Tilting Trains and Technological Dead-Ends

The history of tilting trains is on my mind, because it’s easy to take a technological advance and declare it a solution to a problem without first producing it at scale. I know that 10 years ago I was a big fan of tilting trains in comments and early posts, based on both academic literature on the subject and existing practices. Unfortunately, this turned into a technological dead-end because the maintenance costs were too high, disproportionate to the real speed benefits, and further work has gone in different directions. I bring this up because it’s a good example of how even a solution that has been proven to work at scale can turn out to be a dead-end.

What is tilting?

It is a way of getting trains to run at higher cant deficiency.

What is cant deficiency?

Okay. Let’s derive this from physical first principles.

The lateral acceleration on a train going on a curve is given by the formula a = v^2/r. For example, if the speed is 180 km/h, which is 50 m/s, and the curve radius is 2,000 meters, then the acceleration is 50^2/2000 = 1.25 m/s^2.

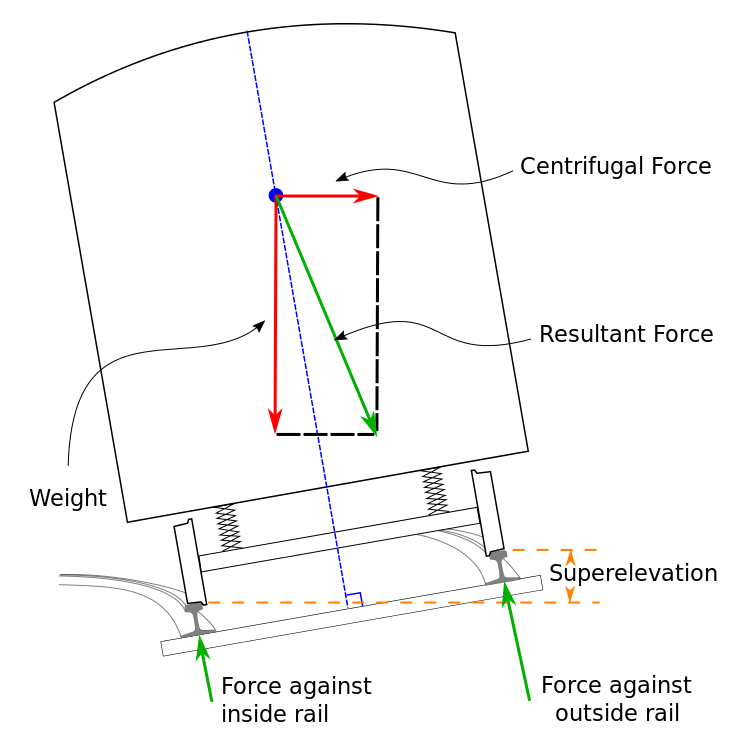

Now, on pretty much any curve, a road or railway will be banked, with the outer side elevated above the inner side. On a railway this is not called banking, but rather superelevation or cant. That way, gravity countermands some of the centrifugal force felt by the train. The formula on standard-gauge track is that 150 mm of cant equal 1 m/s^2 of lateral acceleration. The cant is free speed – if the train is perfectly canted then there is no centrifugal force felt by the passengers or the train systems, and the balance between the force on the inner and outer rail is perfect, as if there is no curve at all.

The maximum superelevation on a railway is 200 mm, but it only exists on some Shinkansen lines. More typical of high-speed rail is 160-180 mm, and on conventional rail the range is more like 130-160; moreover, if trains are expected to run at low speed, for example if the line is dominated by slow freight traffic or sometimes even if the railroad just hasn’t bothered increasing the speed limit, cant will be even lower, down to 50-80 mm on many American examples. Therefore, on passenger trains, it is always desirable to run faster, that is to combine the cant with some lateral acceleration felt by the passengers. Wikipedia has a force diagram:

The resultant force, the downward-pointing green arrow, doesn’t point directly toward the train floor, because the train goes faster than the balance speed. This is fine – some lateral acceleration is acceptable. This can be expressed in units of acceleration, that is v^2/r with the contribution of cant netted out, but in regulations it’s instead expressed in theoretical additional superelevation required to balance, that is in mm (or inches, in the US). This is called cant deficiency, unbalanced superelevation, or underbalance, and follows the same 150 mm = 1 m/s^2 formula on standard-gauge track.

Note also that it is possible to have cant excess, that is negative cant deficiency. This occurs when the cant chosen for a curve is a compromise between faster and slower trains, and the slower trains are so much slower the direction of the net force is toward the inner rail and not the outer rail. This is a common occurrence when passenger and freight trains share a line owned by a passenger rail-centric authority (a freight rail-centric one will just set the cant for freight balance). It can also occur when local and express passenger trains share a line – there are some canted curves at stations in southeastern Connecticut on the Northeast Corridor.

The maximum cant deficiency is ordinarily in the 130-160 mm range, depending on the national regulations. So ordinarily, you add up the maximum cant and cant deficiency and get a lateral acceleration of about 2 m/s^2, which is what I base all of my regional rail timetables on.

You may also note that the net force vector is not just of different direction from the vertical relative to the carbody but also of slightly greater magnitude. This is an issue I cited as a problem for Hyperloop, which intends to use far higher cant than a regular train, but at the scale of a regular train, it is not relevant. The magnitude of a vector consisting of a 9.8 m/s^2 weight force and a 2 m/s^2 centrifugal force is 10 m/s^2.

Okay, so how does tilt interact with this?

To understand tilt, first we need to understand the issue of suspension.

A good example of suspension in action is American regulations on cant deficiency. As of the early 2010s, the FRA regulations depend on train testing, but are in practice, 6″, or about 150 mm. But previously the blanket rule was 3″, with 4-5″ allowed only by exception, mocked by 2000s-era advocates as “the magic high-speed rail waiver.” This is a matter of carbody suspension, which can be readily seen in the force diagram in the above secetion, in which the train rests on springs.

The issue with suspension is that, because the carbody is sprung, it is subject to centrifugal force, and will naturally suspend to the outside of the curve. In the following diagram, the train is moving away from the viewer and turning left, so the inside rail is on the left and the the outside rail is on the right:

The cant is 150 mm, and the cant deficiency is held to be 150 mm as well, but the carbody sways a few degrees (about 3) to the outside of the curve, which adds to the perceived lateral acceleration, increasing it from 1 m/s^2 to about 1.5. This is typical of a modern passenger train; the old FRA regulations on the matter were based on an experiment from the 1950s using New Haven Railroad trains with unusually soft suspension, tilting so far to the outside of the curve that even 3″ cant deficiency was enough to produce about 1.5 m/s^2 of lateral force felt by the passengers.

By the same token, a train with theoretically perfectly rigid suspension could have 225 mm of cant deficiency and satisfy regulators, but such a train doesn’t quite exist.

Here comes tilt. Tilt is a mechanism that shifts the springs so that the carbody leans not to the outside of the curve but to its inside. The Pendolino technology is theoretically capable of 300 mm of cant deficiency, and practically of 270. This does not mean passengers feel 1.8-2 m/s^2 of lateral acceleration; the train’s bogies feel that, but are designed to be capable of running safely, while the passengers feel far less. In fact the Pendolino had to limit the tilt just to make sure passengers would feel some lateral acceleration, because it was capable of reducing the carbody centrifugal force to zero and this led to motion sickness as passengers saw the horizon rise and fall without any centrifugal force giving motion cues.

Two lower cant deficiency-technology than Pendolino-style tilt are notable, as those are not technological dead-ends, and in fact remain in production. Those are the Talgo and the Shinkansen active suspension. The Talgo has no axles, and incorporates a gravity-based pendular system in which the train is sprung not from the bottom up but from the top down; this still isn’t enough to permit 225 mm of cant deficiency, but high-speed versions like the AVRIL permit 180, which is respectable. The Shinkansen active suspension is computer-controlled, like the Pendolino, but only tilts 2 degrees, allowing up to 180 mm of cant deficiency.

What is the use case of tilting, then?

Well, the speed is higher. How much higher the speed is depends on the underlying cant. The active tilt systems developed for the Pendolino, the Advanced Passenger Train, and ICE T are fundamentally designed for mixed-traffic lines. On those lines, there is no chance of superelevating the curves 200 mm – one freight locomotive at cant excess would demolish the inner track, and the freight loads would shift unacceptably toward the inner rail. A more realistic cant if there is much slow freight traffic is 80 mm, in which case the difference between 150 and 300 mm of cant deficiency corresponds to a speed ratio of .

Note that the square root in the formula, coming from the fact that acceleration formula contains a square of the speed, means that the higher the cant, the less we care about cant deficiency. Moreover, at very high speed, 300 mm of cant deficiency, already problematic at medium speed (the Pendolino had to be derated to 270), is unstable when there is significant wind. Martin Lindahl’s thesis, the first link in the introduction, runs computer simulations at 350 km/h and finds that, with safety margins incorporated, the maximum feasible cant deficiency is 250 mm. On dedicated high-speed track, the speed ratio is then , a more modest ratio than on mixed track.

The result is that for very high-speed rail applications, Pendolino-level tilting was never developed. The maximum cant deficiency on a production train capable of running at 300 km/h or faster is 9″ (230 mm) on the Avelia Liberty, a bespoke train that cost about double per car what 300 km/h trains cost in Europe. To speed up legacy Shinkansen lines, JR Central and JR East have developed active suspension, stretching the 2.5 km curves of the Tokaido Shinkansen from the 1950s and 60s to allow 285 km/h with the latest N700 trains, and allowing 360 km/h on the 4 km curves of the Tohoku Shinkansen.

What happened to the Pendolino?

The Pendolino and similar trains, such as the ICE T, have faced high maintenance costs. Active tilting taxes the train’s mechanics, and it’s inherently a compromise between maintenance costs and cant deficiency – this is why the Pendolino runs at 270 mm where it was originally capable of 300 mm. The Shinkansen’s active suspension is explicitly a compromise between costs and speed, tilted toward lower cant deficiency because the trains are used on high-superelevation lines. The Talgo’s passive tilt system is much easier to maintain, but also permits a smaller tilt angle.

The Pendolino itself is a fine product, with the tilt removed. Alstom uses it as its standard 250 km/h train, at lower cost than 350 km/h trains. It runs in China as CRH5, and Poland bought a non-tilting Pendolino fleet for its high-speed rail service.

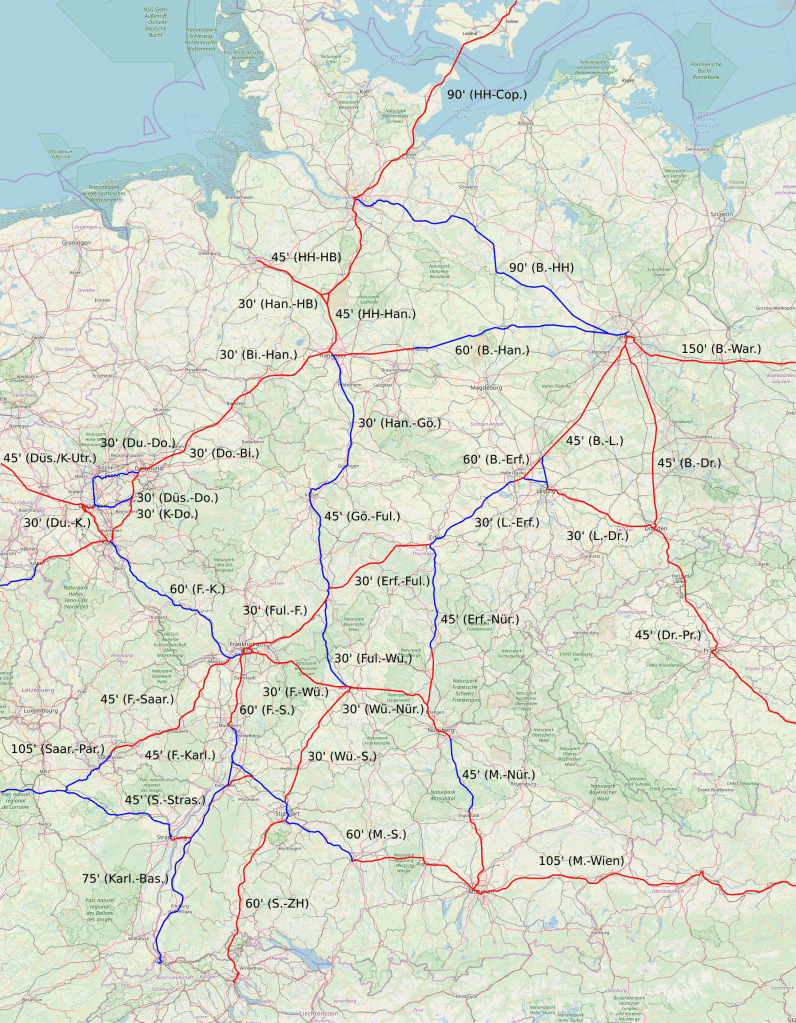

Other medium-speed tilt trains still run, but the maintenance costs are high to the point that future orders are unlikely to include tilt. Germany has a handful of tilt trains included in the Deutschlandtakt, but the market for them is small. Sweden is happy with the X2000, but its next speedup of intercity rail will not involve tilting trains on mostly legacy track as Lindahl’s thesis investigated, but conventional non-tilting high-speed trains on new 320 km/h track to be built at a cost that is low by any global standard but still high for how small and sparsely-populated Sweden is.

In contrast, trainsets with 180 mm cant deficiency are still going strong. JR Central recently increased the maximum speed on the Tokaido Shinkansen from 270 to 285 km/h, and Talgo keeps churning out equipment and exports some of it outside Spain.