Category: High-Speed Rail

Intercity Rail Frequency and the Perils of Market Segmentation

SNCF loves market segmentation. Run by airline execs, the company loves to create different trains for different classes of people. Not only do individual trains have opaque pricing run on the basis of yield management, in which similar seats on the same train at the same time of day and day of week may have different fares, but also there are separately-branded trains for separate fare classes, the higher-fare InOui and the lower-fare OuiGo. On international trains, SNCF takes it to the limit and thus Eurostar and Thalys charge premium fares (both about twice as high as domestic TGVs per passenger-km) and don’t through-ticket with domestic TGVs. This has gotten so bad that in Belgium, some advocates have proposed a lower-priced service on the legacy Paris-Brussels line, which would have to be subsidized owing to the high cost of low-speed intercity rail service.

But why is market segmentation on rail so bad? The answer has to do with frequency and cost structures that differ from those of airlines. Both ensure that the deadweight loss from market segmentation exceed any gains that could be made from extracting consumer surplus.

The issue of frequency

A segmented market like that of domestic TGVs reduces frequency on each segment. To maintain segmentation, SNCF has to make the segments as difficult to substitute for each other as possible. OuiGo serves Marne-la-Vallée instead of Gare de Lyon and forcing passengers onto a 20-minute RER connection, or even longer if they’re arriving in Paris and the wave of 1,000 TGV riders creates long lines at the ticketing machines; on other LGVs it serves the traditional Parisian station and thus the segments are more substitutable.

The situation of Eurostar and Thalys reduces frequency as well: the high fares discourage ridership and send much of it to intercity buses or suppress travel. Fewer riders, or fewer riders per segment as in the case of domestic TGVs, lead to fewer trains. What’s the impact of this on ridership?

The literature on high-speed rail ridership elasticities has some frequency estimates. In Couto’s thesis (PDF-p. 225), it is stated that passenger rail ridership has an elasticity of 0.53 with respective to overall service provision. There are also multiple papers estimating the elasticity with respect to travel time: in Cascetta-Coppola the elasticity ranges from -1.6 to -2.2, in Börjesson it is -1.12, and in a Civity report it is stated based on other work that it is -0.8 to -2. The lowest values in Börjesson are associated with the premium-fare AVE, while the range for the original TGV, priced at the same level as the slower trains it replaced, is -1.3 to -1.6. The upshot is that halving frequency through market segmentation reduces ridership by a factor of 2^0.53 = 1.44, which is far more than the benefit yield management is claimed to have, which is a 4% increase in revenue per SNCF’s American proposals from 2009.

Why are trains different?

Planes and buses happily use yield management. High-speed trains do not, except for those run by SNCF or RENFE – and ridership in France isn’t really higher than in fixed-fare Northern Europe or East Asia while ridership in Spain is much lower. Why the difference?

The reason has to do with the ratio of waiting time to trip time. Thalys connects Paris and Brussels in 1.5 hours, every half hour at rush hour and every 2 hours midday. At rush hour, frequency is sort of noticeable; off-peak, it dominates travel time. This is nothing like planes – even short-distance trips involve hours of access, waiting, and egress time, and therefore trips are not usually spontaneous, and day trips are rare except for business travelers.

Buses, finally, are so small that a market like New York-Philadelphia supports multiple competitors each running frequently, and passenger behavior is such that different companies are substitutable, so that the effective frequency is multiple buses per hour.

Cost structure and bad incentives

It’s typical to price high-speed rail higher than legacy rail, even when otherwise there is no yield management. This is bad practice. The operating costs of high-speed rail are lower than those of slow trains. The crew is paid per hour; electricity costs are in theory higher at higher speed but in practice greenfield high-speed lines are constant 300 km/h cruises whereas legacy lines have many acceleration and deceleration cycles; high-speed trainsets cost much more than conventional ones (by a factor of about 2 in Europe) but also depreciate by the hour and not by the km and therefore are somewhat cheaper per seat-km.

This is comparable to the bad practice, common in the United States and in developing and newly-industrialized countries, of pricing urban rail higher than a bus. The metro is nicer for consumers than a bus, but it also has far lower operating costs and therefore a wise transit agency will avoid incentivizing passengers to take buses and instead use integrated fares. The same is true for slow and fast trains: the solution proposed by the Belgian advocates is to incentivize passengers to take a high-cost, low-price train over a low-cost, high-price one, and therefore is no solution at all.

Moreover, the cost structure of trains is different from that of planes. Planes don’t pay much for fixed infrastructure; in effect, every plane trip costs money, and then the challenge is to fill all the seats. High-speed railways instead pay a lot for infrastructure, while their above-the-rails costs are a few cents per passenger-km (€0.06/seat-km on the TGV, including trainset costs and a lot of labor inefficiency). Their challenge is how to fill the tracks with trains, not how to fill the trains with passengers. This is why the fixed clockface frequency common in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands is so powerful: the off-peak trains are less full, but that’s fine, as the marginal operating cost of an off-peak train is low.

Just lower the fares

Bear in mind that frequency is not exogenous – it is set based on demand. This means that anything that affects ridership has its impact magnified by the frequency-ridership spiral. An exogenous shock, such as improvement in trip time or fare reduction, is magnified through the spiral, by a factor of 1/(1-0.53) = 2.13. In other words, every elasticity estimated in isolation must be multiplied by a factor of about 2.

And once this is understood, suddenly the optima for service look very different from what Thalys has settled on. The optimum is to charge fares to pay infrastructure costs but not much more – especially if you’re SNCF and the railway workers’ union will extract all further profit through strikes, as it did 10 years ago. And this means making sure that except at very busy times, known in advance, Paris-Brussels tickets should be 30€, not 50-100€.

The Northeastern United States Wants to Set Tens of Billions on Fire Again

The prospect of federal funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill is getting every agency salivating with desires for outside money for both useful and useless priorities. Northeastern mainline rail, unfortunately, tilts heavily toward the useless, per a deep dive into documents by New York-area activists, for example here and here.

Amtrak is already hiring project management for Penn Station redevelopment. This is a project with no transportation value whatsoever: this is not the Gateway tunnels, which stand to double capacity across the Hudson, but rather a rebuild of Penn Station to add more tracks, which are not necessary. Amtrak’s current claim is that the cost just for renovating the existing station is $6.5 billion and that of adding tracks is $10.5 billion; the latter project has ballooned from seven tracks to 9-12 tracks, to be built on two levels.

This is complete overkill. New train stations in big cities are uncommon, but they do exist, and where tracks are tunneled, the standard is two platform tracks per approach tracks. This is how Berlin Hauptbahnhof’s deep section goes: the North-South Main Line is four tracks, and the station has eight, on four platforms. Stuttgart 21 is planned in the same way. In the best case, each of the approach track splits into two tracks and the two tracks serve the same platform. Penn Station has 21 tracks and, with the maximal post-Gateway scenario, six approach tracks on each side; therefore, extra tracks are not needed. What’s more, bundling 12 platform tracks into a project that adds just two approach tracks is pointless.

This is a combined $17 billion that Amtrak wants to spend with no benefit whatsoever; this budget by itself could build high-speed rail from Boston to Washington.

Or at least it could if any of the railroads on the Northeast Corridor were both interested and expert in high-speed rail construction. Connecticut is planning on $8-10 billion just to do track repairs aiming at cutting 25-30 minutes from the New York-New Haven trip times; as I wrote last year when these plans were first released, the reconstruction required to cut around 40 minutes and also upgrade the branches is similar in scope to ongoing renovations of Germany’s oldest and longest high-speed line, which cost 640M€ as a once in a generation project.

In addition to spending about an order of magnitude too much on a smaller project, Connecticut also thinks the New Haven Line needs a dedicated freight track. The extent of freight traffic on the line is unclear, since the consultant report‘s stated numbers are self-contradictory and look like a typo, but it looks like there are 11 trains on the line every day. With some constraints, this traffic fits in the evening off-peak without the need for nighttime operations. With no constraints, it fits on a single track at night, and because the corridor has four tracks, it’s possible to isolate one local track for freight while maintenance is done (with a track renewal machine, which US passenger railroads do not use) on the two tracks not adjacent to it. The cost of the extra freight track and the other order-of-magnitude-too-costly state of good repair elements, including about 100% extra for procurement extras (force account, contingency, etc.), is $300 million for 5.4 km.

I would counsel the federal government not to fund any of this. The costs are too high, the benefits are at best minimal and at worst worse than nothing, and the agencies in question have shown time and time again that they are incurious of best practices. There is no path forward with those agencies and their leadership staying in place; removal of senior management at the state DOTs, agencies, and Amtrak and their replacement with people with experience of executing successful mainline rail projects is necessary. Those people, moreover, are mid-level European and Asian engineers working as civil servants, and not consultants or political appointees. The role of the top political layer is to insulate those engineers from pressure by anti-modern interest groups such as petty local politicians and traditional railroaders who for whatever reasons could not just be removed.

If federal agencies are interested in building something useful with the tens of billions of BIL money, they should instead demand the same results seen in countries where the main language is not English, and staff up permanent civil service run by people with experience in those countries. Following best industry practices, $17 billion is enough to renovate the parts of the Northeast Corridor that require renovation and bypass those that require greenfield bypasses; even without Gateway, Amtrak can squeeze a 16-car train every 15 minutes, providing 4,400 seats into Penn Station in an hour, compared with around 1,700 today – and Gateway itself is doable for low single-digit billions given better planning and engineering.

German Rail Traffic Surges

DB announced today that it had 500,000 riders across the two days of last weekend. This is a record weekend traffic; May is so far 5% above 2019 levels, representing full recovery from corona. This is especially notable because of Germany’s upcoming 9-euro ticket: as a measure to curb high fuel price from the Russian war in Ukraine, during the months of June, July, and August, Germany is both slashing fuel taxes by 0.30€/liter and instituting a national 9€/month public transport ticket valid not just in one’s city of domicile but everywhere. In practice, rail riders respond by planning domestic rail trips for the upcoming three months; intercity trains are not covered by the 9€ monthly pass, but city transit in destination cities is, so Berliners I know are planning to travel to other parts of Germany during the window when local and regional transit is free, displacing trips that might be undertaken in May.

This is excellent news, with just one problem: Germany has not invested in its rail network enough to deal with the surge in traffic. Current traffic is already reaching projections made in the 2010s for 2030, when most of the Deutschlandtakt is supposed to go into effect, with higher speed and higher capacity than the network has today. Travel websites are already warning of capacity crunches in the upcoming three months of effectively free regional travel (chaining regional trains between cities is possible and those are covered by the 9€ monthly pass). Investment in capacity is urgent.

Sadly, such investment is still lagging. Germany’s intercity rail network rarely builds complete high-speed lines between major cities. The longest all-high-speed connection is between Cologne and Frankfurt, 180 km apart. Longer connections always have significant slow sections: Hamburg-Hanover remains slow due to local NIMBY opposition to a high-speed line, Munich’s lines to both Ingolstadt and Augsburg are slow, Berlin’s line toward Leipzig is upgraded to 200 km/h but not to full high-speed standards.

Moreover, plans to build high-speed rail in Germany remain compromised in two ways. First, they still avoid building completely high-speed lines between major cities. For example, the line from Hanover to the Rhine-Ruhr is slow, leading to plans for a high-speed line between Hanover and Bielefeld, and potentially also from Bielefeld to Hamm; but Hamm is a city of 180,000 people at the eastern margin of the Ruhr, 30 km from Dortmund and 60 from Essen. And second, the design standards are often too slow as well – Hanover-Bielefeld, a distance that the newest Velaro Novo trains could cover in about 28 minutes, is planned to be 31, compromising the half-hourly and hourly connections in the D-Takt. Both of these compromises create a network that 15 years from now is planned to have substantially lower average speeds than those achieved by France 20 years ago and by Spain 10 years ago.

But this isn’t just speed, but also capacity. An incomplete high-speed rail network overloads the remaining shared sections. A complete one removes fast trains from the legacy network except in legacy rail terminals where there are many tracks and average speeds are never high anyway; Berlin, for example, has four north-south tracks feeding Hauptbahnhof with just six trains per hour per direction. In China, very high throughput of both passenger rail (more p-km per route-km than anywhere in Europe) and freight rail (more ton-km per route-km than the United States) through the removal of intercity trains from the legacy network to the high-speed one, whose lines are called passenger-dedicated lines.

So to deal with the traffic surge, Germany needs to make sure it invests in intercity rail capacity immediately. This means all of the following items:

- Building all the currently discussed high-speed lines, like Frankfurt-Mannheim, Ulm-Augsburg (Stuttgart-Ulm is already under construction), and Hanover-Bielefeld.

- Completing the network by building high-speed lines even where average speeds today are respectable, like Berlin-Halle/Leipzig and Munich-Ingolstadt, and making sure they are built as close to city center as possible, that is to Dortmund and not just Hamm, to Frankfurt and not just Hanau, etc.

- Purchasing 300 km/h trains and not just 250 km/h ones; the trains cost more but the travel time reduction is noticeable and certain key connections work out for a higher-speed D-Takt only at 300, not 250.

- Designing high-speed lines for the exclusive use of passenger trains, rather than mixed lines with gentler freight-friendly grades and more tunnels. Germany has far more high-speed tunneling than France, not because its geography is more rugged, but because it builds mixed lines.

- Accelerating construction and reducing costs through removal of NIMBY veto points. Groups should have only two months to object, as in Spain; current practice is that groups have two months to say that they will object but do not need to say what the grounds for those objections are, and subsequently they have all the time they need to come up with excuses.

Trains are not Planes

Trains and planes are both scheduled modes of intercity travel running large vehicles. Virgin runs both kinds of services, and this leads some systems to treat trains as if they are planes. France and Spain are at the forefront of trying to imitate low-cost airlines, with separately branded trains for different classes of passengers and yield management systems for pricing; France is even sending the low-cost OuiGo brand to peripheral train stations rather than the traditional Parisian terminals. This has not worked well, and unfortunately the growing belief throughout Europe is that airline-style competition on tracks is an example of private-sector innovation to be nourished. I’d like to explain why this has failed, in the context of trains not being planes.

How do trains and planes differ?

All of the following features of trains and planes are relevant to service planning:

| Trains | Planes |

| Stations are located in city center and are extremely inconvenient to move | Airports can be located in a wider variety of areas in the metro area, never in the center |

| Timetables can be accurate to the minute | Timetables are plus or minus an hour |

| Linear infrastructure | Airport infrastructure |

| High upfront costs, low variable costs | High upfront costs but also brutal variable costs in fuel |

| Door-to-door trip times in the 1.5-5 hour range | Door-to-door trip times starting around 3 hours counting security and other queues |

| In a pinch, passengers can stand | Standing is never safe |

| Interface with thousands of local train stations | All interface with local transport is across a strict landside/airside divide |

| Travel along a line, so there’s seat turnover at intermediate stops | Point-to-point travel – multi-city hops on one plane are rare because of takeoff and landing costs |

Taken together, these features lead to differences in planning and pricing. Plane and train seats are perishable – once the vehicle leaves, an unsold seat is dead revenue and cannot be packaged for later. But trains have low enough variable costs that they do not need 100% seat occupancy to turn a profit – the increase in cost from running bigger trains is small enough that it is justified on other grounds. Conversely, trains can be precisely scheduled so as to provide timed connections, whereas planes cannot. This means the loci of innovation are different for these two technologies, and not always compatible.

What are the main innovations of LCCs?

European low-cost carriers reduce cost per seat-km to around 0.05€ (source: the Spinetta report). They do so using a variety of strategies:

- Using peripheral, low-amenity airports located farther from the city, for lower landing fees (and often local subsidies).

- Eliminating such on-board services as free meals.

- Using crew for multiple purposes, as both boarding agents and air crew.

- Flying for longer hours, including early in the morning and later at night, to increase equipment utilization, charging lower fares at undesirable times.

- Running a single class of airplane (either all 737 or all 320) to simplify maintenance.

They additionally extract revenue from passengers through hidden fees only revealed at the last moment of purchase, aggressive marketing of on-board sales for ancillary revenue, and an opaque yield management system. But these are not cost cutting, just deceptive marketing – and the yield management system is in turn a legacy carrier response to the threat of competition from LCCs, which offer simpler one-way fares.

How are LCC innovations relevant to trains?

On many of the LCC vs. legacy carrier distinctions, daytime intercity trains have always been like LCCs. Trains sell meals at on-board cafes rather than providing complimentary food and drinks; high-speed rail carriers aim at fleet uniformity as much as practical, using scale to reduce unit maintenance costs; trains have high utilization rates using their low variable operating costs.

On others, it’s not even possible to implement the LCC feature on a railroad. SNCF is trying to make peripheral stations work on some OuiGo services, sending trains from Lyon and Marseille to Marne-la-Vallée and reserving Gare de Lyon for the premium-branded InOui trains. It doesn’t work: the introduction of OuiGo led to a fall in revenue but no increase in ridership, which on the eve of corona was barely higher than on the eve of the financial crisis despite the opening of three new lines. The extra access and egress times at Marne-la-Vallée and the inconvenience imposed by the extra transfer with long lines at the ticketing machines for passengers arriving in Paris are high enough compared with the base trip time so as to frustrate ridership. This is not the same as with air travel, whose origins are often fairly diffuse because people closer to city center can more easily take trains.

What innovations does intercity rail use?

Good intercity train operating paradigms, which exist in East Asia and Northern Europe but not France or Southern Europe, are based on treating trains as trains and not as planes (East Asia treats them more like subways, Northern Europe more like regional trains). This leads to the following innovations:

- Integration of timetable and infrastructure planning, taking advantage of the fact that the infrastructure is built by the state and the operations are either by the state or by a company that is so tightly linked it might as well be the state (such as the Shinkansen operators). Northern European planning is based on repeating hourly or two-hourly clockface timetables.

- Timed connections and overtakes, taking advantage of precise timetabling.

- Very fast turnaround times, measured in minutes; Germany turns trains at terminal stations in 3-4 minutes when they go onward, such as from north of Frankfurt or Leipzig to south of them with a reversal of the train direction, and Japan turns trains at the end of the line in 12 minutes when it needs to.

- Short dwell times at intermediate stops – Shinkansen trains have 1-minute dwell times when they’re not sitting still at a local station waiting to be overtaken by an express train.

- A knot system in which trips are sped up so as to fit into neat slots with multiway timed connections at major stations – in Switzerland, trains arrive at Zurich, Basel, and Bern just before the hour every half hour and depart just after.

- Fare systems that reinforce spontaneous trips, with relatively simple fares such that passengers don’t need to plan trips weeks in advance. East Asia does no yield management whatsoever; Germany does it but only mildly.

All of these innovations require public planning and integration of timetable, equipment, and infrastructure. These are also the exact opposite of the creeping privatization of railways in Europe, born of a failed British ideological experiment and a French railway that was overtaken by airline executives bringing their own biases into the system. On a plane, my door-to-door time is so long that trips are never spontaneous, so there’s no need for a memorable takt or interchangeable itineraries; on a train, it’s the exact opposite.

EU Reaches Deal for Eastern European Infrastructure Investment

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced this morning that the EU will proceed with a coordinated investment plan for Ukraine, whose EU membership is a foregone conclusion at this point, as well as for surrounding EU member states. This will include a cohesion fund for both war reconstruction and long-term investment, which will have a component marked for Belarus’s incorporation into the Union as well subject to the replacement of its current regime with a democratic government.

To handle the infrastructure component of the plan, an EU-wide rail agency, to be branded Eurail, will take over the TEN-T plan and extend it toward Ukraine. Sources close to all four major pro-European parties in the EU Parliament confirm that the current situation calls for a European solution, focusing on international connections both internally to the established member states and externally to newer members.

The office of French President Emmanuel Macron says that just as SNCF has built modern France around the TGV, so will Eurail build modern Europe around the TEN-T network, with Paris acting as the center of a continental-scale high-speed rail network. An anonymous source close to the president spoke more candidly, saying that Brussels will soon be the political capital of an ever closer economic and now infrastructural union, but Paris will be its economic capital, just as the largest city and financial center in the United States is not Washington but New York and that of Canada is not Ottawa but Toronto.

In Eastern Europe, the plan is to construct what German planners have affectionately called the Europatakt. High-speed rail lines, running at top speeds ranging between 200 and 320 km/h, are to connect the region as far east as Donetsk and as far northeast as Tallinn, providing international as well as domestic connections. Regional trains at smaller scale will be upgraded, and under the Europatakt they will be designed to connect to one another as well as to long-distance trains at regular intervals.

For example, the main east-west corridor is to connect Berlin with Kyiv via Poznań, Łódź, Warsaw, Lublin, Lutsk, and Zhytomyr. Berlin-Warsaw trips are expected to take 2.5 hours and Warsaw-Kyiv trips 3.5 hours, arranged so that trains on the main axis will serve Warsaw in both directions on the hour every hour, timing a connection with trains from Warsaw to Kaunas, Riga, Tallinn, and Helsinki and with domestic intercity and regional trains with Poland. In Ukraine, too, a connection will be set up in Poltava, 1.5 hours east of Kyiv, every hour on the hour as in Warsaw, permitting passengers to interchange between Kyiv, Kharkiv, Dnipro, and Donetsk.

Overall, the network through Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic states, including onward connections to Berlin, Czechia, Bucharest, and Helsinki, is expected to be 6,000 km long, giving these countries comparable networks to those of France and Spain. The expected cost of the program is 150 billion euros plus another 50 billion euros for connections.

How High-Speed and Regional Rail are Intertwined

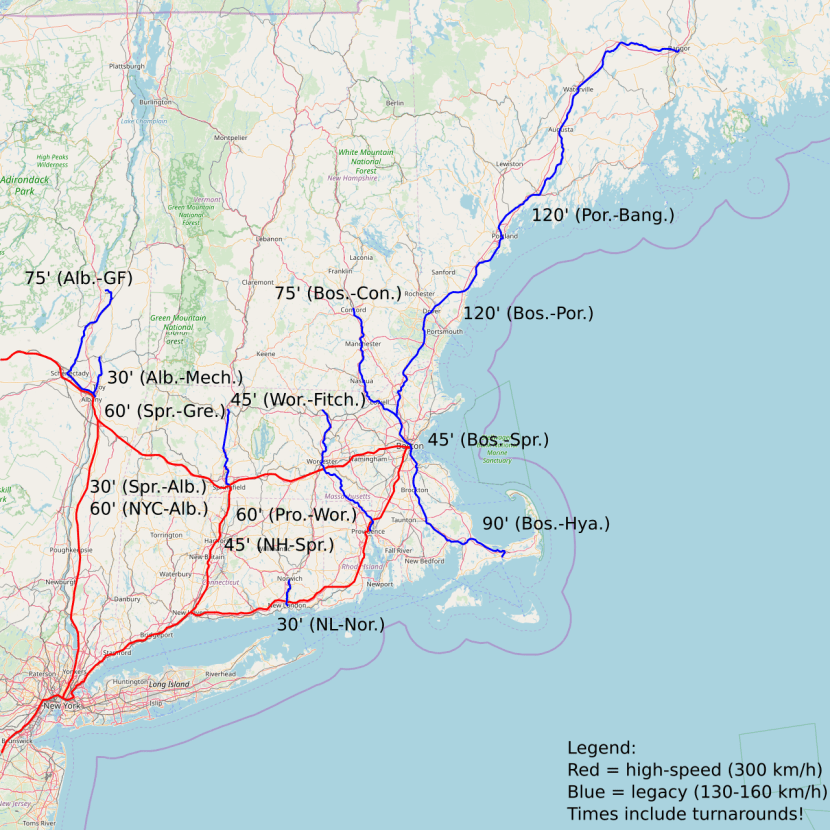

The Transit Costs Project will wrap up soon with the report on construction cost differences, and we’re already looking at a report on high-speed rail. This post should be read as some early scoping on how this can be designed for the Northeast Corridor. In particular, integration of planning with regional rail is obligatory due to the extensive track sharing at both ends of the corridor as well as in the middle. This means that the project has to include some vision of what regional rail should look like in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington. This vision is not a full crayon, but should have different options for different likely investment levels and how they fit into an intercity vision, within the existing budget, which is tens of billions thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework.

Boston

In Boston, commuter rail and intercity rail interact via the Providence Line, which is double-track. The Providence Line shares the same trunk line into Boston with the Franklin Line and the Stoughton Line, and eventually with South Coast Rail services.

The good news is that the MBTA is seriously looking at electrifying the trains to a substantial if insufficient extent. The Providence Line is already wired, except for a few siding and yard tracks, and the MBTA is currently planning to complete electrification and purchase EMUs on the main line, and possibly also on the Stoughton Line; South Coast Rail is required to be electrified when it is connected to this system anyway, for environmental reasons. If there is no further electrification, then it signals severe incompetence in Massachusetts but is still workable to a large extent.

Options for scheduling depend on how much further the state invests. The timetables I’ve written in the past (for an aggressive example, see here) assume electrification of everything that needs to be electrified but no North-South Rail Link tunnel. An NSRL timetable requires planning high-speed rail in conjunction with the entirety of the regional rail system; this is true even though intercity trains should terminate on the surface and not use the NSRL tunnel.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia is the easiest case. Trenton-Philadelphia is four-track, and has sufficiently little commuter traffic that the commuter trains can be put on the local tracks permanently. In the presence of high-speed rail, there is no need for express commuter trains – passengers can buy standing tickets on Trenton-Philadelphia, and those are not going to create a capacity crunch because train volumes need to be sized for the larger peak market into New York anyway.

On the Wilmington side, the outer end of the line is only triple-track. But it’s a short segment, largely peripheral to the network – the line is four-track from Philadelphia almost all the way to Wilmington, and beyond Wilmington ridership is very low. Moreover, Wilmington itself is so slow that it may be valuable to bypass it roughly along I-95 anyway.

The railway junctions are a more serious interface. Zoo Interlocking controls everything heading into Philadelphia from points north, and needs some facelifts (mainly, more modern turnouts) speeding up trains of all classes. Thankfully, there is no regional-intercity rail conflict here.

Washington

In some ways, the Washington-Baltimore Penn Line is a lot like the Boston-Providence line. It connects two historic city centers, but one is much larger than the other and so commuter demand is asymmetric. It has a tail behind the secondary city with very low ridership. It runs diesel under catenary, thanks to MARC’s recent choice to deelectrify service (it used to run electric locomotives).

But the Penn Line has significant sections of triple- and quad-track, courtesy of a bad investment plan that adds tracks without any schedule coordination. The quad-track segment can be used to simplify the interface; the triple-track segment, consisting of most of the line’s length, is unfortunately not useful for a symmetric timetable and requires some strategic quad-track overtakes. The Penn Line must be reelectrified, with high-performance EMUs minimizing the speed difference between regional and intercity trains. There are only five stations on the double- and triple-track narrows – BWI, Odenton, Bowie State, Seabrook, New Carrollton – and even figuring differences in average speed, this looks like a trip time difference between 160 km/h regional rail and 360 km/h HSR of about 15 minutes, which is doable with a single overtake.

New York

New York is the real pain point. Unlike in Boston and Washington, it’s difficult to isolate different parts of the commuter rail network from one another. Boston can more or less treat the Worcester, Providence+Stoughton, Fairmount, and Old Colony Lines as four different, non-interacting systems, and then slot Franklin into either Providence or Fairmount, whichever it prefers. New York can, with current and under-construction infrastructure, plausibly separate out some LIRR lines, but this is the part of the system with the least interaction with intercity rail.

Gateway could make things easier, but it would require consciously treating it as total separation between the Northeast Corridor and Morris and Essex systems, which would be a big mismatch in demand. (NEC demand is around twice M&E demand, but intercity trains would be sharing tracks with the NEC commuter trains, not the M&E ones; improving urban commuter rail service reduces this mismatch by loading the trains more within Newark but does not eliminate it.)

It’s so intertwined that the schedules have to be done de novo on both systems – intercity and regional – combined. This isn’t as in Boston and Washington, where the entire timetable can be done to fit one or two overtakes. This isn’t impossible – there are big gains to be had from train speedups all over and there. But it requires cutting-edge systems for timetabling and a lot of infrastructure investment, often in places that were left for later on official plans.

Quick Note: I Gave a Talk About High-Speed Rail Practices

My TransitCon talk should not be too surprising to people who’ve read my post about different national traditions of high-speed rail. But for completeness, here it is.

Intercity Rail Routes into Boston

People I respect are asking me about alternative routes for intercity trains into Boston. So let me explain why everything going into the city from points south should run to South Station via Providence and not via alternative inland routes such as Worcester or a new carved-up route via Woonsocket.

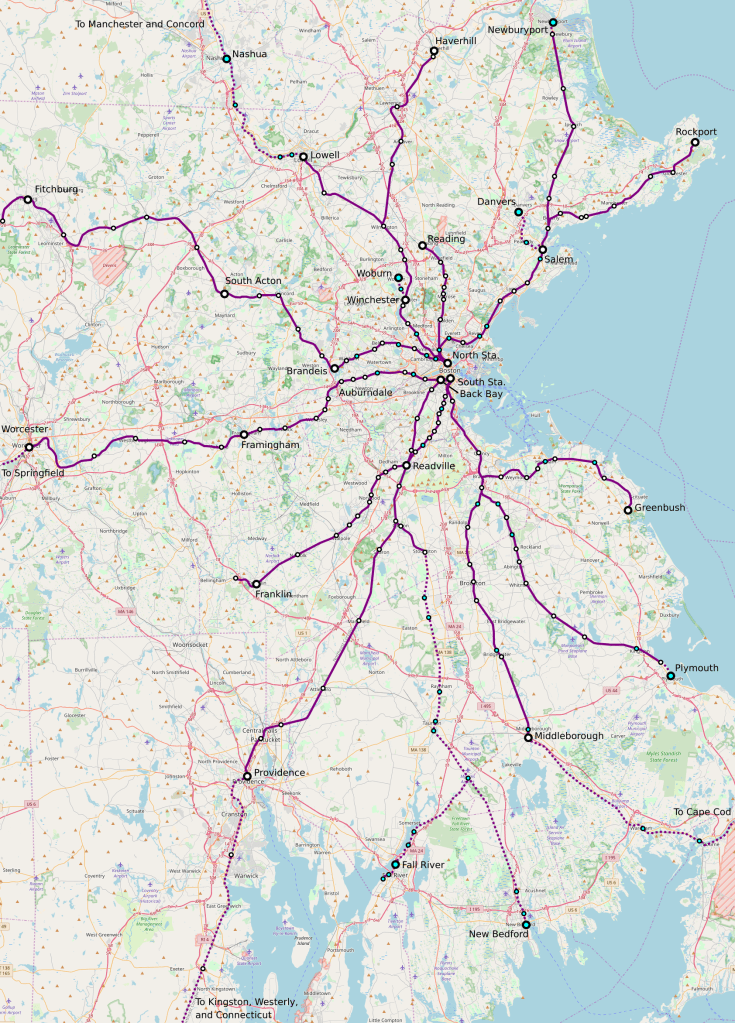

As an explanation, here is a map of the region’s commuter rail network; additional stations we’re proposing for regional rail are in turquoise, and new line segments are dashed.

Observe that the Providence Line, the route currently used by all intercity trains except the daily Lake Shore Limited, is pretty straight – most of it is good for 300+ km/h as far as track geometry goes. The Canton Viaduct near that Canton Junction station is a 1,746 meter radius curve, good for 237 km/h with active suspension or 216 km/h with the best non-tilting European practice. This straightness continues into Rhode Island, separated by a handful of curves that are to some extent fixable through Pawtucket. The fastest segment of the Acela train today is there, in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

The Worcester Line is visibly a lot curvier. Only two segments allow 160 km/h running in our regional rail schedules, around Westborough and immediately west of Grafton. This is why, ignoring intercity rail, our timetables have Boston-Providence trains taking 47 minutes where Boston-Worcester express trains take 45 minutes with 4 fewer stops or 57 minutes with 5 more, over the same route length. And the higher the necessary top speed, the larger the trip time mismatch is due to curves.

Going around the curves of the Worcester Line is possible, if high-speed rail gets a bypass next to I-90. However, this introduces three problems:

- More construction is needed, on the order of 210 km between Auburndale and New Haven compared with only 120 between Kingston and New Haven.

- Bypass tracks can’t serve the built-up area of Worcester, since I-90 passes well to its south. A peripheral station is possible but requires an extension of the commuter rail network to work well. Springfield and Hartford are both easy to serve at city center, but if only those two centers are servable, this throws away the advantage of the inland route over Providence in connecting to more medium-size intermediate cities.

- The two-track section through Newton remains the stuff of nightmares. There is no room to widen the right-of-way, and yet it is a buys section of the line, where it is barely possible to fit express regional rail alongside local trains, let alone intercity trains. Fast intercity trains would require a long tunnel, or demolition of two freeway lanes.

There’s the occasional plan to run intercity rail via the Worcester Line anyway. This is usually justified on grounds of resiliency (i.e. building too much infrastructure and running it unreliably), or price discrimination (charging less for lower-speed, higher-cost trains), or sheer crayoning (a stop in Springfield, without any integration with the rest of the system). All of these justifications are excuses; regional trains connecting Boston with Springfield and Springfield with New Haven are great, but the intercity corridor should, at all levels of investment, remain the Northeast Corridor, via Providence.

The issue is that, even without high-speed rail, the capacity and high track quality are on Providence. Then, as investment levels increase, it’s always easier to upgrade that route. The 120 km of high-speed bypass between New Haven and Kingston cost around $3-3.5 billion at latter-day European costs, save around 25 minutes relative to best practice, and open the door to more frequent regional service between New Haven and Kingston on the legacy Shore Line alongside high-speed intercity rail on the bypass. This is organizationally easy spending – not much coordination is required with other railroads, unlike the situation between New Haven and Wilmington with continuous track sharing with commuter lines.

If more capacity is required, adding strategic bypasses to the Providence Line is organizationally on the easy side for intercity-commuter rail track sharing (the Boston network is a simple diagram without too much weird branching). There’s a bypass at Attleboro today; without further bypasses, intercity trains can do Boston-Attleboro in 11 fewer minutes than regional trains if both classes run every 15 minutes, which work out to 25 minutes per our schedule and around 32 between Boston and Providence. To run intercity trains faster, in around 22 minutes, a second bypass is needed, in the Route 128-Readville area, but that is constructible at limited cost. If trains are desired more than very 15 minutes, then a) further four-tracking is feasible, and b) an intercity railroad that fills a full-length train every 15 minutes prints money and can afford to invest more.

This system of investment doesn’t work via the inland route. It’s too curvy, and the bypasses required to make it work are longer and more complex to build due to the hilly terrain. Then there’s the world-of-pain segment through Newton; in contrast, the New Haven-Kingston bypass can be built zero-tunnel. But that’s fine! The Northeast Corridor’s plenty upgradable, the inland route is bad for long-distance traffic (again, regional traffic is fine) but thankfully unnecessary.

Mixing High- and Low-Speed Trains

I stream on Twitch (almost) every week on Saturdays – the topic starting now is fare systems. Two weeks ago, I streamed about the topic of how to mix high-speed rail and regional rail together, and unfortunately there were technical problems that wrecked the recording and therefore I did not upload the video to YouTube as I usually do. Instead, I’d like to write down how to do this. The most obvious use case for such a blending is the Northeast Corridor, but there are others.

The good news is that good high-speed rail and good legacy rail are complements, rather than competing priorities. They look like competing priorities because, as a matter of national tradition of intercity rail, Japan and France are bad at low-speed rail outside the largest cities (and China is bad even in the largest cities) and Germany is bad at high-speed rail, so it looks like one or the other. But in reality, a strong high-speed rail network means that distinguished nodes with high-speed rail stations become natural points of convergence of the rail network, and those can then be set up as low-speed rail connection nodes.

Where there is more conflict is on two-track lines with demand for both regional and intercity rail. Scheduling trains of different speeds on the same pair of tracks is dicey, but still possible given commitment to integration of schedule, rolling stock, and timetable. The compromises required are smaller than the cost of fully four-tracking a line that does not need so much capacity.

Complementarity

Whenever a high-speed line runs separately from a legacy line, they are complements. This occurs on four-track lines, on lines with separate high-speed tracks running parallel to the legacy route, and at junctions where the legacy lines serve different directions or destinations. In all cases, network effects provide complementarity.

As a toy model, let’s look at Providence Station – but not at the issue of shared track on the Northeast Corridor. Providence has a rail link not just along the Northeast Corridor but also to the northwest, to Woonsocket, with light track sharing with the mainline. Providence-Woonsocket is 25 km, which is well within S-Bahn range in a larger city, but Providence is small enough that this needs to be thought of as scheduled regional rail. A Providence-Woonsocket regional link is stronger in the presence of high-speed rail, because then Woonsocket residents can commute to Boston with a change in Providence, and travel to New York in around 2 hours also with a change in Providence.

More New England examples can be found with Northeast Corridor tie-ins – see this post, with map reproduced below:

The map hides the most important complement: New Haven-Hartford-Springfield is a low-speed intercity line, and the initial implementation of high-speed rail on the Northeast Corridor should leave it as such, with high-speed upgrades later. This is likely also the case for Boston-Springfield – the only reason it might be worthwhile going straight from nothing to high-speed rail is if negotiations with freight track owner CSX get too difficult or if for another reason Massachusetts can’t electrify the tracks at reasonable cost and run fast regional trains.

There’s also complementarity with lines that are parallel to the Northeast Corridor, like the current route east of New Haven, which the route depicted in the map bypasses. This route serves Southeast Connecticut communities like Old Saybrook and can efficiently ferry passengers to New Haven for onward connections.

In all of these cases, there is something special: Woonsocket-Boston is a semireasonable commute, New London connects to the Mohegan Sun casino complex, New Haven-Hartford and Boston-Springfield are strong intercity corridors by themselves, Cape Cod is a weekend getaway destination. That’s fine. Passenger rail is not a commodity – something special almost always comes up.

But in all cases, network effects mean that the intercity line makes the regional lines stronger and vice versa. The relative strength of these two effects varies; in the Northeast, the intercity line is dominant because New York is big and off-mainline destinations like Woonsocket and Mohegan are not. But the complementarity is always there. The upshot is that in an environment with a strong regional low-speed network and not much high-speed rail, like Germany, introducing high-speed rail makes the legacy network stronger; in one that is the opposite, like France, introducing a regional takt converging on a city center TGV station would likewise strengthen the network.

Competition for track space

Blending high- and low-speed rail gets more complicated if they need to use the same tracks. Sometimes, only two tracks are available for trains of mixed speeds.

In that case, there are three ways to reduce conflict:

- Shorten the mixed segment

- Speed up the slow trains

- Slow down the fast trains

Shortening the mixed segment means choosing a route that reduces conflict. Sometimes, the conflict comes pre-shortened: if many lines converge on the same city center approach, then there is a short shared segment, which introduces route planning headaches but not big ones. In other cases, there may be a choice:

- In Boston, the Franklin Line can enter city center via the Northeast Corridor (locally called Southwest Corridor) or via the Fairmount Line; the choice between the two routes is close based on purely regional considerations, but the presence of high-speed rail tilts it toward Fairmount, to clear space for intercity trains.

- In New York, there are two routes from New Rochelle to Manhattan. Most commuter trains should use the route intercity trains don’t, which is the Grand Central route; the only commuter trains running on Penn Station Access should be local ones providing service in the Bronx.

- In the Bay Area, high-speed rail can center from the south via Pacheco Pass or from the east via Altamont Pass. The point made by Clem Tillier and Richard Mlynarik is that Pacheco Pass involves 80 km of track sharing compared with only 42 km for Altamont and therefore it requires more four-tracking at higher cost.

Speeding up the slow trains means investing in speed upgrades for them. This includes electrification where it’s absent: Boston-Providence currently takes 1:10 and could take 0:47 with electrification, high platforms, and 21st-century equipment, which compares with a present-day Amtrak schedule of 0:35 without padding and 0:45 with. Today, mixing 1:10 and 0:35 requires holding trains for an overtake at Attleboro, where four tracks are already present, even though the frequency is worse than hourly. In a high-speed rail future, 0:47 and 0:22 can mix with two overtakes every 15 minutes, since the speed difference is reduced even with the increase in intercity rail speed – and I will defend the 10-year-old timetable in the link.

If overtakes are present, then it’s desirable to decrease the speed difference on shared segments but then increase it during the overtake: ideally the speed difference on an overtake is such that the fast train goes from being just behind the slow train to just ahead of it. If the overtake is a single station, this means holding the slow train. But if the overtake is a short bypass of a slow segment, this means adding stops to the slow train to slow it down even further, to facilitate the overtake.

A good example of this principle is at the New York/Connecticut border, one of the slowest segments of the Northeast Corridor today. A bypass along I-95 is desirable, even at a speed of 200-230 km/h, because the legacy line is too curvy there. This bypass should also function as an overtake between intercity trains and express commuter trains, on a line that today has four tracks and three speed classes (those two and local commuter trains). To facilitate the overtake, the slow trains (that is, the express commuter trains – the locals run on separate track throughout) should be slowed further by being made to make more stops, and thus all Metro-North trains, even the express trains, should stop at Greenwich and perhaps also Port Chester. The choice of these stops is deliberate: Greenwich is one of the busiest stops on the line, especially for reverse-commuters; Port Chester does not have as many jobs nearby but has a historic town center that could see more traffic.

Slowing down the intercity trains is also a possibility. But it should not be seen as the default, only as one of three options. Speed deterioration coming from such blending in a serious problem, and is one reason why the compromises made for California High-Speed Rail are slowing down the trip time from the originally promised 2:40 for Los Angeles-San Francisco to 3:15 according to one of the planners working on the project who spoke to me about it privately.

We Ran a Conference About Rail Modernization (Again)

Modernizing Rail 2021 just happened. Here’s a recording of the Q&A portion (i.e. most) of the keynote, uploaded to YouTube.

As more people send in materials, I’ll upload more. For now, here are the slides I’ve gotten:

- Grecia White’s master’s thesis on gendered perceptions of safety at bus stops.

- Robert Hale’s presentation on New York-New Haven trains, speed, and track maintenance productivity.

- Michael Cornfield’s intro to integrated service planning as done in Central Europe, pitched to Southern California.

- RailPAC’s Paul Dyson’s presentation on Southern California (unfortunately running against Michael Cornfield’s despite the synergy), with supplementary materials by RailPAC’s Brian Yanity including a long article on the subject and two short letters.

- Elif Ensari’s presentation of the Istanbul case for the Transit Costs Project, with full report to be released soon.

A bunch of us tweeted the talks using the hashtag #ModernRail2021, including some that were not recorded.