Philadelphia and High-Speed Rail Bypasses (Hoisted from Social Media)

I’d like to discuss a bypass of Philadelphia, as a followup from my previous post, about high-speed rail and passenger traffic density. To be clear, this is not a bypass on Northeast Corridor trains: every train between New York and Washington must continue to stop in Philadelphia at 30th Street Station or, if an in my opinion unadvised Center City tunnel is built, within the tunnel in Center City. Rather, this is about trains between New York and points west of Philadelphia, including Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, and the entire Midwest. Whether the bypass makes sense depends on traffic, and so it’s an example of a good investment for later, but only after more of the network is built. This has analogs in Germany as well, with a number of important cities whose train stations are terminals (Frankfurt, Leipzig) or de facto terminals (Cologne, where nearly all traffic goes east, not west).

Philadelphia and Zoo Junction

Philadelphia historically has three mainlines on the Pennsylvania Railroad, going to north to New York, south to Washington, and west to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. The first two together form the southern half of the Northeast Corridor; the third is locally called the Main Line, as it was the PRR’s first line.

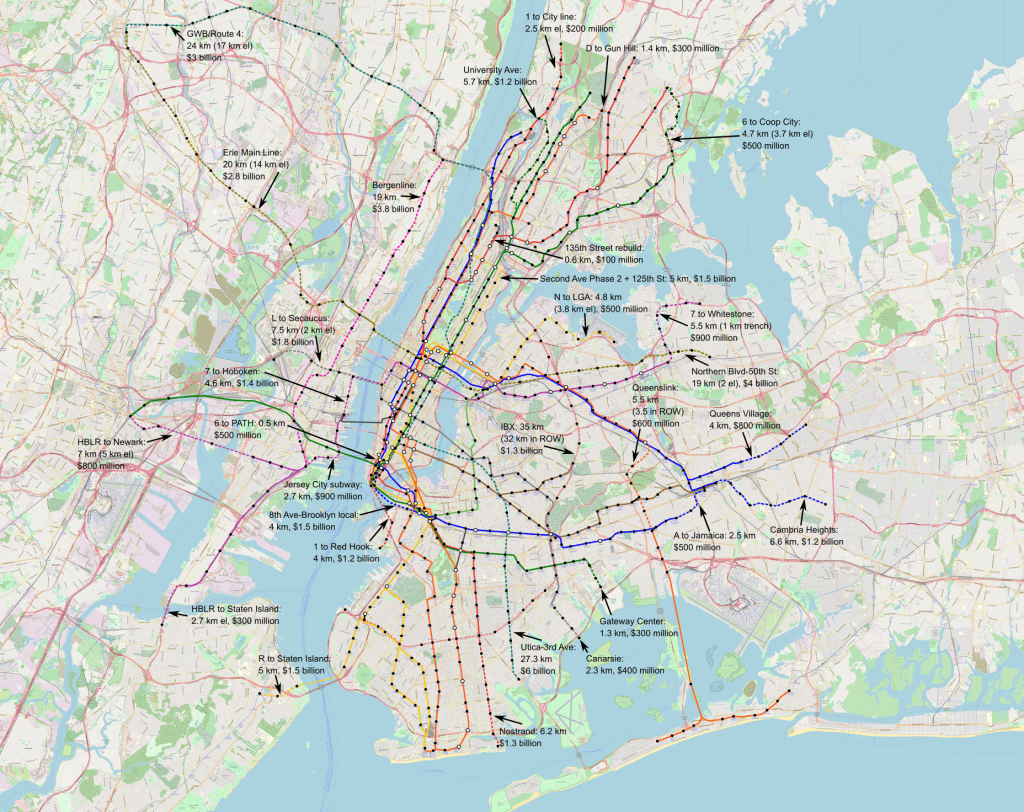

Trains can run through from New York to Washington or from Harrisburg to Washington. The triangle junction northwest of the station, Zoo Junction, permits trains from New York to run through to Harrisburg and points west, but they then have to skip Philadelphia. Historically, the fastest PRR trains did this, serving the city at North Philadelphia with a connection to the subway, but this was in the context of overnight trains of many classes. Today’s Keystone trains between New York and Harrisburg do no such thing: they go from New York to Philadelphia, reverse direction, and then go onward to Harrisburg. This is a good practice in the current situation – the Keystones run less than hourly, and skipping Philadelphia would split frequencies between New York and Philadelphia to the point of making the service much less useful.

When should trains skip Philadelphia?

The advantage of skipping Philadelphia are that trains from New York to Harrisburg (and points west) do not have to reverse direction and are therefore faster. On the margin, it’s also beneficial for passengers to face forward the entire trip (as is typical on American and Japanese intercity trains, but not European ones). The disadvantage is that it means trains from Harrisburg can serve New York or Philadelphia but not both, cutting frequency to each East Coast destination. The effect on reliability and capacity is unclear – at very high throughput, having more complex track sharing arrangements reduces reliability, but then having more express trains that do not make the same stop on the same line past New York and Newark does allow trains to be scheduled closer to each other.

The relative sizes of New York, Philadelphia, and Washington are such that traffic from Harrisburg is split fairly evenly between New York on the other hand and Philadelphia and Washington on the other hand. So this really means halving frequency to each of New York and Philadelphia; Washington gets more service with split service, since if trains keep reversing direction, there shouldn’t be direct Washington-Harrisburg trains and instead passengers should transfer at 30th Street.

The impact of frequency is really about the headway relative to the trip time. Half-hourly frequencies are unconscionable for urban rail and very convenient for long-distance intercity rail. The headway should be much less than the one-way trip time, ideally less than half the time: for reference, the average unlinked New York City Subway trip was 13 minutes in 2019, and those 10- and 12-minute off-peak frequencies were a chore – six-minute frequencies are better for this.

The current trip time is around 1:20 New York-Philadelphia and 1:50 Philadelphia-Harrisburg, and there are 14 roundtrips to Harrisburg a day, for slightly worse than hourly service. It takes 10 minutes to reverse direction at 30th Street, plus around five minutes of low-speed running in the station throat. Cutting frequency in half to a train every two hours would effectively add an hour to what is a less than a two-hour trip to Philadelphia, even net of the shorter trip time, making it less viable. It would eat into ridership to New York as well as the headway rose well above half the end-to-end trip, and much more than that for intermediate trips to points such as Trenton and Newark. Thus, the current practice of reversing direction is good and should continue, as is common at German terminals.

What about high-speed rail?

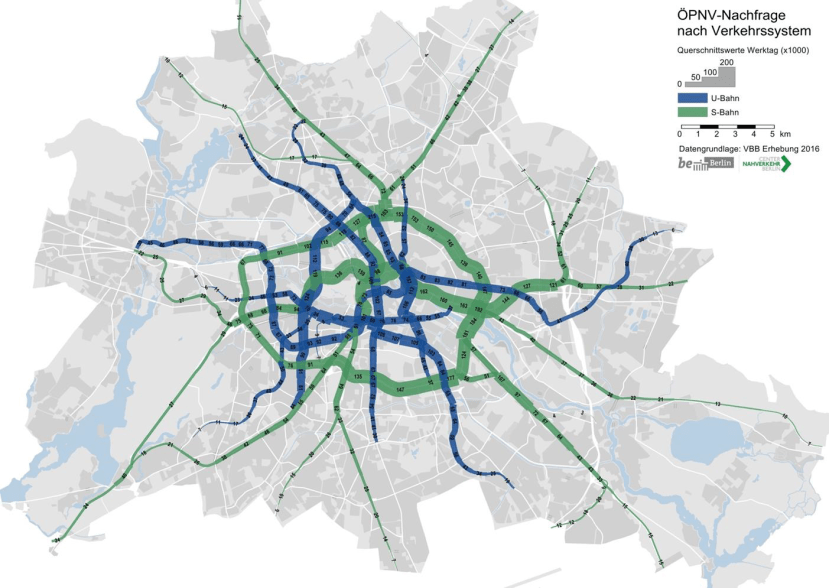

The presence of a high-speed rail network has two opposed effects on the question of Philadelphia. On the one hand, shorter end-to-end trip times make high frequencies even more important, making the case for skipping Philadelphia even weaker. In practice, high speeds also entail speeding up trains through station throats and improving operations to the point that trains can change directions much faster (in Germany it’s about four minutes), which weakens the case for skipping Philadelphia as well if the impact is reduced from 15 minutes to perhaps seven. On the other hand, heavier traffic means that the base frequency becomes much higher, so that cutting it in half is less onerous and the case for skipping Philadelphia strengthens. Already, a handful of express trains in Germany skip Leipzig on their way between Berlin and Munich, and as intercity traffic grows, it is expected that more trains will so split, with an hourly train skipping Leipzig and another serving it.

With high-speed rail, New York-Philadelphia trip times fall to about 45 minutes in the example route I drew for a post from 2020. I have not done such detailed work outside the Northeast Corridor, and am going to assume a uniform average speed of 240 km/h in the Northeast (which is common in France and Spain) and 270 km/h in the flatter Midwest (which is about the fastest in Europe and is common in China). This means trip times out of New York, including the reversal at 30th Street, are approximately as follows:

Philadelphia: 0:45

Harrisburg: 1:30

Pittsburgh: 2:40

Cleveland: 3:15

Toledo: 3:55

Detroit: 4:20

Chicago: 5:20

Out of both New York and Philadelphia, my gravity model predicts that the strongest connection among these cities is by Pittsburgh, then Cleveland, then Chicago, then Detroit, then Harrisburg. So it’s best to balance the frequency around the trip time to Pittsburgh or perhaps Cleveland. In this case, even hourly trains are not too bad, and half-hourly trains are practically show-up-and-go frequency. The model also predicts that if trains only run on the Northeast Corridor and as far as Pittsburgh then traffic fills about two hourly trains; in that case, without the weight of longer trips, the frequency impact of skipping Philadelphia and having one hourly train run to New York and Boston and another to Philadelphia and Washington is likely higher than the benefit of reducing trip times on New York-Harrisburg by about seven minutes.

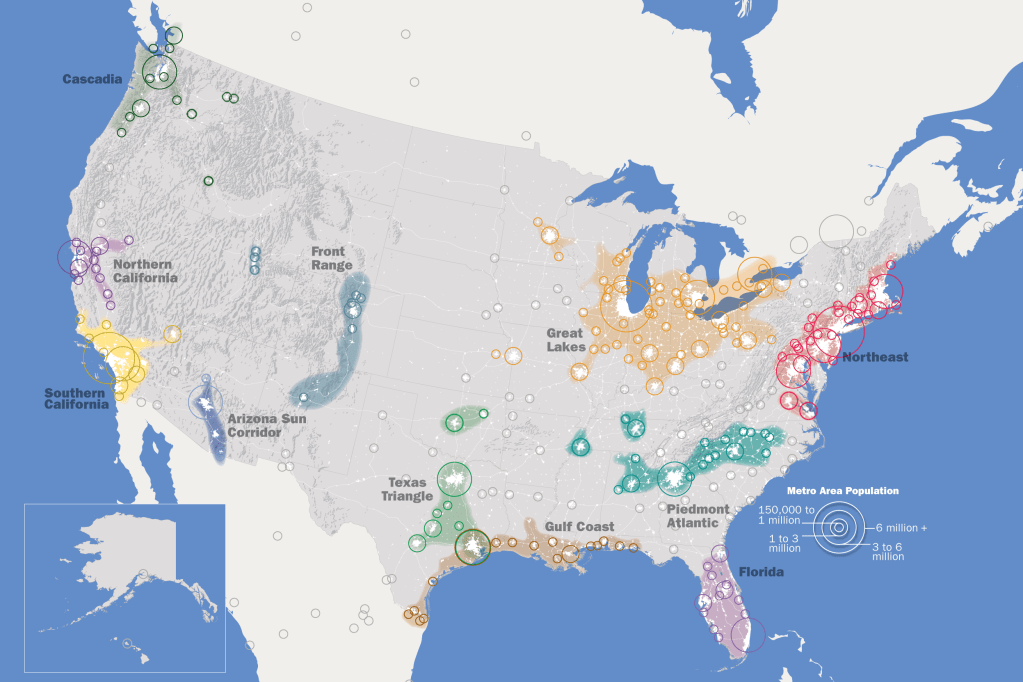

In contrast, the more of the network is built out, the higher the base frequency is. With the Northeast Corridor, the spine going beyond Pittsburgh to Detroit and Chicago, a line through Upstate New York (carrying Boston-Cleveland traffic), and perhaps a line through the South from Washington to the Piedmont and beyond, traffic rises to fill about six trains per hour per the model. Skipping Philadelphia on New York-Pittsburgh trains cuts frequency from every 10 minutes to every 20 minutes, which is largely imperceptible, and adds direct service from Pittsburgh and the Midwest to Washington.

Building a longer bypass

So far, we’ve discussed using Zoo Junction. But if there’s sufficient traffic that skipping Philadelphia shouldn’t be an onerous imposition, it’s possible to speed up New York-Harrisburg trains further. There’s a freight bypass from Trenton to Paoli, roughly following I-276; a bypass using partly that right-of-way and, where it curves, that of the freeway, would require about 70 km of high-speed rail construction, for maybe $2 billion. This would cut about 15 km from the trip via 30th Street or 10 km via the Zoo Junction bypass, but the tracks in the city are slow even with extensive work. I believe this should cut another seven or eight minutes from the trip time, for a total of 15 minutes relative to stopping in Philadelphia.

I’m not going to model the benefits of this bypass. The model can spit out an answer, which is around $120 million a year in additional revenue from faster trips relative to not skipping Philadelphia, without netting out the impact of frequency, or around $60 million relative to skipping via Zoo, for a 3% financial ROI; the ROI grows if one includes more lines in the network, but by very little (the Cleveland-Cincinnati corridor adds maybe 0.5% ROI). But this figure has a large error bar and I’m not comfortable using a gravity model for second-order decisions like this.