Bus Stop Consolidation and Blocks

There are arguments over bus stop spacing in my Discord channel. As the Queens bus redesign process is being finalized, there’s a last round of community input, and as one may expect, community board members amplify the complaints of people who reject any stop consolidation on “they’re taking my stop, I’ll have to walk longer” grounds. I wrote about this in 2018, as Eric and I were releasing our proposed Brooklyn bus redesign, which included fairly aggressive consolidation, to an average interstation of almost 500 meters, up from the current value of about 260. I’d like to revisit this issue in this post, first because of its renewed relevance, and second because there’s a complication that I did not incorporate into my formula before, coming from the fact that the city comprises discrete blocks rather than perfectly isotropic distribution of residents along an avenue.

The formula for bus stop spacing

The tradeoff is that stop consolidation means people have to walk longer to the bus stop but then the bus is faster. In practice, this means the bus is also more frequent by a proportionate amount – the resources required to operate a bus depend on time rather than distance, chiefly the driver’s wage, but also maintenance and fuel, since stops incur acceleration and idling cycles that stress the engines and consume more fuel.

The time penalty of each stop can be modeled as the total of the amount of time the bus needs to pull into the stop, the minimum amount of time it takes to open and close the doors, and the time it takes to pull out. Passenger boardings are not included, because those are assumed to be redistributed to other stops if a stop is deleted. In New York and Vancouver, the difference in schedules between local and limited stop buses in the 2010s was consistent with a penalty of about 25 seconds per stop.

The optimum stop spacing can be expressed with the following formula:

To explain in more detail:

- d is a dimensionless factor indicating how far one must walk, based on the stop spacing; the more isotropic passenger travel is, the lower d is, to a minimum of 2. The specific meaning of d is that if the stop spacing is n, then the average walk is n/d. For example, if there is perfect isotropy, then passengers’ distance from the nearest bus stop is uniformly distributed between 0 and n/2, so the average is n/4, and this needs to be repeated at the destination end, summing to n/2.

- Walk speed and walk penalty take into account that passengers prefer spending time on a moving bus to walking to the bus. In the literature that I’ve seen, the penalty is 2. Usually the literature assumes the walk speed is around 5 km/h, or 1.4 m/s; able-bodied adults without luggage walk faster, especially in New York, but the speed for disabled people is lower, around 1 m/s for the most common cases.

- Stop penalty, as mentioned above, can be taken to be 25 s.

- Average trip length is unlinked; for New York City Transit in 2019, counting NYCT local buses including SBS but not express buses, the average was 3,421 meters.

- Average bus spacing is the headway between buses on the route measured in units of distance, not speed; it’s expressed this way since the resources available can be expressed in how many buses can circulate at a given time, and then the frequency is the product of this figure with speed. In Brooklyn in the 2010s, this average was 1,830 m; our proposed network, pruning weaker routes, cut it to 1,180. The Queens figure as of 2017 appears similar to the Brooklyn figure, maybe 1,860 m. Summing the average trip length and average bus spacing indicates that passengers treat wait time as a worst-case scenario, or, equivalently, that they treat it as an average case but with a wait penalty of 2, which is consistent with estimates in the papers I’ve read.

In the most isotropic case, with d = 2, plugging in the numbers gives,

However, isotropy is more complex than this. For one, if we’re guaranteed that all passengers are connecting to one distinguished stop, say a subway connection point, then consolidating stops will still make them walk longer at the other end, but it will not make them walk any longer at the guaranteed end, since that stop is retained. In that case, we need to set d = 4 (because the average distance to a bus stop if the interstation is n is n/4 and at the other end we’re guaranteed there’s no walk), and the same formula gives,

The Queens bus redesign recognizes this to an extent by setting up what it calls rush routes, designed to get passengers from outlying areas in Eastern Queens to the subway connection points of Flushing and Jamaica; those are supposed to have longer interstations, but in practice this difference has shrunk in more recent revisions.

That said, even then, there’s a complication.

City blocks and isotropy

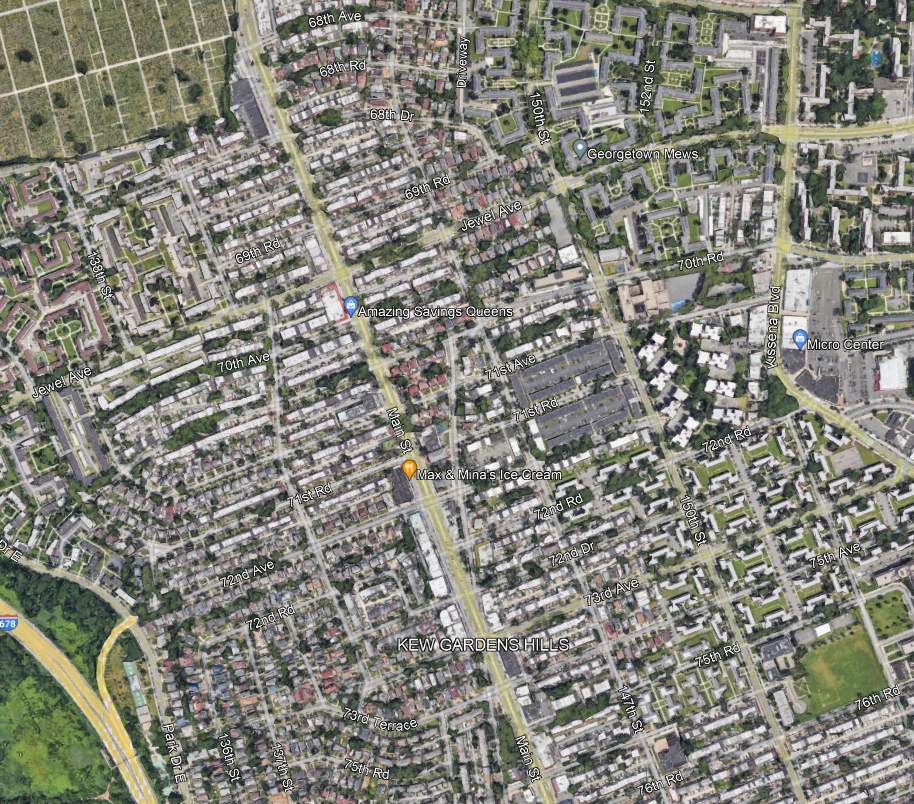

The models above assume that passengers’ origins are equally distributed along a line. For example, here is Main Street through Kew Gardens Hills, the stretch I am most likely to use a New York bus on:

I always take the bus to connect to Flushing or Jamaica, but within Kew Gardens Hills, the assumption of isotropy means that passengers are equally likely to be getting on the bus at any point along Main Street.

And this assumption does not really work in any city with blocks. In practice, neighborhood residents travel to Main Street via the side streets, which are called avenues, roads, or drives, and numbered awkwardly as seen in the picture above (72nd Avenue, then 72nd Road, then 72nd Drive, then 73rd Avenue, then 75th Avenue…). The density along each of those side streets is fairly consistent, so passengers are equally likely to be originating from any of these streets, for the most part. But they are always going to originate from a side street, and not from a point between them.

The local bus along Main, the Q20, stops every three blocks for the most part, with some interstations of only two blocks. Let’s analyze what happens if the system consolidates from a stop every three blocks, which is 240 meters, to a stop every six, which is 480. Here, we assume isotropy among the side streets, but not continuous isotropy – in other words, we assume passengers all come from a street but are equally likely to be coming from any street.

With that in mind, take a six-block stretch, starting and ending with a stop that isn’t deleted. Let’s call this stretch 0th Street through 6th Street, to avoid having to deal with the weird block numbering in Kew Gardens Hills; we need to investigate the impact of deleting a stop on 3rd Street. With that in mind: passengers originating on 0th and 1st keep going to 0th Street and suffer no additional walk, passengers originating on 5th keep going to 6th and also suffer no additional walk, passengers originating on 2nd and 4th have to walk two blocks instead of one, and passengers originating on 3rd have to walk three blocks instead of zero. The average extra walk is 5/6 of a block. This is actually more than one quarter of the increase in the stop spacing; if there is a distinguished destination at the other end (and there is), then instead of d = 4, we need to use d = 3/(5/6) = 3.6. This shrinks the optimum a bit, but still to 576 m, which is about seven blocks.

The trick here is that if the stop spacing is an even number of blocks, then we can assume continuous isotropy – passengers are equally likely to be in the best circumstance (living on a street with a stop) and in the worst (living on a street midway between stops). If it’s an odd number of blocks, we get a very small bonus from the fact that passengers are not going to live on a street midway between stops, because there isn’t one. The average walk distance, in blocks, with stops every 1, 2, 3, … blocks, is 0, 0.5, 2/3, 1, 1.2, 1.5, 12/7, 2, … Thus, ever so slightly, planners should perhaps favor a stop every five or seven blocks and not every six, in marginal cases. To be clear, the stop spacing on each stretch should be uniform, so if there are 12 blocks between two distinguished destinations, there should be one intermediate stop at the exact midpoint, but, perhaps, if there are 30 blocks with no real internal structure of more or less important streets, a stop should be placed every five and not six blocks, especially if destinations are not too concentrated.