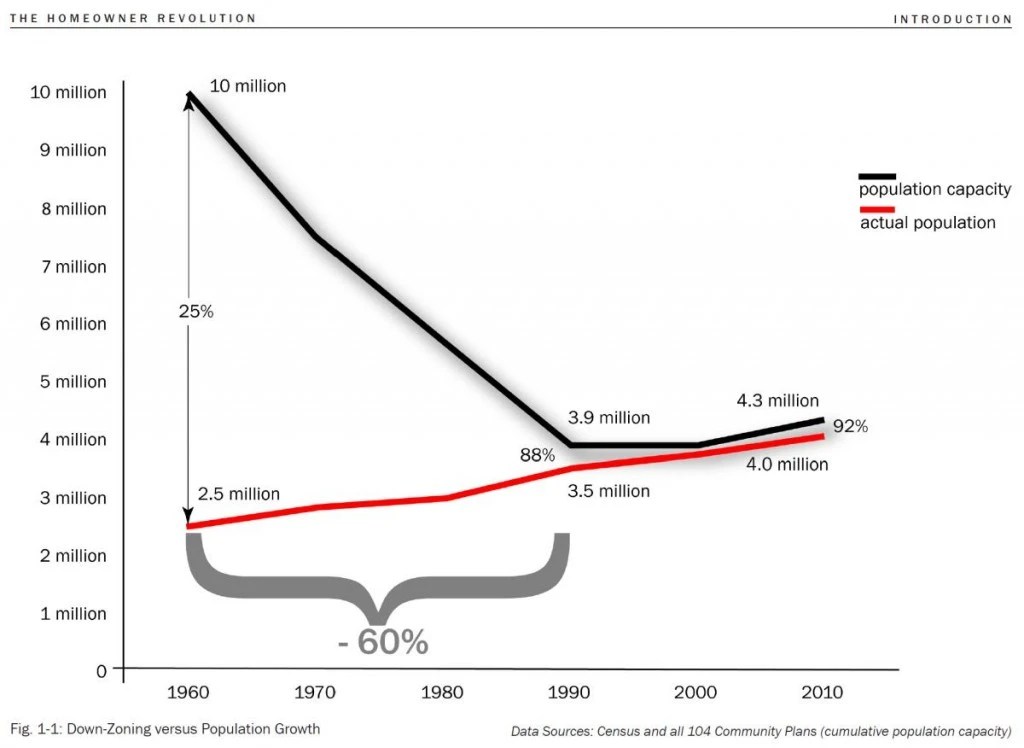

New York has, on 2020 census numbers, 8.8 million people; 1 million additional New Yorkers is 11% more people. Cities that permit a lot of housing have an envelope for much more than 11% extra population. In New York’s history, it was computed in 1956 that under the then-current 1916 zoning code, the city’s zoned capacity was 55 million people, but under the proposed code that would be enacted in 1961, the zoned capacity would fall to 12 million. In Los Angeles, The Homeowner Revolution makes the point (on PDF-page 19) that in 1960, zoned capacity was 10 million in the city proper, four times the city’s population, but by 1990 it fell to 3.9 million, 11% more than the city’s population.

Technically, the same extra zoned capacity that Chakrabarti finds for New York has existed in Los Angeles for a generation. In practice, for all the above reasons why development never reaches 100% of capacity even in expensive areas, Los Angeles builds very little housing, and rents are very high, perhaps comparable to those of New York even as wages are much lower.

What this means is that the way forward for any transit-oriented development plan has to get out of the mentality that the buildings need to be of similar size to the existing character of the neighborhood. This constraint is too strict, and not at all observed in any successful example that I know of.

To Americans, the most accessible example of transit-oriented development success is Vancouver; some sections of the Washington suburbs (especially Arlington) qualify as well, but the extent there is much less than in Canada, and consequently ridership on Washington Metro has lagged that of its Canadian counterparts. In Vancouver, the rule that Chakrabarti imposes that the preexisting parcels must be empty or nonresidential is largely observed – as far as I can tell, the city has not upzoned low-density residential areas near SkyTrain, and even in Burnaby, the bulk of redevelopment has been in nonresidential areas.

The redevelopment in Vancouver proper looks like this:

And here is Metrotown, Burnaby:

The surface parking may look obnoxious to urbanists, but the area has more jobs, retail, and housing than the parking lots can admit, and the modal split is very high.

European transit-oriented development is squatter – the buildings are generally less tall, and they’re spread over a larger contiguous area, so that beyond the resolution of a few blocks the density is high as well. But it, too, often grows well beyond tradition. For example, here is Bercy, a redevelopment of the steam-era railyards at Gare de Lyon, no longer necessary with modern rail technology:

In the future, a New York that wants to make more room will need to do what Vancouver and Paris did. There is no other way.

Quick Note: Different Anti-Growth Green Advocacies

Jerusalem Demsas has been on a roll in the last two years, and her reporting on housing advocacy in Minneapolis (gift link) is a great example of how to combine original reporting with analysis coming from understanding of the issue at hand. In short, she talks to pro- and anti-development people in the area, both of which groups identify with environmentalism and environmental advocacy, and hears out their concerns. She has a long quote by Jake Anbinder, who wrote his thesis on postwar American left-NIMBYism and its origins, which are a lot more good-faith than mid-2010s YIMBYs assumed; he points out how they were reacting to postwar growth by embracing what today would be called degrowth ideology.

I bring this up because Germany is full of anti-growth left-NIMBYism, with similar ideology to what she describes from her reporting in Minneapolis, but it has different transportation politics, in ways that matter. The positioning of German left-NIMBYs is not pro-car; it has pro-car outcomes, but superficially they generally support transportation alternatives, and in some cases they do in substance as well.

In the US, the left-NIMBYs are drivers. Jerusalem cites them opposing bike lanes, complaining that bike lanes are only for young childless white gentrifiers, and saying that soon electric cars will solve all of the problems of decarbonizing transportation anyway. I saw some of this myself while advocating for rail improvements in certain quarters in New England: people who are every stereotype of traditional environmental left-NIMBYism were asking us about parking at train stations and were indifferent to any operating improvements, because they don’t even visit the city enough to think about train frequency and speed.

In Germany, many are drivers, especially outside the cities, but they don’t have pro-car politics. The Berlin Greens, a thoroughly NIMBY party, are best known in the city for supporting removal of parking and moving lanes to make room for bike lanes. This is not unique to Berlin or even to Germany – the same New Left urban mayors who do little to build more housing implement extensive road diets and dedicated lanes for buses, streetcars, and bikes.

These same European left-NIMBYs are not at all pro-public transportation in general. They generally oppose high-speed rail: the French greens, EELV, oppose the construction of new high-speed lines and call for reducing the speed on existing ones to 200 km/h, on the grounds that higher speeds require higher electricity consumption. In Germany, they usually also oppose the construction of new subway and S-Bahn tunnels. Their reasons include the embedded carbon emissions of tunneling, a belief that the public transport belongs on the street (where it also takes room away from cars) and not away from the street, and the undesirability (to them) of improving job access in city center in preference to the rest of the city. However, they usually consistently support more traditional forms of rail, especially the streetcar and improvements to regional rail outside major cities. For example, the NIMBYs in Munich who unsuccessfully fought the second S-Bahn trunk line, whence the expression Organisation vor Elektronic vor Beton (the Swiss original omits Organisation and also is very much “before” and not “instead of”), called for improvements in frequency on lines going around city center, in preference to more capacity toward city center.

I’m not sure why this difference works like this. I suspect it’s that American boomer middle-class environmental NIMBYism is rooted in people who suburbanized in the postwar era or grew up in postwar suburbs, and find the idea of driving natural. The same ideology in Europe centers urban neighborhood-scale activism more, perhaps because European cities retained the middle class much better than their American ones, perhaps because mass motorization came to Europe slightly later. It also centers small towns and cities, connected to one another by regional rail; the underlying quality of public transportation here is that environmentalists who can afford better do rely on it even when it’s not very good, which hourly regional trains are not, whereas in the United States it’s so far gone that public transportation ridership comprises New Yorkers, commuters bound for downtown jobs in various secondary cities, and paupers.

Quick Note: New Neighborhoods are Residential

There’s a common trope about a new exurban subdivision with nothing but houses, and living in a new building in a relatively new urban neighborhood, I get it. Of course, where I live is dense and walkable – it’s literally in Berlin-Mitte – but it still feels underserved by retail and other neighborhood-scale amenities. But at the same time, those amenities are starting to catch up, following the new residences.

I’ve known since I moved here that the place is pessimally located relative to supermarkets. My previous apartment, in Neukölln, was on a residential street, across the corner from a Penny’s, and about 600 meters from the Aldi on the other side of the Ring and 700 from a Lidl that I went to maybe twice in the year I was there because I thought it was too far. My current place was around 800 meters from the nearest supermarket when I moved here in 2020; very recently a slightly closer Bio Company has opened, with not great selection. Other services seem undersupplied as well, like restaurants, which Cid and I have become acutely aware of as the temperature crossed -5 degrees in the wrong direction. For other stores, we typically have to go to Alexanderplatz or Kottbusser Tor.

I bring this up not to complain – I knew what I was getting into when I rented this place. Rather, I bring this up because I’m seeing this combination of not great neighborhood-scale services and gradual change bringing such services in. The gradual change doesn’t seem like a coincidence – the new things I’ve seen open here in the last 3.5 years are high-end, like the aforementioned Bio Company store, or some yuppie cafes, are exactly what you’d open to cater to people living in new buildings in Berlin.

And that brings me back to the common stereotype of new subdivisions. All they have is residential development. This is not just about exurbia, because I’m seeing this here, in the middle of the city. It’s not even just about capitalist development, because it can also be seen in top-down construction of new neighborhoods: the Million Program suburban housing projects around Stockholm were supposed to be work-live areas, like pre-Million Program Vällingby, but they turned into bedroom communities, because it was more desirable to locate commercial uses in city center or near key T-bana stations.

This is true even when the new development is not purely residential, which the development here isn’t. There are office buildings, including one being built right as we speak. But these, too, take time to bring in neighborhood-scale amenities, and those amenities, in turn, are specific to office workers, leading to a number of cafes that only open around lunch hours.

If anything, the fact that this is infill showcases how this is not so bad when a city develops through accretion of new buildings, in this case as new land becomes available (this is all in the exclusion zone near the Wall), but often also on the margin of the city as it gets a new subway line or as land near its periphery becomes valuable enough to develop. There are a lot of services a walk away; it’s not an especially short walk, but what I get within a 1 km radius is decent and what I get within 1.5 is very good to the point that we still discover new things within that radius of an apartment I’ve lived in for 3.5 years.

And in a way, the archetypical new suburban subdivision often has the same ability to access neighborhood-scale amenities early, just with a snag that they’re farther away than is desirable. It involves driving 10-15 minutes to the strip mall, but in new suburban subdivisions other than the tiny handful that are transit-oriented development, it’s assumed everyone has a car; why else would one even live there? (At the ones that are transit-oriented, early residents can take the train to places with more retail development, which a lot of people do even in mature neighborhoods for more specialized amenities.)

Reverse- and Through-Commute Trends

I poked around some comparable data for commuting around New York for 2007 and 2019 the other day, using OnTheMap. The motivation is that I’d made two graphics of through-commutes in the region, one in 2017 (see link here, I can’t find the original article anymore) and one this year for the ETA report (see here, go to section 2B). The nicer second graphic was made by Kara Fischer, not by me, but also has about twice the volume of through-commutes, partly due to a switch in source to the more precise OnTheMap, partly due to growth. It’s the issue of growth I’d like to go over in this post.

In all cases, I’m going to compare data from 2007 and 2019. This is because these years were both business cycle peaks, and this is the best way to compare data from different years. The topline result is that commutes of all kinds are up – the US had economic growth in 2007-19 and New York participated in it – but cross-regional commutes grew much more than commutes to Manhattan. New Jersey especially grew as a residential place, thanks to its faster housing growth, to the point that by 2019, commute volumes from the state to Manhattan matched those of all east-of-Hudson suburbs combined. The analysis counts all jobs, including secondary jobs.

For the purposes of the tables below, Long Island comprises Nassau and Suffolk Counties, and Metro-North territory comprises Westchester, Putnam, and Duchess Counties and all of Connecticut.

2007 data

| From\To | Manhattan | Brooklyn | Queens | Bronx | Staten Island | Long Island | Metro-North | New Jersey |

| Manhattan | 449,308 | 30,716 | 22,028 | 17,746 | 1,974 | 17,574 | 20,281 | 29,031 |

| Brooklyn | 385,943 | 299,056 | 76,499 | 16,121 | 9,288 | 40,847 | 17,175 | 25,887 |

| Queens | 328,785 | 89,982 | 216,988 | 19,227 | 4,350 | 107,634 | 21,737 | 18,555 |

| Bronx | 184,594 | 35,994 | 29,818 | 97,397 | 2,337 | 20,200 | 41,316 | 15,467 |

| Staten Island | 59,572 | 30,241 | 7,223 | 2,326 | 49,679 | 7,514 | 3,655 | 17,919 |

| Long Island | 163,988 | 45,121 | 77,337 | 12,724 | 5,103 | 926,912 | 32,806 | 12,557 |

| Metro-North | 124,952 | 12,606 | 14,228 | 24,131 | 1,962 | 29,344 | 1,897,392 | 15,413 |

| New Jersey | 245,373 | 23,455 | 17,496 | 11,022 | 8,109 | 17,460 | 22,073 | 3,523,860 |

2019 data

| From\To | Manhattan | Brooklyn | Queens | Bronx | Staten Island | Long Island | Metro-North | New Jersey |

| Manhattan | 570,321 | 56,019 | 44,063 | 31,947 | 4,000 | 20,678 | 22,146 | 35,243 |

| Brooklyn | 486,757 | 429,234 | 119,588 | 26,192 | 17,073 | 43,410 | 18,301 | 33,119 |

| Queens | 384,186 | 134,063 | 308,903 | 36,339 | 7,640 | 121,194 | 25,216 | 22,863 |

| Bronx | 224,583 | 62,377 | 58,124 | 135,288 | 4,364 | 26,172 | 45,347 | 17,387 |

| Staten Island | 59,778 | 40,994 | 13,971 | 5,218 | 56,953 | 9,877 | 3,510 | 19,442 |

| Long Island | 191,239 | 59,241 | 102,939 | 23,246 | 8,132 | 971,193 | 40,130 | 14,724 |

| Metro-North | 153,482 | 21,283 | 23,498 | 37,147 | 3,179 | 40,586 | 1,874,618 | 20,819 |

| New Jersey | 345,551 | 40,397 | 29,523 | 17,467 | 14,134 | 23,439 | 29,755 | 3,614,386 |

Growth

| From\To | Manhattan | Brooklyn | Queens | Bronx | Staten Island | Long Island | Metro-North | New Jersey |

| Manhattan | 26.93% | 82.38% | 100.03% | 80.02% | 102.63% | 17.66% | 9.20% | 21.40% |

| Brooklyn | 26.12% | 43.53% | 56.33% | 62.47% | 83.82% | 6.27% | 6.56% | 27.94% |

| Queens | 16.85% | 48.99% | 42.36% | 89.00% | 75.63% | 12.60% | 16.00% | 23.22% |

| Bronx | 21.66% | 73.30% | 94.93% | 38.90% | 86.74% | 29.56% | 9.76% | 12.41% |

| Staten Island | 0.35% | 35.56% | 93.42% | 124.33% | 14.64% | 31.45% | -3.97% | 8.50% |

| Long Island | 16.62% | 31.29% | 33.10% | 82.69% | 59.36% | 4.78% | 22.33% | 17.26% |

| Metro-North | 22.83% | 68.83% | 65.15% | 53.94% | 62.03% | 38.31% | -1.20% | 35.07% |

| New Jersey | 40.83% | 72.23% | 68.74% | 58.47% | 74.30% | 34.24% | 34.80% | 2.57% |

Some patterns

Commutes to Manhattan are up 24.37% over the entire period. This is actually higher than the rise in all commutes in the table combined, because of the weight of intra-suburban commutes (internal to New Jersey, Metro-North territory, or Long Island), which stagnated over this period. However, the rise in all commutes that are not to Manhattan and are also not internal to one of the three suburban zones is much greater, 41.11%.

This 41.11% growth was uneven over this period. Every group of commuters to the suburbs did worse than this. On net, commutes to New Jersey, Metro-North territory, and Long Island, each excluding internal commutes, grew 21.34%, 15.95%, and 18.62%, all underperforming commutes to Manhattan. Some subgroups did somewhat better – commutes from New Jersey and Metro-North to the rest of suburbia grew healthily (they’re the top four among the cells describing commutes to the suburbs) – but overall, this isn’t really about suburban job growth, which lagged in this period.

In contrast, commutes to the Outer Boroughs grew at a collective rate of 50.31%. All four intra-borough numbers (five if we include Manhattan) did worse than this; rather, people commuted between Outer Boroughs at skyrocketing rates in this period, and many suburbanites started commuting to the Outer Boroughs too. Among these, the cis-Manhattan commutes – Long Island to Brooklyn and Queens, and Metro-North territory to the Bronx – grew less rapidly (31.29%, 33.1%, 53.94% respectively), while the trans-Manhattan commutes grew very rapidly, New Jersey-Brooklyn growing 72.23%.

New Jersey had especially high growth rates as an origin. Not counting intra-state commutes, commutes as an origin grew 45% (Long Island: 25.75%; Metro-North territory: 34.75%), due to the relatively high rate of housing construction in the state. By 2019, commutes from New Jersey to Manhattan grew to be about equal in volumes to commutes from the two east-of-Hudson suburban regions combined.

Overall, trans-Hudson through-commutes – those between New Jersey and anywhere in the table except Manhattan and Staten Island – grew from 179,385 to 249,493, 39% in total, with New Jersey growing much faster as an origin than a destination for such commutes (53.63% vs. 23.93%); through-commutes between the Bronx or Metro-North territory and Brooklyn grew 56.48%, reaching 128,153 people, with Brooklyn growing 72.13% as a destination for such commutes and 33.63% as an origin.

What this means for commuter rail

Increasingly, through-running isn’t about unlocking new markets, although I think that better through-service is bound to increase the size of the overall commute volume. Rather, it’s about serving commutes that exist, or at least did on the eve of the pandemic. About half of the through-commutes are to Brooklyn, the Bronx, or Queens; the other half are to the suburbs (largely to New Jersey).

The comparison must be with reverse-commutes. Those are also traditionally ignored by commuter rail, but Metro-North made a serious effort to accommodate the high-end ones from the city to edge cities including White Plains, Greenwich, and Stamford, where consequently transit commuters outearn drivers in workplace geography. The LIRR, which long ran its Main Line one-way at rush hour to maintain express service on the two-track line, sold the third track project as opening new reverse-commutes. But none of these markets is growing much, and the only cis-Manhattan one that’s large is Queens to Long Island, which has an extremely diffuse job geography. In contrast, the larger and faster-growing through-markets are ignored.

Short (cis-Manhattan) trips are growing healthily too. They are eclipsed by some through-commutes, but Long Island to Queens and Brooklyn and Metro-North territory to the Bronx all grew very fast, and at least for the first two, the work destinations are fairly clustered near the LIRR (but the Bronx jobs are not at all clustered near Metro-North).

The fast job growth in all four Outer Boroughs means that it’s better to think of commuter rail as linking the suburbs with the city than just linking the suburbs with Penn Station or Grand Central. There isn’t much suburban job growth, but New Jersey has residential growth (the other two suburban regions don’t), and the city has job growth, with increasing complexity as more job centers emerge outside Manhattan and as people travel between them and not just to Manhattan.

Don’t Romanticize Traditional Cities that Never Existed

(I’m aware that I’ve been posting more slowly than usual; you’ll be rewarded with train stations soon.)

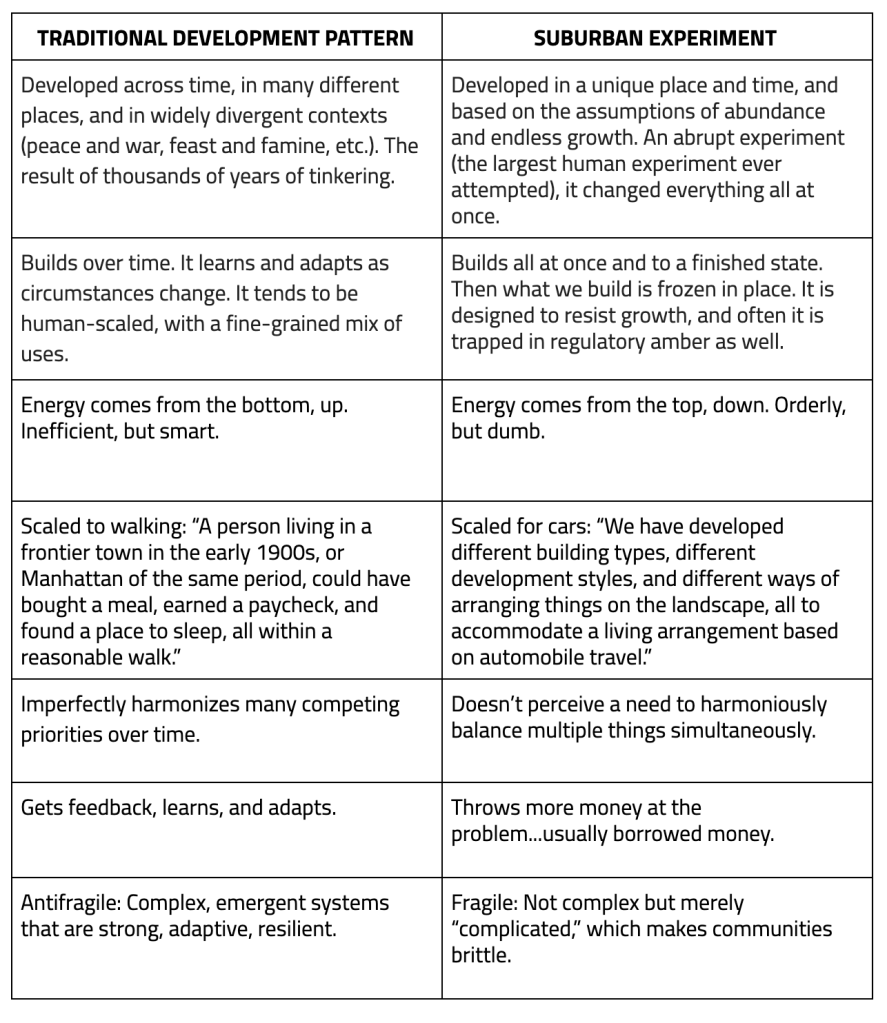

I saw a tweet by Strong Towns that compared traditional cities with the suburbs, and the wrongness of everything there reminded me of how much urbanists lie to themselves about what cities were like before cars. Strong Towns is more on the traditional urbanism side (to the point of rejecting urban rail on the grounds that it leads to non-gradual development), but a lot of what I’m critiquing here is, regrettably, commonly believed across the urbanist spectrum.

The basic problem with this comparison is that there was never such a thing as traditional urbanism. There are others; all of the claims in the comparison are false – for example, the line about “makes communities brittle” misses how little community empowerment cities had in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before zoning, and the line about top-down versus bottom-up energy misses how centralized coal and hydroelectric plants were at the turn of the century whereas left-voting NIMBY suburbs today are the most reliable place to find decentralized rooftop solar plants. But the fundamental problem is that Strong Town, and most urbanists, assume that there was a relatively fixed urban model around walkability, which cars came in and wrecked in the 20th century.

What’s true is that before mass motorization, people didn’t use cars to get around. But beyond that tautology, every principle of urban walkability was being violated in one pre-automobile urban typology or another.

Local commuting

Pre-automobile industrial cities were not 15-minute cities by any means. Marchetti’s constant of commuting goes back to at least the early 19th century; people in pre-automobile New York or London or Berlin commuted to a commercializing city center. This was to some extent understood in the second half of the 19th century: the purpose of rapid transit in New York, first steam els and then the subway, was to provide a fast enough commute so that the working class of the Lower East Side would get out of its tenements and into lower-density houses where they’d be turned from hyphenated Jews and Italians into proper Americans.

There has been a real change in that, in Gilded Age New York (and, I believe, in third-world cities today like Nairobi), people worked either locally or in city center. There was very little crosstown commuting, and so the Commissioners’ Plan for Manhattan in 1811 emphasized north-south commuting to Lower Manhattan, while private streetcar concessionaires likewise built routes to city center and rarely crosstown. Nor was there much long-distance travel except by the people who did work in city center: there were people who lived their entire lives in Brooklyn without visiting Manhattan, which became unthinkable by the early 20th century already. But this hardly makes Gilded Age Brooklyn a 15-minute city, any more than a modern suburb where most people do not visit city center out of fears of crime is anything but a suburb of the city, living off of the income generated by people who do commute in.

In truly premodern city, the situation depended on the time and place. Medieval European cities famously had little commuting – shopkeepers would live in the same building that housed their store, sleeping on an upper floor. But in Tang-era Chang’an, people did commute (my reference is the History of Imperial China series, no link, sorry). This is very far from the result of thousands of years of tinkering, when each time and place did something different before industrialization, and then went to yet another set of layouts after.

Local infrastructure

Pre-automobile industrial cities mixed top-down and bottom-up approaches, same as today. The grid plans favored in the United States, China, and the Roman Empire were more top-down than the unplanned street networks of most medieval and Early Modern European cities, each designed for a different cultural context. (In Imperial Rome much of the context was about following military manuals, for those cities that descend from forts.) In the medieval Muslim world, cities had cul-de-sacs long before cars, because this way each clan could have its own walled garden, so to speak.

Widely divergent contexts

Premodern cities developed in widely divergent contexts. Based on these contexts, they could look radically different. The comparison mentions war and peace; well, defensive walls were a fixture in many cities, and these mattered for their urban development. They were not nice strolls the way some embankments are today. There aren’t any good examples of walls in North America, but there are star forts, and they’re not usually pleasant walks – their purpose was to make the day of besieging troops as bad as possible, not to make tourists feel good about the city’s history. Medieval walls were completely different from star forts, and didn’t make for a walkable environment, either – in Paris I would routinely walk to the park and to the exterior of the Château de Vincennes, and while the park was pleasant, the castle has a moat and none of the street uses that activate a street, like retail or windows. The modern equivalents of such fixtures should be compared with prisons and modern military bases (some using the historic star forts), not touristy palaces.

Even the concept of city center is, as mentioned above on commuting, neither timeless (it didn’t exist in premodern Europe) nor a product of cars (it did exist in 19th-century America and Europe). Joel Garreau points out, either in Edge City or in some of the articles he’s written about the concept, that the traditional downtown was really only a fixture for a few generations, from the early 19th century to the middle of the 20th.

The issue of fragility

The entire comparison is grating, but smoehow the thing that bothers me most there is not the elementary errors, but the last point, about how traditional cities were antifragile for millennia before modern suburbia came in and wrecked them with debt.

This, to be very clear, is bullshit. Premodern cities could depopulate with one plague, famine, or war; these often co-occurred, such as when Louis XIV’s wars led to such food shortages that 10% of France’s population died in two famines spaced 15 years apart (put another way: France underwent a Reign of Terror’s worth of deaths every two weeks for a year and a half, and then a second for somewhat less than a year). In 1793, 10% of Philadelphia’s population died of yellow fever within the span of a few months. After repeated sacks and economic decline, Jaffa was abandoned in much of the Early Modern era.

Industrial cities generally do not undergo any of these things. (They can be subjected to genocide, like the Jews of Europe in the Holocaust, but that’s not at all about urbanism.) But that’s hardly a millennia-old tradition when it only goes back to about the middle of the 19th century, after the Great Hunger. In the UK, the Great Hunger affected rural areas like Ireland and Highland Scotland, but in a country that was at the time majority-rural – Britain would only flip to an urban majority in 1851 – it’s hardly a defense. Nor did the era after 1850 feature much stability in the cities; boom-and-bust cycles were common and the risk of unemployment and poverty was constant.

Urbanism for non-Tourists

There’s a common line among urbanists and advocates of car-free cities to the effect that all the nice places people go to for tourism are car-light, so why not have that at home? It’s usually phrased as “cities that people love” (for example, in Brent Toderian), but to that effect, mainly North American (or Australian) urbanists talk about how European cities are walkable, often in places where car use is rather high and it’s just the tourist ghetto that is walkable. Conversely, some of the most transit-oriented and dynamic cities in the developed world lack these features, or have them in rather unimportant places.

Normally, “Americans are wrong about Europe” is not that important in the grand scheme of things. The reason American cities with a handful of exceptions don’t have public transit isn’t that urbanist advocacy worries too much about pedestrianizing city center streets and too little about building subways to the rest of the city. Rather, the problem is the effect of tourism- and consumption-theoretic urbanism right here. It, of course, doesn’t come back from the United States – European urbanists don’t really follow American developments, which I’m reminded of every time a German activist on Mastodon or Reddit tries explaining metro construction costs to me. It’s an internal development, just one that is so parallel to how Americans analytically get Europe wrong that it’s worth discussing this in tandem.

The core of public transit

I wrote a blog post many years ago about what I called the in-between neighborhoods, and another after that. The two posts are rather Providence-centric – I lived there when I wrote the first post, in 2012 – but they describe something more general. The workhorses of public transit in healthy systems like New York’s or Berlin’s or Paris’s, or even barely-existing ones like Providence’s, are urban neighborhoods outside city center.

The definitions of both “urban” and “outside city center” are flexible, to be clear. In Providence, I was talking about the neighborhoods on what is now the R bus route, namely South Providence and the areas on North Main Street, plus some similar neighborhoods, including the East Side (the university neighborhood, the only one in Providence’s core that’s not poor) and Olneyville in the west. In larger, denser, more transit-oriented Berlin, those neighborhoods comprise the Wilhelmine Ring and thence stretch out well past the Ringbahn, sometimes even to city limits in those sectors where sufficient transit-oriented development has been built, and a single district like Neukölln may have more people than the entirety of Providence.

In Berlin, this can be seen in modal splits by borough; scroll down to the tables by borough, and go to page 45 of each PDF. The modal split does not at all peak in the center. Among the 12 boroughs, the one with the highest transit modal split for work trips is actually Marzahn-Hellersdorf, in deep East Berlin. The lowest car modal split is in the two centermost boroughs, Mitte and Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain, both with near-majorities for pedestrian and bike commutes – but the range of both of these modes is limited enough that it’s not supportable anywhere else in Berlin.

Nor is shrinking the city to the range of a bike going to help. Germany is full of cities of similar size to the combined total of Mitte and Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain; they have much higher car use, because what makes the center of Berlin work is the large concentration of jobs and other destinations brought about by the size of the city.

The same picture emerges in other transit cities. In Paris, the city itself is significant for the region’s public transit network, but its residents only comprise 30% of Francilien transit commuters, and even that figure should probably subtract out the outer areas of the city, which tourists don’t go to, like the entire northeast or the areas around and past the Boulevards of the Marshals. The city itself has much higher modal split than its suburbs, but that, again, depends on a thick network of jobs and other destinations that exist because of the dominance of the city as a commercial destination within a larger region.

Where tourists go

The in-between neighborhoods that drive the transit-oriented character of major cities are generally residential, or maybe mixed-use. Usually, they do not have tourist destinations. In Berlin, I advocate for tourists to visit Gropiusstadt and see its urbanism, but I get that people only do it if they’re especially interested in urban exploration. Instead, tourism clusters in city center; the museums are almost always in the center to the point that exceptions (like Balboa Park in San Diego) are notable, high-end hotels cluster in city center (the Los Angeles exception is again notable), and so on.

These tourism-oriented city centers often include pedestrianized street stretches. Berlin is rather atypical in Germany in not having such a stretch; in contrast, tourists can lose themselves in Marienplatz in Munich, or in various Altstadt areas of other cities, and forget that these cities have higher car use than Berlin, often much higher. For example, Leipzig’s car modal split for work trips is 47% (source, p. 13), higher than even Berlin’s highest-modal split borough, Spandau, which has 44% (Berlin overall is at 25%).

To be clear, Leipzig is, by most standards, fairly transit-oriented. Its tram network has healthy ridership, and its S-Bahn tunnel is a decent if imperfect compromise between the need to provide metro-like train service through the city and the need to provide long-distance regional rail to Halle and other independent cities in the region. But it should be more like Berlin and not the reverse.

Another feature of tourist cities is the premodern city core, with its charming very narrow streets. Berlin lacks such a core, and Paris only has a handful of such streets, mostly in the Latin Quarter. But Stockholm has an intact Early Modern core in Gamla Stan; it is for all intents and purposes a tourist ghetto, featuring retail catering to tourists and not much else. Stockholm is a very strong transit city with a monocentric core, but the core is not even at Gamla Stan, but to its north, north of T-Centralen, and thus the other tourist feature, the pedestrianized city center street with high-end retail, remains distinct from the premodern core.

Tellingly, these premodern cores exist even in thoroughly auto-oriented cities, ones with much weaker public transit than Leipzig. Italy supplies many examples of cities that were famously large in the Renaissance, and still have intact cores where one can visit the museums. A few years ago, Marco Chitti pointed out how Italian politicians, like foreign tourists, like taking photo-ops at farmers’ markets in small historic cities, while meanwhile, everyone in Italy does their shopping at suburban shopping centers offering far lower prices. To the tourist, Florence looks charming; to the resident, it is, in practice, a far more auto-oriented region than Stockholm or Berlin.