Category: Good Transit

I’m Giving a Webinar Talk About Penn Station

The model that I’ve been blogging about is going to be the subject of a Zoom webinar, on Thursday 9-28, at 19:00 Berlin time or 13:00 New York time.

The talk will be in conversation with New York Daily News reporter and editor Michael Aronson, who has been very passionate in private conversations with us about improving rail service in the area and criticizing poor project management and high costs. In particular, he may yet save the Gateway Project three years, advancing capacity that much faster.

Specifically, the issue is that the existing tunnels between New Jersey and New York, the North River Tunnels, were heavily damaged in Hurricane Sandy, and require long-term repairs. The preferred alternative is long-term shutdowns of one track at a time, which is not possible until the Gateway tunnel (the Hudson Tunnel Project) is completed and would take a total of three years across both tracks then. The alternative is to do those repairs during weekend shutdowns. It is commonly believed that already there is repair work every weekend, and the timetables through the tunnel are written with the assumption that traffic can fit on a single track every weekend, giving a 55-hour shutdown period once a week. However, Michael found out that over a four-year period ending in 2020, the full shutdown for repairs was only done 13 times, or once every three months, and most of those shutdowns were not for repairing the tunnels themselves; in the following year, no shutdowns were done due to corona, and subsequently, the sluggish pre-corona rate has continued. If the repairs are done every weekend as the timetable permits, then it should be possible to wrap up simultaneously with the completion of the new tunnel, saving those three years of shutdown.

Penn Station 3D Model

As part of our high-speed rail program at Marron, I designed and other people made a 3D model of the train station I referenced in 2015 in what was originally a trollish proposal, upgraded to something more serious. For now there’s still a password: letsredothis. This is a playable level, so have a look around.

The playable 3D model shows what Penn Station could look like if it were rebuilt from the ground up, based on best industry practices. It is deliberately minimalistic: a train station is an interface between the train and the city it serves, and therefore its primary goal is to get passengers between the street or the subway and the platform as efficiently as possible. But minimalism should not be conflated with either architectural plainness (see below on technical limitations) or poor passenger convenience. The open design means that pedestrian circulation for passengers would be dramatically improved over today’s infamously cramped passageways.

Much of the design for this station is inspired by modern European train stations, including Berlin Hauptbahnhof (opened 2006), the under-construction Stuttgart 21 (scheduled to open 2025), and the reconstruction of Utrecht Central (2013-16); Utrecht, in turn, was inspired by the design of Shinagawa in Tokyo.

As we investigate which infrastructure projects are required for a high-speed rail program in the Northeast, we will evaluate the place of this station as well. Besides intangible benefits explained below in background, there are considerable tangible benefits in faster egress from the train to the street.

Moreover, the process that led to this blueprint and model can be reused elsewhere. In particular, as we explain in the section on pedestrian circulation, elements of the platform design should be used for the construction of subway stations on some lines under consideration in New York and other American cities, to minimize both construction costs and wasted time for passengers to navigate underground corridors. In that sense, this model can be viewed not just as a proposal for Penn Station, but also as an appendix to our report on construction costs.

Background

New York Penn Station is unpopular among users, and has been since the current station opened in 1968 (“One entered the city like a God; one scuttles in now like a rat” -Vincent Scully). From time to time, proposals for rebuilding the station along a better or grander design have been floated, usually in connection with a plan for improving the track level below.

Right now, such a track-level improvement is beginning construction, in the form of the Gateway Project and its Hudson Tunnel Project (HTP). The purpose of HTP is to add two new tracks’ worth of rail capacity from New Jersey to Penn Station; currently, there are only two mainline tracks under the Hudson, the North River Tunnels (NRT), with a peak throughput of 24 trains per hour across Amtrak’s intercity trains and New Jersey Transit’s (NJT) commuter trains, and very high crowding levels on the eve of the pandemic; 24 trains per hour is usually the limit of mainline rail, with higher figures only available on more self-contained systems. In contrast, going east of Penn Station, there are four East River Tunnel (ERT) tracks to Long Island and the Northeast Corridor, with a pre-corona peak throughput of not 48 trains per hour but only about 40.

Gateway is a broader project than HTP, including additional elements on both the New Jersey and Manhattan sides. Whereas HTP has recently been funded, with a budget of $14-16 billion, the total projected cost of Gateway is $50 billion, largely unfunded, of which $20 billion comprises improvements and additions to Penn Station, most of which are completely unnecessary.

Those additions include the $7 billion Penn Reconstruction and the $13 billion Penn Expansion. Penn Reconstruction is a laundry list of improvements to the existing Penn Station, including 29 new staircases and escalators from the platforms to the concourses, additional concourse space, total reconstruction of the upper concourse to simplify the layout, and new entrances from the street to the station. It’s not a bad project, but the cost is disproportionate to the benefits. Penn Expansion would build upon it and condemn the block south of the station, the so-called Block 780, to excavate new tracks; it is a complete waste of money even before it has been funded, as scarce planner resources are spent on it.

The 3D model as depicted should be thought of as an alternative form of Penn Reconstruction, for what is likely a similar cost. It bakes in assumptions on service, as detailed below, that assume both commuter and intercity trains run efficiently and in a coordinated manner.

Station description

The station in the model is fully daylit, with no obstruction above the platforms. There are eight wide platforms and 16 tracks, down from 11 platforms and 21 tracks today. The station box is bounded by 7th Avenue, 31st Street, 8th Avenue, and 33rd Street, as today; also as today, the central platforms continue well to the west of 8th Avenue, using the existing Moynihan Train Hall. No expansion of the footprint is required. The existing track 1 (the southernmost) becomes the new track 1A and the existing track 21 becomes the new track 8B.

The removal of three platforms and five tracks and some additional track-level work combine to make the remaining platforms 11.5 meters wide each, compared with a range of 9-10 meters at some comparable high-throughput stations, such as Tokyo.

With wide platforms, the platforms themselves can be part of the station. A persistent difference between American and European train stations is that at American stations, even beloved ones like Grand Central, the station is near where the tracks are, whereas in Europe, the station is where the tracks are. Grand Central has a majestic waiting hall, but the tracks and platforms themselves are in cramped, dank areas with low ceilings and poor lighting. The 3D model, in contrast, integrated the tracks into the station structure: the model includes concessions below most escalator and stair banks, which could offer retail, fast food, or coffee. Ticketing machines can be placed throughout the complex, on the platforms as well as at places along the access corridors that are not needed for rush hour pedestrian circulation. This, more than anything, explains the minimalistic design, with no concourses: concourses are not required when there is direct access between the street and the platforms.

For circulation, there are two walkways, labeled East and West Walkways; these may be thought of as 7⅓th and 7⅔th Avenues, respectively. West End Corridor is kept, as is the circulation space under 33rd Street connecting West End Corridor and points east, currently part of the station concourse. A new north-south corridor called East End Corridor appears between the station and 7th Avenue, with access to the 1/2/3 trains.

What about Madison Square Garden?

Currently, Penn Station is effectively in the basement of Madison Square Garden (MSG) and Two Penn Plaza. Both buildings need to come down to build this vision.

MSG has come under attack recently for competing for space with the train station; going back to the early 2010s, plans for rebuilding Penn Station to have direct sunlight have assumed that MSG should move somewhere else, and this month, City Council voted to extend MSG’s permit by only five years and not the expected 10, in effect creating a five-year clock for a plan to daylight Penn Station. There have been recent plans to move MSG, such as the Vishaan Chakrabarti vision for Penn Station; the 3D model could be viewed as the rail engineering answer to that architecture-centric vision.

Two Penn Plaza is a 150,000 m^2 skyscraper, in a city where developers can build a replacement for $900 million in 2018 prices.

The complete removal of both buildings makes work on Penn Station vastly simpler. The station is replete with columns, obstructing sight lines, taking up space between tracks, and constraining all changes. The 3D model’s blueprint takes care to respect column placement west of 8th Avenue, where the columns are sparser and it’s possible to design tracks around them, but it is not possible to do so between 7th and 8th Avenues. Conversely, with the columns removed, it is not hard to daylight the station.

Station operations

The operating model at this station is based on consistency and simplicity. Every train has a consistent platform to use. Thus, passengers would be able to know their track number months in advance, just as in Japan and much of Europe, train reservations already include the track number at the station. The scramble passengers face at Penn Station today, waiting to see their train’s track number posted minutes in advance and then rushing to the platform, would be eliminated.

Each approach track thus splits into two tracks flanking the same platform. This is the same design used at Stuttgart 21 and Berlin Hauptbahnhof: if a last-minute change in track assignment is needed, it can be guaranteed to face the same platform, limiting passenger confusion. At each platform, numbered south to north as today, the A track is to the south of the B track, but the trains on the two tracks would be serving the same line and coming from and going to the same approach track. This way, a train can enter the A track at a station while the previous train is still departing the B track, which provides higher capacity.

The labels on the signage are by destination:

- Platform 1: eastbound trains from the HTP, eventually going to a through-tunnel to Grand Central

- Platform 2: westbound trains to the HTP, connecting from Grand Central

- Platform 3: eastbound trains from the preexisting North River Tunnels (NRT) to the existing East River Tunnels (ERT) under 32nd Street

- Platform 4: eastbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 5: westbound intercity trains using the NRT and ERT under 32nd Street

- Platform 6: westbound trains from the ERT under 32nd Street to the NRT

- Platform 7: eastbound trains to the ERT under 33rd Street and the LIRR, eventually connecting to a through-tunnel from the Hudson Line

- Platform 8: westbound trains from LIRR via the ERT under 33rd Street, eventually going to a through-tunnel to the Hudson Line

Signage labels except for the intercity platforms 4 and 5 state the name of the commuter railway that the trains would go to. Thus, a train from Trenton to Stamford running via the Northeast Corridor and the under-construction Penn Station Access line would use platform 3, and is labeled as Metro-North, as it goes toward Metro-North territory; the same train going back, using platform 6, is labeled as New Jersey Transit, as it goes toward New Jersey.

Such through-running is obligatory for efficient station operations. There are many good reasons to run through, which are described in detail in a forthcoming document by the Effective Transit Alliance. But for one point about efficiency, it takes a train a minimum of 10 minutes to turn at a train station and change direction in the United States, and this is after much optimization (Penn Station’s current users believe they need 18-22 minutes to turn). In contrast, a through-train can unload at even an extremely busy station like Penn in not much more than a minute; the narrow platforms of today’s station could clear a full rush hour train in emergency conditions today in about 3-4 minutes, and the wide platforms of the 3D model could do so in about 1.5 minutes in emergencies and less in regular operations.

Supporting infrastructure assumptions

The assumption for the model is that the HTP is a done deal; it was recently federally funded, in a way that is said to be difficult to repeal in the future in the event of a change in government. The HTP tunnel is slated to open in 2035; the current timetable is that full operations can only begin in 2038 after a three-year closure of NRT infrastructure for long-term repairs, but in fact those repairs can be done in weekend windows—indeed, present-day rail timetables through the NRT assume that one track is out for a 55-hour period each weekend, but investigative reporting has shown that Amtrak takes advantage of this outage only once every three months. If repairs are done every weekend, then it will be possible to refurbish the tunnels by 2035, for full four-track operations in 12 years.

The HTP approach to Penn Station assumes that trains from the tunnel would veer south, eventually to tracks to be excavated out of Block 780 for $13 billion. However, nothing in the current design of the tunnel forces tracks to veer so far south to Penn Expansion. There is room, respecting the support columns west of 8th Avenue, to connect the HTP approach to the new platforms 1 and 2, or for that matter to present-day tracks 1-5.

It is also assumed that Penn Station Access (PSA) is completed; the project’s current timeline is that it will open in 2026, offering Metro-North service from the New Haven Line to Penn Station. As soon as PSA opens, trains should run through to New Jersey, for the higher efficiency mentioned above.

The additional pieces of major infrastructure required for this vision are a tunnel from Penn Station to Grand Central, and an Empire Connection realignment.

The Penn Station-Grand Central connection (from platforms 1 and 2) has been discussed for at least 20 years, but not acted upon, since it would force coordination between New Jersey Transit and Metro-North. Such a connection would offer riders at both systems the choice between either Manhattan station—and the choice would be on the same train, whereas on the LIRR, the same choice offered by East Side Access cuts the frequency to each terminal in half, which has angered Long Island commuters.

Overall, it would be a tunnel of about 2 km without stations. It would require some mining under the corner of Penn 11, the building east of 7th Avenue between 31st and 32nd Street, but only to the same extent that was already done in the 1900s to build the ERT under 32nd Street. Subsequently, the tunnel would nimbly weave between older tunnels, using an aggressive 4% grade with modern electric trainsets (the subway even climbs 5.4% out of a station at Manhattan Bridge, whereas this would descend 4% from a station). The cost should be on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions—the billions of dollars in per-km cost in New York today are driven by station construction rather than tunnels, and by poor project delivery methods that can be changed to better ones.

The Empire Connection realignment is a shorter tunnel, but in a more constrained environment. Today, Amtrak trains connect between Penn Station and Upstate New York via the existing connection, going in tunnel under Riverside Park until it joins the tracks of the current Hudson Line in Spuyten Duyvil. Plans for electrifying the connection and using it for commuter rail exist but are not yet funded; these should be reactivated, since otherwise there’s nowhere for trains from the 33rd Street ERT to run through to the west.

It is necessary to realign the last few hundred meters of the Empire Connection. The current alignment is single-track and connects to more southerly parts of the station, rather than to the optimal location at the northern end. This is a short tunnel (perhaps 500 meters) without stations, but the need to go under an active railyard complicates construction. That said, this too should cost on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions.

Finally, platforms 3-6 all feed the same approach tracks on both sides, but in principle they could be separated into two. There are occasional long-term high-cost plans to fully separate out intercity rail tracks from commuter tracks even in New York, with dedicated tunnels all the way. The model does not assume that such plans are actualized, but if they are, then there is room to connect the new high-speed rail approach tunnel to platforms 4 and 5 at both ends.

Overall, the model gives the station just 20 turnouts, down from hundreds today. This is a more radical version of the redesign of Utrecht Station in the 2010s, which removed pass-through tracks, simplified the design, and reduced the number of turnouts from 200 to 70, in order to make the system more reliable; turnouts are failure-prone, and should be installed only when needed based on current or anticipated train movements.

Pedestrian circulation

The station in the model has very high pedestrian throughput. The maximum capacities are 100 passengers/minute on a wide escalator, 49 per minute per meter of staircase width, and 82 per minute per meter of walkway width. A full 12-car commuter train has about 1,800 passengers; the vertical access points—a minimum of seven up escalators, five 2.7 meter wide staircases, and three elevators per platform—can clear these in about 80 seconds. In the imperfect conditions of rush hour service or emergency evacuation, this is doable in about 90 seconds. A 16-car intercity train has fewer passengers, since all passengers are required to have a seat, and thus they can evacuate even faster in emergency conditions.

Not only is the throughput high but also the latency is low. At the current Penn Station, it can take six minutes just to get between a vertical access point and an exit, if the passenger gets off at the wrong part of the platform. In contrast, with the modeled station, the wide platforms make it easier for passengers to choose the right exit, and connect to a street corner or subway entrance within a maximum of about three minutes for able-bodied adults.

This has implications for station design more generally. At the Transit Costs Project, we have repeatedly heard from American interviewees that subway stations have to have full-length mezzanines for the purposes of fire evacuation, based on NFPA 130. In fact, NFPA 130 requires evacuation in four minutes of throughput, and in six minutes when starting from the most remote point on the platform; at a train station where trains are expected to run every 2-2.5 minutes at rush hour and unload most of their passengers in regular service, it is dead letter.

Thus, elements of the platform design can be copied and pasted into subway expansion programs with little change. A subway station could have vertical circulation at both ends of the platform as portrayed at any of the combined staircase and escalator banks, with wider staircases if there’s no need for passengers to walk around them. No mezzanine is required, nor complex passageways: any train up to the size of the largest New York City Subway trains could satisfy the four-minute rule with a 10-meter island platform (albeit barely for 10-car lettered lines).

Technical limitations and architecture

The model is designed around interactivity and playability. This has forced us to make some artistic compromises, compared with what one sees in 3D architectural renderings that are not interactive. To run on an average home machine, the design has had to reduce its polygon count and limit the detail of renderings that are far from the camera position.

For the same reason, the level shows the exterior of Moynihan Station as an anchor, but not the other buildings across from the station at 31st Street, 33rd Street, or 7th Avenue.

In reality, both East and West Walkways would be more architecturally notable than as they are depicted in the level. Our depiction was inspired by walkways above convention centers and airport terminals, but in reality, if this vision is built, then the walkways should be able to support themselves without relying too much on the tracks. Designs with massive columns flanking each elevator are possible, but so are designs with arches, through-arches, or tied arches, the latter two options avoiding all structural dependence on the track level.

Some more architectural elements could be included in an actual design based on this model, which could not be easily modeled in an interactive environment. The platforms certainly must have shelter from the elements, which could be simple roofs over the uncovered parts of the platform, or large glass panels spanning from 31st to 33rd Street, or even a glass dome large enough to enclose the walkways.

Finally, some extra features could be added. For example, there could be more vertical circulation between 7th Avenue and East End Corridor (which is largely a subway access corridor) than just two elevators—there could be stairs and escalators as well. There is also a lot of dead space as the tracks taper from the main of the station to the access tunnels, which could be used for back office space, ticket offices, additional concessions, or even some east-west walkways functioning as 31.5th and 32.5th Streets.

Quick Note: Andy Byford and Through-Running

At an event run by ReThinkNYC, Andy Byford spoke for five minutes in support of through-running at Penn Station. They put out the press release, so I feel it’s fine to reprint it in full here with some comments.

The timing works well for what I’m involved in. The Transportation and Land Use program at Marron is about to release a playable 3D model of a reimagined Penn Station designed around through-running and around maximally efficient passenger egress, with above-ground structures like Madison Square Garden removed; I was hoping for the model to come out in June in time for the debate about whether to extend the Garden’s operating permit, but that debate seems to be going the right way regardless, and the Garden itself is open to moving, for a price. Then, the Effective Transit Alliance is about to release a long report explaining the issue of through-running, why it’s good for New York, and how to implement it.

The bulk of what we’re about to do on this side of the TLU program for the next year is figure out timetable coordination for regional and intercity rail, so showing how everything would fit together should take some time, but the question of feasibility has already been answered; the work is about how to optimize questions like “where do high-speed bypasses go?” or “which curves is it worthwhile to fix?” or “which junctions should be grade-separated?”.

First of all I am honored to be in a conversation with people that I regard as absolutely luminaries in the transit space, people like Prof. [Robert] Paaswell, people like Dr. [Vukan] Vuchic. These are luminaries to me in the field of, not only transport planning, but in the particular area we’re talking about today, namely through-running.

I was very encouraged to hear Assemblymember [Tony] Simone talk about the benefit of avoiding demolishing a beautiful part of New York City, which although I live in D.C. now, is a city that is so dear to my heart. I feel I’m an adopted New Yorker, I love that place and it would break my heart to see beautiful buildings torn down on Eighth and Seventh Aves. when they don’t need to be.

I should say at the get-go, that I’m not speaking on behalf of Amtrak. I’m speaking as a railway professional. I’ve worked in transit now for 34 years. But I just feel this is a golden opportunity — and the assembly member mentioned that — and one of the other speakers also mentioned the benefits of through-running and made reference to what happened in London. London learned that lesson. There are two effectively two cross London railroads.

There’s the Elizabeth Line, which I had the pleasure of opening with Her Majesty the Queen back in 2022, and that’s has been transformative in that where people used to have to jump on the Central Line, had to get off at Paddington and then go down to the Central Line and or down to Lancaster Gate and go through Central London to go to East London to Liverpool St. and then go out the other side, now they don’t have to.

The Central Line has been immediately relieved of pressure and you’ve got a state of the art, very high speed actually, through-service state of the art railway, under the wires. Beautiful stations, air conditioned, which at a stroke has been a game changer for London, connecting not only the key parts of Central London, but also Heathrow Airport, Paddington, Liverpool St., Canary Wharf and the City of London. It is a game changer. People in Frankfurt, people in Amsterdam, people in Paris and dare I say, New York, are probably gnashing their teeth because that was a game changer for London.

Well, I live in the States now, I’m going to be an American hopefully in a few years time and I want to do my bit for the States. So it seems to me that this is a golden opportunity for the U.S. and for New York City to have something similar to the Elizabeth Line, to have something that has that economic regenerative impact in New York.

And the other corridor of course, was Thameslink, that preceded Crossrail, but that’s the north/south corridor. There again, once upon a time you used to rock up in South London and have to get on the Tube you’ll be getting on the Vic Line or you’re getting on the Northern and have to go up to Euston or Kings Cross to go north.

Now, you don’t have to do that and what London has seen is the benefit of that cross-London traffic and that through-running because you’ve got not only the economic benefits of the City but the knock-on effect of north, south, east and west of businesses popping up, of housing being developed and of relief to the existing transport lines.

So I don’t know how this is going to pan out, but what I would say, Sam [Turvey]: is good for you for at least calling the question. This is a golden opportunity. It’s not just about building something that’s more aesthetically pleasing — important as though that is, Penn Station is kind of an embarrassment — but you can’t fix it by just putting in a few light boxes, by just heightening the ceilings, by just widening a few corridors.

If we’re going to do all of that, why not take the opportunity to fix the damn thing once and for all, which is, I’m going to say: get rid of the pillars, which means move MSG, but at the very least, do something with the track configuration to enable through-running.

So that’s it, that’s my pitch. I do stress that’s my personal opinion. I’m not speaking on behalf of Amtrak. I don’t know all the facts. If it was the case that someone asked me to have a look at this, I’ll be honored to do that, but I’m just speaking as a private person who cares about New York City, who cares about the States and who’s seen what good looks like along with people far smarter than me like Prof. Paaswell and Dr. Vuchic. So thank you so much.

Why Does TGV Ridership Overperform Models?

I’ve found some TGV ridership data with which I can check the model I use for high-speed rail ridership projection. The model is trained on Japanese data and has flaws in Japan too, but I’ve wanted to see how well it ports to Europe, where I don’t have as complete a dataset of ridership between pairs of metropolitan areas. Thankfully, I have just found a short Omnil report from 2015 about intercity rail ridership at the Parisian terminals, from which we can extract some information. The TGV overperforms the model substantially; this can be explained with fudge factors, but those fudge factors only work if we assume that the aspects of the TGV that seasoned rail advocates hate don’t matter much.

The model

As a reminder, the model posits that the annual ridership in millions between two metropolitan areas with populations and

in millions, of distance d kilometers, is,

The model is very accurate for ridership between Tokyo and other cities on Honshu; it overpredicts inter-island ridership, but becomes correct if we replace the Japanese air/rail modal splits with European ones, where taking the train over five hours is more normal than in Japan. I would expect that in isolation, European ridership should overperform it, because fares here are much lower, about 0.10-0.11€/kilometer compared with about $0.23/kilometer on the Shinkansen. French ridership significantly overperforms, beyond what the fares alone can explain, as we will see.

We will need to modify the model as written above for the French case anyway. TGV ridership relies on direct through-service from Paris to every city in France, including many that are not on the network of dedicated high-speed lines (called LGVs); trains serve those by diverting from the LGVs to classical lines, on which they travel more slowly. Therefore, while we can apply the model as above for connections that entirely use LGVs, like Paris-Lyon or Paris-Marseille, we need to consider the slower speeds for connections that use classical lines. For those, we assume that trains average 220-225 km/h; this is the rough average speed of the express Shinkansen trains as well as that of the TGVs to Lyon and Marseille. Thus, the model, at travel time t, is,

The floor of 500 km, or in this case a trip time of hours, is empirical in Japan. But then it is clear, from Italian data, that speeding up the trip has a roughly square-law effect on ridership, even within the limit – the growth in ridership on Bologna-Florence is consistent with an even higher elasticity of ridership with respect to average speed. The best way to reconcile these two observations is that in the presence of high-speed rail, the effect of distance cancels out the effect of better competition with the car up to about 500 km, but if the trains are slower, the car is more competitive and this is seen as a square law at all speeds. This is not too relevant to France, but is useful context for medium-distance, medium-speed lines in Germany.

TGV ridership

I have never been able to find city-to-city or station-to-station ridership figures in France. The Omnil report is no exception: it reports ridership at the Paris stations and breaks down where people are going by region of France in the geography of 2015, before the merger of some regions.

The total ridership at the Paris stations, including TGVs, low-speed intercity trains, and other regions’ regional trains (TERs) but not Paris-area regional trains (Transilien), is 443,000/day; of those, the TGVs comprise 239,000 and the slow trains 204,000. The four Parisian terminals with TGVs – Gare de Lyon, Gare du Nord, Gare Montparnasse, Gare de l’Est – have 92% of the TGV ridership in the region, while the other 8% are at suburban stations on bypasses around the city, like CDG Airport. Ridership is asymmetric: two-thirds of those 443,000 daily riders don’t live in Ile-de-France, which is what we should expect of a commuter-heavy ridership profile. Within Ile-de-France, 63% of passengers originate or are destined to Paris itself and another 21% for the Petite Couronne suburbs, showcasing destination centralization – Paris is only 17% of regional population and about 33% of regional employment, but 63% of those interregional and intercity trips go there and not to the suburbs.

There is also a breakdown of where passengers are connecting, by region of France or country. Picardie is increasingly an exurb of Paris, to the point that as France was debating the merger of regions in the early 2010s, one proposal was to detach its southernmost department, Oise, and attach it to Ile-de-France; 19% of the non-Francilien passengers originate there and 10% of Franciliens go there, for a ratio of nearly 4:1. More relevantly to high-speed rail, Rhône-Alpes is 9% of both non-Francilien and Francilien ridership, for a ratio of about 2:1, and a total of about 40,000/day, or around 13 million/year. PACA is 5% of non-Francilien and 7% of Francilien ridership, for a ratio of about 1.4:1 and a total of 25,000/day or around 8 million/year.

So we need to evaluate our model against an observed ridership of 13 million between Paris and Rhône-Alpes, and 8 million between Paris and PACA. Both sets of numbers involve multiple city pairs, with fairly long tails: France is a country of small metro areas, the median person living in a metro area of 330,000, whereas half of Japan lives in the metro areas of Tokyo (37 million), Osaka (18 million), and Nagoya (9 million).

French metro areas and the model

France recently changed its definition of metro areas. The old one, the aire urbaine, was similar in definition to the American metropolitan statistical area; the new one, the EU-wide functional area, generally spits out slightly larger numbers, though it still seems tighter than the Japanese definition. The functional area of Paris, comprising Ile-de-France, about half of Oise, and surrounding communes, has 13.2 million people. The new definition splits Nice and Cannes apart, which is good, since both have TGV service to France.

| Metro city | Population | Trip time | Prediction |

| Lyon | 2.29 | 1:58 | 4.586 |

| Grenoble | 0.72 | 3:01 | 0.999 |

| Saint-Etienne | 0.5 | 2:58 | 0.771 |

| Geneva (French part)* | 0.44 | 3:13 | 0.485 |

| Annecy | 0.3 | 3:45 | 0.321 |

| Chambéry | 0.26 | 2:52 | 0.49 |

| Valence | 0.26 | 2:12 | 0.805 |

| Bourg-en-Bresse | 0.14 | 1:50 | 0.49 |

| Marseille | 1.88 | 3:07 | 2.02 |

| Nice | 0.62 | 5:48 | 0.24 |

| Toulon | 0.58 | 4:02 | 0.47 |

| Cannes | 0.39 | 5:18 | 0.199 |

| Avignon | 0.34 | 2:40 | 0.701 |

The Rhône-Alpes metro regions combine to a predicted ridership of 8.95 million; actual ridership is higher by about 50%. The PACA metro regions combine to a prediction of 3.63 million; actual ridership is higher by a factor of maybe 2.2.

Note that the prediction is already based on some optimistic assumptions. The trip time is the best that can be sustained multiple times a day; the issue of frequency is ignored, so the effective trip time on connections from Paris to cities like Annecy with a train every three hours gets no malus, even though the Japanese city pairs that the model is trained on get multiple express trains per hour. This is relevant, because as we examine fudge factors below to rescue the model, we need to keep ignoring or at best minimizing the malus due to poor frequency and lack of trip spontaneity in the ticketing system.

Fudge factors explaining the overperformance

We need to explain why Rhône-Alpes overperforms by 50%, and PACA by more than 100%.

Fares

The average JR East Shinkansen fare revenue in 2020-1 was ¥23.8/passenger-km (source, PDF-p. 50), and has risen little in the last 10 years. The average TGV fare revenue in 2019 was 0.10€/passenger-km (source, pp. 16 and 20) and has likewise little changed in nominal terms. These differ by a factor of 1.6. The elasticity of high-speed ridership with respect to price varies widely by study; the Italian study linked above says -0.37, one Spanish study says -0.59, and Börjesson’s lit review says -0.59 for non-business trips and -0.72 for business trips. A value of -0.5 explains a factor of 1.27 overperformance by itself; a value of -0.6 explains a factor of 1.33.

In fact, Germany, charging similar average intercity rail fares to France, seems to overperform the Shinkansen model too. I have little data here, only line-wide Berlin-Hamburg and Berlin-Munich, both of which look like they overperform by about 20%. This can result from a 30% overperformance mitigated by the issue of lower speed: the modeled prediction is based on trip times, but when trips are shorter than about 2:15, the model stops seeing the impact of slowdowns – Berlin-Hamburg is 1:44 and Berlin-Leipzig is 1:13, where at Shinkansen or TGV speeds they’d be 1:17 and 0:45 respectively.

Metro area size

French metro area definitions, even with the new functional areas, are somewhat tighter than Japanese ones. The functional area of Berlin has 5 million people, but reckoned the Japanese way (1.5% of the age 15+ population commuting to the central city), practically all of Brandenburg would count, a population of 5.7 million in total. This is likely more significant in PACA, where the above-listed metro area are 80% of the total population, than in Rhône-Alpes, where they are 90%. It’s possible even Paris is a bit bigger than 13.2 million – but only a bit, since Ile-de-France and Oise together only have 13.1 million. This factor can scrounge some extra ridership, but probably no more than 10%, maybe a bit more in PACA.

Leisure travel

Provence is renowned for its tourism, which generates extra trips out of Paris beyond what we should expect from population alone. This should disproportionately affect Nice and Cannes; for what it’s worth, I’m seeing seven weekday trains from those cities and Toulon to Paris, I believe all skipping Marseille, and 14 trains from Marseille; if we take ridership as proportional to the offer, this does show some Riviera overperformance relative to Marseille, though not by much.

Of course, the majority of Paris-PACA ridership comprises Provençals, not Franciliens. But perhaps the 1.4:1 ratio of Provençals to Franciliens is atypically low, and the 2:1 ratio in Rhône-Alpes is more normal of capital-province relations; I have no Japanese numbers on this, and would overall expect to see similar asymmetries in both countries, given their similar level of economic capital-centricity. If 2:1 is typical, then the extra leisure ridership from the capital to make it 1.4:1 adds a total of 14%, which is far less than PACA’s overperformance relative to Rhône-Alpes.

Metro area coverage

The PACA cities have multiple stops. The population distribution in the Riviera is linear, and multiple cities with extensive leisure (like Saint-Tropez) are served by the TGV. Marseille likwise has a second stop at Aix-en-Provence, close by car to its northern suburbs to the point that I’ve heard it called Marseille-bis. If we split metro Marseille’s population 2:1 between Marseille and Aix, then the 0.8 exponent in the model produces a 14% increase in ridership. 14% and another 14% from leisure combine to 31%, which explains the majority of the PACA overperformance relative to Rhône-Alpes.

Competition with air in small cities

The TGV competes with cars and planes; domestic buses are almost a non-factor, and were entirely a non-factor in 2015 (they’re called Macron buses because it was Macron, as minister of economics in 2014-6, who passed the reform that allowed them). In Rhône-Alpes, competition is entirely with the car: Lyon is just close enough to Paris that air travel can’t compete; in PACA, competition is mostly with the plane, especially beyond Marseille.

The population distribution in both Rhône-Alpes and PACA may favor the train. The issue is that the secondary cities of Rhône-Alpes are around three hours from Paris, at which point the train is strongly favored but planes normally still exist, as in Marseille. However, those cities are scattered all over the region, and so there is no single airport that could serve them, except Lyon – and if the choice is to take the train for three hour or to drive an hour to Lyon-Saint-Exupéry, then the train can just demolish air competition.

In PACA, the same is true for the secondary cities. Nice has a strong airport with many flights to Paris, buoyed by the leisure market, but Toulon and Avignon don’t; on the eve of corona, Toulon-Hyères had 500,000 passengers a year, most not bound for Paris.

I believe this effect on air-rail competition is more significant in Rhône-Alpes than PACA. However, air competition is overall more significant in PACA than in Rhône-Alpes, and thus it likely effects a similar boost to TGV ridership in both regions, or perhaps is more significant in PACA, explaining the remainder of its overperformance.

Some conclusions

I don’t think the TGV’s overperformance of the model invalidates the model. Most of the overperformance in Rhône-Alpes can be explained by fares alone, and I think the rest can be explained by the modal split versus air being more favorable than in Japan given the small size of Annecy, Saint-Etienne, and so on. Most of the overperformance in PACA relative to Rhône-Alpes can then be explained by leisure travel and the good metro area coverage of the TGV thanks to Aix and the linear population distribution of the Riviera. However, these fudge factors have implications for rail planning in France, Europe, and beyond.

Connections to smaller cities

The modeled prediction is that Lyon and Marseille comprise little more than half the ridership to Paris from their respective regions. Moreover, the overperformance of TGV riderhip relative to the hinkanssen model likely comes disproportionately from smaller cities, due to their lack of good air connections. This underscores the importance of good service not just to million-plus metro areas but also to the tail of metro areas of half a million, give or take. Those metro areas are less important in rich Asia or the US, but are important throughout Europe.

This service to smaller cities can take the characteritic of TGV-style direct connections to Paris on classical lines. In Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria, and increasingly Germany, service to smaller cities is provided through timed connections at carefully-chosen nodes; the Swiss network particularly excels at this. But the French system’s ridership is such that it not obviously inferior, and is unlikely to be inferior to the German system at all. Thus, a country like Poland or Britain can safely choose between the French and German system, or even mix them.

The issue of frequency

The low frequency of TGV services to smaller cities – trains run every two to three hours, often timed to just miss regional trains – should be visible as a serious malus to ridership. But it isn’t. Perhaps it exists and countermands the effect of lack of air competition to cities the size and distance class of Grenoble – but Grenoble is not Nice, and air competition there even under more favorable scenarios to planes would be second-order.

At the same time, there are markets where the TGV is visibly much weaker. The TGV’s modal split between provincial regions is not good. Because trains from Paris to Marseille don’t stop at Lyon, and trains from Paris to Lyon don’t continue onward to Marseille, the Lyon-Marseille city pair cannot piggyback on strong connections to the capital the way same-side pairs of provincial Japanese cities can. The dedicated Marseille-Lyon trains have an inexplicable six-hour gap, with frequent service on both sides of it, and the Toulon-Lyon trains are even worse. The modal split is evidently weaker – in 2009, nearly everyone drove betwen Lyon and Toulon (the 2023 number in the link are speculation for what if an LGV is built to Nice), even over a rail-friendly distance of about 390 km, averaging around 130-150 km/h.

So while the system that centers direct trains to Paris is not suspect, the lack of frequency on shorter connections between secondary cities is. This could be resolved with buying rolling stock that makes boarding and alighting faster, with two door pairs per car rather than just one; TGV connections not including Paris run local, and since the trains are not optimized for many stops, those connections have low average speed, which in turn discourages SNCF from providing more frequent local connections.

Liberalization

The EU is increasingly forcing national railways to allow on-rail competition. This is an idea imported from the UK, where John Major’s privatization of British Rail split up operations and infratructure, the latter eventually renationlized; in Japan, privatization broke up JNR into regional JR companies, each responsible for both infrastructure and operations as in the pre-nationalization era of rail, and in the US, the breakup of Conrail likewise restored the pre-nationalization status quo. SNCF resists the mandate for competition in increaingly spiteful ways: it makes up excuses why RENFE can’t operate on its network, and where it does operate, it won’t even let its crew use break rooms at French stations. Eurocrats, even more progressive ones, treat SNCF as public enemy #1.

And SNCF’s anti-competitive monopoly on domestic rail travel generates high rail ridership. Italy and Spain have both seen sharp increases in ridership from the competition mandate. But Madrid-Barcelona, offering worse frequency and a more broken market than the domstic TGVs (domestic TGVs are split just between lower-price OuiGo and higher-price InOui brands; Spanish high-speed trains have more classes of train on thinner markets), don’t perform nearly so well. Madrid-Barcelona riderhip in 2019 was 4.4 million; the modeled prediction is 4.1 million for this city pair alone, and 6 million including intermediate trip to Zaragoza. Riderhip ha risen since the introduction of competition in 2020, and media coverage has been laudatory, and at times depreating of France for failing to liberalize – but the 50% growth in ridership cited in most articles still leave the line barely overperforming the high-fare Shinkansen and strongly unerperforming the TGV.

European media should be less credulous of promises of private-sector efficieny and recognize that the TGV’s model of public-sector monopoly, with integration between infraatructure and service (even if this means shoving direct trains to Paris on trunk line rather than building a Swiss integrated timed transfer system), produces better outcomes than competition. Germany has the same model too and, relative to how slow its trains are, has good outcomes too; Switzerland, the undisputed leader of European rail ridership, resists privatization entirely. Private competition did not invent high-speed rail, and where it has been introduced it has so far failed to produce outcomes on a par with what the TGV has with entirely public operations.

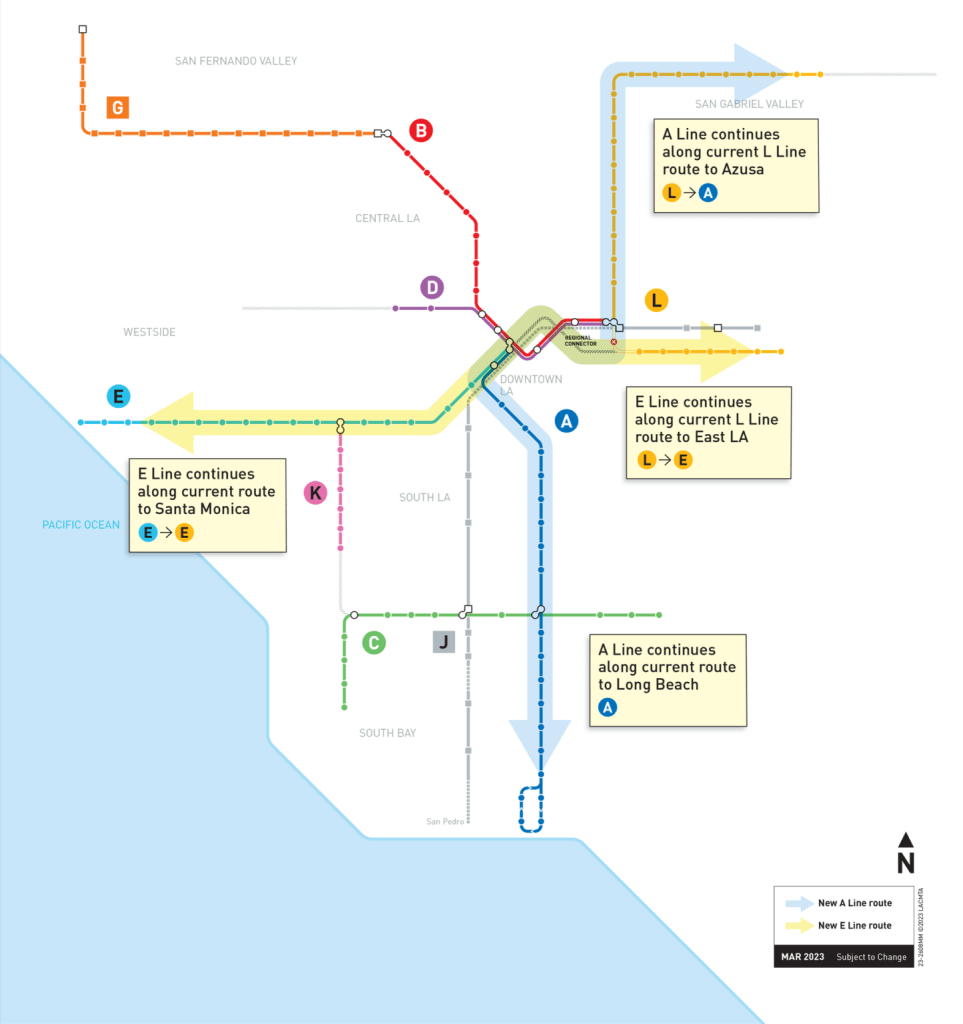

The Regional Connector and Network Coherence

The Regional Connector just opened in Los Angeles. This is a short, expensive tunnel permitting through-running for the city’s main light rail lines, linking the A Line (formerly Blue) with the half of L (formerly Gold) to Pasadena and Azusa and the E (formerly Expo) with the half of the L to East Los Angeles. It’s a welcome development and I only regret that this line cost, in 2022 dollars, $660 million per km. The broader question about the line, though, is that of line pairing and network coherence.

Network coherence is a nebulous concept. I can best define it as “it looks reasonable on a map,” but then the number of railfan crayons that violate coherence principles is so large that it has to be defined more precisely. Usually I talk about it in two concrete ways: a rapid transit network should avoid reverse-branching and tangential lines.

But there are some more concerns, which are less obvious than those two, and also appropriate to violate in some cases. My previous post on New York alludes to the principle of consistency of local and express trains, which is good to aspire to but may conflict with other priorities. In fact, the current pattern in Los Angeles is coherent: trains go north-south on the new A Line or east-west on the new E Line; the question, posed to me by a supporter (thank you!), is whether it should be. I think this is right, but it’s not obvious (in fact it wasn’t to the reader who posed this question).

The issue is that simple coherence – lines from the south should go north and not east, express trains on one side should go through city center and then be express on the other side, and so on – is a good starting point. But there may be other concerns at play. When SEPTA opened the Center City Commuter Connection in the 1980s, it relabeled its commuter rail lines R1 through R8, skipping R4, pairing each branch on the former Pennsylvania Railroad side with one on the Reading side; the resulting map, for which this was an early plan, was not at all coherent and featured self-intersecting lines, but it matched the lines based on expected ridership and railyard locations.

The New York City Subway, likewise, has some pairings that only make sense in light of railyards. The R train shares local tracks in Manhattan with the W train, but in Queens it goes to the Queens Boulevard Line whereas the N shares tracks with the W to Astoria, because the Queens Boulevard Line has a yard at the end and the Astoria Line does not, and the N has a yard at the Brooklyn end of Coney Island whereas the R does not at Bay Ridge; the R is the longest all-local line in the system and railfans periodically propose to switch it with the N in Queens, but the railyard issue makes it problematic in the current situation.

Matching branches by ridership, though, runs into the problem of inconsistent headways on the trunk. A light rail line running every eight minutes can share a tunnel with another light rail line running every eight, but if one of them runs every six minutes, they will run into each other on the shared section. This problem is magnified if both the shared section and the branches are long, which is usually the case in New York; thankfully, in Los Angeles the shared section is short enough that optimizing on it is less important. At most, it’s possibly to match branches by ridership if the train lengths can be made different.

The final concern that may lead to violations of coherence is origin-and-destination ridership patterns; I think this is what my reader had in mind when querying it. Such patterns may be ethnic – there’s a notable bump in ridership between Anacostia and Columbia Heights on the Washington Metro, and it’s likely that such patterns also exist elsewhere in cities that just don’t track O&D pairings, like New York with its internal Chinatown buses. They may even be classed, in the sense that wealthier Americans are likelier to be working in city center, but on the whole, rich and poor people are mostly traveling to the same places. They may be sporadic – a university may be driving ridership enough that there could be connections to either places students want to go or (for commuter universities like UBC) where students live.

O&D pairings like this should, as a rule, never drive infrastructure decisions. These patterns are too fleeting – for example, Columbia Heights’ gentrification is so rapid that the links with Anacostia are unlikely to last for more than a generation. However, it’s not always bad to look at them when making decisions on service for a given infrastructure network.

The issue, though, is that there’s no real compulsion to connect Long Beach with East Los Angeles or Santa Monica with Pasadena and Azusa. The commute data doesn’t suggest special links (which, to be fair, it also doesn’t in Washington). I am not aware of any other big pattern that would create such ridership. So it’s something that I think Metro should have looked at (and probably did), but ultimately made the right decision on.

How Fast is Necessary?

Swiss intercity rail planning follows the maxim “run as fast as necessary, not as fast as possible.” This is usually uttered in opposition to high-speed rail in the sense of the French TGV network. But what does this slogan really mean? And how does it inform good planning?

The issue of timed connections

The origin of the Swiss planning system is in the 1970s and 80s, as it was refining intercity rail, taking what West Germany was doing with its InterCity brand and going further. Two key elements were present from the start: timed connections, and regular clockface timetables (initially every two hours in West Germany). The clockface timetabling facilitated the timed connections, since it’s easier to figure out how to schedule a timed transfer at (say) Frankfurt if the same train moves happen at the same intervals.

With these elements in place, Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) set up a schedule in which trains would be timed to arrive in Zurich all at the same time, currently just before the hour, and depart all at the same time, currently on or just after the hour.

The issue is what to do at stations other than Zurich. Optimizing for timed connections at Zurich means compromising on the question of what to do at other cities. If trains arrive and depart Zurich roughly on the hour, then the terminal at the other end may have ugly arrival and departure times – for example, a 1:40 trip time, with Zurich arrival :56 and departure :04, would mean that the other end has an arrival time of :44 and a departure time of :16. If it’s an hourly train, it means it’s not possible to time connections there – an arriving bus or regional train would have a transfer time of perhaps 20 minutes, which in a country the size of Switzerland is a large share of the overall trip.

And then there is the looming issue of intercity connections. Zurich is located fairly centrally in Switzerland, but there are some key connections that don’t go anywhere near it, led by Bern-Basel via Olten. Bern’s central location makes it a great node for timed connections as well. However, the Zurich-Bern trips took 1:09, making it impossible to have timed everywhere-to-everywhere connections in both cities.

Speeding up trains to make connections

In the 1980s, the Zurich-Bern trips took 1:09, so connections could only be timed in Zurich, not Bern. At the time, there were plans for a French-style high-speed rail network connecting Zurich, Bern, and Geneva, but those plans were canceled due to high costs relative to Switzerland’s size.

Instead of running as fast as possible, enough to connect Zurich and Geneva in perhaps 1:30, trains would run as fast as necessary, just enough to make connections. The centerpiece of this plan, dubbed Rail 2000, was to speed up Olten-Bern by just enough to shorten Zurich-Bern and Basel-Bern to 0:56 and 0:55 respectively. This way, trains could arrive in all three cities just before the hour and depart just after, facilitating more timed connections.

This system was a resounding success. Swiss rail ridership has been sharply rising in the last 20 years, from an already fairly high level; by all metrics I am aware of, such as modal split, ridership per capita, and passenger-km per capita, it is Europe’s strongest rail network. More speedups are planned, all aiming to add more points where trains can be timed to connect, called knots, till the network looks like this:

The shape of Switzerland

The notion of running trains as fast as necessary is in one sense a global principle. But its surface manifestation of a system designed as an alternative to high-speed rail is a product of Swiss geography; in Japan, the current speed of the Shinkansen is also as fast as necessary. Switzerland’s current knot diagram has to be understood in the context of the following geographical features:

- Switzerland is small enough that the strongest trunk corridors, like Zurich-Bern, can support just a train every half hour.

- Switzerland is also physically small enough that the Zurich-Bern-Basel triangle has legs of about 110 km, which an upgraded rail system can connect in an hour minus transfer time, and which it is very hard to speed up to 30 minutes minus transfer time.

- Switzerland is two-dimensional: there is no central trunk through which all service must pass – the diagram above depicts Zurich-Olten as a key link, but Luzern, though not yet a knot, connects separately to both Zurich and Bern.

- Swiss train stations have a surplus of tracks, while still functioning as central stations, without the separation into different stations for different directions that Paris and London have.

Switzerland is not unique in having these features. The Netherlands is the same: it’s a small two-dimensional country with demand for many connections to be timed. The Netherlands built a 300 km/h high-speed rail line between Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and the border with Belgium toward Antwerp, Brussels, and Paris, but this line is not important to its intercity rail planning, which instead lives on Swiss-style knots.

However, not even all small countries are like Switzerland and the Netherlands. Israel is one- rather than two-dimensional: all trains pass through Tel Aviv and the Ayalon Railway, and there is no real need for timed connections, as the most important city pair not involving Tel Aviv, Haifa-Jerusalem, passes through Tel Aviv, with through-service to begin as soon as electrification is completed. Taiwan is so linear that a single high-speed rail line connects all of its cities, with higher ridership per capita than in any other country I have data for except maybe Japan; even before high-speed rail, the shape of its mainline network was a single line on the west coast connecting the cities and another on the east coast connecting smaller settlements.

And then in large countries, running as fast as necessary requires choosing a speed. Germany is two-dimensional like Switzerland, but has a string of city pairs 90-100 km apart – Hanover-Bielefeld-Dortmund, or Mannheim-Stuttgart, or the Fulda-Frankfurt-Würzburg triangle, or Würzburg-Nuremberg – for which running a fast as necessary entails a choice between connections in 60, 45, or 30 minutes. Longer-distance city pairs, like Nuremberg-Munich, Berlin-Leipzig, and the Hamburg-Hanover-Bremen triangle, are even less constrained.

Capacity

The Swiss network is based on the idea that near major stations like Zurich, trains should arrive and depart on pulses every 30 minutes. This way, the Olten-Bern line runs eight intercity trains per hour, but they are not equally spaced: they are timetabled in two platoons over a period of seven minutes each, with the off time used for regional trains not participating in the knot system.

Even in the Netherlands, this isn’t quite tenable. Amsterdam-Eindhoven trains come at regular 10-minute interval, each third train requiring a connection at Utrecht and the other two trains in three running directly. In Israel, Tel Aviv-Haifa trains run at 30-minute intervals midday, but for two four-hour peak periods each day this is boosted to four trains per hour – and this is even before electrification has been completed.

The situation in Germany deserves especial mention. Germany is investing in it intercity rail network in a way that sometimes tries to be Switzerland except bigger (such as the Deutschlandtakt and other measures supported by technical advocates) and sometimes tries to build high-speed rail lines and through-stations like Stuttgart 21. The technical advocates dislike Stuttgart 21 and argue that it’s un-Swiss to timetable intercity trains throughout the hour rather than in two pulses with inactivity between them. But Germany has large enough cities that it can’t afford to keep intercity lines out for so much time. Already, with mediocre speeds, the Deutschlandtakt plan for 2030 prescribes 4.5 trains an hour between Frankfurt and Mannheim and between Frankfurt and Cologne. As more high-speed lines come online, demand will grow; Deutsche Bahn projects to double ridership between 2019 and the 2030s, which will force the busiest links to operate a train every five to 10 minutes.

Is Swiss planning useful outside Switzerland and the Netherlands?

Unambiguously, yes. However, it would look different.

The best place to see how different it should be is, naturally, the Northeastern United States, my area of research. None of the features that made Rail 2000 work is present there: the region is large and has huge cities, is one- rather than two-dimensional, and has capacity-constrained stations forcing round-the-hour use of every approach track.

What this means is that there is little optimization from running slower than as fast as possible on the Northeast Corridor trunk line. However, running a fast as necessary remains a solid planning maxim on all the branches that connect to it, with their own timed connections to one another and to local buses in secondary cities like Worcester and Springfield. Most trains between Boston and Washington should run as express as practical based on station track speeds, and the local trains may plausibly only run every half hour, making them ideal for a system of timed half-hourly connections.

Quick Note: Heavy Touch and Control

There’s a distinction between light- and heavy-touch forms of management and control. Light-touch systems try to stay out of the details as far as they can; heavy-touch systems do the opposite. American business culture considers light touch to be superior, and I think this is especially prominent in the public sector, which has some ready-made examples of how the light touch approach works better – for example, in the military, it’s called mission command and is repeatedly shown to work better than more centralized command-and-control. Unfortunately, the same does not work for rail infrastructure. Why?

Heavy touch in infrastructure

In practice, a heavy-touch system in infrastructure construction, for example the way Germany, France, and Southern Europe work, has the following features:

- The state agency maintains control of designs, and even when it outsources something to consultants, it owns the product and may tweak it or assume that future contractors will tweak it. There is little privatization of planning.

- There is reluctance to devolve decisions to local governments; if SNCF or RENFE lets a regional government get involved in a rail plan, it’s because it’s an unprofitable regional line and the national railroad would rather not know it exists, and even DB happily unloads these same unprofitable regional lines on Land governments while focusing on intercity rail.

- Regulators are technical and make specific decisions.

This is not the only way to organize things, but it’s the only way that works. The Nordic countries have been moving away from this system in the last generation, influenced by British governing ideology; the sources I reference in the Stockholm case study repeatedly treat privatization as self-evidently good and exhort Nordic agencies to be more like the UK and less like Germany and Switzerland, and meanwhile, in the last 20 years Nordic costs have exploded while German ones have been fairly stable.

I’ve talked about the issue of privatization of the state to consultants many times, most recently a month ago. This post is about something different: it’s about how regulators work, an issue on which Sweden appears little different from Germany to me, and profoundly different from the United States and its can’t-do government.

American light touch elements

To understand how American regulations work, we need to look at the regulators and grant funders, that is, the Federal Transit Administration and Federal Railroad Administration, henceforth abbreviated FTA and FRA. How do they work?

- The chief regulators are never especially technical. The most sought after background, equivalent to a French grande école degree, is as far as I can tell a law degree from Yale. Engineers and planners always have to have a non-technical generalist watching over their shoulder, and this is the most prominent for the most politically sensitive projects.

- FTA/FRA reviewers are in some cases not even allowed to probe into the funding package they are to decide on. One of the biggest projects relevant to what we’ve studied at the Transit Costs Project and what I’ve written on this blog has a multi-billion dollar package, one that will almost certainly be only partially funded due to competing priorities, but the regulators are not allowed to see any itemized breakdown to see what partial funding would even do. Nor are regulators allowed to say which priorities to build first if there’s only partial funding.

- The higher regulators themselves believe that light-touch approaches are better and are reluctant to engage in any direct management – if they’d like to be more involved but are prohibited from doing so by the law or by constitutional interpretations, they have not said so.

- There is little churn between operations and regulations – in fact, this separation is treated as sacrosanct, even as in all other aspects the governing ideology calls for breaking down silos (and thereby disempowering specialists in favor of generalists). The contrast here is with Sweden, where state planners who worked on Citybanan, a state project, have since moved on to work for Stockholm County on the county-led Nya Tunnelbanan.

None of this works. The people who make the big decisions on funding in this system do not have the ability to make professional judgments, only political ones, and agencies know this and don’t bother with technical soundness.

Heavy touch and expertise

The connection between heavy touch and expertise is, you can’t manage things directly if you don’t have a lot of subject matter knowledge. In this sense, light touch may not necessarily be by itself bad, but rather, like design-build project delivery, it is in practice used to mask incompetence at the top level. The non-technical boss, who is in all but name a political commissar, can make vague proclamations, not get into details, and not feel like they’re out of their league and must defer to the engineer in the room.

Doing Projects Right and Doing the Right Project

I’d like to develop a distinction between two modes of success or failure in infrastructure projects, which I’ve mentioned in brief in past post. An infrastructure project may be done right or wrong – that is, it could be built at a reasonable lifecycle cost and offer high quality of service or it could fail to do this, typically through very high upfront construction costs with no future benefit. But it could also be the right project to build or the wrong one – that is it could be the right priority for the region that builds it based on expected usage and future development or it could be a low priority, typically due to politicization of engineering and planning. Those are distinct judgments, and I’m not even sure they are strongly correlated.

The right project, done wrong

I’ve mentioned in a few past posts as well as videos that New York is for the most part building the right projects right now. Based on any reasonable cost per rider calculation, the highest priorities in the region excluding mainline rail are Second Avenue Subway phases 1 and 2, an extension of phase 2 under 125th Street, subway extensions under Nostrand and Utica Avenues, an orbital line following the Bay Ridge Branch toward Jackson Heights and Yankee Stadium, and a subway extension to LaGuardia Airport. Phase 1 has been built, and the current priorities are phase 2 and the orbital line under the moniker IBX, the latter giving the governor’s personal imprimatur to this important project. The only lower-priority extension built ahead of these is the 7 extension to Hudson Yards, which is a small fraction of the good projects by total cost.

In mainline rail, on the New Jersey side, the biggest priority is the Gateway tunnel and this is indeed what the state and Port Authority are most invested in. Even on the New York side, mainline rail is invested in in roughly the right priority order, especially if one fixes the assumption of bad present-day operations; the only real problem is that due to politics from the late 1990s, the MTA overinvested in New York-side mainline rail (that is, East Side Access) to secure suburban Republican support for Second Avenue Subway phase 1.

The problem for New York is that every single project it touches is executed in almost the worst way possible. It can’t build, and to an extent it doesn’t even want to build. The $50 billion in New York-side capital investment every five years are a large multiple of what peer cities spend, and what this buys is a few kilometers of subway every decade, escalating maintenance costs, and a vague promise to not quite finish making the subway accessible in the 2050s. But the little it does build is, for the most part, the right project.

New York is not the only city in this situation. The prioritization in Toronto seems fine to me, including the Downtown Relief Line rebranded as the Ontario Line, electrification and general modernization of commuter rail as part of the RER project, and rail on Eglinton. London, likewise, seems to be building projects in the right priority order, but it lost its ability to build in the 1980s and 90s so that its urban rail growth rate is roughly one new line per monarch and its step-free access program is proceeding at a slower pace than that of any peer except New York (which can’t build anything) and Paris (which can and does but doesn’t believe in accessibility).

Wrong projects

In contrast with the example of New York or Toronto, there are places where the prioritization is completely out of whack. The best example I can give of is Los Angeles. Like New York and other English-speaking cities, Los Angeles can’t build; unlike New York, it clearly wants to build, and has a large expansion program based on two separate sales tax referenda, with lines programmed through the 2060s due to the extreme construction costs. However, the capital prioritization is just wrong, in several ways:

- The priority list puts low-usage extensions to the suburbs, like the Foothills Extension of the Gold Line and the West Santa Ana Branch, above core lines replacing high-usage buses like South Vermont and connectivity projects like linking Burbank and Pasadena directly.

- The suburban extensions often use the wrong mode or alignment – Los Angeles loves freeway medians for light rail rights-of-way, is building some lines parallel to or even in the right-of-way of commuter rail in lieu of improving Metrolink, and was starting to run into capacity problems on the shared street-running section of the Expo and Blue Lines before corona even on an otherwise low-intensity system.

- There is no transit-oriented development plan – the region is likely the NIMBY capital of the United States, and perhaps the developed world, with large swaths of valuable near-center land that’s about to get subway stations that’s still zoned single-family; in the state legislature, YIMBY bills increasing housing production typically get a large majority of the votes of politicians representing the Bay Area and a small minority of those representing the Los Angeles region.

- Much of the referendum money is not even rail expansion, but road programs, including new freeway lanes.

The upshot is that while New York builds the right projects wrong, Los Angeles builds the wrong projects, besides its issue of very high construction costs.

In reality, most places are on a spectrum, or even evolve from one to the other based on political changes. San Francisco built the almost totally useless Central Subway due to demands by people in Chinatown who don’t even ride public transportation; the line is so short and deep that even ignoring its construction costs, its trip time benefit over the buses it’s replacing is maybe 30 seconds. However, the future projects it wants to build but can’t due to high costs – the Downtown Extension tunnel taking Caltrain from its present near-center terminus to the actual city center and a second BART tube across the Bay with an extension under Geary – are exactly the right priorities, and would have long been built anywhere that could tunnel for $250 million/km and not $1 billion/km.

Boston, likewise, is building the right priorities at the level of what lines are visible on the map, but it has the second of Los Angeles’s four problems in droves. The Green Line Extension should have been commuter rail; the commuter rail electrification project should be all-catenary and not the current plan of a combination of catenary and experimental battery technology; the deelectrification of the trolleybuses was just embarrassing. But the actual alignments – the Green Line Extension, the planned Red-Blue Connector, and the Regional Rail project – are the right priorities, at least.

The wrong project, done right

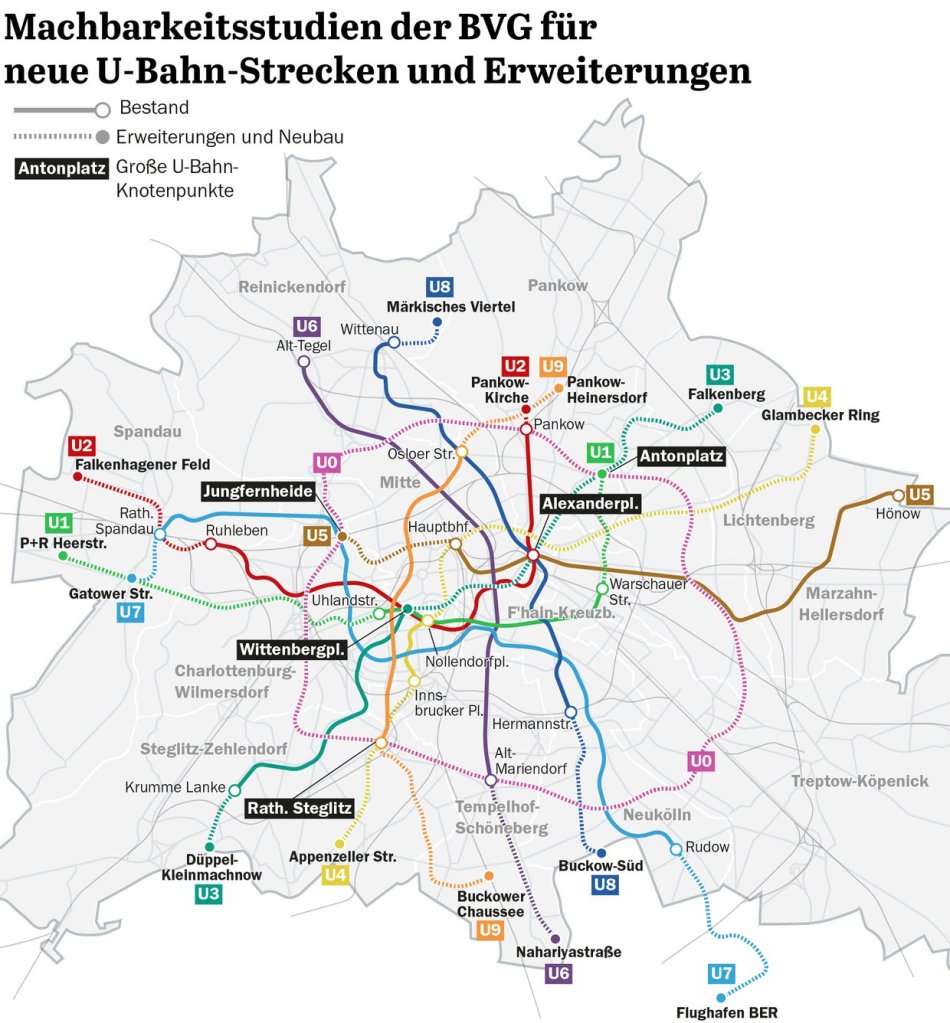

So far I’ve given American examples of poor construction practices. But there are also examples of places that build effectively but have poor prioritization. My own city, Berlin, is the best example I can think of: its construction costs are pretty average – higher than in Southern Europe, lower than anywhere that uses international English-dominant consultants – but its project prioritization is terrible.

The obviously lowest-cost-per-rider extension, that of U8 to Märkisches Viertel (see some references linked here), has been deprioritized due to bad politicking. The Green Party and the heir to the East German communist party, Die Linke, both oppose subway construction on ideological grounds and prefer trams, the Greens because they associate subway construction with making room on the surface for cars and Die Linke for a combination of being used to East German trams and general wrecker politics. In the outgoing coalition, the pro-subway Social Democrats pushed for the lines that were the most important for its own priorities and those happen to be in Spandau and at the airport rather than Märkisches Viertel; thus, the U8 extension was placed behind those.

As with the American examples in the previous two sections, here we must qualify judgment in that it’s rather common for cities to be on a spectrum. Even Berlin has better project prioritization than Los Angeles: for one, it is not as NIMBY, and the U7 airport extension does come with a transit-oriented development plan.

A more typical example is perhaps Paris. Paris’s project prioritization raises some questions, but there is no obviously low-hanging fruit like U8 that remains unbuilt due to East Germany and 1970s New Left dead-enders. The current expansion plans underrate core capacity, by which I mean separating the RER B and D tunnels, currently shared between Gare du Nord and Châtelet-Les Halles; but such a project would be disruptive if highly beneficial, and another core capacity project, namely the expansion of the RER E through the city to La Défense and western suburbs, is proceeding. The outward expansion of the Métro seems to be largely in line with what the most important priorities are; Grand Paris Express is a mix of good lines, that is Métro Lines 14, 15, and 16, and bad that is Line 17 to the airport and Line 18 linking two rich suburbs with little density in-between.

Moreover, the Paris suburbs, where practically all expansion is done, are fairly YIMBY. Francilien housing production in the late 2010s was 80,000-90,000 a year (in 2019 it was 82,000, or 6.7/1,000 people), with virtually no construction in the city proper – and moreover, the housing built in the suburbs tends to be infill replacing disused industrial land, or else it’s on top of planned Grand Paris Express or RER stations.

Why?

The poor project prioritization in the cities I’ve given the most attention to – Los Angeles but also Berlin and San Francisco and glimpses of Paris and New York – is entirely about politics. As the worst city of the bunch, Los Angeles has illuminating features that we can use to judge the others.

In Southern California, the most significant misfeature is the statewide requirement that all tax increases be approved in a referendum by a two-thirds majority. In San Francisco, the electorate is so left-wing that this hurdle is not hard to clear, and agencies can plan as always. In Los Angeles and San Diego, it is not, and to secure enough votes, agencies have to essentially bribe clientelistic actors with specific lines on a map that those actors will never use but still take credit for. This leads to all of the following misfeatures:

- Ballot propositions that include not just expansion of the rail network but also subsidies to reduced fares for people with local New Left politics who identify politically against state planning, road expansion money for local notables who don’t mind rail expansion but think it’s too political to prioritize rail over cars, and long-term maintenance for unambitious bureaucrats who love spending that isn’t expected to produce concrete results.

- An expansion program that gives each subregion its own line – in Los Angeles, this is the Orange Line BRT for the Valley, the Gold Line for San Gabriel Valley, and so on; the core is a subregion in its own right and can get a project too, like the Regional Connector subway, but it can’t be expected to get too many projects, and interregional connections are less important since the regions they serve already have their lines.

- The planning is haphazard and avoids paradigmatic changes like modernizing the commuter rail system – Los Angeles has some advocates pushing for electrification, like Paul Dyson, and long-term plans to actually do it, but those plans are far behind what Caltrain electrification in the Bay Area (a perfect example of the right project done wrong) and what technical advocates are doing in Philadelphia and Boston.