Category: Incompetence

The Problems of not Killing Penn Expansion and of Tariffs

Penn Station Expansion is a useless project. This is not news; the idea was suspicious from the start, and since then we’ve done layers of simulation, most recently of train-platform-mezzanine passenger flow. However, what is news is that the Trump administration is aiming to take over Penn Reconstruction (a separate, also bad project) from the MTA, in what looks like the usual agency turf battles, except now given a partisan spin. I doubt there’s going to be any money for Reconstruction (budgeted at $7 billion), let alone expansion (budgeted at $17 billion), and overall this looks like the usual promises that nobody intends to act upon. The problem is that this project is still lurking in the background, waiting for someone insane enough to say what not a lot of people think but few are willing to openly disagree with and find some new source of money to redirect there. And oddly, this makes me think of tariffs.

The commonality is that free trade is not just good, but is more or less an unmixed blessing. In public transport rolling stock procurement, the costs of tariffs are so high that a single job created in the 2010s cost $1 million over 4-6 years, paying $20/hour. In infrastructure, in theory most costs are local and so it shouldn’t matter, but in practice some materials need to be imported, and when they run into trade barriers, they mess entire construction schedules. Boston’s ability to upgrade commuter rail stations with high platform was completely lost due to successive tightening of the Buy America waiver process under Trump and then Biden, to the point that even materials that were just not made in America (steel, FRP) could not be imported. The problem is that nobody was willing to say this out loud, and instead politicians chose to interfere with bids to get some photo-ops, getting trains that are overpriced and fail to meet schedule and quality standards.

Thus, the American turn away from free trade, starting with Trump’s 2016 campaign. During the Obama-Trump transition, the FTA stopped processing Buy America waivers, as a kind of preemptive obedience to something that was never written into the law, which includes several grounds for waivers. During the Trump-Biden transition, the standards were tightened, and waivers required the approval of a political office at the White House, which practiced a hostile environment, hence the above example of the MBTA’s platform problems. Now there are general tariffs, at a rate that changes frequently with little justification. The entire saga, especially in the transit industry, is a textbook example not just of comparative advantage, but of the point John Williamson made in the original Washington Consensus that trade barriers were a net negative to the country that imposes them even if there’s no retaliation, purely from the negative effects on transparency and government cleanliness. This occurred even though tariffs were not favored in the political elite of the United States, or even in the general public; but nobody would speak out except special interests and populists who favored trade barriers.

And Penn Expansion looks the same. It’s an Amtrak turf game, which NJ Transit and the MTA are indifferent to. NJ Transit’s investment plan is not bad and focuses on actual track-level improvements on the surface. The MTA has a lot of problems, including the desire for Penn Reconstruction, but Penn Expansion is not among them. The sentiments I’m getting when I talk to people in that milieu is that nobody really thinks it’s going to happen, and as a result most people don’t think it’s important to shoot down what is still a priority for Amtrak managers who don’t know any better.

The problem is that when the explicit argument isn’t made, the political system gets the message that Penn Expansion is not necessarily bad, but now is not the time for it. It will not invest in alternatives. (On tariffs, the alternative is to repeal Buy America.) It will not cancel the ongoing design work, but merely prolong it by demanding more studies, more possibilities for adding new tracks (seven? 12? Any number in between?). It will insist that any bounty of money it gets go toward more incremental work on this project, and not on actually useful alternatives for what to do with $17 billion.

This can go on for a while until some colossally incompetent populist of the type that can get elected mayor or governor in New York, or perhaps president, decides to make it a priority. Then it can happen, and $17 billion plus future escalation would be completely wasted, and further investment in the system would suffer because everyone would plainly see that $17 billion buys next to nothing in New York so what’s the point in spending a mere $300 million here and there on a surface junction? If it were important then Amtrak would have prioritized that, no? Even people who get on some level that the agencies are bad with money will believe them on technical matters like scheduling and cost estimation over outsiders, in the same manner that LIRR riders think the LIRR is incompetent and also has nothing to learn from outsiders.

The way forward is to be more formal about throwing away bad ideas. Does Penn Expansion have any transportation value? No. So cancel it. Drop it from the list of Northeast Corridor projects, cancel all further design work, and spend about 5 orders of magnitude less money on timetabling trains at Penn Station within its existing footprint. Don’t let it lurk in the background until someone stupid enough decides to fund it; New York is rather good lately at finding stupid people and elevating them to positions of power. And learn to make affirmative arguments for this rather than the usual “it will just never happen” handwringing.

Open BRT

BRT, or bus rapid transit, can be done in one of two ways: closed and open. Closed systems imitate rail lines, in that there is a BRT route along the entire length of the corridor; open ones instead take a trunk route, upgrade it with dedicated lanes and other BRT features, and let routes run through from it to branches that are not so equipped, perhaps because there is less traffic on the branches. I complained 14 years ago that New York City Transit was planning closed BRT in the form of SBS on Hylan Boulevard on Staten Island, a good route for open BRT. Well, now the MTA is planning BRT on the disused North Shore Branch of the Staten Island Railway, arguing that it is better than reactivating rail service because buses could use it as an open corridor – except that this is a poor corridor for open BRT. This leads to the question: which corridors are good for open BRT to begin with?

Trunks and branches are good

Open BRT can be analogized to a Stadtbahn system, fast in the core and slow outside it. Like a Stadtbahn, it works best where several branches can converge onto a single route, where the high traffic both requires higher capacity and justifies higher investment; just as grade separation increases the throughput of a rail line, BRT treatments increase those of a bus through greater separation from other traffic and regularity of service.

Unlike a Stadtbahn, open BRT remains a bus. This means two things:

- The trunk route must itself be a strong surface route. It had better be a wide street with room for physically separated bus lanes, or else a city center route that could be turned into a transit mall. A Stadtbahn system puts the fast central portion underground and could do it independently of the street network, or even run under a slow narrow street like Tremont Street in Boston.

- The connections from the trunk route to the branches must themselves be strong bus links. If the bus needs to zigzag on narrow residential streets to get between two wider arterials, then it will be unreliable and slow even if one of the wider arterials gets dedicated lanes. A Stadtbahn system can tunnel a few hundred meters here and there to ensure the onramps are adequate, but a surface bus system cannot, not without driving its cost structure to that of a subway but with few of the benefits of underground running.

The North Shore Branch could pass a modified version of criterion 1, but fails criterion 2. In general, former rail lines are bad for such BRT systems, since the street network was never set up for such connections. In contrast, street networks with a central artery and streets of intermediate importance between it and residential side streets emanating from it, which were never used for grade-separated rail lines, are more ideal for this treatment.

Grids are bad

Street grids eliminate the branch hierarchy of traditional street networks. There is still a hierarchy of more and less important grid streets – in Manhattan, the avenues and two-way streets are wider and more used for traffic than the one-way streets – but there is little branching. Bus networks can still branch if they move between streets, which happens in Manhattan, but it’s not usually a good idea: Barcelona’s Nova Xarxa uses the grid to run mostly independent bus routes, each route mostly sticking to a grid arterial, and the extent of branching on the Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx bus networks is limited to a handful of short segments like the Washington Bridge.

In situations like this, open BRT would not work. Hylan is possibly the only route in New York that has any business running open BRT. For this reason, our Brooklyn bus redesign proposal, and any work we could do for Queens, Manhattan, or the Bronx, eschews the open BRT concept. The buses are upgraded systemwide, since features like off-board fare collection and wider stop spacing are not really special BRT features but are rather normal in, for example, the urban German-speaking world. Center bus lanes are provided wherever there is need and room. There is more identification of a bus route with the street it runs on, but it isn’t really closed BRT, which is a series of treatments giving the BRT routes dedicated fleets and stations, for example with left-side doors to board from metro-style island platforms like Transmilenio.

What this means more broadly is that the open BRT is not a good fit for most of North America, with its grid routes. Occasionally, a diagonal street could act as a trunk if available, but this is uncommon. Broadway is famous for running diagonally to the Manhattan grid, but that’s not a BRT route but a subway route.

Amtrak’s Failure

An article in Streetsblog by Jim Mathews of the Rail Passengers Association talking up Amtrak as a success has left a sour taste in my mouth as well as those of other good transit activists. The post says that Amtrak is losing money and it’s fine because it’s a successful service by other measures. I’ve talked before about why good intercity rail is profitable – high-speed trains are, for one, and has a cost structure that makes it hard to lose money. But even setting that aside, there are no measures by which Amtrak is a successful, if one is willing to look away from the United States for a few moments. What the post praises, Amtrak’s infrastructure construction, is especially bad by any global standard. It is unfortunate that American activists for mainline rail are especially unlikely to be interested in how things work in other parts of the world, and instead are likely to prefer looking back to American history. I want to like the RPA (distinct from the New York-area Regional Plan Association, which this post will not address), but its Americanism is on full display here and this blinds its members to the failures of Amtrak.

Amtrak ridership

The ridership on intercity rail in the United States is, by most first-world standards, pitiful. Amtrak reports, for financial 2023, 5.823 billion passenger-miles, or 9.371 billion p-km; Statista gives it at 9.746 billion p-km for 2023, which I presume is for calendar 2023, capturing more corona recovery. France had 65 billion p-km on TGVs and international trains in 2023.

More broadly than the TGV, Eurostat reports rail p-km without distinction between intercity and regional trains; the total for both modes in the US was 20.714 billion in 2023 and 30.89 billion in 2019, commuter rail having taken a permanent hit due to the decline of its core market of 9-to-5 suburb-to-city middle-class commuting. These figures are, per capita, 62 and 94 p-km/year. In the EU and environs, only one country is this low, Greece, which barely runs any intercity rail service and even suspended it for several months in 2023 after a fatal accident. The EU-wide average is 955 p-km/year. Dense countries like Germany do much better than the US, as do low-density countries like Sweden and Finland. Switzerland has about the same mainline rail p-km as the US as of 2023, 20.754 billion, on a population of 8.9 million (US: 335 million).

So purely on the question of whether people use Amtrak, the answer is, by European standards, a resounding no. And by Japanese standards, Europe isn’t doing that great – Japan is somewhat ahead of Switzerland per capita. Amtrak trains are slow: the Northeast Corridor is slower than the express trains that the TGV replaced, and the other lines are considerably slower, running at speeds that Europeans associate with unmodernized Eastern European lines. They are infrequent: service is measured in trains per day, usually just one, and even the Northeast Corridor has rather bad frequencies for the intensely used line it wants to be.

Is this because of public support?

No. American railroaders are convinced that all of this is about insufficient public funding, and public preference for highways. Mathews’ post repeats this line, about how Amtrak’s 120 km/h average speeds on a good day on its fastest corridor should be considered great given how much money has been spent on highways in America.

The issue is that other countries spend money on highways too. High American construction costs affect highway megaprojects as well, and thus the United States brings up the rear in road tunneling. The highway competition for Amtrak comprises fairly fast, almost entirely toll-free roads, but this is equally true of Deutsche Bahn; the competition for SNCF and Trenitalia is tollways, but then those tollways are less congested, and drivers in Italy routinely go 160 km/h on the higher-quality stretches of road.

Amtrak itself has convinced itself that everyone else takes subsidies. For example, here it says “No country in the world operates a passenger rail system without some form of public support for capital costs and/or operating expenses,” mirroring a fraudulent OIG report that compares the Northeast Corridor (alone) to European intercity rail networks. Technically it’s true that passenger rail in Europe receives public subsidies; but what receives subsidies is regional lines, which in the US would never be part of the Amtrak system, and some peripheral intercity lines run as passenger service obligation (PSO) with in theory competitive tendering, on lines that Amtrak wouldn’t touch. Core lines, equivalent to Chicago-Detroit, New York-Buffalo, Washington-Charlotte-Atlanta, Los Angeles-San Diego, etc., would be high-speed and profitable.

But what about construction?

What offends me the most about the post is that it talks up Amtrak’s role as a construction company. It says,

Today, our nationalized rail operator is also a construction company responsible for managing tens of billions of dollars for building bridges, tunnels, stations, and more – with all the overhead in project-management staff and capital delivery that this entails.

The problem is that Amtrak is managing those tens of billions of dollars extremely inefficiently. Tens of billions of dollars is the order of magnitude that it took to build the entire LGV network to day ($65.5 billion in 2023 prices), or the entire NBS network in Germany ($68.6 billion). Amtrak and the commuter rail operators think that if they are given the combined cost to date of both networks, they can upgrade the Northeast Corridor to be about as fast as a mixed high- and low-speed German line, or about the fastest legacy-line British trains (720 km in 5 hours).

The rail operations are where Amtrak is doing something that approximates good rail work – lots of extraneous spending, driving up Northeast Corridor operating costs to around twice the fares on German and French high-speed trains, probably around 3-4 times the operating costs on those trains. But capital construction is a bundle of bad standards for everything, order-of-magnitude cost premiums, poor prioritization, and agency imperialism leading Amtrak to want to spend $16 billion on a completely unnecessary expansion of Penn Station. The long-term desideratum of auto-tensioned (“constant-tension”) catenary south of New York, improving reliability and lifting the current 135 mph (217 km/h) speed limit, would be a routine project here, reusing the poles with their 75-80 meter spacing; an incompetent (since removed) Amtrak engineer insisted on tightening to 180′ (54 m) so the project is becoming impossibly expensive as the poles have to be replaced during service. “Amtrak is also doing construction” is a derogatory statement about Amtrak.

Why are they like this?

Americans generally resent having to learn about the rest of the world. This disproportionately affects industries where the United States is clearly ahead (for example, software), but also ones where internal American features incline Americans to overfocus on their own internal history. Railroad history is rich everywhere, and the relative decline of the railway in favor of the highway lends itself to wistful alternative history, with intense focus on specific lines or regions. New Yorkers are, in the same vein, atypically provincial when it comes to the subway’s history, and end up making arguments, such as about the difficulty of accessibility retrofits on an old system, that can be refuted by looking at peer American systems, not just foreign ones.

The upshot is that an industry and an advocacy ecosystem that both intensely believe that railroad decline was because government investment favored roads – something that’s only partly true, since the same favoring of roads happened more or less everywhere – will want to learn from their own local histories. Quite a lot of advocacy by the RPA falls into the realm of trying to revive the intercity rail system the US had in the 1960s, before the bankruptcies and near-bankruptcies that led to the creation of Amtrak – but this system was what lost out to highways and cars to begin with. The innovations that allowed East Asia to avoid the same fate, and the innovations that allowed Western Europe to partly reverse this fate, involve different ideas of how to build and operate intercity rail.

And all of this requires understanding that, on a basic level, Amtrak is best described as a mishmash of the worst features of every European and East Asian railway: speed, fares, frequency, reliability, coverage. Each country that I know of misses on at least one of these aspects – Swiss trains are slow, the Shinkansen is expensive, the TGV has multi-hour midday gaps, German trains barely run on a schedule, China puts its train stations at inconvenient locations. Amtrak misses on all of those, at once.

And while Amtrak misses on service quality in operations, it, alongside the rest of the American rail construction industry, practically defines bad capital planning. Cities can build the right project wrong, or build the wrong project right, or have poor judgment about standards but not project delivery or the reverse, and somehow, Amtrak’s current planning does all of these wrong all at once.

Consultant Slop and Europe’s Decision not to Build High-Speed Rail

I’m sitting on a series of three trains to Rome, totaling 14 hours of travel. If a high-speed rail network is built connecting those cities, the trip can be reduced to about 7.5 hours: 2.5 Berlin-Munich (currently 4), 2 Munich-Verona (currently 5.5), around 2.75 Verona-Rome (currently 3.5), around 0.25 changing time (currently 1). The slowest section is being bypassed with the under-construction Brenner Base Tunnel, but not all of the approaches to the tunnel are, and Germany is happy with its trains averaging slightly slower speeds than the 1960s express Shinkansen.

I bring this up because it’s useful background for a rather stupid report by Transport and Environment that was making the rounds on European social media, purporting to rank the different intercity rail operators of Europe, according to criteria that make it clear nobody involved in the process cares much about infrastructure construction or about what has made high-speed rail work at the member state level. It’s consultant slop, based on a McKinsey report that conflicts with the published literature on intercity rail ridership elasticity, which makes it clear that speed matters greatly. Astonishingly, even negative discourse about the study, by people who I respect, talks about the slop and about the problems of privatization, but not about the need to actually go ahead and build those high-speed connections, without which there are sharp limits to the quality of life available to the zero-carbon lifestyle, limits that make people avoid that lifestyle and instead fly and drive. In effect, Europe and its institutions have made a collective decision over the last 10 or so years not to build high-speed rail, to the point that activism suggesting it reverse course and do so is treated as self-evidently laughable.

The T&E study

The T&E study purports to rank the intercity rail operators of Europe. There are 27 operators so ranked, which do not exactly correspond to the 27 member states, but instead omit some peripheral states, include British and Swiss options, and have some private operators, including inexplicably treating OuiGo as separate from the rest of the TGV. The ranking is of operators rather than infrastructure systems; there is no attention given to planning infrastructure and operations together. Trenitalia comes first, followed by a near-tie between RegioJet and SBB; Eurostar is last. Jon Worth had to pour cold water on the conclusions and the stenography in various European newspapers about them.

In fact, the study fits so perfectly into my post about making up rankings that it is easy to think I wrote the post about T&E – but no, the post is from 2.5 years ago. The issue is that it came up with such bad weighting in judging railways that one is left to wonder if it specifically picked something that would sound truthy and put SBB at or near the top just to avoid raising too many questions. The criteria used are as follows:

- Ticket prices: 25%

- Special fares and reductions: 15%

- Reliability: 15%

- Booking experience: 15%

- Compensation policies: 10%

- Traveler experience (speed and comfort): 10%

- Night trains and bicycle policy: 5%

None of this is even remotely defensible, and none of this passes any sanity check. No, it is not 1.5 times as important to have special reductions in fares for advance bookings or other forms of price discrimination as to have a combination of speed and comfort. The Shinkansen has fixed fares and is doing fine, thank you very much; SNCF’s own explanations of its airline-style yield management system portray it as a positive but not essential feature – its reports from 2009 recommending high-speed rail development in the United States cite yield management as a 4% increase in revenue, which is good but not amazing.

But more broadly, it is daft to set a full 50% of the weight on fares and fare-related issues (i.e. compensation), and 15% on the booking experience, and relegate speed to part of an issue that is only 10%. That’s not how high-speed rail ridership works. Cascetta-Coppola find a ridership elasticity with respect to trip time of about -2, but only -0.37 with respect to fares. Börjesson finds a much narrower spread, -1.12 and -0.67 respectively, but still the same directionally. Speed matters.

And yet, T&E doesn’t seem to care. The best hints for the reason why are in the way it compares operators rather than national networks, and relies on a McKinsey report pitched at private entrants and not at member state policymakers, who do not normally outsource decisionmaking to international consultants. It doesn’t think in terms of systems or networks, because it isn’t trying to make a pitch at how a member state can improve its rail network, but rather at how a private competitor should aim to make a profit on infrastructure built previously by the state.

The need for state planning

Every intercity rail network worth its name was built and planned publicly, by a state empowered to do so. In East Asia, this comprises the high-speed rail networks of China, Japan, Korean, and Taiwan, all funded publicly, even if Japan subsequently privatized Shinkansen operation (though not construction) to regional monopolies that, while investor-owned, are too prestigious to fail. In Europe, some networks have high-speed rail at their core, like France, and others don’t, like Switzerland or the Netherlands, but the latter instead optimize state planning at lower speed, with tightly timed connections, strategic investments to speed up bottlenecks, and integration between rolling stock, the timetable, and infrastructure.

This feature of the main low-speed European rail network frustrates some attempts at disaggregating the effects of different inputs on ridership and revenue. At the level of a sanity check, there does not appear to be a noticeable malus to French rail ridership from its low frequency at outlying stations. But then France relies on one-seat rides from Paris to rather small cities, which do not have convenient airport access, and in its own way integrates this operating paradigm with rolling stock (bilevels optimized for seating capacity, not fast egress or acceleration) and infrastructure (bypasses around intermediate cities, even Lyon). Switzerland, in contrast, has these timed connections such that the effective frequency even on three-seat rides is hourly, with guaranteed short waits at the transfers, and this provides an alternative way to connect small cities with not just large ones but also each other.

But in both cases, the operating paradigm is connected with the infrastructure, and this was decided publicly by the state, based on governmental financial constraints, imposed in the 1970s in France (leading to extraordinarily low construction costs for the LGV Sud-Est) and the 1980s in Switzerland (leading to the hyper-optimized operations of Bahn 2000 in lieu of a high-speed rail system). A private operator can come in, imitate the same paradigm that the infrastructure was built for, and sometimes achieve lower operating costs by being more aggressive about eliminating redundant positions that a state operator may feel too constrained by unions to. But it cannot innovate in how to run trains. Even in Italy and Spain, where private competition has led to lower fares and higher ridership, all the private competitors have done is force service to look more like the TGV as it is and less like the TGV as SNCF management would like it to be internationally. Even there, they do not innovate, but merely imitate what the TGV already had purely publicly, on infrastructure that was designed for TGV or ICE service intensity all along.

The idea that the private sector can innovate in intercity rail comes from the same imitation of airline thinking that led to the failure of Eurostar, with its high fares and airline-style boarding and queuing. In the airline business, integration between infrastructure and operations is weak, and private airlines can innovate in aircraft utilization, fast boarding, no-frills service, and other aspects that led low-cost carriers to success. Business analysts drawn from that world keep trying to make this work for trains, and fail; the Spinetta Report mentions that OuiGo tanked TGV revenues, and ridership did not materially increase when it was introduced due to inconveniences imposed by the system of segmenting the market by fare.

Europe’s decision not to build high-speed rail

In the 2000s, there was semi-official crayon, such as the TEN-T system, for EU-wide high-speed rail, inspired by the success of the TGV. Little of it happened, and by the 2010s, it became more common to encounter criticism alleging that it could not be done, and it was more important to focus on other things – namely, private competition, the thing that cannot innovate in rail but could in airlines.

At no point was there a formal decision not to build high-speed rail at a European scale. Projects just fell aside, unless they were megaproject tunnels across mountains like the Brenner Base Tunnel or water like the Fehmarn Belt Tunnel, and then there is underinvestment in the approaches, so that the average speed remains shrug-worthy. The discourse shifted from building infrastructure to justifying not building it and pitching on-rail competition instead. This, I believe, is due to factors going back to the 1990s:

- The failure of Eurostar to produce high ridership. It underperformed expectations; it also underperforms domestic city pairs. SNCF is happy to collect monopoly profits from international travelers, and, in turn, potential travelers associate high-speed rail with high fares and inconvenience and look elsewhere. One failed prominent project can and does poison the technology, potentially indefinitely.

- The anti-state zeitgeist at the EU level. This can be described as neoliberalism, but the thoroughly neoliberal Blair/Brown and Cameron cabinets happily planned High Speed 2. The EU goes beyond that: it is too scared to act as a state on matters other than trade, and that leads people in EU policy to think in terms of government-by-nudge, rather like the Americans.

- SNCF and DB’s profiteering off of cross-border travelers in different ways turns them into Public Enemies #1 and #2 for people who travel between different member states by rail, who are then reluctant to see them as successes domestically.

For all of these reasons, it’s preferred at the level of EU policymaking and advocacy not to build infrastructure. Infrastructure requires there to be a public sector, and the EU only does that on matters of trade and regulatory harmonization.

Jon Worth has done a lot of work on getting a passenger rights clause into the agenda for the new EU Parliament, to deal with friction between DB and SNCF when each blames the other when a cross-border passenger is stranded (roughly: DB blames SNCF for running low frequencies so that if DB’s last train is delayed the passenger is stranded, SNCF blames DB for being so delayed in the first place). This is a good kind of regulatory harmonization. It reminds me of the EU’s role in health care: there’s reciprocity among the universal health care systems of Europe, for example allowing EU immigrants but not non-European ones to switch to the Kasse upon arrival; but at the same time, the EU has practically no role in designing or providing these universal health care system or even, as the divergent responses to corona showed in 2020, in coordinating non-pharmaceutical interventions for public health in a pandemic.

But health care does not require large coordinating bodies, and infrastructure does. Refugee camps tended to by UN agencies that have to pay bribes and protection fees to local gangs can have surprisingly good health care outcomes. Cox’s Bazar’s Rohingya camps have infant mortality rates comparable to those of Bangladesh and Burma; Gaza had good if worse-than-Israeli life expectancy and infant mortality until the war started. But nobody can build infrastructure this way. Top-down state action is needed to coordinate, which means actual infrastructure construction, not just passenger rights.

The thinking at the EU level is that greater on-rail competition can improve service quality. But that’s just a form of denial. The EU has no willingness to actually build the high-speed rail segments required to enable rail trips across borders, and so various anti-state actors, most on the center-to-center-right but not all, lie to themselves that it’s okay, that if the EU fails to act as a state then the private sector can step in if allowed to. That’s where the T&E study comes in: it rates operators on how to act like a competitive flight level-zero airline, going with this theory of private-sector innovation to cope with the fact that cross-border rail isn’t being built and try to salvage something out of it.

But it can’t be salvaged, not in this field; the best the private sector can do is provide equivalent service to a good state service on infrastructure that the state built. The alternative to the state is not greater private initiative. In infrastructure, the political alternative is that people who are not Green voters, which group comprises 92.6% of the European Parliament, are going to just drive and fly and associate low-carbon transportation with being contained to within biking distance of city center. The economic alternative is that ties between European cities will remain weak, to the detriment of the European economy and its ability to scale up.

Quick Note: Kathy Hochul and Eric Adams Want New York to Be Worse at Building Infrastructure

Progressive design-build just passed. This project delivery system brings New York in full into the globalized system of procurement, which has led to extreme cost increases in the United Kingdom, Canada, and other English-speaking countries, making them unable to build any urban transit megaprojects. Previously, New York had most of the misfeatures of this system, largely through convergent evolution, but due to slowness in adapting outside ideas, the state took until now, with extensive push from Adams’ orbit, for which Adams is now taking credit, to align. Any progress in cost control through controlling project scope will now be wasted on the procurement problems caused by this delivery method.

What is progressive design-build?

Progressive design-build is a variant on design-build. There is some divergence between New York terminology and rest-of-world terminology; for people who know the latter, progressive design-build is approximately what the rest of the world calls design-build.

To give more detail, designing and constructing a piece of infrastructure, say a single subway station, are two different tasks. In the traditional system of procurement, the public client contracts the design with one firm, and then bids it out to a different firm for construction; this is called design-bid-build. All low-construction cost subway systems that we are aware of use a variant of design-bid-build, but two key features are required to make it work: sufficient in-house supervision capacity since the agency needs to oversee both the design and the build contracts, and flexibility to permit the build contractors to make small changes to the design based on spot prices of materials and labor or meter-scale geological discoveries. The exact details of both in-house capacity and flexibility differ by country; for example, Turkey codifies the latter by having the design contract only cover 60% design, and bundling going from 60% to 100% design with the build contract. Despite the success of the system in low-construction cost environments, it is unpopular among the global, especially English-speaking, firms, because it is essentially client-centric, relying on high competence levels in the public sector to work.

To deal with the facts that large global firms think they are better than the public sector, and that the English-speaking world prefers its public sector to be drowned in a bathtub, there are alternative, contractor-centric systems of project delivery. The standard one in the globalized system is called design-build or design-and-build, and simply means that the same contractor does both. This means less public-facing friction between designers and builders, and more friction that’s hidden from public view. Less in-house capacity is required, and the contracts grow larger, an independent feature of the globalized system. As the Swedish case explains in the section on the traditional and globalized systems, globalized Swedish contracts go up to $300-500 million per contract (and Swedish costs, once extremely low, are these days only medium-low); in New York, contracts for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 are already in the $1-2 billion range.

In New York, the system is somewhat complicated by the text of legacy rules on competitive bidding, which outright forbid a company from portraying itself as doing both design and construction. It took recent changes to legalize the Turkish system of bundling the two contracts differently; this changed system is what is called design-build in New York and is used for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2, even though there are still separate design and construction contracts, and is even called design-build in Turkey.

Unfortunately, New York did not stop at this, let’s call it, des-bid-ign-build system. Adams and Hochul want to be sure to wreck state capacity. Thus, they’ve pushed for progressive design-build, which is close to what the rest of the world calls design-build. More precisely, the design contractor makes a build bid at the end of the design phase, and is presumed to become the build contractor, but if the price is too high, there’s an escape clause and then it becomes essentially design-bid-build.

The globalized system that led to a cost explosion in the UK and Canada in the 1990s and 2000s from reasonable to strong candidates for second worst in the world (after the US) is now coming to New York, which already has a head start in high construction costs due to other problems. It’s a win-win for political appointees and cronies, and they clearly matter more than the people of the city and state of New York.

TGV Imitators: Learning the Wrong Lessons From the Right Places

I talked last time about how high-speed rail in Texas is stuck in part because of how it learned the wrong lessons from the Shinkansen. That post talks about several different problems briefly, and here I’d like to develop one specific issue I see recur in a bunch of different cases, not all in transportation: learning what managers in a successful case say is how things should run, rather than how the successful case is actually run. In transportation, the most glaring case of learning the wrong lessons is not about the Shinkansen but about the TGV, whose success relies on elements that SNCF management was never comfortable with and that are the exact opposite of what has been exported elsewhere, leading countries that learned too much from France, like Spain, to have inferior outcomes. This also generalizes to other issues, such as economic development, leading to isomorphic mimicry.

The issue is that the TGV is, unambiguously, a success. It has produced a system with high intercity rail ridership; in Europe, only Switzerland has unambiguously more passenger-km/capita (Austria is a near-tie, and the Netherlands doesn’t report this data). It has done so financially sustainably, with low construction costs and, therefore, operating profits capable of paying back construction costs, even though the newer lines have lower rates of return than the original LGV Sud-Est.

This success brought in imitators, comprising mostly countries that looked up to France in the 1990s and 2000s; Germany never built such a system, having always looked down on it. In the 2010s and 20s, the imitation ceased, partly due to saturation (Spain, Italy, and Belgium already had their own systems), partly because the mediocre economic growth of France reduced its soft power, and partly because the political mood in Europe shifted from state-built infrastructure projects to on-rail private competition. I wrote three years ago about the different national traditions of building high-speed rail, but here it’s best to look not at the features of the TGV today but at those of 15 years ago:

- High average speed, averaging around 230 km/h between Paris and Marseille; this was the highest in the world until China built out its own system, slightly faster than the Shinkansen and much faster than the German, Korean, and Taiwanese systems. Under-construction lines that have opened since have been even faster, reaching 260 km/h between Paris and Bordeaux.

- Construction on cut-and-fill, with passenger-only lines with steep grades (a 300 km/h train can climb 3.5% grades just fine), limited use of viaducts and tunnels, and extensive public outreach including land swap deals with farmers and overcompensation of landowners in order to reduce NIMBY animosity.

- Direct service to the centers of major cities, using classical lines for the last few kilometers into Paris and most other major cities; cities far away from the network, such as Toulouse and Nice, are served as well, on classical lines with the trains often spending hours at low speed in addition to their high-speed sections.

- Extensive branching: every city of note has its own trains to Paris.

- Little seat turnover: trains from Paris to Lyon do not continue to Marseille and trains from Paris to Marseille do not stop at Lyon, in contrast with the Shinkansen or ICE, which rely on seat turnover and multiple major-city stops on the same train.

- Open platforms: passengers can get on the platform with no security theater or ticket gates, and only have to show their ticket on the train to a conductor. This has changed since, and now the platforms are increasingly gated, though there is still no security theater.

- No fare differentiation: all trains have the same TGV brand, and charge similar fares as the few remaining slow intercity trains, on average much lower than on the Shinkansen. Fares do depend on airline-style buckets including when and how one books a train, and on service class, but there is no premium for speed or separation into high- and low-fare trains. This has also changed since, as SNCF has sought to imitate low-cost airlines and split the trains into the high-fare InOui brand and low-fare OuiGo brand, differentiated in that OuiGo sometimes doesn’t go into traditional city stations but only into suburban ones like Marne-la-Vallée, 25 minutes from Paris by RER. However, InOui and OuiGo are still not differentiated by speed.

SNCF management’s own beliefs on how trains should operate clearly differ from how TGVs actually did operate in the 1990s and 2000s, when the system was the pride of Europe. Evidently, they have introduced fare differentiation in the form of the InOui-OuiGo distinction, and ticket-gated the platforms. The aim of OuiGo was to imitate low-cost airlines, one of whose features is service at peripheral airports like Beauvais or Stansted, hence the use of peripheral train stations. However, even then, SNCF has shown some flexibility: it is inconvenient when a train unloads 1,000 passengers at an RER station, most of whom are visitors to the region and do not have a Navigo card and therefore must queue at ticket vending machines just to connect; therefore, OuiGo has been shifting to the traditional Parisian terminals.

However, the imitators have never gotten the full package outlined above. They’ve made some changes, generally in the direction of how SNCF management and the consultants who come from that milieu think trains ought to run, which is more like an airline. The preference for direct trains and no seat turnover has been adopted into Spain and Italy, and the use of classical lines to go off-corridor has been adopted as well, not just into standard-gauge imitators but also into broad-gauge Spain, using some variable-gauge trains. In contrast, the lack of fare differentiation by speed did not make it to Spain. Fast trains charge higher fares than slow trains, and before the opening of the market to private competition, RENFE ran seven different fare/speed classes on the Madrid-Barcelona lines, with separate tickets.

Ridership, as a result, was disappointing in Spain and Italy. The TGV had around 100 million annual passengers before the Great Recession, and is somewhat above that level today, thanks to the opening of additional lines. The AVE system has never been close to that. The high-speed trains in Italy, a country with about the same population as France, have been well short of the TGV’s ridership as well. Relative to metro area size, ridership in both countries on the city pairs for which I can find data was around half as high as on the TGV. Private competition has partly fixed the problem on the strongest corridors, but nationwide ridership in Spain and Italy remains deficient.

The issue in Spain in particular is that while the construction efficiency is even better than in France, management bought what France said trains should be like and not what French trains actually are. The French rail network is not the dictatorship of SNCF management. Management has to jostle with other interest groups, such as labor, NIMBY landowners, socialist politicians, (right-)liberal politicians, and EU regulators. It hates all of those groups for different reasons and can find legitimate reasons why each of those groups is obstructionist, and yet at least some of those groups are evidently keeping it honest with its affordable fares and limited market segmentation (and never by speed).

More generally, when learning from other places, it’s crucial not just to invite a few of their managers to your country to act as consultants. As familiar as they are with their own success, they still have their prejudices of how things ought to work, which are often not how they actually do work. Experience in the country in question is crucial; if you represent a peripheral country, you need to not just rely on consultants from a success case but also send your own people there to live as locals and get local impressions of how things work (or don’t), so that you can get what the success case actually is.

Amtrak Doubles Down on False Claims About Regional Rail History to Attack Through-Running

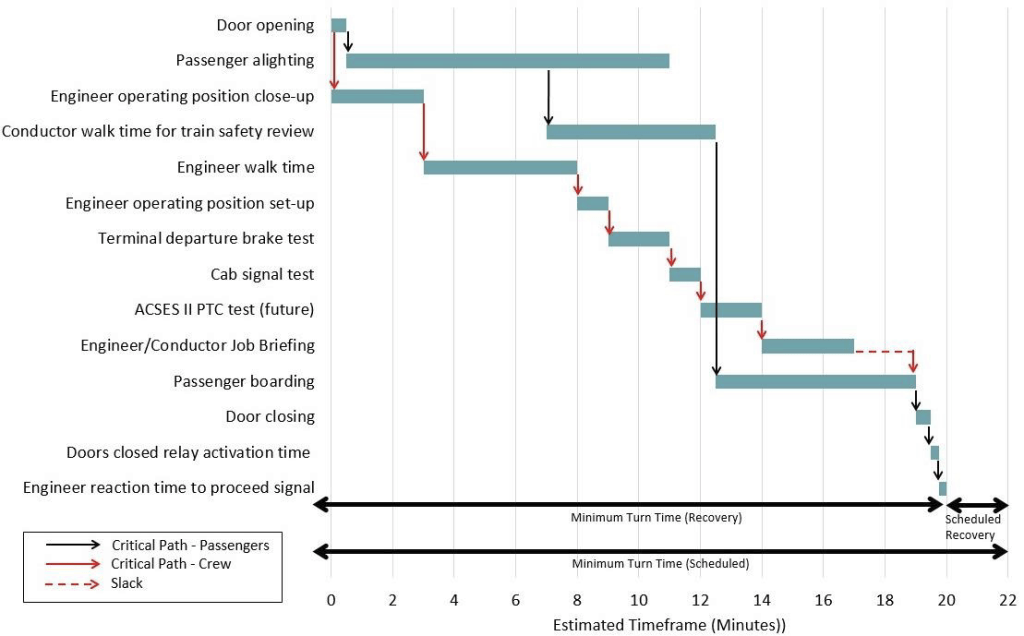

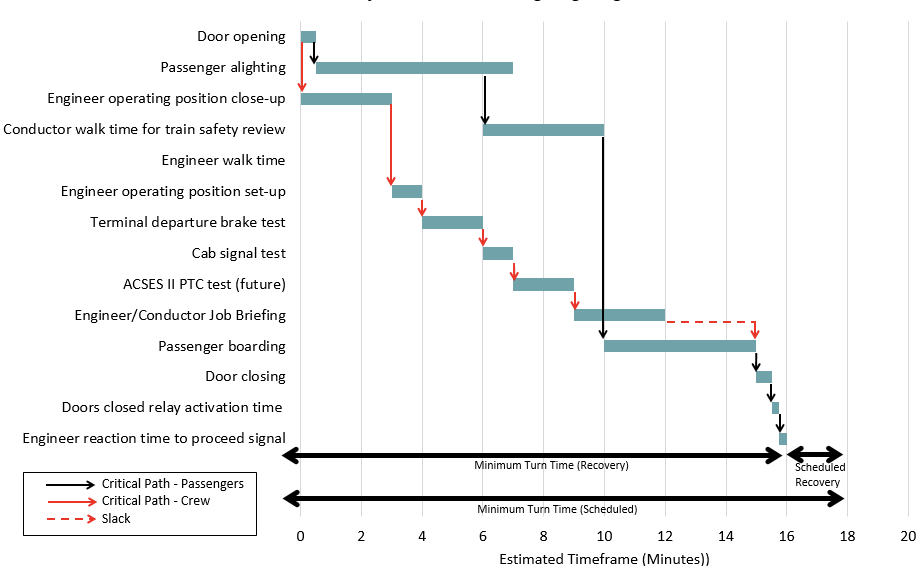

Amtrak just released its report a week and a half ago, saying that Penn Expansion, the project to condemn the Manhattan block south of Penn Station to add new tracks, is necessary for new capacity. I criticized the Regional Plan Association presentation made in August in advance of the report for its wanton ignorance of best practices, covering both the history of commuter rail through-running in Europe and the issue of dwell times at Penn Station. The report surprised me by making even more elementary mistakes on the reality of how through-running works here than the ones made in the RPA presentation. The question of dwell times is even more important, but the Effective Transit Alliance is about to release a report addressing it, with simulations made by other members; this post, in contrast, goes over what I saw in the report myself, which is large enough errors about how through-running works that of course the report sandbags that alternative, less out of malice and more out of not knowing how it works.

Note on Penn Expansion and through-running

In the regional discourse on Penn Station, it is usually held that the existing station definitely does not have the capacity to add 24 peak trains per hour from New Jersey once the Gateway tunnel opens, unless there is through-running; thus, at least one of through-running and Penn Expansion is required. This common belief is incorrect, and we will get into some dwell time simulations at ETA.

That said, the two options can still be held as alternatives to each other, even as what I think is likeliest given agency turf battles and the extreme cost of Penn Expansion (currently $16 billion) is that neither will happen. This is for the following reasons:

- Through-running is good in and of itself, and any positive proposal for commuter rail improvements in the region should incorporate it where possible, even if no dedicated capital investment such as a Penn Station-Grand Central connection occurs. This includes the Northeast Corridor high-speed rail project, which aims to optimize everything to speed up intercity and commuter trains at minimal capital cost.

- The institutional obstacles to through-running are mainly extreme incuriosity about rest-of-world practices, which are generations ahead of American ones in mainline rail; the same extreme incuriosity also leads to the belief that Penn Expansion is necessary.

- While it is possible to turn 48 New Jersey Transit trains per hour within the current footprint of Penn Station with no loss of LIRR capacity, there are real constraints on turnaround times, and it is easier to institute through-running.

The errors in the history

The errors in the history are not new to me. My August post criticizing the RPA still stands. I was hoping that Amtrak and the consultants that prepared the report (WSP, FX) would not stick to the false claim that it took 46 years to build the Munich S-Bahn rather than seven, but they did. The purpose of this falsehood in the report is to make through-running look like a multigenerational effort, compared with the supposedly easier effort of digging up an entire Manhattan block for a project that can’t be completed until the mid-2030s at the earliest.

In truth, as the August post explains, the real difficulties with through-running in the comparison cases offered in the report, Paris and Munich, were with digging the tunnels. This was done fairly quickly, taking seven years in Munich and 16 in Paris; in Paris, the alignment, comprising 17 km of tunnel for the RER A and 2 for the initial section of the RER B, was not even finalized when construction began. The equivalent of these projects in New York is the Gateway tunnel itself, at far higher cost. The surface improvements required to make this work were completed simultaneously and inexpensively; most of the ones required for New York are already on the drawing board of New Jersey Transit, budgeted in the hundreds of millions rather than billions, and will be completed before the tunnel opens unless the federal government decides to defund the agency over several successive administrations.

The errors in present operations

The report lists, on printed-pp. 40-41, some characteristics of the through-running systems used in Paris, Munich, and London. Based on those characteristics, it concludes it is not possible to set up an equivalent system at Penn Station without adding tracks or rebuilding the entire track level with more platforms. Unfortunately for the reputation of the writers of the report, and fortunately for the taxpayers of New York and New Jersey, those characteristics include major mistakes. There’s little chance anyone in the loop understands the RER, any S-Bahn worth the name, or even Crossrail and Thameslink; some of the errors are obviously false to anyone who regularly commuted on any of these systems. Thus, they are incapable of adjusting the operations to the specifics of Penn Station and Gateway.

Timetabling

A key feature of S-Bahn systems is that the trains run on a schedule. Passengers riding on the central trunk do not look at the timetable, but passengers riding to a branch do. I memorized the 15-minute off-peak Takt on the RER B when I took it to IHES in late 2016, and the train was generally on time or only slightly delayed, never so delayed that it was early. Munich-area suburbanites memorize the 20-minute Takt on their S-Bahn branch line. Some Thameslink branches drop to half-hourly frequency, and passengers time themselves to the schedule while operators and dispatchers aim to make the schedule.

And yet, the report repeatedly claims that these systems run on headway management. The first claim, on p. 40, is ambiguous, but the second, on the table on p. 41, explicitly contrasts “headway-based” with “timetable-based” service and says that Crossrail, the RER, and the Munich S-Bahn are headway-based. In fact, none of them is.

This error is significant in two ways. First, timetable-based operations explain why S-Bahn systems are capable of what they do but not of what some metros do. The Munich S-Bahn peaks at 30 trains per hour, with one-of-a-kind signaling; major metros peak at 42 trains per hour with driverless operations, and some small operations with short trains (like Brescia) achieve even more. The difference is that commuter rail systems are not captive metro trains on which every train makes the same stops, with no differentiation among successive trains on the same line; metro lines that do branch, such as M7 and M13 in Paris, are still far less complex than even relatively simple and metro-like lines like the RER A and B. The main exception among world metros is the New York City Subway, which, due to its extensive interlining, must run as a scheduled railroad, benchmarking its on-time performance (OTP) to the schedule rather than to intervals between trains. In the 2000s and 10s, New York City Transit tried to transition away from end-station OTP and toward a metric that tried to approximate even intervals, called Wait Assessment (WA); a document leaked to Dan Rivoli and me went over how this was a failure, leading to even worse delays and train slowdowns, as managers would make the dispatchers hold trains if the trains behind them were delayed.

The second consequence of the error is that the report does not get how crucial timetable-infrastructure planning integration is on mainline rail. The Munich S-Bahn has outer branches that are single-track and some that share tracks with freight, regional, and intercity trains. The 30 tph trunk does no such thing and could not do such thing, but the branches do, because the trains run on a fixed timetable, and thus it is possible to have a mix of single and double track on some sporadic sections. The Zurich S-Bahn even runs trains every 15 minutes at rush hour on a short single-track section of the Right Bank of Lake Zurich Line. Recognizing what well-scheduled commuter trains can and can’t do influences infrastructure planning on the entire surface section, including rail-on-rail grade separations, extra tracks, yard expansions, and other projects that collectively make the difference between a rail network and crayon.

Separation between through- and terminating lines

Through-running systems vary in how much track sharing there is with the rest of the mainline rail network. As far as I can tell, there is always some; near-complete separation is provided on the RER A, but its Cergy branch also hosts Transilien trains running to Gare Saint-Lazare at rush hour, and the Berlin and Hamburg S-Bahn systems have very little track-sharing as well. Other systems have more extensive track sharing, including Thameslink, the RER C and D, and the Zurich S-Bahn; the RER E and the Munich S-Bahn are intermediate in level of separation between those two poles.

It is remarkable that, while the RER A, B, and E all feature new underground terminals for dedicated lines, the situation of the RER C and D is different. The RER C uses the preexisting Gare d’Austerlitz, and has taken over every commuter line in its network; the through-connection between Gare d’Orsay and Gare d’Invalides involved reconstructing the stations, but then everything was connected to it. The RER D uses prebuilt underground stations at Gare du Nord, Les Halles, and Gare de Lyon, but then takes over nearly all lines in the Gare de Lyon network, with the outermost station, Malesherbes, not even located in Ile-de-France. Thameslink uses through-infrastructure built in the 1860s and runs as far as Petersborough, 123 km from King’s Cross on the East Coast Main Line, and Brighton, the terminus of its line, 81 km from London Bridge.

And yet, the report’s authors seem convinced the only way to do through-running is with a handful of branches providing only local service, running to new platforms built separately from the intercity terminal; they’re even under the impression the RER D is like this, which it is not. There’s even a map on p. 45, suggesting a regional metro system running as far as Hicksville, Long Beach, Far Rockaway, JFK via the Rockaway Cutoff and Queenslink, Port Washington, Port Chester, Hackensack, Paterson, Summit, Plainfield, New Brunswick, and the Amboys. This is a severe misunderstanding of how such systems work: they do not arbitrarily slice lines this way into inner and outer zones, unless there is a large mismatch in demand, and then they often just cut the outer end to a shuttle with a forced transfer, as is the case for some branches in suburban Berlin connecting to S-Bahn outer ends. Among the above-mentioned outer ends, the only one where this exception holds is Summit, where the Gladstone Branch could be cut to a shuttle or to trains only running to Hoboken – but then trains on the main line to Morristown and Dover have no reason to be treated differently from trains to Summit.

Were the report’s authors more informed about just the specific lines they look at on p. 41, let alone the broader systems, they’d know that separation between inner and outer services is contingent on specifics of track infrastructure, including whether there are four-track lines with neat separation into terminating express trains and through locals. But even if the answer is yes, as at Gare de Lyon and Gare d’Austerlitz, infrastructure planners will attempt to shoehorn whatever they can into the system, just starting from the more important inner lines, which generate more all-day demand. There don’t even need to be terminating regional trains; the Austerlitz system doesn’t, and the Gare de Lyon and Gare de l’Est systems only do due to trunk capacity limitations. In that case, they’d recognize that there is no need to have two commuter rail systems, one through-running and one not. Penn Station’s infrastructure already lends itself to allowing through-running on anything entering via the existing North River Tunnels.

Branching

S-Bahn systems usually try to keep the branch-to-trunk ratio to a manageable number. Usually, more metro-like systems have fewer branches: Crossrail has two on each side, the RER A has two to the east and three to the west, the Berlin Stadtbahn has two to the west plus short-turns and five to the east, the Berlin North-South Tunnel has three on each side. The Munich S-Bahn has five to the east and nine to the west, and the combined RER B and D system has three to the north and five to the south, but the latter has more service patterns, including local and express trains on the branches. Zurich has so much interlining that it’s not useful to count branches, and better to count services: there are 21 S-numbered routes serving Hauptbahnhof, of which 13 run through one of the two tunnels, as do some intercity trains.

If there are too many branches, then they’re usually organized as sub-branches – for example, Munich has seven numbered routes through the central tunnel, of which two have two sub-branches each splitting far out. Zurich has fewer than 13 branches on each side, but rather there are several services using each line, with inconsistent through-pairing – for example, the three services going to the airport, S2, S24, and S16, respectively run through to two separate branches of the Left Bank Line and to the Right Bank Line.

The table on p. 41 gets the branch count mildly wrong, but the significant is less in what it gets wrong about Europe and more in what it gets wrong about New York. A post-Gateway service plan is one in which New Jersey has 12 branches, but some can be viewed as sub-branches (like Gladstone and the Morristown Line), and more to the point, there are going to be two trunk lines. The current plan at New Jersey Transit is to assign the Northeast Corridor and North Jersey Coast Lines to the North River Tunnels alongside Amtrak, which is technically two branches but realistically four or even five service patterns, and the Morris and Essex, Montclair-Boonton, and Raritan Valley Lines to Gateway, which is four branches but could even be pruned to three with M&E divided into two sub-branches. The Erie lines have no way of getting to Penn Station today; to get them there requires the construction of the Bergen Loop at Secaucus, with an estimated budget of $1.3 billion in 2020, comparable to the total cost of all yet-unfunded required surface improvements in New Jersey for non-Erie service combined.

If the study authors were more comfortably knowledgeable of European S-Bahn systems, they’d know that multi-line systems, while uncommon, do exist, and divide branches in a similar way. The multiline systems (Paris, Madrid, Berlin, Zurich, and London) all have some reverse-branching, in a similar manner to how New York is soon going to have the New Haven Line reverse-branch to Penn Station and Grand Central. The NJT plan is solid and stands to lead to a manageable branch-to-trunk ratio, even with every single line going to Penn Station via the existing tunnel running through.

The consequence of the errors

The lack of familiarity with through-running commuter rail is evident in how the report talks about this technology. It is intimately related to the fact that the way investment should be done is different from what American railroaders are used to. For one, there needs to be much tighter integration between infrastructure and scheduling. For two, the scheduling needs to be massively simplified, with fewer operating patterns per line – usually one, occasionally two, never 13 as on the New Haven Line today. The same ignorance that leads Amtrak and its consultants to assert that the S-Bahn runs on headway management rather than a fixed timetable also leads them not to even know how through-running commuter rail networks plan out their routes and services.

From my position of greater familiarity as both a regular user and a researcher, I can point out that the required investments to make through-running happen in New York are entirely in line with the cheap surface projects done in the comparison cases. New rolling stock is required, with the ability to run on the different voltages of the three networks – but multi-voltage commuter rolling stock is the norm wherever multiple legacy electrification systems coexist, including Paris, London, and Hamburg. Some extensions of electrification and high platform conversions are required – but these are not expensive, and the latter is already partly funded at reasonable unit costs. Some rail-on-rail grade separations are required – but those are already costed and very likely to be funded, potentially out of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Penn Station would be used as the universal station in this schema, without the separation into a surface terminal and a through- underground station seen in Munich and Paris. But then, Paris and Munich don’t even universally have this separation themselves; Ostbahnhof was reconstructed for the S-Bahn but is still a single station, and the same is true of the RER C. In a way, Penn Station already is the underground through-station, built generations before the modern S-Bahn concept, complementing and largely replacing surface terminals like Hoboken and Long Island City because those are not in Manhattan.

None of this is hard; the hard part is the Gateway tunnel and that’s already fully funded and under construction. But it does require understanding that the United States is so many decades behind best practices that none of what American railroaders think they know is at all relevant. It’s obligatory to understand how the systems that work, in Europe and rich Asia, do, because otherwise, it’s like expecting someone who has never learned to count beyond 10 to prove mathematical theorems. The people who wrote this report clearly don’t have this understanding, and don’t care to get it, which is why what they write is not worth the electrons that make up the PDF.

InnoTrans is Souring Me on On-Rail Competition

I’m at InnoTrans this week, which means I get to both see a lot of new trainsets and talk to vendors for things I am interested in. Those are interesting conversations and much of the content will make it to our upcoming report on high-speed rail in the Northeast and to some ETA reports. But then, in broad stroke, the presentations about the trains here have deeply bothered me, because of how they interact with the issue of on-rail competition. The EU has an open access mandate, so that state-owned and private railways can compete by running trains on tracks throughout the Union, with separation of operations and infrastructure (awkwardly, state railways do both but there are EU regulations prohibiting favoritism, with uneven enforcement). As a result, I’m seeing a lot of pitches geared specifically for potential open access operators, all of which remind me why I’m so negative about the whole concept: it treats infrastructure as a fixed thing and denigrates the idea that it could ever be improved, while enthroning airline-style business analysis.

Proponents of the model cite higher ridership and lower fares due to the introduction of competition in Italy and Spain, but even then, it’s never really invented anything new, and only gotten some city pairs in those two countries to the service quality that integrated state-provided services have always had in France and Germany. In effect, the EU is mandating a dead-end system of managing trains and making a collective decision not to invest in what worked – namely, building and running high-speed lines.

For people unfamiliar with the argument, I wrote a year ago about TGV ridership and traffic modeling. The TGV overperforms a model trained on Shinkansen ridership, which can be explained based on lower fares, leisure travel to the Riviera, and underdeveloped air competition in small metro areas whose residents mostly drive to larger ones to fly. Relative to the same model, Italian and Spanish ridership underperformed the TGV before competition, and rose to roughly match the TGV or be slightly deficient after competition. So competition did lead to growth in ridership, as the competitors added service and lowered fares – but it only created what the French state did by itself. The German state seems to have French-like results: the trains here are much slower than in France, but relative to that, ridership seems to be in line with a TGV-trained model on the handful of city pairs for which I have any data.

This is causing quite a lot of the buzz in the intercity rail industry in Europe to center cross-border competition and new entrants. But this is, judging by the examples the proponents of competition look up to, not creating anything new. It’s not moving rail forward. It’s just filling in gaps that some state-owned railways – but not the largest two – have in their operations.

And worse, it’s making the long-term issues of intercity rail in Europe worse. There’s practically no cross-border high-speed rail construction in Europe, nor any serious push for making it happen. After a great deal of activism by Jon Worth (and others), the European Commission is announcing regulatory measures in its agenda, starting with passenger rights in case of delays. Physical construction is nowhere on the horizon, nor is there any serious advocacy for (say) a Paris-Frankfurt high-speed line or a Bordeaux-Basque Country one. This is a recent development: in the 2000s there was more optimism about high-speed rail, leading to plans like Perpignan-Figueres. But since then, the TEN-T corridor plans turned into low-speed lines and vaporware, and there’s no real interest in fixing that.

Instead, the interest is in letting the private sector lead. State-built high-speed railways – more or less the only high-speed railways – are not in fashion. The private sector is not going to step in and build its own (despite the sad Hyperloop capsule on display at InnoTrans), but instead look for underserved city pairs to come into, competing with state railways. It’s a story of business analysts using techniques brought in from the airline industry rather than one of infrastructure builders.

And it’s exactly those airline-imitating business analysts who are why RENFE, FS, and Eurostar underprovided service to begin with. The airline world lives off of segmenting the market; there are periodic attempts at all-business class airlines, and low-cost carriers entering and exiting the market frequently. It does not build its own infrastructure, not think in terms of things that could work if the infrastructure were a little bit better. A railway that thinks in the same terms might still build, but will not build in coordination with what it runs. It will do the exact opposite of what Switzerland has done with its tight integration of infrastructure and operations planning; therefore, it will get results inferior to those of Switzerland or even France and Germany.

The trains on display at InnoTrans announce proudly that they are homologated for cross-border travel, listing the countries they can operate in. The main high-speed rail vendors here – Siemens, Hitachi, Talgo, Alstom – all talk about this, explicitly; Alstom had a presentation about the Avelia Horizon, awkwardly given in an American accent while talking about how the double-decker cars with 905 mm seat pitch (Shinkansen: 1 meter) minimize track access charges per seat.

In contrast, I have not seen anything about building new lines. I have not seen booths by firms talking about their work building LGVs or NBSes. I have not seen anything by ADIF selling its expertise in low-cost construction; there are some private engineering consultants with booths, but I haven’t seen ADIF, and the French state section of the conference didn’t at all center French construction techniques. The states that have figured out how to build high-speed rail efficiently seem uninterested in doing more with it than just completing their capital-to-provinces networks; even Germany is barely building. Naturally, they’re also uninterested in pitching their construction, even though they do do some public-sector consulting (SNCF does it routinely for smaller French cities). It’s as if the construction market is so small they’re not even going to bother.

Every other booth at the conference talks about innovation with so many synonyms that they swamp what the firm actually does. But beneath the buzzwords, what I’m seeing, at least as far as physical infrastructure goes, is the exact opposite of innovation. I’m seeing filling in small gaps caused by last generation’s bad airline imitation with a different kind of airline imitation, and nothing that moves intercity rail forward.

The MTA Capital Plan Falsifies Subway History

The 2025-29 capital plan is out, and it is not good. There’s an outline of an ETA report to be released soon going over issues like accessibility, rolling stock costs, and the new faregates. But for now, I’d like to just focus on a high-level issue and how it relates to the subway’s history: State of Good Repair. The capital plan has a summary history of past capital plans on PDF-page 8, and it calls the 1990s and 2000s an era of underinvestment and deferred maintenance, the exact opposite of reality. It treats 2017 as a keystone year for system renewal, which it was not; it was, however, the year current MTA chair Janno Lieber was hired as the head of MTA Construction and Development (formerly Capital Construction). In effect, the plan falsifies the history of the system in order to treat the current leadership as saviors, in service of a plan to spend more money than in 2020-24 while having less to show for it, washing it all with the nebulous promise of State of Good Repair.

The history of State of Good Repair

Traditionally, capital investment is conceived as going to expansion. In New York in the first two thirds of the 20th century, this meant new subway and elevated lines, new connections between subway lines, station upgrades to lengthen the platforms, and new transfers between stations that had previously belonged to different operators. Maintenance was treated as an ongoing expense.

The finances of the subway after WW1 were shaky, and from the Depression onward, it never made money again. Of the two private operators, one, the IRT, was in bankruptcy protection during the Depression, while the public operator, the IND, was debt-ridden due to exceptionally high construction costs for that era and overbuilding. This made it attractive to defer maintenance, on the subway as on mainline rail everywhere in the United States. In 1951, bond money was designated for Second Avenue Subway, but then the money was raided for other priorities, including smaller extensions but also capital renewal, such as replacing the almost 50-year-old IRT rolling stock fleet.

In the 1970s, the city’s poor finances meant it couldn’t subsidize operations and maintenance as much as before, and the maintenance deferral led to a systemwide collapse. NYCSubway.org goes over the various elements of it: chunks of equipment and material were falling onto the street from the elevated lines, and onto the tracks from the retaining walls of open cuts; trains had flat wheels and no lubrication, leading to such squeal that the noise was worse than that of Concorde; train doors and lights malfunctioned; derailments and fires were common. By 1981, the mean distance between failures (MDBF) dropped to its lowest ever, 6,640 miles (10,690 km). One third of the system was under emergency 10 mph speed restrictions, and a quarter of the rolling stock had to be kept in reserve to substitute for equipment failures and could not be run in maximum revenue service. The new trains bought for the system, the R44 and R46, used new technology, for example higher top speed for the use on long express sections, but were defective to the point that the lawsuits against the vendors, St. Louis and Pullman respectively, bankrupted them. The origin of the conservatism of rolling stock orders and the pattern that all American rolling stock manufacture is done at transplant factories owned by European, Japanese, or formerly Canadian firms, are both the result of this history.

The State of Good Repair program as we know it dates to the 1980s, when the MTA, starting with the leadership of Richard Ravitch, began to prioritize maintenance and renewal over expansion. This meant five-year capital programs, to reduce the incentives to defer maintenance in a single year, and a lot of openly crying poverty, where leaders both before and after Ravitch would prefer to extoll the system and downplay its shortcomings. There was large spending on capital as a result, but no Second Avenue Subway. Instead, money went to renewal. Rolling stock was more conservative; the R62 was also imported from Japan, since Reagan cut federal aid to mass transit and so the MTA was free from Buy America’s strictures (in contrast, today states prefer to preemptively obey even when they’re not sure they will get federal funding, and even demand in-state plants). Its mean distance between failures was far higher than that of all other rolling stock, and this greater reliability continued into the R62A, R68, and R68A orders; the systemwide mean distance between failures kept climbing throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, to a peak of around 180,000 miles, or around 280,000 km, in 2005 and again in 2010-11. The slow restrictions that characterized the system in the 1970s were lifted, and rolling stock availability for maximum service rose.

The construction of Second Avenue Subway beginning in 2007 was not viewed as a rebuke to the SOGR program, but rather as the legacy of its success. Leaders like Lee Sander spoke of growth and new lines, setting the stage for what is now known as IBX and was known in then as Triboro RX. The political discourse in the United States at the time was one of transit revival, due to the then-new decoupling of car driving and oil use from economic growth, and the high fuel prices; this was also around the time American discourse discovered European and Japanese high-speed rail, setting the stage for Proposition 1A approving the construction of California High-Speed Rail in 2008.

The present of State of Good Repair

I’ve repeatedly criticized SOGR as a scheme allowing agency heads to demand money with nothing to show for it. The behavior of current MTA leadership is one such example; it is not the only one – Amtrak did the same under Joe Boardman in the 2000s. But it needs to be made clear that the SOGR program of the 1980s and 90s was an unmitigated success. There was visible improvement in the system due to better maintenance of fixed plant and more prudent capital investments, such as the trainsets bought in the era from the R62 to the R160. The present problems of the SOGR concept come essentially because its success in the 1980s and 90s led agencies to talk about it as the next hot thing, even while going in a rather different direction.

In the 2010s, the subway started facing new problems – but these were not problems of undermaintenance. The MDBF crept down to a little less than 120,000 miles at the bottom, in 2017, and was 125,000 miles in 2023. The oldest trains are the worst, but much of the problem comes from other issues than slow replacement of fixed plant. For example, the ongoing slowdowns on the subway – even in the 2000s it was slower than before the 1970s collapse, and speeds are noticeably lower when I visit than when I lived in the city in 2006-11 – come not from insufficient maintenance, but from tighter flagging rules, which are designed to protect workers on adjacent track, but in fact have coincided with more worker injuries than in 1999, with a particular deterioration in worker safety in the 2010s. Andy Byford’s Save Safe Seconds campaign was the right response to the slowdowns, and helped stop the bleeding.

And yet, the idea of SOGR persists, even though the problem it purported to solve has been solved. The worst offender is Amtrak: in the Obama stimulus, it asked for $10 billion for SOGR on the Northeast Corridor, promising trivial reductions in travel times; Amtrak’s chair at the time, Joe Boardman, was the very one who deferred maintenance in order to make Amtrak look more profitable on paper in the service of the Bush administration’s goal of eventual privatization, replacing David Gunn, who was fired because he refused to do so.